SUMMARY

Hermes is a member of the hAT transposon superfamily which has active representatives, including McClintock's archetypal Ac mobile genetic element, in many eukaryotic species. The crystal structure of the Hermes transposase-DNA complex reveals that Hermes forms an octameric ring organized as a tetramer of dimers. While isolated dimers are active in vitro for all the chemical steps of transposition, only octamers are active in vivo. The octamer can provide not only multiple specific DNA-binding domains to recognize repeated subterminal sequences within the transposon ends, which are important for activity, but also multiple non-specific DNA binding surfaces for target capture. The unusual assembly explains the basis of bipartite DNA recognition at hAT transposon ends, provides a rationale for transposon end asymmetry, and suggests how the avidity provided by multiple sites of interaction could allow a transposase to locate its transposon ends amidst a sea of chromosomal DNA.

INTRODUCTION

Transposable elements and their inactive remnants populate the genomes of almost all organisms that have been examined (Biémont, 2010), and genes encoding the associated transposase proteins are the most abundant genes in nature (Aziz et al., 2010). Amongst eukaryotes, the portion of the genome arising from transposable elements ranges from <1% for the honeybee (Honeybee Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2006) to >85% in maize (Schnable et al., 2009). Although they are often silenced, the existence of active transposons, particularly among plants and insects, suggests that their continued mutagenic potential may be beneficial to their hosts (Huang et al., 2012). Furthermore, domesticated transposases can be the source of vital proteins such as the Recombination Activating Protein-1 (RAG1), an essential component of the adaptive immune system which is believed to have originated from a Transib DNA transposase (Kapitonov and Jurka, 2005). Thus, understanding how transposon movement and amplification have changed genomes is intimately linked to understanding how genomic organization and remodeling have driven evolution.

Transposable elements are divided into two classes depending on whether they use RNA or DNA intermediates to move. Approximately twenty superfamilies of eukaryotic DNA transposons have been identified and classified based on the amino acid sequences of their transposases (Wicker et al., 2007; Yuan and Wessler, 2011). One of the largest superfamilies is comprised of the hAT transposons, named after three of the earliest discovered active transposons: hobo from Drosophila melanogaster (Streck et al., 1986; Calvi et al., 1991), Ac from maize (McClintock, 1950), and Tam3 from the snapdragon (Hehl et al., 1991).

Only a few hAT transposons and their transposases have been studied in detail, yet it seems likely that they share common mechanistic and structural features (reviewed in Rubin et al., 2001; Arensburger et al., 2011). Despite very limited sequence similarity, they have a common genetic organization in which a single ORF encoding the transposase is flanked by hundreds of bp of non-coding sequence. These regions 5’ and 3’ of the transposase gene relative to its direction of transcription are the transposon Left End (LE) and Right End (RE), respectively, and they terminate in short, ~11-24 bp Terminal Inverted Repeats (TIRs). hAT transposases are ~600-800 amino acid multidomain proteins that catalyze transposon excision from one location and insertion into a new one using a cut-and-paste mechanism, integrating their transposons with characteristic 8 bp target site duplications (TSD). hAT transposases do not appear to have mechanistic analogs among prokaryotes (Hickman et al., 2010), as they excise by generating double-strand breaks accompanied by the formation of DNA hairpins on flanking DNA, the same mechanism used by RAG1/2 proteins responsible for the generation of vertebrate antigen receptors (reviewed in Schatz and Swanson, 2011).

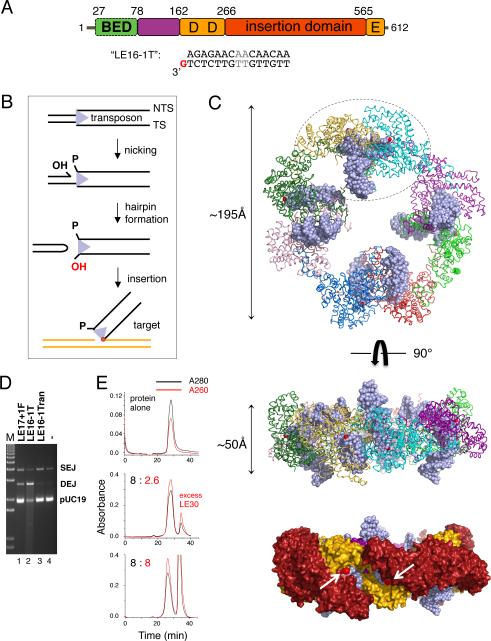

The only available structure of a hAT transposase, a portion of the Hermes transposase from the house fly Musca domestica (Warren et al., 1994), revealed an RNaseH-like catalytic domain interrupted by a large [.alpha]-helical “insertion domain”, and an N-terminal intertwined dimerization domain (Hickman et al., 2005; Figure 1A). Together, these domains catalyze the chemical steps of DNA nicking, hairpin formation, and DNA strand transfer that comprise hAT transposition (Figure 1B; Zhou et al., 2004).

FIGURE 1. Hermes overview and structure.

(A) Domain organization and “LE16-1T” DNA used for structure determination. BED domain is in green, intertwined dimerization domain in purple, RNaseH-like catalytic domain in orange, and insertion domain in red. The metal ion binding residues of the DDE motif (D180, D248, E572) are marked. Two AT bp in grey differ between the Left End (LE) and Right End (RE) 17mer terminal inverted repeats (TIRs). (B) Reaction scheme for hAT transposition. TS: transferred strand. NTS: Non-transferred strand. (C) Structure of Hermes79-612 bound to TIRs. In top and middle, each monomer is a different color, DNA is light blue, and red spheres mark the 3’-OH of each TS. In the bottom surface representation, domains are colored as in (A), and arrows point to the two 3’-OH groups (red spheres) within one dimer. (D) Strand transfer assay using pre-cleaved LE (28.6 nM) and Hermes 79-612 C519S (10 nM) at 30°C for 2 hr in standard buffer containing 150 mM NaCl. Lane 1: LE17 with one flanking 5’-phosphorylated base. Lane 2: oligonucleotide used for structural studies. Lane 3: randomized oligonucleotide of same length as LE16-1T. Lane 4: target plasmid pUC19 alone. SEJ: single-end joined products; DEJ: double-end joined products. The streak in lane 2 indicates repeated plasmid insertions, causing fragmentation. (E) Size exclusion chromatography analysis of DNA binding by full-length Hermes. Top: Hermes alone. Middle: Hermes and LE30 mixed in an 8:2.6 ratio. There is some unbound DNA, and the unsymmetric main peak suggests that both the complex and free Hermes exist under these conditions. Bottom: Hermes and LE30 mixed in an 8:8 ratio. Relative to the 8:2.6 ratio, the complex peak is unchanged in size and 280/260nm ratio, indicating that no more DNA has been bound, although the peak is more symmetrical. See also Figures S1 and S2, and Table S1.

The nucleoprotein assembly that carries out DNA transposition is known as a transpososome. To date, only one eukaryotic transpososome has been structurally characterized, that of the mariner Mos1 transposon (Richardson et al., 2009), and it employs a catalytic mechanism that does not involve hairpin intermediates (Dawson and Finnegan, 2003). Here, we report the structure and properties of the eukaryotic Hermes transpososome, providing insight into aspects of hAT transposition including transposon end recognition and the importance of subterminal repeats within hAT transposon ends.

