Abstract

Background and purpose

Metal artifact reduction sequence (MARS) MRI and ultrasound scanning (USS) can both be used to detect pseudotumors, abductor muscle atrophy, and tendinous pathology in patients with painful metal-on-metal (MOM) hip arthroplasty. We wanted to determine the diagnostic test characteristics of USS using MARS MRI as a reference for detection of pseudotumors and muscle atrophy.

Patients and methods

We performed a prospective cohort study to compare MARS MRI and USS findings in 19 consecutive patients with unilateral MOM hips. Protocolized USS was performed by consultant musculoskeletal radiologists who were blinded regarding clinical details. Reports were independently compared with MARS MRI, the imaging gold standard, to calculate predictive values.

Results

The prevalence of pseudotumors on MARS MRI was 68% (95% CI: 43–87) and on USS it was 53% (CI: 29–76). The sensitivity of USS in detecting pseudotumors was 69% (CI 39–91) and the specificity was 83% (CI: 36–97). The sensitivity of detection of abductor muscle atrophy was 47% (CI: 24–71). In addition, joint effusion was detected in 10 cases by USS and none were seen by MARS MRI.

Interpretation

We found a poor agreement between USS and MARS MRI. USS was inferior to MARS MRI for detection of pseudotumors and muscle atrophy, but it was superior for detection of joint effusion and tendinous pathologies. MARS MRI is more advantageous than USS for practical reasons, including preoperative planning and longitudinal comparison.

Approximately 1.5 million metal-on-metal (MOM) hip arthroplasties have been implanted worldwide since 1996 (FDA 2012). A high early failure rate for these prostheses has recently been demonstrated (Smith et al. 2012). The pattern of failure appears to differ from other hip arthroplasty types, with adverse reactions to wear-related metal debris being a prominent feature (Pandit et al. 2008, Kwon et al. 2011). These solid or cystic lesions have been termed pseudotumors (Pandit et al. 2008). A wide spectrum of adverse tissue reactions have been described. Histologically, using their pseudocapsules, these have been termed aseptic lymphocytic vasculitis-associated lesions (ALVALs) (Willert et al. 2005).

Health regulatory guidelines recommend investigation with cross-sectional imaging, using either metal artifact reduction sequence (MARS) MRI or ultrasound scanning (USS), to evaluate the periprosthetic soft tissues. A number of advantages and disadvantages have been reported (Table 1). MARS MRI overcomes the obscurement of periprosthetic tissues that occurs with conventional MRI protocols. However, structures directly adjacent to the metal implant—including tendinous insertions and effusions—are still often obscured. MARS MRI remains a highly sensitive modality for the detection of small pseudotumors and assessment of hip muscle atrophy (Sabah et al. 2011, Liddle et al. 2013). The high-resolution capability of USS allows detailed imaging of solid or cystic extra-articular lesions and also detection of muscle atrophy (Sofka et al. 2004), joint effusions, gluteal tendon avulsion, and iliopsoas or trochanteric bursitis (Long et al. 2012). USS is also commonly used during guided anesthetic injection or fluid aspiration.

Table 1.

A comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of MARS MRI and ultrasound imaging of metal-on-metal hips

| Ultrasound | MARS MRI | |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Clinical evaluation | No metal artifact produced. Operator-dependent; requires an experienced musculoskeletal sonographer. Must be reported at the time of scanning. |

Not operator dependant. Can be reported later. Images can be sent off-site for specialist opinion. Useful during preoperative planning for revision arthroplasty (Hart et al. 2012). |

| a) Pseudotumors | Excellent at visualizing extra-articular fluid collections (including within the iliopsoas and trochanteric bursa). Can differentiate easily between solid and fluid composition. Deep posterior lesions and small lesions can often be missed (Nishii et al. 2012). |

High sensitivity for the detection of solid and cystic soft tissue lesions including both small lesions and posterior lesions (Hart et al. 2012, Liddle et al. 2013). |

| b) Muscles | Dual-view function can be used to simultaneously compare muscles on contralateral sides. Currently not validated to assess muscle atrophy of the hip rotator cuff. |

