Abstract

Mice display robust, stereotyped behaviors toward pups: virgin males typically attack pups, while virgin females and sexually experienced males and females display parental care. We show here that virgin males genetically impaired in vomeronasal sensing do not attack pups and are parental. Further, we uncover a subset of galanin-expressing neurons in the medial preoptic area (MPOA) that are specifically activated during male and female parenting, and a different subpopulation activated during mating. Genetic ablation of MPOA galanin neurons results in dramatic impairment of parental responses in males and females and affects male mating. Optogenetic activation of these neurons in virgin males suppresses inter-male and pup-directed aggression and induces pup grooming. Thus, MPOA galanin neurons emerge as an essential regulatory node of male and female parenting behavior and other social responses. These results provide an entry point to a circuit-level dissection of parental behavior and its modulation by social experience.

Understanding how neural circuits drive social behavior is a fundamental question in neuroscience. Parental interactions aimed at the care and protection of young are essential for the survival of offspring in many animal species. Elaborate parental behavior is a defining feature of mammals, likely regulated by evolutionarily conserved neural circuits1. Intriguingly, the respective roles of the two parents in offspring care differ across highly related species: while mothers usually assume the largest share of parenting, the contribution of fathers varies dramatically between species, ranging from dedicated parenting of pups to neglect and aggression2,3. The identification of neuronal circuits controlling the display of parental behavior in males and females should help elucidate neural mechanisms underlying this essential social behavior and provide novel insights into the regulation of sexually dimorphic brain functions.

Insights into the neurobiology of parental behavior come primarily from studies in rodents1. Virgin rats find foreign pups aversive but exhibit parental care after continuous exposure to the pups4, or after priming with hormones characteristic of parturient females5,6. In laboratory mice, virgin males and females exhibit dramatically different behaviors toward pups. Virgin males typically attack pups7,8, while virgin females exhibit spontaneous, stereotyped displays of maternal care2,7. Remarkably, males stop attacking pups and transiently become paternal after mating, starting near the time of birth of the pups and lasting until weaning9–11. In female rats, the MPOA and the dopaminergic system have been implicated in the control of maternal behavior12,13. However, the neural mechanisms underlying distinct parental behaviors in females and males with different social experience remain unknown.

Vomeronasal control of pup-directed aggression

The vomeronasal system plays an essential role in regulating sex-specific behaviors14. Males with impaired vomeronasal organ (VNO) signaling mount males and females, suggesting impaired gender identification15. Further, VNO-deficient females show striking male-like mounting and courtship displays, suggesting that the vomeronasal pathway constitutively represses male-specific behavior circuits in females16. We hypothesized that, in males, the vomeronasal pathway may similarly regulate female-typical behaviors such as parenting. This idea is supported by evidence that vomeronasal areas are activated during pup-directed aggression and that disrupted VNO signaling in males reduces aggression and facilitates parenting17–19.

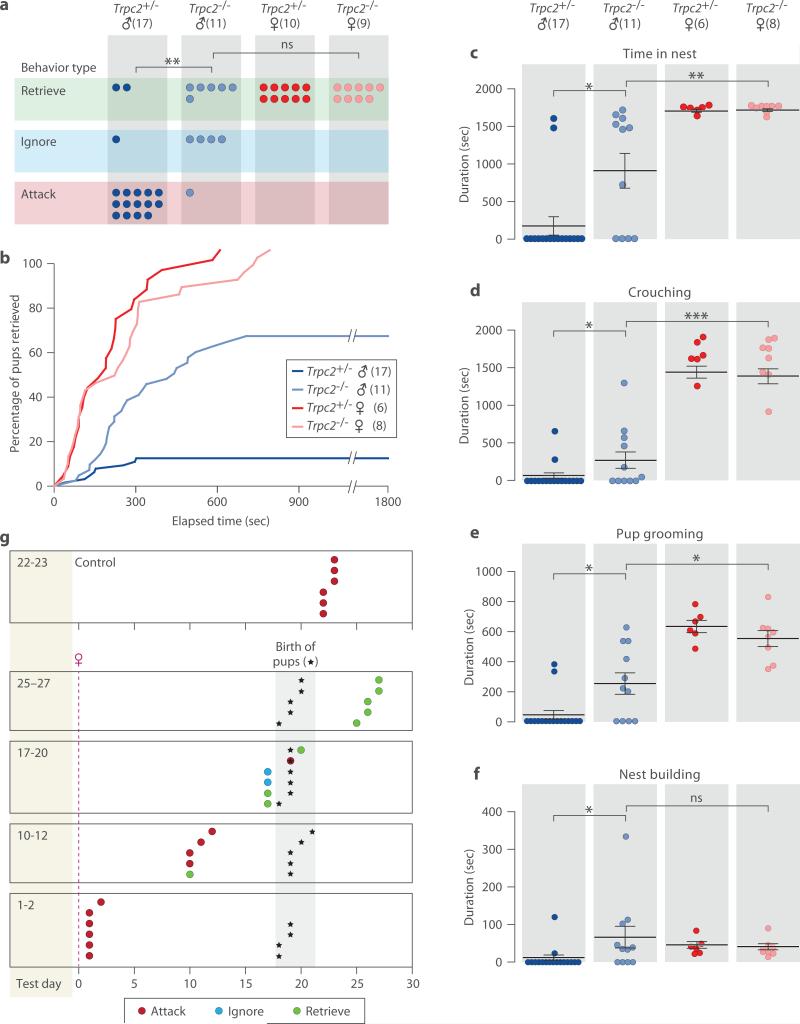

We used genetic tools to confirm the role of VNO inputs in pup-directed behaviors. Genetic ablation of TRPC2, a VNO-specific ion channel, impairs vomeronasal signaling15,20. Adult Trpc2−/− virgin males and females and Trpc2+/− littermates were presented with C57BL/6J pups and behavioral responses were observed. In contrast to Trpc2+/− littermates, Trpc2−/− virgin males showed dramatic reductions in pup-directed aggression (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, a large fraction of Trpc2−/− virgin males exhibited parental care typical of females and fathers (Fig. 1a). Quantification of behavior toward pups showed that Trpc2−/− males retrieved pups with shorter latency, engaged in more nest-building, and were in the nest crouching over and grooming pups longer than Trpc2+/− males. Trpc2−/− males, while clearly parental, displayed less parenting than Trpc2−/− females (Figs. 1b-1f).

Figure 1. Pup-directed behavior of Trpc2−/− and Trpc2+/− virgin animals and switch from attack to parenting in males after mating.

a, Behavior analysis of Trpc2−/− and Trpc2+/− virgin males demonstrates significantly different responses to pups in the presence or absence of VNO signaling. Chi-square test with Bonferroni correction, **P<0.01. b, Combined percentage of pups (out of four) retrieved by an animal group as a function of time. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Bonferroni correction, P<0.001 between Trpc2−/− and Trpc2+/− males, P<0.01 between Trpc2−/− males and Trpc2−/− females. c-f, Time spent in nest, and duration of crouching, pup grooming and nest building. Mean±SEM; Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns. not significant. g, Behavior of Trpc2+/− males tested after increasing durations of cohabitation with females subsequent to mating. Males mated on Day 0 except virgin controls, which were individually housed from Day 0 throughout the test. Male behavior switches from attack to parenting at a time period after mating that corresponds to the birth of their pups.

We next investigated the post-mating switch from attacking pups to paternal behavior originally reported in the CF1 mouse strain11. Virgin control and mated males tested 1-2 days, or 10-12 days after mating attacked pups. However, mated males tested just before pups were born at Day 17-20 did not attack pups, with half displaying paternal behavior. All males tested at Day 25-27 were paternal, consistent with previous studies11,18,21 (Fig. 1g).

Thus, opposing behavior circuits appear to co-exist in the male brain to regulate pup-directed aggression and parenting behaviors according to social context. In virgin males, vomeronasal circuits activated by pup cues elicit pup-directed aggression while pathways underlying parenting behavior remain silent. By contrast, mated males repress VNO-evoked aggression and instead activate parenting circuits.

Neuronal activation during parenting

To identify brain regions involved in parental care, we compared the brain activity patterns of virgin males versus virgin females and paternal males using induction of the immediate early gene c-fos as a read-out of neuronal activation after exposure to pups. We focused our analysis on the hypothalamus, amygdala, and other regions involved in social behaviors (Methods).

