Abstract

Although an attentional bias for threat-relevant cues has been theorized in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), to date empirical demonstration of this phenomenon has been at best inconsistent. Furthermore, the nature of this bias in PTSD has not been clearly delineated. In the present study, veterans with PTSD (n = 20), trauma exposed veterans without PTSD (n = 16), and healthy nonveteran controls (n = 22) completed an emotional attentional blink task that measures the extent to which emotional stimuli capture and hold attention. Participants searched for a target embedded within a series of rapidly presented images. Critically, a combat-related, disgust, positive, or neutral distracter image appeared 200 ms, 400 ms, 600 ms, or 800 ms before the target. Impaired target detection was observed among veterans with PTSD relative to both veterans without PTSD and healthy nonveteran controls following only combat-related threat distracters when presented 200 ms, 400 ms or 600 ms prior to the target, indicating increased attentional capture by cues of war and difficulty disengaging from such cues for an extended period. Veterans without PTSD and healthy nonveteran controls did not significantly differ from each other in target detection accuracy following combat-related threat distracters. These data support the presence of an attentional bias towards combat related stimuli in PTSD that should be a focus of treatment efforts.

Keywords: PTSD, Threat, Attention, Disengagement

For several years, the Unites States (US) military has been engaged in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan and there is growing concern that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) awaits many US military personnel (Smith et al., 2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric condition marked by a failure to recover from initial symptomatic reactions to traumatic event exposure. Symptoms of PTSD include re-experiencing the traumatic event (e.g., flashbacks, nightmares), avoidance and numbing (e.g., restriction of affect, avoidance of traumatic event cues), and hyperarousal (e.g., exaggerated startle response, difficulty sleeping; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). It has been proposed that the failure to recover from initial symptomatic reactions to trauma in PTSD may be explained, in part, by a selective attentional bias that automatically favors trauma-relevant cues (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Although the mechanisms underlying this bias remains unclear, heightened fear responding when exposed to a traumatic event may prime threatening representations to become readily activated by trauma-relevant cues (McNally, 2006). Preferential attentional processing of threat may then reinforce preoccupation with the trauma and contribute to the repeated accessing of trauma-related memories observed among veterans with PTSD.

The vast majority of the evidence supporting the role of an attentional bias for threat among veterans with PTSD comes from studies employing the emotional Stroop color-naming task (Stroop, 1935). Slower response latencies in color naming threat words compared to color-naming neutral words is thought to arise from difficulty inhibiting the strong associative connections of threat words, and is often interpreted as reflecting an attention bias for threat (Williams, Mathews, & MacLeod, 1996). Research employing the emotional Stroop task has shown that veterans with PTSD take longer to name the color in which trauma-related words are printed than do non-anxious controls (McNally, English, & Lipke, 1993), suggesting preferential attentional processing of threatening information. However, a recent meta-analysis of emotional Stroop studies found that PTSD patients and trauma exposed control participants do not differ from each other in response latencies for color naming PTSD-relevant words (Cisler et al., 2011). Furthermore, PTSD-relevant words and generally threatening words impaired performance to a similar degree relative to neutral words among those with PTSD. Although these findings cast doubt on the view that an attentional bias for combat-related threat is uniquely characteristic of veterans with PTSD, methodological limitations of the emotional Stroop task prevent definitive inferences. Indeed, some authors have questioned whether the emotional Stroop captures individual differences in selective attention as opposed to other generic sources of slowing following exposure to negative emotional material (Algom, Chajut, & Lev, 2004).

The dot probe task is also often-used to examine selective attention to threat in PTSD (Bryant & Harvey, 1997; Fani et al., 2012). A facilitated response to probes that appear at the same location of threat information in comparison with responses to probes at the opposite location of threat information is interpreted as vigilance for threat in PTSD. However, research has shown that the findings of studies employing the dot probe paradigm can be ambiguous evidence for the vigilance to threat hypothesis in PTSD (Koster, Crombez, Verschuere, & De Houwer, 2004). That is, findings from such studies can also be interpreted as a difficulty to disengage from threat. Although recent research has begun to employ eye-tracking technology (Beevers, Lee, Wells, Ellis, & Telch, 2011; Felmingham, Rennie, Manor, & Bryant, 2011) and other emotion-attention paradigms in PTSD or individuals exposed to trauma (Pineles, Shipherd, Welch, & Yovel, 2007; Bar-Haim et al., 2010), demonstration of a consistent and unique attentional bias involving facilitated detection of threat stimuli in PTSD has remained elusive.

