Abstract

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast is used for various indications. Contrary to computed tomography as a staging tool, breast MRI focuses on the breast parenchyma and axilla. In spite of narrow field of view, many structures such as the anterior portion of the lungs, mediastinum, bony structures and the liver are included which should not be neglected because the abnormalities detected on the above structures may influence the staging and provide a clue to systemic metastasis, which results in the change of treatment strategy. The purpose of this pictorial essay was to review the unexpected extra-mammary findings seen on the preoperative breast MRI.

Keywords: Breast, Extra-mammary, Magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Recently, breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been accepted as an important tool for the characterization of breast lesions (1), and its clinical use has become more widespread such as for the screening in high risk groups and in women with augmentation or cosmetic injection, local staging in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, evaluation of positive surgical margin at initial excision and for the response monitoring to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Notwithstanding a relatively small field of view (FOV) and primarily focusing on the mammary glands and axillary regions, a part of other structures such as the lung, mediastinum, upper abdomen and bony thorax are included in breast MRI also (2, 3). Preoperative breast MRI is usually used for local staging such as the assessment of breast cancer extend and the evaluation of the contralateral breast, however, the lesions detected on the extra-mammary structures in that FOV can influence the staging. Irrespective of the nature of extra-mammary findings (2, 3), the detection of those findings is important, because it can be a clue of systemic metastasis or concurrent malignancy. Therefore, radiologists should pay attention not only to mammary and axillary regions but also to all the structures included in the FOV of breast MRI. The purpose of this pictorial essay was to review extra-mammary findings observed in preoperative breast MRI examinations of breast cancer patients.

Lung Lesions

It is known that incidentally detected lesions of lung parenchyma are highly likely to be malignant compared to lesions in other structures (4). Unexpected pulmonary nodules detected on breast MRI in patients with breast cancer are identified as one of a large spectrum of abnormalities ranging from benign to malignant lesions. The rates of these abnormalities have been reported with 34.2-75% for metastatic lesions, 11.5-48.1% for primary lung cancer and 13.5-17.7% for benign lesions (5). CT and MRI share similar criteria for raising suspicion of a malignant nature of lung nodules, such as multifocality and increase in the size and number of the nodules on follow-up examinations (6). A CT is advantageous in discriminating the nature of lung nodule(s) concerning the assessment of shape, border and density. Therefore, a CT should be considered for the differential diagnosis if the incidental lung nodule(s) are detected on breast MRI (6). We have found three cases of lung abnormalities (Figs. 1,2,3) on breast MRI. In two of them were the treatment plans changed after MRI. In one case was an incidental lung mass found in the right upper lobe (Fig. 1A) on breast MRI and this did not change on the two-year follow-up chest CT (Fig. 1B). In the second case, incidental pleural lesions with pleural effusion which were confirmed as metastases were found in the left hemithorax (Fig. 2A, B). A chest CT showed multiple pleural masses with a large amount of pleural effusion (Fig. 2C). The plan of direct operation was changed to chemotherapy after this detection. In the third case, primary lung cancer was confirmed and a simultaneous lobectomy was conducted (Fig. 3).

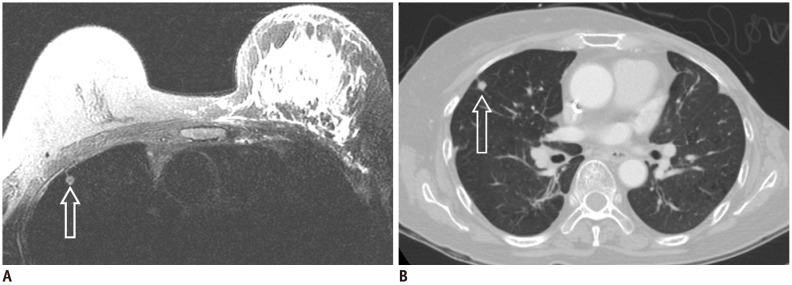

Fig. 1.

52-year-old female with left breast cancer with no changes in solitary pulmonary nodule on 24 months follow-up chest CT.

A. Inflammatory breast cancer was confirmed in left breast and solitary lung nodule was incidentally found in right upper lobe (hollow arrow) on T2-weighted image. B. Chest CT with lung setting shows solitary pulmonary nodule (hollow arrow) in right upper lung which shows no significant change 24 months after initial study (A).

