Abstract

Detection of a salient stimulus is critical to cognitive functioning. A stimulus is salient when it appears infrequently, carries high motivational value, and/or when it dictates changes in behavior. Individuals with neurological conditions that implicate altered catecholaminergic signaling, such as those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, are impaired in detecting salient stimuli, a deficit that can be remediated by catecholaminergic medications. However, the effects of these catecholaminergic agents on cerebral activities during saliency processing within the context of the stop signal task are not clear. Here, we examined the effects of a single oral dose (45 mg) of methylphenidate in 24 healthy adults performing the stop signal task during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Compared to 92 demographically matched adults who did not receive any medications, the methylphenidate group showed higher activations in bilateral caudate head, primary motor cortex, and the right inferior parietal cortex during stop as compared to go trials (p<0.05, corrected for family-wise error of multiple comparisons). These results show that methylphenidate enhances saliency processing by promoting specific cerebral regional activities. These findings may suggest a neural basis for catecholaminergic treatment of attention disorders.

Introduction

We are drawn to salient stimuli when we navigate through a constantly changing world. Salient stimuli appear infrequently and/or demand change from a behavioral routine. By detecting and responding to salient stimuli, individuals learn from the outcome and enrich their cognitive repertoire. A number of behavioral paradigms are used to study saliency processing. For instance, in the Stroop task, an incongruent trial requires negotiation between conflicting responses as instructed by the color and word and is more salient, compared to a congruent trial. In the stop signal or go/nogo task, a stop/nogo signal is more salient compared to a go signal, because it instructs participants to refrain from a habitual response. Although the stop signal task is typically used to study cognitive control including response inhibition, the current study focused on the contrast between stop and go trials as an index of saliency response (Farr, Hu, Zhang & Li,2012; Hendrick, Ide, Luo & Li, 2010; Hendrick, Luo, Zhang & Li, 2011). Saliency processing activates frontal and parietal cortices as well as the thalamus and striatum (Farr et al., 2012; Ptak, 2012; Ptak & Schnider, 2010; Wardak, Ben Hamed, Olivier & Duhamel, 2012).

Catecholamines play a critical role in saliency processing and related cognitive functions. In humans, individuals with neurological or psychiatric disorders that involve altered catecholaminergic signaling demonstrate deficits in detecting salient stimuli (Maccari et al., 2012; Mannan, Hodgson, Husain & Kennard, 2008; Ortega, Lopez, Carrasco, Anllo-Vento & Aboitiz, 2012). For instance, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD is characterized by decreased dopamine D2/D3 receptors (Jucaite, Fernell, Halldin, Forssberg & Farde, 2005; Volkow et al., 2009) and increased dopamine transporter density (Fusar-Poli, Rubia, Rossi, Sartori & Balottin, 2012), both of which are related to dampened dopaminergic neurotransmission. Numerous studies demonstrate that children and adults with ADHD are impaired in performance and neural responses in cognitive challenges that require processing of salient stimuli (Bezdjian, Baker, Lozano & Raine, 2009; Desman et al., 2006; Fallgatter et al., 2004; Johnstone & Clarke, 2009; Karch et al., 2010; Smith, Johnstone & Barry, 2004; Spronk, Jonkman & Kemner, 2008; Tamm, Menon, Ringel & Reiss, 2004). In a go/no-go task, Tamm et al. (2004) and Fallgater et al. (2004) observed decreased activation of the cingulate cortex and supplementary motor area to no-go as compared to go stimuli in ADHD patients. In other cognitive tasks patients with ADHD show more variable reaction times, increased errors, deficient response inhibition and posterror behavioral modification (Bezdjian et al., 2009; Desman et al., 2006; Gooch, Snowling & Hulme, 2012; Mulligan et al., 2011; Shiels, Tamm & Epstein, 2012). These deficits are corrected by pharmaceuticals that increase catecholamines (Aron, Dowson, Sahakian & Robbins, 2003; Broyd et al., 2005; Jonkman, van Melis, Kemner & Marcus, 2007; Scheres et al., 2003; Tannock, Schachar, Carr, Chajczyk & Logan, 1989). For example, a common treatment for ADHD, methylphenidate increases catecholamines in the prefrontal cortex and striatum through blockade of dopamine and norepinephrine transporters (Berridge et al., 2006; 2012; Devilbiss & Berridge, 2006; Spencer, Klein & Berridge, 2012), and improves cognitive performance on various tasks, including the stop signal, go/no-go, flanker, and Stroop tasks (Aron et al., 2003; Berman, Douglas & Barr, 1999; Broyd et al., 2005; Moeller et al., in press; Tomasi et al., 2011; Zang et al., 2005). In all of these cognitive tasks, the detection of a salient stimulus – a no-go, stop or other incongruent signal – is key to an efficacious performance.

Notably, there appear to be contrasting influences of catecholaminergic signaling on saliency processing, with studies showing both increased and decreased cerebral activations. For instance, some studies show increased brain activations with methylphenidate or levodopa (Dodds et al., 2008; Hershey et al., 2004; Rubia et al., 2011; Zang et al., 2005), while others show decreased activations with these same drugs (Costa et al., 2012; Onur et al., 2011; Pauls et al., 2012). An additional observation concerns the effects on response inhibition, as indexed by the stop signal reaction time (SSRT) in the stop signal task. Some studies showed improved (decreased) SSRT with increasing catecholamines (Bari et al., 2009; 2011; Chamberlain et al., 2006; 2009; de Wit et al., 2002; Nandam et al., 2011; 2012; Turner et al., 2003), while other studies showed no effect or a baseline dependent effect on SSRT with increased catecholamines (Costa et al., 2012; Eagle et al., 2007; Fillmore et al., 2005; Nandam et al., 2011; Pauls et al., 2012).

In this study, we sought to clarify this literature by characterizing the effects of methylphenidate on saliency processing in the stop signal task. We administered 45 mg of methylphenidate orally in healthy adults and compared the results to a large cohort of demographically matched healthy participants who did not receive methylphenidate. We employed a between-subject design in order to avoid potential training or test-retest effects on behavioral performance and cerebral responses (Chao, Luo, Chang & Li, 2009; Manuel, Bernasconi & Spierer, 2012). That is, the effects of methylphenidate were not contrasted with placebo but compared to a large sample of individuals who did not receive methylphenidate. Our specific aim is to describe the effects of methylphenidate on cerebral activations during saliency processing by contrasting stop and go trials. An additional goal is to characterize the effects of methylphenidate on stop signal reaction time.

Methods

The study was performed under protocols approved by the Yale Human Investigation and Yale MRI Safety Committees. Subjects were recruited from New Haven and surrounding areas by advertisement, word of mouth and referrals. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after a full explanation of study procedures. Twenty-five healthy adults (17 females; age 25 ± 6 years; all right-handed) were recruited and compensated for their participation in the study after a phone screening of medical including psychiatric histories, current use of medications, and MR compatibility. On the morning of the scan, a physician conducted a more thorough in-person screening and review of medical and psychiatric history to confirm eligibility. All participants were admitted as outpatients to the Yale New Haven Hospital. All participants were without medical, neurological, or psychiatric conditions and denied history of head injury and current use of prescription medications or illicit substances. One subject was eliminated from the study because of a lesion found on the structural brain image. The resulting 24 participants comprised 16 females, with a mean age of 24 ± 4 years.

