Abstract

Independent slab-phase modulation allows 3D imaging of multiple volumes without encoding the space between volumes, thus reducing scan time. Parallel imaging further accelerates data acquisition by exploiting coil sensitivity differences between volumes. This work compared bilateral breast image quality from self-calibrated parallel imaging reconstruction methods such as modified sensitivity encoding (mSENSE), generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) and autocalibrated reconstruction for Cartesian sampling (ARC) for data with and without slab-phase modulation. A study showed an improvement of image quality by incorporating slab-phase modulation. Geometry factors (g-factors) measured from phantom images were more homogenous and lower on average when slab-phase modulation was used for both mSENSE and GRAPPA reconstructions. The resulting improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was validated for in vivo images as well using ARC instead of GRAPPA, illustrating average SNR efficiency increases in mSENSE by 5% and ARC by 8% based on ROI analysis. Furthermore, aliasing artifacts from mSENSE reconstruction were reduced when slab-phase modulation was used. Overall, slab-phase modulation with parallel imaging improved image quality and efficiency for 3D bilateral breast imaging.

Keywords: slab-phase modulation, bilateral breast, parallel imaging, breast MRI

Introduction

While breast cancer is the second leading cause of death due to cancer among American women [1], early diagnosis and treatment can reduce mortality rates [2]. Currently, the most common breast cancer screening method is X-ray mammography, which has limited ability to detect tumors in young women who have more dense breasts than postmenopausal women [3]. Several studies show that MRI has much higher sensitivity for detecting cancer, especially in high-risk patients [4, 5]. Recently, breast MRI has been recommended by the American Cancer Society for women at 20-25% or greater lifetime risk of breast cancer [6]. The ability of MRI to detect breast cancer is dependent on high-quality images, particularly with high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spatial resolution. In addition, for dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) breast imaging [7, 8], high temporal resolution is also helpful for accurate characterization of contrast kinetics.

Bilateral breast imaging can be more cost-effective than unilateral breast imaging and helps to detect contralateral tumors [9]. Normally bilateral breast MRI is conducted by exciting and imaging the two separated breasts together using a volume-selective excitation. The region between the two breasts might provide useful information for diagnosis; however, when high temporal resolution is needed, not imaging that region can be beneficial, as it usually occupies 20-30% of total volume. In addition, not exciting that region provides better shims over the two breasts and reduces cardiac motion artifacts. A dual-band spectral-spatial excitation pulse [10, 11] excites the two separate breast slabs simultaneously but independently with their own center frequencies and linear shims and, thus, provides robust fat-suppression over each slab [12]. It also allows independent slab-phase modulation (ISPM) during excitation [13]. This produces a “virtual shift” of the two slabs so they can be imaged as if they were one contiguous volume, eliminating the need to encode the region between the two breasts. Although interleaved imaging of the two slabs [14] is possible, simultaneous imaging of the two slabs allows us to utilize more sensitivity variation in the slab-direction and attain better SNR performance in parallel imaging applications.

Parallel imaging accelerates data acquisition by exploiting spatial sensitivity variation of phased-array coil to reconstruct undersampled data. There exist several different techniques depending on how reconstruction or coil sensitivity calibration is performed. For sensitivity encoding (SENSE) reconstruction [15], the unfolding process is conducted in the image domain using coil sensitivity information estimated from a separate scan. We refer to this reconstruction method as a “model-driven” method [16] as it models the underlying physical process during image acquisition. Residual aliasing artifacts may arise due to misregistrations or inconsistencies in coil sensitivities between calibration and acquisition. Self-calibrated parallel imaging schemes eliminate the need for separate calibration scans by acquiring a few additional calibration lines at the center to provide coil sensitivity information. Modified SENSE (mSENSE) [17] maintains the model-driven reconstruction process of the standard SENSE method but uses coil sensitivities calculated from fully sampled central k-space data. Alternatively, generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) [18] exploits central full k-space data to determine coil weights of estimating unacquired k-space data without explicit knowledge of coil sensitivities. This reconstruction method is called a “data-driven” method [16] as it relies on acquired data to estimate unacquired data using a data fitting approach. Like GRAPPA, autocalibrated reconstruction for Cartesian sampling (ARC) [19] is a data-driven method, but improves computational efficiency through a modified calibration algorithm and hybrid-space data reconstruction [20].

In this work, we compared reconstruction quality in accelerated bilateral breast imaging for acquisitions with and without ISPM. For each acquisition, we applied both model-driven and data-driven self-calibrated parallel imaging reconstruction methods. For phantom experiments, we measured noise amplification factors analytically and experimentally and also assessed aliasing artifacts. For in vivo experiments, we imaged eight volunteers and compared reconstructed image quality in terms of SNR (efficiency) and aliasing artifacts. Our work shows that incorporating ISPM with parallel imaging can provide better image quality with reduced scan time than only using parallel imaging.

Methods

Dual-Slab Excitation with Independent Slab-Phase Modulation

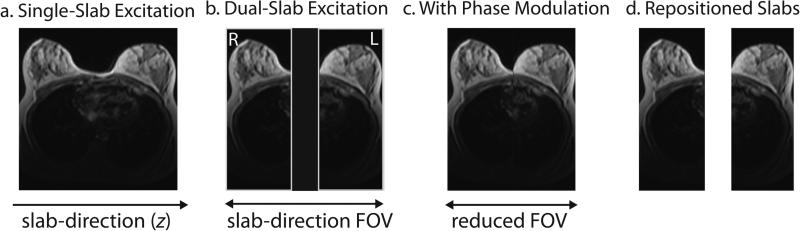

In sagittal bilateral breast imaging, two volumes of interest are separated in the slab direction (z direction, left/right), as shown in Fig. 1a. A dual-band pulse [10] simultaneously excites two limited slabs that can be positioned over the two breasts (Fig. 1b). However, 3D phase-encoding must still be performed over the two breasts and the empty space between them. By applying a different linear phase modulation to each slab with slab phase-encode location (kz) [13], a “virtual shift” is applied (Fig. 1c) and the slab-direction FOV can be reduced, reducing the number of phase-encode planes. This can be considered a 3D extension of phase-offset multiplaner imaging (POMP) [21]. After image reconstruction, the slabs can be repositioned (Fig. 1d) since the slab locations are known.

Figure 1.

