Abstract

Cancer cells induce a set of adaptive response pathways to survive in the face of stressors due to inadequate vascularization1. One such adaptive pathway is the unfolded protein (UPR) or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response mediated in part by the ER-localized transmembrane sensor IRE12 and its substrate XBP13. Previous studies report UPR activation in various human tumors4-6, but XBP1's role in cancer progression in mammary epithelial cells is largely unknown. Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), a form of breast cancer in which tumor cells do not express the genes for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and Her2/neu, is a highly aggressive malignancy with limited treatment options7, 8. Here, we report that XBP1 is activated in TNBC and plays a pivotal role in the tumorigenicity and progression of this human breast cancer subtype. In breast cancer cell line models, depletion of XBP1 inhibited tumor growth and tumor relapse and reduced the CD44high/CD24low population. Hypoxia-inducing factor (HIF)1α is known to be hyperactivated in TNBCs 9, 10. Genome-wide mapping of the XBP1 transcriptional regulatory network revealed that XBP1 drives TNBC tumorigenicity by assembling a transcriptional complex with HIF1α that regulates the expression of HIF1α targets via the recruitment of RNA polymerase II. Analysis of independent cohorts of patients with TNBC revealed a specific XBP1 gene expression signature that was highly correlated with HIF1α and hypoxia-driven signatures and that strongly associated with poor prognosis. Our findings reveal a key function for the XBP1 branch of the UPR in TNBC and imply that targeting this pathway may offer alternative treatment strategies for this aggressive subtype of breast cancer.

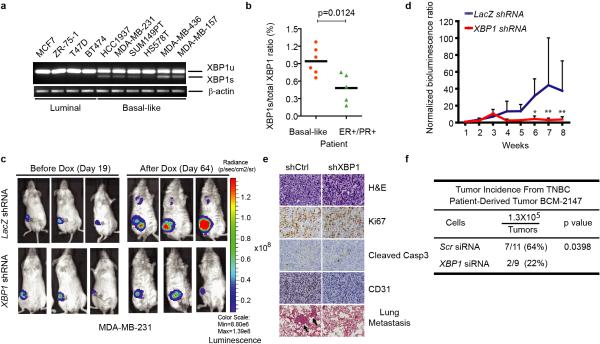

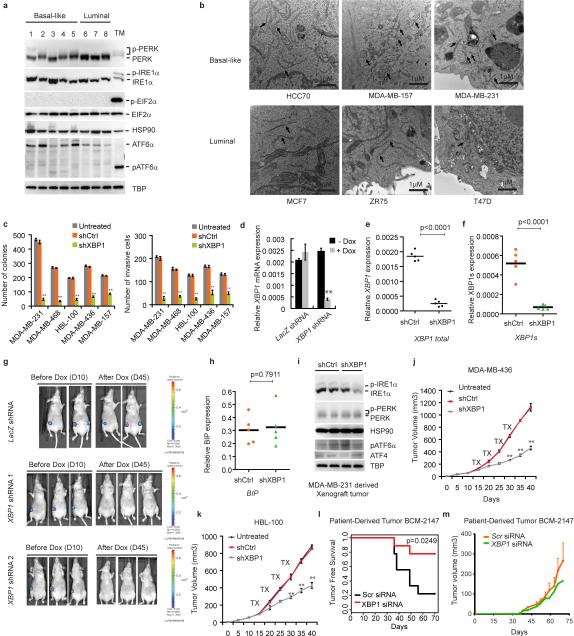

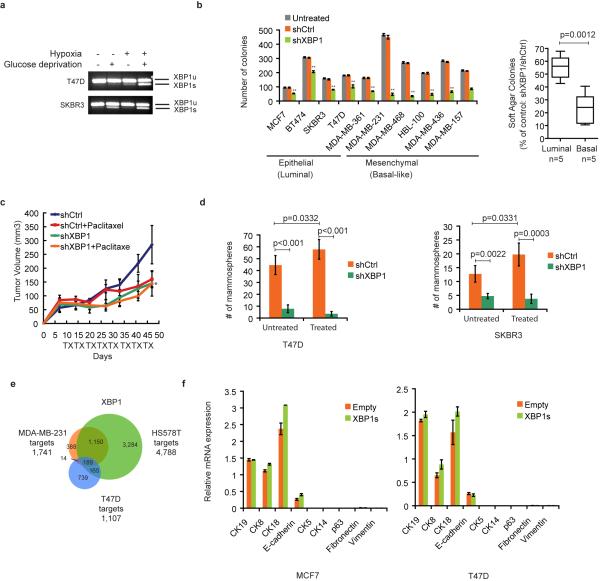

We determined UPR activation status in several breast cancer cell lines (BCCL). XBP1 expression was readily detected in both luminal and basal-like BCCL, but was higher in the latter which consist primarily of TNBC cells and also in primary TNBC patient samples (Fig. 1a, b). PERK but not ATF6 was also activated (Extended Data 1a) and transmission electron microscopy revealed more abundant and dilated ER in multiple TNBC cell lines (Extended Data 1b). These data reveal a state of basal ER stress in TNBC cells.

Figure 1. XBP1 silencing blocks TNBC cell growth and invasiveness.

a-b, RT-PCR analysis of XBP1 splicing in luminal and basal-like cell lines (a) or primary tissues from 6 TNBC patients and 5 ER/PR+ patients (b). XBP1u: unspliced XBP1, XBP1s: spliced XBP1. β-actin was used as loading control. c, Representative bioluminescent images of orthotopic tumors formed by MDA-MB-231 cells as in (Extended Data 1d). Bioluminescent images were obtained 5 days after transplantation and serially after mice were begun on chow containing doxycycline (day 19) for 8 weeks. Pictures shown are the day19 image (Before Dox) and day 64 image (After Dox). d, Quantification of imaging studies as in (c). Data are shown as mean ± SD of biological replicates (n=8). *p<0.05, **p<0.01. e. H&E, Ki67, cleaved Caspase 3 or CD31 immunostaining of tumors or lungs 8 weeks after mice were fed chow containing doxycycline. Black arrows indicate metastatic nodules. f, Tumor incidence in mice transplanted with BCM-2147 tumor cells (10 weeks post-transplantation). Statistical significance was determined by Barnard's test22, 23.

XBP1 silencing impaired soft agar colony forming ability and invasiveness (Extended Data 1c) of multiple TNBC cell lines, indicating that XBP1 regulates TNBC anchorage-independent growth and invasiveness. We next used an orthotopic xenograft mouse model with inducible expression of two XBP1 shRNAs in MDA-MB-231 cells. Tumor growth and metastasis to lung were significantly inhibited by XBP1 shRNAs (Fig. 1c-e, Extended Data 1d-g). This was not due to altered apoptosis (Caspase 3), cell proliferation (Ki67) or hyperactivation of IRE1 and other UPR branches (Fig. 1e, Extended Data 1h, i). Instead, XBP1 depletion impaired angiogenesis as evidenced by the presence of fewer intratumoral blood vessels (CD31 staining) (Fig. 1e). Subcutaneous xenograft experiments using two other TNBC cell lines confirmed our findings (Extended Data 1j, k). Importantly, XBP1 silencing in a patient-derived TNBC xenograft model (BCM-2147) significantly decreased tumor incidence (Fig. 1f, Extended Data 1l, m).

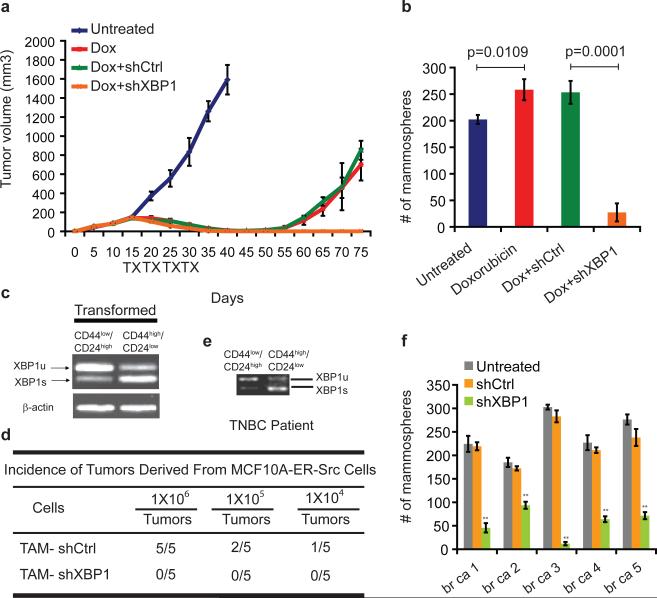

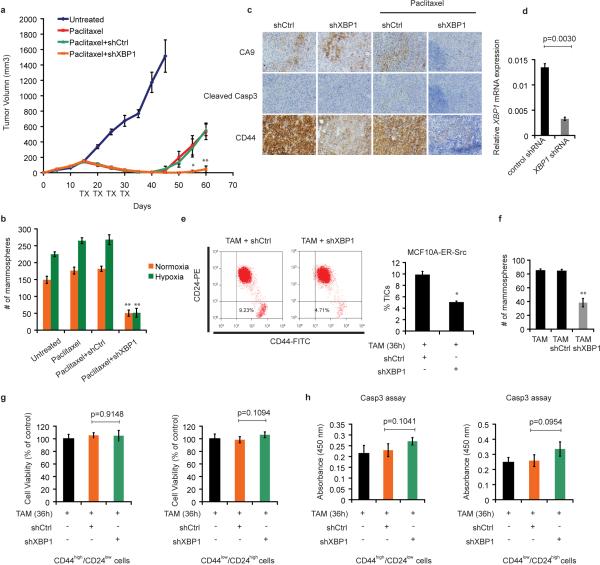

TNBC patients have the highest rate of relapse within 1-3 years despite adjuvant chemotherapy7, 8. To examine XBP1's effect on tumor relapse following chemotherapeutic treatment, we treated MDA-MB-231 xenograft bearing mice with doxorubicin and XBP1 shRNA. Strikingly, combination treatment not only blocked tumor growth but also inhibited or delayed tumor relapse (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. XBP1 is required for tumor relapse and CD44high/CD24lowcells.