On the day of fMRI, participants completed a series of questionnaires, including the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, version 11 (BIS-11). Afterwards, participants rested in a recovery room for at least ten minutes, during which baseline heart rate, blood pressure, and anxiety measurements were taken. An hour prior to fMRI scans a physician examined and approved participants to receive either a single 45 mg oral dose of methylphenidate or placebo (single-blinded). This dosage was chosen to follow previous studies of healthy and ADHD populations with methylphenidate, so the results could best be compared to this earlier body of work. Thus, although participants did not know whether they would be receiving methylphenidate or placebo, all participants in the methylphenidate group received methylphenidate. From this time until the beginning of the structural MRI scans (approximately forty minutes), heart rate and blood pressure as well as anxiety were monitored every five minutes. During the fMRI scans, these measures were taken approximately every ten minutes between sessions. At each vital sign reading, participants also marked how anxious they felt on a visual analog scale from one (not anxious at all) to ten (extremely anxious). Data of a cohort of 92 healthy participants (58 females; age 25 ± 4 years; Farr et al., 2012; Li et al., 2008; 2010) scanned earlier under identical imaging protocols except without being given methylphenidate were used for comparison. Because of an unbalanced sample size in this comparison, we also performed a follow-up analysis and compared the current 24 participants (who received methylphenidate) with a subgroup of 24 of the 92 participants (who did not receive any medications) that were both matched individually and as a group.

Behavioral task

We employed a simple reaction time task in this stop-signal paradigm (Logan, Cowan & Davis, 1984; Li, Miliojevic, Kemp, Hong & Sinha, 2006; Li, Yan, Sinha & Lee, 2008a; Li et al., 2008b). There were two trial types: “go” and “stop,” randomly intermixed. A small dot appeared on the screen to engage attention at the beginning of a go trial. After a randomized time interval (fore-period) between 1 and 5 s, the dot turned into a circle (the “go” signal), prompting the subject to quickly press a button. The circle vanished at a button press or after 1 s had elapsed, whichever came first, and the trial terminated. A premature button press prior to the appearance of the circle also terminated the trial. A premature response was not counted as a correct or incorrect response. Approximately three quarters of all trials were go trials. The remaining one quarter were stop trials. In a stop trial, an additional “X,” the “stop” signal, appeared after and replaced the go signal. The subjects were told to withhold their button press upon seeing the stop signal. The stop signal delay (SSD) – the time interval between the go and stop signal – started at 200 ms and varied from one stop trial to the next according to a staircase procedure, increasing and decreasing by 67 ms each after a successful or failed stop trial (Levitt, 1970; De Jong, Coles, Logan & Gratton, 1990). There was an inter-trial-interval of 2s. Subjects were instructed to respond to the go signal quickly while keeping in mind that a stop signal could come up in a small number of trials. In the scanner each subject completed four 10-minute runs of the task. Depending on the actual stimulus timing (trials varied in fore-period duration) and speed of response, the total number of trials varied slightly across subjects in an experiment. With the staircase procedure, we anticipated that the subjects would succeed in withholding their response in approximately half of the stop trials. The stop signal reaction time was computed by subtracting the critical stop signal delay, or the estimated SSD required for a subject to get half of stop trials correct, from the median go reaction time (Li et al., 2008a).

Imaging protocol

Conventional T1-weighted spin echo sagittal anatomical images were acquired for slice localization using a 3T scanner (Siemens Trio). Anatomical images of the functional slice locations were next obtained with spin echo imaging in the axial plane parallel to the AC-PC line with TR = 300 ms, TE = 2.5 ms, bandwidth = 300 Hz/pixel, flip angle = 60°, field of view = 220 × 220 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, 32 slices with slice thickness = 4mm and no gap. A single high-resolution T1-weighted gradient-echo scan was applied on each participant. One hundred and seventy-six slices parallel to the AC-PC line covering the whole brain were acquired with TR=2530ms, TE=3.66ms, bandwidth = 181 Hz/pixel, flip angle = 7°, field of view = 256×256 mm, matrix = 256×256, 1mm3 isotropic voxels. Functional, blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signals were then acquired with a single-shot gradient echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence. Thirty-two axial slices parallel to the AC-PC line covering the whole brain were acquired with repetition time = 2,000 ms, echo time = 25 ms, bandwidth = 2004 Hz/pixel, flip angle = 85°, field of view = 220 × 220 mm, matrix = 64 × 64, 32 slices with slice thickness = 4mm and no gap. Three hundred images were acquired in each run for a total of four runs.

Data analysis and statistics

Data were analyzed with Statistical Parametric Mapping version 8 (SPM8, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College London, U.K.). Images from the first five TRs at the beginning of each trial were discarded to enable the signal to achieve steady-state equilibrium between radiofrequency pulsing and relaxation. Images of each individual subject were first corrected for slice timing and realigned (motion-corrected). A mean functional image volume was constructed for each subject for each run from the realigned image volumes. These mean images were co-registered with the high resolution structural image and then segmented for normalization to an MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) EPI template with affine registration followed by nonlinear transformation (Friston, Frith, Frackowiak & Turner, 1995a; Ashburner & Friston, 1999). The normalization parameters determined for the mean functional volume were then applied to the corresponding functional image volumes for each subject. Finally, images were smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 8 mm at Full Width at Half Maximum.

In the first general linear model (GLM), four main types of trial outcome were distinguished: go success (G), go error (F), stop success (SS), and stop error (SE) trial. Any stop trial, SS,SE, or a combined stop (S) trial involves incongruent goals between the prepotency to respond and the intention to withhold the response. S trials are also infrequent compared to go trials, and are thus highly salient. Thus, we interpreted the contrast of S>G as reflecting saliency processing. In addition, we examined other contrasts that reflect the component processes of cognitive control, including attention monitoring and response inhibition (SS>SE, Li et al., 2006; Duann, Ide, Luo & Li, 2009), error detection (SE>SS, Ide and Li, 2011a), and post-error slowing (pSi>pSni, where pSi and pSni each represented post-error go trials that increased and did not increase in reaction time; Li et al., 2008a; Ide and Li, 2011b).

A statistical analytical design was constructed for each individual subject, using the general linear model (GLM) with the onsets of go signal in each of these trial types convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF) and with the temporal derivative of the canonical HRF and entered as regressors in the model (Friston et al., 1995b). Realignment parameters in all 6 dimensions were also entered in the model. The data were high-pass filtered (1/128 Hz cutoff) to remove low-frequency signal drifts. Serial autocorrelation of the time series violated the GLM assumption of the independence of the error term and was corrected by a first-degree autoregressive or AR(1) model (Friston et al., 2000). The GLM estimated the component of variance that could be explained by each of the regressors.

The con or contrast (difference in β) images of the first-level analysis were used for the second-level group statistics (random effects analysis; Penny and Holmes, 2004). Brain regions were identified using an atlas (Duvernoy, 1999). All templates are in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space and voxel activations are presented in MNI coordinates.

To perform a balanced sample comparison, we created a mask from the two sample t-test results between the 24 MPH participants and the 92 no-MPH participants for stop as compared to go trials. We then used this mask to perform a small volume correction for a two sample t-test between the 24 MPH and 24 matched no-MPH participants.

Results

Behavioral performance and physiological response to methylphenidate

Behavioral performance in the SST is summarized in Table 1. Go trial reaction time (RT), coefficient of variation of go trial RT, stop success rate, stop signal reaction time and the effect size of post-error slowing was not different between groups. Participants who received methylphenidate showed a trend toward a higher go success rate (t(91,23)=2.17, p<0.035, ; alpha set at 0.01, considering a total of five performance parameters compared) when compared to participants who did not receive methylphenidate.

Table 1.

Demographics and behavioral performance during the stop signal task.

| number females |

age in years |

BIS score |

Go% |

Stop% |

GoRT (ms) |

SSRT (ms) |

PES (z- score) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPH (n=24) | 16 | 24±4 | 56.5±7.3 | 99.2±1.5 | 52.4±3.0 | 648.0±84.4 | 225.7±32.7 | 1.53±1.25 |

| no-MPH (n=92) | 58 | 25±4 | 59.8±9.7 | 97.9±3.0 | 53.4±3.8 | 669.9±119.0 | 218.1±59.1 | 1.66±1.47 |

| no-MPH (n=24) | 16 | 24±4 | 59.0±9.5 | 97.4±4.1 | 51.5±2.1 | 652.9±130.2 | 222.6±40.2 | 1.81±1.43 |

| MPH vs. 92 no-MPH | χ2=.1 | t=1.22 | t=1.51 | t=2.17 | t=1.17 | t=.84 | t=.60 | t=.40 |

| p<.84 | p<.22 | p<0.13 | p<.03 | p<.24 | p<.40 | p<.55 | p<.69 | |

| MPH vs. 24 no-MPH | χ2=0 | t=0.00 | t=1.02 | t=2.09 | t=1.01 | t=.70 | t=.29 | t=.72 |

| p<1.0 | p<1.0 | p<0.31 | p<.04 | p<.32 | p<.49 | p<.77 | p<.47 | |

BIS= Barratt Impulsivity Scale; Go% refers to the percentage of go trials to which the subject responded. Stop% refers to the percentage of successful stop trials. GoRT= mean go reaction time across trials. SSRT= stop signal reaction time, calculated by subtracting the critical stop signal delay from the median GoRT. PES= post-error slowing.