Axial views showing sagittal slab positions for standard excitation, dual-slab excitation and independent slab-phase modulation. (a) Single-slab excitation excites a large volume including the right and left breasts and the space between them. (b) A dual-band pulse excites a slab over each breast simultaneously but independently; however, for simultaneous imaging of the two slabs, the two excited slabs and the space between them must be phase-encoded together. (c) By incorporating slab-phase modulation to the dual-band pulse, the two slabs are virtually shifted close together and the slab-direction FOV can be reduced. (d) After image reconstruction, the two slabs can be repositioned if the physical slab locations are known.

Parallel Imaging with Slab-Phase Modulation

SENSE

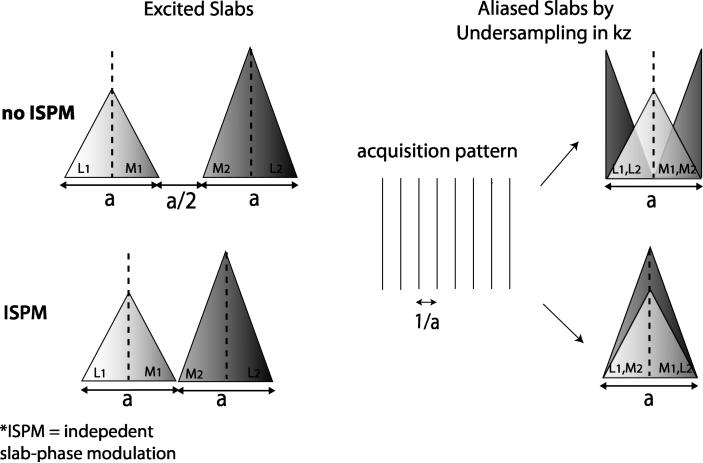

Here we assume that two slabs with thickness a are separated by distance 0.5a as shown in Fig. 2. Without ISPM the required slab-direction FOV is 2.5a including the empty space of 0.5a between the two excited slabs. Whereas, with ISPM the required slab-direction FOV can be reduced to 2a. If we undersample kz with interval 1/a, the two slabs are superimposed with a slab-direction FOV of a. When ISPM is not used, the slab centers are not aligned, resulting in the medial region of one slab to overlap with the medial region of the other slab and the lateral region of one slab to overlap with the lateral region of the other slab. Here, the boundary between the medial and lateral regions is determined by the location of the edges of the aliased slab, and thus depends on the slab separation. When ISPM is used, the centers of each slab are aligned, causing the medial region of one slab to overlap with the lateral region of other slab. Whether ISPM is applied or not, two slices, one from each slab, are superimposed at every z location. In particular, without ISPM the actual physical separation between superimposed slices is a (from medial regions) or 2a (from lateral regions) but with ISPM the separation is constant (1.5a). SENSE reconstruction with a factor of 2 unwraps each pair of two superimposed slices whether ISPM is applied or not [22], but the geometry factors (g-factors) over the slabs vary due to change of coil sensitivity differences. Changing g-factors by relocating aliasing artifacts is also used in the “controlled aliasing in parallel imaging results in higher acceleration” (CAIPIRINHA) method [23].

Figure 2.

Slab-phase modulation and undersampling. If two slabs with each thickness of a are separated by the distance of a/2, the total slab-direction FOV is 2.5a but by incorporating ISPM, the required FOV can be reduced to 2a. If undersampling is conducted in kz with the sampling interval of 1/a, two slabs are superimposed. When ISPM is not used, the center of the two slabs are misaligned, thus the medial region of one slab (M1) overlaps with the medial region of the other slab (M2), and the lateral region of one slab (L1) overlaps with the lateral region of other slab (L2). When ISPM is incorporated, the centers of the two slabs are aligned and the lateral region of one slab overlaps with the medial region of the other slab. The use of ISPM maintains the constant actual separation between superimposed slices, whereas if ISPM is not used, the separation varies.

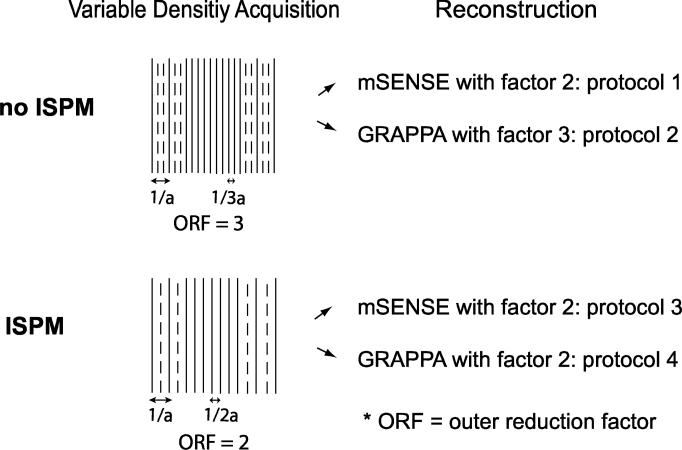

Self-Calibrated Parallel Imaging: mSENSE and GRAPPA

When self-calibrated parallel imaging methods such as mSENSE and GRAPPA are used for acceleration, additional kz planes are acquired in addition to the undersampled kz planes with interval 1/a to provide fully sampled central k-space data. However, the forms of the calibration line acquisition and parallel imaging reconstruction methods differ for data with and without ISPM, as shown in Fig. 3. When ISPM is not used, two additional kz planes should be acquired between two consecutive undersampled kz planes to estimate alias-free coil sensitivity information. If only one additional kz plane is acquired between the undersampled planes, the resulting low-resolution data (with a slab-directon FOV of 2a) still yields aliasing artifacts and is inadequate for calculating coil sensitivity information over a range of 2.5a. Thus, the outer reduction factor for data acquisition is 3. However, with ISPM the acquisition of one additional kz plane between two consecutive undersampled kz planes is enough to calculate coil sensitivity information with providing a 2a slab-direction FOV. In that case, the outer reduction factor is 2.

Figure 3.

Self-calibrated parallel imaging and reconstruction protocols. To apply self-calibrated parallel imaging techniques, extra central kz planes are acquired in addition to undersampled acquisition with interval 1/a. When ISPM is not used, central kz planes are acquired with interval 1/3a for adequate coil sensitivity information; however when ISPM is used, the central kz planes are acquired with interval 1/2a. So the outer reduction factors are 3 and 2 for each case. For reconstruction, the data without ISPM is reconstructed using mSENSE with a factor of 2 and GRAPPA with a factor of 3 (protocol 1,2). The data with ISPM is reconstructed using mSENSE with a factor of 2 and GRAPPA with a factor of 2 (protocol 3,4).

