Abstract

The improved bioavailability, stability and selectivity of cyclic peptides over their linear counterparts make them attractive structures in the design and discovery of novel therapeutics. In our previous work, we developed an imidazole-promoted preparation of cyclic depsipeptides in which we observed that increasing the concentration of imidazole resulted in the concomitant increase in the yield of cyclic product and reduction in dimerization, but also resulted in the generation of an acyl-substituted side product. In this work, we used transition state analysis to explore the mechanism of the imidazole-catalyzed esterification of one such peptide, Ac-SAFYG-SCH2ϕ, and determined the acyl substitution product to be an intermediate in a competing reaction pathway involving acyl substitution of the thioester by imidazole. Our findings indicate that imidazole plays an essential role in this side-chain to C-terminal coupling, and by extension, in transesterifications in general, through a concerted mechanism wherein imidazole deprotonates the nucleophile as the nucleophile attacks the carbonyl. The system under study is identical to the histidine-serine portion of the catalytic triads in serine proteases and it is likely that these enzymes employ the same concerted mechanism in the first step of peptide cleavage. Additionally, relatively high concentrations of imidazole must be used to effectively catalyze reactions in aprotic solvents since the overall reaction involves imidazole acting both as an acid and as a base, existing in solution as an equilibrium distribution between the neutral form and its conjugate acid.

Introduction

Biologically active cyclic peptides have been found in an increasing number of plant and animal species. Chain length can vary widely, as can the mode of cyclization. In homodetic (‘head-to-tail’) cyclic peptides, the cyclic backbone consists exclusively of true peptide bonds, as in the cyclooctapeptide planktocyclin, which is a strong inhibitor of mammalian trypsin and chymotrypsin.1 While in heterodetic peptides, the backbone includes at least one other type of linkage such as ester bonds, isopeptide bonds, or disulfide bridges. Examples of such structures are cyclic depsipeptides,2 glutathione, the conotoxins,3 and the trypsin inhibitor SFTI-1, with a single disulfide bridge.4 The biological and medical significance of cyclic peptides as potential therapeutics is evinced by an increasing number of publications describing their antiviral,5 hemolytic6 and anti-helminthic7 activities. Cyclic peptides owe at least a part of their importance in nature to their tendency to resist degradation by exopeptidases. In addition, cyclization tends to increase the rigidity of the three-dimensional structure and this can add further to the resistance to peptidases in general8 and greatly enhance the intrinsic biological activity of the molecule.9 The beneficial impact of this structural rigidity on activity can be further enhanced by the incorporation of additional disulfide bridges into the structure, as was recently shown by Pakkala et al. in cyclic peptides containing disulfide bridges with promising prostate anti-cancer activity.10

The synthesis of cyclic peptides and depsipeptides based on structures from natural products is well established11 and methods of cyclizing linear peptides has been described in the literature.12 As the cyclization of biologically-active peptides has been shown to improve both bioavailability and selectivity, the adoption of these structures in the development of combinatorial libraries for drug discovery is gaining importance in pharmaceutical research initiatives. The design, synthesis and screening of large combinatorial libraries as mixtures has enabled us to discover potent and selective ligands for a variety of biologically relevant targets13 with substantial improvements in both time and cost over conventional high throughput screening. Applying these synthetic and screening techniques to libraries of cyclic peptides should lead to the rapid identification of compounds with promising therapeutic profiles. Efficient strategies for the synthesis of combinatorial libraries have been well-documented in the literature,14 yet the application of these methods to the development of cyclic peptide libraries has been met with challenges related to peptide cyclization in general; specifically, side reactions, dimerization/polymerization, and the effects of ring size and inclusion of non-turn-inducing residues on reaction rates and product yields. A recent study shows that, based on their conformational properties, cyclotetrapeptides can be viewed as 3D scaffolds.14f Head-to-tail linkages typically involve activation of the C-terminal carboxyl group, followed by nucleophilic attack of the activated carbonyl by the neutralized N-terminus. Depsipeptide cyclizations, which involve linking an N-terminal serine side-chain to the C-terminus of the linear precursor, require nucleophilic attack on a carbonyl by a weak nucleophile (the serine hydroxyl) in order to complete the cyclization, which, in turn, requires activation of the carbonyl group.

We recently developed an imidazole-promoted macrolactonization of peptide thioesters to prepare cyclic depsipeptides. The natural cyclic depsipeptide kahalalide B has been synthesized in high yield using this method15 and peptide phenyl ester ligation reactions by imidazole have been reported by others.15b In our search for ideal experimental conditions for depsipeptide synthesis, we found that cyclization only took place under high concentration of imidazole, typically around 1 M. Imidazole is known as an acyl transfer catalyst,16 facilitating transfer in reactions between amines and dimethylformamide and in lactam cyclizations that do not otherwise proceed under standard conditions. In the process of synthesizing some natural depsipeptides, we detected the presence of a peptidyl acylimidazole as an intermediate in the reaction mixture, which allowed us to postulate cyclization pathways involving the catalytic participation of imidazole.

