Abstract

Purpose

Our objective was to perform a systematic review of risk factors and prevention of gout. We searched Medline for fully published reports in English using keywords including but not limited to “gout”, “epidemiology”, “primary prevention”, “secondary prevention”, “risk factors’. Data from relevant articles meeting inclusion criteria was extracted using standardized forms.

Main Findings

Of the 751 titles and abstracts, 53 studies met the criteria and were included in the review. Several risk factors were studied. Alcohol consumption increased the risk of incident gout, especially beer and hard liquor. Several dietary factors increased the risk of incident gout, including meat intake, seafood intake, sugar sweetened soft drinks, and consumption of foods high in fructose. Diary intake, folate intake and coffee consumption were each associated with a lower risk of incident gout and in some cases a lower rate of gout flares. Thiazide and loop diuretics were associated with higher risk of incident gout and higher rate of gout flares. Hypertension, renal insufficiency, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, hyperuricemia, diabetes, obesity and early menopause were each associated with a higher risk of incident gout and/or gout flares.

Summary

Several dietary risk factors for incident gout and gout flares are modifiable. Prevention and optimal management of comorbidities is likely to decreased risk of gout. Research in preventive strategies for the treatment of gout is needed.

Keywords: Gout, risk factors, systematic review, gouty arthritis, alcohol, medications, chronic diseases, diet

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis that presents either as recurrent acutely painful arthritis of few joints, or as chronic inflammatory polyarthritis affecting both upper and lower extremity small and large joints, in a pattern similar to rheumatoid arthritis. Gout has a significant impact on a patient’s health related quality of life as well as his or her productivity and ability to function (1–2). It is estimated that approximately 5 million Americans have gout [1]. A recent cross-sectional study conducted in a managed care population using data from 1990–1999 found a 60% increase in prevalent gout or hyperuricemia over 10-years (3). Another population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota examined the development of incident gout, defined using the American College of Rheumatology preliminary criteria (4). The etio-pathogenesis of gout is well-understood with development of hyperuricemia as one of the key intermediary steps. However, it is well-known that hyperuricemia is far more common than gout implying that additional factors increase the risk of gout. A large majority of people with hyperuricemia do not have gout; however the risk of gout increases dramatically with increasing serum urate level.

Prevention of acute and chronic gout has the likelihood of decreasing not only the suffering associated with gout, but also reducing associated health care costs. This systematic review seeks to review published literature regarding risk factors for gout and primary and secondary prevention of this debilitating disease.

Methods

Search Criteria for the Systematic Review

An expert Cochrane librarian (L.F.) searched the OVID MEDLINE from 1950 to June Week 5 2010 using keywords including but not limited to “gout”, “epidemiology”, “primary prevention”, “secondary prevention”, “risk factors’(Appendix 1).

Study Selection and Data Abstraction

All titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion by two review authors independently (SR, JK), trained by the senior author (JAS) in performing systematic reviews. Any disagreements were resolved by referral to the senior coauthor (JAS). Data were abstracted by one coauthor (SR) from the included studies and checked for accuracy by another abstractor (AD). We utilized a standardized abstraction form. Studies were broadly divided into those providing information on risk factors for gout, prevention of gout, or both. Standardized data abstraction was done including the type of study (case control, cohort, randomized), incident or prevalent gout, number of patients involved in the study, risk factors assessed, and primary versus secondary prevention. We abstracted the odds ratios, relative risk or hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

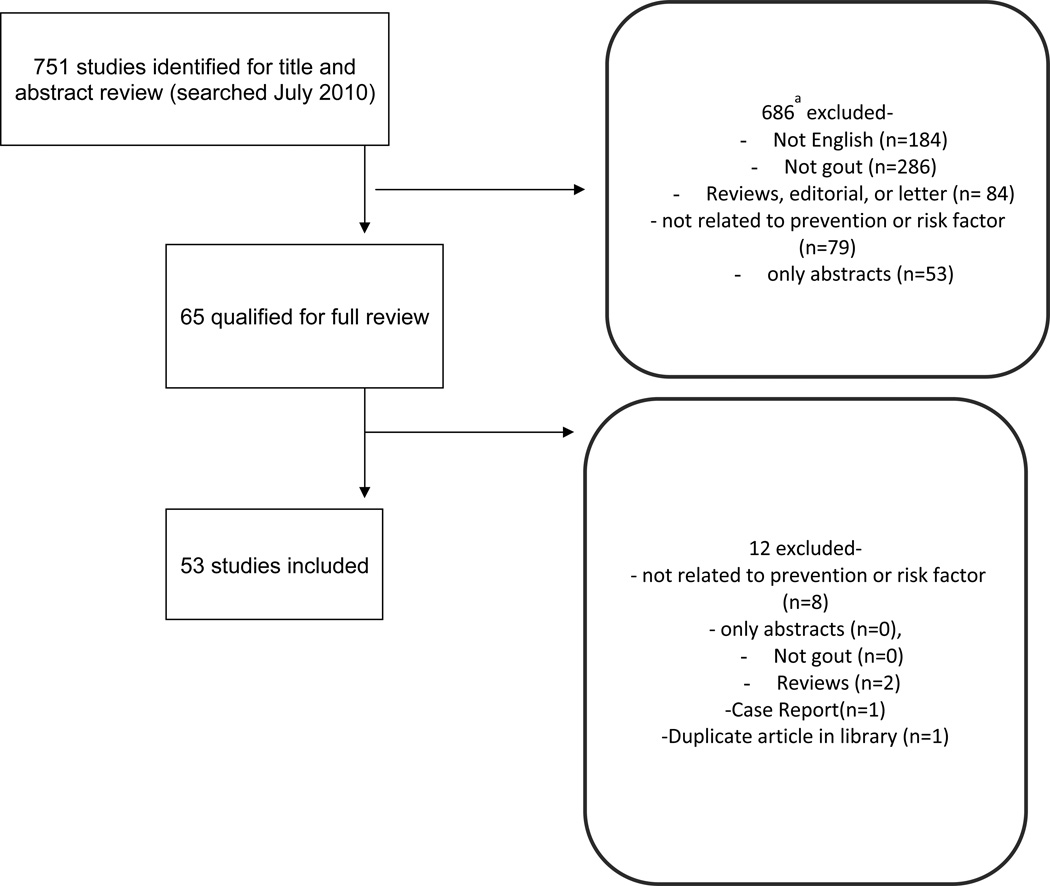

The search identified 751 articles related to prevention and/or risk factors for gout. With title and abstract review, 65 unique articles qualified for full text review. After full text review, 53 studies were included (5–57) (Figure 1). We excluded 12 studies because they did not provide data on risk factors/prevention, were reviews or abstracts (58–69). Of these included studies, 1 was related to prevention, 48 were related to risk factors, and 4 to both risk factors and prevention. In this study, we summarize all the available data in the tables and highlight key studies and findings in the narrative.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included studies

Risk Factors for Gout

Current published evidence shows that there are numerous risk factors that contribute to the onset or progression of gout. All relevant information associated with gout and their risk factors have been summarized in the table below (Tables 1–4). Risk factors were grouped into categories relating to alcohol use, diet, medications, and the presence of chronic disease. Several studies specified whether they examined each risk factor for the risk of incident or prevalent gout, although some studies did not specify this. The majority presented the risk of gout flares in either patient with known gout (termed prevalent gout in these studies and in this review) or gout flares in those without previous known gout (incident gout).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients in studies included in the systematic review

| Author and Year | Mean age (SD) [median; range] | %male | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott et al.,2005 (5) | 45.4(14.6) | 60% | 28,924 |

| Alvarez-Nemegyei et al., 2005 (6) | 54(12) | 98% | 90 |

| Anagnostopoulos et al., 2010 (7) | 51.08(15.25) | NR | 3.528 (1,705 survey responders) |

| Andracco et al., 2009 (8) | 61.8(13.7) | 86% | 73 |

| Annemans et al., 2008 (Germany) (9) | 63.1(13.1) | 80% | 2.5 million |

| Annemans et al., 2008 (UK) (9) | 65.6(13.8) | 82% | 2.4 million |

| Arromdee et al., 2002 (10) | NR | 77% | 81(39 cases of gout) |

| Bhole et al., 2010 (11) | 46.5 | 44% | 4,427 |

| Brauer et al., 1978 (12) | 42.3 | 51% | 766 |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | Aborigines 58.9(11.6); Non-Aborigines 59.2(10.9) | 44% | 1044 |

