SUMMARY

Cells of the innate immune system are essential for host defenses against primary microbial pathogen infections, yet their involvement in effective memory responses of vaccinated individuals has been poorly investigated. Here we show that memory T cells instruct innate cells to become potent effector cells in a systemic and a mucosal model of infection. Memory T cells controlled phagocyte, dendritic cell and NK or NK T cell mobilization and induction of a strong program of differentiation, which included their expression of effector cytokines and microbicidal pathways, all of which were delayed in non-vaccinated hosts. Disruption of IFN-γ-signaling in Ly6C+ monocytes, dendritic cells and macrophages impaired these processes and the control of pathogen growth. These results reveal how memory T cells, through rapid secretion of IFN-γ, orchestrate extensive modifications of host innate immune responses that are essential for effective protection of vaccinated hosts.

INTRODUCTION

Cells of the innate immune system are essential for early sensing and protective inflammatory responses against microbial pathogens (Medzhitov, 2007). These cells include tissue-resident macrophages, blood-derived monocytes and neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), NK and NK T lymphocytes that can quickly be mobilized and differentiate into robust effector cells important for the control of initial pathogen growth. Complete eradication of pathogens from infected tissues and sterilizing immunity usually requires T and B lymphocytes, yet mobilization of these cells from the adaptive immune system during primary pathogen encounter is a lengthy process (Williams and Bevan, 2007). During immunization, pathogen-specific T cells undergo priming, expand and differentiate into memory cells that acquire enhanced functional features including improved ability to survive, to quickly express high levels of effector functions and to traffic to infected tissues. Thus in immunized hosts, memory T lymphocytes are capable of mediating rapid and efficient host protection (Sallusto et al., 2010). In the course of various infections, IFN-γ always appears as a key cytokine produced by all subsets of T and NK lymphocytes, and is often essential for effective protection (Billiau and Matthys, 2009; Hu and Ivashkiv, 2009; Zhang et al., 2008). Many reports have established the pleitropic functions of IFN-γ in inducing immune-response related genes and robust ‘Th1 cell’ polarization, differentiation of ‘M1’ macrophages and expression of microbicidal pathways (Martinez et al., 2009; Mosmann and Coffman, 1989).

We and others have demonstrated that early activation and differentiation of memory, but not naïve CD8+ T cells into IFN-γ-secreting effector cells occurs within only a few hours after a challenge infection and in response to the inflammatory cytokines interleukin-18 (IL-18) 18, IL-12 and IL-15 (Berg et al., 2003; Kupz et al., 2012; Raue et al., 2013; Soudja et al., 2012). Once reactivated, memory T cells rapidly provide IFN-γ but also other inflammatory factors that modulate host innate immune defenses (Narni-Mancinelli et al., 2007; Narni-Mancinelli et al., 2011; Strutt et al., 2010). However, to what extent IFN-γ mobilizes cells of the innate immune system during a dynamic memory response in vivo, the precise mechanisms of interaction between memory T cells and innate immune cells and how important are these processes for protective immunity, while significant to our understanding of memory T cell functions, has not been carefully investigated. Herein, we hypothesize that IFN-γ-dependent modulation of innate immune responses is an essential component of protection in vaccinated hosts during challenge infection with virulent pathogens. We analyze the activation, differentiation and trafficking of innate myeloid and lymphoid cells in naïve or vaccinated mice undergoing a challenge infection. Finally, we dissect the mechanism by which memory T cells are able to orchestrate antimicrobial systemic and mucosal innate immune responses, through rapid and highly effective IFN-γ-dependent mobilization of early microbicidal response of innate effector cells.

RESULTS

Robust activation of innate immune cells during recall infection

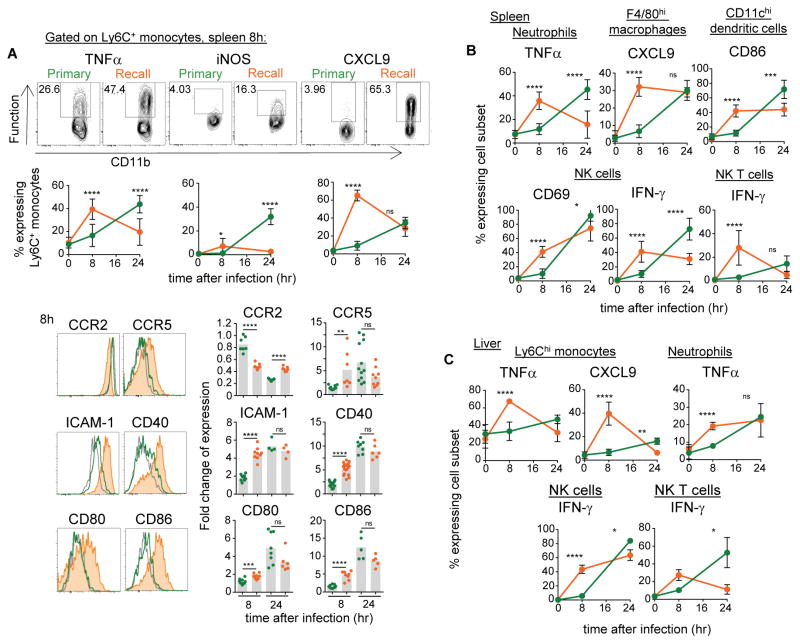

We first investigated whether the innate immune response in vaccinated hosts was different from that of unimmunized mice. For this, we eitherinjected WT C57BL/6 (B6) mice with PBS or with attenuated ΔActA Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) or sub-lethal doses of WT Lm, and 5–6 weeks later challenged mice with WT Lm and monitored the early activation of innate immune cells in spleen and liver (Figure 1). We compared expression of markers of activation including costimulatory and adhesion molecules and expression of key chemotactic receptors and effector functions on Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes, neutrophils, tissue-resident F4/80+ macrophages, CD11chi DCs and innate NK and NK T lymphocytes, in primary and secondary challenged mice. By 8 hrs post infection, Ly6C+ monocytes in vaccinated but not in unimmunized mice had already differentiated into robust effector cells secreting high amounts of TNFα, CXCL9 and expressing inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Modulation of cell-surface adhesion molecules (ICAM-1), chemotactic receptors (CCR2, CCR5), and key antigen-presentation-associated costimulatory proteins (CD40, CD80, CD86) was also noticeable compared to primary infected mice (Figure 1A). Likewise, faster activation of neutrophils (TNFα), tissue-macrophages (CXCL9), DCs (CD86), as well as NK (CD69, IFN-γ) and NK T (IFN-γ) cells was also observed (Figure 1B, C). By 24 hrs (and later, not shown), although innate immune cell-activation was already decreasing in vaccinated mice, virtually all of these innate cell subsets underwent strong activation in primary challenged mice, consistent with previous studies (Kang et al., 2008; Serbina et al., 2003). Thus innate immune cells in vaccinated challenged mice underwent robust activation yet followed a distinct kinetics compared to that of unvaccinated mice.

Figure 1. Innate immune cells undergo robust activation during challenge infection of vaccinated hosts.

Mice (WT B6) immunized with 106 ΔActA (or in some cases 104 WT) Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) intravenously (i.v.) or left unimmunized were challenged 5 wks later with 106 WT Lm. Eight and 24 hrs later, spleens and livers (A–C) from primary or secondary (recall) challenged mice were harvested and cells stained for CD11b, Ly6C, Ly6G, F4/80, CD11c, NK1.1, NKp46, CD3 cell surface markers to define the distinct subsets of innate immune cells, and for indicated activation, adhesion/chemotactic, and effector markers. In (A), example of FACS plots and histograms staining are shown. Bar graphs average 2–3 independent replicate experiments (including ΔActA or WT Lm pooled altogether) with each dot featuring one individual mouse (n=3–11 mice). P-values are indicated with (*) p<0.1; (**) p<0.01; (***) p<0.001; (****) p<0.001; (ns) p>0.1. Error bars on graphs represent Mean+/−SD.