RESULTS

The overall architecture of the Hermes transpososome

Complexes of Hermes79-612 and a 16mer oligonucleotide derived from the Hermes LE TIR were crystallized, and the X-ray structure solved by Single Isomorphous Replacement with Anomalous Scattering (SIRAS) at 3.4Å resolution using a Ta6Br12 derivative (Table S1; Figure S1A,B). The complex is an octameric ring of monomers in which each monomer is bound to one TIR DNA (Figure 1C). The ring is ~195Å in diameter, or almost twice that of a nucleosome core particle (Kornberg, 1977). The assembly is held together by alternating small and large interfaces: short domain-swapped helices at the periphery of the ring contributed by adjacent monomers alternate with an extensive interface projected towards the center of the ring formed by intertwined N-terminal dimerization domains from two monomers. The overall assembly is therefore a tetramer of dimers.

Within each dimer (one is circled in Figure 1C), two TIRs are oriented approximately perpendicular to each other. One DNA is bound such that its distal end points away from the plane of the ring and the other DNA end is more co-planar with the ring. This asymmetry that we observed in the crystal structure (see also Figure S1C,D) is a consequence of the small interface between the dimers at the outer edge of the ring. In the dimers, the TIRs point into a cleft on the rim of the ring that is of appropriate size and surface charge to bind target DNA. Thus, we have captured the state in which the ends of an excised transposon are bound and awaiting target capture.

The DNA used to obtain crystals is recessed by one nucleotide (nt) on the non-transferred strand (NTS), and binds more tightly than a blunt-ended 16mer LE TIR to Hermes79-612. It is also more readily inserted into target DNA than a comparable authentic reaction intermediate (Figure 1D), which has two more 5’ nt on the NTS. The observed 8:8 protein-to-DNA stoichiometry is a consequence of using a short TIR to facilitate crystallization, as complexes formed with a longer oligonucleotide containing the terminal 30 bp of the LE display the expected ~8:2 binding (Figure 1E). Binding of two transposon ends is a property of all DNA transpososomes that have been structurally characterized to date (Davies et al., 2000; Richardson et al., 2009; Montaño et al., 2012).

When the DNA-bound dimers within the octamer are compared with those of the apoprotein (Hickman et al., 2005), relative to the intertwined domain, the protein has unfurled and the RNaseH-like and insertion domains have swung out to accommodate the TIRs (Figure S1E). The intertwined dimerization domain is unchanged and can be superimposed with an rms of 0.56Å including all α-carbons. However, in such an alignment, the overall rms is 6.4Å over all α-carbons of residues 79-612 due mainly to catalytic and insertion domain movements and conformational changes within these domains.

Several lines of evidence indicate that full-length Hermes also forms an octamer. E. coli-expressed full-length Hermes elutes at a position on size exclusion chromatography (SEC) consistent with an octamer (Figure S2A), and static light scattering (SEC-MALS) results indicate a monodisperse protein of molecular mass 544,000 Da (calculated octamer molecular mass is 70,110 Da × 8 = 560,880 Da; Figure S2B). Solution X-ray scattering (SAXS; Rambo and Tainer, 2013) data acquired at three protein concentrations yield a molecular mass of 540±80 kDa, and a maximum assembly dimension of ~220Å. When an optimized model for the full-length octamer was generated using AXES (Grishaev et al., 2010), comparison of the scattering intensity profile of the best fitting solution with the experimental scattering data indicated that the data are consistent with a monodisperse octameric scattering particle (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2. The full-length Hermes octamer.

(A) Top: SAXS experimental scattering profile (black, with uncertainty values indicated by error bars) and scattering intensities of the best-fitting model of a full-length Hermes octamer (red). Bottom: Guinier region. (B) Class-average images from negatively-stained full-length Hermes. Top left: top view average of 303 particles. Top right: side-view average of 104 particles. Bottom panels show surface renderings of a density map generated from negatively stained particles, in top and side views. Scale bars, 50Å. (C) Modeled location of eight BED domains, in green. Each BED C-terminus (red) was constrained to be close to one of the observed Hermes N-termini. See also Figure S3.

Full-length Hermes expressed in eukaryotic cells such as budding yeast and Sf9 cells similarly forms a large multimeric species consistent with an octamer as judged by SEC (Figure S2C,D). Although we previously reported that full-length Hermes expressed in Sf9 cells is hexameric (Hickman et al., 2005), this was likely a misinterpretation of the preliminary data and our reliance on only one technique (SEC) for molecular weight estimation. Regardless of expression method, we have seen no evidence of subunit dissociation under different buffer conditions, with or without bound DNA, or an equilibrium between the octamer and any other multimeric state.

The form of Hermes used for crystallization lacks 78 amino acids at the N-terminus, which contains a BED-finger domain (Figure 1A; Aravind, 2000). BED domains have been proposed to bind DNA and to coordinate Zn2+ through a conserved CCHH or CCHC motif (Aravind, 2000). All hAT transposases possess a predicted BED domain, the vast majority of which are the CCHH type (Arensburger et al., 2011).

In the structure, the N-termini of all eight monomers are in the center of the ring, and it seems likely this is where the BED domains would reside. To test this hypothesis, we performed negative staining EM using purified full-length Hermes. The fields contained many particles of the appropriate dimensions for an octamer (Figure S3B) and these data were enhanced by picking these particles and performing image averaging (Figure S3C). Averaged top and side-views are shown in Figure 2B. The top view accurately reproduced the crystal structure when it was limited to the same resolution, but had additional positive density in the center, suggesting that this is where the BED domains are located; these features were confirmed in a 3D density map (Figure 2B). Indeed, eight BED domains can be readily modeled within the center of the octamer using the structure of a homology model generated by I-TASSER (Zhang, 2008) so that each BED C-terminus is close to and paired with an observed N-terminus (Figure 2C). In such a model, the BED domains cluster within the ring without steric clashes to either the rest of the protein or the TIRs.

Hermes-DNA interactions within the transpososome

The bound TIRs are essentially B-form DNA except at the active site where the minor groove is widened due to interaction with the α-helix that bears E572 of the DDE catalytic motif. Residues contributed by the three domains present in the crystallized form of Hermes participate in TIR binding (Figure 3A,B). Close to the TIR tip, a network of amino acids specifically recognize the first 5 bp; beyond those, we observe only one other base-specific interaction, that between base G11 and R149. Residues 585-588, located in the turn between the α-helix bearing E572 and the final helix of the protein contribute interactions within the minor groove. A second cluster of interactions more interior to the TIR tip occur in the major groove and involve residues in the region 138-149; most of these interactions are with the DNA phosphate backbone.

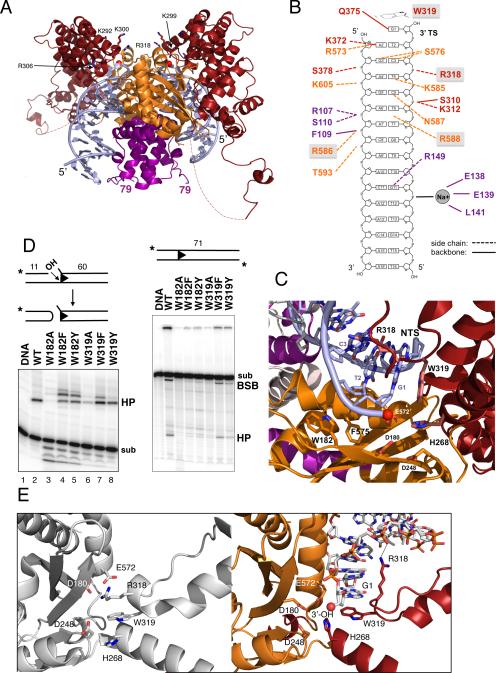

FIGURE 3. Hermes-DNA interactions.