Key transitions along these pathways are structurally reminiscent of the systems found in the catalytic sites of serine proteases, which are responsible for the peptidase (and esterase) activity of these enzymes. Serine proteases possess a triad of residues in their active sites that lie in close proximity and function as a charge relay system to catalyze the cleavage of peptide chains. The most frequently encountered of these catalytic triads consists of the three amino-acid residues aspartate, histidine, and serine. Exhibiting an effective pKa well above the usual values found in proteins,17 the histidine imidazolium moiety deprotonates the serine, which then acts as a nucleophile toward the amide carbonyl of a bound peptide ligand. This reaction mechanism, highlighted in most biochemistry texts, has been studied extensively18 through residue deletion and kinetics studies, as well as by X-ray crystallography of enzymes in complex with bound ligands, and is typically depicted graphically as a concerted mechanism, although not explicitly described as such in the accompanying texts. Our mechanistic study of the cyclization of depsipeptides using density functional theory (DFT) presented here proposes two isoenergetic cyclization pathways, provides one explanation for the need of high concentrations of imidazole, and ultimately shows how a concerted deprotonation step is energetically feasible, coinciding with and implicitly confirming the histidine-mediated deprotonation step proposed to occur in cleavage by serine proteases. These findings provide insights on the role of imidazole on chemical synthesis in general.

Results

Experimental conditions for peptide cyclization

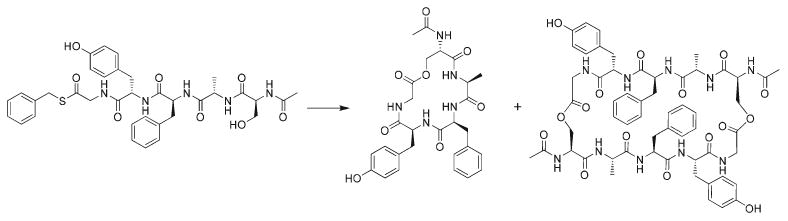

Typically, in N-to-C terminus macrolactamizations, a chemically activated C-terminal carbonyl reacts with a neutralized N-terminal amine to achieve cyclization of the peptide. In the present work, the side-chain hydroxyl group of the acylated N-terminal serine reacts with the C-terminal carbonyl, which has been activated through thioester transesterification, in order to complete the cyclization. The structure of the pentapeptide studied here, Ac-SAFYG-SCH2ϕ (I), is shown in Scheme 1, along with those of the cyclic monomer and cyclic dimer.

Scheme 1.

The cyclization of Ac-SAFYG-SCH2ϕ (I) on the left yields the cyclic monomer (l) and the cyclic dimer (r).

The impact of imidazole on the macrolactonization of I was investigated by adding increasing quantities of imidazole to promote cyclization (Table 1). It was found that adding what should be considered a catalytic amount of imidazole (0.5% mole ratio) did not promote cyclization: conversion of the linear peptide thioester to the cyclic monomer and dimer was very slow (5 days) and with low yields when the concentration of imidazole was below 0.5 M. Adding much larger quantities of imidazole, beyond expected catalytic amounts, dramatically improved the yield of cyclic product (92% product composition at an imidazole concentration of 1.5 M), with the degree of peptide cyclization increasing with increasing imidazole concentration. Maximal effect was observed at an imidazole concentration of 1.5 M (a 1000 : 1 mole ratio of imidazole to linear peptide), which is well beyond a conventional catalytic concentration. It is interesting that the yields of the cyclic monomer and the cyclic dimer are dependent on the imidazole concentration, with greater effect to the formation of the cyclic monomer. This effect shows that the participation of imidazole in the cyclization mechanism has the same effect in the formation of the monomer and the dimer. The dependence on such large concentrations of imidazole suggested that imidazole might be acting as a base, removing the hydroxyl proton of serine and making it a much stronger nucleophile. But considering these results strictly in terms of basicity, it is difficult to rationalize how such a weak base could induce cyclization and dimerization. The pKa of the serine hydroxyl is approximately 13, well above the pKa of imidazole in water (∼7.0): that imidazole could abstract a proton from an alcohol, given the relative proton affinities of the species involved, seemed unlikely. Although the H-bonding energy of imidazole to the hydroxyl hydrogen is at the upper end of the hydrogen bond energy range (the imidazole–water analog has been calculated19 to be ∼7 kcal mol−1), imidazole should not be expected to abstract a proton from an alcohol in bulk solution.