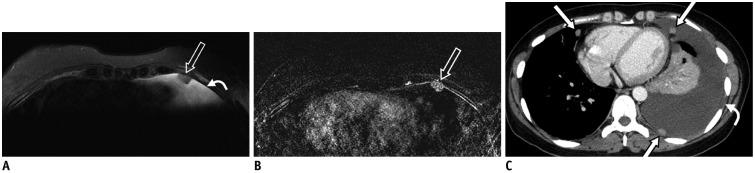

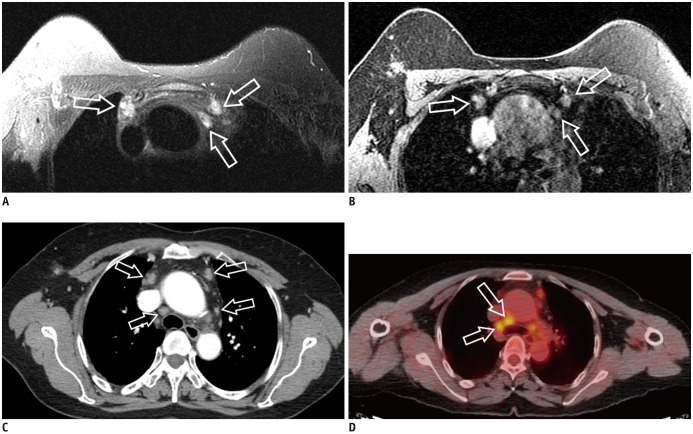

Fig. 2.

40-year-old female with right breast cancer and pleural metastases.

A. Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed image shows pleural nodule (hollow arrow) with pleural effusion (curved arrow) at left hemithorax. B. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted subtracted image shows pleural thickening with enhancing pleural nodule (hollow arrow). C. Contrast-enhanced chest CT shows several enhancing pleural nodules (white arrows) with pleural thickening and large amount of pleural effusion (curved arrow), suggestive of pleural metastases.

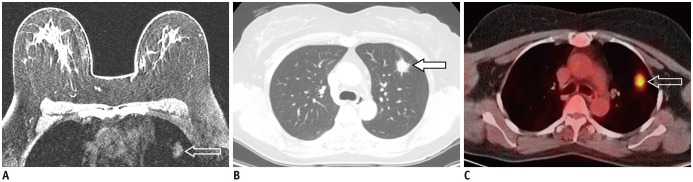

Fig. 3.

56-year-old female with left breast cancer and primary lung cancer.

A. Pre-contrast axial T1-weighted fat-suppressed image shows irregular-shaped (hollow arrow) mass of approximately 3.1 cm size at left upper lobe. B. Chest CT with lung setting shows irregular shaped mass (arrow) at left upper lobe. Mass was confirmed as adenocarcinoma via left upper lobectomy. C. Hot uptake (standardized uptake value = 10.5) was seen at left upper lobe on positron emission tomography-CT scan (hollow arrow).

Mediastinal Lesions

When a unexpected mediastinal mass is found, the differential diagnosis can be narrowed based on the location within the mediastinal compartment and by age (7). Most masses (60%) located in the mediastinum are thymomas, neurogenic tumors or benign cysts. As most mediastinal cysts are developmental in origin (Fig. 4), there is no need to delay a breast cancer operation. Many mediastinal lesions, such as mediastinal lymph nodes, vascular abnormalities (e.g., aneurysms) and normal structures (e.g., pericardial recess, pericardial fat pad) can be observed on breast MRI. Normal structures can be mistaken as mediastinal mass as we obtain breast MRI with the patient in a prone position. For example, prominent pericardial fat can be seen as a contour-bulging mass in the anterior mediastinum (Fig. 5A, B). The bulging contour can be changed to a straight line on CT images (Fig. 5C) by supine positioning the patient. In addition, as this is a fat pad around the pericardium, the fat signal drops with a fat-suppressed scan. Mediastinal lymph nodes certainly represent the most common cause of mediastinal masses. A positron emission tomography (PET) for systemic evaluation should be considered if mediastinal lymph nodes are found on breast MRI (Fig. 6A, B) and CT for local staging (Fig. 6C), because the management strategy may be changed according to the status of regional lymph nodes (Fig. 6D).

