Abstract

Psychological research using mostly cross-sectional methods calls into question the presumed function of shame as inhibitor of immoral or illegal behavior. In a longitudinal study of 476 jail inmates, we assessed shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and externalization of blame shortly upon incarceration. Participants (n = 332) were interviewed one year following release into the community and official arrest records were accessed (n = 446). Guilt-proneness negatively, and directly, predicted re-offense in the first year post-release; shame-proneness did not. Further mediational modeling showed that shame-proneness positively predicted recidivism via its robust link to externalization of blame. There remained a direct effect of shame on recidivism, however, such that shame – unimpeded by defensive externalization of blame – inhibited recidivism. Items assessing a motivation to hide were primarily responsible for this pattern. Overall, results suggest that the pain of shame may have two faces – one with destructive and the other with constructive potential.

Keywords: Antisocial Behavior, Emotions

Psychological theory and research underscore the distinction between shame and guilt, and call into question the presumed function of shame as inhibitor of immoral or illegal behavior. Most research on the psychological and behavioral implications of shame, however, has been conducted on non-clinical, low-risk samples – particularly college students – using cross-sectional methods (see Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007, for a review).

What’s the Difference Between Shame and Guilt?

Shame and guilt are both “self-conscious” emotions that arise from self-relevant failures and transgressions, but they differ in their object of evaluation. Feelings of shame involve a painful focus on the self – the sense that “I am a bad person” – whereas feelings of guilt involve a focus on a specific behavior – the sense that “I did a bad thing.”

When people feel guilt about a specific behavior, they experience tension, remorse and regret over the “bad thing done.” Research has shown that this sense of tension and regret typically motivates reparative action – confessing, apologizing, or somehow repairing the damage done (de Hooge, Zeelenberg, & Breugelmans, 2007; Ketelaar & Au, 2003; Lewis, 1971; Sheikh & Janoff-Bulman, 2010; Tangney et al., 1996; Wicker, Payne, & Morgan, 1983).

In contrast, when people feel shame about the self, they feel diminished, worthless, and exposed. Rather than motivating reparative action, the acutely painful shame experience often motivates a defensive response. When shamed, people want to escape, hide, deny responsibility, and blame others. In fact, proneness to shame about the self has been repeatedly associated with a tendency to blame others for one’s failures and shortcomings (Bear, Uribe-Zarain, Manning, & Shiomi, 2009; Luyten, Fontaine, & Corveleyn, 2002; Tangney, 1990; Tangney, Wagner, Fletcher, & Gramzow, 1992), and this tendency to externalize blame has been shown to mediate the link between shame and aggression (Stuewig, Tangney, Heigel, Harty, & McCloskey, 2010).

Does the Propensity to Experience Shame or Guilt Inhibit Criminal Re-Offense?

To what degree does the propensity to experience shame or guilt inhibit subsequent re-offense? Most research on these “moral emotions” comes from social and personality psychology, focusing on low-risk samples of individuals who engage in low rates of dangerous and/or immoral behavior. Furthermore, most studies are cross-sectional in nature, linking current proneness to shame and guilt to retrospective reports of past misdeeds and failures.

This study presents longitudinal data from a large sample of jail inmates held on felony charges. We anticipated that guilt-proneness, assessed shortly upon incarceration, would negatively predict (inhibit) criminal re-offense in the first year post-release. Theoretically, guilt should be more effective than shame in fostering constructive changes in future behavior because what is at issue is not a bad, defective self, but a bad, defective behavior. And it is generally easier to change an objectionable behavior than to change an objectionable self. In contrast, we anticipated that shame-proneness would positively predict re-offense, specifically through its robust link to externalization of blame.

Method

Participants

Participants were 476 pre- and post-trial inmates held on felony charges in a county jail, in a suburb of Washington DC, enrolled shortly after incarceration. Upon enrollment, they were on average 33 years old (SD = 10.2, range 18 to 70), male (67%), completed 12 years of education (SD = 2.2, range 0 to 19), and were ethnically and racially diverse: 45% African American, 35% Caucasian, 9% Latino, 3% Asian, 4% “Mixed,” and 4% “Other.” Participants were recruited for baseline assessment between 2002 and 2007; post-release data are still being collected. Approximately one year following release, participants completed a follow-up interview. Participants received honoraria of $15–18 at baseline (Time 1) and $50 at the one-year follow-up (Time 2). All procedures were approved by the George Mason University Institutional Review Board.