Table 1. The effects of imidazole concentration on reaction product compositions, as determined from LC-MS peaks, at room temperature with starting peptide concentration of 1 mM.

| Imidazole concentration (M) | Percent composition | Reaction time (h) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Cyclic monomer | Cyclic dimer | Starting peptide | ||

| 0.3 | 14.1 | 8.9 | 77.0 | 126 |

| 0.5 | 71.7 | 6.9 | 21.4 | 120 |

| 1.0 | 84.8 | 15.2 | — | 24 |

| 1.5 | 92.3 | 7.7 | — | 24 |

Another possibility regarding the mode of catalysis involved the nucleophilic substitution of the C-terminal thiobenzyl group by imidazole, resulting in a peptidyl acyl imidazole (Scheme 2). We had previously observed this type of intermediate in the reaction mixtures of some cases of difficult to cyclize depsipeptides. This suggested the presence of an alternate cyclization pathway in which the acyl imidazole structure represented a reaction intermediate and which might be more energetically favorable. It is also possible that the imidazolium moiety in (Scheme 2, II) presents slightly less steric inhibition to the formation of a van der Waals complex with the incoming nucleophile than does the thiobenzyl group in I, which may contribute to the observed cyclization. It was proposed, therefore, that the overall reaction was being catalyzed by imidazole, proceeding via an acyl-substituted intermediate (Scheme 2, II) that could provide a lower transition barrier to cyclization versus that of the uncatalyzed pathway.

Scheme 2.

The peptide Ac-SAFYG-SCH2ϕ (I) on the left and the imidazole substitution product (II) on the right.

Proposed mechanism of imidazole catalysis of peptide cyclization

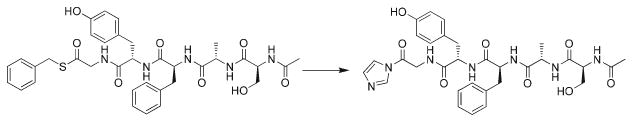

To rationalize the experimental findings, two reaction pathways were postulated involving the catalytic participation of imidazole in the cyclization reaction of I. Using molecular fragments to represent the N- and C-terminal ends of the larger peptide, as shown in Fig. 1 and 2, we sought to model the thermodynamics of the transitions involved with the reactive portions of the larger peptides using density functional theory. In the first pathway, imidazole replaces the thioate in an acyl substitution reaction, cyclization then occurs with imidazole as the final leaving group. In the second pathway, imidazole participates in a more auxiliary capacity, stabilizing transition states and the alkoxide intermediate, with the thioate as the final leaving group. In both pathways, imidazole acts as a base, abstracting a proton from the serine hydroxyl (here modeled using methanol) and as its conjugate acid to protonate the phenylmethanethiolate leaving group, with no net change in stoichiometry, thus acting as a true catalyst. Protonated imidazolium ions were included in transition state complexes and intermediate complexes to stabilize the carbonyl/alkoxide oxygens through hydrogen bonding or ion pairing. In the actual peptide, it is likely that stabilization of the reactive sites occurs through hydrogen bonding interactions with the peptide backbone.

Fig. 1.

Proposed mechanism of imidazole catalysis in the acyl substituted reaction pathway using model fragments of the larger peptide.

Fig. 2.

Proposed mechanism of imidazole catalysis in the unsubstituted reaction pathway using model fragments of the larger peptide.

The first step along the substitution pathway (Fig. 1) involves nucleophilic attack by imidazole on the thioester carbonyl, forming a tetrahedral alkoxide zwitterion. The imidazolium moiety is deprotonated, leaving a negatively-charged alkoxide. Deprotonation of the acyl-substituted imidazolium probably occurs rapidly after, if not during, the substitution, as the calculated aqueous pKa for the substitution product is estimated to be 2.86. Bender and Turnquist concluded20 from the results of their kinetics study of the imidazole-catalyzed hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl acetate that either scenario is plausible. An imidazolium cation forms a complex with the hemithioacetal oxygen through hydrogen bonding and/or ion pairing, finally protonating the alkoxide to give the first intermediate, I1. The subsequent transition is marked by the loss of the thioate leaving group, which may or may not be protonated prior to leaving, to give the experimentally observed intermediate, I2. From the production of the acyl-substitution product, both pathways undergo analogous chemical transitions, beginning with an SN2 attack on the carbonyl by methanol/methoxide. Along the unsubstituted pathway (Fig. 2), acyl substitution occurs with the thioate as the leaving group, while in the substitution pathway, the leaving group is an imidazolium that must be protonated prior to leaving. While the transitions involving the thioate leaving group are energetically accessible to the system, ions are not well solvated in polar aprotic solvents such as acetonitrile, and the thioate, with a pKa in DMSO of 15.3,21 should be expected to readily abstract a proton from imidazolium cation.

