Abstract

Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor subtype C (mouse MrgC11 and rat rMrgC), expressed specifically in small-diameter primary sensory neurons, may constitute a novel pain inhibitory mechanism. We have shown previously that intrathecal administration of MrgC-selective agonists can strongly attenuate persistent pain in various animal models. However, the underlying mechanisms for MrgC agonist-induced analgesia remain elusive. Here, we conducted patch-clamp recordings to test the effect of MrgC agonists on high-voltage-activated (HVA) calcium current in small-diameter dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. Using pharmacological approaches, we show for the first time that an MrgC agonist (JHU58) selectively and dose-dependently inhibits N-type, but not L- or P/Q-type, HVA calcium channels in mouse DRG neurons. Activation of HVA calcium channels is important to neurotransmitter release and synaptic transmission. Patch-clamp recordings in spinal cord slices showed that JHU58 attenuated the evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents in substantia gelatinosa (SG) neurons in wild-type mice, but not in Mrg knockout mice, after peripheral nerve injury. These findings indicate that activation of endogenously expressed MrgC receptors at central terminals of primary sensory fibers may decrease peripheral excitatory inputs onto SG neurons. Together, these results suggest potential cellular and molecular mechanisms that may contribute to intrathecal MrgC agonist-induced analgesia. Because MrgC shares substantial genetic homogeneity with human MrgX1, our findings may suggest a rationale for developing intrathecally delivered MrgX1 receptor agonists to treat pathological pain in humans and provide critical insight regarding potential mechanisms that may underlie its analgesic effects.

Keywords: MrgC, calcium channel, dorsal root ganglion, nerve injury, pain

1. Introduction

Neuronal calcium transport through high-voltage-activated (HVA) calcium channels (N-, P/Q-, L-, and R-type) plays a vital role in excitatory synaptic transmission [1, 26]. In dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, N-type channels (Cav2.2) are essential for cellular signaling and are key participants in peripheral sensitization that leads to exaggerated pain [5, 35, 39]. Indeed, the important pain-inhibitory mechanisms of primary analgesic and adjuvant drugs (e.g., muopioids, gabapentin, ziconotide) involve inhibition of N-type channels [15, 36, 40, 43]. However, because of structural homology among different calcium channels and a broad expression of Cav2.2 in different neuronal populations in the central nervous system (CNS), systemic and intrathecal (spinal cord) administration of N-type channel blockers (e.g., ziconotide) often cause severe CNS adverse effects [11, 38, 42]. Although morphine may indirectly inhibit N-type channels by activating mu-opioid receptors, it also causes dose-limiting adverse effects (respiratory depression, sedation, cognitive dysfunction) and has perceived risks of addiction because it binds to mu-opioid receptors that are expressed throughout the CNS. Therefore, we sought to identify molecules expressed selectively on small-diameter, presumably nociceptive, primary sensory neurons and indirectly inhibit HVA calcium channels for potential pain-selective treatment. One promising candidate is the subtype C of Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptors (MrgC) [14, 17, 31].

MrgC (mouse MrgC11, rat rMrgC) shares remarkable genetic homogeneity with human MrgX1 [49]. It is expressed specifically in small-diameter primary sensory neurons and functions as a receptor for bovine adrenal medulla peptide (BAM), a proteolytically cleaved product of the proenkephalin A gene [14, 31]. Recent animal studies suggest that MrgC may constitute a novel pain inhibitory mechanism. Intrathecal BAM8-22 inhibited both inflammatory and neuropathic pain manifestations and decreased dorsal horn neuronal excitability in animal models [9, 17, 27]. However, the important cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying MrgC agonism-induced analgesia remain elusive. Intriguingly, BAM8-22 inhibits HVA calcium current (Ica) in DRG neurons that heterologously overexpress MrgX1 [8]. Yet, whether BAM8-22 inhibits HVA Ica through activation of Mrgs has not been tested directly owing to the lack of Mrg-deficient neurons. Importantly, it is not yet known how activation of endogenously expressed MrgC receptors affects HVA Ica in native DRG neurons and synaptic transmission in superficial dorsal horn, an important area for nociceptive transmission and modulation.

It has been challenging to examine cellular function of endogenous MrgC receptors in native DRG neurons because only a subset of neurons express MrgC, and identifying MrgC-bearing neurons for recording can be difficult. Recently, we developed a novel dipeptide MrgC-selective agonist (JHU58) that induces analgesia in several animal models of neuropathic pain [22]. We also generated an MrgC-selective antibody and MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mouse [19, 32], and demonstrated that MrgA3 largely colocalizes with MrgC11 in mouse DRG. Using these new tools, we conducted patch-clamp recordings to test the hypothesis that activation of endogenous MrgC inhibits HVA Ica in DRG neurons and attenuates evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) in substantia gelatinosa (SG, lamina II) neurons in wild-type mice, but not Mrg knockout mice after nerve injury. We further identified that JHU58 selectively and dose-dependently inhibits N-type HVA calcium channels, but not other channel subtypes, in native mouse DRG neurons.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and surgery

2.1.1. Animals

All procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University and University of Maryland Animal Care and Use Committees as consistent with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Use of Experimental Animals. Animals received food and water ad libitum and were housed on a 12-hour day–night cycle in isolator cages (maximum of 5 mice/cage).

Mrg-cluster gene knockout (Mrg KO) mice

Chimeric Mrg KO mice were produced by blastocyst injection of positive embryonic stem cells [32]. The KO mice were generated by mating chimeric mice to C57BL/6 mice. The progeny were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for at least five generations. Mrg KO mice have a deletion of 845 kb in chromosome 7, which contains 12 intact Mrg genes, including MrgC11 [17, 32].

MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice

A mouse BAC clone (RP23-311C15) containing the entire MrgA3 gene was purchased from the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute. The BAC clone was modified by using homologous recombination in bacteria to generate the MrgA3 GFP-Cre transgenic line [19]. By crossing MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice for at least five generations with Mrg KO mice, we also made an MrgA3-eGFP-Mrg KO mouse line.

2.1.2. L5 spinal nerve ligation (SNL) in mice

Male C57BL/6 mice (3–4 weeks old) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. The left L5 spinal nerve was exposed and ligated with a 9-0 silk suture and cut distally [22, 37]. The muscle layer was closed with 6-0 chromic gut suture and the skin closed with metal clips. In a sham-operated control group, the surgical procedure was identical to that described above, except that the transverse process of the vertebra was not removed, to prevent possible irritation or damage to the spinal nerve, and the spinal nerve was not ligated or cut.

2.2. Molecular biology

2.2.1. Culture of dissociated DRG neurons

Acutely dissociated DRG neurons from adult mice (4 weeks old) were collected in cold DH10 (90% DMEM/F-12, 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and treated with enzyme solution (5 mg/ml dispase, 1 mg/ml collagenase Type I in HPBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+, Invitrogen) at 37°C for 30 minutes [19, 32]. After trituration and centrifugation, cells were resuspended in DH10, plated on glass coverslips coated with poly-D-lysine and laminin, and cultured in an incubator (95% O2 and 5% CO2) at 37°C for 24 hours with nerve growth factor (25 ng/ml) and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (50 ng/ml). Mrg-mutant DRG neurons were electroporated with Mrg expression constructs by using the Mouse Neuron Nucleofector Kit (Amaxa Biosystems, Anaheim, CA).

2.2.2. Calcium imaging

Neurons were loaded with Fura 2-acetomethoxyl ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature [32]. After being washed, cells were imaged at 340 and 380 nm excitation for detection of intracellular free calcium.

