Abstract

Striatum (STR) is the major input stage of the basal ganglia (BG). It combines information from cortex, subthalamic nucleus (STN) and external globus pallidus (GPe), and projects to the output stages of the BG, where selection between concurrent motor programs is performed. Parkinson’s disease (PD) reduces the concentration of dopamine (DA, a neurotransmitter) in STR and changes in the level of DA correlate with the onset of PD motor disorders. Though STR plays a pivotal role in BG, its behavior under PD and Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) is still unclear. We develop point-process models of the STR neurons as a function of the activity in GPe, cortex, and DBS. We use single unit recordings from a monkey under STN DBS at different frequencies before and after treatment with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) to develop PD motor symptoms. The models suggest that STR neurons have prominent bursting activity in normal conditions, positive correlation with cortex (3–10 ms delay), and mild negative correlation with GPe (1–5 ms lag). DA depletion evokes 30–60 Hz oscillations, and increases the propensity of each neuron to be inhibited by surrounding neurons. DBS elicits antidromical activation, masks existent dynamics, reinforces dependencies between nuclei, and entrains at the stimulation frequency in both conditions.

I. Introduction

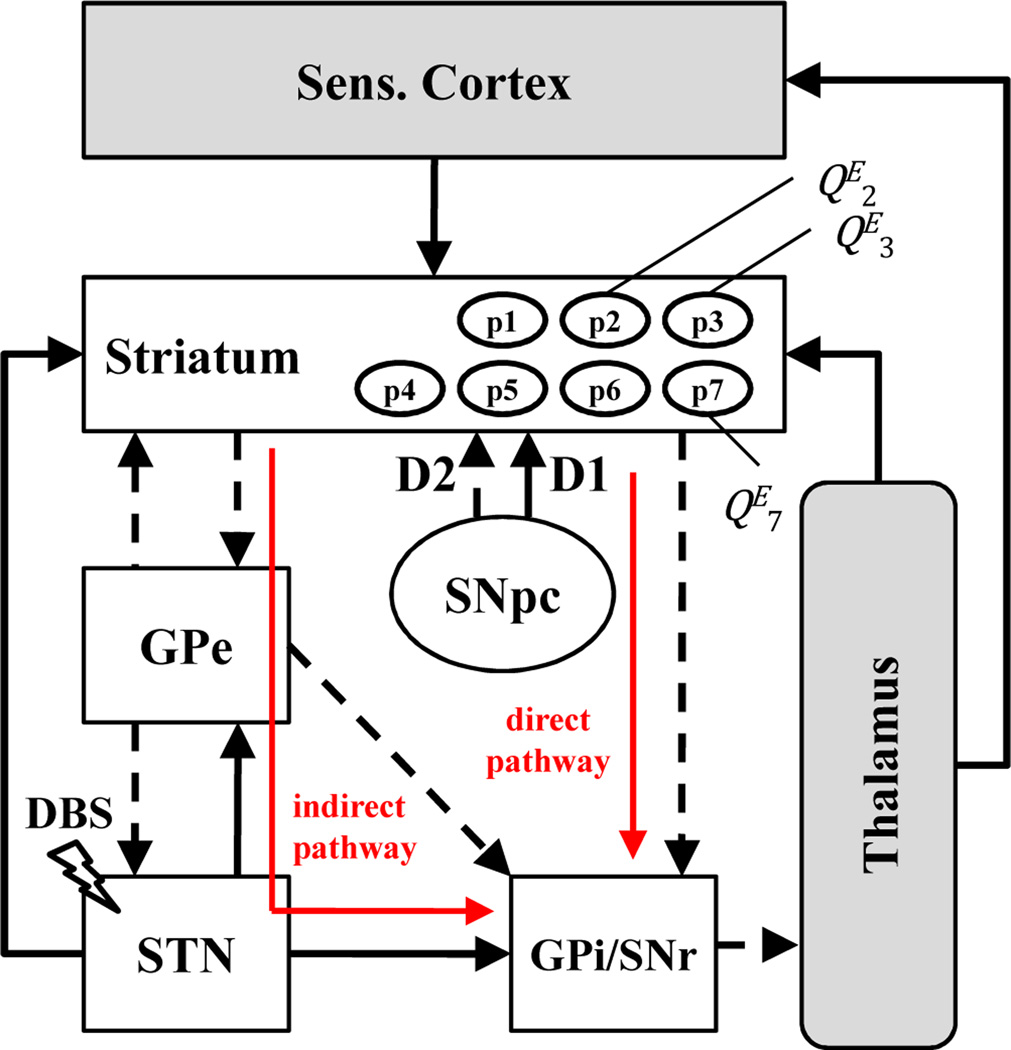

THE processing of motor information may involve highly segregated re-entrant loops, which stem from the motor, pre-motor and somatosensory cortex, project to the sensorimotor areas of the basal ganglia (BG) and thalamus, and returns back to cortex [1][2] (Fig.1). BG filter the input from cortex through several parallel pathways (e.g., direct and indirect pathway) and are hypothesized to contribute to the selection of appropriate motor programs [1]. BG include striatum (STR), subthalamic nucleus (STN), external and internal globus pallidus (GPe and GPi), substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and reticulata (SNr). Several models have been proposed to describe the role of the BG in motor control [2–4], with focus on the polarity of the connections [2], the features of the discharge patterns in the various nuclei [4], or synaptic architecture [3]. All the models, however, agree in assigning a pivotal role to the STR. STR is the main recipient of projections from the motor and somatosensory cortex [5] and is hypothesized to integrate information from different cortical sites before projecting to GPe, GPi and SNr [5–7]. This integration is performed through a complex reticular structure, different types of