a, Tumor growth of MDA-MB-231 cells untreated or treated with doxorubicin (Dox), or Dox + control shRNA, or Dox + XBP1 shRNA in athymic nude mice. Data are shown as mean ± SD of biological replicates (n=5). TX: treatment. b, Number of mammospheres per 1,000 cells generated from day 20 xenograft tumors under different treatments as indicated. Data are shown as mean ± SD of biological replicates (n=3). c, RT-PCR analysis of XBP1 splicing in TAM (tamoxifen) treated CD44low/CD24high and CD44high/CD24low cells. d, The indicated number of TAM-treated MCF10A-ER-Src cells infected with control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA were injected into NOD/SCID/IL2Rγ -/- mice and the tumor incidence reported at 12 weeks post-transplantation. e, RT-PCR analysis of XBP1 splicing in CD44low/CD24high and CD44high/CD24low cells purified from a TNBC patient. f, Number of mammospheres per 1,000 cells generated from untreated and control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA encoding lentivirus infected primary tissue samples from five patients with TNBC. Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates.

Tumor cells expressing CD44high/CD24low have been shown to mediate tumor relapse in some instances11-13. To test whether XBP1 targeted the CD44high/CD24low population, we examined the mammosphere-forming ability of cells derived from treated tumors (day 20). Mammosphere formation was increased in doxorubicin treated tumor cells, while tumors treated with doxorubicin plus XBP1 shRNA displayed substantially reduced mammosphere formation (Fig. 2b), a finding confirmed using another chemotherapeutic agent, paclitaxel (Extended Data 2a, b). Hypoxia activates the UPR, and XBP1 knockdown also dramatically reduced mammosphere formation in hypoxic conditions (Extended Data. 2b). Furthermore, CD44 expression was reduced in XBP1-depleted tumors (Extended Data 2c).

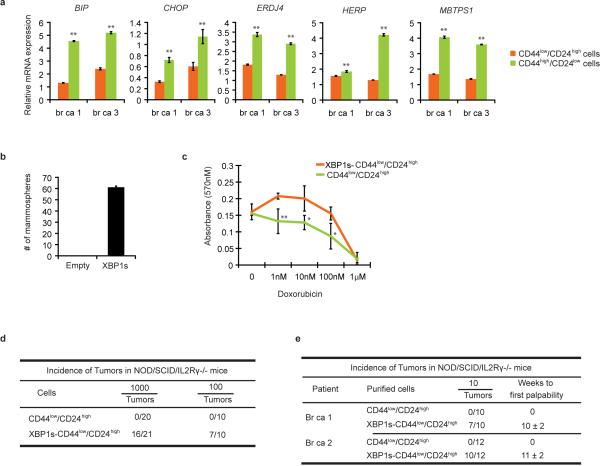

To further interrogate XBP1's effect on CD44high/CD24low cell function, we used mammary epithelial cells (MCF10A) carrying an inducible Src oncogene (ER-Src), where v-Src is fused with the estrogen receptor ligand binding domain14. Tamoxifen (TAM) treatment results in neoplastic transformation and gain of a CD44high/CD24low population that has been previously associated with tumor-initiating properties15. In transformed MCF10A-ER-Src cells, XBP1 splicing was increased in CD44high/CD24low population (Fig. 2c), while XBP1 silencing reduced the CD44high/CD24low fraction (Extended Data 2d, e) and markedly suppressed mammosphere formation (Extended Data 2f), phenotypes not attributable to a direct effect of XBP1 on cell viability (Extended Data 2g, h). Furthermore, limiting dilution experiments demonstrated loss of tumor-seeding ability in XBP1-depleted cells (Fig. 2d). CD44high/CD24low cells sorted from TNBC patient samples confirmed increased XBP1 splicing and other UPR markers, and XBP1 silencing impaired mammosphere-forming ability (Fig. 2e, f, Extended Data 3a). Conversely, XBP1s overexpression in CD44low/CD24high cells resulted in gain of mammosphere-forming ability and increased resistance to doxorubicin treatment (Extended Data 3b, c). Strikingly, patient derived CD44low/CD24high cells overexpressing XBP1s, but not control parental cells, initiated tumor formation in immunodeficient mice (Extended Data 3d, e). These data establish a critical role of XBP1 in CD44high/CD24low cells within TNBC.

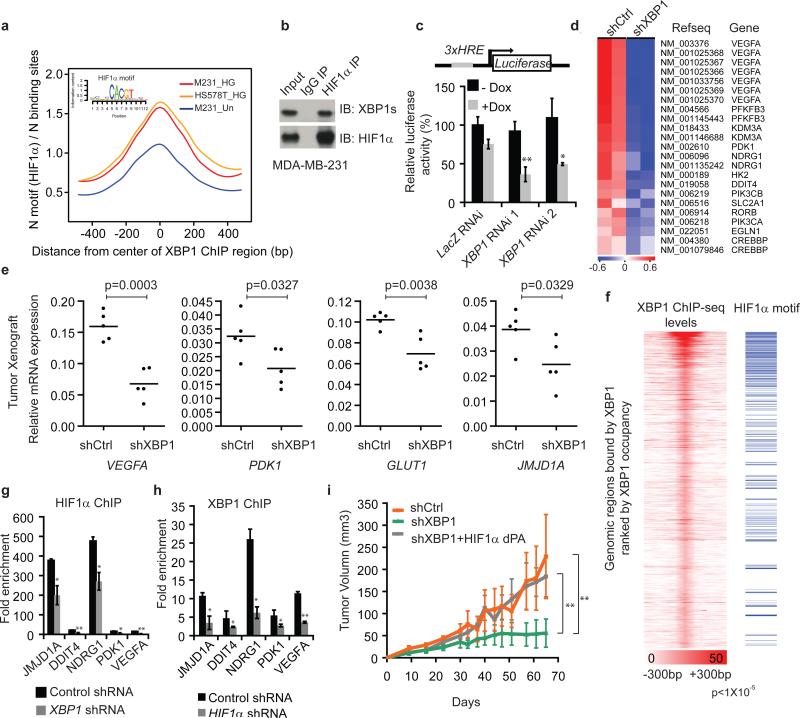

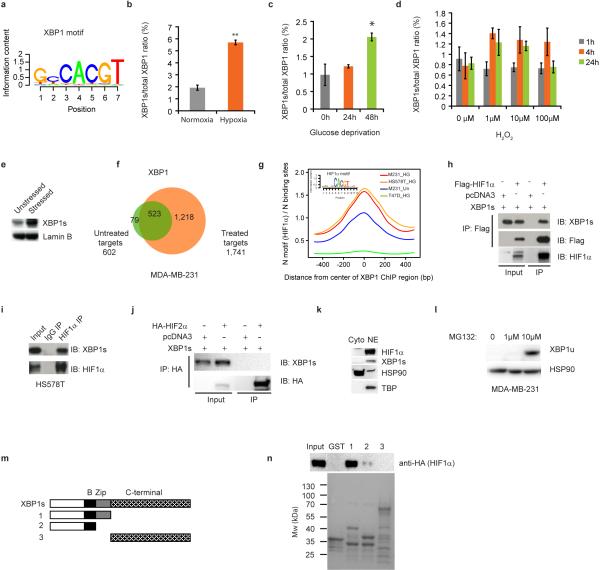

ChIP-seq and motif analysis of XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 cells revealed statistically significant enrichment of both the HIF1α and XBP1 motifs (Fig. 3a, Extended Data 4a), suggesting frequent colocalization of HIF1α and XBP1 to the same regulatory elements. HIF1α is hyperactivated in TNBCs, required for the maintenance of CD44high/CD24low cells9, 10, 16, 17 and regulated in response to microenvironmental oxygen levels. XBP1 ChIP-seq was therefore also performed in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells cultured under hypoxia and glucose deprivation conditions for 24h. Exposure to these stressors increased XBP1 splicing, resulting in a corresponding increase in signal intensity (Extended Data 4b-f) and further enrichment of HIF1α motifs in TNBC (Fig. 3a), but interestingly not in luminal breast cancer cells (Extended Data 4g).