The emotional attentional blink paradigm (a.k.a, the “emotional blink of attention”: Most, Chun, Widders, & Zald, 2005), may provide a particularly useful tool for probing attentional biases in PTSD. Indeed, recent research has shown that the task may have utility in differentiating patients with other anxiety disorders from controls in the extent to which emotional distractors capture attention (Olatunji, Ciesielski, Armstrong, & Zald, 2011; Olatunji, Ciesielski, & Zald, 2011). On each trial of this task, participants view a rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) of stimuli and attempt to detect a rotated target image, which occurs at varying intervals (e.g., 200 ms, Lag 2 vs. 800 ms, Lag 8) downstream from an emotional distracter. The attentional blink paradigm taps an exogenous orienting response through which a stimulus automatically captures attention to a specific object (Chun & Potter, 1995). This capture phenomenon is so great that no other stimuli are consciously processed for a period of time after capture. Whereas probe-detection, emotional Stroop, and visual search tasks attempt to gauge similar effects through delayed reaction times to competing stimuli, the attentional blink effect is can be measured in terms of the mere awareness of other stimuli. Awareness of a stimulus is of course intimately linked to attention (e.g., Most, Scholl, Clifford, & Simons, 2005), and can be objectively measured by gauging one's ability to detect a target in the RSVP. Further, the varying “lags” between the distracter image and the rotated target image in the RSVP allow insight into the time course of attentional effects. At the shortest interval following the distracter (200 ms, Lag 2), impaired target detection reflects the involuntary capture of attention, whereas in subsequent time intervals (400 ms, Lag 4 through 800 ms, Lag, 8), the persistence of impaired target detection increasingly reflects difficulty recovering from attentional capture (i.e., disengagement).

Given the importance of attentional biases to current theories of PTSD, we employed the emotional attentional blink paradigm to more clearly delineate the nature of attentional biases for threat among veterans with PTSD. Although a verbal attentional blink paradigm has been employed with an analogue sample of students endorsing PTSD-like symptoms (Amir et al., 2009), the findings were inconclusive. An image-based version of the attentional blink paradigm may yield more robust findings for which more definitive inferences can be made. It was predicted in the present study that relative to combat-exposed veterans without PTSD and nonveteran healthy controls, veterans with PTSD would show enhanced attentional capture to combat images as reflected in a significant decrement in target detection following combat images, but not other distracters, at the shortest delay. Consistent with reported deficits in attentional disengagement in PTSD (Pineles et al., 2007), it was also predicted that veterans with PTSD would continue to be less accurate than both control groups following exposure to combat images at longer delays. Lastly, it was predicted that attentional capture at short and long delays would be significantly correlated with PTSD symptom severity.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 20 veterans who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, 16 veterans endorsing criterion A1 of the DSM-IV diagnosis for PTSD (The person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others) that did not meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD, and 22 non-veteran controls (NCC) with no current diagnoses.1 Participants were recruited though community advertisements and referrals from various veteran services. Veteran participants were post-deployment and those meeting criteria did so because of a combat-related event (as opposed to car accident, etc.). Diagnoses were based upon the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998). The MINI is a structured clinical interview used to assess 17 Axis I disorders. The MINI was administered by trained master- and doctoral-level clinicians that were supervised by a trained clinical psychologist. Exclusionary criteria for all participants included a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, intellectual disability, psychosis, ADHD, developmental disorders, mental retardation, or current or past neurological diseases, and traumatic brain injury. Consistent with known patterns of PTSD comorbidity (e.g., Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995), the majority of veterans with PTSD met diagnostic criteria for at least one additional Axis 1 diagnosis (81%), including 71% with another anxiety disorder and 24% with a mood disorder. Common comorbid anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder and agoraphobia. Common comorbid mood disorders include major depressive disorder and dysthymia.

Symptom Assessment

The Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) is a 17-item measure of PTSD symptoms severity over the past month. The PCL-C had excellent internal consistency in the present study (α = .97).

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory - Trait (STAI-T; Spielberger et al., 1983) is a 20-item measure of one's proneness towards experiencing anxiety and distress (trait anxiety). The STAI-T had good internal consistency in the present study (α = .96).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988) is a 21-item measure of depressive symptoms. The BDI had good internal consistency in the present study (α = .95).

Rapid Serial Visual Presentation (RSVP) Task Materials

“Filler” images (not target or distracter) included 256 upright landscapes/architectural images. Target images consisted of 96 landscape/architectural photos presented in two rotations: 90° to the left and 90° to the right. Distracter images consisted of four categories, combat-related threat (e.g., soldiers firing guns), disgust (e.g., feces), pleasant (e.g., baby animals), and neutral (e.g., household objects), with 17 images per category, presented twice. Disgust, pleasant, and neutral images were partially drawn from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1999) and were supplemented with similar images found from publicly available sources. War images were mainly obtained from publicly available sources.2 Stimuli were presented through E-Prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.) run on a Dell computer.

