Abstract

PURPOSE

Asymmetric step length is a problem common to many orthopedic and neurologic populations. Herein, we compare step length aftereffects during overground gait following two rehabilitation intervention strategies to combat step length asymmetry: split-belt treadmill (SBT) walking and unilateral stepping.

METHODS

Eighteen healthy young adults (22 ± 3 yrs) first performed ten overground gait trials. Participants then walked for ten minutes under three different treadmill conditions in a randomized order: SBT walking, slow unilateral stepping, and fast unilateral stepping. Immediately following each treadmill condition, participants performed ten overground gait trials. Mean step length asymmetry was calculated across the first five strides of the overground gait trials to assess the storage of aftereffects following each treadmill condition. We also explored the lower extremity kinematics during each treadmill condition to investigate movement patterns that lead to greatest aftereffects.

RESULTS

Significantly higher step length asymmetry was observed in overground gait trials following SBT walking compared to those following slow and fast unilateral stepping, indicating greater aftereffect/carryover of the SBT walking pattern to overground gait. During fast unilateral stepping, increased flexion in the hip, knee, and ankle of the stationary limb was significantly associated with increased step length aftereffects.

CONCLUSION

The aftereffects observed following acute SBT walking were significantly greater than those following unilateral stepping. Both exercises induce aftereffects of similar kinematic patterns, though likely through different mechanisms. In sum, SBT walking induces the greatest aftereffects, though unilateral stepping also induces a change in gait behavior. During unilateral stepping, the largest aftereffects occur when the walker does not simply fully extend the stationary limb and allow the treadmill to passively move the stepping limb during stance.

Keywords: Step length, gait, adaptation, learning, asymmetry, rehabilitation

Introduction

Gait adaptation during split-belt treadmill (SBT) walking has recently been studied within healthy individuals (11) as well as in populations characterized by asymmetric gait, such as post-stroke (13) and Parkinson’s disease (6). A SBT is composed of two independently-controlled belts (one under each leg) which can be set such that the two belts move at different speeds simultaneously. As the legs walk at different speeds, interlimb gait parameters such as step length and double limb support time adapt over time and demonstrate robust aftereffects (carry over) during overground gait following training (11). In particular, step length is initially asymmetric during the adaptation period (the limb walking on the slower belt exhibits a greater step length) and eventually becomes symmetric as the nervous system begins to consolidate the SBT walking task performance (10,11). During overground walking following the adaptation period, step length asymmetry is present in the direction opposite that experienced during initial adaptation (11,12). This phenomenon – termed the “aftereffect” - is thought to exist because the central nervous system overcorrects for the errors experienced during adaptation (11,12). Specifically, the aftereffect is apparent during conventional gait as the limb previously walking on the faster belt exhibits a longer step length as compared to the limb previously walking on the slower belt.

The storage or permanency of step length aftereffects following asymmetric locomotor training has become an important topic in the rehabilitation of populations characterized by gait asymmetry (1,3,16). Exciting findings have recently demonstrated that step length asymmetry (SLA) during overground gait can be at least partially restored in persons post-stroke following acute and chronic SBT training (13–15). Reisman and colleagues first observed improvements in step length symmetry during overground gait following a single bout of SBT walking (13). Further, more recent evidence has expanded upon these findings to show that repeated SBT walking can facilitate restoration of step length symmetry for at least three months following the cessation of SBT training in post-stroke responders (15).

A primary concern regarding the use of SBTs in rehabilitation is the current lack of accessibility of these devices to the general population. Alternatively, unilateral step training has also been shown to facilitate step length symmetry restoration in persons post-stroke (8). During unilateral stepping, the individual steps with one leg on a moving treadmill belt while the other leg stands stationary to the side. Importantly, this exercise can be performed with a traditional treadmill, and thus holds a significant advantage in availability over SBT walking. However, little is understood about how unilateral stepping induces aftereffects into overground gait; given that only one limb is moving, it seems unlikely that these aftereffects stem from the same mechanisms which drive the bilateral, error-based locomotor adaptation observed during SBT walking (11). Moreover, whether or not these aftereffects are of similar pattern and magnitude to SBT walking is currently unknown. A direct comparison of unilateral stepping and SBT walking aftereffects in healthy adults could provide important mechanistic information about how each exercise influences overground gait.

The primary purpose of this study was to compare the step length aftereffects during overground gait following SBT walking and unilateral stepping in healthy young adults. Because one foot remains stationary during unilateral stepping, step length cannot adapt bilaterally in a trial-and-error fashion as is thought to occur during SBT walking (11). Mechanisms such as use-dependent plasticity (2, 4, 5, 7) may still contribute to the aftereffects previously observed in a study of unilateral stepping (8), though these may be limited relative to SBT walking. We hypothesized that we would observe significant step length aftereffects during overground gait following the unilateral stepping and the SBT walking tasks, though the SBT aftereffects would be greater in magnitude. Because interlimb error correction is unlikely to be the mechanism that leads to overground aftereffects following unilateral stepping, we also sought to investigate the kinematic differences between SBT walking and unilateral stepping in order to determine kinematic patterns that lead to greatest overground aftereffects.