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | 53.1(13.3) | NR | 7,836 |

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | 50.1(15.1) | NR | 19,354 |

| Chen et al., 2007 (15) | NR | NR | 12,179 |

| Choi et al., 2004 (16) | NR | 100% | 47,150 (730 cases of gout) |

| Choi et al., 2004 (17) | NR | 100% | 47,150 (730 cases of gout) |

| Choi, Atkinson et al., 2004 (18) | NR | 100% | 47,150 (730 cases of gout) |

| Choi, 2007 (19) | 54.9 | NR | 51,297 (2,773 cases of gout) |

| Choi et al., 2007 (24) | 54.1(10) | 100% | 45,869 (757 cases of gout) |

| Choi et al., 2008 (21) | NR | 100% | 46,393 (755 cases of gout) |

| Choi et al., 2008 (22) | 46.2 | 100% | 11,351 |

| Choi et al., 2009 (23) | NR | 48% | 46,994 (1,317 cases of gout) |

| Choi and Curhan, 2007 (20) | NR(45) | NR | 14,758 |

| Choi et al., 2007 (25) | NR | 47% | 14,761 |

| Chou et al., 1998 (26) | 48 | 42% | 342 |

| Cohen et al., 2008 (27) | 58.9 | 48% | 259,209 |

| Creighton et al., 2005 (28) | NR | NR | 1,825 |

| Elliot et al., 2009 (29) | NR | NR | NR |

| Fam et al., 1996 (30) | Women 77.7±8.3; Men 72.4±11.5 | 34% | Women (n=21) Men (n=11) |

| Friedman et al., 2008 (31) | NR (52) | NR | 411 |

| Gurwitz et al., 1997 (32) | NR | 23% | 9,249 |

| Hak and Choi, 2008 (33) | 46 | N/A | 7,662 |

| Hak et al., 2010 (34) | Premenopausal: 51.9±2.2; Postmenopausal natural: 63±6.8; Postmenopausal surgical: 62.5±6.9 |

N/A | 92,535 (1703 incident gout) |

| Hochberg et al., 1995 (35) | categorized by study site | NR | 923 |

| Hunter et al., 2006 (36) | 52 | 80% | 197 |

| Janssens et al., 2008 (37) | Gout: 55.1(13.5); no gout: 55.2(13.5) | NR | 3,764 (gout, n=70; no gout, n=210) |

| Kang et al., 2007 (38) | 61.8 | 96% | 154 (gout, n=67; no gout, 67) |

| Ko et al., 2007 (39) | 61.8(13.45) | 50% | 940 |

| Lin et al., 2000(41) | Men: 49.45±12.57 Women:47.34±13.52 | 48% | 4,097 (42 cases of gout) |

| Lin et al., 2000(40) | NR | 48% | 3,185 (36 cases of gout) |

| Li-Yu et al., 2001 (42) | NR | NR | 57 |

| Lyu et al., 2003 (43) | NR | NR | 92 cases and 92 controls |

| Mijiyawa et al., 2000 (44) | NR | NR | 8,351 |

| Padang et al., 2006 (45) | NR | NR | 380 |

| Prior et al., 1987(46) | Gout, 40.9 (14); No gout, 32.5 (15.5) | NR | 933 |

| Roubenoff et al., 2010 (47) | NR | 91% | 1271 |

| Shibolet et al., 2004 (48) | Liver transplant: 48(20–69); Heart transplant: 57(23–78) | N/A | 122 |

| Shoji et al., 2004 (49) | Gouty flare:45.5; No gout flare:50 | N/A | 267 |

| Shulten et al., 2009 (50) | NR | 86% | 29 |

| Stamp et al., 2006 (51) | gout: 55 (range, 30–81); no gout: 51 (31–76) | N/A | 94 (47 patients each) |

| Suppiah et al., 2008 (52) | Diabetics: gout: 61.1 (10.2); no gout: 55.9 (12.3) | N/A | 292 |

| Tikly et al., 1997 (53) | Gout:54.3 (range, 30–86); no gout: 54.1 (32–82) | N/A | 90 |

| Williams et al., 2008 (54) | 58.62% | 100% | 228 |

| Wu et al., 2009 (55) | 72.4 (4.4) | 74% | 2237 |

| Yu et al., 1961 (56) | NR | NR | 506 |

| Zhang et al., 2006 (57) | 52 (range, 29–83) | 80% | 197 |

N/A, not applicable all subjects are women; NR, not reported

Table 4.

Medications as a Risk Factor for gout

| Author year [reference] | Incident/ prevalent gout |

Medications as a risk Factor | Odds ratio (OR), Risk ratio (RR) or Hazard ratio (HR), Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bhole et al., 2009 (11) | incident | Diuretic use vs. no diuretic use | RRc for incident gout: Women, 2.39 [1.53–3.74]; Men, 3.41 [2.38–4.89] |

| Chen et al.,2003 (14) | prevalent | Diuretic use vs. no diuretic usea | |

| Hunter et al., 2006 (36) | prevalent | Any diuretic use vs. none | OR of gout flares, 3.6 [1.4–9.7] |

| Hunter et al., 2006 (36) | prevalent | Loop Diuretics use vs. no loop diuretic use | OR of recurrent gout attacks, 3.8 |

| Hunter et al., 2006 (36) | prevalent | Thiazide diuretics vs. no thiazide | OR of recurrent gout attacks, 3.2 |

| Janssens et al., 2006 (37) | incident | Diuretic use vs. no diuretic use | IRR of incident gout, 0.6 [0.2–2.0] |

| Choi et al., 2005 (16) | incident | Diuretic use vs. none | RR of gout flare, 1.77 [1.42–2.20] |

| Lin et al., 2000 (40) | incident | Use of diuretics during follow up vs. none | OR of incident gout, 6.47 [2.03–18.8] |

| Stamp et al , 2006 (51) | prevalent | Use of loop diuretics vs. none | Not specified |

| Suppiah et al., 2008 (52) | prevalent | Diuretic use vs. no diuretic use | OR of prevalent gout 3.2; [.6–6.6] |

| Creighton et al., 2005 (28) | incident | HIV positive patients on Ritonavir vs. not | OR of incident gout, 22 [5–104] |

| Gurwitz et al., 1997 (32) | prevalent | Non-thiazide antihypertensive vs. none | RR for initiation of anti-gout therapy 1.00 [0.65–1.53] |

| Shoji et al., 2004 (49) | prevalent | Antihyperuricemic drug use vs. none | OR of gout flare, 0.22 [.10-.47] |

| Kang et al., 2008 (38) | prevalent | Colchicine prophylaxis (yes vs.no) | OR of gout flare, 0.16 [0.04–0.61]b |

| Abbott et al., 2005 (5) | incident | Use of Neoral vs. Tacrolimus | HR of incident gout, 1.25 [1.07–1.47] |

Stamp et al , 2006 (51) and Shibolet et al., 2004 (48) assessed risk with medication use, but did not provide risk ratio

p-value <0.001;

p-value =0.008

Adjusted for age, education level, body mass index (BMI), alcohol consumption, hypertension, use of diuretics, blood glucose level, blood cholesterol level and menopausal status

