Significance

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) started their incredible, colorful journey in bioimaging and biomedicine with the extraction and purification of GFP from the Pacific jellyfish Aequorea victoria more than 50 years ago. Recently, an expanded palette of genetically encodable Ca2+-sensing FPs have paved the way to image neural activities and important biological processes where Ca2+ is the ubiquitous messenger. To unravel the molecular choreography of FPs engineered for visualizing Ca2+ movement, we study the embedded chromophore upon photoexcitation and monitor its subsequent excited-state structural evolution with femtosecond Raman spectroscopy. The vivid insights on H-bonding network and functional roles played by strategic mutations provide a deep understanding of excited-state processes in biology and will guide future bioengineering efforts toward better biosensors.

Keywords: calcium-sensing fluorescent protein, femtosecond Raman spectroscopy, fluorescence modulation mechanism, molecular movie

Abstract

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) have played a pivotal role in bioimaging and advancing biomedicine. The versatile fluorescence from engineered, genetically encodable FP variants greatly enhances cellular imaging capabilities, which are dictated by excited-state structural dynamics of the embedded chromophore inside the protein pocket. Visualization of the molecular choreography of the photoexcited chromophore requires a spectroscopic technique capable of resolving atomic motions on the intrinsic timescale of femtosecond to picosecond. We use femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy to study the excited-state conformational dynamics of a recently developed FP-calmodulin biosensor, GEM-GECO1, for calcium ion (Ca2+) sensing. This study reveals that, in the absence of Ca2+, the dominant skeletal motion is a ∼170 cm−1 phenol-ring in-plane rocking that facilitates excited-state proton transfer (ESPT) with a time constant of ∼30 ps (6 times slower than wild-type GFP) to reach the green fluorescent state. The functional relevance of the motion is corroborated by molecular dynamics simulations. Upon Ca2+ binding, this in-plane rocking motion diminishes, and blue emission from a trapped photoexcited neutral chromophore dominates because ESPT is inhibited. Fluorescence properties of site-specific protein mutants lend further support to functional roles of key residues including proline 377 in modulating the H-bonding network and fluorescence outcome. These crucial structural dynamics insights will aid rational design in bioengineering to generate versatile, robust, and more sensitive optical sensors to detect Ca2+ in physiologically relevant environments.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) first emerged as a revolutionary tool for bioimaging and molecular and cellular biology about 20 years ago (1–3), and the quest to discover and engineer biosensors with improved and expanded functionality has yielded exciting advances. Recently, the color palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ sensors for optical imaging (the GECO series) has been expanded to include blue, improved green, red intensiometric, and emission ratiometric sensors (4–7). The GECO proteins belong to the GCaMP family of Ca2+ sensors that are chimeras of a circularly permutated (cp)GFP, calmodulin (CaM), and a peptide derived from myosin light chain kinase (M13) (8). The CaM unit undergoes large-scale structural changes upon Ca2+ binding as it wraps around M13. These changes, especially at the interfacial region where CaM interacts with cpGFP, allosterically alter the local environment of the tyrosine-derived chromophore and lead to dramatic fluorescence change in the presence of Ca2+ (9, 10). Because GCaMP and GECO proteins are genetically encodable, show sensitivity to physiologically relevant Ca2+ concentrations, and respond to Ca2+ concentration changes rapidly, they have gained increasing popularity for in vivo imaging of Ca2+ in neural and olfactory cells (11–13).

Among the engineered GECO proteins, GEM-GECO1 is an intriguing case with the serine–tyrosine–glycine (SYG) derived chromophore (4). Upon ultraviolet (UV) excitation it fluoresces green in the absence of Ca2+ but blue upon Ca2+ binding with a Kd of 340 nM. This dual-emission behavior is unique among ratiometric Ca2+-sensing FPs as well as the few reported pH-dependent dual-emission GFP variants, which typically require a threonine–tyrosine–glycine (TYG) chromophore to keep the nearby glutamate largely protonated (14, 15). Dual emission is particularly useful for imaging in vivo because the signal color change is a direct consequence of analyte concentration. There remains room to further improve GEM-GECO1 because it has a low quantum yield and decreased dynamic range in vivo (5).

The advanced imaging capabilities of the GECO series have been explored (4, 5, 7), but few spectroscopic studies exist for these unique Ca2+ sensors. In contrast, spectroscopy on wild-type (wt)GFP included infrared pump probe (16), time-resolved fluorescence (17–19), transient infrared (20, 21), and femtosecond Raman spectroscopy (22), as well as computational studies (23–25), providing a fairly complete picture of the photophysical and photochemical steps leading to green fluorescence (26, 27). In the electronic ground state (GS), wtGFP exists as a mixture of neutral chromophore (A, ∼400 nm peak absorbance) and a small population of anionic chromophore (B, ∼475 nm peak absorbance; Fig. 1B). Emission from the excited state of either form (A* at ∼460 nm and B* at ∼500 nm, respectively) is possible. The main emission pathway upon 400-nm excitation involves excited-state proton transfer (ESPT) from A* on a picosecond timescale to form the intermediate green fluorescent state (I*). We hypothesize that ESPT occurs in the Ca2+-free state of GEM-GECO1, but upon Ca2+ binding ESPT is disrupted and blue fluorescence occurs from A* (28). In this work, we aim to elucidate the ESPT mechanism of GEM-GECO1 as a function of the chromophore environment, using time-resolved femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy (FSRS). Previous results (22) identified a low-frequency skeletal motion facilitating ESPT in wtGFP that provides guidance to unravel the chromophore dynamics in a flexible CaM–GFP complex. In the absence of a GEM-GECO1 crystal structure, we will compare spectroscopic signatures of the Ca2+-free/bound proteins at equilibrium in conjunction with site-specific mutagenesis and molecular dynamics simulations. We then infer how the local environment influences the chromophore structural evolution on the electronically excited state and leads to distinct fluorescence hues.

