Abstract

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are considered to be the principal type-I IFN (IFN-I) source in response to viruses, whereas the contribution of conventional DCs (cDCs) has been underestimated because, on a per-cell basis, they are not considered professional IFN-I–producing cells. We have investigated their respective roles in the IFN-I response required for CTL activation. Using a nonreplicative virus, baculovirus, we show that despite the high IFN-I–producing abilities of pDCs, in vivo cDCs but not pDCs are the pivotal IFN-I producers upon viral injection, as demonstrated by selective pDC or cDC depletion. The pathway involved in the virus-triggered IFN-I response is dependent on TLR9/MyD88 in pDCs and on stimulator of IFN genes (STING) in cDCs. Importantly, STING is the key molecule for the systemic baculovirus-induced IFN-I response required for CTL priming. The supremacy of cDCs over pDCs in fostering the IFN-I response required for CTL activation was also verified in the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus model, in which IFN-β promoter stimulator 1 plays the role of STING. However, when the TLR-independent virus-triggered IFN-I production is impaired, the pDC-induced IFNs-I have a primary impact on CTL activation, as shown by the detrimental effect of pDC depletion and IFN-I signaling blockade on the residual lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus–triggered CTL response detected in IFN-β promoter stimulator 1−/− mice. Our findings reveal that cDCs play a major role in the TLR-independent virus-triggered IFN-I production required for CTL priming, whereas pDC-induced IFNs-I are dispensable but become relevant when the TLR-independent IFN-I response is impaired.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are considered to be the only APCs that are able to prime naive CD8 T cells owing to their unique ability to process and present Ag, to express costimulatory molecules, and to release soluble mediators, such as type I IFNs (IFNs-I) and other inflammatory cytokines, which are crucial for the efficient triggering of the CTL response (1, 2). With these three functions, DCs link the innate and adaptive immune systems.

Recent studies indicate that IFNs-I (mainly IFN-α and IFN-β) and IL-12 act directly on naive CD8 T cells, responding to Ag and costimulation by favoring their priming (3, 4). Stimulation of naive CD8 T cells in the absence of these signal 3 cytokines leads to proliferation but results in poor survival and the failure to develop optimal effector and memory functions (4). IFNs-I also promote CTL responses in an indirect manner by delivering maturation signals to DCs and by modulating the degree of Ag presentation and costimulation (5). Furthermore, T cell–intrinsic IFN-I signaling was reported to substitute for T cell help to CTLs (6). Although not considered specifically to be signal 3 cytokines, other cytokines, such as the common cytokine receptor γ-chain family (7) and IFN-γ (8), also have a profound effect on the CTL response.

The two main DC subsets, conventional DCs (cDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) (9), are widely considered to have highly specialized functions in the induction of a CTL response. Thus, whereas cDCs are considered to be the main APCs, pDCs are thought to be the principal sources of IFN-I production in responses to viruses (10). However, these two DC functions are not so strictly compartmentalized. Indeed, although less efficient than cDCs, TLR- or virus-licensed pDCs are able to cross-present particulate Ags and to cross-prime naive CD8 T cells (11). Moreover, there is growing evidence that pDCs are dispensable for IFN-I responses to certain viruses, suggesting that other cells must be involved in the production of IFNs-I. In this regard, it has become increasingly clear that pDCs are essential for the production of IFNs-I only during the initial stages of murine CMV and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection (12–14). Furthermore, pDCs only efficiently control the IFN-I response when low-to-intermediate doses of murine CMV are administered but are insufficient at high viral loads (13). Additionally, mice treated with the 120G8 mAb for pDC depletion had the same IFN-α levels in response to infection with the influenza virus strain X31 as did untreated mice (15). Although it has been reported that depletion of pDCs in respiratory syncytial virus infection decreases viral clearance (16), other studies suggest that IFN-I production by pDCs in respiratory syncytial virus infection may not be a critical factor (17). Moreover, Ikaros L/L mice, which lack peripheral pDCs but harbor normal numbers of cDCs, mount efficient B cell– and T cell–specific responses against the influenza virus (18). Other studies have shown that conditional deletion or Ab-mediated depletion of pDCs does not alter the induction of an antiviral CTL response (13, 19).

The role of cDCs as a source of IFNs-I against viruses could be underestimated simply because, on a per-cell basis, they are nonprofessional IFN-I–producing cells. However, cDCs are also able to produce appreciable levels of IFN-α under certain conditions (20, 21), and because they exceed pDCs in number (22), these nonprofessional IFN-α/β–producing cells may also play an important role in regulating the virus-triggered IFN-I response necessary for CTL priming. Therefore, the precise cellular source of virus-induced IFN-I production leading to CTL activation remains poorly understood. Given the importance of DCs for the priming of naive CD8 T cells, it is critical to define the relative contributions of pDCs and cDCs to the inflammatory milieu necessary for CTL activation.

To explore this we have used both replicative (lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [LCMV]) and nonreplicative (baculovirus [BV]) viruses as danger signal sources. Using the BV model we show that on a per-cell basis, pDCs are higher IFN-I producers than are cDCs upon both in vivo and in vitro virus stimulation. However, in vivo, the nonprofessional IFN-I–producing cDCs are the main source of IFN-I in response to both BV and LCMV, as shown by selective depletion of pDCs or cDCs. Thus, caution should be taken when extrapolating IFN-I–producing abilities to infer the impact of a DC subset on the in vivo virus-triggered IFN-I response. Importantly, we show that by sensing the virus through TLR-independent pathways, cDCs foster the IFN-I response required for efficient CTL priming, whereas pDCs were not required. However, in case of an impaired virus-triggered systemic IFN-I production, the pDC-induced IFN-I response has a major role on CTL priming. These results thus highlight the role played by different cellular sources of IFN-I on CTL priming and could lead to improvement in the development for IFN-α–based therapies for viral and malignant diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6J and 129Sv mice were from Charles River Laboratories (L’Arbresle, France). C57BL/6J mice lacking TLR9 (23), MyD88 (24), and IFN-β promoter stimulator 1 (IPS-1) (25) were obtained from Dr. S. Akira. Toll/IL-1R domain–containing adapter inducing IFN-β (Trif)−/− mice were obtained from Dr. S. Akira and backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background (11 backcrosses) (26). Stimulator of IFN genes (STING)−/− (C57BL/6J-Tmem173gt/J) (27) and CD11c–diphteria toxin receptor (DTR) (B6.FVB-Tg(Itgax-DTR/GFP)57Lan/J) (28) transgenic mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Animals were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions. Experiments involving animals were conducted according to institutional guidelines.

BV and LCMV

Purified Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (referred to as BV) was produced by Agate Bioservices (Bagard, France) as described previously (29). Virus stock was free of endotoxin (<0.01 endotoxin units/ml) (Limulus amebocyte lysate test, QCL-1000; BioWhittaker/Cambrex). BV particles (109 PFU/ml) were inactivated either by exposure to UV light (2 × 104 mJ/cm2) using a UV Crosslinker (Amersham Life Science) or by treatment with binary ethylenimine (BEI) or Triton X-100 as previously described (29). We detected no infectious BV after UV light or BEI treatment and only a residual titer of 7 × 103 PFU/ml after Triton X-100 treatment (29). For Benzonase treatment, BV was incubated with Benzonase (90 U/ml) (Novagen) and MgCl2 (2 mM) (2 h, 37°C). Benzonase was then inactivated with 150 mM NaCl. DNA from BV was isolated by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction from purified virions as described previously (29). The precipitated DNA was resuspended in sterile endotoxin-free water. No protein or chromosomal DNA from the insect cells was detected. LCMV Armstrong (LCMVArm) strain was grown, stored, and quantified according to published methods (30).

DC purification

For the purification of splenic cDCs and pDCs, spleens were harvested and treated for 15 min with 400 U/ml collagenase D and 50 μg/ml DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). The cell suspension was enriched in pDCs and cDCs by depleting splenocytes of B, T, and NK cells with anti-CD19, anti-CD90, and anti-DX5 mAb–coated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) on an autoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec) using the DepleteS program. The DC-enriched fraction was further purified on a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Briefly, cells were stained with anti-CD16/32 (Fc Block), anti–mouse CD19-PerCP-Cy5.5 (6D5), CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5 (145-2C11), NK1.1-PerCP-Cy5.5 (PK-136) (or pan-NK mAb [DX5] for 129sv cells), F4-80–PerCP-Cy5.5 (BM8), CD11c-PE (N418), and B220-allophycocyanin (RA3-6B2) mAbs. Contaminating CD19+, CD3+, F4-80+, and NK1.1+ (or DX5+) cells were gated out and pDCs and cDCs were sorted on the basis of CD11c and B220 expression (pDCs, CD11cintB220+; cDCs, CD11chighB220−) from DC-enriched splenocytes.

