Abstract

The synthesis of polymer therapeutics capable of controlled loading and synchronized release of multiple therapeutic agents remains a formidable challenge in drug delivery and synthetic polymer chemistry. Herein, we report the synthesis of polymer nanoparticles (NPs) that carry precise molar ratios of doxorubicin, camptothecin, and cisplatin. To our knowledge, this work provides the first example of orthogonally triggered release of three drugs from single NPs. The highly convergent synthetic approach opens the door to new NP-based combination therapies for cancer.

Nanoparticle (NP)-based combination cancer therapy has the potential to overcome the toxicity and poorly controlled dosing of traditional systemic combination therapies.1−3 Though NP-based therapeutics for cancer therapy have been the subject of numerous investigations over the past several decades,4−8 ratiometric delivery and synchronized release of multiple drugs from single NP scaffolds remain formidable challenges.9−12 Many of the most studied NP architectures for delivery—e.g., liposomes, micelles, and dendrimers—are not readily amenable to incorporation and release of multiple drugs.

Due to the complex interactions between drugs in living systems, a NP platform for precise tuning and rapid variation of drug loading ratios and release kinetics would enable the discovery of optimal formulations for specific cancer types. We view this challenge as a synthetic problem: multi-drug-loaded NP synthesis would be most efficient if serial particle conjugation and encapsulation reactions were replaced with highly convergent approaches wherein the key elements of a desired NP (e.g., drug molecules) are used to build particles directly.13−17 Herein we present a novel strategy that uses carefully designed drug conjugates as building blocks for the parallel construction of a series of multi-drug-loaded NPs; no extraneous formulation steps are required.

Our NPs carry precise ratios of camptothecin (CPT), doxorubicin (DOX), and/or cisplatin (Pt). These drugs were chosen due to their non-overlapping toxicity profiles.18,19 The most serious dose-limiting side effects from doxorubicin arise from cardiotoxicity,20 while those from cisplatin and camptothecin result from neurotoxicity21 and myelosuppression or hemorrhagic cystitis,22 respectively. Thus, maximum therapeutic index could be achieved, in principle, via simultaneous dosing of each drug at or near its maximum tolerated dose (MTD). We show that three-drug-loaded NPs with ratios matched to multiples of the MTD of each drug outperform analogous one- and two-drug-loaded NPs in in vitro cell viability studies using ovarian cancer (OVCAR3) cells.

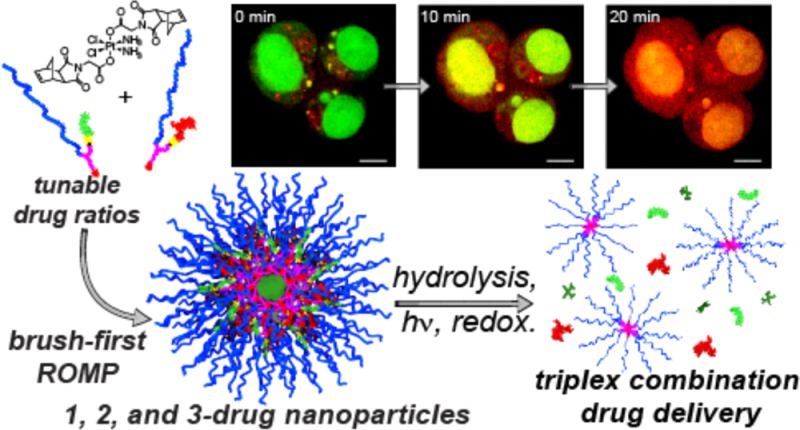

Our synthesis relies on the “brush-first” ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) method,23,24 which enables the preparation of nanoscopic brush-arm star polymers (BASPs). For the purposes of this study, we designed two novel macromonomers (MMs) and a novel cross-linker (Figure 1A). CPT-MM and DOX-MM are branched MMs25 that release unmodified CPT and DOX in response to cell culture media26 and long-wavelength ultraviolet (UV) light,27 respectively. Both MMs feature a 3 kDa poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) chain that confers water solubility and neutral surface charge to the final NP.28,29

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of monomers used in this study. (B) Schematic for synthesis of three-drug-loaded BASP. Drug release occurs in response to three distinct triggers.