Transition state analysis

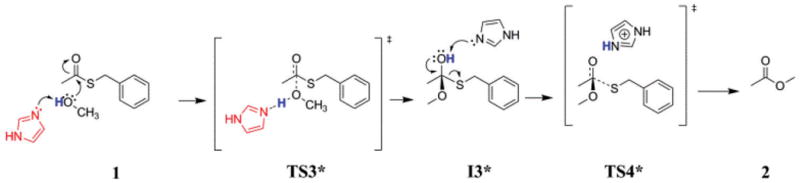

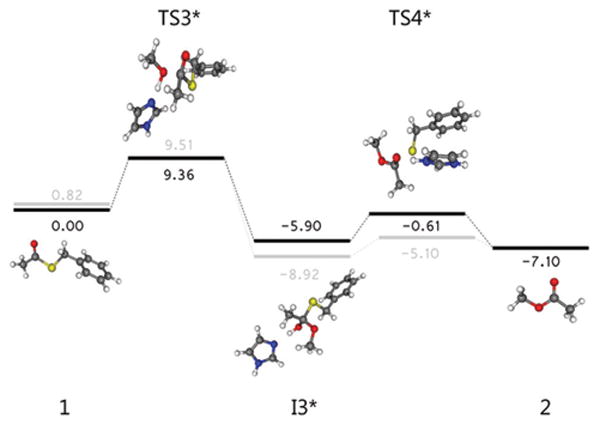

The zero-point vibrational energies (ZPVE) for the structures along the acyl substitution pathway were plotted with respect to the ZPVE of the initial system and are shown in Fig. 3. The largest energy barrier along this pathway, at 12.05 kcal mol−1 above the reference energy, lies at TS1, where an incoming imidazole attacks the carbonyl carbon in the first transition associated with acyl substitution of the thioester. In this transition state, an imidazole was not included to stabilize the forming alkoxide oxygen, but is estimated to confer 2–3 kcal mol−1 in stabilization to the complex (from calculations of the I2 structure with and without complexed imidazole – this is described in more detail in the Discussion section). Adjusting for the effect of imidazole stabilization places the activation energy on par with the next largest energy barrier of 9.51 kcal mol−1 above the reference energy at TS3, where a concerted deprotonation and nucleophilic attack of the acyl-substituted intermediate takes place with a scaled imaginary frequency of 627.6 cm−1. The overall energetic barrier that must be overcome following this reaction pathway, then, is 14.8 kcal mol−1.

Fig. 3.

Optimized geometries and scaled zero-point vibrational energies relative to that of the starting structure along the acyl substitution pathway, with energies in kcal mol−1 (light gray bars reference the energies along the unsubstituted pathway).

The relative ZPVE's for structures along the unsubstituted pathway are shown in Fig. 4. The highest energy barrier along this pathway lies at TS3*, which is the equivalent transition in the substitution pathway, TS3, corresponding to the concerted deprotonation of the alcohol with attack on the carbonyl, with a scaled imaginary frequency of 660.3 cm−1. The energy associated with this transition is 9.36 kcal mol−1 above the reference energy, and only 0.15 kcal mol−1 below that of TS3. This small energy difference is within the reported error of 0.2 kcal mol−1 for transition state energies calculated using our model chemistry and should thus be considered as energetically equivalent to the corresponding transition along the substitution pathway and the approximate activation energy for both pathways.

Fig. 4.

Optimized geometries and scaled zero-point vibrational energies relative to that of the starting structure along the unsubstituted pathway, with energies in kcal mol−1 (light gray bars reference the energies along the acyl substitution pathway).

Transition state energies were lowered substantially when imidazolium cations were allowed to form complexes with the transitional carbonyl/alkoxide oxygens. The energies of the intermediates were lowered as well, with imidazolium cations protonating the alkoxides and remaining in complex with the resulting tetrahedral intermediates. The imidazolium cation in complex with the acyl substitution product, I2, offers approximately −3 kcal mol−1 of stabilization over I2 alone in continuum solution. Transition states corresponding to the serine hydroxyl attack on the carbonyl, TS3 and TS3*, could not be resolved until an additional imidazole was included to deprotonate the hydroxyl in a concerted mechanism (Fig. 5). Transition state calculations for methoxide attack on 1 in both the gas phase and in continuum solvation consistently failed to converge or yielded higher order saddle points that could not be resolved to first order points on the potential mean force (PMF) surfaces.

Fig. 5.

Transition state geometry for the acyl substituted structure (TS3) showing the deprotonation of methanol (representing serine) by imidazole in concert with attack on the carbonyl by methoxide.

