Abstract

Toward identifying variables that may protect children against sleep problems otherwise associated with ethnic minority status and economic adversity, support coping was examined as a moderator. Participants were 235 children (113 boys, 122 girls; M age = 11.33 years, SD =8.03 months); 64% European American and 36% African American. Children’s sleep duration (minutes) and continuity (efficiency) were assessed through actigraphs worn for one week. Mothers reported on the family’s monetary resources (income-to-needs ratio) and children reported on their support coping strategies. For children from lower income homes and African Americans, a higher level of support coping was a protective factor against fewer sleep minutes and reduced sleep efficiency, otherwise associated with economic adversity. Children from more economically advantaged homes had good sleep parameters regardless of their coping. The results build on the existing small body of work by demonstrating that children’s support coping strategies have a protective role against sleep problems otherwise associated with ethnic minority status and economic adversity and present potential targets for intervention that may help reduce health disparities in an important health domain.

Keywords: sleep, children, health disparity, African American, coping

Sleep duration and continuity are associated with multiple health domains including obesity and risk for cardiometabolic disease (Chen, Beydoun, & Wang, 2008; Knutson, 2012), as well as with cognitive and behavioral functioning (Sadeh, 2007). Insufficient (Pesonen et al., 2010) and poor sleep continuity (Sadeh, Raviv, & Gruber, 2000) are highly prevalent in children. Thus, explication of variables that facilitate or undermine sleep is warranted. Consistent with a health disparities framework (Buckhalt, 2011) and empirical evidence, insufficient sleep and poor sleep continuity are more pronounced for poor and ethnic minority children (for a review, see Gellis, 2011). However, individual differences may be operative and identification of vulnerability and protective factors in these associations can clarify for whom and under which conditions sleep may be more optimal or disrupted. Children’s support coping strategies in response to stress in their lives were examined as moderators of effects in the associations between socio-economic adversity (SES) and ethnicity (African American or AA, and European American or EA) and sleep.

Sleep was assessed with actigraphs, wristwatch-like devices that monitor activity for sleep-wake assessments. Actigraphy provides non-invasive objective assessments of sleep (in the child’s home in this study) and thus is frequently used in the child sleep literature. Two important actigraphy-based sleep parameters were considered: duration (minutes) and continuity (indexed by efficiency). Both short sleep duration and reduced sleep continuity (i.e., fragmented sleep) have been examined in many studies, and their assessment is of importance for building on this relatively young literature and clarifying the sleep domains that are associated with various predictors and sequelae in children. Herein, the term sleep problems refer to shorter duration (minutes) and poorer sleep continuity (efficiency) relative to other children in the sample. Support coping is defined as seeking social support from people when presented with a stressor (Nicolotti, El-Sheikh, & Whitson, 2003; Sandler, Tein, & West, 1994). SES is indexed by the family’s monetary resources using the family income-to-needs ratio (referred to as income for brevity), a standard measure of a family’s economic situation (U.S. Department of Commerce; ww.commerce.gov), which accounts for the number of individuals supported by the family income.

Children from lower income homes have shorter sleep duration and poorer sleep continuity (Adam, Snell, & Pendry, 2007; Ivanenko, Crabtree, & Gozal, 2005). Using actigraphic measures of sleep and a composite measure of SES that includes family income, El-Sheikh, Kelly, Buckhalt, and Hinnant (2010) predicted shorter sleep and/or worse sleep continuity in school-age children. Thus, children who live in families with low SES have a disproportionate number and degree of sleep problems than their higher SES counterparts (Buckhalt, 2011).

As with SES, ethnicity has been associated with health disparities for a number of diseases, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Recent work has pointed to sleep as an intervening mechanism in the differential development of these diseases by ethnicity (Kingsbury, Buxton, Emmons, & Redline, 2013). Basing their conclusions on results of the Sleep Heart Health Study, it is thought that poorer sleep of African American adults may be a target for possible disease prevention and intervention (Baldwin et al. 2010). As is the case with adults, African American children show poorer sleep than EA children in a number of studies. Young (2–8 year old) AA children have been found to sleep fewer hours per night than their EA counterparts (Crosby, LeBourgeois, & Harsh, 2005; Ivanenko, Crabtree, & Gozal, 2005; Montgomery-Downs, Jones, Molfese, & Gozal, 2003). This was also found for older AA children and adolescents (Adam et al., 2007; Spilsbury et al., 2004). There is also evidence that AA children are at greater risk for sleep problems even when economic adversity is controlled. For example, after controlling for SES, AA children tended to have shorter sleep duration and worse sleep continuity than EAs (Buckhalt, El-Sheikh, & Keller, 2007).