cells (i.e., spiny neurons, interneurons) [5][6], and combines reentrant inputs from STN, GPe, and thalamus. It involves dopamine (DA), a neurotransmitter released by the SNpc, and is mediated by dopaminergic receptors D1 (excitatory) and D2 (inhibitory) [1][2] (Fig.1). It is hypothesized that STR modulates the BG activity and implements motor-related learning and memory functions [5][7]. DA depletion in Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects the STR by altering the synaptic connectivity [8], decreasing the spiking activity [9], and unbalancing D1- and D2-mediated pathways [1][2]. These effects are hypothesized to derange the activity of the BG and elicit motor disorders [1].

Fig. 1.

BG (white boxes), thalamus and sCTX with some connections. Black arrows are excitatory (bold) and inhibitory (dashed) projections.

The mechanisms of synaptic plasticity in normal and PD primate STR have been studied in vitro [8]. A few studies have analyzed the modulation induced by movements and high frequency (HF) stimulation on the striatal spiking activity in rats [9][10], while no evaluation has been provided for the impact of therapeutic deep brain stimulation (DBS) on the striatal activity in primates.

We investigate the spiking activity of STR neurons at rest (without DBS) and during STN DBS at multiple frequencies, in normal and MPTP conditions, by exploiting single unit recordings from a non human primate. We develop point process models (PPMs) [11] to characterize the spiking propensity of neurons as a function of their spiking histories, the DBS signal, and projections from sensory cortex (sCTX) and GPe. PPMs were recently used to characterize STN neurons from PD patients [12][13] and provided a useful description of several neuronal phenomena [14][15]. As in [12], we use generalized linear methods (GLM) [16] to represent the point process conditional intensity function (CIF) in terms of short and long-term history dependence, thus capturing oscillations, bursting, and the impact of the DBS frequency. Our models suggest that, bursting is the most recurrent phenomenon in normal conditions, while refractoriness and 30–60 Hz oscillations characterize the MPTP state. Positive correlation between STR and sCTX (which suggests possible synchronization) is more frequent than negative correlation (i.e., inhibition in with 1–5 ms lag) between STR and GPe, while, for each neuron, there is higher propensity to be inhibited by surrounding neurons (in the same ensemble) in the first few ms in MPTP than in normal conditions. Each DBS pulse induces antidromic activation and reinforcement phenomena due to the BG-thalamus-cortical connections.