2.2.3. Immunofluorescence

The animals were deeply anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and perfused intracardially with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4, 4°C) followed by fixative (4% formaldehyde and 14% [v/v] saturated picric acid in PBS, 4°C). Lumbar DRG and spinal cord tissues were cryoprotected in 20% sucrose for 24 hours before being serially cut into 25-µm sections and placed onto slides. The slides were pre-incubated in blocking solution (10% normal goat serum, 1 hour) and then incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibody. For DRG staining, the primary antibodies were rabbit antibody to Cav2.2 (681505 Millipore, Billerica, MA; 1:500), chicken antibody to GFP (GFP-1020 Aves Labs, Chicago, IL; 1:1,000), and rabbit polyclonal MrgC antibody (1:500), which was custom-made (Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL). The secondary antibodies were diluted 1:100 in blocking solution and included donkey antibody to rabbit (711-295-152, Rhod Red-X-conjugated, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and goat antibody to chicken (A11039, Alexa 488-conjugated, Molecular Probes). Slides were incubated in secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 hours. The total number of DRG neurons in each section was determined by counting both labeled and unlabeled cell bodies. For spinal cord staining, the primary antibodies were goat antibody to CGRP (1720-9007 AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC; 1:1,000) and rabbit polyclonal MrgC antibody (1:500). The secondary antibodies were diluted 1:100 in blocking solution and included donkey antibody to rabbit (711-295-152, Rhod Red-X-conjugated, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and donkey antibody to goat (705-096-147, FITC-conjugated, Jackson ImmunoResearch). To detect IB4 binding, we incubated sections with Griffonia simplicifolia isolectin GS-IB4-Alexa 488 (1:200; A11001, Molecular Probes). Controls included preabsorption of the primary antibody with the corresponding synthetic peptide or omission of the primary antibody.

2.3. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from DRG neurons

Coverslips plated with DRG neurons were transferred into a perfusion chamber with extracellular solution (ECS, in mM: 145 TEA-Cl, 5 CaCl2, 0.8 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 glucose; pH of 7.39 and osmolarity adjusted to 320 mOsm with sucrose). Neurons with cell body diameters between 22 and 25 µm were recorded in the whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration. The intracellular pipette solution contained (in mM): 135 CsCl, 1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1.5 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 11 EGTA, and 10 HEPES, with pH of 7.3 and osmolarity of 310 mOsm. Electrodes were pulled (Narishige, Model pp-830) from borosilicate glass (WPI, Inc., Sarasota, FL) and had a resistance of 2–4 MΩ. Whole-cell currents were measured with an Axon 700B amplifier and the pCLAMP 9.2 software package (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Current traces were sampled at 10 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz. Low-voltage-activated (LVA) Ica was evoked at −40 mV (20 ms) from a holding potential of −80 mV, and HVA Ica was evoked at 10 mV (20 ms) from a holding potential of −60 mV or −80 mV. We used neurons with HVA Ica (10 mV) / Ica (−40 mV) > 1 for drug testing to limit the potential contamination of small HVA currents from residual LVA currents. All experiments were performed at room temperature (~25°C). The liquid junction potential, cell membrane capacitance, and series resistance were electronically compensated. Leak current was subtracted using the P/-4 protocol. In the presence of 100 µM Cd2+, no voltage-dependent outward currents were evoked. An experimenter blind to genotype and/or drug treatment conditions made the electrophysiology recordings.

2.4. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from spinal cord slices

To prepare spinal cord slices, we first performed a laminectomy in adult (4-week-old) C57BL/6 wild-type mice that were deeply anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Then the lumbosacral segment of the spinal cord was rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold, low-sodium Krebs solution (in mM: 95 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4-H2O, 6 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 25 glucose, 50 sucrose, 1 kynurenic acid) saturated with 95%O2/5% CO2. The tissue was trimmed and mounted on a tissue slicer (Vibratome VT1200, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Transverse slices (400 µm) with attached dorsal roots were prepared and then incubated in preoxygenated low-sodium Krebs solution without kynurenic acid. The slices recovered at 34°C for 40 minutes and then at room temperature for an additional 1 hour before being used for experimental recordings. For electrophysiology recording, slices were stabilized with a grid (ALA Scientific, Farmingdale, NY) and submerged in a low-volume recording chamber (SD Instruments, San Diego, CA) that was perfused with room-temperature Krebs solution (in mM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4-H2O, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 25 glucose) bubbled with a continuous flow of 95% O2/5% CO2. Whole-cell patch-clamp recording of lamina II cells was carried out under oblique illumination with an Olympus fixed-stage microscope system (BX51, Melville, NY). Slices were transferred into a low-volume recording chamber and continuously perfused with room-temperature Krebs solution bubbled with a continuous flow of 95% O2/5% CO2 at a rate of 5 ml/min. Data were acquired with pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices) and a Multiclamp amplifier. Using a puller (P1000, Sutter, Novato, CA), we fabricated thin-walled glass pipettes (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) that had a resistance of 3–6 MΩ and were filled with internal solution (in mM: 120 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 2 Na2-ATP, 0.5 Na2-GTP, and 20 HEPES). To minimize inhibitory postsynaptic current contamination of EPSC recording, we substituted Cl− with F− in the intracellular solution; this substitution preserves network inhibitory synaptic transmission [28]. The cells were voltage clamped at −70 mV. Membrane current signals were sampled at 10 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz. Larger bore pipettes filled with Krebs solution were used for dorsal root stimulation. To evoke EPSCs, we delivered paired-pulse test stimulation to dorsal root consisting of two synaptic volleys (500 µA, 0.1 ms) 400 ms apart at a frequency of 0.05 Hz, followed by a 0.1-ms 5 mV depolarizing pulse (to measure R series and R input). We monitored R series and R input and discarded cells if either of these values changed by more than 20%.

2.5. Drugs

Stock solutions were freshly prepared as instructed by the manufacturer. BAM8-22, JHU58, ω-conotoxin GVIA, nimodipine, ω-agatoxin-TK, bicuculline, strychnine, and tetrodotoxin were all diluted in saline or extracellular solution. JHU58 was synthesized by Johns Hopkins University. Other drugs were purchase from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK).

2.6. Statistical analysis

The methods for statistical comparisons in each study are given in the figure legends. The number of animals used in each study was based on our experience with similar studies and power analysis calculations. We randomized animals to the different treatment groups and blinded the experimenter to drug treatment to reduce selection and observation bias. After the experiments were completed, no data point was excluded. Representative data are from experiments that were replicated biologically at least three times with similar results. STATISTICA 6.0 software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK) was used to conduct all statistical analyses. The Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test was used to compare specific data points. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons. Two-tailed tests were performed, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM; P<0.05 was considered significant in all tests.