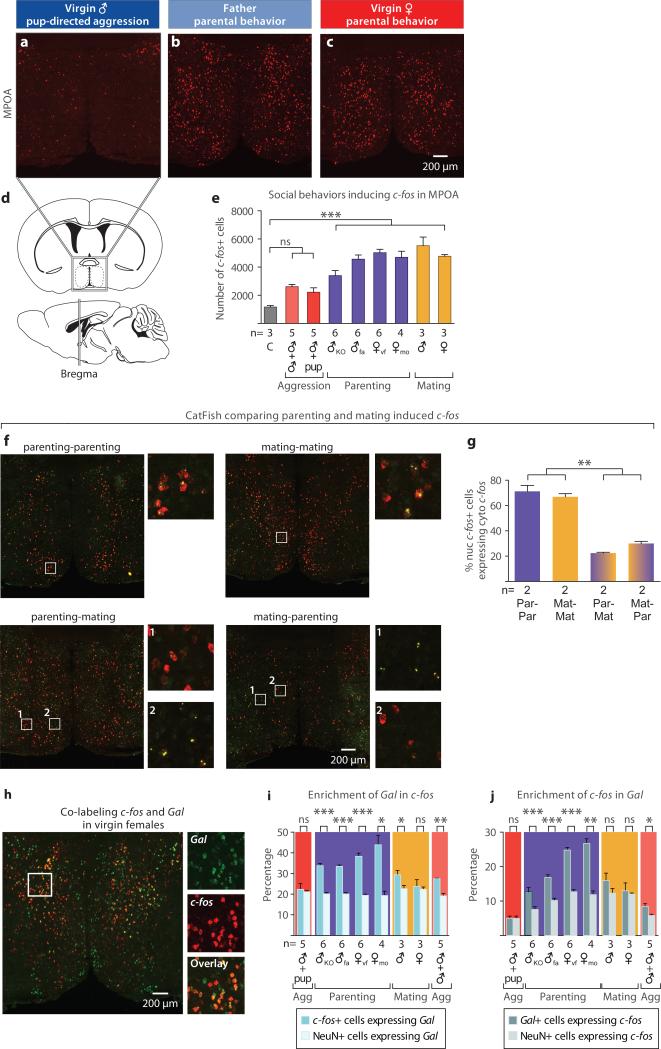

Fathers and virgin females robustly activated similar brain areas after parental care, namely the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPe; data not shown) and the MPOA, and these regions remained consistently silent in virgin males. Specifically, we observed striking increases in the number of MPOA c-fos+ cells of maternal virgin females, Trpc2−/− virgin males and paternal fathers (Figs. 2a-2e), suggesting that a common pathway for parental behavior exists in males and females that is normally repressed in virgin males by vomeronasal inputs. The ventral BNST/dorsal MPOA was shown to play an important role in rat maternal behavior12,22, but also in sexual behavior23–27, thermoregulation28, and GnRH secretion29. Accordingly, we observe robust MPOA c-fos activation after mating, medial to the area containing parenting-induced c-fos (Figs. 2e, 2f).

Figure 2. Parenting activates galanin-expressing neurons in the MPOA.

a-c, c-fos mRNA expression in the MPOA of virgin males, fathers and virgin females after interaction with pups. d, Schematic illustration of the MPOA in sagittal and coronal sections, adapted from the Paxinos and Franklin mouse brain atlas. e, Social behaviors induce c-fos activation in the MPOA in virgin and mated males and females. Groups are labeled as follows: C: fresh bedding exposure; KO: Trpc2−/−; fa: father; vf: virgin female; mo: mother. Mean+SEM, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post test comparing all the social interaction groups to fresh bedding control, ***P<0.001. ns, not significant. f, g catFISH identifying parenting and mating induced c-fos in the MPOA in males show that the two behaviors activate largely distinct MPOA neuronal populations. Par: Parenting; Mat: Mating; nuc: nuclear (yellow); cyto: cytoplasmic (red). Mean+SEM, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post test comparing all pairs of groups, **P<0.01. h, Co-labeling c-fos and Gal in the MPOA of virgin females after interaction with pups. i, j, Percentage of c-fos+ cells expressing Gal and percentage of Gal+ cells expressing c-fos in males and females after various social interactions, compared to the percentages of NeuN+ cells expressing Gal and c-fos, respectively. Agg: Aggression. Mean+SEM, t-test pairing the measurements from each animal, adjusted by Benjamini– Hochberg procedure controlling the false discovery rate. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant.

To determine whether parenting and mating activate different MPOA neurons, we performed a cellular compartment analysis of temporal activity by fluorescent in situ hybridization (catFISH)30, allowing direct comparison of two activated cell populations. Animals experiencing the same behavior twice showed ~70% overlap of nuclear and cytoplasmic c-fos MPOA signals, while animals engaged in different behaviors showed only 20-30% overlap, indicating that mating and parenting activate largely distinct MPOA neuronal populations (Figs. 2f, 2g).

The MPOA is a highly heterogeneous structure31, which receives inputs from, and sends information to, multiple brain regions32,33. The identity of cell populations governing parental behavior is unknown. We characterized active cells in parental behavior using double fluorescent in situ hybridization with c-fos and a series of molecular markers with distinct MPOA expression34 (Methods). We uncovered the neuropeptide galanin (Gal) as a candidate marker for MPOA c-fos+ cells in virgin females, mothers, and fathers. Across all markers surveyed, Gal showed the highest enrichment in parenting-induced c-fos+ MPOA cells (Extended Data Figs. 1a, 1b). 38.3%±1.6% of MPOA c-fos+ cells in virgin females, 43.9%±4.6% in mothers, and 33.4%±0.8% in fathers co-express Gal (Mean±SEM, t-test pairing each animal, P<0.001 for virgin females and fathers, P<0.05 for mothers; Figs. 2h, 2i). Further, 24.8%±0.8% of MPOA Gal+ cells in females, 26.7%±1.4% in mothers, and 16.8%±0.9% in fathers co-express c-fos (Mean±SEM, paired t-test, P<0.001 for virgin females and fathers, P<0.01 for mothers; Figs. 2j). Gal is also found in minor subsets of mating and aggression-induced c-fos+ cells in males, while overlap between Gal and c-fos induced by pup-directed aggression is not significantly different from chance level (Figs. 2i, 2j).

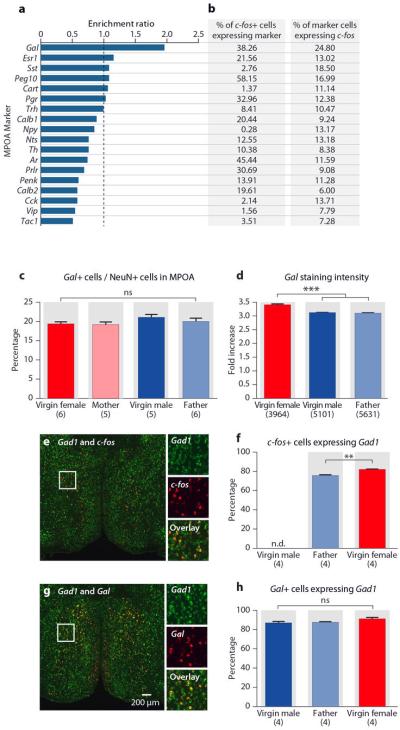

Extended Data Figure 1. Identification of the Gal as marker for cells involved in parenting and characterization of MPOA Gal+ cells.

a, Enrichment ratio of markers in parenting induced MPOA c-fos in virgin females. The enrichment ratio of a given marker is calculated as the percentage of the c-fos+ cells co-expressing the marker, divided by the percentage of NeuN+ cells co-expressing this marker. b, The percentages of parenting induced MPOA c-fos+ cells co-expressing markers and the percentages of marker cells co-expressing c-fos. c, Percentages of Gal+ cells in the MPOA in virgin and sexually experienced males and females fail to identify any sexual dimorphism in MPOA Gal+ cell representation. Mean+SEM, one-way ANOVA, P>0.2. d, Fold increase of Gal mRNA in situ staining intensity compared to background in virgin females, virgin males and fathers. Gal mRNA expression is slightly higher (10% increase) in females than in males. Mean+SEM, one-way ANOVA, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant. e, f, Percentages of c-fos+ cells co-expressing Gad1 in fathers and virgin females. n.d., not determined. Mean+SEM, t-test, **P<0.01. g, h, Percentages of Gal+ cells co-expressing Gad1 in virgin males, fathers and virgin females. Mean+SEM, one-way ANOVA, P>0.1.

Gal is expressed in several brain areas and modulates multiple physiological functions35. Gal is also co-expressed by prolactin-secreting cells of the pituitary and involved in lactation36. We found that MPOA Gal+ cell number is not sexually dimorphic, though MPOA Gal expression level appeared slightly higher in females than males (Extended Data Figs. 1c, 1d). Most MPOA c-fos+ and Gal+ cells express Gad1, characteristic of GABAergic inhibitory neurons (Extended Data Figs. 1e-1h).

Ablation of MPOA Gal+ neurons

We next investigated the requirement of MPOA Gal+ neurons for parental behaviors in females and mated males. We obtained a Gal-Cre transgenic line (GENSAT) and confirmed appropriate Cre expression in MPOA Gal+ neurons: 94.6% of the Gal+ cells co-express Cre (N=858 cells in 2 animals) and 94.8% of the Cre+ cells co-express Gal (725 cells in 2 animals; Extended Data Fig. 2a). To specifically ablate MPOA Gal+ neurons, Gal-Cre mice were given bilateral MPOA injections of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing Cre-dependent diphtheria toxin A fragment (AAV-DTA) (Extended Data Fig. 2b). On average, AAV-DTA eliminated ~60% of MPOA Gal+ cells, compared to Gal-Cre negative littermate controls receiving the same treatment (Extended Data Figs. 2c, 2d). We verified that an independent MPOA cell population expressing thyrotropin releasing hormone (Trh) was not affected by targeted ablation (Extended Data Fig. 2e). Furthermore, neighboring Gal+ cells in the AVPe, paraventricular nucleus (PVN), and dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMH) were unaffected, confirming the spatial specificity of viral-mediated ablations (Extended Data Figs. 2f-2h).