Another factor that plays a role in modulating sleep duration and continuity is stress (Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2009; Mezick et al., 2008; Sadeh, 1996; Sadeh & Gruber, 2002; Sadeh, Keinan, & Daon, 2004; Van Reeth et al., 2000). The response of the sympathetic nervous system to acute threat is to prepare the individual for a fight or flight response by activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and enhancing alertness, which are both incompatible with sleep (Van Reeth et al., 2000). Multiple studies have documented shorter and/or poorer sleep continuity in response to stress (Lavie, 2001; Sadeh, 1996; Van Reeth et al., 2000). The idea that coping style plays a moderating role in the links between stress and sleep has received empirical support mostly in studies conducted with adults (Gieselmann, Ophey, de Jong-Meyer, & Pietrowsky, 2012; Mezick et al., 2009; Sadeh et al., 2004). Perceived social support is a correlate of sleep in adults and has been related to a more consistent sleep schedule (Allgower, Wardle, & Steptoe, 2001). Further, greater perceived peer companionship and having someone to confide in were related to fewer actigraphy measured night wakings in adults (Troxel, Buysse, Monk, Begley, & Hall, 2010). Thus, even though perceived social support is a somewhat different construct than the support coping strategies examined in this study, it is consistent with the notion that social support may facilitate more optimal sleep. Further, support coping has positive effects on children’s emotional and behavioral adjustment (Nicolotti et al., 2003) and thus it is possible that it will have similar effects on children’s sleep.

This study focused on the proposition that for ethnic minority and low-income children, a higher level of support coping in response to stressors faced in everyday life may function as a protective factor against reduced sleep duration and poor sleep continuity; conversely, a lower level of such coping can function as a vulnerability factor. Identification of such variables that can confer increased risk for or protection from sleep problems in the context of socio-cultural adversity may have implications for prevention and intervention.

The Current Investigation

Social support seeking was examined as a moderator of the links between both ethnicity and family income-to-needs ratio and sleep. Sleep parameters examined were actigraphy-based sleep duration (minutes) and an established measure of sleep continuity, namely efficiency. It was expected that a higher level of support coping would function as a protective factor against shorter sleep duration and worse sleep continuity otherwise associated with minority status and economic adversity.

Method

Participants

Participants were 235 children and their mothers (113 boys, 122 girls; M age = 11.33 years, SD = 8.03 months, range = 10.00 to 14.25 years) enlisted in a larger study examining biopsychosocial influences on children’s health. The present investigation is based on data collected during the third study wave in 2011–2012. Most of these children participated in the first study wave (data collected during 2009–2010; no coping measures were administered at that time). Children were recruited from semi-rural school districts in the Southeastern United States. Exclusion criteria were based on mother’s reports and included a diagnosed sleep disorder or learning disability. Representative of the community, EA and AA children comprised 64% and 36% of the sample, respectively. Regarding mothers’ and fathers’ education, 30% and 45% had a high school diploma or less, 34% and 30% had partial college education, 26% and 18% had a college degree, and 10% and 7% had a graduate degree, respectively. Mothers reported on the Puberty Development Scale (1 = pre-pubertal; 2 = early pubertal; 3 = mid-pubertal; 4 = late pubertal; 5 = post-pubertal; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). Boys on average were pre-pubertal (M = 1.78, SD = .53) whereas girls were early pubertal (M = 2.33, SD = .59). Most children lived with their biological mother (n = 214); of these children, 57% (n = 123) also lived with their biological father, 18% (n = 38) lived with their mother’s partner (e.g., stepfather, boyfriend) and 25% (n = 53) lived with a single mother; the remaining 21 children lived in families with other structures. An additional 51 children participated in the larger study but were excluded from this analytic sample because of chronic physical illness, which often influences sleep (Ancoli-Israel, 2006); 41 had asthma and 10 had other illnesses (e.g., sickle cell, eczema, acid reflux, severe migraines, ulcers).

Procedure

In most cases actigraphs were mailed to families; in a few cases they were hand delivered. Parents were instructed to place the actigraph on the child’s non-dominant wrist at bedtime for seven consecutive nights and remove it each morning. To validate actigraphy assessments, children completed a sleep diary each day, which included reporting bed and wake times. To minimize confounds, participation occurred during the regular school year except on holidays. Families visited the laboratory after the completion of actigraphic assessments (M = 2.68 days, SD = 12.02) and returned the watches. Children completed questionnaires via an interview with a trained researcher and mothers reported on family income and child ethnicity. The university institutional review board approved the study, and parents and children provided informed consent and assent. Children and parents were compensated monetarily for their participation. Important to note is that all assessments of primary study variables (income, sleep and coping) were collected during the same study wave (i.e., third).

Measures

Income-to-needs ratio

Income-to-needs ratio is a standard measure of a family’s economic standing (U.S Department of Commerce; www.commerce.gov). Women reported on family household size in addition to family income using the following categories: (a) $10,000 to $20,000, (b) $20,000 to $35,000, (c) $35,000 to $50,000, (d) $50,000 to $75,000, (e) more than $75,000. Income-to-needs ratio was computed by dividing the mean of family income range by the federal poverty threshold for that family’s household size (e.g., in 2011, a family of four with an annual income < $23,021 was considered to be living in poverty). An income-to-needs ratio ≤ 1 corresponds with poverty status (31% of the sample); 1 to 2 = living near the poverty line (21%); 2 to 3 = lower middle class (21%); and 3 to 4 = middle class to upper class income (14%); 13% of families had an income-to-needs ratio > 4. Despite oversampling to recruit EAs and AAs across a wide range of economic backgrounds, ethnicity and income-to-needs ratio were associated (r = .44; ethnicity was dummy coded such that AA = 1 and EA = 0).