(A) View of one dimer within the octamer. Red spheres indicate the 3’-OH groups that converge in a cleft lined with basic residues, some of which are in ball-and-stick representation and labeled. Dashed lines indicate the disordered loop between residues 464 and 493. (B) Summary of protein-DNA interactions. Letter color corresponds to the domain color in Figure 1A. Boxed residues are highly conserved across the hAT superfamily. (C) Close-up of active site. (D) Effect of mutating W182 and W319 on in vitro cleavage and hairpin formation. sub: substrate; HP: hairpin; BSB: bottom strand break. BSB results from TS cleavage upon hairpin formation. (E) Active site without (left) and with (right) bound TIR. See also Figure S4.

Hermes LE and RE TIRs differ by only two bp (Figure 1A), and in the structure these bp are not contacted by protein. Furthermore, there are no protein-DNA interactions involving bp 12-16 of the TIR. We do observe a bound Na+, counterion to a phosphate group of the DNA backbone, coordinated by the main chain carbonyls of E138, E139, and L141.

Several residues that are very highly conserved across the hAT superfamily (Arenburger et al., 2011) play important structural roles at the active site where the catalytic residues D180, D248, and E572 converge. For example, W319 stacks against base G1 of the transferred strand (TS) and caps the transposon 3’ end (Figure 3C). W319 is important for one or more steps before strand transfer as the W319A mutant protein is severely impaired for in vitro hairpin formation (Figure 3D), but readily forms single-end joined (SEJ) and double-end joined (DEJ) products when provided with pre-cleaved transposon ends (Hickman et al., 2005). Mutating W319 to either F or Y results in close to wild-type hairpin formation activities with pre-cleaved ends, although W319F appears to be less accurate as it generates more than one hairpin species (Figure 3D, compare lanes 2 and 7). Collectively, these results indicate that the role of W319 is to correctly guide hairpin formation, and that other aromatic residues can accomplish the same task. Among hAT transposons, the TS terminal base is almost invariably G or A (Rubin et al., 2001; Kunze and Weil, 2002), suggesting that only purine bases can properly stack with tryptophan during hairpin formation.

Another conserved W residue close to the active site is W182 which occupies a pocket between the highly conserved F575 and the peptide plane at T183/D184. W182A is deficient in hairpin formation activity (Figure 3D), yet W182F and W182Y are partially active when the NTS is pre-nicked, although with a similar inaccuracy as for W319F. From its position in the structure, it appears likely that W182 is important for the correct positioning of the catalytic residue D180.

Two other conserved residues within the active site are H268 and R318. In the apoprotein structure (Figure 3E, left), the R318 side chain was observed close to those of D180 and E572, and was part of a hydrophobic sandwich in which the side chains of R318, W319, and H268 stack against each other. In the presence of TIRs (Figure 3E, right), R318 swings ~12Å out of the active site and forms an ion pair with a DNA backbone phosphate on the TS, 3 bp away from the transposon tip, and now H268 is located within charge-neutralization distance of D180 and E572. H268 is part of a C/DxxH motif that is found in other eukaryotic superfamilies such as the MULE (Mutator and Rehavkus), P element, and Kolobok transposons; a CxxC motif is similarly located in CMC (CACTA/Mirage/Chapaev) and Transib transposases (Yuan and Wessler, 2011).

Relative to the active site into which a transposon end leads, the intertwined dimerization domain interacts with DNA both in cis and in trans and hence brings together, or synapses, a pair of TIRs. As has been noted, the intertwined domain is topologically similar to the nonamer binding domain (NBD) of RAG1 of the V(D)J recombination system (Yin et al., 2009). The intertwined domains of Hermes and RAG1 appear to be obligate dimers, ensuring the multimerization of the full-length proteins. In both proteins, helices of one monomer wind around each other to form a U-shape cavity in which a helix of the second monomer is buried (Figure S4). Both intertwined domains recognize DNA interior to the sites of cleavage yet, despite this functional parallel, the structures of the two intertwined domain-DNA complexes are only superficially similar. Whereas the two DNA molecules synapsed by the NBD are essentially anti-parallel, Hermes TIRs are almost perpendicular to each other.

A Hermes dimer is the fundamental catalytic unit

The small interface that links dimers into a ring consists of reciprocal interactions in which a short helix (residues 499-505) of one monomer packs into a pocket on the surface of the insertion domain of another (Figure 4A,B). Introducing three point mutations into the interface disrupts the octamer, and the resulting dimers (“HermesTM” for Triple Mutant) are catalytically active in vitro (Hickman et al., 2005). We have also generated dimers by deleting the helix and surrounding residues (“HermesΔ497-516”).

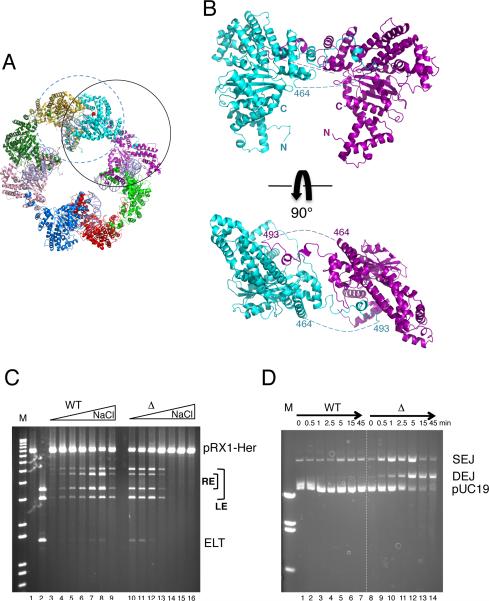

FIGURE 4. A dimer is the catalytic unit.

(A) In the octamer, the dimer where two monomers contribute to the small interface is circled in solid black, and the catalytically active dimer formed by the intertwined domain is circled in dashed blue. (B) Views of the small interface. Dashed lines indicate the disordered loops. (C) Plasmid cleavage activity of WT Hermes and HermesΔ497-516 as a function of [NaCl] (0-0.3M). Reactions were at 30°C for 60 min with 8.6 nM protein and 1 nM pRX1-Her (Figure S5). After restriction digest, bands indicate LE and RE cleavage as marked. Cleavage at both ends results in an Excised Linear Transposon (ELT). Lanes 3,10: 0.1 mM NaCl. Lanes 4,11: 50 mM. Lanes 5,12: 100 mM. Lanes 6,13: 150 mM. Lanes 7,14: 200 mM. Lanes 8,15: 250 mM. Lanes 9,16: 300 mM. (D) LE30 strand transfer activity of WT Hermes and HermesΔ497-516 as a function of time at 23°C in buffer containing 10 nM protein, 22.9 nM LE30, and 50 mM NaCl. See also Figures S5 and S6.

HermesΔ497-516 dimers can catalyze all of the catalytic steps we measure in vitro for the wild-type (WT) protein. In a plasmid cleavage assay at low ionic strength, dimers are hyperactive relative to WT Hermes when the terminal 30 bp of each transposon end are present (Figure 4C, compare lanes 3-5 and 10-12); they are also hyperactive when full transposon ends are used (data not shown). Thus, NTS nicking and hairpin formation are not impaired. Furthermore, HermesΔ497-516 dimers insert pre-cleaved 30mer LE oligonucleotides into a plasmid target with substantially higher activity than WT Hermes at low ionic strength (Figure 4D). We sequenced the DEJ products of in vitro plasmid insertion, and determined that HermesΔ497-516 dimers coordinate the insertion of two pre-cleaved ends with the correct 8 bp target joining spacing (data not shown).