Spatio-temporal modifications of CD11b+ cell-trafficking and inflammation in vaccinated hosts

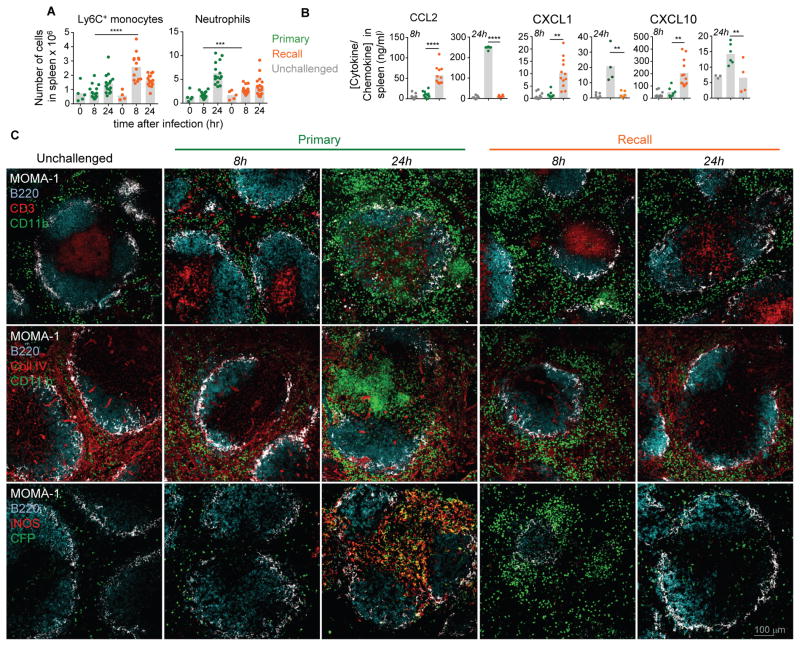

We next explored whether the robust activation of innate immune cells in vaccinated mice was also associated with enhanced recruitment from blood to infected spleens (Figure 2A and Figure S1A). Both blood phagocytes and NK cells respectively left the bone-marrow and the blood to reach infected spleens, consistent with the kinetics of activation. Levels of chemokines involved in mobilizing Ly6C+ monocytes (CCL2), neutrophils (CXCL1), NK cells (CXCL10, CXCL9), concomitantly increased in the spleen of immunized mice (Figure 2B). Thus during challenge infection, innate immune cells, both of myeloid and lymphoid origins, were rapidly recruited from blood to infected tissues and expressed a robust program of activation in vaccinated hosts only. We next wondered whether these changes were also reflected in situ through differential trafficking and spatial positioning of innate immune cells. For this, we harvested the spleen of primary and secondary challenged CCR2-CFP+/− B6 mice -which express the CFP reporter protein in all CCR2+Ly6C+ monocytes- 8 and 24 hrs after the infection, and analyzed myeloid cell recruitment and localization on tissue sections (Figure 2C). We stained for MOMA-1, B220, CD3 and collagen IV expression to discriminate red and white pulp (MOMA-1, Collagen IV) and B-T cell zones (B220, CD3). We also stained for CD11b, iNOS and CFP to identify CD11b+ cells and CCR2+ monocytes. As quantified by flow-cytometry (Figure 2A), major recruitment and clustering of CD11b+ cells (two upper rows) that included CCR2+CFP+ monocytes (lower row) were observed by 8 hrs post infection exclusively in the red pulp of vaccinated mice (Bajenoff et al., 2010). Memory T and NK cells also localized to these clusters and secretion of IFN-γ and CXCL9 was detected respectively from T-NK cells and CCR2+ monocytes (Figure S1B, not shown and (Bajenoff et al., 2010)). By 24 hrs and later (not shown), most clusters had disappeared and cells dispersed throughout the red pulp. In contrast, in primary challenged mice only by 24 hrs a massive influx of CD11b+ and CCR2+ monocytes expressing iNOS in T cell areas was observed, as previously documented (Kang et al., 2008; Serbina et al., 2003). Thus together with the distinct trafficking patterns, these results are consistent with distinct fates of Ly6C+ monocytes in primary versus secondary challenged mice.

Figure 2. Rapid recruitment, increased levels of chemokines and differential trafficking of phagocytes in the spleen of secondary challenged mice.

WT or CCR2-CFP+/− B6 mice immunized i.v. with 106 ΔActA Lm or left unimmunized were challenged 5 wks later with 106 WT Lm, and 8 and 24 hrs later spleens were harvested. In (A) cells were stained for CD11b, Ly6C and Ly6G cell surface markers to define Ly6C+ monocytes and neutrophils ; (B) levels of indicated chemokines were measured in spleen homogenates from primary, secondary challenged (recall) or unchallenged (grey dots) mice. Bar graphs average 3 independent replicate experiments with each dot featuring one individual mouse (n=5–14 mice) and p-values are indicated. In (C) spleens were stained for indicated markers and analyzed by confocal fluorescent microcopy. Spleen sections are representative of observations across 6 mice in 2 independent replicate experiments.

Distinct T cell differentiation pattern in vaccinated mice

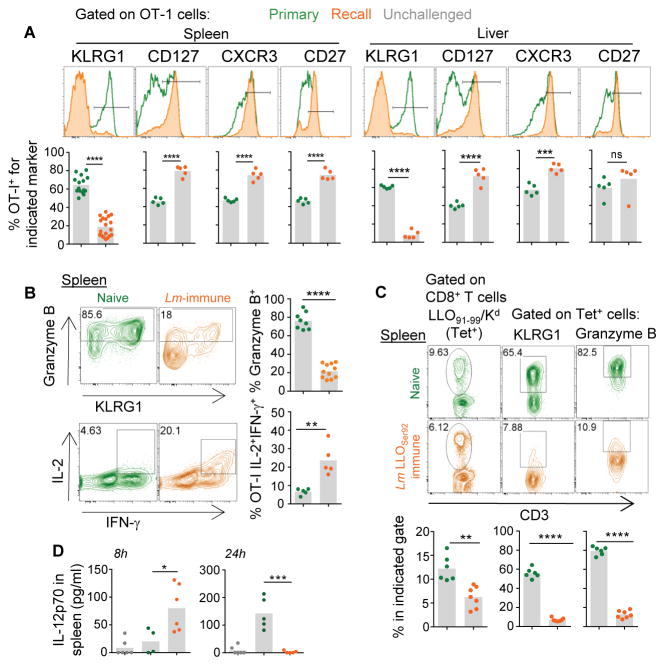

We then hypothesized that such striking differences in innate cell-trafficking and inflammation should also be reflected in the activation and the fate of pathogen-specific naïve T cells (Haring et al., 2006; Sung et al., 2012). To test this possibility, we first transferred naive OT-I CD8+ T cells that bear a TCR recognizing the ovalbumin (Ova)-derived SIINFEKL epitope presented by H2-Kb into either naive mice or mice vaccinated with WT Lm 5 wks earlier, and subsequently challenged them with Ova-expressing WT Lm (Figure S2A). Seven days later, we analyzed the phenotype of OT-I cells isolated from spleen and liver of these mice (Figure 3A, B). As expected, when OT-I cells were transferred into naïve recipient mice, they differentiated into robust effector cells (KLRG1hiCD127loCXCR3loCD27lo, granzyme Bhi). In contrast, upon transfer into Lm-immune mice, OT-I cells acquired a memory phenotype (KLRG1loCD127hiCXCR3hiCD27hi, IL-2hi, Granzyme Blo IFN-γhi). Together this reflected the important differences in the overall environment of naïve and vaccinated hosts during challenge infection. We further confirmed these results with endogenous Lm-specific CD8+ T cells using WT Kd-expressing B6 mice (B6-Kd+) immunized with Lm lacking expression of the immunodominant LLO91–99 epitope (Lm-LLOSer92) (Figure 3C and Figure S2B). These mice develop long-term immunological memory against Lm yet do not prime LLO91–99/Kd-specific (Tet+) CD8+ T cells. Five weeks later, we challenged vaccinated or control naïve mice with WT Lm and found that while endogenous LLO Tet+ CD8+ T cells differentiated into robust effector cells in non-immunized mice, they became memory-like CD8+ T cells in vaccinated mice (Figure 3C and not shown). Proliferation was lower both for LLO Tet+ (~6 versus 12%) and OT-I (not shown) T cells, likely because bacteria -and therefore antigen- were cleared faster in vaccinated mice. Interestingly, IL-12, which favors KLRG1+ effector CD8+ T cell-differentiation (Joshi et al., 2007), is only transiently produced in vaccinated compared to primary challenged mice (Figure 3D), consistent with CD8+ T cell differentiation into memory-like CD8+ T cells in vaccinated hosts. Collectively, these data highlighted the existence of major spatio-temporal and inflammatory changes during recall infection of vaccinated hosts.

Figure 3. Distinct fates of naive T cells in vaccinated and naive mice challenged with WT Lm.

(A, B) Naive Ovalbumin (Ova)-specific OT-I Tomato+ cells were transferred to either naive or Lm-immunized mice 5 wks prior and challenged with 106 ΔActA Lm-Ova the next day. After 7 d, spleen and liver were harvested and OT-I cells stained for indicated cell surface (A) and intracellular (B) markers. In (C), mice were immunized with 104 LLOser92 Lm or left unimmunized. Five wks later, mice were challenged with 106 ΔActA Lm and after 7 d, we measured the frequency of endogenous LLO91–99/Kd specific (tet+) CD8+ T cells and expression of indicated cell surface and intracellular markers. In (D) levels of bioactive IL-12 were measured in spleen homogenates from mice primary and secondary (recall) challenged with 106 WT Lm. Representative FACS histograms or plots are shown. Bar graphs average 2–3 independent replicate experiments with each dot featuring one individual mouse (n=3–11 mice) and p-values are indicated.

