Abstract

Tobacco smoking is the leading preventable cause of mortality and morbidity. Although behavioral counseling combined with pharmacotherapy is the most effective approach to aiding smoking cessation, intensive treatments are rarely chosen by smokers, citing inconvenience. In contrast, minimal self-help interventions have the potential for greater reach, with demonstrated efficacy for relapse prevention, but not for smoking cessation. This paper summarizes the design and methods used for a randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of a minimal self-help smoking cessation intervention that consists of a set of booklets delivered across time. Baseline participant recruitment data are also presented. Daily smokers were recruited nationally via multimedia advertisements and randomized to one of three conditions. The Usual Care (UC) group received a standard smoking-cessation booklet. The Standard Repeated Mailings (SRM) group received 8 booklets mailed over a 12-month period. The Intensive Repeated Mailings (IRM) group received 10 booklets and additional supplemental materials mailed monthly over 18 months. A total of 2641 smokers were screened, 2349 were randomized, and 1874 provided data for analyses. Primary outcomes will be self-reported abstinence at 6-month intervals up to 30 months. If the self-help booklets are efficacious, this minimal, low cost intervention can be widely disseminated and, hence, has the potential for significant public health impact with respect to reduction in smoking-related illness and mortality.

Keywords: smoking cessation intervention, randomized controlled trial, self-help intervention

1. Introduction

Tobacco smoking is the leading preventable cause of mortality, resulting in over 440,000 deaths annually in the U.S. [1] and over 5 million deaths annually worldwide [2]. Smoking cessation is associated with decreased mortality and morbidity from cancer and other diseases [3, 4, 5]. Thus, great potential for disease prevention lies with efforts toward long-term cessation of smoking. To date, the most effective evidence-based approach to smoking cessation is cognitive behavioral counseling combined with pharmacotherapy [6, 7]. However, the public health impact of this approach, and counseling in particular, has been limited by poor population reach because very few smokers use evidence-based treatments, often citing the inconvenience of the counseling [8, 9].

On the other hand, minimal, self-help interventions, such as print or electronic media, have the potential for very wide reach, but their public health impact has been limited by their low efficacy for smoking cessation [6, 9]. In contrast to self-help for smoking cessation per se, psycho-educational self-help interventions have been found to be effective for reducing smoking relapse in motivated quitters [10, 11]. One such intervention, using a set of specially developed relapse-prevention booklets, has been found to be efficacious and cost-effective among recently quit smokers [12, 13, 14]. This series of booklets, called Forever Free®, includes content that draws on empirical and theoretical research in relapse prevention [15, 16]. A modified version of the booklets was also found to reduce postpartum smoking relapse among low-income women [17]. These self-help interventions are being disseminated by the National Cancer Institute (NCI; on www.smokefree.gov) and have been adopted by medical and public health institutions throughout the country. The encouraging results on preventing smoking relapse led to the initiation of the current clinical trial to test whether this self-help treatment modality may be an efficacious, cost-effective, and easily disseminable intervention for smoking cessation per se. Given the low utilization of evidence-based interventions by smokers [18], there is a need for the development of effective low-intensity, low-cost, and easily disseminable cessation interventions. Unlike previous self-help interventions, the current treatment holds promise in that it provides cessation assistance over a relatively long time-frame and capitalizes on the benefit of social support [19] throughout the various stages of the cessation process (i.e., initial cessation, lapse, maintenance).

This paper describes the design, methods, and analysis plan of an ongoing randomized controlled trial (RCT). The primary aims of the RCT are to (1) test the efficacy of standard repeated mailings of Forever Free booklets in producing smoking cessation, (2) test the incremental efficacy of extending and increasing the frequency of contact, and (3) calculate and compare cost-effectiveness of the interventions. Baseline characteristics of the enrolled participants across treatment arms are also presented.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The initial phase of the study focused on revising the original Forever Free booklets to retarget them from relapse-prevention for ex-smokers into smoking cessation for current smokers, as well as the development of additional materials for the extended treatment arm of the study. This was followed by a three-arm randomized trial. The Usual Care (UC) group received a standard smoking- cessation booklet. The Standard Repeated Mailings (SRM) group received 8 booklets mailed over a 12-month period, the same distribution schedule as the original Forever Free® booklets. The Intensive Repeated Mailings (IRM) group received 10 booklets and additional supplemental materials, mailed monthly over 18 months, to increase the frequency and duration of the intervention. The primary outcome is self-reported point prevalence abstinence at 6-month intervals up to 30 months. We hypothesized that the SRM intervention will produce superior outcomes compared with the UC intervention. Further, we hypothesized that extending and enhancing the intervention in the IRM group will result in greater long-term abstinence than in the SRM intervention. Table 1 summarizes the intervention and assessment points, as described below.