Coping with stress

Through interviews with a research assistant, children reported on the 10-item Support Coping Scale of the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (Program for Prevention Research, 1999). Responses provide a measure of coping in response to stress in general versus coping in response to a particular stressor. Children are read the following directions prior to completing the items: “Sometimes kids have problems or feel upset about things. When this happens, they may do different things to solve the problem or to make themselves feel better. Below is a list of things kids may do when faced with a problem. For each item, select a response that best describes how often you usually do the behavior when you have a problem. There are no right or wrong answers just indicate how often you usually do each thing in order to solve the problem or to make yourself feel better.” Examples of items include, “When I have a problem, I talk to someone who might understand how I feel” and “When I have a problem, I figure out what I can do by talking with one of my friends.” Items are rated from never (1) to most of the time (4). Higher scores correspond with higher support coping strategies. This measure has good internal consistency and validity (Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, 1996; Program for Prevention Research, 1999) and has been commonly used in the child development and coping literature (e.g., Sandler, Tein, Mehta, Wolchik, & Ayers, 2000). In this study α = .82.

Sleep

Octagonal Basic Motionloggers and a corresponding software package (ActionW2; Ambulatory Monitoring Inc., Ardsley, NY) were used to measure motion in 1-min epochs using zero crossing mode; Sadeh’s scoring algorithm was used (Sadeh, Sharkey, & Carskadon, 1994). Actigraphy scoring was validated using sleep diaries (Acebo & Carskadon, 2001). The actigraph and software packages have demonstrated validity for the measurement of children’s sleep (Sadeh et al.,1994).

The assessment of different actigraphy-based sleep parameters is recommended (Sadeh et al., 2000). Thus, we examined the following well-established parameters: (a) Sleep Minutes – total minutes scored as sleep between sleep onset and wake time; and (b) Sleep Efficiency –% of epochs scored as sleep between sleep onset and wake time. Actigraphy variables were created by computing an average score across all available nights; 70% of children had actigraphy data for ≥ five nights, 17% had three or four nights, and 13% had two nights or fewer of data. Reasons for missing data included forgetting to wear the actigraph, mechanical problems, and medicine use (e.g., for headache or allergy) and these nights were excluded from analyses. Fewer than three nights of actigraphy assessment provides a poor estimation of regular sleep (Acebo et al., 1999), thus actigraphy data for children who had < three nights of valid data were excluded from analyses (n = 30). Intraclass correlations showed good stability across the week for each sleep parameter: Sleep Minutes = .83 and Sleep Efficiency = .94.

Plan of Analysis

Path models were fit and all primary study variables (i.e., income, child ethnicity, support coping, sleep minutes, and sleep efficiency) were treated as observed variables. To reduce outlier effects, values that exceeded 3 SDs among study variables were recoded as the highest observed value below 3 SDs (Bush, Hess, & Wolford, 1993). This occurred for sleep minutes (n = 1) and sleep efficiency (n = 5). Sleep efficiency was skewed and natural log transformed.

Two models were fit. In the first model, the direct effects of child gender, ethnicity, income, and support coping on children’s sleep minutes and efficiency were estimated. Note that while examining relations between ethnicity and children’s sleep, income was controlled and vice versa. In addition, the interaction term, Income×Support Coping (Figure 1) was included to examine whether support coping moderated relations between income and children’s sleep (while controlling for ethnicity). Sleep minutes and sleep efficiency were assessed simultaneously in the same model to account for their shared associations. The second model was identical in nature to the first model with the exception that the interaction term, Ethnicity×Support Coping, was included to examine whether support coping moderated relations between ethnicity and children’s sleep (while controlling for income). We elected to examine each interaction term in a separate model to reduce the likelihood of multi-collinearity. Interactions were plotted at high (+1 SD) and low (-1 SD) levels of the predictor and moderator (Aiken & West, 1991), with the exception of ethnicity, which was treated as a categorical variable. Preacher, Curran, and Bauer’s (2006) interaction utility was used to plot interactions using estimates obtained from the fitted models.

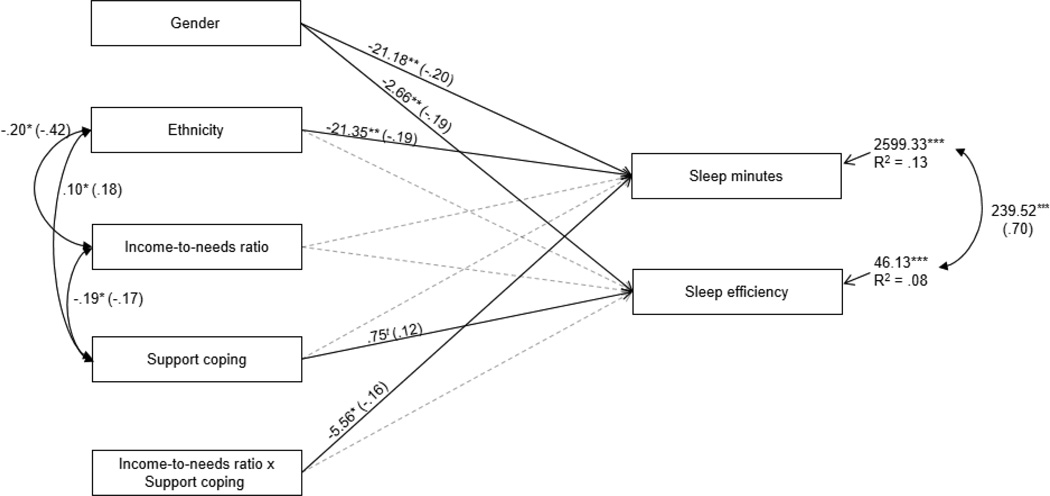

Figure 1.