Depending on whether ISPM is used and which parallel imaging reconstruction is applied, four different protocols can be compared as represented in Fig. 3 and Tab. 1. The first protocol (no ISPM + mSENSE) excites the two slabs without ISPM, and mSENSE acceleration with a factor 2 is used to reconstruct only the regions of the two slabs; estimated coil sensitivity maps are rearranged by taking into account the physical slab locations. The second protocol (no ISPM + GRAPPA) excites slabs without ISPM, and GRAPPA acceleration with a factor of 3 is used; a slab-direction FOV after reconstruction is 3a. The third protocol (ISPM + mSENSE) excites with ISPM, and mSENSE acceleration with a factor of 2 is used; sensitivity maps need not to be rearranged. The fourth protocol (ISPM + GRAPPA) excites with ISPM and GRAPPA acceleration with a factor of 2 is used; a slab-direction FOV after reconstruction is 2a.

Table 1.

Protocols to be compared in terms of reconstruction quality. Given that a is a slab- direction FOV (see Fig. 3), a calibration slab-direction FOV and an acceleration factor used for each protocol are shown. Here, the calibration slab-direction FOV is the inverse of the central kz interval for variable density acquisition and the acceleration factor is used to formulate mSENSE and GRAPPA reconstructions.

| Protocol | ISPM | Calibration FOV | Acceleration Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | no ISPM + mSENSE | No | 3a | 2 |

| 2 | no ISPM + GRAPPA | No | 3a | 3 |

| 3 | ISPM + mSENSE | Yes | 2a | 2 |

| 4 | ISPM + GRAPPA | Yes | 2a | 2 |

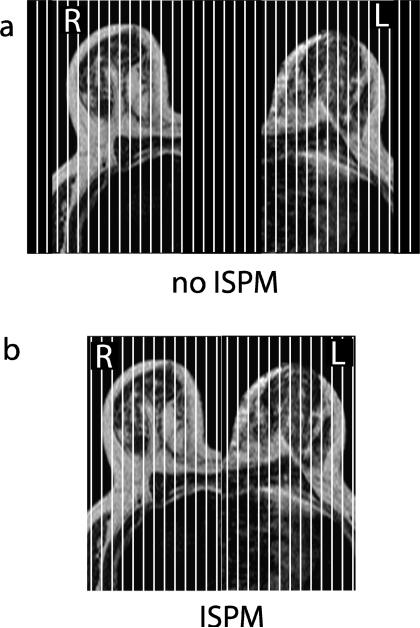

Image Acquisition and Reconstruction

Our experiments were conducted using a GE 1.5T Excite scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with a 40 mT/m maximum gradient amplitude and 150 mT/m/ms maximum gradient slew rate, and an eight-channel phased-array breast coil (GE Healthcare, Milaukee, WI). We scanned a liquid breast phantom (containing NaCl and NiCl2 · 6H2O) and eight volunteers. Informed consent was acquired from the volunteers according to an approved protocol under our institution's investigational review board. For each phantom or subject, data were acquired with and without ISPM using the dual-band spectral-spatial excitation pulse. Two separate slabs were selected using the graphical prescription included on the scanner. The slab separation varies from 0.3 to 0.7 times one slab thickness depending on breast geometry, having a contraint of an integer multiple of the section thickness [13]. When ISPM was not used, the two excited slabs and the space between the two slabs were phase-encoded as shown in Fig. 4, with 192 sagittal 3D sections and a 1.5 to 1.9 mm section thickness. When ISPM was used, the two excited slabs were encoded with a total of 128 sagittal sections and the same section thickness. For both cases, a 3D Cartesian readout was used with a 512 × 128 matrix over 20 × 20 cm2 FOV (in-plane), 30° flip angle, RF-spoiling, 22 ms TR and 7.6 ms TE. As the number of sections acquired for data with and without ISPM is the ratio of 2/3, the expected image SNR after full k-space reconstruction is the ratio of . These acquisitions were sub-sampled afterward to study the effect of parallel imaging.

Figure 4.

Slab positions, phase-encoded sections and FOV. (a) When ISPM was not applied, the two excited slabs and the empty space between them were phase-encoded with 192 sagittal 3D sections. (b) When ISPM was applied, the two excited slabs were encoded with 128 sagittal 3D sections.

Phantom Experiments

To obtain unaccelerated phantom images both with and without ISPM, fully sampled multicoil images were combined using sum-of-squares (SOS) reconstruction. Noise statistics in the receiver channels (represented by noise correlation matrix) [24,25] were incorporated when combining multicoil images to provide optimal SNR [24, 26]. The noise correlation matrix was estimated from noise data acquired by scanning the same phantom without RF excitation.

For parallel imaging applications, outer kz planes were discarded to simulate a reduced acquisition with a kz interval set to the inverse of one slab thickness. For the data without ISPM, kz planes were undersampled by a factor of 3 and 20 additional calibration planes were used, resulting in 31 central kz planes for estimating coil reconstruction kernels. For the data with ISPM, the data were undersampled by a factor of 2 and 12 additional calibration planes were used, resulting in 25 central kz planes. The numbers of extra calibration planes were chosen to provide the same matrix sizes for fitting GRAPPA kernels for both data sets.

Parallel imaging reconstruction was performed in each axially reformatted plane (kx × kz plane) after a 1D FFT in the y (superior/inferior) direction. For mSENSE reconstruction, low-resolution coil images from the Hamming-windowed central k-space data were normalized by the square-root of SOS magnitudes and used as coil sensitivity maps. The sensitivity matrix for each pixel of the aliased images was determined by using the coil sensitivities at the physical locations of the two superimposed pixels. The SENSE unfolding matrix was determined by integrating the estimated noise correlation matrix into the sensitivity matrix [15]. When ISPM is not used, the non-reconstructed space outside the excited slabs was set to zero. For GRAPPA reconstruction, kernels with size of 5×6 (kx×kz) were determined from 121×31 (without ISPM) and 121×25 (with ISPM) central full kx × kz data and used to reconstruct every missing line. Additional calibration lines were used only to calculate reconstruction kernels and were not used for final reconstruction. No regularization was used for both mSENSE and GRAPPA. After reconstruction, the two slab images were separated using the physical slab locations when ISPM was used.