Although Hermes dimers are hyperactive in vitro at low ionic strength, their activities are severely reduced under more physiologically relevant conditions. As shown in Figure 4C, WT Hermes is active for plasmid cleavage over a broad range of salt concentration (0.05-0.3 M NaCl) whereas HermesΔ497-516 is barely active once the ionic strength is raised above 150 mM (compare lanes 7-9 with 14-16).

Hermes dimers are inactive in vivo

Consistent with the lack of in vitro activity at physiological ionic strength, Hermes dimers are inactive in vivo in all of the cell types we have tested. In an interplasmid transposition assay in fly embryos (Sarkar et al., 1997), WT Hermes had a transposition frequency of 5 × 10−5 (piggyBac control was 2.4 × 10−5) whereas there were no transposition events for HermesTM. In an excision assay in Drosophila S2R+ cells, activity was undetectable for both HermesTM and HermesΔ497-516 (Figure S6A); the result was the same in HEK293 cells (data not shown). Excision activity was similarly undetectable in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Figure S6B). We have verified that HermesTM and HermesΔ497-516 are as stable as WT Hermes in vivo (Figure S6C) and are transported into the nucleus of HEK293 cells (Figure S6D).

The target binding cleft

In the structure, two TIRs are synapsed by each dimer and appear correctly oriented for strand transfer into target DNA. The obvious cleft on the rim of the ring where pairs of transposon TIRs converge is lined with positively charged residues contributed by the insertion and RNaseH-like domains (Figure 5A,B), many of which are well-conserved in the Ac family of hAT transposases (Arensburger et al., 2011). Single point mutation data indicate that residues in this region are important for in vivo transposition (Figure 5C,D; Tables S2,S3). For example, the transposase mutant K299A is severely impaired for germ-line transposition in D. melanogaster and has >100X lower frequency of transposition in the somatic nuclei of developing D. melanogaster embryos. R306A has ~8X lower frequency of somatic transposition yet is able to generate transgenic offspring at a frequency comparable to WT Hermes. K292A and K300A also show reduced transposition frequency in somatic transposition assays and are impaired at generating transgenic offspring.

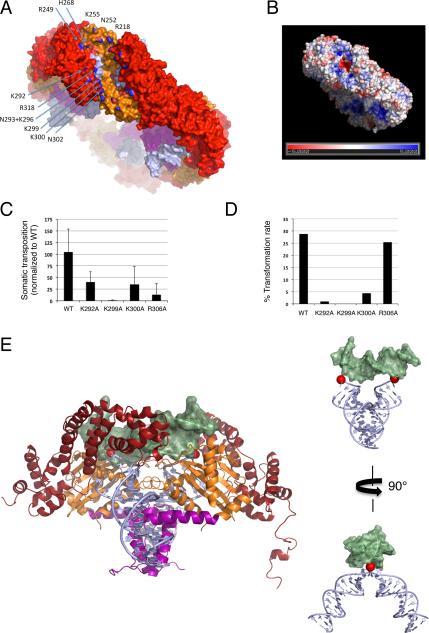

FIGURE 5. Target binding.

(A) Surface representation of the octamer rim and selected residues lining the cleft; only those of one monomer are labelled (N atoms are colored blue). (B) Electrostatic potential calculated using APBS (Baker et al., 2001) with only one dimer complexed with DNA and two active site Mn2+ at 150 mM salt. (C) Effect of single point mutations on somatic transposition frequency in D. melanogaster embryos (Table S2). Error bars represent standard deviation in Hermes transposition frequency (corrected for a piggyBac internal control) for three replicate injections. (D) Effect of single point mutations on germline transformation rate in D. melanogaster calculated by dividing the number of transgenics by the number of fertile crosses (Table S3). (E) Left: Hermes dimer docked to target DNA (light green) of the PFV intasome, PDB ID 3SO1. Right: Model of the DNAs alone with Hermes TIRs in light blue and PFV target DNA in green. Red spheres are the TS 3’-OH groups. See also Tables S2 and S3.

The cleft is ~80Å from end to end, a consequence of the angle at which it traverses the ~50Å wide octameric ring (Figure 5A), and has a distinct inward arc suggesting that target DNA is bent when bound. Within each dimer, the two terminal 3’-OH groups of the TS are located 35Å apart, too far for coordinated insertion into opposite target strands 8 bp apart if target DNA is straight B-form DNA (in which case nucleophilic attack would occur on phosphate atoms ~29.5Å apart, and the attacking -OH groups should only be ~26Å apart), but appropriately spaced if target DNA is bent. Kinked target DNA from the PFV intasome (Maertens et al., 2010) can be docked into the cleft and in the resulting model, the two 3’-OH groups approach opposite strands ~8 bp apart (Figure 5E). Although this model approximates how target DNA might be bound, we suspect that kinks will occur at the two bp represented by the T/A bp of the nTnnnnAn sequence that is the target site preference of Hermes (Gangadharan et al., 2010). Bent target DNA, observed in the MuA transpososome (Montaño et al., 2012) and shown to be important for IS231A and Tn10 transposition (Hallet et al., 1994; Pribil and Haniford, 2003), has been proposed to be a conserved feature of DNA transposition that serves to drive the reaction forward by preventing reversal of strand transfer (Montaño et al., 2012).

The Importance of the Subterminal Repeats

One notable feature of hAT transposon ends are multiple copies of short 5-6 bp subterminal sequences, apparently haphazardly arrayed in both orientations without evident periodicity (Kunze and Starlinger, 1989; Kim et al., 2011; Liu and Crawford, 1998; Liu et al., 2001; Urasaki et al., 2006). Accumulating data indicates that hAT transposases recognize their transposon tips in a bipartite manner, with weaker transposase binding to the TIRs and stronger binding by an N-terminal domain to these subterminal repeat sequences (Kunze and Starlinger, 1989; Becker and Kunze, 1997; Mack and Crawford, 2001; Urasaki et al., 2006; Kahlon et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011).

A 5’-GTGGC repeat has been previously identified within Hermes ends where one repeat on each end overlaps with the TIR, and it has been proposed that some of these repeats are likely important for DNA binding (Kim et al., 2011). There are seven repeats within Hermes (Figure 6A), and the location of the outermost repeat on each end, defined here as 13 bp encompassing the GTGGC repeat and designated “LE_1” (bp 13-25 from the tip of LE) and “RE_1” (bp 13-25 from the RE tip), taken in light of the structure, suggests that these are bound by the BED-finger domain: Hermes79-612 does not interact with the TIR after bp 11, and if TIR DNA were extended towards the center of the octamer, the BED domains would likely encounter DNA subterminal to the TIRs.

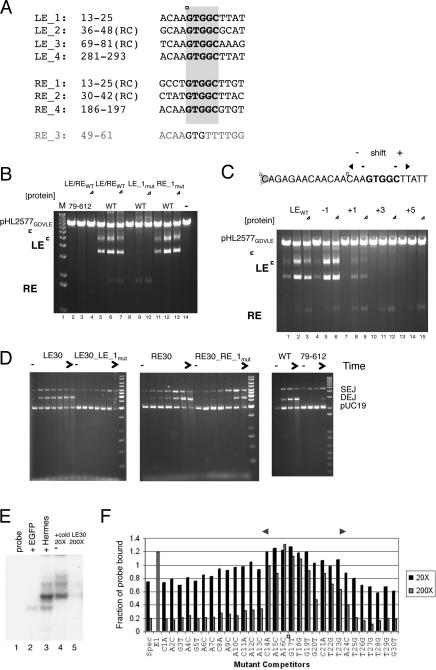

FIGURE 6. Subterminal repeats within Hermes ends are recognized by the BED domain.