Memory T cells orchestrate innate cell-activation during secondary infection

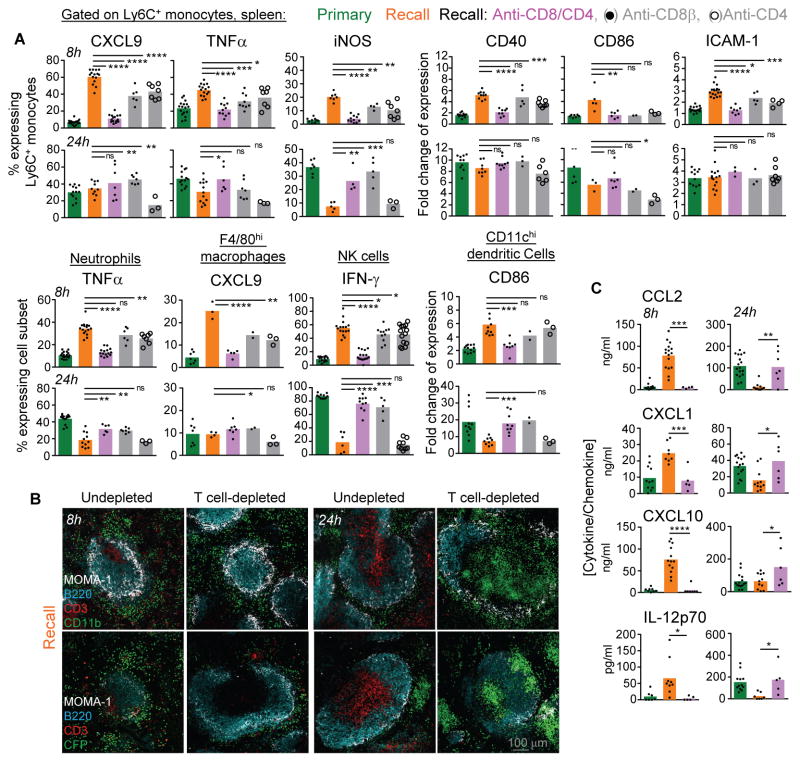

We next asked whether the changes in the innate immune response in immunized mice were accounted for by the presence of memory T cells. Vaccinated mice were treated with either CD8β, CD4 or CD8β and CD4 depleting or control isotype mAbs prior to the challenge infection, followed by measurement of innate immune cell activation, trafficking and inflammatory cytokines as read-outs (Figure 4). Depletion of either CD8+ or CD4+ T cells partially abrogated the rapid activation (8 hrs) of all innate immune cell subsets (Figure 4A). Elimination of both subsets of T cells was required to prevent the early activation of innate cells, establishing contributions of both memory CD8+ and CD4+ T cells 8 hrs post-infection. By 24 hrs however, memory CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells controlled the pattern of innate cell-activation, not only correlating with CD8+ T cell-mediated control of bacterial growth (Narni-Mancinelli et al., 2011), but also suggesting complex spatio-temporal regulations of these processes. Moreover, clustering of splenic CD11b+ cells, including CCR2+ monocytes in the marginal zone and red pulp areas, as well as rapid chemokine and cytokine release, required both subsets of T cells yet only minimal contribution of NK cells (Figure 4B, C and Figure S3A). Finally, adoptive transfer of Ly6C+ monocytes, neutrophils or NK cells into naive or vaccinated mice subsequently challenged with WT Lm, recapitulated the differential activation observed during recall infection, ruling out ‘memory-like’ cell-intrinsic features of NK cells or Ly6C+ monocytes (Figure S3B and Figures 1, 2). In summary, the robust activation and red-pulp-marginal zone positioning of CD11b+ cells during challenge infection of vaccinated hosts is mostly accounted for by pathogen-specific memory CD8+ and CD4+ T cells.

Figure 4. Memory T cell-dependent orchestration of innate immune responses.

WT B6 mice immunized with 106 ΔActA Lm i.v. or left unimmunized, were challenged 5 wks later with 106 WT Lm. In 3 of the groups, mice received CD4, CD8 or CD4/CD8 depleting mAbs prior to the challenge infection. (A) Activation status of specified cell subsets from the spleen of infected mice, defined as described in figure 1. (B) Spleen sections of primary and secondary (recall) challenged mice, depleted or not, and stained as described in figure 2C. (C) Cytokine/chemokine content in spleen from primary and secondary challenged mice either depleted or not. Bar graphs average 2–4 independent replicate experiments with each dot featuring one individual mouse (n=3–16 mice) and p-values are indicated.

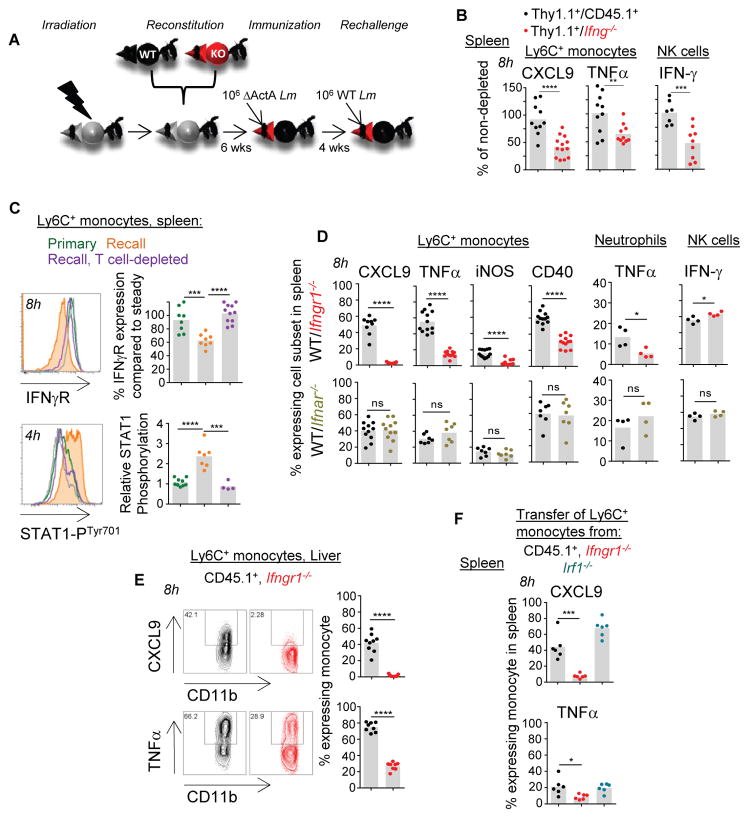

IFN-γ signals drive phagocyte and NK cell-differentiation during recall infection

Because (i) IFN-γ is largely provided by pathogen-specific memory T cells (>60% of IFN-γ+ cells) within already 4 hrs of infection in secondary challenged mice and (ii) NK cells only poorly contribute to the detectable levels of splenic IFN-γ (Figure S4A–E), we hypothesized that IFN-γ from memory T cells is the key initiator of innate immune cell activation in the Lm infection model. To formally assess this possibility, we generated Ifng−/−/Thy1.1+ and control CD45.1+/Thy1.1+ mixed bone-marrow chimeras by reconstituting lethally irradiated WT B6 mice with bone-marrow cells from either Ifng−/− or WT CD45.1+ and WT Thy1.1+ donor mice (Figure 5A). Reconstituted chimeras were immunized with attenuated ΔActA Lm, treated with Thy1.1-depleting mAb or left untreated as controls, prior to WT Lm challenge infection. We next monitored Ly6C+ monocyte, neutrophil and NK cell activation (Figure 5B and not shown). In Ifng−/−/Thy1.1+ chimeras that received anti-Thy1.1 mAb, >95% of remaining T cells could not produce IFN-γ (not shown). In this group, both Ly6C+ monocytes and NK cells exhibited impaired differentiation into CXCL9-, TNFα- and IFN-γ-producing cells respectively, establishing IFN-γ from T cells as an essential orchestrator of innate immune cell-activation. Likewise, splenic chemokine amounts in Thy1.1-depleted Ifng−/−/Thy1.1+ chimeras were significantly decreased compared to that of CD45.1+/Thy1.1+ chimeras (Figure S4F). Of note, Ifng−/− T cells were able to undergo efficient reactivation in challenged chimeras (Figure S4G). In further support that IFN-γ acts as the key T-cell derived lymphokine, Ly6C+ monocyte and neutrophil cell-surface expression of IFN-γ receptor was quickly downregulated consistent with IFN-γ-mediated triggering, and STAT1 underwent phosphorylation in both subsets of cells during challenge infection of vaccinated but not of T cell-depleted or naive mice (Figure 5C and Figure S4H). We next assessed whether IFN-γ signaling to innate immune cells indeed accounted for their activation during recall infection. For this, we generated new sets of mixed WT B6 bone marrow chimeras reconstituted with cells from IFN-γ receptor deficient (Ifngr1−/−) and WT CD45.1+ mice (Figure 5D). Both Ifngr1−/− and WT CD45.1+ myeloid cells reconstituted effectively before and after primary immunization with Lm and exhibited comparable cell-surface phenotype (not shown). We also generated mixed chimeras with bone marrow cells from IFNαβ receptor deficient (Ifnar1−/−) and WT CD45.1+ mice. Analysis of splenocytes of these mice showed that while WT cells underwent robust activation following challenge with Lm, the differentiation of Ifngr1−/− Ly6C+ monocytes and neutrophils into effector cells was prevented. In contrast, Ifnar1−/− monocytes and neutrophils behaved like WT cells, demonstrating that IFN-γ but not type I IFN signaling to these cells is the key signal. Of note, Ifngr1−/− NK cells differentiated into IFN-γ-secreting cells similarly to WT NK cells (Figure 5D). Because production of IFN-γ by NK cells was delayed in IFN-γ−/−/Thy1.1+ chimeras, this suggested that indirect but not direct IFN-γ-dependent signals were involved in enhancing NK cell activation. To test whether G-protein mediated chemotaxis may be implicated, we purified NK cells, incubated them with pertussis toxin (Ptx) -which inhibits Gαi-protein-coupled receptors- or with medium alone before adoptive transfer to naive or Lm-immunized mice subsequently challenged with WT Lm (Figure S4I). NK cell activation was impaired, consistent with the idea that IFN-γ-dependent chemotaxis may be important for NK cell localization to the red pulp/marginal zone area clusters and activation (Figure S1B). Also, activation of Ly6C+ monocytes required IFN-γ-signaling in the liver, suggesting that these mechanisms occurred outside the spleen and in other major infected organs (Figure 5E). Finally, monitoring the respective recruitment of Ifngr1−/− and WT CD45.1+ Ly6C+ monocytes, neutrophils and NK cells to the spleen and the liver, did not reveal any substantial differences early on (8 hrs), consistent with our interpretation that these cells undergo defective activation rather than recruitment (Figure S4J).