Alcohol consumption and the risk of gout

We identified 15 articles that included alcohol as a risk factor for incident and/or prevalent gout (Table 2) (11)(13)(14)(17)(26)(30)(40)(41)(43)(44)(50)(53)(54)(57); 2 studies did not provide risk ratios or p-values (50)(44). Almost all studies reported that alcohol intake increased the risk of developing incident or prevalent gout. For instance, in the Framingham cohort of 2,476 women and 1,951 men, alcohol use was associated with the 3-fold higher risk of incident gout among women and 2-fold higher risk in men, compared to those with no alcohol intake or ≤1 ounce/week (11) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for gout

| Author, year (reference) | Incident/ Prevalent gout |

Alcohol as a risk Factor | Odds ratio (OR), Risk ratio (RR) or Hazard ratio (HR) [95% confidence interval] |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhole et al., 2009 (11) | incident | ≥ 7 oz. of pure alcohol/week vs. no alcohol | RR of incident gout, 3.10 | |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | prevalent | > 15 grams per day vs. no alcohol | OR of gout flare,1.2 [.4–3.4] | |

| Chen et al.,2003 (14) | prevalent | amount not specified | <0.0001 | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (17) | incident | 10–14.9 grams alcohol per day vs. none | RR of incident gout, 1.32 [.99–1.75] | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (17) | incident | 15–29.9 grams alcohol per day vs. none | RR of incident gout, 1.49, [1.14–1.94] | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (17) | incident | 30–49.9 grams alcohol per day vs. none | RR of incident gout, 1.96 [1.48–2.60] | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (17) | incident | > 50 grams alcohol per day vs. none | RR of incident gout, 2.53 [1.73–3.70] | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (17) | incident | Beer, 12 oz. serving per day vs. none | RR of incident gout, 1.49 [1.32–1.70] | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (17) | incident | Hard liquor, one shot per day vs. none | RR of incident gout, 1.15 [1.04–1.28] | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (17) | incident | Wine, 4 oz. per day vs. no wine | RR of incident gout, 1.04 [0.88–1.22] | |

| Chou and Lai, 1998 (26) | prevalent | amount not specified | Not specified | |

| Cohen et al., 2008 (27) | incident | amount not specified | HR of incident gout after dialysis, 1.33 | <0.001 |

| Fam et al., 1996 (30) | prevalent | amount not specified | Not specified | 0.003 |

| Lin et al., 2000 (41) | incident | alcohol consumption vs. no alcohol | OR of incident gout, 3.27 [1.57–7.32] | |

| Lin et al., 2000 (40) | incident | alcohol consumption vs. no alcohol | OR of incident gout, 1.62[1.27–2.06] | 0.042 |

| Lyu et al., 2003 (43) | incident | alcohol consumption ≥ 3 grams | OR of incident gout, 3.27 [1.35–7.92] | 0.02 |

| Tikly et al., 1998 (53) | prevalent | amount not specified | OR for gout 3.5 [1.6–1.7] | 0.05 |

| Williams et al., 2008 (54) | incident | amount not specified | RR of incident gout, 1.19 [1.12–1.26] | <0.0001 |

| Zhang et al., 2006 (57) | prevalent | 1 to 2 drinks in 2 day period vs. no alcohol | OR of recurrent attacks 1.1 [0.7–2.0] | <0.005 |

| Zhang et al., 2006 (57) | prevalent | 3 to 4 drinks in 2 day period vs. no alcohol | OR of recurrent gout attacks, 0.9 [0.4–1.8] | <0.005 |

| Zhang et al., 2006 (57) | prevalent | 5 to 6 drinks in 2 day period vs. no alcohol | OR of recurrent gout attacks, 2.0 [0.9–4.5] | <0.005 |

| Zhang et al., 2006 (57) | prevalent | ≥7 alcohol drinks in two day period vs. none | OR of recurrent gout attacks, 2.5 [1.1–5.9] | <0.005 |

Five articles focused on alcohol consumption measured as grams per day or drinks per day (11)(13)(17)(57)(43). Choi et al. analyzed the prospective data, derived from the Health Professionals follow-up study over 12 years investigating the relationship between various risk factors (diet, alcohol, soft drinks, coffee etc.) and the risk of incident gout in 47,150 males with no history of gout at baseline (17). During the 12 year period, 730 confirmed new cases of gout were identified, that met the American College of Rheumatology Preliminary criteria for acute gouty arthritis (4). In this study, Choi and colleagues (2004) showed that increasing alcohol intake is associated with higher risk of incident gout (17), similar to findings from other studies (40)(41)(43)(57). The consumption of hard liquor, or having the equivalent of one shot per day, was also significantly associated with the risk of incident gout. Consumption of beer, but not wine, was significantly associated with incident gout (17). Thus, the risk of developing gout varies greatly and is dependent on the type and amount of the alcoholic beverage that is consumed (Table 2). As stated above, beer bestows a larger risk of incident gout as compared to wine or spirits. Alcohol was also a risk factor for prevalent gout in several studies, although the majority of these studies did not specify the association by the amount of alcohol (14)(26)(30)(53)(57). Chen et al. found that alcohol intake was associated with a higher risk of gout flares per year, after controlling for age, gender, and time elapsed since onset of gout (14). Chou et al. indicated that significantly increased alcoholism was found in gouty patients when compared with non-gouty patients (26) . Fam et al. confirmed that alcoholism was indeed, a risk factor for the development of gouty arthritis (30). Tikly et al. stated that gout patients were 3.5 times more likely to consume alcohol when compared to those individuals that do not have gout (53). Lastly, Zhang et al. discovered that, when compared with no alcohol consumption, odds ratios were 1.1, 0.9, 2.0, and 2.5 for 1, 2, 3, to 4, 5 to 6, and 7 or more drinks consumed over a 2-day period, respectively (57).

Diet, Beverages and the risk of gout

Evidence suggests that diet is a risk factor for incident or prevalent gout (Table 3). We found several articles assessing diet as a risk factor for gout (21)(13)(20)(50)(25)(43)(54)(23)(18)(24)(25). Two articles described the relationship of soft drink or consumption and gout or hyperuricemia (21)(25). Using a validated food frequency questionnaire, Choi et al. reported that consumption of 2 or more sugar sweetened soft drinks a day was strongly associated with an increased risk of gout in men (RR=1.85, 95% CI: 1.08–3.16) (21). Moreover, it was also found that those fruits which are high in fructose, as well as fruit juices are also a contributing factor to an increased risk of gout in men (21). Consumption of diet soft drinks does not seem to be associated with an increased risk of gout (21). Sugar-sweetened soft drinks in increasing amounts are associated with higher odds of hyperuricemia (25).

Table 3.

Diet as a Risk Factor for gout

| Author year (reference) | Incident/ Prevalen t gout |

Diet as a risk Factor | Odds ratio (OR), Risk ratio (RR) or Hazard ratio [95% CI] |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Soft Drinks, Beverages and Fructose | ||||

| Choi et al., 2008 (25) | incident | Sugar sweetened soft drinks in various amounts vs. none |

ORa of incident hyperuricemia (>7 mg/dl for men; >5.7 mg/dl for women): <.5 /day, 0.08 [.01-.15] .5-.9 /day, 0.15 [.06-.24] 1–3.9 /day, 0.33 [.21-.46] ≥ 4/day, 0.42 [.11-.73] |

<0.001 or trend |

| Choi and Curhan, 2008 (21) | incident | Increasing quintile of total fructose intake |

RRb of incident gout (ref: 1st quintile) 2nd quintile, 1.29 [1.02–1.64] 3rd quintile, 1.41[1.09–1.82] 4th quintile, 1.84 [1.40–2.41] 5th quintile, 2.02 [1.49–2.75] |

<0.001 for trend |

| Choi and Curhan, 2008 (21) | incident | Diet soft drinks in increasing mount versus <1/month |

RRb of incident gout (ref: <1/month) 1/month-1/week, 1.18 [0.97–1.45] 2–4/week, 1.15 [0.89–1.48] 5–6//week, 1.09 [0.86–1.38] 1/day, 1.07 [0.83–1.38] ≥2/day, 1.12 [0.82–1.52] |

0.99 for trend |

| Choi and Curhan, 2008 (21) | incident | Sugar Sweetened soft drinks in increasing amount versus <1/month |

RRb of incident gout (ref: <1/month) 1/month-1/week, 1.00 [0.84–1.20] 2–4/week, 0.99 [0.77–1.29] 5–6//week, 1.29 [1.00–1.68] 1/day, 1.45 [1.02–2.08] ≥2/day, 1.85 [1.08–3.16] |