In vitro DC stimulation

Purified splenic cDCs and pDCs (105 cells/well) were cultured in complete RPMI medium in the presence of 107 PFU/ml BV, either untreated or treated with UV light, BEI, Triton X-100, or Benzonase. As control, DCs were also stimulated with a volume of Benzonase (90 U/ml) equivalent to the volume of Benzonase-treated BV used. In other cases, DCs were stimulated with 1:10 diluted supernatant from Sf9 cell culture (72 h) infected or uninfected with BV. The BV titer in the supernatant from BV-infected Sf9 cells was 107 PFU/ml. DCs were also stimulated with BV-DNA (25 μg/ml), CpGA-2216 (25 μg/ml) (Genset), or R848 (1 μg/ml) (InvivoGen). Supernatants were harvested after 36 h of culture.

Immunizations

In the BV model, mice were i.v. immunized with 109 synthetic latex beads (1 μm diameter) (Polysciences) covalently linked to the OVA257-264 synthetic peptide (BOVAp; Neosystem, Strasbourg, France), as previously described (31), either alone or in combination with BV (106 PFU). We chose BOVAp because the CTL response induced with this immunogen is fully dependent on the adjuvant signals provided by live BV or TLR ligands (29, 32). In the LCMV model, mice were first injected (i.v.) with LCMVArm (6 × 105 PFU) and 15 h later with 500 μg soluble OVA257–264 synthetic peptide (s.c.).

mAb treatments

For pDC in vivo depletion, C57BL/6J mice received two i.v. injections (24-h interval) of 500 μg/injection of functional-grade pure anti–mPDCA-1 mAbs (Miltenyi Biotec) or control rat IgG2b (eBioscience). The percentage of depletion was calculated as [(no. cells before depletion − no. cells after depletion)/cells before depletion] × 100. To block IFN-I signaling, mice were treated with 0.5 mg anti–IFN-α/β receptor (IFNAR1) Ab i.p. (clone MAR1-5A3) (Leincon Technologies) or with a mouse IgG1 isotype control (clone MOPC21) (Bio-X-Cell) on days −1 and 0 of BV injection and on days −1, 0, 1, and 2 of LCMVArm infection.

Generation of CD11c-DTR → wild-type chimeric mice and cDC depletion

CD11c-DTR → wild-type (WT) bone marrow (BM) chimeric mice were generated by irradiation of recipient mice (C57BL/6J) with a single lethal dose of 700 cGy. Recipient mice were then reconstituted with 5 × 106 donor BM cells from CD11c-DTR mice. Chimeric mice were kept on antibiotic-containing drinking water for 10 d and allowed to reconstitute for 8 wk before use. For systemic cDC depletion, CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice were i.p. injected with 100 μg DT (Calbiochem) 24 and 96 h before BV injection or 24 and 72 h before LCMVArm injection.

Cytokine detection assays

IFN-α, IFN-β, and monokine induced by IFN-γ (MIG) levels were detected using ELISA kits (IFN-α and IFN-β from PBL Biomedical Laboratories, MIG from R&D Systems). IL-12p40, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ were measured by in-house ELISA (33).

Flow cytometry analysis

Cell staining was performed with fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs in the presence of purified anti-CD16/32 mAb. Appropriate isotype controls were used to verify staining specificity. mAbs used in this study are: mAb against CD19 (6D5), CD3 (145-2C11), NK1.1 (PK-136) (or pan-NK mAb [DX5] for 129sv cells), F4-80 (BM8), CD11c (N418), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD11b (M1/70), GR1 (RB6-8C5), I-Ab (AF6-120.1), Ly6G (1A8), and CD8 (53-6-7). The number of OVA257–264-specific CTLs (OVATetr+) was determined by staining spleen cells first with H-2Kb–OVA257–264-tetramer-PE (Beckman Coulter) and then with anti–CD3-allophycocyanin and anti–CD8-FITC mAbs. Cells were acquired on either a FACSCalibur or FACSCanto II flow cytometer and analyzed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using nucleic acid purification lysis solution and a semiautomated ABI Prism 6100 Nucleic Acid PrepStation system (Applied Biosystems). Total RNA was treated with DNase prior to reverse transcriptase with Moloney murine leukemia virus in the presence of RNaseOUT (all from Invitrogen). Real-time RT-PCR was performed using the CFX96 real-time system, iQ SYBR Green mix (Bio-Rad), and specific primers for each gene: mouse IFN-α (sense, 5′-TCTYTCYTGYCTGAAGGAC-3′, antisense, 5′-CACAGRGGCTGTGTTTCTTC-3′) (degenerate primers for all mouse IFN-α subtypes) (34), mouse IFN-β (sense, 5′-ATGAGTGGTGGTTGCAGGC-3′, antisense, 5′-ACCTTTCAAATGCAGTAGATTCA-3′), mouse IL12p40 (sense, 5′-AGATGAAGGAGACAGAGGAG-3′, antisense, 5′-GGAAAAAGCCAACCAAGCAG-3′), and β-actin (sense, 5′-CGCGTCCACCCGCGAG-3′, antisense, 5′-CCTGGTGCCTAGGGCG-3′). The results were normalized to β-actin. The amount of each transcript was expressed by the formula 2∆Ct, where ∆Ct = Ct of β-actin − Ct of gene, with Ct being the point at which fluorescence rises appreciably above background fluorescence.

Statistical analysis

Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was employed for statistical analysis. A Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two experimental groups. To compare three or more experimental groups, a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test was used for nonparametric data, and a one-way ANOVA test followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test were used for parametric data. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

BV triggers innate and adaptive immune responses through TLR9/MyD88- and STING-dependent pathways

BV is an enveloped dsDNA virus that is pathogenic for insects but cannot replicate in mammals, although it can transduce them (35). We have previously established the strong adjuvant properties of BV, which promotes the in vivo maturation of DCs and the production of inflammatory mediators through mechanisms primarily mediated by IFNs-I, leading to potent humoral and CTL responses against a coadministered Ag (29). Treatment of BV with BEI, which alkylates selectively oligonucleotides (ODNs) but not proteins, strongly decreases the ability of BV to induce IFN-I and to prime CTLs, whereas Benzonase treatment, which digests soluble but not virus-packaged ODNs, does not (29). These data suggest that ODNs enclosed in the virion, presumably the viral DNA, are the pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) molecules responsible for the immunostimulatory properties of BV.