For our cross-linker design, we were drawn to Pt(IV) diester derivatives, which are widely applied as prodrugs for the clinically approved chemotherapeutic cisplatin.30−34 Pt(IV) diesters release cytotoxic Pt(II) species upon glutathione-induced intracellular reduction. We wondered whether a Pt(IV) bis-norbornene complex could serve as a cross-linker during brush-first ROMP. If so, then the resulting BASP core would be connected via labile Pt–O bonds; reduction would lead to particle degradation to yield ∼5 nm brush polymers27 and free cisplatin. To explore the feasibility of this approach, we designed and synthesized Pt-XL (Figure 1A, see SI for details).

With this pool of novel monomers in hand, we targeted BASPs with molar ratios of each drug that correspond to 2 times the MTD of CPT,35 2 times the MTD of DOX,36 and 1 times the MTD of cisplatin.37 In the brush-first method, the final BASP size is determined by the MM to cross-linker ratio.23 A series of stoichiometry screens using a non-drug-loaded MM (PEG-MM, Figure 1A) and Pt-XL revealed that the most uniform BASPs formed when the total MM:Pt-XL ratio was 7:3. Thus, this ratio was held constant for all drug-loaded particles; PEG-MM was simply replaced with DOX-MM and/or CPT-MM. For example, a three-drug-loaded particle (3) was prepared as follows: CPT-MM (2.07 equiv), DOX-MM (0.83 equiv), and PEG-MM (4.09 equiv) were exposed to Grubbs third-generation catalyst (cat., 1.00 equiv) for 20 min. Pt-XL (3.00 equiv) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 6 h at room temperature. Analogous one- and two-drug-loaded particles (1, 2a, and 2b) were prepared in parallel following similar procedures. In this system, the mass fraction of drug increases with introduction of new drug (3.4% for 1, 6.1% for 2a, 5.1% for 2b, and 7.8% for 3).

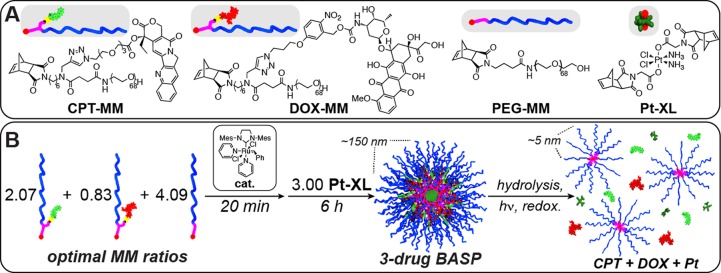

Upon completion of the brush-first ROMP reactions, the crude reaction mixtures were analyzed by gel permeation chromatography (Figure S1). In all cases, the conversion of MM and brush to BASP was >90%. A combination of UV/vis, 1H NMR, and inductively coupled mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was used to confirm the drug ratios in 3 (Table S1). Dynamic light scattering (DLS, Figure 2B) revealed hydrodynamic diameters (DH) from 122 to 191 nm for this series (Figure 2A). These values are larger than we observed for our previous photocleavable BASPs.23 Regardless, the observed DH values are suitable for passive tumor targeting via the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect:38 they are larger than the ca. 6–8 nm renal clearance threshold39 and smaller than the 200–250 nm splenic clearance cutoff.40 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of positively (Figure 2C, top) and negatively (Figure 2C, bottom) stained BASPs showed uniform NPs (Figure S2). CryoTEM images of the BASPs in aqueous solution (Figure S3) showed particle diameters that agree well with DLS data.

Figure 2.