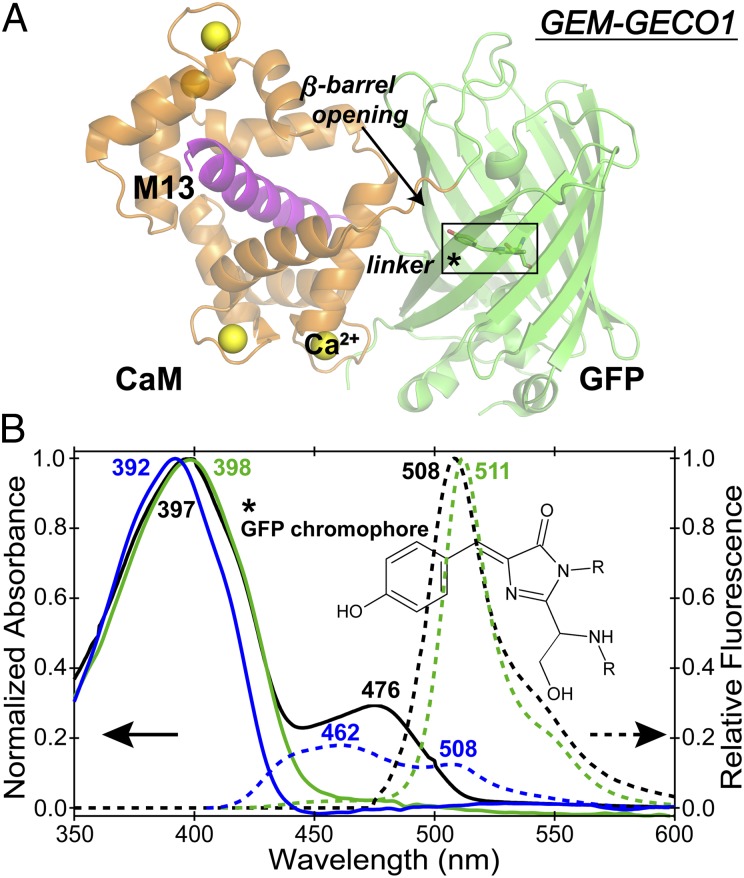

Fig. 1.

Schematic structure and electronic spectroscopy of the M13-cpGFP-CaM chimera, GEM-GECO1. (A) The Ca2+-bound GCaMP2 structure (PDB ID 3EVR) for illustration purposes is shown with the GFP β-barrel in green, CaM in orange, the M13 peptide in magenta, and the Ca2+ bound to CaM in yellow. The black arrow indicates the β-barrel opening. The autocyclized SYG chromophore is highlighted by a black box with an asterisk and shown in Inset. (B) Normalized absorption and relative emission spectra of Ca2+-free (green solid and dashed lines) and Ca2+-bound GEM-GECO1 (blue solid and dashed lines, respectively). The corresponding spectra in wtGFP are shown in black. Blue fluorescence from Ca2+-bound protein (peak at 462 nm) is broad and asymmetric relative to the sharp green fluorescence of the Ca2+-free protein (peak at 511 nm).

Results

Electronic Spectroscopy Shows Distinctive Features of GEM-GECO1 ±Ca2+.

The UV/visible spectrum of Ca2+-free protein resembles wtGFP with ∼398 nm absorption maximum and a 511-nm emission peak (Fig. 1B). Upon Ca2+ binding the protein absorption/emission maximum blueshifts to 392/462 nm, indicating that the excited-state (ES; S1) potential energy surface (PES) of the chromophore is modified even though Ca2+ binding occurs in the remote CaM domain. In contrast to wtGFP, no significant B state absorbance near 476 nm exists for GEM-GECO1, so the protein pocket strongly favors the neutral chromophore (A state) in GS (S0). The small shoulder at ∼508 nm for the Ca2+-bound protein (4, 14) is consistent with the ensemble measurement and the intrinsic inhomogeneity of the protein complex.

Comparison of GS and ES Spectra Infers the Ca2+-Binding Effect.

The GS Raman spectra of GEM-GECO1 both with and without Ca2+ are similar, indicative of a largely conserved protein pocket before photoexcitation (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). Raman bands at 1,603 and 1,565 cm−1 are markers for the neutral chromophore (29). Upon photoexcitation, GEM-GECO1 without/with Ca2+ displays key changes starting at time zero: the 1,247/1,250 cm−1 GS C–O stretching mode blueshifts to 1,265 cm−1; the 1,155/1,157 cm−1 mode redshifts to 1,138/1,147 cm−1; and the 1,174 cm−1 mode blueshifts to 1,180 cm−1 (Table S1). The 1,155/1,157 cm−1 GS shoulder is significantly enhanced in A*, indicative of the mode assignment to a largely protonated GS chromophore that experiences electronic redistribution and enhanced polarizability in ES. Moreover, the mode redshift magnitude matches ES calculation (TD-DFT, time-dependent density functional theory) results (30) on a localized phenol H-rocking mode, reflecting a larger extent of S0→S1 electronic redistribution in the Ca2+-free protein than the Ca2+-bound one across the conjugated ring system. In contrast, the 1,174 cm−1 mode shows a small blueshift, consistent with a more delocalized ring H-rocking motion of a partially deprotonated chromophore in GS that has stronger Raman intensity. Also, neither the Ca2+-free or -bound protein has a ∼1,300 cm−1 peak in GS (Table S2), but this mode emerges in A* and manifests quite different dynamics in the two species (see below). The mode enhancement is attributed to the increased polarizability of the ES chromophore (31).