T1-weighted images excellent for assessment of the degree of muscle atrophy (Bal and Lowe 2008, Sabah et al. 2011). Complete cross-sectional imaging allows easy comparison with the contralateral side. Images can be accurately compared over time. |

| c) Other pathology | Sensitive for joint effusion diagnosis (Foldes et al. 1992). Can visualize the iliopsoas and gluteal tendons in detail. Can be used to detect tendon avulsion of hip abductor muscles (Garcia et al. 2010). Dynamic imaging is possible. Hands-on examination can help localize pathology. |

Sensitive modality for the assessment of gluteal tendon avulsion. Other pathology can be identified, including metastatic disease, fractures, and muscle and bone marrow edema. Metal artifact may obscure effusions and tendons directly adjacent to the implant. |

| 2) Patient acceptability | Safe, with no major contraindications (can be used on patients with cardiac pacemaker implants). No problems with claustrophobia. Non-invasive. Invasive when used for guided fluid aspiration or injection. |

Enclosed space often unacceptable to patients with claustrophobia.

Contraindicated in patients with incompatible metallic implants (e.g. a cardiac pacemaker). |

| 3) General | Relatively low costs. Compact equipment requires minimal space. Often readily accessible in smaller healthcare trusts. |

Relatively expensive.

The bulky equipment requires a relatively large space. May not be accessible in smaller healthcare trusts. |

There is debate as to whether USS or MARS MRI should be used as the initial imaging modality for detection of pseudotumors around MOM hips. There have not been any published studies directly comparing the diagnostic performance of the 2 modalities, and guidelines leave the use of either investigation at the discretion of the surgeon.

We determined the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of USS using MARS MRI as a reference for the detection of pseudotumors and muscle atrophy.

Patients and methods

We designed a blind prospective cohort study to determine the diagnostic performance of USS for the detection of soft tissue lesions (pseudotumors), muscle atrophy, tendon abnormalities, and joint effusions in patients with MOM hip arthroplasties using MARS MRI as a reference—our current gold-standard imaging modality for assessment of pseudotumor and muscle atrophy (Hart et al. 2012). Validation of imaging findings was performed at revision surgery, when this was performed during the scope of this study. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Riverside Ethics Committee, COREC 09/H0711/3; Jan 2009) and informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients recruited for imaging were those identified by current regulatory guidance (MHRA), including patients with a symptomatic MOM hip (Oxford hip score ≤ 41/48) and those with a large-diameter bearing (≥ 36 mm) as either a resurfacing or stemmed arthroplasty.

We excluded bilateral hip replacements because this prevented use of the contralateral side as a reference for muscle atrophy assessment. We also excluded patients who were followed up with imaging at less than 1 year postoperatively because imaging cannot reliably distinguish between postoperative inflammatory changes and abnormal soft tissue reactions during this period (Nishii et al. 2012).

Patient recruitment

Patients who met the inclusion criteria in our local outpatient clinic were identified and those who had undergone a retrospective MARS MRI scan within the previous year were recruited to have protocolized USS. New patients attending the outpatient clinic with unexplained pain who met the inclusion criteria were also recruited for both prospective MARS MRI and USS.

Unexplained pain was defined as an Oxford hip score of less than excellent (≤ 41/48) and no diagnosis after a traditional hip assessment that included clinical history, examination, plain radiographs, blood tests for inflammatory markers, and hip aspirate.

Patients

19 consecutive patients were recruited over a period of 6 months for prospective USS. This included 15 females and 4 males with a median age of 57 years (interquartile range (IQR): 51–67). 12 cases had hip resurfacings (HRs) and 7 cases had a MOM total hip replacement (THR). The timespan between MARS MRI and USS was on average 122 days (SD 98; 95% CI: 69–156). The period of time elapsed since primary operation ranged from 30 to 142 months (median 61; IQR: 41–77) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical data on the study cohort

