Abstract

Background

Interventions requiring abstinence from alcohol are neither preferred by nor shown to be highly effective with many homeless individuals with alcohol dependence. It is therefore important to develop lower-threshold, patient-centered interventions for this multimorbid and high-utilizing population. Harm-reduction counseling requires neither abstinence nor use reduction and pairs a compassionate style with patient-driven goal-setting. Extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX), a monthly injectable formulation of an opioid receptor antagonist, reduces craving and may support achievement of harm-reduction goals. Together, harm-reduction counseling and XR-NTX may support alcohol harm reduction and quality-of-life improvement.

Aims

Study aims include testing: a) the relative efficacy of XR-NTX and harm-reduction counseling compared to a community-based, supportive-services-as-usual control, b) theory-based mediators of treatment effects, and c) treatment effects on publicly funded service costs.

Methods

This RCT involves four arms: a) XR-NTX+harm-reduction counseling, b) placebo+harm-reduction counseling, c) harm-reduction counseling only, and d) community-based, supportive-services-as-usual control conditions. Participants are currently/formerly homeless, alcohol dependent individuals (N=300). Outcomes include alcohol variables (i.e., craving, quantity/frequency, problems and biomarkers), health-related quality of life, and publicly funded service utilization and associated costs. Mediators include 10-point motivation rulers and the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. XR-NTX and harm-reduction counseling are administered every 4 weeks over the 12-week treatment course. Follow-up assessments are conducted at weeks 24 and 36.

Discussion

If found efficacious, XR-NTX and harm-reduction counseling will be well-positioned to support reductions in alcohol-related harm, decreases in costs associated with publicly funded service utilization, and increases in quality of life among homeless, alcohol-dependent individuals.

Keywords: alcohol dependence, extended-release naltrexone, harm reduction, homelessness, alcohol treatment

Introduction

Alcohol dependence occurs 10 times more among homeless people than in the general population;1,2 thus, homeless individuals are disproportionately affected by alcohol-related morbidity and mortality.3 As a result, many homeless, alcohol-dependent people become frequent users of high-cost healthcare and criminal justice services and thereby place heavy utilization and cost burdens on publicly funded systems.4-6

Unfortunately, research has shown that interventions requiring abstinence (referred to hereafter as ‘abstinence-based treatments’) are not always effective for this population.7-9 Moreover, most homeless individuals with alcohol dependence never go to, are turned away from, or drop out of these treatments.10-12 Various factors, including lack of insurance and difficulties accessing treatment,11 have been cited as barriers to engagement. However, research has indicated that lack of interest in abstinence-based treatment poses one of the most sizable barriers to engagement.13-15

Nonabstinence-based approaches, including low-threshold supportive housing (i.e., Housing First) and medically supervised alcohol administration, have been applied with this population and are associated with increased engagement, reductions in alcohol use and related problems, and decreased utilization of publicly funded services and associated costs. 5,16-18 Referred to as harm-reduction approaches, they entail compassionate and pragmatic strategies that focus on minimizing alcohol-related harm and enhancing quality of life for affected individuals and their communities without requiring abstinence or use reduction.19

Whereas service-oriented, harm-reduction approaches are proliferating, there are no evidence-based behavioral or pharmacological harm-reduction interventions to further support these efforts. To fill this treatment gap, the current study aims to test the efficacy of a combined pharmacobehavioral, harm-reduction intervention for homeless, alcohol dependent individuals. This intervention will pair a) naltrexone extended-release injectable suspension (XR-NTX; VIVITROL®), an opioid receptor antagonist shown to reduce alcohol craving and problems,20 with b) harm-reduction counseling, which supports patient-driven goals and recognizes any movement towards harm reduction and quality-of-life enhancement as steps in the right direction.21 Although the efficacy of XR-NTX has been established in a previous trial,20 no other studies to date have a) combined XR-NTX with an explicitly harm-reduction counseling approach or b) tested the efficacy of XR-NTX in this more severely affected population (i.e., homeless individuals with alcohol dependence).

The hypothesized clinical mechanisms of XR-NTX—reduced alcohol craving, decreased stimulatory effects of alcohol, increased cognitive control and reduced impulsive decision-making22—make it an ideal adjunct to harm-reduction counseling. Specifically, it allows people time and space away from alcohol craving so they can make more adaptive and healthier behavior choices towards reaching their harm-reduction goals. These hypotheses were initially supported in the preceding, single-arm pilot study (N=31) of this intervention, which showed that participants were increasingly able to generate clinically relevant harm-reduction goals and succeeded in reducing their alcohol-related harm.23,24

Study Aims and Hypotheses

The first aim of the Harm Reduction with Pharmacotherapy (HaRP) study is to test the efficacy of XR-NTX+harm reduction counseling (XR-NTX+HRC), placebo+harm reduction counseling (placebo+HRC), and harm-reduction counseling alone (HRC) compared to community-based supportive services as usual (TAU). It is hypothesized that, compared to TAU, the three active treatments (XR-NTX+HRC, placebo+HRC, HRC) will evince greater decreases in alcohol use and problems and increases in health-related quality of life. Further, the XR-NTX+HRC group will evince greater decreases in alcohol use and problems than the placebo+HRC group.

The second aim is to test potential mediators of the treatment effects. Because the three active treatments include personalized feedback, patient-driven, harm-reduction goal setting and collaborative planning for safer drinking, it is hypothesized that these groups will experience increases on motivation for harm reduction, which will mediate treatment effects on alcohol outcomes. Because one of naltrexone's putative clinical mechanisms is reduction in alcohol craving,22 it is hypothesized that the XR-NTX+HRC group will experience significant decreases on craving compared to the placebo+HRC group, which will mediate the effects of XR-NTX+HRC versus placebo+HRC on alcohol outcomes.

The third aim is to test treatment effects on costs of publicly funded service utilization. It is hypothesized that the XR-NTX+HRC, placebo+HRC and HRC groups will show greater decreases than the TAU group.

Methods

Design

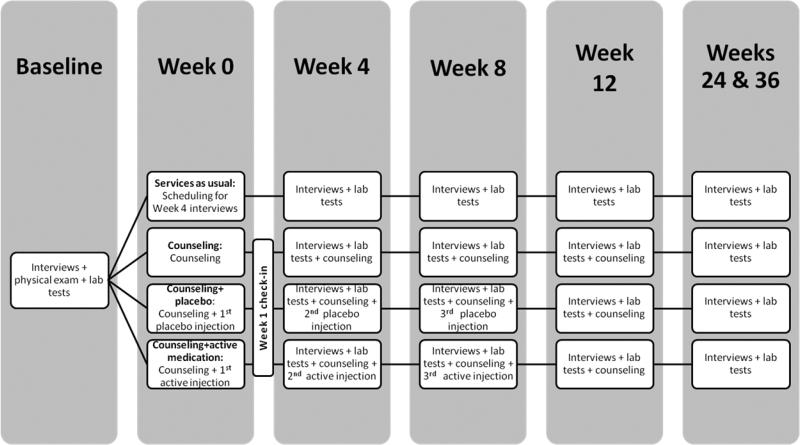

This study is a 4-arm RCT (N=300) testing the relative efficacy of XR-NTX+HRC, placebo+HRC and HRC compared to TAU (see Figure 1) in reducing alcohol use and problems, improving quality of life and decreasing publicly funded service utilization. This design differs from a fully-crossed 2x2 design because it does not include a medication+no counseling condition. The medication+no counseling condition was excluded because researchers have concluded that combining medication with medication management or psychosocial support is needed to fully realize the medication effects, and over the past decade, this combination has become the gold standard in medication trials involving naltrexone.25,26 Embedded within this larger design is also a double-blind comparison of the efficacy of XR-NTX and placebo with both participants and researchers blind to medication condition. This additional comparison is planned to potentially replicate the initial XR-NTX RCT's positive findings,20 but this time using an explicitly harm-reduction framework and within a more severely affected population. The study features a 12-week active treatment trial with a 24-week follow-up to test for potential delayed treatment effects or treatment decay.