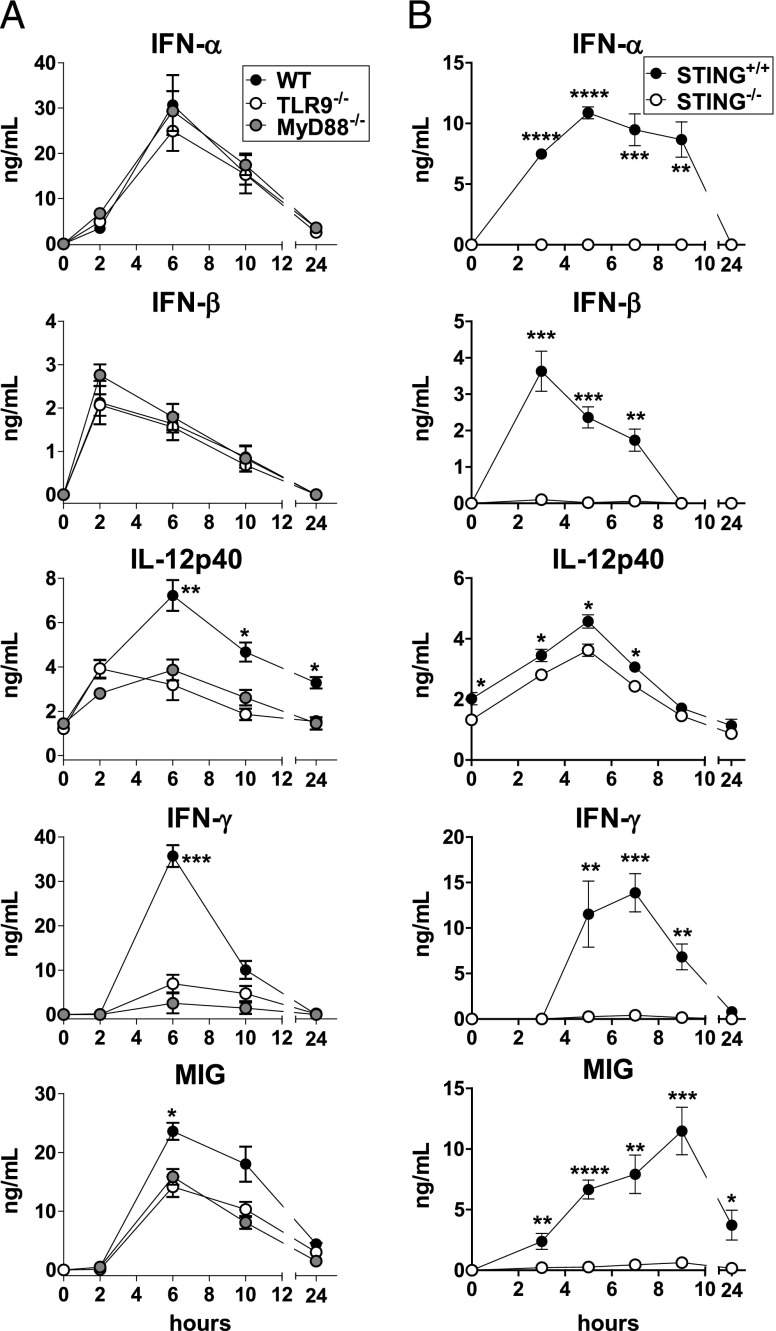

To determine the role of the TLR9/MyD88 pathway in the in vivo production of inflammatory cytokines triggered by BV, we injected WT, TLR9−/−, and MyD88−/− mice with BV. Interestingly, the production of IL-12p40, MIG, and especially IFN-γ was partially dependent on the TLR9/MyD88 pathway, in contrast to IFN-α/β production, which was totally independent of this pathway (Fig. 1A). The BV-induced cytokine response was fully independent of Trif (Supplemental Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Role of TLR9, MyD88, and STING in the systemic inflammatory cytokine triggered by BV. WT (C57BL/6), TLR9−/−, and MyD88−/− mice (A) or STING+/+ and STING−/− littermate mice (B) received a single injection of BV and their sera were titrated for the indicated cytokines by ELISA. The results are expressed as the means ± SEM for six (A) or five (B) mice per group. Data are representative (A) or are cumulative from two independent experiments (B). (A) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (WT versus TLR9−/− and WT versus MyD88−/−); (B) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p > 0.0001.

Cytosolic DNA sensors, such as DNA-dependent activator of IFN regulatory factor-1 and IFN-γ–inducible protein 16, which signal through STING, have been also involved in the sensing of DNA viruses (36). To assess the role of STING in the systemic production of inflammatory cytokines triggered by BV, we injected this virus to STING+/+ and STING−/− littermate mice. Strikingly, whereas the IL-12p40 production was fully independent of STING, the production of IFN-α/β, MIG, and IFN-γ was strictly dependent on this pathway (Fig. 1B). The fact that both TLR9/MyD88- and STING-mediated pathways were involved in the BV-induced IFN-γ and MIG responses (Fig. 1) suggests that the production of these inflammatory mediators can be positively cross-regulated by TLR9/MyD88- and STING-derived signals. Although there exist some differences between TLR9−/−, MyD88−/−, or STING−/− mice and WT mice in the percentage of certain DC and macrophage subsets (Supplemental Fig. 2A–C), these differences cannot explain the different cytokine responses induced by BV in these mouse strains. Therefore, both TLR9/MyD88- and STING-dependent pathways are involved in the BV-induced innate immune response, being the systemic production of IFNs-I to this virus totally dependent on STING.

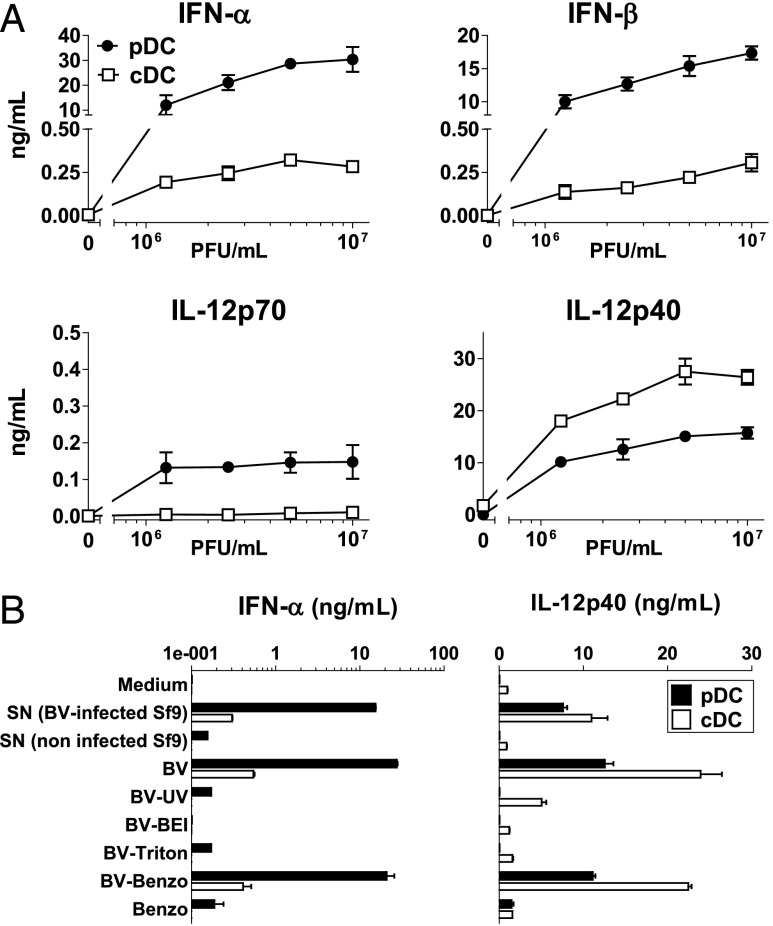

Inflammatory responses produced by cDCs and pDCs after in vitro stimulation with BV

To compare the ability of cDCs and pDCs to secrete inflammatory cytokines after stimulation with BV, we cultured equal numbers of cDCs and pDCs isolated from the spleens of 129Sv mice with BV. 129Sv mice were chosen owing to their high pDC frequency in the spleen (22). Upon stimulation with BV, pDCs secreted much higher amounts of IFN-α/β and IL-12p70 than did cDCs, whereas cDCs were higher producers of IL-12p40 than were pDCs (Fig. 2A). The induction of this cytokine profile was due to the virus and not to any possible Sf9-derived contaminants because only the supernatant from BV-infected Sf9 cells, but not that from uninfected cells, was able to stimulate the production of IFN-α and IL-12p40 (Fig. 2B). Treatment with UV light, BEI, or Triton X-100 impaired the capacity of BV to stimulate the production of IFNs-I and IL-12p40 by pDCs and cDCs, whereas Benzonase treatment did not (Fig. 2B), suggesting that both the infectivity of the viral particle and its encapsulated nucleic acids are critical for the BV-induced stimulation of pDCs and cDCs.

FIGURE 2.

In vitro inflammatory cytokines produced by pDCs and cDCs after stimulation with BV. (A) FACS-sorted splenic cDCs and pDCs from 129Sv mice were stimulated with BV, and the cytokine production was determined in culture supernatant by ELISA. (B) pDCs and cDCs were stimulated with supernatants (SN) (diluted 1:10) from Sf9 cells infected or not with BV, or with BV (107 PFU/ml) either untreated or treated with UV light (BV-ultraviolet), BEI (BV-BEI), Triton X-100 (BV-Triton), or Benzonase (BV-Benzo). As a control, cells were also cultured with a volume of Benzonase (Benzo) equivalent to the volume of Benzonase-treated BV. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

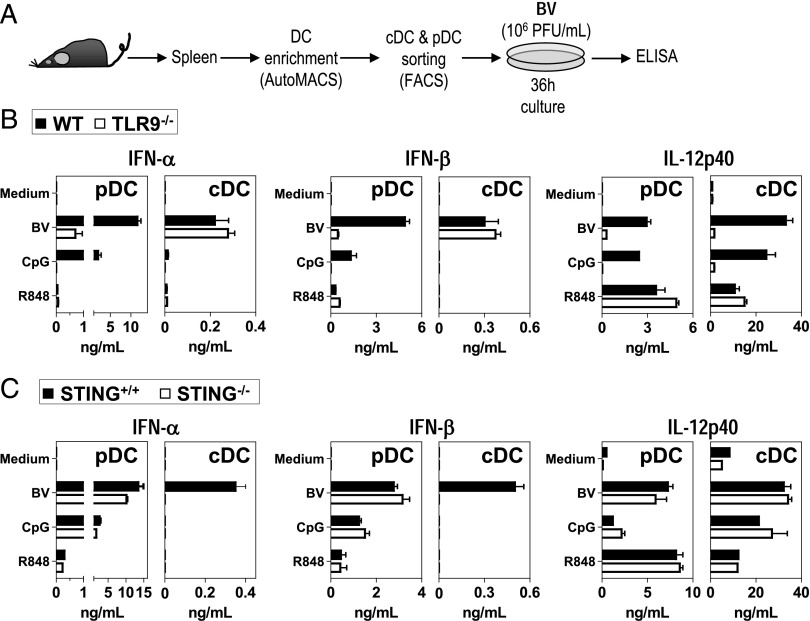

Role of TLR9/MyD88 and STING in the BV-triggered stimulation of cDCs and pDCs

We then analyzed the PAMP receptors used by cDCs and pDCs to sense BV. BM-derived or splenic cDCs and pDCs from TLR9−/−, MyD88−/−, TRIF−/−, and STING−/− mice, as well as from their respective WT mice, were stimulated with BV and analyzed for cytokine production. Independently of whether they were splenic or BM-derived, the highest levels of IFN-α/β and IL-12p40 were produced by pDCs and cDCs, respectively (Fig. 3, Supplemental Figs. 1B, 3A). For both DC subsets, the BV-induced production of IFN-α and IL-12p40 was independent of Trif (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Interestingly, whereas the BV-triggered IFN-α/β production was highly dependent on TLR9/MyD88 signaling in pDCs (Fig. 3B, Supplemental Fig. 3A), it was strictly dependent on STING in cDCs (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the BV-induced IL-12p40 production was dependent on TLR9/MyD88 signaling in both cDCs and pDCs (Fig. 3A, Supplemental Fig. 3A). Therefore, the involvement of TLR9/MyD88 and STING in the BV-triggered innate response is cytokine and DC type-specific.