Procedure

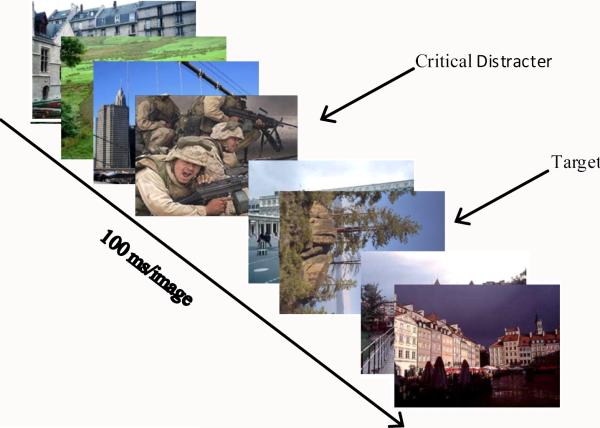

All participants completed written informed consent approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board. Participants completed the diagnostic interview, and were then seated at a computer where they completed the symptom measures, followed by the emotional attentional blink task. The RSVP task consisted of a series of 17 images that were presented on the screen for 100 ms in rapid succession (see Figure 1). On 89% of trials, one of these images (the “target”) was rotated 90° to the left or the right. The participant's task was to indicate whether or not a rotated image was present (detection), and if so, which direction it was rotated (accuracy). Here, change performance on the task would be 50%. Although 100 ms would be considered supraliminal, participants did typically report “seeing” the critical distractor. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Olatunji et al., 2011), analyses for accuracy, rather than detection, are presented as they reflect more precise performance on the RSVP. A “distracter” image was placed at varying intervals prior to the target. Distracter images appeared in the stream at positions 2, 4, 6, or 8, with the target appearing downstream at varying “lags” [200 ms (lag 2), 400 ms (lag 4), 600 ms (lag 6), or 800 ms (lag 8)]. Position and lag were equally distributed for each distracter category. Participants completed 6 blocks with 36 trials per block. Each distracter type was presented 54 times with 6 trials per distracter type containing no target (216 total target trials, 24 total no target trials). Prior the task, participants performed 16 practice trials with 4 of the 16 trials containing no rotated target image, 6 trials with the target image rotated to the right, and 6 trials with the target image rotated to the left. Distracters were neutral for the practice trials.

Figure 1.

The trial structure for the emotional attentional-blink paradigm (Lag 2 depicted).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants were well-matched on several demographic characteristics with no significant differences between the three groups on gender, age, ethnicity, and marital status (see Table 1). The three groups did significantly differ in income [F (2, 55) = 3.73, p < .05, partial η2 = .12] and years of education [F (2, 55) = 19.54, p < .001, partial η2 = .42]. As expected, healthy nonveteran controls had significantly higher incomes than veterans with PTSD (p < .02). However, income level for veterans without PTSD did not significantly differ from healthy nonveteran controls and veterans with PTSD. Similarly, healthy nonveteran controls were more educated than veterans with and without PTSD (ps < .001). However, years of education did not significantly differ between veterans with PTSD and those without PTSD. Table 2 shows that, as expected, veterans with PTSD reported significantly more symptoms of PTSD than veterans without PTSD. Table 2 also shows that veterans with PTSD reported significantly more trait anxiety and depression than veterans without PTSD and healthy nonveteran controls. However, veterans without PTSD and healthy nonveteran controls did not significantly differ from each other in trait anxiety and depression.

Table 1.

Demographic information by diagnostic group

| Veterans + PTSD | Veterans - PTSD | Nonveteran NCC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20 | 16 | 22 |

| % male | 90 | 94 | 91 |

| Age (SD) | 33.55 (6.78) | 34.69 (7.68) | 32.86 (6.35) |

| % Caucasian | 85 | 88 | 77 |

| % Married | 40 | 31 | 50 |

| Years of Education | 14.10 | 13.62 | 17.04 |

| Average Income | $34,500 | $48,750 | $55,700 |

Note: + PTSD = with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; - PTSD = Without Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; NCC = Nonclinical control.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviation by group on symptom measures

| Symptoms | Veterans + PTSD M (SD) | Veterans - PTSD M (SD) | Nonveteran NCC M (SD) | F | partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-C | 60.90 (13.28)a | 25.18 (6.12)b | -- | 98.26 | .74 |

| STAI - T | 53.60 (10.98)a | 33.06 (8.29)b | 31.54 (8.65)b | 33.86 | .55 |

| BDI | 23.35 (10.46)a | 4.25(4.79)b | 3.13 (5.32)b | 46.58 | .63 |

Note: + PTSD = with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; - PTSD = Without Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; NCC = Nonclinical control; -- = did not complete; all F-values significant at p < .001; Values with difference subscripts are significantly different from each other; PCL-C = Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Version; STAI —T = State Trait Anxiety Inventory - Trait Subscale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory.

RSVP Task Accuracy

Means and standard deviations of percent accuracy on the RSVP by Group, Lag, and Distracter are presented in Table 3. A 3 (Group; Veterans with PTSD, Veterans without PTSD, nonveteran NCC) X 4 (Lag; 2, 4, 6, 8) X 4 (Distracter; combat-related threat, disgust, happy, neutral) mixed model Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on percent accuracy revealed a significant main effect of Group [F (1, 2) = 3.20, p < .05, partial η2 = .10], reflecting lower accuracy among veterans with PTSD compared to nonveteran healthy controls but not veterans without PTSD, Lag [F (3, 165) = 57.84, p < .001, partial η2 = .51], reflecting higher accuracy with increase in Lag, and Distracter [F (3, 165) = 33.46, p < .001, partial η2 = .38], reflecting differential performance across emotional stimulus categories. These main effects were qualified by significant Group X Distracter [F (6, 165) = 5.79, p < .001, partial η2 = .17] and Lag X Distracter [F (9, 495) = 21.28, p < .001, partial η2 = .28] interactions. The predicted Group X Lag X Distracter interaction was also significant [F (18, 495) = 1.76, p < .03, partial η2 = .06].

