Abstract

Previous research has shown that sexual minority (i.e., nonheterosexual) individuals report increased problematic substance use involvement, compared with their sexual majority counterparts. We hypothesize that feelings of an unstable sense of self (i.e., identity disturbance) may potentially drive problematic substance use. The purpose of the current study is to examine identity disturbance among sexual minorities as a potential explanatory mechanism of increased sexual minority lifetime rates of substance dependence. Measures of identity disturbance and three indicators of sexual orientation from lifetime female (n = 16,629) and male (n = 13,553) alcohol/illicit drug users in Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) were examined. Findings generally showed that the increased prevalence of alcohol dependence, illicit drug dependence, and combined alcohol/illicit drug dependence as well as a younger age of alcohol use initiation among sexual minority women was associated with elevated levels of identity disturbance. The results were consistent with a mediational role for identity disturbance in explaining the association between sexual minority status and substance dependence and were generally replicated among male sexual minority respondents. The current research suggests that identity disturbance, a predictor of substance use, may contribute to heightened risk for substance dependence among certain subgroups of sexual minority individuals.

Keywords: sexual minority, bisexuality, sexual identity, sexual orientation, alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, NESARC, identity disturbance

Empirical research suggests that nonheterosexual individuals may be at greater risk for engagement in problematic substance use behaviors compared with their exclusively heterosexual peers (e.g., Cochran, Ackerman, Mays, & Ross, 2004; Corliss, Rosario, Wypij, Fisher, & Austin, 2008; Eisenberg & Wechsler, 2003; Marshal et al., 2008; McCabe, Hughes, Bostwick, & Boyd, 2005; McCabe, Hughes, Bostwick, West, & Boyd, 2009; Midanik, Drabble, Trocki, & Sell, 2007). Researchers (e.g., Savin-Williams, 2001a) have argued for a better understanding of the predictors of these substance-related disparities. The current study seeks to provide evidence that substances may be used, in part, by sexual minority individuals as a means to assuage negative affect arising from identity-related stressors in a way that is consistent with negative affect pathways of substance use (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Cappell & Greeley, 1987; Cappell & Herman, 1972; Sher & Grekin, 2007).

At a global level, Marcia (1994, p. 64) defines identity as “an individual's organization of drives (needs, wishes) and abilities (skills, competence) in the context of his or her particular culture's demands (requirements) and rewards (gratifications).” In Erikson's (1968) theory of psychosocial development, the inability to develop and consolidate one's sense of identity is believed to result in identity confusion or disturbance. Identity disturbance is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) as a “markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Although considered a core feature of personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Clarkin, Lenzenweger, Yeomans, Levy, & Kernberg, 2007; Crawford, Cohen, Johnson, Sneed, & Brook, 2004; Kernberg, 1984), identity disturbance has been examined in nonclinical samples as well (e.g., Vartanian, 2009). Indeed, Campbell and colleagues (1996) constructed a self-report measure, intended for use with the general population, which assesses the extent to which individuals’ sense of self is “well defined, coherent, and stable” (the Self-Concept Clarity Scale; SCCS).

Identity Disturbance and Substance Use

Few empirical studies have sought to characterize the relation between identity disturbance and psychosocial functioning (see Jorgensen, 2006 for a review). Cassel (1990) argued that a failure to achieve identity integration would result in a “void” that would cause persons to turn to alcohol, cigarettes, and illicit drugs (see also Wheelin, 1953). Moreover, Jorgenson (2006) posited that alcohol use is one way that persons with generalized identity disturbance “ward off painful feelings of emptiness and meaninglessness” (p. 631). Consistent with this sentiment, researchers have recently begun to uncover associations between identity disturbance and elevated levels of substance use and associated problems in both clinical (Becker, McGlashan, & Grilo, 2006; Rounsaville et al., 1998) and nonclinical samples (Corte & Zucker, 2008; Stepp, Trull, & Sher, 2005).

