Abstract

We have synthesized a photosensitive (or caged) 4-carboxymethoxy-5,7-dinitroindolinyl (CDNI) derivative of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Two-photon excitation of CDNI-GABA produced rapid activation of GABAergic currents in neurons in brain slices with an axial resolution of approximately 2 micrometers, and enabled high-resolution functional mapping of GABA-A receptors. Two-photon uncaging of GABA, the major inhibitory neurotransmitter, should allow detailed studies of receptor function and synaptic integration with subcellular precision.

Two-photon (2P) excitation is a method that has revolutionized many areas of biological science as it enables three-dimensionally defined excitation of chromophores in biological tissue1,2. We previously developed 4-methoxy-7-nitroindolinyl-L-glutamate (MNI-Glu3 1) and 4-carboxymethoxy-5,7-dinitroindolinyl-L-glutamate (CDNI-Glu4 2) for 2P uncaging in mammalian brain slices. Depending on the size of the 2P excitation volume, we mimicked synaptic quantal release of glutamate using diffraction limited 2P uncaging3 or fired action potentials and mapped unitary synaptic connections in a large volume of the neocortex using macro 2P uncaging5. Although a variety of caged glutamate probes have been reported6, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), has received comparatively little attention from chemical biologists, and 2P uncaging of this vital neurotransmitter has not been reported. We have synthesized a new caged GABA derivative (CDNI-GABA, 3) that undergoes 2P photolysis in living brain slices with low power (ca. 10 mW at 720 nm) and at low concentrations (0.40-1.35 mM). Two-photon uncaging of CDNI-GABA over the axon initial segment (AIS) of CA1 pyramidal neurons enabled high resolution functional mapping that showed a punctate distribution of GABA-A receptors. Successive functional mapping of the apical dendrite with CDNI-GABA and MNI-Glu revealed no correlation between the distribution of GABA and glutamate receptors. CDNI-GABA uncages rapidly and efficiently (quantum yield of 0.60), therefore this new caged GABA probe is a useful addition to the optical toolbox available to neuroscientists.

The synthesis of CDNI-GABA (Fig. 1a) is outlined in Supplementary Fig 1. The quantum yield for uncaging of CDNI-GABA was determined by comparison with a known photochemical standard. HPLC analysis of the time-course of photolysis showed that CDNI-GABA was photolyzed about seven times faster than MNI-Glu, implying that the quantum yield of photolysis was 0.60 (± 0.02, n=3). The presence of a strongly electron withdrawing group at the 5-position promotes deprotonation of the C-2 hydrogen, enhancing the quantum yield of bond scission to give the desired uncaged amino acid.