Table 3.

Rapid serial visual presentation task means and standard deviations of accuracy percentage by emotion, lag, and group

| Veterans with PTSD |

Veterans without PTSD |

Non-Veteran Controls |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lag | Combat M (SD) |

Disgust M (SD) |

Happy M (SD) |

Neutral M (SD) |

Combat M (SD) |

Disgust M (SD) |

Happy M (SD) |

Neutral M (SD) |

Combat M (SD) |

Disgust M (SD) |

Happy M (SD) |

Neutral M (SD) |

| 56.75 | 47.62 | 68.65 | 76.19 | 72.92 | (46.88) | 77.60 | 72.40 | 80.30 | 51.89 | 82.95 | 76.52 | |

| 2 | (26.70) | (17.51) | (21.07) | (13.77) | (17.87) | 10.92 | (16.02) | (12.44) | (10.14) | (17.62) | (16.36) | (7.56) |

| 63.49 | 73.81 | 76.59 | 80.95 | 81.77 | 72.40 | 84.38 | 85.94 | 81.44 | 77.65 | 83.71 | 84.47 | |

| 4 | (19.98) | (17.73) | (16.80) | (15.17) | (13.68) | (13.51) | (14.23) | (11.27) | (14.53) | (14.86) | (15.74) | (9.38) |

| 77.78 | 82.14 | 76.59 | 83.33 | 88.02 | 86.98 | 83.85 | 86.46 | 89.39 | 85.98 | 75.76 | 87.88 | |

| 6 | (15.44) | (15.20) | (14.34) | (12.08) | (7.43) | (13.25) | (8.86) | (13.90) | (8.60) | (14.18) | (12.84) | (13.04) |

| 78.97 | 71.03 | 75.40 | 85.32 | 86.98 | 76.04 | 83.33 | 82.81 | 83.71 | 79.92 | 82.20 | 84.85 | |

| 8 | (17.00) | (17.80) | (15.25) | (14.17) | (9.11) | (8.54) | (10.09) | (10.31) | (11.06) | (13.03) | (12.41) | (15.35) |

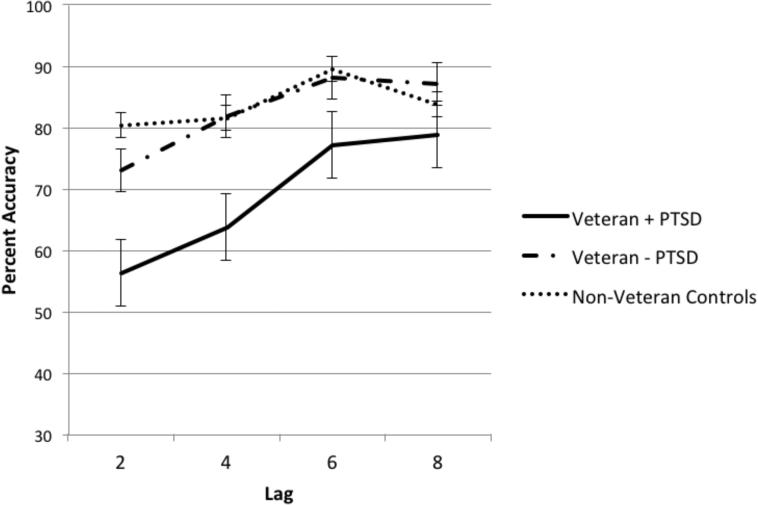

To examine the Group X Lag X Distracter interaction, a 3 (Group) X 4 (Lag) mixed model ANOVA was conducted on accuracy for each Distracter type. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of Group [F (2, 55) = 9.25, p < .001, partial η2 = .25] and Lag [F (3, 165) = 21.46, p < .001, partial η2 = .28] that was qualified by a significant Group X Lag interaction [F (6, 165) = 2.88, p < .02, partial η2 = .10] for combat-related threat distracters only. As depicted in Figure 2, multivariate examination of the significant Group X Lag interaction for combat-related threat distracters revealed significant group differences in accuracy for detection at Lag 2 [F (2, 55) = 8.14, p < .001, partial η2 = .23], Lag 4 [F (2. 55 = 7.53, p < .001, partial η2 = .22], and Lag 6 [F (2, 55) = 7.20, p < .002, partial η2 = .21], but not Lag 8 [F (2, 55) = 1.79, p = .179, partial η2 = .06]. 3 At Lag 2, Lag 4, and Lag 6, veterans with PTSD were less accurate in detecting the target following combat-related threat distracters than veterans without PTSD (ps < .02) and nonveteran healthy controls (ps < .01). By contrast, veterans without PTSD and nonveteran healthy controls did not significantly differ in this regard (ps > .25). No significant group differences were found at Lag 8, consistent with past studies indicating that emotion-induced attentional blinks are typically resolved by 800 ms (Most, Chun, Widders, & Zald, 2005). Critically, the Group effects were specific to combat distracters, as there were no Group effects or Group X Lag interactions for disgust, neutral or happy distracters (all p > .05).4 That is, to the extent that these stimuli caused an attentional blink, the blink was similar across groups. Indeed, a large attentional blink was seen for all subjects following disgust distracters (reflected in a robust main effect of Lag [F (3, 165) = 92.81, p < .001, partial η2 = .63], but the magnitude of the response was not influenced by either diagnosis or history of trauma exposure. Thus, the enhanced attentional blink displayed by PTSD patients was unique to the combat distracters.

