Abstract

Objective

Although poor sleep is a consequence of pain, sleep disturbance reciprocally induces hyperalgesia and exacerbates clinical pain. Conceptual models of chronic pain implicate dysfunctional supraspinal pain processing mechanisms, mediated in part by endogenous opioid peptides. Our preliminary work indicates that sleep disruption impairs psychophysical measures of descending pain modulation, but few studies have investigated whether insufficient sleep may be associated with alterations in endogenous opioid systems. This preliminary, exploratory investigation sought to examine the relationship between sleep and functioning of the cerebral mu opioid system during the experience of pain in healthy participants.

Subjects and Design

Twelve healthy volunteers participated in a 90-minute positron emission tomography imaging scan using [11C]Carfentanil, a mu opioid receptors agonist. During the session, pain responses to a 10% topical capsaicin cream were continuously rated on a 0–100 scale. Participants also completed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

Results

Poor sleep quality (PSQI) was positively and significantly associated with greater binding potential (BP) in regions within the frontal lobes. In addition, sleep duration was negatively associated with BP in these areas as well as the temporal lobe and anterior cingulate.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that poor sleep quality and short sleep duration are associated with endogenous opioid activity in these brain regions during the application of a noxious stimulus. Elucidating the role of the endogenous opioid system in mediating some of the associations between sleep and pain could significantly improve our understanding of the pathophysiology of chronic pain and might advance clinical practice by suggesting interventions that could buffer the adverse effects of poor sleep on pain.

Keywords: Sleep, Pain, Capsaicin, PET, Imaging, Binding Potential, [11 C]Carfentanil

Introduction

Sleep has become an increasingly recognized factor in determining pain perception. Systems that regulate both arousal and pain are neurobiologically intertwined, e.g., Foo and Mason, and Watson et al. [1,2]. Both subjective and objective, polysomnography (PSG), measures suggest that the vast majority of patients with chronically painful condition experience sleep disturbances [3]. Experimental studies in both animals and humans demonstrate that many forms of sleep disruption lead to next-day reductions in laboratory measures of pain threshold and tolerance (see Campbell et al. [4] for review). Emerging evidence documents that sleep disturbance is associated with risk for developing pain complaints [5–8] and disrupted sleep following acutely painful injury is associated with developing persistent post-injury pain [9,10]. In addition, sleep duration predicted next-day pain frequency in a recent microlongitudinal study [11]. However, little is known regarding the mechanisms underlying these connections.

The endogenous opioid system partially mediates descending inhibition of pain signals and is one hypothesized mechanism by which sleep might directly influence the pain experience [12]. A small number of animal studies suggest that sleep deprivation may impair endogenous opioid function. For example, sleep deprivation alters the µ and δ opioid receptor function in mesolimbic circuits [13] and diminishes basal endogenous opioid levels in the brain [14]. Sleep deprivation downregulates central opioid receptors [15] and has been associated with decreased morphine effectiveness, as well as central nervous system opioid insufficiency in the limbic system and hypothalamus, areas associated with regulating pain and sleep in rats [16,17].

Although human work is scarce, Frecska and colleagues [18] found that depressed patients exhibiting blunted prolactin response to fentanil, a mu opioid receptor (MOR) agonist, with undisturbed sleep exhibited an enhanced dopamine-mediated prolactin response after sleep deprivation, suggesting a direct relationship between sleep deprivation and altered opioid function. Sleep disturbance has been associated with opioid use in a large cohort of chronic noncancer pain patients receiving long-term opioid therapy [19], and some research in burn injury survivors suggests that a night of poor sleep may be linked with next-day increases in opioid dose [20,21]. These findings in cohort studies hint that impaired sleep may reduce the analgesic efficacy of oral opioids (e.g., necessitating the need for higher doses). A direct correlation between daytime sleepiness and diminished analgesic effects of codeine on thermal pain sensitivity has also recently been documented [22].

In addition, our group has demonstrated (in a conditioned pain modulation [CPM] paradigm) that experimental sleep disruption impairs the ability to inhibit acute pain during experimentally induced tonic pain [12]. Similar pain inhibition tests are at least partially opioid-mediated as their effects are reversed via acute administration of MOR antagonists [23]. We have also found that among a cohort of clinical pain patients, longer sleep and higher sleep efficiency were positively associated with better functioning of these same opioid-mediated systems, suggesting that disrupted sleep may be a risk factor for inadequate pain-inhibitory processing [24]. Recently, our group further documented reduced endogenous pain-inhibitory capacity and enhanced neuroinflammatory responses (e.g., increased skin flare and augmented secondary hyperalgesia) to a sustained capsaicin stimulus among individuals reporting reduced sleep duration (<6.5 hours/night) [4]. Therefore, preliminary work from our laboratory and others indicates the possibility of a direct relationship between sleep disruption and descending pain modulatory systems.

Collectively, while sleep disturbance-induced alterations in opioid systems have been proposed (and clearly plausible given the animal literature and several indirect human studies), no human research to date has examined this relationship directly in humans using neuroimaging techniques. We hypothesize that insufficient sleep may impair or reduce central endogenous opioid systems, particularly in opioid-rich regions of the pain inhibitory matrix, including frontal areas and the anterior cingulate cortex, based on previous work [25]. This secondary, exploratory investigation sought to examine the relationship between sleep and specific binding of an MOR radioligand, [11C]Carfentanil ([11C]CFN) using positron emission tomography (PET) under the capsaicin pain-induction model in healthy participants. PET is the only technique available for examining brain receptor characteristics in living human subjects.

Methods

A total of 14 healthy individuals, recruited through posted flyers, completed this study. Two individual were dropped from analyses for failing to complete the required magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (described later). Thus, 12 individuals (50% female) were included in the current analyses (see Table 1 for descriptive information). Eligibility criteria included having no pain condition or medical disorders, active alcohol or drug abuse problem; or use of narcotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and muscle relaxants as well as scanner specific criteria, including having nonremovable metal objects, being left-handed, or wearing glasses (adequate vision and wearing contacts were allowed). All study-related procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained upon arrival for a screening session after which participants completed a health history questionnaire. Participants underwent screening procedures, as described later, and were scheduled for a PET imaging session at least 1 week from the screening. Participants underwent MRI to allow anatomical localization of brain structures. Participants were provided with monetary compensation for their participation.