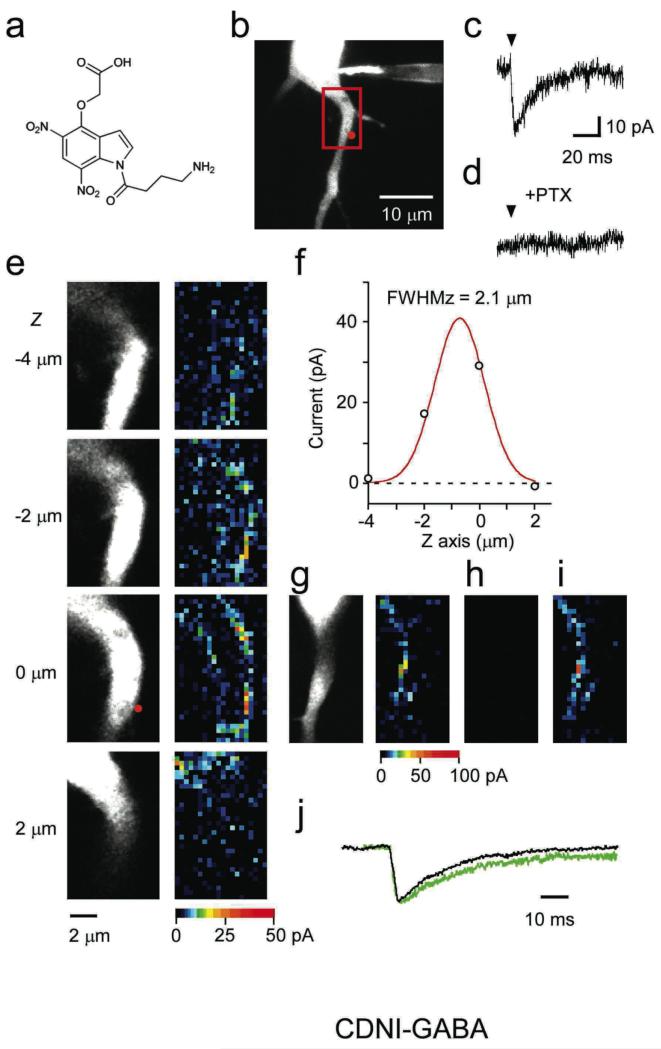

Figure 1. Functional mapping of GABA sensitivities in the perisomatic dendritic area of a hippocampal neuron by 2P photolysis of CDNI-GABA.

(a) Structure of CDNI-GABA. (b) A fluorescent image of a CA1 pyramidal neuron filled with Alexa-594 dye. The red-boxed region was mapped in (e). (c) Irraidation (6.3 mW, 1 ms, arrow) of CDNI-GABA (1.35 mM, puffed from a pipette close to the surface of the brain slice ) evoked a rapid current trace (2pIPSC) recorded from the pixel indicated by the red dot in (b). (d) Current trace from the same pixel in the presence of PTX. (e) The perisomatic area (red box in b) was subjected to 2P functional mapping in four planes (left), the evoked currents (right) from each pixel (grid of 16×32) is shown on a pseudo-color scale (bottom). (f) Amplitudes of 2pIPSCs (circles) at the pixels corresponding to the red point shown in (e) at each Z-axis. The smooth red line represents Gaussian fitting of the data. (g) Mapping of functional GABA-A responses (right) across a dendritic surface (left) using femtosecond pulses from a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser. (h) Mapping the same region with the same laser in continuous-wave mode (non-mode locked) with the same power. (i) Restoration of mode-lock reproduced the functional map shown in (g). (j) Comparison of the average of 66 2pIPSCs with peak amplitudes of > 10 pA (selected from the mapping shown in (e) at Z-axis of 0 μm) with the average of 24 spontaneous mIPSCs whose peak amplitudes were > 10 pA recorded from the same neuron. The peak amplitudes were normalized.

Photolysis of CDNI-GABA near the edge of the perisomatic apical dendrite of CA1 pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1b) with 6.3 mW for 1 ms evoked fast inhibitory postsynaptic potential currents (which we call “2pIPSCs”, see Fig. 1c) that were blocked by picrotoxin (PTX 4, Fig. 1d). Because power requirements for 2P uncaging of CDNI-GABA were low, we reasoned that this new caged GABA could enable three-dimensional mapping of receptor densities3, without fear of photodamage. Functional mapping at four z-sections (Fig. 1e) revealed that the axial resolution of the evoked current was close to the diffraction limit (Fig. 1f; full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) = 2.1 μm, microscope resolution 1.4 μm at 720 nm). These data show that non-linear excitation particularly helps limit axial uncaging in comparison to UV-visible (i.e. 1P) excitation. Similar benefits have been reported for 2P uncaging of glutamate in brain slices7-10.

We established that the evoked currents arose from 2P excitation1 by mapping the GABA-A receptor density across the surface of the apical dendrite with and without laser mode-lock (Fig. 1g-i). No current was evoked with a mode-unlocked laser (Fig. 1h), whereas similar functional receptor maps were detected before and after this experiment with a mode-locked laser (Fig. 1g,i).

Two-photon uncaging of CDNI-GABA allowed us to approximate miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs), as the rise time and decay kinetics of 2pIPSCs were similar to those of spontaneous mIPSCs (Fig. 1j, and Supplementary Table). Specifically, the average rise time (20-80%) of the 2pIPSCs was 2.0 ± 0.2 ms (6-112 events per cell, n = 6 cells), whereas the average rise time of the spontaneous mIPSCs was 1.5 ± 0.2 ms (10-66 events per cell, n = 6 cells). The average rise times of the 2pIPSCs and mIPSCs were not significantly different (P = 0.075, paired t test). The decay half-times were 24.7 ± 2.5 ms (2pIPSCs) and 10.5 ± 1.1 ms (mIPSCs), which were significantly different (P < 0.005, paired t test, n = 6 cells). Since 2P uncaging of CDNI-GABA on the perisomatic dendritic membrane showed a dense distribution of GABA-A receptors (Fig. 1e), the longer decay time of the 2pIPSC probably reflects the increased clearance time of uncaged GABA from clusters of GABA-A receptors near the focal volume of 2P excitation.