Figure 2.

Percent detection accuracy by group and lag for combat-related threat distracters. Bars represent standard error.

Discussion

This investigation examined the extent to which threat-relevant cues uniquely capture attention among veterans with PTSD on an emotional attentional blink RSVP task. The present findings showed that while group differences in detection accuracy as a function of lag did not significantly differ when disgust, happy, and neutral distracters were presented, significant group differences in detection accuracy as a function of lag did emerge when combat images were employed as distracters. Examination of this pattern of findings revealed that at Lag 2, Lag 4, and Lag 6, but not Lag 8, veterans with PTSD were less accurate in detecting the target following combat-related threat distracters than Veterans without PTSD and nonveteran healthy controls. Importantly, however, combat-exposed veterans without PTSD and nonveteran healthy controls did not significantly differ in detection accuracy when combat images were employed as distracters. These findings suggest that heightened attentional capture by trauma-relevant threat is uniquely characteristic of veterans with PTSD.

The present findings are consistent with cognitive theories that implicate preferential processing of trauma cues in PTSD (Brewin & Holmes, 2003; Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Moreover, they provide insight into the nature of the attentional bias in PTSD. That veterans with PTSD showed impairments at the earliest lag (Lag 2), indicates a proneness to attentional capture by trauma relevant cues. This preferential processing of trauma-relevant cues among veterans with PTSD may reflect both a heightened vigilance for trauma-relevant cues as well as an excessive orienting response when such stimuli are perceived. The phenomena of attentional capture to emotionally-valenced stimuli is thought to distinctly reflect automatic, bottom-up processing as opposed to strategic top-down stages of information processing (Carretie, Hinojosa, Martin-Loeches, Mercado, & Tapia, 2004). Such automatic direction of attention to exogenous stimuli typically reflects processing that is capacity free and occurs without intent, control, or awareness (Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). Importantly, the veterans with PTSD did not show a generalized proneness to attentional capture, as they showed normal levels of performance when exposed to neutral, positive and disgust related stimuli. Thus, they do not appear to have a generalized heightened vigilance for or orienting to emotionally-valenced stimuli, or even negatively-valenced stimuli. Rather, they appear to show preferential processing of trauma-relevant stimuli.

In addition to the heightened attentional capture demonstrated here, recent research has suggested that PTSD is associated with a reduced capacity for top-down attentional control of bottom-up, stimulus-driven effects (Johnsen, Kanagaratnam, & Asbjørnsen, 2011). Such a top-down’ regulatory ability (Posner & Rothbart, 2000) are necessary to counter the ‘bottom-up’ influence of emotionally salient stimuli that compete for attention (Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos, & Calvo, 2007), and these executive control deficits have been postulated to underlie the experience of intrusive emotional memories (Levy & Anderson, 2008; Vasterling, Brailey, Constans, Sutker, 1998). Such difficulties could lead to problems in attentional disengagement in PTSD, consistent with the work of Pineles and colleagues (2007), who reported evidence of excessive interference caused by threat words in a visual search task with a lexical decision component. Preexisting deficits in attention control among veterans with PTSD, relative to veterans without PTSD, may partially explain the unique attentional capture by combat related images observed in the present study. Subsequent to combat-related trauma, deficits in attention control may make it difficult for veterans that go on to develop PTSD to efficiently regulate the recollection and emotional costs of the trauma. This view is consistent with prior research showing that individuals with higher levels of attention control are better able to attenuate distress associated with trauma cues compared to those with low levels of attention control (Bardeen & Read, 2010). However, these effects are likely to be bi-directional. Indeed, the findings of Bardeen and Read also suggest that heightened trauma-related distress negatively affects one's ability to efficiently employ attention control. Recent research has also shown that heightened emotional responding among those with PTSD, relative to those exposed to trauma, may lead to the heightened interference in the recruitment of regions implicated in top-down attentional control (Blair et al., 2012). These findings suggest that heightened emotional responding to trauma cues among veterans with PTSD, relative to those without PTSD, may lead to difficulties in attentional control and the subsequent interference of trauma cues.