Heart rate and blood pressures were continuously recorded until 140 minutes after the administration of methylphenidate (Supplementary Figure 1). Increases were found in both heart rate (HR) (7%±13% change from baseline; t(23) = 2.48, p < 0.010) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) (10±7% change from baseline; t(23) = 6.95, p < 0.0001), but not diastolic blood pressure after administration of methylphenidate. Additionally, subjects reported increased anxiety on a ten point visual analog scale with one and ten each indicating not and extremely anxious (40±52% change from baseline; t(23) = 3.39, p < 0.001). These results validated the previously found cardiovascular and psychological effects of methylphenidate (Li et al., 2010).

Cerebral activations to saliency processing

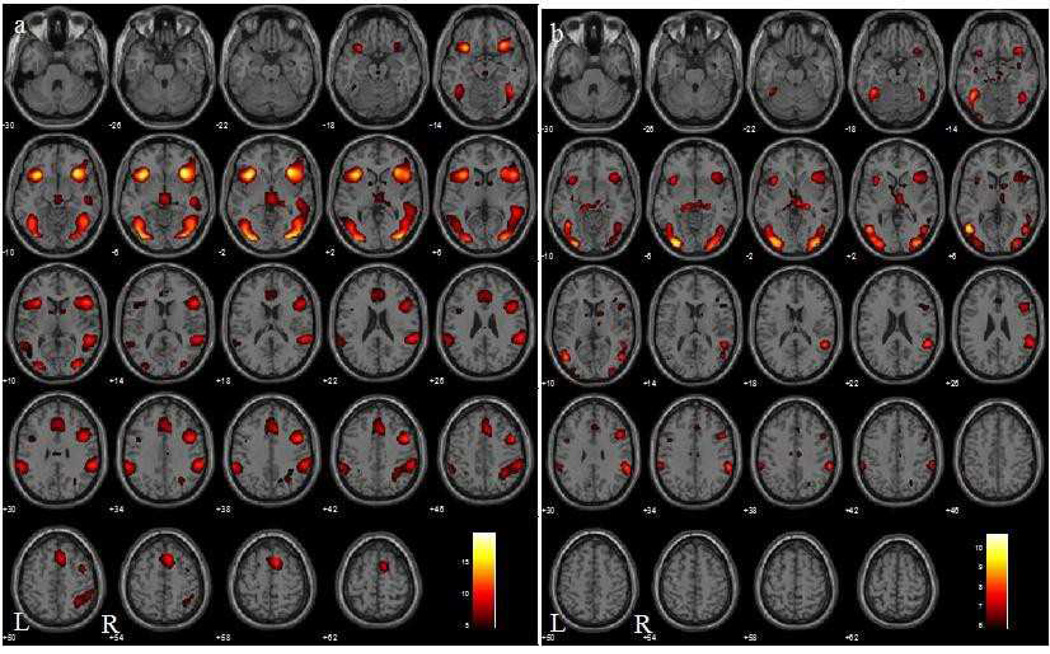

The contrast of S>G in MPH and no-MPH participants showed activations of a wide network of cortical and subcortical structures, including the pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA)/anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula, inferior parietal cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Brain activations during stop as compared to go (S>G) trials in 92 healthy subjects who did not receive methylphenidate (a; Farr et al., 2012) and 24 healthy subjects who received methylphenidate (b) at p < 0.05, FWE corrected (one-sample t-tests). BOLD contrasts are superimposed on a T1 structural image in axial sections from z=−10 to z=62. The adjacent sections are 4mm apart. The color bar represents voxel T value. Thus, higher T value in the no-MPH group may simply reflect its sample size rather than a higher magnitude of saliency related activity. Neurological orientation: R=right; L=left.

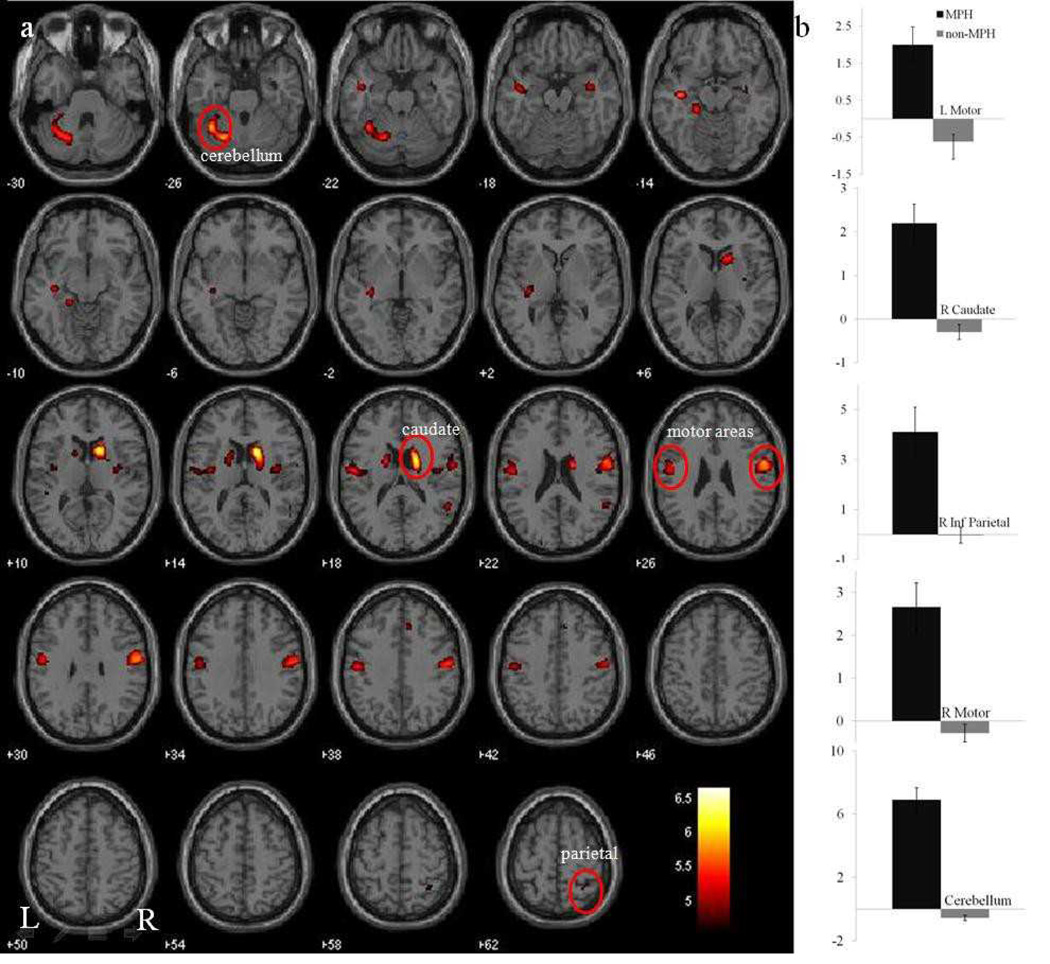

In a two sample t-test at p < 0.05, corrected for family-wise error (FWE) of multiple comparisons, the methylphenidate group showed greater activations in the bilateral caudate, primary motor cortex, and posterior insula, as well as the right inferior parietal cortex during stop as compared to go trials (Figure 2a; Table 2). We computed the effect size of saliency activation for these clusters – caudate, cerebellum, motor cortex, and inferior parietal cortex – to further illustrate the differences between the MPH and no-MPH groups (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Brain activations during stop as compared to go (S>G) trials in the MPH group (N=24) vs. no-MPH group (N=92) at p < 0.05, (two-sample t-test, FEW corrected.) BOLD contrasts are superimposed on a T1 structural image in axial sections from z=–30 to z=62. The adjacent sections are 4mm apart. Clusters reflect greater saliency related activations in the medicated as compared to non-medicated group. The color bar represents voxel T value. (b) Histogram of effect sizes for no-MPH and MPH subjects in five regions of interest (circled in red and labeled on a).