(A) Alignment of subterminal repeats containing 5’-GTGGC (black) where numbering is the distance in bp from the tip of either LE or RE. “RC” indicates that the repeat is in the opposite orientation relative to LE_1. Hermes contains no other 5’-GTGGC repeats. An eighth repeat “RE_3” (grey) was inferred from in vitro transposition reactions. (B) Effect of mutating LE_1 or RE_1 on plasmid cleavage as a function of protein concentration. For each set, [protein] are 9.5 nM, 47 nM, and 95 nM. (C) Effect on plasmid cleavage of shifting LE_1 sequence (boxed) relative to the transposon tip. (D) Time course of strand transfer upon mutating LE_1 or RE_1, and as a function of deleting the BED domain. For the first four sets, time points are 0, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 15, and 45 min at 25°C in buffer containing 15 nM protein, 28.6 nM ends, and 200 mM NaCl; for the fifth set, comparison of LE30 strand transfer activity by WT Hermes to that of Hermes79-612, time points are 0, 1, 7, and 45 min. (E) Electromobility shift assay with Drosophila-expressed Hermes and a LE30 probe. Lane 1: probe alone. Lane 2: EGFP control nuclear extract. Lane 3: Hermes nuclear extract. Lanes 4, 5: Hermes nuclear extract with the indicated excess of LE30 specific competitor. (F) Results of EMSA competition assay with single base mutant probes. Dark bars indicate 20X competitor levels and lighter bars indicate 200X levels. E1 is the nonspecific competitor at 200X. If the mutation had no effect, values similar to that for the specific competitor (Spec) are expected. The double-headed arrow indicates the region of strongest interaction, which includes the 5’-GTGGC repeat (boxed). See also Figure S7 and Table S4.

To determine if the repeats within Hermes ends are important for in vitro activity, we mutated the ends in several ways. As shown in Figure 6B, mutation of either LE_1 or RE_1 to random sequence leads to loss of plasmid cleavage activity on that end. When the position of LE_1 is shifted relative to the transposon tip, a shift of one bp towards the tip is tolerated (Figure 6C; lanes 4-6) whereas a one bp shift in the other direction is less so (lanes 7-9). Inserting 3 or 5 bp between the TIR and LE_1 leads to a complete loss of plasmid cleavage activity on LE (lanes 10-15), indicating that the phasing of these two regions is crucial. In this plasmid cleavage assay, LE cleavage can occur without RE cleavage and vice versa, and BED-deleted Hermes79-612 is barely active under these experimental conditions (Figure 6B, lanes 2-4). In a strand transfer assay, mutation of LE_1 and RE_1 also leads to a loss of activity (Figure 6D), and a similar loss of activity was observed for Hermes79-612 with an unmutated LE30 end. Thus, it appears that the BED domain interacts with the outermost subterminal repeat on each end, and this is important for both cleavage and strand transfer.

To more finely map the role of the DNA sequence just subterminal of the TIR, we measured strand transfer activity as a function of LE length. As the length was increased from 17 bp to include more of LE_1, we observed a dramatic increase in activity once the DNA length exceeded 21-22 bp (Figure S7B,C). This strongly suggests that the first 9 bp of the LE_1 subterminal repeat are sufficient to engage the BED domain.

Finally, we mapped the interaction of Hermes with LE_1 using a competition binding assay based on the gel shift of a LE30 probe. When the nuclear extract from Drosophila S2 cells expressing Hermes (Figure S7D) was incubated with LE30, one major band was observed with several faint bands above and below (Figure 6E). This binding could be competed off with specific LE30 competitor, and we tested the ability of mutated probes, each with a single transversion mutation at each position, to perturb LE30 binding. The results map the region of strongest interaction to bp 14-24 (Figure 6F), essentially spanning the LE_1 subterminal repeat.

The importance of long ends

In Hermes, the transposase gene is flanked by 449 bp of LE and 464 bp of RE DNA (Warren et al., 1994). For hobo, whose transposase is 55% identical in sequence to Hermes, in vivo transposition requires at least 140 bp of its LE and 65 bp of RE (Kim et al., 2011). To establish if Hermes also has an end length requirement, we tested transposition in vivo as a function of transposon length (Table S4). In a Drosophila cell line stably expressing Hermes, there was a ~2.4-fold decrease in transposition when the LE was reduced from 444 to 305 bp and the RE simultaneously reduced from 384 to 307 bp. Notably, no transposition was seen if only 30 bp of Hermes LE and RE were present, indicating that sequences beyond the TIRs and the first subterminal repeat are needed. End asymmetry was also important as no transposition was observed when the ends were symmetrized by replacing RE with 305 bp of LE, suggesting that both the LE and RE are required for transposition.

Why are there two binding sites at the Hermes transposon tips?

To understand why Hermes recognizes both its TIR and a subterminal repeat, we used fuzznuc from the EMBOSS suite (Rice et al., 2000) which searches for short nucleotide sequences in genomes. As there is no full genome assembly for M. domestica, a natural host of Hermes, we searched the D. melanogaster genome (120 Mb; release 5) for the sequence 5’-CAGAGnnnnnC, the TIR bases that are specifically contacted by Hermes where “n” is any base. This sequence occurs 20421 times, indicating that the TIRs are not sufficient to uniquely direct Hermes to its transposon ends. The 8 bp sequence present in all four of the LE Hermes subterminal repeats, 5’-CAAGTGGC (Figure 6A), occurs 3828 times. However, when the two sequences were combined with the correct TIR/LE_1 spacing, this longer sequence is present only once. As the M. domestica genome is ~1.6-fold larger than that of D. melanogaster (Gao and Scott, 2006), this suggests that the TIR and a subterminal repeat together are enough to allow Hermes to find its transposon ends within the genomic background of its host.

Identification of alternate cleavage sites at RE

When we sequenced and characterized 63 Hermes-catalyzed in vitro transpositions events into a target plasmid, most were perfect, i.e., only Hermes DNA had inserted into the target, all Hermes DNA was intact, and there were 8 bp TSDs (Table S5). Curiously, among the imperfect transposition events, TIR deletions occurred only at the RE and usually involved 18 bp or 37 bp deletions. This discrete deletion size could arise from alternate binding of Hermes to its RE coinciding with cryptic TIR sequences, in which Hermes mistakes RE_2 or another region (designated RE_3) for RE_1 (Figure 7A). This seems possible as the bases conserved in the cryptic TIRs correspond to those which formed specific contacts in the Hermes structure: four of the five terminal bp and C11 on the NTS. This suggests that there may be one more RE subterminal repeat that was not initially identified as it does not have a GTGGC repeat yet is clearly related to the sequences of LE_1 and LE_4. Thus, we can identify four subterminal repeats on Hermes LE and four on RE, asymmetrically arrayed.

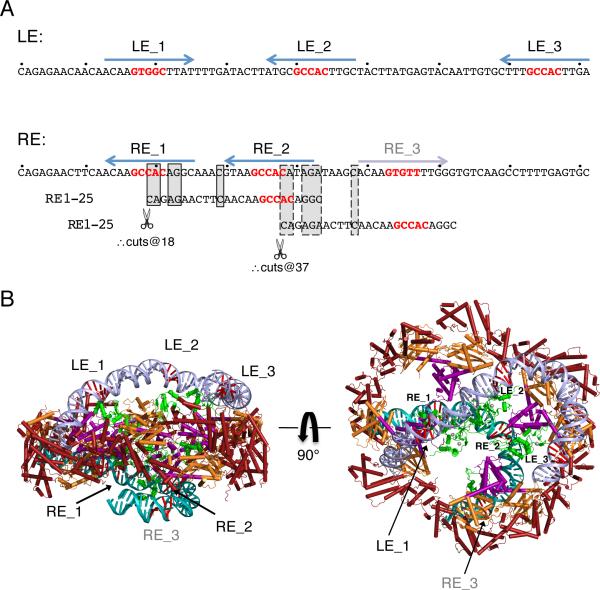

FIGURE 7. Hermes/DNA recognition beyond the TIRs.