The reconstructed image quality of the four protocols were compared in terms of reconstruction artifacts and SNR degradation. Reconstruction artifacts were assessed by subtracting fully-sampled SOS images from reconstructed images. The SNR degradation of each protocol was quantified by estimating g-factors both analytically and experimentally. The derivation of analytical g-factors for SENSE and GRAPPA reconstructions is shown in the Appendix. For mSENSE, sensitivity maps estimated from full k-space data were used to calculate g-factors using Eq. (A2). The g-factors from GRAPPA reconstruction were calculated using reconstruction kernels and weights for combining reconstructed coil images. We assumed that reconstructed full-FOV coil images were combined using the SOS method [24]. Experimental g-factors were calculated using the “pseudo multiple replica” method [27]. This method emulates acquisition of image replicas by adding synthesized noise generated from the noise correlation matrix to the acquired k-space data and measures SNR from the pixel-by-pixel evaluation of the mean signal and standard deviation through a stack of reconstructed images [28]. One hundred sets of replicated k-space data were created and mSENSE and GRAPPA reconstructions were applied. For each protocol, g-factor maps were calculated as the ratio of SNR of unaccelerated images and accelerated images, divided by the square-root of an acceleration factor [15].

In Vivo Experiments

For each subject, two sets of data, one without and one with ISPM, were acquired twice to measure SNR using the “difference method” [28, 29], where an estimate of mean signal is obtained from the sum images from the two replicated scans and noise variance is estimated from the difference images of the two scans. For acceleration, full k-space data were subsampled in the same manner as phantom data with retaining 31 central kz planes for data without ISPM and 21 central kz planes for data with ISPM. Instead of the GRAPPA reconstruction using 2D kernels, we applied ARC reconstruction using 3D kernels [19]. We did not use any regularization as phantom experiments. A kernel with size of 3 × 3 × 4 (kx × ky × kz) was determined from 64 × 64 × 31 (without ISPM) or 64 × 64 × 21 (with ISPM) central k-space data. The ARC reconstruction used all central kz planes directly for the final reconstruction.

Reconstruction artifacts and SNR of each protocol were also compared for in vivo data. Reconstruction artifacts were assessed by subtracting full k-space images from accelerated images as was done for the phantom images. SNR was measured in a total of 89 ROIs on breast tissues over the eight subjects by using the difference method. The ROIs were located at identical physical locations for all protocols. As the number of kz planes used for the reconstruction including calibration depends on whether or not ISPM was used, our final metric was SNR efficiency (SNR divided by the square-root of the number of kz planes used). For each ROI, the percent difference of SNR efficiency between different protocols was measured. In addition, further analysis was conducted to assess the effects of ISPM and reconstruction methods on the SNR efficiency with accounting for subject variability using a mixed-effects regression model [30]. A linear additive model, described in Eq. (1), was set up with use of ISPM and type of reconstruction method as two fixed factors, and subject as a random factor.

| (1) |

Here, P = 0 or 1 if ISPM is not used or is used, and R = 0 or 1 if mSENSE or ARC is used. βi are parameters to be estimated. Statistical analysis was done with Stata Release 9.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). A p-value of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Phantom Experiments

From the measured noise correlation matrix (Ψ) with loading of the breast phantom, coupling coefficients between coil i and coil k are calculated as . The magnitudes of coupling coeffcients are shown in Tab. 2. There exist some couplings between coils. Specially coil 1 is coupled with coils 2-4 and coil 8 is coupled with coils 5-7 with greater than 25% correlated power. However, given that coils 1-4 are located to image the right slabs and the others to image the left slabs, individual couplings between coils 1-4 and coils 5-8 are minor.

Table 2.

The magnitudes of coupling coefficients between eight coils in breast phased-array. ci,k represents the coupling coefficient between coil i and coil k. There exists coupling between coil 1 and coils 2-4, and coil 8 and coils 5-7, with more than 25% correlated noise power. Individual couplings between coils 1-4 (located for right slab) and coils 5-8 (located for left slab) are minor.

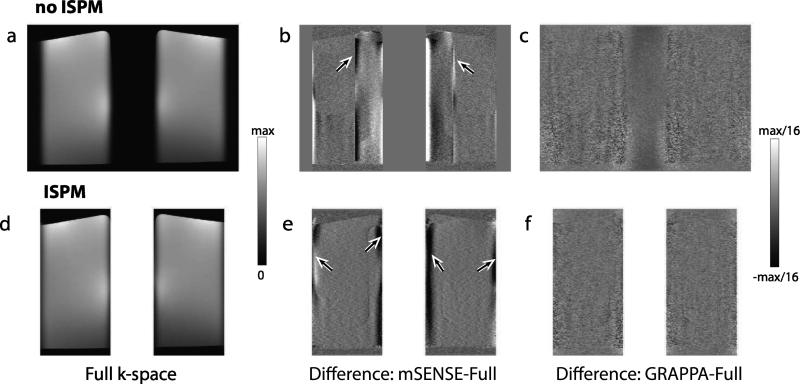

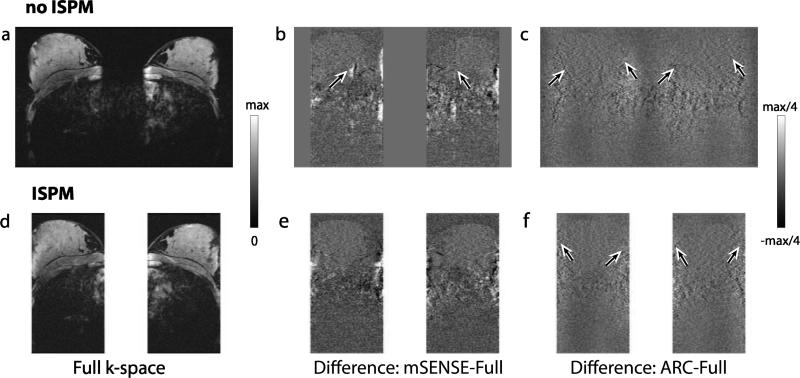

In Fig. 5, axially reformatted images of the phantom are shown. The unaccelerated images from full k-space data with and without ISPM are shown in Fig. 5a and d. Reconstruction artifacts from the four protocols are compared by subtracting accelerated images from unaccelerated images as shown in Fig. 5b-c and e-f. For mSENSE reconstruction, as low-resolution sensitivity maps were estimated, sensitivity values can be incorrectly estimated near object edges and residual aliasing artifacts can result. When ISPM is not used, as the edges of one slab are located in inner regions of other slab after undersampling, artifacts are generated in inner regions of both slabs after reconstruction shown by arrows. When ISPM is used, as the edges of both slabs are aligned, all residual aliasing artifacts arising from sensitivity errors around object edges are located at the edges of each slab, reducing aliasing artifacts in inner regions. For either case, imperfect slab profiles with a finite transition width can also cause aliasing artifacts at the edges of the two slabs. In GRAPPA reconstructed images, artifact levels were low as kernels were estimated from sufficient calibration areas.