Figure 1.

Intervention delivery and assessment timeline.

Settings

Settings include two community-based agencies on the forefront of harm-reduction housing and service provision to homeless people in a large city in the US Pacific Northwest. Both agencies serve the same general population and use a harm-reduction approach to service provision. Formerly homeless participants will be recruited from one of the agencies’ Housing First programs, which provides immediate, permanent, low-barrier, nonabstinence-based housing to homeless people with severe alcohol problems. In this model, individuals are not required to be abstinent from substances, are allowed to drink in their units and are not required to attend treatment.13,14,16 Currently homeless participants will be recruited through an agency that provides outreach, nursing care and case management to chronically homeless people on the street and in various facilities serving homeless people throughout the city. Individuals are not required to be abstinent from substances to receive these services. It is important to note that, while both agencies use a harm-reduction approach to case management, neither provides manualized harm-reduction alcohol treatment like the one described here.

Participants

Participants (N = 300) will be adults (21-65 years old) with alcohol dependence who are, or have been, homeless in the past year. We use the definition of homelessness defined in the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act27: lacking a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence; having a primary nighttime dwelling that is not a regular sleeping accommodation; living in a supervised shelter or transitional housing; exiting an institution that served as temporary residence when the individual had previously resided in a shelter or place not meant for human habitation; or facing imminent loss of housing when no subsequent residence is identified and insufficient resources/support networks exist.

Inclusion criteria include receiving services at one of the named partnering sites, being at least 21 years of age, agreeing to use an adequate form of birth control (if female and in childbearing years), and fulfilling criteria for current alcohol dependence according to DSM-IV-TR criteria as determined by the SCID-I/P.28 Exclusion criteria include refusal or inability to consent to participation in research; constituting a risk to safety and security of other agency clients or staff; known sensitivity or allergy to naltrexone/XR-NTX; concurrent participation in a clinical study involving an unapproved, experimental drug; current treatment with naltrexone/XR-NTX; being pregnant or nursing; one or more suicide attempts in the past year; renal insufficiency (serum creatinine level > 2); current opioid dependence according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria1; liver transaminase (AST, ALT) levels > 5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN)2; a clinical diagnosis of decompensated liver disease; or other condition deemed by Principal Investigator and/or Medical Director to make study participation clinically unsafe.

Measures and Materials

Measures for determining eligibility

Ability to consent is assessed during the information session using the UCSD Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent (UBACC).29 This 10-item, 3-point Likert-scale measure ensures participants understand the study protocol, potential risks/benefits and their rights as participants prior to study enrollment. The Alcohol Use Disorders Inventory Checklist – Consumption (AUDIT-C),30,31 which is a three-item, psychometrically sound measure of problem alcohol use, is used to screen participants for potential alcohol dependence prior to study recruitment. We use a cut-off score of ≥ 4 points, which is highly sensitive for detecting AUDs.32,33 The Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) is a reliable and valid tool to assess suicidal ideation and behavior.34 It is used to assess participants’ current suicidality to determine eligibility at baseline and is regularly assessed to track suicide risk in weeks 4-36. Further, the Self-injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview-Suicide Attempts subscale (SITBI-SA),35 which measures lifetime experience of suicidal behaviors, is likewise used to help determine eligibility at baseline and is administered at all subsequent assessment time points to track risk (weeks 4-36). The alcohol and opioid dependence parts of the DSM-IV-TR SCID-I/P28 are used to document fulfillment of inclusion/exclusion criteria at baseline and are re-administered in Weeks 4-36.

Measures for sample description

The Personal Information Questionnaire (PIQ) assesses age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, employment, military experience, other research study participation and experience of homelessness in the past year.36 The Housing Timeline Followback (TLFB-H)37,38 is a set of calendars that documents housing status by recording where participants resided/spent the night each day in the past 30 days or since the previous assessment, as applicable. The TLFB-H is used to describe the baseline sample and as a time-varying covariate in efficacy analyses. The Tracking Information Sheet collects contact information from participants to facilitate follow-up communication and tracking over the course of the study.

Measures of motivation outcomes

Motivation outcomes will serve in analyses as potential mediators of the hypothesized treatment effects. The Motivation-for-harm-reduction Ruler comprises four, 10-point scales assessing participants’ motivation, readiness, importance and confidence to “make changes to reduce the negative side effects you experience from drinking.” This represents readiness to engage in alcohol harm reduction. Such 10-point, single-item motivation scales have been shown to be valid and clinically useful measures of motivation across various populations.39-41

Measures of alcohol-use outcomes

The Alcohol and Substance-use Frequency Assessment questions were adapted from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI),42 and are used to assess frequency of use of alcohol and other drugs over the past thirty days. The Alcohol Quantity Use Assessment (AQUA) was created in the context of a previous study with this population5 and was refined in the pilot study23 to better capture alcohol consumption that does not conform to traditional standard drink measures (e.g., sharing bottles, consuming beverages from large-volume containers [e.g., 16, 24 and 40 oz. bottles and cans], and use of nontraditional alcohol forms [e.g., high-gravity malt liquor, nonbeverage alcohol]). As necessary when a memory aid is needed, we also use a set of monthly calendars to allow for prospective or retrospective evaluation of alcohol and other drugs for each day of the previous month.37 The Short Inventory of Problems (SIP-2R) is a 15-item, Likert-scale questionnaire that measures social, occupational and psychological alcohol-related problems over the past 30 days.43 The summary score will serve as the alcohol-related problems outcome measure. Alcohol craving over the past week is measured using the psychometrically valid, 5-item, Likert-scale Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS).44 The alcohol craving summary score will be used in analyses as a mediator of the hypothesized treatment effects. Timeframes and administration techniques for these questionnaires were established and refined during the pilot study to ensure feasibility.

Measures of quality-of-life outcomes

The Short Form-12 (SF-12)45 is a well-validated, 12-item questionnaire that assesses health-related quality of life over the past thirty days in two primary areas: physical and mental health. This measure is used at baseline and all subsequent assessment sessions.

Measures supporting medication management

The Case Report Form (CRF) is used to a) summarize clinically relevant assessment data for the study interventionists (e.g., alcohol-use disorder diagnosis, fulfillment of inclusion/exclusion criteria); b) compile and centralize key lab test findings; c) provide an outline during the physical exam and medication management; d) record clinical data during the physical exam and medication management sessions; and e) document participant-generated harm-reduction goals and safer drinking strategies. The Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Effects (SAFTEE) interview,46,47 which was tailored for use with this medication, includes open-ended, categorical and Likert-scale questions assessing symptoms that correspond to potential adverse events associated with XR-NTX. This measure is embedded in the CRF and is administered at baseline and all subsequent sessions with the study interventionists.

Measures for utilization and cost analysis

Similar to our team's work on a prior study with this population,5 administrative data on publicly funded service utilization will be obtained from the King County Correctional Facility, King County Medic One/Emergency Medical Services, Harborview Medical Center (HMC), and the Washington State Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System (CHARS) for the 2-year pre-study period through the 36-week assessment time point. We obtain participant consent and HIPAA authorizations for these data at the information session. Specific data collected include: a) number of Medic One/EMS dispatches and associated costs; b) number of ED visits and associated costs; c) number of inpatient hospital admissions, outpatient visits and total costs per admission (CHARS and HMC); d) number of bookings, length of stay and daily cost for the King County Correctional Facility. These data will be used to create overall cost outcomes. Costs will represent cost incurred by the use of the service regardless of the payer.