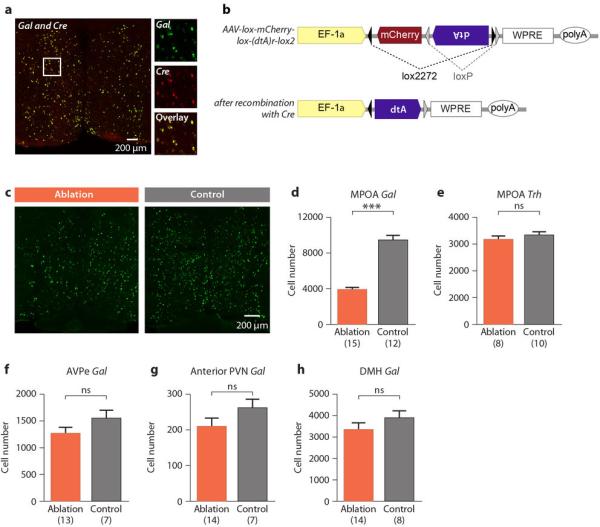

Extended Data Figure 2. Targeted Gal+ cell ablation in the MPOA.

a, Co-labeling of Gal and Cre expressing cells by mRNA in situ hybridization in Gal-Cre females indicates near perfect overlap. b, Schematic map of the Cre-dependent AAV-DTA virus; DTA is doubly flanked by two sets of incompatible lox sites and inverted to enable transcription after Cre-mediated recombination. c, Gal mRNA expression in the MPOA of ablated and control males. d, Number of MPOA Gal+ cells in ablation group compared to controls. Mean+SEM, t-test, ***P<0.001. e, Number of MPOA Trh+ cells in the ablation group and control. Mean+SEM, t-test, P>0.2. f-h, Gal+ cell numbers in the AVPe, anterior part of the PVN and the DMH in MPOA targeted ablation compared to control. Mean+SEM, t-test, P>0.1.

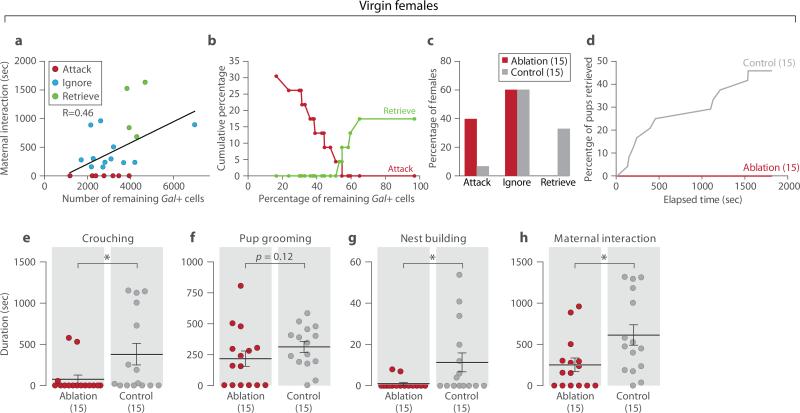

Virgin females with MPOA Gal+ neuron loss showed striking reductions in maternal behavior and emergence of pup-directed aggression (Fig. 3) compared to Gal-Cre negative littermates or Gal-Cre females with AAV-Flex-GFP viral injections (Extended Data Figs. 3a-3f). The duration of overall maternal interaction appeared positively correlated with the number of remaining Gal+ cells (Fig. 3a; N=23, P<0.05, R=0.46). Moreover, while virgin females with low ablation of MPOA Gal+ cells were maternal, females with ablation efficiencies above 50% displayed loss of maternal care with increased pup-directed aggression (Fig. 3b), accompanied by significantly reduced crouching, nest building, retrieval to nest, and maternal interaction compared to controls (Figs. 3c-3h). Thus, MPOA Gal+ cells represent an essential neuronal population for the maternal behavior of virgin females.

Figure 3. Ablation of MPOA Gal+ neurons impairs maternal behavior in virgin females.

a, Linear regression of maternal interaction and the number of remaining MPOA Gal+ cells in ablated virgin females. Animals are color coded by their behavior categories. Pearson correlation, N=23, P<0.05, R=0.46. b, Cumulative percentages of females that retrieved or attacked pups as a function of the percentage of remaining Gal+ cells, N=23. Reference cell number (100%) is the average MPOA Gal+ cell number in the control group. As the remaining number of Gal+ cells increases or decreases on the x-axis, each female is added to the maternal group or the infanticidal group according to its behavior type, respectively. c, Behavior of ablated females with over 50% ablation efficiency (N=15) compared to control (N=15). Chi-square test, P<0.05. d, Combined percentage of pups (out of two) retrieved by the ablation group as a function of time, compared to the controls. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P<0.05. e-h, Crouching, pup grooming, nest building and maternal interaction. Mean±SEM. Mann-Whitney test, *P<0.05.

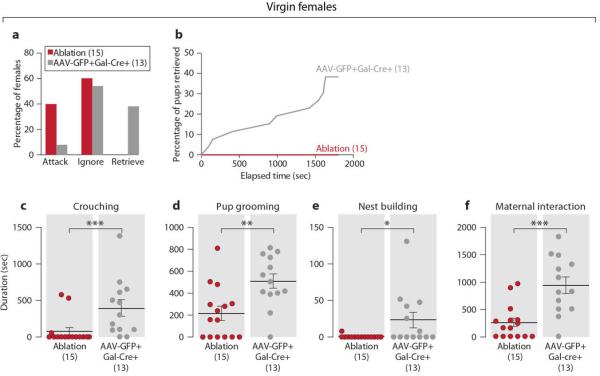

Extended Data Figure 3. Females with MPOA Gal+ cell ablation compared to Gal-Cre+ controls injected with AAV-Flex-GFP.

a, Behavior of MPOA Gal+ cell ablated virgin females with over 50% ablation efficiency (N=15) compared to Gal-Cre+ controls injected with AAV-Flex-GFP (N=13). Chi-square test, P<0.05. b, Percentage of pups retrieved by Gal+ cell ablated virgin females as a function of time compared to the controls. The retrieving data of the two pups in each test are combined. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P<0.05. c-f, Crouching, pup grooming, nest building and maternal interaction in the Gal+ cell ablated virgin females and control. Mean±SEM. Mann-Whitney test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. The control females with the longest crouching and of nest building duration are different individuals.

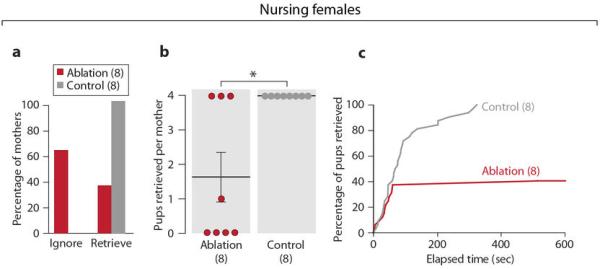

Next, we examined the effects of MPOA Gal+ cell ablation on retrieving behavior of nursing females (Methods). Control mothers retrieved all four pups, while most mothers with loss of over 50% Gal+ MPOA cells failed to retrieve pups, suggesting a critical role of Gal+ cells in maternal behavior of lactating females (Extended Data Figs. 4a-4c).

Extended Data Figure 4. Deficits in retrieving behavior of mothers with MPOA Gal+ cell ablation.

a, Behavior of MPOA Gal+ cell ablated mothers (N=8) compared to controls (N=8). Fisher's exact test, P<0.05. b, Number of pups retrieved by each mother. Mean±SEM. Mann-Whitney test, *P<0.05. c, Percentage of pups retrieved by the ablation group as a function of time compared to the controls. The retrieving data of the four pups in each test are combined. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P<0.001.

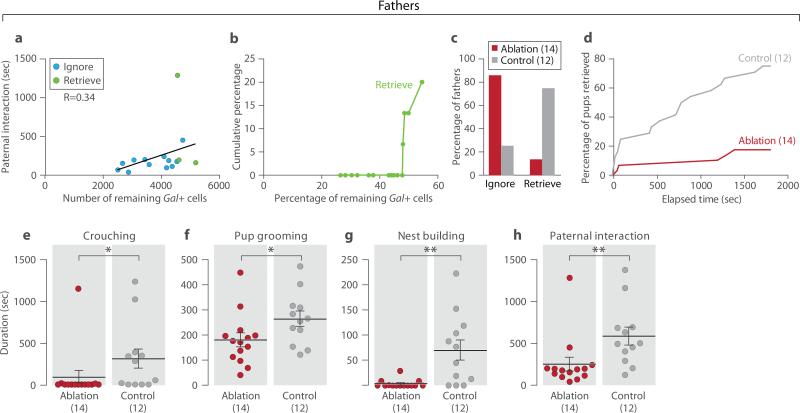

We then tested the requirement of Gal+ neurons for male parental behavior (Methods). As with females, disappearance of parental behavior in males was associated with loss of over 50% of Gal+ cells (Fig. 4a, 4b). Behavior assays showed that only 14.3% of males with over 50% MPOA Gal+ neuronal loss (N=14) displayed paternal behavior 3 weeks after mating, compared to 75% of littermate controls (N=12; Fisher's exact test, P<0.01; Fig. 4c). Ablated animals showed deficits in crouching, pup grooming, nest building, retrieval to nest, and overall paternal interaction compared to controls (Figs. 4d-4h).

