Abstract

Background

The biology of hepatic epithelial haemangioendothelioma (HEHE) is variable, lying intermediate to haemangioma and angiosarcoma. Treatments vary owing to the rarity of the disease and frequent misdiagnosis.

Methods

Between 1989 and 2013, patients retrospectively identified with HEHE from a single academic cancer centre were analysed to evaluate clinicopathological factors and initial treatment regimens associated with survival.

Results

Fifty patients with confirmed HEHE had a median follow-up of 51 months (range 1–322). There was no difference in 5-year survival between patients presenting with unilateral compared with bilateral hepatic disease (51.4% versus 80.7%, respectively; P = 0.1), localized compared with metastatic disease (69% versus 78.3%, respectively; P = 0.7) or an initial treatment regimen of Surgery, Chemotherapy/Embolization or Observation alone (83.3% versus 71.3% versus 72.4%, respectively; P = 0.9). However, 5-year survival for patients treated with chemotherapy at any point during their disease course was decreased compared with those who did not receive any chemotherapy (43.6% versus 82.9%, respectively; P = 0.02) and was predictive of a decreased overall survival on univariate analysis [HR 3.1 (CI 0.9–10.7), P = 0.02].

Conclusions

HEHE frequently follows an indolent course, suggesting that immediate treatment may not be the optimal strategy. Initial observation to assess disease behaviour may better stratify treatment options, reserving surgery for those who remain resectable/transplantable. Prospective cooperative trials or registries may confirm this strategy.

Introduction

Hepatic epithelioid haemangioendothelioma (HEHE) is a rare malignant neoplasm of vascular origin. The aetiology and natural history of HEHE is only partially understood because of its low incidence, typically indolent growth pattern and frequent misdiagnosis as other tumours including cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and angiosarcoma.1 HEHE is thought to be a low-grade tumour with a clinical course that lies between benign haemangioma and aggressive angiosarcoma.1–4 The tumour most frequently presents with pain and often there is bilateral liver involvement and/or metastatic disease, typically to the lungs and spine, at the time of diagnosis.1,5 Although HEHE is often diagnosed after evaluation for abdominal pain, it may be discovered incidentally and in rare cases patients have presented with an associated Budd–Chiari syndrome, Kasabach–Merritt syndrome or with haemorrhagic shock from a tumour rupture.6,7

The rarity of HEHE coupled with the common misdiagnosis of the tumour has limited any randomized controlled treatment trials and has resulted in a variety of treatment strategies ranging from observation to chemotherapy to liver transplantation. Treatment with anti-angiogenesis drugs such as thalidomide,8 immunotherapy with interferon α-2B,9 systemic chemotherapy,10 chemoembolization,11 or combined modality therapies have all been utilized with varying results. Some patients who present with diffuse liver involvement have demonstrated tumour regression over time without any treatment.12 Furthermore, the presence of metastatic disease has not consistently precluded surgical extirpation as selected patients with metastatic disease appear to have benefited from surgical resection.5 Studies from Belgium and the United States, for example, have demonstrated that orthotopic liver transplantation can provide durable survival, even for patients with metastatic disease.13–16 Review of the published literature on HEHE does not provide a consensus on the treatment of this rare neoplasm and evidence exists that the survival of patients with this tumour, once reported as a 5-year survival of 25%, may not be as poor as originally reported.17,18

Because of the inconsistent and often changing treatment strategy even among individual patients, we sought to evaluate the specific influence of the initial treatment regimen for patients diagnosed with HEHE. Given the variable tumour biology of HEHE, we hypothesized that a period of observation to assess tumour biology in this generally indolent tumour may improve selection for more appropriate patient-based treatment. In this present study, one of the largest medical–surgical series of patients diagnosed with HEHE to date, we assessed tumour progression and survival based upon all initial treatment modalities that are currently utilized in order to develop a clinical algorithm for treatment of patients diagnosed with HEHE.

Methods

The collection and analysis of data associated with this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. From 1989 to 2013, a total of 50 patients with HEHE were identified from the cancer tumour registry at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX, USA). Medical records were retrospectively reviewed and clinicopathological parameters, treatments rendered and clinical outcomes were evaluated.

The diagnosis of HEHE was guided by imaging characteristics found on ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and secured after a tissue sample was obtained either by percutaneous routes or surgical means, when the percutaneous biopsy was inconclusive or a mass was incidentally found during a laparoscopy/laparotomy. All tumours were examined by immunohistochemistry for the endothelial markers CD31 and CD34.