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OA | 62 | 37 | HR | Cormet | 17 |

| 2 | SUFE | 48 | 101 | HR | BHR | 19 |

| 3 | OA | 68 | 142 | HR | BHR | 19 |

| 4 | OA | 57 | 85 | HR | – | 28 |

| 5 | OA | 51 | 61 | HR | BHR | 30 |

| 6 | – | 56 | 61 | HR | Cormet | 35 |

| 7 | – | 60 | 64 | HR | Cormet | 17 |

| 8 | – | 67 | 30 | THR | Biomet (48 mm) | 13 |

| 9 | AVN | 58 | 35 | HR | Cormet | 30 |

| 10 | OA | 63 | 77 | HR | Cormet | 18 |

| 11 | – | 71 | 35 | THR | Biomet (40 mm) | 16 |

| 12 | – | 55 | 42 | THR | Wright | 28 |

| 13 | – | 35 | 41 | THR | ASR XL | 11 |

| 14 | – | 57 | 42 | THR | Cormet (54 mm) | 39 |

| 15 | OA | 69 | 44 | THR | Cormet (44 mm) | 32 |

| 16 | – | 51 | 62 | HR | Cormet | 23 |

| 17 | – | 71 | 76 | HR | Cormet | 35 |

| 18 | – | 48 | 79 | THR | Cormet (44 mm) | 31 |

| 19 | – | 53 | 62 | HR | – | 40 |

| Median | 57 years | 61 months | ||||

| Mean | 25 (SD 9) | |||||

| (IQR: 51–67) | (IQR: 41–77) | (CI: 21–29) |

SD: standard deviation; CI: 95% confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range.

A Patient no.

B Diagnosis

OA: osteoarthritis;

SUFE: slipped upper femoral epiphysis;

AVN: avascular necrosis;

C Age, years

D Time since primary operation, months

E Prosthesis type

HR: hip resurfacing;

THR: total hip replacement;

F Prosthesis model (femoral head size)

BHR: Birmingham hip resurfacing;

ASR XL: articular surface replacement;

G Oxford hip score (out of 48)

Ultrasound scanning protocol

We used the Toshiba Aplio A500 Ultrasound System (Toshiba Medical Systems, Zoetermeer, the Netherlands). Scans were performed by 2 consultant musculoskeletal (MSK) radiologists (KS and AKL) who were blind regarding clinical details and who reached a consensus on the result. Both operators were present during each scan, with the same operator scanning and the other observing throughout the study. The scanning technique was systematic over the anterior, lateral, and posterior periprosthetic soft tissues for both native hips and prosthetic hips. The presence or absence of pseudotumor, joint effusion, muscle atrophy (gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and iliopsoas), and tendon pathology was reported at the time of scanning (Siddiqui et al. 2013).

A hip joint effusion was defined as a distance greater than 4 mm between the femoral neck and neocapsule (Nishii et al. 2012). Pseudotumors were defined by location (anterior, posterior, or lateral), type classification (1, 2, or 3), and size (in the anterior-posterior, medial-lateral, and cranial-caudal axes). Muscle atrophy was graded from 0 (no change) to 3 (greater than 70% reduction in size with marked fatty replacement) (Appendix B, see Supplementary data). The midpoint position of the gluteal muscles during lateral scanning was used to record diameter. Tendon diameter (normal or thin), character (hyperechoic, normal, or hypoechoic), and presence of ossification were reported (Siddiqui et al. 2013).

Metal artifact reduction sequence (MARS) MRI protocol

A 1.5 tesla scanner (Magnetom 1.5T; Siemens Medical, Erlangen, Germany) with an optimized metal artifact reduction sequence was used, including axial T1-weighted, axial T2-weighted, coronal T1-weighted, and sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echoes and coronal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences (Hart et al. 2009, Sabah et al. 2011). The images were reported independently by a consultant MSK radiologist (KS) who was blind regarding clinical details and USS results. The presence or absence of pseudotumor, muscle atrophy (gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and iliopsoas), tendon avulsion, and other pathologies (including muscle edema, fracture, infarction, and metastasis) were reported as previously described (Sabah et al. 2011, Hart et al. 2012).

Validation at revision surgery

Pathological imaging findings were validated during surgery for patients who subsequently underwent revision arthroplasty. Hip neocapsule specimens were collected at the time of surgery and routine histological analysis was performed by a consultant histopathologist.