3. Results

3.1. BAM8-22 inhibits HVA Ica in DRG neurons from wild-type but not Mrg KO mice

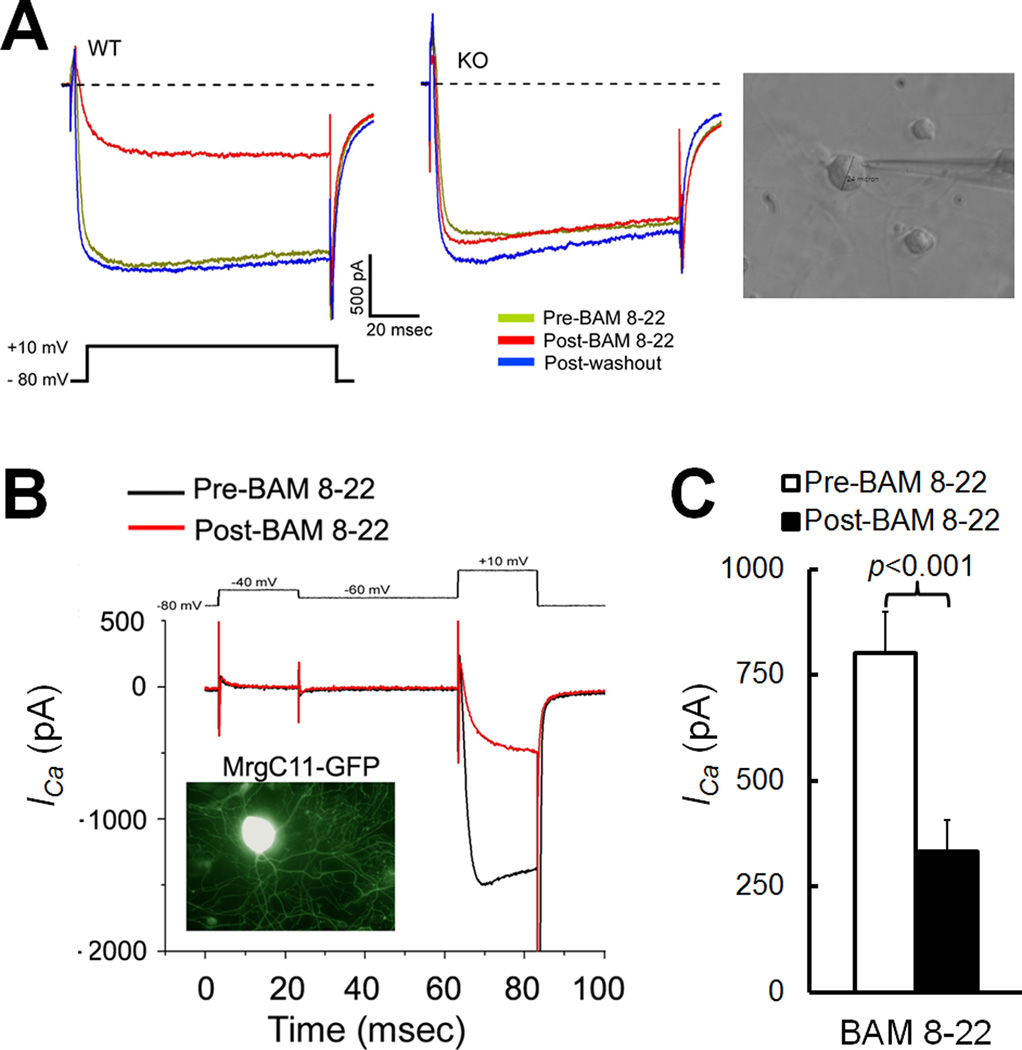

BAM8-22 is a potent, 15-amino acid MrgC agonist that showed analgesic effects in previous animal studies [10, 17, 27]. BAM8-22 also inhibited HVA calcium channels in rat DRG neurons that overexpress exogenous MrgX1 [8]. Therefore, we first used BAM8-22 to examine how activation of endogenous MrgC affects HVA ICa in mouse DRG neurons. BAM8-22 (3 µM) inhibited depolarization-evoked HVA ICa in a small subset of DRG neurons (2/17) from wild-type mice (Fig. 1A), but in no neurons (0/17) from Mrg KO mice in which all nociceptive neuron-expressing Mrgs are deleted [17, 32], suggesting that the drug effect is Mrg-dependent. We further showed that MrgC11 is essential to the ability of BAM8-22 to inhibit HVA ICa in mouse DRG neurons. Each of the 12 Mrg subtype genes deleted in Mrg KO mice has been cloned into a mammalian expression vector, and we electroporated different Mrg expression constructs into dissociated DRG neurons from Mrg KO mice. By fusing GFP to the C-terminal of MrgC11 coding sequences, we can also visualize the transfected cells after 24 h in culture and during electrophysiological recording. Previous studies have shown that GFP does not disturb normal function of the receptors [20, 32]. We found that BAM8-22 (3 µM) significantly inhibited HVA ICa only in MrgC11-transfected cells (n=22; Fig. 1B,C). Non-transfected neurons and neurons transfected with other mouse Mrg subtypes failed to respond (e.g., A1, 3, B5, data not shown). This overlap of BAM8-22 sensitivity with MrgC11 expression suggests that inhibition of HVA ICa by BAM8-22 is mediated by MrgC11 in mice.

Fig. 1. BAM8-22 inhibits high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents in wild-type DRG neurons.

(A) BAM8-22 (3 µM) attenuated HVA Ca2+ currents (ICa) evoked by strong depolarization (−80 to 10 mV, 20 ms) in a subset of wild-type (WT) DRG neurons (2/17), but not in DRG neurons from Mrg-cluster gene knockout (KO) mice (0/17). Right: An image showing the recording from a small-diameter DRG neuron. (B) Traces of small low-voltage-activated ICa (−80 to −40 mV) and large HVA ICa (−60 to 10 mV, 20 ms) evoked by depolarization before and after bath application of BAM8-22 (3 µM). The MrgC11-transfected cell was visualized by coexpressed green fluorescent protein (GFP). (C) BAM8-22 (3 µM) significantly attenuated HVA ICa from pre-drug level in MrgC11-transfected DRG cells (n=22, paired t-test).

3.2. JHU58 dose-dependently inhibits HVA Ica in native mouse DRG neurons

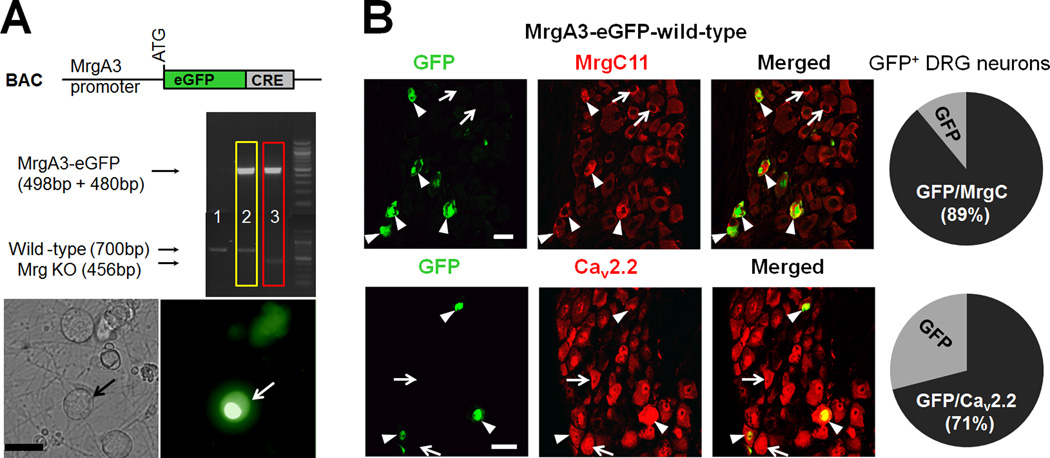

To substantiate that inhibition of HVA ICa is downstream of MrgC activation, we next examined the effects of JHU58, a novel dipeptide MrgC agonist that we recently developed [22]. Because MrgC is expressed only in a subset of rodent DRG neurons [19, 21, 22], examining its function in situ is difficult without randomly sampling a large number of neurons. To circumvent this problem, we used MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice to test the drug’s effect [19]. Most MrgA3 colocalizes with MrgC11 in mouse DRG [32]. Therefore, we chose eGFP+ neurons for electrophysiological recording, as these most likely are MrgC11-expressing [19]. By crossing MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice for at least five generations with Mrg KO mice, we also made MrgA3-eGFP-Mrg KO mice, which do not express MrgA3 or MrgC11, but retain MrgA3 promoter-driven eGFP (Fig. 2A). Thus, we were able to compare the two genotypes by recording similar groups of eGFP+ neurons. Importantly, we confirmed that 89% of MrgA3-eGFP+ neurons co-express MrgC11 (n=44) and 71% of MrgA3-eGFP+ neurons colocalize with Cav2.2 (n=36; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. MrgA3 largely colocalizes with MrgC11 in mouse DRG neurons.

(A) Genotype analysis for MrgA3-eGFP transgene and Mrg genes in Mrg knockout (KO; red) and wild-type (yellow) mice. Bottom: A representative cultured DRG neuron with MrgA3-eGFP marker. (B) Double-immunofluorescence staining shows the colocalization of eGFP with MrgC11 (89%, n=44) and Cav2.2 (71%, n=36) immunoreactivity in lumbar DRGs from MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice. MrgC11+ and Cav2.2+ neurons that colocalized with eGFP are indicated by arrowheads, and those negative for eGFP are indicated by arrows. Scale bar: 20 µm (A,B).