Methods

Protocol

Eighteen healthy young adults (22 ± 3 yrs, 171.1 ± 9.9 cm, 66.9 ± 11.4 kg, 9 females, 9 males) naïve to walking on a SBT and unilateral step training participated in this study. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in the study as approved by the University Institutional Review Board. Participants were fitted with retroreflective markers in accordance with the Plug-in-Gait full body marker set and kinematic data were collected using a 10-camera motion capture system (120 Hz; Vicon, Oxford, UK). Participants were asked “which leg the participant would use to kick a soccer ball?” to determine leg dominance; all participants were determined to be right leg dominant.

Participants first performed ten baseline overground gait trials across a 12-m walkway. They then walked on a SBT under various conditions (Woodway USA, Waukesha, WI). To begin, the speed of both belts was gradually increased until the participants reported being at the “fastest speed they felt comfortable walking”, which will herein be referred to as the “fast” walking speed (mean ± standard deviation: 1.38 ± 0.21 m/s); the “slow” speed was set as half of the fast speed. To accommodate the participants to the treadmill, they then walked for two minutes at the slow speed and two minutes at the fast speed followed by a two-minute washout period again at the slow speed (11). All participants then completed the following three treadmill conditions in a randomized order for 10 minutes each: 1) during slow unilateral, the left leg walked at the slow speed while the right leg was stationary, 2) during fast unilateral, the left leg walked at the fast speed while the right leg was stationary, and 3) during split-belt, the left leg walked at the fast speed while the right leg walked at the slow speed (Figure 1). Herein, the left (non-dominant) limb will be referred to across all conditions as the “slow limb” while the right (dominant limb) will be referred to as the “fast limb” (during the unilateral stepping conditions, we will refer to the stationary limb as the slow limb and the stepping limb as the fast limb to maintain consistency for comparisons across all treadmill conditions). In between each treadmill condition, ten trials of overground gait were performed. Kinematic data were collected during the first and last 30 seconds of each condition on the treadmill and for all overground gait trials. We tested unilateral stepping at the slow speed to maintain the same speed differences between limbs (i.e. speed ratio of 2:1 during SBT and 1:0 during slow unilateral stepping) to control for the effect of belt speed differences between unilateral stepping and SBT walking. Further, we tested unilateral stepping while the stepping limb walked at a speed matching the SBT fast speed (i.e. speed ratio of 2:1 during SBT and 2:0 during fast unilateral stepping) to control for the effect of walking speed.

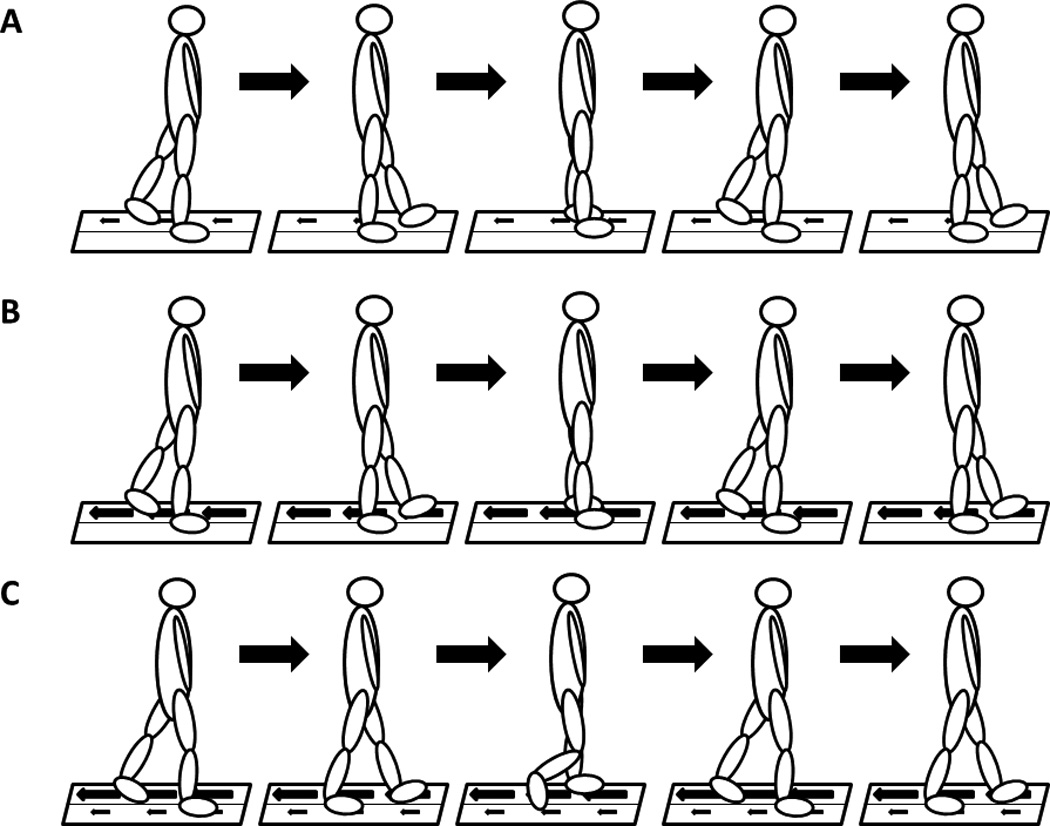

Figure 1.