Of the 628 inmates who consented and were enrolled in the study (74% of those who were approached), 482 completed full, valid baseline assessments (i.e. were not transferred or released to bond before assessments could be completed) and were eligible for one year follow-up at the time of these analyses. Six individuals were subsequently dropped from all analyses because they report being incarcerated elsewhere for the year post-release, leaving a sample of 476 individuals. We re-interviewed 332 participants (70%) and have official reports of recidivism on 446 individuals (94%). This retention rate compares very favorably with other longitudinal inmate studies (Brown, St. Amand, & Zamble, 2009; Inciardi, Martin, & Butzin, 2004). Attrition analyses on data collected as of 9/27/12 evaluated baseline differences on 34 variables comparing eligible individuals who were re-interviewed vs. those who were not (not found, refused, and withdrew). Variables including demographics (e.g. sex, education), mental health (e.g. schizophrenia, borderline), psychological (e.g. shame, self-control), criminality (e.g. criminal history, psychopathy), and substance dependence (e.g. alcohol, opiates) showed few differences. Those individuals who were missed tended to be somewhat younger and Hispanic.

Measures and Procedures: Time 1 – Initial Incarceration

Several days into incarceration, eligible inmates were presented with a description of the study and assured of the voluntary and confidential nature of the project. In particular, it was emphasized that the decision to participate would have no bearing on their status at the jail, nor release date. Interviews were conducted in the privacy of professional visiting rooms, used by attorneys, or secure classrooms; data are protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality from DHHS. Participants completed questionnaires using “touch-screen” computers. In addition to presenting items visually, the computer read each item aloud to participants via headphones, accommodating participants with limited reading proficiency. For participants requiring Spanish versions of the measures, questionnaire responses were gathered via individual interview. Both interviewers and participants had paper copies of the translated measures.

Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and externalization of blame were assessed with the Test of Self Conscious Affect –Socially Deviant Version (TOSCA-SD; Hanson & Tangney, 1996), developed for use with incarcerated respondents, as well as other “socially deviant” groups. Like the family of TOSCA measures developed for children, adolescents, and adults living in the community, the TOSCA-SD utilizes a scenario-based approach where respondents are asked to imagine themselves in a series of situations they’ve likely encountered in day-to-day life (e.g., “You are driving down the road and hit a small animal.”). Each scenario is followed by responses that describe shame, guilt, and externalization of blame experiences with respect to the specific context (e.g., for shame, “You would think ‘I’m terrible’;” for guilt, “You would probably think it over several times wondering if you could have avoided it;” and for externalization of blame, “You would think the animal shouldn’t have been on the road”). For more information on reliability and validity in this sample see Tangney, Stuewig, Mashek, & Hastings, 2011.

Measures and Procedures: Time 2 – One Year Post-Incarceration

Approximately one year following release, participants completed an interview over the phone (or face-to-face with participants who had been re-incarcerated or who opted for an in-person interview).

Recidivism during the first year post-release was assessed in multiple ways. First, participants self-reported whether they had been arrested for any of 17 types of crime (e.g. theft, assault, drug offenses, etc.) during the year after their release. Second, participants self-reported whether they had committed but not been caught for the same 17 types of crime. The 17 types of crime were re-categorized using the five types of crime defined by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (violent, property, drug, public order, and other). Two self-report variables were created to assess criminal versatility. (Versatility – i.e. the number of different types of crimes – was employed rather than frequency of arrest/offense, which is confounded with type of crime). The self-report arrest versatility variable measured the number of the five different types of crimes participants were arrested for and the self-report offense versatility variable measured the number of the five different types of crimes participants committed, but were not arrested for. Third, we coded arrests from the FBI National Crime Information Center (NCIC) reports using the same 5 categories. The official record arrest versatility variable measured the number of different types of crimes participants were arrested for, according to NCIC records. The actual range for each of the arrest versatility variables was 0 to 4 and the actual range for the offense diversity variable was 0 to 5 types of crimes. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics and correlations among variables used in analyses.