FIGURE 3.

Role of TLR9 and STING in the in vitro production of inflammatory cytokines by pDCs and cDCs in response to BV. (A) Experiment schedule. FACS-sorted splenic pDCs and cDCs from WT and TLR9−/− mice (B) or from STING+/+ and STING−/− mice (C) were stimulated with BV (107 PFU/ml). As control we also stimulated cells with CpGA-2216 (25 μg/ml) or R848 (1 μg/ml) (B and C). Cytokine production was determined in culture supernatants by ELISA. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Although less efficiently than intact virus, purified BV-DNA also triggered the production of IL-12p40 in both cDCs and pDCs, as well as the production of IFN-α/β in pDCs, and this response was TLR9/MyD88-dependent (Supplemental Fig. 3A). However, BV-DNA hardly stimulated the production of IFN-α/β in cDCs. This finding could be due to a less efficient internalization of the free viral DNA in comparison with that of the virus-packaged DNA. Indeed, BV-induced production of IFN-α/β by splenic cDCs was abrogated by treatment with UV light, Triton X-100, and BEI (Supplemental Fig. 3B), suggesting that the way in which the encapsulated nucleic acids are internalized is crucial for the BV-triggered STING-dependent production of IFNs-I by cDCs.

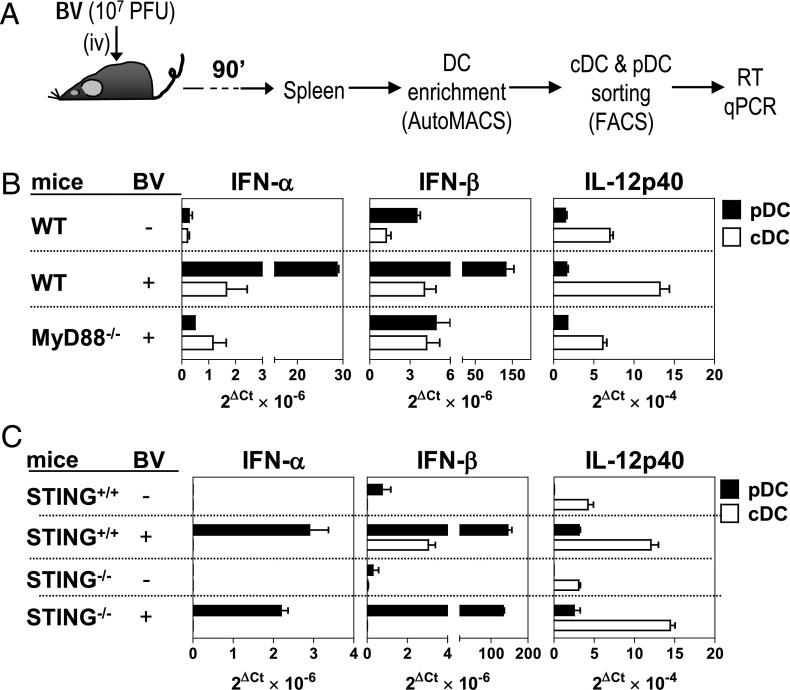

Role of the TLR9/MyD88 pathway in the in vivo BV-induced cytokine production

To assess the respective roles of cDCs and pDCs, as well as of the TLR9/MyD88- and STING-mediated pathways, in the in vivo BV-triggered cytokine response, we analyzed the expression of IFN-α/β and IL-12p40 in splenic cDCs and pDCs isolated from BV-injected mice. As depicted in Supplemental Fig. 3C, expression of IFN-α and IL-12p40 by intracellular staining was only detected in pDCs or cDCs, respectively. In every case, this expression was dependent on TLR9 (Supplemental Fig. 3C) and MyD88 (data not shown). Next, we assessed the expression of IFN-α/β and IL-12p40 by quantitative RT-PCR in splenic cDCs and pDCs from WT, MyD88−/−, and STING−/− mice that were previously injected with BV (Fig. 4A). Accordingly to the results obtained in vitro, we found that pDCs and cDCs were, respectively, the highest producers of IFN-α/β and of IL-12p40 in response to BV infection (Fig. 4). The expression of IFN-α/β in pDCs and the production of IL-12p40 in cDCs were dependent on MyD88 (Fig. 4B) and independent of STING (Fig. 4C). Low but detectable levels of IFN-α and IFN-β in response to BV were detected in WT cDCs by quantitative RT-PCR, which were similar to those of MyD88−/− cDCs (Fig. 4B). We could not detect IFN-α expression by cDCs in either STING+/+ or in STING−/− littermate mice (Fig. 4C). However, a BV-triggered IFN-β response was clearly detectable in STING+/+ mice, which was totally abrogated in STING−/− mice (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the involvement of the TLR9/MyD88- and STING-mediated pathways in the in vivo production of cytokines by BV is also DC- and cytokine type–specific. More importantly, on a per-cell basis, pDCs are the main in vivo producers of IFN-α/β, whereas cDCs are the main in vivo IL-12p40 triggers.

FIGURE 4.

Role of MyD88 and STING in the in vivo production of inflammatory cytokines by pDCs and cDCs in response to BV. (A) Experiment schedule. Mice were left untreated or were injected (i.v.) with BV (107 PFU) and 90 min later spleens were harvested. Splenic cDCs and pDCs were FACS-sorted from a DC-enriched splenocyte preparation and processed for RNA isolation. (B and C). Expression of IFN-α, IFN-β, and IL-12p40 mRNA in FACS-sorted splenic pDCs and cDCs from WT and MyD88−/− mice (B) or from STING+/+ and STING−/− littermate mice (C) analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

In vivo cDCs are responsible for the systemic inflammatory response triggered by BV

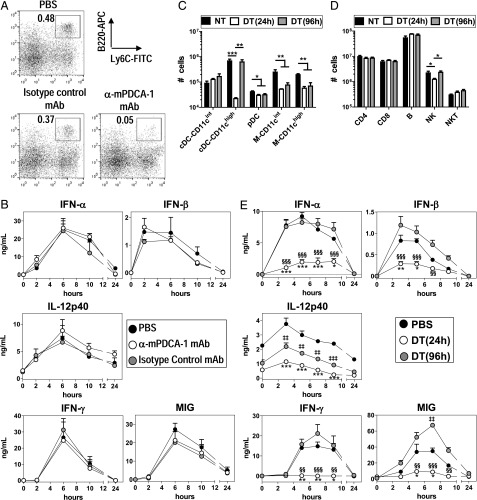

The predominance of cDCs in different tissues (22) (Supplemental Fig. 2D) may strongly affect the importance of these cells in the systemic inflammatory response induced by BV. To evaluate the participation of pDCs in the systemic response, we depleted these cells using an anti–mPDCA-1 mAb (12) before BV administration. The efficient pDC depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, pDC depletion did not affect the systemic IFN-I response induced by BV, nor the level of expression of IL-12p40, IFN-γ, or MIG.

FIGURE 5.

cDCs, but not pDCs, are required for the in vivo inflammatory response promoted by BV. (A) Percentage of pDCs (CD19−NK1.1−CD11c+B220+Ly6C+) in total splenocytes 24 h after PBS, anti–mPDCA-1 mAbs, or rat IgG2b delivery. (B) Seric levels of cytokines triggered by BV in C57BL/6J mice that were previously treated with PBS, anti–mPDCA-1 mAbs, or rat IgG2b. (C and D) Absolute number of different subsets of DCs, macrophages (C), and lymphocytes (D) in total splenocytes from CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice 24 and 96 h after PBS or DT administration. Cells were gated as indicated in Supplemental Fig. 2A, and phenotypic features are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2B. M, macrophages. Data were compiled from two independent experiments (n = 6). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (E) Seric levels of cytokines triggered by BV in CD11c-DTR → WT BM chimeric mice that were previously treated with PBS or DT (24 or 96 h before virus injection). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (NT versus DT, 24 h); $$p < 0.01, $$$p < 0.001 (NT versus DT, 96 h); ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 (DT [24 h] versus DT [96 h]). (B and E) Results are expressed as the means ± SEM and represent cumulative data from four (B) and six (E) mice tested in two independent experiments.