Figure 4. Ablation of MPOA Gal+ neurons impairs paternal behavior in fathers.

a, Linear regression of paternal interaction and number of remaining Gal+ cells in the MPOA in ablated fathers. Animals are color coded by their behavior categories. Pearson correlation, N=15, P=0.21, R=0.34. b, Cumulative percentages of paternal males (Retrieve) as a function of the percentage of remaining Gal+ cells, N=15. Reference cell number (100%) is the average MPOA Gal+ cell number in the control group. c, Behavior type of ablated fathers with over 50% ablation efficiency (N=14) compared to control (N=12). Fisher's exact test, **P<0.01. d, Combined percentage of pups retrieved (out of two) by the ablation group as a function of time, compared to the controls. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P<0.001. e-h, Crouching, pup grooming, nest building and paternal interaction. Mean±SEM, Mann-Whitney test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

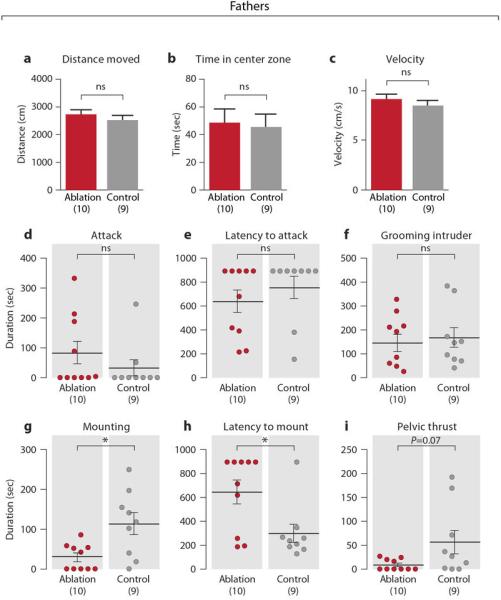

Gal+ cell ablation did not affect locomotion or inter-male aggression (Extended Data Figs. 5a-5f), but decreased mounting duration and increased latency to mount (Extended Data Figs. 5g-3i). This mating defect may result from ablation of the small subset of MPOA Gal+ cells activated during mating or from interactions between brain circuits controlling parenting and mating.

Extended Data Figure 5. Mating, inter-male aggression and locomotor activity of MPOA Gal+ cell ablated fathers.

a-c, Locomotor behavior of MPOA Gal+ cell ablated and control fathers in a 5 min test in an open arena, measuring the distance moved, time spent in the center zone and the average velocity. Mean+SEM, t-test, P>0.3. d-f, Inter-male aggression of MPOA Gal+ cell ablated and control fathers, measuring duration of attack, latency to attack and duration of grooming the intruder. Mean±SEM. Mann-Whitney test, P>0.2. g-i, Duration of mounting, latency to mount and duration of mounting with pelvic thrust of MPOA Gal+ cell ablated fathers compared to controls. Mean±SEM. Mann-Whitney test, *P<0.05.

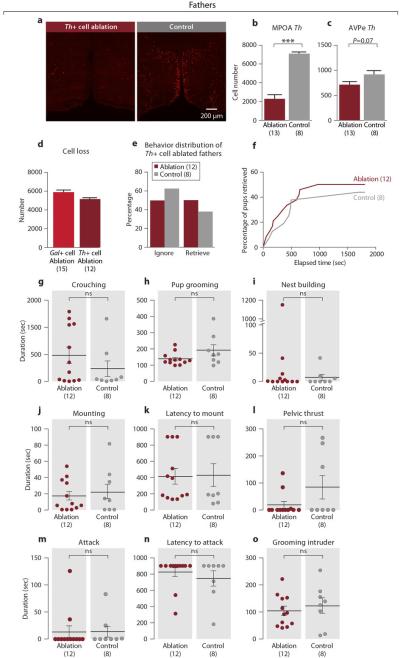

To further assess the functional specificity of MPOA Gal+ cells in behavior control, we examined the effect of ablating MPOA tyrosine hydroxylase (Th) cells using AAV-DTA in Th-IRES-Cre males37. ~70% of Th+ cells were ablated compared to littermate controls (Extended Data Figs. 6a, 6b). The ablation was restricted to the MPOA, as the AVPe Th+ cells were largely unaffected (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Although MPOA Th+ cell loss was comparable to Gal+ cell loss (Extended Data Fig. 6d), it did not affect parenting, mating, or inter-male aggression in males (Extended Data Figs. 6e-6o), highlighting the critical role of Gal+ cells in the control of parenting.

Extended Data Figure 6. Parenting, mating and inter-male aggression of MPOA Th+ cell ablated fathers.

a, Th mRNA expression in the MPOA of Th+ cell ablated and control fathers b, Number of MPOA Th+ cells in ablation group compared to controls. Mean+SEM, t-test, ***P<0.001. c, Number of AVPe Th+ cells in MPOA targeted ablation. Mean+SEM, t-test, P=0.07. d, The number of MPOA Th+ cell loss compared to the Gal+ cell ablation experiments. One male had a failed Th+ cell ablation and was removed from the dataset hereafter. The Th+ cell loss is ~87% of the Gal+ cell loss. e, Behavior type of MPOA Th+ cell ablated fathers compared to controls. Fisher's exact test, P>0.6. f, Combined percentage of pups (out of two) retrieved by the Th+ cell ablation group as a function of time compared to the controls. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P>0.9. g-i, Crouching, pup grooming and nest building in the Th+ cell ablated fathers and control. Mean±SEM. Mann-Whitney test, P>0.2. The control male with the longest pup grooming also has the longest nest building activity, but not the longest duration of crouching. j-l, Duration of mounting, latency to mount and duration of mounting with pelvic thrust of MPOA Th+ cell ablated males compared to control in a mating assay. Mean±SEM. Mann-Whitney test, P>0.3. m-o, Duration of attack, latency to attack and duration of grooming the intruder in MPOA Th+ cell ablated males compared to control in an inter-male aggression assay. Mean±SEM. Mann-Whitney test, P>0.3.

Remarkably, specific ablation of Gal+ cells affected all major aspects of parental behavior. Additionally, while a significant fraction of virgin females with strong reduction in Gal+ neurons attacked pups, no mated males or nursing females with high ablation efficiency displayed pup-directed aggression. This result suggests that, in virgin females, Gal+ neurons are important for both maternal behavior and inhibition of pup-directed aggression, while in fathers and mothers, mating suppresses circuits for pup-directed aggression independently of Gal+ neuronal activation.

Activation of MPOA Gal+ neurons

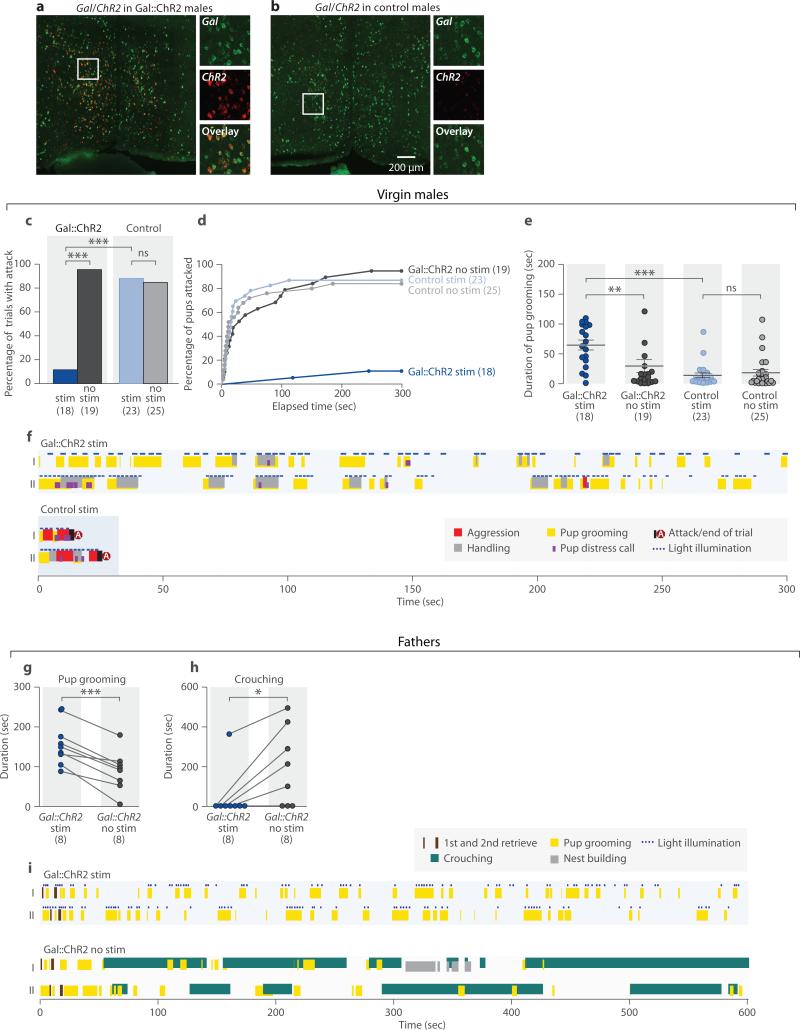

To address whether activation of MPOA Gal+ neurons is sufficient to suppress pup-directed aggression and potentiate parental behavior, virgin males and fathers were tested during optogenetic activation of Gal+ neurons. Gal-Cre males were given MPOA-targeted injections of a Cre-dependent channelrhodopsin-2 fused with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein virus (AAV-ChR2:EYFP) and implanted with an optic fiber. Negative controls were Gal-Cre negative littermates receiving the same treatment. In stimulation trials, blue light was delivered to the MPOA whenever the male contacted a pup with its snout. Postmortem mRNA in situ hybridization confirmed specific MPOA ChR2:EYFP expression in Gal+ cells (Figs. 5a, 5b). ~60% of MPOA Gal+ cells expressed AAV-ChR2:EYFP, similar to the expression of AAVDTA in ablation experiments (Extended Data Fig. 9k). Additionally, we verified that parenting-induced c-fos+ and c-fos- subpopulations of Gal+ cells showed comparable viral infection rates (Extended Data Fig. 9k). Light stimulation in awake behaving animals produced strong c-fos induction in MPOA Gal+ cells of Gal::ChR2 males, but not control males (33.5%±3.3% for Gal::ChR2 males, 6 animals; 4.1%±0.2% for controls, 8 animals; Mean±SEM, t-test, P<0.001).