Table 1.

Demographic and behavioral variables

| Variable | Sleep (N = 12) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 33.7 (17.0) |

| Sex (% female) | 50 |

| Race (% White) | 50 |

| Ethnicity (% Hispanic) | 33.3 |

SD = standard deviation.

Screening Session

The screening session was conducted in order to determine eligibility and any potential difficulty during PET imaging, including a ceiling or floor effect in pain ratings that would render the PET session data unusable. Following consent procedures and questionnaires, a piece of thick, nonporous dressing with a 6.25 cm2 hole cut into it (used as a template to standardize the area of capsaicin cream application) was applied to the skin on the dorsal, left (nondominant) hand. As described in more detail previously [26], approximately 0.35 g of 10% capsaicin cream was applied inside the area and evenly spread on the skin. The area was then covered by Tegaderm transparent dressing (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN, USA) and a peltier-device heating element (Medoc US, Minneapolis, MN, USA) strapped to the area in order to maintain a constant skin temperature. This device was held at 38°C for the first 30 minutes of the session. This methodology normally produces pain that is rated as moderately intense and which peaks at 15–26 minutes post-application and plateaus for approximately 1 hour afterwards [27,28]. Participants provided pain intensity ratings at 30-second intervals on a 0–100 computerized visual analog scale (VAS) for a total of 35 minutes. During the testing period, participants also practiced playing a series of video games for future sessions (for separate analyses) in 5-minute segments. Following completion of the session, the capsaicin cream was removed from the skin.

Questionnaires

Sleep

Participants completed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI [29]), a widely used 19-item self-report questionnaire for the evaluation of sleep quality over the previous month. The PSQI includes seven component scales, which were added together to yield a global sleep quality score used in the current analyses. A global PSQI score of 5 or greater differentiates “poor” from “good” sleepers with well-validated sensitivity [29]. As in our previous studies, we also examined the individual habitual sleep duration item separately (i.e., “During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night?” [This may be different than the number of hours you spent in bed.]).

Mood Questions

Given well-established interrelationships between mood, pain, and sleep, participants were asked to describe their current mood prior to the testing sessions on a 10-point scale (anchored by “Extremely Good” to “Extremely Bad”).

PET Procedures

Upon arrival, participants provided a urine sample for drug and pregnancy testing and were weighed. Prior to the study, subjects had one venous catheter inserted in the antecubital vein in one arm for the radioligand injection and were positioned in the scanner with the head restrained to reduce head motion during PET data acquisition. Participants were fitted with prism-angled glasses (directed vision downward at a 90° angle) that allowed for viewing a ceiling-mounted computer monitor where they were to rate their pain, and the capsaicin and thermode were applied as described earlier. PET data were acquired on a high-resolution research tomograph (CPS Innovations, Inc., Knoxville, TN, USA). A 6-minute transmission scan was acquired using a rotating Cs-137 source for attenuation correction. Dynamic PET acquisition was then performed in a three-dimensional list mode for 90 minutes following an intravenous bolus injection of [11C]CFN, an agonist radioligand for MORs (mean and standard deviation [SD]: 18.9 ± 1.8 mCi; range = 15.5–21.5 mCi; specific activity: 7,577 ± 1,987 mCi/µmol, ranging between 3,363 and 10,889 mCi/µmol). This dose of Carfentanil is known to be subthreshold for effects on pain perception [30]. Pain rating data were collected every minute over a 90-minute interval. Participants rated their pain on a computerized 0–100 VAS (0 = no pain and 100 = most intense pain imaginable) by manipulating a mouse in order to adjust the height of the VAS projected on the computer screen. Participants were also scheduled for a second PET imaging session, which took place at least 1 week following the pain alone session. It was identical to the first except they also played video games, while the capsaicin and thermode were applied in order to investigate distraction analgesia (data not reported here).

PET scans were reconstructed using the iterative ordered-subset expectation-maximization algorithm correcting for attenuation, scatter, and dead-time [31]. The radioactivity was corrected for physical decay to the injection time and re-binned to 25 dynamic PET frames of 256 (left-to-right) by 256 (nasion-to-inion) by 207 (neck-to-cranium) voxels whose dimensions were 1.2 mm cubic. The frame schedules were six 30-second, five 1-minute, five 2-minute, and nine 8-minute frames.

Data Analysis

PET Data Analysis

Volumes of Interest

Volume of interest (VOI) analyses were limited to specific areas including the frontal, temporal, parietal, and cingulate hippocampus, insula, and thalamus given the role of the regions in pain processing [25]. VOIs for hippocampus, insula, and thalamus were defined manually on spoiled gradient recalled echo MRI using a locally developed VOI-defining tool. For the remaining VOIs, a standard VOI template ([32,33]; available at http://www.loni.ucla.edu) was spatially transferred to individual subjects’ MRI using the MRI-to-MRI spatial normalization parameters obtained with the statistical parametric mapping (SPM) spatial normalization module utilizing the unified segmentation method ([34]; available at http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), and edited to suit outlines of the structures given by the MRI. Those VOIs were transferred to PET space according to the MRI-to-PET coregistration parameters obtained with the SPM5 coregistration module [35] and applied to individual PET frames to obtain time–radioactivity curves of VOI.

Derivation of PET Outcome Variable

Reference tissue graphical analysis (RTGA; Logan et al., 1996) [36] was used to obtain PET outcome variable, binding potential (BPND) in regions. In RTGA, t* (the start of asymptote) was set to 20 minutes using the occipital cortex as the receptor free region with the brain-to-blood clearance rate constant set to 0.104 minutes−1 [37].