Figure 5. IFN-γ from memory T cells is a major contributor to innate immune cell activation in vaccinated mice.

(A) Experimental scheme to generate bone-marrow chimeras and immunization/challenge procedures used in (B–E). All time points post challenge infections are indicated for each experiment shown. (B) Ifng−/−/Thy1.1+ mixed bone-marrow chimera were treated or not with anti-Thy1.1 depleting mAb 1 day prior to challenge infection, and Ly6C+ monocytes and NK cells expression of indicated markers was monitored in the spleen. (C) Cell-surface expression of IFN-γ receptor and STAT1 Tyr701 phosphorylation in Ly6C+ monocytes during primary and recall infection in mice depleted of T cells or not. (D) Expression of indicated markers by WT, Ifngr1−/− or Ifnar−/− innate immune cells in the spleen of WT CD45.1+ and Ifngr1−/− or Ifnar−/− mixed bone-marrow chimera after recall infection. (E) CXCL9 and TNF-α secretion by WT and Ifngr1−/− Ly6C+ monocytes in the liver of WT CD45.1+/Ifngr1−/− mixed bone-marrow chimera after recall infection. (F) Expression of CXCL9 and TNFα by Ly6C+ monocytes adoptively transferred from the bone-marrow of WT CD45.1+ or indicated knockout mice into Lm-vaccinated WT B6 mice challenged with WT Lm. (C, E) Representative flow cytometry histograms or dot plots are shown. Bar graphs average 2–4 independent replicate experiments with each dot featuring one individual mouse (n=3–11 mice) and p-values are indicated.

In response to IFN-γ, production of IRF-1 is induced via STAT1, leading to enhanced expression of multiple IFN-γ-dependent genes (Hu and Ivashkiv, 2009). To explore whether IRF-1 was involved as a downstream effector of STAT1 in the response of innate immune effectors to IFN-γ, we adoptively co-transferred WT CD45.1+, Ifngr1−/− and Irf1−/− bone-marrow cells into Lm-vaccinated mice that we challenged with WT Lm and monitored the activation of Ly6C+ monocytes (Figure 5F and not shown). While lack of IFNγ receptor prevented their activation consistent with results from the bone marrow chimera experiments, Irf1−/− monocytes produced CXCL9, TNF-α and upregulated cell-surface CD86, CD40, ICAM-1 to comparable extent as WT monocytes, suggesting that STAT1-IRF1-independent pathways regulate expression of these molecules by Ly6C+ monocytes (Gil et al., 2001). Thus, our results collectively identified IFN-γ from memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and possibly NK cells, as a major orchestrator of an IRF-1 independent innate immune response to Lm challenge observed in vaccinated mice.

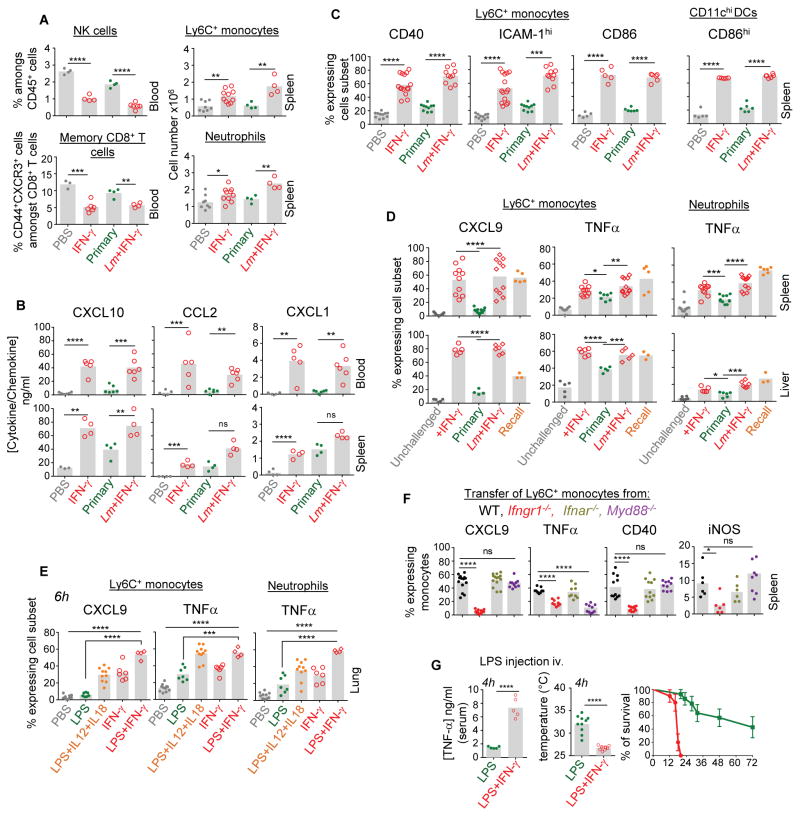

IFN-γ potentiates innate cell recruitment to tissues and activation

We next sought to define further the mechanism of IFN-γ-mediated activation of innate cells that occur during a recall infection. Innate immune cells are known to efficiently sense microbial signals (Medzhitov, 2007) and IFN-γ can also ‘prime’ these cells (Car et al., 1994; Foster et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2002; Zanetti et al., 1992). To establish the contribution of these different signals to innate cell activation, WT naïve mice were either injected with recombinant IFN-γ (rIFN-γ) or left untreated, and inoculated with or without WT Lm and innate immune cell mobilization and activation was monitored (Figure 6 and Figure S5). Treatment with rIFN-γ alone in unimmunized mice promoted rapid egress of memory phenotype (CD44hi) CD8+ T and NK cells from blood to tissues, and of Ly6C+ monocytes and neutrophils (Figure 6A and Figure S5A), which was likely accounted for by the rapid increase in the levels of CCL2, CXCL10 and CXCL1 in blood and spleen of mice that received rIFN-γ (Figure 6B). Furthermore, rIFN-γ injection resulted in CXCL9 production and CD40, CD86 and ICAM-1 upregulation by the vast majority of monocytes in spleen and liver without any microbial signals (Figure 6C, D). Interestingly, microbial signals -provided through inoculation of WT Lm- did not substantially induce any of these functions at this time point. Also, microbial signals associated to rIFN-γ did not significantly enhance expression of these functions, suggesting that IFN-γ alone is sufficient to mediate recruitment of leucocytes to tissues, increase chemokine levels and expression of sets of costimulatory and adhesion molecules by myeloid cells (Figure 6A–D). Of note, expression levels of these markers were equivalent to those measured in control vaccinated mice challenged with WT Lm. In contrast, secretion of TNF-α by monocytes and neutrophils was induced by IFN-γ or by microbial signals (Figure 6D). Interestingly, secretion of TNFα was further potentiated by rIFN-γ treatment in spleen and liver compared to that seen in mice primary infected with Lm. Of note, levels of TNF-α produced in secondary challenged control mice were either superior or similar to that of IFN-γ-treated groups. To extend these observations to a peripheral mucosal tissue, we inoculated WT mice intranasally with LPS, a robust microbial signal from Gram− bacteria, with or without rIFN-γ (Figure 6E, Figure S5B and not shown). As observed in spleen and liver, IFN-γ alone was a potent inducer of CXCL9 release by Ly6C+ monocytes and upregulation of CD86 and CD40 in the lung, yet microbial signals alone did not promote production of CXCL9. In line with these results, inoculation of rIL-12 and rIL-18 which induce the rapid release of IFN-γ by NK and memory CD8+ T cells (Berg et al., 2003; Kupz et al., 2012; Soudja et al., 2012), potentiated the effect of LPS (Figure 6E). As for the other organs, secretion of TNF-α by phagocytes was maximized in presence of IFN-γ.

