Abstract

The olfactory system remains plastic throughout life due to continuous neurogenesis of sensory neurons in the nose and inhibitory interneurons in the olfactory bulb. Here, we reveal that transgenic expression of an odorant receptor has non-cell autonomous effects on axons expressing this receptor from the endogenous gene. Perinatal expression of transgenic odorant receptor causes rerouting of like-axons to new glomeruli, while expression after the sensory map is established does not lead to rerouting. Further, chemical ablation of the map after rerouting does not restore the normal map, even when the transgenic receptor is no longer expressed. Our results reveal that glomeruli are designated as targets for sensory neurons expressing specific odorant receptors during a critical period in the formation of the olfactory sensory map.

Critical periods are epochs of increased brain plasticity when neural circuits are especially sensitive to shaping by stimuli. In the olfactory system, enhanced plasticity is not confined to early development; rather, it is maintained throughout adult life (1). This prolonged plasticity is achieved by the continuous generation of the inhibitory granule cells that migrate into the olfactory bulb and integrate into the circuits, and by the generation of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) that incorporate into the circuits throughout life (2, 3). While we know that plasticity is retained in the mature olfactory system, does a critical period exist in the formation of the sensory map in the olfactory bulb?

In mice, each OSN expresses only one of the ~1300 odorant receptor (OR) genes (4–7) from only one allele (8). The OSNs that express the same OR are randomly dispersed within a broad zone in the main olfactory epithelium in the nose (9, 10). In the olfactory bulb, the first olfactory center in the brain, the axons of OSNs expressing the same OR converge on spatially fixed neuropil structures called glomeruli (9–11). Further, ORs actively participate in the axon guidance of OSNs to particular glomeruli (12, 13). In the glomeruli, the axons synapse with the dendrites of mitral and tufted cells, the projection neurons in the bulb. Each projection neuron receives input from a single glomerulus and sends its axon to the olfactory cortex. Thus, an olfactory sensory map is formed in the bulb. In this map, the identity of each odor is encoded by the combination of glomeruli that it activates (3). In contrast to the somatosensory, auditory, and visual maps, neighboring relations between peripheral sensory neurons are not maintained in the olfactory sensory map. Since OSNs continue to integrate into the circuits throughout life, the challenge of axon guidance persists in adulthood (3).

We devised a strategy for ectopic expression of a specific OR, MOR28, in a temporally controlled manner using the tetracycline response element (tetO) to drive its expression. The tetO promoter is activated by the tetracycline-controlled transcription activator tTA, which is inhibited by the antibiotic doxycycline. When doxycycline is removed, expression from the tetO promoter is induced within days (14–16). A similar approach for inducing ectopic expression of ORs was previously used (17–19). Our strategy involved the use of three alleles (Fig. S1A). In the first, designated OMP-IRES-tTA, the olfactory marker protein (OMP) drives expression of tTA in all OSNs (16). In the second, designated tetO::MOR28-IRES-tau-LacZ (TO28), tetO drives the expression of MOR28 and the fusion protein tau-β-galactosidase (β-gal). To distinguish between the OSNs that express MOR28 from its endogenous genomic locus (endogenous MOR28 OSNs) versus OSNs that express MOR28 from the transgene (transgenic MOR28 OSNs), we introduced a third allele, designated MOR28-IRES-GFP. OSNs that express MOR28 from this allele also express green fluorescent protein (GFP) (20). Thus, GFP expression marks OSNs expressing MOR28 from its endogenous locus. Since β-gal and GFP are exogenous to mice, staining for each identifies transgenic or endogenous MOR28 OSNs, respectively (Fig. S1B). This strategy enabled us to induce transgene expression at different developmental points.

We generated two founder lines for the TO28 transgene. In the presence of the OMP-IRES-tTA allele, animals from these lines express the transgene only in a small fraction of OSNs, presumably due to position effect variegation. In one of these lines, designated TO28L, the transgene is expressed in ~1% of OSNs, and in the other, designated TO28H, the transgene is expressed in ~5% of OSNs. In both lines, the transgene is expressed throughout the olfactory epithelium, both within and outside the characteristic MOR28 zone of expression (Fig. 1, A and B, and Fig. S1B).

