Abstract

CXCL12/SDF-1 dynamically regulates hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) attraction in the bone marrow (BM). Circadian regulation of bone formation and HSC traffic is relayed in bone and BM by β-adrenergic receptors (β-AR) expressed on HSCs, osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem / progenitor cells. Circadian HSC release from the BM follows rhythmic secretion of norepinephrine (NE) from nerve terminals, β3-AR activation and Cxcl12 downregulation, possibly due to reduced Sp1 nuclear content. Here, we show that β-AR stimulation in stromal cells causes Sp1 degradation, partially mediated by 26S proteasome. Inverted trends of circulating hematopoietic progenitors and BM Cxcl12 mRNA levels change acutely after light onset, shown to induce sympathetic efferent activity. In BM stromal cells, activation of β3-AR downregulates Cxcl12, whereas β2-AR stimulation induces clock gene expression. Double-deficiency in β2- and β3-ARs compromises enforced mobilization. Therefore, β2- and β3-ARs have specific roles in stromal cells and cooperate during progenitor mobilization.

Keywords: β-adrenergic receptors, bone marrow stromal cells, circadian, clock, CXCL12/SDF-1, hematopoietic progenitor mobilization

INTRODUCTION

Circadian oscillations are sustained by the asynchronous expression of “clock genes” that interact in feedback loops1 and that are also regulated by post-transcriptional, post-translational, and epigenetic mechanisms.2 The central pacemaker in the brain, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), regulates circadian oscillations of multiple tissues through sympathetic efferent activity. In the liver3 or the bone,4 adrenergic activity resets the peripheral clock by inducing the expression of the clock gene Per1. In the bone, this effect is transduced by the β2-AR, the only β-AR expressed by the osteoblast.5 However, other bone marrow (BM) stromal cells also express the β3-AR, which regulates physiological circadian release of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to the bloodstream.6 The possible implications of the β3-AR in multiple tissues have not been investigated, possibly due to its low expression level, even in adipocytes, where it is known to regulate lipolysis and thermogenesis and to signal distinctly from the β1- and β2-ARs.7

CXCL12/SDF-1 has emerged as a critical chemokine for the migration of HSCs, as shown by pioneer studies.8-10 In addition, CXCL12 is the only known chemokine capable of directed migration of HSCs.11 Indeed, the disruption of CXCL12 interaction with CXCR4, its cognate receptor, using specific small CXCR4 inhibitor molecule is sufficient to induce HSC mobilization from the BM to the peripheral circulation.12 While circadian release of norepinephrine (NE) by nerve terminals in the BM leads to rhythmic Cxcl12 downregulation, possibly via reduced Sp1 nuclear content in stromal cells,6 the expression of CXCR4 in HSCs also follows circadian oscillations,13 suggesting that a coordinated expression of secreted molecules and ligands regulates the steady-state traffic of HSCs. In addition, NE and epinephrine-mediated activation of β2-ARs on human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors promotes their migration, proliferation, and mobilization.14

Previous studies have shown that exposure to light in rodents acutely induces sympathetic efferent activity and suppresses the parasympathetic tone in various organs, an effect mediated by the SCN. Light exposure acutely induces sympathetic activity of the pancreatic, hepatic, splenic, adrenal and renal branches of the splanchnic nerve and suppressed parasympathetic efferent activity of pancreatic, hepatic and gastric branches of the vagus nerve in rats.15,16 In mice, the increase of the renal sympathetic nerve activity, arterial blood pressure and heart rate immediately after the onset of light was accompanied by a rapid suppression of the gastric vagal parasympathetic nerve activity.17 Further, the SCN-mediated induction of sympathetic activity by light in the splanchnic nerve directly stimulated peripheral clock gene expression in the adrenal cortex, leading to enhanced secretion of glucocorticoid hormones.18

In this study we have examined in more detail the specific roles of β2- and β3-ARs in the circadian regulation of the expression of Cxcl12 and clock genes in stromal cells, as well as in G-CSF-induced mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors. These results suggest that although β2- and β3-adrenergic receptors on stromal cells elicit specific biological responses in homeostasis, they cooperate during progenitor mobilization enforced by G-CSF.