Figure 6. Recombinant IFN-γ promotes rapid phagocyte activation in tissues and potentiate microbial signals.

(A–C) Naïve WT B6 mice were injected i.v. either with WT Lm (106) or PBS, and 4 hrs later with recombinant IFN-γ (15,000UI). Control groups included primary and (D) secondary (recall) challenged mice. Blood or organs were harvested 8 hrs after the start of the experiment and cell suspensions stained for indicated cell surface or intracellular markers. (A) Blood or spleen cells were stained with cell-surface CD8, NKp46, Ly6C, CD11b, Ly6G to define indicated cell subsets. (B) Levels of indicated cytokines and chemokines were measured in blood and spleen homogenates. (C) Cell surface expression of CD86, CD40 and ICAM-1 on spleen Ly6C+ monocytes and CD11chi DCs. (D) CXCL9 and TNF-α secretion by Ly6C+ monocytes and neutrophils extracted from spleen and liver with (TNF-α) or without (CXCL9) heat-killed Lm restimulation. (E) Naïve WT B6 mice were treated intranasally with PBS with or without combinations of LPS (500ng), recombinant IL-12 (1ng) and IL-18 (100ng) or rIFN-γ (5,000UI), and CXCL9 and TNF-α secretion from Ly6C+ monocytes and neutrophils from the lung was measured after in vitro restimulation. (F) Expression of CXCL9, TNF-α, iNOS and CD40 by Ly6C+ monocytes adoptively transferred from the bone-marrow of WT CD45.1+ or indicated knockout mice into Lm-vaccinated WT B6 mice challenged with WT Lm. (G) Naïve WT B6 mice were injected i.v. with recombinant IFN-γ (15,000 UI) or not, and 30 min later with LPS (100μg). TNF-α serum levels, mouse body temperature in the 2 experimental groups 4 hrs post-treatment and kinetics of mice survival are shown. Bar graphs average 2–3 independent replicate experiments with each dot featuring one individual mouse (n=3–10 mice) and p-values are indicated. Error bars on graphs represent Mean+/−SD.

To dissociate the importance of IFN-γ versus microbial signals during recall infection, we performed adoptive transfers of bone-marrow cells from mice lacking two major pathways involved in early microbial response, from Ifnar−/− and Myd88−/−, and WT and Ifngr1−/− mice as controls, into Lm-vaccinated recipient mice. We found that MyD88-dependent microbial signals indeed regulated the ability of monocytes to secrete TNF-α, but not CXCL9 or iNOS expression and cell-surface CD40 (Figure 6F), consistent with a most essential activating function of IFN-γ during the secondary infection.

IFN-γ can ‘prime’ innate immune cells, a process also described as the Shwartzman lethal reaction (Ozmen et al., 1994) in which mice treated with LPS or IFN-γ that receive a second injection of LPS 24 hrs later undergo rapid inflammatory cytokine-mediated death (TNF-α, IL-1)(Car et al., 1994; Zanetti et al., 1992). To assess whether such observations could be extended to the robust potentiating effect of IFN-γ that we have observed during concomitant microbial triggering, we injected mice with high doses of LPS as a model of sepsis together with rIFN-γ or with saline. Mice co-administered with LPS and IFN-γ underwent dramatic reduction of body temperature, exhibited high serum levels of TNF-α and died significantly faster compared to those that only received LPS (Figure 6G). Thus, as hypothesized, IFN-γ can synergize with microbial stimulation. In summary, IFN-γ acts as a powerful switch and potentiating cytokine of innate immune cell recruitment, costimulatory and adhesion molecules, and of danger sensing pathways leading to proinflammatory molecule production, overall regulating cellular immune responses.

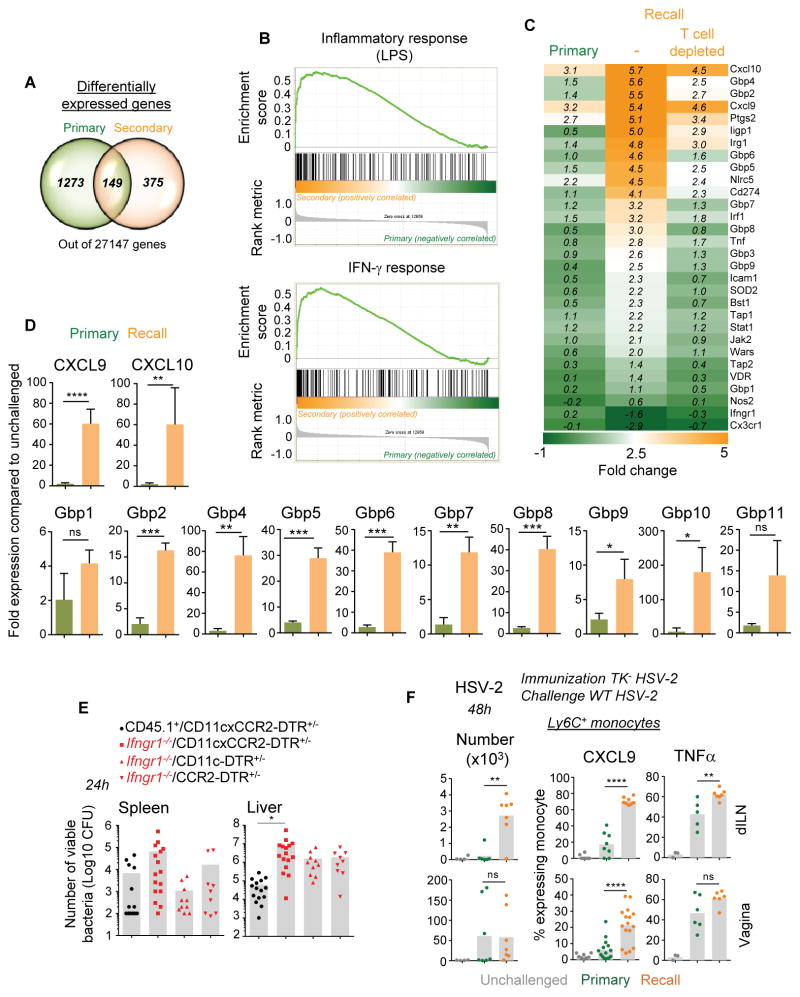

IFN-γ-dependent antimicrobial genetic signature in monocytes from vaccinated mice

To achieve a more global understanding of the impact of IFN-γ signaling on innate immune cell activation and differentiation during the recall infection, we carried out analyses at the whole genome transcript level. We focused on Ly6C+ monocytes, given their importance in activating memory cells and as robust effector cells (Shi and Pamer, 2011; Soudja et al., 2012) and performed whole genome expression arrays of purified Ly6C+ monocytes from naive or vaccinated mice challenged with WT Lm (Figure 7). Interestingly, the number of genes differentially expressed compared to unchallenged mice was more restricted in vaccinated than in primary infected mice (factor of ~3)(Figure S6A) and only 149 genes were found to overlap between the two groups (Figure 7A). Gene ontology (GO) pathway analysis highlighted strong cellular responses to IFN-γ and immune-defense related signatures in vaccinated mice while a more general inflammatory yet less focused signature was observed in non-vaccinated mice (Figure S6B). We next compared the expression of LPS and IFN-γ target genes established in macrophages (Broad Institute (Subramanian et al., 2005)) between naïve and vaccinated mice after Lm challenge infection, using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)(Figure 7B). Overall, inflammatory and IFN-γ-dependent genes were upregulated in vaccinated mice and these included known IFN-γ-induced genes. Amongst these were functional markers that were also highlighted in our prior analyses (Figures 1, 5) such as the chemokines CXCL9, TNF-α, ICAM-1, NOS2 (Figure 7C). Most importantly, this analysis revealed a whole set of genes encoding the guanylate binding proteins (Gbp), Gbp1-11, that belong to the IFN-γ-inducible GTPases superfamily and were recently implicated in cell-autonomous host defense against intracellular bacteria through the activation of the phagocyte oxidase, antimicrobial peptides and autophagy effectors (Kim et al., 2011; Yamamoto et al., 2012). Upregulation of all described gbp mRNAs was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR on purified Ly6C+ monocytes from primary or secondary challenged mice (Figure 7D). Thus, these data from whole genome expression arrays of Ly6C+ monocytes are consistent with a global memory T cell- and IFN-γ-dependent polarization of innate immune defenses during infection of protected mice.

Figure 7. IFN-γ signaling induces strong antimicrobial gene signature in Ly6C+ monocytes from vaccinated mice and promotes CD11c+ and CCR2+ cell- -mediated protective immunity.