(A) Table of BASP NPs prepared in this study along with the MM stoichiometry used to prepare each particle. BASP diameters as measured by transmission electron microscopy (DTEM) and dynamic light scattering (DH). aTEM data were obtained from dilute aqueous solutions cast onto a TEM grid, dried, and imaged without staining. bDH values were measured using 0.1 mg BASP/mL 5% glucose solutions. DLS correlation functions were fit using the CONTIN algorithm. Values in parentheses correspond to the standard deviation for three particle measurements. (B) DLS histograms for drug-loaded BASPs. (C) Positively (top) and negatively (bottom) stained TEM images of 3. Scale bars correspond to 100 nm.

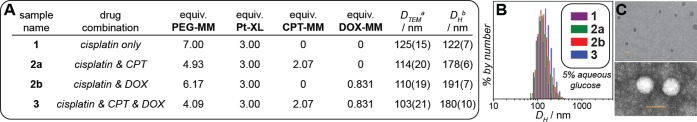

We next studied the cytotoxicity of these BASPs using OVCAR3 human ovarian cancer cells (Figure 3A). OCVAR3 is an established model cell line derived from a patient with platinum-refractory41 disease that exhibits genotypic similarity with the high-grade serous subtype.42 Given the widespread clinical use of anthracyclines and topoisomerase I inhibitors in second-line therapies for recurrent ovarian carcinoma, OVCAR3 is a suitable model for BASP combination chemotherapy.43,44 Exposure of OVCAR3 cells to 365 nm UV light for 10 min (black circles) induced no observable toxicity. A non-drug-loaded BASP23 displayed toxicity only at very high concentrations (>650 μg/mL) in the presence and absence of UV light (Figure S4). Among the drug-loaded BASPs, 1 (purple curve) had the largest IC50 value: 192 ± 46 μg BASP/mL (23 ± 5 μM drug).

Figure 3.

(A) OVCAR3 cell viability data after 72 h of treatment with 5% glucose (0) and BASPs 1, 2a, 2b, and 3. Data labeled “+hν” were obtained from cells treated with BASP, irradiated with 365 nm light for 10 min, and then incubated for a total of 72 h. Solid and dashed lines represent sigmoidal fits for dark and irradiated samples, respectively. (B) Bar chart of IC50 values along with statistical comparisons. Error represents standard error of the mean of four technical replicates.

BASP 2a (green curve) showed a much lower IC50: 44 ± 15 μg BASP/mL (8 ± 2 μM drug). BASP 2b had an IC50 of 217 ± 23 μg BASP/mL (32 ± 3 μM drug) in the absence of irradiation (red trace), which is not significantly different from that of 1; exposure to UV for 20 min led to a 2.3 ± 0.3-fold decrease in IC50 to 93 ± 11 μg BASP/mL (14 ± 1 μM drug). No significant decrease in viability was observed following photoexposure of 1 and 2a (P = 0.078 and 0.018, respectively). These results suggest that therapeutically active cisplatin and CPT are released from these BASPs without an external trigger; DOX release is only significant upon irradiation.

When cells were treated with three-drug-loaded BASP 3 without UV irradiation (blue curve), the IC50 was 42 ± 6 μg BASP/mL (9.2 ± 0.8 μM drug). This result can be rationalized via extrapolation of the results for 1, 2a, and 2b: in the absence of light, 3 only released CPT and cisplatin, i.e., it behaved similarly to 2a (P = 0.81). After UV irradiation for 10 min, the IC50 for 3 dropped 2.3 ± 0.4-fold to 18 ± 2 μg BASP/mL (4.0 ± 0.3 μM total drug); the three-drug-loaded NP outperformed the one- and two-drug-loaded systems.