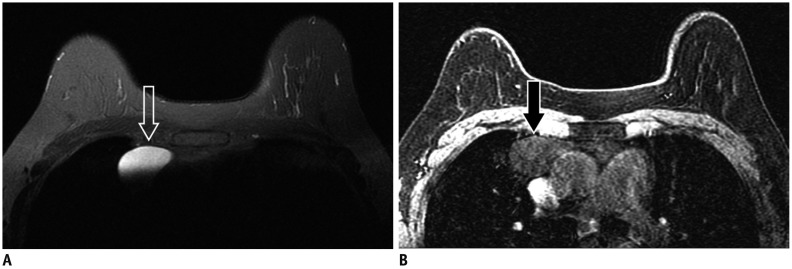

Fig. 4.

58-year-old female with right breast cancer and thymic cyst.

A, B. Circumscribed mass (hollow arrow) with high signal intensity on T2-weighted fat suppression (A) and low signal intensity (black arrow) on T1-weighted image (B) which is considered as thymic cyst is noted in anterior mediastinum.

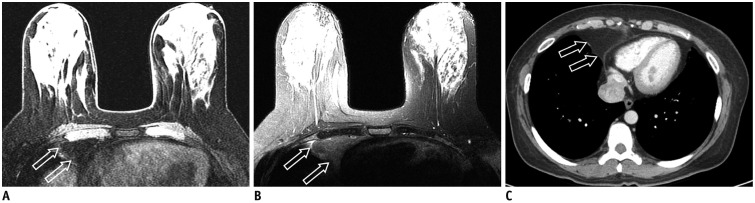

Fig. 5.

50-year-old female with right breast cancer and prominent extrapericardial fat pad.

A. Axial T1-weighted fat-suppressed image shows contoured bulging mass (hollow arrows) in anterior mediastinum with signal intensity similar to fat. B. Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed image shows large mass (hollow arrows) at right side of anterior mediastinum. Note signal intensity of mass is similar to that of surrounding fatty tissue. C. Contrast-enhanced chest CT shows homogeneous fat-attenuation mass (hollow arrows) with straightened margin at right heart border, which is due to positional change. CT scans were performed in supine position and MRI in prone position.

Fig. 6.

62-year-old female with right breast cancer and multiple mediastinal lymph nodes metastases.

A, B. Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed (A) and T1-weighted images (B) show several enlarged lymph nodes (hollow arrows) in anterior mediastinum with suspected metastatic lymph nodes (hollow arrows). C. Contrast-enhanced chest CT also shows mediastinal lymph node enlargement (hollow arrows). D. Hot uptakes were seen in anterior mediastinal lymph nodes including upper paratracheal lymph nodes (standardized uptake value = 5.1) on positron emission tomography-CT scan (hollow arrows).

Liver Lesions

The most frequent extra-mammary findings on breast MRI are hepatic lesions (2). Most hepatic lesions are benign and the probability of a hepatic lesion being malignant is less than 20% (2, 8). Further examinations must rely on any suspicious characteristics observed on the MRI, such as the presence of multiplicity (Figs. 7, 8), indistinct margins (Fig. 8) or rim enhancement (Fig. 8) on both, unenhanced and enhanced sequences. Further evaluation is not necessary if the lesions have typical findings such as those of a simple hepatic cyst, which show a high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 7A) and no internal or rim enhancement (Fig. 7B) after contrast injection (9). However, further evaluation should be conducted (e.g., nuclear scan or CT with a liver protocol or MRI with a hepatobiliary contrast agent) if the findings are not typical for benign lesions. We report a case of left breast cancer which was widely excised at another hospital. The MRI showed numerous high signal-intensity masses on T2-weighted images, which lesions were not enhanced at all after contrast injection and suggestive of hepatic cysts. Then a subsequent lumpectomy of the left breast followed (Fig. 7). In another case with right breast cancer, multiple masses with high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 8A) and low signal intensity on T1-weighted images (Fig. 8B) were seen, which exhibited enhancement after contrast injection (Fig. 8C, D). So, operation was cancelled and treatment plan was changed to chemotherapy.

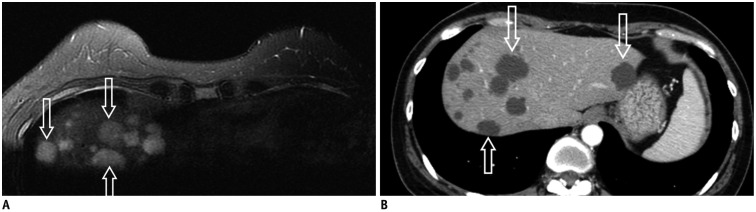

Fig. 7.

44-year-old female with left breast cancer and multiple hepatic cysts.

A. Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed image shows multiple masses with high signal intensities (hollow arrows) in liver. B. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows multiple low-attenuation masses (hollow arrows) without internal or rim enhancement of liver which are suggestive of hepatic cysts.

Fig. 8.

52-year-old female with right breast cancer and multiple hepatic metastases.

A-C. Liver contains several masses with indistinct margin (hollow arrows) with high signal intensity on T2-weighted image (A), low signal intensity on T1-weighted image (B) and nodular rim enhancement (hollow arrows) on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image (C). D. Contrast-enhanced liver CT shows multiple peripheral rim-enhancing nodules (hollow arrows) in liver which are suggestive of hepatic metastases.

Bony Lesions

Bony lesions are occasionally observed on breast MRI. More attention should be given to bony lesions, because bone is one of the most common sites for breast cancer metastasis (2, 10, 11). An early detection of metastatic disease may change treatment plans and offer a better chance of survival and quality of life. Approximately 65-75% of patients with metastatic disease from breast cancer have bone metastases (10). In a recent study, bone lesions accounted for 7% (20/285) of all incidental extra-mammary findings in breast cancer patients, and the positive predictive value for MRI to detect a metastatic lesion was high if it was located within the bone (89%) (11). Signal changes in the marrow on T1-weighted images are the most frequently observed findings. However, these findings are nonspecific and observed on both, benign (e.g., inflammation or stress fractures) (Fig. 9) and malignant lesions (Fig. 10). Typical features of bone metastases include a low signal intensity on T1- and a high signal intensity on T2-weighted images with peripheral edema of the bone marrow (Fig. 10) (2). Therefore, MRI with a bone protocol, bone scan or PET should be recommended if bony lesions were detected on breast MRI in patients with breast cancer.

