Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Varenicline, a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) modulator, decreases ethanol consumption in rodents and humans. The proposed mechanism of action for varenicline to reduce ethanol consumption has been through modulation of dopamine (DA) release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) via α4*-containing nAChRs in the ventral tegmental area (VTA). However, presynaptic nAChRs on dopaminergic terminals in the NAc have been shown to directly modulate dopaminergic signalling independently of neuronal activity from the VTA. In this study, we determined whether nAChRs in the NAc play a role in varenicline's effects on ethanol consumption.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Rats were trained to consume ethanol using the intermittent-access two-bottle choice protocol for 10 weeks. Ethanol intake was measured after varenicline or vehicle was microinfused into the NAc (core, shell or core-shell border) or the VTA (anterior or posterior). The effect of varenicline treatment on DA release in the NAc was measured using both in vivo microdialysis and in vitro fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV).

KEY RESULTS

Microinfusion of varenicline into the NAc core and core-shell border, but not into the NAc shell or VTA, reduced ethanol intake following long-term ethanol consumption. During microdialysis, a significant enhancement in accumbal DA release occurred following systemic administration of varenicline and FSCV showed that varenicline also altered the evoked release of DA in the NAc.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Following long-term ethanol consumption, varenicline in the NAc reduces ethanol intake, suggesting that presynaptic nAChRs in the NAc are important for mediating varenicline's effects on ethanol consumption.

Keywords: nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), varenicline, alcohol, dopamine, fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, in vivo microdialysis, microinfusion, ethanol

Introduction

Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs; receptor nomenclature see Alexander et al., 2013a) are implicated as the common molecular target for nicotine and ethanol and, in recent years, have become a promising target for the development of novel medications for alcohol dependence (Chatterjee and Bartlett, 2010). These widely expressed receptors are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels, consisting of various heteromeric or homomeric combinations of α2–α10 and β2–β4 subunits (Zoli et al., 1998; Gotti et al., 2006). Binding of acetylcholine (ACh, endogenous ligand) or nicotine (exogenous ligand) induces a conformational change in the channel, allowing for an influx of cations; in contrast, ethanol is not a direct agonist at nAChRs but can potentiate the response of these receptors to ACh (Cardoso et al., 1999; Zuo et al., 2002).

Through either direct or indirect modulation of nAChRs located in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc), ethanol and nicotine mediate neuronal excitability and dopamine (DA) neurotransmission in the mesolimbic pathway (Zhou et al., 2001; Ericson et al., 2003), and thereby these receptors contribute significantly to the reinforcing effects of these drugs. In the NAc, a limited array of nAChR subtypes [α4β2, α6β2(β3), α4α6β2(β3) and α4α5β2] have been identified on presynaptic dopaminergic terminals that are important mediators of neurotransmitter release in this region (Grady et al., 2002; Champtiaux et al., 2003). In contrast, the VTA expresses a more diverse set of nAChR subtypes that are localized extrasynaptically on somatodendritic sites of dopaminergic neurons and modulate neuronal excitation via membrane depolarization. Nicotinic receptors in this region also significantly contribute to the regulation of excitatory and inhibitory inputs to VTA dopaminergic cells by their presynaptic location on GABAergic and glutamatergic terminal fields (Klink et al., 2001).

Varenicline, a partial agonist at α4β2*, α6β2* and α3β2*-nAChRs (*denotes other possible subunits) and a full agonist at α7 and α3β4* subtypes (Mihalak et al., 2006; Grady et al., 2010), is a useful therapeutic agent for reducing nicotine cravings and withdrawal symptoms (Garrison and Dugan, 2009). The efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation is attributed to a dual action of (1) moderately enhancing DA release in the NAc and (2) the attenuation of nicotine-induced DA release by competitively blocking the nAChR binding site (Rollema et al., 2007; 2010). In addition, varenicline selectively decreases operant self-administration and voluntary ethanol consumption in rodents (Steensland et al., 2007; Hendrickson et al., 2010) and attenuates alcohol drinking in humans (McKee et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2012; Litten et al., 2013). The molecular mechanisms by which varenicline attenuates ethanol consumption have not been completely elucidated. In mice, intra-VTA infusion of varenicline decreases ethanol intake after a short ethanol exposure by actions on the α4 subunit of the nicotinic receptor (Hendrickson et al., 2010). The role of nAChRs localized on presynaptic dopaminergic terminals in the NAc has yet to be investigated for varenicline-induced reductions in ethanol consumption. Given the prominent role of the local cholinergic system in mediating DA release in this region, varenicline may modulate dopaminergic activity and subsequent drinking behaviours through nAChRs in the NAc.

In the experiments presented here, we investigated the role of the NAc in the effects of varenicline on ethanol intake and probed for a mechanism of action using in vivo microdialysis and in vitro fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV). The present findings indicate that nAChRs in the NAc core and core-shell border regions are important in mediating varenicline's effects on dopaminergic transmission and provide further evidence that varenicline may be a useful treatment for alcohol use disorders.

Methods

Drugs and chemicals

Ethanol (95% v v−1; Gold Shield Chemical Co., Hayward, CA, USA) was diluted with dH2O to 20% solutions. Varenicline (6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-6,10-methanol-6H pyrazino[2,3-h][3]benzazepine tartrate) was generously provided by Pfizer Global Research and Development (Groton, CT, USA). For systemic injections, varenicline (1.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) dissolved in saline (0.9%) or vehicle (saline, s.c.) was administered in a volume of 1 mL kg−1, and ethanol (20%, 2.5 g kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle (dH2O, i.p.) was administered during in vivo microdialysis. For microinfusion experiments, varenicline (0.5, 1 and 2 µg) was dissolved in 10% potassium phosphate buffer/90% isotonic saline solution, and thereafter, the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH (1 N). Vehicle infusions consisted of 10% potassium phosphate buffer/90% isotonic saline. The broad-spectrum β2* nAChR-antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE, 100 nM) and the α6* nAChR-selective antagonist α-conotoxin MII [α-CTXMII at 30 nM concentrations has no effect at non-α6/α3 nAChRs (Cartier et al., 1996)] were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK) and dissolved in saline. Drug and molecular target nomenclature accords with the British Journal of Pharmacology's Concise Guide to Pharmacology (Alexander et al., 2013a).