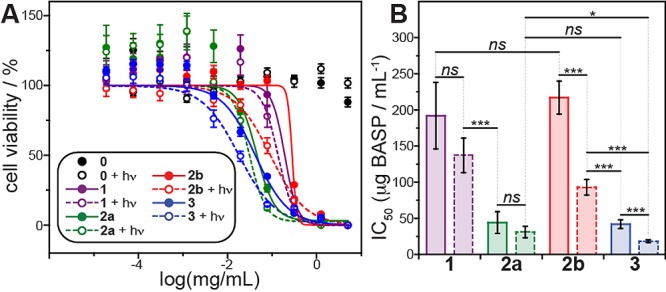

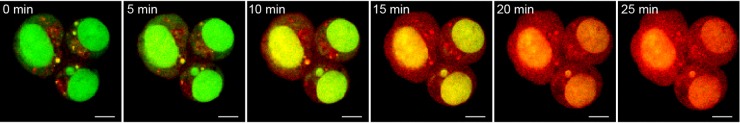

To examine cellular internalization of BASPs, we conducted a series of confocal fluorescence imaging experiments on live cells using the inherent fluorescence of DOX. After 30 min of incubation with 2b in the dark, cells were briefly irradiated with 405 nm laser light once per minute and imaged immediately afterward for 25 min (DOX λex/λem = 561/595 nm). Figure 4 shows images collected at various times (see Figure S5 for full series). Initially, punctate, extranuclear DOX fluorescence was observed to colocalize with acridine orange in the endo/lysosomes (Figure 4, far left); photoinduced DOX release led to rapid redistribution of fluorescence throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus and a 2.7-fold fluorescence intensity increase (Figure S6). To ensure that these results were due to DOX release, an experiment was conducted wherein cells were pulsed with 561 nm light rather than 405 nm. In this case, the particles remained in the endosomes (Figure S7), and no increase in mean fluorescence intensity was observed.

Figure 4.

Phototriggered release of DOX in OVCAR3 cells as monitored by live-cell confocal fluorescence imaging. Cells were loaded with 2b for 30 min and concurrently exposed to 405 nm UV irradiation during imaging of doxorubicin (red; λex/λem = 561/595 nm) and nuclei (acridine orange, green; λex/λem = 488/525 nm). Scale bar is 5 μm.

To our knowledge, this work represents the first example of triplex drug delivery tuned precisely to specific ratios of each drug. This novel concept for combination delivery is only made possible using highly convergent NP synthesis. This approach has no fundamental limitation in terms of the number and ratio of molecular species that could be built into particles, as long as the molecules of interest possess addressable functional groups that are compatible with ROMP. Through the combination of alternative MMs, drug linkers, and cross-linkers, libraries of multi-drug-loaded BASPs can be readily synthesized in parallel for efficacy optimization. These studies along with in vivo analysis of the current BASP systems are currently ongoing in our laboratories.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the MIT Research Support Committee, the MIT Lincoln Laboratories Advanced Concepts Committee, the Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program Teal Innovator Award, the National Institutes of Health (E.C.D., Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA 1F32EB017614-01), the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council (postdoctoral fellowship for K.E.S. and graduate fellowship for J.L.), and the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute. We thank the Koch Institute Swanson Biotechnology Center for technical support.