Figure 5.

Phantom images with reconstruction artifacts. Axially reformatted phantom images from full k-space data without (a) and with (d) ISPM are shown. In (d), the two slabs are repositioned after image reconstruction. To compare reconstruction artifacts from the four protocols of acceleration, difference images between unaccelerated images and accelerated images with mSENSE (b,e) and GRAPPA (c,f) are shown. Residual SENSE aliasing artifacts by incorrectly estimated sensitivity values were denoted by arrows. For mSENSE reconstruction, ISPM results in a more consistent artifact level across the slabs. Note that because the images from full k-space data without and with ISPM have different SNR, the difference images alone cannot be used to compare SNR between different protocols.

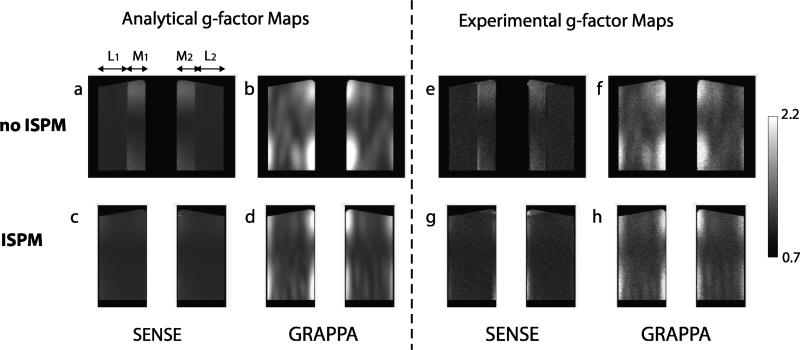

Figure 6 shows estimated g-factor maps using the phantom images from the same axial position as Fig. 5. Experimental g-factor maps calculated from the mean and standard deviation through 100 sets of reconstructed images show similar patterns to analytical g-factor maps [27]. If we divide each slab into the medial region and the lateral region corresponding to where the aliased slab is located as shown in Fig. 2, SENSE g-factors in the medial regions (M1,2) are higher than those in the lateral regions (L1,2) when ISPM is not used. This is because two superimposed slices from the region M1 and M2 have originally less physical separation, one slab thickness, than the two superimposed slices from the region L1 and L2, which are originally separated by two slab thickness, thus have less coil sensitivity difference. However, with ISPM, each pair of superimposed slices has the same physical separation (1.6 times of one slab thickness), resulting in a more uniform sensitivity difference and more homogenous g-factors across the volume. When comparing the g-factors from SENSE and GRAPPA, some differences are apparent. With GRAPPA g-factors, higher g-factors can be also seen in medial regions but g-factor variation across the medial and lateral regions is more smooth than that of SENSE g-factors. In addition, high g-factors can be observed at the two edges of each slab. The differences may be attributed to abrupt coil sensitivity changes that can lead to higher magnitude GRAPPA weights with the limited size of kernels.

Figure 6.

Measured g-factor maps from the phantom. The g-factors from the four different protocols were measured using phantom images analytically (a-d) and experimentally (e-h). Experimental measurements show similar patterns to analytical measurements. Without incorporating ISPM, g-factors in the region M1,2 are generally higher than in the region L1,2 for both SENSE and GRAPPA. However, by incorporating ISPM, g-factors are more homogenous. Higher g-factors at the two edges of each slab are detected with GRAPPA.

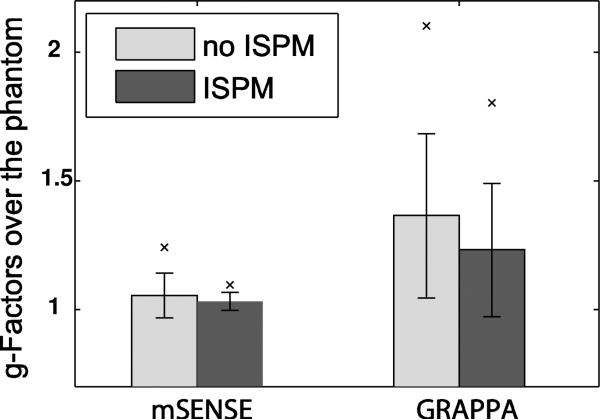

For each protocol, the mean analytical g-factor values over the phantom volume are shown in Fig. 7. By accounting for the noise correlation matrix in g-factor analysis, which assumes coil images are combined optimally by incorporating coil coupling, the mean values can be 1-3% lower than those achieved when coil coupling is simply ignored. A SENSE reconstruction can provide mean g-factors of 1.053 (without ISPM) and 1.030 (with ISPM), lower than mean GRAPPA g-factors of 1.351 (without ISPM) and 1.197 (with ISPM). By incorporating ISPM, more homogenous and lower g-factors can be achieved for both SENSE and GRAPPA reconstructions, as expected from the g-factor maps shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 7.

Comparison of g-factors for each protocol. The mean g-factors analytically calculated over the phantom volume are shown. Vertical lines represent ± standard deviation. ‘×’ denotes the 95th percentile of the g-factors. In both cases, ISPM results in a lower average g-factor, and lower variation of the g-factor.