Examination of support coping as a moderator of associations between income-to-needs ratio and children’s sleep minutes and sleep efficiency. Non-significant covariances among exogenous variables were omitted from the model. Residual variances among endogenous variables were allowed to correlate. Unstandardized and standardized coefficients (in parentheses) are provided. For ease of interpretation, statistically significant lines are solid whereas non-significant lines are dotted. Ethnicity is dummy coded such that 1 = African American and 0 = European American. Child gender is dummy coded such that 1 = boys and 0 = girls. Model fit: χ2 = 8.68, ns, df = 7; χ2 /df = 1.24; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03 ns.

tp<.10; *p<.05; **p < .01; ***p<.001.

We considered controlling for variables that have been associated with sleep in the literature, including child gender, pubertal status, and age. We used Δχ2 tests to determine whether the control variables had a significant effect; for consistency across models, if the inclusion of a control variable resulted in a significant change in χ2 in at least one model, the covariate was retained for all fitted models. Based on this criterion, child gender was controlled in the models, and was allowed to correlate with income, ethnicity, the coping variables, and the interaction terms, and was allowed to predict the sleep variables.

Analyses were conducted using AMOS 17. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to handle missing data (Acock, 2005). Non-significant covariances among exogenous variables were omitted from each model to increase degrees of freedom. The residual variances among endogenous variables were allowed to correlate. Acceptable model fit was based on satisfying at least two of the three following criteria: χ2/df < 3, CFI > .90, and RMSEA ≤ .08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993); both fitted models satisfied these criteria. In initial analyses, we examined exacerbation of risk by assessing three-way interactions between ethnicity, income, and support coping in the prediction of sleep; no significant interactions were detected. Similarly, initial analyses of moderation by gender did not yield significant findings.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations are provided in Table 1. The average amount of time in bed (sleep diary) was ~ 8.10 hrs per night and actual amount of sleep (actigraphy - sleep minutes) was ~ 7.40 hrs. Average sleep efficiency was below 90%, which is considered an indicator of poor sleep continuity (Sadeh et al., 2000).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child gender | - | -- | -- | ||||||

| 2. Income-to-needs ratio | .13 | - | 1.58 | 1.00 | |||||

| 3. Ethnicity (1 = AA, 0 = EA) | .96 | −.44** | - | -- | -- | ||||

| 4. Support Coping | −.09 | −.17* | .18** | - | 4.32 | 1.15 | |||

| 5. Sleep minutes | −.20** | .13t | −.23*** | .11 | - | 439.16 | 53.14 | ||

| 6. Sleep efficiency | −.18** | .05 | −.13t | .11 | .68*** | - | 89.51 | 6.83 |

Note. Child gender was dummy coded (1=boy, 0 = girl). AA = African American; EA = European American

p<.10;

p<.05;

p < .01;

p<.001

Support Coping as a Moderator of Associations between Income and Sleep

The model that examined support coping as a moderator of effects among relations between income and sleep was a good fit to the data, χ2 = 8.68, ns, df = 7; χ2 /df = 1.24; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03 ns. (Figure 1). In total, the model explained 13% of the variance in sleep minutes and 8% of the variance in sleep efficiency. Regarding direct effects, male status was related to fewer sleep minutes and reduced sleep efficiency and accounted for 5% and 4% of unique variance, respectively. AA status was related to fewer sleep minutes and accounted for 4% of unique variance. In addition, greater support coping was moderately (p = .08) related to a higher sleep efficiency and accounted for 4% of unique variance.