Animals and housing

Male Wistar rats (weighing 150–175 g upon arrival; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were individually housed in ventilated Plexiglas cages with ad libitum access to food and water. In climate-controlled rooms (22 ± 2°C), rats were housed in a reverse 12 h light/dark cycle room (lights off at 10:00 h). All procedures were approved by the Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Ethanol drinking paradigms

The intermittent-access two-bottle choice procedures commenced after acclimatization and 1 week of handling as described by Wise (1973) and Simms et al. (2008). On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, rats were given access to one bottle of ethanol (20% v v−1) and one bottle of water for 24 h; on all other days, two bottles of water were available for 24 h. Control rats had access to two water bottles at all times. The microinfusion, microdialysis and FSCV test sessions were run on Wednesday or Friday; therefore, rats were 1 day without ethanol. This protocol was used to establish long-term ethanol consumption before rats were randomly assigned to microinfusion (n = 51), microdialysis (n = 29) or FSCV (n = 29) experiments.

Surgical procedures

After 8–10 weeks of ethanol exposure in the two-bottle choice paradigm, rats underwent a surgical procedure to place guide cannulae (Plastic One, Roanoke, VA, USA) above the brain region of interest to allow for microinjections or in vivo microdialysis. Animals were deeply anaesthetized, unresponsive to toe pinch, with 2.5% isoflurane (VetEquip, Pleasanton, CA, USA) vaporized in oxygen at a flow rate of 0.6–0.8 L min−1. For the microinfusion studies, a 26 guage bilateral guide cannula assembly (Plastics One, Inc.) was stereotaxically implanted using the following coordinates from bregma with a flat skull: anterior VTA (AP: −5.0, ML: ±1.6, DV: −8.8, 6° angle); posterior VTA (AP: −5.8, ML: ±2.1, DV: −8.8, 10° angle); NAc shell (AP: +2.2, ML: ±0.75, DV: −7.8); NAc core (AP: +1.6, ML: ±1.5, DV: −7.2); NAc core-shell border (AP: +1.6, ML: ±1.0, DV: −7.4). The DV coordinates represent the location of the microinjector tips. For the microdialysis experiment, a unilateral guide cannula (21 guage; Plastics One, Inc.) was implanted with the following coordinates aimed above the NAc core-shell border (AP: +1.6, ML: + or −1.0, DV: −4.0). The core-shell border region, defined by our group, refers to the area where the NAc core and shell borders meet; therefore, this region may include portions of both the medial core and dorsal shell especially when drug diffusion is accounted for. Microinjection tips within the NAc shell region were confined to the medial/ventral shell, but through tissue diffusion, the drug could possibly have reached surrounding areas, for example, olfactory tubercle or islands of callejo. Cannulae were fixed to the head with four stainless steel screws (Plastics One, Inc.) and dental cement (Lang Dental Inc., Wheeling, IL, USA). Rats were allowed to recover for approximately 5–7 days after surgery before returning to the drinking paradigm.

Microinjection procedures

After long-term ethanol exposure (8–10 weeks), rats underwent surgery and were returned to the two-bottle choice paradigm for at least 2 weeks. Before microinfusions commenced (average daily ethanol consumed 6.04 ± 0.27 g kg−1 per 24 h), rats were handled (5 min) on several occasions for habituation to procedures. On test days, 1 µL syringes (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA) mounted on a microdrive pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) infused 0.5 µL of varenicline (0.5, 1 or 2 µg) or vehicle through polyethylene tubing (PE-50, Clay Adams brand; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) into bilateral injectors (33 guage; Plastics One, Inc.) at a rate of 0.125 µL min−1 for 4 min. Injectors remained in place for an additional 2 min to allow for diffusion. Rats were placed back in home cages and drinking sessions commenced 10 min after infusions. By Latin square design, subjects received every dose (balanced order) with 1 week between treatments. The ethanol consumption data were analysed using one-way repeated measures anova, followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc tests.

Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry

FSCV was performed using carbon-fibre microelectrodes (tip length 50 −100 µm) constructed in house with 7 µm carbon fibre and glass electrodes (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA). The electrode potential was scanned with a triangular waveform (from −0.4 to 1.3 V range vs. Ag/AgCl reference electrode) at a scan rate of 400 V·s−1 and a sampling frequency of 10 Hz (Figure 1B). Data acquisition and triangle waveform generation were controlled by TarHeel CV hardware and software (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA).

Figure 1.

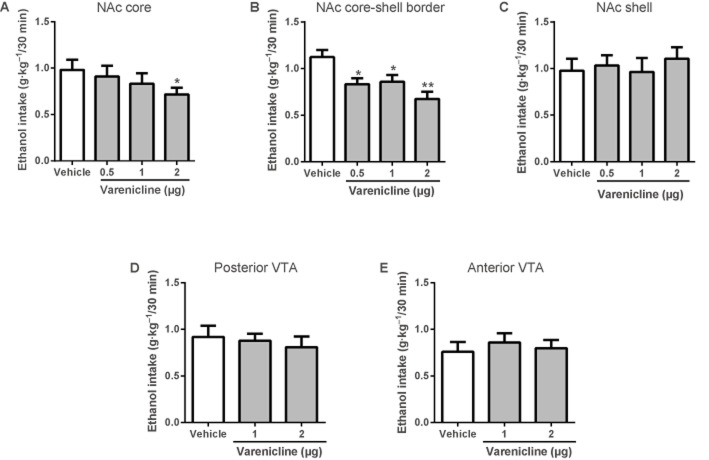

Local varenicline infusion into the NAc (core and core-shell border) reduces voluntary ethanol (20%) consumption in the intermittent-access two-bottle choice paradigm. Values are expressed as mean ethanol intake (g kg−1) ± SEM 30 min after the start of the drinking sessions (n = 8–12 per brain region, one-way repeated measures anova followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with vehicle). Varenicline microinfusion significantly reduced ethanol intake (g kg−1) in the (A) NAc core and (B) NAc core-shell border, but had no effect on ethanol consumption when infused into the (C) NAc shell, (D) posterior VTA or (E) anterior VTA.

Long-term ethanol-consuming rats (>10 weeks; average daily ethanol consumed 5.45 ± 0.26 g kg−1) and age-matched water controls without any previous varenicline treatments were deeply anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (10 mg kg−1, i.p.) and then perfused with an ice-cold sucrose solution consisting of NaCl (125 mM), KCl (1.6 mM), NaH2PO4 (1.1 mM), NaHCO3 (25 mM), CaCl2 (0.1 mM), MgCl2 (1.4 mM), sucrose (50 mM) and glucose (1.2 mM). The brains were sliced with a Leica Microsystems VT1200S Vibratome (300 µm coronal slices; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and slices were kept in a 32°C bicarbonate-buffered ACSF containing CaCl2 (2.4 mM) and glucose (11 mM). After at least 1 h of incubation, brain slices were transferred to a submersion recording chamber and perfused with 30°C oxygenated ACSF.