Treatment integrity materials and measures

Manual adherence and competence for the HRC, placebo+HRC and XR-NTX+HRC sessions are being measured using the HaRP Adherence and Competence Coding Manual and the HaRP Coding Scale. The coding system, which is based on the COMBINE Study Medical Management Adherence Checklist and coding schema,48,49 consists of 6 dimensions to assess delivery of the HaRP style and content (i.e., informativeness, direction, authoritativeness, warmth, manual adherence, avoidance of nonmanualized components). This measure will be used to rate audio recordings of the sessions by advanced undergraduate students trained in the study treatment and supervised by the study PI. Dimensions are rated on 7-point Likert scales, where 0 = “absence of the characteristic” and 6 = “very high levels of the characteristic (within top 10% of providers).” The Participant Satisfaction Assessment is a semistructured interview with open-ended questions and prompts to assess participants’ receipt of and satisfaction with the study procedures at the final assessment.

Lab tests and materials

Blood tests are conducted with all participants at baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12, 24 and 36, and include a complete blood count (CBC), a metabolic panel (COMP; including AST, ALT, albumin, bilirubin total and direct) and GGT. These tests are conducted to assess liver and renal functioning and to detect other medical conditions that may contraindicate the use of XR-NTX or may be important to monitor during its administration. If participants in the two medication arms evince AST/ALT greater than 5 x ULN, they are retested a week prior to the next scheduled injection. If AST/ALT have not decreased below that point, the study medication is discontinued to ensure participant safety.

Urine tests include a) complete urinalysis (UA), which is used to detect further contraindicating conditions (e.g., renal damage); b) a urine toxicology dipstick, which is used in the injection conditions to detect the presence of opioids; c) an hCG dipstick pregnancy test for women in childbearing years at baseline and prior to injections; and d) ethyl glucuronide (EtG) tests,50 which are used to validate self-reported alcohol use at each assessment. Concentration of EtG, which is a metabolite of ethyl alcohol formed in the body by glucuronidation after ethanol exposure, will be used as a quantitative measure. Previous studies have shown that EtG is positively associated with self-reported alcohol quantity, 51,52 and EtG tests can detect drinking over the past 2 days, up to 80 hours.50

Treatment Conditions

TAU

The most minimal condition is TAU, which comprises the agencies’ harm-reduction oriented supportive services as usual that are provided to all participants in all groups for the duration of the trial and beyond. Depending on the agency and the patients’ needs, supportive services include provision of emergency shelter and/or permanent, supportive housing; outreach services; intensive case management; nursing/medical care; access to external service providers, as needed (e.g., more intensive medical or psychiatric treatment, chemical dependency counseling); and assistance with basic needs (e.g., food, clothing, income, housing).

HaRP treatment style and components

The remaining three arms (XR-NTX+HRC, placebo+HRC and HRC) are considered active treatment conditions and include monthly, alcohol-specific harm-reduction counseling sessions that are delivered by study interventionists. The HaRP treatment manual was developed during a prior pilot study specifically for this population;23 however, the structure of the sessions was informed by procedures from the COMBINE Study and other naltrexone medication management manuals.48,53

The HaRP treatment style draws on the nonjudgmental, compassionate stance; unconditional positive regard; and acceptance of clients that was pioneered in humanistic psychotherapy and MI and has been influenced by the development of harm-reduction psychotherapy.54-56 Because HaRP treatment goals are fully client-driven, however, this approach differs from more directive, evidence-based approaches, such as MI, in which clients “are intentionally guided toward what the counselor regards to be appropriate goals” (p.120).41 These more directive approaches either a) overtly assume clients have use-reduction or abstinence-based goals (e.g., relapse prevention57) or b) seek to align clients with and solidify commitment to provider-endorsed goals (e.g., cue exposure, aversion and contracting in behavioral therapy; cognitive restructuring and coping skills in CBT; advice-giving in SBIRT, prize incentives in CM; developing and resolving discrepancy in MI).41,57-59 The HaRP's shift from a more provider- to a more patient-driven treatment style and focus is not only novel, it is necessary to reach a population that otherwise does not present for, successfully complete or maximally benefit from existing abstinence-based or even use-reduction treatments.7,8,10-12