Voxel-Wise Statistical Analysis—SPM

SPM analyses were conducted to substantiate VOI-based findings and determine regional changes and correlations in [11C]CFN BPND without restricting predetermined regions. Images of BPND were generated by applying RTGA to individual voxels and transferred to a standard space using aforementioned parameters of PET-to-MRI coregistration and MRI-to-MRI spatial normalization in one step. Then, BPND images were smoothed by a Gaussian kernel of 10 mm full-with at half maximum before submitting to SPM analyses. A two sample t-test design of SPM5 was used to examine group difference in BPND, while a simple regression design was used to correlate behavioral indices and psychometric test results to BPND. A significance level of P < 0.001, uncorrected with the minimum cluster volume set at 30 voxels (k = 30 or 0.24 mL) was applied for both types of analyses.

Statistical Analyses

[11C]CFN BPND were averaged by right and left side to calculate one BPND value for each area of interest. Correlational analyses were conducted on the sleep variables, psychophysical data, and [11C]CFN BPND values in each brain region of interest. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated using the continuous PSQI global score and reported sleep duration. In addition pain and mood variables were controlled in a separate partial correlation analysis as a secondary more conservative approach. Further, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to examine differences of regional BPND between sleep groups (separated by a sleep duration cut-off of 6.5 hours/night) based on our previous work [4]. Separate ANOVAs controlling for sex were also conducted in order to evaluate any potential sex effects.

Results

As displayed in Table 2, the mean PSQI global score was 5.3, sleep duration was 6.6 hours/night and pain ratings averaged 27.5 (on a 0–100 scale; range from 2.8 to 74.7). PSQI global sleep and sleep duration were highly correlated, while neither sleep measure was correlated with pain or mood (Table 2). Further, pain was not significantly correlated with BP values in any brain region, nor did it alter the pattern of correlations found between sleep variables and BP when used as a covariate. Pain and mood ratings were not significantly correlated with each other, nor was mood correlated with sleep variables, or with BP (Ps > 0.05). However, when controlling for pain and mood, a slight variation in significance was observed (Table 2). The pattern of results and significance levels did not vary substantially based on sex.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix between (continuous) sleep data and binding potential (BP)

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PSQI global | 5.3 (3.3) | 1 | |||

| 2. Sleep duration | 6.6 (1.1) | −0.87* | 1 | ||

| 3. Pain | 27.5 (26.8) | 0.24 | −0.13 | 1 | |

| 4. Mood | 1.6 (2.7) | 0.14 | −0.15 | 0.55 | 1 |

| 5. Frontal | 1.0 (0.17) | 0.65*‡ | −0.67*‡ | 0.24 | 0.01 |

| 6. Temporal | 0.87 (0.1) | 0.46 | −0.62§ | 0.30 | 0.26 |

| 7. Parietal | 0.71 (0.14) | 0.55†§ | −0.53† | 0.51† | 0.24 |

| 8. Cingulate | 0.99 (0.22) | 0.50†§ | −0.58*§ | −0.01 | −0.07 |

| 9. Hippocampus | 0.15 (0.09) | −0.58* | 0.33 | −0.36 | −0.06 |

| 10. Insula | 1.1 (0.12) | 0.44 | −0.43 | −0.07 | 0.07 |

| 11. Thalamus | 1.7 (0.49) | −0.10 | 0.14 | −0.33 | 0.01 |

Pearson’s correlation coefficients,

P≤0.05, uncorrected;

P≤0.10, uncorrected. Partial correlations,

P<0.05, uncorrected, controlling for mood and pain;

P< 0.10, uncorrected, controlling for mood and pain.

PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SD = standard deviation.