Examples of each treadmill condition: A) slow unilateral stepping, B) fast unilateral stepping, and C) split-belt treadmill walking. Thick black arrows indicate that the belt is moving at the fast speed while thin black arrows indicate that the belt is moving at the slow speed. A lack of arrows on the treadmill belt indicates that the belt is stationary. Black arrows between the walking figures indicate progression in time.

Data analysis

Heel-strikes and toe-offs were manually labeled in Vicon Nexus software based on marker trajectories. Step length was calculated as the distance between the ankle markers along the walking axis at heel-strike. To test the hypothesis that SBT walking induces greater aftereffects than unilateral stepping, SLA was calculated for each stride of the overground gait tasks by subtracting right step length from left step length. SLA was then averaged across the first five overground gait strides following each task.

To compare the gross movements of the limbs during each of the three treadmill conditions and investigate how these movements were changing over the timecourse of each condition and into the aftereffects, we calculated limb angles at heel-strike and toe-off by calculating the angle between a vertical line and a vector connecting the markers on the anterior superior iliac spine and lateral malleolus. Limb angle describes the pattern of foot placement relative to the pelvis during each treadmill condition (15). While observing the participants as they performed the unilateral stepping tasks, it became apparent that there was considerable variability among participants in terms of the strategies used to perform the tasks. It appeared that some participants fully extended the stationary limb and allowed the treadmill to passively move the stepping foot through the stance phase while others seemed to actively transfer their body weight between limbs as if they were normally walking. We hypothesized that these different strategies may affect the aftereffect magnitude, and thus we investigated relationships between the lower extremity kinematics and aftereffect magnitude following the unilateral stepping conditions. We calculated relative joint angles at the ankle, knee, and hip for the lower limbs in the sagittal plane using the Vicon dynamic Plug-in-Gait model to provide specific detail about the kinematics of each joint across treadmill conditions. These joint angle profiles were subsequently temporally-normalized to 100% of the gait cycle. During unilateral stepping, the joint angles of the stationary limb were temporally-normalized to the gait cycle of the stepping limb. We then calculated the peak flexion and extension angles of each joint bilaterally during each gait cycle over the last 30 seconds of the three treadmill conditions. We investigated the kinematics over this specific time period because it is demonstrative of how the participants were moving once they had most fully adapted to the task and would be the pattern which is immediately carried over to the overground gait trials.

Statistical analysis

Three separate repeated measures ANOVAs were performed to compare 1) the mean SLA, 2) the mean slow limb step length, and 3) the mean fast limb step length of the first five overground gait strides following each condition and baseline (baseline, slow unilateral, fast unilateral, and SBT walking). We also performed separate repeated measures ANOVAs to compare limb angles at heel-strike and toe-off among 1) the first five strides of each treadmill condition, 2) the last five strides of each treadmill condition, and 3) the first five over ground gait strides following each condition and baseline (baseline, slow unilateral, fast unilateral, and SBT walking). Bonferroni post-hoc adjustments were performed where appropriate. Two-tailed Pearson’s correlations were performed to analyze relationships between the mean SLA of the first five strides of the overground gait trials following fast and slow unilateral stepping and both the mean peak flexion and extension joint angle values of the lower extremity sagittal joint angles during the last 30 seconds of each unilateral stepping conditions. A priori statistical significance was set at P≤0.05.