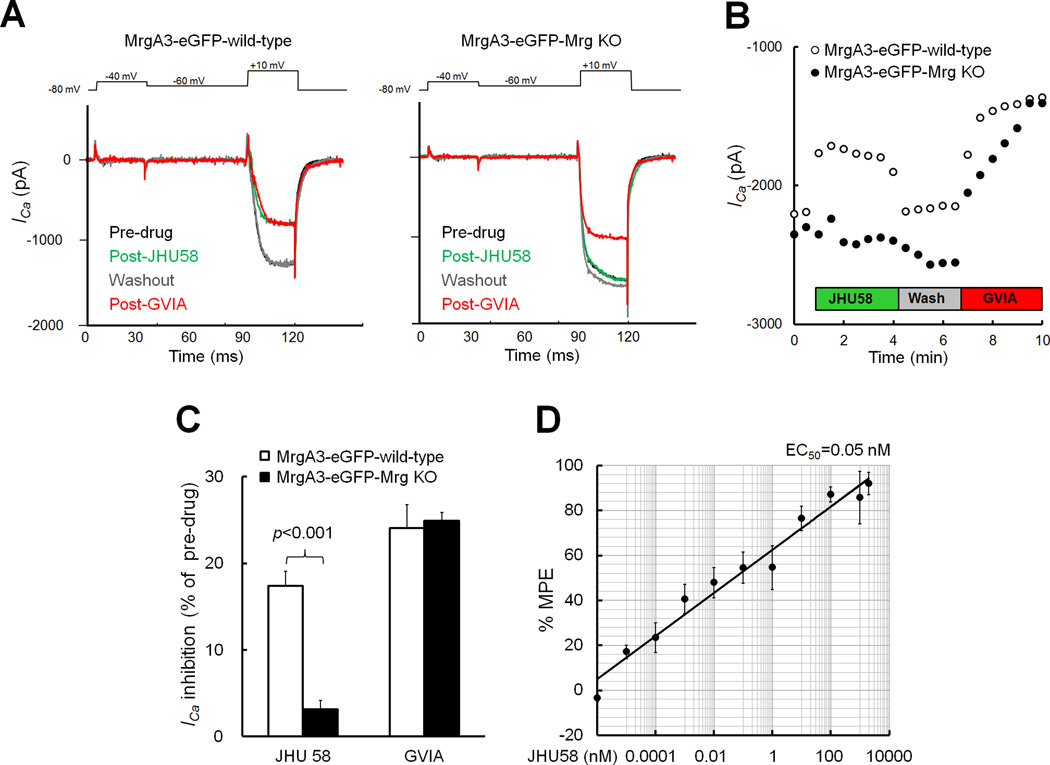

Bath application of JHU58 (1 µM) strongly inhibited HVA ICa in eGFP+ neurons from MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice (n=20, diameter: 25.2 ± 0.4 µm), but not in those from MrgA3-eGFP-Mrg KO mice (n=15, diameter: 24.2 ± 0.5 µm; Fig. 3A–C). JHU58-induced inhibition diminished after washout with extracellular solution, suggesting that the drug action is reversible. Bath application of ω-conotoxin GVIA (1 µM) reduced HVA ICa to a similar degree in eGFP+ neurons from wild-type (n=13) and Mrg KO mice (n=14; Fig. 3C). In MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice, JHU58 inhibition of HVA ICa was dose-dependent (1x10−6 to 2x103 nM, n=5–12/dose, single dose test/neuron; Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Dipeptide MrgC agonist JHU58 inhibits high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents (ICa) in native mouse DRG neurons.

(A) Traces of low-voltage-activated ICa (−80 to −40 mV) and HVA ICa (−60 to 10 mV, 20 ms) evoked by depolarization before and after bath application of JHU58 (1 µM) and later ω-conotoxin GVIA (1 µM) in eGFP+ neurons of MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type and MrgA3-eGFP-Mrg knockout (KO) mice. (B) Examples of current-time curves showing that JHU58 (1 µM) inhibited HVA ICa in MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type but not in MrgA3-eGFP-Mrg KO mice. (C) JHU58 (1 µM) inhibition of HVA ICa was significantly greater in MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type DRG neurons (n=20) than in MrgA3-eGFP-Mrg KO DRG neurons (n=15, unpaired t-test). ω-conotoxin GVIA (1 µM) reduced HVA ICa in eGFP+ neurons regardless of genotype (wild type: n =13, Mrg KO: n=14). (D) JHU58 dose-dependently inhibited HVA ICa in eGFP+ DRG neurons from MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice (n=5–12/dose). Percent maximum possible effect (%MPE) = (ICa inhibition post-JHU58)/(mean ICa inhibition post-GVIA) x100. Mean ICa inhibition post-GVIA (1 µM) = 28.6 ± 1.6% of pre-drug (n=15).

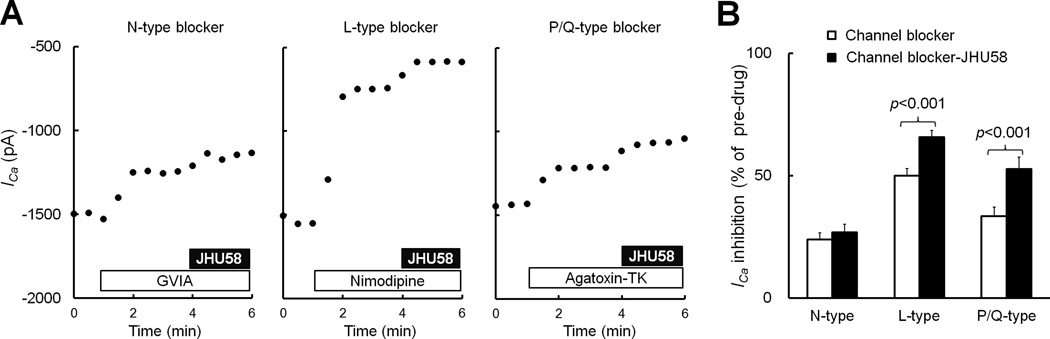

3.3. JHU58 selectively inhibits N-type calcium channels in mouse DRG neurons

Next we determined which subtype of HVA channel is modulated by JHU58. After an initial JHU58 (100 nM) test in eGFP+ neurons from MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice, we treated neurons with antagonist to N-type (ω-conotoxin GVIA, 1 µM, n=13), L-type (nimodipine, 2 µM, n=17), or P/Q-type (ω-agatoxin-TK, 0.25 µM, n=16) channels. We examined the effects of each channel blocker on HVA ICa and then treated the same neurons with JHU58 (100 nM) without washing out the previous blocker (Fig. 4A). Only ω-conotoxin GVIA completely precluded JHU58 inhibition of HVA ICa (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest that JHU58 selectively inhibits N-type channels in native mouse DRG neurons. Accordingly, we normalized JHU58-induced ICa inhibition to that of GVIA (28.6 ±1.6%) to establish the dose-response function (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 4. N-type calcium channel blocker precludes JHU58-induced inhibition of high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents (ICa).

(A) The eGFP+ neurons of MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice were incubated with blockers of N-type (GVIA, 1 µM), L-type (nimodipine, 2 µM), or P/Q-type (ω-agatoxin-TK, 0.25 µM) channels; the same neurons were then tested with JHU58 (100 nM) without washing out the blocker. (B) Blocking the N-type channel (n=13), but not L-type (n=17) or P/Q-type (n=16), precluded JHU58-induced inhibition of HVA ICa in eGFP+ wild-type DRG neurons (paired t-test).