Funtional mapping with CDNI-GABA was reproducible (Fig. 1g,i correlation coefficient (CC) of 0.65 ± 0.02, n = 4 pairs of maps in 4 cells), implying that hot spots of GABA responses do not rapidly diffuse laterally. If such hot spots were GABAergic synapses, they should be devoid of glutamate receptors, because GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses are structurally different11. Comparison of functional maps of GABA-A and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)-type glutamate receptors on the same proximal dendrites (Fig. 2a,b) showed CC of 0.22. These data suggest that the hot spots of functional GABA-A receptors were anchored clusters of GABA-A receptors, probably GABAergic postsynaptic sites, and that the number of functional GABA-A receptors varied among synapses.

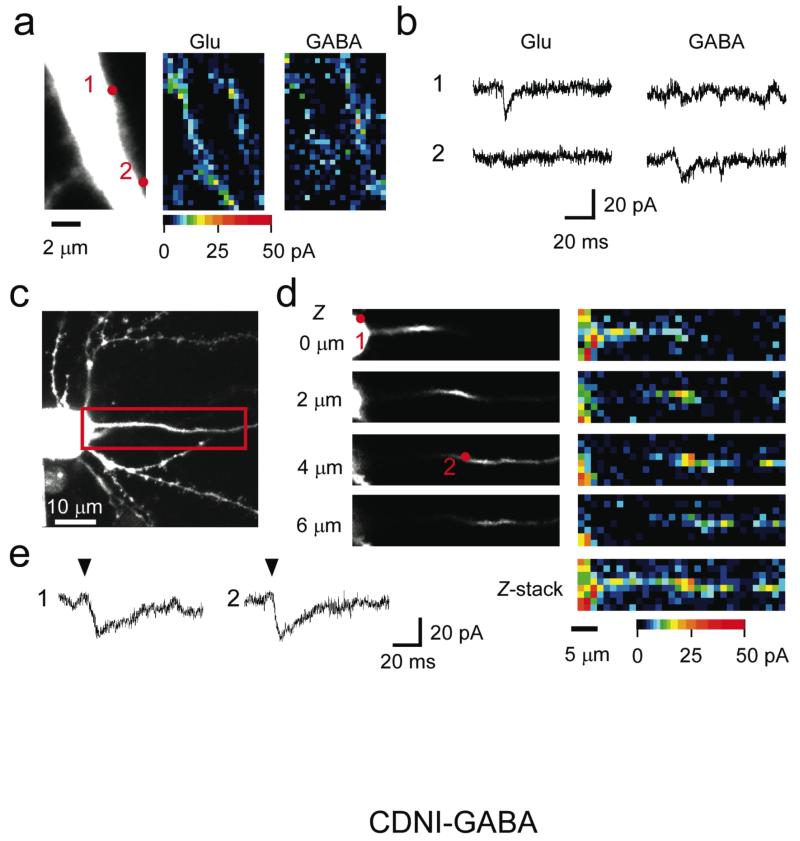

Figure 2. Functional mapping of GABA-A receptors on the proximal apical dendrites and the axon initial segment.

(a) Left: Z-stacked fluorescent image of a CA1 pyramidal neuron filled with Alexa-594 dye. First, 10 mM MNI-Glu was puffed from the glass pipette onto the slice surface and functional mapping of glutamate responses was performed (middle), then 1.35 mM CDNI-GABA was locally applied for functional mapping of GABA-R (right). The laser intensity in (a) was 3.9 mW and 6.3 mW for 2P uncaging of MNI-Glu and CDNI-GABA, respectively. The illumination time was 1 ms per pixel. (b) The induced currents at the numbered red dots in (a). (c) A Z-stacked fluorescent image of a CA1 pyramidal neuron filled with Alexa-594 dye. The red-boxed region was mapped by 2P uncaging (9.8 mW, 2ms per pixel) of 1.35 mM CDNI-GABA. The neuronal structure within the red box did not have any spine structure and projected to distal sites beyond the red box. Thus this structure represents the AIS. (d) Three dimensional mapping of functional GABA receptors on the AIS. Left panels show the structure of the AIS at four focal planes, while right panels show the GABA responses at the four planes. Right bottom panel shows the Z-stacked map by max-intensity projection. GABA responses at the numbered red dots (1: soma; 2: AIS) are shown in (e). Arrows indicate the time of illumination and the pseudo-color scales indicate the amplitude of corresponding responses..