Table 1.

Scale Intercorrelations and Descriptive Statistics.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Guilt | __ | |||||

| 2. Shame | −.13** | __ | ||||

| 3. Ext | −.40*** | .47*** | __ | |||

| 4. Arrests (OR) | −.08 | −.08 | .07 | __ | ||

| 5. Arrests (SR) | −.15* | .02 | .16** | .67*** | __ | |

| 6. Offense (SR) | −.14* | .03 | .11* | .37*** | .44*** | __ |

| M | 4.31 | 2.09 | 1.99 | .69 | .66 | 1.00 |

| SD | .53 | .57 | .68 | .98 | .89 | 1.18 |

| α | .79 | .71 | .82 | __ | __ | __ |

| n | 476 | 476 | 476 | 446 | 318 | 316 |

Note: Shame = total shame score, Ext = externalization of blame, OR = Official records, SR = self-report.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Analytic Strategy

We used Mplus Version 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 2004) using full information maximum likelihood procedures to take advantage of the entire sample. We first tested whether shame-proneness and guilt-proneness differentially predicted recidivism during the first year post-release. We then conducted more focused follow-up analyses of shame-proneness using a mediational model, with externalization of blame mediating the link between shame-proneness and recidivism.

Results

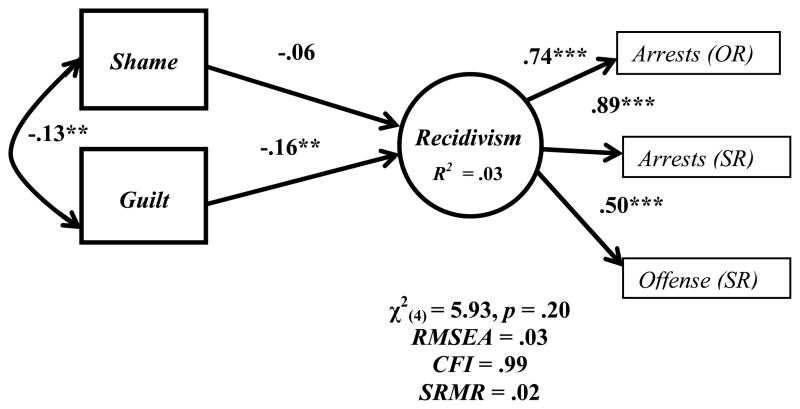

A latent variable representing criminal recidivism during the first year post-release was defined by three indicators of criminal versatility based on (1) official records of arrests, (2) self-reported arrests, and (3) self-reported undetected offenses. As anticipated, guilt-proneness assessed upon incarceration negatively predicted criminal recidivism in the first year post-release. In contrast, shame-proneness did not predict post-release criminal behavior (see Figure 1).1

Figure 1.

Shame- and guilt-proneness assessed upon incarceration predicting recidivism at one-year post-release.

Note: Standardized parameter estimates are displayed. Shame = total shame score, OR = Official records, SR = self-report. ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