Following the electronic energies along the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) of the two pathways, the unsubstituted pathway is a slightly more energetically-favorable route, with an activation energy at TS3* of 8.97 kcal mol−1 above the energy of the initial system versus 9.50 kcal mol−1 for TS3 (Fig. 6). The activation energy difference between the two transitions is only 0.53 kcal mol−1, which becomes a difference of only 0.15 kcal mol−1 when corrected for vibrational contributions, within the margin of error for the method. Given that the energy difference between the two pathways is negligible and the substitution product is observed experimentally, cyclization should be expected to proceed along both pathways.

Fig. 6.

Activation energies for transition states TS3 and TS3* from IRC calculations, relative to the energy of the starting structure, showing a slightly higher energy of activation for the acyl substituted structure, but leading to a more stable product.

In order to explore the possibility that pyridine, the other aromatic nitrogenous heterocycle in the series of bases investigated experimentally, might also participate in a concerted deprotonation and nucleophilic attack, but perhaps with a higher activation energy, we performed a transition state calculation with pyridine replacing imidazole as the base deprotonating methanol. The transition state geometry for TS3* was used as the starting geometry for the calculation of the transition state with pyridine. The resulting transition state geometry is nearly identical to that observed in TS3* (Fig. 7) and the transition corresponding to the imaginary frequency (646.2 cm−1) shows the same concerted deprotonation of methanol as it attacks the carbonyl carbon. Interestingly, the transition state energy is only 0.76 kcal mol−1 higher than that of TS3*, suggesting cyclization should occur as readily using pyridine as imidazole. As it does not, our calculations suggest that pyridine, with a conjugate acid pKa of 5.3, should also act as a base to deprotonate the hydroxyl. We expect that, in aprotic solvent, pyridine is not protonated to a sufficient degree to act as a proton donor to the intermediate alkoxides or to the leaving groups in the final transitions, and thus cannot effectively catalyze cyclization.

Fig. 7.

Transition state geometry for the structure corresponding to TS3* using pyridine in place of imidazole showing the deprotonation of methanol (representing serine) by pyridine in concert with attack on the carbonyl by methoxide.

In a basic environment, no such stabilization could occur since the pKa's of the alkoxide intermediates are significantly higher than those of the bases used in the study. The pKa of the first intermediate following acyl substitution has a predicted aqueous pKa of 11.8, with the imidazole moiety having a pKa of 6.3 (this structure is partially protonated in mildly acidic solution). After the attack on the carbonyl by serine (methanol), the predicted aqueous pKa of the intermediate alkoxide is 13.3 for the unsubstituted pathway, but 10.1 for the intermediate alkoxide along the substituted pathway. In both cases, the alkoxide is more basic than imidazolium cation and should readily abstract a proton from imidazolium. The proportion of pyridine's conjugate acid, however, is exceedingly small in basic solution and is unlikely to stabilize the intermediates through protonation.

Discussion

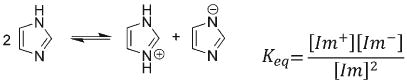

Imidazole has been reported in the literature as an acyl transfer catalyst, yet the precise mechanism of its participation has not been described in detail. From transition state analysis, we observed very similar activation energies between the two reaction pathways, indicating no significant energetic preference for acyl substitution in the overall reactions of the model structures. The key steps in the mechanism of catalysis of acyl substitutions by imidazole must lie in the concerted deprotonation by imidazole and SN2 attack on the carbonyl by the nucleophile and in the ability of imidazole to protonate intermediates and leaving groups. Imidazole is amphoteric and acts as an aqueous buffer in high concentrations. In aprotic solvent, however, imidazole must act as a buffer to itself, being the sole proton donor, as represented in the following equilibrium expression (eqn (1)).

|

(1) |

pKa values for imidazolium are available in DMSO21,22 (with a dielectric constant of ε = 47.2, versus that of acetonitrile, ε = 36.6), which we may use to approximate the pKa in acetonitrile. The pKa of protonated imidazolium cation is reported as 6.37, while that of the anion is 18.6. The reported pKa values of methanol and ethanol are approximately 29 in DMSO, indicating neutral imidazole as the primary proton source in our system, which yields an associated imidazolium cation concentration of ∼1 × 10−9 M at an equilibrium concentration of imidazole of 1 M. The higher than catalytic concentration of imidazole required to catalyze this cyclization has also been reported in the literature.20 Suchy et al. report16a that 2 equivalents of imidazole are required for their imidazole-catalyzed formylation reaction to proceed within a reasonable period of time. Acting as both a base and an acid, imidazole may require some minimum concentration to establish an equilibrium of the free base and the conjugate acid in order to effectively catalyze these acyl substitution reactions. In the aprotic media used in this study, imidazole needs to act as a proton donor to both the alkoxide intermediates and to the leaving groups, in addition to stabilizing transition states through hydrogen bonding or ion pairing. It is expected, therefore, that relatively large quantities of imidazole should be required to produce sufficient concentrations of the protonated specie to act as proton donor to the leaving groups and transition states in both cyclization pathways. In addition, an imidazole concentration of 1 M corresponds to a concentration range observed to yield a pronounced downfield 1H NMR shift for the imidazole N proton (from δ = 10.4 ppm at 0.17 M to δ = 12.75 ppm in CDCl3), as a result of extensive intermolecular imidazole– imidazole hydrogen bonding. It is therefore possible that the concentration of imidazole required to catalyze the cyclization of this peptide is dependent in some way upon the establishment of a hydrogen-bonded imidazole network surrounding the reactive sites of the peptide.