To examine whether cDCs played a role in the systemic inflammatory response triggered by BV, we used transgenic mice carrying the DTR linked to the CD11c promoter (CD11c-DTR mice) (28). Because nonhematopoietic cells may also express the CD11c-DTR transgene (28), we produced CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice in which only the hematopoietic compartment is derived from CD11c-DTR mice. Administration of DT to these mice 24 h before BV injection results in depletion of CD11c+ cells in the spleen (Fig. 5C, 5D). The most affected populations were CD11chigh cDCs (depletion >95%), whereas other CD11c+ cells were depleted to a lesser extent (macrophages, between 60 and 80%; NK cells, 50%; pDCs, 40%) (Fig. 5C, 5D). CD11cint cDCs and CD11c− cells (such as T and B lymphocytes and NKT cells) were not affected by this treatment. Administration of DT to CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice 24 h before BV injection strongly reduced the serum levels of IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and MIG (Fig. 5E). Similar results were obtained when we used CD11c-DTR mice instead of CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice (data not shown).

Interestingly, the total number of CD11chigh cDCs returned to normal levels after 96 h of DT treatment, whereas pDCs and macrophages remained depleted (20 and 65–70%, respectively) (Fig. 5C, 5D). This property is commonly used to discern the role of cDCs and/or macrophages in different biological process using CD11c-DTR mice (37, 38). As depicted in Fig. 5E, CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice treated with DT 96 h before BV injection produced systemic levels of IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ comparable to those in nontreated mice, although IFN-β and IFN-γ values were slightly higher in the former group. Additionally, MIG levels reached significantly higher values in the group treated with DT 96 h compared with nontreated mice. This effect could be due to a higher capacity of the newly differentiated cDCs to produce inflammatory mediators or to a release of the break that controls cDC-mediated cytokine response. Interestingly, the IL-12p40 response was only partially restored in mice treated with DT 96 h before BV infection, suggesting that other cells, likely macrophages, are involved in the BV-triggered IL-12p40 response. Finally, because the number of NK cells was restored 96 h after DT treatment, we cannot rule out the possibility that NK cells might also contribute to the BV-triggered IFN-γ production.

Taken together, these data indicate that despite their lower potency on a per-cell basis, cDCs play an essential role in the in vivo inflammatory response triggered by BV, including IFN-α/β production.

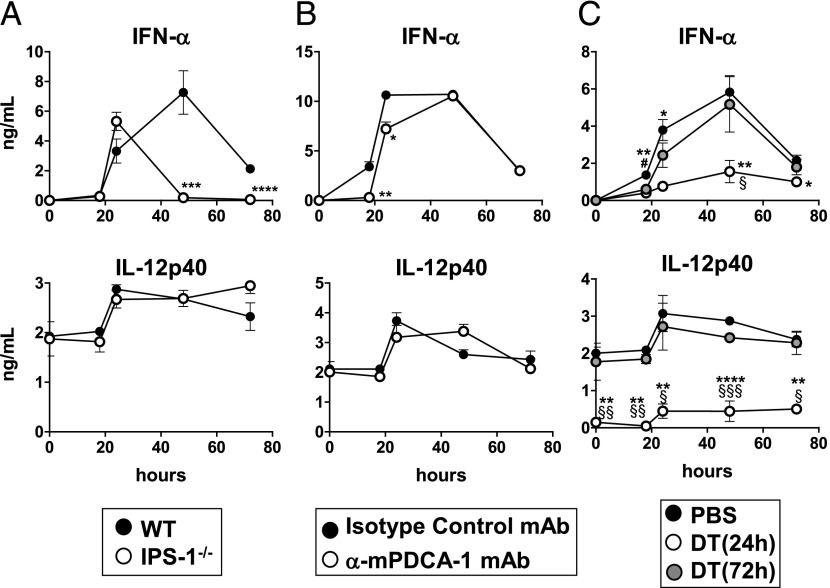

In vivo cDCs are responsible for the systemic inflammatory response triggered by LCMV

To assess whether in vivo cDCs, in response to a virus that infects and replicates in mice, also produce IFNs-I more efficiently than do pDCs, we selected the LCMVArm virus, which elicits an acute infection in mice (39). Although pDCs have been shown to detect LCMV through TLR7-dependent mechanisms (40), they have an early and limited impact on the amplitude and duration of IFN-α responses to LCMV, contributing only to the IFN-I response detected 18–24 h postinfection (40). Rather, still unidentified cells, activated by a melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA-5)–dependent pathway, seem to be the key source of the LCMV-induced production of IFNs-I (40). We have confirmed these data using mice deficient for IPS-1, the adaptor molecule triggering retinoic acid–inducible gene-I– and MDA-5–mediated IFN-I induction (41) and by depleting pDCs with anti–PDCA-1 mAb (Fig. 6A, 6B). Note that the systemic production of IL-12p40 in response to LCMVArm was independent of both IPS-1 and pDCs (Fig. 6A, 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Role of IPS-1, pDCs, and cDCs in the systemic IFN-I response elicited by LCMV. (A) C57BL/6 (WT) and IPS-1−/− mice were infected (i.v.) with LCMVArm. (B) C57BL/6 mice received two i.v. injections (24-h interval) of anti–mPDCA-1 mAbs (or control rat IgG2b). (C) CD11c-DTR → WT BM chimeric mice received PBS or DT (i.p.). (B and C) Twenty-four hours after the first mAb injection (B) or 24 or 72 h after the DT treatment (C) mice were infected (i.v.) with LCMVArm. (A–C) At the indicated times, the levels of IFN-α and IL-12p40 were determined in the sera by ELISA. The results are expressed as the means ± SEM and represent the cumulative data from six mice tested in two independent experiments. (A and B) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (C) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 (NT versus DT, 24h); #p < 0.05 (NT verus DT, 72 h); §p < 0.05, §§p < 0.01, §§§p < 0.001 (DT [24 h] versus DT [72 h]).

To evaluate the contribution of cDCs to the IFN-I response triggered by LCMVArm, CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice were injected with DT 24 and 72 h before virus injection (48 and 96 h before the peak of the IFN-α response, respectively). As shown in Fig. 6C, the administration of DT 24 h before virus injection strongly reduced the seric levels of IFN-α and IL-12p40, whereas mice treated with DT 72 h before LCMVArm infection produced normal levels of these cytokines. These data indicate that, as demonstrated for BV, cDCs play an essential role in the in vivo production of IFN-α, as well as of IL-12, in response to LCMV.

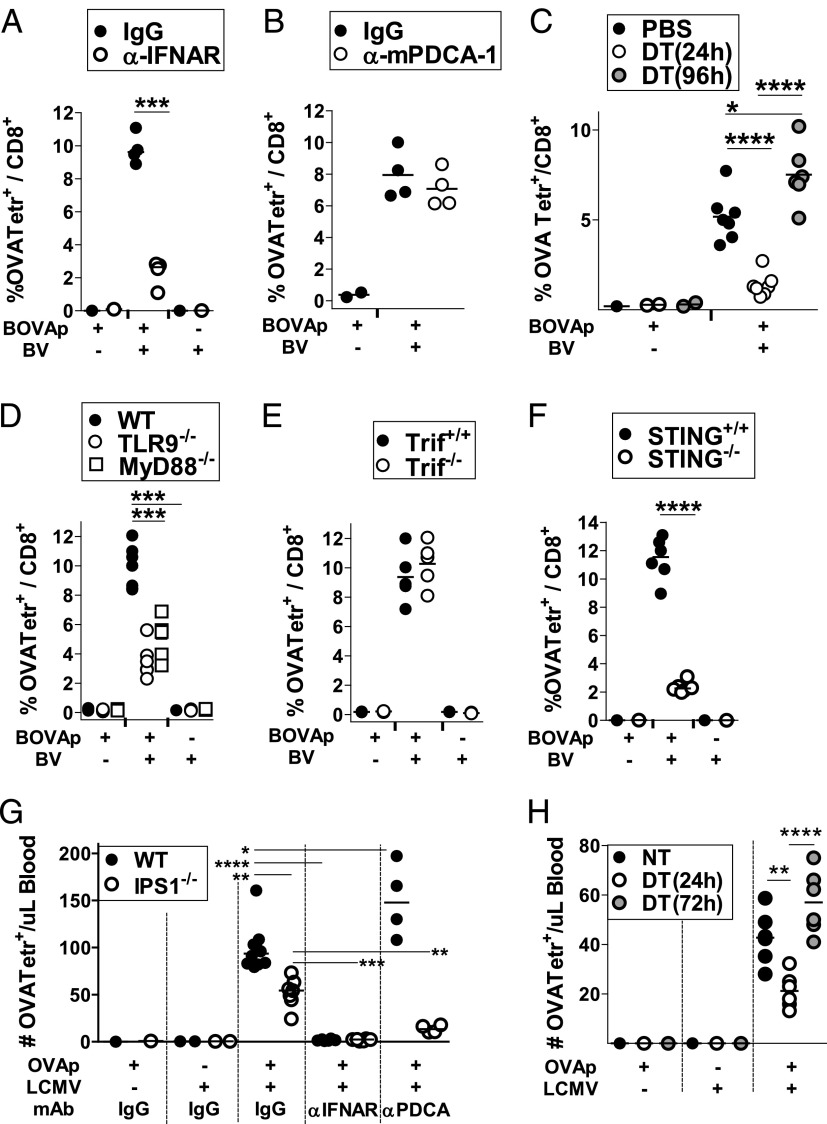

TLR-independent pathways control the systemic virus–triggered IFNs-I response required for CTL activation