The present data provide some support for an inability to disengage orienting to threat-relevant cues among veterans with PTSD, as these individuals continued to show impairment in target detection for up to 600 ms after exposure to the trauma-relevant stimuli. As one moves further out in time from the attention capturing stimulus, top-down strategic processing should allow a refocusing of attention (Dux & Marois, 2009). The prolonged blink displayed by veterans with PTSD suggests the presence of both heightened automatic processing of threat and deficient strategic control of attention. Two caveats are warranted, however, regarding the issue of disengagement. First, the absence of any group differences at Lag 8 suggests that strategic processing ability, even among veterans with PTSD, is intact after 800 msec. This is consistent with prior research showing that attentional capture by emotional stimuli on the attention blink task is no longer evident after 800 ms. in the vast majority of subjects (Most et al., 2005; Smith, Most, Newsome, & Zald, 2006). Second, although strategic processes become more prominent the further one moves in time from an attention capturing stimulus, because the veterans with PTSD show such a large attentional capture (as evidenced by their poor performance at lag 2), it is not possible to specifically determine whether their poor performance at the later lags reflects a unique problem with disengagement because a greater orienting response could potentially cause these effects in the absence of a specific problem in disengagement. Indeed, the rate of recovery (as reflected in the increased target accuracy across lags), suggests that the PTSD patients show a normal rate of recovery, but have such a large orienting response that it takes several hundred ms to recover. Nevertheless, at a minimum, the veterans with PTSD appear unable to overcome their heightened orienting response leading to deficits continuing after the trauma related stimulus has past.

One factor that may contribute to the robustness of the present effects is the use of salient combat related pictures for stimuli, in contrast to many studies that have relied on verbal stimuli or stimuli that are not specific to the trauma. For instance, in a study using a verbal attentional blink paradigm in an analogue sample of college undergraduates who endorsed PTSD-like symptoms, Amir et al. (2009) observed no effects of threat vs. neutral words appearing at T1 on detection of neutral target word appearing at T2. The authors only showed evidence of a difference between these subjects and subjects without significant PTSD-like symptoms when they applied a complex dual-task design when they were asked to perform a categorization of whether T1 was a threat or neutral word, and the effect appeared largely driven by differences in the neutral condition, as accuracy following threat related words was quite similar across groups. Although, the significant methodological differences between studies limit firm conclusions, we speculate that the stimuli must be both relevant to the trauma experience and emotionally salient to reveal heightened attentional capture in PTSD patients. By utilizing probes capable of detecting disease-specific attentional biases, it may become possible to more directly test the relationship between these biases and the development and maintenance of PTSD. While attentional biases have been theorized to play a role in the transition from acute stress reactions to persistent PTSD-symptoms (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), longitudinal studies directly testing causal relations between such biases and PTSD symptoms have been limited, in part due to the lack of robust paradigms for assessing such symptoms.

These novel findings with the attentional blink paradigm may advance knowledge on information processing biases in PTSD. Models often attribute the attentional blink effect, a deficit in recognizing the second of two temporally proximal targets within a rapid stream, to central processes such as bottlenecks gating access to working memory (e.g., Chun & Potter, 1995) or errors in target retrieval from memory (Shapiro, Raymond, & Arnell, 1994). However, recent research examining the extent to which emotional stimuli impairs awareness of subsequent targets (‘emotion-induced blindness’) suggests that emotional cues have a dual impact on perception by grabbing spatial attention and inhibiting competing episodic representations at their location (Most & Wang, 2011). The present findings suggest that this process is relatively intact among veterans with PTSD. Indeed, disgust stimuli caused an attentional blink that was similar for veterans with PTSD, veterans without PTSD, and nonveteran controls. Unlike veterans without PTSD and nonveteran controls however, the present study suggests that spontaneous prioritization of combat emotional stimuli among veterans with PTSD inhibits formation of other representations. One important implication of these findings is that spontaneous prioritization of combat-related cues in the environment among veterans with PTSD may lead to inhibition of spatiotemporally competing safety information and this may be one mechanism by which symptoms are maintained (Grieger, Fullerton, & Ursano, 2004).

Although the present study suggests that the attentional blink paradigm with visual images may have great utility in delineating the nature and components of attentional biases for threat in PTSD, the present findings must be considered within the context of the study limitations. For example, the sample size for the PTSD and non-PTSD groups was relatively small. Furthermore, the PTSD group was limited to those with only combat-related trauma. Although data on a subsample of participants suggest that trauma exposure was statistically equivalent for veterans with and without PTSD, the absence of such data for the full sample is also a limitation of the present study. Related to this issue is that the present study may not be sufficiently poised to rule out the possibility that familiarity effects primarily account for the heightened attentional capture among veterans with PTSD. Although a subsample of veterans with PTSD and those without PTSD did not statistically differ in trauma exposure, the difference were nonetheless sizeable (with veterans with PTSD reporting more trauma exposure than those without PTSD) which further indicates that the sample size of the study was limited. Thus it does remain somewhat unclear if the attention effects reflect differential exposure to experiences related to the stimulus material as opposed to PTSD per se.