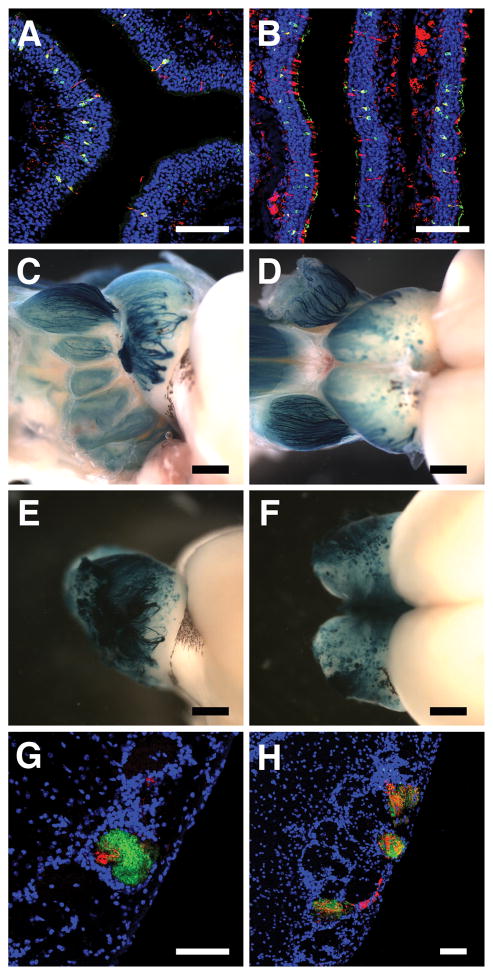

Fig. 1. Ectopic expression of MOR28 results in formation of two types of ectopic glomeruli.

Staining with antibodies against MOR28 (green) and β-gal (red) reveal ectopic expression of MOR28 in the olfactory epithelia from two lines: TO28L expresses MOR28 in ~1% of OSNs (A), and TO28H expresses MOR28 in ~5% of OSNs (B). Lateral and dorsal views of whole-mount preparations from TO28L (C, D) and TO28H (E, F) stained with X-gal to reveal the distribution of ectopic glomeruli. (G, H) Bulb sections from TO28L were stained with antibodies against GFP (green) to reveal endogenous MOR28, and β-gal (red) to reveal transgenic MOR28. In some cases, the abundance of green fibers identifies the wild-type MOR28 glomerulus (G). In others, axons expressing endogenous MOR28 innervate multiple MOR28-rerouted glomeruli (M). Scale bars: for C–F, 1mm; all other images, 100μm.

Normally, MOR28-expressing OSNs converge on two symmetrical pairs of glomeruli per mouse, one medial and one lateral, all located in the posterior-ventral part of the bulb (21, 13, 16, 20). In both transgenic MOR28 lines, visualization of the projection patterns of transgene-expressing OSNs revealed that they converged on multiple glomeruli that were scattered throughout the bulb. The positions and numbers of these glomeruli varied significantly between animals and also between the two bulbs within the same animal (Fig. 1, C to F). We counted the ectopic glomeruli in sectioned bulbs from both lines and observed 46.8±8.33 β-gal-positive glomeruli per animal (n=5) in TO28L and 103.25±13.85 glomeruli per animal (n=4) in TO28H (Fig. S1C).

In animals that express transgenic MOR28, the endogenous MOR28 axons innervated more than the regular four glomeruli. These glomeruli were always co-innervated by transgenic MOR28 fibers, and they were confined to areas within 650 μm of the typical locations of the wild-type glomeruli (Fig. 1, G and H). In some cases, only a few transgenic MOR28 fibers innervated a glomerulus mainly innervated by endogenous MOR28 fibers, likely the wild-type MOR28 glomerulus (Fig. 1G). In other cases, the transgenic MOR28 fibers and the endogenous MOR28 axons innervated multiple glomeruli. However, the mixing between the two neuronal populations was extensive, and we could not determine which of the glomeruli was the wild-type MOR28 glomerulus (Fig. 1H). Since the endogenous MOR28 axons do not express transgenic MOR28 (Fig. S1B), this phenotype is non-cell autonomous and is likely the result of homotypic attraction between the endogenous and transgenic MOR28 fibers (22, 19). We refer to the glomeruli that contain both endogenous and transgenic MOR28 axons as rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli. Roughly the same numbers of rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli are observed in the two TO28 lines: 3.14±0.55 (n=7) in TO28L and 4.8±0.86 (n=5) in TO28H (Fig S1D).