Table 1.

Overview of Study Design: Interventions and Assessments

| UC | N | ||||||||||||||||||||

| SRM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| IRM | X | X | X | X | O | X | O | X | O | X | O | O | X | O | O | X | O | O | X | ||

| Month | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 24 | 30 |

| Assess | A | A | A | A | A | A |

Legend

UC = Usual Care; SRM = Standard Repeated Mailings; IRM = Intensive Repeated Mailings. Assess = Assessment Points; N = NCI Clearing the Air booklet; X = Forever Free booklet; O = Supportive letter and tri-fold pamphlet. A = Assessments. Shaded areas indicate the duration of the intervention.

2.2. Intervention Conditions

2.2.1. Intervention Development

The two interventions being tested in this study were based on the original Forever Free® relapse prevention booklets [12]. Although the goal of the original booklets was relapse-prevention, and their content was directed toward individuals who had achieved at least initial abstinence, much of the content was also appropriate for an individual attempting to achieve initial cessation. This was particularly true of the first booklet, which provided an overview of the quitting process. Nevertheless, the booklets were revised to alter any language that explicitly assumed that the reader had already achieved abstinence. In addition, information about preparing to quit and an increased emphasis on pharmacotherapy were added. The revised eight booklets comprised the SRM treatment. The IRM treatment consisted of the eight revised booklets, two additional newly developed booklets, and nine newly developed pamphlets. The two extra booklets reinforce key points that are conveyed in the earlier booklets. The look and feel of these booklets is identical to the first eight booklets, so they blend seamlessly into the set. The booklets and pamphlets are written at the 5-6th grade reading level so as to maximize their accessibility to individuals with a wide range of literacy levels [20, 21].

2.2.2. Usual Care (UC)

This condition comprises a single booklet that is currently in dissemination: NCI’s Clearing the Air: Quit Smoking Today [22]. It is a comprehensive 37-page booklet with high quality content and visual presentation. It was selected as a credible UC comparison condition, that is, as an active control. Thus, we wished to compare our novel, comprehensive, self-help interventions against an existing, less intensive self-help intervention. The cost of these booklets from NCI is $0.15 each.

2.2.3. Standard Repeated Mailings (SRM)

This condition comprises eight smoking cessation booklets, as described in the Intervention Development section. The first is mailed to participants immediately after receipt of their baseline assessment, and the rest are mailed at the following time points: 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 12 months. The first booklet provides a general overview about quitting smoking, and each of the remaining seven booklets include more extensive information on a topic related to maintaining abstinence: Smoking Urges; Smoking and Weight; What if You Have a Cigarette?; Your Health; Smoking, Stress, and Mood; Lifestyle Balance; and Life without Cigarettes. The content of the booklets is based on cognitive-behavioral theory [e.g., 15, 23] and empirical evidence regarding the nature of tobacco dependence, cessation, and relapse. The booklets further draw upon principles that typically represent the key relapse-prevention counseling interactions that occur in the clinic. Thus, a written, self-help format of the intervention that can be widely disseminated can potentially improve access to more smokers. The printing cost of the SRM intervention (i.e., 8 booklets) per person was $5.08.

2.2.4. Intensive Repeated Mailings (IRM)

This condition was designed to maximize both the frequency and duration of contact, with the goals of (1) extending treatment an additional 6 months, (2) maintaining monthly contact throughout the intervention period, and (3) adding an element of perceived social support. Thus, this condition comprises the same eight smoking cessation booklets as in SRM, plus two additional booklets and nine pamphlets that are sent during the months that a booklet is not sent. The content of the two additional booklets offers the opportunity to reinforce key points conveyed in the earlier booklets, as well as extend contact with participants. These booklets, entitled The Benefits of Quitting Smoking and The Road Ahead, reemphasize the health and other benefits of long-term tobacco abstinence, management of stress, anticipation of potential high-risk situations, and the use of cognitive and behavioral coping responses.