Findings have shown that identity disturbance, specifically conceived of as an indicator of personality disorders, is associated with substance use and misuse (Stepp, Trull, & Sher, 2005; see also Becker, McGlashan, & Grilo, 2006; Dulit, Fyer, Haas, Sullivan, & France, 1990; Hatzitaskos, Soldatos, Kokkevi, & Stefanis, 1999; Rounsaville et al., 1998; Skinstad & Swain, 2001). In the literature examining identity disturbance in nonclinical samples, a longitudinal study examining children of Hispanic immigrants found that increasing identity confusion scores over time were predictive of earlier initiation into alcohol and cigarette use (Schwartz, Mason, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2008; see also Rose, Rodgers, & Small, 2006; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Weisskirch, & Rodriquez, 2009), whereas decreasing scores were related to later initiation of use. Providing indirect evidence for our hypotheses, a lack of self-concept clarity (Campbell et al., 1996) has been shown to relate to important correlates of problematic substance use, including higher endorsements of using alcohol/illicit drugs to cope with life stressors (Smith, Wethington, & Zhan, 1996), lower levels of self-esteem and internal state awareness (i.e., private self-consciousness), as well as higher levels of neuroticism, rumi-nation, and self-reflection. Previous empirical findings, therefore, have provided suggestive evidence supporting an association between an incoherent or unstable sense of self and problematic substance involvement.

Identity Disturbance in Sexual Minorities

There are multiple sources of evidence to suggest that sexual minorities may be likely to endorse higher levels of identity disturbance, compared to their sexual majority counterparts.

First, as mentioned previously, theorists have posited that identity disturbance may be inherent during identity development and integration. Indeed, sexual identity development and questioning is presumed to relate to heightened reports of identity confusion (Cass, 1984; Troiden, 1989; Yarhouse & Tan, 2004). Sexual identity is defined as individuals’ beliefs regarding “their biological sex, gender, orientation, behaviors, and values” (Yarhouse & Tan, 2004; p. 3). According to Cass’ model (1984), during sexual identity development, aspects of an individual's sexual identity may be experienced as “incongruent” (Yarhouse & Tan, 2004; p. 10) with the individual's previous conceptualization of a consistent and stable sexual identity. Schulenberg and Maggs (2002; see also Hatzenbuehler, 2009) have asserted that as individuals experience stress associated with the awareness or adoption of alternative identities (e.g., bisexual, gay/lesbian), they may become more susceptible to known predictors of substance use. Consistent with this, researchers (e.g., Rose, Rodgers, & Small, 2006; Russell, 2006; Ziyadeh et al., 2007) have suggested that heightened substance use by sexual minority individuals may be attempts to escape from sexual identity-related stressors.

Second, according to Peppard (2008), individuals who have suffered childhood abuse are at risk for experiencing identity disturbance (see also Wilkinson-Ryan & Westen, 2000; c.f. Oldham, Skodol, Gallaher, & Kroll, 1996). As a group, sexual minority individuals report a greater frequency of experiences with childhood abuse and victimization (Austin, Roberts, Corliss, & Molnar, 2008; D'Augelli, 2003; Hughes, Johnson, Wilsnack, & Szalacha, 2007; Hughes, McCabe, Wilsnack, West, & Boyd, 2010; Saewyc et al., 2006; Stoddard, Dibble, & Fineman, 2009; Wilsnack et al., 2008; c.f. Wilson & Widom, 2010) than their sexual majority peers. Given this replicable finding, in the current work we examine whether sexual minority individuals may be at greater risk for developing identity disturbance, and, in a subset of analyses, also consider the role of childhood abuse and victimization in these associations.

Current Study and Hypotheses

In the current report, we first examine whether sexual minority individuals’ rates of substance dependence diagnoses and age of alcohol use initiation can be accounted for, in part, by self-reported levels of identity disturbance. We hypothesize that sexual minority individuals will be at increased risk for lifetime substance dependence disorders as well as report younger ages of alcohol use initiation. We anticipate that elevated levels of identity disturbance symptomatology could account, in part, for these associations. We subsequently examine the influence of childhood abuse on the predicted associations. It is hypothesized that, although the presence of childhood abuse will likely be associated with both sexual minority status and substance dependence and thus could partially account for the heightened risk of identity disturbance symptoms among sexual minority individuals, there will remain an independent relation between sexual minority status and identity disturbance symptoms. Our predictions are tested using Wave 2 data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)1 – when facets of sexual orientation and identity disturbance symptoms were assessed.