Results

Step length aftereffects following SBT walking and unilateral stepping

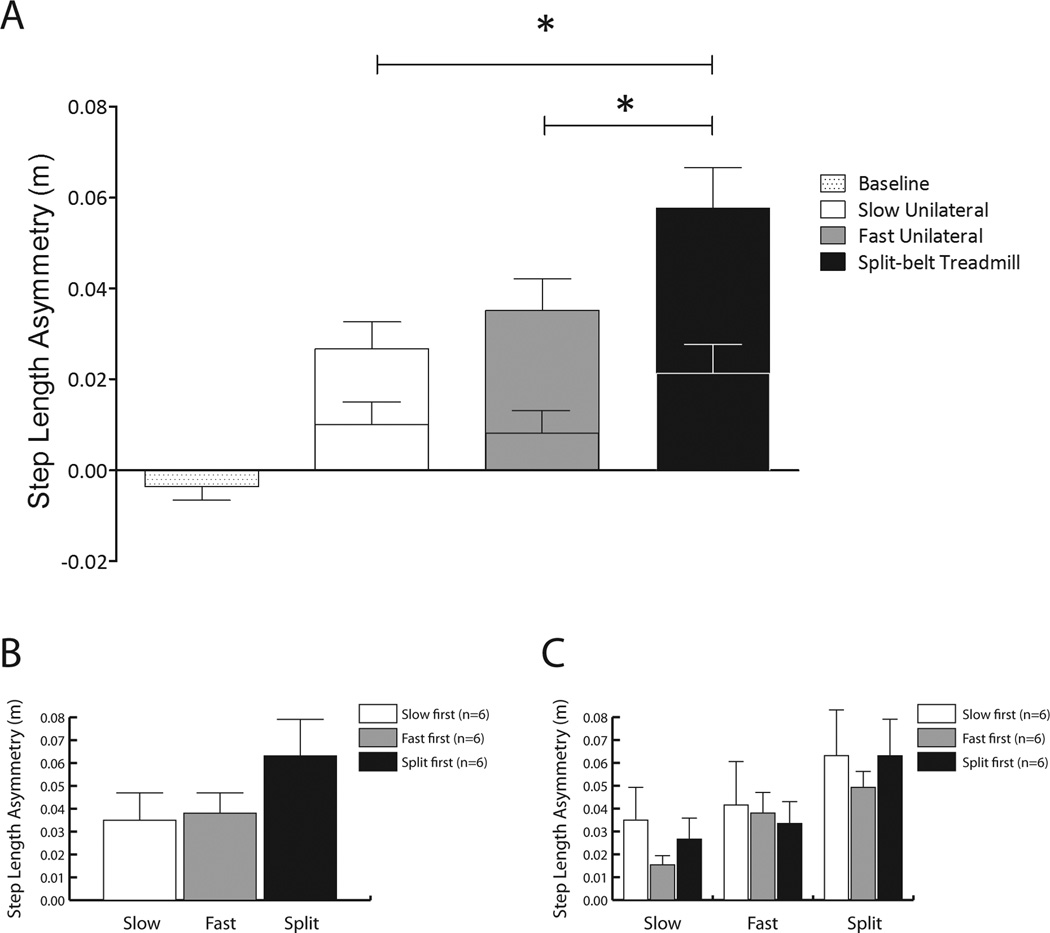

We observed a significant main effect of condition on SLA (p<.001). Post-hoc analyses revealed that SLA was significantly larger during the first five strides of overground gait following slow unilateral, fast unilateral and SBT walking compared to baseline (all P<.001, Figure 2A). A significantly larger aftereffect was observed following SBT walking compared to fast and slow unilateral (P=.005 and <.001, respectively). No significant difference (P>.05) was observed in SLA between slow unilateral and fast unilateral stepping conditions. The order in which the conditions were performed did not affect the aftereffects following other conditions, as we observed the same general patterns in the data both when comparing only the participants who performed each condition first (Figure 2B) and when comparing all participants across conditions (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

A) Mean step length asymmetry for overground walking at baseline and over the first (tall bars) and last (short bars) five strides of overground gait after slow unilateral, fast unilateral, and split-belt treadmill walking. * indicates P<.05. B) Mean step length asymmetry over the first five strides of overground walking after slow unilateral, fast unilateral, and split-belt treadmill walking when only the data from participants performing each condition first are considered. C) Mean step length asymmetry over the first five strides of overground walking after slow unilateral, fast unilateral, and split-belt treadmill walking across all participants and conditions. The data in B) and C) follow the same statistical patterns observed in Figure 2A with indicators of significance omitted to preserve clarity. Error bars indicate standard error.

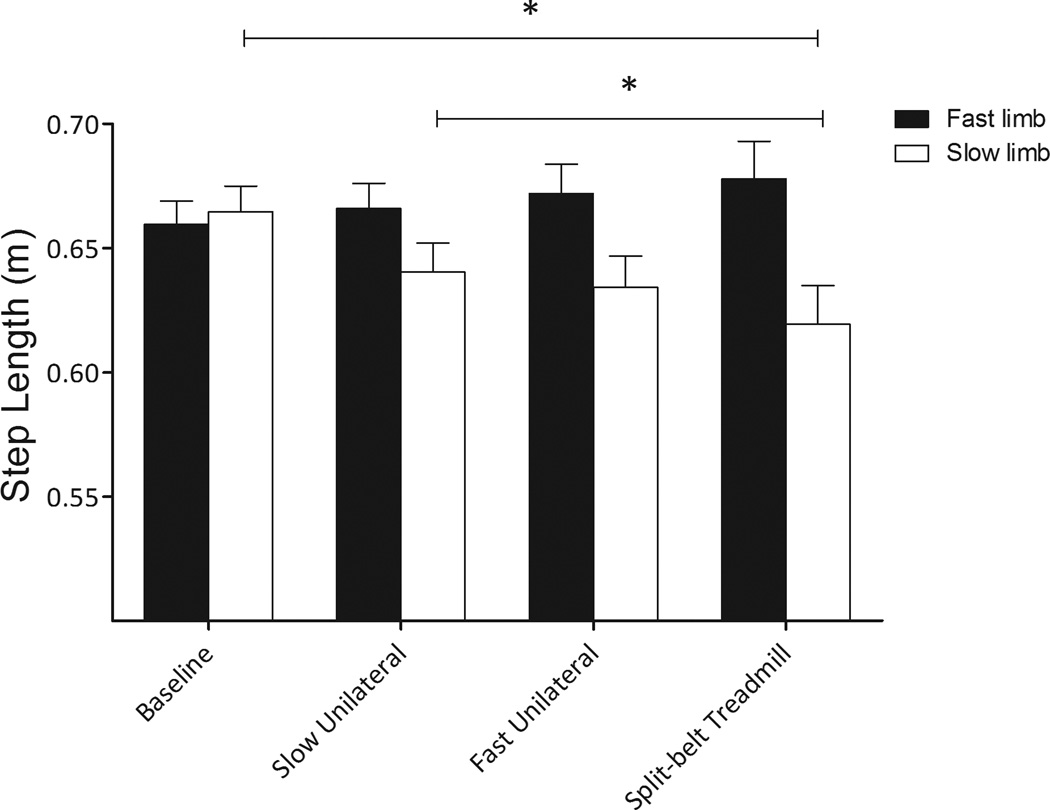

We also observed a significant main effect of condition on slow limb step length (P<.001). Post-hoc analyses revealed that the slow limb step length was significantly shorter during overground gait following SBT walking as compared to baseline and overground gait following slow unilateral (P =.008 and P=.032, respectively, Figure 3). However, slow limb step length was not significantly different following slow or fast unilateral as compared to baseline (P=.109 and P=.073, respectively). Further, we did not observe a significant effect of condition on fast limb step length (P=.265). Thus, SLA observed following all three conditions resulted primarily from a shortening of the slow limb step.