II. Methods

A. Data Collection

Recordings from a non-human primate (macaca mulatta) were used in this study. Details about surgical procedures and data collection are in [17][18]. Briefly, the primate was implanted with a recording chamber and received STN DBS via a reduced scale model of the human DBS lead. Micro-electrode recordings were alternatively obtained from sites in sCTX, STR (post-commissural part of putamen), and GPe during DBS (Fig.1). DBS frequencies were 50, 100, 130 Hz. Stimulation/recording sessions were made both before and after that the primate was treated with MPTP and developed a stable PD state with contralateral rigidity and bradykinesia. During each session, continuous recordings of neuronal activity were made 30 s before and 30 s during DBS. Extracellular signals were band-pass filtered, amplified, digitized (25 kHz), and sorted offline into individual unit activities (QE units per session, with QE ranging from 2 to 7, depending on position and session, Fig.1). For each unit, time stamps of the detected spikes were recorded [17][19]. Neurons included in our study are reported in Table I.

TABLE I.

Experimental Set Up (No. of Neurons Included)

| Site | Frequency | MPTP | Normal |

|---|---|---|---|

| STR | no stimulation | 22 | 75 |

| 50 Hz | 3 | 19 | |

| 100 Hz | not available | 24 | |

| 130 Hz | 9 | 15 | |

| sCTX | no stimulation | 4 | 36 |

| 50 Hz | not available | 18 | |

| 100 Hz | not available | 17 | |

| 130 Hz | 4 | 1 | |

| GPe | no stimulation | not available | 20 |

| 50 Hz | not available | 6 | |

| 100 Hz | not available | 6 | |

| 130 Hz | not available | 8 |

B. Point Process Modeling

We formulated PPMs to relate the spiking propensity of STR neurons to their own spiking history, the history of STR neurons simultaneously recorded (same ensemble), neurons in GPe and sCTX, and DBS. We used the model parameters to analyze the effects of intra- and inter-nuclei dependencies, and DBS [12]. A neural spike train is treated as a series of random binary events that occur continuously in time (point process) [11]. A PPM of a neural spike train is completely characterized on an interval (0, T] by the CIF

| (1) |

where N(t) is the number of spikes in (0, t] for t in (0, T], Ht the history of spikes up to t, Pr the probability [11]. λ(t|Ht) is a generalized history-dependent rate function completely characterizing a spike train [11][15]. For each neuron, we discretized λ(t|Ht) (Δ= 1 ms) [11] and defined the GLM model:

| (2) |

where λO accounts for the neuron own spiking history, λS for DBS (if applied) and λE for dependencies from STR neurons in the same ensemble. λC and λG show dependencies from neurons in sCTX and GPe respectively. k is the k-th bin (ms) and eα accounts for history-independent activity. Specifically,

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

with i = E, C, G. dN(a, b) and is the number of spikes fired by the given neuron and the q-th neuron in region i in [a, b) (in ms) respectively, and dNS(a, b) is the number of DBS pulses delivered in the same interval.

measure the effects of the spiking history in the previous 10 ms, thus detecting refractoriness and bursting [12][18]. For example, if eβ1 ≈ 0, then for any given time bin k, the probability to spike in that bin is close to 0 if the neuron spiked in the previous bin (refractory period). Similarly, account for the history in the previous 10–50 ms and detect oscillations [12]. q = 1, …, Qi show dependencies from other neurons in region i. For example, for a given value of q, if is significantly larger than 1, then for any bin k, the probability that the neuron spikes is modulated up if the q-th neuron in its own ensemble spiked 5 ms prior to k, suggesting phase-locked activity of the two neurons. Similarly, measure the dependency from the DBS input in the previous 8 ms.