RESULTS

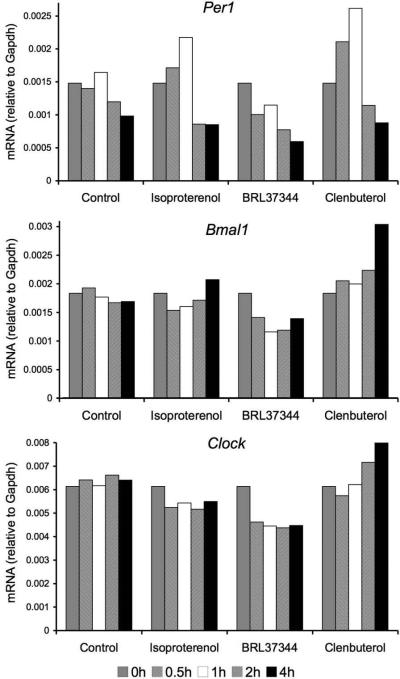

The onset of light triggers Cxcl12 mRNA downregulation

Our previous studies have shown an oscillatory pattern of Cxcl12 mRNA levels in the BM closely (< 4h) followed by a similar oscillation of CXCL12 protein content in the BM extracellular fluids, both inversely correlated with the number or hematopoietic progenitors detectable in the peripheral circulation.6 In these studies, blood and BM samples were harvested starting at Zeitgeber time (ZT) 1, 5, 9, 13 and 17. We were intrigued by the close correlation between Cxcl12 transcripts and protein levels in the BM, and by the fact that the most pronounced change in BM Cxcl12 expression appeared to occur acutely after the onset of light. Therefore, we have evaluated in more detail the changes in BM Cxcl12 and blood progenitor counts by more frequent sampling around ZT 0 in animals kept in standard 12 hour light-12 hour darkness (LD) conditions. In these experiments, circulating progenitors and BM Cxcl12 mRNA levels were sampled in C57BL/6 mice at ZT 21, ZT 23, ZT 0, ZT 1 and ZT 3 (n = 8 - 9 animals per time point). In agreement with our previous studies, the results of these experiments show a sharp rise in the number of CFU-C at ZT 1 together with an inverted trend in Cxcl12 mRNA levels (Fig. 1A). The changes in CFU-C and Cxcl12 between peak and trough were statistically significant. This observation is consistent with the release of NE in the BM microenvironment triggered by light onset, leading to rapid Cxcl12 downregulation.

Figure 1.

Circulating CFU-Cs and bone marrow Cxcl12 mRNA levels around ZT0 in mice kept in LD. From ZT21-3, bone marrow Cxcl12 mRNA levels (in red) exhibited robust oscillations in antiphase with fluctuations in circulating progenitors (in blue). Unpaired, two-tailed t-test of samples harvested at different time points compared to the peak (*) or the trough (§). Dark rectangle indicates darkness hours; white rectangle represents light hours. *, § p < 0.05; **, §§ p < 0.01. ***, §§§ p < 0.001. n = 8 - 9 animals per time point. One-way ANOVA (for Cxcl12, F4,36 = 9.632, p < 0.0001; for CFU-C, F4,33 = 5.197, p = 0.0023) followed by post hoc analyses for linear trend (Cxcl12, p = 0.0023; CFU-C, p = 0.0002).

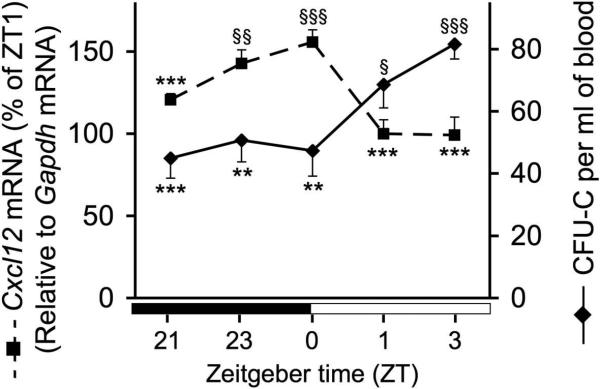

Activation of β2-, but not β3-adrenergic receptors induces clock gene expression in stromal cells