Recording sites were made in the NAc core-shell border, medial to the anterior commissure that encompass sites within both the NAc core and the shell (approximately within the areas denoted in Figure 2C), with the tungsten matrix electrodes placed (∼100–200 µm) away from the recording electrode (115 µM spacing, FHC). DA release was evoked at 3 min intervals by alternating a single electrical (250 µs duration, 0.6 mA) pulse (1p), which simulated ‘tonic’ dopaminergic activity, with a burst of four pulses (4p, 100 Hz), which simulated dopaminergic neuron firing rates that occur after presentation of a reward or a conditioned reward-related cue. After recordings were made in physiological buffer (ACSF), the non-selective nAChR agonist/partial agonist varenicline (0.1 or 10 µM), the β2* nAChR antagonist DHβE (100 nM) or the α6* nAChR antagonist α-CTXMII (30 nM) were bath-applied for 10 min before data were collected. After background currents were digitally subtracted, peak oxidation (0.6 mV) and reduction (−0.2 mV) currents were converted into [DA]o after post-experimental calibration of the carbon fibre electrode, made by scanning fresh DA standards (1–2 µM) in ACSF. Data are presented as mean peak [DA]o levels (normalized to ACSF control 1p) after single (1p) and multiple (4p) stimulation pulses and as the average ratio of [DA]o released by 1p and 4p to depict the relative simulated phasic-to-tonic response. A two-way repeated measures anova followed by Bonferroni's post hoc tests was used to analyse the average ratio [DA]4p/[DA]1p of the DA signal evoked by 1p and 4p (normalized to control ACSF 1p) during control conditions and after drug application.

Figure 2.

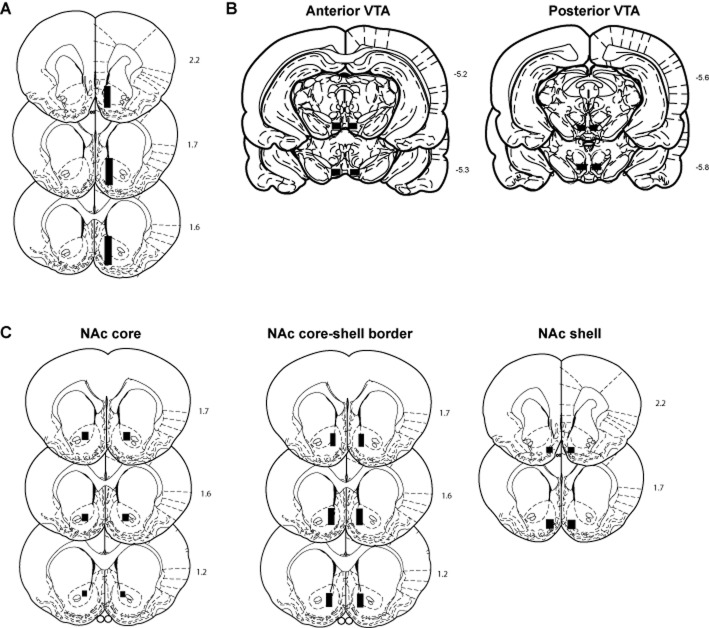

Histological analysis verified cannula placements to be in the correct position. Representative coronal brain sections (Paxinos and Watson, 1997) with respect to bregma showing the accepted placements of (A) active membrane regions of microdialysis probes in the Nac, (B) bilateral infusion cannula tips in the anterior and posterior VTA and (C) bilateral infusion cannula tips in the NAc shell, core and core-shell border.

In vivo microdialysis procedures

Microdialysis probes were constructed according to procedures previously described (Duvauchelle et al., 2000), with a 2.5 mm active membrane extending 4.5 mm beyond the end of the cannula. Before probe implantation, recovery values for each probe were calculated by measuring in vitro samples (peak heights) and comparing them to known DA standards. The mean (±SEM) DA recovery of probes used in these experiments was 15.08 ± 0.49%. Rats were briefly anaesthetized with isoflurane to implant probes at least 12 h prior to the microdialysis test session. Animals remained in a test chamber overnight while artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF: 145 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH) was pumped (Harvard Apparatus) through the probe at a rate of 0.2 µL min−1 with a 1.0 mL glass syringe (Hamilton Company). The pump speed was increased to 1.0 µL min−1 1 h before the test session commenced.

After long-term ethanol exposure (>10 weeks; average daily ethanol consumed 5.14 g kg−1 per 24 h) in the two-bottle choice procedure, microdialysis was performed to measure DA release in the NAc core-shell border. Dialysate samples were collected at 20 min intervals through previously implanted probes; baseline samples were collected for 40 min and then rats were administered varenicline (1.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) or vehicle (saline, s.c.) and immediately placed back into the chambers. After 40 min, rats were given a second injection of ethanol (2.5 g kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle (dH2O, i.p.), and samples were collected for an additional 100 min.

To determine in vivo extracellular concentrations of DA, dialysate samples were analysed by HPLC with electrochemical detection [HPLC-EC; microtitre model 540, Capcell C-18 narrow bore column (1.5 mm I.D. × 50 mm × 3 µm; Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan), model 5200A Coulochem III Detector, model 5041 cell (oxidizing potential: +220 mV) and model 5020 guard cell (potential: +275 mV); ESA, Inc., Chelmsford, MA, USA]. A dual-piston HPLC pump (model 584; ESA, Inc.) circulated mobile phase [sodium dihydrogen phosphate (75 mM), citric acid (4.76 mM), SDS (3 mM), EDTA (0.5 mM), methanol 8% and acetonitrile 11% (v v−1), pH adjusted to 5.6 with NaOH] through the system at a flow rate of 0.2 mL min−1. DA concentrations from samples were quantified by comparing peak heights to external standards. Statistical analysis of dialysate extracellular DA levels (% of basal) during baseline, 40 min after the first injection (1.0 mg kg−1 varenicline or vehicle) and 100 min after the second injection (2.5 g kg−1 ethanol or vehicle) were analysed using two-way (time × treatment) repeated measures anova with Bonferroni's post hoc tests.

Histology

At the end of the experiments, rats were anaesthetized with isoflurane (VetEquip), and brains were removed, stored in 10% formalin for 1 week and 20% sucrose for at least 3 days before being sectioned (30 µm) and stained with cresyl violet. Histological analysis verified cannula placements to be in the correct position within a given brain region.