Figure 3. HIF1α is a co-regulator of XBP1.

a, Motif enrichment analysis in the XBP1 binding sites in untreated or stressed (0.1% O2 and glucose deprivation: HG) MDA-MB-231 or Hs578T cells. The 1kb region surrounding the summit of the XBP1 peak is equally divided into 50 bins. The average HIF1α motif occurrence over top 1000 XBP1 peaks in each bin is plotted. The corresponding p-values of each condition: M231_UN: 7.78×10-20; M231_HG: <1.08×10-30; Hs578T_HG: <1.08×10-30. b, Nuclear extracts from MDA-MB-231 cells (treated with 0.1% O2 for 10h first and then with 1μg/ml tunicamycin for another 6 hours in 0.1% O2) were subjected to co-IP with anti-HIF1α antibody or rabbit IgG. c, Schematic of the luciferase reporter constructs. 3xHRE reporter was co-transfected with doxycycline (DOX) inducible constructs encoding control or two XBP1 shRNAs into MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated in 0.1% O2 for 24h and luciferase activity assayed. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. d, Gene expression microarray heatmap showing that genes involved in the HIF1α mediated hypoxia response were differentially expressed after XBP1 knockdown. e, RT-PCR analysis of HIF1α target genes expression after knockdown of XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 derived xenograft tumors in NOD/SCID/IL2γ-/- mice. Results are presented relative to β-actin expression. n=5. f, Plot showing the genome-wide association between the strength of XBP1 binding and the occurrence of the HIF1α motif. The signal of XBP1 ChIP-seq peaks is shown as a heatmap using red (the strongest signal) and white (the weakest signal) color scheme. Each row shows ±300 bp centered on the XBP1 ChIP-seq peak summits. Rows are ranked by XBP1 occupancy. The horizontal blue lines denote the presence of the HIF1α motif. g-h, Chromatin extracts from control, XBP1 knockdown (g) or HIF1α knockdown (h) MDA-MB-231 cells (treated with 0.1% O2 for 24h) were subjected to ChIP using anti-HIF1α (g) or anti-XBP1 antibodies (h). Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. Results show a representative of two independent experiments. i. Growth curve of tumors formed by MDA-MB-231 cells infected with inducible control shRNA (shCtrl), XBP1 shRNA (shXBP1) or XBP1 shRNA plus constitutively activated HIF1α (shXBP1+HIF1α dPA). Mice were fed with doxycycline chow from day 7. Data are shown as mean ± SD of biological replicates (n=5). *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

HIF1α motif enrichment in the XBP1 ChIP-seq dataset suggested that XBP1 and HIF1α might interact within the same transcriptional complex. Co-IP experiments revealed a physical interaction of HIF1α, but not HIF2α, with XBP1 in 293T cells co-expressing HIF1 and XBP1s cultured under hypoxic conditions, also observed with endogenous proteins in two TNBC cell lines: MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T (Fig. 3b, Extended Data 4h-j). Subcellular fractionation revealed that this interaction occurs in the nucleus, and that unspliced XBP1u protein was not detectable (Extended Data 4k, l). GST pull-down experiments showed that HIF1α interacts with the XBP1s N-terminus b-zip domain (Extended Data 4m, n).

We next established that XBP1 and HIF1α co-occupied several well-known HIF1α targets using ChIP-qPCR (Extended Data 5a-c). ChIP-re-ChIP assays using anti-XBP1s followed by anti-HIF1α antibodies confirmed that XBP1s and HIF1α simultaneously co-occupy these common targets (Extended Data. 5d). DNA-pull down assays with an HIF1α18 specific probe precipitated XBP1s in MDA-MB-231 nuclear extracts under hypoxia, indicating their presence in the same complex (Extended Data 5e, f). XBP1 depletion by two independent shRNA constructs dramatically reduced hypoxia response element (HRE) luciferase activity under hypoxia (Fig. 3c). Conversely, XBP1s expression dose-dependently transactivated the HRE reporter (Extended Data 5g, h), confirming that XBP1 augments HIF1α activity.

When we profiled the differential transcriptome induced by XBP1 silencing in MDA-MB-231 cells, gene set enrichment analysis identified significant enrichment of HIF1α mediated hypoxia response pathway genes (Fig. 3d, Extended Data 6a). XBP1 depletion downregulated HIF1α targets VEGFA, PDK1, GLUT1, and DDIT4 expression in both normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Extended Data 6b), and these results were validated in breast cancer xenografts (Fig. 3e) and Hs578T cells (Extended Data 6c). However, XBP1 depletion in luminal tumors did not affect these targets (Extended Data 6d).

To further explore the consequences of this cooperation, we examined how XBP1 or HIF1α loss affected the transcription of common target genes. We found that high occupancy by XBP1 was associated with increased occurrence of the HIF1α motif across the genome in TNBC (Fig. 3f). While XBP1 depletion had no immediate effect on HIF1α expression, it substantially attenuated concurrent HIF1α and RNA polymerase II occupancy (Extended Data 6e-g, Fig. 3g). Similarly, XBP1 and RNA Polymerase II occupancy at co-bound sites was likewise reduced in the absence of HIF1α under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3h, Extended Data 6h-l). These results indicate that the assembly of the XBP1-HIF1α complex on target promoters is crucial for their transcription, via the recruitment of RNA polymerase II.

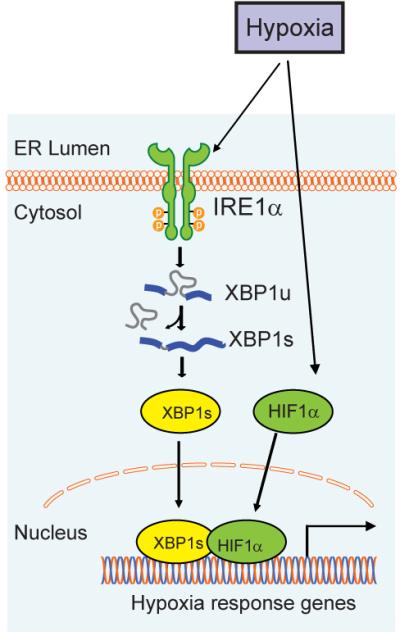

To establish whether HIF1α contributes to XBP1's function in TNBC, we performed rescue experiments using a HA-tagged constitutively activated hydroxylation-mutant HIF1α construct (HA-HIF1α dPA: P402A/P564A). XBP1 splicing was not directly regulated by HIF1α (Extended Data 7a-c). Enforced overexpression of HIF1α dPA in XBP1 depleted cells restored expression of HIF1α targets and rescued anchorage independent growth, mammosphere-forming ability, angiogenesis and in vivo tumor growth (Fig. 3i; Extended Data 7d-h). Conversely, HIF1α silencing in XBP1s overexpressing cells dramatically compromised their ability to sustain mammosphere formation (Extended Data 7i). Hypoxia is a physiological UPR inducer in cancer19and XBP1s co-localizes with hypoxia marker CA9 in tumors20. Our experiments demonstrate that XBP1 functions to sustain the hypoxia response via regulating the HIF1α transcriptional program (Extended Data 8), which ensures maximum HIF activity and adaptive responses to the cytotoxic microenvironment of solid tumors.

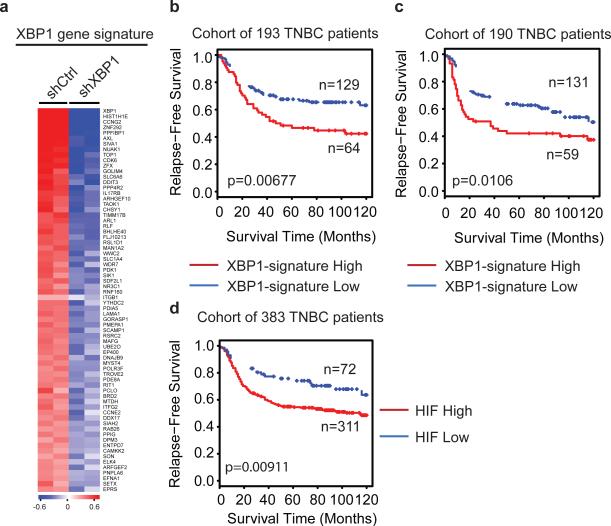

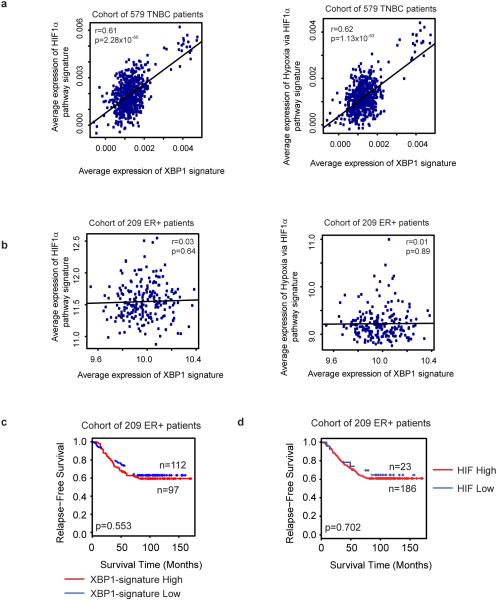

Integrated analysis of XBP1 ChIP-seq data and gene expression profiles identified 96 genes directly bound and up-regulated by XBP1. This gene set was defined as the XBP1 signature (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table 1). Its expression was highly correlated with hypoxia-driven signatures in TNBC (Pearson's correlation coefficient=0.61; p=2.28×10-60), but not in ER+ breast cancer patients (coefficient=0.03; p=0.64) (Extended Data 9a, b). Survival analysis using an aggregate breast cancer dataset for 193 TNBC patient samples21 demonstrated that tumors with an elevated XBP1 signature displayed shorter relapse-free survival (Log-rank test, p =0.00677) (Fig. 4b). Cox regression analysis showed that association of the signature with relapse free survival remained significant after controlling for tumor size, grade and chemotherapy treatment (p=0.00453, Supplementary Table 2). These findings were validated in a separate cohort of 190 TNBC patients (Fig. 4c). Importantly, the XBP1 signature did not correlate with clinical outcome of ER+ breast cancer patients (p=0.553) (Extended Data 9c), indicating its specific prognostic value for TNBC. Expression of the XBP1-regulated HIF1α program was also associated with decreased relapse free survival only in TNBC (p=0.00911) (Fig. 4d, Extended Data 9d). Although XBP1 silencing also affects luminal breast cancer growth, it does so via a mechanism not involving HIF1α (Extended Data 10, 4g, 6d).