Statistics

The diagnostic test characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy) of USS for the detection of pseudotumors, muscle atrophy (gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and iliopsoas), and abnormal tendons (thin or abnormal signal for the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and iliopsoas) using MARS MRI as the reference were calculated following contingency table analysis. Agreement between USS and MARS MRI was measured using Cohen’s weighted kappa statistic, κ, with a linear weighting scheme so that the degree of disagreement between pairs of readings was proportional to the number of grades apart. Weighted kappa values can vary from –1 (complete disagreement) through 0 (chance agreement) to +1 (complete agreement). Intermediate kappa values were interpreted with the criteria described by Landis and Koch (1977) where 0 < κ ≤ 0.20 = slight agreement, 0.20 < κ ≤ 0.40 = fair agreement, 0.40 < κ ≤ 0.60 = moderate agreement, 0.60 < κ ≤ 0.80 = substantial agreement, and 0.80 < κ < 1 = almost perfect agreement (Landis and Koch 1977). All cross-tabulations used are shown in Appendix C (see Supplementary data).

Results

Pseudotumors

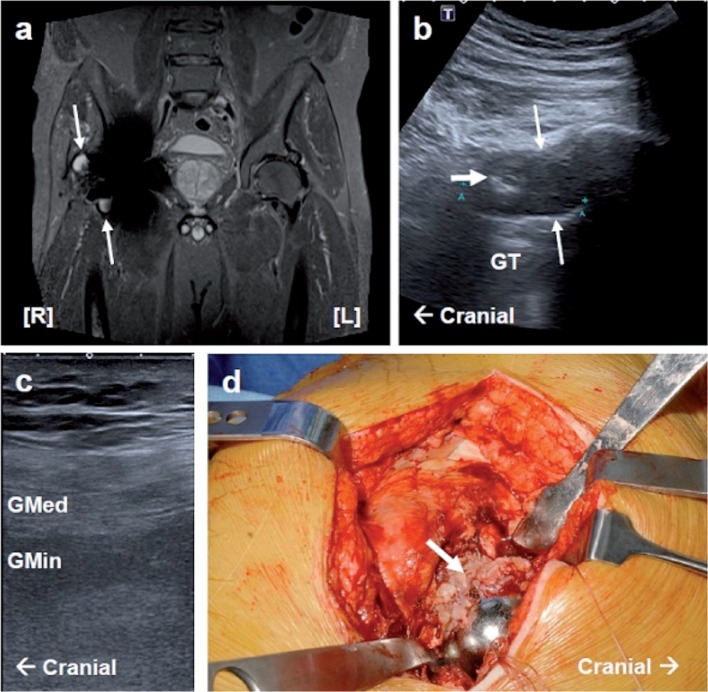

USS identified pseudotumors in 10 patients, which were mainly cystic in character (type 1 or 2). The prevalence rate of pseudotumors in USS was 0.5 (n = 10/19; CI: 0.3–0.8). Most lesions (7/13) were found anterior to the prosthesis and the minority were found either in the lateral (3/13) or posterior (3/13) loci (Appendix D, see Supplementary data). MARS MRI found 13 patients with pseudotumors, including type 1, 2a, and 2b. Most lesions (9/16) were anterior to the prosthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Case 1. MARS MRI, ultrasound, and intraoperative images of a pseudotumor and gluteal muscle atrophy. a. A coronal STIR sequence MARS MRI section showing a right anterior (type-IIa) and lateral (type-IIb) pseudotumor (white arrows). In addition, right-sided fatty atrophy of the gluteus medius and minimus muscles (grade 3) can be seen. b. Lateral longitudinal USS showing a large cystic pseudotumor (type 2) with a thickened wall and upper solid focal region (thick white arrow). c. Lateral longitudinal USS of the right gluteus medius and minimus muscle showing fatty atrophy (reported as grade 2). d. Photograph taken during revision surgery showing a florid inflammatory reaction to the right hip neocapsule (thick white arrow).

GT: greater trochanter; Gmed: gluteus medius; Gmin: gluteus minimus. Pathology is indicated by white arrows.