(A–D) Aged-matched CCR2-CFP+/− B6 females immunized with WT Lm (104) or left unimmunized, were challenged with WT Lm (106) 5 wks later. After 8 hrs Ly6C+ monocytes from spleen were flow-sorted based on CD11b, Ly6C and CFP expression. All expression arrays/RT-qPCR data shown are in Ly6C+CFP+ monocytes. (A) Venn diagrams comparing the numbers of differentially and commonly expressed genes in monocytes from primary versus secondary challenged mice (with adjusted p-value<0.05). (B) GSEA plot comparing gene expression arrays related to LPS-induced inflammation and IFN-γ stimulation in monocytes/macrophages in monocytes from primary versus secondary challenged mice. (C) Heat maps of IFN-γ related genes in monocytes from primary and secondary challenged mice either depleted of T cells or left undepleted prior to challenge, compared to that of unchallenged mice. Each experimental gene array condition had 3 mice/group and monocyte purifications were performed as 3 independent experimental replicates with 1 mouse/group for each condition tested. (D) Relative expression of indicated guanylate binding protein (Gbp) genes in monocytes from primary versus secondary challenged WT B6 mice (n=3). This experiment was performed independently on a group of mice different from the microarray analysis and p-values are indicated. (E) Indicated mixed bone-marrow chimera reconstituted with WT CD45.1+ or Ifngr1−/− and CD11c-DTR+/−xCCR2-DTR+/−, CD11c-DTR+/− or CCR2-DTR+/− were immunized with ΔActA Lm (106). Five wks later, mice were challenged with WT Lm 12 hrs post DT treatment. Bacterial titers were determined in spleen and liver after 24 hrs. (F) Ly6C+ monocyte recruitment and activation (CXCL9, TNF-α) at 48 hrs in the vagina and draining iliac lymph nodes (dILN) of WT mice immunized with attenuated TK− HSV-2 (recall) or left unimmunized (primary) and challenged with WT HSV-2 4 wks later. All graphs average 2–3 independent replicate experiments with each dot featuring one individual mouse (n=4–12 mice) and p-values are indicated. Error bars on graphs represent Mean+/−SD.

Essential role of IFN-γ signaling to dendritic cells and monocyte or macrophages for effective host protection

Because our findings highlighted the role of IFN-γ as a major initiator of antimicrobial innate immune responses in vaccinated mice, we next examined whether IFN-γ signaling to innate myeloid cells was a critical element of protection during infection of vaccinated hosts. We generated mixed bone marrow chimeras in WT B6 recipient mice reconstituted with bone marrow cells from Ifngr1−/− and transgenic mice expressing the diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) selectively in CCR2+, CD11c+ or both cell subsets. This creates mice in which DTR-expressing cells can be rapidly and selectively depleted upon diphtheria toxin (DT) injection (Figure 7E). As a control group, mice were reconstituted with CD45.1+ and CD11c-DTR+/−xCCR2-DTR+/− bone-marrow cells. We immunized all groups with ΔActA Lm-Ova and five to six weeks later, the mice were challenged with 106 WT Lm-Ova 12 hrs post-DT treatment. Mice were sacrificed 24 hrs post challenge infection, and bacterial titers were determined in spleen and liver. Mice left with only Ifngr1−/− DCs, Ly6C+ monocytes and red pulp macrophages exhibited substantially increased Lm burden both in spleen and liver by a factor of ~11 and ~150 respectively, formally demonstrating the importance of IFN-γ for effective protection of vaccinated hosts through its effect on monocytes, DCs and macrophages. Selective elimination of either monocytes (CCR2-DTR+/−) or DCs and red pulp macrophages (CD11c-DTR+/−) led to partial loss of protection in liver (~by a factor of 10 in both cases), relative to the loss of protection observed upon depletion of all of these cell subsets. In the spleen however, monocytes accounted for nearly the entire IFN-γ-dependent protective effect while increased protection (and lower CFUs) was observed when DCs were depleted (by a factor of ~7), possibly because Lm access to the spleen was impaired in the absence of DCs (Edelson et al., 2011; Neuenhahn et al., 2006). Since IFN-γ represents a key lymphokine involved in host protection during primary infection (Harty and Bevan, 1995; Lee et al., 2013), we wondered whether our results could not just be accounted for by the lack of IFN-γ signaling to DC, macrophages and Ly6C+ monocytes in the chimera mice. We assessed this possibility by challenging non-vaccinated Ifngr1−/− and WT mice and measured bacterial titers in spleen and liver 24 hrs later (Figure S6C). We only found small differences in viable bacteria in both organs (factor of ~1.5–3.5), suggesting that, in contrast to recall infection in which substantial differences in bacterial CFUs were measured (factor of ~10–150, Figure 7E), IFNγ signaling during primary infection does not account for substantial protection defects at such early times after the infection. Thus, IFN-γ-signaling to innate immune cells, including both CCR2+ monocytes and CD11c+ DCs and macrophages, represents an important mechanism of protection of vaccinated hosts during challenge infection with virulent bacteria.

As an initial approach to extending this rapid IFN-γ-mediated activation of innate phagocytes to a relevant model of mucosal infection in which IFN-γ from T cells is known to be required for protection of vaccinated hosts (Gebhardt et al., 2009; Iijima et al., 2008), we immunized mice intravaginally with an attenuated strain of herpes simplex virus (TK− HSV2) that induces long-term memory T cell-mediated immunity. Five weeks later, we challenged these mice or unimmunized control mice with WT HSV2 and monitored Ly6C+ monocyte activation in draining LNs and vaginal mucosa (Figure 7F). As hypothesized, and similarly to the Lm model, Ly6C+ monocytes underwent robust recruitment and differentiation into CXCL9- and TNF-α-secreting effector cells in vaccinated mice. Taken together, our results support a model in which an important mechanism of protection of vaccinated hosts requires mobilization and activation via IFN-γ of various subsets of innate immune effector cells like Ly6C+ monocytes.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have provided an extensive analysis of innate immune responses during infection of previously immunized hosts, demonstrating that IFN-γ secreted by memory T cells acts as a signal to many important subsets of innate myeloid cells. Our findings highlight the key contribution of Ly6C+ monocytes, DCs and tissue macrophages to the rapid and efficient protective responses observed in vaccinated hosts. Our study is unique, to the best of our knowledge, in its systematic investigation of how memory T cell-derived IFN-γ mediates its effects in vivo using relevant models of infections. We established that the potent effects of IFN-γ from memory T cells were achieved through multiple mechanisms, including recruitment, activation and potentiation of innate cell effector functions.

We have previously shown that memory CD8+ T cells undergo early reactivation and differentiation into robust IFN-γ-secreting effector cells independent of cognate antigen recognition and in response to inflammatory cytokines (IL-18, IL-12) largely provided by activated inflammatory Ly6C+ monocytes (Soudja et al., 2012). Our results further highlight that early IFN-γ produced by memory T cells is a critical link promoting the rapid activation of myeloid lineage and NK cell effectors, and subsequent recruitment of a range of antimicrobial factors essential for protection of vaccinated hosts. While initiation of memory T cell differentiation is independent of cognate antigen, and contributes to some level of pathogen killing, antigen recognition is required for full protection of the host. In particular, recognition of cognate antigen by memory T cells is essential for stabilization of APC and memory T cell-interactions in situ (Kastenmuller et al., 2013; Kastenmuller et al., 2012). The formation of transient clusters of memory T cells, monocytes and neutrophils observed in the red pulp or marginal zone area of infected spleens strongly correlates with efficient control of pathogen growth, likely preventing its spreading to white pulp areas (Bajenoff et al., 2010; Soudja et al., 2012). Complex inflammatory and antigen-dependent mechanisms involving cross-talk between memory T cells and innate immune cells are clearly required to sustain optimal memory responses over time. The massive recruitment of memory and NK lymphocytes, and of monocytes and neutrophils that occurs from the blood of vaccinated mice to infected tissues requires multiple chemotactic and adhesion processes with high levels of redundancy. Our observations support a model in which the rapid activation of memory T and NK cells by CCR2+ monocytes induces the initial wave of IFN-γ that in turn promotes secretion of CCL2, CXCL1, CXCL9, CXCL10 chemokines, to further recruit additional CXCR3+ memory and NK lymphocytes and potentiate IFN-γ-dependent responses. This is consistent with elegant dynamic studies of infected lymph nodes (LNs) showing memory CD8+ T cells congregating near the peripheral entry portal of lymph-borne bacterial and viral pathogens (Kastenmuller et al., 2013; Kastenmuller et al., 2012; Sung et al., 2012) via a CXCL9-CXCR3-mediated mechanism, ultimately leading to the containment of infectious pathogens (Kastenmuller et al., 2013; Kastenmuller et al., 2012; Sung et al., 2012). During primary infection of mice with Lm or Toxoplasma gondii, NK cells were also proposed as major orchestrators of blood phagocyte recruitment and activation, yet memory T cells substituted for this role during infection of vaccinated mice, using equivalent IFN-γ-dependent mechanisms (Goldszmid et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2008). In this way, memory T cells play an important role in rapidly containing the spreading and enhancing the killing of pathogens.