Figure 5. Optogenetic activation of MPOA Gal+ neurons in males suppresses attack and promotes pup grooming.

a-b, Co-labeling Gal and ChR2:EYFP expression in the MPOA of the Gal::ChR2 and control males. c, Percentage of trials with attacks of pups by virgin males. Fisher's exact test with Bonferroni correction, ***P<0.001, ns. not significant. d, Percentage of pups attacked by each group of virgin males. Gal::ChR2 stim trials are significantly different from Gal::ChR2 no stim and control stim trials. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Bonferroni correction, P<0.001. e, Pup grooming in the tests with virgin males. Mean±SEM; Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns. not significant. f, Sample behavior raster plot of Gal::ChR2 stim and control stim trials in virgin males. Note that two behavior elements (such as pup grooming and handling) can occur simultaneously. g, Pup grooming in the tests of fathers. N=8 for each group, t-test pairing the same animal with and without light stimulation, ***P<0.001. h, Crouching in the tests of fathers. N=8, paired t-test, *P<0.05. i, Sample behavior raster plot of Gal::ChR2 stim and Gal::ChR2 no stim trials in tests with fathers.

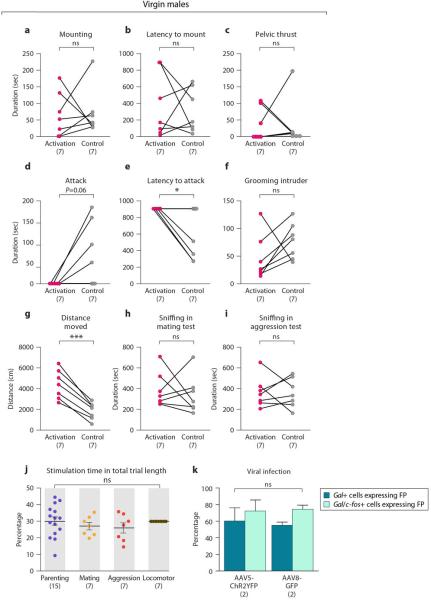

Extended Data Figure 9. Mating, inter-male aggression and locomotor activity of virgin males with MPOA Gal+ cell activation and controls of light stimulation and viral infection.

a-c, Duration of mounting, latency to mount and duration of mounting with pelvic thrust in virgin males with Gal+ cell activation compared to controls in a mating assay. Paired t-test, P>0.7. d-f, Duration of attack, latency to attack and duration of grooming the intruder in virgin males with Gal+ cell activation compared to controls in an inter-male aggression assay. Paired t-test, *P<0.05, ns. not significant. g, Distance moved in virgin males with Gal+ cell activation compared to controls. Paired t-test, ***P<0.001. h, i, Time spent sniffing the intruder in mating and inter-male aggression assay. Paired t-test, P>0.6. j, The duration of light stimulation in each behavior test as a percentage of the total trial length. Mean+SEM, one-way ANOVA, P>0.6. k, The percentages of Gal+ and Gal/c-fos+ cells co-expressing fluorescent protein, in females injected with AAV5-Flex-ChR2-EYFP or AAV8-Flex-GFP after maternal interaction with pups. Mean+SEM, two-way ANOVA examining the differences in the infection of the two viruses and the two cell populations, P>0.2 for both factors and the interaction between them.

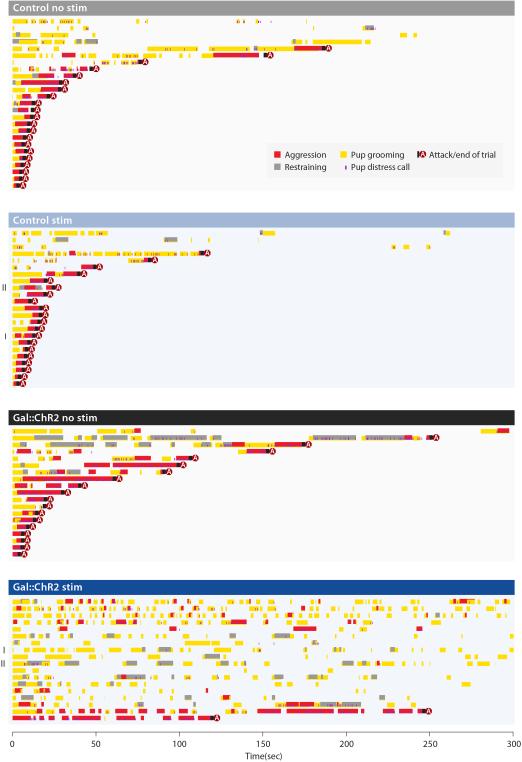

We first investigated whether Gal+ cell activation reduced pup-directed aggression. Each male was tested multiple times with stimulation (stim) and non-stimulation (no stim) (Methods). Light stimulation of MPOA Gal+ neurons in Gal::ChR2 males inhibited attacking in 16 of 18 trials (6 animals, 2-4 trials per animal), whereas the same animals attacked in 18 of 19 trials without stimulation (Fig. 5c, 5d). Loss of pup-directed aggression was not due to pup-avoidance, as light stimulated Gal::ChR2 virgin males displayed frequent and lengthy bouts of pup grooming not observed in controls (Fig. 5e, 5f; Extended Data Fig. 7). However, light stimulation did not significantly alter the behavior of control virgin males (Fig. 5c-5f; Extended Data Fig. 7).

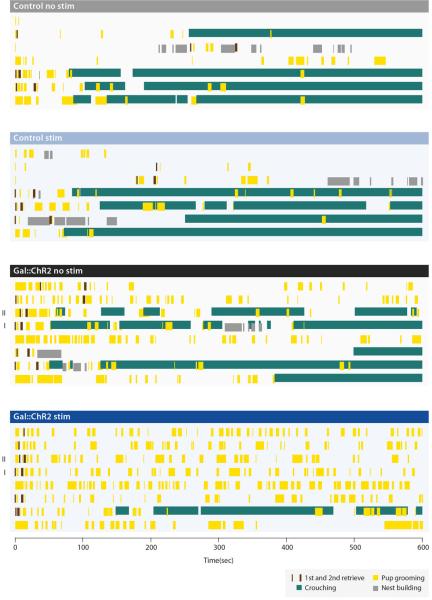

Extended Data Figure 7. Behavior raster plot of Gal::ChR2 and control virgin males with and without light illumination.

Each row represents a single trial lasting for 5 min or until the male attacked the pup. Trials are grouped by experiment conditions and sorted by trial length. Roman numerals indicate the sample trials shown in Fig. 5f. Various elements of the behavior are color coded and labeled in the insert.

We next observed effects of light stimulation on parental behavior of fathers (Methods). Light stimulation elicited strikingly elevated pup grooming in Gal::ChR2 compared to non-stimulated fathers (Figs. 5g, 5i; Extended Data Fig. 8). Interestingly, induction of active pup grooming in Gal::ChR2 stimulated males was seen at the expense of crouching (Figs. 5h, 5i; Extended Data Fig. 8).

Extended Data Figure 8. Behavior raster plot of mated Gal::ChR2 and control males with and without light illumination.

Each row represents a 10-min trial. Trials are grouped by experiment conditions. Roman numerals indicate the sample trials shown in Fig. 5i. Various elements of the behavior are color coded and labeled in the insert.

To address the specificity of Gal+ cell activation in parental behavior, we also tested other behaviors. Gal+ cell activation left mating behavior unaffected but diminished inter-male aggression and increased locomotion (Extended Data Figs. 9a-9g), while length of social contact was equivalent in control and stimulation trials across assays (Extended Data Figs. 9h, 9i). Duration of light illumination was also comparable across all stimulation experiments (Extended Data Fig. 9j).

These results indicate that optogenetic activation of MPOA Gal+ cells is sufficient to suppress pup-directed aggression and induce active pup grooming. The suppression of inter-male aggression and increased locomotion may result from increased parenting and pup-seeking, or from other unknown behavioral drives. Surprisingly, while ablation of Gal+ cells leads to mating defects, activation of these cells did not increase mating. This may reflect unknown complexity in social circuit coding, or originate from slightly different virus infectivity in ablation and activation experiments.