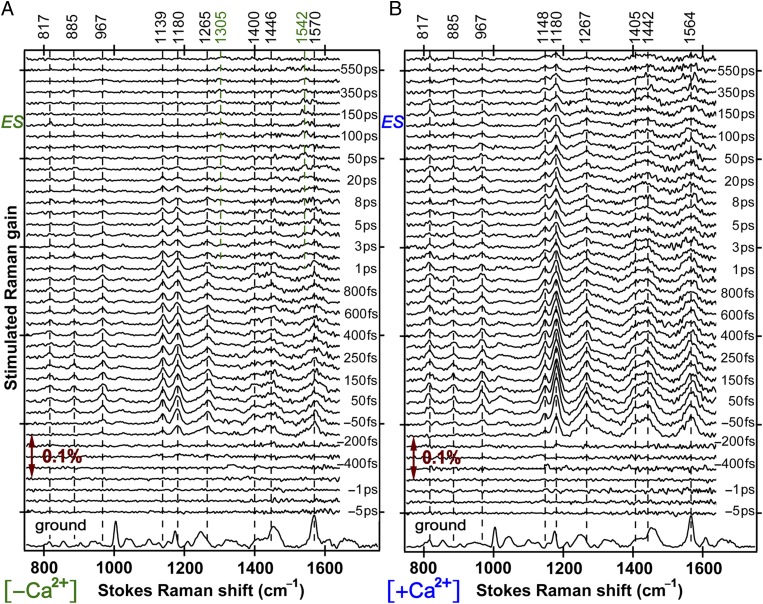

Fig. 2.

Time-resolved excited-state FSRS spectra of (A) Ca2+-free and (B) Ca2+-bound GEM-GECO1 from −5 to 650 ps following 400-nm photoexcitation. The Raman pump is at ∼800 nm. The buffer-subtracted protein spectrum is plotted at the bottom for comparison with the GS-subtracted ES spectra from ca. 750 to 1,700 cm−1. The double-headed arrow shows the Raman gain magnitude of 0.1%. Vibrational modes discussed are indicated with vertical dashed lines and frequency labels. On a much longer timescale, the fluorescence lifetime of the Ca2+-free (-bound) GEM-GECO1 is ca. 4 (<1) ns, and the reported lifetime for wtGFP green fluorescence is ca. 3–4 ns (17, 18, 27).

Time-resolved FSRS spectra in Fig. 2 offer unprecedented insights into ES structural dynamics of Ca2+-free and -bound GEM-GECO1 across a spectral window spanning over 1,200 cm−1 on the intrinsic timescale for relevant photophysics and photochemistry. It is immediately apparent that the Ca2+-free protein resembles wtGFP (22), showing a rapid decay of A* modes and a concomitant increase of I* modes at 1,305 and 1,540 cm−1, with the latter mode redshifted from the 1,570 cm−1 mode. In the Ca2+-bound protein, the A* modes persist throughout the entire 650-ps sampling window without significant frequency change, confirming that blue fluorescence (Fig. 1B) is directly emitted from a trapped A* state.

Transient Dynamics of Vibrational Marker Bands in A* and I* Report on PES.

Fitting results and mode assignments for ES peaks (Table S1) and relevant GS modes are tabulated to show the effect of S0→S1 transition on the normal modes (Table S2). The kinetic plot of the strongest A* mode intensity at 1,180 cm−1 (Fig. 3A) shows an ultrafast rising component within the 140-fs cross-correlation time and two decay components of 730 (630) fs and 27 (592) ps for the Ca2+-free (bound) protein. The first decay time constant is similar to wtGFP in H2O or D2O at ∼700 or 600 fs (22), consistent with the initial Franck–Condon (FC) dynamics seeing minor proton motions. Instead, vibronic relaxation occurs in A* despite the fate of the wavepacket when it reaches the lower portion of PES. Therein, the Ca2+-free protein modes exhibit a time constant of 30–40 ps attributed to ESPT, much longer than the 5–9 ps counterpart for wtGFP in water (22, 26). In contrast, the Ca2+-bound protein shows characteristic mode decay on the 500–900 ps timescale, revealing that ESPT is essentially blocked and blue emission from A* dominates (17, 19).