3.4. JHU58 inhibits the evoked synaptic responses in superficial dorsal horn neurons in mice

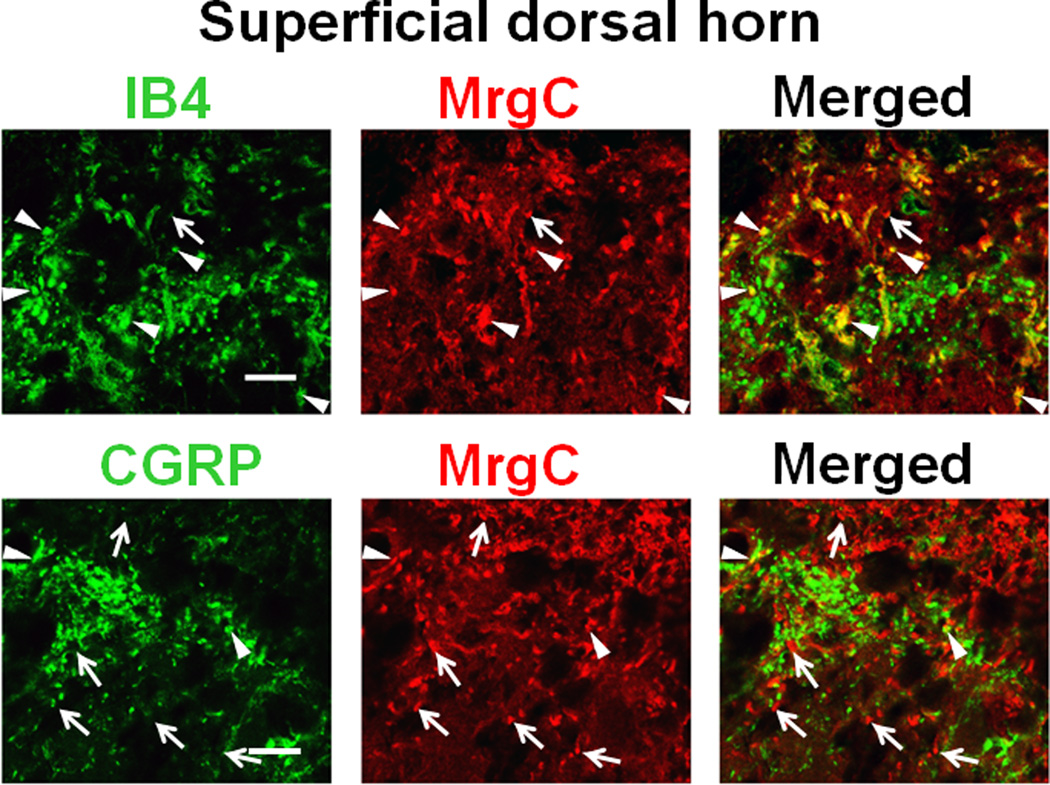

MrgC immunoreactivity (+) has been detected in both non-peptidergic (lectin IB4+) and peptidergic (CGRP+) DRG neurons in wild-type mice and rats [21]. In line with previous findings, we observed colocalization of MrgC with IB4 and CGRP immunoreactivity in the superficial dorsal horn of wild-type mice (Fig. 5). Because the MrgC11 gene is found only in peripheral afferent sensory neurons in mouse [14, 32], this finding suggests that MrgC11 is present at central terminals of subsets of mouse DRG neurons. Activation of HVA calcium channels at central terminals of primary sensory fibers is important to neurotransmitter release [3, 6]. Because the central projections of MrgC-bearing C-fibers terminate in superficial dorsal horn (e.g., lamina II), [19, 21] and MrgC agonists (e.g., JHU58) inhibit HVA ICa in mouse DRG neurons, we next examined whether activation of endogenous MrgC11 receptors attenuates excitatory synaptic transmission in superficial dorsal horn, an important site for nociceptive transmission and modulation.

Fig. 5. Detection of MrgC11 immunoreactivity in superficial dorsal horn in mice.

(A) The high-power views of confocal images of double-immunofluorescence–stained spinal cord sections show colocalization of MrgC11 immunoreactivity (+) with IB4 and CGRP in superficial dorsal horn from wild-type mice. MrgC11+ terminals that coexpressed other molecules are indicated by arrowheads, and MrgC11+ terminals negative for other molecules are indicated by arrows. Scale bar: 20 µm.

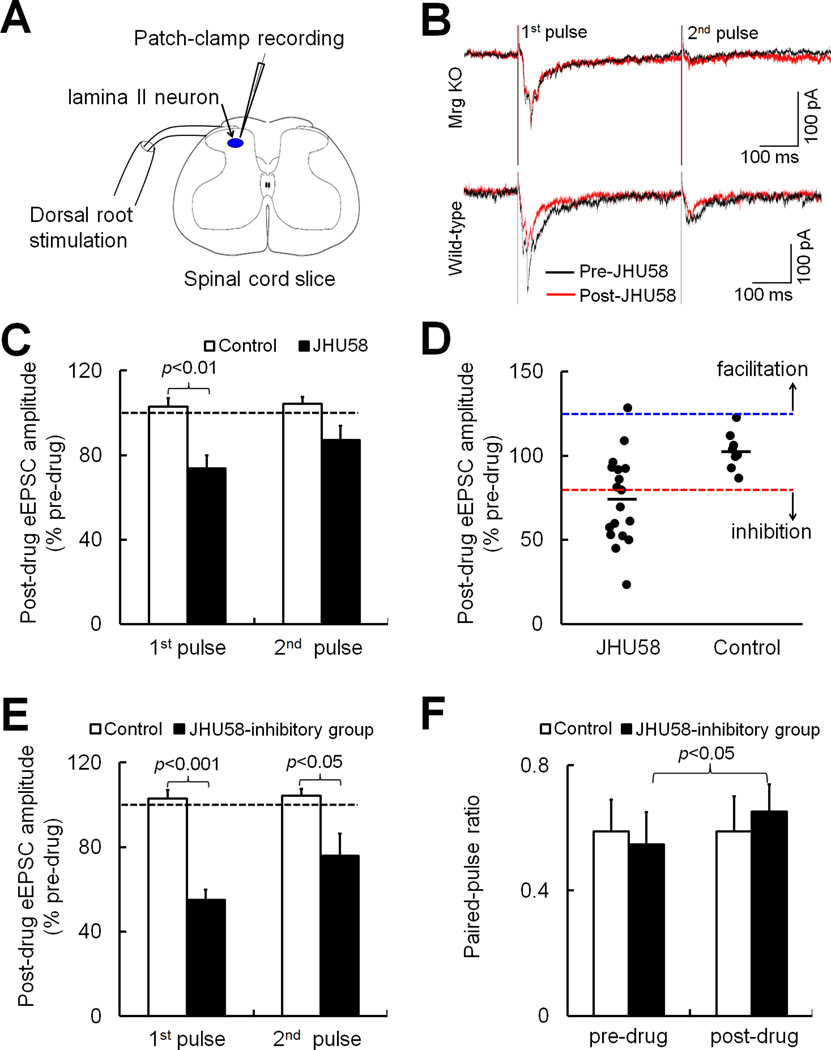

In lumbar spinal cord slices (L4–5 segments) from adult mice (Fig. 6A), we recorded eEPSCs from SG (lamina II) neurons after high-intensity paired-pulse stimulation (500 µA, 0.1 ms, 400 ms apart, 3 tests/min) was applied at the dorsal root. This type of stimulation activates high-threshold afferent fibers (C-fibers). We used paired-pulse stimulation to calculate the paired-pulse ratio (PPR; 2nd eEPSC amplitude / 1st eEPSC amplitude). The change in PPR is used to assess whether the inhibition of postsynaptic response by a drug may involve a decrease in presynaptic release of excitatory neurotransmitters [23, 48]. The peak amplitudes of C-fiber-mediated eEPSCs from 0–5 min after bath application of JHU58 or vehicle (control) were averaged and then normalized to the respective baseline values (0–5 min pre-drug). Due to potential multi-segmental projections of the central terminals of C-fiber afferents, we cannot clearly distinguish the central termini of the injured versus the uninjured DRG neurons at each spinal level. Accordingly, we did the primary analysis on the combined eEPSC data from both L4 and L5 segments. In wild-type mice at 1–2 weeks after an L5 SNL, JHU58 treatment (5 µM, n=18) significantly reduced the eEPSC amplitude to the 1st pulse to 73.7 ± 6.1% of pre-drug level (Fig. 6B,C), but vehicle had no effect (102.9 ± 3.9% of pre-drug, n=9). Importantly, JHU58 (5 µM, n=12) did not inhibit eEPSC in Mrg KO mice that had also undergone L5 SNL (Fig. 6B). The eEPSC amplitudes to the 1st and 2nd pulse after JHU58 application, respectively, were 105.2 ± 7.2% and 96.5 ± 6.8% of pre-drug baseline. Compared to pre-drug value (0.52 ± 0.07), the PPR did not change significantly in Mrg KO mice after JHU58 (0.51±0.06, 99 ± 7.6% of pre-drug). We also conducted secondary analysis in wild-type SNL mice: JHU58 reduced eEPSC amplitude in SG neurons from the injured L5 segment (79.9 ± 8.5% of pre-drug, n=9) and from the ipsilateral, uninjured L4 segment (66.1 ± 8.6% of pre-drug, n=9). The trend was for the reduction to be greater in the uninjured L4 segment, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Fig. 6. JHU58 inhibits the evoked synaptic responses in substantia gelatinosa neurons.