Figure 3.

Mean step length values for each limb during baseline overground gait and the first five strides of overground gait immediately following slow unilateral, fast unilateral, and split-belt treadmill walking. * indicates P<.05. Error bars indicate standard error.

Kinematic comparisons between SBT walking and unilateral stepping

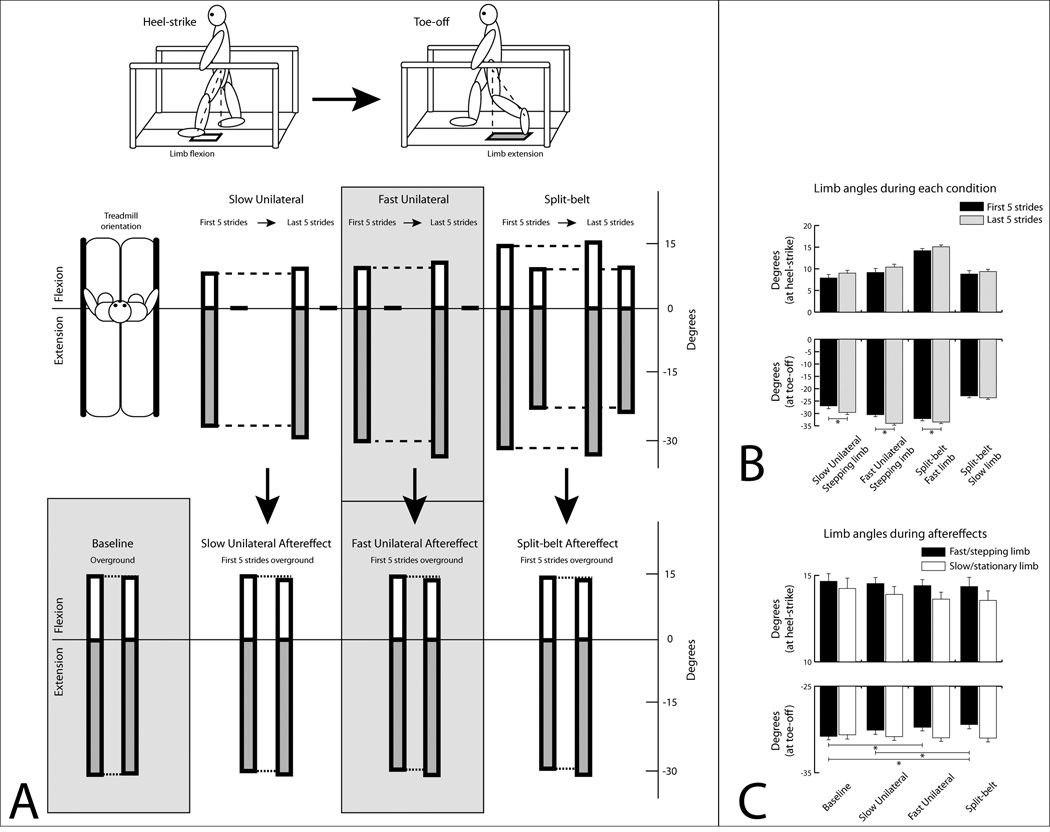

A bird’s eye diagram of limb angle patterns (averaged across participants) during the first and last five strides of each treadmill condition and during the aftereffects following each treadmill condition is shown in Figure 4A. Group mean±SE limb angles at heel-strike and toe-off are shown for the first and last five strides of each treadmill condition (Figure 4B) and for each limb during the aftereffects (Figure 4C). The limb angle at heel-strike did not change significantly from the first five strides to the last five strides of any condition (all P>.05, Figure 4B). During the first and last five strides of each condition, the limb angle at heel-strike was significantly more flexed in the fast limb during SBT walking compared to the slow limb during SBT walking and the fast limb during both unilateral stepping conditions (all P<.001; indications of significant differences among conditions omitted in Figure 4B to preserve figure clarity). The limb angle at toe-off became significantly more extended from the first five strides to the last five strides in the fast limb (but not the slow limb) during SBT walking and both unilateral stepping conditions.

Figure 4.

A) A bird’s eye view of the mean limb angle orientations throughout the gait cycle for the first and last five strides of each treadmill condition (top) and the first five strides of overground walking immediately following each condition (bottom). The shaded white boxes indicate the mean amount of limb flexion at heel-strike while the shaded gray boxes indicate the mean amount of limb extension at toe-off. B) Mean±SE limb angles over the first (black) and last (gray) five strides of each treadmill condition at heel-strike (top) and toe-off (bottom). * indicates P<.05, indications of significant differences among conditions omitted to preserve figure clarity. C) Mean±SE limb angles of the fast (black) and slow (white) limb at heel-strike (top) and toe-off (bottom) over the first five strides of overground gait following each treadmill condition. * indicates P<.05, indications of significant differences between limbs omitted to preserve figure clarity.