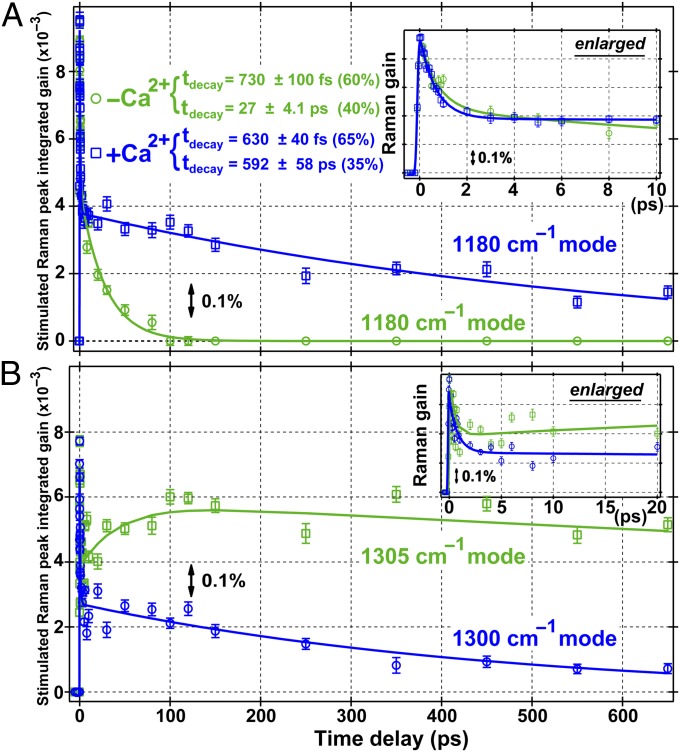

Fig. 3.

Time evolution of two excited-state vibrational modes for both Ca2+-free (green) and bound (blue) GEM-GECO1 up to 650 ps following 400-nm photoexcitation. (A) The 1,180 cm−1 A* mode shows biexponential relaxation but with much lengthened long-time decay with Ca2+. The enlarged dynamics plot up to 10 ps exhibits a similar initial decay. The −Ca2+ peak is normalized to the stronger +Ca2+ peak with a scaling factor of 2. (B) The 1,305/1,300 cm−1 mode in Ca2+-free/bound protein shows distinct dynamics. There are overlapping A* and I* modes in the Ca2+-free protein and the dominant ESPT timescale is ∼30 ps. The −Ca2+ peak is normalized to the stronger +Ca2+ peak with a scaling factor of 3. Error bars, SD of the Gaussian-fitted peak area (n = 3). Solid lines are fits to data points, and the peak integrated gain is plotted to better represent the mode intensity due to small variations of the broad ES peak width.

Kinetic analysis of the nascent 1,305 cm−1 ES mode (Fig. 3B) reports on structural dynamics changes induced by Ca2+. It involves bridge-H rocking and is particularly sensitive to electronic distribution across the two rings of the chromophore (22). Without Ca2+, this mode is much weaker than the nearby 1,265 cm−1 mode during the first 4 ps and is from A* (Fig. 2A); then the mode starts to grow with I* formation. The peak fit to three exponentials yields an initial decay with ∼540 fs time constant, a rising component of ∼31 ps, and a second decay constant of ∼4.1 ns. The intermediate time constant matches ESPT timescale (Table S1), suggesting a direct A*→I* transition. In contrast, although the Ca2+-bound protein also exhibits the 1,300 cm−1 mode relaxation, the dynamics are characterized by a biexponential decay with time constants of ca. 700 fs and 472 ps, indicative of vibronic relaxation within a confined A* state.

