Abstract

We investigated the hypothesis that individual differences in creative cognition can be manifest even in brief responses, such as single-word utterances. Participants (n = 193) were instructed to say a verb upon seeing a noun displayed on a computer screen and were cued to respond creatively to half of the nouns. For every noun–verb pair (72 pairs per subject), we assessed the semantic distance between the noun and the verb, using latent semantic analysis (LSA). Semantic distance was higher in the cued ("creative") condition than the uncued condition, within subjects. Critically, between subjects, semantic distance in the cued condition had a strong relationship to a creativity factor derived from a battery of verbal, nonverbal, and achievement-based creativity measures (β= .50), and this relation remained when controlling for intelligence and personality. The data show that creative cognition can be assessed reliably and validly from such thin slices of behavior.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0401-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Creative cognition, Creativity, Verb generation task, Semantic distance, Intelligence, Openness

Introduction

Creativity is an intriguing human ability, with far-reaching importance to science and society (see Dyer, Gregersen, & Christensen, 2009; Sawyer, 2012; Schunn, Paulus, Cagan, & Wood, 2006; Sternberg, 1998). It is widely agreed that creative products must be both novel and appropriate (or useful), and not simply random responding. For a scientific understanding of this seemingly ineffable construct, it is essential to be able to quantify individual differences and situational factors that influence performance. To address critical barriers to creativity research, we sought to investigate whether creativity can manifest reliably in brief samples—or "thin slices" (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1992)—of relatively simple behaviors.

We believe that this question both is interesting in its own right and has implications for neuroscientific investigations of creativity. A number of measures of creativity are available (see, e.g., Amabile, 1982; Fink, Benedek, Grabner, Staudt, & Neubauer, 2007; Ward, Smith, & Vaid, 1997). However, few creativity tasks meet the constraints of a neuroimaging environment, in which open-ended responding is generally hard to achieve without special equipment or expertise on the part of the participants (e.g., trained at jazz improvisation). As Fink et al. elaborate, most neuroimaging studies of creativity rely on relatively broad performance metrics, such as reaction time (RT) or the number of responses, which do not capture the creative quality of a behavior or product (e.g., Carlsson, Wendt, & Risberg, 2000; Jausovec, 2000; Molle, Marshall, Wolf, Fehm, & Born, 1999; Seger, Desmond, Glover, & Gabrieli, 2000). Like most investigators, we are skeptical that a person's creativity or creative potential could be fully measured using a single task. The goal of the present study was to test whether it is possible to assess variation in creative cognition from mere seconds of observed behavior.

We adapted a classic task from the cognitive neuroscience literature, known as the verb generation task, which was originally designed to evoke brain activity related to semantic processing (Petersen, Fox, Posner, Mintun, & Raichle, 1989). In the task, a noun is presented visually every few seconds, and the participant is instructed to say a verb out loud—simply, the first verb that comes to mind in response to the noun. As such, the task is easy to administer, even within the constraints of an imaging environment, and is adaptable to a wide variety of populations, including children or elderly adults. The task has since been used in many follow-up studies (Chiarello et al., 2006; McCarthy, Blamire, Rothman, Gruetter, & Shulman, 1993; Thompson-Schill, D’Esposito, Aguirre, & Farah, 1997; Thompson-Schill, D’Esposito, & Kan, 1999). Using event-related fMRI and recording the words spoken in the scanner has allowed for some sophisticated brain–behavior analyses based on the individual words (Barch, Braver, Sabb, & Noll, 2000). Two prior reports have suggested that unusual or low-frequency responses are particularly interesting, albeit as related to unusualness of responding in a statistical sense, rather than creativity specifically (Barch et al., 2000; Seger et al., 2000).

Our version of the task was quite similar to the original, except that, on half of the trials, subjects were prompted to respond creatively. Although an instruction to respond creatively may seem simplistic, it has been consistently shown to influence creativity across a wide variety of tasks, including divergent thinking (e.g., Harrington, 1975; Runco & Okuda, 1991), generating solutions for workplace-related problems (e.g., Shalley, 1991), writing essays about assigned passages (e.g., O'Hara & Sternberg, 2000–2001), collage making and alien drawing (e.g., Niu & Sternberg, 2001), story writing (e.g., Chen et al., 2005; Howard-Jones, Blakemore, Samuel, Summers, & Claxton, 2005), and creative analogical reasoning (Green, Cohen, Kim, & Gray, 2012), among others (cf. Amabile, 1979; Chua & Iyengar, 2008; Niu & Liu, 2009). Explicit creative instructions have also been shown to influence the relatedness of creative task performance to other measures of creativity (e.g., Harrington, 1975; see also Barron & Harrington, 1981; Chen, Himsel, Kasof, Greenberger, & Dmitrieva, 2006).

The verb generation task possesses certain features that make it an attractive candidate for assessing participants’ creative performance, at least in a verbal domain. Mednick (1962; see also Wallach & Kogan, 1965) proposed that associative ability lies at the heart of creativity and that the structure and strength of participants’ associative hierarchies impact individual differences in creativity. Our variant of the verb generation task provides a test of participants’ abilities to generate creative semantic associations on demand, in the context of a widely investigated cognitive-neuroscience task. Most creativity measures, such as divergent thinking tasks, the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking, story writing, and collage-making tasks, involve paper and pencil or other materials for their completion, thus making them difficult to implement in neuroimaging paradigms (Abraham & Windmann, 2007; Fink et al., 2007). To test whether "thin slices" of verbal behavior can be used for assessing individual differences in creativity, we administered a cued verb generation task, as well as a battery of standard creativity, intelligence, and personality measures.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 193; 88 male) ranged in age from 18 to 35 years (M = 22.1 years, SD = 3.7) and were recruited from Yale University and the surrounding community. The experimental protocol was approved by the Yale University Human Subjects Committee. We discovered after testing that 3 participants had taken part in another study that had employed some of the same measures used in the present study; these participants were excluded from analyses involving the overlapping measures to try to avoid practice effects. Data from 7 additional participants were excluded for the following reasons: Participants were taking psychoactive medications, were nonnative English speakers, exceeded the age limit for participation, or had participated in pilot testing for this study.

Given the exploratory nature of our work and our use of a novel creativity task, we were unsure about the number of participants necessary to achieve a robust effect size. We selected a large sample size in order to ensure that we would have enough power to detect a significant difference between performance on cued and uncued conditions of the verb generation task. Furthermore, it is common in the literature on individual differences in creativity to use large sample sizes that are similar in size to the one we chose (e.g., Nusbaum & Silvia, 2011).

Measures and procedure

In addition to the cued creativity verb generation task, participants completed assessments of creativity (divergent thinking tasks, story-writing task, Torrance figural tests, latent inhibition task, Creative Achievement Questionnaire), intelligence and executive functions (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices, three-back working memory task, task-switching paradigm), and personality (Big Five Aspect Scales and NEO-PI-R Openness to Experience scale). These measures are described below. Participants were tested individually, and the total duration of each testing session was approximately 2 h. The duration of each individual measure is specified in the relevant section below. Participants also completed two additional measures for research questions not relevant to our aims in this study: (1) a verbal four-term proportional analogical reasoning task, in which participants sought to identify valid analogical mappings between word pairs in two groups (“stem pairs” and “completion pairs”), and (2) a questionnaire used to assess the frequency and intensity of synesthetic experiences from self-report.

Creativity measures

Cued creativity verb generation task

On a given trial, participants were presented with a noun on a computer screen and were asked to say a verb that is related to the noun. For nouns presented in green, participants were instructed to think creatively when generating a verb response. Participants first performed five practice trials for the following nouns: “bowl” (uncued), “comb” (uncued), “fence” (cued), “basket” (cued), and “stage” (uncued). Of the 72 nouns used in experimental trials (see the Appendix, Table 6), half (36) were shown in green (cued condition), and the other half in purple (uncued condition). Cued and uncued trials alternated in sets of two (e.g., two cued trials were followed by two uncued trials, etc.). Because we were interested in individual differences, we chose not to counterbalance the assignment of nouns to conditions (cued, uncued). Each noun can be classified in terms of the extent to which it intrinsically imposes constraints on the verb response (see Barch et al., 2000). A high-constraint noun is one for which there is a single common verb associate (e.g., for “scissors,” almost all participants say “cut”). A low-constraint noun is one for which there is not a single common verb associate (e.g., for “house,” the verb “live”). By design, the two word lists did not differ in terms of their average constraint, where constraint refers to the extent to which the noun is associated with a single common verb associate. We used data from an independent sample to empirically assess the frequency, for each noun, of the most commonly generated verbs. Two cued and two uncued items were removed from all constraint analyses, because the frequency of the most commonly generated verb response for these items was equal to the median value. Of the remaining 68 nouns, no significant difference was found between cued and uncued nouns in the mean frequencies of their most commonly generated verb responses (p > .32).