To calculate the diagnostic characteristics, we classified each of the 19 patients as having or not having a pseudotumor, independent from loci, as lesions are likely to communicate through the joint capsule (Appendix D, see Supplementary data). The prevalence rate of pseudotumors on MARS MRI was 0.7 (n = 13/19; CI: 0.5–0.9) for our sample population. Sensitivity (69%, CI: 39–91), specificity (83%, CI: 36–97), PPV (90%, CI: 55–98), NPV (56%, CI: 21–86), and accuracy rate (74%) were obtained (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ultrasound diagnostic test characteristics a. Values stated are percentages (confidence interval)

| Prevalence | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value (PPV) | Negative predictive value (NPV) | Accuracy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudotumor detection | Pseudotumors | 68 (43–87) | 69 (39–91) | 83 (36–97) | 90 (55–98) | 56 (21–86) | 74 |

| Muscle atrophy | Gluteus medius | 100 (82–100) | 47 (24–71) | – | 100 (66–100) | 0 (0–31) | 47 |

| (≥ grade-1 atrophy) | Gluteus minimus | 95 (74–99) | 50 (26–74) | 100 (17–100) | 100 (66–100) | 10 (2–45) | 53 |

| Iliopsoas | 0 (0–18) | – | 74 (49–91) | 0 (0–52) | 100 (77–100) | 74 | |

| Tendon abnormality | Gluteus medius | 42 (C20–66) | 63 (CI 25–91) | 55 (24–83) | 50 (19–81) | 67 (30–92) | 59 |

| (either thinning, abnormal signal, or both) | Gluteus minimus | 37 (16–62) | 57 (CI 19–90) | 67 (35–90) | 50 (16–84) | 73 (39–94) | 63 |

| Iliopsoas | 5 (1–26) | 100 (CI 17–100) | 67 (41–87) | 14 (2–58) | 100 (73–100) | 68 |

The diagnostic test characteristics are shown for ultrasound during the detection of pseudotumors, muscle atrophy, and tendon abnormality using MARS MRI as the gold-standard reference.

Joint effusion

A joint effusion was detected in 10 of 19 patients. Pseudotumors were common in patients with a joint effusion (n = 7/10). The average effusion size was 8.1 mm (SD 3.8, CI: 5.8–10.4). No effusions were detected on MARS MRI, as the metal artifact obscured the image adjacent to the prosthesis.

Muscle atrophy and tendinous pathology

The weighted kappa value for the agreement between USS and MARS MRI for the gluteus medius muscle grades showed slight agreement, κ = 0.25, which was greater than chance agreement (p = 0.008). The weighted percentage of agreement was 68%. The weighted kappa value for the agreement between modalities for the gluteus minimus muscle showed slight agreement (κ = 0.10; p = 0.2). The weighted percentage of agreement was 58%. It was not possible to compute the kappa statistic to assess the agreement between modalities for iliopsoas muscle grading because all the individuals assessed with MARS MRI were rated grade 0. The weighted percentage agreement was 82% (Table 3).

Histological validation

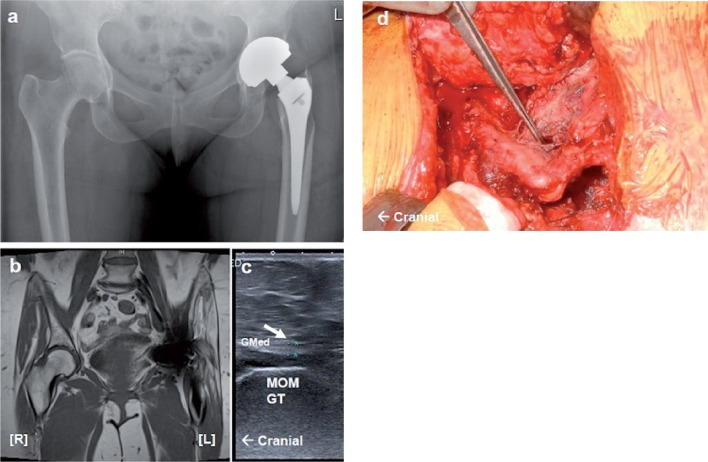

5 patients subsequently underwent revision surgery during this study and hip neocapsule samples were collected for histology. In all cases, the presence of musculotendinous pathology (including muscle atrophy and tendon discontinuity) was verified by the surgeon. Surgical reports showed good correlation with cross-sectional image findings (Figures 1 and 2). Samples from all patients showed reactive changes to the prosthesis suggestive of ALVAL (Davies et al. 2005).

Figure 2.