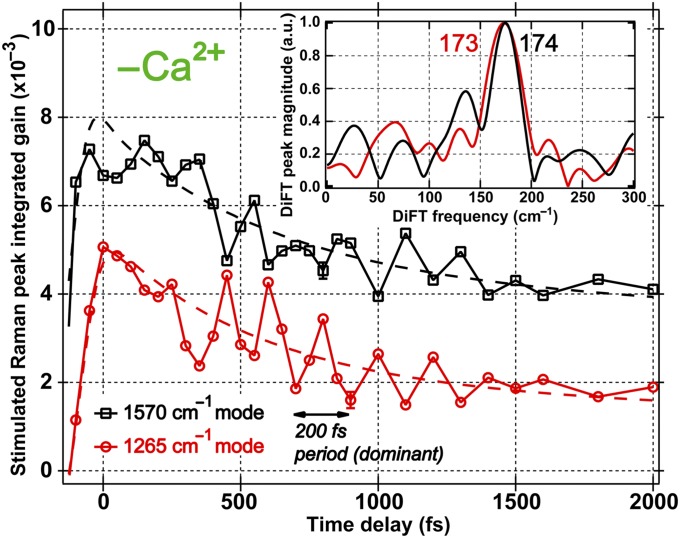

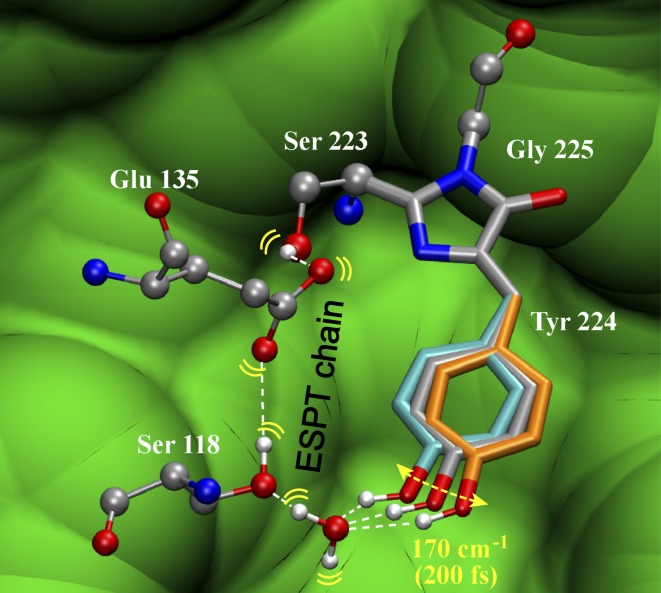

Remarkably, several modes manifest spectral oscillations (i.e., quantum beating) promptly following photoexcitation. The 819; 885; 967; 1,180; 1,265; 1,400; 1,446; and 1,570 cm−1 modes in the Ca2+-free protein all exhibit a reproducible ∼200 fs period oscillation in the peak intensities and frequencies (Fig. S2), wherein the 1,265 cm−1 C–O stretch is antiphase with the 1,570 cm−1 C = N stretch (Fig. 4). Discrete Fourier transform (DiFT) of the quantum beats after removing the broad incoherent component reveals a dominant ∼170 cm−1 peak (Fig. 4, Inset, and Fig. S2, Inset) that corresponds to an in-plane phenol-ring rocking motion about the bridge carbon. The collective nature of the skeletal motion leads to similar mode frequency in S0 and S1 (22, 32). In contrast, the Ca2+-bound protein exhibits some oscillations within 2 ps, but without a dominant modulating component; several low-frequency modes between 100 and 300 cm−1 of roughly equal intensity are present (Fig. S3). It is conceivable that multiple skeletal modes project onto the PES and contribute to initial energy dissipation but provide no effective driving force for ESPT.

Fig. 4.

Temporal evolution and quantum beats of the 1,265 and 1,570 cm−1 excited-state vibrational modes of the Ca2+-free GEM-GECO1 following 400-nm photoexcitation. The two marker band intensities during the first 2 ps manifest an oscillatory pattern with a 200-fs period, whereas the 1,265 cm−1 phenolic C–O stretch (red) is anti-phase with the imidazolinone C = N stretch (black) at 1,570 cm−1. Inset shows normalized DiFT spectra of the coherent residuals after removing the incoherent exponential fits (dashed lines), which manifests a prominent ∼170 cm−1 mode.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Site-Directed Mutagenesis of GEM-GECO1 Pinpoint Specific Roles of Residues.

Although the GEM-GECO1 crystal structure is unavailable, some essential insights can be drawn from parent GCaMP structures that show the conserved serine residue along the ESPT path largely in the same plane of the chromophore (10, 33). We made all of the relevant GEM-GECO1 mutations (4) to the Ca2+-free GCaMP2 crystal structure 3EKJ (10) and attached the missing part of CaM and M13 units, followed by a 10-ns molecular dynamics simulation to find the lowest-energy structure (SI Text, Fig. S4). To obtain additional insight, we used site-directed mutagenesis to identify potential roles of single residues in modulating the fluorescence response. Specifically, we introduced the individual mutations P60L, E61H, V116T, S118G, and P377R and measured the absorption and emission spectra of the resulting proteins (Figs. S5 and S6). In the crystal structure of Ca2+-bound GCaMP (3EVR) (9) that is considered to closely resemble the Ca2+-bound GEM-GECO1 (Table S3), residues E61 (M13 to FP linker), T116 and S118 (FP domain), and R377 (CaM domain) all participate in an extensive H2O-bridged H-bonding network that includes the phenolate oxygen of the chromophore. All five mutations (Table S4) showed a decrease in the ratio of blue to green fluorescence, ranging from slight to severe, in the Ca2+-bound form (Figs. S5 and S6A). P377R shows the most profound effect on GEM-GECO1 function and essentially eliminates its dual-emission imaging capability (SI Text).

Discussion

The emerging group of FPs capable of Ca2+ sensing paves the way to a myriad of important experiments including imaging neural activities (6) and cancer metastasis (34). However, to realize the full potential of these FPs, we need to unravel the molecular choreography of ESPT that is at the core of the fluorescence change upon Ca2+ binding. Structural differences can be inferred from crystallography, but the dynamics insights are pivotal to understand chemical reactivity. The FSRS results unveil important details of the ES structural evolution of the photoexcited GEM-GECO1 chromophore, and paint a clear portrait of its specific local environment affecting transient atomic motions and determining the fluorescence outcome.

Initial Structural Motion of the Chromophore Gates ESPT.

The spectral oscillations in the first few picoseconds of both Ca2+-free and -bound proteins indicate that characteristic low-frequency modes project strongly onto the initial reaction coordinate out of the FC region. This pre-ESPT timescale sees dominant collective skeletal motions of the chromophore that tend to dissipate photoexcitation energy (31) or push its phenolic proton away (22, 35). In the Ca2+-free protein, the ∼200 fs oscillatory period reveals a dominant ∼170 cm−1 in-plane rock of the phenol ring (Fig. 5). This motion is structurally relevant as it is capable of modulating the phenolic proton position in reference to nearby water molecules and protein residues, leading to frequency and intensity oscillations of the phenolic C–O stretching mode and other high-frequency modes. In the lowest-energy structure for Ca2+-free GEM-GECO1 (Fig. S4), a side-to-side in-plane phenol ring rocking motion is more efficient for proton transport than an out-of-plane ring wag, like the 120 cm−1 mode observed in wtGFP (22). Meanwhile, the partially open β-barrel hosts multiple labile H2O molecules (33, 36), so the lack of a conserved H2O molecule along the 170 cm−1 rocking motion trajectory toward S118 also explains the lengthened ESPT in Ca2+-free GEM-GECO1 (∼30 ps) vs. wtGFP (∼5 ps). The involvement of bridging H2O is essential for ESPT because the distance between the phenolic proton and S118 is larger (∼4.9 Å) than a typical H-bond length. Our molecular dynamics simulations show such bridging H2O molecules in the lowest-energy configuration (Fig. S4B). Ultrafast structural motions of H2O and S118, E135 sidechains are expected in S1 to facilitate ESPT via an optimized H-bonding chain (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Illustration of initial structural evolution gating ESPT in the Ca2+-free GEM-GECO1. Geometric constraints from the Ca2+-free GCaMP2 crystal structure 3EKJ are used. An optimized ESPT pathway is delineated with an intervening H2O molecule added (Fig. S4B) due to limited resolution of the crystal structure. To obtain an SYG chromophore, the methyl group of T223 is replaced by an H atom without further structural modification. The 170 cm−1 mode facilitates ESPT with three positions depicted (DFT-calculated mode displacements are ±2° in equilibrated S0). The bridge C—C single bond shifts from the inherent structure (gray, 125°, the bridge C = C–C angle) back (orange, 132°) and forth (cyan, 118°) to modulate H-bonding geometry in S1 with the adjacent H2O molecule. C, O, N, and H atoms are shown in gray, red, blue, and white, respectively. The surrounding protein environment is shown in green. Rendered using visual molecular dynamics (VMD) (49).