Table 6.

Noun stimuli used in the cued creativity verb generation task

| Trial # | Stimulus | Constraint Level | Most Common Response | Frequency of Most Common Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1N | leaf | low | fall | .437 |

| 2N | taxi | low | drive | .380 |

| 3C | coal | burn | .451 | |

| 4C | house | low | live | .380 |

| 5N | rock | high | throw | .521 |

| 6N | card | high | play | .465 |

| 7C | shoe | high | wear | .549 |

| 8C | oath | high | take | .521 |

| 9N | birth | fly | .451 | |

| 10N | street | low | walk | .408 |

| 11C | lamp | low | light | .423 |

| 12C | canoe | low | paddle | .408 |

| 13N | needle | sew | .451 | |

| 14N | home | low | live | .352 |

| 15C | office | high | work | .606 |

| 16C | belt | high | wear | .535 |

| 17N | finger | high | point | .521 |

| 18N | blade | high | cut | .521 |

| 19C | oven | low | cook | .380 |

| 20C | fist | low | punch | .408 |

| 21N | cart | high | push | .493 |

| 22N | tongue | low | lick | .380 |

| 23C | shovel | high | dig | .521 |

| 24C | dish | low | wash | .352 |

| 25N | pill | high | take | .535 |

| 26N | flower | low | smell | .437 |

| 27C | note | high | write | .507 |

| 28C | church | low | pray | .338 |

| 29N | boot | low | wear | .423 |

| 30N | snow | low | shovel | .380 |

| 31C | feet | high | walk | .521 |

| 32C | paper | low | write | .408 |

| 33N | artist | high | paint | .479 |

| 34N | tree | high | climb | .563 |

| 35C | cannon | high | shoot | .493 |

| 36C | tune | low | play | .338 |

| 37N | poem | high | read | .465 |

| 38N | soap | high | wash | .592 |

| 39C | drum | low | play | .423 |

| 40C | bucket | low | fill | .366 |

| 41N | cafe | low | eat | .380 |

| 42N | store | low | buy | .437 |

| 43C | muscle | low | flex | .380 |

| 44C | couch | high | sit | .563 |

| 45N | drug | high | take | .592 |

| 46N | rose | high | smell | .465 |

| 47C | soup | high | eat | .507 |

| 48C | letter | low | write | .423 |

| 49N | pillow | high | sleep | .592 |

| 50N | tool | high | use | .479 |

| 51C | debt | high | pay | .606 |

| 52C | music | low | play | .437 |

| 53N | ring | low | wear | .380 |

| 54N | hole | high | dig | .592 |

| 55C | horn | high | blow | .606 |

| 56C | razor | cut | .451 | |

| 57N | golf | high | play | .592 |

| 58N | manual | high | read | .577 |

| 59C | infant | low | cry | .352 |

| 60C | clay | low | mold | .352 |

| 61N | hair | low | comb | .352 |

| 62N | baby | high | cry | .507 |

| 63C | money | high | spend | .479 |

| 64C | phone | low | call | .408 |

| 65N | glass | low | break | .408 |

| 66N | pan | low | cook | .380 |

| 67C | candle | high | light | .577 |

| 68C | grass | low | cut | .380 |

| 69N | bread | high | eat | .479 |

| 70N | sofa | high | sit | .535 |

| 71C | key | low | open | .366 |

| 72C | ship | high | sail | .507 |

Note. Numbers indicate the trial number, "N" denotes normal (uncued) condition, and "C" denotes cued (creative) condition. “Constraint Level” was determined using a median split of the frequency of the most common verb responses, as described in the main text. “Most Common Response” and “Frequency of Most Common Response” values were obtained from an independent sample. Noun stimuli with no constraint level indicated are those items that were removed from all constraint analyses, because the frequency of the most commonly generated verb response for these items was equal to the median value

For each noun, participants were given 8 s to indicate their response by speaking aloud into a microphone connected to a digital voice recorder (task duration: approximately 9 min). From these responses, we derived two measures of performance, the first being the RT, as the latency until the start of the spoken response (the verb). RTs were obtained using Psyscope (Cohen, MacWhinney, Flatt, & Provost, 1993), which recorded the time from noun onset to the onset of a vocal response (using an external button box). Participants’ responses were later transcribed from the digital voice recordings. The second measure was an index of the semantic distance of each verb to the presented noun as derived by latent semantic analysis (LSA; Landauer, Foltz, & Laham, 1998; http://lsa.colorado.edu). LSA is a method for quantifying the similarity between words (or even whole passages) on the basis of statistical analyses of a large corpus of text. We used the topic space of “general reading up to first-year college (300 factors)” and term-to-term comparison type. Technically, this measure of semantic similarity corresponds to the cosine of the angle between vectors corresponding (in our usage) to a noun and a verb within a given semantic space, which is derived through analyses of all of the contexts in which the word tends to be present or absent in that topic space (Landauer et al., 1998; see also Laham, 1997; Landauer & Dumais, 1997). To provide a measure of semantic distance (i.e., the inverse of semantic similarity), LSA-derived semantic similarity values were subtracted from 1 (i.e., semantic distance = 1 − semantic similarity from LSA). Thus, the higher the semantic distance value between two words, the less similar they are in semantic space. LSA values provide a highly reliable measure of noun–verb semantic distance, one with low measurement error and reasonable construct validity. We have previously used LSA to obtain a quantifiable measure of creativity in analogical reasoning, establishing a continuum of semantic distance between within-domain (less creative) and cross-domain (more creative) analogical reasoning (Green, Fugelsang, & Dunbar, 2006; Green, Fugelsang, Kraemer, & Dunbar, 2008; Green, Kraemer, Fugelsang, Gray, & Dunbar, 2010, in press).

Semantic distance is a measure not of the unusualness of the verb but, rather, of the unusualness of the verb in the context of the given noun; note that the noun is the same for all participants but the verbs can vary. Participants’ verb responses were screened for general appropriateness, and the following types of responses were excluded from all analyses: nonverbs (1.7 % of all responses) and verb responses that were not in the LSA corpus (1.4 % of all responses). Additionally, verb forms were standardized by adding the –ing suffix (e.g., “cut” and “cuts” were both standardized to “cutting”) to ensure that responses with the same verb stem corresponded to the same semantic distance value. Semantic distance values for each nounverb pair were calculated and then averaged within participants, doing so separately for the cued ("creative") and uncued conditions.

Data from 10 participants were excluded from all analyses involving semantic distance values for the verb generation task. For 7 participants, their vocal responses were not recorded, due to equipment failure, and the remaining 3 participants had fewer than 50 % of appropriate responses in either the cued or the uncued condition. N = 183 participants contributed to analyses of semantic distance. For RTs, an additional 8 participants were excluded, because each had fewer than 50 % of voice-onset RTs recorded by the button box. Thus, N = 175 participants contributed to analyses of verb generation RT.

Divergent thinking tasks

Participants were administered three divergent thinking problems (Torrance, 1966). For the first problem, participants were asked the following: “Suppose that all humans were born with six fingers on each hand instead of five. List all the consequences or implications that you can think of.” For the second problem, participants were asked to “list as many white, edible things as you can.” For the third problem, participants were asked to “list all the uses you can think of for a brick.” Participants were given 3 min for each problem (task duration: 9 min).

Two students at Yale University served as independent raters and assessed participants’ responses for flexibility, fluency, and originality. Flexibility refers to the total number of different categories that a participant used in each problem, in addition to the number of times that a participant changed the category of his or her response. Fluency refers to the total number of responses. Originality refers to the unusualness (relative to the responses of the other participants in the sample) of participants’ responses. Reliability was high, as assessed by intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) across the two ratings for each dimension. For each dimension, interrater reliability for the three problems was the following: flexibility, ICC = .91–.95; fluency, ICC = .97–.99; and originality, ICC = .95–.97. The average ratings were used in subsequent analyses.

Participants’ scores on each dimension were converted to z scores for each problem. These z scores were then summed across the three problems to create a separate z score for flexibility, fluency, and originality for a given participant. The sum of z scores across dimensions represents the divergent thinking total score.

Data from 9 participants were removed from all analyses involving the divergent thinking task due to missing data or failure to follow task instructions or for taking more than the allotted time on a given problem. N = 184 participants contributed data to analyses of divergent thinking.