Case 2. Radiography, MARS MRI, ultrasound, and intraoperative images of gluteal musculotendinous damage. a. A pelvic radiograph showing a left-sided MOM total hip replacement in situ and highlighting the absence of the greater trochanter region of the left proximal femoral bone. b. A T1-weighted MARS MRI image in coronal section showing left-sided fatty atrophy of the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles (grade 3) and thinning of the gluteus minimus tendon. c. Left lateral USS over the greater trochanter showing thin and hypoechoic tendons for the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles. d. Photograph taken during revision surgery showing erosion of the left greater trochanter and gluteus medius muscle.

MOM GT: the MOM femoral component (greater trochanter region); Gmed: gluteus medius tendon. Pathology is indicated by white arrows.

Discussion

To our knowledge, no previous studies have directly compared the diagnostic performance of USS with that of MARS MRI in patients with MOM hips.

Pseudotumors

We found poor sensitivity and specificity of USS for pseudotumor detection when compared to MARS MRI. The false negative cases are often attributed to ultrasound image quality and operator dependence. The spatial resolution of ultrasound images diminishes with depth, and although this effect can be reduced using a lower frequency transducer to improve penetration, it is still often difficult to fully appreciate deeper anatomical structures. The lateral aspect of the hip lies superficially and we would expect few lesions to be missed in this region. This was not the case in our study. We suspect that the lateral and anterior lesions were missed as they were particularly small and may have been easily compressed during scanning, increasing the likelihood of the operator missing the lesion. The small anterior lesion missed on MARS MRI was directly adjacent to the prosthesis and could therefore have been obscured by the residual metal artifact. During posterior scanning, the large muscle bulk of the gluteus maximus may obscure the view or when scanning overweight patients; however, pseudotumors were found least frequently in this region (Nishii et al. 2012).

Ultrasound is an operator-dependent modality, and the importance of experienced sonographers during scanning following hip arthroplasty has already been recognized (Douis et al. 2012). We maximized the sensitivity of USS by employing 2 experienced MSK radiologists to report by mutual agreement; they were blinded as to clinical details and any previous image reports.

Ultrasound had a reasonable PPV (90%) but a poor NPV (56%) for detection of pseudotumors. USS does not therefore appear to be a useful test to exclude pseudotumors in groups with high prevalence. However, given its widespread availability, it may be a useful initial investigation (Fang et al. 2008, Pandit et al. 2008).

We obtained a prevalence of pseudotumors of 68% in patients with painful MOM hip arthroplasty. This high figure and variability in previously reported figures represents the broad spectrum of pathology included within the umbrella term ‘pseudotumor’. Further longitudinal investigation is required to establish a clinical correlation with lesion type (Hart et al. 2012).

Joint effusions

Joint effusions were commonly detected in patients with painful MOM hips and they were more common in patients with pseudotumors. Joint effusions may be an early inflammatory reaction to metal debris, and capsular disruption may lead to extra-articular collections. The fluid has been suggested to collect along lines of least resistance (Fang et al. 2008), associated with the surgical approach used (Sabah et al. 2011).

Muscle atrophy

A high prevalence of muscle wasting has been found in patients with painful MOM hips using MARS MRI, including the hip abductors (gluteus medius and gluteus minimus; Figure 1c) and the short external rotators (piriformis, obturator internus, and obturator externus) (Sabah et al. 2011). The present study is the first to investigate the use of USS for assessment of hip muscle atrophy in patients with MOM hips. Pilot data showed that the short external rotators cannot be reliably identified using USS, due to the depth of the muscles during posterior scanning, so they were were excluded from this study. Recent investigations now suggest that wasting of these muscles is an inevitable consequence of the posterior surgical approach rather than being due to metal-particle disease (Yanny et al. 2012).

We investigated the extent of muscle atrophy in the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and iliopsoas muscles using USS. The prevalence of atrophy (grade 1 or more) was 19/19, 18/19, and 0/19, respectively, supporting previous studies which found that hip abductor wasting is a common pathological finding (Sabah et al. 2011). We found that there was only ‘slight’ agreement in abductor muscle grading between the 2 modalities. A difference in the extent of muscle contraction and the position used to measure contralateral muscle diameter can lead to variability. We attempted to reduce this error by defining a standardized location for the measurement of each muscle; however, this partially limited grading to a single section of the muscle. MARS MRI remains advantageous, as both the deep muscles and the superficial muscles can be fully assessed and easily compared to the contralateral side using standardized positioning.