Treatment decisions for HEHE are often made with the presumption that it has an indolent disease course or based upon the extent of intrahepatic or metastatic disease. This prompted a cohort analysis based on initial treatment modality as well as survival evaluation of groups based on extent of disease. Treatment modalities were based on three groups: those who underwent observation only (Observation Group), patients who underwent surgical resection (Surgical Group), and those who received non-surgical treatment (Chemo/Embol Group) which included: chemotherapy, immunomodulating/biological agents (interferon, anti-angiogenesis, or COX-2 inhibition), chemoembolization, direct tumour injection, or bland embolization. The start of the initial treatment was defined as the date of surgery for the Surgical group, date of chemotherapy/embolization for the Chemo/Embol group and the date of diagnosis for the Observation group as no specific treatment was rendered. Surveillance imaging studies included CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and were performed every 6–12 months, at the discretion of the treating physician, and reviewed for disease progression.

Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc (v12.3) statistical software (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Summary statistics were used to describe the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population and subgroups based on initial treatment (observation, surgical and chemotherapy/embolization). The Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance was utilized to assess differences in continuous variables between the three initial treatment groups. Differences in categorical variables between the three initial treatment groups were assessed using Pearson's chi-square analysis. Time to progression (TTP) was defined as the time from institution of initial treatment to the time of documented progression on imaging or the time of last follow-up/death if disease progression had not been identified. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from initial diagnosis of HEHE to death and was censored at the date of last follow-up if death had not occurred. Univariate Cox's proportional hazards regression was used to model the association between each potential prognostic factor and time to progression (TTP) or OS. Factors shown to be predictive of TTP or OS on univariate analysis were then evaluated using multivariate Cox's proportional hazards regression. The 5-year OS rate and comparison of proportions between treatment groups are reported for survival data. A two-sided significance level of 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) were used for all statistical analyses. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics and presentation

A total of 50 patients were identified with HEHE and histologically confirmed by immunohistochemistry with all staining positive for CD31 and CD34 and comprise the study population. The median follow-up from diagnosis was 51 months (range 1–322). Sixty-six per cent (n = 33) of the cohort was female with a median age at the time of initial diagnosis of 46 years (range 18–92.1). The most common presenting symptom was abdominal pain (n = 28, 56%) followed by an incidental finding on abdominal imaging (n = 8, 16%). Stratifying for the three treatment groups there were no differences in clinicopathological or laboratory values at presentation except for the presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cohort demographics and clinical parameters by initial treatment regimen

| Entire cohort | Surgical | Chemo/Embol | Observation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 50 | n = 7 (14) | n = 18 (36) | n = 25 (50) | p | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 17 (34) | 3 (43) | 6 (33) | 8 (32) | NS (0.9) |

| Female | 33 (66) | 4 (57) | 12 (67) | 17 (68 | |

| Age at Diagnosis, years | |||||

| Median (Range) | 46 (18–92) | 33 (18–46) | 51 (22–72) | 48 (18–92) | NS (0.09) |

| Age at Presentation to MDACC, years | |||||

| Median (Range) | 46 (18–92) | 34 (18–46) | 52 (22–72) | 48 (18–92) | NS (0.09) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||

| Median (Range) | 26 (15–81) | 25 (19–37) | 25 (15–38) | 26 (20–81) | NS (0.6) |

| Presenting symptom, n (%) | |||||

| Abnormal LFTs | 6 (12) | 1 (14) | 2 (11) | 3 (12) | NS (0.8) |

| Abnormal imaging | 8 (16) | 1 (14) | 2 (11) | 5 (20) | |

| Fatigue | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (4) | |

| Pain | 28 (56) | 5 (71) | 10 (56) | 13 (52) | |

| Weight loss | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 4 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 3 (12) | |

| Albumin (g/dl) | |||||

| Median (range) | 3.95 (2.8–5.2) | 4.6 (2.8–5.2) | 3.9 (2.9–5) | 4.05 (3–4.6) | NS (0.24) |

| AST (IU/l) | |||||

| Median (range) | 24 (12–105) | 16 (12–20) | 23 (15–105) | 27 (15–93) | NS (0.08) |

| ALT (IU/l) | |||||

| Median (range) | 32 (10–140) | 28.5 (12–113) | 41 (10–129) | 30 (10–140) | NS (0.35) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/l) | |||||

| Median (range) | 114 (55–877) | 130.5 (70–295) | 121 (79–877) | 93 (55–842) | NS (0.15) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | |||||

| Median (range) | 0.5 (0.2–3.9) | 0.55 (0.3–1.5) | 0.45 (0.2–2) | 0.6 (0.3–3.9) | NS (0.9) |