Results

Microinfusion of varenicline

To examine the effect of varenicline on ethanol intake, varenicline (0.5, 1 or 2 µg) or vehicle was directly infused into the NAc (core, core-shell border or shell) or varenicline (1 or 2 µg) or vehicle into the VTA (anterior and posterior) of rats chronically drinking ethanol in the two-bottle choice model (n = 8–12 animals per brain region). Microinfusion of varenicline (0.5, 1 or 2 µg) into the NAc core-shell border [F(3, 43) = 6.16, P < 0.01] and varenicline (2 µg) into the NAc core [F(3, 47) = 3.74, P < 0.05] significantly attenuated ethanol consumption (g kg−1 per 30 min), whereas infusion into the NAc shell or VTA (anterior and posterior) did not ( Figure 1). Varenicline or vehicle infusions did not affect water intake (30 min, 4 and 24 h) or ethanol intake (4 and 24 h) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Varenicline or vehicle infusions do not affect water intake (30 min, 4 and 24 h) or ethanol intake (4 and 24 h)

| Water intake (mL) | Ethanol intake (mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain region | Treatment | 30 min | 4 h | 24 h | 4 h | 24 h |

| NAc core | Vehicle | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.7 | 22.5 ± 2.8 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.5 |

| Varenicline (0.5 µg) | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 8.2 ± 0.8 | 24.3 ± 2.4 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | |

| Varenicline (1 µg) | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | 23.4 ± 2.7 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | |

| Varenicline (2 µg) | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 24.4 ± 2.4 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | |

| NAc core-shell border | Vehicle | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 15.0 ± 1.7 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.5 |

| Varenicline (0.5 µg) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 15.1 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | |

| Varenicline (1 µg) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 18.1 ± 1.9 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | |

| Varenicline (2 µg) | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 17.9 ± 2.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | |

| NAc shell | Vehicle | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 10.8 ± 1.4 | 28.1 ± 3.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| Varenicline (0.5 µg) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 26.3 ± 2.7 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | |

| Varenicline (1 µg) | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 10.5 ± 3.7 | 24.2 ± 2.5 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | |

| Varenicline (2 µg) | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 9.3 ± 1.0 | 26.4 ± 1.9 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | |

| Posterior VTA | Vehicle | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 1.1 | 14.5 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.4 |

| Varenicline (1 µg) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 14.4 ± 2.9 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.4 | |

| Varenicline (2 µg) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 13.2 ± 2.5 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.5 | |

| Anterior VTA | Vehicle | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 16.3 ± 1.9 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| Varenicline (1 µg) | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 7.2 ± 1.4 | 17.1 ± 2.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | |

| Varenicline (2 µg) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 17.7 ± 2.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | |

The values are expressed as mean water or ethanol intake ± SEM after microinfusion of varenicline or vehicle (one-way repeated measures anova; n.s.).

Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry

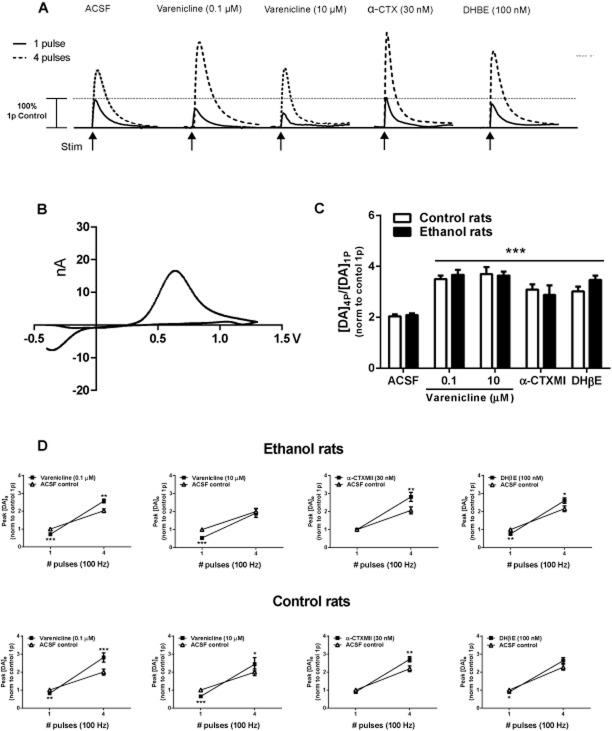

To determine whether varenicline has a direct effect on DA release in the NAc that is distinct from VTA modulation of DA transmission in the NAc, we used FSCV with slices prepared from animals consuming ethanol to measure DA levels evoked by stimuli of 1 pulse (1p) and 4 pulses (4p) to simulate tonic and phasic firing, respectively, as described by Hyland et al. (2002) and Rice and Cragg (2004). We selected the NAc core-shell border NAc as the results from the microinfusion studies showed this region to mediate the effect of varenicline on ethanol consumption. We identified two distinct populations of neurons within NAc core-shell border (k-means cluster analysis, F ratio = 231.9, P < 0.0001), one under control of nAChRs and the other not. This was determined by measuring DA concentrations (µM) evoked by stimuli of 1p or 4p during control conditions (ACSF). If a large ratio [DA]4p/[DA]1p was initially detected, then subsequent treatment with the nicotinic receptor drugs (varenicline, DHβE and α-CTXMII) did not change the magnitude of evoked DA compared with ACSF control conditions (data not shown), indicating minimal control of DA release probability by nAChRs in this subset of neurons, as described by Exley et al. (2008). On the contrary, a small ratio during control conditions has been associated with ACh acting on β2*-nAChRs to promote DA release during a single action potential but limiting release during successive pulses by short-term depression of DA synapses (Landgren et al., 2012). A similar finding has been reported for the NAc core (ventral to the anterior commissure) where a small portion of recording sites (∼20%) lacked strong control by nAChRs (Exley et al., 2008). To understand the role of nAChRs, only sites with a similar ratio [DA]4p/[DA]1p during ACSF control tests were included in the following analyses.