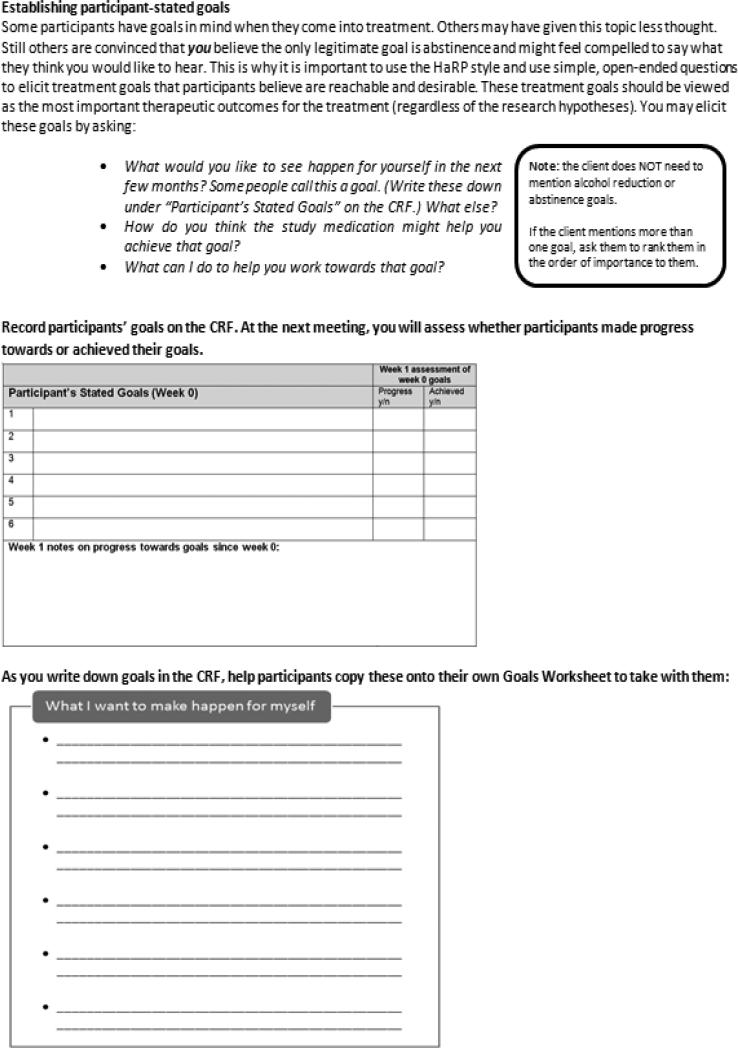

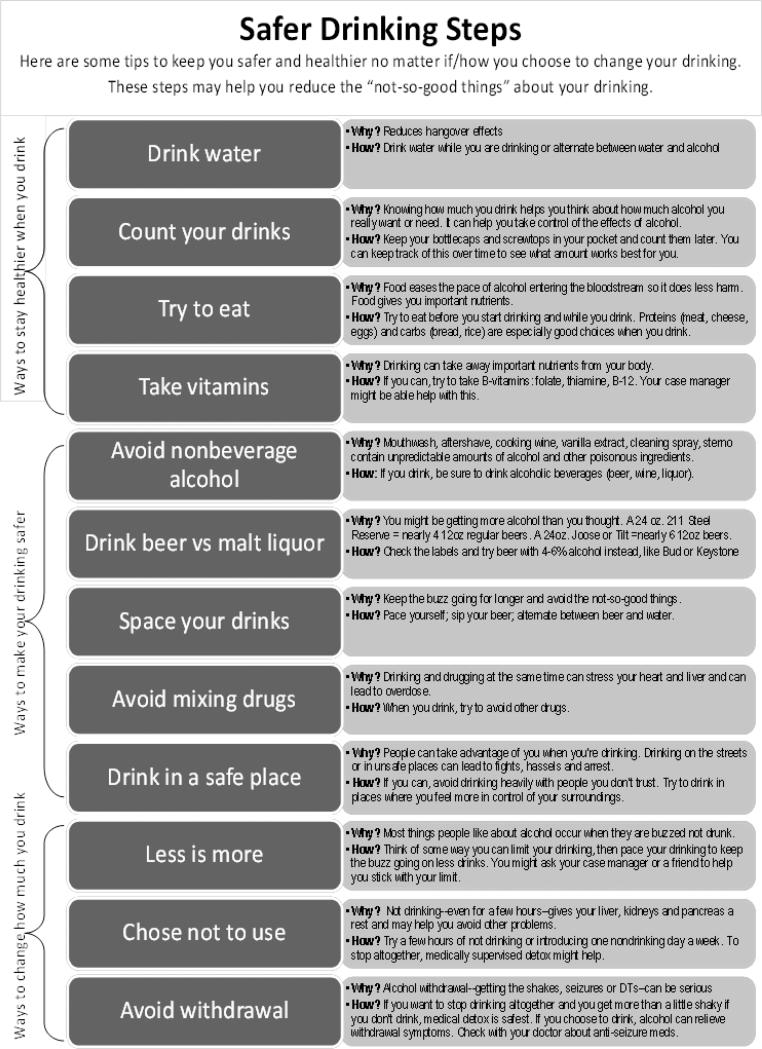

In addition to the patient-driven focus and style, the HaRP treatment conditions comprise specific, manualized components. For the HRC group, interventionists a) obtain medical history (baseline only), b) assess vital signs and concomitant medications, c) conduct a brief physical exam (baseline only), d) assess for adverse events using the SAFTEE, e) provide personalized feedback about alcohol assessments and lab tests--but avoid labelling, f) elicit participants’ own harm reduction goals and progress made towards them (see Figure 2), and g) discuss and secure commitment for safer drinking using the Safer Drinking Strategies worksheet (see Figure 3). These manualized components have been tested in the pilot study23 preceding the present RCT and are based on both harm reduction theory19 and clinical practice56 as well as evidence-based motivational enhancement.41,60 Study interventionists use the HaRP treatment manual to guide the session and record participants’ in-session data on the CRF.

Figure 2.

Harm-reduction goal elicitation protocol and forms.

Figure 3.

Safer drinking tips are introduced by study interventionists with the following prompts: 1) If they have already mentioned wanting to reduce their drinking, this can be pointed out on the list, and this goal can be reinforced as a step towards safer drinking. 2) Inquire if they have ever done any of the things on the list to reduce the harm they experience while drinking. For example,“This is a list of things that you can do to drink more safely. Have you ever tried doing anything on this list before?” If so, ask participants: “How did that go?” or “What was that like for you?” Support participants’ self-efficacy by reinforcing these efforts. For example, “It's great that you have been able to keep from drinking while you sell your Real Change papers. What made you decide to do that? How were you able to do that?” 3) Ask if they would be willing to choose a couple of safer drinking tips over the next month (or until the next appointment)—circle these for participants and note these on the CRF under “Participant's Safer Drinking Plan.” 4) Inform participants you will check in with them during the next meeting about their safer drinking plan to see how it worked out for them. 5) Participants should receive the safer drinking tips handout (with their harm reduction goals on the back) to take with them.

The XR-NTX+HRC and placebo+HRC conditions receive the same components as the HRC condition listed above plus medication management (i.e., discussing the medication, side effects and ways to manage them; ensuring participants have medication ID tags; providing emergency contact information) and XR-NTX (at weeks 0, 4 and 8).

The XR-NTX and placebo preparations used in this study are provided by Alkermes, Inc. The preparations consist of microspheres of 100-μm diameter that either contain naltrexone or do not (placebo) and are suspended prior to administration in a PLG polymeric matrix. PLG is a common biodegradable medical polymer with an extensive history of human use in extended-release pharmaceuticals. Following the injection, naltrexone is released from the microspheres, yielding peak concentrations within three days. Thereafter, by a combination of diffusion and erosion, naltrexone is released for more than thirty days. The placebo preparation consists of an identical formulation of microspheres (not containing naltrexone) within a PLG polymeric matrix to ensure study staff and participants are blind to medication condition.

Staff Training

Staff trainings were developed during the prior pilot study. They occur prior to placement in the field and throughout the study. Research ethics and integrity are addressed in staff training and in weekly supervision. All research staff complete human subjects, HIPAA and blood-borne pathogen training and sign confidentiality agreements prior to data collection.

Study assessment staff

A research social worker conducts assessment interviews under the weekly supervision of the PI, who is a licensed clinical psychologist with over 16 years of experience conducting substance-use treatment and assessment. Designed during the pilot study,23 a 16-hour, in-person assessment training protocol is used prior to staff placement in the field (e.g., probe instructions, skip patterns, assessment scoring, suicide risk protocols, boundary navigation, crisis management and de-escalation). Training also includes written instructions and mock interviews with feedback. All sessions are audiorecorded to facilitate supervision, and in-person observations by the PI occur monthly throughout the data collection period.

Study interventionists

Study interventionists are a) licensed medical doctors who have completed a psychiatry residency and have either completed or are completing an addiction psychiatry fellowship or b) registered nurses completing their final practicum for the advanced Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) degree. Training on treatment delivery comprises 16 hours of in-person training, including written instructions and review of the manual, role-plays, and feedback. Study interventionists audio record all sessions to facilitate supervision and treatment integrity analyses and are observed in person by the PI on a monthly basis.

Treatment integrity coders

A separate group of research staff (i.e., advanced undergraduate students) are conducting treatment integrity coding and are likewise trained in these methods using a tailored 16-hour protocol and are supervised biweekly by the PI, who has extensive experience designing and evaluating treatment integrity measures for substance abuse treatments.61-65

Procedures

All procedures have been approved by the institutional review board at the home institution and are being carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving human participants. A certificate of confidentiality was obtained from NIH to further protect identifiable research records from forced disclosure (e.g., legal subpoena). Written, informed consent is being obtained from all participants prior to their study involvement.

Prior to recruitment, agency and research staff notify agency clients of the opportunity to participate in the study, and informational flyers are posted throughout the agencies and/or distributed to individuals. Research staff are then placed onsite at agency centers in planned, yearly rotations to conduct information sessions and baseline assessments with interested agency clients. During the information sessions, research staff briefly explain the study and ask individuals about their initial interest in participation. Research staff then obtain verbal consent to administer the AUDIT-C to initially screen for potential eligibility. If individuals meet the initial screening cut-off (≥4), research staff explain the study procedures, participants’ rights and informed consent materials. Next, the UBACC is administered to assess capacity to provide informed consent. Potential participants receive $5 for attending the information session, regardless of their decision, ability or qualification to participate. If they initially screen in and agree to participate, written informed consent for the study is obtained, and participants may elect to complete the baseline assessment or schedule it for a later date.

At baseline sessions, research staff administer the measures mentioned above. Next, study interventionists conduct a brief medical history, SAFTEE, physical exam and collect blood and urine samples for lab testing. Participants are compensated $20 for their time and are scheduled for the Week 0 meeting the following week. During the interim week, the research team discusses lab results to determine inclusion and exclusion criteria fulfillment. Research staff notify the medical center pharmacy of new study recruits. Independent of the research team, the pharmacy performs permuted block randomization stratified by site and current housing status66 and informs research staff of participants’ randomization to receive a) medication (blinded active or placebo), b) HRC or c) TAU.