Discussion

Our data provide significant insights into the control of opposing social behaviors in mice: parenting versus pup-directed aggression. While vomeronasal circuits in virgin males mediate aggression toward pups, this response is silenced in females and mated males, and neuronal pathways underlying parental care are activated instead. We show here that MPOA Gal-expressing cells are critical for the control of mouse parental behavior and the suppression of pup-directed aggression, thus acting as a central regulatory node of social interactions with pups. Manipulation of this genetically defined neuronal population switches on or off the parental behavior of mice, providing a precious entry point for further dissection of neural circuits underlying parental care and their modulation by social experience. The functional heterogeneity among Gal+ cells, also reported in most neuropeptide-expressing neurons38–40, may underlie the observed modulation of other social behaviors. A more refined characterization of Gal+ neuron subpopulations may help identify subsets of MPOA neurons involved in distinct behaviors.

Interestingly, ablation of MPOA Gal+ neurons leads to reductions in all tested aspects of parenting, while MPOA Gal+ neuron activation triggers pup grooming but no other parental displays. An understanding of the natural pattern of MPOA Gal+ neuron activity during parental interactions, particularly during intense care such as grooming versus more passive display like huddling with pups, may help optimize ChR2-mediated stimulation of MPOA Gal+ neurons and its behavioral outcome. Additionally, although MPOA Gal+ neuronal activity appears essential for parenting behavior, some behavioral displays may require simultaneous activation of additional neuronal populations. Interestingly, activation of MPOA Gal+ neurons increases locomotion without affecting social contact and decreases inter-male aggression, suggesting complex functional relationships between parenting and other behavior circuits.

From our results, the relationship between circuits mediating parental care and pup-directed aggression appears complex and modulated by social experience. Virgin males with activated MPOA Gal+ neurons do not attack pups, indicating that these neurons directly suppress pup-directed aggression. Indeed, loss of MPOA Gal+ neurons impairs parental behavior and elicits pup-directed aggression in virgin females. However, MPOA Gal+ neuron ablation suppresses parental behavior without facilitating pup-directed aggression in mothers or fathers, suggesting that circuits underlying pup-directed aggression are silenced in mated animals through independent mechanisms. Future circuit-level analysis of MPOA Gal+ neurons will help uncover mutual connections between circuits underlying parenting, pup-directed aggression, and mating, and assess connectivity with other brain areas participating in parenting12,41.

Finally, a variety of hormones and neuropeptides, including estradiol, testosterone, prolactin, progesterone, and oxytocin, modulate parenting according to the physiological state of the animal and its social context42–49. It will be interesting to determine if Gal, a neuropeptide involved in modulation of many homeostatic and reproductive functions is a new player in the regulation of parental behavior.

Methods

Animals

Animals were maintained on 12h: 12h light/dark cycle (lighted hours: 02:00-14:00) with food and water available ad libitum. Animal care and experiments were carried out in accordance with the NIH guidelines and approved by the Harvard University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Trpc2 knockout mice of C57BL/6J x129/Sv mixed genetic background were generated previously in our laboratory. The complete null allele of the Trpc2 gene locus was confirmed by Western blotting15.

The Gal-Cre BAC transgenic line (STOCK Tg(Gal-cre)KI87Gsat/Mmucd, 031060-UCD) was imported from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center. In this line, a Cre recombinase cassette followed by a polyadenylation sequence is inserted at the ATG codon of the first coding exon of the Gal gene. The imported line was in an FVB/N-Crl:CD1(ICR) mixed genetic background and backcrossed to C56BL/6J genetic background in our breeding colony. The animals used in the study came from the F1 generation.

The Th-IRES-Cre knock-in line was imported from the European Mouse Mutant Archive (00254). An IRES-Cre construct was inserted in the 3' untranslated end of the Th gene. The Th expression is not affected and Cre protein is produced in Th-expressing cells37. This line was generated originally in a mixed genetic background of 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J and then back crossed to C57BL/6J.

Behavior assay

Before behavior tests animals were housed individually for about one week. Experiments started at the beginning of the dark phase and were performed under dim red light, unless noted otherwise. Each test was videotaped (Sony DCR-HC65 camcorder in nightshot mode, Microsoft LifeCam HD-5000 or Geovision surveillance system) and the behaviors were scored by an individual blind to the genotype using the Observer 5.0 or XT 11 software (Noldus Information Technology). When one animal is tested in multiple behavior assays, they are allowed at least 48 hours rest between tests.

Parental behavior assay of Trpc2 knockout animals

2- to 4-month-old, Trpc2+/− and Trpc2−/− virgin male and female littermates were individually housed for approximately one week before the test. 1- to 3-day-old naïve C57BL/6J pups were used as the standard pup intruder in all the behavior assays performed in this study. The pups are of a different strain from the Trpc2−/− and Trpc2−/− animals and therefore are not related to the resident animals. The pregnant females were separated from the stud before parturition, so the pups are not exposed to their fathers and do not carry any adult male odor. Four naïve C57BL/6J pups were introduced to the home cage of each animal and placed at the farthest corner from the resident's resting nest. The first olfactory investigation marked the beginning of the assay, which then extended until 30 minutes after all the pups were retrieved, or until the resident attacked and wounded the pups, or for 30 minutes in case neither of above happened. When a pup was attacked, the assay was ended immediately and the wounded pup was euthanized.

The behavior of the animals was categorized based on the following criterion: Animals that retrieved all the pups to the nest or built a new nest around the pups within 30 minutes and crouched over pups were categorized as “Retrieve”. Animals that attacked the pups within 30 minutes were scored as “Attack”. All the other animals were categorized as “Ignore”. In most of the cases, retrieving is an all-or-none event such that if an animal retrieves one pup, it retrieves all the pups. An animal is scored as “Ignore” if it does not retrieve all four pups or does not crouch over them after retrieval. Following IACUC guidelines, behavior assays must be stopped before animal attacking pups have the ability to kill them. Thus, to accurately describe the attack behavior, we mainly used “pup-directed aggression” or “attack” instead of “infanticide”.

The following behaviors were scored: latency to retrieve each pup (picking up a pup with its mouth and carrying it to the nesting area), latency to attack (biting a pup, often accompanied by actual wounds on the pup and confirmed immediately after the test), grooming (sniffing and licking a pup), crouching (extending its limbs, assuming a nursing-like posture and huddling over at least 2 pups), nest building (collecting and arranging nesting material and making a nest), time spent in the nest and parental interaction (“maternal interaction” for females and “paternal interaction” for males; calculated as the cumulative time spent crouching, grooming pups, and nest-building). Grooming, crouching, time in the nest and nest building were scored as duration during the 30-minute recording after all the pups were retrieved. The latencies to retrieve or attack pups were recorded in seconds. Some behavioral variability is observed in control animals across various experiments due to the different genetic background of the transgenic lines used in each experiment. Trpc2+/− females are in C57BL/6J x129/Sv mixed genetic background. Gal-Cre animals were originally in FVB/N-Crl:CD1(ICR) mixed genetic background and were backcrossed to C56BL/6J in our breeding colony. Gal-Cre virgin females used in the study were from an F1 generation, and exhibited lower level of maternal behavior than Trpc2+/− virgin females.

Parental behavior assay for mated males (Fig. 1g)

Trpc2+/− virgin males were individually housed and then paired with females, which were checked daily for vaginal plugs in the next few days. Once a plug was spotted, the day was marked as Day 0 for the mating pair and that pair was randomly assigned to a group for different length of cohabitation (1-2 days, 10-12 days, 17-20 days or 25-27 days). According to their group, the males were tested one day after the females and their litters (if any) were removed from their home cage. For example, animals tested on Day 1 were separated from their mates on Day 0. The animal tested on Day 20 was separated from its mate on Day 19 and was not exposed to its own litter. The negative controls for this essay were individually housed Trpc2+/− virgin males.

Mating behavior assay

~8 weeks old, receptive virgin females (as determined by vaginal smear) of C57BL/6J background were introduced to the resident mouse cage. Each test runs for 15 min and was videotaped and scored for the following parameters: sniffing, mounting and mounting with pelvic thrust.

Inter-male aggression assay

~8 weeks old, castrated male of C57BL/6J background (castration performed by the Jackson Laboratory) swabbed with 50ul fresh urine from intact wild-type males were introduced to the resident mouse cage. Every 15min test was videotaped and scored for the following parameters: attack, sniffing and grooming intruder.

Open field test

Animals are tested for 5 min in a 60cm × 60cm square open arena under normal lighting. The position of the animals is tracked and analyzed by Ethovision XT 8 software to calculate the distance moved, average velocity and the time spent in the center zone. The center zone is defined as the center square (42cm × 42cm) which comprises 50% of the total area.

RNA in situ hybridization

Fresh brain tissues were collected from animals housed in their home cage or 35 minutes after the start of the behavior tests when c-fos expression is analyzed. For social behavior induced cfos analysis, the behavior paradigm is generally as described in the Behavior assay section. Only animals that actually displayed a certain behavior were selected, i.e. males that displayed mounting behavior or females that were mounted were selected for mating induced c-fos analysis, males that attacked intruder for inter-male aggression induced c-fos analysis, animals that crouched over pups in a nest for parenting induced c-fos analysis, and males that attacked pups for c-fos induced by pup-directed aggression. The dissected brains were embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek) and frozen with dry ice. 20μm cryosections were used for mRNA in situ hybridization. Adjacent sections from each brain were usually collected over a few replicate slides to generate copies for staining with multiple probes.