During the first five strides of overground walking following each condition, the limb angle at heel-strike was significantly more flexed while the limb angle at toe-off was significantly less extended in the fast limb than in the slow limb (all P<.05, Figure 4C; indications of significant differences between limbs omitted in Figure 4C to preserve figure clarity). We did not observe any significant differences among conditions in limb angle at heel-strike; however, the limb angle at toe-off was significantly less extended in the fast limb following both fast unilateral and SBT walking compared to baseline (all P<.05). The limb angle at toe-off was also significantly less extended in the fast limb following SBT walking compared to slow unilateral (P<.05), which contributes to the differences in slow limb step length between these two conditions observed in Figure 3.

In sum, the fast limb became more extended at toe-off from the first five strides to the last five strides during SBT walking and both unilateral stepping conditions while the degree of limb flexion at heel-strike remained relatively constant throughout the task in all conditions. The fast limb generates greater extension during SBT walking as compared to the slow limb during SBT walking as well as the stepping limb during both unilateral conditions. These movement patterns lead to aftereffects across conditions which are characterized by significantly larger limb flexion and significantly smaller limb extension in the fast limb as compared to the slow limb. These between-limb differences in limb flexion at heel-strike and limb extension at toe-off are largest following SBT walking as compared to both fast and slow unilateral stepping (Figure 4C) and are similar to the findings of Malone and colleagues regarding limb angle patterns during SBT walking (see Figure 5 in (9)).

Figure 5.

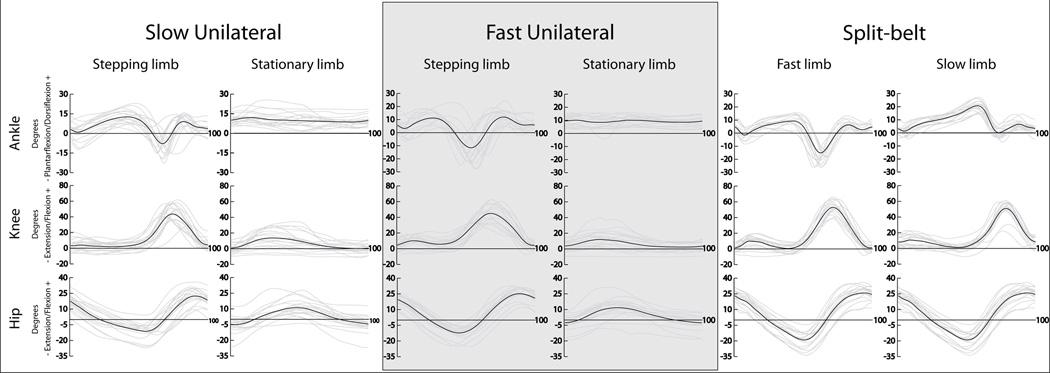

Bilateral individual (gray) and mean (black) sagittal joint angle profiles for the hip, knee, and ankle during the last 30 seconds of all three treadmill conditions.

Associations between sagittal joint angle profiles during unilateral stepping and aftereffect storage

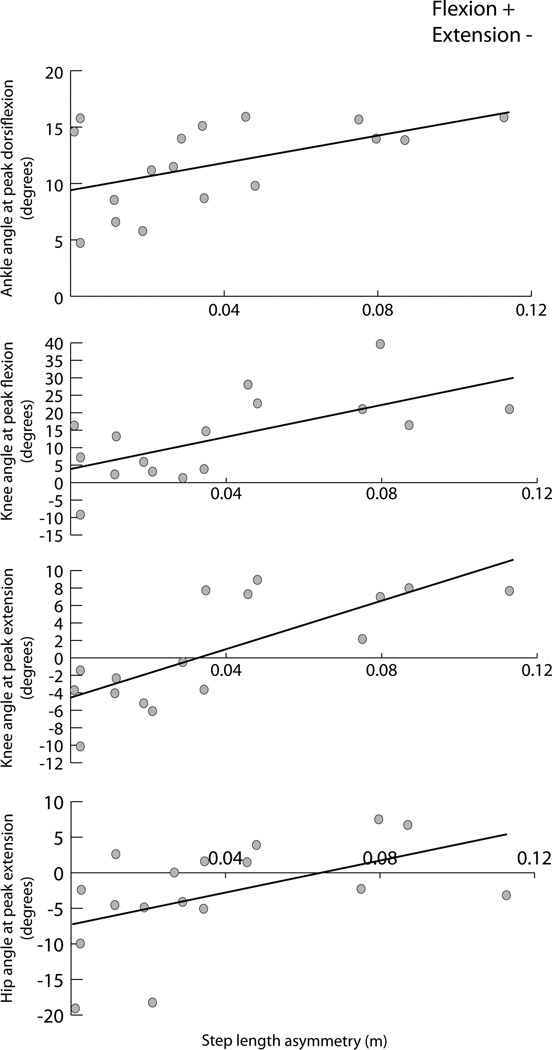

Individual and mean ensemble sagittal joint angle profiles at the hip, knee, and ankle are shown for each condition in Figure 5. We observed significant associations between SLA during overground walking following fast unilateral stepping and mean peak ankle dorsiflexion (r=.489, P=.046), knee flexion (r=.635, P=.006), knee extension (r=.749, P=.001), and hip extension (r=.514, P=.035) of the stationary limb during the last 30 seconds of fast unilateral stepping (Figure 6). Note that joint angle values of negative values are considered plantarflexion for the ankle and extension for the knee and hip, and thus the positive correlations between SLA and peak extension at the knee and hip indicate that increased SLA was associated with decreased peak extension. There were no significant associations between SLA following slow unilateral stepping and peak joint angles during the last 30 seconds of slow unilateral stepping.