Figure 4. XBP1 genetic signature is associated with human TNBC prognosis.

a, Heatmap showing the expression profile of genes bound by XBP1 and differentially expressed after XBP1 knockdown. b,c, Kaplan-Meier graphs demonstrating a significant association between elevated expression of the XBP1 signature (red line) and shorter relapse free survival in two cohorts of patients with TNBC (b, and c). d, Kaplan-Meier graphs showing significant association of elevated HIF1α gene signature expression (red line) with shorter relapse free survival in a cohort of 383 TNBC patients. The log-rank test P values are shown.

In conclusion, we uncover a key function for XBP1 in the tumorigenicity, progression and recurrence of TNBC and identified XBP1's control of the HIF1α transcriptional program as the major mechanism. XBP1 pathway activation correlates with poor patient survival in TNBC patients implying that UPR inhibitors in combination with standard chemotherapy may improve the effectiveness of anti-tumor therapies.

METHODS

Cell Culture And Treatments

The non-transformed breast cell line MCF10A contains an integrated fusion of the v-Src oncoprotein with the ligand-binding domain of the estrogen receptor (ER-Src). These cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 5% donor horse serum (Invitrogen), 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF) (R&D systems), 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), 100 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma), 100 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma), 50 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), with the addition of puromycin (Sigma). Src induction and cellular transformation was achieved by treatment with 1 μM 4-OH tamoxifen (TAM), typically for 36h as described previously14.

All breast cancer cells were from ATCC cultured according to Neve et al.24. Following retroviral or lentiviral infection, cells were maintained in the presence of puromycin (2 μg/ml) (Sigma). For all hypoxia experiments, cells were maintained in an anaerobic chamber (Coy laboratory) with 0.1% O2. For glucose deprivation experiments, cells were maintained in DMEM without glucose medium (Gibco) with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 50 units/ml of penicillin/streptomycin.

ChIP and ChIP-seq

ChIP was performed with XBP1 antibody (Biolegend, 619502); HIF1α antibody (Abcam, ab2185), RNA Polymerase II antibody (Millipore, 05-623) or GST antibody (santa cruz, sc-33613) as described25. See list of primers used in Fig. 3 (Supplementary Table 3). ChIP-seq libraries were prepared using ChIP-Seq DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina). XBP1 ChIP-seq peaks were first identified using MACS package with a p-value cutoff of 1×10-7 on individual replicate. Correlations of the ChIP-seq signal in the union peak regions between two biological replicates are: MDA-MB-231_untreated: 0.97 (p<2.2×10-16); MDA-MB-231_HG: 0.96 (p<2.2×10-16); Hs578T_HG: 0.98 (p<2.2×10-16); T47D_HG: 0.99 (p<2.2×10-16). The correlations were calculated by cor.test() function in R (http://www.r-project.org/). The highly confident common peaks between replicates were further identified using an irreproducible discovery rate (IDR) cutoff of 20%. IDR is a statistical measure that assesses the consistency of the rank orders of the common ChIP-seq peaks between two replicates. The methodology and details of the implementation of IDR can be found in26.

Tumor Initiation Assay Using Patient-Derived Tumors

Tumorgraft line BCM-2147 was derived by transplantation of a fresh patient breast tumor biopsy (ER-PR-HER2-) into the cleared mammary gland fat pad of immune-compromised SCID/Beige mice and retained the patient biomarker status and morphology across multiple transplant generations in mice. To overcome the challenge of limited cell viability by dissociation of solid tumors, 10 mg tumor pieces containing 1.3 × 105 cells were transplanted with basal membrane extract (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). The cell number was calculated as average cell yield 1.3 × 107 cells/gram × 0.01 gram = 1.3 × 105 cells. For sustained siRNA release in the first two weeks following transplantation, porous silicon particles loaded with siRNA (scrambled control or XBP1 siRNA) packaged in nanoliposomes were injected into the tumor tissue with basal membrane extract at the time of transplantation. Scrambled sequence [5’ CGAAGUGUGUGUGUGUGGCdTdT 3’]; XBP1 siRNA sequence [5’ CACCCUGAAUUCAUUGUCUdTdT 3’]. Two weeks post-transplantation, nanoliposomes containing siRNA (15mg per mouse) were injected I.V. twice weekly for 8 weeks. Mice were monitored thrice weekly for tumor development, and tumors were calipered and recorded using LABCAT Tumor Analysis and Tracking System v6.4 (Innovative Programming Associates, Inc., Princeton, NJ). Tumor incidence is reported at 10 weeks post-transplantation. The human patient samples were procured and utilized according to approved IRB protocols for research in human subjects.

Invasion Assay

We performed invasion assays according to14. Invasion of the matrigel was conducted by using standardized conditions with BD BioCoat growth factor reduced MATRIGEL invasion chambers (PharMingen). Assays were conducted according to manufacturer's protocol, by using 5% horse serum (GIBCO) and 20 ng/ml EGF (R&D Systems) as chemoattractants.

Colony Formation Assay

1×105 breast cancer cells were mixed 4:1 (v/v) with 2.0% agarose in growth medium for a final concentration of 0.4% agarose. The cell mixture was plated on top of a solidified layer of 0.8% agarose in growth medium. Cells were fed every 6 to 7 days with growth medium containing 0.4% agarose. The number of colonies was counted after 20 days. The experiment was repeated three times and the statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test.

Subcutaneous Xenograft Experiments

MCF10A ER-Src TAM-treated (36h) cells or MDA-MB-436 or HBL-100 breast cancer cells were injected subcutaneously in the right flank of athymic nude mice (Charles River Laboratories). Tumor growth was monitored every five days and tumor volumes were calculated by the equation V(mm3)=axb2/2, where a is the largest diameter and b is the perpendicular diameter. When the tumors reached a size of ~100mm3 (15 days) mice were randomly distributed into 3 groups (5 mice/group). The first group was used as control (non-treated), the second group was intratumorally treated with shCtrl and the third group was intratumorally treated with shXBP1. For each injection 10ug of shRNA was mixed with 2ul of vivo-jetPEI (polyethylenimine) reagent (cat. no 201-50G, PolyPlus Transfection SA) in a final volume of 100ul. These treatments were repeated every five days for 4 cycles (days 15, 20, 25, 30). In addition, in vivo dilution xenotransplantation assays were performed in NOD/SCID/IL2Rγ-/- mice. Mice were evaluated on a weekly basis for tumor formation. All mice were maintained in accordance with Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee procedures and guidelines.

Purification of CD44high/CD24low and CD44low/CD24high Cells From Patients with TNBC

Five human invasive triple negative ductal carcinoma tissues (stage III) were used in our experiments15. Immunomagnetic purification of CD44high/CD24low and CD44low/CD24high cells was performed according to Shipitsin et al27. Briefly, the breast tissues were minced into small pieces (1mm) using a sterile razor blade. The tissues were digested with 2mg/ml collagenase I (C0130, Sigma) and 2mg/ml hyalurinidase (H3506, Sigma) in 37°C for 3h. Cells were filtered, washed with PBS and followed by Percoll gradient centrifugation. The first purification step was to remove the immune cells by immunomagnetic purification using an equal mix of CD45 (leukocytes), CD15 (granulocytes), CD14 (monocytes) and CD19 (B cells) Dynabeads (Invitrogen). The second purification step was to isolate fibroblasts from the cell population by using CD10 beads for magnetic purification. The third step was to isolate the endothelial cells by using an “endothelial cocktail” of beads (CD31 BD Pharmingen cat no. 555444, CD146 P1H12 MCAM BD Pharmingen cat no. 550314, CD105 Abcam cat no. Ab2529, Cadherin 5 Immunotech cat no. 1597, and CD34 BD Pharmingen cat no. 555820). In the final step the CD44high cells were purified from the remaining cell population using CD44 beads. These cells were sorted for CD44high/CD24low cells, CD24high cells were also purified using CD24 beads. These cells were sorted for CD44low/CD24high cells. These cell populations were sorted again with CD44 antibody (FITC-conjugated) (555478, BD Biosciences) and CD24 antibody (PE-conjugated) (555428, BD Biosciences) in order to increase their purity (>99.2% in all cases).

Gene Expression Microarray Analysis

MDA-MB-231 cells infected with control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA lentiviruses grown in glucose free medium were treated in 0.1% O2 in a hypoxia chamber for 24h. Total RNA was extracted by using RNeasy mini kit with on column DNase digestion (QIAGEN). Biotin labeled cRNA was prepared from 1 μg of total RNA, fragmented, and hybridized to Affymetrix human U133 plus 2.0 expression array. All Gene expression microarray data were normalized and summarized using RMA. The differentially expressed genes were identified using Limma (q ≤10%).

Motif Analysis

Flanking sequences around the summits (±300 bp ) of the top 1,000 XBP1 binding sites were extracted and the repetitive regions in these flanking sequences were masked. The consensus sequence motifs were derived using Seqpos.