All consenting participants attend a Week 0 appointment with the study interventionists where they are told whether they qualify for the study. Those who do not qualify receive feedback about their lab tests and alcohol use, are told why they did not qualify, and are provided with harm reduction counseling. Study qualifiers randomized to the XR-NTX+HRC, placebo+HRC or HRC conditions receive their specified Week 0 treatment content (see Treatment Conditions) and are scheduled for the Week 1 follow-up. All active treatment groups (XR-NTX+HRC, placebo+HRC, HRC) receive additional treatment components at weeks 1, 4, 8 and 12. Those who are assigned to the TAU condition are scheduled for their Week 4 assessment. All participants attend additional assessment sessions at weeks 4, 8, 12, 24 and 36 (see Figure 1). Participants are paid $20 for each appointment they attend. To ensure participant retention, we use procedures honed in previous studies with these agencies. At each session, participants are asked to update their contact information and receive appointment slips including the time, place and contact person for their next appointment. Prior to all appointments, reminder calls are made to participants, or with their written permission, to agency staff at their respective sites and/or contacts of their choosing. As necessary and determined safe, the research team may arrange to meet participants for sessions in an alternate location of the participants’ choosing or may arrange transportation for the participant (via program staff) to the community-based research site.

Data Analysis Plan

Preliminary Data Analyses

When all study data are obtained, they will be screened for missing cases, outliers, and normality of distributions (as relevant) using descriptive statistics and plots. Study completers and noncompleters will be compared on drinking and demographic variables to detect potential systematic attrition and missing data patterns. Baseline data will also be examined to detect possible group differences on the main outcome variables. These will be statistically controlled as covariates in main outcome analyses to ensure group equivalence, as necessary.

Analyses of Manual Adherence and Interventionist Competence

Trained coders will assess the adequacy of treatment delivery by comparing expected study interventionists’ behavior with audio recordings of sessions to detect degree of competence with and adherence to the HaRP treatment manual. We will conduct descriptive analyses to demonstrate level of adherence and competence on each of the 6 dimensions represented in the HaRP Adherence and Competence Coding Manual and the HaRP Coding Scale.

Primary Outcome Analyses

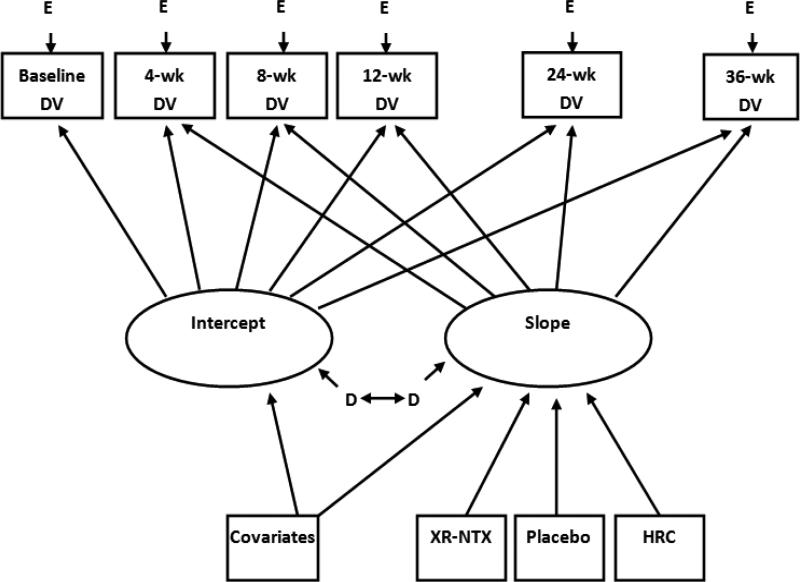

Primary outcome analyses will comprise a series of latent growth curve models utilizing appropriate probability distributions for the outcome variables (e.g., Poisson, negative binomial, Gaussian, logistic). Growth modeling examines individuals’ outcome trajectories and covariate effects on these trajectories over time.67 Growth modeling will be conducted using Mplus 7.11, which incorporates a generalized latent framework and allows for a wide array of variable types, estimation methods and longitudinal modeling options.68

Outcomes measured at each time point will serve as indicators of the intercept (i.e., baseline) and slope (i.e., change in outcomes over time). Treatment group will serve as the primary predictor of slope. Covariates (e.g., housing status, agency, number of sessions attended) will serve as additional predictors of intercept or slope, as necessary. Outcome variables are based on established standards in the alcohol-use literature69-71 and our own studies in similar populations.5,16

Analyses for aim 1 will feature growth models to test treatment effects on 30-day alcohol and quality-of-life outcomes: peak alcohol quantity, drinking frequency, alcohol-related problems and the physical and mental health scales of the SF-12 (see Figure 4). In secondary analyses, we will additionally test the treatment effects on the EtG/creatinine ratio to validate the primary, self-report outcomes. Although the proposed alcohol outcomes differ from those typically encountered in clinical drug trials, they were deemed appropriate for the proposed study aims and population. First, most naltrexone studies have used an abstinence-based treatment model and have thereby employed complementary, abstinence-oriented outcomes (e.g., days to relapse, percent days abstinent). Because we are following a harm-reduction treatment model, we, too, deemed it important to focus on complementary outcomes: reduced alcohol use and problems as well as enhanced quality of life. Second, the baseline assessment during our pilot study indicated participants had a 30-day median drinking frequency of 30 days and a peak alcohol quantity of 30 drinks.23 Given the extent of alcohol use in this population, abstinence-based outcomes would be blunt instruments that would not capture nuanced longitudinal changes in alcohol use and problems. Finally, in keeping with the harm-reduction philosophy, we are assessing multiple outcomes to reflect the various pathways by which individuals might change their drinking to achieve reductions in alcohol-related harm and improvements in quality of life.

Figure 4.

Hypothesized primary intervention model. “Intercept” is the baseline measurement of the outcome variable (DV). HRC = harm reduction counseling only. “Slope” represents change in the DV over time. DV= outcome or dependent variable. D=latent variable disturbance (error). E=measured variable error.

We also acknowledge that two of the four primary outcomes focus on alcohol-use reduction, which is not necessary to document harm reduction. On the other hand, harm reduction does not preclude use reduction as a potential patient-driven goal. Thus, as long as they are proposed by the participant, use reduction and abstinence-based goals are recognized as a potential means to achieve harm reduction.19 We also deemed it important to document outcomes that are considered to be gold standards, such as alcohol quantity and frequency,72 so that some outcomes from this trial would be comparable to those in the larger alcohol treatment literature. For these reasons, we have included consideration of quantity/frequency outcomes that reflect use reduction in addition to more explicitly harm reduction outcomes, such as alcohol-related problems and quality of life.

For aim 2, we will be testing longitudinal changes on secondary, theoretical variables as mediators of the treatment effects on alcohol outcomes. In testing motivation as a mediator, growth analyses will be conducted to determine whether the three active treatment groups are associated with significant increases in motivation to change drinking in a way that reduces harm. If this is the case, the alcohol growth model, established in analyses for aim 1, and the motivation growth model will be combined into a single parallel process growth model.73 The mediation effect will be tested by taking the product of coefficients (αβ), where α=the regression of the slope of the mediator on the dummy-coded intervention variables and β=the regression of the slope of the alcohol outcome variable on the slope of the mediator, using the asymmetric confidence interval (CI) approach.74 This same procedure will be used to test whether XR-NTX+HRC produces significantly greater decreases in alcohol craving than in the placebo+HRC group and whether those decreases in craving are in turn associated with decreases on alcohol outcomes.