For each neuron with an average prestimulation rate ≥10 Hz we estimated the parameter vector i = E, C, G and 95% confidence bounds by maximizing the likelihood of observing the recorded spike trains [11][12]. 80% of the data was used for parameter estimation and 20% was used for validation. The sets of bins (a, b in dN(a, b)) in (3–5) were chosen by minimizing the Akaike’s information criterion [15]. Goodness-of-fit of each PPM was assessed on the validation data with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) plot after time rescaling of the spike trains [15], and only those models whose KS plots are within 95% confidence bounds were used in our analysis [12][15]. Finally, we note that since neurons in sCTX and GPe were not simultaneously recorded with neurons from STR ensembles, for each combination of neurons from sCTX, GPe and STR, 3 models were estimated by randomizing the sequence of sessions from each neuron used for parameter estimation.

III. Results

We compared PPMs estimated for neurons in normal and MPTP conditions, with and without DBS. Results are summarized in Fig. 2–4 and Table II–IV (the discharge frequencies are reported in tables as mean±S.E.M. [19]).

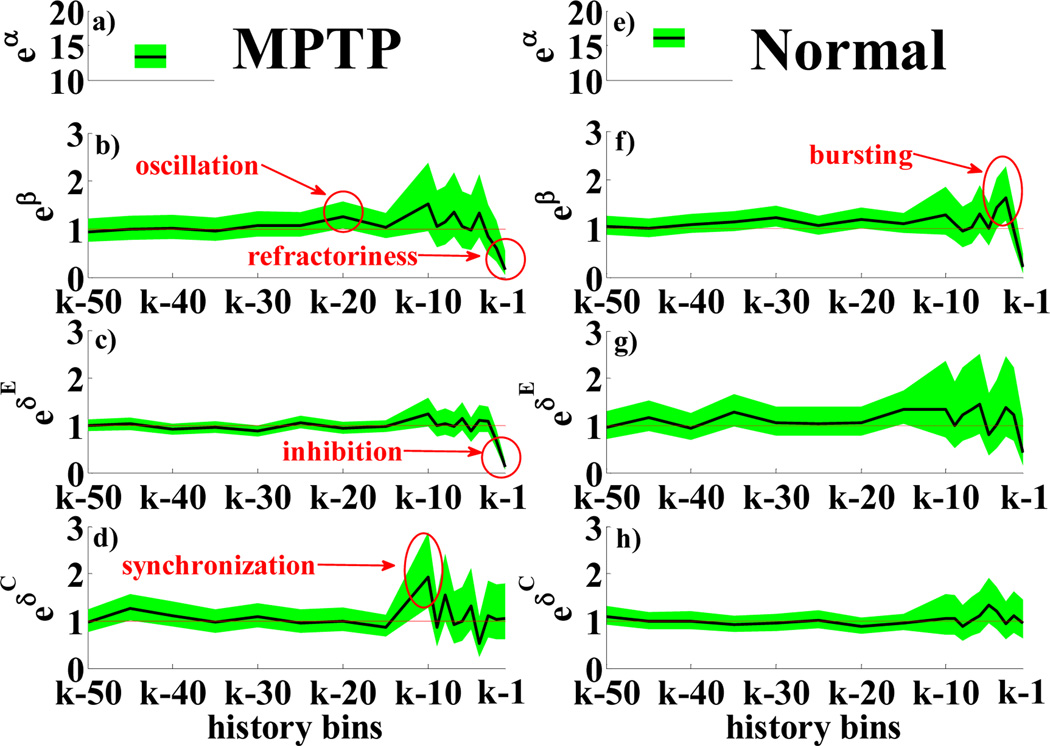

Fig. 2.

PPM for a MPTP (a–d) and a normal (e–h) STR neuron: a), e) eα; b), f) eβr, r = 1, …,18 vs. history bins for a generic time bin k; c), g) , h = 1, …,18 vs. history bins for a specific q and time bin k. c), g) , h = 1, …,18 vs. history bins for a specific q and time bin k. Parameters are black lines, 95% confidence intervals are shaded green areas, e0 = 1 is a red line.