Supporting Information Available

Supplemental figures, experimental procedures, and spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Hu C. M. J.; Zhang L. F. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Bjornmalm M.; Caruso F. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Kohli M.; Smith A. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2003, 2, 347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer D.; Karp J. M.; Hong S.; Farokhzad O. C.; Margalit R.; Langer R. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky J. B.; Grinstaff M. W. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2008, 60, 1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. E.; Chen Z.; Shin D. M. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon G. S.; Kataoka K. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2012, 64, 237. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S.; Eavarone D.; Capila I.; Zhao G. L.; Watson N.; Kiziltepe T.; Sasisekharan R. Nature 2005, 436, 568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers T.; Subr V.; Ulbrich K.; Peschke P.; Huber P. E.; Hennink W. E.; Storm G. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolishetti N.; Dhar S.; Valencia P. M.; Lin L. Q.; Karnik R.; Lippard S. J.; Langer R.; Farokhzad O. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 17939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryal S.; Hu C. M. J.; Zhang L. F. Mol. Pharm. 2011, 8, 1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Rocca J.; Huxford R. C.; Comstock-Duggan E.; Lin W. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond P. T. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. F.; Yin Q.; Yin L. C.; Ma L.; Tang L.; Cheng J. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z. J.; Morton S. W.; Ben-Akiva E.; Dreaden E. C.; Shopsowitz K. E.; Hammond P. T. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua S.; Mitragotri S. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devita V. T.; Serpick A. A.; Carbone P. P. Ann. Int. Med. 1970, 73, 881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Lazikani B.; Banerji U.; Workman P. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singal P. K.; Iliskovic N. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollman J. E. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzolato J. F.; Saltz L. B. Lancet 2003, 361, 2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Burts A. O.; Li Y.; Zhukhovitskiy A. V.; Ottaviani M. F.; Turro N. J.; Johnson J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Gao A. X.; Johnson J. A. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, e50874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burts A. O.; Li Y. J.; Zhukhovitskiy A. V.; Patel P. R.; Grubbs R. H.; Ottaviani M. F.; Turro N. J.; Johnson J. A. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 8310. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; McRae S.; Parelkar S.; Emrick T. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009, 20, 2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. A.; Lu Y. Y.; Burts A. O.; Xia Y.; Durrell A. C.; Tirrell D. A.; Grubbs R. H. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 10326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald R. B.; Choe Y. H.; McGuire J.; Conover C. D. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2003, 55, 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvizo R. R.; Miranda O. R.; Moyano D. F.; Walden C. A.; Giri K.; Bhattacharya R.; Robertson J. D.; Rotello V. M.; Reid J. M.; Mukherjee P. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. D.; Hambley T. W. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 232, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama N.; Okazaki S.; Cabral H.; Miyamoto M.; Kato Y.; Sugiyama Y.; Nishio K.; Matsumura Y.; Kataoka K. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 8977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar S.; Gu F. X.; Langer R.; Farokhzad O. C.; Lippard S. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 17356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar S.; Daniel W. L.; Giljohann D. A.; Mirkin C. A.; Lippard S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer R.; Wilson R. H.; Calvert H.; Boddy A. V.; Griffin M.; Sludden J.; Tilby M. J.; Eatock M.; Pearson D. G.; Ottley C. J.; Matsumura Y.; Kataoka K.; Nishiya T. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiolfa V. R.; Zamai M.; Fiorino A.; Frigerio E.; Pellizzoni C.; d’Argy R.; Ghiglieri A.; Castelli M. G.; Farao M.; Pesenti E.; Gigli M.; Angelucci F.; Suarato A. J. Controlled Release 2000, 65, 105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay J. A.; Chen M. N.; McDaniel J. R.; Liu W. G.; Simnick A. J.; Chilkoti A. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. L.; Hsu Y. T.; Wu C. C.; Lai Y. Z.; Wang C. N.; Yang Y. C.; Wu T. C.; Hung C. F. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y.; Maeda H. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 6387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros R. A.; DeSimone J. M. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghimi S. M.; Hunter A. C.; Murray J. C. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001, 53, 283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin A. K.; Meister A.; Odwyer P. J.; Huang C. S.; Hamilton T. C.; Anderson M. E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domcke S.; Sinha R.; Levine D. A.; Sander C.; Schultz N. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huinink W. T. B.; Gore M.; Carmichael J.; Gordon A.; Malfetano J.; Hudson I.; Broom C.; Scarabelli C.; Davidson N.; Spanczynski M.; Bolis G.; Malmstrom H.; Coleman R.; Fields S. C.; Heron J. F. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap T. A.; Carden C. P.; Kaye S. B. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.