XBP1 Signature Generation

The XBP1 signature was generated by integrative analysis of of ChIP-seq and differential expression data using the method as previously described28. Briefly, we first calculated the regulatory potential for a given gene, Sg, as the sum of the nearby binding sites weighted by the distance from each site to the TSS of the gene: , where k is the number of binding sites within 100 kb of gene g and Δi is the distance between site i and the TSS of gene g normalized to 100 kb (e.g., 0.5 for a 50 kb distance). We then applied the Breitling's rank product method to combine regulatory potentials with differential expression t-values to rank all genes based on the probability that they were XBP1 targets. Only genes with at least one binding site within 100 kb from its TSS and a differential expression t-value above the 75th percentile were considered. The FDR of XBP1 target prediction was estimated by permutation. At a FDR cutoff of 20% and differential expression fold-change cutoff of 1.5, we obtained 96 up-regulated genes (HUGO gene symbol) as direct targets of XBP1.

Survival Analysis

We performed survival analysis using an aggregated compendium of gene expression profiles of 383 TNBC samples from 21 breast cancer datasets21. Of the 96 XBP1 signature genes, 70 genes had corresponding probes in this dataset. To avoid potential confounding factors such as heterogeneity among the samples, we randomly split all 383 TNBC samples into two datasets with similar size (193 and 190 cases) and evaluated the correlation of the XBP1 gene signature with relapse free survival using these two datasets respectively. We separated patients into two subgroups: one with higher and the other with lower expression of the XBP1 signature. The subgroup classification was performed as described previously29. Patients were considered to have a higher XBP1 signature if they had average expression values of all the genes in the XBP1 signature above the 58th percentile29. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed and log-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance of survival difference between these 2 groups. We also performed multivariate Cox regression analysis to evaluate the significance of the association between XBP1 signature and relapse-free survival in the presence of other clinical variables including tumor stage, tumor grade and the treatment with chemotherapy. A similar analysis was performed for the HIF pathway signature (VEGFA, PDK1, DDIT4, SLC2A1, KDM3A, NDRG1, PFKFB3, PIK3CA, RORB, CREBBP, PIK3CB, HK2 and EGLN1). Similar to the analysis for TNBC, the survival analysis was performed for ER+ breast cancer using gene expression profiles and clinical annotations of 209 ER+ breast cancer patients30.

Virus Production and Infection

The Phoenix packaging cell line was used for the generation of ecotropic retroviruses and the 293T packaging cell line was used for lentiviral amplification. In brief, viruses were collected 48 and 72 hr after transfection, filtered, and used for infecting cells in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene prior to drug selection with puromycin (2 μg/ml). shRNA constructs were generated by The Broad Institute. Targeting of GFP mRNA with shRNA served as a control. Optimal targeting sequences identified for human XBP1 were 5′-GACCCAGTCATGTTCTTCAAA-3′, and 5′- GAACAGCAAGTGGTAGATTTA-3′, respectively. Knockdown efficiency was assessed by real-time PCR for XBP1.

Luciferase Assay

For Fig. 3f, MDA-MB-231 cells were co-transfected with 3×HRE luciferase (3×HRE-Luc) plasmid and XBP1s overexpression construct or control vector by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). A Renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL-CMV from Promega) was co-transfected as an internal control. Cells were harvested 36 hr after transfection, and the luciferase activities of the cell lysates were measured by using the Dual-luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). For Fig. 3e, MDA-MB-231 cells were co-transfected with 3×HRE-Luc and two inducible XBP1 shRNA construct (in pLKO-Tet-On vector) or control shRNA construct by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were treated with doxycycline for 48h and hypoxia for 24h before the luciferase activities of the cell lysates were measured.

Statistical analysis

The significance of differences between treatment groups was measured with a Student's t-test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Transfected cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 10% glycerol with protease inhibitor cocktail) for 1 hour. M2 beads (Sigma) were incubated with the whole cell extracts at 4°C for overnight. The beads were washed with cell lysis buffer four times. Finally, the beads were boiled in 2x sample buffer for 10 minutes. The eluents were analyzed by Western blot. Nuclear extracts were used to perform the endogenous co-IP. Briefly, 5 mg of nuclear extracts were incubated with 5 μg of anti-HIF1α antibody (Novus Biologicals, NB100-479) at 4°C for overnight. The protein complexes were precipitated by addition of protein A agarose beads (Roche) with incubation for 4 hr at 4°C. The beads were washed four times and boiled for 5 min in 2x sample buffer.

Real-time PCR analysis

1 μg of RNA sample was reverse-transcribed to form cDNA, which was subjected to SYBR Green based real-time PCR analysis. Primers used for β-actin forward: 5’-CCTGTACGCCAACACAGTGC-3’ and reverse 5’- ATACTCCTGCTT GCTGATCC-3’; for VEGFA forward 5’- CACACAGGATGGCTTGAAGA -3’ and reverse 5’- AGGGCAGAATCATCACGAAG-3’; for PDK1 forward 5’-GGAGGTCTCAACACGAGGTC -3’ and reverse 5’- GTTCATGTCACGCTGGGTAA -3’; for GLUT1 forward 5’- TGGACCCATGTCTGGTTGTA -3’ and reverse 5’-ATGGAGCCCAGCAGCAA -3’; for JMJD1A forward 5’-TCAGGTGACTTTCGTTCAGC-3’ and reverse 5’- CACCGACGTTACCAAGAAGG-3’; for DDIT4 forward 5’- CATCAGGTTGGCACACAAGT-3’ and reverse 5’-CCTGGAGAGCTCGGACTG-3’; for MCT4 forward 5’-TACATGTAGACGTGGGTCGC – 3’ and reverse 5’ CTGCAGTTCGAGGTGCTCAT – 3’; for XBP1 splicing forward 5’- CCTGGTTGCTGAAGAGGAGG-3’ and reverse 5’-CCATGGGGAGATGTTCTGGAG -3’; for XBP1 total forward 5’-AGGAGTTAAGACAGCGCTTGGGGATGGAT-3’ and reverse 5’-CTGAATCTGAAGAGTCAATACCGCCAGAAT-3’;

ChIP-re-ChIP

XBP1 antibody was cross-linked to protein G-Sepharose beads using dimethylpimelimidate to prevent the leaching of antibody during sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) elution. The beads were then incubated with chromatin extracts overnight. Subsequently, the beads were washed and eluted with 1% SDS elution buffer at 37°C for 45 minutes. The eluate was diluted to a final SDS concentration of 0.1% and incubated with fresh antibody-bound beads for the second immunoprecipitation (IP). For the final round of IP, washed beads were eluted with 1% SDS elution buffer at 68°C for 30 minutes. Eluate was decrosslinked in the presence of pronase and heated at 68°C for 6 hours, and DNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction.

Glutathione S-Transferase Pulldown Assay

Various deletion fragments of XBP1s were cloned into pET42b (Novagen). The plasmids were transformed into BL21 Escherichia coli. The XBP1s proteins were expressed and purified with glutathione (GSH)-Sepharose beads (GE healthcare). The purified proteins were bound to GSH beads and incubated with HIF1α-overexpressed cell lysates for 2 hours in 4°C. The beads were washed six times with cell lysis buffer. The eluents were analyzed by Western blot.

DNA-binding assay

Nuclear protein (150 μg) was incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with a biotinylated probe containing wild-type or mutated HIF1α binding site plus streptavidin-dynabeads (Invitrogen) in binding buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5% glycerol, 1 mg/ml of BSA and 20 μg/ml of poly(dI:dC), plus protease inhibitors). Streptavidin-beads were washed in binding buffer, and bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblot for XBP1s or HIF1α.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Cells were washed with serum-free media then fixed with a modified Karmovsky's fix of 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% parafomaldehye and 0.02% picric acid in 0.1M sodium caocdylate buffer at pH7.2. Following a secondary fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide, 1.5% potassium ferricyanide, samples were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and embedded in situ in an epon analog resin. En face ultrathin sections were cut on a Leica Ultractu S Ultramicrotome (Leica). Sections were collected on copper grids and further contrasted with lead citrate and viewed on a JEM 1400 electron microscope (JEOL, USA, Inc., Peabody, MA) operated at 100 kV. Digital images were captured on a Veleta 2K x 2K CCD camera (Olympus-SIS, Germany).

Caspase 3 ELISA Assay

Quantification of cleaved Caspase-3 activity was performed using the PathScan Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) sandwich ELISA kit (#7190, Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Immunohistochemical Staining

We fixed xenograft tumor tissues in 4% paraformaldehyde and performed immunohistochemistry on 5-μm-thick paraffin sections after heat induced antigen retrieval. The following primary antibodies were used: CD31 (1:50, Abcam, ab28364), Cleaved Caspase 3 (1:200, Cell Signaling, #9664), CD44 (1:100, Novocastra), Ki67 (1:50, Dako, Clone MIB-1), and Carbonic Anhydrase IX (1:40, Novus Biologicals). Subsequently, we incubated the slides with biotinylated secondary antibody and ABC-HRP (both from Vector Lab). EnVision+ system (Dako) was used to amplify Caspase 3 and Carbonic Anhydrase IX. Mouse on Mouse ImmPRESS Polymer Kit (Vector Lab) was applied to increase CD44 signal to noise ratio. For all slides, final detectable signal was visualized by DAB as the location of antigens. After counterstaining with hematoxylin, slides were mounted.