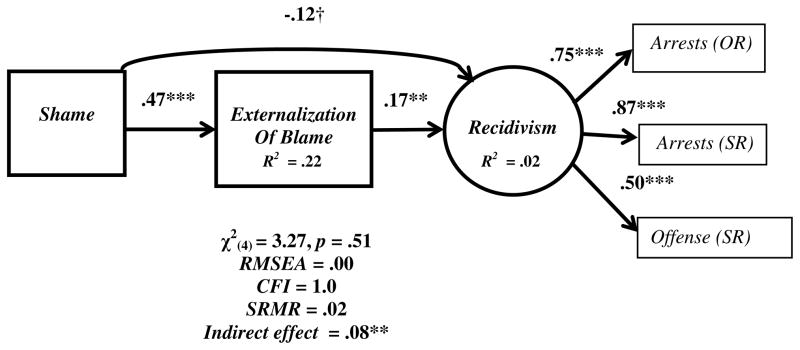

Theoretically, shame-proneness should be positively linked to recidivism via its well-demonstrated robust link to externalization of blame. Shame often prompts defensive efforts to project blame outward, presumably hindering one’s ability to accept responsibility, one’s ability to learn from one’s mistakes, and one’s ability to use the pain of shame to motivate constructive changes in the future. We tested this mediational model (see Figure 2). As hypothesized, shame exerted a significant positive mediated effect on recidivism via its relation to externalization of blame (indirect effect = .08, p < .01). There remained a marginal negative direct effect of shame to recidivism (β = −.12, p = .052), however – an effect in the opposite direction. Shame unimpeded by defensive externalization of blame exerted an inhibitory effect on recidivism.2 A Wald test of parameter constraints indicated that the indirect effect was significantly different from the direct effect, (χ2(1) = 5.88, p = .015). We also tested this model using shame with guilt residualized out. Model fit indices and path coefficients were virtually identical except that the direct path from the shame residual to recidivism reached statistical significance (β = −.13, p = .028).

Figure 2.

Externalization of blame mediates the link between shame-proneness and recidivism at one-year post-release; shame also has a (negative) direct effect on recidivism at one-year post-release.

Note: Standardized parameter estimates are displayed. Shame = total shame score, OR = Official records, SR = self-report. † p = .052, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Finally, we examined whether different components of shame-proneness might explain the inconsistent mediation effect observed for shame in Figure 2.3 The TOSCA-SD contains two types of shame items (see supplementary online materials for the measure and scoring criteria): For 5 of the scenarios, the shame response reflects negative self-appraisals (e.g., “You would think: ‘I am a disgusting person’”). For 8 of the scenarios, the shame response reflects a motivation to hide or escape (e.g., “You would feel like you wanted to hide”). Tangney et al. (2011) concluded that it was reasonable to combine the two types of items into a single index of shame-proneness because the subscales were positively correlated (r = .35) and the total shame scale demonstrated acceptable reliability, higher than each of the separate subscales. Nonetheless, as there is substantial unique variance in these two constituents of shame, we tested the model in Figure 2 substituting the subscales in turn for the total shame-proneness scale. The inconsistent mediation effect observed for total shame was almost entirely driven by the items assessing the motivation to hide or escape. For the model with the Shame Behavioral Avoidance subscale, the mediated effect was significant (indirect effect = .13, p < .01) as was the direct effect (β = −.18, p < .01). In contrast, when the model employed the Shame Negative Self-Appraisal subscale, neither the mediated effect (indirect effect = .02, p = .08) nor the direct effect (β = −0.03, p = .55) reached conventional levels of significance. (See supplementary online materials for Behavioral Avoidance and Negative Self-Appraisal models.)

Discussion

Inmates’ propensity to experience guilt, assessed shortly upon incarceration, negatively predicted criminal recidivism during the first year post-release. Results from this diverse high-risk sample further underscore the adaptive functions of guilt previously observed in college students and low-risk samples (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994; Cohen, Panter, & Turan, 2012; Tangney, 1990; Tangney, Stuewig & Mashek, 2007). Inmates prone to feelings of guilt about specific behaviors are less likely to subsequently reoffend than their less guilt-prone peers.

The pattern of results regarding shame is an example of what MacKinnon (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007; MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000) terms “inconsistent mediation” – that is, a special case of partial mediation where the direct effect is opposite in sign from the indirect effect via a mediator. Bivariate models that do not include the mediator are apt to mask such a complex pattern of influences, yielding apparently null effects, as two distinct pathways essentially cancel one another out.

At the bivariate level, shame does not appear to influence criminal re-offense one way or the other (Figure 1). But, in fact, much more nuanced processes are at play (Figure 2). The propensity to experience shame is in some ways a liability and in other ways a potential strength. On one hand, shame-proneness is a liability in the sense that it prompts people to blame others rather than taking responsibility for their failures and transgressions, and this externalization of blame is a risk factor for recidivism. Failing to take responsibility, blaming others, ex-offenders are apt to continue doing the same thing – in this case crime. On the other hand, there was a direct negative effect from shame to subsequent recidivism. Another more adaptive process is also at play.