| Intrahepatic distribution, n (%) | |||||

| Unilateral | 12 (24) | 3 (43) | 2 (11) | 7 (28) | NS (0.2) |

| Bilateral | 38 (76) | 4 (57) | 16 (89) | 18 (72) | |

| Disease pattern, n (%) | |||||

| Nodular | 32 (64) | 4 (57) | 13 (72) | 15 (60) | NS (0.7) |

| Diffuse | 18 (36) | 3 (43) | 5 (28) | 10 (40) | |

| Total tumour nodules, no. | |||||

| Median (range) | 8 (1–59) | 8 (1–23) | 11 (8–28) | 7 (1–59) | NS (0.2) |

| Largest tumour nodule (cm) | |||||

| Median (range) | 4 (1.5–12.9) | 3.6 (3–11) | 4 (2–9.8) | 4 (1.5–12.9) | NS (0.9) |

| Metastasis, n (%) | |||||

| No | 26 (52) | 7 (100) | 7 (39) | 12 (48) | 0.02 |

| Yes | 24 (48) | 0 (0) | 11 (61) | 13 (52) | |

| Time from Dx to 1st Tx, non-obs, days | |||||

| Median (range) | 39 (0–79) | 39 (24–46) | 36 (0–79) | N/A | NS (0.7) |

| Time between 1st and 2nd Tx, days | |||||

| Median (range) | 328 (0–3630) | 585 (585) | 173 (0–2705) | 379 (71–3630) | NS (0.43) |

All laboratory values indicate measurements at the time of diagnosis. BMI, Body Mass Index; LFTs, Liver Function Tests; CT, Computed Tomography; AST, Aspartate Aminotransferase; ALT, Alanine Aminotransferase; LDH, Lactate Dehydrogenase; Dx, Diagnosis; Tx, Treatment; Non-Obs, Non-Observational Cohort.

Twenty-four patients (48%) had metastatic disease at presentation with 0 Surgical patients (0%), 11 Chemo/Embol patients (61%), and 13 (52%) Observation patients possessing metastasis at the time of diagnosis (P = 0.02; Table 1). Four patients (8%) had multiple sites of metastatic disease at the time of presentation. The majority of patients presented with bilateral hepatic disease at the time of presentation (n = 38, 76%) and 53% (n = 20) of these patients had evidence of metastatic disease, compared with only 33% (n = 4) of patients with unilateral hepatic disease presenting with evidence of metastasis. The most common site of metastasis was lung (n = 21, 88%), followed by bone (n = 5, 21%).

Patients were more likely to be referred to medical oncology (n = 37, 74%) than to surgery (n = 13, 26%; P < 0.01) for their initial treatment. Those who were initially referred to the medical oncology service were more likely to undergo initial Chemo/Embol treatment (n = 16, 43%) or initial Observation (n = 21, 57%) than to be subsequently referred to surgery for their initial treatment (n = 0, 0%; P < 0.01). Conversely, there was no difference in initial treatment regimens (P = 0.2) for those patients who were referred to the surgical service for initial treatment recommendations as 7 patients (54%) underwent Surgery, 2 patients (15%) were referred for Chemo/Embol treatment and 4 patients (31%) underwent Observation.

Initial treatment cohorts

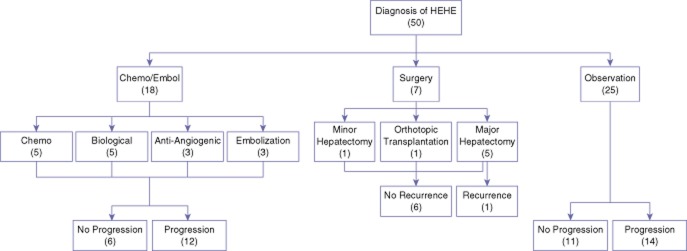

Figure 1 demonstrates the entire cohort (n = 50) of patients diagnosed with HEHE based upon the initial treatment regimen. After the diagnosis of HEHE, 7 patients (14%) comprised the Surgical Group, 18 patients (36%) the Chemo/Embol group and 25 patients (50%) were in the Observation group. There was no statistical difference in the median time from initial diagnosis to initial treatment between patients in the Surgical group [39 days (range 24–46 days)] compared with the Chemo/Embol group [36 days (range 0–79 days), P = 0.7].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the initial treatment regimen for the cohort of patients diagnosed with hepatic epithelial haemangioendothelioma (HEHE)

Cohort treatment history

Initial surgical cohort

Seven patients (14%) were evaluated and had surgery as their initial treatment for HEHE (Fig. 1). There was no peri-operative (< 30 day) mortality in the entire cohort. Only one patient (10%) recurred during follow-up and the patient subsequently underwent orthotopic liver transplantation but developed additional recurrent disease in the transplanted liver as well as lung metastases. Systemic interferon therapy was given to this patient for 3 months but discontinued secondary to rejection of the transplanted liver and the patient subsequently died. This is the only patient in the initial Surgery cohort who was later treated with a Chemo/Embol modality (in this case an immunomodulating agent). No patient in the initial Surgery cohort was ever given systemic chemotherapy.