Story-writing task

The story-writing task is a measure of creative production. Participants were instructed to write a very short story (around four sentences long) including the following three words presented at the top of the computer screen: “stamp,” “send,” and “letter” (task duration: approximately 5 min). Participants were instructed to try to use their imagination and to be creative when writing their story. Participants typed their responses into a standard text-editor program. Four participants with story lengths that were greater than three standard deviations from the mean were excluded from all analyses of story-writing task performance. Data from 7 participants were excluded due to missing data or uninterpretable stories. A total of 182 participants contributed data to all story-writing task analyses.

Three students at Yale University served as independent raters and assessed participants’ stories on the following five dimensions: overall creativity (the extent to which the participant told a unique story that “came alive”), descriptiveness (the extent to which the participant added additional details), semantic flexibility (the manner and number of unique ways in which the participant used the three words), humor (the extent to which the participant incorporated clever, witty, and/or amusing elements into the story), and emotiveness (the extent to which the participant used words that convey emotion and shifts of emotion). Raters assessed each of these dimensions on a 7-point scale (1–7), with 1 reflecting a low rating and 7 reflecting a high rating.

Reliability was assessed as the ICC across the three ratings for each dimension. For each dimension, ICC values indicated good reliability: overall creativity (ICC = .87), descriptiveness (ICC = .87), semantic flexibility (ICC = .90), humor (ICC = .77), and emotiveness (ICC = .77). The average rating on each dimension across raters was used in all reported analyses.

The story-writing dimensions were positively correlated (r values = .27–.88). An exploratory factor analysis using principal axis factoring and direct oblimin rotation (allowing the factors to correlate) was performed on the five story-writing dimensions listed above. Only one factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0 was obtained, and this factor accounted for 68.1 % of the variance. Because all of the story-writing dimensions loaded on the same factor, we calculated a story-writing total score, consisting of the sum of each of the z-scored dimension scores. In all of the correlation tables, we report correlations with the story-writing total score.

Although participants were instructed to write very short stories (around four sentences long), there was a great deal of variability in story length (M = 71.7 words, SD = 25.8; range: 19–155 words). Additionally, story word count correlated strongly with story-writing total scores, r(180) = .65. To ensure that the correlations with story-writing performance did not merely reflect story length, all reported correlations in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5 are partial correlations after controlling for word count. Because the zero-order and partial correlations were very similar, and in order to ease interpretability, all figures use the raw scores.

Table 2.

Correlations between verb generation task performance and creativity measures (divergent thinking, story writing, Torrance figural tests, latent inhibition, and Creative Achievement Questionnaire [CAQ])

| Verb Generation Task Semantic Distance | Divergent Thinking | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cued | Uncued | Total | Flexibility | Originality | Fluency | Story Writing Total | Torrance Total | Latent Inhibition (Residual RT) | |

| Verb generation cued semantic distance | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Verb generation uncued semantic distance | .11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Divergent thinking total | .47 | .08 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Flexibility | .42 | .07 | .94 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Originality | .48 | .14 | .92 | .76 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fluency | .43 | .02 | .98 | .91 | .86 | – | – | – | – |

| Story writing total | .40 | .05 | .34 | .35 | .30 | .32 | – | – | – |

| Torrance total | .18 | −.08 | .33 | .36 | .25 | .32 | .21 | – | – |

| Latent inhibition (residual RT) | −.11 | −.15 | .00 | .07 | −.06 | .01 | −.12 | −.01 | – |

| log CAQ total | .19 | .12 | .21 | .22 | .21 | .18 | .13 | .05 | .13 |

Note. Significant correlations (p < .05) indicated in bold. Marginally significant correlations (p < .10) indicated in italics. Not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Table 3.

Correlations between log Creative Achievement Questionnaire (CAQ) domain scores and creativity measures

| Log CAQ Domain Scores | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Architecture | Creative Writing | Culinary | Dance | Humor | Inventions | Music | Science | Theater | Visual Arts |

| Verb generation cued semantic distance | .07 | .04 | .09 | .09 | .02 | .10 | .10 | .15 | .09 | .18 |

| Verb generation uncued semantic distance | .05 | .17 | .00 | −.04 | .01 | −.06 | .02 | .10 | .11 | .05 |

| Divergent thinking total | .17 | .14 | .11 | .03 | .01 | .16 | .08 | .22 | .10 | .15 |

| Flexibility | .16 | .13 | .11 | −.03 | .02 | .17 | .09 | .24 | .09 | .15 |

| Originality | .15 | .15 | .11 | .05 | .02 | .15 | .05 | .17 | .09 | .18 |

| Fluency | .16 | .12 | .10 | .06 | .00 | .13 | .08 | .20 | .09 | .11 |

| Story writing total | .12 | .03 | −.16 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 | .09 | .05 | .16 | .08 |

| Torrance total | .02 | .07 | −.04 | −.16 | −.02 | .10 | .08 | .05 | .03 | .09 |

| Latent inhibition (residual RT) | .03 | −.05 | .08 | .06 | .01 | .08 | .15 | .04 | .01 | −.04 |

Note. Significant correlations (p < .05) indicated in bold. Marginally significant correlations (p < .10) indicated in italics. Not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Table 4.

Correlations between creativity measures and intelligence and executive function measures

| Verb Generation Task Semantic Distance | Divergent Thinking | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Cued | Uncued | Total | Flexibility | Originality | Fluency | Story Writing Total | Torrance Total | Latent Inhibition (Residual RT) | log CAQ Total |

| RAPM accuracy | .44 | −.16 | .38 | .40 | .32 | .36 | .40 | .28 | .02 | .11 |

| WAIS total DQ | .46 | −.04 | .48 | .53 | .36 | .46 | .49 | .31 | .07 | .16 |

| Verbal DQ | .39 | .01 | .44 | .49 | .33 | .43 | .46 | .28 | .05 | .13 |

| Performance DQ | .41 | −.07 | .39 | .43 | .30 | .37 | .39 | .26 | .08 | .16 |

| 3-back accuracy | .25 | −.25 | .19 | .23 | .10 | .21 | .17 | .16 | .01 | .07 |

| 3-back d′ | .08 | −.22 | .14 | .15 | .07 | .16 | .12 | .02 | .02 | .08 |

| 3-back mean RT | .10 | .03 | −.03 | −.02 | −.06 | .00 | .13 | −.01 | .02 | −.05 |

| Switch cost (residual RT) | .01 | −.01 | .06 | .04 | .10 | .03 | .14 | .07 | −.01 | .01 |

Note. Significant correlations (p < .05) indicated in bold. Marginally significant correlations (p < .10) indicated in italics. Not corrected for multiple comparisons. RAPM, Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; DQ, deviation quotient

Table 5.

Correlations between creativity measures and personality measures (Big Five Aspects Scales [BFAS], NEO openness)

| Verb Generation Task Semantic Distance | Divergent Thinking | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality Measure | Cued | Uncued | Total | Flexibility | Originality | Fluency | Story Writing Total | Torrance Total | Latent Inhibition (Residual RT) | log CAQ Total |

| BFAS openness | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.08 | .10 | .07 | .04 | .22 | .18 | .00 | .39 |

| BFAS intellect | −.03 | .03 | .06 | .11 | .00 | .07 | .00 | .05 | .05 | .22 |

| BFAS assertiveness | −.21 | .14 | .10 | .06 | .12 | .09 | −.09 | −.01 | .04 | .25 |

| BFAS enthusiasm | −.09 | .04 | .09 | .09 | .08 | .08 | .03 | .14 | .07 | .18 |

| BFAS orderliness | −.20 | −.08 | .07 | .06 | .01 | .12 | −.10 | .05 | .06 | −.08 |

| BFAS industriousness | −.22 | .08 | .01 | −.01 | −.02 | .05 | −.18 | −.09 | .04 | .12 |

| BFAS politeness | −.09 | −.13 | −.22 | −.19 | −.27 | −.15 | .004 | .08 | .04 | −.11 |

| BFAS compassion | .08 | −.02 | .13 | .10 | .12 | .15 | .04 | .20 | .07 | .04 |

| BFAS withdrawal | .10 | −.04 | .08 | .09 | .04 | .09 | .03 | .10 | −.09 | −.09 |

| BFAS volatility | .03 | −.03 | .12 | .11 | .10 | .12 | .01 | .06 | −.10 | −.04 |

| NEO actions | .17 | .16 | .10 | .11 | .13 | .05 | .16 | .16 | −.06 | .17 |

| NEO aesthetics | .18 | .03 | .10 | .10 | .10 | .08 | .19 | .15 | .07 | .40 |

| NEO fantasy | .17 | .03 | .05 | .11 | .03 | .01 | .15 | .20 | −.03 | .16 |

| NEO feelings | .13 | −.01 | .14 | .15 | .11 | .13 | .22 | .13 | −.01 | .25 |

| NEO ideas | .05 | .04 | .07 | .10 | .05 | .07 | .01 | .04 | .07 | .19 |

| NEO values | .21 | .02 | .17 | .21 | .12 | .16 | .13 | .32 | −.08 | .05 |

Note. Significant correlations (p < .05) indicated in bold. Marginally significant correlations (p < .10) indicated in italics. Not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Abbreviated Torrance Test for Adults (ATTA): figural tests

Participants completed Activities 2 and 3 of the Abbreviated Torrance Tests for Adults (ATTA) as a shortened version of the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. Activities 2 and 3 are the figural tests of the ATTA and assess nonverbal creative abilities. For Activity 2 of the ATTA, participants were asked to do the following: “Use the incomplete figures below to make some pictures. Try to make your pictures unusual. Your pictures should communicate as interesting and as complete a story as possible. Be sure to give each picture a title.” For Activity 3, participants were given nine triangles on a sheet of paper and were asked to do the following: “See how many objects or pictures you can make from the triangles below, just as you did with the incomplete figures. Remember to create titles for your pictures.” Participants were given 3 min to complete each Activity (task duration: 6 min). A total of 193 participants contributed data to all Torrance analyses.