Tendinous pathology

Both MARS MRI and USS can be used to assess the tendinous attachment of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and iliopsoas muscles (Garcia et al. 2010). Gluteal tendinosis or avulsion may present as lateral greater trochanteric pain (Figure 2), and iliopsoas tendinosis due to impingement can lead to groin pain. It has been suggested that metal-particle disease progression involves gluteal muscle edema followed by muscle atrophy and tendon abnormality (Yanny et al. 2012). We found a tendon pathology of the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tendons in about half of the patients each. USS was able to detect tendon thinning, signal abnormality, and ossification (Figure 2c) but a larger cohort would be needed to accurately interpret the diagnostic sensitivity.

Limitations

We used the STARD checklist to facilitate the assessment of bias and generalizability of this study (Smidt et al. 2005) (Appendix A, see Supplementary data). The results of the present study appear to be generalizable to the wider population of MOM hip arthroplasties, as we included all patients who would require investigation under the regulatory guidelines for the UK. These regulatory guidelines are similar to those recommended in the USA and in other European countries. We acknowledge the limitations of the population size in our study, but we feel that this did not compromise meaningful statistical analysis as we used a population with a high prevalence of pathologies.

The rate and nature of progression of pseudotumors remain largely unknown, with only one longitudinal comparison published to date (Almousa et al. 2013). That study found that after a 2-year follow-up in 20 patients with asymptomatic lesions, the majority increased in size and a minority diminished in size or resolved. It may be that the size or structure of a lesion changed between imaging, but we minimized this effect without compromising the size of the study by restricting MARS MRI scans to within 1 year. The time difference between imaging was 4 months on average.

We did not calculate the reproducibility of testing, as we deemed it inappropriate under the circumstances to have each patient undergo multiple ultrasound scans. Assessment of inter-observer variation error was therefore beyond the scope of the study.

Surgical validation is the ideal reference, but this standard was not feasible for all patients as most did not undergo revision surgery within the time frame of the study. However, cross-sectional imaging findings had good correlation with surgical reports for all patients who underwent revision arthroplasty. Long-term follow-up is required to assess the correlation of revision surgery with outcome.

The MAR sequence used in this study was the gold standard available in the UK at the time of participant recruitment. Advanced MAR techniques that also employ view-angle tilting and robust slice encoding will become more widely available in the near future, and will improve the diagnostic capabilities of MRI in the region immediately adjacent to the prosthesis. This may explain the inability of MRI to detect small lesions adjacent to the prosthesis and joint effusions in our study.

Conclusion

This was a blind prospective study to validate USS and compare it to MARS MRI in patients with MOM hips. We found poor agreement between these modalities for detection of pseudotumors, muscle atrophy, and joint effusion. USS had poor sensitivity for pseudotumors, detecting only two-thirds of lesions. We recommend that MARS MRI be used first-line for assessment of the periprosthetic soft tissues because we consider that muscle atrophy is a key trigger for intervention, and this is not easily seen on USS. In addition, MARS MRI provides anatomical information that the surgeon can visualize for preoperative planning, it can detect other pathologies such as metastatic disease, and can be used for longitudinal comparison. Ultrasound should be used when MARS MRI is poorly tolerated, contraindicated, or unavailable.

Supplementary data

Appendices A–D are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 7013.

Acknowledgments

Guarantors of integrity of the entire study (AJH, KS, AKL), study concepts and design (IAS, SAS), literature research (IAS), clinical studies (KS, AKL, IAS), experimental studies and data analysis (IAS), statistical analysis (SC, IAS), manuscript preparation (IAS), and manuscript editing (all authors).