In Vivo Experiments

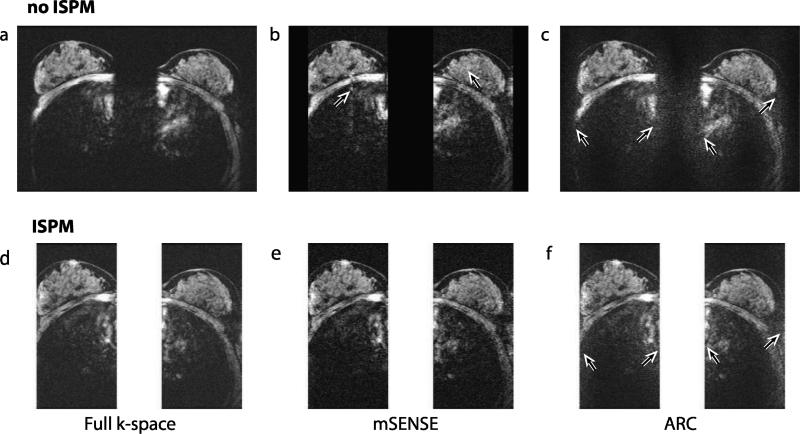

Figure 8 shows axially reformatted breast images from full k-space data and from acceleration using the four protocols. Without acceleration, noise is uniformly distributed across the image (Fig. 8a and d); however, using acceleration, noise level is spatially varying depending on g-factors (Fig. 8b-c and e-f). When comparing between the unaccelerated images, the image without ISPM (Fig. 8a) shows higher SNR than the image with ISPM (Fig. 8d) as it uses more kz planes. For ARC, noise enhancement at the two edges of each slab (Fig. 8c and f) is noticeable, as investigated with the phantom images. SENSE artifacts due to incorrectly estimated sensitivity maps at the edges of the slabs are seen in Fig. 8b. Figure 9 shows axially reformatted images from another volunteer. The difference images between accelerated images and unaccelerated images are shown with the unaccelerated images. In the difference images, artifacts and noise amplification similar to those shown in Fig. 8 are again observed.

Figure 8.

In vivo reconstructed images. Axially reformatted images from full k-space data (a,d), mSENSE reconstruction (b,e) and ARC reconstruction (c,f) are shown. With full k-space data noise is uniformly distributed across the image, but with acceleration noise level is spatially varying. Noise amplification at the edges of the two slabs by ARC reconstruction are shown by arrows (c,f). Note that as the numbers of kz planes directly used for reconstruction are not the same for each method, signal to noise level from these images does not reflect SNR efficiency of each method. In (b), SENSE residual artifacts due to incorrectly estimated sensitivity values are indicated by arrows. Cardiac motion artifacts are seen inside the chest wall.

Figure 9.

In vivo images and reconstruction artifacts. Axially reformatted images from another volunteer are shown. The reconstructed images from full k-space data without and with ISPM (a,d) and difference images between unaccelerated images and accelerated images with mSENSE (b,e) and ARC (c,f) are shown. Reconstruction artifacts and noise amplification denoted in Fig. 8 were observed.

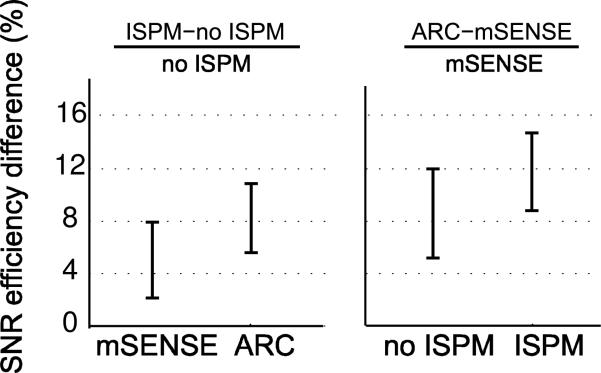

Figure 10 shows the averages of the percent differences in SNR efficiency from 89 ROIs between different pairs of two protocols. The SNR efficiency difference between ISPM incorporation and no incorporation was calculated separately for mSENSE and ARC reconstruction. In addition, the SNR efficiency difference between mSENSE and ARC was calculated separately for ISPM incorporation and no incorporation. The 95% confidence intervals for each mean of the difference are depicted. By incorporating ISPM, SNR efficiency is increased by 5% when mSENSE reconstruction is used and 8% when ARC reconstruction is used. When comparing different reconstruction methods, ARC provides 9% higher SNR efficiency than mSENSE when ISPM is not used and 12% higher SNR efficiency when ISPM is used.

Figure 10.

SNR efficiency percent difference between protocols. The SNR efficiency difference between ISPM incorporation and no incorporation was calculated separately for mSENSE and ARC reconstructions. And, the SNR efficiency difference between mSENSE and ARC was calculated separately for ISPM incorporation and no incorporation. The 95% confidence intervals of the mean differences are depicted. By incorporating ISPM, the mean SNR efficiency is increased for both mSENSE and ARC reconstructions. ARC provides higher SNR efficiency than mSENSE whether ISPM is incorporated or not.

The estimates of a linear mixed-regression model about SNR efficiency are shown in Tab. 3. The 95% confidence intervals of the coefficients corresponding to ISPM application and reconstruction method do not include zero, which indicates that both elements provide significant effects on SNR efficiency. Incorporating ISPM provides higher SNR efficiency than not incorporating ISPM (p < 0:01), and ARC provides higher SNR efficiency than mSENSE (p < 0:0001), as shown with the previous analysis. There was high between-subject variability, accounting for 64% of the remaining variance (95% confidence interval: 40-89%).

Table 3.

Estimates of the coefficients in the linear regression model to assess effects of ISPM and reconstruction methods on SNR efficiency.

| Variable | Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | z | P>|Z| | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | β 0 | −0.144 | 0.043 | −2.81 | 0.005 | [−0.227 −0.060] |

| ISPM (P) | β 1 | 0.024 | 0.009 | −2.59 | 0.010 | [ 0.006 0.042] |

| Reconstruction method (R) | β 2 | 0.037 | 0.009 | 4.02 | 0.000 | [ 0.019 0.055] |

Discussion

We have shown that the ISPM technique reduces residual aliasing artifacts and increases SNR efficiency when self-calibrated parallel imaging methods are applied for acceleration. The ISPM application reduces the number of calibration lines and resulting acquisition time, and simplifies SENSE reconstructions. In addition, it facilitates more homogenous g-factors with lower average and peak g-factors for both SENSE and GRAPPA reconstructions. Our g-factor improvement results are based on the experiments with the eight-channel phased-array coil, so some different results could occur with a different coil arrangement. However, we expect g-factors would be improved with most phased-array coils and this effect will be more pronounced when the ratio of acceleration factor to the number of coil elements is larger.