Because homeless people with alcohol dependence disproportionately use costly medical and criminal justice services,4-6 it is important to assess the impact of interventions for this population on publicly funded service costs. Our analyses for aim 3 will therefore assess relative effects of the 3 active treatments (i.e., XR-NTX+HRC, placebo+HRC and HRC) compared to TAU on costs stemming from: a) the number of emergency medical service dispatches; b) number of ED visits; c) number of inpatient hospital admissions; d) number of bookings and length of stay at the King County Correctional Facility. As in analyses for aim 1, this analysis will feature a growth model in which the mean monthly costs during 3 time points (i.e., 2 years prior to baseline, during the 12 weeks of treatment, and during the 24-week follow-up) will serve as indicators of the latent variables. We will use the mean monthly costs to account for the differing lengths of the time points. The 3 active treatment groups will serve as dummy-coded variables predicting the cost slope, which is expected to decrease at a significantly greater rate for the XR-NTX+HRC, placebo+HRC and HRC groups (in descending order) compared to the TAU group.

Power analyses

Using Mplus 6.11,68 we conducted Monte Carlo studies to estimate power for the primary outcome analyses to be conducted for aims 1 and 3. Data were generated from a population with hypothesized parameter values, 10,000 samples were drawn at random, and model parameters were estimated for each sample. A significance level of α = .05 was assumed for the hypothesized treatment effects for each of the outcome variables. Residual variance was set at .09, which is a representative value for this model type75 and corresponds to calculations based on data from our prior studies in a similar population.5,16 For the comparison of the three treatment groups with TAU, we assumed a follow-up attrition rate of 20%,5,23 and a Monte Carlo study indicated power (β-1) of .92 to detect a small-to-medium effect (γ=.15) for HRC and placebo+HRC and β-1=.99 to detect a medium effect for XR-NTX+HRC (γ=.2; corresponding to Cohen's d=.63; following suggestions by Muthén and colleagues75) compared to TAU across outcomes. For the comparison of active medication and placebo, power was adequate (β-1=.83) to detect a medium effect (γ=.2) for XR-NTX+HRC compared to placebo+HRC (N=150) across outcomes. These estimated effect sizes were deemed appropriate given findings from prior studies with this population5,16 and with the study medication.20,76

For aim 3, assuming no missing utilization data, a Monte Carlo study indicated adequate power (β-1=.81) to detect a medium effect (γ=.2) for XR-NTX+HRC compared to TAU.75 This test will, however, be underpowered to detect the hypothesized small-to-medium (γ=.15) effects for placebo+HRC and HRC (β-1=.57). The fact that the weaker treatment effects are underpowered is not unexpected for cost analyses in smaller clinical trials.77 Although the proposed population comprises relatively high utilizers of EMS, ED, inpatient hospital and jail services, the frequency of emergency medical and criminal justice system utilization is still statistically low over the relatively short follow-up periods that are common in clinical trials. Acknowledging our decreased power, we will focus on examining outcomes of publicly-funded service utilization costs as a first step towards future efforts that would support an evaluation of these outcomes with a larger study sample over a longer period of time or in the context of future meta-analyses.

Discussion

The finding that traditional, abstinence-based alcohol treatment is minimally effective for and is not preferred by many homeless, alcohol-dependent individuals10-13,78 underscores the need for the development and evaluation of more accessible, lower-threshold and patient-centered harm-reduction interventions. The HaRP intervention, a community-based, pharmacobehavioral treatment pairing XR-NTX and harm-reduction counseling, was developed in the context of a prior, single-arm pilot study,23 and is positioned to respond to this need. In the present RCT, we are testing the efficacy of this approach in improving quality of life and reducing alcohol-related harm and costs associated with publicly funded emergency medical and criminal justice system utilization. Additionally, we are testing potential mediators of the hypothesized intervention effect (i.e., alcohol craving and motivation to engage in harm reduction).

The proposed study is designed to make contributions to research, policy and clinical applications. First, the present study will determine whether prior positive XR-NTX findings may be extrapolated to more severely affected populations. Although a previous study aimed to use oral naltrexone and XR-NTX to treat homeless individuals receiving hospital-based, medically supervised alcohol withdrawal, very low participation rates precluded the researchers’ ability to test the medications’ efficacy.79 Thus, if our recruitment proceeds as planned, this study will be the first to determine the efficacy of XR-NTX among homeless individuals with alcohol dependence.

Second, harm reduction approaches have been used to address other types of substance use (e.g., opioid/injection drug use80-82), as well as alcohol use in nonclinical populations (e.g., college drinkers60,83). With more severely affected populations, however, abstinence-based or use-reduction approaches emphasizing drinking moderation or controlled drinking goals84-87 have been the focus of study in the alcohol intervention literature generally88-94 and in the naltrexone treatment literature more specifically.95-102 The present study thereby represents the first RCT of explicitly harm- versus use-reduction or abstinence-based interventions for individuals with alcohol-use disorders. Specifically, the harm-reduction interventions in this study include feedback regarding the effects of alcohol on their health, elicitation of participants’ own harm-reduction goals, and the provision of a menu of safer drinking options that can help participants buffer the effects of alcohol on their body (e.g., taking B complex vitamins, staying hydrated, eating before/during drinking), make changes to the manner in which they drink (e.g., counting their drinks, drinking in a safer place) and/or safely change the amount they drink (e.g., decreasing their use, engaging in nondrinking activities for periods of sobriety throughout the day, reducing towards abstinence while preventing withdrawal). If the findings of this first RCT support its efficacy, alcohol harm-reduction treatment has the potential to increase the reach of alcohol treatments to those who would not otherwise present for them.

Third, this study will test XR-NTX as an alcohol-specific treatment adjunct to the harm-reduction service provision currently offered by our partnering agencies in the community where participants receive services and shelter. In doing so, the present treatment meets patients where they are at in the community thereby removing traditional barriers to engagement.12 The HaRP intervention will be more easily transportable to community settings because it has been developed for the community, in the community, and with the community it aims to serve. Thus, this study effectively closes the research-practice gap.

Fourth, the four-arm study design will allow us to dismantle the intervention effects to determine which aspects of the treatments contribute to longitudinal changes on outcomes. Whereas most medication studies focus only on the effects of an active medication versus a simulated medical intervention (placebo), the present study will allow us to determine the potentially incremental contributions of harm-reduction counseling, simulated medical intervention (placebo) and active medication above and beyond services as usual in the community. Considering the high cost of the active medication and the medical personnel needed to administer it, such a dismantling design will allow for consideration of less expensive options, such as the use of harm reduction counseling alone.

Finally, both the pilot and present study have generated interest and collaboration among scientists, clinicians, community-based agencies, the pharmaceutical industry as well as local, state and federal government agencies. On the one hand, many of these parties are invested in finding treatments that address high utilizers of publicly funded services. On the other hand, the only alcohol treatments currently available to uninsured and Medicaid-insured individuals in Washington State are abstinence-based, and XR-NTX is not available for Medicaid-insured individuals who have not achieved abstinence and are not attending abstinence-based treatment. If findings indicate that harm-reduction counseling and XR-NTX reduce alcohol-related harm and associated costs, this study could provide empirical support for policy changes to broaden the spectrum of publicly funded treatment options.