VOI Analyses

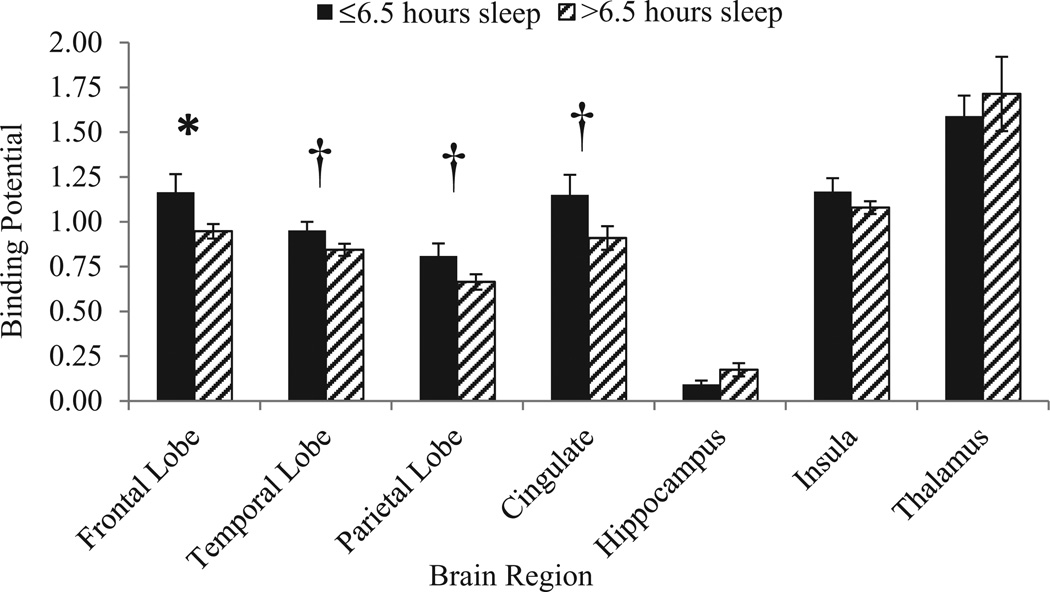

Sleep quality, as defined by the PSQI global score, was significantly associated with BPND in several brain regions including the frontal lobes and hippocampus, while a trend toward significance was also observed in the parietal lobes and cingulate (rs ranged from 0.50 to 0.65). Lower PSQI global scores indicate higher quality sleep; participants that reported poorer quality sleep scores (higher numbers) on the PSQI had higher BP values in general. However, the hippocampus was negatively correlated with global PSQI, suggesting that in the hippocampus, less BP is associated with higher PSQI global scores (poor quality sleep). However, the hippocampus BP was negatively correlated with BP in all other brain areas as well. Because prior studies have demonstrated that short sleep is linked with pain sensitivity, we also evaluated correlations between self-reported sleep duration and BP. Not surprisingly, sleep duration was also significantly and inversely associated with BP in many of the same regions as sleep quality, specifically in frontal areas, temporal areas, and cingulate; a trend toward significance was also found in the parietal lobes (means and correlations presented in Table 2). Less sleep time was associated with greater VOI BP in all areas as expected. The highest BP values were found in the insula and thalamus. Areas of greatest significance include the frontal regions for both sleep quality and duration. Sleep duration was split into a “low” and “high” group using a 6.5-hour cut-off based on our previous work for a graphical representation of these data (Figure 1). Figures 2 and 3 display group differences between those who slept more and less than 6.5 hours per night in the frontal and anterior cingulate cortices. Pain ratings (mean 27.5) were not significantly different by sleep group (P > 0.05), but a trend toward significance was observed between pain and BP in the parietal lobes (P = 0.09).

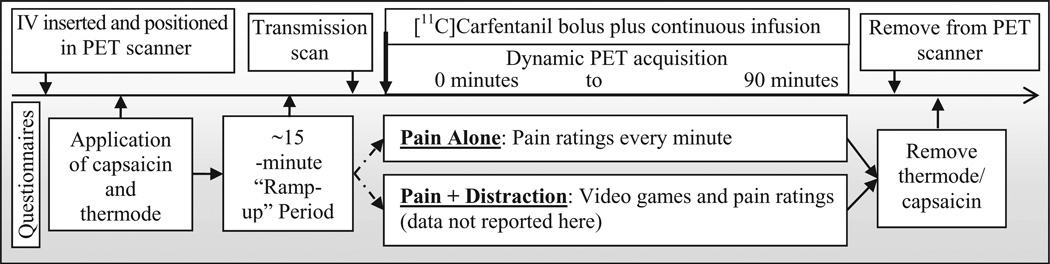

Figure 1.

Session timeline. IV = intravenous; PET = positron emission tomography.

Figure 2.

Binding potential (volume of interest) by sleep duration; error bars represent standard error measurement. *P < 0.05, uncorrected; †P < 0.10, uncorrected.

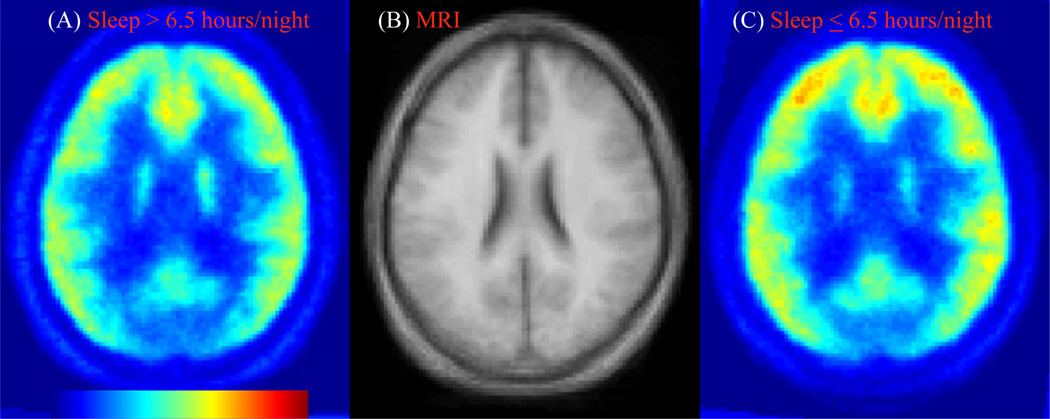

Figure 3.

Transaxial images of binding potential maps of [11C]Carfentanil, averages across subjects who reported more or less than 6.5 hours/night of sleep, panels A and C, respectively, together with the matching slice of a standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (B).

Due to the exploratory nature of this work, we have not corrected for multiple comparisons within the correlations and ANOVA. However, a strict correction for these data may include multiplying the P values by the number of variables included [7] within each assessment. With this correction method in place, none of the correlations or ANOVAs would remain significant.

SPM Analyses

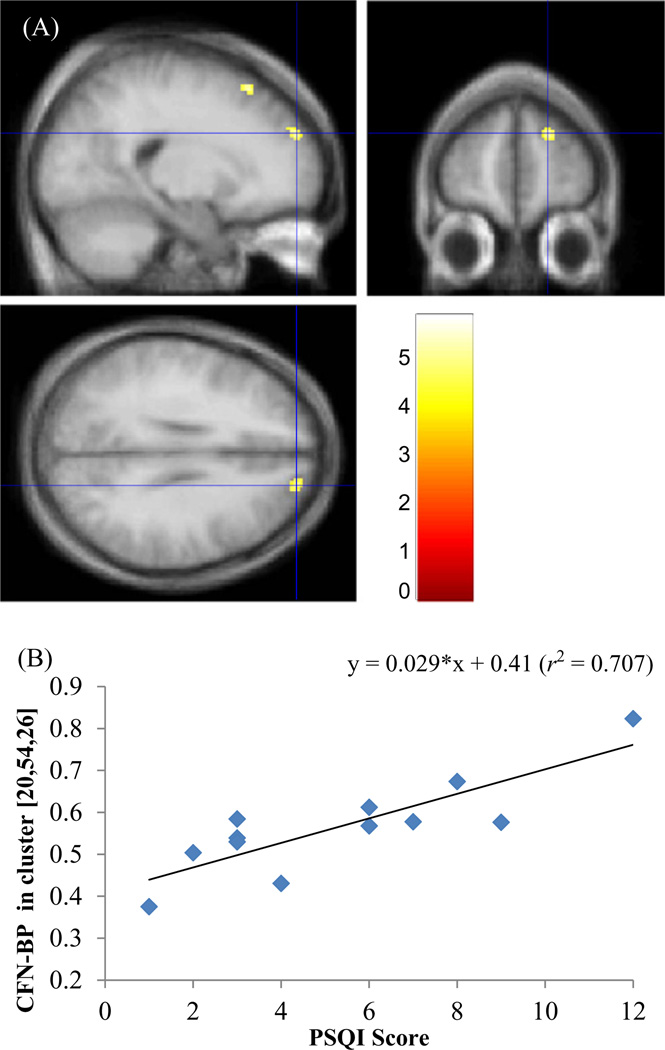

Secondary SPM analyses corroborated our Volumes of Interest (VOI) approach and revealed more refined areas of significance (see Table 3) with the PSQI global score associated with frontal superior areas, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Figure 3), and sleep duration associated with frontal superior and rectal areas, temporal middle and inferior areas, and the anterior cingulate cortex (limbic; Figure 4 and Figure 5). Both sleep quality and duration were related to BP in the same frontal superior (Brodmann area 10) location. When sleep duration was split based on 6.5 hours, the sleep duration groups differed significantly in BP in the frontal middle area (and frontal rectal area similar to the continuous sleep duration measure).