Our results underline a remarkable IFN-γ-dependent skewing of the differentiation of all subsets of innate cells that occurs during infection of vaccinated mice. Chemotaxis, secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, antigen presentation and costimulation, microbicidal functions and effector molecule expression are strongly induced by IFN-γ both directly (myeloid cells) and indirectly (NK, NK T cells). Even though IFN-γ exhibits a variety of immunomodulatory roles, whether IFN-γ is essential for host protection often remains dependent on the pathogen. In the case of Lm, immunized mice develop long-term memory CD8+ T cell-dependent protection, and selective depletion of this subset of T cells abrogates protective immune responses against a recall infection with virulent WT Lm. While our results establish a clear effect of IFN-γ from memory T cells on protective recall responses against Lm, this effect remains partial in particular in the spleen of these mice, with slightly more than a log bacteria CFUs, compared to the usual 2–3 logs observed in fully protected mice (Neighbors et al., 2001). One possible explanation is that neutrophils, which are still present in DT-treated CD11c-CCR2 DTR+-Ifngr1−/− chimera, are secreting high levels of TNF-α in response to IFN-γ and TNF-α is known to be absolutely required for protective memory responses (Narni-Mancinelli et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2001). Another explanation to this result may be that WT tissue-resident macrophages from irradiated recipient mice, which are known to phagocyte intravenously injected Lm, are still present by 2–3 months post-irradiation (~50% (Hashimoto et al., 2013)) and undergo potent antimicrobial activation in response to IFNγ. Moreover, the subset of innate cell that is most important may vary depending on the infected tissue as suggested by our data comparing infected spleen and liver.

In the case of HSV2 infection, IFN-γ from memory CD4+ T cells seems essential for protective responses in vaccinated mice by initiating the rapid secretion of local CXCL9 and CXCL10 (Iijima et al., 2008; Nakanishi et al., 2009) which further promote CXCR3-mediated accumulation of IFN-γ-secreting memory T cells from blood. Altogether, this is consistent with our observation that IFN-γ acts as a positive forward signal inducing chemokine secretion (CCL2, CXCL10, CXCL1), blood phagocyte recruitment and subsequent activation via CXCL9 and TNF-α. Along these lines, tissue-resident memory T cells were indeed proposed to function as ‘sentinels’ of the immune system localized at the portal of pathogen entry that can provide rapid host protection, also via IFN-γ (Gebhardt et al., 2009; Schenkel et al., 2013). Alternatively, our experiments using rIFN-γ in a model of sepsis, also illustrate the in vivo potency of IFN-γ signals and underline their important potential negative outcomes.

In summary, this study reveals the importance of cross-talk between memory T cells and innate immune effector cells in vivo during the early phase of infection. Our findings open new potential therapeutic strategies to intervene to the benefit of the host, by harnessing or blocking a specific pathway in a specific cell type.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

Mice were bred in our SPF animal facility. In brief, we used wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J (B6) 6–8 wk-old mice, congenic CD45.1+ and Thy1.1+ B6, and transgenic B6 mice Rosa26-Actin-tomato-stoploxP/loxP-GFP, Td+, OT-I Rag1−/−, Rag1−/−, B6-Kd, CCR2-DTR-CFP+/−, CD11c-DTR+/−, Ifngr1−/−, Ifnar−/−, Irf1−/−, Ifng−/−, most from Jackson labs (See Supplemental information for further details).

Microbial pathogens, mice infections and measure of protective immunity

We used WT and ΔActA Lm and Lm-Ova (strain 10403s), expressing the ovalbumin (Ova) model antigen and WT LLOSer92 Lm. For infections, bacteria were grown to a logarithmic phase in broth heart infusion medium, diluted in PBS to infecting concentration and injected i.v. In all experiments, mice were primary immunized with 0.1×LD50 ΔActA (106) or WT Lm, Lm-OVA, LLOSer92 Lm (104). Secondary challenge infections were performed 4–6 wks later with 106 WT Lm or Lm-Ova unless otherwise specified. In most bone-marrow chimera experiments, we used ΔActA Lm for primary immunizations. For bacterial titers, organs were dissociated in 0.1% triton X-100 and plated onto BHI platesto count CFU numbers 24 hrs later.

Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

Female mice treated with 2 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate subcutaneously (s.c.) were immunized or not 5 d later intravaginally with 2×105 plaque forming units (PFU) of 186ΔKpn HSV-2 (TK− HSV-2). 5–6 wks later, mice were infected with 105 WT HSV-2 strain 186, and organs harvested 2 d later.

Preparation of cell suspensions for flow cytometry (FACS) and adoptive transfers

Spleens or iliac lymph nodes were dissociated on nylon mesh, lungs were cut ; organs were incubated in HBSS medium with 4,000 U/ml collagenase I and 0.1 mg/ml DNase I, and red blood cells (RBC) lysed with NH4Cl buffer (0.83% vol/vol). For lungs and livers, mice were perfused with PBS 0.5 μg/ml brefeldin A, filtered and centrifuged on a percoll gradient 67%/44%. Vaginas were cut in small pieces, digested with a cocktail of enzymes with Golgi plug/STOP in HBSS 10% FCS. Blood was harvested into heparin tubes and RBC lysed.

Measure of splenic cytokine and chemokine content

Frozen spleens were thawed in 150 μl of lysis buffer (150mM NaCl, 40mM Tris pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors, homogenized with a douncer, and supernatants were centrifuged before dosing using FACS-based bead assays.

Cell-staining for FACS analysis

Cell suspensions were incubated with 2.4G2 and stained with specified antibodies cocktail (Table S1) in PBS 1%FCS, 2mM EDTA, 0.02% sodium azide. For intracellular staining (ICS), cells were incubated 3–4 hrs 37°C, 5%CO2 in RPMI1640 5%FCS, Golgi Plug, fixed in IC fixation buffer, and permeabilized and stained 30 min against indicated intracellular markers.

Purification of Ly6C+ monocytes for microarray analysis or RT quantitative PCR

Spleen cells from challenged CCR2-CFP+/− B6 mice were enriched by positive selection of cells expressing CD11b and flow-sorted (Aria III) based on CFP+ lin− cells (NK1.1−Ly6G−B220−CD3−). 10,000 cells were collected into 150 μl lysis buffer.

Microarrays and quantitative RT-PCR

Microarrays

RNA from purified Ly6C+ monocytes was extracted using the RNAqueous Micro kit (Ambion) and amplified using the WT Ovation Pico System (Nugen). RNA quality score and quantity was assessed with a Bioanalyzer 2100 Nano Chip before hybridization to Affymetrix Mouse Gene ST 1.0 arrays.

Quantitative RT-qPCR analysis

cDNA was synthesized from extracted RNA with SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR green PCR Master Mix. Primer sequences are given in Table S2.

NK and bone-marrow cell transfers

Bone marrow cells were labeled with different amount of CFSE (10μM or 1μM) and 2–4×106 CFSEhi and CFSElo cells were co-transferred into unimmunized or Lm-immunized WT B6 mice 30 min after challenge with 106 WT Lm.

NK cell transfers

Spleen cells from Rag1−/− were negatively enriched (Ly6G−, Ter119−, I-A/E− cells) and 0.5–1×106 NK cells were adoptively transferred to recipient mice.

Cell subset depletion

CCR2+ and CD11c+ cells were depleted from Diphtheria Toxin Receptor (DTR) expressing mice using 10ng/g/mice of Diphtheria Toxin (DT) 12 hrs prior infection. CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were depleted by injecting i.v. 150 μg of purified anti-CD8β (H35) and/or anti-CD4 (GK1.5) 1 d before infection. For Thy1.1+ or NK cell-depletion, we used respectively 250 μg of purified anti-Thy1.1 mAb (19E12) or PK136 ascites injected i.p. 2 d before infection.

Generation of bone-marrow chimera mice

Lethally irradiated WT B6 mice (1,200 rads) were immediately reconstituted with 2×106 bone marrow cells isolated from indicated donor mice. Ifng−/−/Thy1.1+ and CD45.1+/Thy1.1+ were reconstituted at a 7:3 ratio ; Ifngr1−/− or Ifnar−/− and CD45.1+ received a 1:1 ratio ; Ifngr1−/− and CCR2-DTR+/− or CD11c-DTR+/− or both DTR+ received a 7:3 ratio. Expected chimerism of reconstituted mice was checked 6–8 weeks later.

Immunostaining for confocal microscopy analysis

Frozen spleen sections were fixed in acetone and stained with indicated antibodies. Images were taken on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope and processed using Adobe Photoshop software.