Table 2.

Cerebral activation during stop as compared to go (S>G) trials in the MPH group (N=24) vs. no-MPH group (N=92) at p < 0.05, FWE.

| MNI Coordinates (mm) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Size (voxels) |

Voxel Z Value |

X | Y | Z | Side | Identified Region |

| 171 | 6.1 | 15 | 11 | 13 | R | caudate |

| 4.42 | 27 | −1 | 7 | R | putamen | |

| 251 | 5.57 | −21 | −64 | −26 | L | cerebellum |

| 307 | 5.5 | 60 | −7 | 28 | R | precentral G |

| 4.97 | 39 | −7 | 13 | R | insula | |

| 100 | 5.44 | −45 | −7 | −20 | L | middle temporal G |

| 5.09 | −33 | −22 | 1 | L | superior temporal G | |

| 52 | 5.2 | −18 | −1 | 16 | L | caudate |

| 26 | 5.2 | 39 | −7 | −17 | R | middle temporal G |

| 232 | 5.19 | −54 | −10 | 19 | L | precentral G |

| 33 | 5.15 | −21 | −31 | −14 | L | parahippocampal G |

| 33 | 5.05 | 54 | −49 | 19 | R | superior temporal G |

| 19 | 5.02 | 36 | −49 | 61 | R | inferior parietal G |

| 13 | 4.9 | 9 | 29 | 37 | R/L | medial frontal G |

Statistical threshold: p<0.05, FWE; extent, 10 voxels. G, Gyrus; S, Sulcus; L, left; R, right.

We further confirmed these findings in a smaller group of 24 matched healthy participants versus the 24 MPH participants with small volume correction for a mask of the activations (Figure 2a). The results confirmed the differences in the temporal lobe, thalamus, caudate, insula, motor cortices, inferior parietal cortex, and cerebellum (p<.05, FWE corrected; Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the small volume correction for a mask of the activations in Figure 2a on the two sample t-test comparing the 24 MPH with 24 matched no-MPH participants during stop as compared to go trials.

| MNI Coordinates (mm) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Size (voxels) |

Voxel Z Value |

X | Y | Z | Side | Identified Region |

| 33 | 4.82 | −21 | −31 | −14 | L | parahippocampal G |

| 164 | 4.68 | 21 | −4 | 19 | R | thalamus |

| 4.67 | 24 | −1 | 16 | R | insula | |

| 4.2 | 21 | 17 | 4 | R | caudate | |

| 47 | 4.49 | −18 | −4 | 16 | L | caudate |

| 240 | 4.34 | −30 | −61 | −32 | L | cerebellum |

| 91 | 4.26 | −36 | −16 | −14 | L | parahippocampal G |

| 3.9 | −45 | −7 | −20 | L | subtemporal G | |

| 3.66 | −27 | −16 | 4 | L | putamen | |

| 292 | 3.72 | 54 | −1 | 25 | R | inferior frontal G |

| 3.63 | 63 | −7 | 31 | R | precentral G | |

| 3.42 | 30 | −10 | 13 | R | insula | |

| 24 | 3.56 | 36 | −7 | −17 | R | parahippocampal G |

Statistical threshold: p<0.05, FWE; extent, 10 voxels. G, Gyrus; S, Sulcus; L, left; R, right.

Cerebral activations to the component processes of cognitive control

We compared the methylphenidate and no-methylphenidate groups in other contrasts of cognitive control, including attentional monitoring/response inhibition (SS>SE), error processing (SE>SS), and post-error slowing (pSi>pSni, see Methods), none of which showed significant differences at a corrected threshold.

Discussion

Methylphenidate increases striatal and cortical activations to a salient stimulus

In this study, we manipulated catecholamine levels with the administration of methylphenidate in healthy individuals during the stop signal task. There were no notable changes in task performance, including the stop signal reaction time. However, participants who received methylphenidate showed higher brain activations during saliency processing in striatal and cortical regions including the caudate nuclei, primary motor cortices, inferior parietal cortex, and the cerebellum as compared to those who did not. These findings on saliency processing are consistent with contextual dependence of the effects of methylphenidate in releasing catecholamines (Volkow et al., 2004).

One of these areas, the caudate nucleus, receives direct and heavy dopaminergic projections from the midbrain (Altar & Hausar, 1987; Ohno, Sasa & Takatori, 1985; 1987; Wang, Moriwaki, Wang, Uhl & Pickel, 1997) and is widely implicated in processing salient stimuli (Crofts et al., 2001; Flagel et al., 2011; Zink, Pagnoni, Martin, Dhamala & Berns, 2003). Zink and colleagues (2003) used an attention task to investigate saliency processing independent of reward in healthy humans and showed increased caudate activity to salient events only when the distracters required a behavioral response. In an attentional shift task, dopaminergic depletion of the caudate through 6-hydroxydopamine infusions resulted in reduced distraction from task-irrelevant stimuli in monkeys (Crofts et al., 2001). Lesions of the caudate nucleus in humans disrupt attention and the extent of the lesion corresponds to the severity of cognitive impairments (Benke, Delazer, Bartha & Auer, 2003). In rats, a food cue induced c-fos mRNA expression in the caudate only when rats attributed salience to it during classical conditioning (Flagel et al., 2011). Additionally, genetically altered mice with reduced striatal dopamine have impairments in responding to novel objects which can be corrected with methylphenidate or levodopa (Brown et al., 2010). Together, these findings support a catecholamine-mediated attentional mechanism of the caudate nucleus.

The caudate nucleus in particular has been implicated in the pathogenesis of ADHD in both morphological and functional studies (Hynd et al., 1993; Castellanos et al., 1994; Volkow et al., 2007; Igual et al., 2012). Children with ADHD have small volumes of the caudate nucleus which seems to normalize by puberty (Carrey et al., 2012). Caudate nucleus was also found to be underactivated during the interference condition in an oddball task in patients with ADHD (Rubia et al., 2011a). Our current result that methylphenidate increases activation of the caudate nucleus during saliency processing parallels findings of increased caudate activation in a stop signal (Rubia, Cubillo, Woolley, Brammer & Smith, 2011b) and a rewarded continuous performance task (Rubia et al., 2009) with administration of methylphenidate versus a placebo in children with ADHD. The result is also broadly consistent with normalized activations of the right caudate in attention-related tasks in meta-analysis of long-term stimulant medication use in ADHD (Hart, Radua, Nakao, Mataix-Cols & Rubia, 2012).

As part of the ventral attention system, the inferior parietal cortex (IPC) responds to detection of a target stimulus (Bunge, Hazeltine, Scanlon, Rosen & Gabrieli, 2002; Corbetta & Shulman, 1998). The IPC showed underactivation during interference processing in a Simon task in patients with ADHD (Rubia et al., 2011a). The IPC increased activations with methylphenidate in ADHD participants during stop errors as compared to go trials in the stop signal task and during non-rewarded as compared to non-target trials in the continuous performance task (Rubia et al., 2009; 2011b) as well as in healthy participants during nonswitch errors as compared to correct trials in a reversal learning task (Dodds et al., 2008), all of which involve saliency processing. Positron emission tomography imaging showed significant reductions in cerebral activity in the IPC after methylphenidate administration in healthy participants, suggesting that methylphenidate causes significant changes in available dopamine in this brain area (Udo de Haes, Maguire, Jager, Paans & den Boer, 2007). Taken altogether, these results suggest that increased catecholamines in the IPC caused by methylphenidate may confer enhanced attention-related activation during the stop signal task.