One of the major functions of GABA-A receptors is to modulate the generation of action potential in the AIS where sodium channels are densely distributed12. Although immunological staining has revealed that axo-axonic cells innervate the AIS via GABAergic synapses with GABA receptors13,14, the functional distribution of GABA-A receptors along the AIS has not been clarified. Thus, we performed three dimensional mapping of GABA-A receptors on the AIS. We detected heterogeneous responses of functional GABA-A receptors along the AIS over 40 μm (Fig. 2c,d). The kinetics of the currents (Fig. 2e) was similar to that obtained at the somatic membrane. The detection of functional GABA-A receptors on the AIS needed a higher energy of 2P excitation than that used at the perisomatic apical dendrite. Immunoelectron microscopy has shown that synaptic size and the number of synaptic GABA-A receptors in the AIS are smaller than those in the soma14. Our data confirm this, showing a functionally disparate distribution of inhibitory receptors at the major input and output pathways of pyramidal neurons.

The most widely used15 caged GABA (α-carboxy-o-nitrobenyl[CNB]-GABA16 5) has been reported to be a mild antagonist of GABA-A receptors17. Consequently we tested the basic pharmacology of CDNI-GABA, the structurally related CNI-GABA 6 and the widely used MNI-Glu. Concentrations of 0.325 mM CNI-GABA when bath-applied in the artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) perfusate have no effect on the tonic firing of neurons of the deep cerebellar nuclei in brain slices18. We found that a much higher concentration of CNI-GABA (10 mM), which we used for 2P uncaging (data not shown), or CDNI-GABA (10 mM) inhibited GABA-A receptors currents in acute hippocampal slices when co-applied with GABA itself (Supplementary Fig. 2a and 2b). Much to our surprise the same concentration of MNI-Glu (as used in Fig. 2) had similar effects (Supplementary Fig. 2b). These findings implied that high concentrations of structurally diverse caged transmitters such as MNI-Glu, CNI-GABA, and CDNI-GABA block GABA-A receptors. In particular, the block of GABA-A receptors by MNI-Glu indicates a potential risk for caged neurotransmitters to affect receptors other than their intended target. The lower concentration of CDNI-GABA (1.35 mM) used for Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 still reduced GABA-A receptors current when co-applied with 0.1 mM GABA by 70 % (Supplementary Fig. 2a and 2b). Spontaneous mIPSCs were surpressed during puff application of 1.35 mM CDNI-GABA (Supplementary Fig. 2c.) However, 0.4 mM CDNI-GABA reduced currents by only 22 % (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Further, the antagonism on the size and frequency of spontaneous mIPSCs at 0.4 mM was mild, as almost immediately after the end of the puff the standard-sized signals of spontaneous mIPSCs reappeared (Supplementary Fig. 2d). We tested 2P uncaging at this concentration and found it was feasible (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus CDNI-GABA can be used for 2P functional mapping under conditions of very mild antagonism towards GABA-A receptors.

A variety of caged GABA compounds have been reported over the past 14 years16,18-21. However, only CNB-GABA16 has been used by many laboratories15, and so the properties of this important compound are compared with CDNI-GABA, along with recent alternative approaches18-20, in Table 1. CDNI-GABA is not only uniquely effective for 2P functional mapping (Figs. 1,2), it is significantly more photochemically efficient for UV-visible photolysis (i.e. ε.φ ) than the other caged GABAs (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the chemical and pharmacological properties of the caged GABA probes that have been extensively tested on living neurons.

| Caged GABA |

ε | φ | ε.φ | rate | 2PP | Pharmacology | Stability | Solubility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNB16 | 430a | 0.14 | 60 | 21 μs | no | Partial antagonist | Half-life 17 h RT. |