Three students at Yale University served as independent raters and assessed participants’ designs on two sets of measures: norm-referenced and criterion-referenced creativity indicators. Norm-referenced measures consist of the following dimensions: fluency (the total number of responses for each problem), originality (the unusualness of participants’ responses), and elaboration (the number of elaborative details that participants added to their designs). Activity 3 was rated on the additional norm-referenced measure of flexibility (the number of different ways in which participants used the triangles). Criterion-referenced creativity indicators consisted of the following dimensions: “openness and resistance to premature closure,” “unusual visualization, different perspective,” “movement and/or sound,” “richness and/or colorfulness of imagery,” “abstractness of titles,” “articulateness in telling story,” “combination/synthesis of two or more figures,” “internal visual perspective,” “expressions of feelings and emotions,” and “fantasy.” Raters assessed each criterion-referenced measure on a 3-point scale (0–2), with a rating of 0 reflecting a low rating and 2 reflecting a high rating.

Reliability was assessed as the ICC across the three ratings for each norm-referenced measure and the sum of criterion-referenced measure scores. ICC values for the average of ratings across the three raters indicated good interrater reliability for fluency (Activity 2, ICC = .92; Activity 3, ICC = .96), originality (Activity 2, ICC = .66; Activity 3, ICC = .57), elaboration (Activity 2, ICC = .91; Activity 3, ICC = .92), flexibility (Activity 3, ICC = .86), and the sum of criterion-referenced measures (ICC = .84). The average of ratings across the three raters for each dimension was used in all reported analyses.

For each Activity, participants’ scores were converted to z-scores for each norm-referenced dimension. The sum of participants’ scores across all criterion-referenced measures for Activities 2 and 3 was added to the sum of z-scores across all norm-referenced measures to create a Torrance total score. In all of the correlation tables, we report correlations with the Torrance total score for ease of interpretability.

Latent inhibition task

Participants completed a latent inhibition (LI) task (task duration: 7 min). LI assesses the extent to which participants experience difficulty in learning to associate a preexposed, formerly irrelevant, stimulus with an outcome. In between-subjects versions of the task, participants who are preexposed to a stimulus tend to require more time to learn the association, as compared with participants who have not been preexposed. The task measures the difficulty participants have in this form of reversal learning. The LI task was included as a putative measure of creativity based largely on Eysenck’s theory of creative achievement (Eysenck, 1993, 1995), which points to reduced LI as a marker of the overlap between high creative achievement and schizotypal personality. Specifically, highly creative individuals are predicted to show a tendency toward attentional “overinclusiveness” of stimuli that others would ignore, just as schizotypal personality is characterized by an inability to exclude irrelevant stimuli from attention (Gray, Feldon, Rawlins, Hemsley, & Smith, 1991; Gray, Hemsley, & Gray, 1992). LI has been negatively associated with the “Big Five” (Costa & McCrae, 1992) personality trait of openness to experience (Carson, Peterson, & Higgins, 2003; Peterson & Carson, 2000; Peterson, Smith, & Carson, 2002), and openness to experience has been found to positively correlate with trait creativity (e.g., McCrae, 1987). However, the association between LI and openness to experience has been inconsistent (Wuthrich & Bates, 2001), and at least one prior report did not find a predicted negative association between LI and trait creativity (Burch, Hemsley, Pavelis, & Corr, 2006).

We used a within-participants version of the LI task (Evans, Gray, & Snowden, 2007). The LI effect was calculated as the difference in mean RTs for preexposed and nonpreexposed stimuli, where a positive difference score indicates the presence of LI. As is described below, a more robust LI effect was found for the RT data, as compared with accuracy data. Thus, we focus on the RT measures for all correlational analyses. In order to control for processing speed, a regression was performed in which RTs from preexposed stimuli were regressed on RTs from nonpreexposed stimuli. The residuals from this regression were used as a measure of LI.

The same exclusionary criteria as in Evans et al. (2007) were employed: Participants who had more than 7 errors of omission or more than 14 errors of commission were excluded from all analyses involving the LI task. Using these criteria, data from 15 participants were excluded from all LI analyses. Two additional participants were excluded from all LI analyses due to missing data. A total of 176 participants contributed data to all LI analyses.

Creative achievement questionnaire

The Creative Achievement Questionnaire (CAQ; Carson, Peterson, & Higgins, 2005) consists of 80 questions, 8 in each of the following domains: visual arts, music, dance, architectural design, creative writing, humor, inventions, scientific discovery, theater and film, and culinary arts (task duration: approximately 5 min).

CAQ total scores (summed across all 10 domains) and individual domain scores were log-transformed in order to better approximate a normal distribution. All analyses involving the CAQ measure employ log CAQ scores. Data from 3 participants were excluded from all analyses involving the CAQ, due to missing data and failure to comply with task instructions, leaving 190 participants.

Intelligence and executive function measures

Wechsler adult intelligence scale

Participants were administered the following subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS): vocabulary, similarities, block design, and matrix reasoning. Scores for each subtest were converted to scaled scores and summed to yield the following scores: total (sum across all four subtests), verbal (sum of vocabulary and similarities subtests), and performance (sum of block design and matrix reasoning subtests; task duration: approximately 50 min).

The sum of scaled scores for WAIS total, verbal, and performance measures were then converted to Wechsler Deviation Quotients (DQs) using the conversion table provided in Tellegen and Briggs (1967). A total of 190 participants contributed data to all WAIS analyses.

Raven’s advanced progressive matrices

Participants completed selected questions from the Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM; Raven, Raven, & Court, 1998), which serves as a measure of general fluid intelligence (gF; task duration: 15 min). Participants were administered 12 items selected from Set II, each of which required the participant to identify the answer option (out of eight provided options) that correctly completed a given pattern.

Participants’ accuracy on the RAPM served as the measure of performance for this task. Data from 2 participants were excluded from all analyses involving the RAPM due to at-chance levels of performance on this task. A total of 191 participants contributed data to all RAPM analyses.

Three-back verbal working memory task

Participants completed a three-back working memory task in which they were presented with words in a serial fashion (task duration: approximately 7 min). Participants were instructed to make a response when a presented word was the same word that had been presented three stimuli ago. Participants’ accuracy (percent correct), d′, and mean RT (only for correct trials) served as measures of performance on this task.

Data from 8 participants were removed from all analyses involving the three-back task due to performance at chance levels or below (e.g., negative d′ values). A total of 184 participants contributed data to all three-back task analyses.

Task-switching paradigm

Participants completed a number–letter task (adapted from Rogers & Monsell, 1995), designed to assess participants’ ability to switch between different task sets (task duration: approximately 8 min). Both a letter and a number were presented on each trial. If the letter and number appeared in blue, participants were instructed to make a consonant/vowel judgment for the letter by pressing one of two labeled keys. If the letter and number appeared in orange, participants were instructed to make an odd/even judgment for the number by pressing one of two labeled keys.

To control for processing speed, a regression was performed in which RTs from switch trials were regressed on RTs from no-switch (repeat) trials. The residuals from this regression were used as a measure of task-switching difficulty. Data from 3 participants were excluded from all analyses involving the task-switching paradigm, because their RT difference scores for switch and no-switch trials (i.e., the RT switch cost) were further than three standard deviations from the mean RT switch cost across participants. Additionally, 2 participants were excluded from all task-switching analyses, due to missing data. A total of 188 participants contributed data to all task-switching analyses.