Notably, one conserved low-frequency mode does not dictate ESPT in all systems. The local environment of the embedded chromophore plays a key role in shaping the PES and electronic redistribution, and the coherent low-frequency motions along the ESPT reaction coordinate (22, 37). Therefore, the local geometry and nuclear motion in tandem are responsible for the ESPT efficiency as the chromophore searches phase space to convert from A* to I* before fluorescence. The dominant 120 cm−1 ring wag in wtGFP arises from a conserved H2O molecule and S205 above the chromophore ring plane (22), with nearby ESPT-prone residues H148 and T203 situated out of the plane to stabilize the deprotonated chromophore. Also, the wtGFP crystal structure shows T203 (Table S3) in two distinct positions (38), indicating that its sidechain can rotate to H bond and stabilize the anionic chromophore, and thus facilitate ESPT. In contrast, the T116V mutation and the largely in-plane S118 (Fig. S4) diminish the functional relevance of a phenolic ring wag in the Ca2+-free GEM-GECO1, which instead adopts a 170 cm−1 in-plane rocking motion to drive ESPT (SI Text) but less efficiently. This is in accord with previous reports of longer ESPT time in wtGFP upon T203V mutation (17, 18).

Structural Dynamics in the Chromophore Local Environment for Ca2+ Sensing.

The FSRS data reveal the dependence of chromophore dynamics on allosteric Ca2+ binding to the CaM domain of GEM-GECO1. The presence of competing skeletal modes in the Ca2+-bound protein (Fig. S3) reveals that initial energy dissipation takes on multiple yet less directional pathways. The coherent low-frequency modes originate from vibronic coupling and are likely ubiquitous in photoexcited environments (22, 39–41), similar to the case of photoacid pyranine in various solvents (31, 42–45). Pyranine undergoes ESPT in water following photoexcitation (45), but ESPT is blocked in methanol and multiple low-frequency modes are observed (31). These coherent low-frequency modes are anharmonically coupled to high-frequency modes and are functionally requisite to search local phase space to dissipate energy in lieu of ESPT.

In canonical GCaMPs, the Ca2+-bound protein is brightly fluorescent and the Ca2+-free protein emits dim fluorescence (4–13). Based on crystal structure 3EVR, it was conjectured that chromophore deprotonation occurs when Ca2+ binds to CaM because a conserved R377 coordinates an H2O molecule near the chromophore phenolic end and participates in an extensive H-bonding network. The Ca2+-free protein is dimly fluorescent due to both a protonated chromophore and solvent access to the chromophore pocket that results in fluorescence quenching. In contrast, GEM-GECO1 fluoresces green without Ca2+ but blue with Ca2+, so the GCaMP fluorescence modulation cannot be the dominant mechanism for this sensor, which possesses several key point mutations relative to its GCaMP progenitor. Our reversal mutagenesis results manifest that the interfacial R377P mutation plays an essential role in removing the aforementioned R377 interaction and effectively inhibits ESPT in the Ca2+-bound protein. As position 377 is in a helical segment of CaM, proline mutation will affect the secondary and tertiary protein structure.

In Ca2+-bound GEM-GECO1, it is thermodynamically unlikely for water to be completely excluded from the protein interior because the β-barrel opening is large (10, 46), but the availability of water molecules alone cannot enable ESPT. Previous work explored pH-dependent dual-emission GFP variants (15, 47) with mutations at positions 65, 148, and 203: blue fluorescence was attributed to decreased H-bond interactions and increased hydrophobicity of the protein pocket. As an analogy, although P377 in the Ca2+-bound protein cannot directly participate in the extensive H-bond network due to lack of an ionizable group and restricted sidechain conformation, this mutation likely repositions other CaM residues (e.g., M375 or M379; SI Text) such that they increase the hydrophobicity of chromophore environment, promote the neutral form, reduce the available H bonds, and impede ESPT pathways by increasing the reaction barrier. Generation and analysis of the Ca2+-bound GEM-GECO1 crystal structure should reveal which repositioned residues are involved in these critical interactions at the FP–CaM interface.

In addition, the wtGFP mutant S65T/H148E exhibited dual emission but with strong pH dependence (47), hinting the role played by a repositioned glutamate to the chromophore. Our mutagenesis results show that the Ca2+-bound E61H variant has reduced blue but enhanced green fluorescence, indicative of less ESPT disruption and reduced dual-emission capability (Fig. S6). Therefore, the closing in of some negatively charged residues could destabilize the deprotonated chromophore and contribute to A* trapping in the Ca2+-bound GEM-GECO1.