>50 mM |

| BC20419 | 14000b | 0.04 | 560 | 4 ms | ND | No antagonism < 30 μM |

Stable | ND |

| RuBi20 | 6400c | 0.2 | 1280 | ND | ND | No antagonism < 20 μM |

Stable | ND |

| CNI18 | 4200d | 0.1 | 420 | ND | Yes | strong antagonist at 10 μM |

Stable at− 20°C |

200 μM |

| CDNI | 6400d | 0.6 | 3840 | ND | Yes | Mild antagonist at 0.4 μM |

Stable pH 2, pH 7.4 6% hydrolysis 17h −20°C |

100 μM |

Abbreviations and symbols: ε, extinction coefficient (M-1 cm-1), φ, quantum yield, ND, no data, 2PP, two-photon photolysis.

at 350 nm,

at 377 nm,

at 424 nm,

at 330 nm.

The inherent non-linear nature of 2P microscopy means that axial excitation is greatly restricted when compared with UV-visible excitation1,2. This property has enabled several laboratories to achieve stimulation of AMPA receptors on isolated spine heads3,4,7-10,22-25 using 2P uncaging of glutamate. In this report we introduce a new caged compound, CDNI-GABA, that releases GABA with high quantum efficiency (0.6) and that undergoes effective 2P photolysis. Two-photon uncaging of CDNI-GABA on neurons in brain slices evoked rapid postsynaptic currents with an axial resolution of about 2 μm. This accuracy allowed high-resolution functional mapping of GABA-A receptors along the axon initial segment and the perisomatic dendritic region of CA1 pyramidal cells for the first time. Two-photon photolysis of CDNI-GABA should be a powerul tool to clarify, for example, GABAergic inhibitory effects on the ion flux through excitatory synapses, the propagation of depolarization along dendrites, and the generation of action potentials at the micrometer and even single synaptic level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH (USA) grant GM53395 (to GCRE-D), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas-Elucidation of neural network function in the brain No. 20021008 (to MM), a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) No. 19680020 (to MM) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Japan, and PRESTO, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Japan (to MM).

Footnotes

Author contributions.

GCRE-D made and characterized the caged compounds. MM and TH performed biological experiments and analyzed the data. HK provided resources and support for the biological experiments. GCRE-D and MM wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Denk W, Svoboda K. Neuron. 1997;18:351–7. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svoboda K, Yasuda R. Neuron. 2006;50:823–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuzaki M, et al. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:1086–92. doi: 10.1038/nn736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis-Davies GCR, Matsuzaki M, Paukert M, Kasai H, Bergles DE. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:6601–4. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1519-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GCR, Kasai H. J. Neurophysiol. 2008;99:1535–44. doi: 10.1152/jn.01127.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis-Davies GCR. New Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. 2008:e876. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beique JC, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 2006;103:19535–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608492103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankar GM, et al. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asrican B, Lisman J, Otmakhov N. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14007–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3587-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MA, Ellis-Davies GCR, Magee JC. J. Physiol. 2003;548:245–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Megias M, Emri Z, Freund TF, Gulyas AI. Neuroscience. 2001;102:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. Cereb. Cortex. 1997;7:476–86. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Benke D, Fritschy JM, Somogyi P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 1996;93:11939–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyiri G, Freund TF, Somogyi P. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:428–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eder M, Zieglgansberger W, Dodt HU. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;15:167–183. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2004.15.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gee KR, Wieboldt R, Hess GP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:8366–8367. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molnar P, Nadler JV. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;391:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvina K, Walter JT, Kohn A, Ellis-Davies G, Khodakhah K. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:1256–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curten B, Kullmann PHM, Bier ME, Kandler K, Schmidt BF. Photochem. Photobiol. 2005;81:641–648. doi: 10.1562/2004-07-08-RA-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zayat L, et al. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:2035–8. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papageorgiou G, Corrie JET. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:9668–9676. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter AG, Sabatini BL. Neuron. 2004;44:483–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araya R, Eisenthal KB, Yuste R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 2006;103:18799–804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609225103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobczyk A, Scheuss V, Svoboda K. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6037–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1221-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remy S, Csicsvari J, Beck H. Neuron. 2009;61:906–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.