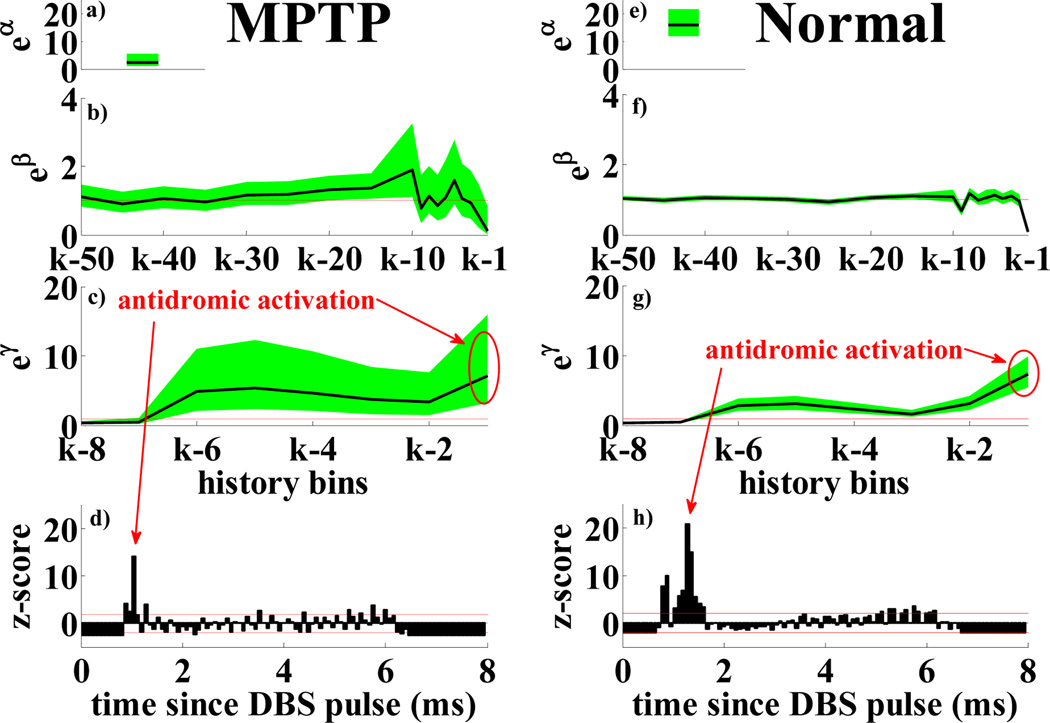

Fig. 4.

PPM for a MPTP (a–d) and a normal (e–h) STR neuron under 130 Hz DBS: a), e) eα; b), f) eβr, r = 1, …,18 vs. history bins for a generic time bin k; c), g) eγν, ν = 1, …,8 vs. history bins for time bin k. d), h) PSTHs. Details as in Fig.3.

TABLE II.

MPTP vs. Normal (No DBS)

| MPTP | Normal | |

|---|---|---|

| Discharge frequency (Hz) | 24.6±0.16 | 26.1±0.15 |

| Neurons with refractoriness | 21/22 | 59/75 |

| Neurons with bursting (3–7 ms) | 3/22 | 25/75 |

| Neurons with oscillations (30–60 Hz) | 5/22 | 4/75 |

| Neurons with oscillations (20–30 Hz) | 1/22 | 9/75 |

| Inhibition from ensemble (1 ms) | 32/79 | 75/234 |

| Dependency from ensemble (3–7 ms) | 17/79 | 73/234 |

| Dependency from ensemble (30–50 ms) | 13/79 | 32/234 |

| Dependency from sCTX (3–10 ms) | 22/79 | 397/2298 |

| Dependency from sCTX (10–30 ms) | 7/79 | 159/2298 |

| Inhibition from GPe (1–5 ms) | - | 49/1009 |

| Dependency from GPe (5–10 ms) | - | 183/1009 |

| Dependency from GPe (30–50 ms) | - | 55/1009 |

TABLE IV.