In addition to the two new booklets, contact is also made during each month that a booklet is not sent. This contact is designed to enhance the perception of social support—a benefit of face-to- face counseling [19, 24] that is often lost in self-help approaches. Each contact consists of a brief, personalized and supportive cover letter plus a tri-fold color pamphlet that reinforces key messages about quitting smoking (e.g., dealing with stress, keeping weight gain in perspective, finding other forms of positive reinforcement). To further induce a sense of social support, the messages are communicated via a first-person narrative from a former smoker (e.g., Bryan’s story). A wide diversity of individuals and stories are represented in the pamphlets. A different letter and a pamphlet are sent at each contact point. The printing cost of the IRM intervention (i.e., 10 booklets and 9 pamphlets) per person was $9.33.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Baseline Assessment

We assessed demographic characteristics, as well as smoking history, including the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) [25], a standard, validated, measure of nicotine dependence. Motivation to stop smoking was assessed with a continuous measure of readiness to quit, the Contemplation Ladder [26], as well as the Stages of Change Algorithm (SOC) [27]. In addition, we administered three other theoretically-based measures related to cessation motivation. They included a 20-item situation-specific abstinence self-efficacy scale [28], which consists of three situational factors: positive/social, negative/affective, and habit/addictive. Four subscales of a validated measure of smoking expectancies, the Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult (SCQ-A) [29] were administered: negative affect reduction, craving/addiction, health risks, and negative physical feelings. Finally, a 16-item Abstinence-Related Motivational Engagement scale [30] was administered to measure the ongoing engagement in the cessation and maintenance process following initial smoking cessation. These motivation-related variables will be tested as potential moderators of cessation outcomes.

2.3.2 Follow-Up Assessments

Participants were sent follow-up assessment packets at 6-month intervals through 30 months, as indicated in Table 1. The 30 months of follow-up were selected primarily because the distribution of the booklets continued for up to 18 months. Thus, the follow-up is in fact only 12 months beyond the end of the longest intervention (IRM). We deliberately keep the length of these assessments brief to minimize participant burden and consequent attrition. At all of the follow-up time-points, we assess tobacco use as well as any use of pharmacotherapy or other smoking cessation assistance since the previous contact. We also assess participants’ use and evaluation of the self-help materials, using the eight-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire [31] plus additional items to distinguish the benefits of the content and the repeated contact. Finally, we assess coping self-efficacy [28] as a proxy for coping skills usage. Seven-day point-prevalence abstinence rates will serve as the primary outcome variable. Point-prevalence outcome was selected primarily because it is best for capturing the dynamic nature of cessation, maintenance, and relapse (e.g., delayed intervention effects, cessation recycling), which typically occur in cessation-induction trials [32]. In addition to the primary outcome, we will calculate 30-day and 90-day point prevalence criteria to reflect prolonged abstinence.

2.4. Participants

Participants include 1874 daily smokers who returned the baseline assessment. To maximize generalizability, there were few eligibility criteria: (1) smoking at least five cigarettes per day over the past year, (2) age 18 or older, (3) not currently enrolled in a face-to-face smoking cessation program, (4) able to speak and read English, and (5) desire to quit smoking, as indicated by a score of at least 5 (“Think I should quit, but not quite ready”) on the Contemplation Ladder [26]. In addition, to reduce leakage of information about the treatment conditions among participants, we excluded multiple participants from the same street address.