Primary motor cortical activity is influenced by dopaminergic signaling (Ge et al., 2012; Hosp, Pekanovic, Rioult-Pedotti & Luft, 2011; Ostock et al., 2011). Dopaminergic projection to the primary motor cortex is necessary for motor learning; lesioning of the ventral tegmental area in rats does not inhibit previously learned motor skills, but prevents the learning of new motor tasks (Hosp et al., 2011). Administration of a moderate dose of levodopa in humans promotes plasticity of the primary motor cortex as monitored by evoked electric potentials (Monte-Silva, Liebetanz, Grundey, Paulus & Nitsche, 2010). Thus, the effects of methylphenidate on higher primary motor cortical activity are broadly consistent with these earlier results.

The cerebellum is critical to motor coordination (Manto & Oulad Ben Taib, 2013) and may compensate for the loss of basal ganglia inputs to cortex in Parkinson’s disease (Martinu & Monchi, 2012). Lesions of the cerebellum caused upregulation of dopamine D1 receptors in the basal ganglia and electrical stimulation of the cerebellum affects dopaminergic signaling in the midbrain and striatum (Dempsey & Richardson, 1987; Nieoullon & Dusticier, 1980), suggesting a dopaminergic process in this cerebellar mechanism. Recent research also indicates an important role of the cerebellum in cognitive functioning (Koziol, Budding & Chidekel, 2012; Leiner, Leiner & Dow, 1986; Stoodley, 2012), such as “training” frontal cortices in anticipating behavioral outcomes (Koziol et al., 2012) and facilitating prefrontal cortical processes in decision-making (Cisek & Kalaska, 2005), processes that involve catecholamines and saliency processing (Hershey et al., 2004; Kelly et al., 2009; Rogers et al., 2011).

Methylphenidate did not appear to alter stop signal reaction time

We did not observe any notable changes in task performance, including stop signal reaction time, consistent with many previous studies (Bari, Eagle, Mar, Robinson & Robbins, 2011; Costa et al., 2012; Eagle et al., 2011; Fillmore, Rush & Hays, 2005; Hamidovic, Kang & de Wit, 2008; Hershey et al., 2004; Kratz et al., 2009; Pauls et al., 2012), but at odds with others (Bari et al., 2009; Chamberlain et al., 2006; 2009; de Wit, Enggasser & Richards, 2002; Nandam et al., 2011; Li et al., 2010; Turner et al., 2003). It may be that the healthy participants in our study are already performing optimally and do not provide room for improvement with methylphenidate. For instance, in a stop signal task, methylphenidate decreased go reaction times in rats and showed a baseline-dependent effect on response inhibition, improving inhibitory control in slow but not fast responders (Eagle, Tufft, Goodchild & Robbins, 2007). This consideration may also account for the differences between healthy and clinical populations.

Catecholamines and saliency processing: other pre-clinical and clinical studies

In rodents, microinfusion of a dopamine agonist in the medial prefrontal cortex enhanced the salience of normally nonsalient stimuli in a fear conditioning task (Lauzon, Bishop & Laviolette, 2009). Selective depletion of norepinephrine in the mouse prefrontal cortex abolished saliency related signaling in the nucleus accumbens as tested by conditioned place preference to both rewarding and aversive stimuli (Ventura, Morrone & Puglisi-Allegra, 2007). In humans, neurological conditions other than ADHD also involve deficits in saliency processing. For instance, patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) are impaired in visual search for salient but not non-salient targets among distractors (Cormack, Gray, Ballard & Tovee, 2004; Horowitz, Choi, Horvitz, Cote & Mangels, 2006; Lubow, Dressler & Kaplan, 1999; Mannan et al., 2008). While age-matched individuals without PD benefit from the saliency of target stimulus, PD patients demonstrate similar reaction times identifying salient and non-salient target among distractors. Dopaminergic agents remediate this deficit by facilitating cognitive and emotive processing of salient stimuli in PD (Goerendt, Lawrence & Brooks, 2004; Nagy et al., 2012; Subramanian, Hindle, Jackson & Linden, 2010). Thus, the current findings may further our understanding of attention deficits in clinical conditions other than ADHD (Arnsten, 2006; Arnsten & Rubia, 2012).

Conclusions and limitations of the study

In summary, methylphenidate enhanced saliency processing during the stop signal task in healthy adult individuals. More research to understand the functional implications of methylphenidate-evoked striatal cortical activations during saliency processing could elucidate the neural bases of catecholaminergic treatment of attention disorders.

There are a few important limitations to this study. First and most significantly, we did not have a placebo control for the individuals who received methylphenidate. The placebo effect is thus a potential confound for the differences that we observed between the methylphenidate and no-methylphenidate group. Thus, although previous studies suggested that the effects of methylphenidate on cerebral activations can be distinguished from placebo in a number of different behavioral paradigms (Marquand et al., 2011; Volkow et al., 2006), the current results need to be replicated in a placebo-controlled study. Second, the contrast of stop versus go trials may involve motor response inhibition, although participants were successful only half of the time. It could not be ruled out that the observed neural changes were related to response inhibition but not captured by stop signal reaction time. On the other hand, while the stop signal task (SST) is mostly used to examine the psychological constructs and neural processes of cognitive control, including response inhibition (Duann et al., 2009; Ide et al., 2013; Li et al., 2006), it was known to involve a saliency, infrequency, or odd-ball effect. In fact, many imaging studies of the SST have attempted to account for this saliency effect in identifying the component processes of cognitive control. For instance, Chikazoe and colleagues included infrequent go trials, in addition to frequent go and infrequent nogo trials, in a behavioral task, in order to isolate neural surrogates independent of a saliency response (Chikazoe et al., 2009). Similarly, to disambiguate the role of the right inferior frontal cortex in the SST, Hampshire and colleagues introduced a stop trial to which participants did not need to respond (by withholding the button press) and showed that the right inferior frontal cortex is recruited when a salient cue is detected (Hampshire et al., 2010). Thus, saliency processing is intrinsic to the SST. Third, methylphenidate influences both dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission. While there is heavy dopaminergic innervation of the caudate nucleus, the cortical mantle receives both dopaminergic and noradrenergic inputs. Thus, it remains to be determined whether and how blockade of dopaminergic and/or noradrenergic transporters by methylphenidate accounts for the current findings. Fourth, the methylphenidate group represents a small sample, which limits the power to detecting changes in behavioral and neural measures of the component processes of cognitive control. Thus, although we did not observe any effects on response inhibition, error processing, and post-error slowing, these negative results need to be confirmed with larger samples in future work. In addition, the effects of methylphenidate may depend on individual characteristics such as impulsivity, which cannot be adequately addressed in a small sample with limited heterogeneity. Fifth, we did not use any standardized measure to screen the psychiatric status of the healthy participants. Finally, this study involved only healthy adult participants. Thus, the implications of the current results cannot be generalized to patient populations including ADHD or Parkinson’s disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants T32 NS07224, R01DA023248, R21AA018004, K02DA026990, and P20DA027844, a NARSAD Young Investigator Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Drug Abuse, National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Amy Arnsten for her many helpful discussions throughout the entire study.