At last follow-up, for the cohort of 7 patients treated initially with surgery, 3 patients (43%) were alive without evidence of disease, 2 (29%) were alive with disease, 1 patient (14%) died of disease and 1 patient (14%) was without disease but died of non-related causes (Table 2). Of the 11 patients who were treated with surgery at any time during their disease course, 1 patient (9%) developed lung metastases, and 2 patients (18%) developed a local recurrence which were subsequently treated with radiofrequency ablation and orthotopic transplantation, respectively.

Table 2.

Status of patients at last follow-up based on the initial treatment regimen

| Disease Status | Entire cohort | Surgical | Chemo/Embol | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | n = 50 | n = 7 (14) | n = 18 (36) | n = 25 (50) |

| NED | 6 (12) | 3 (43) | 2 (11) | 1 (4) |

| AWD | 30 (60) | 2 (29) | 9 (50) | 19 (76) |

| DWD | 13 (26) | 1 (14) | 7 (39) | 5 (20) |

| DOC | 1 (2) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

NED, No Evidence of Disease; AWD, Alive With Disease; DWD, Died With Disease; DOC, Died Other Causes.

Initial chemo/embol cohort

Eighteen (36%) patients were initially treated with non-surgical interventions after their diagnosis of HEHE (Fig. 1). Seven patients were given various regimens of chemotherapy and one patient received chemotherapy (paclitaxel) in combination with bevacizumab. Five were given biological agents including interferon (n = 4) or tumour necrosis factor (n = 1), 2 patients were treated with anti-angiogenics including celecoxib (n = 1), thalidomide (n = 1), and the aforementioned patient who received bevacizumab in combination with paclitaxel. Three patients were treated with embolization of the tumour. Eleven patients (55%) had a treatment change or addition from their initial chemotherapy/embolization management, which was as a result of tumour progression or toxicity of the original therapy. Three patients were placed on chemotherapy or biologics, two patients had tumor embolization performed, two patients underwent orthotopic liver transplantation, one patient was switched to interferon while another had a dose increase, one patient was changed to celecoxib and one patient had external beam radiation to dermal metastases. No patient treated initially or secondarily with chemotherapy/embolization was rendered free of disease.

Of the 18 patients in the initial Chemo/Embol group, only 2 (11%) were free of disease at last follow-up both having undergone salvage orthotopic liver transplantation after progression on initial medical therapies. Of the remaining patients who were initially treated in the Chemo/Embol group, 9 patients (50%) were alive with disease and 7 patients (39%) died of their disease at last follow-up (Table 2).

Initial observation cohort

Upon initial diagnosis of HEHE, 25 (50%) patients underwent observation only (Fig. 1). Fourteen of these patients (56%) had progression of disease during this observation period. One patient had rapid progression and died, the remaining 13 patients were switched to either Surgical or Chemo/Embol treatment. This included celecoxib (n = 6, 24%), interventional techniques including radiofrequency ablation, embolization, or intratumoural injection (n = 3, 12%), chemotherapy (n = 1, 4%), interferon (n = 1, 4%) and surgical resection (n = 2, 8%). The median period of observation prior to subsequent chemotherapy/embolization or surgical treatment for tumour progression was 322 days (range 114–3630).

For those individuals who were initially observed, only one patient was without evidence of disease at last follow-up; a patient who later underwent a left hepatectomy for disease progression while on observation. Otherwise, the majority of patients who were initially observed were alive with stable disease (Table 2).

Survival

The 5-year survival rate for the entire cohort from the time of diagnosis was 73% with a median follow-up of 51 months (range 1–322). There were no clinicopathological predictors of TTP or OS on univariate analysis except for age > 45 years and the number of tumour nodules > 8 being a predictor of OS on univariate analysis only (HR 3, CI 1.1–7.9, P = 0.05; HR 4.1, CI 1.2–13.9, P = 0.02, respectively). There was no statistically significant difference in the 5-year survival rates based on the initial treatment regimen comparing the Surgery (83%), Chemo/Embol (71%), and Observation (72%) cohorts (Surgery vs. Chemo/Embol, P = 0.9; Chemo/Embol versus Observation, P = 0.8; Surgery vs. Observation, P = 0.9; Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of the 5-year survival rates of patients diagnosed with HEHE based on initial treatment and clinical factors

| Cohort comparison | 5-year survival (%) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Entire cohort | 73 | N/A |