2.5. Procedures

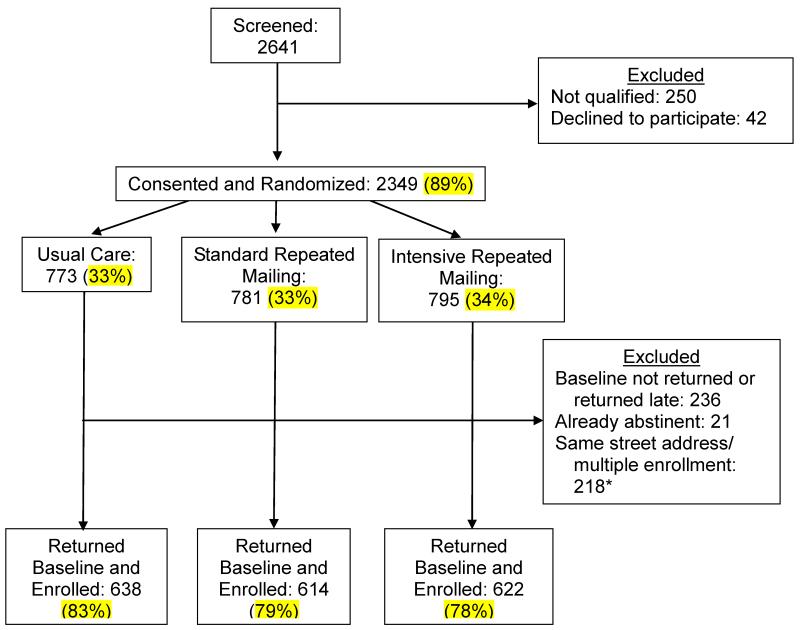

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida. Participants were recruited nationally between April, 2010 - August 2011 via multimedia advertisements, including newspapers, radio, cable TV, public transit signage, public service announcements, and direct community engagement. In response to the recruitment efforts, smokers called a toll-free telephone number and were screened for eligibility criteria by research staff. Eligible participants who provided verbal consent were randomized, using simple randomization without stratification or blocking, to one of three treatment interventions, and sent a baseline assessment questionnaire. Participants who returned a completed baseline assessment within 6 weeks and were not abstinent at that time were formally enrolled into the RCT and sent the appropriate intervention materials. Follow-up assessment questionnaires were scheduled to be sent via mail every 6 months after the date of enrollment. For convenience, all participants were offered the option to complete follow-up assessments online. A total of 2641 smokers were screened, 2349 were randomized, and 1874 provided data for analyses. Figure 1 displays the study recruitment flowchart. Participants received $20 for completing the baseline assessment, $20 for each completed follow-up assessment, and a state lottery ticket if they returned the forms within 1 week of receipt.

Figure 1.

Study Recruitment and Accrual

* Note: The exclusion criterion of multiple participants from same street address was established mid- accrual upon examination of recruitment patterns, and it was applied retroactively to participants recruited prior to that point.

2.6. Data Analyses Plan for RCT Outcomes

Baseline demographic and smoking characteristics were compared across treatment conditions using one-way analyses of variance and chi-square tests, depending on the characteristics of the variable being tested.

The first aim is to test the efficacy of SRM in producing smoking cessation compared to the UC condition. The primary statistical analyses of 7-day point prevalence will be performed using the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) approach with condition, time (follow-up time-point), and their interaction as the covariates. Potential confounding variables (e.g., group differences in demographic, smoking history, or pharmacotherapy use) will be adjusted for in the model. The primary advantages of this approach over time-specific analyses of group differences is the ability to assess change in abstinence rates over time (especially given the extended nature of the intervention) and the ability to assess condition effects averaged across multiple time points. This approach also permits assessment of differences in change in abstinence rates by condition. Furthermore, this approach offers pair-wise condition and time interval comparisons using the generalized score statistics from the GEE models via contrast statements.

The second aim tests the incremental efficacy of extending and increasing the frequency of contact in the IRM condition versus SRM, both during the extension period and beyond. Similar to the first aim, the GEE approach will be used to test the difference in the outcomes between the two interventions. Secondary analyses will test theoretically-identified mediators and moderators of treatment outcomes.

The third aim is to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis. The incremental effectiveness and costs of the intervention compared to usual care will be measured based on the health care system perspective. Using the trial endpoint results, effectiveness will be predicted in terms of smoking cessation and translated into life years and quality-adjusted life years based on published associations between smoking cessation and long-term health outcomes [33]. Costs include the intervention costs and the lifetime savings from reduced medical expenditures directly attributable to smoking cessation, which will be modeled using published estimates [34,35,36]. No out-of-pocket costs, costs associated only with the research activities (e.g., mailing of assessments), or transfer payments (i.e., increased social security due to longevity) will be incorporated into the analysis, because they do not fall within the health care system perspective Specifically, this analysis was designed to inform the decision making of a health plan administrator who is deliberating over the adoption of this health intervention for its enrollees. To further aid in the interpretation, monetary values will be inflation adjusted to 2014 dollars, and all outcomes will be presented in discounted and undiscounted values.