Using IFNAR-deficient mice, we have previously shown that BV triggers a strong CTL response through mechanisms mediated primarily by IFN-α/β (29). In good agreement with these previous results, C57BL/6 mice treated with anti-IFNAR neutralizing mAbs and immunized with BOVAp in combination with BV elicited a much weaker CTL response than did those treated with a control Ab (Fig. 7A). To assess the contribution of pDCs to the CTL response triggered by BV, pDC-depleted mice were immunized with BOVAp in combination with BV. The percentage of OVA-specific CTLs was not affected by pDC depletion (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the CTL response induced by BV in CD11cDTR → BL6 chimeric mice was almost fully abolished by DT treatment 24 h before virus injection (Fig. 7C). This response, however, was rapidly restored, reaching levels even higher than those observed in nontreated mice when DT was given 96 h before BV.

FIGURE 7.

TLR-independent virus-triggered IFN-I production is the key IFN-I source for CTL priming. (A and B) C57BL/6 mice were left untreated or received two i.v. injections (24-h interval) of anti-IFNAR mAbs (or control mouse IgG1) (A) or anti–mPDCA-1 mAbs (or control rat IgG2b) (B). (C) CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice were left untreated or treated with a single injection of DT. Twenty-four and 96 h after the DT treatment mice were immunized with BOVAp alone or together with BV. (D–F) WT, TLR9−/−, and MyD88−/− mice (D) or Trif+/+ and Trif−/− (E) or STING+/+ and STING−/− littermate mice (F) were immunized with BOVAp alone or together with BV. (A–F) The percentage of OVA-specific CD8 T cells/total CD8 T cell was analyzed at day 7 in the spleen by H-2Kb-OVA257–264-tetramer-PE staining. The results shown are cumulative data from four (A and B) or at least five (C–F) mice tested in two independent experiments. Data from control mice immunized with BOVAp or BV alone are also shown. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (G) WT and IPS-1−/− mice received four i.v. injections (24-h interval) of anti-IFNAR mAbs (or control mouse IgG1) or two i.v. injections (24-h interval) of anti–mPDCA-1 mAbs (or control rat IgG2b). (H) CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice were left untreated or treated with a single injection of DT. (G and H) Twenty-four hours after either the first injection of mAb (G) or DT treatment (H), and 72 h after the DT treatment (H), mice were infected (i.v.) with LCMVArm and 15 h later they were immunized (s.c.) with OVAp. The number per microliter of blood of OVA-specific CD8 T cells was determined at day 7 by H-2Kb-OVA257–264-tetramer-PE staining. The results shown are cumulative data from at least four mice tested in two independent experiments. Data from control groups injected with OVAp or LCMVArm alone are also shown. (G) Because mice treated with control mouse IgG1 or rat IgG2a give comparable results, they were plotted together under the IgG alias. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

cDCs are both the main APCs for naive CD8 T cells and the main source of IFN-I after immunization in the presence of BV. Thus, to clarify their role in the induction of CTL responses, we took advantage of the fact that the BV-triggered IFN-I production by cDCs is strictly dependent on STING, in contrast to the production by pDCs, which is mediated by TLR9/MyD88. As shown in Fig. 7D, a smaller but still significant CTL response was observed in TLR9−/− and MyD88−/− mice, in comparison with WT mice, upon immunization with BOVAp plus BV. Trif was not required for the BV adjuvanticity (Fig. 7E). In contrast, in the absence of STING, the BV-triggered CTL response was markedly reduced (Fig. 7F). Because STING−/− mice have been shown to generate normal CTL responses following Listeria monocytogenes reinfection (42), this lack of CTL response was not due to an intrinsic defect of these mice. Given the impaired BV-triggered IFN-I (Fig. 1B) and CTL (Fig. 7F) responses in STING−/− mice, together with the strict dependence of STING on the cDC-induced IFN-I production to BV (Figs. 3C, 4C) and the markedly reduced IFN-I response prompted by BV in cDC-ablated mice (Fig. 5E), our data strongly suggest that cDCs lead to the systemic IFNs-I production required for the BV-induced CTL response.

We have also assessed the contribution of different IFN-I cellular sources and signaling pathways on the CTL response induced by LCMVArm. To skip the effect of viral replication and Ag expression on CTL priming, we analyzed at day 7 of virus injection the CTL response induced against a nonrelated epitope, OVA257–264, administered as soluble peptide. The immunodominance of the LCMV epitopes was overcome by injecting a high dose of soluble OVA257–264 peptide (OVAp) (500 μg/mouse). It is already known that LCMVArm elicits a strong CTL response through mechanisms highly dependent on IFN-I (6). We have confirmed this result using an anti-IFNAR blocking mAb (Fig. 7G). Additionally, as reported for LCMV clone 13 (40), pDC depletion by anti–PDCA-1 mAbs had no significant effect on the CTL response elicited by LCMVArm (Fig. 7G). Interestingly, IPS-1 deficiency impaired the CTL response triggered by LCMVArm against OVAp (Fig. 7G), confirming previous data obtained in MDA-5−/− mice (40). These data, together with the findings that the LCMV-elicited IFN-I response was drastically reduced in the CD11c-DTR system (Fig. 6C) and in the absence of IPS-1 (Fig. 6A), point out cDCs as the most likely IFN-I cellular source for the LCMV-triggered CTL response.

Importantly, the residual CTL response detected in IPS-1−/− mice was strictly dependent on IFN-I-signaling and pDCs (Fig. 7G). These data stand for an underlying role of the pDC-induced IFN-I production in CTL activation, a function that becomes important only when the TLR-independent IFN-I response decline.

As observed in the BV viral model, the OVA-specific CTL response induced by LCMV was also impaired by DT administration 24 h before virus injection (Fig. 7H).

Discussion

Although it is well accepted that IFNs-I, either alone or in combination with other signal 3 cytokines, are critical for the generation of CTL responses (3, 4, 43), the roles played by the diversity of IFN-I cellular sources as well as by the various signaling pathways involved remain poorly understood. Identifying the cells and pathways that shape the inflammatory milieu required for CTL priming would facilitate the development of improved vaccines against intracellular pathogens and tumors.

Through its capacity to activate both pDCs and cDCs by different pathways, BV constitutes an interesting nonreplicative viral model to evaluate the impact on CTL priming of various pathways and cellular sources of inflammatory cytokines, independently of viral replication and Ag expression. Indeed, BV is recognized by TLR9/MyD88- and STING-dependent pathways. Interestingly, whereas the in vivo BV-triggered production of IL-12p40 is partially dependent on TLR9/MyD88 (the present study and Ref. 44), the in vivo IFN-I production to BV is strictly STING-dependent. Moreover, the involvement of TLR9/MyD88- and STING-dependent pathways in sensing BV is not only cytokine type–specific but also DC subset-specific. In this regard we show that the BV-triggered production of IL-12p40 is dependent on TLR9/MyD88 in both pDCs and cDCs, whereas the production of IFN-I is TLR9/MyD88-dependent in pDCs and STING-dependent in cDCs. The cytokine type–specific involvement of the TLR9/MyD88 pathway depending on the DC subset may be explained by the fact that in cDCs, unlike in pDCs, TLR9 triggering leads to the activation of NF-κB, which is necessary to induce inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, but not to the activation of IFN regulatory factor-7, which is required for IFN-I production (45). The precise mechanisms by which BV induces IFNs-I in a STING-dependent manner remain unknown. The activating ligands for STING are cytosolic cyclic dinucleotides produced by bacteria or by cellular cGMP synthase, a host cell nucleotidyl transferase that directly binds dsDNA, and in response synthesizes cGMP. Our in vitro and in vivo data using BV treated with BEI or Benzonase strongly suggest that viral DNA is the decisive PAMP for the BV-induced STING-dependent production of IFNs-I (the present study and Ref. 29), and STING-triggering should likely occur through cGMP synthesis.