Despite the study limitations, the present findings may have treatment implications as trauma-exposed individuals encounter a continuous string of stimuli in daily life that compete for attentional resources. Preferential orienting to trauma cues may interfere with the processing of subsequent information in the environment for a relatively prolonged period among veterans with PTSD. Preferential processing of trauma cues may contribute to priming of negative emotional information about the traumatic even (Michael, Elhers, & Halligan, & 2005). Accordingly, the implementation of interventions that directly modify both vigilance for and difficulty disengaging from trauma-relevant cues among veterans with PTSD may offer symptom relief by decreasing the speed and strength with which representations of war related trauma become activated. Attention bias modification treatment appears to show some promise as a novel treatment for anxiety-related disorders, particularly social anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorders (Hakamata et al., 2010). Such data highlight the potential therapeutic benefits of extending attention bias modification interventions for the treatment of PTSD as reducing attentional bias for threat in this disorder may result in a corresponding reduction of symptoms.

Footnotes

The authors thank Sara Ann Bilsky, Mimi Zhao, and Bethany Ciesielski for their assistance with this study.

A subset of veterans with (n = 11) and without (n = 9) PTSD in the present study completed the Combat Exposure Scale (CES; Keane, Fairbank, Caddell, Zimering, Taylor, & Mora, 1989), a 7-item self-report measure of wartime stressors experienced by combatants. Items are rated on a 5-point frequency (1 = “no” or “never” to 5 = “more than 50 times”), 5-point duration (1 = “never” to 5 = “more than 6 months”), 4-point frequency (1 = “no” to 4 = “more than 12 times”) or 4-point degree of loss (1 = “no one” to 4 = “more than 50%”) scale. Respondents are asked to respond based on their exposure to various combat situations, such as firing rounds at the enemy and being on dangerous duty. The total CES score (ranging from 0 to 41) is calculated by using a sum of weighted scores, which can be classified into 1 of 5 categories of combat exposure ranging from “light” to “heavy.” Administration of the CES revealed no significant differences in trauma exposure between Veterans with (mean = 25.63, sd = 9.42) and without (mean = 20.44, sd = 8.38) PTSD, t(18)= 1.28, p = .21.

Healthy nonveteran controls from the present study (n = 20) rated each Combat (valence = -13.25, SD = 9.78; arousal = 29.88, SD = 20.76), Disgust (valence = -20.12, SD = 9.95; arousal = 37.01, SD = 21.56), Positive (valence = 17.87, SD = 8.56; arousal = 31.67, SD =14.43), and Neutral (valence = 2.04, SD = 1.32; arousal = 4.01, SD = 6.365) image for valence (-50 = extremely negative, +50 = extremely positive, 0 = being no positive or negative valence/neutral) and arousal (0 = none to 100 = extremely/most imaginable) after the experiment. A significant main effect of valence was found [F (3, 57) = 69.19, p < .001] such that combat images were rated more negatively than positive and neutral images (ps < .001). Disgust images were also rated as significantly more negative than positive and neutral images (ps < .001). However, the valence of combat and disgust images did not significantly differ from each other (p > .05). Positive images were also rated more positive than all the other images (ps < .001). A significant main effect of arousal was also found [F (3, 57) = 16.83, p < .001] such that combat, disgust, and positive images were rated significantly more arousing than neutral images (ps < .001). However, arousal ratings for combat, disgust, and positive images did not did not significantly differ from each other (p > .05).

This pattern of findings were unchanged when partialling out income, education, anxiety, and depression. In fact the nonsignificant Group X Lag interaction for combat-related threat distracters at Lag 8 became significant when partialling out anxiety (STAI-T) and depression (BDI) scores [F (2, 53) = 5.16, p < .01, partial η2 = .16]. Like Lag 2, Lag 4, and Lag 6, veterans with PTSD were less accurate in detecting the target following combat-related threat distracters at Lag 8 than veterans without PTSD (p < .01) and nonveteran healthy controls (p < .02) when partialling out anxiety and depression. By contrast, veterans without PTSD and nonveteran healthy controls did not significantly differ in this regard (p = .52) when partialling out anxiety and depression.

The mixed model ANOVA on percent accuracy was also conducted with just disgust and combat-related threat trials. The predicted Group X Lag X Emotion interaction was still significant [F (6, 165) = 2.81, p < .02, partial η2 = .09] suggesting that the observed group differences are specific to combat-related threat trials as opposed to a negativity bias per se. The mixed model ANOVA on percent accuracy was also conducted without the combat-related threat trials. The predicted Group X Lag X Emotion interaction was no longer significant [F (12, 330) = 1.33, p = .199, partial η2 = .05] suggesting that the observed group differences are accounted for by the combat-related threat trials.