2.7. Sample Size Calculation

Sample size calculation was based on the Rochon method [37] for a GEE analysis of repeated binary data. The 3 conditions were predicted to have population abstinence rates of 15%, 20%, and 25% over the final 3 assessment periods. The AR (1) working correlation structure with a 0.5 correlation coefficient was assumed. It was estimated that 527 participants per condition would detect a difference between 20% and 25% abstinent with alpha = 0.05 and power > .80. The final target sample size was increased to 660 per condition to account for an estimated attrition rate of 20%.

3. Baseline Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for demographic and smoking variables for the 1874 participants contributing data for the analysis in the RCT. The total sample is 66% female, 65% Caucasian, 30% African-American, and with 5.6% identifying as Hispanic. The average age is 47.5 (SD=12.0), and 70% reported annual household income below $30,000. Participants were predominantly from the south/southeastern region of the U.S. With regard to smoking characteristics, participants smoked an average of 20.5 (SD=11.8) cigarettes per day and were moderately dependent on nicotine at the time of enrollment into the trial. Comparisons between the three conditions at baseline indicated that the UC group is slightly older (M=48.4, SD=12.0) than both the SRM group (M=46.5, SD=12.5) and the IRM group (M=47.5, SD=11.5), p < .05. There are no other baseline differences between the three treatment conditions.

Table 2.

Baseline Sample Characteristics by Treatment Condition

|

UC N = 638 |

SRM N = 614 |

IRM N = 622 |

Total N = 1874 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age *, years: M(SD) | 48.4 (12.0) | 46.5 (12.5) | 47.5 (11.5) | 47.5 (12.0) |

| Sex, N(%) | ||||

| Men | 208 (33%) | 219 (36%) | 214 (34%) | 641 (34%) |

| Women | 430 (67%) | 395 (64%) | 408 (66%) | 1233 (66%) |

| Race, N(%) | ||||

| White | 409 (65%) | 410 (67%) | 393 (64%) | 1212 (65%) |

| Black/African-American | 193 (31%) | 175 (29%) | 189 (31%) | 557 (30%) |

| Other | 30 (4%) | 28 (4%) | 36 (5%) | 94 (5%) |

| Ethnicity, N(%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 32 (5%) | 35 (6%) | 36 (6%) | 103 (6%) |

| Income, N(%) | ||||

| Under $10,000 | 209 (34%) | 205 (34%) | 198 (32%) | 612 (33%) |

| $10,000-$19,000 | 141 (23%) | 145 (24%) | 151 (25%) | 437 (24%) |

| $20,000-$29,000 | 80 (13%) | 75 (13%) | 75 (12%) | 230 (13%) |

| $30,000+ | 192 (30%) | 171 (29%) | 191 (31%) | 554 (30%) |

| Cigarettes per day, M(SD) | 20.4 (11.2) | 20.9 (13.0) | 20.3 (11.2) | 20.5 (11.8%) |

| FTND1, M(SD) | 5.7 (2.3) | 5.6 (2.3) | 5.7 (2.2) | 5.7 (2.3) |

| Stage of Change, N(%) | ||||

| Precontemplation | 24 (4%) | 15 (3%) | 21 (4%) | 60 (4%) |

| Contemplation | 316 (53%) | 308 (54%) | 299 (51%) | 923 (53%) |

| Preparation | 257 (43%) | 249 (44%) | 261 (45%) | 767 (44%) |

| Contemplation ladder, (SD) | 8.0 (2.1) | 7.9 (2.2) | 8.0 (2.1) | 8.0 (2.1) |

Notes:

p < .05

Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence

UC = Usual Care; SRM = Standard Repeated Mailings; IRM = Intensive Repeated Mailings

4. Discussion

This study is the first large-scale RCT to evaluate the efficacy of a self-help cessation intervention of up to 18 months in duration, delivered via mail. The intervention is based on the successful Forever Free® series for former smokers [12, 13], and draws on empirical and theoretical research in relapse prevention. Although self-help interventions have previously demonstrated low efficacy for smoking cessation [6, 9], the current study’s intervention was based upon promising preliminary findings from Brandon et al. [12, 13] with increased duration and intensity of the IRM condition. In addition, the 30-month follow-up period of the current study allows for long-term efficacy evaluation of over 2 years post treatment initiation.