WORKS CITED

- Adams ZW, Roberts WM, Milich R, Fillmore MT. Does response variability predict distractibility among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(2):427–436. doi: 10.1037/a0022112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar CA, Hauser K. Topography of substantia nigra innervation by D1 receptor-containing striatal neurons. Brain Research. 1987;410(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(87)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Fundamentals of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: circuits and pathways. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;678(Suppl):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Rubia K. Neurobiological circuits regulating attention, cognitive control, motivation, and emotion: disruptions in neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(4):356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Dowson JH, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Methylphenidate improves response inhibition in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1465–1468. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00609-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Nonlinear spatial normalization using basis functions. Human Brain Mapping. 1999;7(4):254–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)7:4<254::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin RL, Chelonis JJ, Flake RA, Edwards MC, Feild CR, Meaux JB, Paule MG. Effect of methylphenidate on time perception in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12(1):57–64. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Eagle DM, Mar AC, Robinson ES, Robbins TW. Dissociable effects of noradrenaline, dopamine, and serotonin uptake blockade on stop task performance in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;205(2):273–283. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Mar AC, Theobald DE, Elands SA, Oganya KC, Eagle DM, Robbins TW. Prefrontal and monoaminergic contributions to stop-signal task performance in rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(25):9254–9263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1543-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellgrove MA, Hester R, Garavan H. The functional neuroanatomical correlates of response variability: evidence from a response inhibition task. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(14):1910–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke T, Delazer M, Bartha L, Auer A. Basal ganglia lesions and the theory of fronto-subcortical loops: neuropsychological findings in two patients with left caudate lesions. Neurocase. 2003;9(1):70–85. doi: 10.1076/neur.9.1.70.14374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman T, Douglas VI, Barr RG. Effects of methylphenidate on complex cognitive processing in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(1):90–105. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Devilbiss DM, Andrzejewski ME, Arnsten AF, Kelley AE, Schmeichel B, Spencer RC. Methylphenidate preferentially increases catecholamine neurotransmission within the prefrontal cortex at low doses that enhance cognitive function. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(10):1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Shumsky JS, Andrzejewski ME, McGaughy JA, Spencer RC, Devilbiss DM, Waterhouse BD. Differential sensitivity to psychostimulants across prefrontal cognitive tasks: differential involvement of noradrenergic alpha(1) - and alpha(2)-receptors. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71(5):467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezdjian S, Baker LA, Lozano DI, Raine A. Assessing inattention and impulsivity in children during the Go/NoGo task. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2009;27(Pt 2):365–383. doi: 10.1348/026151008X314919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):237–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66915-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JA, Emnett RJ, White CR, Yuede CM, Conyers SB, O'Malley KL, Gutmann DH. Reduced striatal dopamine underlies the attention system dysfunction in neurofibromatosis-1 mutant mice. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19(22):4515–4528. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyd SJ, Johnstone SJ, Barry RJ, Clarke AR, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M, Lawrence CA. The effect of methylphenidate on response inhibition and the event-related potential of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2005;58(1):47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge SA, Hazeltine E, Scanlon MD, Rosen AC, Gabrieli JD. Dissociable contributions of prefrontal and parietal cortices to response selection. Neuroimage. 2002;17(3):1562–1571. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrey N, Bernier D, Emms M, Gunde E, Sparkes S, Macmaster FP, Rusak B. Smaller volumes of caudate nuclei in prepubertal children with ADHD: impact of age. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46(8):1066–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Giedd JN, Eckburg P, Marsh WL, Vaituzis AC, Kaysen D, Rapoport JL. Quantitative morphology of the caudate nucleus in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(12):1791–1796. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Del Campo N, Dowson J, Muller U, Clark L, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Atomoxetine improved response inhibition in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(9):977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Muller U, Blackwell AD, Clark L, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Neurochemical modulation of response inhibition and probabilistic learning in humans. Science. 2006;311(5762):861–863. doi: 10.1126/science.1121218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HH, Luo X, Chang JL, Li CS. Activation of the pre-supplementary motor area but not inferior prefrontal cortex in association with short stop signal reaction time--an intra-subject analysis. BMC Neuroscience. 2009;10:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikazoe J, Jimura K, Asari T, Yamashita K, Morimoto H, Hirose S, Miyashita Y, Konishi S. Functional dissociation in right inferior frontal cortex during performance of go/no-go task. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(1):146–152. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P, Kalaska JF. Neural correlates of reaching decisions in dorsal premotor cortex: specification of multiple direction choices and final selection of action. Neuron. 2005;45(5):801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Human cortical mechanisms of visual attention during orienting and search. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 1998;353(1373):1353–1362. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack F, Gray A, Ballard C, Tovee MJ. A failure of 'pop-out' in visual search tasks in dementia with Lewy Bodies as compared to Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19(8):763–772. doi: 10.1002/gps.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Riedel M, Pogarell O, Menzel-Zelnitschek F, Schwarz M, Reiser M, Ettinger U. Methylphenidate effects on neural activity during response inhibition in healthy humans. Cerebral Cortex. 2013;23(5):1179–1189. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts HS, Dalley JW, Collins P, Van Denderen JC, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Differential effects of 6-OHDA lesions of the frontal cortex and caudate nucleus on the ability to acquire an attentional set. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11(11):1015–1026. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.11.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie J, Arnold P, Paterson A, Swanson J, Dupuis A, Li X, Schachar RJ. Response inhibition and ADHD traits: correlates and heritability in a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;41(3):497–507. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9693-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong MG, Coles R, Logan GD, Gratton G. In search of the point of no return: the control of response processes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1990;16(1):164–182. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.16.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Enggasser JL, Richards JB. Acute administration of d-amphetamine decreases impulsivity in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(5):813–825. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey CW, Richardson DE. Paleocerebellar stimulation induces in vivo release of endogenously synthesized [3H]dopamine and [3H]norepinephrine from rat caudal dorsomedial nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 1987;21(2):565–571. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desman C, Schneider A, Ziegler-Kirbach E, Petermann F, Mohr B, Hampel P. [Behavioural inhibition and emotion regulation among boys with ADHD during a go- /nogo-task] Praxis fur Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie. 2006;55(5):328–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito EE, Blackwell AD, Clark L, Kent L, Dezsery AM, Turner DC, Sahakian BJ. Methylphenidate improves response inhibition but not reflection-impulsivity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202(1–3):531–539. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1337-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds CM, Muller U, Clark L, van Loon A, Cools R, Robbins TW. Methylphenidate has differential effects on blood oxygenation level-dependent signal related to cognitive subprocesses of reversal learning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(23):5976–5982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1153-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duann JR, Ide JS, Luo X, Li CS. Functional connectivity delineates distinct roles of the inferior frontal cortex and presupplementary motor area in stop signal inhibition. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(32):10171–10179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1300-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvernoy CS, Meyer C, Seifert-Klauss V, Dayanikli F, Matsunari I, Rattenhuber J, Schwaiger M. Gender differences in myocardial blood flow dynamics: lipid profile and hemodynamic effects. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;33(2):463–470. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle DM, Tufft MR, Goodchild HL, Robbins TW. Differential effects of modafinil and methylphenidate on stop-signal reaction time task performance in the rat, and interactions with the dopamine receptor antagonist cis-flupenthixol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;192(2):193–206. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle DM, Wong JC, Allan ME, Mar AC, Theobald DE, Robbins TW. Contrasting roles for dopamine D1 and D2 receptor subtypes in the dorsomedial striatum but not the nucleus accumbens core during behavioral inhibition in the stop-signal task in rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(20):7349–7356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6182-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallgatter AJ, Ehlis AC, Seifert J, Strik WK, Scheuerpflug P, Zillessen KE, Warnke A. Altered response control and anterior cingulate function in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder boys. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;115(4):973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr OM, Hu S, Zhang S, Li CS. Decreased saliency processing as a neural measure of Barratt impulsivity in healthy adults. Neuroimage. 