Immunoblot Analysis

Total cell extracts or nuclear extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. IRE1α phosphorylation was monitored by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE. PERK phosphorylation was monitored by 5% SDS-PAGE. The following antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis: anti-XBP1s (BioLegend, 619502); anti-PERK (Cell signaling, #5683); anti-IRE1α (Cell Signaling, #3294); anti-ATF6 (Cosmo bio, BAM-73-500-EX); anti-ATF4 (Santa Cruz, sc-200); anti-Hsp90 (Santa Cruz, sc-7947), anti-TBP (Abcam, 51841); anti-EIF2α (Santa Cruz, sc-11386); anti-phospho-EIF2α (Cell Signaling, #9721).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Effect of XBP1 silencing on TNBC cells and UPR.

a, Activation of UPR in different breast cancer cells. Immunoblot of PERK phosphorylation, IRE1α activation (phos-tag SDS-PAGE), and EIF2α phosphorylation in whole cell lysates, and ATF6α processing (pATF6α) in nuclear extract of basal-like breast cancer cells (1: HCC1937; 2: MDA-MB-231; 3: SUM159; 4: MDA-MB-157; 5: HCC70) and luminal breast cancer cells (6: ZR-75-1; 7: T47D; 8: MCF7). TM: Positive control (whole cell lysates or nuclear extracts from MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 5μg/ml tunicamycin for 6 hours). HSP90 was used as loading control for whole cell lysates, TBP was used as loading control for nuclear extract. b, Transmission electron microscopic analysis of ER in basal-like and luminal breast cancer cell lines. Black arrows indicate the endoplasmic reticulum. All images are at 30,000× magnification. Scale bar represents 1μM. c, Quantification of soft agar colony formation and number of invasive cells in untreated and control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA infected breast cancer cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. **p<0.01. d, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of XBP1 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells infected with lentiviruses encoding doxycycline (DOX) inducible shRNAs against XBP1 or scrambled LacZ control, in the presence or absence of doxycycline for 48h. Data are presented relative to β-actin and shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. e-f, Knockdown efficiency of total XBP1 (e) and XBP1s (f) in MDA-MB-231 derived xenograft tumor (as in Fig.1d). Data are presented relative to β-actin. n=5. g, Bioluminescent images of orthotopic tumors formed by luciferase expressing MDA-MB-231 cells infected with different lentiviruses. A total of 1.5×106 cells were injected into the fourth mammary glands of nude mice. Bioluminescent images were obtained 1 week later and serially after mice were begun on chow containing doxycycline (Dox) (day 10). Pictures shown are the day 10 images (Before Dox) and day 45 images (After Dox). h, Effect of XBP1 knockdown on ER stress marker BIP expression in MDA-MB-231 derived xenograft tumors. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of BIP expression in shCtrl or shXBP1 xenograft tumor. Data are presented relative to β-actin. n=5. i, Immunoblot of IRE1α activation (phos-tag SDS-PAGE) and PERK phosphorylation in whole cell lysates; ATF6α processing and ATF4 expression in nuclear extracts of two shCtrl or shXBP1 xenograft tumors. HSP90 was used as loading control for whole cell lysates, TBP was used as loading control for nuclear extract. j-k, Tumor growth of untreated or control shRNA, or XBP1 shRNA treated MDA-MB-436 (j) or HBL-100 cells (k) in nude mice. Data are shown as mean ± SD of biological replicates (n=3). **p<0.01. Tx: Treatment with shRNA. l, Kaplan-Meier tumor free survival curve of mice from Fig. 1f. m, Tumor growth (mean ± SEM) of BCM-2147 tumors as in Fig. 1f (Scr siRNA: n=7; XBP1 siRNA: n=2).

Extended Data Figure 2. Effect of XBP1 on tumor relapse and CD44high/CD24low cells.

a, Tumor growth of MDA-MB-231 cells untreated or treated with paclitaxel (20mg/kg), or paclitaxel + control shRNA, or paclitaxel + XBP1 shRNA in nude mice. TX: treatment with paclitaxel or paclitaxel+ shRNA. Data are shown as mean ± SD of biological replicates (n=5). b, Number of mammospheres per 1,000 cells generated from day 20 xenograft tumors under different treatments as indicated under normoxic or hypoxic condition (0.1% O2). Data are shown as mean ± SD of biological replicates (n=3). * denotes significantly different from paclitaxel+shCtrl control in each treatment, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. c, Effect of XBP1 knockdown on cell death in hypoxic regions (assessed by CA9 and cleaved caspase3 staining) or accumulation of CD44high/CD24low cells (assessed by CD44 staining). Immunohistochemical staining of CA9 and Cleaved Caspase 3 (consecutive sections) showed that cell death was not induced in hypoxic region in XBP1 knockdown tumors. Immunohistochemical staining of CD44 showed significant reduction of CD44 expression in XBP1 knockdown tumors. All tumor sections are from MDA-MB-231 derived xenograft with different treatment as indicated. d, Knockdown efficiency of XBP1 in MCF10A-ER-Src cells. Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. e, Left panel: Flow cytometry analysis of CD44 and CD24 expression of TAM treated (36h) MCF10A ER-Src cells infected with control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA encoding lentivirus. Right panel: Percentage of CD44high/CD24low cells in TAM (4-OH-tamoxifen) treated MCF10A-ER-Src cells infected with control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA encoding lentivirus. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. *p<0.05. f, Number of mammospheres per 1,000 cells generated by TAM treated MCF10A ER-Src cells uninfected, or infected with control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA encoding lentivirus. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. g, Cell viability assay (Cell-titer Glo) on CD44high/CD24low or CD44low/CD24high cells isolated from TAM treated MCF10A-ER-Src cells infected with control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA encoding lentivirus (72h after infection). Data were normalized to the control (cell infected with shCtrl). Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. h, Cleaved caspase 3 ELISA assays on CD44high/CD24low or CD44low/CD24high cells isolated from TAM treated MCF10A-ER-Src cells infected with control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA encoding lentivirus (72h after infection). Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD.

Extended Data Figure 3. Effect of XBP1 on CD44high/CD24low cells.

a, UPR markers are upregulated in CD44high/CD24low cells. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of UPR markers BIP, CHOP, ERDJ4, HERP and MBTPS1 in CD44low/CD24high cells and CD44high/CD24low cells sorted from two TNBC patients. Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. b, XBP1s overespression in CD44low/CD24high cells generates mammosphere-forming ability. Number of mammospheres per 1,000 cells generated by sorted CD44low/CD24high cells transduced with empty vector or XBP1s expressing retrovirus. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. c, CD44low/CD24high cells overexpressing XBP1s are more resistant to chemotherapy. MTT assay was performed to measure the dose-response curves of CD44low/CD24high cells or CD44low/CD24high cells expressing XBP1s treated with doxorubicin. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. d, 1000 or 100 CD44low/CD24high cells sorted from transformed MCF10A ER-Src cells or CD44low/CD24high cells overexpressing XBP1s were injected into NOD/SCID/IL2Rγ-/-mice and the incidence of tumors was monitored. e, 10 CD44low/CD24high cells sorted from two human patients with TNBC or CD44low/CD24high cells overexpressing XBP1s were injected into NOD/SCID/IL2Rγ-/-mice and the incidence of tumors was monitored.

Extended Data Figure 4. HIF1α is a co-regulator of XBP1.

a, Identification of XBP1 motif in MDA-MB-231 ChIP-seq dataset. Matrices predicted by the de novo motif-discovery algorithm Seqpos. p<1.08×10-30. b, Induction of XBP1 splicing by hypoxia. RT-PCR analysis of the ratio of XBP1s to total XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 cells cultured under normoxic condition or hypoxic condition (0.1% O2) for 24h. Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. **p<0.01. c, Induction of XBP1 splicing by glucose deprivation. RT-PCR analysis of the ratio of XBP1s to total XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 cells cultured in normal medium or glucose free medium for 24h or 48h. Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. *p<0.05. d, Induction of XBP1 splicing by oxidative stress. RT-PCR analysis of the ratio of XBP1s to total XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 cells untreated or treated with different dose of H2O2 for 1h, 4h or 24h. Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. e, Western blotting analysis of XBP1s expression in nuclear extract of MDA-MB-231 cells cultured under normoxia or hypoxia (0.1% O2) and glucose free condition for 16h. Lamin B was used as loading control. f, Venn diagram showing the overlap between XBP1 targets in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells cultured under normoxic condition (untreated) or hypoxia and glucose deprivation condition (treated). g, Motif enrichment analysis in the XBP1 binding sites in untreated or stressed (0.1% O2 and glucose deprivation: HG) MDA-MB-231, Hs578T or T47D cells. The 1kb region surrounding the summit of the XBP1 peak is equally divided into 50 bins. The average HIF1α motif occurrence over top 1000 XBP1 peaks in each bin is plotted. The corresponding p-values of each condition are listed as follows: M231_UN: 7.78×10-20; M231_HG: <1.08×10-30; Hs578T_HG: <1.08×10-30, T47D_HG: 6.14×10-6. h, FLAG-tagged HIF1α and XBP1s were co-expressed in 293T cells, and the cells were treated in 0.1% O2 for 16h. Co-IP was performed with M2 anti-FLAG antibody. Western blot was carried out with anti-XBP1s antibody, anti-FLAG antibody or anti-HIF1α antibody. Empty vector was used as control. i, Nuclear extracts from Hs578T cells treated with Tunicamycin (1μg/ml, 6h) in 0.1% O2 (16h) were subjected to co-IP with anti-HIF1α antibody or rabbit IgG. Western blot was carried out with anti-XBP1s antibody or anti-HIF1α antibody. j, HA-tagged HIF2α and XBP1s were co-expressed in 293T cells, and the cells were treated in 0.1% O2 for 16h. Co-IP was performed with anti-HA antibody. Western blot was carried out with anti-XBP1s antibody or anti-HA antibody. Empty vector was used as control. k, Localization of XBP1s and HIF1α in MDA-MB-231 cells. Western blotting analysis of XBP1s and HIF1α expression in cytosolic extracts and nuclear extracts of MDA-MB-231 cells cultured under 0.1% O2 condition for 24h. HSP90 and TBP were used as control. l, XBP1u is not expressed in MDA-MB-231 cells. Western blotting analysis of XBP1u in MDA-MB-231 cells untreated or treated with 1μM or 10μM MG132 for 4h. HSP90 was used as loading control. m, Schematic diagram of full-length and truncated forms of XBP1s protein. n, A GST pull down assay was performed using GST-tagged XBP1s proteins and 293T cell lysates overexpressing HA-tagged HIF1α. Western blotting was performed with an anti-HA antibody. Lower panel: Coomassie blue staining of GST-tagged different truncated forms of XBP1s proteins.