Statistics

Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired Student t test with GraphPad Prism software and two-tailed P values are given as: (*) P<0.1; (**) P<0.01; and (***) P<0.001; (ns) P>0.1. All p values of 0.05 or less were considered significant and are referred to as such in the text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

H2-Kd/LLO91–99 tetramers came from the NIH Tetramer Facility. We are grateful to M. Levy (AECOM) for privileged access to the FACS Aria III and thank the AECOM FACS and genomic core facilities. We thank S. Porcelli (AECOM), J. Daily (AECOM) and laboratory members L. Chorro and E. Spaulding for critical comments. Supported by the National Institute of Health (Grants AI095835, AI103338 and Einstein DRC pilot to GL ; AI099567 to DP ; GM007288 to E.Y.). Core resources for FACS were supported by the Einstein Cancer Center (NCI cancer center support grant 2P30CA013330).

Footnotes

Detailed and all additional methods can be found in Supplemental information.

Authors Contributions

S.M.S. and G.L. designed experiments and interpreted the data; S.M.S. did and analyzed all experiments; C.C. and M.V. contributed experiments; E.Y. and D.P. contributed HSV2-related reagents, expertise and data interpretation; G.L. led the research program and with input from S.M.S. wrote the manuscript. E.Y. and D.P. contributed to critical comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bajenoff M, Narni-Mancinelli E, Brau F, Lauvau G. Visualizing early splenic memory CD8+ T cells reactivation against intracellular bacteria in the mouse. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RE, Crossley E, Murray S, Forman J. Memory CD8+ T cells provide innate immune protection against Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of cognate antigen. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1583–1593. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billiau A, Matthys P. Interferon-gamma: a historical perspective. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Car BD, Eng VM, Schnyder B, Ozmen L, Huang S, Gallay P, Heumann D, Aguet M, Ryffel B. Interferon gamma receptor deficient mice are resistant to endotoxic shock. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1437–1444. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelson BT, Bradstreet TR, Hildner K, Carrero JA, Frederick KE, Kc W, Belizaire R, Aoshi T, Schreiber RD, Miller MJ, et al. CD8alpha(+) Dendritic Cells Are an Obligate Cellular Entry Point for Productive Infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Immunity. 2011;35:236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster SL, Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature. 2007;447:972–978. doi: 10.1038/nature05836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt T, Wakim LM, Eidsmo L, Reading PC, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:524–530. doi: 10.1038/ni.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil MP, Bohn E, O’Guin AK, Ramana CV, Levine B, Stark GR, Virgin HW, Schreiber RD. Biologic consequences of Stat1-independent IFN signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6680–6685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111163898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldszmid RS, Caspar P, Rivollier A, White S, Dzutsev A, Hieny S, Kelsall B, Trinchieri G, Sher A. NK cell-derived interferon-gamma orchestrates cellular dynamics and the differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells at the site of infection. Immunity. 2012;36:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haring JS, Badovinac VP, Harty JT. Inflaming the CD8+ T cell response. Immunity. 2006;25:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harty JT, Bevan MJ. Specific immunity to Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of IFN gamma. Immunity. 1995;3:109–117. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P, Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, Becker CD, See P, Price J, Lucas D, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Herrero C, Li WP, Antoniv TT, Falck-Pedersen E, Koch AE, Woods JM, Haines GK, Ivashkiv LB. Sensitization of IFN-gamma Jak-STAT signaling during macrophage activation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:859–866. doi: 10.1038/ni828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Ivashkiv LB. Cross-regulation of signaling pathways by interferon-gamma: implications for immune responses and autoimmune diseases. Immunity. 2009;31:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima N, Linehan MM, Zamora M, Butkus D, Dunn R, Kehry MR, Laufer TM, Iwasaki A. Dendritic cells and B cells maximize mucosal Th1 memory response to herpes simplex virus. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3041–3052. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SJ, Liang HE, Reizis B, Locksley RM. Regulation of hierarchical clustering and activation of innate immune cells by dendritic cells. Immunity. 2008;29:819–833. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenmuller W, Brandes M, Wang Z, Herz J, Egen JG, Germain RN. Peripheral Prepositioning and Local CXCL9 Chemokine-Mediated Guidance Orchestrate Rapid Memory CD8(+) T Cell Responses in the Lymph Node. Immunity. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenmuller W, Torabi-Parizi P, Subramanian N, Lammermann T, Germain RN. A spatially-organized multicellular innate immune response in lymph nodes limits systemic pathogen spread. Cell. 2012;150:1235–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BH, Shenoy AR, Kumar P, Das R, Tiwari S, MacMicking JD. A family of IFN-gamma-inducible 65-kD GTPases protects against bacterial infection. Science. 2011;332:717–721. doi: 10.1126/science.1201711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupz A, Guarda G, Gebhardt T, Sander LE, Short KR, Diavatopoulos DA, Wijburg OL, Cao H, Waithman JC, Chen W, et al. NLRC4 inflammasomes in dendritic cells regulate noncognate effector function by memory CD8(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ni.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Carrero JA, Uppaluri R, White JM, Archambault JM, Lai KS, Chan SR, Sheehan KC, Unanue ER, Schreiber RD. Identifying the initiating events of anti-Listeria responses using mice with conditional loss of IFN-gamma receptor subunit 1 (IFNGR1) J Immunol. 2013;191:4223–4234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449:819–826. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi Y, Lu B, Gerard C, Iwasaki A. CD8(+) T lymphocyte mobilization to virus-infected tissue requires CD4(+) T-cell help. Nature. 2009;462:510–513. doi: 10.1038/nature08511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narni-Mancinelli E, Campisi L, Bassand D, Cazareth J, Gounon P, Glaichenhaus N, Lauvau G. Memory CD8+ T cells mediate antibacterial immunity via CCL3 activation of TNF/ROI+ phagocytes. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2075–2087. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narni-Mancinelli E, Soudja SM, Crozat K, Dalod M, Gounon P, Geissmann F, Lauvau G. Inflammatory Monocytes and Neutrophils Are Licensed to Kill During Memory Responses In Vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2011:29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors M, Xu X, Barrat FJ, Ruuls SR, Churakova T, Debets R, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA, Abrams JS, O’Garra A. A critical role for interleukin 18 in primary and memory effector responses to Listeria monocytogenes that extends beyond its effects on Interferon gamma production. J Exp Med. 2001;194:343–354. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.3.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuenhahn M, Kerksiek KM, Nauerth M, Suhre MH, Schiemann M, Gebhardt FE, Stemberger C, Panthel K, Schroder S, Chakraborty T, et al. CD8alpha+ dendritic cells are required for efficient entry of Listeria monocytogenes into the spleen. Immunity. 2006;25:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozmen L, Pericin M, Hakimi J, Chizzonite RA, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Gately M, Garotta G. Interleukin 12, interferon gamma, and tumor necrosis factor alpha are the key cytokines of the generalized Shwartzman reaction. J Exp Med. 1994;180:907–915. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue HP, Beadling C, Haun J, Slifka MK. Cytokine-mediated programmed proliferation of virus-specific CD8(+) memory T cells. Immunity. 2013;38:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 2010;33:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Vezys V, Masopust D. Sensing and alarm function of resident memory CD8(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:509–513. doi: 10.1038/ni.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbina NV, Salazar-Mather TP, Biron CA, Kuziel WA, Pamer EG. TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells mediate innate immune defense against bacterial infection. Immunity. 2003;19:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soudja SM, Ruiz AL, Marie JC, Lauvau G. Inflammatory Monocytes Activate Memory CD8(+) T and Innate NK Lymphocytes Independent of Cognate Antigen during Microbial Pathogen Invasion. Immunity. 2012;37:549–562. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt TM, McKinstry KK, Dibble JP, Winchell C, Kuang Y, Curtis JD, Huston G, Dutton RW, Swain SL. Memory CD4+ T cells induce innate responses independently of pathogen. Nat Med. 2010;16:558–564. 551. doi: 10.1038/nm.2142. following 564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung JH, Zhang H, Moseman EA, Alvarez D, Iannacone M, Henrickson SE, de la Torre JC, Groom JR, Luster AD, von Andrian UH. Chemokine guidance of central memory T cells is critical for antiviral recall responses in lymph nodes. Cell. 2012;150:1249–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MA, Bevan MJ. Effector and memory CTL differentiation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:171–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Okuyama M, Ma JS, Kimura T, Kamiyama N, Saiga H, Ohshima J, Sasai M, Kayama H, Okamoto T, et al. A cluster of interferon-gamma-inducible p65 GTPases plays a critical role in host defense against Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity. 2012;37:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti G, Heumann D, Gerain J, Kohler J, Abbet P, Barras C, Lucas R, Glauser MP, Baumgartner JD. Cytokine production after intravenous or peritoneal gram-negative bacterial challenge in mice. Comparative protective efficacy of antibodies to tumor necrosis factor-alpha and to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1992;148:1890–1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SY, Boisson-Dupuis S, Chapgier A, Yang K, Bustamante J, Puel A, Picard C, Abel L, Jouanguy E, Casanova JL. Inborn errors of interferon (IFN)-mediated immunity in humans: insights into the respective roles of IFN-alpha/beta, IFN-gamma, and IFN-lambda in host defense. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:29–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.