MPTP vs. Normal (130 Hz DBS)

| MPTP | Normal | |

|---|---|---|

| Discharge frequency (Hz) | 20.3±0.36 | 30.5±0.58 |

| Neurons excited 1–2 ms after pulse | 7/9 | 6/15 |

| Neurons excited 3–6 ms after pulse | 7/9 | 7/15 |

| Neurons excited 7–8 ms after pulse | 2/9 | 0/15 |

A. MPTP vs. Normal with No DBS Input

Table II and Fig.2 compare results in MPTP vs. normal conditions at rest. A few differences between MPTP and normal neurons were noted: MPTP cells show refractoriness (Fig.2b), and some propensity to oscillations in the gamma band (30–60 Hz), while very few cells show bursting or low frequency oscillations. Bursting and oscillations at 20–30 Hz are the most recurrent phenomena in normal conditions, though they involve only 10–30% of neurons. A significant decrease of the average discharge frequency is noted in MPTP vs. normal conditions (unpaired t-test, p-value p < 0.001 [19]), which is accounted by differences in α (Fig.2a,e). Parameters ’s computed for each couple of neurons in the ensemble suggest that MPTP STR neurons exert a stronger inhibition on their own ensemble with a latency of 1–2 ms, and a quite uniform distribution of phase delays in the range 3–50 ms. This may be due to increased feedback inhibition of spiny neurons induced by DA depletion [5]. DA depletion also reduces synaptic plasticity, which may result in less modulation of cortical input [5][8]. This may account for the recurrent coupling between sCTX and STR suggested by ’s with 3–10 ms delay (Fig.2d).