Previous studies have shown that peripheral oscillators, such as the liver3 or the osteoblast,4 are periodically reset through induction of the clock gene Per1 following β2-AR activation. Therefore, we have examined whether the sympathetic nervous system might also regulate the peripheral clock in the BM microenvironment by studying clock gene expression in synchronized cultures of the BM stromal cell line MS-5 after treatment with β-adrenergic agonists. We have found that, like in hepatocytes and osteoblasts,3,4 treatment with the non-selective β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol rapidly (within 30 min) induced Per1, followed by upregulation of Bmal1 and Clock ~ 3 h later. The same effect was observed when using a selective β2-adrenergic agonist (clenbuterol), but not with a selective β3-adrenergic agonist (BRL37344). These results extend our previous observations6 suggesting distinct signals downstream of β2- and β3-AR activation in the BM microenvironment.

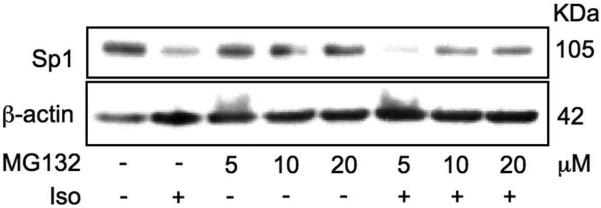

β-AR-induced Sp1 degradation in stromal cells is partially mediated by the 26S proteasome

Our previous studies have suggested that β-ARs on stromal cells might regulate Cxcl12 transcription by affecting the nuclear content of Sp1 transcription factor.6 In addition, other studies have shown that the HSC-mobilizing agent lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces Sp1 dephosphorylation and degradation,19 suggesting that Sp1 degradation might be required for HSC mobilization. Interestingly, LPS-induced Sp1 degradation is not mediated by the 26S proteasome, but by a trypsin-like serine protease.20 We have examined whether the reduction in Sp1 nuclear content triggered by β-AR stimulation was caused by Sp1 protein degradation, and if so whether the 26S proteasome was involved in this process. For this purpose we pre-incubated MS-5 cells with a proteasome inhibitor (MG132) before stimulation with a non-selective β-AR agonist (isoproterenol). Pre-incubation of the cells with MG132 resulted in a partial, dose-dependent prevention of nuclear Sp1 degradation (Figure 3), suggesting that activation of β-ARs on stromal cells acutely induces Sp1 degradation, only partially mediated by the 26S proteasome.

Figure 3.

Proteasome inhibition reduces Sp1 degradation following MS-5 cells stimulation with isoproterenol. MS-5 cells were pre-incubated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (5 - 20 βM, 30 min) and treated for 2 h with isoproterenol (Iso, 100 βM), in the presence or absence of MG132. Representative Western blot from 3 independent experiments.

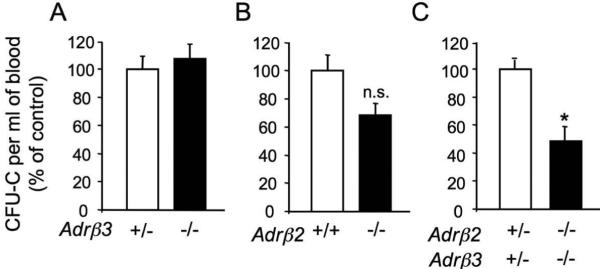

G-CSF-induced progenitor mobilization requires cooperation of β2- and β3- adrenergic receptors

Previous studies have shown that granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), a potent HSC mobilizer, induces a dramatic suppression of osteoblast function and an acute downregulation of Cxcl12 in the BM,10,21-24 in a manner that required an intact sympathetic nervous system23. Although the administration of a β2-AR agonist did not induce mobilization by itself, it could rescue in part the mobilization defect of mice deficient in NE synthesis (dopamine β-hydroxylase-deficient) and it enhanced G-CSF-induced mobilization in wild-type mice23. However, we and others have not found any role for β2-adrenergic signaling in Cxcl12 regulation. To test the individual roles of the β2-βand β3-AR in enforced mobilization, we examined G-CSF-induced progenitor mobilization in animals deficient in either β2-, β3-, or both ARs. We have found that unlike the deficiency of single β-ARs, the absence of both β2- and β3-ARs significantly compromised mobilization to the bloodstream (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