The SENSE g-factor change achieved by applying ISPM depends on geometry of the breast, slab thickness and slab separation, as these all affect the appearance of aliased slabs. If ISPM is not used, only when the slab separation is an integer multiple of the slab thickness are the centers of the two slabs aligned and are g-factors similar to those with using ISPM. Otherwise, medial regions of each slab are overlapped and lateral regions of each slab are overlapped and higher g-factors are generated in medial regions due to less coil sensitivity difference. In such a case, incorporation of ISPM can be beneficial as it provides perfect overlap and homogeneous g-factors. The reduction of g-factors by phase modulation is analogous with the CAIPIRINHA method [23], which modifies the appearance of aliasing artifacts by modulating the phase of the individual slices in multi-slice imaging.

The g-factors for SENSE and GRAPPA reconstructions were estimated using high SNR phantom images to minimize the effect of noise. For GRAPPA reconstructions, g-factors were derived from determined kernels to estimate missing data. Abrupt coil sensitivity changes can lead to higher magnitude GRAPPA kernels with limited sizes and may yield higher g-factors at some regions. We found that increasing the kernel sizes in the direction of abrupt changes does reduce g-factors; however, larger kernels require more calibration lines for accurate estimation. In this work, we chose kernel sizes empirically by trading g-factor amplitudes and the number of extra calibration lines required.

When low-resolution sensitivity maps are used for mSENSE reconstruction, sensitivity values can be incorrectly estimated around object edges or air/tissue boundaries and residual aliasing artifacts can result. With ISPM those artifacts are yielded at the edges of each slab, whereas without ISPM they can be located anywhere in the imaging slabs.

Throughout our work, we used dual-band pulse to excite only the two breasts without including the region between them. However, small volumes of breast tissues and lymph nodes might be located between the two breast slabs, which are relevant to breast diagnosis. For our clinical protocol, dual-band excitation and ISPM are only used for dynamic imaging where high temporal resolution is critical, and we scan the whole region for other T1 and T2-weighted imaging sequences. Even though we did not compare parallel imaging application to data with single-slab excitation, we expect that dual-slab excitation with ISPM still provides lower g-factors and less residual aliasing artifacts than single slab excitation.

To compare SNR of the different protocols from in vivo data, we used the difference method. This method assumes that there is no motion or signal changes between the two repeated scans. However, respiratory motion can cause misregistration of the two images and, thus, the subtracted images from the two scans may contain artifacts. To reduce any measurement errors, we carefully located ROIs in artifact-free regions on the subtracted images.

When we compare ARC and mSENSE, ARC provides higher SNR efficiency than mSENSE for in vivo measurement. This does not agree with phantom analysis that shows lower average g-factors with mSENSE than with GRAPPA. The in vivo analysis from the limited number of ROIs cannot represent the overall noise amplification of each protocol, and can give some discrepancy between the phantom and in vivo analysis. In addition, for in vivo ARC reconstruction, including extra calibration planes for final reconstruction increases SNR efficiency than mSENSE, which uses extra calibration planes only to estimate sensitivity maps.

For data-driven reconstruction, we used 2D kernels for the phantom experiment after a 1D FFT in the y direction, but used 3D kernels for the in vivo experiments by exploiting the ARC technique. Even though generating and applying 3D kernels is computationally intensive with normal GRAPPA reconstruction, the ARC technique allows faster reconstruction by synthesizing data in hybrid space. The application of 2D kernels and 3D kernels may not yield a large difference in reconstructed image quality if calibration area is sufficient. However, calibration data can be exploited more efficiently when estimating 3D kernels in kx × ky × kz space than when estimating 2D kernels in kx × kz space for each y location.

When applying ISPM, excitation RF phases should be linearly increased with the kz number. At the same time, RF excitation phases need to be linearly increased with sequence repetitions to maintain a steady-state of spin magnetization [31]. Thus, the acquisition order of kz planes should be properly determined for ISPM to be applied appropriately [13]. For a normal acquisition scheme, the simple sequential ordering of kz planes can satisfy the two constraints; however, for a variable density acquisition scheme, the acquisition order should be carefully considered.

Conclusions

By incorporating ISPM with a dual-band excitation, image quality is improved with reduced calibration time when self-calibrated parallel imaging methods are used for acceleration. ISPM modifies aliasing artifacts and facilitates g-factors that are more homogeneous and lower on average for both mSENSE and GRAPPA reconstructions. We used in vivo data to quantitatively validate the resulting SNR improvements. When ISPM is used, the measured SNR efficiency increased in mSENSE by 5% and ARC by 8% based on ROI analysis. Residual aliasing artifacts from mSENSE reconstruction were also reduced with ISPM. Overall, the addition of ISPM with both model-driven and data-driven parallel imaging methods simplifies reconstruction, increases image SNR efficiency, and reduces residual artifact levels.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jarrett Resenberg for assisting with statistical analysis, Dr. Marcus Alley for assisting with applying ARC reconstruction and Kristin Granlund for helping to prepare this article.

Appendix

Analytical g-Factor Calculation

Accelerated images from parallel imaging reconstructions have lower SNR than unaccelerated images. The SNR is decreased by the square-root of an acceleration factor (R) and a spatially varying g-factor, determined by the geometry of receive coil arrays. The g-factor is defined as

| (A1) |

where SNRfull is the SNR of optimally combined coil images [24] from full k-space data. For SENSE reconstruction, the g-factor is analytically calculated for each voxel [15] as

| (A2) |

where S is a sensitivity matrix from the superimposed positions and φ denotes the index of the voxel within the set of voxels to be separated. Ψ represents the noise correlation matrix [24], which describes the levels and correlations of noise in the receiver channels.