Personality measures

Big five aspect scales

Participants completed the Big Five Aspects Scales (BFAS) personality questionnaire (DeYoung, Quilty, & Peterson, 2007) (task duration: approximately 6 min). The BFAS personality questionnaire assesses the following two aspects of each Big Five personality domain: neuroticism (volatility, withdrawal), agreeableness (compassion, politeness), conscientiousness (industriousness, orderliness), extraversion (enthusiasm, assertiveness), and openness/intellect (openness, intellect). The BFAS includes a total of 100 items, with 10 items per aspect. A total of 190 participants contributed data to all BFAS analyses.

NEO openness to experience scale

Participants completed the NEO Openness to Experience scale (task duration: approximately 4 min). This scale assesses the following six facets of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI–R) personality trait of openness (Costa & McCrae, 1992), with eight items per facet: actions (“openness to new experiences on a practical level”), aesthetics (“appreciation of art and beauty”), fantasy (“receptivity to the inner world of imagination”), feelings (“openness to inner feelings and emotions”), ideas (“intellectual curiosity”), and values (“readiness to reexamine own values and those of authority figures”). A total of 193 participants contributed data to all analyses involving the NEO Openness to Experience scale.

Results

We first report results from the verb generation task and then its relationships with creativity, intelligence, personality, and a creativity factor. Descriptive statistics for all creativity measures described above are provided in Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all other measures are provided in the online Supplementary Materials: Table S1 (intelligence and executive function), and Table S2 (personality). For the CAQ, divergent thinking tasks, story-writing task, and Torrance figural tests, raw scores are provided in Table 1. However, all analyses employed transformed values for these measures (log CAQ scores; sum of z-scores for divergent thinking, story-writing tasks, and Torrance figural tests).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for creativity measures

| Measure | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verb Generation Task | |||

| Cued RT | 3,649 | 869 | 1,274–5,765 |

| Uncued RT | 2,791 | 649 | 1,056–5,238 |

| Cued semantic distance | 0.76 | 0.06 | 0.64–0.90 |

| Uncued semantic distance | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.63–0.81 |

| Divergent Thinking Task | |||

| Total score | 95.12 | 32.62 | 26–217 |

| Flexibility | 36.18 | 9.93 | 9–69 |

| Originality | 26.16 | 14.40 | 3–79 |

| Fluency | 32.78 | 10.22 | 9–73 |

| Story Writing Task | |||

| Total score | 18.32 | 5.55 | 5.33–31 |

| Overall creativity | 4.28 | 1.39 | 1–7 |

| Descriptiveness | 4.21 | 1.35 | 1–7 |

| Semantic flexibility | 3.68 | 1.44 | 1–7 |

| Humor | 2.91 | 1.36 | 1–6.3 |

| Emotiveness | 3.23 | 1.25 | 1–6.7 |

| Torrance Figural Tests | |||

| Total score | 40.43 | 15.40 | 0–82 |

| Flexibility | 2.72 | 1.27 | 0–5.67 |

| Originality | 3.75 | 1.82 | 0–8 |

| Fluency | 5.78 | 2.61 | 0–12 |

| Elaboration | 20.56 | 9.51 | 0–54.33 |

| Criterion-referenced measures | 7.61 | 3.03 | 0–13.33 |

| Latent Inhibition Task | |||

| Latent inhibition score (RT Difference) | 147 | 240 | −430–782 |

| CAQ Total Score | 21.73 | 17.14 | 0–102 |

Note. CAQ: Creative Achievement Questionnaire. Reaction times (RTs) are given in milliseconds.

Verb generation task

We scored the verb generation task in terms of semantic distance and RT. Reliabilities were calculated for the mean semantic distance values and RTs for each mini-block of two consecutively presented cued and uncued nouns. Reliability for semantic distance values in the cued condition was high (α = .78); however, reliability for semantic distance values in the uncued condition was lower (α= .40). Reliabilities were high for mean RTs in both cued (α = .88) and uncued (α = .86) conditions.

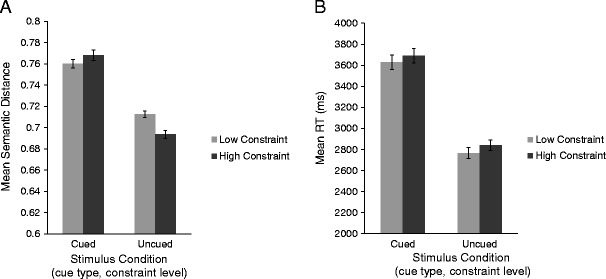

Participants’ mean semantic distance values were submitted to a 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA, with the two within-subjects factors of cue type (cued, uncued) and constraint level (high, low) (see Fig. 1a). As was predicted, a main effect of cue type was found, F(1, 182) = 172.1, p < .001, partial η 2 = .486, due to the higher semantic distance values for cued than for uncued items. That is, when cued to respond creatively, participants produced verbs that were more semantically distant than when not so cued.

Fig. 1.

Performance on verb generation task by noun cue type (cued, uncued) and noun constraint level (low, high) in terms of a mean semantic distance and b mean reaction times (RTs)

A marginally significant main effect of constraint level was found, F(1, 182) = 3.2, p = .07, partial η 2 = .017, due to a trend toward higher semantic distance values for verb responses to low-constraint nouns, as compared with high-constraint nouns. Interestingly, a cue type × constraint-level interaction effect was present, F(1, 182) = 24.8, p < .001, partial η 2 = .120. That is, the constraint level of the noun had differential effects on the magnitude of the semantic distance value for the generated verb response, depending on whether the noun was cued or uncued. For uncued nouns, high-constraint nouns prompted more similar verb responses (smaller semantic distance values). In contrast, for cued nouns, high-constraint nouns yielded more dissimilar verb responses (higher semantic distance values). Although we did not anticipate this effect, a possible explanation is that because higher constraint nouns are more easily associated with a common verb response, it may, in turn, be easier to generate an uncommon response for these nouns simply by choosing anything except the first word that comes to mind.

We also submitted participants’ mean RTs to the same 2 × 2 (cue type × constraint level) repeated measures ANOVA (see Fig. 1b). A main effect of cue type was found, F(1, 174) = 239.7, p < .001, partial η 2 = .579, with longer RTs in the cued than in the uncued condition. A main effect of constraint level was also found, F(1, 174) = 8.3, p < .01, partial η 2 = .045, with longer RTs for the high-constraint than for the low-constraint condition. No interaction was present, F = 0.09, p = .77, partial η 2 = 0.

Because responding at random is not the same as responding creatively, we sought to assess random responding as best we could. The instructions placed some constraint on the responses: The words said out loud were required to be a specific part of speech (verbs). Nonetheless, a verb generated at random may be semantically distant from a given noun and, as such, is not necessarily creative. Assessment of the appropriateness of a given response is nontrivial, due to the inability of experimenters to know how a verb response might be related to a noun for any given participant. Nonetheless, to better suggest that our findings are not driven by merely random responding, we conducted an additional set of analyses in which we screened participants’ responses for semantic appropriateness, excluding both any responses that appeared to be semantically unrelated to the presented noun and those that only 1 participant had generated. This identified only 0.6 % of all responses, suggesting that participants typically were generating semantically appropriate responses. Furthermore, exclusion of these responses led to a pattern of results very similar to those reported below. Due to the small percentage of these types of responses and the fact that their exclusion did not significantly impact our findings, we have retained them in our analyses.

Relation to creativity measures

Correlations between semantic distance on the verb generation task and all creativity measures are presented in Table 2. In brief, we found that semantic distance values in the cued, but not the uncued, condition significantly predicted participants’ performance on many of the measures—including creative cognition, production, and achievement—strongly validating the task as a measure of creative cognition.

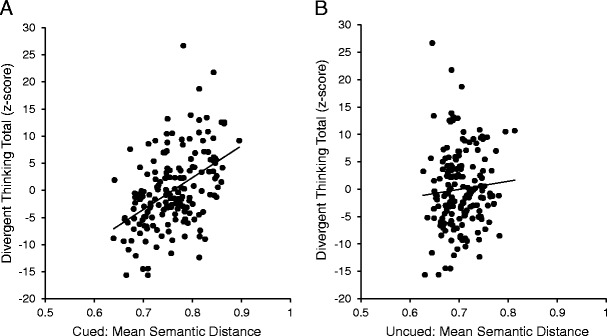

Divergent thinking

Correlations between participants’ semantic distance values and their divergent thinking task performance are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2. Participants’ semantic distance values were a significant predictor of their divergent thinking total scores in the cued condition (ß = .46, p < .001), but not in the uncued condition (ß = .03, p = .72). Cued semantic distance values explained unique variance in divergent thinking total scores after accounting for the variance explained by uncued semantic distance values, ΔR 2 = .21, ΔF(1, 170) = 46.39, p < .001. Cued semantic distance values also significantly predicted divergent thinking performance for each dimension: flexibility (ß = .41, p < .001), fluency (ß = .44, p < .001), and originality (ß = .47, p < .001). However, uncued semantic distance values did not significantly predict divergent thinking performance for any of these dimensions (ps > .21).