Table 3.

SPM clusters of group differences and correlations of sleep measures to [11C]CFN-BPND

| Cluster Location | Brodmann Area |

Laterality | Cluster Size |

Zmax | Tailarach Coordinates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lobe | Gyrus | K | x | y | z | |||

| Frontal | Superior*† | 10 | Left | 32 | 3.76 | −32 | 62 | −2 |

| Superior* | 6 | Right | 170 | 3.6 | 18 | 24 | 56 | |

| Superior* (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) | 9 | Right | 37 | 3.49 | 20 | 54 | 26 | |

| Rectal*‡ | 11 | Right | 87 | 3.64 | 6 | 28 | −24 | |

| Middle‡ | 10 | Left | 38 | 3.69 | −32 | 62 | 2 | |

| Temporal | Middle† | 39 | Right | 43 | 3.86 | 42 | −64 | 18 |

| Inferior cortex† | 20 | Left | 30 | 3.31 | −60 | −8 | −24 | |

| Limbic | Anterior cingulate cortex† | 32 | Left | 39 | 3.23 | −2 | 46 | −4 |

Cluster associated with:

PSQI continuous measure;

Sleep duration continuous measure;

Sleep duration split using 6.5 hours.

[11C]CFN = [11C]Carfentanil; BPND = binding potential; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SPM = statistical parametric mapping.

Significance level: P≤ 0.001, uncorrected and k≥ 30.

Figure 4.

Clusters of [11C]Carfentanil ([11C]CFN)-binding potential (BPND) to Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) correlation overlaid on orthogonal views of the standard magnetic resonance imaging (A). Blue cross-hair indicates the peak coordinates of one of the clusters [20, 54, 26] in right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). Clusters were color-coded according to t-values as indicated in the color scale. Plot of cluster BPND vs PSQI score for the DLPFC cluster (B).

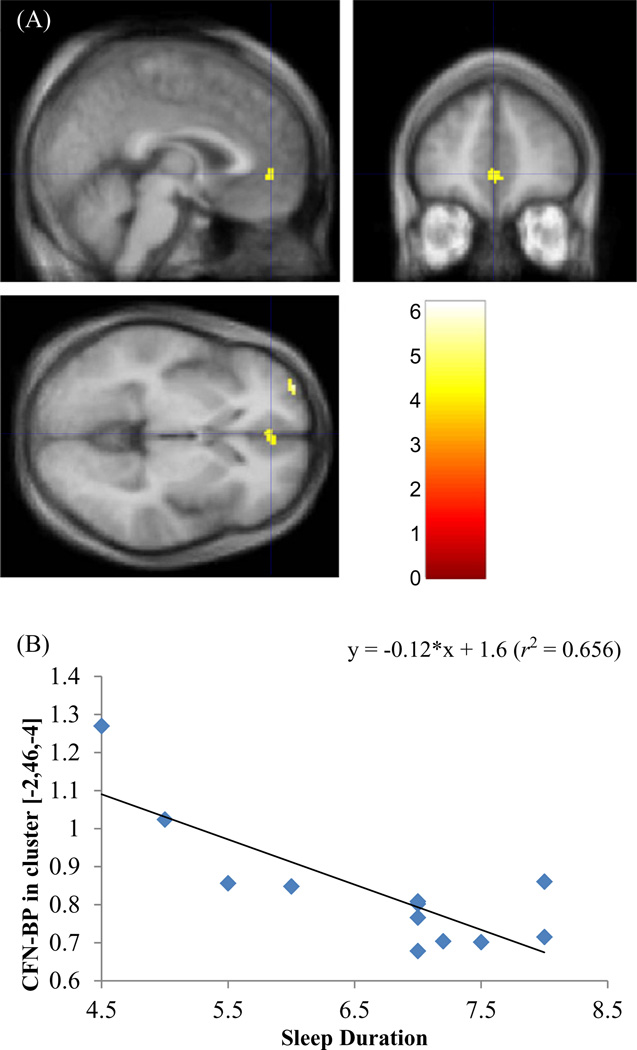

Figure 5.

Clusters of [11C]Carfentanil ([11C]CFN)-binding potential (BPND) to sleep duration (hours/day) correlation overlaid on the standard magnetic resonance imaging (A). Blue cross-hair indicates the peak coordinates of one of the clusters, [−2, 46, −4] in the anterior cingulate. Clusters were color-coded according to t-values as indicated in the color scale. Plot of cluster BPND vs sleep duration for the anterior cingulate (B).

Discussion

These results suggest a potential association between sleep quality/duration and the endogenous opioid system during the application of a noxious stimulus in normal, healthy individuals. Overall, we detected increased BPND in individuals that have poorer habitual sleep quality and those who have a shorter sleep duration. This association suggests that in the context of an ongoing mild-to-moderately painful experimental pain stimulus, endogenous opioid binding to MORs may be reduced among individuals with relatively poorer sleep. Prior neuroimaging studies have found both sleep quality and duration to be associated with metabolic activity and/or blood oxygen level-dependent signal in similar brain regions as we have identified in the present study [38]. To our knowledge, however, these are the first data to examine the potential influence of sleep on cerebral MOR activity in human subjects. These data extend previous findings and provide preliminary evidence that sleep may alter opioid activity in descending pain inhibitory pathways, which are activated during noxious stimulation. The higher [11C]CFN BPND observed in poorer sleep quality and shorter sleep duration participants can be interpreted in different ways. These differences may reflect greater MOR availability due to decreased endogenous opioid occupancy. On the other hand, these results may suggest greater MOR density (perhaps as an adaptation to diminished endogenous opioid activity) compared with better quality/longer sleepers.