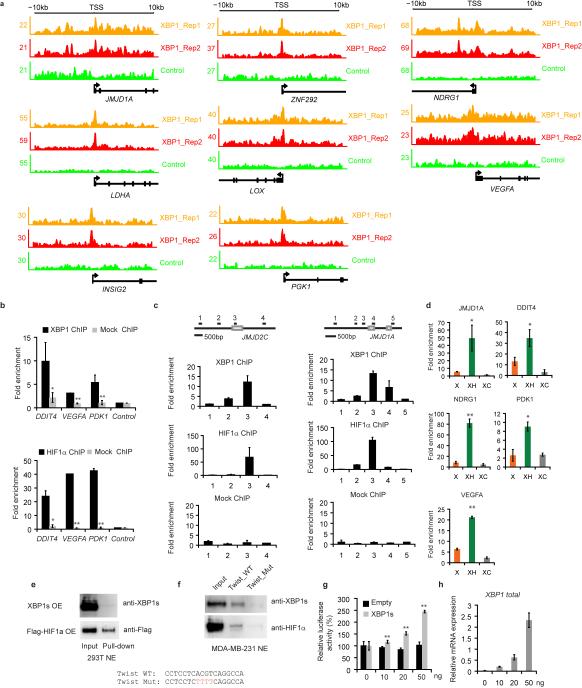

Extended Data Figure 5. XBP1 and HIF1α co-occupy HIF1α targets.

a, Track view of XBP1 ChIP-seq density profile (two biological replicates) on HIF1α target genes. b, XBP1 and HIF1α co-bind to DDIT4, VEGFA, and PDK1 promoters under hypoxic conditions. A ChIP assay was performed using anti-XBP1 or anti-HIF1α antibody to detect enriched fragments. GST antibody was used as mock ChIP control. c, XBP1 and HIF1α co-bind to JMJD1A and JMJD2C promoters under hypoxic conditions. Upper panel: Schematic diagram of the primer locations across the JMJD2C or JMJD1A promoter. Grey boxes indicate exon. A ChIP assay was performed using anti-XBP1 polyclonal antibody or anti-HIF1α polyclonal antibody to detect enriched fragments. Fold enrichment is the relative abundance of DNA fragments at the amplified region over a control amplified region. GST antibody was used as mock ChIP control. d, XBP1s and HIF1α co-occupy JMJD1A, DDIT4, NDRG1, PDK1 and VEGFA promoters. A ChIP-re-ChIP assay was performed using the anti-XBP1s antibody first (X). The eluants were then subjected to a second ChIP assay using an anti-HIF1α antibody (XH) or a control IgG antibody (XC). All ChIP Data (b-d) are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. Results show a representative of two independent experiments. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. e, HIF1α, but not XBP1s, binds to a probe in Twist promoter in 293T cells. DNA pull down assay was used to analyze the binding of XBP1s or HIF1α on a probe in Twist promoter. The nuclear extracts of 293T cells overexpressing XBP1s or Flag-HIF1α was incubated with the wild-type probe and immunoblot analysis was performed with anti-XBP1s or anti-Flag antibody. f, XBP1s binds to Twist promoter in MDA-MB-231 cells under 0.1% O2. The nuclear extract of MDA-MB-231 cells cultured under 0.1% O2 for 24h was incubated with the wild-type or mutant probe (HIF1α consensus sequence was mutated) and immunoblot analysis was performed with anti-XBP1s or anti-HIF1α antibody. The lower panel shows the sequence of the probes used. g, 3xHRE reporter was co-transfected with XBP1s expression plasmid or empty vector into MDA-MB-231 cells and luciferase activity measured. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. **p<0.01. h, RT-PCR analysis of XBP1 expression as in (g). Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates.

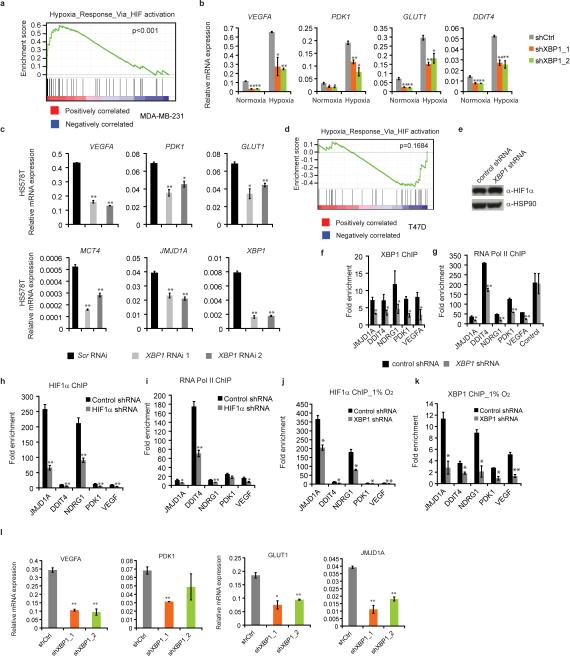

Extended Data Figure 6. XBP1 regulates HIF1α targets.

a, Plot from GSEA showing enrichment of the HIF1α mediated hypoxia response pathway in XBP1-upregulated genes. b, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of VEGFA, PDK1, GLUT1, and DDIT4 expression after knockdown of XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 under both normoxic or hypoxic conditions. c, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of VEGFA, PDK1, GLUT1, MCT4, JMJD1A and XBP1 expression after knockdown of XBP1 in Hs578T cells treated with 0.1% O2 for 24h. Results are presented relative to β-actin expression. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. d, Plot from GSEA showing no enrichment of the HIF1α mediated hypoxia response pathway in XBP1-regulated genes in T47D cells (p=0.1684). e-k, Cooperative binding of XBP1 and HIF1α on common targets. e, Immunoblotting analysis of control MDA-MB-231 cell lysates and XBP1 knockdown lysates (treated with 0.1% O2 for 24h) were performed using anti-HIF1α or anti-HSP90 antibody. f-g, Chromatin extracts from control MDA-MB-231 cells or XBP1 knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells (treated with 0.1% O2 for 24h) were subjected to ChIP using anti-XBP1s antibody (f), or anti-RNA polymerase II antibody (g). The primers used to detect ChIP-enriched DNA were the peak pair of primers in JMJD1A, DDIT4, NDRG1, PDK1 and VEGFA promoters (Supplementary Table 3). Primers in the β-actin region were used as control. h-i, Chromatin extracts from control MDA-MB-231 cells or HIF1α knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells (treated with 0.1% O2 for 24h) were subjected to ChIP using anti-HIF1α antibody (h), or anti-RNA polymerase II antibody (i). j-k, Chromatin extracts from control MDA-MB-231 cells or XBP1 knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells (treated with 1% O2 for 24h) were subjected to ChIP using anti-HIF1α antibody (j), and anti-XBP1s antibody (k). All ChIP Data (f-k) are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. Results show a representative of two independent experiments. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. l, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of VEGFA, PDK1, GLUT1, and JMJD1A after knockdown of XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 1% O2 for 24h. Results are presented relative to β-actin expression. Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

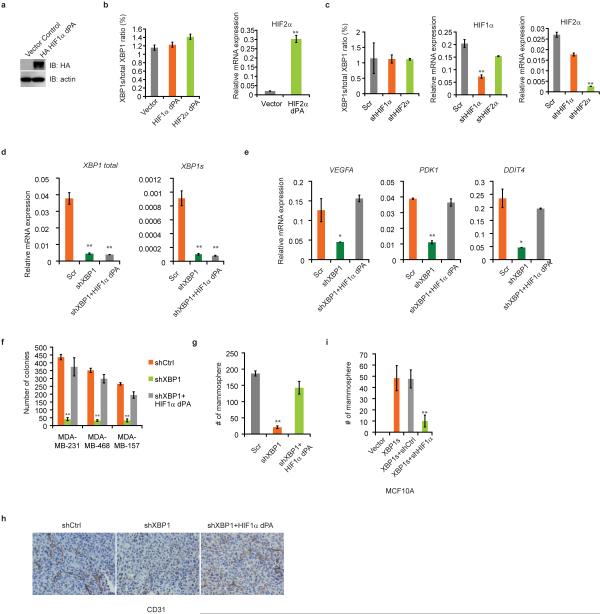

Extended Data Figure 7. Overexpression of constitutively activated HIF1α rescues XBP1 knockdown phenotype.