Owing to their ability to produce high levels of IFN-I per cell, pDCs are usually considered to be the main IFN-I–producing cells during viral infection. However, growing evidence suggests that the contribution of pDCs to the virus-triggered IFN-I response is quite limited and time-dependent, whereas the participation of nonprofessional IFN-I producing cells through TLR-independent pathways is higher than anticipated (13–15, 21, 40, 46). This discrepancy is explained by the frequent use of in vitro or ex vivo assays comparing the IFN-I–producing abilities of isolated pDCs and cDCs to infer the contribution of these cells to the in vivo IFN-I response to viruses. Indeed, our in vitro and ex vivo studies clearly show that BV triggers the production of IFN-I in both pDCs and cDCs and that pDCs are far more efficient than cDCs at producing IFN-I on a per-cell basis. However, despite this well-established property, pDCs were highly dispensable for the in vivo IFN-I response to BV, as was shown by depleting these cells with anti–mPDCA-1 mAbs. pDC depletion has only an early and limited influence on the IFN-I responses to LCMV, confirming previous data using toxin receptor–based pDC-ablated mice (40). Additionally, using IPS-1−/− mice we have confirmed that the MDA-5/IPS-1 signaling pathway has a major role in the IFN-I response to LCMV. Therefore, other cells, through TLR-independent pathways, are responsible for the in vivo IFNs-I production in response to BV and LCMV.

Unlike pDCs, which produce IFNs-I mainly upon TLR7/9 stimulation, IFNs-I are induced in most cells by TLR-independent pathways. Among them, cDCs have been reported to act as specialized IFN-I–producing cells in certain viral infections (21, 46). CD11c-DTR transgenic mice are very useful to assess the contribution of cDCs in the systemic virus–induced IFN-I response. In these mice, 18 h after a single DT injection, virtually all CD11chigh cDCs are depleted from the spleen and reached comparable numbers to those in nondepleted mice after 96 h of DT treatment (the present study and Ref. 38). DT causes cell death by apoptosis (47), which does not induce inflammatory immune responses (48). Other CD11c+ cells are depleted by DT treatment, such as NK cells, pDCs, and macrophages. However, the extent of their depletion is less than for CD11chigh cDCs, and, in the case of pDCs and macrophages, the depletion persists beyond 96 h of DT injection. Our findings that the systemic IFN-I production following BV and LCMV injection was abolished in CD11c-DTR → BL6 chimeric mice treated with DT 24 h before virus injection, but was restored to normal levels when DT was given 72–96 h before virus, strongly support the conclusion that CD11chigh cDCs, but not other CD11c+ cells, are the major effectors of the IFN-I production in response to BV and LCMV.

cDCs have also been identified as the main in vivo IFN-I–producing cells against adenovirus (46). Several factors may account for cDC superiority over pDCs in the systemic virus-triggered IFN-I response. Numeric superiority of cDCs over pDCs may be a crucial factor. In fact, total cDC numbers in the body by far exceed the number of pDCs (the ratio of pDCs to cDCs in an average mouse spleen is ∼1:10) (the present study and Ref. 22). Additionally, other factors such as virus-induced selective recruitment of cDCs and/or higher in vivo virus tropism for cDCs may also explain the difference.

Importantly, by depleting pDCs in WT mice we show that pDCs are dispensable for the BV- and LCMV-triggered CTL priming, confirming previous data using toxin receptor-based pDC-ablated mice and both acute (LCMVArm) and chronic (LCMV clone 13) strains (40). Rather, the virus-induced TLR-independent production of IFNs-I by cDCs seems to be the key IFN-I source for the CTL response triggered by BV and LCMV, as evidenced by the impaired virus-triggered IFN-I and CTL responses in STING−/− and IPS-1−/− mice, respectively, together with the markedly reduced IFN-I induction by these viruses in cDC-ablated mice.

Interestingly, in the absence of high systemic levels of IFNs-I, as happens in IPS-I−/− mice infected with LCMV, a significant CTL response could still be detected. Wang et al. (40) have recently shown that the residual LCMV-triggered CTL response detected in the absence of MDA-5 signaling was not dependent on IL-12, the other major signal 3 cytokine for CTLs. In the present study, we show that pDC depletion and IFN-I signaling blockade abolish the remaining CTL response induced by LCMVArm in IPS-1−/− mice. Our findings reveal an underlying role for the pDC-induced IFN-I response in effectively priming CTLs, which becomes relevant only when the systemic and TLR-independent virus-triggered IFN-I production is spoiled.

Finally, the mechanism behind the detrimental effect of TLR9/MyD88 deficiency on the BV-triggered CTL priming still remains to be clarified. Given the fact that IFNAR blockade does not totally abrogate the CTL response prompted by BV (Ref. 29 and the present study), mechanisms independent of IFNs-I, such as IL-12 and/or BV-specific CD4 T cell help, could also be involved. Finally, because it has been described that TLR9 and MyD88 also exert direct effects on T cell activation (49, 50), we cannot rule out the possibility that the diminished CTL response triggered by BV in TLR9−/− and MyD88−/− mice would be due to an intrinsic effect of these molecules on T cells.

In conclusion, we show that in vivo, nonprofessional IFN-I–producing cDCs outpace pDCs and dominate systemic virus–triggered IFN-I production by sensing the virus through TLR-independent pathways. Furthermore, the TLR-independent IFN-I response is the key source of IFNs-I required for CTL activation. Interestingly, when the virus-triggered TLR-independent IFN-I production is impaired, the pDC-induced IFN-I response becomes relevant for CTL priming. Viruses often target the TLR-independent pathways of IFN-I induction to replicate and survive in the host. The effect of pDC-induced TLR-dependent IFN-I response on CTL priming might be an important alternative mechanism to avoid virus persistence when the TLR-independent IFN-I production is defective. These findings could help the development of new adjuvant formulations able to foster the appropriate IFN-I response needed for efficient CTL priming by targeting different PAMP receptors and different DC types to enhance the efficacy of vaccines and immunotherapeutic strategies against viral infections and tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Asselin-Paturel for providing the IFN-α ICS protocol, Dr. P. Vieira (Institute Pasteur) and Dr. G. Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza (Center for Applied Medical Research) for providing TLR9−/− and STING−/− mice, respectively, and the European Virus Archive project and Dr. D. Pinschewer (University of Geneva) for providing LCMVArm.

This work was supported by grants from the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (Equipe Labellisée 2014), the Institut National du Cancer/Cancéropole Ile de France, the Banque Privée Européenne, the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under Grant 280873 (Advanced Immunization Technologies), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria Grant PI11/02327, and by the Unión Temporal de Empresas project Centro de Investigación Médica Aplicada. S.H.-S. was supported by the Asociación Española Contra el Cancer and by Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia Grant RYC-2007-00928.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