We examined whether rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli could be formed throughout the lifetime of the animal, or whether they could only be formed during a specific developmental period. To determine this, we used doxycycline to silence the tetO promoter in mice capable of TO28 expression (mice bearing both the transgene and the OMP-IRES-tTA driver). Pregnant females were fed doxycycline from conception to allow the embryos to form wild-type glomerular maps. We then removed doxycycline from the diet at P0, P7, or P14 to allow transgene expression. Mice were maintained on a doxycycline-free diet to enable continuous transgene expression and were examined after 15 weeks or 32 weeks without the drug, nearly 3 times the half-life of OSNs (Fig. S2A). Whereas transgenic MOR28 axons formed ectopic glomeruli and also innervated the wild-type MOR28 glomeruli, endogenous MOR28 axons almost never formed rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli (Fig. 2, A to D, Fig. S3A, and Fig. S3, C to F). When doxycycline was removed at P0, or P7 rerouted glomeruli were observed in one mouse out of nine, or one out of seventeen, respectively. Rerouting was never observed (0/9 mice) when doxycycline was removed at P14 (Fig. S3B). We conclude that there is a critical period for the formation of rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli that ends at birth, or shortly thereafter.

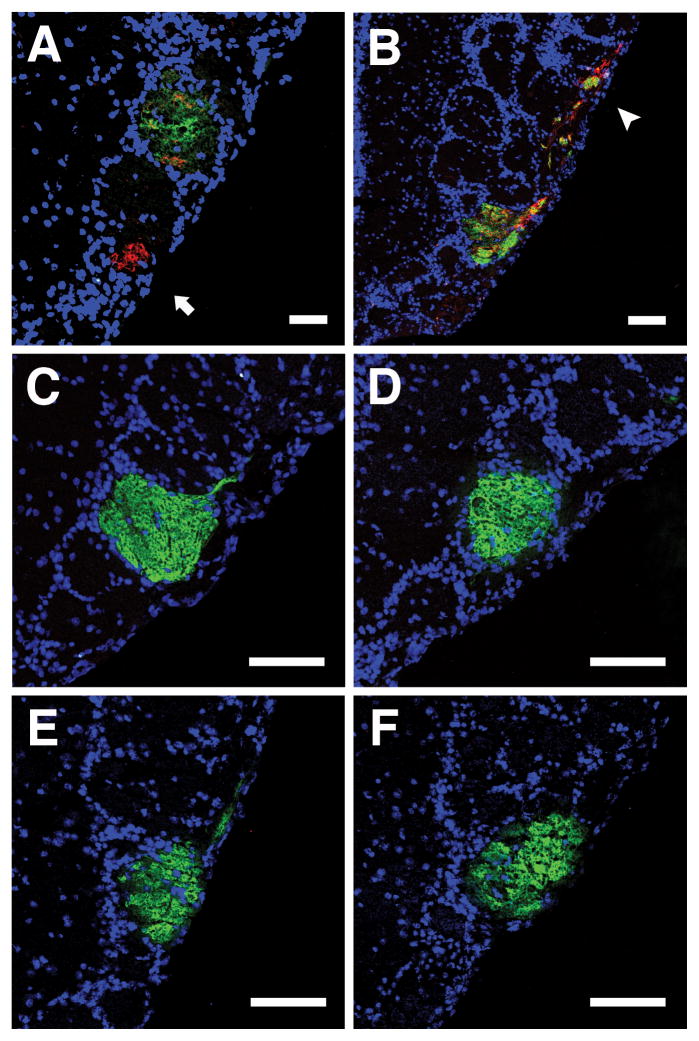

Fig. 2. Axon rerouting only occurs within a critical period.

Bulb sections from TO28L mice were stained for GFP (green) and β-gal (red). Although ectopic glomeruli formed in mice treated with doxycycline from conception to P14 and then raised for 32 weeks without doxycycline, rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli were never observed (n=4). Arrow denotes a nearby ectopic glomerulus without rerouted-MOR28 axons (A). In mice raised without doxycycline (n=7), both rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli (3.14±0.55) and ectopic glomeruli were observed. Arrowhead indicates the edge of a second rerouted glomerulus that is shown in Fig. S2C. (B). Rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli were not observed in control littermates treated with doxycycline until P14 (n=2) (C), or never exposed to doxycycline (n=4) (D). TO28L mice maintained on a doxycycline diet before and after OSN ablation never exhibited rerouted glomeruli (n=2) (E). Mice that expressed TO28L only postnatally did not form rerouted glomeruli even after OSN ablation (n=5) (F). Scale bars 100μm.