a, Immunoblotting analysis of cell lysates of MDA-MB-231 cells infected with retrovirus encoding control vector or HA-HIF1α dPA was performed using anti-HA or anti-actin antibody. b, XBP1 splicing is not affected by HIF1α or HIF2α activation. RT-PCR analysis of the ratio of XBP1s to total XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 cells expressing control vector, HA-HIF1α dPA or HA-HIF2α dPA. Expression of HA-HIF1α dPA is shown in (a) and expression of HIF2α is shown in the right panel. c, XBP1 splicing is not affected by HIF1α or HIF2α depletion. RT-PCR analysis of the ratio of XBP1s to total XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 cells infected with control, shHIF1α or shHIF2α lentivirus. Knockdown efficiency of HIF1α or HIF2α is shown in the middle and right panels. d-e, Expression of constitutively activated HIF1α doesn't affect XBP1 expression (d), but restores HIF1α targets expression (e). RT-PCR analysis of XBP1 total (d), XBP1s (d) and VEGFA, PDK1, DDIT4 (e) in control shRNA (shCtrl), XBP1 shRNA (shXBP1), or XBP1 shRNA plus constitutively activated HIF1α (shXBP1+HIF1α dPA) infected MDA-MB-231 cells. Data (b-e) are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. f, Quantification of soft agar colony formation in control shRNA (shCtrl), XBP1 shRNA (shXBP1), or XBP1 shRNA plus constitutively activated HIF1α (shXBP1+HIF1α dPA) infected MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, or MDA-MB-157 cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. **p<0.01. g, Quantification of mammosphere formation in control shRNA (shCtrl), XBP1 shRNA (shXBP1), or XBP1 shRNA plus constitutively activated HIF1α (shXBP1+HIF1α dPA) infected MDA-MB-231 cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. **p<0.01. h, CD31 immunostaining of tumors formed by MDA-MB-231 cells infected with control shRNA (shCtrl), XBP1 shRNA (shXBP1) or XBP1 shRNA plus constitutively activated HIF1α (shXBP1+HIF1αdPA). i, Silencing of HIF1α inhibits the XBP1s-sustained mammosphere forming ability. Quantification of mammosphere formation in MCF10A cells expressing control vector, XBP1s, XBP1s plus control shRNA or XBP1s plus HIF1α shRNA. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. **p<0.01.

Extended Data Figure 8. Schema depicting the interaction of XBP1 and HIF1α in TNBC.

XBP1 and HIF1α cooperatively regulate HIF1α targets in TNBC. In the setting of a tumor microenvironment, hypoxia further induces XBP1 activation, active XBP1s in turn interacts with HIF1α to stimulate and augment the transactivation of HIF1 target genes that promote cancer progression.

Extended Data Figure 9. Correlation of XBP1 with HIF1α in patients with TNBC.

a-b, Expression of XBP1 signature is highly correlated with two public available hypoxia-driven signatures in TNBC patients (a), but not in ER+ breast cancer patients (b). The scatter-plot of XBP1 and two publicly available HIF1α signature (Left panel: HIF1α pathway; Right panel: Hypoxia via HIF1α pathway) across different tumors were drawn for TNBC (a) and ER+ breast cancer patients (b), respectively. The corresponding Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) between XBP1 and HIF1α signature was shown. c-d, Kaplan-Meier graphs demonstrating no significant association of the expression of the XBP1 signature (red line) (c) or HIF signature (d) with relapse free survival in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer patients. The log-rank test P values are shown.

Extended Data Figure 10. Role of XBP1 in luminal breast cancer.

a, XBP1 splicing is induced by hypoxia and glucose deprivation in luminal cancer cells. RT-PCR of XBP1 splicing in T47D and SKBR3 cells under different treatments for 24h. XBP1u: unspliced XBP1, XBP1s: spliced XBP1. Hypoxia: 0.1% O2. b. Left panel: Quantification of soft agar colony formation in untreated and control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA infected breast cancer cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. **p<0.01. Right panel: effect of XBP1 depletion on soft agar colony formation in luminal vs basal cell lines. Percentages of soft agar colonies formed from cells infected with XBP1 shRNA lentivirus relative to the same cell line infected with shCtrl lentivirus (set as 100%) are presented. 5 cell lines in each group (as in left panel) and data are shown as mean ± SD. c, Tumor growth (mean ± SD) of ZR-75-1 cells treated with control shRNA (n=4), paclitaxel (20mg/kg) + control shRNA (n=4), XBP1 shRNA (n=4) or paclitaxel + XBP1 shRNA (n=3) in nude mice. TX: treatment with shRNA or paclitaxel+ shRNA. *denotes shXBP1 treated tumors significantly different from shCtrl treated tumors. p<0.05. d, Number of mammospheres per 1,000 cells generated by control shRNA or XBP1 shRNA encoding lentivirus infected T47D or SKBR3 breast cancer cell lines cultured under normoxia or hypoxia and glucose deprivation conditions (treated). Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are shown as mean ± SD. e. Venn diagram showing the overlap between XBP1 targets in MDA-MB-231, Hs578T cells and T47D cells cultured under hypoxia and glucose deprivation conditions. f. XBP1s overexpression is not capable of converting a luminal phenotype to basal phenotype. RT-PCR analysis of luminal markers (CK8, CK18, CK19 and E-cadherin) and basal markers (CK5, CK14, p63, Fibronectin and Vimentin) expression in luminal breast cancer cells (MCF7 or T47D) infected with lentivirus encoding empty vector or XBP1s. Data are shown as mean ± SD of technical triplicates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. William G. Kaelin, Jr., Ann-Hwee Lee, Fabio Martinon, Marc N. Wein, and Xin Li for critical review of the manuscript. We are grateful to Drs. Andrea L. Richardson, Han Xu and Juexuan Wang for helpful advice and discussions. We thank Lacey A Paskett, Xuewu Liu, Rob Kim and Yifang Liu for technical support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA112663 and AI32412 to L.H.G.), and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (to X.C.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

X.C. and L.H.G. designed the research; X.C., D.I., Q.Z., M.B.G., M.H., E.L., D.Z.H., B.H., C.T. and M.S. did the experiments; Q.T. and Y.C. performed the bioinformatics analysis; X.S.L. supervised the bioinformatics analysis; M.N., W.L.T., M.B., S.J.S. contributed to discussions and critical reagents; J.C.C., M.F., M.D.L., H.S., and J.M. contributed to the patient-derived xenograft experiments; X.C. and L.H.G wrote the paper.

ChIP-seq and gene expression microarray data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE49955. L.H.G. holds equity in and is on the corporate board of directors of Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrasco DR, et al. The differentiation and stress response factor XBP-1 drives multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:349–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Raedt T, et al. Exploiting cancer cell vulnerabilities to develop a combination therapy for ras-driven tumors. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:400–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahoney DJ, et al. Virus-tumor interactome screen reveals ER stress response can reprogram resistant cancers for oncolytic virus-triggered caspase-2 cell death. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:443–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey L, Winer E, Viale G, Cameron D, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: disease entity or title of convenience? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:683–92. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montagner M, et al. SHARP1 suppresses breast cancer metastasis by promoting degradation of hypoxia-inducible factors. Nature. 2012;487:380–4. doi: 10.1038/nature11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Network TCGA. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Idowu MO, et al. CD44(+)/CD24(−/low) cancer stem/progenitor cells are more abundant in triple-negative invasive breast carcinoma phenotype and are associated with poor outcome. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:364–73. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin Y, Zhong Y, Guan H, Zhang X, Sun Q. CD44+/CD24− phenotype contributes to malignant relapse following surgical resection and chemotherapy in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:59. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creighton CJ, et al. Residual breast cancers after conventional therapy display mesenchymal as well as tumor-initiating features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13820–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905718106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell. 2009;139:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Wang G, Struhl K. Inducible formation of breast cancer stem cells and their dynamic equilibrium with non-stem cancer cells via IL6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1397–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwab LP, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha promotes primary tumor growth and tumor-initiating cell activity in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R6. doi: 10.1186/bcr3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conley SJ, et al. Antiangiogenic agents increase breast cancer stem cells via the generation of tumor hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2784–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018866109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang MH, et al. Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF-1alpha promotes metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:295–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wouters BG, Koritzinsky M. Hypoxia signalling through mTOR and the unfolded protein response in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:851–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiotto MT, et al. Imaging the unfolded protein response in primary tumors reveals microenvironments with metabolic variations that predict tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2011;70:78–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rody A, et al. A clinically relevant gene signature in triple negative and basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R97. doi: 10.1186/bcr3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnard GA. A New Test for 2×2 Tables. Nature. 1945;156:177. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnard GA. Significance Tests for 2×2 Tables. Biometrika. 1947;34:123–138. doi: 10.1093/biomet/34.1-2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neve RM, et al. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen X, et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:1106–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Brown JB, Huang H, Bickel PJ. Measuring reproducibility of high-throughput experiments. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2011;5:1752–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shipitsin M, et al. Molecular definition of breast tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:259–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Q, et al. A comprehensive view of nuclear receptor cancer cistromes. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6940–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marotta LL, et al. The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway is required for growth of CD44(+)CD24(−) stem cell-like breast cancer cells in human tumors. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2723–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI44745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.