- BEI

- binary ethylenimine

- BM

- bone marrow

- BOVAp

- beads linked to the OVA257–264 peptide

- BV

- baculovirus

- cDC

- conventional DC

- DC

- dendritic cell

- DT

- diphteria toxin

- DTR

- diphtheria toxin receptor

- IFNAR

- IFN-α/β receptor

- IFN-I

- type I IFN

- IPS-1

- IFN-β promoter stimulator 1

- LCMV

- lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

- LCMVArm

- LCMV Armstrong strain

- MDA-5

- melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5

- MIG

- monokine induced by IFN-γ

- ODN

- oligonucleotide

- OVAp

- OVA257–264 peptide

- PAMP

- pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- pDC

- plasmacytoid DC

- STING

- stimulator of IFN genes

- TRIF

- Toll/IL-1R domain–containing adapter inducing IFN-β

- WT

- wild-type.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Reis e Sousa C. 2004. Activation of dendritic cells: translating innate into adaptive immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16: 21–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee H. K., Iwasaki A.. 2007. Innate control of adaptive immunity: dendritic cells and beyond. Semin. Immunol. 19: 48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolumam G. A., Thomas S., Thompson L. J., Sprent J., Murali-Krishna K.. 2005. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 202: 637–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mescher M. F., Curtsinger J. M., Agarwal P., Casey K. A., Gerner M., Hammerbeck C. D., Popescu F., Xiao Z.. 2006. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol. Rev. 211: 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santini S. M., Di Pucchio T., Lapenta C., Parlato S., Logozzi M., Belardelli F.. 2002. The natural alliance between type I interferon and dendritic cells and its role in linking innate and adaptive immunity. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 22: 1071–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiesel M., Kratky W., Oxenius A.. 2011. Type I IFN substitutes for T cell help during viral infections. J. Immunol. 186: 754–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obar J. J., Lefrançois L.. 2010. Early events governing memory CD8+ T-cell differentiation. Int. Immunol. 22: 619–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitmire J. K., Tan J. T., Whitton J. L.. 2005. Interferon-gamma acts directly on CD8+ T cells to increase their abundance during virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 201: 1053–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shortman K., Liu Y. J.. 2002. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2: 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y. J. 2005. IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23: 275–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouriès J., Moron G., Schlecht G., Escriou N., Dadaglio G., Leclerc C.. 2008. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells efficiently cross-prime naive T cells in vivo after TLR activation. Blood 112: 3713–3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krug A., French A. R., Barchet W., Fischer J. A., Dzionek A., Pingel J. T., Orihuela M. M., Akira S., Yokoyama W. M., Colonna M.. 2004. TLR9-dependent recognition of MCMV by IPC and DC generates coordinated cytokine responses that activate antiviral NK cell function. Immunity 21: 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swiecki M., Gilfillan S., Vermi W., Wang Y., Colonna M.. 2010. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell ablation impacts early interferon responses and antiviral NK and CD8+ T cell accrual. Immunity 33: 955–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delale T., Paquin A., Asselin-Paturel C., Dalod M., Brizard G., Bates E. E., Kastner P., Chan S., Akira S., Vicari A., et al. 2005. MyD88-dependent and -independent murine cytomegalovirus sensing for IFN-α release and initiation of immune responses in vivo. J. Immunol. 175: 6723–6732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GeurtsvanKessel C. H., Willart M. A., van Rijt L. S., Muskens F., Kool M., Baas C., Thielemans K., Bennett C., Clausen B. E., Hoogsteden H. C., et al. 2008. Clearance of influenza virus from the lung depends on migratory langerin+CD11b− but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 205: 1621–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H., Peters N., Schwarze J.. 2006. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells limit viral replication, pulmonary inflammation, and airway hyperresponsiveness in respiratory syncytial virus infection. J. Immunol. 177: 6263–6270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jewell N. A., Vaghefi N., Mertz S. E., Akter P., Peebles R. S., Jr., Bakaletz L. O., Durbin R. K., Flaño E., Durbin J. E.. 2007. Differential type I interferon induction by respiratory syncytial virus and influenza a virus in vivo. J. Virol. 81: 9790–9800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf A. I., Buehler D., Hensley S. E., Cavanagh L. L., Wherry E. J., Kastner P., Chan S., Weninger W.. 2009. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are dispensable during primary influenza virus infection. J. Immunol. 182: 871–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cervantes-Barragan L., Lewis K. L., Firner S., Thiel V., Hugues S., Reith W., Ludewig B., Reizis B.. 2012. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control T-cell response to chronic viral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 3012–3017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda K., Ohba Y., Yanai H., Negishi H., Mizutani T., Takaoka A., Taya C., Taniguchi T.. 2005. Spatiotemporal regulation of MyD88-IRF-7 signalling for robust type-I interferon induction. Nature 434: 1035–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diebold S. S., Montoya M., Unger H., Alexopoulou L., Roy P., Haswell L. E., Al-Shamkhani A., Flavell R., Borrow P., Reis e Sousa C.. 2003. Viral infection switches non-plasmacytoid dendritic cells into high interferon producers. Nature 424: 324–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asselin-Paturel C., Brizard G., Pin J. J., Brière F., Trinchieri G.. 2003. Mouse strain differences in plasmacytoid dendritic cell frequency and function revealed by a novel monoclonal antibody. J. Immunol. 171: 6466–6477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemmi H., Takeuchi O., Kawai T., Kaisho T., Sato S., Sanjo H., Matsumoto M., Hoshino K., Wagner H., Takeda K., Akira S.. 2000. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 408: 740–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai T., Adachi O., Ogawa T., Takeda K., Akira S.. 1999. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity 11: 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar H., Kawai T., Kato H., Sato S., Takahashi K., Coban C., Yamamoto M., Uematsu S., Ishii K. J., Takeuchi O., Akira S.. 2006. Essential role of IPS-1 in innate immune responses against RNA viruses. J. Exp. Med. 203: 1795–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto M., Sato S., Hemmi H., Hoshino K., Kaisho T., Sanjo H., Takeuchi O., Sugiyama M., Okabe M., Takeda K., Akira S.. 2003. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science 301: 640–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauer J. D., Sotelo-Troha K., von Moltke J., Monroe K. M., Rae C. S., Brubaker S. W., Hyodo M., Hayakawa Y., Woodward J. J., Portnoy D. A., Vance R. E.. 2011. The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of Sting in the in vivo interferon response to Listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infect. Immun. 79: 688–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung S., Unutmaz D., Wong P., Sano G., De los Santos K., Sparwasser T., Wu S., Vuthoori S., Ko K., Zavala F., et al. 2002. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8+ T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity 17: 211–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hervas-Stubbs S., Rueda P., Lopez L., Leclerc C.. 2007. Insect baculoviruses strongly potentiate adaptive immune responses by inducing type I IFN. J. Immunol. 178: 2361–2369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Welsh, R. M., and M. O. Seedhom. 2008. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV): propagation, quantitation, and storage. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 15: Unit 15A.1.doi:10.1002/9780471729259.mc15a01s8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Boisgérault F., Rueda P., Sun C. M., Hervas-Stubbs S., Rojas M., Leclerc C.. 2005. Cross-priming of T cell responses by synthetic microspheres carrying a CD8+ T cell epitope requires an adjuvant signal. J. Immunol. 174: 3432–3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hervas-Stubbs S., Olivier A., Boisgerault F., Thieblemont N., Leclerc C.. 2007. TLR3 ligand stimulates fully functional memory CD8+ T cells in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help. Blood 109: 5318–5326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlecht G., Garcia S., Escriou N., Freitas A. A., Leclerc C., Dadaglio G.. 2004. Murine plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce effector/memory CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo after viral stimulation. Blood 104: 1808–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huarte E., Larrea E., Hernández-Alcoceba R., Alfaro C., Murillo O., Arina A., Tirapu I., Azpilicueta A., Hervás-Stubbs S., Bortolanza S., et al. 2006. Recombinant adenoviral vectors turn on the type I interferon system without inhibition of transgene expression and viral replication. Mol. Ther. 14: 129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Airenne K. J., Hu Y. C., Kost T. A., Smith R. H., Kotin R. M., Ono C., Matsuura Y., Wang S., Ylä-Herttuala S.. 2013. Baculovirus: an insect-derived vector for diverse gene transfer applications. Mol. Ther. 21: 739–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawasaki T., Kawai T., Akira S.. 2011. Recognition of nucleic acids by pattern-recognition receptors and its relevance in autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 243: 61–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iannacone M., Moseman E. A., Tonti E., Bosurgi L., Junt T., Henrickson S. E., Whelan S. P., Guidotti L. G., von Andrian U. H.. 2010. Subcapsular sinus macrophages prevent CNS invasion on peripheral infection with a neurotropic virus. Nature 465: 1079–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Probst H. C., Tschannen K., Odermatt B., Schwendener R., Zinkernagel R. M., Van Den Broek M.. 2005. Histological analysis of CD11c-DTR/GFP mice after in vivo depletion of dendritic cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 141: 398–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oldstone M. B. 2002. Biology and pathogenesis of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 263: 83–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y., Swiecki M., Cella M., Alber G., Schreiber R. D., Gilfillan S., Colonna M.. 2012. Timing and magnitude of type I interferon responses by distinct sensors impact CD8 T cell exhaustion and chronic viral infection. Cell Host Microbe 11: 631–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawai T., Takahashi K., Sato S., Coban C., Kumar H., Kato H., Ishii K. J., Takeuchi O., Akira S.. 2005. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat. Immunol. 6: 981–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Archer K. A., Durack J., Portnoy D. A.. 2014. STING-dependent type I IFN production inhibits cell-mediated immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog. 10: e1003861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keppler S. J., Rosenits K., Koegl T., Vucikuja S., Aichele P.. 2012. Signal 3 cytokines as modulators of primary immune responses during infections: the interplay of type I IFN and IL-12 in CD8 T cell responses. PLoS ONE 7: e40865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abe T., Kaname Y., Wen X., Tani H., Moriishi K., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O., Ishii K. J., Kawai T., Akira S., Matsuura Y.. 2009. Baculovirus induces type I interferon production through Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent pathways in a cell-type-specific manner. J. Virol. 83: 7629–7640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawai T., Akira S.. 2011. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity 34: 637–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fejer G., Drechsel L., Liese J., Schleicher U., Ruzsics Z., Imelli N., Greber U. F., Keck S., Hildenbrand B., Krug A., et al. 2008. Key role of splenic myeloid DCs in the IFN-αβ response to adenoviruses in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 4: e1000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thorburn J., Frankel A. E., Thorburn A.. 2003. Apoptosis by leukemia cell-targeted diphtheria toxin occurs via receptor-independent activation of Fas-associated death domain protein. Clin. Cancer Res. 9: 861–865 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennett C. L., van Rijn E., Jung S., Inaba K., Steinman R. M., Kapsenberg M. L., Clausen B. E.. 2005. Inducible ablation of mouse Langerhans cells diminishes but fails to abrogate contact hypersensitivity. J. Cell Biol. 169: 569–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahman A. H., Cui W., Larosa D. F., Taylor D. K., Zhang J., Goldstein D. R., Wherry E. J., Kaech S. M., Turka L. A.. 2008. MyD88 plays a critical T cell-intrinsic role in supporting CD8 T cell expansion during acute lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J. Immunol. 181: 3804–3810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gelman A. E., Zhang J., Choi Y., Turka L. A.. 2004. Toll-like receptor ligands directly promote activated CD4+ T cell survival. J. Immunol. 172: 6065–6073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.