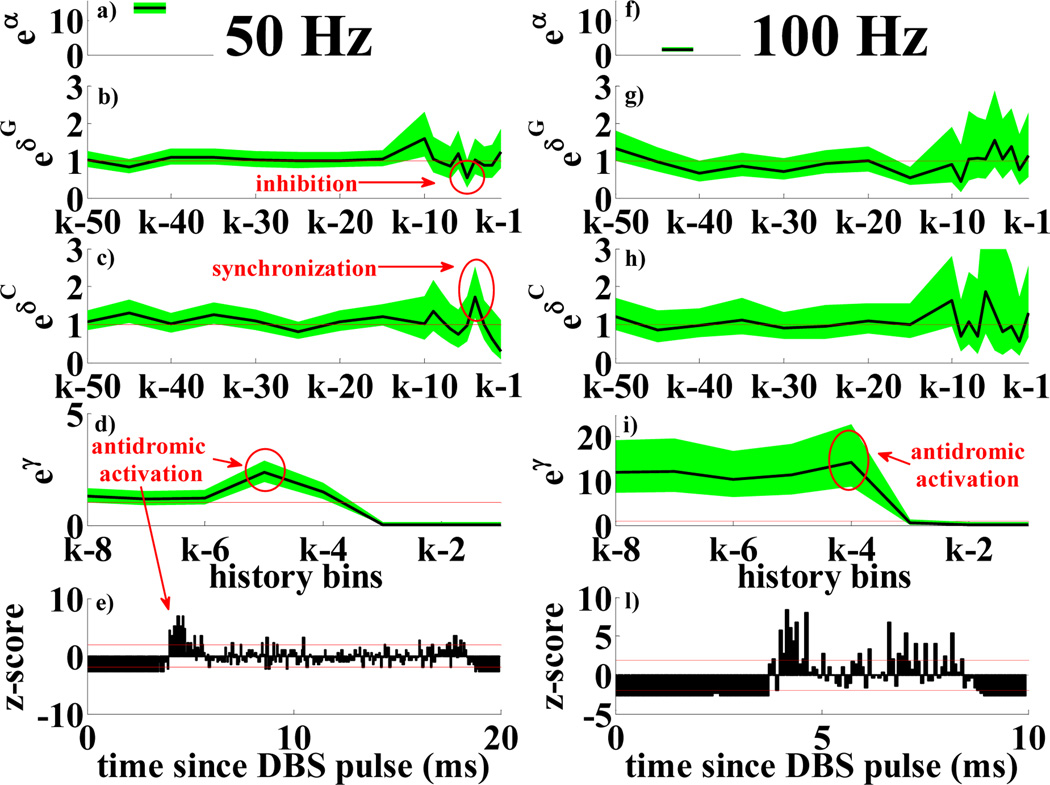

B. Effects of DBS Frequency on Normal Neurons

Table III and Fig.3 compare the effects of DBS at various frequencies in normal conditions. PPMs suggest that DBS increases the probability of spiking 3–5 ms and 7–8 ms after the stimulus, with a recovery period in between (5–7 ms after pulse). This is confirmed by normalized peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs, bin size 0.08 ms [19]) of Fig.3e,l. The high temporal consistency of the neuronal response to the pulses suggests early antidromic activation (masked by the stimulus artifact) [19], followed by spikes at 3–5 ms and 7–8 ms after the pulse. PPMs also suggest a few differences in the neuronal behavior: 100 Hz DBS elicits a phase-locked spiking activity in the neurons (eα strongly drops as soon as DBS is applied, eγν > 10 ν = 4, …,8, Fig.3i), which overrides the dependency from the previous spiking history, while 50 Hz DBS has milder impact (higher value of α, no significant difference from spike trains at rest, and lower γν ’s, Fig.3d). The last column in Table II and III shows that DBS increases the probability of temporal dependency between STR, sCTX and GPe (e.g., 20–23% of ’s show correlation between STR and sCTX with 3–10 ms lag during DBS vs. only 17% at rest), though there is no significant difference vs. rest conditions or between 50 and 100 Hz stimulation.

TABLE III.

50 Hz vs. 100 Hz (Normal)

| 50 Hz | 100 Hz | |

|---|---|---|

| Discharge frequency (Hz) | 25.5±0.49 | 20.8±0.27 |

| Neurons excited 1–2 ms after pulse | 2/19 | 9/24 |

| Neurons excited 3–5 ms after pulse | 11/19 | 24/24 |

| Neurons excited 7–8 ms after pulse | 4/19 | 24/24 |

| Dependency from sCTX (3–10 ms) | 221/1053 | 293/1253 |

| Dependency from sCTX (10–30 ms) | 97/1053 | 118/1253 |

| Inhibition from GPe (1–5 ms) | 25/353 | 17/437 |

| Dependency from GPe (5–10 ms) | 66/353 | 88/437 |

| Dependency from GPe (30–50 ms) | 22/353 | 47/437 |

Fig. 3.

PPM for normal neurons with 50 (a–e) and 100 Hz (f–l) DBS: a), f) eα; b), g) , h = 1, …,18 vs. history bins for a given q and a generic time bin k; c), h) , h = 1, …,18 vs. history bins for a given q and time bin k; d), i) eγν, ν = 1, …,8 vs. history bins and time bin k. e), l) PSTHs (normalization to z-score based on the prestimulation activity [19]). Histograms <−1.96 or >1.96 (red lines) mean significant inhibition or excitation respectively. Legend for a–d), f–i) as in Fig.2.

C. MPTP vs. Normal Conditions under 130 Hz DBS

Table IV and Fig.4 compare results in MPTP vs. normal conditions under 130 Hz DBS. HF DBS resulted in strong antidromic activation (<2ms since DBS pulse), mild spiking 4–5 ms after the pulse and no late spike (7–8 ms), which may be overridden by the DBS pulse [17][19]. Differently from lower frequency stimulation, HF DBS masks the effects of the other temporal dependencies both in normal and MPTP neurons, as shown by βr’s in Fig.4: 95% confidence bounds of parameters in (3),(5) are close to or include 1, while eγν ≫ 1 ∀ν, with modulation down for ν = 3,4 (post-stimulus refractory) and later recovery for ν = 5,6. The prominence of the antidromic activation is more recurrent in MPTP vs. normal conditions, suggesting a wider entrainment of neurons at the stimulation frequency. DBS decreases the average discharge frequency in both conditions, with significance (p < 0.001) only in the MPTP case.

IV. Conclusion

An extremely rare experimental set up and a point process modeling framework are used to investigate the dynamical behavior of STR neurons in normal and MPTP conditions, and measure the impact of STN DBS and temporal dependencies from striato-, cortico- and pallido-striatal projections. Our models indicate that STR neurons have no dominant spiking patterns and mild dependencies from other nuclei in normal conditions, while a higher impact of sCTX, GPe and ensemble arise in MPTP. DBS antidromically elicits spikes at the frequency of stimulation and emphasizes the impact of cortico- and pallido-striatal projections, with mild differences between MPTP and normal conditions.