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||

| < 45 | 91 | 0.03 |

| > 45 | 60 | |

| Initial treatment | ||

| Surgical | 83 | NS (0.9)a |

| Chemo/Embol | 71 | NS (0.8)b |

| Observation | 72 | NS (0.9)c |

| Hepatic disease | ||

| Unilobar | 51 | NS (0.1) |

| Bilobar | 81 | |

| Disease pattern | ||

| Nodular | 69 | NS (0.6) |

| Diffuse | 80 | |

| Total tumour nodules | ||

| <8 | 87 | 0.05 |

| >8 | 52 | |

| Largest tumour size (cm) | ||

| <4 | 78 | NS (0.7) |

| >4 | 68 | |

| Extrahepatic disease | ||

| No | 64 | NS (0.7) |

| Yes | 78 | |

| Received chemotherapy | ||

| No | 83 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 44 | |

Summary of 5-year survival rates for patients diagnosed with HEHE based on various cohort analysis. The comparison of 5-year survival rates demonstrated no statistical difference when initial treatment cohorts were compared [Surgical vs. Chemo/Embol (a), Chemo/Embol vs. Observation (b), Surgical vs. Observation (c).

To determine if increased tumour burden or the presence of metastatic disease may play a role in the survival of patients diagnosed with HEHE, survival analysis was performed on these cohorts. Based on the anatomic distribution of disease, there was no statistical difference in the 5-year survival rates between patients who presented with unilateral disease compared with bilateral disease (51% versus 81%, respectively; P = 0.1), nor in patients with localized (hepatic only) disease at the time of diagnosis versus metastatic disease (69% vs. 78%, respectively; P = 0.7). Finally, there was no difference in 5-year survival based upon the disease pattern (nodular versus diffuse) at diagnosis for the entire cohort or when stratified based on the initial treatment regimen. However, patients with greater than eight hepatic tumour nodules had a worse 5-year survival than those who did not when evaluating the entire cohort (52% versus 87%, respectively; P = 0.05; Table 3) but there was no significant difference when stratified based on the initial treatment regimen.

Interestingly, patients who received chemotherapy at any time during their disease course had a worse 5-year survival than those who did not (44% versus 83%, respectively; P = 0.02; Table 3). This was in spite of similar intrahepatic disease burden as there was no statistical difference between patients with unilateral or bilateral hepatic disease at presentation who received chemotherapy and those who did not (P = 0.5). As expected, patients who presented with metastatic disease were more likely to receive chemotherapy than those who did not (P = 0.03) but even patients who presented with metastatic disease and received chemotherapy at any time during their disease course had a worse 5-year survival than patients with metastatic disease who never received chemotherapy (44% versus 100%, respectively; P < 0.01). Based on univariate analysis, there were no factors predictive of TTP. However, treatment with chemotherapy at any time was an independent predictor of decreased OS (HR 3.1 [CI 0.9–10.7], P = 0.02). However, based on multivariate regression, treatment with chemotherapy was not predictive of OS (HR 2.5 [CI 0.92–7], P = 0.07).

Discussion

This study identified and confirmed several important issues regarding risk factors and outcomes for patients with HEHE. The data confirm that HEHE is more frequent in women and patients typically present in the 4th decade of life.19 The overall rate of HEHE metastases was 48% at the time of diagnosis in this cohort of patients, which is consistent with previously published initial staging information. Other previous studies have associated the use of oral contraceptive, hepatitis infection and liver trauma with HEHE.1,3,13,19 Only five patients in our study reported oral contraceptive use and only three patients had known hepatitis B infection. This is likely secondary to limitations in this retrospective study as not all patients were assessed for hepatitis serology nor inquired on oral contraceptive use. The possible aetiology of HEHE, therefore, remains unclear given the rarity of the disease and, often, the misclassification of the tumour.