G-CSF-induced mobilization requires cooperation between β2- and β3-adrenergic receptors. β3-AR +/- and -/-, β2-AR +/+ and -/-, β2,β3-AR +/- and double K.O. littermates were injected with G-CSF (250 μg/kg/day, 8 divided doses every 12 h, i.p.). The number of circulating CFU-Cs was assessed 3 h after the last injection and normalized to the control group to account for strain-dependent differences in G-CSF-induced mobilization. A, n = 5; B, n = 5; C, n = 3-5. * p < 0.05, unpaired two-tail t test. Error bars indicate STD error.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have analyzed the role of β2- and β3-ARs in the BM microenvironment during G-CSF-induced HSC mobilization. NE secreted by the adrenal medulla exhibits circadian variations, peaking during the dark phase, coinciding with increased nocturnal activity in rodents.25 However, NE locally released by SNS fibers typically shows regional variability, with the sympathetic outflow to some organs being activated but to other regions unchanged or inhibited.26 In the mouse BM, sympathetic activity has not been directly measured, but has only been inferred from levels of catecholamines. In the mouse BM, NE displays a circadian rhythmicity, peaking at night.27 However, plasma or tissue levels of NE are influenced by complex kinetics including its clearance, reuptake and degradation and therefore its levels may not directly reflect SNS activity.26 Previous studies have shown that light exposure in rodents is a potent stimulus inducing sympathetic efferent activity in multiple organs.15-18 Our studies suggest that the BM microenvironment does not escape to this regulation. These data also indicate that, like in the adipose or cardiac tissues, β2- and β3-ARs on BM stromal cells have separate signaling pathways that result in distinct biological functions. Whereas activation of β2-AR, like in hepatocytes and osteoblasts,3,4 induces clock gene expression in BM stromal cells, stimulation of the β3-AR results in acute Cxcl12 downregulation, likely due to Sp1 protein degradation. Whereas mice lacking β3-AR have clear alterations in steady-state trafficking,6 β3-AR expression does not appear to be necessary when mobilization is enforced, suggesting compensatory mechanisms. Indeed, the present results indicate that both the β2- and β3-AR colaborate in this activity. One interpretation of these data is that eventhough β2-AR and β3-AR have distinct functions under homeostasis, either AR could compensate for the function of the other in stressed singly deficient animals. β3-AR is restricted to the stromal compartment, but β2-AR is expressed at high levels in both the hematopoietic and stromal compartments. Since previous data have suggested the requirement of G-CSF receptor expression on a transplantable hematopoietic cell for efficient G-CSF-induced HSC mobilization,28 a role for the β2-AR on a hematopoietic cell of the bone marrow cannot be excluded.

In summary, these results suggest that light exposure triggers Cxcl12 downregulation, likely by increasing sympathetic efferent activity in the BM. Although the β2- and β3-ARs clearly exert distinct functions, their uncovered collaboration during enforced mobilization suggests that they can compensate for each others’ function in situations of stress.

METHODS

Animals

Adrb2tm1Bkk/J29 (gift from Dr. Gerard Karsenty, Columbia University, New York), FVB/N-Adrb3tm1Lowl/J30 and the inbred FVB/NJ (Jackson Laboratories) and C57BL/6 strains (Charles River Laboratories) were used. For circadian studies around ZT 0, adult C57BL/6 male mice were used. Experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Blood and BM were harvested from mice anesthesized with isofluorane and handled carefully to monimize stress, and using a low-energy red light during the dark phase to prevent stimulation by light. From each mouse, the BM contained in one femur and one tibia was flushed with 0.5 ml Trizol (Invitrogen). MS-5 cell cultures were synchronized by serum deprivation. Cell culture, RNA extraction, quantitative real-time RT-PCR, preparation of nuclear extracts, Sp1 Western Blot, administration of G-CSF and CFU-C assay from peripheral blood have been described previously.6,23

Figure 2.