We measured peak DA (µM) levels in the NAc of slices from long-term drinking rats (0.1 and 10 µM), α-CTXMII (30 nM) and DHβE (100 nM). All treatments (n = 6–8 per treatment) significantly [F(3, 51) = 5.29, P < 0.01] enhanced the ratio [DA]4p/[DA]1p compared with ACSF control, and there was no difference in the magnitude of response between treatments or rat groups (Figure 3C). To quantify the direction and magnitude of change, a two-way repeated measures anova of [DA]o (normalized to ACSF control 1p) release revealed that average evoked [DA]o levels after application of drug treatments was significantly [F(9, 153) = 2.12, P < 0.05] different than control conditions and depending upon the treatment either decreased DA release after 1p, increased DA release after 4p or was bidirectional (Figure 3A and D). For ethanol-experienced rats, varenicline (0.1 µM) and DHβE (100 nM) altered DA release probability, reducing evoked [DA]o after 1p and an increasing evoked [DA]o after 4p. Conversely, varenicline (10 µM) reduced evoked [DA]o after 1p and did not alter release stimulated by 4p. In control rats, varenicline (1 and 10 µM) reduced evoked [DA]o after 1p and increased release stimulated by 4p, whereas DHβE (100 nM) reduced [DA]o evoked by 1p but displayed no significant change after 4p. For both ethanol and control rats, the α6β2* nAChR antagonist α-CTXMII (30 nM) treatment evoked [DA]o by 4p was greater compared with ACSF control conditions but not significantly different after a single pulse.

Figure 3.

Evoked DA release in slices from ethanol-drinking and water control rats measured by FSCV in the NAc core-shell border region. Varenicline modulates DA release by desensitizing presynaptic nAChRs in the NAc core-shell border. (A) Representative DA traces evoked (100 Hz, 0.6 mA) by stimuli of one pulse (1 pulse, solid lines) or four pulses (4 pulses, dashed lines) in control ACSF and after varenicline (0.1 and 10 µM), α-CTXMII (30 nM) and DHβE (100 nM). (B) Typical DA voltammogram elicited by one 0.6 mA pulse of 250 µs duration. (C, D) Data represent DA signals in the NAc of slices from ethanol-exposed and water control rats evoked by a single pulse (1p) or a train of 4 pulses (4p) at 100 Hz in the absence (ACSF) or presence of varenicline (0.1 or 10 µM), α-CTXMII (30 nM) and DHβE (100 nM), n = 6–8 per treatment. (C) The average ratio [DA]4p/[DA]1p of the DA signal evoked by 1p and 4p (normalized to control ACSF 1p) in ethanol-exposed rats or water control rats. All treatments significantly enhanced the ratio [DA]4p/[DA]1p compared with ACSF control. There was no difference between ethanol and control animals (three-way repeated measures anova followed by Bonferroni's post hoc tests, ***P < 0.001 compared with ACSF control). (D) Average peak [DA]o levels (normalized to ACSF control 1p) after stimulation pulses (1p and 4p) in the NAc of ethanol-exposed (top panel) or water control (bottom panel) rats (three-way repeated measures anova followed by Bonferonni's post hoc tests, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with ACSF control).

In vivo microdialysis test session

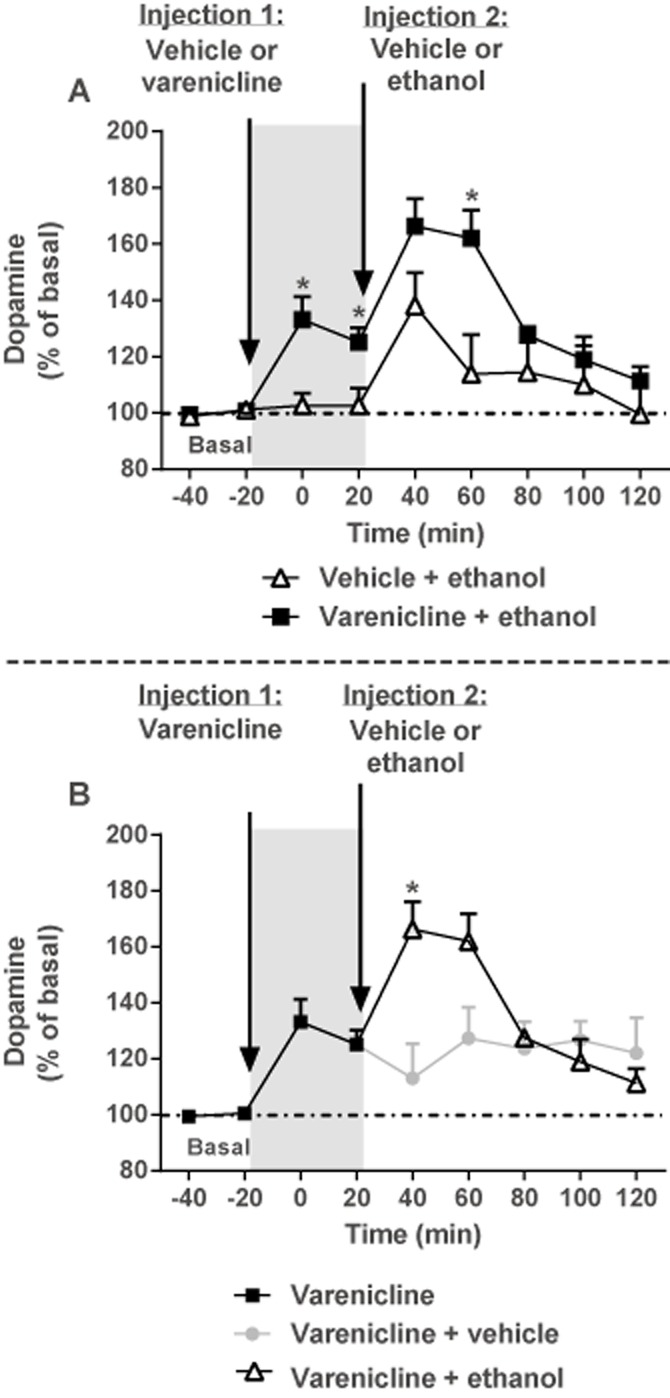

Previously, it has been shown that systemic administration of varenicline in naïve animals leads to an increase in DA release (Ericson et al., 2009); however, the effect of systemic administration of varenicline and ethanol on DA release in the NAc in rats with a history of ethanol consumption has never been examined. During in vivo microdialysis, varenicline (1.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) significantly enhanced extracellular DA release (% of basal) in the NAc core-shell border compared with vehicle during the 40 min period (Figure 4A) after the injection [F(3, 54) = 6.35, P < 0.01, n = 8–12 per treatment]. After the second injection of ethanol (2.5 g kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle [F(8, 60) = 5.36, P < 0.01], rats receiving varenicline + ethanol (n = 6) had significantly greater DA levels compared with groups that were treated with varenicline + vehicle (Figure 4B; first time point, P < 0.05, n = 6) or vehicle + ethanol (Figure 4A; second time point, P < 0.05, n = 6). Similar results were obtained in the animals consuming water only (Supporting Information Fig. S1). The DA concentrations (uncorrected) in basal samples were 1.14 ± 0.19 nM.

Figure 4.