(A) Schematic shows patch-clamp recording of a substantia gelatinosa (SG, lamina II) neuron during dorsal root stimulation in a spinal cord slice. (B) Representative traces of evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) in response to high-intensity, paired-pulse stimulation (500 µA, 0.1 ms, 400 ms interval) before (black) and 5 min after (red) bath application of JHU58 (5 µM) in Mrg knockout (KO) and wild-type mice that had undergone L5 SNL. (C) In wild-type mice at 1–2 weeks after spinal nerve injury, JHU58 significantly depressed the amplitude of the 1st eEPSC to paired-pulse stimulation in SG neurons (n=18), compared to that produced in the presence of vehicle control (n=9, unpaired t-test). (D) We plotted post-drug 1st eEPSC amplitude of each cell for different groups. Inhibitory cells were defined as neurons that had a post-drug 1st eEPSC amplitude that was <80.7% of pre-drug level (below red dashed line), which is more than two SD less than the mean of the control group (102.9 ± 11.1%, mean ± SD, n=9). The facilitatory cells were defined as neurons that had a post-drug 1st eEPSC amplitude >125.2% of pre-drug level (above blue dashed line). Black bar: mean eEPSC amplitude. (E) In the inhibitory group (n=10), the amplitudes of both 1st and 2nd eEPSCs were significantly lower after JHU58 treatment than after vehicle treatment (n=9, unpaired t-test). (F) In the inhibitory group, JHU58, but not vehicle, significantly increased the paired-pulse ratio (2nd eEPSC/1st eEPSC) from pre-drug level (paired t-test).

In both L4 and L5 segments of wild-type mice, it was evident that JHU58 treatment decreased eEPSC in some SG neurons and not in others. Therefore, we conducted exploratory analysis to separate SG neurons that showed different responses to JHU58. We defined neurons with post-drug 1st eEPSC amplitude < 80.7% of pre-drug level, a value more than two SD (11.1%) less than the mean of the saline control group (102.9%, n=9), as inhibitory-response cells (i.e., inhibitory group). Those with a value >125.2% were defined as facilitatory-response cells. Based on these criteria, JHU58 inhibited eEPSCs in 55.6% of SG neurons (10 out of 18 from both segments) in SNL mice (Fig. 6D). Vehicle did not have a significant effect in any of the neurons sampled (n=9 from both segments). In inhibitory-response cells (n=10), JHU58 significantly decreased the amplitudes of both 1st and 2nd eEPSCs compared to those of vehicle-treated cells (n=9; Fig 6E). The amplitude of the 2nd eEPSC was typically smaller than that of the 1st eEPSC. Under pre-drug conditions, the PPR was 0.55 ± 0.11 in the JHU-treated group and 0.58 ± 0.10 in the vehicle-treated group. The PPR was significantly increased to 0.65 ± 0.09 (147 ± 23% of pre-drug) after JHU58 but was largely unchanged after vehicle treatment (0.59 ± 0.11, 104 ± 10% of pre-drug; Fig. 6F).

4. Discussion

Increasing evidence suggests that MrgC agonists act as pain inhibitors when delivered intrathecally [9, 17, 22, 27]. Intrathecal JHU58 attenuated both mechanical and heat hypersensitivity in rats after nerve injury. Additionally, Mrg gene cluster deletion, MrgC siRNA, and an MrgC-selective antagonist each eliminate JHU58-induced analgesia, suggesting that MrgC is the major receptor for JHU58 in vivo [22]. However, cellular functions of MrgC remain largely unknown, leaving open the question of how MrgC agonists induce analgesia. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that two different MrgC agonists (BAM8-22 and JHU58) each inhibit HVA Ica in native mouse DRG neurons. We further identified that MrgC agonism may selectively inhibit N-type channels in DRG neurons. Finally, we provide novel evidence that activation of MrgC receptors decreases eEPSC in SG neurons at the superficial dorsal horn of wild-type mice, but not Mrg KO mice, after nerve injury.

Peripheral nociceptive input relies on small-diameter DRG neurons, and hyperexcitability of these neurons may contribute to persistent pain. HVA calcium channels are important to the transmission of nociceptive stimuli in DRG neurons, and are important drug targets for managing chronic pain [3, 29, 41]. Our findings suggest that HVA calcium channel inhibition is an important downstream event after MrgC receptor activation that may contribute to pain inhibition. Calcium imaging studies have shown that MrgC is the rodent receptor for BAM8-22 and JHU58 [22, 32]. Here, both agonists inhibited HVA ICa in native mouse DRG neurons. Notably, transfecting MrgC11, but not other rodent Mrgs, into Mrg mutant mouse DRG neurons restored BAM8-22 responsiveness, as measured by its ability to attenuate HVA ICa. The loss-of-function phenotype in Mrg mutant neurons and the gain-of-function outcome in these neurons after rescue expression of MrgC11 provide complementary evidence that MrgC11 is essential to BAM8-22–induced inhibition of HVA ICa. Further, we used an innovative BAC transgenic mouse (MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice) that allowed us to prospectively identify the DRG neuron subset that expresses MrgC11 receptor. We found that JHU58 inhibited HVA ICa in eGFP+ DRG neurons of MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice (which co-express MrgC11) but not in those of MrgA3-eGFP-Mrg KO mice. Thus, inhibition of HVA Ica in mouse DRG neurons by JHU58 is MrgC11-dependent.

Perhaps even more important, our study suggests that MrgC agonist-induced inhibition of HVA Ica can be prevented by pretreatment with a blocker of N-type, but not L- or P/Q-type, channels in native mouse DRG neurons. We interpret our inability to detect additional ICa inhibition beyond that produced by ω-conotoxin GVIA to mean that inhibition of N-type channels is the primary mechanism for MrgC agonist-induced inhibition of HVA Ica. The N-type channel, whose expression is increased in chronic pain conditions [34], is essential for sustained neuronal firing and enhanced neurotransmitter release from central terminals of primary sensory neurons that contribute to persistent pain [4, 12, 35]. Inhibition of N-type channels, such as by morphine, is a prime mechanism for inhibiting neurotransmitter release and spinal pain transmission [3, 5, 6, 26]. Specific radioligand binding assays and our immunohistochemical studies have suggested that the MrgC receptor may be transported from the cell body to central terminals [16, 18, 19, 21]. Accordingly, if JHU58 inhibits HVA Ica on central terminals of MrgC11-bearing DRG neurons as on the cell body, it may attenuate excitatory neurotransmission in superficial dorsal horn neurons that receive input from these cells. Our finding that bath application of JHU58 to spinal cord slices inhibits eEPSCs in SG neurons from wild-type, but not Mrg KO, mice after nerve injury provides an important piece of information to support this notion.

Although MrgC is expressed in a subset (14–15%) of rodent DRG neurons [21], central projections of small-diameter DRG neurons may have collateral branches and arborize (terminal branching) extensively in superficial dorsal horn, enabling contact with multiple postsynaptic neurons. Accordingly, over 50% of SG neurons from SNL wild-type mice responded to JHU58 and showed decreased eEPSC. JHU58 also increased PPR in these SG neurons, suggesting that the inhibition of eEPSC may involve a decrease in excitatory neurotransmitter release from central terminals of primary sensory neurons [23, 48]. Importantly, the same JHU58 treatment did not inhibit eEPSC in Mrg KO mice, suggesting that the drug action is Mrg-dependent. Thus, intrathecal administration of MrgC agonists may inhibit evoked pain responses to peripheral stimuli by attenuating stimulation-induced primary excitatory inputs onto postsynaptic dorsal horn neurons. This notion is in line with our recent finding that JHU58 attenuates the frequency, but not amplitude, of spontaneous miniature EPSCs in SG neurons of nerve-injured mice [22]. Together, these findings point to a presynaptic mechanism (i.e., inhibition of peripheral inputs at afferent central terminals) that at least partially contributes to pain inhibition from intrathecal MrgC agonists.