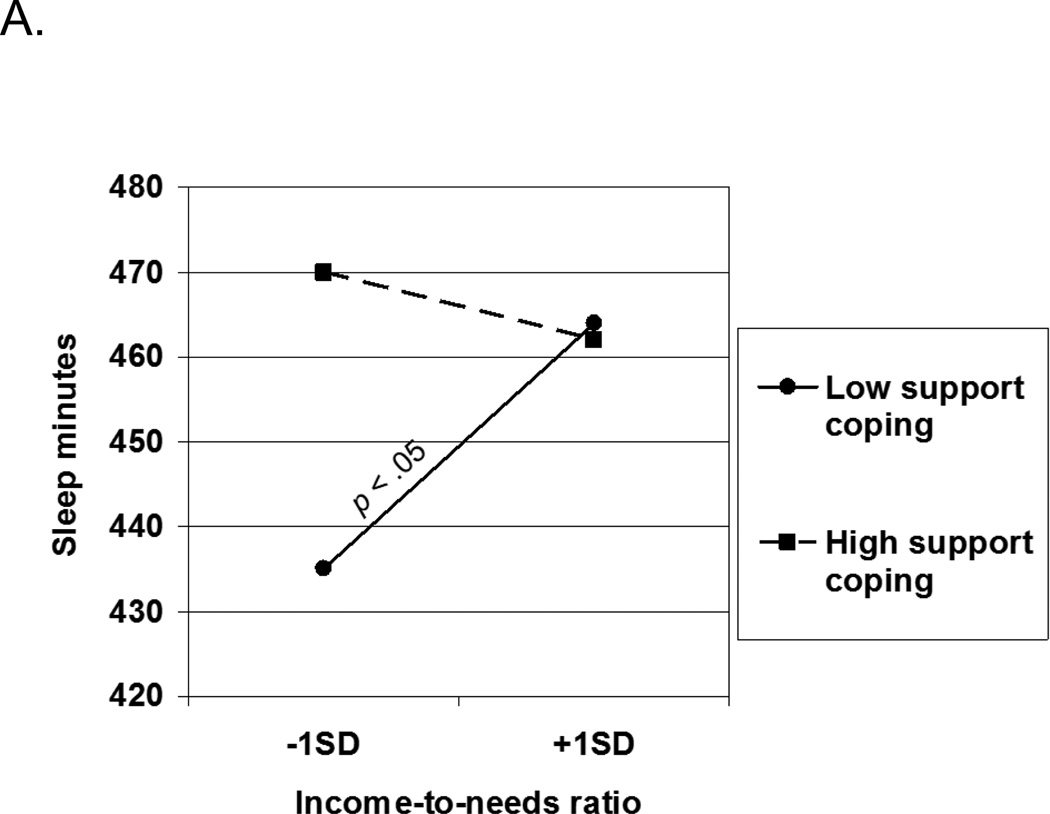

Support coping moderated associations between income and sleep minutes. The interaction is depicted in Figure 3A, and accounted for 4% of unique variance in sleep minutes. For children from families with more monetary resources (higher income), predicted means for sleep minutes were high and did not differ based on the level of support coping (M = 464 min for those with low support coping, and M = 462 for those with high coping). However, for children from families with lower income, a large difference in sleep minutes was observed between children with low (435 min) and high support coping (470 min). As shown in the Figure, children from lower income families with low support coping had the shortest sleep. Also, note that the association between economic adversity and sleep minutes was significant only for children with lower support coping strategies. This pattern of effects shows a protective function of support coping in the link between economic adversity and reduced sleep minutes.

Figure 3.

Support coping as a moderator of relations between income-to-needs ratio and children’s sleep. For slopes that differ from zero, the p value is presented next to the slope.

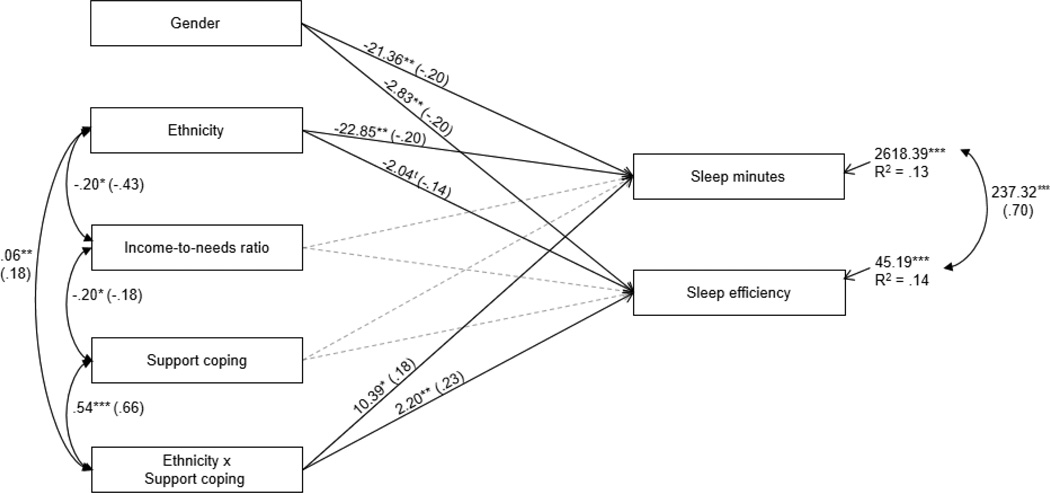

Support Coping as a Moderator of Associations between Ethnicity and Sleep

The model fit to examine the moderating role of support coping among relations between ethnicity and sleep was a good fit to the data, χ2 = 14.50, p = .03, df = 6; χ2 /df = 2.42; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 ns (Figure 2). The model explained 13% of the variance in sleep minutes and 14% of the variance in sleep efficiency. The direct relations of child gender and ethnicity on the sleep variables were nearly identical to those reported in Figure 1, with the exception that AA status was moderately related to reduced sleep efficiency (ΔR2 = 4%) and support coping was not related to sleep minutes nor sleep efficiency. Both tested interaction effects were statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Examination of support coping as a moderator of associations between ethnicity and children’s sleep minutes and sleep efficiency. Non-significant covariances among exogenous variables were omitted from the model Residual variances among endogenous variables were allowed to correlate. Unstandardized and standardized coefficients (in parentheses) are provided. For ease of interpretation, statistically significant lines are solid whereas non-significant lines are dotted. Ethnicity is dummy coded such that 1 = African American and 0 = European American. Child gender is dummy coded such that 1 = boys and 0 = girls. Model fit: χ2 = 14.50, p = .03, df = 6; χ2 /df = 2.42; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 ns.

tp<.10; *p<.05; **p < .01; ***p<.001.