Fig. 2.

Correlations between verb generation task semantic distance values and divergent thinking total scores for a cued nouns and b uncued nouns. Lines shown indicate linear regression lines. Corresponding Pearson r coefficients are provided in Table 2

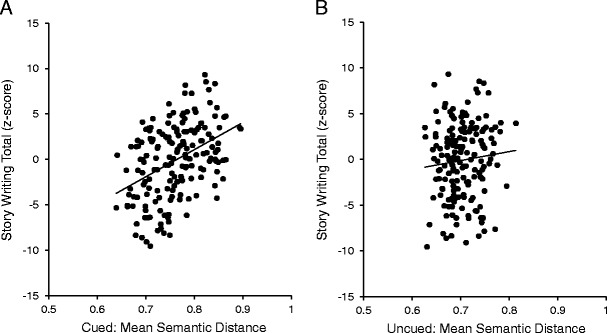

Story writing

After controlling for story-writing word counts, semantic distance values significantly predicted story-writing total scores in the cued (ß = .31, p < .001) but not in the uncued (ß = .01, p = .90) condition (see Fig. 3). After accounting for the variance explained by story-writing word counts and uncued semantic distance values, cued semantic distance values still explained unique variance in story-writing total scores, ΔR 2 = .09, ΔF(1, 169) = 32.12, p < .001. Thus, participants who generated more semantically distant responses in the cued condition also generated more creative stories in the story-writing task.

Fig. 3.

Correlations between verb generation task semantic distance values and story-writing total scores (zero-order correlation) for a cued nouns and b uncued nouns. Lines shown indicate linear regression lines. Pearson r coefficients (controlling for story-writing word count) are provided in Table 2

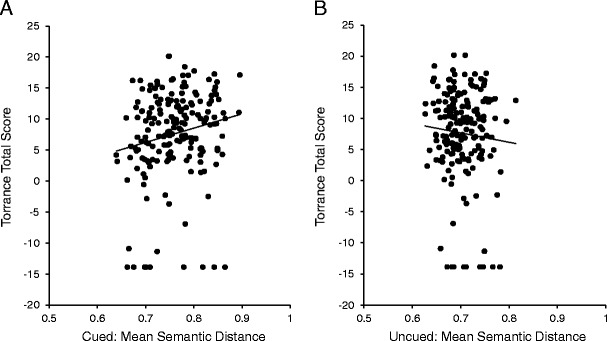

Torrance figural test

Semantic distance values in the cued (ß = .19, p < .05), but not the uncued (ß = −.10, p = .19) condition significantly predicted Torrance total scores (see Fig. 4). After accounting for the variance explained by uncued semantic distance values, cued semantic distance values explained a significant proportion of unique variance in Torrance total scores, ΔR 2 = .04, ΔF(1, 180) = 6.68, p < .05. These results indicate that participants who generated more semantically distant responses in the cued condition of the verb generation task also drew more creative figures in the Torrance tests.

Fig. 4.

Correlations between verb generation task semantic distance values and Torrance total scores for a cued nouns and b uncued nouns. Lines shown indicate linear regression lines. Corresponding Pearson r coefficients are provided in Table 2

Latent inhibition

Replicating the main finding from Evans et al. (2007), our participants demonstrated robust LI as a group. Participants had longer RTs to the preexposed (M = 1,331, SD = 182) than to the nonpreexposed (M = 1,184, SD = 261) stimuli, t(175) = 8.12, p < .001, d = 0.65. However, cued semantic distance values did not significantly predict individual participants’ residual RT effects for the LI task (ß = −.09, p = .23). Uncued semantic distance values were marginally related (ß = −.14, p = .08) (see Table 2). Neither of these results was expected.

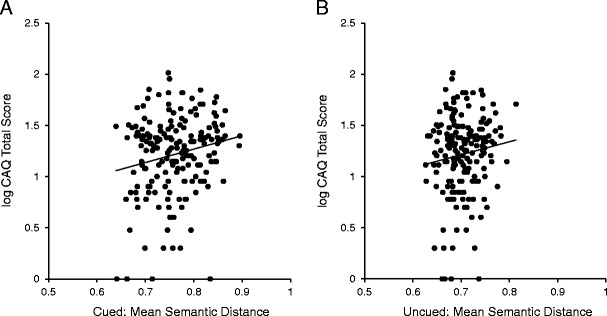

Creative achievement

Semantic distance values significantly predicted participants’ log CAQ scores in the cued condition (ß = .18, p < .05), but not in the uncued condition (ß = 0.10, p = .19) (see Fig. 5). Cued semantic distance scores explained a significant portion of log CAQ scores after accounting for variance explained by uncued semantic distance scores, ΔR 2 = .03, ΔF(1, 177) = 5.84, p < .05. Thus, participants with higher levels of creative achievement tended to produce more creative verb responses.

Fig. 5.

Correlations between verb generation task semantic distance values and log CAQ total scores for a cued nouns and b uncued nouns. Lines shown indicate linear regression lines. Corresponding Pearson r coefficients are provided in Table 2

We also examined the relationship between participants’ scores on individual CAQ domains and their semantic distance values for the different conditions of the verb generation task in an exploratory analysis (see Table 3). For cued nouns, significant positive correlations were found between participants’ semantic distance values and log-transformed CAQ scores in the science and visual art domains. For uncued nouns, a significant positive correlation was found between participants’ semantic distance values and log-transformed CAQ scores in the creative writing domain.

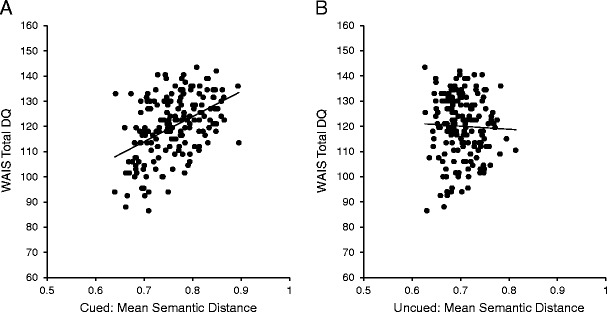

Relation to intelligence

Greater semantic distance in the cued condition was positively related to intelligence and executive function. Correlations between performance on the verb generation task and intelligence and executive function are presented in Table 4; correlations among the intelligence and executive function measures are presented separately in Table S3 in the online Supplementary Materials.

Semantic distance values predicted participants’ WAIS total scores in the cued (ß = .47, p < .001), but not the uncued (ß = −.09, p = .17), condition (see Fig. 6). Cued semantic distance values explained unique variance in WAIS total scores after accounting for the variance explained by uncued semantic distance values, ΔR 2 = .22, ΔF(1, 177) = 49.98, p < .001. Additionally, cued semantic distance values significantly predicted WAIS verbal (ß = .39, p < .001) and performance (ß = .42, p < .001) scores. Uncued semantic distance values did not predict WAIS verbal scores (ß = −.03, p = .63) and only marginally predicted WAIS performance scores (ß = −.12, p = .08).

Fig. 6.

Correlations between verb generation task semantic distance values and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) total deviation quotients (DQs) for a cued nouns and b uncued nouns. Lines shown indicate linear regression lines. Corresponding Pearson r coefficients are provided in Table 4

Cued semantic distance was a positive predictor of RAPM accuracy (ß = .46, p < .001). Unexpectedly, uncued semantic distance values were a negative predictor of RAPM accuracy (ß = −.21, p < .01). After accounting for the variance explained by uncued semantic distance values, cued semantic distance values explained unique variance in RAPM accuracy, ΔR 2 = .21, ΔF(1, 179) = 49.28, p < .001. These results indicate that participants with higher intelligence scores on the WAIS and RAPM generated more unusual verb responses to cued nouns.

Cued semantic distance values predicted three-back working memory accuracy (ß = .28, p < .001). These results indicate that participants who had higher accuracy on the three-back task also tended to generate more creative responses in the verb generation task. However, no significant relationships were found with d′ or mean RTs for the three-back task, or task-switching performance (ps > .15). Uncued semantic distance values were a significant negative predictor of three-back accuracy (ß = −.28, p < .001) and d′ (ß = −.23, p < .01). No significant relationships were found with three-back mean RT or task-switching performance (ps > .29).