Neurochemical changes after nerve injury may differ in injured and uninjured DRG neurons. MrgC expression was upregulated in uninjured L4 DRGs, but downregulated in L5 DRGs, after an L5 SNL in rats [21]. Although subgroups of SG neurons from both L4 and L5 segments responded to JHU58 in wild-type mice that underwent L5 SNL, future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to determine if MrgC agonist induces a greater inhibition of eEPSC in SG neurons at the L4 segment than at the injured L5 segment. Such a difference could potentially be due to divergent changes in MrgC and N-type channel expression/function in the two segments.

As yet, the major intracellular signaling cascade underlying JHU58 inhibition of HVA ICa in native DRG neurons remains unclear. Activation of heterologously expressed MrgX1 in rat DRG neurons was suggested to inhibit HVA ICa through pertussis toxin-sensitive mechanisms, indicating involvement of the Gi pathway [8]. However, compared to endogenous MrgC in native DRG neurons, it is unclear whether overexpression of exogenous MrgX1 in rat DRG neurons using recombinant adenoviruses might alter MrgC ligand binding, activation of different Gα proteins, and couplings to downstream targets. N-type channels can be modulated by different G-protein-dependent pathways [13, 24, 25]. Because MrgC can couple with both Gαq/11 and Gαi pathways [8, 20], a future study is needed to determine which G-protein pathway is necessary for the inhibition of N-type channels by MrgC in native DRG neurons. Pretreatment with selective blockers of Gαi, Gαq/11, Gαs, and Gβγ can be used to determine which reduces the inhibition of HVA ICa by MrgC agonists in eGFP+ neurons of MrgA3-eGFP-wild-type mice. In addition, MrgC inhibition of N-type channels may also occur through voltage-dependent pathways. In a future study, we will examine whether inhibition of HVA ICa by MrgC agonist can be partially reversed by a strong depolarizing prepulse.

In contrast to the analgesic effects from central MrgC agonism, we are aware that intracutaneous injection of BAM8-22 into hairy skin induces itch [32, 44]. The different outcomes from the same ligand may relate in part to local drug concentration. Inducing an itch response usually requires high local drug concentrations in skin (e.g., BAM8-22 > 1 mM). When the drug is injected locally, little diffusion occurs, so the concentration likely remains high enough to excite nerve terminals that induce itch. Although it remains to be confirmed by pharmacokinetic measurements, it is possible that small volumes of drug (e.g., 10 µl, dissolved in saline) are quickly diluted by the cerebrospinal fluid after intrathecal infusion. Furthermore, intrathecal MrgC agonists induce analgesia at lower doses without signs of irritation (e.g., BAM8-22: 0.5 mM, JHU58: 0.05 mM, 10 µl) [17, 22]. Intriguingly, JHU58 also inhibited HVA ICa at a concentration (0.1 nM) much lower than that needed to induce calcium transients (>3 µM) in DRG neurons. Some G-protein-coupled receptor ligands (e.g., serotonin, capsaicin) exert different effects on pain and other sensations when applied at different locations [7, 30]. Such differences in effect may be caused by differential distribution and compartmentalization of the receptor and by coupling of different downstream targets at peripheral and central terminals [12, 33, 46].

The precise mechanisms for the analgesic effect of MrgC agonism in vivo remain largely unclear and are probably multiple. Prialt/ziconotide, a drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration, blocks N-type channels and is highly efficacious for treating pain when it is administered intrathecally [2, 42, 45]. However, it causes severe neurological side effects because it blocks N-type channels broadly in different neuronal populations in the CNS [38, 42]. Because of the highly specific expression of its targets in the peripheral nervous system [14, 31, 47], MrgX1 agonist may selectively inhibit N-type channels on peripheral sensory neurons and provide an important advance for the treatment of pain without CNS neurological side effects.

In summary, our study suggests novel cellular mechanisms for MrgC-mediated pain inhibition and reveals that the N-type calcium channel is an important downstream molecular target of MrgC activation in native mouse DRG neurons. Although the function of human MrgX1 may not be fully inferred from studying rodent MrgC receptors, MrgC shares substantial homogeneity with MrgX1 [14, 31], and BAM8-22 strongly inhibited HVA ICa in Mrg mutant DRG neurons transfected with MrgX1 (unpublished data). Our findings may suggest a rationale for developing an intrathecally delivered MrgX1 receptor agonist to treat pathological pain in humans and provide critical insight regarding potential mechanisms that may underlie its analgesic effects.

This study suggests that MrgC agonist inhibits N-type calcium channels in native small-diameter primary sensory neurons and attenuates evoked synaptic responses in substantia gelatinosa neurons.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Claire F. Levine, MS (scientific editor, Department of Anesthesiology/CCM, Johns Hopkins University), for editing the manuscript and Yixun Geng and Alene Carteret for mouse genotyping and maintenance.

Funding sources: This study was supported by grants from the NIH: NS70814 (Y.G.), NS54791 (X.D.), NS26363 (S.N.R.), DE18573 (F.W.); the Johns Hopkins Blaustein Pain Research Fund (Y.G.); and Brain Science Institute Awards (Y.G., X.D.). X.D. is an Early Career Scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

None of the authors has a commercial interest in the material presented in this paper. There are no other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest in the current study.