It is certainly interesting that the nucleophilic attacks on the carbonyls in TS3 and TS3* involve a concerted deprotonation of the serine (methanol) hydroxyl, which has an aqueous pKa of approximately 13, by imidazole, with an aqueous pKa of ∼7. Precedence for this departure from expected behavior in bulk solution is, nonetheless, found in nature. Many enzymatic hydrolysis reactions involving imidazole, such as those catalyzed by the phospholipases and serine proteases proceed via a bifunctional mechanism, in which imidazole, in the form of the amino acid histidine, acts as both a base and an acid. The apparent pKa of the His57 imidazole in complexes of chymotrypsin with peptidyl trifluoromethyl ketones17c has been shown to range from 10–12, very near the pKa of serine. Upon closer inspection, transition states TS3 and TS3* follow essentially the same mechanism utilized by the catalytic triads of the serine proteases, such as chymotrypsin and subtilisin, to cleave peptide chains. By the accepted mechanism, the catalytic sites of these enzymes generate a serine (Ser195) side chain oxyanion in situ through a coupled proton transfer to the imidazole of a neighboring histidine (His57) side chain.18 As the anion is formed, it acts as a nucleophile, attacking the amide carbonyl to form a hemiacetal alkoxide intermediate. Peptide cleavage is achieved by formation of a serine-peptide ester that is hydrolyzed in subsequent steps, with re-protonation of serine by the histidine imidazole. This is analogous to the mechanism of cyclization in our system, suggesting strongly that the same concerted deprotonation and nucleophilic attack that occurs in TS3* is likely the same transition that occurs in these catalytic triads. The mechanism for the initial step associated with peptide cleavage is generally depicted in textbooks18 showing the electron flow that implies a concerted process, our results show, in chemical detail, how this mechanism proceeds in concert.

Methods

Experimental methods

Macrolactonization of the linear peptide thioester, Ac-SAFYG-SCH2ϕ, was carried out at a concentration of 1 mM in anhydrous acetonitrile with varying amounts of imidazole added to promote cyclization at room temperature. Aliquots of reaction mixture were evaluated by LC-MS every 24 h from initiation to determine the extent of the cyclization.

Computational methods

Fragment structures representing the larger peptides along both reaction pathways were geometry optimized using AM123 in MOE24 2009.10. The putative transition states were constructed as described below and minimized to first-order saddle points with Gaussian25 09 using density functional theory26 (DFT). The M06-2X hybrid functional27 with the 6-31+G(d,p) basis set and the SMD28 polarizable continuum solvation model using acetonitrile solvent parameters were also used. The Synchronous Transit-Guided Quasi-Newton (STQN) method29 employed in the QST3 procedure in Gaussian was used to locate the quadratic region around the transition state, then to optimize to the saddle points using an eigenvector-following algorithm. Frequency calculations were used to confirm transition states as first-order saddle points on the surface representing the potential of mean force by frequency calculations, followed by inspection of imaginary frequencies. Further confirmation was sought through intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC)30 calculations. Zero-point vibrational energies (ZPVE) from the frequency calculations for all points along both pathways were scaled using a factor (0.97) described in the literature31 for the same functional and basis set and plotted relative to the energies of species in the stoichiometric equation. Calculations of aqueous pKa were performed using the pKa prediction module in MarvinSketch32 using 2D input structures.