This study has several strengths. We were able to recruit a large, diverse participant sample, which should provide statistical power to test both mediating and moderating variables, including demographic and smoking characteristics, as well as motivation-related measures. The study sample is overrepresented by females, which is consistent with previous relapse prevention clinical trials [12, 13, 38]. The sample is representative of the current adult smoking population with regard to age and socioeconomic level [39], with a large proportion reporting low income. The smoking rate in the current sample was consistent with more recent cessation trials (e.g., 38, 40) and lower than that of smokers in the earlier studies using self-help relapse prevention materials [12, 13].

It uses RCT methodology to test three self-help interventions of varying strengths, providing the ability to conduct cost-effectiveness analyses and calculate dose-response effects. It expands upon a successful intervention for relapse prevention by including facilitation of initial tobacco cessation. The interventions are low-cost, with printing costs to the study under $10 per person. These costs would decline dramatically for large-scale dissemination, due to economies of scale. This study represents a compelling next step in a line of research that has potential for significant public health impact with respect to reduction in smoking-related illness and mortality.

There are several limitations and design considerations that should be noted. One limitation is that biochemical verification of smoking cessation status is not included due to logistical barriers, as participants were recruited from throughout the United States. However, this decision is in line with research showing that there is little benefit derived from inclusion of biochemical verification measures in low-intensity interventions without strong incentives to report false abstinence [41, 42].

Another limitation is that the current study does not include a true no-treatment control condition. Instead, the comparison UC group received a high-quality, credible intervention in the form of an NCI booklet. However, the goal of the study was to demonstrate increased efficacy of the new intervention over an existing, less intensive one, thereby contributing to the public health significance of the intervention.

An important design consideration is the potential variability between participants, particularly with regard to use of pharmacotherapy. Excluding smokers who report using any pharmacotherapy would have reduced variability; however, it would also have reduced the ecological validity of the study, because pharmacotherapy is readily available to smokers and is likely to be used by many smokers in the population to which we wish to generalize. In fact, the intervention encourages the use of pharmacotherapy. Instead, pharmacotherapy use is assessed at each follow-up time-point and will be examined statistically. The self-selection of participants into the study and through completion of follow-ups may have resulted in a sample that may not generalize to the general population of smokers. In particular, the current sample is overrepresented by females and low-income individuals. Individuals from lower income groups may be more motivated by the monetary compensation provided by research studies. However, this limitation is mitigated by the fact that smoking prevalence is highest among adults from low socioeconomic groups [39], Another design consideration is the distribution of materials by mail rather than other modalities, such as via the internet. Distribution via the internet would have some advantages, such as increasing the reach of the intervention and reducing costs [43]. It would also allow for tailoring of the intervention [44]. However, the goal of this study was to test an intervention that has previously showed promise of efficacy before changing the delivery modality. If efficacy is established, future research could test the impact of alternate modalities and formats (including mobile).

In summary, the ongoing study represents a large-scale test of the efficacy of a low-cost, easy to disseminate, self-help smoking cessation intervention. To date, we have recruited a large and diverse sample. This study has the potential to address smoking cessation using a cost-effective intervention with wide reach, thus producing significant impact on public health at a population level.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01 CA134347 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5. References Cited

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Years of Potential Life Lost, and Productivity Losses—United States, 2000-2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(45):1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].World Health Organization (WHO) Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/ Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. 2011 http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/