AJH has a contract with de Puy for clinical advice to patients with ASR hips. De Puy had no involvement in planning of the study, data collection, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

References

- Almousa SA, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP, Garbuz DS. The Natural History of Inflammatory Pseudotumors in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2013;471(12):3814–21. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2944-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal BS, Lowe JA. Muscle damage in minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: MRI evidence that it is not significant . Instr Course Lect. 2008;57:223–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AP, Willert HG, Campbell PA, Learmonth ID, Case CP. An unusual lymphocytic perivascular infiltration in tissues around contemporary metal-on-metal joint replacements . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87(1):18–27. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.00949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douis H, Dunlop DJ, Pearson AM, O’Hara JN, James SL. The role of ultrasound in the assessment of post-operative complications following hip arthroplasty . Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:9, 1035–46. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CS, Harvie P, Gibbons CL, Whitwell D, Athanasou N A, Ostlere S. The imaging spectrum of peri-articular inflammatory masses following metal-on-metal hip resurfacing . Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:8, 715–22. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA (US Food and Drug Administration). Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Open Panel Meeting [Online]. June 2012 [Cited 2012 Oct 08] Available from: http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials /MedicalDevices/MedicalDevicesAdvisoryCommittee/OrthopaedicandRehabilitationDevicesPanel/ucm309184.htm .

- Foldes K, Gaal M, Balint P, Nemenyi K, Kiss C, Balint GP, Buchanan WW. Ultrasonography after hip arthroplasty . Skeletal Radiol. 1992;21:5, 297–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00241767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia FL, Picado CH, Nogueira-Barbosa MH. Sonographic evaluation of the abductor mechanism after total hip arthroplasty . J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:3, 465–71. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AJ, Sabah S, Henckel J, Lewis A, Cobb J, Sampson B, Mitchell A, Skinner JA. The painful metal-on-metal hip resurfacing . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91:6, 738–44. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B6.21682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AJ, Satchithananda K, Liddle AD, Sabah SA, McRobbie D, Henckel J, Cobb JP, Skinner JA, Mitchell AW. Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses: a case-control study using three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012;94:4, 317–25. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YM, Ostlere SJ, McLardy-Smith P, Athanasou NA, Gill HS, Murray DW. “Asymptomatic” pseudotumors after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: prevalence and metal ion study . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:4, 511–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data . Biometrics. 1977;33:1, 159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle AD, Satchithananda K, Henckel J, Sabah SA, Vipulendran KV, Lewis A, Skinner JA, Mitchell AW, Hart AJ. Revision of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in a tertiary center: a prospective study of 39 hips with between 1 and 4 years of follow-up . Acta Orthop. 2013;84:3, 237–45. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.797313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SS, Surrey D, Nazarian LN. Common sonographic findings in the painful hip after hip arthroplasty . J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:2, 301–12. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MHRA (Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency). Medical Device Alert: All metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements (MDA/2012/036). [Online] 2012 [Cited 2012 Oct 08] Available from: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/dts-bs/documents/medicaldeviceale rt/con155767.pdf .

- Nishii T, Sakai T, Takao M, Yoshikawa H, Sugano N. Ultrasound screening of periarticular soft tissue abnormality around metal-on-metal bearings . J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:6, 895–900. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, Ostlere S, Athanasou N, Gill HS, Murray DW. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008;90:7, 847–51. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabah SA, Mitchell AW, Henckel J, Sandison A, Skinner JA, Hart AJ. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in painful metal-on-metal hips: a prospective study . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:1, 71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui IA, Sabah SA, Satchithananda K, Lim AK, Henckel J, Skinner JA, Hart AJ. Cross-sectional imaging of the metal-on-metal hip prosthesis: the London ultrasound protocol . Clin Radiol. 2013;68(8):e472–8. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smidt N, Rutjes AW, van der Windt DA, Ostelo RW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality of reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies . Radiology. 2005;235( 2):347–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2352040507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet. 2012;379:9822, 1199–204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofka CM, Haddad ZK, Adler RS. Detection of muscle atrophy on routine sonography of the shoulder . J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:8, 1031–4. doi: 10.7863/jum.2004.23.8.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert HG, Buchhorn GH, Fayyazi A, Flury R, Windler M, Koster G, Lohmann CH. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints. A clinical and histomorphological study . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87:1, 28–36. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.A.02039pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanny S, Cahir JG, Barker T, Wimhurst J, Nolan JF, Goodwin RW, Marshall T, Toms AP. MRI of aseptic lymphocytic vasculitis-associated lesions in metal-on-metal hip replacements . AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:6, 1394–402. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.