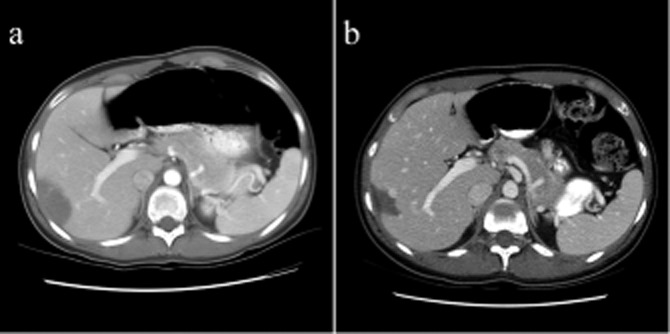

The definitive diagnosis of HEHE can only be made by histopathological review of tissue with the presence of characteristic clusters of epithelioid appearing cells in the sinusoids and smalls veins of the liver. HEHE is often misdiagnosed for cholangiocarcinoma, and fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. However, immunohistochemical staining confirms the correct diagnosis with cells staining positive for the endothelial cell markers FVIII-related antigen, CD31 and CD34.20 Pathology studies have described two distinct forms of HEHE: a nodular type and a diffuse type. The early growth of HEHE is characterized by the nodular lesions that vary from 1 to 3 cm in size. As the smaller lesions grow and coalesce, the lesions become extensive. CT scans of these lesions demonstrate peripherally located low-density nodules with capsular retraction and areas of calcification can be seen within the lesions.21,22 Lesions can also contain fibromyxoid stroma at the periphery and may explain why some lesions spontaneously regress. The stroma may theoretically restrict blood flow to the proliferating tumour cells, causing spontaneous regression even with no treatment (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Example of a patient who was a poor medical candidate for a surgical resection and was initially treated with observation only for a diagnosis of hepatic epithelial haemangioendothelioma (HEHE). Within a 5-year observational period, between 2001 (a) and 2006 (b), there was spontaneous involution and regression of the tumour without any treatment. This patient went on to have stable disease and received no specific treatment for HEHE

Although our analysis is one of the larger series to date for patients with HEHE (Table 4), it is limited by a small and heterogeneous patient population and retrospective nature of the cohort evaluation. In addition, as our institution is not a transplant centre, our cohort lacked significant patients who underwent liver transplantation for initial treatment of HEHE which has been shown to have favourable long-term outcomes.14–16 As such, one surgical cohort was designed to evaluate its role in the initial management of HEHE. The present series is unique in that comparisons were made between all treatments rendered, without focusing on one particular treatment such as surgery, for example. In spite of these limitations, the key finding of our study was the spectrum of the observed natural history, with many patients experiencing an indolent course, and even some patients demonstrating stability of disease or spontaneous regression of tumours without therapy (Fig. 2). Reflecting the tendency towards indolence, the study patients demonstrated no difference in survival based upon the treatment regimen initially utilized at diagnosis. Although prior studies have demonstrated a survival difference based on the disease pattern of nodular compared with diffuse, we did not find such a survival difference in neither our entire cohort nor when stratified based upon the initial treatment regimen.13 Literature has also suggested that tumours less than 10 cm are more predictive of a favourable OS but this was not the case in our cohort of patients and stratifying based on the median tumour size of 4 cm in our cohort, there likewise was not a survival difference.13 However, the number of tumour nodules, in our cohort greater than 8, as well as older age at diagnosis were both associated with a worse prognosis on univariate analysis, which corroborates earlier studies.13,23 In addition, the analysis identified a possible detrimental effect of chemotherapy in treating patients with HEHE. Our data indicate that patients who received any chemotherapy experienced a shorter 5-year survival, compared with patients who never received systemic chemotherapy, in spite of a similar intrahepatic and extrahepatic disease burden between these two groups. This may be related to the fact that HEHE represents part of a spectrum of disease from haemangioma to haemangiosarcoma. In particular, those patients with biologically indolent disease that is more representative of a haemangioma may be better served by observation only, as the morbidity of chemotherapy may be detrimental. Conversely, those patients whose tumour biology reflects a more aggressive disease may benefit from a surgical resection or transplantation and receive little benefit from chemotherapeutic regimens, which have not been proven successful with this disease. Although more patients with metastatic disease at presentation were treated with chemotherapy, there was no difference in survival based on the presence or absence of metastatic disease nor for patients with metastatic disease based on treatment modality. This finding suggests that either more aggressive tumour biology or simply lead-time bias impacts the prognosis of patients with metastatic disease but should not necessarily be a contraindication to surgery.14,24 As such, systemic chemotherapy is not mandatory and recent studies have reported long-term survival with transplantation in patients with metastatic disease.13,14,24

Table 4.

Comparison of contemporary literature involving hepatic epithelial haemangioendothelioma

| Author | Year | Study | Type | Treatment | Cohort (n) | 5-year survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mehrabi18 | 2006 | Meta | Combo | 253 | 41 | |

| LT | 55 | |||||

| LR | 75 | |||||

| Chemo/Embol | 30 | |||||

| Obs | 5 | |||||

| Lerut14 | 2007 | Retro | Combo | 59 | 83 | |

| LT | 80 | |||||

| Grotz13 | 2010 | Retro | Combo | 30 | 64 | |

| LT | 73 | |||||

| LR | 86 | |||||

| Chemo/Embol+Obs | 29 | |||||

| Wang23 | 2012 | Retro | Combo | 33 | 73a | |

| LR | 74a | |||||

| Chemo/Embol | 82a | |||||

| Thomas | 2013 | Retro | Combo | 50 | 73 | |

| (Present Series) | Surgical | 83 | ||||

| Chemo/Embol | 71 | |||||

| Observation | 72 | |||||

Study type refers to meta-analysis (Meta) or retrospective study (Retro). All studies were combination (Combo) studies in which patient cohorts underwent various treatments including liver transplantation (LT), liver resection (LR), chemotherapy and/or interventional radiologic treatments (Chemo/Embol), or observation (Obs). All studies represent 5-year survival rates except for the study by Wang et al. which represents 3-year survival (a).