0.002 for trend |

|

Coffee and Tea | ||||

| Choi et al., 2007 (24) | incident | Coffee in various amounts vs. None |

RRc of incident gout (ref: no coffee) <1 cup/day, .97 [.78-.1.2] 1–3 cups /day, .92 [75-.1.11] 4–5 cups /day, .60 [.41-.87] ≥ 6 cups coffee/day, .41 [.19-.88] |

0.009 for trend |

| Choi et al., 2007 (24) | incident | Decaffeinated Coffee in various amounts vs. none |

RRc of incident gout <1cup /day, .83 [.70-.99] 1–3 cups/day, .67[.54-.82] ≥ 4 cups /day, .73[.46–1.17] |

0.002 for trend |

| Choi et al., 2007 (24) | incident | Tea in various amounts vs. none | RRc of incident gout (ref: no tea) <1 cup/day, 1.09 [.92–1.30] 1–3 cups /day, 1.06 [0.85–1.33] ≥ 4 cups /day, 0.82 [.38–1.75] |

0.62 for trend |

| Choi and Curhan, 2007 (20) | prevalent | Coffee and tea in various amounts vs. none |

Mean difference, Serum urate (mg/dl)d <1 cup/day, −0.02 [-.09-.05] 1–3 cups /day, 0.00 [-.10-.09] 4–5 cups /day, −0.22 [-.35 to -.09] ≥ 6 cups coffee/day, −0.36 [-.57 to -.14] |

<0.001 for trend |

| Choi and Curhan, 2007 (20) | prevalent | Decaffeinated coffee in various amounts vs. none |

Mean difference, Serum urate (mg/dl)d <1 cup/day, −0.05 [-.24-.15] 1–3 cups /day, −0.24 [-.54-.06] ≥ 4 cups coffee/day, −0.42 [-1.01, 0.17] |

<0.35 for trend |

| Meat, Dairy, Vegetable, Fruits, Seafood, Dietary fiber, Folate and Vitamin C | ||||

| Choi et al., 2004 (18) | incident | Total meat intake for each additional serving/day |

RR of incident gout for each additional serving/day, 1.21 [1.04–1.41] |

|

| Williams et al., 2008 (54) | incident | Meat consumption vs. no meat | RR of incident gout, 1.45 [1.06–1.92] | 0.002 |

| Shulten et al., 2009 (50) | prevalent | Meat intake vs. no meat intake | Not specified | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (18) | incident | Total dairy product intake | RRe of incident gout for each additional serving/day, 0.82 [0.75–0.90] |

|

| Choi et al., 2004 (18) | incident | Intake of high fat dairy products | RR of incident gout for each additional serving/day, 0.99 [.89–1.10] |

<0.001 |

| Choi et al., 2004 (18) | incident | Intake of low fat dairy products | RR of incident gout for each additional serving/day, 0.79 [.71-.87] |

<0.001 |

| Shulten et al., 2009 (50) | prevalent | Dairy intake vs. no dairy intake | Not specified | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (18) | incident | Purine rich vegetable intake | RR of incident gout for each additional serving/day, 0.95 [78–1.16] |

NS |

| Williams et al., 2008 (54) | incident | Greater fruit intake per pieces vs. none | RR of gout flare .73 [62-.84] | <0.0001 |

| Choi and Curhan, 2008 (21) | incident | Consumption of an apple or orange a day vs. <1/day |

RR of incident gout, 1.64 [1.05–2.56] | |

| Choi et al., 2004 (18) | incident | Seafood intake | RR of incident gout for each additional serving/day, 1.07 [1.02–1.12] |

0.02 |

| Shulten et al., 2009 (50) | prevalent | Seafood intake vs. no seafood | Not specified | |

| Lyu et al., 2003 (43) | incident | Dietary fiber in various amounts vs. <6.2 grams/day |

OR of incident gout 6.2–7.94 grams/day, 0.44 [0.17, 1.13] ≥7.95 grams/day, 0.38 [.18-.79] |

0.09 |

| Lyu et al., 2003 (43) | incident | Folate in various amounts vs. <51.5 micrograms/day |

OR of incident gout 51.5–62.5 micrograms/day, 0.30 [.12-.77] ≥63 micrograms/day, 0.33 [16-.69] |

0.04 |

| Lyu et al., 2003 (43) | incident | Vitamin C intake in various amounts vs. <51 mg/day |

OR for incident gout, 52–62 mg/day, 0.58 [0.28–1.20] ≥62 mg/day, 0.31 [0.15, 0.65 |

<0.01 |

| Choi et al., 2009 (23) | incident | Total Vitamin C intake in various amounts vs. <250 mg/day |

RRf of incident gout, 250–499 mg/day, 0.97 [.71-.97] 500–1499 mg/day, 0.66 [.52-.86] >1500 mg/day, 0.55 [.36-.86] |

<0.001 |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | prevalent | Betel quid chewing (yes vs. no) | OR for gout flare, 2.2 [1.2–4.3] | |

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, body mass index, use of diuretics, beta-blockers, allopurinol and uricosuric agents, hypertension,glomerular filtration rate, intake of alcohol, total meats, seafood, dairy foods, coffee, tea, total caffeine, and total energy, and for diet soft drinks and orange juice.

Adjusted for age, total energy intake, body mass index, diuretic use, history of hypertension, history of renal failure; intake of alcohol and total vitamin C; and percentage of energy from total carbohydrate to estimate effects of fructose for equivalent energy from other carbohydrates

Adjusted for age, total energy intake, BMI, diuretic use, history of hypertension, history of renal failure, and intake of alcohol, total meats, seafood, purine-rich vegetables, dairy foods, total vitamin C, decaffeinated coffee and tea.

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, body mass index, use of diuretics, beta-blockers, allopurinol and uricosuric agents, hypertension, glomerular filatration rate, alcohol use, total meats, seafood, diary foods, decaffeinated coffee and tea.

Adjusted for age, total energy intake, body-mass index, use of diuretics, presence or absence of a history of hypertension, renal failure, and intake of alcohol, fluid, total meats, seafood, purine-rich vegetables, and dairy products.

Adjusted for age, total energy intake, body mass index, diuretic use, history of hypertension, history of renal failure, and intake of alcohol, total meats, seafood, dairy foods, fructose, and coffee (regular and decaffeinated).

A few studies reported on the relationship between dairy, meat, seafood, fruit, and purine rich vegetable intake and risk of gout (18)(21)(54) . In their analyses of Health professional follow-up study, Choi et al. found that increasing daily servings of meat and seafood were associated with significantly increased risk of incident gout, while dairy products were protective (18). Most recently, Dalbeth et al. found that all types of milk increase the fractional excretion of uric acid in humans (70) and both lipid and protein fractions of dairy products modulate the inflammatory response to monosodium urate crystals in animal models (71). These mechanisms may explain the lowering of risk of incident gout as noted by Choi and others.

Moderate intake of vegetables that are rich in purine or protein was not associated with increased risk of incident gout. In one study, greater intake of fruits was associated with significantly lower risk of incident gout (54), while in another study consumption of an apple or orange a day or more was associated with higher risk of incident gout with relative risk of 1.64 [95% CI: 1.05–2.56], compared to those with <1 apple or orange /day (21).

Two studies investigated coffee consumption and the risk of gout (20)(24) using the data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (20) and the data from the Health Professionals follow-up study (24). Increasing coffee intake, but not tea intake, was associated with significantly lower risk of incident gout in men (24).

One study indicated that intake of folate was associated with lower risk of incident gout (43), while higher intake of total Vitamin C was associated with lower risk of incident gout in two studies (23)(43).Higher dietary fiber intake had a non-significant association with lower risk of incident gout (p=0.09) in one study (43). The chewing of Betel quid, which is the leaf of a vine valued for its medicinal and mild stimulant properties, was associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk of developing gout among the Taiwanese aborigine population (13).