Method

Participants

NESARC was a face-to-face, general population survey conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant & Dawson, 2006). Wave 2 was collected from 2004 to 2005 and included 34,653 respondents. The civilian population residing in the United States was the target population of NESARC. The unit sampling frame of NESARC was based on the Supplementary Survey from the U.S. Census Bureau (Grant & Kaplan, 2005). NESARC also included a group quarters’ sampling frame, which administered the survey to subgroups of the population with heavy substance use patterns that are not often included in general population surveys (e.g., boarding houses, nontransient hotels and motels, shelters, group homes). The data were weighted and adjusted, based on 2000 census data, to represent the U.S. civilian population (see Grant, Kaplan, Shepard, & Moore, 2003). The purpose of this manuscript was to examine a mechanism that might contribute to heightened risk for problematic substance use among sexual minorities with a history of substance use. Only lifetime drinkers (n = 29,993) and illicit drug users (n = 8,863) were retained for the current analyses, given that lifetime abstainers were not at risk for substance dependence or earlier age of alcohol use initiation.

Measures

Sexual orientation

Three questions in Wave 2 of the NESARC study were used to distinguish respondents based on reported sexual attraction, sexual behaviors, and self-identification.2 Sexual attraction was assessed by asking, “Which category best describes your feelings of sexual attraction to others?” A dummy variable distinguished participants indicating any degree of same-sex attraction (male n = 679; female n = 1,281) from those indicating only opposite-sex attractions (male n = 12,767; female n = 15,211). Sexual behaviors were assessed by asking participants, “In your lifetime, have you had sex with only males, only females, both males and females, or have you never had sex?” A dummy variable distinguished participants indicating any past same-sex sexual experiences (male n = 610; female n = 594) from participants indicating sexual experiences with only opposite-sex partners (male n = 12,666; female n = 15,678). Individuals who were unsure of the gender of their past sexual partners (n = 261) or who indicated that they never had sex (n = 373) were coded as missing. Self-identification was assessed with a single item asking participants, “Which of the categories best describes you?” A variable was created to distinguish a sexual minority self-identification [those indicating a “bisexual,” “gay/lesbian” or “unsure” (n=134) self-identification; male n = 323; female n = 374] from a sexual majority self-identification (“heterosexual”; male n = 13,134; female n = 16,137).

Theoretical (e.g., Sell, 1997) and empirical (Marshal et al., 2008; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007) distinctions between sexual self-identifications, sexual attractions, and sexual behaviors (i.e., facets of sexual orientation) have been identified in the substance use literature. In the current study, male respondents’ reports of sexual attractions and sexual behaviors were strongly correlated, φ = .57, p < .05, with similar levels of association demonstrated among their reports of sexual attractions and self-identification, φ = .62, p < .05, as well as among their reports of sexual behaviors and self-identification, φ = .62, p < .05. Among female respondents, their reports of sexual attractions and sexual behaviors were moderately-to-strongly related, φ = .52, p < .05, whereas a weaker association was found between their reports of sexual attractions and self-identification, φ = .46, p < .05. By contrast, the strongest association was shown between women's reports of sexual behaviors and self-identification, φ = .64, p < .05. Although the intercorrelations among these facets of sexual orientation are high, their level of association is not so high as to indicate that they are entirely redundant with one another. Thus, we present findings separately for each facet.

Identity disturbance

Identity disturbance was assessed in the context of other symptoms of borderline personality disorder symptoms in Wave 2 of NESARC. Lifetime occurrence of identity disturbance symptoms were assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV; Grant, Dawson, & Hasin, 2004), a fully structured diagnostic interview designed for use by experienced lay interviewers. Internal consistency and test-retest reliability of the borderline diagnosis as well as its symptoms, as assessed by the AUDADIS-IV, has been validated in previous studies (Ruan et al., 2008; Grant et al., 2008). Three items were used in the composite identity disturbance variable (α = .57).3 Items include the following: “Have you been so different with different people or in different situations that you sometimes don't know who you really are?” “Have you all of a sudden changed your sense of who you are and where you are headed?” and “Has your sense of who you are often changed depending on the situation or whom you are with?” (1 = Yes, 0 = No; Range: 0–3). Important for the current work, interviewers instructed participants to not include symptoms which occurred only when they were depressed, manic, anxious, drinking heavily, using medicines or drugs, experiencing withdrawal symptoms, or physically ill (Grant et al., 2008).