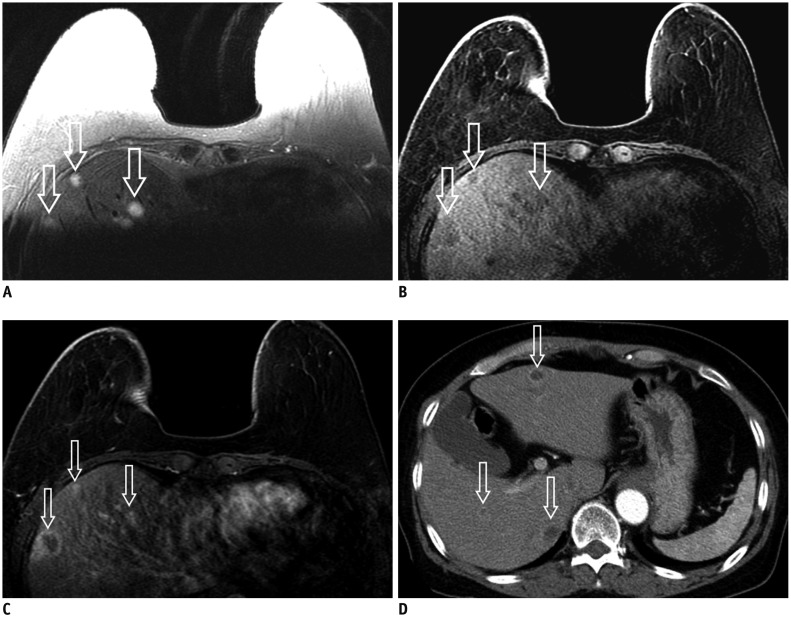

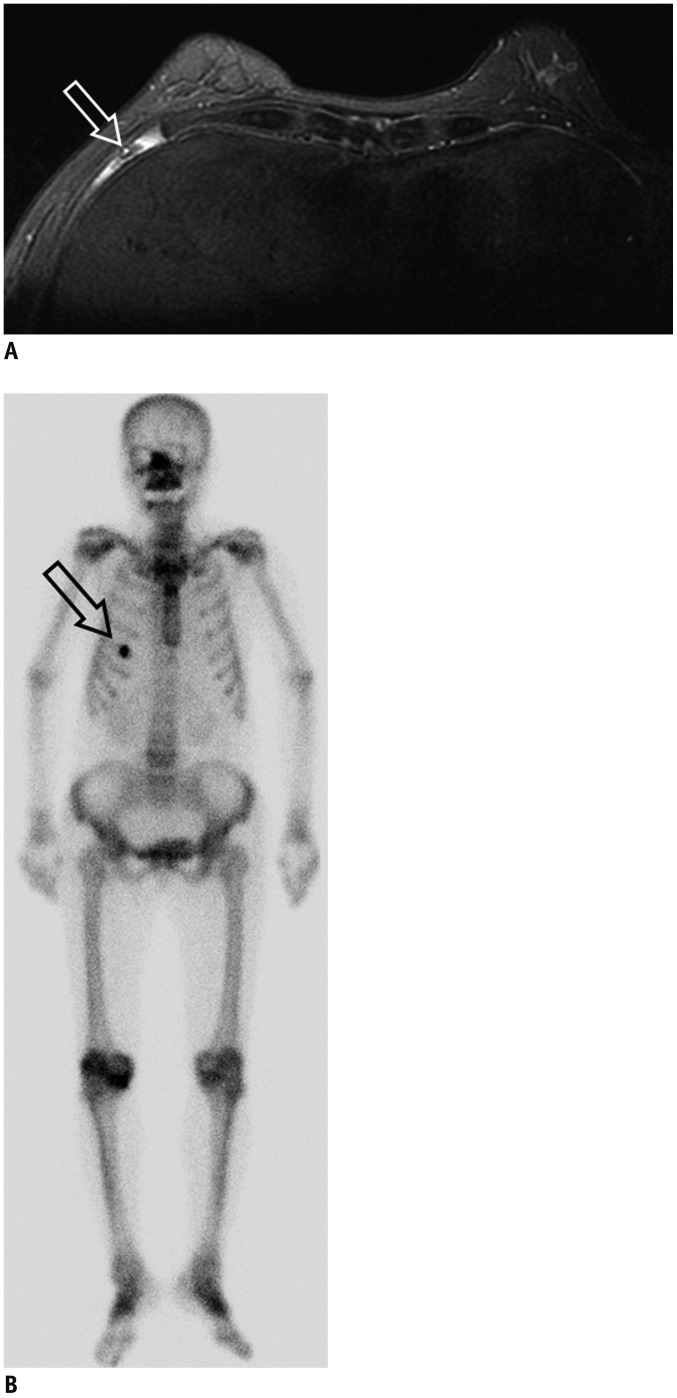

Fig. 9.

65-year-old female with right breast cancer and rib fracture.

A. Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed image shows high-signal marrow change (hollow arrow) in anterior arch of right 5th rib. B. Bone scan shows focal hot uptake at anterior arch of right 5th rib (hollow arrow). Patient had history of fall down injury in anterior thorax 5 months before and focal hot uptake on bone scan disappeared at 12 months follow-up.