Among the many differences between the developing and adult olfactory systems is the fraction of OSNs that are immature with outgrowing axons. In embryos, most OSNs are immature and their axons target the glomeruli within a short period of time. Thus, outgrowing axons do not contact many established axonal tracts. By contrast, at any given time in the adult, only rare OSN axons are actively growing along established tracts made up of mature OSN axons. We therefore tested whether the abundance of immature OSNs with outgrowing axons underlies the critical period for the formation of rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli. Mice capable of TO28 expression were treated with doxycycline beginning at conception to suppress the formation of rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli. As the mice were taken off doxycycline, they were also treated with methimazole, which causes OSN ablation (23). We empirically determined the peak effect of methimazole on MOR28-expressing neurons, and found that at 5 days post injection only 0.2% of these OSNs remain (Fig. S2B). Thus, this paradigm enabled us to examine synchronized regrowth of 99.8% of the axons in the adult. When regrowth occurred in the presence of transgenic MOR28 axons (n=5 mice), ectopic glomeruli were formed, but we still never observed rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli (Fig. 2, E and F, and Fig. S3A). These data indicate that the developmental mechanisms available perinatally, when the olfactory map is established, are not available for regeneration in the adult after olfactory neuron ablation.

We next examined whether continuous transgene expression is required for the maintenance of rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli. Mice expressing the transgene developed until 2 months of age to allow ectopic and rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli to form. These mice were then treated with doxycycline for 21 weeks, or nearly twice the half-life of OSNs, to allow for substantial turnover of MOR28-expressing OSNs (Fig. S4). Although no axon fibers expressing transgenic MOR28 were observed at this point, endogenous MOR28 axons continued to innervate the rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli (Fig. 3, A to C). Thus rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli, once formed, were not dependent on persistent expression of transgenic MOR28.

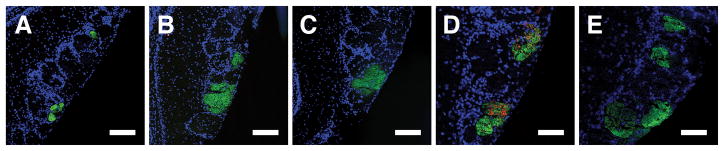

Fig. 3. Rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli are maintained even without continuous transgene expression.

(A–C) TO28L mice and control littermates were raised without doxycycline until P60 and treated with doxycycline for >5 months thereafter. Bulb sections were stained for GFP (green) and β-gal (red). Rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli were observed after 21 weeks (A), and even after 32 weeks (B), on doxycycline, when transgenic MOR28 fibers were no longer present. No rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli were observed in controls after 21 weeks on doxycycline (C). (D, E) TO28L mice were raised without doxycycline until P60, when OSNs were ablated. The mice were analyzed after two months recovery with or without doxycycline. Mice that expressed the transgene before and after OSN ablation exhibited rerouted glomeruli (3.6±0.98, n=5) (D). In mice that expressed the transgene only pre-ablation, transgenic MOR28 fibers were no longer present, but endogenous MOR28 axons still innervated multiple glomeruli (3±1.15, n=3) (E). Scale bars 100μm.

Finally, we examined whether the rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli would still be targeted by newly growing endogenous MOR28 axons after OSN ablation. Mice expressing TO28L were allowed to form ectopic and rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli until 2 months of age. The OSNs were then ablated by methimazole injection, and the mice were treated with doxycycline for 2 months to allow the glomerular map to be restored without expression of transgenic MOR28 (Fig. S4). These mice exhibited as many rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli as mice that were not treated with doxycycline after OSN ablation (Fig. 3, D and E). These results suggest that the previously formed rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli, or the tracts leading to them, are marked as targets for endogenous MOR28 axons.