Conclusion

Using FSRS, we studied the time-resolved excited-state structural dynamics of dual-emission GEM-GECO1 and inferred its fluorescence modulation mechanism. Distinct vibrational dynamics are associated with Ca2+-free and -bound states due to their different chromophore pocket environments. The Ca2+-free protein A* modes decay with a dominant 30–40 ps time constant, and vibrational modes associated with the intermediate deprotonated I* state rise on a similar timescale. Remarkably, most of the A* modes have a well-defined 200-fs spectral oscillation period that corresponds to a 170 cm−1 phenol ring-rocking motion about the bridge carbon. This impulsively excited coherent motion affords directionality of the wavepacket moving out of the FC region toward ESPT barrier crossing, facilitating phenolic proton transfer to a largely in-plane adjacent serine residue via labile bridging water molecules.

Upon Ca2+ binding, the GEM-GECO1 chromophore gets trapped in A* after photoexcitation and emits blue fluorescence. Analysis of spectral oscillations therein reveals multiple competing low-frequency modes, dissipating energy in lieu of ESPT. The key ingredients for Ca2+-induced ESPT inhibition are identified to include (i) structural rearrangement as CaM compresses and forms a new interface with GFP, increasing the hydrophobicity around the chromophore; (ii) disruption of the pro-ESPT H-bonding network; and (iii) negative residues moving closer to the phenolic end to hinder chromophore deprotonation. The elucidation of elementary steps in ES structural evolution of a 3-residue chromophore inside a 450+ residue protein complex offers crucial insights into the dual-emission Ca2+-sensing GEM-GECO1, which not only paves the way to mechanistically study photosensitive biomolecules in physiological conditions, but also enables targeted protein design to develop more powerful biosensors.

We anticipate that the allosteric mechanism of transient conformational dynamics induced by Ca2+ can be further studied with a photolabile molecular cage that releases Ca2+ with femtosecond time resolution (48). The nonequilibrium structural evolution of the chromophore may be tracked using a common 400-nm photoexcitation pulse.