Several reports have suggested that sleep engages various descending nociceptive modulatory systems [4,12]. Prior work by our group investigated the possibility that experimental sleep fragmentation impairs pain inhibition. We found that experimental sleep fragmentation diminishes CPM (where a tonic painful stimulus reduces the perception of a phasic noxious stimulus [12]), a phenomenon thought to reflect descending inhibitory capacity. In another indirect study, we recently found that less sleep was associated with diminished benefit from distraction analgesia, which may recruit similar endogenous pain-inhibitory mechanisms [4]. In these studies, sleep was also associated with spontaneous pain [12], greater secondary hyperalgesia, and enhanced skin flare response that may further implicate central involvement [4]. While the current study examined only questionnaire data and did not objectively measure or alter sleep in these healthy participants, substantial variability in habitual sleep patterns was observed, and associations with BP in several brain areas were detected.

The brain’s opioid system is involved in mediating the effects of opioid analgesics and plays a role in the endogenous modulation of noxious stimuli. The most commonly activated brain regions in pain studies include the anterior cingulate, primary and secondary somatosensory cortex, insula, thalamus, and prefrontal cortex [39]. Imaging studies in pain populations including fibromyalgia [40], rheumatoid arthritis [41], and peripheral neuropathic pain [42] have found variation in BP of endogenous opioid peptides. Some of the areas of relationships between BP and sleep in the current analyses are similar to those found altered in functional imaging studies of persistent pain conditions [43–48]. However, opioid receptor BP is reduced in many pain conditions. The areas of activation often differ between healthy individuals undergoing a pain task and patients in chronic pain; unfortunately, the current study is unable to identify such differences. One recent functional MRI (fMRI) study of insomnia found hypoactivation in Brodmann area 9 (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) with activity recovering following treatment for sleep [49]; these results suggest that improving sleep may be one potential strategy for reducing the enhanced pain perceived in sleep-disordered individuals.

Sleep deprivation and imaging studies have primarily examined the impact of recently reduced sleep on brain activity to characterize potential deficits in task performance. Change in global cerebral metabolic rate for glucose have been observed in PET studies under sleep-deprived conditions in brain areas reflecting attentional and higher order cognitive processes ([50] for review). fMRI studies have also found that sleep deprivation alters brain activity in the prefrontal, parietal, and premotor cortices following sleep deprivation in a task-dependent manner. A few studies have examined pain responses in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). For example, OSA patients have altered physiological responses to cold pressor testing observed in multiple brain regions using fMRI [51]. However, no prior studies have examined the relationship between sleep and endogenous opioid activity.

While the current study found no association between verbal reports of pain and CFN BP, or pain and either sleep measure, the pain level reported by participants was somewhat low and may not have been sufficient to detect these associations. In addition, our small sample size may have precluded such findings. Overall, we detect increased BPND within individuals that have poorer habitual sleep quality and those who have a shorter sleep duration. The observation of specific regional alterations in central opioid neurotransmission in relation to sleep, potentially as a consequence of pain, may predispose individuals to be “at risk” for developing chronic pain conditions; however, these data should be considered exploratory, and conclusions should be drawn with caution. In addition, with these receptors being the target of opiate drugs, the current results are consistent with prior studies suggesting less analgesic potential in sleep-deprived/insomnia patients.

Although preliminary, our findings have several possible clinical implications. They provide, for the first time, mechanistic support for the contention that habitual sleep quality and duration may be associated with alterations in endogenous opioid binding, possibly suggesting that those with insufficient sleep are at risk for exacerbation of chronic pain. Altered endogenous opioid activity has been found in a range of chronic pain conditions from tension headache to fibromyalgia [25]. The extent to which altered pain inhibition in these clinical populations is directly related to sleep continuity disturbances remains to be determined. It should be noted that while individuals endorsing poor/less sleep did experience more pain, this difference was not significant, and no relationship between sleep and pain reports were found; however, this may be due in part to the healthy population used, and future studies should examine these relationships in a clinical population in order to determine the relationship between sleep, pain, and endogenous opioid activity. Despite this negative finding, the current results would support efforts to treat sleep disturbance early in the course of a pain condition to determine whether improved sleep has protective properties.