We have shown that OSNs expressing a particular OR are affected non-cell autonomously by other OSNs that express the same OR. This supports the notion that homotypic attraction exists between OSNs expressing the same OR (22, 19). It is unclear whether these interactions are directly mediated by the axonal OR itself (13), or by any of the cell adhesion molecules implicated in OSN guidance (3). A role for OR-mediated, non-cell autonomous interactions in glomerular formation adds a layer of complexity to the prevailing model that focuses on cell-autonomous mechanisms by which ORs affect guidance (3, 24). Homotypic attraction between OSNs leads to convergence of like-axons on the same glomeruli. This is in contrast to the homotypic repulsion between neurons expressing the same splice form of the adhesion molecule DSCAM1 in Drosophila and self-avoidance between neurites expressing the same type of protocadherin in mammals (25, 26). Should similar non-cell autonomous mechanisms participate in the organization of other circuits, it would pose a challenge for the development of neuronal regeneration therapies.

The confinement of rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli to areas within 650 μm of the typical locations of the wild-type glomeruli and the cap in the number of rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli in the two founder lines suggest that axon rerouting can occur only within a “neighborhood” of glomeruli. This “neighborhood” likely corresponds to the area where the final sorting of axons expressing the same OR into discrete glomeruli occurs (3).

What is the nature of the guidance signal? It is formally possible that the axons of the ~30 endogenous MOR28 OSNs per mouse remaining after methimazole ablation serve as the structural substrate of the memory for the tract to the rerouted-MOR28 glomeruli. However, a model in which the few residual endogenous MOR28 OSNs act as “pioneers” is unlikely in view of the sparse distribution of these neurons. Alternatively, fragments of the axons of the dead neurons could mark the tracts to the glomeruli. In this case, the axons of regenerating OSNs would follow this trail to the correct glomerulus by interacting with these fragments. As another possibility, axons may leave molecular traces in the surrounding extracellular matrix, or may induce expression of specific marks in postsynaptic neurons. Regardless of the precise mechanism, our results show that these marks are put in place only during a developmental critical period. This may ensure the stability of the olfactory sensory map in spite of the continuous regeneration of OSNs throughout life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard Axel, Dr. Eric Morrow and members of the Barnea laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Ryan Y. Korsak and Mustafa Talay for artwork for the figures. This work was supported by NIH grants T32GM007601 (L.T) and 5R01MH086920 (G.B) as well as by funds from the Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences program.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Hensch TK. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:549–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carleton A, Petreanu LT, Lansford R, Alvarez-Buylla A, Lledo PM. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:507–518. doi: 10.1038/nn1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori K, Sakano H. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:467–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-112210-112917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vassar R, Ngai J, Axel R. Cell. 1993;74:309–318. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90422-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ressler KJ, Sullivan SL, Buck LB. Cell. 1993;73:597–609. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90145-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raming K, et al. Nature. 1993;361:353–356. doi: 10.1038/361353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Firestein S. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:124–133. doi: 10.1038/nn800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chess A, Simon I, Cedar H, Axel R. Cell. 1994;78:823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90562-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vassar R, et al. Cell. 1994;79:981–991. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ressler K, Sullivan S, Buck L. Cell. 1994;79:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mombaerts P, et al. Cell. 1996;84:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang F, Nemes A, Mendelsohn M, Axel R. Cell. 1998;93:47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnea G, et al. Science. 2004;304:1468. doi: 10.1126/science.1096146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gossen M, Bujard H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gogos JA, Osborne J, Nemes A, Mendelsohn M, Axel R. Cell. 2000;103:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu CR, et al. Neuron. 2004;42:553–566. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen MQ, Zhou Z, Marks CA, Ryba NJP, Belluscio L. Cell. 2007;131:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleischmann A, et al. Neuron. 2008;60:1068–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen MQ, Marks CA, Belluscio L, Ryba NJP. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9271–9279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1502-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shykind BM, et al. Cell. 2004;117:801–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuboi A, et al. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8409–8418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08409.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vassalli A, Rothman A, Feinstein P, Zapotocky M, Mombaerts P. Neuron. 2002;15:681–696. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brittebo EB. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;76:76–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakashima A, et al. Cell. 2013;154:1314–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefebvre JL, Kostandinov D, Chen WV, Maniatis T, Sanes JR. Nature. 2012;488:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zipursky SL, Grueber WB. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013;36:547–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson MA, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13410–13415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206724109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.