(A) Arrangment of subterminal repeats within NTS of LE 1-81 and RE 1-81, where 5’-GTGGC of each repeat is in red. Below the RE sequence are two alignments with RE bp 1-25 (common bases are boxed with solid lines for the alignment of RE_2 with RE_1 and dashed lines for the alignment of RE_3 with RE_1). Transposition assay results suggest that Hermes can mistake RE_2 and RE_3 for RE_1, resulting in aberrant cleavage. (B) Modeled Hermes binding to its transposon ends. The structure of the first 16 bp of each end are those in the observed crystal structure. On LE (light blue), modeled DNA from bp 17-81 is bent to bring LE_2 and LE_3 close to the presumed locations of the BED domains (green; PDB ID 2CT5). RE (turquoise) bp 17-66 are modeled using 50 bp of nucleosomal DNA (PDB ID 1AOI). 5’-GTGGC of each subterminal repeat is in red. The modeled BED domains have been allowed to move within the ring relative to the model in Figure 2C. It is not clear how LE_4 and RE_4 might be bound. See also Table S5.

DISCUSSION

The most surprising aspect of the Hermes hAT transposase structure is that it is an octamer. Other transpososomes exhibit an overabundance of monomers yet the octameric ring of Hermes seems excessive. The MuA transposase is a tetramer in its active form (Lavoie et al., 1991), and the “extra” monomers provide additional DNA binding domains for multiple MuA binding sites located on phage genome ends; the related retroviral intasomes are also obligate tetramers for reasons not yet clear (Li et al., 2006; Cherepanov et al., 2011). Since Hermes dimers generated by mutagenesis are not functional in vivo but appear capable of all of the in vitro activities of a transposase, the octamer must confer a crucial property beyond catalysis. We have ruled out that the octamer simply provides intracellular stability to an otherwise unstable dimer or that nuclear localization is compromised.

The structure and biochemical analyses presented here suggest that one important aspects of the octamer is that it provides multiple BED domains for transposon end binding. Although we observed eight transposon TIRs bound in our crystallized complex, this is most likely an artifact of using short oligonucleotides to facilitate crystallization as the Hermes octamer is unable to bind more than two transposon ends in vitro once the oligonucleotide length is increased. Instead, we favor a model in which one catalytic dimer within the octamer binds two ends, and the remaining monomers contribute important interactions to the same ends.

The location of BED domains inferred by the EM data (missing in the crystal structure due to the obstinate behavior of the full-length protein) clearly places them so that two could interact with the outermost subterminal repeat on each end. Our observations that mutation of LE_1 or RE_1 abolishes both DNA cleavage and strand transfer and that the spacing of LE_1 relative to the tip of the transposon is critical, implicate these sequences as specific transposase binding sites.

One obvious attribute of an octamer is that, in addition to two BED domains for binding the outermost repeat at each transposon end, it possesses six more that can be used to bind additional subterminal repeats. This would explain a conserved feature of hAT transposons which is an abundance of short DNA repeats scattered throughout transposon ends. The structure therefore suggests a model for end binding in which the transposon ends provide multiple internal binding sites to tether the transposase, and this directs weakly bound TIRs into two active sites within the same dimer (Figure 7B). As we only observe TSDs of 8 bp (Table S5), productive transposition must only occur when the two ends are bound by the same dimer.

Multiple site-specific DNA binding domains could also provide increased avidity to regions of DNA containing many BED domain binding sites, enhancing binding specificity to the transposon against a background of non-specific DNA binding. The lack of in vivo activity by Hermes dimers, although an effect of physiological ionic strength, might also be a manifestation of not having enough BED domains to stably bind transposon ends. Another consequence of octamerization are four non-specific DNA binding sites around the rim of the ring which could also have an important avidity effect in capturing target DNA.

The proposal that an octamer provides multiple BED domains to recognize multiple subterminal repeats also explains the observation that for all hAT transposons studied to date, activity in vivo depends on long transposon ends and the bipartite transposon tips are not sufficient. For example, Tol2 requires the terminal 200 bp of its LE and 150 bp of its RE for excision and transposition (Urasaki et al., 2006). For Ac, 200 bp at both ends are needed for wild-type levels of transposition (Coupland et al., 1989), and for Tag1, ~100 bp are required at each end (Liu et al., 2001). Although short transposon ends can be used for in vitro assays with Hermes, perhaps because of the high concentration of specific DNA involved, 30 bp of each end are not sufficient for in vivo transposition in Drosophila.

The structure provides insight into another aspect of hAT transposition: where it has been examined, in vivo transposition does not occur with artificial transposons consisting of either two LEs or two REs (Coupland et al., 1989; Urasaki et al., 2006). The DNA binding asymmetry we observe within each dimer - one TIR juts out from the plane of the ring whereas the second is essentially in plane - suggests that if multiple interactions between BED domains and repeat sequences are needed, these will be structurally asymmetric as well. Consistent with this possibility, the subterminal repeats we identified here are arranged differently on the two ends. This in turn dictates that, to model LE and RE binding to the Hermes octamer, the two ends must adopt different conformations. Thus, if asymmetry is an inherent feature of the transpososome, it seems unlikely that symmetric ends could be structurally accommodated. Interestingly, asymmetric recognition sites are also a property of RAG1/2-mediated recombination which only rearranges gene segments with two different spacer lengths in their Recombination Signal Sequences (RSSs), the so-called 12/23 rule (reviewed in Schatz and Swanson, 2011).

It is not yet known if all hAT transposases are active as octamers. It is possible that the basic building block of hAT transposases is a dimer and that some have evolved different assembly properties to exploit DNA binding to subterminal repeats. Among hAT transposases, only hobo and Homer have three phenylalanine residues that align with Hermes F502/F503/F504 of the small interface helix (Arensburger et al., 2011), and would be predicted to exhibit the same potential for multimerization through a hydrophobic helix motif. Hermes, hobo, and Homer are phylogenetically each others' closest relatives, and are further distinguished from other hAT transposases by a CCHC-type BED motif. Perhaps these three transposases have a particular transpososome architecture that takes advantage of a large preassembled multimer to bind DNA. Ac and certain other characterized transposons have many more repeats within their transposon ends than the eight we have been able to identify for Hermes. For example, the minimal Ac transposase binding site is repeated 25 times at its 5’ end and 20 times at its 3’ end (Becker and Kunze, 1997). In Tol2, the 5-bp sequences 5’-AAGTA and 5’-GAGTA occur 33 times in the transposon ends (Urasaki et al., 2006), and Tam3 possesses 40 copies of a 5-bp motif transposase binding site (Hashida et al., 2006). This difference might reflect an architecturally distinct solution for binding subterminal repeats during transposition.

Although the catalytic unit of Hermes appears to be a dimer, the monomer arrangement and trajectories of TIR ends within the synaptic complex differ from those of other structurally characterized dimeric transpososomes, Tn5 and Mos1 (Davies et al., 2000; Richardson et al., 2009). On the other hand, there is an uncanny resemblance between the Hermes dimer and the “anchor-shaped” organization of RAG1/2 bound to RSS DNA deduced by EM (Grundy et al., 2009). The contours of the assemblies are similar, and the proposed paths of DNA through RAG1/2 echo those of the TIRs within a Hermes dimer. In addition to their shared mechanism of generating double-strand breaks via a flanking DNA hairpin, other parallels between hAT transposases and RAG1 have been noted including a predicted α-helical insertion domain into the RNaseH-like fold of RAG1 (Lu et al., 2006), and the bipartite organization of their DNA binding partners (Kunze and Weil, 2002).