The current study includes several noteworthy limitations. All participants were young, healthy, and pain-free, and while the laboratory-based pain induction procedures have been shown to be clinically relevant [52–54], generalizability of these data (e.g., to acute clinical pain and persistent pain conditions) are limited. In addition, sleep was not manipulated; therefore, causal inferences are not warranted, and the temporal associations between sleep and endogenous opioid function cannot be determined from these data. Another limitation is our relatively small sample size. While it is not uncommon for imaging studies to include fewer participants, this may have led to an inability to detect further potential differences. In addition, sleep was assessed using self-reported sleep quality and duration over the preceding month. Although self-reported sleep parameters such as duration are frequently used and have been validated against more objective measures [55,56], other studies have found these measures to differ [57–60]. These findings should be replicated through use of more objective measures of sleep such as actigraphy or PSG. Of great interest would be the manipulation of sleep and subsequent assessment of the resulting impact on endogenous opioid modulation of pain. Such a study would allow for the inference of a temporal relationship between sleep impairment and endogenous opioid activity. Another limitation is that only uncorrected P values were used in the current study due to the small pilot nature of this work. In addition, the VOI analysis method utilizes brain areas/ volumes that may be too large to detect correlations when correction for multiple comparisons is used. However, as the criterion used for statistically significant activation did not include correction for multiple comparisons or false discovery rates, conclusions regarding the sleep-opioid system connections are preliminary, and conclusions should be drawn with caution and await confirmation from larger independent analyses. An additional limitation of the current study is the absence of a baseline PET scan (i.e., a scan during which no painful stimulation was applied); for this reason, we are unable to determine the extent to which the present sleep–BP associations are influenced by pain. Future studies could benefit from a scan where no pain induction methods were used in order to assess and compare associations between sleep and CFN BP under nonpainful conditions.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide evidence that both self-reported sleep quality and shorter habitual sleep duration is associated with alterations in endogenous opioid systems. These data suggest the possibility that poor sleep impairs endogenous pain-inhibitory function and may increase the perception of pain, supporting a pathophysiological role of sleep disturbance in chronic pain. Future studies should assess a more objective measure of sleep or manipulate sleep to gain a more thorough understanding of the mechanisms involved, and they might interact with descending pain regulatory systems. Future studies would also benefit from examining which variable is causative and pinpoint the direction of sleep effects on endogenous opioids or whether opioids affect one’s ability/duration of sleep. Manipulations involving an opioid antagonist and experimental sleep deprivation or restriction may be a useful next step in elucidating the underlying mechanisms by which sleep and which aspects of sleep shapes the experience of pain and analgesia. This preliminary work supports a promising line of inquiry in understanding how sleep may contribute to the initiation, maintenance, or aggravation of chronic pain syndromes. These psychophysical data suggest one possible mechanistic pathway, by which sleep disturbance impairs opioidergic descending systems implicated in central sensitization models of hyperalgesia and chronic pain. Clinically, it may be noteworthy to investigate whether treatment for sleep will enhance endogenous opioid systems and if this alteration will improve pain perception in patients. Collectively, additional study is warranted to characterize the potentially complex relationships between sleep and endogenous opioid activity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants AT001433, F32 NS06362 and K23 NS070933.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Foo H, Mason P. Brainstem modulation of pain during sleep and waking. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7(2):145–154. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson CJ, Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Sleep and GABA levels in the oral part of rat pontine reticular formation are decreased by local and systemic administration of morphine. Neuroscience. 2007;144(1):375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittig RM, Zorick FJ, Blumer D, Heilbronn M, Roth T. Disturbed sleep in patients complaining of chronic pain. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982;170(7):429–431. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell CM, Bounds SC, Simango MB, et al. Self-reported sleep duration associated with distraction analgesia, hyperemia, and secondary hyperalgesia in the heat-capsaicin nociceptive model. Eur J Pain. 2011;15(6):561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta A, Silman AJ, Ray D, et al. The role of psychosocial factors in predicting the onset of chronic widespread pain: Results from a prospective population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(4):666–671. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaila-Kangas L, Kivimaki M, Harma M, et al. Sleep disturbances as predictors of hospitalization for back disorders-a 28-year follow-up of industrial employees. Spine. 2006;31(1):51–56. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000193902.45315.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikkelsson M, Sourander A, Salminen JJ, Kautiainen H, Piha J. Widespread pain neck pain in schoolchildren. A prospective one-year follow-up study. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88(10):1119–1124. doi: 10.1080/08035259950168199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siivola SM, Levoska S, Latvala K, et al. Predictive factors for neck and shoulder pain: A longitudinal study in young adults. Spine. 2004;29(15):1662–1669. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000133644.29390.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castillo RC, MacKenzie EJ, Wegener ST, Bosse MJ. Prevalence of chronic pain seven years following limb threatening lower extremity trauma. Pain. 2006;124(3):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MT, Klick B, Kozachik S, et al. Sleep onset insomnia symptoms during hospitalization for major burn injury predict chronic pain. Pain. 2008;138(3):497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards RR, Almeida DM, Klick B, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT. Duration of sleep contributes to next-day pain report in the general population. Pain. 2008;137(1):202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MT, Edwards RR, McCann UD, Haythornthwaite JA. The effects of sleep deprivation on pain inhibition and spontaneous pain in women. Sleep. 2007;30(4):494–505. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fadda P, Martellotta MC, De Montis MG, Gessa GL, Fratta W. Dopamine D1 and opioid receptor binding changes in the limbic system of sleep deprived rats. Neurochem Int. 1992;20(suppl):153S–156S. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(92)90229-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Przewlocka B, Mogilnicka E, Lason W, van Luijtelaar EL, Coenen AM. Deprivation of REM sleep in the rat and the opioid peptides beta-endorphin and dynorphin. Neurosci Lett. 1986;70(1):138–142. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fadda P, Tortorella A, Fratta W. Sleep deprivation decreases mu and delta opioid receptor binding in the rat limbic system. Neurosci Lett. 1991;129(2):315–317. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90489-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ukponmwan OE, Rupreht J, Dzoljic MR. REM sleep deprivation decreases the antinociceptive property of enkephalinase-inhibition, morphine and cold-water-swim. Gen Pharmacol. 1984;15:255–258. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(84)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nascimento DC, Andersen ML, Hipolide DC, Nobrega JN, Tufik S. Pain hypersensitivity induced by paradoxical sleep deprivation is not due to altered binding to brain mu-opioid receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2007;178(2):216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frecska E, Perenyi A, Arato M. Blunted prolactin response to fentanyl in depression. Normalizing effect of partial sleep deprivation. Psychiatry Res. 2003;118(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zgierska A, Brown RT, Zuelsdorff M, et al. Sleep and daytime sleepiness problems among patients with chronic noncancerous pain receiving long-term opioid therapy: A cross-sectional study. J Opioid Manag. 2007;3(6):317–327. doi: 10.5055/jom.2007.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raymond I, Nielsen TA, Lavigne G, Manzini C, Choiniere M. Quality of sleep and its daily relationship to pain intensity in hospitalized adult burn patients. Pain. 2001;92(3):381–388. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raymond I, Ancoli-Israel S, Choiniere M. Sleep disturbances, pain and analgesia in adults hospitalized for burn injuries. Sleep Med. 2004;5(6):551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinmiller CL, Roehrs TA, Harris E, et al. Differential effect of codeine on thermal nociceptive sensitivity in sleepy versus nonsleepy healthy subjects. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(3):277–283. doi: 10.1037/a0018899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villanueva L, Le Bars D. The activation of bulbo-spinal controls by peripheral nociceptive inputs: Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls. [Review] [96 refs] Biol Res. 1995;28(1):113–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards RR, Grace E, Peterson S, et al. Sleep continuity and architecture: Associations with pain-inhibitory processes in patients with temporomandibular joint disorder. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(10):1043–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(4):463–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell CM, Quartana PJ, Buenaver LF, Haythornthwaite JA, Edwards RR. Changes in situation-specific pain catastrophizing precede changes in pain report during capsaicin pain: A cross-lagged panel analysis among healthy, pain-free participants. J Pain. 2010;11(9):876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson WS, Sheth RN, Bencherif B, Frost JJ, Campbell JN. Naloxone increases pain induced by topical capsaicin in healthy human volunteers. Pain. 2002;99(1–2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bencherif B, Fuchs PN, Sheth R, et al. Pain activation of human supraspinal opioid pathways as demonstrated by [11C]-carfentanil and positron emission tomography (PET) Pain. 2002;99(3):589–598. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00266-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wager TD, Scott DJ, Zubieta JK. Placebo effects on human mu-opioid activity during pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(26):11056–11061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702413104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahmim A, Cheng JC, Blinder S, Camborde ML, Sossi V. Statistical dynamic image reconstruction in state-of-the-art high-resolution PET. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50(20):4887–4912. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/20/010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammers A, Allom R, Koepp MJ, et al. Three-dimensional maximum probability atlas of the human brain, with particular reference to the temporal lobe. Hum Brain Mapp. 2003;19(4):224–247. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazziotta JC, Toga AW, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J. A probabilistic atlas of the human brain: Theory, rationale for its development. The International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) Neuroimage. 1995;2(2):89–101. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashburner J, Friston KJ, et al. High-dimensional image warping. In: Frackowiak RSJ, Friston C, Frith C, editors. Human Brain function. 2nd edition. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 673–694. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashburner J, Friston KJ, et al. Rigid body registration. In: Frackowiak RSJ, Friston C, Frith C, editors. Human Brain function. 2nd edition. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 635–654. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, et al. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16(5):834–840. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endres CJ, Bencherif B, Hilton J, Madar I, Frost JJ. Quantification of brain mu-opioid receptors with [11C]carfentanil: Reference-tissue methods. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30(2):177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nofzinger EA. Functional neuroimaging of sleep disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(32):3417–3429. doi: 10.2174/138161208786549371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tracey I. Neuroimaging of pain mechanisms. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2007;1(2):109–116. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282efc58b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris RE, Clauw DJ, Scott DJ, et al. Decreased central mu-opioid receptor availability in fibromyalgia. J Neurosci. 2007;27(37):10000–10006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2849-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones AK, Cunningham VJ, Ha-Kawa S, et al. Changes in central opioid receptor binding in relation to inflammation and pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33(10):909–916. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.10.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maarrawi J, Peyron R, Mertens P, et al. Differential brain opioid receptor availability in central and peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127(1–2):183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baciu MV, Bonaz BL, Papillon E, et al. Central processing of rectal pain: A functional MR imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(10):1920–1924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silverman DH, Munakata JA, Ennes H, et al. Regional cerebral activity in normal and pathological perception of visceral pain. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kern M, Hofmann C, Hyde J, Shaker R. Characterization of the cerebral cortical representation of heartburn in GERD patients. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286(1):G174–G181. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00184.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kern MK, Birn RM, Jaradeh S, et al. Identification and characterization of cerebral cortical response to esophageal mucosal acid exposure and distention. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(6):1353–1362. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mongini F, Castellano G, Deregibus A, Rota E, Bosco A. Cortical involvement during the description of head pain. J Headache Pain. 2006;7(5):351–354. doi: 10.1007/s10194-006-0323-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosen SD, Paulesu E, Nihoyannopoulos P, et al. Silent ischemia as a central problem: Regional brain activation compared in silent and painful myocardial ischemia. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(11):939–949. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-11-199606010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altena E, Van Der Werf YD, Sanz-Arigita EJ, et al. Prefrontal hypoactivation and recovery in insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31(9):1271–1276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dang-Vu TT, Desseilles M, Petit D, et al. Neuroimaging in sleep medicine. Sleep Med. 2007;8(4):349–372. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harper RM, Macey PM, Henderson LA, et al. fMRI responses to cold pressor challenges in control and obstructive sleep apnea subjects. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94(4):1583–1595. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00881.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fillingim RB, Lautenbacher S. The importance of quantitative sensory testing in the clinical setting. In: Lautenbacher S, Fillingim RB, editors. Pathophysiology of Pain Perception. New York: Kluwer Academic Plenum Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morris VH, Cruwys SC, Kidd BL. Characterisation of capsaicin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia as a marker for altered nociceptive processing in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 1997;71(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)03361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris V, Cruwys S, Kidd B. Increased capsaicin-induced secondary hyperalgesia as a marker of abnormal sensory activity in patients with fibromyalgia. Neurosci Lett. 1998;250(3):205–207. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lockley SW, Skene DJ, Arendt J. Comparison between subjective and actigraphic measurement of sleep and sleep rhythms. J Sleep Res. 1999;8(3):175–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Usui A, Ishizuka Y, Obinata I, et al. Validity of sleep log compared with actigraphic sleep-wake state II. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;53(2):183–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.1999.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Den Berg JF, Van Rooij FJ, Vos H, et al. Disagreement between subjective and actigraphic measures of sleep duration in a population-based study of elderly persons. J Sleep Res. 2008;17(3):295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, et al. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/ polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(6):563–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feige B, Al-Shajlawi A, Nissen C, et al. Does REM sleep contribute to subjective wake time in primary insomnia? A comparison of polysomnographic and subjective sleep in 100 patients. J Sleep Res. 2008;17(2):180–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vanable PA, Aikens JE, Tadimeti L, Caruana-Montaldo B, Mendelson WB. Sleep latency and duration estimates among sleep disorder patients: Variability as a function of sleep disorder diagnosis, sleep history, and psychological characteristics. Sleep. 2000;23(1):71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]