- [3].Gerber Y, Myers V, Goldbourt U. Smoking reduction at midlife and lifetime mortality risk in men: a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;175:1006–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr466. Doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Papathanasiou A, Milionis H, Toumpoulis I, Kalantzi K, Katsouras C, Pappas K, Michalis L, Goudevenos J. Smoking cessation is associated with reduced long-term mortality and the need for repeat interventions after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;13(3):448–50. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280403c68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case- control studies. BMJ. 2000;321:323–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, Curry SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hughes JR. Combining behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation: An update. In: Onken LS, Blaine JD, Boren JJ, editors. Integrating behavior therapies with medication in the treatment of drug dependence: NIDA Research Monograph. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1995. pp. 92–109. Monograph no. 150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, Giovino GA, Hatziandreu EJ, Newcomb PA, et al. Methods used to quit smoking in the United States: Do cessation programs help? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;263:2760–2765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lancaster T, Stead LF. Self-help interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(issue 3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001118.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Agboola S, Mcneill A, Coleman T, Bee JL. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smoking relapse prevention interventions for abstinent smokers. Addiction. 2010;105:1362–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Song F, Huttunen-Lenz M, Holland R. Effectiveness of complex psycho-educational interventions for smoking relapse prevention: an exploratory meta-analysis. Journal of Public Health. 2010;32:350–359. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Brandon TH, Collins BN, Juliano LM, Lazev AB. Preventing relapse among former smokers: A comparison of minimal interventions via telephone and mail. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:103–113. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Brandon TH, Meade CD, Herzog TA, Chirikos TN, Webb MS, Cantor AB. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a minimal intervention to prevent smoking relapse: Dismantling the effects of content versus contact. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:797–808. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chirikos TN, Herzog TA, Meade CD, Webb MS, Brandon TH. Cost- effectiveness analysis of a complementary health intervention: The case of smoking relapse prevention. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2004;20 doi: 10.1017/s0266462304001382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention: Theoretical rationale and overview of the model. In: Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Relapse prevention. Guilford; New York: 1985. pp. 3–70. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shiffman S, Shumaker SA, Abrams DB, Cohen S, Garvey A, Grunberg NE, et al. Models of smoking relapse. Health Psychology. 1986;5(Suppl):13–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Brandon TH, Simmons VN, Meade CD, Quinn GP, Khoury ENL, Sutton SK, Lee JH. Self-help booklets for preventing postpartum smoking relapse: A randomized trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:2109–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Quitting Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2001-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;60(44):1513–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Westmaas JL, Bontemps-Jones J, Bauer JE. Social support in smoking cessation: Reconciling theory and evidence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;7:695–707. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Meade CD, Byrd JC. Patient literacy and the readability of smoking education literature. American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79:204–205. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Meade CD. Community Health Education. In: Nies MA, McEwen M, editors. Community Health/Public Health Nursing: Promoting the Health of Populations. 6thd ed. in press. [Google Scholar]

- [22].National Cancer Institute . Clearing the air: Quit smoking today. 2003. NIH Publication No. 03-1647. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mermelstein R, Cohen S, Lichtenstein E, Baer JS, Kamarck T. Social support and smoking cessation and maintenance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:447–453. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Biener L, Abrams DB. Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO. Relapse situations and self-efficacy: An integrative model. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:271–283. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90070-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Copeland AL, Brandon TH, Quinn EP. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire - Adult: Measurement of smoking outcome expectancies of experienced smokers. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:484–494. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Simmons VN, Heckman BW, Ditre JW, Brandon TH. A measure of smoking abstinence-related motivational engagement: development and initial validation. Nicotine Tobacco Research. 2010;12:432–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq020. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. Client satisfaction questionnaire-8 and service satisfaction scale-30. In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cohen DR, Fowler GH. Economic implications of smoking cessation therapies: a review of economic appraisals. Pharmacoeconomics. 4:331–44. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Berman M, Crane R, Seiber E, Munur M. Estimating the cost of a smoking employee. Tob Control. 2013 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050888. E-pub ahead of publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cowan B, Schwab B. The incidence of the healthcare costs of smoking. J Health Econ. 2011;30:1094–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hockenberry JM, Curry SJ, Fishman PA, Baker TB, Fraser DL, Cisler RA, Jackson TC, Fiore MC. Healthcare costs around the time of smoking cessation. Am J Pre Med. 2012;42:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Rochon J. Application of GEE procedures for sample size calculations in repeated measures. Stat Med. 1998;17:1643–1658. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980730)17:14<1643::aid-sim869>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Elfeddali I, Bolman C, Candel MJ, Wiers RW, de Vries H. Preventing smoking relapse via Web-based computer-tailored feedback: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e109. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(44):889–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Naughton F, Jamison J, Boase S, Sloan M, Gilbert H, Prevost AT, Mason D, Smith S, Brimicombe J, Evans R, Sutton S. Randomized controlled trial to assess the short-term effectiveness of tailored web-and text-based facilitation of smoking cessation in primary care (iQuit in Practice) Addiction. 2014 doi: 10.1111/add.12556. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Benowitz NL, Jacob P, III, Ahijevych K. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Snow MG. Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:23–41. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Marcus BH, Lewis BA, Williams DM, Dunsiger S, Jakicic JM, Whiteley JA, Albrecht AE, Napolitano MA, Bock BC, Tate DF, Sciamanna CN, Parisi AF. A comparison of Internet and print-based physical activity interventions. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:944–949. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Strecher V. Internet methods for delivering behavioral and health-related interventions (eHealth) Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:53–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]