Although transition state analysis is typically performed on structures in the gas phase, transitions observed in the gas phase may not correspond to first-order saddle points for solvated structures. The solvation potential energy surface, or potential of mean force (PMF), lies below the gas phase potential energy surface, but does not necessarily have the same topology:33 van der Waals complexes that form between two species due to complementary partial charges or dipoles that represent local energetic minima in the gas phase are not local minima on the PMF surface, due to already extant interactions with the solvation field. To model the solution chemistry as closely as possible, transition states were determined using the polarized continuum model with integral equation formalism (IEF-PCM)34 method using radii and terms from the SMD28 solvation model. This model, which uses atomic surface tension terms to model cavitation, dispersion, and solvent rearrangement effects, is applicable to solvents of any dielectric since solvent properties were modeled in the training process. Since zero-point energies were used in our energetic analysis of the reaction pathways, some consideration was given the effect of implicit solvation on calculated vibrational frequencies (and hence, vibrational energies), since translations, rotations and vibrations tend to coordinate as librations in solution. Ribeiro et al. report35 that vibrational contributions to free energy are generally insensitive to whether they are calculated in the gas phase or using implicit solvation, with the differences in the vibrational contributions to the free energy between the two phases amounting to a mean unsigned error of approximately 0.2 kcal mol−1 for a diverse set of neutral and ionic molecules. Since explicit imidazoles were also included in transition state and intermediate complexes in conjunction with implicit solvation, the method is similar to the cluster-continuum36 method described by Pliego et al.

In our DFT study we used the M06-2X hybrid meta-GGA (generalized gradient approximation37) functional,27 which is a meta exchange-correlated functional with 54% HF exchange that is reported to give good results for activation energies, with low average mean unsigned errors for charge transfer complexes, proton and heavy atom transfers, and nucleophilic substitutions. It is described as the most accurate method for thermochemistry and kinetics across a number of evaluated databases.27 Transition state input structures were set up to follow a Bürgi–Dunitz trajectory38 for nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl at angles of approximately 105°. Liotta et al.39 report that, for nucleophilic attacks on carbonyls in general, the softer the nucleophile, the greater is the deviation of the approach angle from 90° whereas the harder the nucleophile, the closer the approach angle comes to 90°.39 The resulting transition state geometries, proceeding along their IRC trajectories, were in good agreement with the general description of the transition geometry, wherein, as the nucleophile moves closer to the carbonyl carbon, the carbon moves further out of the RR′C=O plane.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the side-chain to C-terminal cyclization of the peptide Ac-SAFYG-SCH2ϕ was achieved experimentally through the use of imidazole as a cyclization catalyst. However, good yields of cyclic product were not obtained until concentrations of imidazole above what is considered catalytic quantities were added. Not until imidazole concentration approached 1 M did the remaining unreacted peptide disappear from the isolated product mixture to give a 90% relative yield of the cyclic depsipeptide. Using transition state analysis of two proposed reaction pathways, we observed that, in what are the rate-limiting transition along both pathways, imidazole catalyzes cyclization through a concerted mechanism wherein imidazole removes a proton from an alcohol, forming an alkoxide, which, in turn, acts as a nucleophile toward an ester carbonyl. The concerted deprotonation by imidazole and SN2 nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl observed in the calculated cyclization transitions of both pathways thus represents the mechanism by which imidazole is able to deprotonate hydrolizable species with much higher pKa's. Furthermore, we anticipate this reaction mechanism is generalizable to other types of nucleophilic acyl additions and substitutions involving imidazole, including enzymatic systems. The chemical participants in the described transition form a system similar to that utilized by the catalytic triads of serine proteases to cleave peptide bonds, which likely follow the same mechanism, with histidine imidazoles deprotonating serine hydroxyls in concert with nucleophilic attack on bound peptide carbonyls, the first step of peptide cleavage subsequent to binding.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the State of Florida, Executive Office of the Governor's Department of Economic Opportunity and funded, in part, by NIDA DA031370 to RAH. KM acknowledge PAPIIT grant IA200513-2. The authors also thank ChemAxon for providing MarvinSketch and Dr. Ralph Puchta for his helpful suggestions with transition states calculations.