Follow-up analyses indicated that it was primarily the motivation to hide associated with shame, not global negative self-appraisals, per se, that accounted for these two distinct pathways. Theoretically, the cognitive-affective experience of shame (negative self-appraisals) motivates the action tendency to hide or avoid. In this sense, behavioral avoidance is more proximal to other more “downstream” ramifications (e.g., criminal recidivism) relative to the initial experience of shame. Thus, it is not surprising that the most pronounced pattern of effects were observed for the more proximal behavioral avoidance component of shame. It was behavioral avoidance in particular which directly inhibited recidivism, and which indirectly facilitated recidivism via externalization of blame.

Further research is needed to clarify the mechanism(s) by which behavioral avoidance directly inhibits recidivism. It may be that upon release, shame-prone ex-offenders are inclined to withdraw from others – both prosocial and antisocial peers – thus reducing the likelihood of re-offense. Another possibility is that, relative to their less shame-prone peers, shame-prone ex-offenders withdraw, use the downtime to rethink, and in doing so better anticipate shame at the thought of future involvement in the criminal justice system, thereby inhibiting re-offense.

Yet another possibility is that shame prompts both defensive and prosocial motives. Recently, Gausel, Leach, Vignoles, and Brown (2012) astutely observed that although few researchers have discussed shame’s positive motivations, there is a surprising amount of evidence buried in the literature linking shame to motivations to repair, apologize and reform (e.g., de Hooge, Breugelmans, & Zeelenberg, 2008; de Hooge, Zeelenberg, & Bruegelmans, 2010, at the individual level, and Gausel et al., 2012, at the group or collective level). Gausel et al. (2012) assert that this consistent association between shame and prosocial motivations “challenges the prevailing view of shame as self-defensive in nature” (p. 943). Our findings underscore that the issue is not whether shame is defensive or prosocial in nature. Rather, the model indicates that shame has both a defensive pathway (here defined as externalization of blame) and a potentially prosocial pathway in regards to criminal recidivism.

These results add substantially to the emotions and criminology literatures, providing empirical evidence of two faces of shame. For several decades, social-personality psychologists (Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Tangney et al., 2007), clinicians (Gilbert & Irons, 2005; Lewis, 1971; Potter-Efron, 2002; Teyber, McClure, & Weathers, 2011) and the addictions self-help authors (e.g., Bradshaw, 1988) have emphasized the dark, destructive side of shame in modern society. The possibility that shame could be harnessed for social good is tantalizing. A promising direction for future research is to examine whether interventions aimed at decreasing defensive responses (e.g., motivational interviewing, acceptance-based therapies) are effective in helping people from many walks of life make constructive use of the pain of shame.

The implications of inmates’ propensity to experience guilt were much clearer and highlight the adaptive functions of guilt (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994; Stuewig et al., 2010; Tangney, 1990): inmates’ proneness to guilt negatively predicted recidivism during the first year post-release in a direct fashion, without the defensive baggage associated with shame. Thus, “guilt-inducing, shame-reducing” interventions guided by restorative justice principles (e.g., Malouf, Youman, Harty, Schaefer, & Tangney, 2013) may be especially promising for reducing criminal recidivism and for enhancing post-release community adjustment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant #R01 DA14694 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to June P. Tangney and Jeffrey Stuewig. We are grateful for the assistance of the members of the Human Emotions Research Lab and the inmates who participated in our study.

Footnotes

To assess the robustness of the model, we residualized out age, gender (0 = female, 1 = male), race (0 = nonwhite, 1 = white), and years of education from both guilt-proneness and shame-proneness (cf. Sidanius, Van Laar, Levin, & Sinclair, 2004 for use of a similar strategy) and repeated the analysis. Path coefficients and indices of fit were virtually identical. Guilt-proneness remained a significant predictor of recidivism; shame was not.

Paralleling Model 1, we assessed the robustness of Model 2 by residualizing out the demographic covariates from shame. Path coefficients and indices of fit were virtually identical except that the direct effect from shame to recidivism was significant (β = −.12, p = .048)

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this excellent suggestion.