Varenicline enhances NAc DA levels but does not block ethanol-stimulated DA release measured by in vivo microdialysis in rats with a history of voluntary ethanol consumption. Data represent NAc extracellular DA levels (% mean basal ± SEM) before (basal) and after rats were pretreated with varenicline (1.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) or vehicle followed by a second injection 40 min later of either ethanol (2.5 g kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle. (A) Pretreatment with varenicline (1.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) significantly enhanced extracellular DA release in the core-shell border of the NAc compared with vehicle (grey panel, *P < 0.05) during the 40 min period after the injection (two-way repeated measures anova followed by Bonferonni's post hoc tests, n = 8–12 per treatment). After a second injection of ethanol (2.5 g kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle, rats that received varenicline + ethanol had significantly greater DA levels (*P < 0.05) compared with the groups that were treated with vehicle + ethanol (two-way repeated measures anova followed by Bonferonni's post hoc tests, n = 6 per treatment). (B) After a second injection of ethanol (2.5 g kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle, rats that received varenicline + ethanol had significantly greater DA levels (*P < 0.05) compared with the groups that were treated with varenicline + vehicle (two-way repeated measures anova followed by Bonferonni's post hoc tests, n = 6 per treatment).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate for the first time that local infusion of varenicline into the NAc core or core-shell border, but not into the NAc shell or VTA, significantly attenuates ethanol consumption in long-term ethanol-consuming animals. Specifically, varenicline modulates DA release by acting on pre-synaptic nAChRs on dopaminergic terminals in the NAc through a similar mechanism described for nicotine and nAChR antagonists (Zhou et al., 2001; Zhang and Sulzer, 2004).

Our results show that varenicline increases extracellular DA concentrations in the NAc after long-term ethanol consumption and confirms previous findings for naïve rats (Coe et al., 2005; Rollema et al., 2007; Ericson et al., 2009), thus indicating that chronic ethanol consumption does not alter the ability of varenicline to increase DA release in the NA. Varenicline does not block ethanol-stimulated DA release, and ethanol treatment alone exerts a similar relative increase in DA independent of the pretreatment condition (i.e. vehicle or varenicline). This suggests that varenicline and ethanol have independent mechanism of actions for enhancing DA levels in the NAc. In contrast, varenicline competitively blocks nicotine from the binding site and effectively reduces nicotine-induced DA elevation in vivo by 40–55% (Rollema et al., 2007). Our results are in agreement with the studies showing that varenicline (1.5 mg kg−1, s.c.) pretreatment does not reduce DA release following a single acute ethanol (2.5 g kg−1, i.p) injection (Ericson et al., 2009). However, this differs from the experiment showing that concomitant administration of varenicline and ethanol blocked DA enhancement in naïve rats (Ericson et al., 2009). This difference may be due to the fact that we administered varenicline before ethanol rather than at the same time.

In the NAc, ACh is released by a small population of large, aspiny cholinergic interneurons with extensive arborization (Phelps et al., 1985) that subsequently modulates nAChRs expressed on dopaminergic terminals (Zhou et al., 2002). ACh acting on presynaptic β2*-nAChRs promotes DA release during tonic activity but limits release probability during high-frequency, phasic bursts by contributing to short-term depression of DA synapses. In studies utilizing FSCV, blocking these receptors with nAChR antagonists or via agonist-induced desensitization will facilitate DA release during burst firing but will inhibit release during tonic activity (Zhou et al., 2001). This model proposes that a reduction in nAChR function will increase the ratio between tonic and phasic firing patterns, thereby amplifying the signal elicited by reward-associated cues or reinforcers and reducing the effect of tonic dopaminergic activity (Landgren et al., 2012).

As an infusion of varenicline into the NAc core or core-shell border regions reduced voluntary ethanol intake following long-term ethanol consumption in rats, we used FSCV to explore the hypothesis that varenicline locally modulates DA outflow in this region. Varenicline, DHβE and α-CTXMII all significantly increased the contrast between high-and-low frequency evoked DA signals. The α4* and α6* nAChR antagonist DHβE increased DA release after 4p and inhibited release after a 1p in ethanol-consuming rats. In contrast, the effects of the α6* nAChR antagonist α-CTXMII on DA release probability occurred only after 4p. This suggests that the α4* nAChRs mediate the reduction in DA release after 1p and the α6* nAChRs mediate the effects that increase DA release after 4p in long-term ethanol-consuming rats. This supports the findings of other investigators that have shown that there are clear regional differences in the control of dopaminergic transmission between the NAc core and the dorsal striatum (Exley et al., 2008; 2012), and findings from our experiments point to a unique, subunit-specific control of DA release by nAChRs in the NAc core-shell border region. The lowest concentration of varenicline (0.1 µM) increased DA release after 4p and decreased DA release after 1p, suggesting that both α4* and α6* nAChR subunits mediate this effect. In contrast, higher doses of varenicline (10 µM) lead to a decrease in DA release after 1p and did not change DA release after 4p, suggesting that the α4* nAChR subunit plays a major role in this effect after long-term consumption of ethanol. During intermittent access to ethanol, there are days when the animals do not have access to ethanol and this may have significant implications for the neurochemical response to varenicline and may explain why there are differences between drug treatment responses in the ethanol-consuming and control animals. Despite the characteristic directional changes, all treatments resulted in a similar [DA]4p/[DA]1p ratio, which may relay similar information regarding the frequency of firing rates of dopaminergic neurons; however, these directional variations may also be interpreted differentially post-synaptically.

The infusion of varenicline into the NAc core or core-shell border region reduced ethanol consumption, whereas infusions into the medial NAc shell had no effect. Although numerous anatomical and functional differences exist between the NAc subregions (Bassareo and Di Chiara, 1999), the heterogeneous nAChR distribution and cholinergic innervation offer a probable explanation for the inconsistencies in the results between regional injection sites in our experiment. Most notably, immunohistochemical evidence shows a prominent band of cholinergic fibres along the border between the NAc core and shell (Zaborszky et al., 1985; Meredith et al., 1989). The core-shell border may be a distinct site for the dopaminergic response to ethanol, indicated by a report showing only this area (not the NAc core or shell) had a significant increase in DA outflow during operant ethanol self-administration (Howard et al., 2009). A study utilizing FSCV (Zhang et al., 2009) demonstrated substantial frequency-dependent differences during control conditions between subregions, with the NAc shell exhibiting a much larger evoked tonic-to-phasic ratio compared with the NAc core. Additionally, DHβE inhibition of nAChRs was less effective in the NAc shell compared with the dorsolateral striatum and, in fact, the ratio ([DA]5p/[DA]1p at 20 Hz) and frequency-dependent facilitation of DA release in the NAc shell was similar to mutant mice lacking the nAChR β2 subunit. Taken together, these findings suggest only a modest role of nAChRs in the NAc shell on DA release probability and offer a plausible explanation for the lack of response to microinfusion of varenicline into the NAc shell.