References

- Algom D, Chajut E, Lev S. A rational look at the emotional stroop phenomenon: A generic slowdown, not a stroop effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;133:323–338. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Text Revision Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amir N, Taylor C, Bomyea J, Badour C. Temporal allocation of attention toward threat in individuals with posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:1080–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen JP, Read JP. Attentional control, trauma, and affect regulation: A preliminary investigation. Traumatology. 2010;16:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Holoshitz Y, Eldar S, Frenkel TI, Muller D, Charney DS, Pine DS, Fox NA, Wald I. Life-threatening danger suppresses attention bias to threat. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:694–698. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09070956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and non-anxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Lee HJ, Wells TT, Ellis AJ, Telch MJ. Association of predeployment gaze bias for emotion stimuli with later symptoms of PTSD and depression in soldiers deployed in Iraq. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:735–741. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10091309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Vythilingam M, Crowe SL, McCaffrey DE, Ng P, Wu CC, Scaramozza M, Mondillo K, Pine DS, Charney DS, Blair RJ. Cognitive control of attention is differentially affected in trauma-exposed individuals with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2012;9:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Holmes EA. Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:339–376. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Harvey AG. Attentional bias in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:635–644. doi: 10.1023/a:1024849920494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretié L, Hinojosa JA, Martin-Loeches M, Mercado F, Tapia M. Automatic attention to emotional stimuli: neural correlates. Human Brain Mapping. 2004;22:290–299. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun MM, Potter MC. A two-stage model for multiple target detection in rapid serial visual presentation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1995;21:109–127. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.21.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Koster EHW. Mechanisms of attentional biases towards threat in anxiety disorders: an integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Adams TG, Jr., Babson KA, Badour CL, Willems JL. The emotional Stroop task and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:817–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dux PE, Marois R. The attentional blink: A review of data and theory. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2009;71:1683–1700. doi: 10.3758/APP.71.8.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck MW, Derakshan N, Santos R, Calvo MG. Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion. 2007;7:336–353. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani N, Tone EB, Phifer J, Norrholm SD, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, Kamkwalala A, Jovanovic T. Attention bias toward threat is associated with exaggertated fear experssion and impaired extinction in PTSD. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:533–543. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmingham KL, Rennie C, Manor B, Bryant RA. Eye tracking and physiological reactivity to threatening stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:668–673. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieger TA, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and perceived safety 13 months after September 11. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:1061–1063. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen GE, Kanagaratnam P, Asbjørnsen AE. Patients with posttraumatic stress disorder show decreased cognitive control: evidence from dichotic listening. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2011;17:344–353. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710001736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakamata Y, Lissek S, Bar-Haim Y, Britton JC, Fox N, Leibenluft E, Ernst M, Pine DS. Attention Bias Modification Treatment: A meta-analysis towards the establishment of novel treatment for anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane T, Fairbank J, Caddell J, Zimering R, Taylor K, Mora C. Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychological Assessment. 1989;1:53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster EHW, Crombez G, Verschuere B, De Houwer J. Selective attention to threat in the dot probe paradigm: Differentiating vigilance and difficulty to disengage. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:1183–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International affective picture system (IAPS): Technical manual and affective ratings. University of Florida, Center for Research in Psychophysiology; Gainesville: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Levy BJ, Anderson MC. Individual differences in the suppression of unwanted memories: The executive deficit hypothesis. Acta Psychologica. 2008;127:623–635. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Cognitive abnormalities in post-traumatic stress disorder. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;10:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ, Amir N, Lipke HJ. Subliminal processing of threat cues in posttraumatic stress disorder? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1996;10:115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Michael T, Elhers A, Halligan SL. Enhanced priming for trauma-related material in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Emotion. 2005;5:103–112. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Most SB, Chun MM, Widders DM, Zald DH. Attentional rubbernecking: Cognitive control and personality in emotion-induced blindness. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2005;12:654–661. doi: 10.3758/bf03196754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Most SB, Scholl BJ, Clifford ER, Simons DJ. What you see is what you set: Sustained inattentional blindness and the capture of awareness. Psychological Review. 2005;112:217–242. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Most SB, Wang L. Dissociating spatial attention and awareness in emotion induced blindness. Psychological Science. 2011;22:300–305. doi: 10.1177/0956797610397665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunj BO, Ciesielski B, Armstrong T, Zhao M, Zald D. Making something out of nothing: Neutral content modulates attention in generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:427–434. doi: 10.1002/da.20806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Ciesielski B, Zald D. A selective impairment in attentional disengagement from erotica in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2011;35:1977–1982. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles SL, Shipherd JC, Welch LP, Yovel I. The role of attentional biases in PTSD: is it interference or facilitation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MR, Rothbart MK. Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:427–441. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro KL, Raymond JE, Arnell KM. Attention to visual pattern information produces the attentional blink in RSVP. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1994;20:357–371. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.20.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview MINI: the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffrin RM, Schneider W. Controlled and automatic human information processing: II. Perceptual learning, automatic attending and a general theory. Psychological Review. 1977;84:127–190. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SD, Most SB, Newsome L, Zald DH. An “emotional blink” of attention elicited by aversively conditioned stimuli. Emotion. 2006;6:523–527. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TC, Ryan MAK, Wingard DL, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, Kritz-Silverstein D, et al. New onset and persistent symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder self-reported after deployment and combat exposures: Prospective population based US military cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2008;336:366–371. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39430.638241.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;18:643–662. (Reprinted in 1992 in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 121, 15–23) [Google Scholar]

- Vasterling JJ, Brailey K, Constans JI, Sutker PB. Attention and memory dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:125–133. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, Keane T. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility.. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, TX. Oct, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Mathews A, MacLeod C. The emotional Stroop task and psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:3–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]