Relation to creativity, controlling for intelligence

We sought to further clarify the relationships between creativity measures after controlling for intelligence. Although these relationships were reduced in strength, most remained significant; the Torrance Figural Test and CAQ were no longer so. These results suggest that although intelligence can account for some of the shared variance between performance on the verb generation task and other creativity measures, a significant relationship remains, over and above intelligence.

Semantic distance predicted divergent thinking total scores after controlling for both RAPM accuracy and WAIS total DQ scores: cued (ß = .33, p < .001), but not uncued (ß = .05, p = .46). Additionally, after accounting for uncued semantic distance, RAPM accuracy, and WAIS total DQ scores, it was still the case that cued semantic distance values explained unique variance in divergent thinking total scores, ΔR 2 = .08, ΔF(1, 167) = 19.11, p < .001. Cued semantic distance values also predicted performance in each dimension of the divergent thinking tasks after controlling for these variables: flexibility (ß = .24, p < .01), fluency (ß = .30, p < .001), and originality (ß = .38, p < .001). Uncued semantic distance values remained a nonsignificant predictor of all divergent thinking dimensions (ps > .13).

Semantic distance predicted story-writing total scores after controlling for RAPM accuracy and WAIS total DQ scores, as well as story-writing word counts: cued (ß = .17, p < .01), but not uncued (ß = .05, p = .39). Additionally, after accounting for the variance explained by these variables as well as uncued semantic distance values, cued semantic distance values explained a significant proportion of variance in story-writing total scores, ΔR 2 = .02, ΔF(1, 163) = 7.35, p < .01.

Cued semantic distance values no longer predicted Torrance total scores after controlling for RAPM accuracy and WAIS total DQ scores (ß = .06, p = .47). Thus, in contrast to the relationships between cued semantic distance values and performance on the divergent thinking and story-writing tasks, this result suggests that the shared variance between performance on the verb generation and Torrance tests can primarily be explained by measures of intelligence. Uncued semantic distance values remained a nonsignificant predictor after controlling for RAPM accuracy and WAIS total DQ scores (ß = −.06, p = .40).

Participants’ CAQ scores were not reliably predicted by either cued (ß = .12, p = .17) or uncued (ß = .10, p = .17) semantic distance values, after controlling for RAPM accuracy and WAIS total DQ scores.

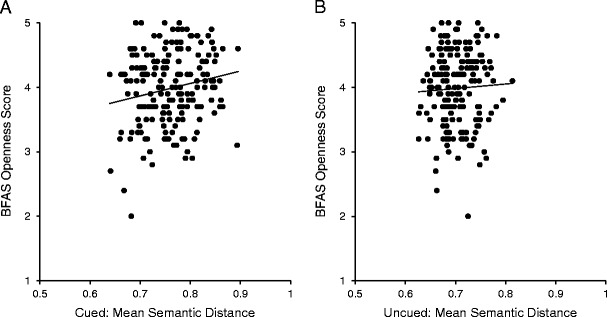

Relation to personality

Correlations between participants’ performance on creativity measures and their BFAS and NEO openness personality scores are presented in Table 5. Correlations between BFAS and NEO personality scores are presented separately in Table S4 in the online Supplementary Materials. As is indicated in Table 5, correlations were found between personality scores (as predicted for the dimension of openness) and several creativity measures. Here, we focus on relationships between personality and verb generation performance.

Cued (ß = .19, p < .05), but not uncued (ß = .02, p = .77), semantic distance values significantly related to participants’ openness scores (see Fig. 7). Cued semantic distance values explained a significant proportion of variance in openness scores after controlling for the variance explained by uncued semantic distance values, ΔR 2 = .03, ΔF(1, 177) = 6.19, p < .05. As is shown in Table 5, cued semantic distance values also predicted several facets of the NEO Openness to Experience scale. These results suggest that participants with higher openness scores generated more creative (and more semantically distant) verb responses primarily in the cued condition.

Fig. 7.

Correlations between verb generation task semantic distance values and Big Five Aspects Scales (BFAS) openness scores for a cued nouns and b uncued nouns. Lines shown indicate linear regression lines. Corresponding Pearson r coefficients are provided in Table 5

As is presented in Table 5, no significant relationship between cued semantic distance and intellect was evident. In exploratory analyses reported for descriptive purposes, negative correlations were found between cued semantic distance and assertiveness, orderliness, and industriousness. For uncued semantic distance, there was a weaker negative correlation between uncued values and the BFAS aspect of politeness and a positive correlation with assertiveness. We note that these correlations could well be spurious, given that we did not control for multiple comparisons; we simply describe the obtained effect sizes.

Relation to a creativity factor

As was anticipated, our measures of creative cognition, creative production, and creative achievement were positively correlated. To assess the factor structure, we used principal-axis factoring, with direct oblimin rotation (Δ = 0) to allow for correlated factors, on total scores for the following creativity task measures: divergent thinking, story writing, Torrance figural tests, and the CAQ. Although marginally significantly associated with uncued semantic distance scores, LI task performance did not significantly correlate with any other measures used in this study. This was surprising, since we had expected LI performance to correlate with other measures of creativity, as well as the personality trait of openness to experience. However, the association between LI and measures of creativity and openness to experience has been inconsistent in the literature (e.g., Burch et al.,2006; Wuthrich & Bates, 2001). As a result, we chose to exclude the LI task from our factor analysis. Only one factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0 was obtained. This factor accounted for 42.46 % of the variance; we refer to it as a creativity factor. The factor loadings were the following: divergent thinking, 0.77; story writing, 0.49; Torrance figural tests, 0.45; and the CAQ, 0.23.

We next performed a multiple regression analysis with cued and uncued semantic distance variables from the verb generation task included as predictors of creativity (factor scores). As might be expected from the relationships reported in the Relation to Creativity Measures section, cued semantic distance predicted creativity (ß = .50), whereas uncued did not (ß = .03). Cued semantic distance predicted a variance in creativity after accounting for uncued semantic distance, ΔR 2 = .25, ΔF(1, 160) = 53.88, p < .001.

Because several of the creativity measures were significantly correlated with both intelligence and personality scores, we next investigated the discriminant validity of our cued creativity variant of the verb generation task. A multiple regression was performed, controlling for the following variables: WAIS total scores, RAPM accuracy, and BFAS openness scores. Even after controlling for these intelligence and personality and uncued semantic distance values, cued semantic distance values remained a significant predictor (ß = .30, p < .001) and explained unique variance in participants’ creativity factor scores, ΔR 2 = .07, ΔF(1, 156) = 17.66, p < .001.

In sum, the factor-analysis results indicate that the cued condition of our version of the verb generation task is quite strongly associated with a creativity factor, in the sense of the variance common across a diverse battery of creativity measures (ß = .50). Furthermore, this relationship was not entirely explained by intelligence or personality.

Discussion

The data strongly suggest that individual differences in creative cognition can be inferred accurately from single-word utterances—in our case, verbs spoken aloud in response to visually presented nouns. Greater semantic distance of the noun–verb pairs was correlated positively with a creativity factor derived from a battery of measures, including verbal, nonverbal, and achievement-based measures.

Here, we highlight four main aspects of the results. First, semantic distance was higher in the cued than in the uncued condition, suggesting that untrained participants were able to modulate their word production effectively, and do so on demand. Second, participants’ semantic distance values in the cued condition predicted performance across diverse measures of creativity, even after controlling for intelligence (which itself should correlate positively with creativity, and did so in our data). Third, cued semantic distance scores significantly predicted creativity factor scores, representing the shared variance across our diverse creativity measures, greatly reducing the influence of task- or method-specific variance. Furthermore, this relationship remained significant after controlling for both intelligence and self-reported openness personality scores. Fourth, we believe that the task is suitable for behavioral and brain-imaging studies in diverse populations, including ERP, MEG, and fMRI. Below, we consider the advantages and limitations of our novel verb generation task with respect to other creativity measures, including the contribution of intrinsic and extrinsic factors in impacting creative performance.

Verb generation task as a measure of creative cognition

As was noted in the Introduction, there are several measures of creativity that have been used extensively in the creativity literature. The verb generation task, a classic cognitive neuroscience measure of language production and semantic processing abilities, can be adapted to serve as a measure of creative abilities, with certain advantages over existing measures of creativity. Although the tasks mentioned above assess participants’ creative abilities and are popular indices of individual differences in creativity, they tend to rely on assessment of creative products by groups of raters. Semantic distance values, derived using LSA techniques, serve as a strongly objective measure of semantic distance that is not subject to the potentially shared biases of raters measures of creativity. Importantly, LSA values can be derived for different populations, to better reflect a shared language environment. For assessing creativity, LSA values are probably meaningful only for comparisons within a group sharing a common language background.