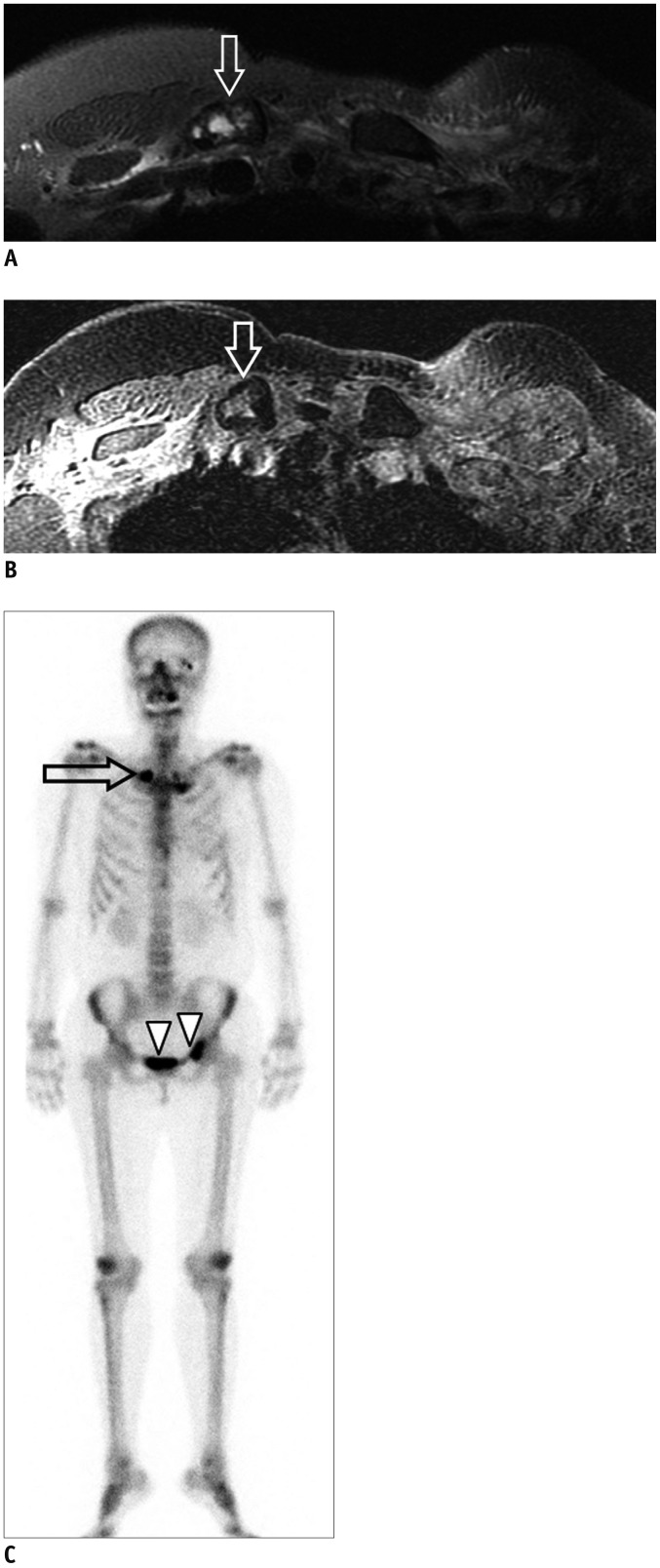

Fig. 10.

47-year-old female with left breast cancer and clavicle metastasis.

A, B. Right clavicle shows high signal intensity on T2-weighted fat-suppressed (A) and expansile marrow change on T1-weighted images (B) (hollow arrows). C. Bone scan shows multiple hot uptakes in right mid-clavicle (hollow arrow) and left pelvic bone (arrowheads) which are suggestive of bone metastases.

CONCLUSION

Breast MRI is one of the most useful imaging modalities for the detection and characterization of breast lesions. With the widespread use of breast MRI, incidental extra-mammary findings are detected more often than before. Radiologists should pay attention not only to breasts but also to extra-mammary areas, because the prevalence of malignant incidental extra-mammary findings is not negligible and these might alter the treatment plan, particularly for breast cancer patients. The awareness of extra-mammary findings on breast MRI may lead to an early detection and appropriate management of extra-mammary findings in patients with breast cancer.

References

- 1.Vassiou K, Kanavou T, Vlychou M, Poultsidi A, Athanasiou E, Arvanitis DL, et al. Characterization of breast lesions with CE-MR multimodal morphological and kinetic analysis: comparison with conventional mammography and high-resolution ultrasound. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinaldi P, Costantini M, Belli P, Giuliani M, Bufi E, Fubelli R, et al. Extra-mammary findings in breast MRI. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:2268–2276. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rausch DR. Spectrum of extra-mammary findings on breast MRI: a pictorial review. Breast J. 2008;14:592–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang EY, Johnson W, Karamlou K, Khaki A, Komanapalli C, Walts D, et al. The evaluation and treatment implications of isolated pulmonary nodules in patients with a recent history of breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2006;191:641–645. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashid OM, Takabe K. The evolution of the role of surgery in the management of breast cancer lung metastasis. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:420–424. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.07.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, Herold CJ, Jett JR, Naidich DP, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237:395–400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laurent F, Latrabe V, Lecesne R, Zennaro H, Airaud JY, Rauturier JF, et al. Mediastinal masses: diagnostic approach. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1148–1159. doi: 10.1007/s003300050525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz LH, Gandras EJ, Colangelo SM, Ercolani MC, Panicek DM. Prevalence and importance of small hepatic lesions found at CT in patients with cancer. Radiology. 1999;210:71–74. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.1.r99ja0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamm B, Thoeni RF, Gould RG, Bernardino ME, Lüning M, Saini S, et al. Focal liver lesions: characterization with nonenhanced and dynamic contrast material-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1994;190:417–423. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.2.8284392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Major PP, Cook RJ, Lipton A, Smith MR, Terpos E, Coleman RE. Natural history of malignant bone disease in breast cancer and the use of cumulative mean functions to measure skeletal morbidity. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:272. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costelloe CM, Rohren EM, Madewell JE, Hamaoka T, Theriault RL, Yu TK, et al. Imaging bone metastases in breast cancer: techniques and recommendations for diagnosis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:606–614. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]