Transposons are versatile genetic tools, and several such as Tn5, Tol2, piggyBac, and Sleeping Beauty are widely used for genomic manipulation experiments (VandenDriessche et al., 2009). The structure of Hermes determined here opens up avenues for developing improved versions of hAT transposons for non-viral gene delivery or other genome applications. For example, it might be possible to insert a specific DNA binding domain close to the clefts at the periphery of the ring where it would contact target DNA leading in or out of the active sites; this might direct insertion to a specific chromosomal location. Alternatively, our experiments implicate sloppy RE processing in the generation of aberrant transposition events, a result that evokes the effect of mutating one end of retroviral DNA so that it is a poor substrate for integrase, which in turn leads to abnormal proviruses and genomic rearrangements (Oh et al., 2006). It will be interesting to see if changing the RE subterminal repeat sequences might improve insertion fidelity, and the larger question of how BED domains interact with subterminal repeats to coordinate transpososome function is an area of active investigation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

For E. coli expression, the coding regions for full-length Hermes and Hermes79-612 were cloned into pBAD/Myc-His (Invitrogen) such that the resulting proteins were untagged at either terminus. After screening Cys mutations for improved solubility properties, all structural work was performed using Hermes79-612 C519S. Proteins were expressed at 19°C in Top10 cells, and soluble protein purified using Heparin Sepharose and size exclusion. Purified untagged full-length Hermes was used for SEC-MALS, SAXS and negative stain EM analysis. The deletion dimer was similarly purified. Hermes W319 and W182 point mutants were purified as described in Zhou et al. (2004).

Crystallization and Structure Determination

After size exclusion, Hermes79-612 was concentrated and LE16-1T DNA (IDT) added to a final molar ratio of 1:1.2 protein:DNA. The complex was formed by dialysis against 0.18 M KCl, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, and 5 mM DTT, and crystals were grown at 19°C by the hanging drop method. To screen for derivatives, crystals in stabilizing buffer were soaked in 0.2 - 5 mM Ta6Br 2+ 12 (Jena Bioscience) for 3-24 hr prior to cryoprotection. Crystallographic details can be found in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

In Vitro Assays

To assess the ability of Hermes to carry out discrete steps of the transposition reaction, several assays were used. To assess cleavage, purified Hermes was incubated with plasmids containing either the full Hermes LE and RE (pHL2577 and variants) or the final 30 bp of each end (pRX1-Her). When mutated ends were used, changes were introduced using the QuikChange method (Agilent). After incubation, DNA was isolated and subjected to restriction digest to generate DNA fragments that could be identified after separation on an agarose gel. Cleavage assays were also carried out using oligonucleotides containing 60 bp of Hermes LE and 11 bp of flanking DNA.

To assess the ability of Hermes to generate hairpins when supplied with a pre- nicked LE, protein was incubated with a 71 bp oligonucleotide containing an intact bottom strand with a nicked top strand. For strand transfer, Hermes was incubated with oligonucleotides representing various lengths of pre-cleaved LE sequence and a pUC19 target plasmid.

For in vitro transposition into pGDV1, nuclear extracts of a Drosophila S2 cell line stably expressing Hermes were incubated with a Hermes donor plasmid and pGDV1. Recovered plasmid DNA was transformed into E. coli and the transposition events characterized.

EMSA and Competition Assay

Nuclear extracts of S2 cell lines stably expressing either Hermes or EGFP as a negative control were prepared, and extracts and probes were incubated for 20 min at room temperature prior to being run on a 5% TBE polyacrylamide gel. When competitors were used, nuclear extracts and competitors were incubated for 15 min at room temperature, then labeled probe was added and incubated for an additional 20 min.

In vivo Transposition

To compare the activities of WT and HermesTM in Drosophila embryos, a five-plasmid assay was carried out essentially as described by Sarkar et al., 1997. The transposition frequency was calculated as the number of independent events divided by the donor titer. In Drosophila cells stably expressing Hermes, a two-plasmid assay was carried out in which one plasmid supplied Hermes transposon ends of varied length and pGDV was the target.

Model for Transposon End Binding

To model LE binding to the Hermes octamer, the “make-na” server at http://structure.usc.edu/make-na was used to generate three bent DNA models that were overlapped to produce a 81-mer.

Details of experimental procedures can be found in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Hermes transposase assembles into an octameric ring organized as a tetramer of dimers

Dimer is active in vitro, not in vivo, suggesting an important role for the octamer

Subterminal repeats within transposon ends are likely bound by multiple BED domains

Asymmetry in subterminal repeat arrangement suggests a model for two-end binding

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially funded by the NIH Intramural Programs of NIDDK (F.D., A.B.) and NIAMS (A.S), Bethesda, MD. P.W.A. and N.L.C. were funded by PHS award A1045741. Crystallographic data were collected at the SER-CAT 22-ID beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (ANL). For the SAXS experiments, we gratefully acknowledge use of the shared scattering beamline 12-IDC resource allocated under the PUP-77 agreement between the National Cancer Institute and ANL and thank Soenke Seifert (ANL) for his support. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under contract no. W-31-109-Eng-38. We thank Sriram Subramaniam and members of his lab for their preliminary EM efforts. We also thank Nadine Samara for critical reading of the manuscript, Primrose Musingarimi for help with Sf9-expressed Hermes, Robert Hice for assistance with EMSA experiments, and Susan Chacko of the Helix systems group, CIT, NIH for advice and help with fuzznuc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: ABH, FD, NLC, PWA designed the biochemical experiments; ABH and FD performed the X-ray crystallography, determined and analyzed the structure; ABH, HEE, XL, performed in vitro biochemistry experiments; XL performed mammalian in vivo experiments; JAK, TL, AD and PWA were responsible for in vivo Drosophila experiments; the EM analysis was performed by GT and ACS; the SAXS analysis was performed by AG and AB; and ABH, PWA, NLC, and FD wrote the manuscript.

ACCESSION NUMBER

The coordinates of the Hermes-DNA structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under ID code xxxx.