Authorship

J.P. Tangney and J. Stuewig contributed to the study design and developed the research questions. J.P. Tangney wrote the first draft and J. Stuewig and A.G. Martinez provided critical input on conceptualizing results and more general revisions. J.P. Tangney and J. Stuewig supervised data collection and all authors performed data analysis. All three authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

References

- Bear GG, Uribe-Zarain X, Manning MA, Shiomi K. Shame, guilt, blaming, and anger: Differences between children in Japan and the US. Motivation and Emotion. 2009;33:229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Stillwell AM, Heatherton TF. Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:243–267. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J. Healing the shame that binds you. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, St Amand MD, Zamble E. The dynamic prediction of criminal recidivism: A three-wave prospective study. Law and Human Behavior. 2009;33:25–45. doi: 10.1007/s10979-008-9139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TR, Panter AT, Turan N. Guilt Proneness and moral character. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2012;21:355–359. [Google Scholar]

- De Hooge IE, Breugelmans SM, Zeelenberg M. Not so ugly after all: When shame acts as a commitment device. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:933–943. doi: 10.1037/a0011991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hooge IE, Zeelenberg M, Breugelmans SM. Moral sentiments and cooperation: Differential influences of shame and guilt. Cognition and Emotion. 2007;21:1025–1042. [Google Scholar]

- De Hooge IE, Zeelenberg M, Breugelmans SM. Restore and protect motivations following shame. Cognition and Emotion. 2010;24:111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Gausel N, Leach CW, Vignoles VL, Brown R. Defend or repair? Explaining responses to in-group moral failure by disentangling feelings of shame, rejection, and inferiority. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102:941–960. doi: 10.1037/a0027233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, Irons C. Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self attacking. In: Gilbert P, editor. Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 263–325. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RK, Tangney JP. Corrections Research. Department of the Solicitor General of Canada; Ottawa: 1996. The Test of Self-Conscious Affect—Socially Deviant Populations (TOSCA-SD) [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA, Martin SS, Butzin CA. Five-year outcomes of therapeutic community treatment of drug-involved offenders after release from prison. Crime & Delinquency. 2004;50:88–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T, Au WT. The effects of feelings of guilt on the behavior of uncooperative individuals in repeated social bargaining games: An affect-as-information interpretation of the role of emotion in social interaction. Cognition & Emotion. 2003;17:429–453. doi: 10.1080/02699930143000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HB. Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York: International Universities Press; 1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyten P, Fontaine JRJ, Corveleyn J. Does the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA) measure maladaptive aspects of guilt and adaptive aspects of shame? An empirical investigation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;33:1373–1387. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouf E, Youman K, Harty L, Schaefer K, Tangney JP. Accepting guilt and abandoning shame: A positive approach to addressing moral emotions among high-risk, multineed individuals. In: Kashdan TB, Ciarrochi J, editors. Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being. Oakland, CA: Context; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Potter-Efron R. Shame, guilt, and alcoholism: Treatment issues in clinical practice. 2. New York: Haworth Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh S, Janoff-Bulman R. The “shoulds” and “should nots” of moral emotions: A self-regulatory perspective on shame and guilt. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:213–224. doi: 10.1177/0146167209356788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J, Van Laar C, Levin S. Ethnic enclaves and the dynamics of social identity on the college campus: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:96–110. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuewig J, Tangney JP, Heigel C, Harty L, McCloskey LA. Shaming, blaming, and maiming: Functional links among the moral emotions, externalization of blame, and aggression. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP. Assessing individual differences in proneness to shame and guilt: Development of the self-conscious affect and attribution inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:102–111. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Barlow DH, Wagner PE, Marschall D, Borenstein JK, Sanftner J, Gramzow R. Assessing individual differences in constructive vs. destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:780–796. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Dearing R. Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek DJ. Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:345–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek D, Hastings ME. Assessing jail inmates’ proneness to shame and guilt: Feeling bad about the behavior or the self? Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2011;38:710–734. doi: 10.1177/0093854811405762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Fletcher C, Gramzow R. Shamed into anger? The relation of shame and guilt to anger and self-reported aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:669–675. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyber E, McClure FH, Weathers R. Shame in families: Transmission across generations. In: Dearing RL, Tangney JP, editors. Shame in the therapy hour. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wicker FW, Payne GC, Morgan RD. Participant descriptions of guilt and shame. Motivation and Emotion. 1983;7:25–39. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.