Treatment with nAChR antagonists, such as mecamylamine (non-selective nAChR antagonist), also decrease ethanol consumption in rats when administered systemically (Blomqvist et al., 1996; Le et al., 2000) or directly into the anterior VTA by blocking ethanol-induced DA release in the NAc (Blomqvist et al., 1997; Ericson et al., 1998). Furthermore, mecamylamine infused into the NAc does not block ethanol-induced DA release (Blomqvist et al., 1997; Söderpalm et al., 2000) but does reduce ethanol self-administration (Nadal et al., 1998), presumably through desensitization of pre-synaptic nAChRs in the NAc. This shows that it is possible to reduce ethanol self-administration in rats by blocking ethanol-induced DA release via nAChRs in the VTA and by increasing accumbal DA release. It has been shown that intra-VTA varenicline infusions reduce ethanol consumption in mice after short-term ethanol exposure (Hendrickson et al., 2010), an unexpected finding from our study was that varenicline administered directly into the anterior or posterior VTA had no effect on ethanol consumption in long-term ethanol-consuming rats. The most likely explanation is the significant methodological differences between the studies such as the species, varenicline doses and the duration of ethanol exposure prior to varenicline testing (days vs. months). Recent studies utilizing optogenetic and electrophysiological techniques have demonstrated that activation of cholinergic interneurons in the NAc is sufficient to evoke DA release by actions on pre-synaptic nAChRs and does not require action potentials generated by DA soma in the VTA. Thus, activity of cholinergic interneurons and nAChRs in the NAc may also be important for conveying DA signals than previously thought and may profoundly affect the outcome of ascending DA neuron firing activity (Cachope et al., 2012; Threlfell et al., 2012).

Intra-NAc varenicline infusions significantly attenuated ethanol consumption but not to the full extent of systemic administration, indicating that, in addition to the NAc, there are likely other brain regions and/or nAChR subtypes responsible for varenicline's effects. For example, varenicline is a full agonist at α3β4 nAChRs (Mihalak et al., 2006; Grady et al., 2010), which are densely concentrated in regions that play a significant role in reward processing such as the medial habenula and interpeduncular nucleus (Nishikawa et al., 1986; Grady et al., 2009). The high-affinity α3β4 nAChRs partial agonists, CP-601932 and PF-4575180, reduce ethanol consumption in rodents (Chatterjee et al., 2011), indicating that varenicline's mechanism of action may also be attributed to this receptor subtype. Also, varenicline reduced ethanol consumption in mice lacking the β subunits (Kamens et al., 2010). Based upon these studies, we hypothesize that the effects of varenicline on ethanol consumption result from activation and desensitization of nAChRs in multiple brain circuits.

Taken together, our findings show that varenicline enhances DA release in the NAc following long-term ethanol consumption and nAChRs localized on presynaptic dopaminergic terminals in the NAc core and core-shell border play a prominent role in the effects of varenicline on ethanol consumption, suggesting that nAChRs are an important therapeutic target for alcohol use disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Anna Lee and Dr Robert Messing at EGCRC for excellent technical assistance with the FSCV experiments. This work was supported by funding from the NIH 1R01AA017924-01 (to S. E. B.), State of California for Medical Research on Alcohol and Substance Abuse through the University of California, San Francisco (to S. E. B), Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (to S. E. B.), Australian Research Council (to S. E. B) and NH&MRC (to S. E. B.).

Glossary

- α-CTXMII

α-conotoxin MII

- DHβE

dihydro-β-erythroidine

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Conflict of interest

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interests. Varenicline was generously provided by Pfizer Global Research and Development (Groton, CT, USA).

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.12690

Figure S1 Varenicline enhances NAc DA levels but does not block ethanol-stimulated DA release measured by in vivo microdialysis in both ethanol-exposed and water control rats. Data represent NAc extracellular DA levels (% mean basal ± SEM) before (basal) and after rats were pretreated with varenicline (1.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) or vehicle followed by a second injection 40 min later of either ethanol (2.5 g kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle (two-way repeated measures anova; n.s.). The magnitudes of the responses to varenicline and ethanol treatments were similar between ethanol-exposed (n = 6–12 per treatment) and water control rats (n = 3–6 per treatment).