Contributor Information

S. Santaniello, Institute of Computational Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218 USA.

J. T. Gale, Department of Neurosciences, Cleveland Clinic, 44195 Cleveland, OH, USA(galej@ccf.org)

E. B. Montgomery, Jr, Department of Neurology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294 USA (emontgom@uab.edu).

S. V. Sarma, Institute of Computational Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218 USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gale JT, Amirnovin R, Williams ZM, Flaherty AW, Eskandar EN. From symphony to cacophony: Pathophysiology of the human basal ganglia in Parkinson disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2008 Mar;32:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeLong MR, Wichmann T. Circuits and circuit disorders of the basal ganglia. Arch. Neurol. 2007 Jan;64:20–24. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mink JW. The basal ganglia: focused selection and inhibition of competing motor programs. Prog. Neurobiol. 1996 Nov;50:381–425. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown P. Abnormal oscillatory synchronization in the motor system leads to impaired movement. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007 Dec;17:656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakano K, Kayahara T, Tsutsumi T, Ushiro H. Neural circuits and functional organization of the striatum. J. Neurol. 2000 Sep;247(suppl. 5):V1–V15. doi: 10.1007/pl00007778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreitzer AC. Physiology and pharmacology of striatal neurons. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009 Jun;32:127–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiba A, Oshio K, Inase M. Striatal neurons encoded temporal information in duration discrimination task. Exp. Brain Res. 2008 Apr;186:671–676. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villalba RM, Lee H, Smith Y. Dopaminergic denervation and spine loss in the striatum of MPTP-treated monkeys. Exp. Neurol. 2009 Feb;215:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang JY, Shi LH, Luo F, Woodward DJ. Neural responses in multiple basal ganglia regions following unilateral dopamine depletion in behaving rats performing a treadmill locomotion task. Exp. Brain Res. 2006 Jun;172:193–207. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi LH, Luo F, Woodward DJ, Chang JY. Basal ganglia neural responses during behaviorally effective deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in rats performing a treadmill locomotion test. Synapse. 2006 Jun;59:445–457. doi: 10.1002/syn.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder DL, Miller MI. Random Point Processes in Time and Space. New York, NY: Springer; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarma SV, Eden UT, Cheng ML, Williams ZM, Eskandar E, Brown EN, Hu R. Using point process models to compare neural spiking activity in the subthalamic nucleus of Parkinson’s patients and a normal primate. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010 Jun;56:1297–1305. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2039213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eden UT, Amirnovin R, Brown EN, Eskandar EN. Proc. Joint Statistical Meetings. Salt Lake City (UT): [Jul 29 – Aug 2, 2007]. Constructing models of the spiking activity of neurons in the subthalamic nucleus of Parkinson‘s patients. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truccolo W, Eden UT, Fellows MR, Donoghue JP, Brown EN. A point process framework for relating neural spiking activity to spiking history, neural ensemble, and extrinsic covariate effects. J. Neurophysiol. 2005 Feb;93:1074–1089. doi: 10.1152/jn.00697.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown EN, Barbieri R, Eden UT, Frank LM. Likelihood methods for neural data analysis. In: Feng J, editor. Computational Neuroscience: A Comprehensive Approach. London, UK: CRC; 2003. pp. 253–286. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCullagh P P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gale JT. Ph.D. thesis. Ohio: Kent State Univ; 2004. Basis of periodic activities in the BG-thalamic-cortical system of the rhesus macaque. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santaniello S, Gale JT, Montgomery EB, Sarma SV. Modeling the effects of deep brain stimulation on sensorimotor cortex in normal and MPTP conditions. Proc. 32nd IEEE EMBS Conference; Buenos Aires (ARG); Sep 1–4, 2010; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery EB. Effects of GPi stimulation on human thalamic neuronal activity. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006 Dec;117:2691–2702. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]