REFERENCES

- Aravind L. The BED finger, a novel DNA-binding domain in chromatin-boundary-element-binding proteins and transposases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:421–423. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arensburger P, et al. Phylogenetic and functional characterization of the hAT transposon superfamily. Genet. 2011;188:45–57. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.126813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, Breitbart M, Edwards RA. Transposases are the most abundant, most ubiquitous genes in nature. Nucl. Acids Res. 2010;38:4207–4217. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker H-A, Kunze R. Maize Activator transposase has a bipartite DNA binding domain that recognizes subterminal sequences and the terminal inverted repeats. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1997;254:219–230. doi: 10.1007/s004380050410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biémont C. A brief history of the status of transposable elements: From junk DNA to major players in evolution. Genet. 2010;186:1085–1093. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.124180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi BR, Hong TJ, Findley SD, Gelbart WM. Evidence for a common evolutionary origin of inverted repeat transposons in Drosophila and plants: hobo, Activator, and Tam3. Cell. 1991;66:465–471. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov P, Maertens GN, Hare S. Structural insights into the retroviral DNA integration apparatus. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011;21:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupland G, Plum C, Chatterjee S, Post A, Starlinger P. Sequences near the termini are required for transposition of the maize transposon Ac in transgenic tobacco plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:9385–9388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DR, Goryshin IY, Reznikoff WS, Rayment I. Three-dimensional structure of the Tn5 synaptic complex transposition intermediate. Science. 2000;289:77–85. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson A, Finnegan DJ. Excision of the Drosophila mariner transposon Mos1: Comparison with bacterial transposition and V(D)J recombination. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00798-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangadharan S, Mularoni L, Fain-Thornton J, Wheelan SJ, Craig NL. DNA transposon Hermes inserts into DNA in nucleosome-free regions in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21966–21972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016382107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Scott JG. Use of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction to estimate the size of the house-fly Musca domestica genome. Insect Mol. Biol. 2006;15:835–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishaev A, Guo L, Irving T, Bax A. Improved fitting of solution X-ray scattering data to macromolecular structures and structural ensembles by explicit water modeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15484–15486. doi: 10.1021/ja106173n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy GJ, Ramón-Maiques S, Dimitriadis EK, Kotova S, Biertümpfel C, Heymann JB, Steven AC, Gellert M, Yang W. Initial stages of V(D)J recombination: The organization of RAG1/2 and RSS DNA in the postcleavage complex. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallet B, Rezsöhazy R, Mahillon J, Delcour J. IS231A insertion specificity: consensus sequence and DNA bending at the target site. Mol. Micro. 1994;14:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashida S-N, Uchiyama T, Martin C, Kishima Y, Sano Y, Mikami T. The temperature-dependent change in methylation of the Antirrhinum transposon Tam3 is controlled by the activity of its transposase. Plant Cell. 2006;18:104–118. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehl R, Nacken WKF, Krause A, Saedler H, Sommer S. Structural analysis of Tam3, a transposable element from Antirrhinum majus, reveals homologies to the Ac element from maize. Plant Mol. Biol. 1991;16:369–371. doi: 10.1007/BF00020572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman AB, Perez ZN, Zhou L, Musingarimi P, Ghirlando R, Hinshaw JE, Craig NL, Dyda F. Molecular architecture of a eukaryotic DNA transposase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:715–721. doi: 10.1038/nsmb970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman AB, Chandler M, Dyda F. Integrating prokaryotes and eukaryotes: DNA transposases in light of structure. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;45:50–69. doi: 10.3109/10409230903505596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Honeybee Genome Sequencing Consortium Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nature. 2006;443:931–949. doi: 10.1038/nature05260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CRL, Burns KH, Boeke JD. Active transposition in genomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012;46:651–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlon AS, Hice RH, O'Brochta DA, Atkinson PW. DNA binding activities of the Herves transposase from the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Mobile DNA. 2011;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1759-8753-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov SS, Jurka J. RAG1 core and V(D)J recombination signal sequences were derived from Transib transposons. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Hice RH, O'Brochta DA, Atkinson PW. DNA sequence requirements for hobo transposable element transposition in Drosophila melanogaster. Genet. 2011;139:985–997. doi: 10.1007/s10709-011-9600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg RD. Structure of chromatin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1977;46:931–954. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.004435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze R, Starlinger P. The putative transposase of transposable element Ac from Zea mays L. interacts with subterminal sequences of Ac. EMBO J. 1989;8:3177–3185. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze R, Weil CF. The hAT and CACTA Superfamilies of Plant Transposons. In: Craig NL, et al., editors. Mobile DNA II. ASM Press; Washington DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie BD, Chan BS, Allison RG, Chaconas G. Structural aspects of a higher order nucleoprotein complex: induction of an an altered DNA structure at the Mu-host junction of the Mu Type I transpososome. EMBO J. 1991;10:3051–3059. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Mizuuchi M, Burke TR, Jr., Craigie R. Retroviral DNA integration: reaction pathway and critical intermediates. EMBO J. 2006;25:1295–1304. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Crawford NM. Characterization of the putative transposase mRNA of Tag1, which is ubiquitously expressed in Arabidopsis and can be induced by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation with dTag1 DNA. Genet. 1998;149:693–701. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.2.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Mack A, Wang R, Galli M, Belk J, Ketpura NI, Crawford NM. Functional dissection of the cis-acting sequences of the Arabidopsis transposable element Tag1 reveals dissimilar subterminal sequence and minimal spacing requirements for transposition. Genet. 2001;157:817–830. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.2.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CP, Sandoval H, Brandt VL, Rice PA, Roth DB. Amino acid residues in Rag1 crucial for DNA hairpin formation. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:1010–1015. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack AM, Crawford NM. The Arabidopsis TAG1 tranposase has an N-terminal zinc finger DNA binding domain that recognizes distinct subterminal motifs. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2319–2331. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertens GN, Hare S, Cherepanov P. The mechanism of retroviral integration from X-ray structures of its key intermediates. Nature. 2010;468:326–329. doi: 10.1038/nature09517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1950;36:344–355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.36.6.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaño SP, Pigli YZ, Rice PA. The Mu transpososome structure sheds light on DDE recombinase evolution. Nature. 2012;491:413–417. doi: 10.1038/nature11602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J, Chang KW, Hughes SH. Mutations in the U5 sequences adjacent to the primer binding site do not affect tRNA cleavage by Rous Sarcoma Virus RNase H but do cause aberrant integrations in vivo. J. Virol. 2006;80:451–459. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.451-459.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribil PA, Haniford DB. Target DNA bending is an important specificity determinant in target site selection in Tn10 transposition. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;330:247–259. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00588-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambo RP, Tainer JA. Super-resolution in solution X-ray scattering and its applications to structural systems biology. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013;42:415–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JM, Colloms SD, Finnegan DJ, Walkinshaw MD. Molecular architecture of the Mos1 paired-end complex: The structural basis of DNA transposition in a eukaryote. Cell. 2009;138:1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin E, Lithwick G, Levy AA. Structure and evolution of the hAT transposon superfamily. Genet. 2001;158:949–957. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.3.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Coates CJ, Whyard S, Willhoeft U, Atkinson PW, O'Brochta DA. The Hermes element from Musca domestica can transpose in four families of cyclorrhaphan flies. Genet. 1997;99:15–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02259495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz DG, Swanson PC. V(D)J recombination: Mechanisms of initiation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable PS, et al. The B73 maize genome: Complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326:1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streck RD, MacGaffey JE, Beckendorf SK. The structure of hobo transposable elements and their insertion sites. EMBO J. 1986;5:3615–3623. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04690.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urasaki A, Morvan G, Kawakami K. Functional dissection of the Tol2 transposable element identified the minimal cis-sequence and a highly repetitive sequence in the subterminal region essential for transposition. Genet. 2006;174:639–649. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.060244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VandenDriessche T, Ivics Z, Izsvák Z, Chuah MKL. Emerging potential of transposons for gene therapy and generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2009;114:1461–1468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-210427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WD, Atkinson PW, O'Brochta DA. The Hermes transposable element from the house fly, Musca domestica, is a short inverted repeat-type element of the hobo, Ac, and Tam3 (hAT) element family. Genet. Res. 1994;64:87–97. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300032699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker T, et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nature Rev. Genet. 2007;8:973–982. doi: 10.1038/nrg2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin FF, Bailey S, Innis CA, Ciubotaru M, Kamtekar S, Steitz TA, Schatz DG. Structure of the RAG1 monomer binding domain with DNA reveals a dimer that mediates DNA synapsis. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:499–508. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y-W, Wessler SR. The catalytic domain of all eukaryotic cut-and-paste transposase superfamilies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:7884–7889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104208108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Mitra R, Atkinson PW, Hickman AB, Dyda F, Craig NL. Transposition of hAT elements links transposable elements and V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2004;432:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature03157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.