Fluorescent mRNA in situ hybridization was performed largely as described50. Complementary DNA of c-fos, Gal, Trh, Th, Gad1, Vglut2, EYFP, GFP, ChR2, Cre, mCherry mRNA and other MPOA molecular markers (Esr1, Esr2, Cyp19a1, Ar, Pgr, Prlr, Hcrt, Cart, Tac1, Penk, Bdnf, Peg10, Pvalb, Calb1, Calb2, Vip, Nos1, Cck, Sst, Nts, NR5a1, Npy) were cloned in approximately 800-base-pair (whenever possible) segments into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Antisense cRNA probes were synthesized with T7 or Sp6 polymerases (Promega) and labeled with digoxigenin (DIG; Roche), fluorescein (FITC; Roche) or dinitrophenol (DNP; PerkinElmer). Where necessary and possible, a cocktail of 2-4 probes were generated covering different segments of the target mRNA to maximize strength of signal.

mRNA hybridization was performed with 0.5-1.0 ng/μl cRNA probes at 68°C. The probes were detected using horseradish peroxidase (POD)-conjugated antibodies (anti-FITC-POD at 1/250 dilution, Roche; anti-DIG-POD at 1/500 dilution, Roche; anti-DNP-POD at 1/100 dilution, PerkinElmer). The signals were amplified using Biotin conjugated tyramide (PerkinElmer) and subsequently visualized with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated streptavidin or Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen), or directly visualized with TSA plus cyanine 3 system, TSA plus cyanine 5 system or TSA plus Fluorescein system (PerkinElmer). Tissues were mounted with Vectashield (Vector labs) containing 8μg/ml DAPI.

For catFISH, animals were subject to two 5-minute episodes of behaviors interleaved with a 30 min interval, and were euthanized immediately after the second episode. The c-fos cytoplasmic signal induced by the first behavior episode was compared to the c-fos nuclear signal induced by the second, allowing direct comparison of the two activated cell populations. The same cRNA cfos probes described above were used to detect cytoplasmic signal as well as nuclear signal, and an intron probe51 containing the first intron of the c-fos gene was used to detect only the nuclear signal.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed according to standard protocols. NeuN was detected with primary antibody Mouse Anti-NeuN (1:3000; Millipore, MAB377) and then amplified by Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:500; Life Technologies).

Image analysis and cell counting

All the microscopy images were acquired with AxioImager Z2 and AxioVision software with a 10X objective (Zeiss). Brain areas were determined based on landmark structures and white matters such as the ventricles, anterior commissure and optic tract, with the occasional assistance of Nissl staining and other area-specific molecular markers on adjacent sections when necessary. Areas of interest in the c-fos expression analysis included the MPOA, anteroventral periventricular nucleus, bed nucleus of stria terminalis, medial amygdala, posteromedial cortical amygdala, nucleus accumbens, lateral septal nucleus, suprachiasmatic nucleus, paraventricular nucleus, anterior basomedial nucleus, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus and dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus. After manual assignment of brain structures, automated cell counting was performed using ImageJ with custom-written macro scripts. Sample images were manually counted by experimenters blind to the test condition to verify the reliability of automated cell counting. For a given brain area, the absolute cell number was determined by summing up the cell counts of all the sections deemed as part of that area, adjusted by the number of the slicing replicates collected in cryosectioning.

Targeted cell ablation in the MPOA

The rAAV8/EF1α-mCherry-Flex-dtA (AAV-DTA) construct was generated using the A subunit of the diphtheria toxin gene from a PGKdtabpA plasmid (Addgene plasmid 13440)52. The recombinant vectors were then serotyped with AAV8 coat proteins and packaged by the viral vector core at the University of North Carolina. AAV-DTA (4×1012 viral particles/ml) was injected bilaterally in the MPOA of Gal-Cre or Th-IRES-Cre males in the amount of 0.8 μl on each side (Bregma: 0.0mm, midline: +0.5mm; dorsal surface: −5.0mm) with Nanoject II injector (Drummond Scientific). The negative control for Gal+ cell ablation consisted of Cre- littermates receiving the same treatment. In the cell ablation of nursing mothers, one animal injected with AAV-Flex-taCasp3-TEVp53 (3×1012 viral particles/ml) to achieve better ablation efficiency was included in the data.

The AAV-CAG-Flex-GFP (AAV-GFP) construct was developed by Dr. Edward Boyden and it was packaged in serotype 8 by viral vector core at the University of North Carolina. AAV8-GFP (6×1012 viral particles/ml) was injected in the same manner as described above in Gal-Cre+ animals as controls for Gal+ and Th+ cell ablation. It was also used to assess the infection rate of the MPOA Gal+ and parenting-induced c-fos+ cells, since AAV-DTA infection leads to cell death and prevents an accurate estimation. To test the infection rates, Gal-Cre females with AAV-GFP injections were subject to a standard parental assay and then analyzed by Gal/cfos/GFP triple mRNA in situ hybridization.

For parental behavior, virgin females were allowed about 4 weeks of recovery, enabling optimal DTA expression and cell ablation before behavior testing. Each female was individually housed and tested with two C57BL/6 pups, in a similar manner as desribed earlier. Retrieving, attacking, crouching, pup grooming, nest building and overall maternal interaction were scored. For parental behavior test of the fathers, males were allowed about one week of recovery after surgery and then paired with females until the females gave birth (~3 weeks). 1-2 days after the pups were born, males were separated from their mates and litters, individually housed for 2-3 days and tested in a 30-minute behavior assay with two C57BL/6J pups. Retrieving, attacking, crouching, pup grooming, nest building and overall paternal interaction were scored. For mothers, females were allowed about one week of recovery after injection and then paired with males, which were removed from the females about 1 week before term. On P0, after removing the litters from a mother, 4 of the pups were re-introduced into the cage and retrieving behavior was observed for 10 minutes. The brains were harvested after behavior assays for histological analysis.

ChR2-mediated cell activation

The AAV-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R):EYFP (AAV-ChR2:EYFP) construct was a gift of Dr. Karl Deisseroth54 and the recombinant AAV vectors were serotyped with AAV5 coat proteins and packaged by the viral vector core at the University of North Carolina. Gal-Cre males were tested with pups and those attacked pups were selected for surgery. 0.8 μl of AAV-ChR2 (4×1012 viral particles/ml) was injected bilaterally into the MPOA of Gal-Cre males (Bregma: 0.0mm, midline: +0.5mm; dorsal surface: −5.0mm) using Nanoject II injector (Drummond Scientific). After injection, a small plastic adaptor holding an optical fiber (300μm diameter; Polymicro technologies) was implanted above the MPOA and affixed to the skull with dental cement (Bregma: 0.0mm, midline: +0.2mm; dorsal surface: −4.2mm). The implant was positioned close to the midline to cover the MPOA in both hemispheres and lowered to a depth of approximately 0.8mm above the center of the AAV injection. A threaded plastic cap (Plastics One) was used to cover the implant during recovery and between experiment sessions. Gal-Cre negative males treated with the same procedure were the negative controls.

The males were tested after at least 2 weeks of recovery. Before stimulation, the implant was connected to an optical fiber (300μm diameter, Polymicro technologies), which was connected in turn to a blue laser via an optical commutator permitting free movement of the animals. The optic fiber was flexible and long enough to allow the animal to freely behave and interact with the intruder. Both Gal::ChR2 and control animals were tested for 2-4 trials with stimulation (stim) and non-stimulation (no stim) trials randomly assigned in 1:1 ratio. In each trial, one C57BL/6J pup was introduced to the male's home cage to minimize the number of pups used in this assay, as most of the males are likely to attack pups. Blue light (473nm) was delivered in 30ms pulses at 20Hz for 1-4s whenever the male contacted the pup with its snout. The light power exiting the fiber tip was at ~10-20mW, ensuring a light intensity above ~1.0mW/mm2 over the entire MPOA55. There was almost no leakage of light from the optic fiber or the adaptor. Each trial was up to 5 minutes but when the male attacked and wounded the pup, the trial was ended and the pup was euthanized immediately. The following behavior was scored and quantified: pup grooming (as the male sniffs or licks the pup), handling (as the male holds the pup with two forepaws), aggression (as the male grabs the pup violently and attempts to bite, usually does not wound the pups but cause them to struggle and make distress calls) and pup distress calls (only audible calls were recorded).

For paternal behavior assays, the Gal::ChR2 and the control males were paired with females. After their pups were born, the females and the pups were removed and the males were tested in their home cage by introducing two C57BL/6J pups. Each male was tested in two 10-minute trials with one stimulation and one non-stimulation trial in randomized order. Blue light is delivered when the males sniff or lick the pups. None of the males attacked pups or displayed obvious aggression. Retrieving, pup grooming, crouching and nest building behaviors were scored and quantified as described above.

After behavior assays, the brain tissues of these animals were harvested after a standard c-fos induction protocol to analyze the efficiency of viral infection and cell activation. A train of light was delivered in 30ms pulses at 20Hz for 2s, repeated every 10s for 15 minutes, at experimental light intensity. Co-labeling between Gal, ChR2:EFYP and c-fos was analyzed by mRNA in situ hybridization. Two Gal::ChR2 animals with less than 20% of MPOA Gal+ cells expressing c-fos were discarded from the group. The fiber implants from both Gal::ChR2 and control animals were verified for efficient light transmission.