Medications and the risk of gout

Our search resulted in 13 articles that examined the relationship between medications and risk of gout (11)(14)(36)(37)(16)(40)(51)(52)(28)(32)(49)(38)(5) (Table 4). Most articles focused on the use of diuretics, including thiazide and loop diuretics. Studies reported increased risk of both incident gout and gout flares in patients with prevalent gout receiving loop or thiazide diuretics. In one study, cyclosporine was compared to tacrolimus and found to be associated with higher risk of incident gout than tacrolimus in transplant patients (5). Use of colchicine and urate-lowering therapy were each associated with reduction in the risk of gout flares in subjects with prevalent gout (38)(49).

Although, not included in our search of the literature, investigating the relationship between low and high dose aspirin and the maintenance of uric acid levels is critical. Evidence suggests that high doses of aspirin are uricosuric, while low dosages cause uric acid retention (72). It is thought that this withholding of uric acid may lead to hyperuricemia, which is a causal agent in the development of gout. One particular study found that mini-dose aspirin, even at a dosage of 75mg a day, caused significant changes in renal function and uric acid handling in a group of elderly patients (73). Therefore, the administering of low dose aspirin may also be a risk factor for gout.

Chronic Diseases and the risk of gout

Current evidence indicates that the presence of chronic disease is a common risk factor for gout. Our search found 34 articles that assessed chronic disease as a risk factor for gout (Table 5). Many of the included articles explored multiple studies and were either cohort (5)(8)(10)(11)(12)(14)(15)(17)(18)(19)(21)(22)(23)(24)(28)(32)(35)(42)(47)(54) or case-control studies (37)(43)(45)(53) . Study populations in the cohort studies varied from 57 individuals in one study (42) to 51,297 in another (19). For case control studies, sample sizes ranged from 70 in Janssens et al.(37) to 380 in Padang et al. (45). Study findings have indicated that heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, hyperuricemia, obesity, renal disease including renal insufficiency, elevated triglyceride and cholesterol levels, menopause, undergoing surgery, and elevated creatinine levels were all associated with the risk of gout (Table 5).

Table 5.

Chronic Disease as a Risk Factor for gout

| Author year (reference) | Incident/ prevalent gout |

Chronic Disease and hyperuricemia as a risk Factor |

Odds ratio (OR), Risk ratio (RR) or Hazard ratio [95% CI] |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hyperuricemia | ||||

| Annemans et al.,2008 (Germany) (9) | prevalent | sUA level > 7–8 vs. sUA<6mg/dl | OR of gout flare 1.65 [1.17–2.33] | <.01 |

| Annemans et al.,2008 (Germany) (9) | prevalent | sUA level > 8–9 vs. sUA<6mg/dl | OR of gout flare 2.37 [1.67–3.36] | <.01 |

| Annemans et al.,2008 (Germany) (9) | prevalent | sUA level from 6–7 vs. sUA<6mg/dl | OR of gout flare 1.37 [91–2.05] | NS |

| Annemans et al.,2008 (Germany) (9) | prevalent | sUA level ≥ 9 vs. sUA<6mg/dl | OR of gout flare 2.48 [1.77–3.49] | <.01 |

| Annemans et al.,2008 (UK study) (9) | prevalent | sUA>8–9 vs. sUA<6mg/dl | OR of gout flare 1.71 [1.04–2.13] | <.01 |

| Annemans et al.,2008 (UK study) (9) | prevalent | sUA level >7–8 vs. sUA<6mg/dl | OR of gout flare 1.49 [1.21–2.42] | <.01 |

| Annemans et al.,2008 (UK study) (9) | prevalent | sUA level from 6–7 vs. sUA<6mg/dl | OR of gout flare 1.33 [.92–1.94] | NS |

| Annemans et al.,2008 (UK study) (9) | prevalent | sUA level ≥ 9 vs. sUA<6mg/dl | OR of any gout 2.15 [1.53–3.01] | <.01 |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | prevalent | Hyperuricemia vs. no hyperuricemia | OR of gout flare 8.7 [3.9–19.4] | |

| Kang et al., 2008 (38) | incident | PresurgicalUrate level >9 mg/dl | OR of gout flare 8.25 [2.23–30.54] | 0.002 |

| Kang et al., 2008 (38) | incident | PresurgicalUrate level 6–7 mg/dl | OR ofgout flare 0.56 [0.13–2.46] | 0.441 |

| Kang et al., 2008 (38) | incident | PresurgicalUrate level 7–8 mg/dl | OR of gout flare 1.35 [0.36–5.1] | 0.659 |

| Kang et al., 2008 (38) | incident | PresurgicalUrate level 8–9 mg/dl | OR of gout flare 2.23 [0.64–7.81] | 0.211 |

| Padang et al., 2006 (45) | prevalent | Hyperuricemia (yes vs. no) | OR of gout flare 24.09 [12.65–46.51] | <.0001 |

| Prior et al., 1987 (46) | incident | Serum urate | RR Not specified | <0.05 |

| Wu et al., 2009 (55) | prevalent | Serum urate levels: 6–8.99 mg/dl vs. < 6 mg/dl | OR of recurrent gout flare 2.1 [1.7–2.6] | |

| Lin et al., 2000 (41) | incident | Serum Urate | OR of incident gout, 5.21 [2.91–9.24] | |

| Lin et al., 2000 (41) | incident | Serum Urate change | OR of incident gout, 1.62 [1.23–2.19] | |

| Shoji et al., 2004 (49) | prevalent | Reduction in Serum urate | OR of gout flare, .42 [31-.57] | <.0001 |

|

Hypertension and Heart Disease | ||||

| Bhole et al., 2009 (11) | incident | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | RR for prevalent gout, 1.82 | |

| Brauer et al., 1978 (12) | incident | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | Not specified | <.001 |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | prevalent | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | OR of gout flare, 2.2 [1.1–4.3] | |

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | prevalent | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | Not specified | <.0001 |

| Chen et al., 2007 (15) | incident | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | RR of gout flare 19–44 yrs, 0.99 [0.78–1.27] 45–64 yrs, 1.02 [0.91–1.14] ≥65 yrs, 1.42 [1.23–1.65] |

>0.05 >0.05 >0.05 |

| Choi et al., 2005 (16) | incident | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | RR of incident gout, 2.31 [1.96–2.72] | |

| Janssens et al., 2006 (37) | incident | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | IRR of incident gout, 2.6 [1.2–5.6] | |

| Hochberg et al., 1995 (35) | incident | Incident hypertension (yes vs. no) | RR of incident gout, 3.78,[2.18–6.58] | |

| Hochberg et al., 1995 (35) | incident | Systolic blood pressure mm Hg | RR of new gout flare 1.96 [1.14–3.38] | |

| Roubenoff et al., 1991(47) | incident | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | RR of incident gout, 3.26 | .002 |

| Tikly et al., 1998 (53) | incident | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | OR for incident gout, 3.3 [1.7–6.3] | |

| Mijiyawa et al., 2000 (44) | prevalent | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | Not specified | |

| Janssens et al., 2006 (37) | incident | heart failure vs. no heart failure | IRR of new gout flare 20.9 [2.5–173.8] | |

| Janssens et al., 2006 (37) | incident | Myocardial infarction (yes vs. no) | IRR of new gout flare 1.9 [0.7–4.7] | |

| Anagnostopoulos et al., 2010 (7) | prevalent | Hypertension vs. no hypertension | OR of prevalent gout 2.78 [.65–4.7] | <.01 |

|

Obesity and Body mass index | ||||

| Chen et al.,2007 (15) | prevalent | Overweight vs. not overweight | RR of gout flare: 19–44 years, 1.7 [1.52–1.92] 45–64 years, 1.17 [1.08–1.27] ≥65 years, 1.36 [1.16–1.58] |

|

| Choi et al., 2005 (16) | incident | BMI in various categories vs. BMI 21–22.9 | RR of incident gout 23–24.9, 1.65 [1.27–2.13] 25–29.9, 1.95 [1.44–2.65] 30 to 34.9, 2.33 [1.62–3.36] ≥35, 2.97 [1.73–5.10] |

<.001 |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | prevalent | Obesity vs. no obesity | OR of gout flare, 0.7 [0.3–1.8] | |