2012;63(3):1070–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Rush CR, Hays L. Cocaine improves inhibitory control in a human model of response conflict. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;13(4):327–335. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Cameron CM, Pickup KN, Watson SJ, Akil H, Robinson TE. A food predictive cue must be attributed with incentive salience for it to induce c-fos mRNA expression in cortico-striatal-thalamic brain regions. Neuroscience. 2011;196:80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman NP, Miyake A, Young SE, Defries JC, Corley RP, Hewitt JK. Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of Experimental Psychology and Genetics. 2008;137(2):201–225. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Characterizing dynamic brain responses with fMRI: a multivariate approach. Neuroimage. 1995a;2(2):166–172. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Poline JB, Grasby PJ, Williams SC, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited. Neuroimage. 1995b;2(1):45–53. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Josephs O, Zarahn E, Holmes AP, Rouquette S, Poline J. To smooth or not to smooth? Bias and efficiency in fMRI time-series analysis. Neuroimage. 2000;12(2):196–208. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Rubia K, Rossi G, Sartori G, Balottin U. Striatal dopamine transporter alterations in ADHD: pathophysiology or adaptation to psychostimulants? A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(3):264–272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11060940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Yang C, Li M, Li J, Chang X, Fu J, Gao G. Dopamine depletion increases the power and coherence of high-voltage spindles in the globus pallidus and motor cortex of freely moving rats. Brain Research. 2012;1465:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goerendt IK, Lawrence AD, Brooks DJ. Reward processing in health and Parkinson's disease: neural organization and reorganization. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14(1):73–80. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooch D, Snowling MJ, Hulme C. Reaction time variability in children with ADHD symptoms and/or dyslexia. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2012;37(5):453–472. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2011.650809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidovic A, Kang UJ, de Wit H. Effects of low to moderate acute doses of pramipexole on impulsivity and cognition in healthy volunteers. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;28(1):45–51. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e3181602fab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire A, Chamberlain SR, Monti MM, Duncan J, Owen AM. The role of the right inferior frontal gyrus: inhibition and attentional control. Neuroimage. 2010;50(3):1313–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K. Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(2):185–198. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick OM, Ide JS, Luo X, Li CS. Dissociable processes of cognitive control during error and non-error conflicts: a study of the stop signal task. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick OM, Luo X, Zhang S, Li CS. Saliency processing and obesity: a preliminary imaging study of the stop signal task. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(9):1796–1802. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman L, Shtayermman O, Aksnes B, Anzalone M, Cormerais A, Liodice C. The use of prescription stimulants to enhance academic performance among college students in health care programs. Journal of Physician Assisted Education. 2011;22(4):15–22. doi: 10.1097/01367895-201122040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey T, Black KJ, Hartlein J, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carl JL, Perlmutter JS. Dopaminergic modulation of response inhibition: an fMRI study. Brain Research: Cognitive Brain Research. 2004;20(3):438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz TS, Choi WY, Horvitz JC, Cote LJ, Mangels JA. Visual search deficits in Parkinson's disease are attenuated by bottom-up target salience and top-down information. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(10):1962–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosp JA, Pekanovic A, Rioult-Pedotti MS, Luft AR. Dopaminergic projections from midbrain to primary motor cortex mediate motor skill learning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(7):2481–2487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5411-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynd GW, Hern KL, Novey ES, Eliopulos D, Marshall R, Gonzalez JJ, Voeller KK. Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and asymmetry of the caudate nucleus. Journal of Child Neurology. 1993;8(4):339–347. doi: 10.1177/088307389300800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide JS, Li CS. A cerebellar thalamic cortical circuit for error-related cognitive control. Neuroimage. 2011;54(1):455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide JS, Li CS. Error-related functional connectivity of the habenula in humans. Frontiers Human Neuroscience. 2011;5:25. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igual L, Soliva JC, Escalera S, Gimeno R, Vilarroya O, Radeva P. Automatic brain caudate nuclei segmentation and classification in diagnostic of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 2012;36(8):591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Barry E, Bellgrove MA, Cox M, Kelly SP, Daibhis A, Gill M. Dissociation in response to methylphenidate on response variability in a group of medication naive children with ADHD. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(5):1532–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone SJ, Clarke AR. Dysfunctional response preparation and inhibition during a visual Go/No-go task in children with two subtypes of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2009;166(2–3):223–237. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman LM, van Melis JJ, Kemner C, Markus CR. Methylphenidate improves deficient error evaluation in children with ADHD: an event-related brain potential study. Biological Psychology. 2007;76(3):217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucaite A, Fernell E, Halldin C, Forssberg H, Farde L. Reduced midbrain dopamine transporter binding in male adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: association between striatal dopamine markers and motor hyperactivity. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(3):229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch S, Feuerecker R, Leicht G, Meindl T, Hantschk I, Kirsch V, Mulert C. Separating distinct aspects of the voluntary selection between response alternatives: N2- and P3-related BOLD responses. Neuroimage. 2010;51(1):356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C, de Zubicaray G, Di Martino A, Copland DA, Reiss PT, Klein DF, McMahon K. L-dopa modulates functional connectivity in striatal cognitive and motor networks: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(22):7364–7378. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0810-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol LF, Budding DE, Chidekel D. From movement to thought: executive function, embodied cognition, and the cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2012;11(2):505–525. doi: 10.1007/s12311-011-0321-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz O, Diruf MS, Studer P, Gierow W, Buchmann J, Moll GH, Heinrich H. Effects of methylphenidate on motor system excitability in a response inhibition task. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2009;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauzon NM, Bishop SF, Laviolette SR. Dopamine D1 versus D4 receptors differentially modulate the encoding of salient versus nonsalient emotional information in the medial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(15):4836–4845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0178-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiner HC, Leiner AL, Dow RS. Does the cerebellum contribute to mental skills? Behavioral Neuroscience. 1986;100(4):443–454. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.100.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Huang C, Yan P, Paliwal P, Constable RT, Sinha R. Neural correlates of post-error slowing during a stop signal task: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20(6):1021–1029. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Milivojevic V, Kemp K, Hong K, Sinha R. Performance monitoring and stop signal inhibition in abstinent patients with cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85(3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Morgan PT, Matuskey D, Abdelghany O, Luo X, Chang JL, Malison RT. Biological markers of the effects of intravenous methylphenidate on improving inhibitory control in cocaine-dependent patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences U S A. 2010;107(32):14455–14459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002467107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Yan P, Chao HH, Sinha R, Paliwal P, Constable RT, Lee TW. Error-specific medial cortical and subcortical activity during the stop signal task: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience. 2008;155(4):1142–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Yan P, Sinha R, Lee TW. Subcortical processes of motor response inhibition during a stop signal task. Neuroimage. 2008;41(4):1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lijffijt M, Kenemans JL, ter Wal A, Quik EH, Kemner C, Westenberg H, van Engeland H. Dose-related effect of methylphenidate on stopping and changing in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. European Psychiatry. 2006;21(8):544–547. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Cowan WB, Davis KA. On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction time responses: a model and a method. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance. 1984;10(2):276–291. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubow RE, Dressler R, Kaplan O. The effects of target and distractor familiarity on visual search in de novo Parkinson's disease patients: latent inhibition and novel pop-out. Neuropsychology. 1999;13(3):415–423. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.13.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccari L, Casagrande M, Martella D, Anolfo M, Rosa C, Fuentes LJ, Pasini A. Change Blindness in Children With ADHD: A Selective Impairment in Visual Search? Journal of Attention Disorders. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1087054711433294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannan SK, Hodgson TL, Husain M, Kennard C. Eye movements in visual search indicate impaired saliency processing in Parkinson's disease. Progress in Brain Research. 2008;171:559–562. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00679-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manto M, Oulad Ben Taib N. The contributions of the cerebellum in sensorimotor control: what are the prevailing opinions which will guide forthcoming studies? Cerebellum. 2013;12(3):313–315. doi: 10.1007/s12311-013-0449-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel AL, Bernasconi F, Spierer L. Plastic modifications within inhibitory control networks induced by practicing a stop-signal task: an electrical neuroimaging study. Cortex. 