Figure 6.

Associations between the mean step length asymmetry over the first five strides of overground gait following fast unilateral stepping and (from top to bottom) the ankle angle at peak dorsiflexion, the knee angles at peak flexion and extension, and the hip angle at peak extension during the last 30 seconds of fast unilateral stepping. All four relationships are statistically significant (P<.05).

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to compare the aftereffects following SBT walking and unilateral stepping in order to assess the potential of the two techniques to induce changes in step length symmetry following acute bouts of training. Consistent with previous research in SBT walking in healthy young adults (11), we observed significant SLA during overground gait immediately following acute bouts of SBT walking. The limb previously walking on the fast belt produced a greater step length than the limb previously walking on the slow belt during overground gait after the acute bout. We also observed significant SLA during overground gait following acute bouts of slow and fast unilateral stepping. However, the magnitude of the aftereffects following SBT walking was greater than those following either of the unilateral stepping conditions. To our knowledge, these are the first findings to demonstrate that acute SBT walking induces a larger change in SLA during overground gait as compared to acute unilateral stepping.

We also aimed to compare and contrast the kinematics of unilateral stepping and SBT walking in order to gain insight as to which parameters are changing over time and how these changes may influence the aftereffects. During both SBT walking and unilateral stepping, the limb angles of the fast/stepping limb changed in similar fashion over the course of the task such that the pattern of limb flexion at heel-strike remained relatively unchanged while limb extension at toe-off increased. These movement patterns resulted in aftereffects during overground walking that were characterized by significantly greater limb flexion and significantly lesser limb extension in the fast limb as compared to the slow limb. Thus, the aftereffects following SBT walking and unilateral stepping show similar kinematic patterns, though the between-limb differences in limb flexion at heel-strike and limb extension at toe-off were largest following SBT walking (Figure 4C), resulting in the greatest SLA.

The kinematic changes which occur over time in the fast/stepping limbs appear somewhat similar across the three treadmill conditions; however, SBT walking and unilateral stepping likely induce aftereffects through different mechanisms. During SBT walking, intralimb patterns remain relatively constant throughout a single session as interlimb parameters (e.g., step length) are gradually altered by phase shifting one limb relative to the other (11). This causes the initially asymmetric step lengths to adapt toward symmetry as the nervous system gains information about the perturbation (i.e., the asymmetric belt speeds) by incorporating reactive feedback and predictive feedforward responses. Once the perturbation is removed, it is proposed that the nervous system overcorrects for the error as an aftereffect is observed in the direction opposite the asymmetry experienced during initial adaptation (11). In sum, the nervous system adapts to SBT walking and stores aftereffects within the traditional trial-and-error framework commonly associated with motor adaptation. However, the aftereffects observed following unilateral stepping do not appear to result from error-based adaptation. In contrast to SBT walking, in which there are pronounced changes in interlimb parameters occurring bilaterally throughout the timecourse of the task, it is unlikely that interlimb spatiotemporal error is detected during unilateral stepping given that only one limb is stepping. Thus, the aftereffects observed following unilateral stepping may result primarily from use-dependent plasticity. The idea of use-dependent plasticity suggests that repetition of movements performed in a particular direction or with a particular velocity will bias future movements to occur in a similar fashion (2, 4, 5, 7). Given that the stationary foot does not move throughout the entirety of the unilateral stepping task, one might expect that this foot would take a shorter step upon re-exposure to unconstrained overground gait. Indeed, this is precisely what was observed in the present study. It is also possible that physiological mechanisms unrelated to motor learning, such as stretching of the stepping limb hip flexor musculature, may contribute to the step length aftereffects following unilateral stepping.

Our findings do not discredit unilateral stepping as a potentially effective therapy for asymmetric gait deficits. Our results are in support of previous findings by Kahn and Hornby which suggest that unilateral stepping does indeed induce significant aftereffects in step length symmetry during overground gait. Further, these aftereffects are similar in direction to those observed after SBT walking (i.e., the fast/stepping limb takes a larger step) (8), albeit at a lesser magnitude. Our results expand upon these findings to suggest that aftereffects following unilateral stepping are largest when the stationary limb does not remain fully extended throughout the training duration. As shown in Figure 5, we observed considerable between-participant variability in the kinematics of the stationary limb during unilateral stepping. Some participants appear to have remained more-or-less fully extended at the hip and knee and neutral at the ankle, likely maintaining their body mass directly over the stationary limb throughout the task and allowing the treadmill to passively move the stepping limb through the stance phase. However, our results suggest that this pattern reduces aftereffect magnitude, as the participants who stored the largest aftereffects demonstrated the greatest amount of flexion at the ankle, knee, and hip of the stationary limb during the stance phase of the stepping limb. We suggest that these flexion patterns may have resulted from a more active stance phase of the stepping limb in which body weight was actually transferred between limbs in a fashion more similar to walking. Given that the stance kinetics are reduced during slow walking as compared to fast walking, this rationale may also explain why similar relationships were not observed between the kinematics during slow unilateral stepping and the subsequent aftereffects during overground gait. However, future studies should investigate kinetic changes in each limb during unilateral stepping to provide clearer insight.