Our experience represents one of the largest cohorts with HEHE in the literature to date and is unique in its evaluation of various initial treatment regimens (Table 4). Institutional experience with this disease is variable because of the rarity of the disease and a lack of treatment consensus in the medical community. This is likewise demonstrated by the heterogeneous treatment in our cohort. Even at our institution, the referral patterns often dictated the eventual treatment initially rendered as patients who were referred to the medical oncology service more often initially underwent either Chemo/Embol treatment or Observation than Surgery. Although our survival analysis did not show a statistical difference between patients who underwent Chemo/Embol, Surgery or Observation, the survival of patients treated with chemotherapy was decreased compared with those individuals who were never treated with chemotherapy in spite of a similar intrahepatic and extrahepatic disease burden. There were no cases of Chemo/Embol patients being rendered free of disease, as opposed to the surgically treated patients, and several patients treated by Observation alone had appreciable long-term survival.

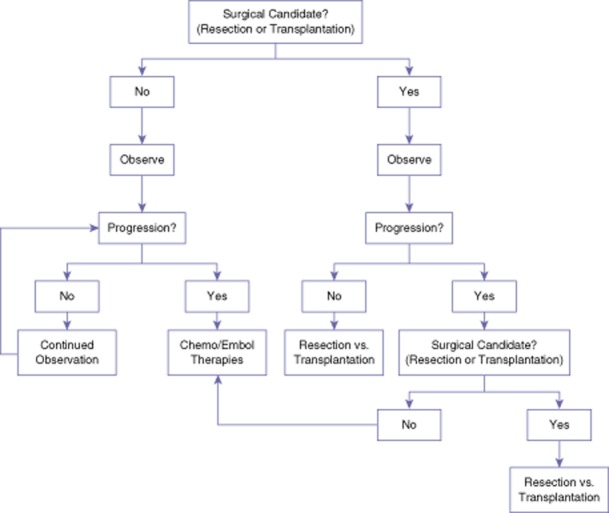

We therefore believe that patients diagnosed with HEHE, as confirmed by biopsy and immunohistochemical positive staining for endothelial markers, should undergo a period of observation to assess disease biology (Fig. 3). In many cases, observation may demonstrate stability or regression of disease without the need for any intervention. Subsequently, patients with clearly resectable disease, progression of disease, or symptomatology even after a period of observation should be offered a surgical resection if the disease remains anatomically resectable. Patients with large volume disease in which a resection is not feasible should be referred for a liver transplantation. Additionally, metastatic disease should not preclude a resection or transplantation as these patients have a similar survival to patients with localized disease and long-term survival after surgical treatment has been reported. Conversely, Chemo/Embol treatment is reserved for patients with large-volume disseminated and progressive disease or for those who are not medically fit to undergo a surgical resection or transplantation. Observation is typically elected for patients who have multifocal but low volume disease and may undergo a future resection with stable disease. In addition, those who are not medically fit for a resection, transplantation or Chem/Embol treatments should undergo observation.

Figure 3.

Treatment algorithm for patients diagnosed with hepatic epithelial haemangioendothelioma (HEHE) initially based on their surgical candidacy. Surgical candidacy depends upon the intrahepatic distribution of tumours such that a patient may undergo a hepatectomy with adequate functional liver reserve for disease clearance versus liver transplantation. Additionally, the medical fitness of a patient to undergo a hepatectomy or transplantation plays a large role in surgical candidacy. Regardless, patients should undergo an initial period of observation for approximately 6–12 months prior to treatment initiation