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | prevalent | Obesity vs. no obesity | Not specified | <.0001 |

| Choi et al., 2005 (16) | incident | ≥30 lbs weight gain after age 21 vs. range of −4 to 4 lb weight change | RR of incident gout1.99 [1.49–2.66] | <.001 |

| Choi et al., 2005 (16) | incident | 10 lbs weight loss since baseline vs. range of −4 to 4 lb weight change | RR of incident gout, 0.61 [.40-.92] | <.001 |

| Bhole et al., 2009 (11) | incident | Obesity(BMI≥30) vs. no obesity | RR for incident gout 2.74 | |

| Brauer et al., 1978 (12) | incident | BMI vs. normal BMI | Not specified | <.001 |

| Lin et al., 2000 (41) | incident | Obesity vs. no obesity | 2.86 [1.29–6.45] | |

| Lin et al., 2000 (41) | incident | Baseline BMI | OR of incident gout, 1.01 [0.72–1.22] | |

| Lin et al., 2000 (41) | incident | BMI change during follow up | OR of incident gout, 1.51 [1.12–2.19] | |

| Mijiyawa et al., 2000 (44) | prevalent | Overweight/obesity vs. no obesity | Not specified | |

| Tikly et al., 1998 (53) | incident | Obesity | OR for incident gout, 5.3 [2.6–11.2] | <.05 |

| Roubenoff et al., 1991 (47) | incident | Excessive weight gain ≥2.7 kg | RR of incident gout, 2.07 | .02 |

|

Diabetes | ||||

| Chen et al., 2007 (15) | Incident | Type 2 diabetes vs. none | RR of gout flare 19–44 yrs, 0.99 [0.78–1.27] 45–64 yrs, 1.02 [0.91–1.14] ≥65 yrs, 2.09 [1.52–2.88] |

|

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | Prevalent | Type 2 diabetes mellitus (yes vs. no) | Not specified | 0.52 |

| Suppiah et al., 2008 (52) | prevalent | Type 2 Diabetes vs. no diabetes | OR of prevalent gout, 4.4; [2.1–9.6] | |

| Anagnostopoulos et al., 2010 (7) | Prevalent | Diabetes Mellitus vs. no diabetes | OR of prevalent gout 2.63 [1.35–5.14] | <.01 |

|

Renal disease including renal insufficiency | ||||

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | Prevalent | Renal calculi vs. no renal calculi | Not specified | <.0001 |

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | Prevalent | Renal insufficiency (yes vs. no) | Not specified | 0.68 |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | Prevalent | Creatinine ≥2 mg/dl vs. <2 | OR of gout flare 2.9[.9–9.4] | |

| Suppiah et al., 2008 (52) | prevalent | Impaired renal function (yes vs. no) | OR of prevalent gout, 1.2 [1.1–1.4] | |

| Li-Yu et al., 200 (42) | Prevalent | Serum creatinine levels | Not specified | |

| Andracco et al., 2009 (8) | Prevalent | Renal stones vs. no renal stones | OR for acute gout, 13.3 [1.1–158.3] | .064 |

| Padang et al., 2006 (45) | Prevalent | Nephrolithiasis (yes vs. no) | OR of gout flare 3.45 [.43–8.56] | < .005 |

|

Hyperlipidemia | ||||

| Chen et al.,2007 (15) | prevalent | Hypertriglyceridemia vs. none | RR of gout flare: 19–44 years, 2.18 [1.72, 2.75] 45–64 years, 1.59 [1.33–1.89] ≥65 years, 4.51 [2.70–7.53] |

|

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | Prevalent | Hypercholesterolemia (yes vs. no) | Not specified | 0.0003 |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | Prevalent | Hypertriglyceridemia (yes vs. no) | OR of gout flare 1.9 [1.0–3.7] | |

| Chang et al., 1997 (13) | Prevalent | Hypercholesterolemia (yes vs. no) | OR of gout flare 1.5 [.6–3.6] | |

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | prevalent | Hypercholesterolemia (yes vs. no) | RR of gout flare: 19–44 years, 1.73 [1.29–2.32] 45–64 years, 1.44 [1.19–1.74] ≥65 years, 1.17 [.90–1.53] |

|

| Chen et al., 2003 (14) | Prevalent | Hypertriglyceridemia (yes vs. no) | Not specified | <.0001 |

| Prior et al., 1987 (46) | incident | Hypercholesterolemia (yes vs. no) | RR Not specified | <0.05 |

| Suppiah et al., 2008 (52) | prevalent | Hypertriglyceridemia (yes vs. no) | OR of prevalent gout, 2.2 [1.0–4.7] | p<.05 |

| Padang et al., 2006 (45) | Prevalent | Hypertriglyceridemia (yes vs. no) | OR of gout flare 70.4 [34.89–144.25] | <.0001 |

|

Menopause, Hormone Use and Cancer | ||||

| Hak et al., 2008 (33) | incident | natural and surgical menopause vs. premenopausal patients | Serum urate higher by .36 [.14 to .57] | |

| Hak et al., 2010 (34) | incident | Menopause at <45yrs vs. 50–54 yrs | RR of incident gout, 1.62 [1.12–2.33] | |

Hyperuricemia is perhaps the most common and well-studied risk factor for developing gout; it is also one of the causal pathways of gout, so some may argue that it is the common channel to gout and, therefore, not a risk factor. Hypertension was consistently associated with higher risk of incident gout and more flares in those with prevalent gout (Table 5). Higher body mass index was a risk factor for gout and overweight and obese patients were at significantly higher risk of incident gout. Diabetics were at higher risk of incident gout and of gout flares in patients with prevalent gout, with 4 studies providing evidence. Renal insufficiency, but neprolithiasis, was not associated with higher risk of gout flares. Both hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia were associated with significantly increased risk of gout flares in patients with prevalent gout.

Gout is extremely uncommon in premenopausal women, but postmenopausal women are at risk. In a study conducted by Hak et al., 2010 studied physician-diagnosed incident gout among 92,535 women prospectively followed in the Nurse’s Health Study (34). The study examined the relationship between menopause, postmenopausal hormone use and risk of gout. Study findings indicated that menopause, especially at an earlier age, increased the risk of gout in women, whereas post menopausal hormone therapy modestly reduced risk of gout (RR=0.82, 95% CI: .70-.96). Friedman et al (2007) conducted a retrospective multi-institutional review of 411 consecutive laparoscopic gastric bypass patients and identified those that had experienced incident postoperative gouty attacks after undergoing bariatric surgery (31). Study findings illustrate that 33.3% of patients with a previous history of gout in this study population developed an acute gout attack postoperatively (31).

In summary, the current evidence suggests that there are several risk factors for incident gout and gout flares in patients with gout. Most of the associations have been examined in at least one or more well-designed study, although further study in different populations can verify these associations. Several comorbidity risk factors are usually coexisting in patients, most common example being hypertension, renal insufficiency, heart disease and diabetes. It is difficult to tease the individual effects of these illnesses and it is conceivable that several of these risk factors mediate their effects through common pathways of inflammation and/or renal mechanisms of urate excretion.

Primary and Secondary Prevention of Gout

We did not find any articles that focused on primary prevention, and four articles were focused on secondary prevention (42)(38)(40)(47).

One article that focused on secondary prevention focused on hyperuricemia and the maintenance of serum urate levels. Li-Yu et al, (2001) conducted a prospective study, at the Philadelphia VA medical center, to determine if lowering of serum urate levels to 6 mg/dl or if a longer duration of lowered serum urate levels will result in depletion of urate crystals and prevent further attacks of gout (42). Study findings indicated that keeping serum urate levels at ≤ 6mg/dl, led to the prevention of future acute gouty flares.

Another article described the clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with gout during the post-surgical period. Kang et al. (2008) conducted a case control study which showed that the site of a recurrent gout flare had a preference for the previously affected site (38). A history of cancer surgery, elevated serum urate levels of ≥ 9 mg/dl, and failure to administer colchicine prophylaxis were all found to be significant risk factors for postsurgical gout. Therefore, an adequate control of pre-surgical serum urate levels and/or the administration of a colchicine prophylactic may prevent postsurgical acute gout.