Activation of β2- but not β3-adrenergic receptors induces clock gene expression in stromal cells. Time-course study (0-4 h) of mRNA expression by quantitative real-time RT-PCR showing rapid (0.5-1 h) induction of Per1 by a non-selective β-adrenoceptor agonist (isoproterenol), a selective β2-AR agonist (clenbuterol) but not by a selective β3-AR agonist (BRL37344) (50 βM). Per1 induction was followed 3 h later by upregulation of Bmal1 and Clock.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. María García-Fernández for help with Western Blots. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 grants DK056638, HL69438) and the Department of Defence (Idea Development Award PC060271). S.M.-F. is the recipient of a Scholar Award by the American Society of Hematology. M. B. was supported by the Cooley's Anemia Foundation. P.S.F. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418:935–41. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi JS, et al. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:764–75. doi: 10.1038/nrg2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terazono H, et al. Adrenergic regulation of clock gene expression in mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6795–800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0936797100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu L, et al. The molecular clock mediates leptin-regulated bone formation. Cell. 2005;122:803–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elefteriou F, et al. Leptin regulation of bone resorption by the sympathetic nervous system and CART. Nature. 2005;434:514–20. doi: 10.1038/nature03398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendez-Ferrer S, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strosberg AD. Structure and function of the beta 3-adrenergic receptor. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:421–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiuti A, et al. The chemokine SDF-1 is a chemoattractant for human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and provides a new mechanism to explain the mobilization of CD34+ progenitors to peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 1997;185:111–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peled A, et al. Dependence of human stem cell engraftment and repopulation of NOD/SCID mice on CXCR4. Science. 1999;283:845–8. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petit I, et al. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:687–94. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright DE, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells are uniquely selective in their migratory response to chemokines. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1145–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broxmeyer HE, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1307–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas D, et al. Mobilized hematopoietic stem cell yield depends on species-specific circadian timing. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:364–6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiegel A, et al. Catecholaminergic neurotransmitters regulate migration and repopulation of immature human CD34+ cells through Wnt signaling. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1123–31. doi: 10.1038/ni1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niijima A, et al. Light enhances sympathetic and suppresses vagal outflows and lesions including the suprachiasmatic nucleus eliminate these changes in rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1992;40:155–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(92)90026-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niijima A, et al. Effects of light stimulation on the activity of the autonomic nerves in anesthetized rats. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:555–61. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90249-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mutoh T, et al. Melatonin modulates the light-induced sympathoexcitation and vagal suppression with participation of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in mice. J Physiol. 2003;547:317–32. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.028001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishida A, et al. Light activates the adrenal gland: timing of gene expression and glucocorticoid release. Cell Metab. 2005;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye X, Liu SF. Lipopolysaccharide down-regulates Sp1 binding activity by promoting Sp1 protein dephosphorylation and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31863–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye X, Liu SF. Lipopolysaccharide causes Sp1 protein degradation by inducing a unique trypsin-like serine protease in rat lungs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:243–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levesque JP, et al. Disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemotactic interaction during hematopoietic stem cell mobilization induced by GCSF or cyclophosphamide. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:187–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI15994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semerad CL, et al. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106:3020–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katayama Y, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christopher MJ, et al. Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood. 2009;114:1331–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Boer SF, Van der Gugten J. Daily variations in plasma noradrenaline, adrenaline and corticosterone concentrations in rats. Physiol Behav. 1987;40:323–8. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esler M, et al. Overflow of catecholamine neurotransmitters to the circulation: source, fate, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:963–85. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maestroni GJ, et al. Neural and endogenous catecholamines in the bone marrow. Circadian association of norepinephrine with hematopoiesis? Exp Hematol. 1998;26:1172–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu F, Poursine-Laurent J, Link DC. Expression of the G-CSF receptor on hematopoietic progenitor cells is not required for their mobilization by G CSF. Blood. 2000;95:3025–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chruscinski AJ, et al. Targeted disruption of the beta2 adrenergic receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16694–700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Susulic VS, et al. Targeted disruption of the beta 3-adrenergic receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29483–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]