Materials and Methods

A full description of methods is given in SI Materials and Methods. To prepare GEM-GECO1 proteins for in vitro spectroscopic characterization, Escherichia coli cells expressing 6-histidine tagged GEM-GECO1 were grown in 1 L of a modified terrific broth at 30 °C for two days, collected by centrifugation and lysed by French press. Proteins from the clarified supernatant were then purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity chromatography and finally exchanged to 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (OD > 1/mm at 400 nm) with either 10 mM EGTA (Ca2+-free sample) or 10 mM CaEGTA (Ca2+-bound sample). Time-resolved excited-state spectra of photoexcited GEM-GECO1 proteins with and without Ca2+ were collected by an FSRS setup that was previously described (44, 45), using similar photoexcitation power on a 1-mm-thick protein sample solution (OD ∼ 1/mm at 400 nm) in a flow cell to avoid thermal effects or photodegradation (22).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support is provided by the Oregon State University Faculty Startup Research Grant and General Research Fund Award (to C.F.), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada & Canadian Institutes of Health Research (R.E.C.), and a University of Alberta fellowship and an Alberta Innovates scholarship (to Y.Z.). R.E.C. holds a Tier II Canada Research Chair.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1403712111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shimomura O, Johnson FH, Saiga Y. Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1962;59:223–239. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030590302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263(5148):802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67(1):509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, et al. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca²⁺ indicators. Science. 2011;333(6051):1888–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1208592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada Y, Mikoshiba K. Quantitative comparison of novel GCaMP-type genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators in mammalian neurons. Front Cell Neurosci. 2012;6:41. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2012.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akerboom J, et al. Genetically encoded calcium indicators for multi-color neural activity imaging and combination with optogenetics. Front Mol Neurosci. 2013;6:2. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2013.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker AS, Burrone J, Meyer MP. Functional imaging in the zebrafish retinotectal system using RGECO. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:34. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyawaki A, et al. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature. 1997;388(6645):882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Q, Shui B, Kotlikoff MI, Sondermann H. Structural basis for calcium sensing by GCaMP2. Structure. 2008;16(12):1817–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akerboom J, et al. Crystal structures of the GCaMP calcium sensor reveal the mechanism of fluorescence signal change and aid rational design. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(10):6455–6464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohkura M, et al. Genetically encoded green fluorescent Ca2+ indicators with improved detectability for neuronal Ca2+ signals. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen T-W, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499(7458):295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wachowiak M, et al. Optical dissection of odor information processing in vivo using GCaMPs expressed in specified cell types of the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2013;33(12):5285–5300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4824-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson GT, et al. Green fluorescent protein variants as ratiometric dual emission pH sensors. 1. Structural characterization and preliminary application. Biochemistry. 2002;41(52):15477–15488. doi: 10.1021/bi026609p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McAnaney TB, Park ES, Hanson GT, Remington SJ, Boxer SG. Green fluorescent protein variants as ratiometric dual emission pH sensors. 2. Excited-state dynamics. Biochemistry. 2002;41(52):15489–15494. doi: 10.1021/bi026610o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Thor JJ, et al. Ultrafast vibrational dynamics of parallel excited state proton transfer reactions in the green fluorescent protein. Vib Spectrosc. 2012;62(0):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kummer AD, et al. Effects of threonine 203 replacements on excited-state dynamics and fluorescence properties of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) J Phys Chem B. 2000;104(19):4791–4798. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung G, Wiehler J, Zumbusch A. The photophysics of green fluorescent protein: Influence of the key amino acids at positions 65, 203, and 222. Biophys J. 2005;88(3):1932–1947. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.044412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shu X, et al. An alternative excited-state proton transfer pathway in green fluorescent protein variant S205V. Protein Sci. 2007;16(12):2703–2710. doi: 10.1110/ps.073112007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Thor JJ, Zanetti G, Ronayne KL, Towrie M. Structural events in the photocycle of green fluorescent protein. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109(33):16099–16108. doi: 10.1021/jp051315+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonge PJ, Meech SR. Excited state dynamics in the green fluorescent protein. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2009;205(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang C, Frontiera RR, Tran R, Mathies RA. Mapping GFP structure evolution during proton transfer with femtosecond Raman spectroscopy. Nature. 2009;462(7270):200–204. doi: 10.1038/nature08527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin ME, Negri F, Olivucci M. Origin, nature, and fate of the fluorescent state of the green fluorescent protein chromophore at the CASPT2//CASSCF resolution. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(17):5452–5464. doi: 10.1021/ja037278m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Sun Q, Li Z, Nanbu S, Smith SS. First principle study of proton transfer in the green fluorescent protein (GFP): Ab initio PES in a cluster model. Comput Theor Chem. 2012;990(0):185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grigorenko BL, Nemukhin AV, Polyakov IV, Morozov DI, Krylov AI. First-principles characterization of the energy landscape and optical spectra of green fluorescent protein along the A→I→B proton transfer route. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(31):11541–11549. doi: 10.1021/ja402472y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chattoraj M, King BA, Bublitz GU, Boxer SG. Ultra-fast excited state dynamics in green fluorescent protein: Multiple states and proton transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(16):8362–8367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lossau H, et al. Time-resolved spectroscopy of wild-type and mutant Green Fluorescent Proteins reveals excited state deprotonation consistent with fluorophore-protein interactions. Chem Phys. 1996;213(1–3):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ai HW, Shaner NC, Cheng Z, Tsien RY, Campbell RE. Exploration of new chromophore structures leads to the identification of improved blue fluorescent proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46(20):5904–5910. doi: 10.1021/bi700199g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell AF, He X, Wachter RM, Tonge PJ. Probing the ground state structure of the green fluorescent protein chromophore using Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2000;39(15):4423–4431. doi: 10.1021/bi992675o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 09, Revision B.1. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, et al. Early time excited-state structural evolution of pyranine in methanol revealed by femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy. J Phys Chem A. 2013;117(29):6024–6042. doi: 10.1021/jp312351r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lochbrunner S, Wurzer AJ, Riedle E. Ultrafast excited-state proton transfer and subsequent coherent skeletal motion of 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole. J Chem Phys. 2000;112(24):10699–10702. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, et al. Structural insight into enhanced calcium indicator GCaMP3 and GCaMPJ to promote further improvement. Protein Cell. 2013;4(4):299–309. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-2103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Calcium in tumour metastasis: New roles for known actors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(8):609–618. doi: 10.1038/nrc3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hynes JT, Tran-Thi T-H, Granucci G. Intermolecular photochemical proton transfer in solution: New insights and perspectives. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2002;154:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leder L, et al. The structure of Ca2+ sensor Case16 reveals the mechanism of reaction to low Ca2+ concentrations. Sensors (Basel) 2010;10(9):8143–8160. doi: 10.3390/s100908143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erez Y, et al. Structure and excited-state proton transfer in the GFP S205A mutant. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115(41):11776–11785. doi: 10.1021/jp2052689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brejc K, et al. Structural basis for dual excitation and photoisomerization of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(6):2306–2311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vos MH, Rappaport F, Lambry J-C, Breton J, Martin J-L. Visualization of coherent nuclear motion in a membrane protein by femtosecond spectroscopy. Nature. 1993;363(6427):320–325. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Q, Schoenlein RW, Peteanu LA, Mathies RA, Shank CV. Vibrationally coherent photochemistry in the femtosecond primary event of vision. Science. 1994;266(5184):422–424. doi: 10.1126/science.7939680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu L, Sage JT, Champion PM. Observation of coherent reaction dynamics in heme proteins. Science. 1994;266(5185):629–632. doi: 10.1126/science.7939716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rini M, Magnes B-Z, Pines E, Nibbering ETJ. Real-time observation of bimodal proton transfer in acid-base pairs in water. Science. 2003;301(5631):349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.1085762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cox MJ, Timmer RLA, Bakker HJ, Park S, Agmon N. Distance-dependent proton transfer along water wires connecting acid-base pairs. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113(24):6599–6606. doi: 10.1021/jp9004778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu W, Han F, Smith C, Fang C. Ultrafast conformational dynamics of pyranine during excited state proton transfer in aqueous solution revealed by femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116(35):10535–10550. doi: 10.1021/jp3020707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han F, Liu W, Fang C. Excited-state proton transfer of photoexcited pyranine in water observed by femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy. Chem Phys. 2013;422(0):204–219. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helms V. Protein dynamics tightly connected to the dynamics of surrounding and internal water molecules. ChemPhysChem. 2007;8(1):23–33. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200600298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shu X, et al. Ultrafast excited-state dynamics in the green fluorescent protein variant S65T/H148D. 1. Mutagenesis and structural studies. Biochemistry. 2007;46(43):12005–12013. doi: 10.1021/bi7009037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ley C, et al. Femtosecond to subnanosecond multistep calcium photoejection from a crown ether-linked merocyanine. ChemPhysChem. 2009;10(1):276–281. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.