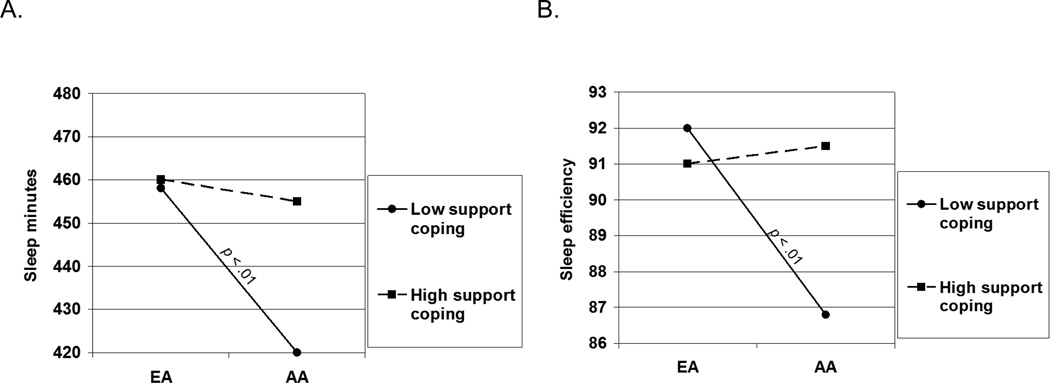

Support coping moderated the relation between ethnicity and children’s sleep minutes (Figure 2; ΔR2 = 4%). For children with higher levels of support coping, greater sleep minutes were observed for both EAs (M = 460 min) and AAs (M = 455 min); greater sleep minutes was also observed for EAs with low support coping (M = 458) (Figure 4A). The fewest sleep minutes were found for AAs who reported low support coping (M = 420 min). Thus, high support coping was a protective factor against fewer sleep minutes for AA children.

Figure 4.

Support coping as a moderator of relations between ethnicity and children’s sleep. For slopes that differ from zero, the p value is presented next to the slope. EA = European American; AA = African American.

Support coping moderated associations between ethnicity and children’s sleep efficiency, and accounted for 6% of unique variance. For children with high support coping, high levels of sleep efficiency were observed for both EAs (M = 91.05) and AAs (M = 91.45); high sleep efficiency was also observed for EAs with low coping (M = 91.90) (Figure 4B). However, the lowest sleep efficiency was found for AA children who reported low support coping (M = 86.82). Thus, a high level of coping was a protective factor against reduced sleep efficiency for AA children.

Discussion

Consistent with a health disparities framework, the literature shows increased sleep problems in AA children and those exposed to economic adversity. However, these socio-cultural contexts do not result in disadvantage for all children, and factors that offer protection against such risks are operative for some children. Toward identifying variables that can protect children against sleep problems, we investigated support coping strategies as moderators of relations among both AA ethnicity and low income and sleep minutes and efficiency. Findings offer support for the proposition that a higher level of support coping when faced with stress provides protection against reduced sleep duration and poor sleep continuity otherwise associated with AA status and lower family income (the latter applies to sleep minutes not efficiency). Given the important role of adequate sleep duration and good sleep efficiency for positive outcomes in many child health domains, and the negative outcomes associated with poor sleep, findings are of potential significance.

As compared with individuals from higher SES homes, the literature generally shows shorter sleep duration and poorer sleep continuity among those from lower income homes (Krueger & Friedman, 2009; Stamatakis, Kaplan, & Roberts, 2007). Although children exposed to economic adversity have a disproportionate number and degree of sleep problems, moderation effects from this study illustrate that children’s support coping strategies influence the SES-sleep link. Specifically, children from both lower and higher income homes tended to have longer sleep minutes when they reported engaging in higher levels of support coping. However, the association between low income and worse sleep was only apparent for children who reported low levels of support coping. These findings are consistent with cumulative risk perspectives (e.g., Evans & English, 2002) in that low SES coupled with lower support coping was predictive of the shortest sleep minutes. This perspective may provide a plausible explanation for why children from higher SES homes did not accrue added benefit to their sleep when they engaged in higher levels of support coping; these children tended to have similar predicted means for sleep minutes regardless of coping. Thus, the coping-sleep link needs to be considered in the context of the broader socio-cultural milieu, and identification of variables associated with SES (e.g., increased stress exposure) that may be tied to both sleep and coping is warranted. Prevention and intervention efforts aimed at facilitating support coping strategies for children exposed to cumulative stress may lead to better sleep in children.