References

- 1.Baumann HI, Keller S, Wolter FE, Nicholson GJ, Jung G, Süssmuth RD, Jüttner F. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1611–1615. doi: 10.1021/np0700873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz LJ, Cuevas C, Cañedo LM, Giralt E, Albericio F. J Org Chem. 2005;71:3339–3344. doi: 10.1021/jo051601h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armishaw CJ. Toxins. 2010;2:1471–1499. doi: 10.3390/toxins2061471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin J, Kimura R, Woo YH, Camarero J. Amino Acids. 2010;38:1313–1322. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0338-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Doss M, Ruchala P, Tecle T, Gantz D, Verma A, Hartshorn A, Crouch EC, Luong H, Micewicz ED, Lehrer RI, Hartshorn KL. J Immunol. 2012;188:2759–2768. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dewan V, Liu T, Chen KM, Qian ZQ, Xiao Y, Kleiman L, Mahasenan KV, Li CL, Matsuo H, Pei DH, Musier-Forsyth K. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:761–769. doi: 10.1021/cb200450w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machado A, Fazio MA, Miranda A, Daffre S, Machini MT. J Pept Sci. 2012;18:588–598. doi: 10.1002/psc.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahiya R, Gautam H. Marine Drugs. 2011;9:71–81. doi: 10.3390/md9010071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentilucci L, Marco RD, Cerisoli L. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:3185–3203. doi: 10.2174/138161210793292555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairlie DP, Abbenante G, March DR. Curr Med Chem. 1995;2:654–686. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pakkala M, Weisell J, Hekim C, Vepsäläinen J, Wallen E, Stenman UH, Koistinen H, Närvänen A. Amino Acids. 2010;39:233–242. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Weltrowska G, Berezowska I, Lemieux C, Chung NN, Wilkes BC, Schiller PW. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2010;75:182–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Purington LC, Pogozheva ID, Traynor JR, Mosberg HI. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7724–7731. doi: 10.1021/jm9007483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Davies JS. J Pept Sci. 2003;9:471–501. doi: 10.1002/psc.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Eichler J, Houghten RA. Protein Pept Lett. 1997;4:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Houghten RA, Pinilla C, Appel JR, Blondelle SE, Dooley CT, Eichler J, Nefzi A, Ostresh JM. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3743–3778. doi: 10.1021/jm990174v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dooley C, Chung N, Wilkes B, Schiller P, Bidlack J, Pasternak G, Houghten R. Science. 1994;266:2019–2022. doi: 10.1126/science.7801131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Houghten R, Dooley C, Appel J. AAPS J. 2006;8:E371–E382. doi: 10.1007/BF02854908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Lebl M. J Comb Chem. 1999;1:3–24. doi: 10.1021/cc9800327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cwirla SE, Peters EA, Barrett RW, Dower WJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87:6378–6382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Scott J, Smith G. Science. 1990;249:386–390. doi: 10.1126/science.1696028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Devlin J, Panganiban L, Devlin P. Science. 1990;249:404–406. doi: 10.1126/science.2143033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Gallop MA, Barrett RW, Dower WJ, Fodor SPA, Gordon EM. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1233–1251. doi: 10.1021/jm00035a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gentilucci L, Cardillo G, Tolomelli A, DeMarco R, Garelli A, Spampinato S, Sparta A, Juaristi E. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:517–523. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Li Y, Giulionatti M, Houghten RA. Org Lett. 2010;12:2250–2253. doi: 10.1021/ol100596p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fang GM, Cui HK, Zheng JS, Lui L. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1061–1065. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Suchý M, Elmehriki AAH, Hudson RHE. Org Lett. 2011;12:3952–3955. doi: 10.1021/ol201475j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mandell L, Moncrief JW, Goldstein JH. Tetrahedron. 1963;19:2025–2030. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(63)85016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Bachovchin WW, Wong WYL, Farr-Jones S, Shenvi AB, Kettner CA. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7689–7697. doi: 10.1021/bi00420a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liang TC, Abeles RH. Biochemistry. 1987;26:7603–7608. doi: 10.1021/bi00398a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lin J, Cassidy CS, Frey PA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11940–11948. doi: 10.1021/bi980278s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedstrom L. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4501–4523. doi: 10.1021/cr000033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kar T, Scheiner S. Int J Quantum Chem. 2006;106:843–851. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bender ML, Turnquest BW. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:1652–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bordwell FG. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:456–463. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crampton MR, Robotham IA. J Chem Res. 1997:22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewar MJS, Zoebisch EG, Healy EF. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3902–3909. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MOE. Chemical Computing Group; Montreal: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino GZJ, Sonnenberg JL, Hada MEM, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JJA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. GAUSSIAN 09 (Revision A.01) Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohn W, Sham LJ. Phys Rev. 1965;140:A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Theor Chem Acc. 2008;120:215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J Phys Chem B. 2009;118:6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Peng C, Schlegel HB. Isr J Chem. 1993;33:449. [Google Scholar]; (b) Peng C, Ayala PY, Schlegel HB, Frisch MJ. J Comput Chem. 1996;17:49. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukui K. Acc Chem Res. 1981;14:363–368. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alecu IM, Zheng J, Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. J Chem Theor Comput. 2010;6:2872–2887. doi: 10.1021/ct100326h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MarvinSketch 5.6.0.0. 2011 Chemaxon Ltd ( http://www.che-maxon.com)

- 33.Cramer CJ. Implicit Models for Condensed Phases. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Barone V. J Chem Phys. 2002;117:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ribeiro RF, Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:14556–14562. doi: 10.1021/jp205508z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pliego JR, Riveros JM. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:7434–7439. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bürgi BH, Dunitz JD, Shefter E. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:5065–5067. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liotta CL, Burgess EM, Eberhardt WH. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:4849–4852. [Google Scholar]