Lin et al. (2000) conducted a prospective study to examine the association of serum uric acid and other risk factors related to the development of gout flares (40). Findings illustrated that excessive alcohol consumption, especially if sporadic, was the most important risk factor for the development of gout even when serum uric acid concentrations were below 8mg/dl. This study suggested that maintenance of serum urate levels below 8mg/dl was key to secondary prevention of gout flares.

Lastly, Roubenoff et al. studied the incidence and risk factors for gout in white men (47). Study findings indicate that obesity, excessive weight gain and hypertension are significant risk factors for the development of gout. Consequently, prevention of obesity and hypertension may decrease the incidence of gout.

Limitations

Our search was limited to articles since 1950, and we were unable to capture epidemiological and clinical studies examining risk factors for gout prior to 1950. The epidemiology of gout may be changing with the obesity epidemic and therefore the estimates presented here from the literature review may not be precise and applicable in the future. For most studies, ACR classification criteria were used, but others used alternate definitions for gout; this could have lead to misclassification bias in the included studies. No validated definition of gout flare was used in previous studies. Gout flare definitions were not provided in most studies and defined ambiguously in others, which may have lead to misclassification bias. There is an ongoing initiative for the development of validated gout flare definition, which may help to avoid this limitation in future.

Conclusions

We performed a systematic review of the literature to summarize published data on the risk factors and prevention of gout. Several comorbidities, diet, medications and alcohol intake increase the risk for incident gout and/or gout flares in patients with known gout. Studies focused on primary and secondary prevention of gout were scarce. Primary and secondary prevention studies are needed to identify whether prevention of gout is achievable. Risk factors should be often taken into consideration in the medical management of patients with gout, since several risk factors (alcohol, obesity, thiazide diuretics etc.) are potentially modifiable, of which at least some are amenable to behavioral and other interventions.

Supplementary Material

Take Home Messages.

Alcohol consumption increased the risk of incident gout, especially higher intake of beer and hard liquor.

Several dietary factors including higher intake of meat intake, seafood intake, sugar sweetened soft drinks, and foods high in fructose increased the risk of incident gout.

Dairy intake, folate intake and coffee consumption were each associated with lower risk of incident gout and in some cases lower rate of gout flares.

Among medications, consistent evidence exists for thiazide and loop diuretics to be associated with higher risk of incident gout and higher rate of gout flares.

Hypertension, renal insufficiency, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, hyperuricemia, diabetes, obesity and early menopause were each associated with higher risk of incident gout and/or gout flares.

Acknowledgements

We thank Louise Falzon, of the Cochrane Library, for performing and updating the search for this systematic review and April DeMedicis, of the Birmingham VA Medical Center, for reviewing titles and abstracts prior to conducting the full text review as well as assisting with the data abstraction process.

Grant support: This material is the result of work supported with the resources and the use of facilities at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, Alabama, USA.

Footnotes

Financial Conflict: There are no financial conflicts related to this work. J.A.S. has received speaker honoraria from Abbott; research and travel grants from Allergan, Takeda, Savient, Wyeth and Amgen; and consultant fees from Savient, URL pharmaceuticals and Novartis.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

This study did not require Institutional Review Board since it did not include human subject research.