Ethnicity has been related to sleep in children, with AAs showing poorer sleep (Adam et al., 2007; Crosby et al., 2005; Montgomery-Downs et al., 2003) even when SES is controlled (Buckhalt et al., 2007). In the present study, assessment of ethnicity controlled for SES and vice versa; however, the two were moderately associated. Across all sleep parameters, both EA and AA children with high support coping exhibited longer sleep duration and better sleep continuity. However, only AA children tended to have fewer sleep minutes and poorer sleep efficiency when they engaged in low support coping. Consequently, it appears that AA children benefited the most from a higher level of support coping, which functioned as a protective factor against their sleep disruptions. It is not clear why EA children did not benefit from high support coping in relation to their sleep minutes or efficiency; they tended to have good sleep regardless of their coping behavior. It is plausible that aggregation of risk (Evans & English, 2002) may explain these findings at least in part. For example, in the context of assumed lower stress (e.g., ethnic discrimination) experienced by children from ethnic majority backgrounds, social support may not be highly imperative for sleep. Further, the role of coping may be different in the context of the AA and EA subcultures. Thus, in such a scenario, the role of support coping may be context dependent. Interpretation of findings is obviously speculative.

Across all models, moderation effects were more pronounced than direct effects, and more variance in sleep parameters was accounted for with the incorporation of both income (Figure 1) and ethnicity (Figure 2) as moderators. While the unique variance explained by the interaction effects is modest (albeit similar to the magnitude of such effects in the broader literature), the pattern of effects is of importance. Specifically, while children from families with more monetary resources tended to sleep longer (~ 462 to 464 min) regardless of their support coping, the sleep of those with fewer resources varied depending on whether they reported higher (470 min) or lower (435 min) levels of support coping. A daily average of a 35-minute difference in sleep time could lead to a serious accumulated sleep deprivation problem. It has been demonstrated in an experimental study that extending or restricting sleep by close to 40 minutes on three consecutive nights led to striking differences in neurobehavioral functioning in memory and attention in the sleep-restricted group (Sadeh, Gruber, & Raviv, 2003). Similarly, the effect on sleep efficiency (i.e., 91.45% vs. 86.82%) was significant. A sleep efficiency cutoff below 90% has been proposed for the definition of poor sleep (Sadeh et al., 2002; Sadeh et al., 2000). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that poor sleep using this definition is associated with compromised neurobehavioral functioning and behavior problems (Sadeh et al., 2002). Therefore, the effect seen in our study appears to reflect potentially important differences between good and poor sleepers and not just statistical significance.

Results lend additional support to theories about the moderating role of coping style in the links between sleep and stress (Sadeh, 1996; Sadeh & Gruber, 2002; Sadeh et al., 2004). In a quasi-experimental design,Sadeh et al. (2004) examined whether emotion- and problem-focused coping moderated relations between stress exposure and sleep among undergraduate college students applying for graduate school. Greater emotion-focused coping predicted fewer actigraphy measured sleep minutes from a low (i.e., regular academic week) to high stress period (i.e., the week the students were being evaluated for acceptance into graduate school). Thus, although findings from this investigation and that of Sadeh et al. (2004) may be contradictory, the methods were different. For example, in Sadeh et al. (2004), assessment of emotion-focused coping was based on the extent to which an individual regulated their emotional responses to the stressor (e.g., I let my feelings out) as opposed to seeking emotional support from others, which is the focus of the current study.

Our findings may have clinical implications for stress-related interventions during child development. If support coping with stressful events protects the sleep of children, especially those who are likely exposed to many stressors in their lives such as children from low-income homes, then encouraging or training children in adopting this strategy should be considered an important feature of prevention and intervention efforts. When considering the positive effects of parental and social support during stressful times, and the many positive health outcomes associated with optimal sleep, the ability to actively seek and “invite” social support may be important target skills for child well-being.

The study has limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the findings. Characteristics of this semi-rural community sample limit generalization of results to children with clinically significant sleep problems or those residing in urban areas that may be exposed to a different set of variables associated with ethnicity and economic adversity. Identification of SES- and ethnicity-related variables that may underlie their associations with sleep is critical; many questions arise as to why these associations exist in this study and in the literature at large. Factors associated with SES (e.g., physical environment in the home and the community including noise, temperature, and violence) and ethnicity (e.g., preference for co-sleeping arrangements, discrimination, and fluidity in both the definition of the family and where one sleeps) are potential targets for assessment. While identification of these factors are likely to enhance intervention efforts, it is noteworthy that children’s support coping emerged as a protective factor facilitating longer sleep duration and better sleep continuity even in contexts that are frequently associated with health disparities.

Contributor Information

Mona El-Sheikh, Auburn University.

Ryan J. Kelly, University of New Mexico

Avi Sadeh, Tel Aviv University.