2013;49(4):1141–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquand AF, De Simoni S, O'Daly OG, Williams SC, Mourão-Miranda J, Mehta MA. Pattern classification of working memory networks reveals differential effects of methylphenidate, atomoxetine, and placebo in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 36(6):1237–1247. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinu K, Monchi O. Cortico-basal ganglia and cortico-cerebellar circuits in Parkinson's disease: pathophysiology or compensation? Behavioral Neuroscience. 2013;127(2):222–236. doi: 10.1037/a0031226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller SJ, Honorio J, Tomasi D, Parvaz MA, Woicik PA, Volkow ND, Goldstein RZ. Methylphenidate Enhances Executive Function and Optimizes Prefrontal Function in Both Health and Cocaine Addiction. Cerebral Cortex. 2012 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs345. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte-Silva K, Liebetanz D, Grundey J, Paulus W, Nitsche MA. Dosage-dependent non-linear effect of L-dopa on human motor cortex plasticity. Journal of Physiology. 2010;588(Pt 18):3415–3424. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.190181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan RC, Knopik VS, Sweet LH, Fischer M, Seidenberg M, Rao SM. Neural correlates of inhibitory control in adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from the Milwaukee longitudinal sample. Psychiatry Research. 2011;194(2):119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy H, Levy-Gigi E, Somlai Z, Takats A, Bereczki D, Keri S. The effect of dopamine agonists on adaptive and aberrant salience in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):950–958. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandam LS, Hester R, Wagner J, Cummins TD, Garner K, Dean AJ, Bellgrove MA. Methylphenidate but not atomoxetine or citalopram modulates inhibitory control and response time variability. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69(9):902–904. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandam LS, Hester R, Wagner J, Dean AJ, Messer C, Honeysett A, Bellgrove MA. Dopamine D(2) receptor modulation of human response inhibition and error awareness. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;25(4):649–656. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieoullon A, Dusticier N. Changes in dopamine release in caudate nuclei and substantia nigrae after electrical stimulation of the posterior interposate nucleus of cat cerebellum. Neuroscience Letters. 1980;17(1–2):167–172. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. The ADHD response-inhibition deficit as measured by the stop task: replication with DSM-IV combined type, extension, and qualification. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27(5):393–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1021980002473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno Y, Sasa M, Takaori S. Dopamine D-2 receptor-mediated excitation of caudate nucleus neurons from the substantia nigra. Life Sciences. 1985;37(16):1515–1521. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno Y, Sasa M, Takaori S. Coexistence of inhibitory dopamine D-1 and excitatory D-2 receptors on the same caudate nucleus neurons. Life Sciences. 1987;40(19):1937–1945. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R, Lopez V, Carrasco X, Anllo-Vento L, Aboitiz F. Exogenous orienting of visual-spatial attention in ADHD children. Brain Research. 2013;1493:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostock CY, Dupre KB, Jaunarajs KL, Walters H, George J, Krolewski D, Bishop C. Role of the primary motor cortex in L-Dopa-induced dyskinesia and its modulation by 5-HT1A receptor stimulation. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(4):753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overtoom CC, Verbaten MN, Kemner C, Kenemans JL, van Engeland H, Buitelaar JK, Koelega HS. Effects of methylphenidate, desipramine, and L-dopa on attention and inhibition in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Behavioral Brain Research. 2003;145(1–2):7–15. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauls AM, O'Daly OG, Rubia K, Riedel WJ, Williams SC, Mehta MA. Methylphenidate effects on prefrontal functioning during attentional-capture and response inhibition. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72(2):142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptak R. The frontoparietal attention network of the human brain: action, saliency, and a priority map of the environment. Neuroscientist. 2012;18(5):502–515. doi: 10.1177/1073858411409051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptak R, Schnider A. The dorsal attention network mediates orienting toward behaviorally relevant stimuli in spatial neglect. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(38):12557–12565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2722-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TD, Dickson PE, Heck DH, Goldowitz D, Mittleman G, Blaha CD. Connecting the dots of the cerebro-cerebellar role in cognitive function: neuronal pathways for cerebellar modulation of dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex. Synapse. 2011;65(11):1204–1212. doi: 10.1002/syn.20960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Cubillo A, Woolley J, Brammer MJ, Smith A. Disorder-specific dysfunctions in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder compared to patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder during interference inhibition and attention allocation. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32(4):601–611. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Halari R, Cubillo A, Smith AB, Mohammad AM, Brammer M, Taylor E. Methylphenidate normalizes fronto-striatal underactivation during interference inhibition in medication-naive boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(8):1575–1586. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Oosterlaan J, Swanson J, Morein-Zamir S, Meiran N, Schut H, Sergeant JA. The effect of methylphenidate on three forms of response inhibition in boys with AD/HD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31(1):105–120. doi: 10.1023/a:1021729501230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels K, Tamm L, Epstein JN. Deficient post-error slowing in children with ADHD is limited to the inattentive subtype. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2012;18(3):612–617. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Johnstone SJ, Barry RJ. Inhibitory processing during the Go/NoGo task: an ERP analysis of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;115(6):1320–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spronk M, Jonkman LM, Kemner C. Response inhibition and attention processing in 5- to 7-year-old children with and without symptoms of ADHD: An ERP study. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008;119(12):2738–2752. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley CJ. The cerebellum and cognition: evidence from functional imaging studies. Cerebellum. 2012;11(2):352–365. doi: 10.1007/s12311-011-0260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian L, Hindle JV, Jackson MC, Linden DE. Dopamine boosts memory for angry faces in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2010;25(16):2792–2799. doi: 10.1002/mds.23420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm L, Menon V, Ringel J, Reiss AL. Event-related FMRI evidence of frontotemporal involvement in aberrant response inhibition and task switching in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(11):1430–1440. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000140452.51205.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannock R, Schachar RJ, Carr RP, Chajczyk D, Logan GD. Effects of methylphenidate on inhibitory control in hyperactive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1989;17(5):473–491. doi: 10.1007/BF00916508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi D, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Wang R, Telang F, Caparelli EC, Wong C, Jayne M, Fowler JS. Methylphenidate enhances brain activation and deactivation responses to visual attention and working memory tasks in healthy controls. Neuroimage. 2011;54(4):3101–3110. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DC, Robbins TW, Clark L, Aron AR, Dowson J, Sahakian BJ. Cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165(3):260–269. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo de Haes JI, Maguire RP, Jager PL, Paans AM, den Boer JA. Methylphenidate-induced activation of the anterior cingulate but not the striatum: a [15O]H2O PET study in healthy volunteers. Human Brain Mapping. 2007;28(7):625–635. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura R, Morrone C, Puglisi-Allegra S. Prefrontal/accumbal catecholamine system determines motivational salience attribution to both reward- and aversion-related stimuli. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences U S A. 2007;104(12):5181–5186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610178104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Swanson JM, Telang F. Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results of imaging studies and treatment implications. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64(11):1575–1579. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.11.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Telang F, Maynard L, Logan J, Swanson JM. Evidence that methylphenidate enhances the saliency of a mathematical task by increasing dopamine in the human brain. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1173–1180. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Kollins SH, Wigal TL, Newcorn JH, Telang F, Swanson JM. Evaluating dopamine reward pathway in ADHD: clinical implications. JAMA. 2009;302(10):1084–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ma Y, Fowler JS, Wong C, Jayne M, Telang F, Swanson JM. Effects of expectation on the brain metabolic responses to methylphenidate and to its placebo in non-drug abusing subjects. Neuroimage. 2006;32(4):1782–1792. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.04.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Moriwaki A, Wang JB, Uhl GR, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical localization of mu-opioid receptors in dendritic targets of dopaminergic terminals in the rat caudate-putamen nucleus. Neuroscience. 1997;81(3):757–771. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardak C, Ben Hamed S, Olivier E, Duhamel JR. Differential effects of parietal and frontal inactivations on reaction times distributions in a visual search task. Frontiers Integrative Neuroscience. 2012;6:39. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, Sgambati S, Rotrosen J, Sawtelle R, Fusillo S. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):21–31. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang YF, Jin Z, Weng XC, Zhang L, Zeng YW, Yang L, Faraone SV. Functional MRI in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: evidence for hypofrontality. Brain Development. 2005;27(8):544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Hu S, Chao HH, Luo X, Farr OM, Li CS. Cerebral correlates of skin conductance responses in a cognitive task. Neuroimage. 2012;62(3):1489–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink CF, Pagnoni G, Martin ME, Dhamala M, Berns GS. Human striatal response to salient nonrewarding stimuli. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(22):8092–8097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-08092.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.