The g-factor for GRAPPA reconstruction can be calculated if additional calibration data are only used for determining the kernels but not used for the final reconstruction [32, 33]. To fill unacquired k-space data, reconstruction weights wk;l are estimated from autocalibration data and are then applied to unacquired k-space data () via convolution process. This approach is identical to the multiplication of aliased images () with the inverse Fourier transform of the convolutional kernel (Wk;l) as

| (A3) |

where N is the number of coils. If we combine coil images by using weights (pk), then

| A4) |

This GRAPPA formulation in the image domain allows for analyzing noise propagation into the final reconstructed images and measure g-factors by comparing noise variance of unaccelerated and accelerated images. Let's denote . Then, the GRAPPA g-factor for the Pth voxel can be defined as

| (A5) |

where q̃(l) = ql(rp) and p̃(l) = pl(rp), and rp denotes the position of the pth voxel.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, Fryback DG, Clarke L, Zelen M, Mandelblatt JS, Yakovlev AY, Habbema JD, Feuer EJ. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1784–1792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165–175. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kriege M, Brekelmans CT, Boetes C, Besnard PE, Zonderland HM, Obdeijn IM, Manoliu RA, Kok T, Peterse H, Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Muller SH, Meijer S, Oosterwijk JC, Beex LV, Tollenaar RA, de Koning HJ, Rutgers EJ, Klijn JG. Efficacy of MRI and mammography for breast-cancer screening in women with a familial or genetic predisposition. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:427–437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leach MO, Boggis CR, Dixon AK, Easton DF, Eeles RA, Evans DG, Gilbert FJ, Griebsch I, Ho RJ, Kessar P, Lakhani SR, Moss SM, Nerurkar A, Padhani AR, Pointon LJ, Thompson D, Warren RM. Screening with magnetic resonance imaging and mammography of a UK population at high familial risk of breast cancer: a prospective multicentre cohort study (MARIBS). Lancet. 2005;365:1769–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, Harms S, Leach MO, Lehman CD, Morris E, Pisano E, Schnall M, Sener S, Smith RA, Warner E, Ya e M, Andrews KS, Russell CA. American cancer society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75–89. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heywang SH, Wolf A, Pruss E, Hilbertz T, Eiermann W, Permanetter W. MR imaging of the breast with Gd-DTPA: use and limitations. Radiology. 1989;171:95–103. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.1.2648479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harms SE, Flamig DP, Hesley KL, Evans W, Cheek JH, Peters GN, Knox SM, Savino DA, Netto GJ, Wells RB. Fat-suppressed three-dimensional MR imaging of the breast. Radiographics. 1993;13:247–267. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.13.2.8460218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehman CD, Gatsonis C, Kuhl CK, Hendrick RE, Pisano ED, Hanna L, Peacock S, Smazal SF, Maki DD, Julian TB, DePeri ER, Bluemke DA, Schnall MD. MRI evaluation of the contralateral breast in women with recently diagnosed breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1295–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauly JM, Cunningham CH, Daniel BL. Independent dual-band spectral-spatial pulses.. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Toronto, Canada. 2003.p. 966. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham CH, Daniel BL, Rakow-Penner R, Pauly JM. Independent dual-band spectral-spatial pulses: implementation for bilateral breast MRI.. Proceedings of the 13th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Miami Beach; FL, USA. 2005.p. 1849. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han M, Rodriguez S, Sawyer AM, Daniel BL, Cunningham C, Pauly JM, Hargreaves BA. Fat suppression with independent shims for bilateral breast MRI.. Proceedings of the 17th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. 2009.p. 580. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hargreaves BA, Cunningham CH, Pauly JM, Daniel BL. Independent phase modulation for efficient dual-band 3D imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:798–802. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenman RL, Lenkinski RE, Schnall MD. Bilateral imaging using separate interleaved 3D volumes and dynamically switched multiple receive coil arrays. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:108–115. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:952–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brau AC, Beatty PJ, Skare S, Bammer R. Comparison of reconstruction accuracy and efficiency among autocalibrating data-driven parallel imaging methods. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:382–395. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Kluge T, Nittka M, Jellus V, Kühn B, Kiefer B. Parallel acquisition techniques with modified SENSE reconstruction (mSENSE).. Proceedings of the First Würzburg Workshop on Parallel Imaging Basics and Clinical Applications; Würzburg. 2001.p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA). Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beatty PJ, Brau AC, Chang S, Joshi SM, Michelich CR, Bayram E, Nelson TE, Herfkens RJ, Brittain JH. A method for autocalibrating 2-D accelerated volumetric parallel imaging with clinically practical reconstruction times.. Proceedings of the 15th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Berlin, Germany. 2007.p. 1749. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brau AC, Beatty PJ, Skare S, Bammer R. Efficient computation of autocalibrating parallel imaging reconstruction.. Proceedings of the 14th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Seattle, WA, USA. 2006.p. 2462. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glover GH. Phase-offset multiplanar (POMP) volume imaging: a new technique. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1991;1:457–461. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880010410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dougherty L, Isaac G, Rosen MA, Nunes LW, Moate PJ, Boston RC, Schnall MD, Song HK. High frame-rate simultaneous bilateral breast DCE-MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:220–225. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breuer FA, Blaimer M, Heidemann RM, Mueller MF, Griswold MA, Jakob PM. Controlled aliasing in parallel imaging results in higher acceleration (CAIPIRINHA) for multi-slice imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:684–691. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roemer PB, Edelstein WA, Hayes CE, Souza SP, Mueller OM. The NMR phased array. Magn Reson Med. 1990;16:192–225. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910160203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kellman P, McVeigh ER. Image reconstruction in SNR units: a general method for SNR measurement. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1439–1447. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh DO, Gmitro AF, Marcellin MW. Adaptive reconstruction of phased array MR imagery. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43:682–690. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200005)43:5<682::aid-mrm10>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robson PM, Grant AK, Madhuranthakam AJ, Lattanzi R, Sodickson DK, McKenzie CA. Comprehensive quantification of signal-to-noise ratio and g-factor for image-based and k-space-based parallel imaging reconstructions. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:895–907. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeder SB, Wintersperger BJ, Dietrich O, Lanz T, Greiser A, Reiser MF, Glazer GM, Schoenberg SO. Practical approaches to the evaluation of signal-to-noise ratio performance with parallel imaging: application with cardiac imaging and a 32-channel cardiac coil. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:748–754. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Firbank MJ, Coulthard A, Harrison RM, Williams ED. A comparison of two methods for measuring the signal to noise ratio on MR images. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:N261–N264. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/12/403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT. Linear mixed models: a practical guide using statistical software. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sobol WT, Gauntt DM. On the stationary states in gradient echo imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;6:384–398. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880060220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breuer FA, Blaimer M, Seiberlich N, Jakob PM, Griswold MA. A general formation for quantitative g-factor calculation in GRAPPA reconstructions.. Proceedings of the 16th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Toronto, Canada. 2008.p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beatty PJ, Brau AC. Analytical computation of g-factor maps for autocalibrated parallel imaging.. Proceedings of the 16th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Toronto, Canada. 2008.p. 1297. [Google Scholar]