Author contributions

Z.L., S-Q.H. and Q.X. performed most of the experiments and were involved in writing a draft manuscript. Y.F., V.T., Q.L., Z.T., H.L., X.G., and Y-X.C. also conducted some of the electrophysiology, molecular, and behavioral experiments. T.T., N.H., and B.S. developed and synthesized the JHU compounds. Y.W., F.W., and S.N.R. were involved in experimental design and data analysis. Y.G. and X.D. designed and directed the project and wrote the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Abernethy DR, Schwartz JB. Calcium-antagonist drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1447–1457. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911043411907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alicino I, Giglio M, Manca F, Bruno F, Puntillo F. Intrathecal combination of ziconotide and morphine for refractory cancer pain: a rapidly acting and effective choice. Pain. 2012;153:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altier C, Zamponi GW. Targeting Ca2+ channels to treat pain: T-type versus N-type. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braunwald E. Mechanism of action of calcium-channel-blocking agents. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1618–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212233072605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brittain JM, Duarte DB, Wilson SM, Zhu W, Ballard C, Johnson PL, Liu N, Xiong W, Ripsch MS, Wang Y, Fehrenbacher JC, Fitz SD, Khanna M, Park CK, Schmutzler BS, Cheon BM, Due MR, Brustovetsky T, Ashpole NM, Hudmon A, Meroueh SO, Hingtgen CM, Brustovetsky N, Ji RR, Hurley JH, Jin X, Shekhar A, Xu XM, Oxford GS, Vasko MR, White FA, Khanna R. Suppression of inflammatory and neuropathic pain by uncoupling CRMP-2 from the presynaptic Ca(2)(+) channel complex. Nat Med. 2011;17:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nm.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callaghan B, Haythornthwaite A, Berecki G, Clark RJ, Craik DJ, Adams DJ. Analgesic alpha-conotoxins Vc1.1 and Rg1A inhibit N-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons via GABAB receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10943–10951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3594-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Ikeda SR. Modulation of ion channels and synaptic transmission by a human sensory neuron-specific G-protein-coupled receptor, SNSR4/mrgX1, heterologously expressed in cultured rat neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5044–5053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0990-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T, Cai Q, Hong Y. Intrathecal sensory neuron-specific receptor agonists bovine adrenal medulla 8-22 and (Tyr6)-gamma2-MSH-6–12 inhibit formalin-evoked nociception and neuronal Fos-like immunoreactivity in the spinal cord of the rat. Neuroscience. 2006;141:965–975. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen T, Hu Z, Quirion R, Hong Y. Modulation of NMDA receptors by intrathecal administration of the sensory neuron-specific receptor agonist BAM8-22. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christo PJ, Grabow TS, Raja SN. Opioid effectiveness, addiction, and depression in chronic pain. Adv Psychosom Med. 2004;25:123–137. doi: 10.1159/000079062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delmas P, Abogadie FC, Buckley NJ, Brown DA. Calcium channel gating and modulation by transmitters depend on cellular compartmentalization. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:670–678. doi: 10.1038/76621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolphin AC, Scott RH. Modulation of Ca2+-channel currents in sensory neurons by pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;560:387–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb24117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong X, Han S, Zylka MJ, Simon MI, Anderson DJ. A diverse family of GPCRs expressed in specific subsets of nociceptive sensory neurons. Cell. 2001;106:619–632. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garber K. Peptide leads new class of chronic pain drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:399. doi: 10.1038/nbt0405-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grazzini E, Puma C, Roy MO, Yu XH, O'Donnell D, Schmidt R, Dautrey S, Ducharme J, Perkins M, Panetta R, Laird JM, Ahmad S, Lembo PM. Sensory neuron-specific receptor activation elicits central and peripheral nociceptive effects in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7175–7180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307185101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan Y, Liu Q, Tang Z, Raja SN, Anderson DJ, Dong X. Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptors inhibit pathological pain in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15933–15938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011221107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hager UA, Hein A, Lennerz JK, Zimmermann K, Neuhuber WL, Reeh PW. Morphological characterization of rat Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor C and functional analysis of agonists. Neuroscience. 2008;151:242–254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han L, Ma C, Liu Q, Weng HJ, Cui Y, Tang Z, Kim Y, Nie H, Qu L, Patel KN, Li Z, McNeil B, He S, Guan Y, Xiao B, LaMotte RH, Dong X. A subpopulation of nociceptors specifically linked to itch. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:174–182. doi: 10.1038/nn.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han SK, Dong X, Hwang JI, Zylka MJ, Anderson DJ, Simon MI. Orphan G protein-coupled receptors MrgA1 and MrgC11 are distinctively activated by RF-amide-related peptides through the Galpha q/11 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14740–14745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192565799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He SQ, Han L, Li Z, Xu Q, Tiwari V, Yang F, Guan X, Wang Y, Raja SN, Dong X, Guan Y. Temporal changes in MrgC expression after spinal nerve injury. Neuroscience. 2014;261:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He SQ, Li Z, Chu YX, Han L, Xu Q, Li M, Yang F, Liu Q, Tang Z, Wang Y, Hin N, Tsukamoto T, Slusher B, Tiwari V, Shechter R, Wei F, Raja SN, Dong X, Guan Y. MrgC agonism at central terminals of primary sensory neurons inhibits neuropathic pain. Pain. 2014;155:534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinl C, Drdla-Schutting R, Xanthos DN, Sandkuhler J. Distinct mechanisms underlying pronociceptive effects of opioids. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16748–16756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3491-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herlitze S, Garcia DE, Mackie K, Hille B, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature. 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hille B, Beech DJ, Bernheim L, Mathie A, Shapiro MS, Wollmuth LP. Multiple G-protein-coupled pathways inhibit N-type Ca channels of neurons. Life Sci. 1995;56:989–992. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoppa MB, Lana B, Margas W, Dolphin AC, Ryan TA. alpha2delta expression sets presynaptic calcium channel abundance and release probability. Nature. 2012;486:122–125. doi: 10.1038/nature11033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang J, Wang D, Zhou X, Huo Y, Chen T, Hu F, Quirion R, Hong Y. Effect of Mas-related gene (Mrg) receptors on hyperalgesia in rats with CFA-induced inflammation via direct and indirect mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/bph.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato A, Punnakkal P, Pernia-Andrade AJ, von SC, Sharopov S, Nyilas R, Katona I, Zeilhofer HU. Endocannabinoid-dependent plasticity at spinal nociceptor synapses. J Physiol. 2012;590:4717–4733. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.234229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim DS, Yoon CH, Lee SJ, Park SY, Yoo HJ, Cho HJ. Changes in voltage-gated calcium channel alpha(1) gene expression in rat dorsal root ganglia following peripheral nerve injury. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;96:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kusudo K, Ikeda H, Murase K. Depression of presynaptic excitation by the activation of vanilloid receptor 1 in the rat spinal dorsal horn revealed by optical imaging. Mol Pain. 2006;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lembo PM, Grazzini E, Groblewski T, O'Donnell D, Roy MO, Zhang J, Hoffert C, Cao J, Schmidt R, Pelletier M, Labarre M, Gosselin M, Fortin Y, Banville D, Shen SH, Strom P, Payza K, Dray A, Walker P, Ahmad S. Proenkephalin A gene products activate a new family of sensory neuron--specific GPCRs. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:201–209. doi: 10.1038/nn815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Q, Tang Z, Surdenikova L, Kim S, Patel KN, Kim A, Ru F, Guan Y, Weng HJ, Geng Y, Undem BJ, Kollarik M, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ, Dong X. Sensory neuron-specific GPCR Mrgprs are itch receptors mediating chloroquine-induced pruritus. Cell. 2009;139:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Yang FC, Okuda T, Dong X, Zylka MJ, Chen CL, Anderson DJ, Kuner R, Ma Q. Mechanisms of compartmentalized expression of Mrg class G-protein-coupled sensory receptors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:125–132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4472-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo ZD, Calcutt NA, Higuera ES, Valder CR, Song YH, Svensson CI, Myers RR. Injury type-specific calcium channel alpha 2 delta-1 subunit up-regulation in rat neuropathic pain models correlates with antiallodynic effects of gabapentin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:1199–1205. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGivern JG. Targeting N-type and T-type calcium channels for the treatment of pain. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:245–253. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molinski TF, Dalisay DS, Lievens SL, Saludes JP. Drug development from marine natural products. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:69–85. doi: 10.1038/nrd2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park U, Vastani N, Guan Y, Raja SN, Koltzenburg M, Caterina MJ. TRP vanilloid 2 knock-out mice are susceptible to perinatal lethality but display normal thermal and mechanical nociception. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11425–1136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1384-09.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Penn RD, Paice JA. Adverse effects associated with the intrathecal administration of ziconotide. Pain. 2000;85:291–296. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raingo J, Castiglioni AJ, Lipscombe D. Alternative splicing controls G protein-dependent inhibition of N-type calcium channels in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:285–292. doi: 10.1038/nn1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogawski MA, Loscher W. The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of nonepileptic conditions. Nat Med. 2004;10:685–692. doi: 10.1038/nm1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saegusa H, Kurihara T, Zong S, Kazuno A, Matsuda Y, Nonaka T, Han W, Toriyama H, Tanabe T. Suppression of inflammatory and neuropathic pain symptoms in mice lacking the N-type Ca2+ channel. EMBO J. 2001;20:2349–2356. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidtko A, Lotsch J, Freynhagen R, Geisslinger G. Ziconotide for treatment of severe chronic pain. Lancet. 2010;375:1569–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schroeder JE, McCleskey EW. Inhibition of Ca2+ currents by a mu-opioid in a defined subset of rat sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1993;13:867–873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00867.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sikand P, Dong X, LaMotte RH. BAM8-22 peptide produces itch and nociceptive sensations in humans independent of histamine release. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7563–7567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1192-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vitale V, Battelli D, Gasperoni E, Monachese N. Intrathecal therapy with ziconotide: clinical experience and considerations on its use. Minerva Anestesiol. 2008;74:727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson SR, Gerhold KA, Bifolck-Fisher A, Liu Q, Patel KN, Dong X, Bautista DM. TRPA1 is required for histamine-independent, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor-mediated itch. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:595–602. doi: 10.1038/nn.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Taylor N, Xie Y, Ford R, Johnson J, Paulsen JE, Bates B. Cloning and expression of MRG receptors in macaque, mouse, and human. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;133:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zylka MJ, Dong X, Southwell AL, Anderson DJ. Atypical expansion in mice of the sensory neuron-specific Mrg G protein-coupled receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10043–10048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1732949100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]