Joseph A. Buckhalt, Auburn University

References

- Acebo C, Carskadon M. Scoring actigraph data using action-w. Vol. 2. Providence, RI: Bradley Sleep Center, Brown University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Acebo C, Sadeh A, Seifer R, Tzischinsky O, Wolfson A, Hafer A, Carskadon MA. Estimating sleep patterns with actigraphy monitoring in children and adolescents: How many nights are necessary for reliable measures? Sleep. 1999;22:95–103. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Snell EK, Pendry P. Sleep timing and quantity in ecological and family context: A nationally representative time-diary study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:4–19. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allgower A, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Depressive symptoms, social support, and personal health behaviors in young men and women. Health Psychology. 2001;20:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S. The impact and prevalence of chronic insomnia and other sleep disturbances associated with chronic illness. American Journal of Managed Care. 2006;12:S221–S229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers TS, Sandler IN, West SG, Roosa MW. A dispositional and situational assessment of children's coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality. 1996;64:923–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CM, Ervin AM, Mays MZ, Robbins J, Shafazand S, Walsleben J, Weaver T. Sleep disturbances, quality of life, and ethnicity: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2010;6:176–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhalt JA. Insufficient sleep and the socioeconomic status achievement gap. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M, Keller P. Children's sleep and cognitive functioning: Race and socioeconomic status as moderators of effects. Child Development. 2007;78:213–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush LK, Hess U, Wolford G. Transformations for within-subject designs: A monte carlo investigation. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:566–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charuvastra A, Cloitre M. Safe enough to sleep: Sleep disruptions associated with trauma, posttraumatic stress, and anxiety in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;18:877–891. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Beydoun MA, Wang Y. Is sleep duration associated with childhood obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity. 2008;16:265–274. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby B, LeBourgeois MK, Harsh J. Racial differences in reported napping and nocturnal sleep in 2- to 8-year-old children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:225–232. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0815D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Kelly RJ, Buckhalt JA, Hinnant BJ. Children's sleep and adjustment over time: The role of socioeconomic context. Child Development. 2010;81:870–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, English K. The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73:1238–1248. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellis L. Children's sleep in the context of socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity. In: El-Sheikh M, editor. Sleep and development: Familal and socio-cultural considerations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- Gieselmann A, Ophey M, de Jong-Meyer R, Pietrowsky R. An induced emotional stressor differentially decreases subjective sleep quality in state-oriented but not in action-oriented individuals. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;53:1007–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenko A, Crabtree VM, Gozal D. Sleep and depression in children and adolescents. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2005;9:115–129. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury JH, Buxton OM, Emmons KM, Redline S. Sleep and its relationship to racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports. 2013;7:387–394. doi: 10.1007/s12170-013-0330-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL. Does inadequate sleep play a role in vulnerability to obesity? American Journal of Human Biology. 2012;24:361–371. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep duration in the United States: A cross-sectional population-based study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169:1052–1063. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie P. Current concepts: Sleep disturbances in the wake of traumatic events. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1825–1832. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezick EJ, Matthews KA, Hall M, Kamarck TW, Buysse DJ, Owens JF, Reis SE. Intra-individual variability in sleep duration and fragmentation: Associations with stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1346–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezick EJ, Matthews KA, Hall M, Strollo PJ, Jr, Buysse DJ, Kamarck TW, Reis SE. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on sleep: Pittsburgh sleep score project. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:410–416. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816fdf21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery-Downs HE, Jones VF, Molfese VJ, Gozal D. Snoring in preschoolers: Associations with sleepiness, ethnicity, and learning. Clinical Pediatrics. 2003;42:719–726. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolotti L, El-Sheikh M, Whitson SA. Children's coping with marital conflict and their adjustment and physical health: Vulnerability and protective functions. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:315–326. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen AK, Raikkonen K, Paavonen EJ, Heinonen K, Komsi N, Lahti J, Strandberg T. Sleep duration and regularity are associated with behavioral problems in 8-year-old children. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;17:298–305. doi: 10.1007/s12529-009-9065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Program for Prevention Research. Manual for the Children's Coping Strategies Checklist and the How I Coped Under Pressure Scale. Tempe, AZ: Prevention Research Center, Arizona State University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A. Evaluating night wakings in sleep-disturbed infants: A methodological study of parental reports and actigraphy. Sleep. 1996;19:757–762. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.10.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A. Consequences of sleep loss or sleep disruption in children. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2007;2:513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Gruber R. Stress and sleep in adolescence: A clinical-developmental perspective. In: Carskadon MA, editor. Adolescent sleep patterns: Biological, social, and psychological influences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Development. 2002;73:405–417. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. The effects of sleep restriction and extension on school-age children: What a difference an hour makes. Child Development. 2003;74:444–455. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Keinan G, Daon K. Effects of stress on sleep: The moderating role of coping style. Health Psychology. 2004;23:542–545. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Raviv A, Gruber R. Sleep patterns and sleep disruptions in school-age children. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:291–301. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Sharkey KM, Carskadon MA. Activity-based sleep-wake identification: An empirical test of methodological issues. Sleep. 1994;17:201–207. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein JY, Mehta P, Wolchik S, Ayers T. Coping efficacy and psychological problems of children of divorce. Child Development. 2000;71:1099–1118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein JY, West SG. Coping, stress, and the psychological symptoms of children of divorce: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Child Development. 1994;65:1744–1763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Drotar D, Rosen CL, Kirchner LH, Benham H, Redline S. Sleep behavior in an urban US sample of school-aged children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:988–994. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis KA, Kaplan GA, Roberts RE. Short sleep duration across income, education, and race/ethnic groups: Population prevalence and growing disparities during 34 years of follow-up. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.07.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel WM, Buysse DJ, Monk TH, Begley A, Hall M. Does social support differentially affect sleep in older adults with versus without insomnia? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Reeth O, Weibel L, Spiegel K, Leproult R, Dugovic C, Maccari S. Interactions between stress and sleep: From basic research to clinical situations. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2000;4:201–219. [Google Scholar]