As our study is limited to an investigation of healthy young adults, future research should also compare the magnitude of step length aftereffects following SBT walking and unilateral stepping in populations with SLA. There are inherent challenges which can often accompany the rehabilitation of individuals within these populations (low aerobic capacity, significantly diminished global gait and movement ability, impairments in cognition and motor learning, etc). However, previous research has successful translated locomotor adaptation protocols from healthy individuals into asymmetric populations (8, 11–15). Thus, these results are a promising first step in directly comparing unilateral stepping and SBT walking protocols and furthering the understanding as to how these exercises may affect gait asymmetry in pathological populations. It should also be noted that this study primarily compared initial aftereffects of the SBT walking and unilateral stepping after only an acute bout of treadmill walking. Studying the long-term effects of SBT and unilateral stepping training over periods of weeks in persons with asymmetric gait would provide a more complete understanding of the effectiveness of each method in a rehabilitation setting. Finally, SLA was not completely washed out following any of the exercises and this may have influenced subsequent aftereffect magnitudes (Figure 2A). Thus, while the general patterns of the aftereffects following each exercise were not affected by the order in which the exercises were performed (Figures 2B and 2C), specific effects on the magnitude of the aftereffects is not known.

Conclusion

Both SBT walking and unilateral stepping induce significant step length aftereffects during overground gait in healthy young adults. In this study, we demonstrated that the greatest step length aftereffects are observed following SBT walking. We suggest that these differences in aftereffect magnitude may be driven by differences in the mechanisms occurring during each exercise; SBT walking may incorporate trial-and-error adaptation, use-dependent plasticity, and reinforcement learning whereas unilateral stepping does not appear to incorporate any trial-and-error bilateral adaptation. It is, however, important to note that the aftereffects following unilateral stepping and SBT walking are of a similar kinematic pattern. Further studies directly comparing these two exercises in pathological populations could provide more direct evidence as to the effectiveness of each method as gait rehabilitation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH grant 1R21AG033284-01A2, and the UF National Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement from the American College of Sports Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

All authors report they have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) the work of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Brandstater ME, de Bruin H, Gowland C, Clark BM. Hemiplegic gait: analysis of temporal variables. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64:583–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bütefisch CM, Davis BC, Wise SP, Sawaki L, Kopylev L, Classen J, Cohen LG. Mechanisms of use-dependent plasticity in the human motor cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3661–3665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050350297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen G, Patten C, Kothari DH, Zajac FE. Gait differences between individuals with post-stroke hemiparesis and non-disabled controls at matched speeds. Gait Posture. 2005;22:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Classen J, Liepert J, Wise SP, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Rapid plasticity of human cortical movement representation induced by practice. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1117–1123. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diedrichsen J, White O, Newman D, Lally N. Use-dependent and error-based learning of motor behaviors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5159–5166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5406-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietz V, Zijlstra W, Prokop T, Berger W. Leg muscle activation during gait in Parkinson's disease: adaptation and interlimb coordination. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;97(6):408–415. doi: 10.1016/0924-980x(95)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang VS, Haith A, Mazzoni P, Krakauer JW. Rethinking motor learning and savings in adaptation paradigms: model-free memory for successful actions combines with internal models. Neuron. 2011;70(4):787–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn JH, Hornby TG. Rapid and long-term adaptations in gait symmetry following unilateral step training in people with hemiparesis. Phys Ther. 2009;89(5):474–483. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malone LA, Bastian AJ, Torres-Oviedo G. How does the motor system correct for errors in time and space during locomotor adaptation? J Neurophysiol. 2012;108(2):672–683. doi: 10.1152/jn.00391.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morton SM, Bastian AJ. Cerebellar contributions to locomotor adaptations during splitbelt treadmill walking. J Neurosci. 2006;26(36):9107–9116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2622-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reisman DS, Block HJ, Bastian AJ. Interlimb coordination during locomotion: what can be adapted and stored? J Neurophysiol. 2005;94(4):2403–2415. doi: 10.1152/jn.00089.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reisman DS, Wityk R, Silver K, Bastian AJ. Locomotor adaptation on a split-belt treadmill can improve walking symmetry post-stroke. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 7):1861–1872. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reisman DS, Wityk R, Silver K, Bastian AJ. Split-belt treadmill adaptation transfers to overground walking in persons poststroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23(7):735–744. doi: 10.1177/1545968309332880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reisman DS, McLean H, Bastian AJ. Split-belt treadmill training poststroke: a case study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2010;34(4):202–207. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e3181fd5eab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reisman DS, McLean H, Keller J, Danks KA, Bastian AJ. Repeated Split-Belt Treadmill Training Improves Poststroke Step Length Asymmetry. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(5):460–468. doi: 10.1177/1545968312474118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Schroeder HP, Coutts RD, Lyden PD, Billings E, Jr, Nickel VL. Gait parameters following stroke: a practical assessment. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1995;32(1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]