Statistics

The sample sizes in our study were chosen based on common practice in animal behavior experiments. Data were first tested with Lilliefors test for normality. If the null hypothesis that the data come from a normal distribution cannot be rejected, Student's t-test was used. Otherwise, the Mann-Whitney test was used. Due to the strong non-normality of the behavior data, Mann-Whitney test was used for all the behavior analysis. For categorical data, Fisher's exact test was used.

Acknowledgement

We thank K. Deisseroth for the Cre-dependent AAV-ChR2:EYFP construct; E. Boyden for the Cre-dependent AAV-GFP construct; N. Shah for the AAV-Flex-taCasp3-TEVp virus; S. Sullivan for behavior annotation and scoring; R. Hellmiss for figure artwork; E. Soucy and J. Greenwood for technical assistance. We also thank members of the Dulac and Uchida laboratories and V. Murthy, A. Schier and M. Meister for advice on experiments and statistical analysis and comments on the manuscript, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and comments. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Institute of Health (NIDCD).

Footnotes

Contributions

Z.W. and C.G.D. conceived and designed the study. Z.W. and A.E.A performed the experiments and collected the data. J.F.B. and Z.W. developed the setup for ChR2-mediated cell activation. M.W. constructed the AAV-DTA virus. Z.W. and C.G.D. interpreted the results and wrote the paper with comments from A.E.A., J.F.B. and M.W.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Numan M, Insel TR. The Neurobiology of Parental Behavior. Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lonstein JS, De Vries GJ. Sex differences in the parental behavior of rodents. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2000;24:669–86. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown R. Hormonal and experiential factors influencing parental behaviour in male rodents: an integrative approach. Behavioural Processes. 1993;30:1–27. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(93)90009-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenblatt J. Nonhormonal basis of maternal behavior in the rat. Science. 1967;156:1512–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3781.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terkel J, Rosenblatt JS. Maternal behavior induced by maternal blood plasma injected into virgin rats. Journal of comparative and physiological psychology. 1968;65:479–82. doi: 10.1037/h0025817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moltz H, Lubin M, Leon M, Numan M. Hormonal induction of maternal behavior in the ovariectomized nulliparous rat. Physiology & behavior. 1970;5:1373–7. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(70)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svare B, Mann M. Infanticide: Genetic, developmental and hormonal influences in mice. Physiology & Behavior. 1981;27:921–927. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks RJ, Schwarzkopf L. Factors affecting incidence of infanticide and discrimination of related and unrelated neonates in male Mus musculus. Behavioral and neural biology. 1983;37:149–61. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(83)91159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labov JB. Factors influencing infanticidal behavior in wild male house mice (Mus musculus). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1980;6:297–303. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saal F, Vom & Howard L. The regulation of infanticide and parental behavior: implications for reproductive success in male mice. Science. 1982;215:1270–1272. doi: 10.1126/science.7058349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vom Saal FS. Time-contingent change in infanticide and parental behavior induced by ejaculation in male mice. Physiology & behavior. 1985;34:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Numan M, Stolzenberg DS. Medial preoptic area interactions with dopamine neural systems in the control of the onset and maintenance of maternal behavior in rats. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2009;30:46–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Numan M. Medial preoptic area and maternal behavior in the female rat. Journal of comparative and physiological psychology. 1974;87:746–59. doi: 10.1037/h0036974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segovia S, Guillamón A. Sexual dimorphism in the vomeronasal pathway and sex differences in reproductive behaviors. Brain research. Brain research reviews. 1993;18:51–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90007-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stowers L, Holy TE, Meister M, Dulac C, Koentges G. Loss of sex discrimination and male-male aggression in mice deficient for TRP2. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2002;295:1493–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1069259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimchi T, Xu J, Dulac C. A functional circuit underlying male sexual behaviour in the female mouse brain. Nature. 2007;448:1009–14. doi: 10.1038/nature06089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mennella JA, Moltz H. Infanticide in the male rat: the role of the vomeronasal organ. Physiology & behavior. 1988;42:303–6. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tachikawa KS, Yoshihara Y, Kuroda KO. Behavioral Transition from Attack to Parenting in Male Mice: A Crucial Role of the Vomeronasal System. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:5120–5126. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2364-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming A, Vaccarino F, Tambosso L, Chee P. Vomeronasal and olfactory system modulation of maternal behavior in the rat. Science. 1979;203:372–374. doi: 10.1126/science.760196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liman ER, Corey DP, Dulac C. TRP2: a candidate transduction channel for mammalian pheromone sensory signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:5791–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elwood RW. Inhibition of infanticide and onset of paternal care in male mice (Mus musculus). Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1985;99:457–467. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calamandrei G, Keverne EB. Differential expression of Fos protein in the brain of female mice dependent on pup sensory cues and maternal experience. Behavioral neuroscience. 1994;108:113–20. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arendash GW, Gorski RA. Effects of discrete lesions of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area or other medial preoptic regions on the sexual behavior of male rats. Brain research bulletin. 1983;10:147–54. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(83)90086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dominguez JM, Hull EM. Dopamine, the medial preoptic area, and male sexual behavior. Physiology & behavior. 2005;86:356–68. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powers B, Valenstein E. Sexual receptivity: facilitation by medial preoptic lesions in female rats. Science. 1972;175:1003–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4025.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaff DW, Sakuma Y. Facilitation of the lordosis reflex of female rats from the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. The Journal of physiology. 1979;288:189–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakker J, Woodley SK, Kelliher KR, Baum MJ. Sexually dimorphic activation of galanin neurones in the ferret's dorsomedial preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus after mating. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2002;14:116–25. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1331.2001.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McAllen RM, Tanaka M, Ootsuka Y, McKinley MJ. Multiple thermoregulatory effectors with independent central controls. European journal of applied physiology. 2010;109:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jennes L, Conn P. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and its receptors in rat brain. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 1994;15:51–77. doi: 10.1006/frne.1994.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guzowski JF, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Worley PF. Environment-specific expression of the immediate-early gene Arc in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Nature neuroscience. 1999;2:1120–4. doi: 10.1038/16046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simerly RB, Gorski RA, Swanson LW. Neurotransmitter specificity of cells and fibers in the medial preoptic nucleus: an immunohistochemical study in the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1986;246:343–63. doi: 10.1002/cne.902460305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simerly RB, Swanson LW. The organization of neural inputs to the medial preoptic nucleus of the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1986;246:312–42. doi: 10.1002/cne.902460304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Projections of the medial preoptic nucleus: a Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin anterograde tract-tracing study in the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1988;270:209–42. doi: 10.1002/cne.902700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lein ES, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–76. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mechenthaler I. Galanin and the neuroendocrine axes. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2008;65:1826–35. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8157-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wynick D, et al. Galanin regulates prolactin release and lactotroph proliferation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:12671–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindeberg J, et al. Transgenic expression of Cre recombinase from the tyrosine hydroxylase locus. Genesis (New York, N.Y. : 2000) 2004;40:67–73. doi: 10.1002/gene.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caldwell HK, Lee H-J, Macbeth AH, Young WS. Vasopressin: behavioral roles of an “original” neuropeptide. Progress in neurobiology. 2008;84:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H-J, Macbeth AH, Pagani JH, Young WS. Oxytocin: the great facilitator of life. Progress in neurobiology. 2009;88:127–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Betley JN, Cao ZFH, Ritola KD, Sternson SM. Parallel, redundant circuit organization for homeostatic control of feeding behavior. Cell. 2013;155:1337–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Numan M, et al. The importance of the basolateral/basomedial amygdala for goal-directed maternal responses in postpartum rats. Behavioural brain research. 2010;214:368–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Champagne FA, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Naturally occurring variations in maternal behavior in the rat are associated with differences in estrogen-inducible central oxytocin receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:12736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221224598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Champagne FA, Weaver ICG, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Natural variations in maternal care are associated with estrogen receptor alpha expression and estrogen sensitivity in the medial preoptic area. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4720–4. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trainor BC, Marler CA. Testosterone, paternal behavior, and aggression in the monogamous California mouse (Peromyscus californicus). Hormones and behavior. 2001;40:32–42. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bridges R, DiBiase R, Loundes D, Doherty P. Prolactin stimulation of maternal behavior in female rats. Science. 1985;227:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.3969568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucas BK, Ormandy CJ, Binart N, Bridges RS, Kelly PA. Null mutation of the prolactin receptor gene produces a defect in maternal behavior. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4102–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneider JS, et al. Progesterone receptors mediate male aggression toward infants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:2951–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0130100100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pedersen C, Ascher J, Monroe Y, Prange A. Oxytocin induces maternal behavior in virgin female rats. Science. 1982;216:648–650. doi: 10.1126/science.7071605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Insel TR, Young LJ. The neurobiology of attachment. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2001;2:129–36. doi: 10.1038/35053579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Isogai Y, et al. Molecular organization of vomeronasal chemoreception. Nature. 2011;478:241–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin D, et al. Functional identification of an aggression locus in the mouse hypothalamus. Nature. 2011;470:221–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soriano P. The PDGF alpha receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development. 1997;124:2691–2700. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang CF, et al. Sexually dimorphic neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus govern mating in both sexes and aggression in males. Cell. 2013;153:896–909. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gradinaru V, Mogri M, Thompson KR, Henderson JM, Deisseroth K. Optical deconstruction of parkinsonian neural circuitry. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2009;324:354–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1167093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yizhar O, Fenno L, Davidson T. Optogenetics in neural systems. Neuron. 2011;71:9–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]