Conclusions

Prior RCTs have tested the efficacy of XR-NTX combined with use-reduction counseling in the general alcohol dependent population20,103 and have tested the feasibility of use reduction supported by XR-NTX among homeless patients.23,79 In contrast, the current study is the first randomized controlled trial examining XR-NTX as a support for patient-driven, harm-reduction goals instead of provider-driven use-reduction or abstinence-based goals. This RCT is necessary to determine the empirical support for XR-NTX and harm reduction counseling to support reduction in alcohol-related harm and improvement in quality of life among homeless individuals with alcohol dependence.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by a research program grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1R01AA022309-01; PI: Collins), and is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01932801). The active medication and placebo injections are being provided by Alkermes, Inc. Neither NIAAA nor Alkermes, Inc. had a role in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

The authors thank the following individuals for their contributions: staff and management at collaborating agencies--the Downtown Emergency Service Center, Evergreen Treatment Services’ REACH program, Dutch Shisler Sobering Support Center, and King County Mental Health Chemical Abuse and Dependency Services (MHCADSD)--who have helped us plan and implement the study procedures; our research coordinator, Emily Taylor; our assessment specialist, Cat Cunningham; our study interventionists, Dr. Ali Bright, Dr. Jonathan Buchholz, and Naomi True; Brigette Blacker, Shawna Greenleaf, Laura Haelsig, Alyssa Hatsukami, Patrick Herndon, Jennifer Hicks, Gail Hoffman, Connor Jones, Greta Kaese, James Lenert, Victorio King, Molly Koker and Mengdan Zhu for their help with data entry, data cleaning, adherence coding, and their conveyance of medications, lab samples and study materials; our consultants, Drs. Craig Bryan, Patt Denning, Bonnie Duran, and JC Garbutt; our DSMB members, Drs. Dave Atkins, Kathy Bradley, Maggie Shuhart, Christine Yuodelis-Flores; Leah Miller, Dolly Morse, Dr. Karen Moe, Dr. Jeff Purcell and Committee D for their assistance with our human subjects applications. Most of all, we would like to thank the study participants for their role in this research and for helping us understand the meaning of harm reduction.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement regarding potential conflict of interest

Dr. Saxon serves on the Scientific Advisory Board for Alkermes and as speaker for Reckitt Benckiser. Dr. Ries serves as speaker for Alkermes, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and has served in the past as speaker for Reckitt Benckiser. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest pertaining to this manuscript.

People with current opioid dependence were excluded because XR-NTX is an opioid receptor antagonist, and if administered to a currently opioid dependent individual, would cause opioid withdrawal. In order to provide XR-NTX safely, the individual would have to be medically withdrawn from opioids, and by default, alcohol as well. Because the focus of the study is to use the medication among individuals who are current alcohol users, this kind of design would be unfeasible for this study's population.

We chose a higher cut-off for AST and ALT (5xULN) than is the case in many other studies involving naltrexone. First, we did not want to artificially truncate the target population, homeless people with alcohol dependence, by excluding the more severely affected side of the spectrum. This could affect the internal validity of the study by biasing the findings towards less severely affected individuals and reducing our sample size thereby limiting our power to find statistically significant effects where they exist. Further, exclusion of more severely affected individuals would be at odds with the low-threshold and inclusive harm reduction framework driving the current study and interventions. Moreover, prior studies have been conducted with alcohol dependent individuals but not yet with more severely affected individuals with alcohol dependence. Thus, lowering the level unnecessarily would make it more difficult for us to test this intervention on the new, target population; a population that is underserved and severely affected but for whom very few effective treatments exist. Ensuring safety was also an important consideration. To this end, we point out that XR-NTX has not been associated with liver toxicity, and the study procedures include monthly monitoring of LFTs by our medical team, including physicians specializing in internal medicine and hepatology. After deliberation with our medical team, study consultants and Institutional Review Board, we have concluded that the 5 × ULN is better aligned with the study goals and is safe for participants.

References

- 1.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLOS Medicine. 2008;5:e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, O'Campo P, Dunn JR. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up. British Medical Journal. 2009;339:b4036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: Results from a community-based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:778–784. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, et al. Health Care and Public Service Use and Costs Before and After Provision of Housing for Chronically Homeless Persons With Severe Alcohol Problems. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:1349–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunford JV, Castillo EM, Chan TC, Vilke GM, Jenson P, Lindsay SP. Impact of the San Diego Serial Inebriate Program on use of emergency medical resources. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006;47:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerger S. Substance abuse treatment: What works for homeless people? A review of the literature. National Health Care for the Homeless Council; Nashville, TN: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang SW, Tolomiczenko G, Kouyoumdjian FG, Garner RE. Interventions to improve the health of the homeless. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2006;29:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orwin RG, Scott CK, Arieira C. Transitions through homelessness and factors that predict them: Three-year treatment outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;(Suppl. 1):S23–S39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenheck RA, Morrissey J, Lam J, et al. Service system integration, access to services, and housing outcomes in a program for homeless persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1610–1615. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenzel SL, Burnam MA, Koegel P, et al. Access to inpatient or residential substance abuse treatment among homeless adults with alcohol or other drug use disorders. Medical Care. 2001;39:1158–1169. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orwin RG, Garrison-Mogren R, Jacobs ML, Sonnefeld LJ. Retention of homeless clients in substance abuse treatment: Findings from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Cooperative Agreement Program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;17:45–66. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Dana EA, et al. Where harm reduction meets Housing First: Exploring alcohol's role in a project-based Housing First setting. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2012;23:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins SE, Malone DK, Larimer ME. Motivation to change and treatment attendance as predictors of alcohol-use outcomes among project-based housing first residents. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SAMHSA . Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville: p. MD2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins SE, Malone DK, Clifasefi SL, et al. Project-based Housing First for chronically homeless individuals with alcohol problems: Within-subjects analyses of two-year alcohol-use trajectories. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:511–519. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padgett D, Stanhope V, Henwood BF, Stefancic A. Substance use outcomes among homeless clients with serious mental illness: Comparing housing first with treatment first programs. Community Mental Health Journal. 2011;47:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9283-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podymow T, Turnbull J, Coyle D, Yetisir E, Wells G. Shelter-based managed alcohol administration to chronically homeless people addicted to alcohol. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;174:45–49. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Logan DE, Samples L, Somers J, Marlatt GA. Ch. 1 Harm Reduction: Current Status, Historical Highlights and Basic Principles. In: Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K, Larimer ME, editors. Harm reduction: Pragmatic strategies for managing high-risk behaviors. 2nd ed. Guilford; New York: 2011. http://www.guilford.com/excerpts/marlatt2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O'Malley SS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1617–1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marlatt GA. Basic prinicples and strategies of harm reduction. In: Marlatt GA, editor. Harm reduction: Pragmatic strategies for managing high-risk behaviors. The Guilford Press; New York: 1998. pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray LA, Chin PF, Miotto K. Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: mechanisms of action and pharmacogenetics. CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets. 2010;9:13–22. doi: 10.2174/187152710790966704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins SE, Duncan MH, Smart BF, et al. Extended-release naltrexone and harm reduction counseling for chronically homeless people with alcohol dependence. Substance Abuse. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.904838. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins SE, Grazioli V, Torres N, et al. Qualitatively and quantitatively defining harm-reduction goals among chronically homeless individuals with alcohol dependence. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.001. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettinati HM, Weiss RD, Dundon W, et al. A structured approach to medical management: A psychosocial intervention to support pharmacotherapy in the treatment in alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;S15:170–178. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starosta AN, Leeman RF, Volpicelli JR. The BRENDA model: Integrating psychosocial treatment and pharmacotherapy for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2006;12:80–89. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200603000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. 2009 42 USC Section 11302. [Google Scholar]