In summary, the clinical course in patients with hepatic epithelioid haemangioendothelioma is typically indolent. Whereas favourable outcomes from surgery and transplantation are becoming established, outcomes from other therapeutic options remain less clear and patient selection and overall treatment strategies are lacking. Patients with HEHE should be referred to surgery to determine resectability or candidacy for transplantation and presented in a multidisciplinary conference. Present data suggest that observation of clinical behaviour may be a key step in management for patients with HEHE, and as such should be considered in a clinical trial design as future prospective registry or multi-institutional studies, including transplant centres, are developed to clarify prognostic factors and treatment sequencing options for patients with this rare but intriguing disease.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Makhlouf HR, Ishak KG, Goodman ZD. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: a clinicopathologic study of 137 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:562–582. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990201)85:3<562::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haydon E, Haydon G, Bramhall S, Mayer AD, Niel D. Hepatic epithelioid haemangioendothelioma. J R Soc Med. 2005;98:364–365. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.8.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Läuffer JM, Zimmermann A, Krähenbühl L, Triller J, Baer HU. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver. A rare hepatic tumor. Cancer. 1996;78:2318–2327. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961201)78:11<2318::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pokharna RK, Garg PK, Gupta SD, Dutta U, Tandon RK. Primary epithelioid haemangioendothelioma of the liver: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:1029–1031. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.12.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Haim M, Roayaie S, Ye MQ, Thung SN, Emre S, Fishbein TA, et al. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: resection or transplantation, which and when? Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:526–531. doi: 10.1002/lt.500050612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frider B, Bruno A, Selser J, Vanesa R, Pascual P, Bistoletti R. Kasabach-Merrit syndrome and adult hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma an unusual association. J Hepatol. 2005;42:282–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi Y, Inagaki K, Hirota S, Yoshikawa T, Ikawa H. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma with marked liver deformity and secondary Budd-Chiari syndrome: pathological and radiological correlation. Pathol Int. 1999;49:547–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mascarenhas RCV, Sanghvi AN, Friedlander L, Geyer SJ, Beasley HS, Van Thiel DH. Thalidomide inhibits the growth and progression of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Oncology. 2004;67:471–475. doi: 10.1159/000082932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galvão FHF, Bakonyi-Neto A, Machado MAC, Farias AQ, Mello ES, Diz ME, et al. Interferon alpha-2B and liver resection to treat multifocal hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a relevant approach to avoid liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:4354–4358. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Idilman R, Dokmeci A, Beyler AR, Bastemir M, Ormeci N, Aras N, et al. Successful medical treatment of an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of liver. Oncology. 1997;54:171–175. doi: 10.1159/000227683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St Peter SD, Moss AA, Huettl EA, Leslie KO, Mulligan DC. Chemoembolization followed by orthotopic liver transplant for epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:549–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-0012.2003.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otrock ZK, Al-Kutoubi A, Kattar MM, Zaatari G, Soweid A. Spontaneous complete regression of hepatic epithelioid haemangioendothelioma. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:439–441. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70697-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grotz TE, Nagorney D, Donohue J, Que F, Kendrick M, Farnell M, et al. Hepatic epithelioid haemangioendothelioma: is transplantation the only treatment option? HPB. 2010;12:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerut JP, Orlando G, Adam R, Schiavo M, Klempnauer J, Mirza D, et al. The place of liver transplantation in the treatment of hepatic epitheloid hemangioendothelioma: report of the European liver transplant registry. Ann Surg. 2007;246:949–957. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c2a70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerut JP, Orlando G, Sempoux C, Ciccarelli O, Van Beers BE, Danse E, et al. Hepatic haemangioendothelioma in adults: excellent outcome following liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2004;17:202–207. doi: 10.1007/s00147-004-0697-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez JA, Becker NS, O'Mahony CA, Goss JA, Aloia TA. Long-term outcomes following liver transplantation for hepatic hemangioendothelioma: the UNOS experience from 1987 to 2005. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:110–116. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weitz J, Klimstra DS, Cymes K, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica M, La Quaglia MP, et al. Management of primary liver sarcomas. Cancer. 2007;109:1391–1396. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehrabi A, Kashfi A, Fonouni H, Schemmer P, Schmied BM, Hallscheidt P, et al. Primary malignant hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a comprehensive review of the literature with emphasis on the surgical therapy. Cancer. 2006;107:2108–2121. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishak KG, Sesterhenn IA, Goodman ZD, Rabin L, Stromeyer FW. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 32 cases. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:839–852. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Botella A, Díez-Valladares L, Martín-Antona E, Sánchez-Pernaute A, Pérez-Aguirre E, Ortega L, et al. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:167–171. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dighe MK, Parnell S, Yeh MM, Lalani T. Hepatic epitheloid hemangioendothelioma: multiphase CT appearance and correlation with pathology. Crit Rev Comput Tomogr. 2004;45:343–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kehagias DT, Moulopoulos LA, Antoniou A, Psychogios V, Vourtsi A, Vlahos LJ. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: MR imaging findings. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2000;47:1711–1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L-R, Zhou J-M, Zhao Y-M, He H-W, Chai Z-T, Wang M, et al. Clinical experience with primary hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: retrospective study of 33 patients. World J Surg. 2012;36:2677–2683. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1714-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehrabi A, Kashfi A, Schemmer P, Sauer P, Encke J, Fonouni H, et al. Surgical treatment of primary hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Transplantation. 2005;1(Suppl.):S109–S112. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000186904.15029.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]