References

- 1.Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. Is gout associated with reduced quality of life? A case-control study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007 Sep;46(9):1441–1444. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh JA, Strand V. Gout is associated with more comorbidities, poorer health-related quality of life and higher healthcare utilisation in US veterans. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Sep;67(9):1310–1316. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.081604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace KL, Riedel AA, Joseph-Ridge N, Wortmann R. Increasing prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia over 10 years among older adults in a managed care population. J Rheumatol. 2004 Aug;31(8):1582–1587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, Decker JL, McCarty DJ, Yu TF. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977 Apr;20(3):895–900. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbott KC, Kimmel PL, Dharnidharka V, Oglesby RJ, Agodoa LY, Caillard S. New-onset gout after kidney transplantation: incidence, risk factors and implications. Transplantation. 2005 Nov 27;80(10):1383–1391. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000188722.84775.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Cen-Piste JC, Medina-Escobedo M, Villanueva-Jorge S. Factors associated with musculoskeletal disability and chronic renal failure in clinically diagnosed primary gout. J Rheumatol. 2005 Oct;32(10):1923–1927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anagnostopoulos I, Zinzaras E, Alexiou I, Papathanasiou AA, Davas E, Koutroumpas A, et al. The prevalence of rheumatic diseases in central Greece: a population survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-98. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andracco R, Zampogna G, Parodi M, Cimmino MA. Risk factors for gouty dactylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;27(6):993–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annemans L, Spaepen E, Gaskin M, Bonnemaire M, Malier V, Gilbert T, et al. Gout in the UK and Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Jul;67(7):960–966. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arromdee E, Michet CJ, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Epidemiology of gout: is the incidence rising. J Rheumatol. 2002 Nov;29(11):2403–2406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhole V, de Vera M, Rahman MM, Krishnan E, Choi H. Epidemiology of gout in women: Fifty-two-year followup of a prospective cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Apr;62(4):1069–1076. doi: 10.1002/art.27338. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brauer GW, Prior IA. A prospective study of gout in New Zealand Maoris. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978 Oct;37(5):466–472. doi: 10.1136/ard.37.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang SJ, Ko YC, Wang TN, Chang FT, Cinkotai FF, Chen CJ. High prevalence of gout and related risk factors in Taiwan’s Aborigines. J Rheumatol. 1997 Jul;24(7):1364–1369. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen SY, Chen CL, Shen ML, Kamatani N. Trends in the manifestations of gout in Taiwan. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003 Dec;42(12):1529–1533. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S-Y, Chen C-L, Shen M-L. Manifestations of metabolic syndrome associated with male gout in different age strata. Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Sep;26(9):1453–7. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0527-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Apr 11;165(7):742–748. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.742. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet. 2004 Apr 17;363(9417):1277–1281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16000-5. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004 Mar 11;350(11):1093–1103. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035700. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi HK, Curhan G. Independent impact of gout on mortality and risk for coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2007 Aug 21;116(8):894–900. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703389. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi HK, Curhan G. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and serum uric acid level: the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Jun 15;57(5):816–821. doi: 10.1002/art.22762. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. Bmj. 2008 Feb 9;336(7639):309–312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39449.819271.BE. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi HK, De Vera MA, Krishnan E. Gout and the risk of type 2 diabetes among men with a high cardiovascular risk profile. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008 Oct;47(10):1567–1570. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken305. [Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi HK, Gao X, Curhan G. Vitamin C intake and the risk of gout in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 9;169(5):502–507. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.606. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Jun;56(6):2049–2055. doi: 10.1002/art.22712. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi JWJ, Ford ES, Gao X, Choi HK. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jan 15;59(1):109–116. doi: 10.1002/art.23245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou CT, Lai JS. The epidemiology of hyperuricaemia and gout in Taiwan aborigines. Br J Rheumatol. 1998 Mar;37(3):258–262. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen SD, Kimmel PL, Neff R, Agodoa L, Abbott KC. Association of incident gout and mortality in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Nov;19(11):2204–2210. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111256. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creighton S, Miller R, Edwards S, Copas A, French P. Is ritonavir boosting associated with gout. Int J STD AIDS. 2005 May;16(5):362–364. doi: 10.1258/0956462053888907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elliot AJ, Cross KW, Fleming DM. Seasonality and trends in the incidence and prevalence of gout in England and Wales 1994–2007. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Nov;68(11):1728–1733. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096693. [Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fam AG, Stein J, Rubenstein J. Gouty arthritis in nodal osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996 Apr;23(4):684–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman JE, Dallal RM, Lord JL. Gouty attacks occur frequently in postoperative gastric bypass patients. Surg. [Multicenter Study] 2008 Jan-Feb;4(1):11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurwitz JH, Kalish SC, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ, Monane M, Mogun H, et al. Thiazide diuretics and the initiation of anti-gout therapy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997 Aug;50(8):953–959. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00101-7. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hak AE, Choi HK. Menopause, postmenopausal hormone use and serum uric acid levels in US women--the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(5):R116. doi: 10.1186/ar2519. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hak AE, Curhan GC, Grodstein F, Choi HK. Menopause, postmenopausal hormone use and risk of incident gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Jul;69(7):1305–1309. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.109884. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hochberg MC, Thomas J, Thomas DJ, Mead L, Levine DM, Klag MJ. Racial differences in the incidence of gout. The role of hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 May;38(5):628–632. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunter DJ, York M, Chaisson CE, Woods R, Niu J, Zhang Y. Recent diuretic use and the risk of recurrent gout attacks: the online case-crossover gout study. Erratum appears in J Rheumatol. 2006 Aug;33(8):1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; J Rheumatol. 2006 Jul;33(7):1341–1345. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janssens HJEM, van de Lisdonk EH, Janssen M, van den Hoogen HJM, Verbeek ALM. Gout, not induced by diuretics. A case-control study from primary care. 2007 Feb 24;151(8):472–477. [Reprint in Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd PMID: 17378304] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Aug;65(8):1080–1083. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.040360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang EH, Lee EY, Lee YJ, Song YW, Lee EB. Clinical features and risk factors of postsurgical gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Sep;67(9):1271–1275. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.078683. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ko YC, Wang TN, Tsai LY, Chang FT, Chang SJ. High prevalence of hyperuricemia in adolescent Taiwan aborigines. J Rheumatol. 2002 Apr;29(4):837–842. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin KC, Lin HY, Chou P. The interaction between uric acid level and other risk factors on the development of gout among asymptomatic hyperuricemic men in a prospective study. J Rheumatol. 2000 Jun;27(6):1501–1505. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin KC, Lin HY, Chou P. Community based epidemiological study on hyperuricemia and gout in Kin-Hu, Kinmen. J Rheumatol. 2000 Apr;27(4):1045–1050. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li-Yu J, Clayburne G, Sieck M, Beutler A, Rull M, Eisner E, et al. Treatment of chronic gout Can. we determine when urate stores are depleted enough to prevent attacks of gout. J Rheumatol. 2001 Mar;28(3):577–580. [Clinical Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyu L-C, Hsu C-Y, Yeh C-Y, Lee M-S, Huang S-H, Chen C-L. A case-control study of the association of diet and obesity with gout in Taiwan. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Oct;78(4):690–701. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.690. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mijiyawa M, Oniankitan O. Risk factors for gout in Togolese patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67(5):441–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Padang C, Muirden KD, Schumacher HR, Darmawan J, Nasution AR. Characteristics of chronic gout in Northern Sulawesi, Indonesia. J Rheumatol. 2006 Sep;33(9):1813–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prior IA, Welby TJ, Ostbye T, Salmond CE, Stokes YM. Migration and gout: the Tokelau Island migrant study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Aug 22;295(6596):457–461. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6596.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roubenoff R, Klag MJ, Mead LA, Liang KY, Seidler AJ, Hochberg MC. Incidence and risk factors for gout in white men. Jama. 1991 Dec 4;266(21):3004–3007. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shibolet O, Elinav E, Ilan Y, Safadi R, Ashur Y, Eid A, et al. Reduced incidence of hyperuricemia, gout, and renal failure following liver transplantation in comparison to heart transplantation: a long-term follow-up study. Transplantation. 2004 May 27;77(10):1576–1580. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000128357.49077.19. [Comparative Study] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with antihyperuricemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Jun 15;51(3):321–325. doi: 10.1002/art.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shulten P, Thomas J, Miller M, Smith M, Ahern M. The role of diet in the management of gout: a comparison of knowledge and attitudes to current evidence. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2009 Feb;22(1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2008.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stamp L, Ha L, Searle M, O’Donnell J, Frampton C, Chapman P. Gout in renal transplant recipients. Nephrology. 2006 Aug;11(4):367–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suppiah R, Dissanayake A, Dalbeth N. High prevalence of gout in patients with Type 2 diabetes: male sex, renal impairment, and diuretic use are major risk factors. N Z Med J. 2008 Oct 3;121(1283):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tikly M, Bellingan A, Lincoln D, Russell A. Risk factors for gout: a hospital-based study in urban black South Africans. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1998 Apr;65(4):225–231. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams PT. Effects of diet, physical activity and performance, and body weight on incident gout in ostensibly healthy, vigorously active men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 May;87(5):1480–1487. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1480. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu EQ, Patel PA, Mody RR, Yu AP, Cahill KE, Tang J, et al. Frequency, risk, and cost of gout-related episodes among the elderly: does serum uric acid level matter. J Rheumatol. 2009 May;36(5):1032–1040. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080487. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu TF, Gutman AB. Efficacy of colchicine prophylaxis in gout. Prevention of recurrent gouty arthritis over a mean period of five years in 208 gouty subjects. Ann Intern Med. 1961 Aug;55:179–192. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-55-2-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Woods R, Chaisson CE, Neogi T, Niu J, McAlindon TE, et al. Alcohol consumption as a trigger of recurrent gout attacks. Am J Med. 2006 Sep;119(9):800.e13–800.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.020. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Febuxostat: new drug. Hyperuricaemia: risk of gout attacks. Prescrire Int. 2009 Apr;18(100):63–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al-Arfaj AS. Hyperuricemia in Saudi Arabia. Rheumatol Int. 2001 Feb;20(2):61–64. doi: 10.1007/s002960000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gutman AB, Yu TF. Prevention and treatment of chronic gouty arthritis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1955 Mar 26;157(13):1096–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02950300024005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hanly JG, Skedgel C, Sketris I, Cooke C, Linehan T, Thompson K, et al. Gout in the elderly--a population health study. J Rheumatol. 2009 Apr;36(4):822–830. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080768. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hutton I, Gamble G, Gow P, Dalbeth N. Factors associated with recurrent hospital admissions for gout: a case-control study. J. 2009 Sep;15(6):271–274. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181b562f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson S. Effect of gradual accumulation of iron, molybdenum and sulfur, slow depletion of zinc and copper, ethanol or fructose ingestion and phlebotomy in gout. Med Hypotheses. 1999 Nov;53(5):407–412. doi: 10.1054/mehy.1999.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klein R, Klein BEK, Tomany SC, Cruickshanks KJ. Association of emphysema, gout, and inflammatory markers with long-term incidence of age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003 May;121(5):674–678. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.5.674. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kot TV, Day RO, Brooks PM. Preventing acute gout when starting allopurinol therapy. Colchicine or NSAIDs. Med J Aust. 1993 Aug 2;159(3):182–184. [Comparative Study] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kramer HJ, Choi HK, Atkinson K, Stampfer M, Curhan GC. The association between gout and nephrolithiasis in men: The Health Professionals’ Follow-Up Study. Kidney Int. 2003 Sep;64(3):1022–1026. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.t01-2-00171.x. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kramer HM, Curhan G. The association between gout and nephrolithiasis: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 1988–1994. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002 Jul;40(1):37–42. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33911. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Talbott JH. Treating gout: successful methods of prevention and control. Postgrad Med. 1978 May;63(5):175–180. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1978.11714839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsutsumi Z, Yamamoto T, Takahashi S, Moriwaki Y, Yamakita J, Nasako Y, et al. Atherogenic risk factors in patients with gout. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;431:69–72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5381-6_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dalbeth N, Wong S, Gamble GD, Horne A, Mason B, Pool B, et al. Acute effect of milk on serum urate concentrations: a randomised controlled crossover trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Sep;69(9):1677–1682. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.124230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dalbeth N, Gracey E, Pool B, Callon K, McQueen FM, Cornish J, et al. Identification of dairy fractions with anti-inflammatory properties in models of acute gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Apr;69(4):766–769. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.113290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu TF, Gutman AB. Study of the paradoxical effects of salicylate in low, intermediate and high dosage on the renal mechanisms for excretion of urate in man. J Clin Invest. 1959 Aug;38(8):1298–1315. doi: 10.1172/JCI103905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Caspi D, Lubart E, Graff E, Habot B, Yaron M, Segal R. The effect of mini-dose aspirin on renal function and uric acid handling in elderly patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Jan;43(1):103–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<103::AID-ANR13>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.