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, Peters JA, Harmar AJ, CGTP Collaborators The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Ligand-gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013a;170:1582–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassareo V, Di Chiara G. Differential responsiveness of dopamine transmission to food-stimuli in nucleus accumbens shell/core compartments. Neuroscience. 1999;89:637–641. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00583-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Ericson M, Johnson DH, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Voluntary ethanol intake in the rat: effects of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor blockade or subchronic nicotine treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;314:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00583-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Ericson M, Engel JA, Söderpalm B. Accumbal dopamine overflow after ethanol: localization of the antagonizing effect of mecamylamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;334:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachope R, Mateo Y, Mathur BN, Irving J, Wang HL, Morales M, et al. Selective activation of cholinergic interneurons enhances accumbal phasic dopamine release: setting the tone for reward processing. Cell Rep. 2012;2:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso RA, Brozowski SJ, Chavez-Noriega LE, Harpold M, Valenzuela CF, Harris RA. Effects of ethanol on recombinant human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:774–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier GE, Yoshikami D, Gray WR, Luo S, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM. A new alpha-conotoxin which targets alpha3beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7522–7528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, David DJ, Przybylski C, Lena C, et al. Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7820–7829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07820.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Bartlett SE. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as pharmacotherapeutic targets for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:60–76. doi: 10.2174/187152710790966597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Coe JW, Hurst RS, et al. Partial agonists of the alpha3beta4* neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor reduce ethanol consumption and seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:603–615. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, Wirtz MC, Arnold EP, Huang J, et al. Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm050069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvauchelle CL, Ikegami A, Castaneda E. Conditioned increases in behavioral activity and accumbens dopamine levels produced by intravenous cocaine. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:1156–1166. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.6.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Blomqvist O, Engel JA, Söderpalm B. Voluntary ethanol intake in the rat and the associated accumbal dopamine overflow are blocked by ventral tegmental mecamylamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;358:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Molander A, Löf E, Engel JA, Söderpalm B. Ethanol elevates accumbal dopamine levels via indirect activation of ventral tegmental nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;467:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Löf E, Stomberg R, Söderpalm B. The smoking cessation medication varenicline attenuates alcohol and nicotine interactions in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:225–230. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, Clements MA, Hartung H, McIntosh JM, Cragg SJ. Alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate the nicotine control of dopamine neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2158–2166. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, Maskos U, Cragg SJ. Striatal alpha5 nicotinic receptor subunit regulates dopamine transmission in dorsal striatum. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2352–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison GD, Dugan SE. Varenicline: a first-line treatment option for smoking cessation. Clin Ther. 2009;31:463–491. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Zoli M, Clementi F. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Murphy KL, Cao J, Marks MJ, McIntosh JM, Collins AC. Characterization of nicotinic agonist-induced [3H]dopamine release from synaptosomes prepared from four mouse brain regions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:651–660. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Moretti M, Zoli M, Marks MJ, Zanardi A, Pucci L, et al. Rodent habenulo-interpeduncular pathway expresses a large variety of uncommon nAChR subtypes, but only the alpha3beta4* and alpha3beta3beta4* subtypes mediate acetylcholine release. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2272–2282. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5121-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Drenan RM, Breining SR, Yohannes D, Wageman CR, Fedorov NB, et al. Structural differences determine the relative selectivity of nicotinic compounds for native [alpha]4[beta]2*-, [alpha]6[beta]2*-, [alpha]3[beta]4*- and [alpha]7-nicotine acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1054–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, Pang X, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Activation of alpha4* nAChRs is necessary and sufficient for varenicline-induced reduction of alcohol consumption. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10169–10176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard EC, Schier CJ, Wetzel JS, Gonzales RA. The dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens core-shell border differs from that in the core and shell during operant ethanol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1355–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland BI, Reynolds JN, Hay J, Perk CG, Miller R. Firing modes of midbrain dopamine cells in the freely moving rat. Neuroscience. 2002;114:475–492. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Andersen J, Picciotto MR. Modulation of ethanol consumption by genetic and pharmacological manipulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;208:613–626. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink R, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A, Zoli M, Changeux JP. Molecular and physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1452–1463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01452.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgren S, Simms JA, Hyytia P, Engel JA, Bartlett SE, Jerlhag E. Ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1A) antagonism suppresses both operant alcohol self-administration and high alcohol consumption in rats. Addict Biol. 2012;17:86–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Corrigall WA, Harding JW, Juzytsch W, Li TK. Involvement of nicotinic receptors in alcohol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Fertig JB, Falk DE, Johnson B, Dunn KE, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy of varenicline tartrate for alcohol dependence. J Addict Med. 2013;7:277–286. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829623f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Harrison EL, O'Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Tetrault JM, et al. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, Blank B, Groenewegen HJ. The distribution and compartmental organization of the cholinergic neurons in nucleus accumbens of the rat. Neuroscience. 1989;31:327–345. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:801–805. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Teague CH, Kayser AS, Bartlett SE, Fields HL. Varenicline decreases alcohol consumption in heavy-drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;223:299–306. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2717-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal R, Chappell AM, Samson HH. Effects of nicotine and mecamylamine microinjections into the nucleus accumbens on ethanol and sucrose self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1190–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa T, Fage D, Scatton B. Evidence for, and nature of, the tonic inhibitory influence of habenulointerpeduncular pathways upon cerebral dopaminergic transmission in the rat. Brain Res. 1986;373:324–336. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain: in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Atlas & Computer Graphics Files) 3th edn. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps PE, Houser CR, Vaughn JE. Immunocytochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase within the rat neostriatum: a correlated light and electron microscopic study of cholinergic neurons and synapses. J Comp Neurol. 1985;238:286–307. doi: 10.1002/cne.902380305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Cragg SJ. Nicotine amplifies reward-related dopamine signals in striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:583–584. doi: 10.1038/nn1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, Glowa J, Hurst RS, Lebel LA, et al. Pharmacological profile of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:985–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Shrikhande A, Ward K, Tingley F, III, Coe J, O'Neill B, et al. Pre-clinical properties of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonists varenicline, cytisine and dianicline translate to clinical efficacy for nicotine dependence. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:334–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms JA, Steensland P, Medina B, Abernathy KE, Chandler LJ, Wise R, et al. Intermittent access to 20% ethanol induces high ethanol consumption in Long-Evans and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1816–1823. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderpalm B, Ericson M, Olausson P, Blomqvist O, Engel JA. Nicotinic mechanisms involved in the dopamine activating and reinforcing properties of ethanol. Behav Brain Res. 2000;113:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Richards JK, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12518–12523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705368104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfell S, Lalic T, Platt NJ, Jennings KA, Deisseroth K, Cragg SJ. Striatal dopamine release is triggered by synchronized activity in cholinergic interneurons. Neuron. 2012;75:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Voluntary ethanol intake in rats following exposure to ethanol on various schedules. Psychopharmacologia. 1973;29:203–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00414034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaborszky L, Alheid GF, Beinfeld MC, Eiden LE, Heimer L, Palkovits M. Cholecystokinin innervation of the ventral striatum: a morphological and radioimmunological study. Neuroscience. 1985;14:427–453. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Sulzer D. Frequency-dependent modulation of dopamine release by nicotine. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:581–582. doi: 10.1038/nn1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Doyon WM, Clark JJ, Phillips PEM, Dani JA. Controls of tonic and phasic dopamine transmission in the dorsal and ventral striatum. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:396–404. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Liang Y, Dani JA. Endogenous nicotinic cholinergic activity regulates dopamine release in the striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1224–1229. doi: 10.1038/nn769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Wilson CJ, Dani JA. Cholinergic interneuron characteristics and nicotinic properties in the striatum. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:590–605. doi: 10.1002/neu.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Lena C, Picciotto MR, Changeux JP. Identification of four classes of brain nicotinic receptors using beta2 mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4461–4472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04461.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom JM, Yeh JZ, Narahashi T. Alcohol modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors is alpha subunit dependent. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:779–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Varenicline enhances NAc DA levels but does not block ethanol-stimulated DA release measured by in vivo microdialysis in both ethanol-exposed and water control rats. Data represent NAc extracellular DA levels (% mean basal ± SEM) before (basal) and after rats were pretreated with varenicline (1.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) or vehicle followed by a second injection 40 min later of either ethanol (2.5 g kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle (two-way repeated measures anova; n.s.). The magnitudes of the responses to varenicline and ethanol treatments were similar between ethanol-exposed (n = 6–12 per treatment) and water control rats (n = 3–6 per treatment).