- 28.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, Research version, Patient edition (SCID-I/P) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Appelbaum PS, et al. A new brief instrument for assessing decisional capacity for clinical research. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:966–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonnell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. (ACQUIP) ftACQIP. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C). Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson DA, Smith SM, Saha TD, Rubinsky AD, Grant BF. Comparative performance of the AUDIT-C in screening for DSM-IV and DSM-V alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.029. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: An update of research findings. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck AT. Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. Pearson; San Antonio, TX: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VIM, B D. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Israel Y, Hollander O, Sanchez-Craig M, et al. Screening for problem drinking and counseling by the primary care physician-nurse team. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20:1443–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsemberis S, McHugo G, Williams V, Hanrahan P, Stefancic A. Measuring homelessness and residential stability: The residential time-line follow-back inventory. Journal of community psychology. 2007;35(1):29. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maisto SA, Krenek M, Chung T, Martin CS, Clark D, Cornelius J. A comparison of the concurrent and predictive validity of three measurs of readiness to change alcohol use in a clinical sample of adolescents. Psychological Assessment. doi: 10.1037/a0024136. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heather N, Smailes D, Cassidy P. Development of a readiness ruler for use with alcohol brief interventions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd edition. Second ed. US Guilford Press; New York: 2012. When goals differ. Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller W, Tonigan J, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville: 1995. Test manual (Vol. 4, Project MATCH Monograph Series). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1289–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey – Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson B, Ait-Daoud N, Roache J. The COMBINE SAFTEE: A structured instrument for collecting adverse events adapted for clinical studies in the alcoholism field. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;15:157–167. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine J, Schooler NR. Strategies for analyzing side-effect data from SAFTEE--A workshop held fall 1985 in Rockville, Maryland. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1986;22(2):343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettinati HM, Weiss RD, Miller WR, Donovan DM, Ernst DB, Rounsaville BJ. Medical Management Treatment Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Medically Trained Clinicians Providing Pharmacotherapy as Part of a Treatment for Alcohol Dependence. NIAAA; Bethesda, MD: 2004. COMBINE Monograph Series, Volume 2. DHHS Publication No. (NIH) 04-5289. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller WR, Moyers T, Arciniega L, Ernst DB, Forcehimes A. Training, supervision and quality monitoring of the COMBINE Study behavioral interventions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;s15:188–195. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wurst FM, Skipper GE, Weinmann W. Ethyl glucuronide - the direct ethanol metabolite on the threshold from science to routine use. Addiction. 2003;98(suppl. 2):51–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Appenzeller BM, Agirman R, Neuberg P, Yegles M, Wennig R. Segmental determination of ethyl glucuronide in hair: A pilot study. Forensic Science International. 2007;20:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones M, Jones J, Lewis D, et al. Correlation of the alcohol biomarker ethyl glucuronide in fingernails and hair to reported alcohol consumed. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(s1):16a. [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Malley SS, Corbin WR, Leeman RF, Romano D. Manual for combining naltrexone with BASICS for the treatment of heavy alcohol use in young adults. Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller WR, Rollnick S. The spirit of motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. (3rd edition). Second ed. US Guilford Press; New York: 2012. Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rogers CR. The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1957;21:95–103. doi: 10.1037/h0045357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denning P, Little J. Practicing harm reduction psychotherapy: An alternative approach to addictions. 2nd edition Guilford Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. The Guilford Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Brief interventions and brief therapies for substance abuse (Treatment Improvement Protocol [TIP] Series No. 34) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); Rockville, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Higgins ST, Petry NM. Contingency mangement: Incentives for sobriety. Alcohol Research & Health. 1999:23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chawla N, Collins S, Hsu S, et al. The mindfulness-based relapse prevention adherence and competence scale: Development, interrater reliability and validity. Psychotherapy Research. 2010;20:388–397. doi: 10.1080/10503300903544257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Collins SE, Eck S, Kick E, Schröter M, Torchalla I, Batra A. Implementation of a smoking cessation treatment integrity protocol: Treatment discriminability, potency, and manual adherence. Addictive Behaviors. 2009:34, 477–480. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosengren DB, Baer JS, Hartzler B, Dunn CW, Wells EA. The video assessment of simulated encounters (VASE): Development and validation of a group-administered method for evaluating clinician skills in motivational interviewing. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosengren DB, Hartzler B, Baer JS, Wells EA, Dunn CW. The video assessment of simulated encounters-revised (VASE-R): Reliability and validity of a revised measure of motivational interviewing skills. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bradley KA, Epler AJ, Rush KR, et al. Alcohol-related discussions during general medicine appointments of male VA patients who screen positive for at-risk drinking. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:315–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hedden SL, Woolson RF, Malcolm RJ. Randomization in substance abuse clinical trials. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy. 2006;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muthen BO. Beyond SEM: General latent variable modeling. Behaviormetrika. 2002;29:81–117. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Fifth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Babor TF, Stephens RS, Marlatt GA. Verbal report methods in clinical research on alcoholism: Response bias and its minimization. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1987;48:410–424. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carey KB. Clinically useful assessments: Substance use and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:1345–1361. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carey KB, Purnine DM, Maisto SA, Carey MP. Assessing readiness to change substance abuse: A critical review of instruments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:245–266. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Assessment of drinking behavior: Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Columbus M, editors. Assessing alcohol problems: A guide for clinicians and researchers. US Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, Khoo ST. Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10:238. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test the significance of the mediated effect. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muthén LK, Muthén B. How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;4:599–620. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weiss RD, O'Malley SS, Hosking JD, LoCastro JS, Swift R. the COMBINE Study Research Team. Do Patients with alcohol dependence respond to placebo? Results from the COMBINE Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:878–884. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sturm R, Unützer J, Katon W. Effectiveness research and implications for study design: Sample size and statistical power. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1999;21:274–283. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grazioli V, Collins SE, Daeppen J-B, Larimer ME. Perceptions of 12-step programs and associations with motivation, treatment attendance and alcohol outcomes among chronically homeless individuals with alcohol problems. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.10.009. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Friedmann PD, Mello D, Lonergan S, Bourgault C, O'Toole TP. Aversion to injection limits acceptability of extended-release naltrexone among homeless, alcohol dependent patients. Substance Abuse. 2013;34:94–96. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2012.763083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beyrer C, Malinowska-Sempruch K, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M, Sidibe M, Strathdee SA. Time to act: A call for comprehensive responses to HIV in people who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376:551–563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60928-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Vickerman P, Rhodes T, Latkin C, Hichkman M. Prevention of HIV infection for people who inject drugs: Why individual, structural, and combination approaches are needed. Lancet. 2010;376:285–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wodak A, Cooney A. Do needle syringe programs reduce HIV infection among injecting drug users: A comprehensive review of the international evidence. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41:777–813. doi: 10.1080/10826080600669579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lostutter TW, Wood BA. Harm reduction and individually-focused alcohol prevention. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction. 1993;88:315–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Second year treatment outcome of alcoholics treated by individualized behavior therapy: Results. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 1976;14:195–215. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(76)90013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McIntosh MC, Sanchez-Craig M. Moderate drinking: An alternative treatment goal for early-stage problem drinking. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1985;132:15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miller WR, Pechacek TF, Hamburg S. Group behavior therapy for problem drinkers. International Journal of Addiction. 1981;16:829–839. doi: 10.3109/10826088109038892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miller WR, Wilbourne PL. Mesa grande: A methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2002;97:265–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McQueen J, Howe TE, Allan L, Mains D, Hardy V. Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;8:CD005191. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005191.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2009;28:301–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Martin GW, Rehm J. The effectiveness of psychosocial modalities in the treatment of alcohol problems in adults: A review of the evidence. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;57:350–358. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Magill M, Ray LA. Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:516–527. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ferri M, Amato L, Davoli M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programmes for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;3:CD005032. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005032.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Garbutt JC. The state of pharmacotherapy for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:S15–S23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.O'Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Schottenfeld RS, Meyer RE, Rounsaville B. Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence. A controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:881–887. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, O'Brien CP. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O'Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, et al. Six-month follow-up of naltrexone and psychotherapy for alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:217–224. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rösner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, Soyka M. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2008;22:11–23. doi: 10.1177/0269881107078308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(Issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001867.pub2. Art. No.: CD001867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP, Rabinowitz AR, et al. The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;26:610–625. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000245566.52401.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]