Additionally, our use of semantic distance values as a metric of creativity improves upon previous studies that have attempted to uncover the mechanisms underlying processing of distant semantic relationships. In a neuroimaging study of the neural correlates of generating typical versus unusual semantic associations, Seger et al. (2000) had participants perform a verb generation task in which they generated either the first verb that came to mind or a verb that was related to the noun in an unusual way, in alternating blocks. Since no overt responses were collected, the sole measure of behavioral performance consisted of efficiency in responding, or RTs. Similar to our findings, Seger et al. found that participants took significantly longer to generate unusual verbs to presented nouns. Additionally, the authors found increased neural activity in the right prefrontal cortex associated with the generation of unusual verbs. Although these findings are certainly intriguing, they also raise several questions. Since overt responses were not collected, it is not possible to determine either the degree of novelty or the appropriateness of participants’ responses. Furthermore, RTs serve as merely a crude measure of creative abilities (Fink et al., 2007). Thus, our cued creativity verb generation task offers a more objective, corpus-based measure of creative performance that captures the degree of novelty of participants’ responses in brief samples of observed behavior and serves as a reliable index of individual differences in creativity.

We have also validated our novel cued creativity verb generation task by demonstrating its relationship with several different measures of creativity. The present study makes a unique contribution to the creativity literature in terms of both the diversity of measures in our battery that assess different aspects of creativity and the investigation of the role of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors in impacting creative performance within the same large sample of participants. There has been some resistance to the notion that creativity is a monolithic construct and, in particular, that creativity is synonymous with divergent thinking (see Arden, Chavez, Grazioplene, & Jung, 2010; Dietrich, 2007). In order to more effectively capture the complexity of the processing mechanisms underlying creativity, we included a variety of measures in our battery of creative tasks in order to assess different facets of creativity. The tasks in this battery included measures of divergent thinking, story-writing ability (i.e., verbal creative production), Torrance figural test performance (i.e., nonverbal creative production), and creative achievement (self-reported). By demonstrating significant relationships between performance in the cued condition of the verb generation task and each of these measures, we have shown that “thin slices” of creativity from our task appear to assess a similar processing mechanism that is invoked by each of these different measures. Indeed, the diversity of these measures greatly mitigates any concern that it is merely superficial similarities that are driving these relationships. Notably, a factor analysis revealed that performance on the various measures loaded onto a single factor, thus suggesting that despite the considerable differences across these measures, they also assess a common element—presumably, creativity. Furthermore, this common creative ability, representing the shared variance across these diverse measures, was significantly related to cued, but not uncued, performance on the verb generation task. Although this study was not designed to directly test the question of whether creative abilities are domain specific or domain general in nature, our results suggest that there appears to be some degree of domain generality across the measures in our creativity battery (see Chen et al., 2006; Plucker & Beghetto, 2004). This finding, however, does not preclude the possibility of additional domain-specific creativity abilities (e.g., Baer, 1998; Silvia, Kaufman, & Pretz, 2009).

A key advantage of our novel verb generation task is its suitability for use in neuroimaging paradigms. For the main effect of cue type, we performed a post hoc power analysis using G*Power 3.1.7 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). Input parameters consisted of the following: effect size [f(U) = 0.972, derived by G*Power 3.1.7 from our observed effect size of partial η 2 = .486], α error probability (= .05), total sample size (= 20), number of groups (= 1), number of measurements (= 2, reflecting cued and uncued trial types), and nonsphericity correction ε (= 1). We found that with 20 subjects, one would have 98 % power to detect the observed effect size of partial η 2 = .486. Since neuroimaging studies typically use sample sizes around 20 subjects, the cued creativity verb generation task serves as a paradigm that is suitable and convenient for fMRI studies.

The role of intrinsic and extrinsic factors in impacting creative performance

Our results indicate that both intrinsic and extrinsic factors impact creative performance. Regarding the role of intrinsic factors, we have shown that intelligence and openness personality scores are related to individual differences in the cued condition of the verb generation task, as well as across several of the other measures in our creativity test battery. These findings support those observed previously in the creativity literature (see Barron & Harrington, 1981). Furthermore, our inclusion of intelligence and openness personality scores as covariates allowed us to establish the discriminant validity of the cued creativity verb generation task (see Arden et al., 2010).

Importantly, our results go beyond these findings to demonstrate that even after controlling for these intrinsic factors, the extrinsic factor of an explicit “be creative” cue accounts for a significant portion of the variance in individual differences in creative abilities. Furthermore, we have shown that the impact of this explicit cue on creative performance can be observed in brief samples of observed behavior. Our findings thus suggest that intrinsic factors do not account for the entirety of variability in creative performance. Additionally, our finding of an important role for cue type in impacting creative performance observable in “thin slices” of behavior has implications for the potential to train and foster creativity in our students. Since intelligence and personality do not appear to account for all of the variability in creative abilities across individuals, this holds promise for the potential use of extrinsic factors to train participants to produce more creative responses on demand. In demonstrating that an explicit “be creative” cue leads to enhanced creative performance, our findings support the conjecture of Harrington (1975) that explicit instructions are essential for allowing participants to demonstrate their maximal performance or “optimal functioning” (Simonton, 2000). As such, our findings hold promise for the use of explicit creativity cues in educational settings in order to develop creativity skills in students.

Limitations of the present study

Due to our primary interest in individual differences in creativity, we chose to administer the words in a single order with the same assignment of the noun stimuli to the cued or uncued conditions. This is optimal for avoiding confounding individual differences with differences in the word sets. If we had been most interested in the effect of the cue, counterbalancing the assignment of nouns to the cued or uncued condition would have been ideal (to ensure that any differences between cued and uncued conditions were not driven by differences in the word sets). We took care to ensure that there were no differences in average constraint level between the cued and uncued conditions. Thus, it is unlikely that stimulus assignment to cued and uncued conditions was driving our results of main interest—namely, the correlations of semantic distance in the cued condition with other aspects of creative cognition.

The lack of correlations in the uncued condition should be interpreted with some caution. The instructions we gave to participants were fairly general and did not strongly constrain their interpretation of what creativity is or how they should respond. It is possible that, due to demand characteristics of the situation, participants may have interpreted the uncued condition as an opportunity to give typical responses, even though they were not explicitly instructed to do so. To speculate, it seems likely that participants reserved their creative abilities for the cued condition, adopting a strategy of simply providing the first verb that came to mind in the uncued condition. Consistent with this, although we observed high reliability for semantic distance values in the cued condition, uncued semantic distance values were associated with lower reliability. Importantly, however, these possible interpretations of the uncued condition do not greatly influence the impact of our main findings, in which participants’ responses in the cued condition were significantly related to their performance across a diverse battery of creativity measures. In follow-up work, it could be interesting to test participants in a no-cue condition of the task, without a cued condition of any sort. One could then further test whether individual differences in participants’ natural tendency to produce creative or unusual responses also correlates with variation in performance on other measures of creativity. Overall, our results provide a significant first step in demonstrating that a classic cognitive neuroscience measure can be adapted to serve as a reliable and valid index of variation in creative abilities.

Conclusions

In sum, we have demonstrated that individual differences in creativity can indeed be reliably assessed from thin slices (i.e., brief samples) of behavior, such as single-word utterances. Our creativity-cued verb generation task can be used to provide a quantitative measure of semantic distance of verb associate responses, which is, in turn, a reasonably strong correlate of creative performance. Participants can produce more creative responses when cued to do so, and their performance on our task is related to their creative performance across a diverse battery of measures. Our findings inform the prior literature on creative cognition and suggest potential future uses for the cued creativity verb generation task to assess individual differences in creativity in diverse populations, as well as in brain-imaging studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 223 kb)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF REC 0634025 and NSF DRL 0644131). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. We thank Joseph Kim, Michael Cohen, Kathleen Muller, Rebecca Fine, Jessica Cole, Anne Saulin, Prabin Subedi, Claire Horrell, and Ruhi Mehta for their assistance.

Appendix

Footnotes

Ranjani Prabhakaran and Adam E. Green are dual first authors, contributed equally to this work

References

- Abraham A, Windmann S. Creative cognition: The diverse operations and the prospect of applying a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Methods. 2007;42:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amabile TM. Effects of external evaluation on artistic creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:221–233. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.37.2.221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amabile TM. Social Psychology of Creativity: A Consensual Assessment Technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;43:997–1013. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ambady N, Rosenthal RJ. Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:256–274. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]