Substance use involvement

Participants’ lifetime alcohol and illicit drug dependence diagnoses were also made with the AUDADIS-IV. A lifetime dependence diagnosis required the participant to endorse at least three of the seven DSM-IV symptom criteria for dependence occurring in the same 12-month period. The final outcome variable was a binary indicator of lifetime diagnosis (versus no diagnosis, among individuals with a history of substance use) of alcohol dependence (with or without abuse) or any other type of illicit drug dependence (with or without abuse) or both. Illicit drug dependence was assessed with regard to symptoms related to marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, heroin, sedatives, tranquilizers, and stimulant use. In the current work, age of alcohol use initiation (M = 20.50, SD = 7.91) was conceived of as an alternative indicator of liability for problematic substance use involvement (e.g., Grant & Dawson, 1997; Hawkins et al., 1997). It was assessed with a single item asking respondents to report the age at which when they started drinking alcohol, not counting small tastes or sips.

Control variables

All analyses controlled for age at Wave 2 (M = 48.17, SD = 16.74), ethnicity [0 = non-Hispanic (n = 24,931), 1 = Hispanic (n = 5,251)], race (0 = white/European American, (n = 18,325); 1 = black/African American, American Indian/Native American, Asian/Pacific Islander, other, (n = 11,857)], religiosity (composite of service attendance and perceived importance; M = –.19, SD = 1.19). These variables have been established (e.g., Corliss et al., 2008; Fergusson, Horwood, Ridder, & Beautrais, 2005; Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008; Marshal, Friedman, Stall, & Thompson, 2009; Talley, Sher, & Littlefield, 2010) as relevant covariates for analyses related to sexual minority substance use outcomes. A subset of analyses also adjusted for physical or sexual abuse before age 17 (10%, n = 3,025).

Analytic plan

A series of regression models were used to examine relations between the three indicators of sexual orientation and reports of identity disturbance as well as between these variables and the age at which respondents’ initiated their alcohol use. Multi-nomial logistic regression models were used to examine associations between respondents’ sexual orientation indicators/identity disturbance scores and their risk for alcohol-only dependence, illicit drug-only dependence, or comorbid alcohol and illicit drug dependence diagnoses among those who indicated a lifetime history of substance use. That is, we tested the association between sexual orientation and substance dependence diagnoses in the following unordered categories: (1) those with a lifetime (LT) alcohol dependence disorder but no LT illicit drug dependence disorder (AD-only group); (2) those with a LT illicit drug dependence disorder but no LT alcohol dependence disorder (DD-only group); and (3) those with both alcohol and illicit drug use disorders in their LT (AD/DD group). Respondents who reported a history of substance use but were not diagnosed with a LT alcohol or illicit drug dependence disorder were used as the reference group. Because of the complex survey design of the NESARC data-set, all estimates and 95% confidence limits (CIs) were generated using SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, 2005) and MPLUS v.6 (Muthen & Muthen, 2005), which uses appropriate statistical techniques to adjust for sample design characteristics. Indirect effects were calculated using PRODCLIN (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). In the event that no significant direct effect between a sexual orientation indicator and an outcome was found, the corresponding indirect effect was not interpreted.

Results

Is Sexual Orientation Related to Identity Disturbance and Substance Use Diagnoses?

Table 1 shows percent distributions for endorsements of sexual orientation facets across the three substance dependence diagnostic groups described previously in Wave 2 of the NESARC. In addition, average ages of alcohol use initiation across distinct facets of sexual orientation are provided. In a subset of analyses, we examined whether levels of identity disturbance differed depending on respondents’ age. Given the recency of their experience, the expectation would be that respondents in emerging adulthood, a developmental period characterized by heightened identity explorations (typically ages 18–25, extending to late 20s at times), would report the highest levels of identity disturbance (Arnett, 2005). Among female respondents, identity disturbance was found to differ across age cohorts. Specifically, female respondents aged 21–29 (M = .28, SD = .62) and 30–39 (M = .25, SD = .61) reported high levels of identity disturbance that were not significantly different from each other, b = –.04, SE = .05, 95% CI: –.14, .07, n.s. Women aged 40–49 (M = .22, SD = .56) reported lower levels of identity disturbance than those aged 21–29, b = –.15, SE = .05, 95% CI: =.25, –.05, p < .01. Finally, female respondents aged 50 and above reported the lowest levels of identity disturbance (M = .15, SD = .46) compared with those aged 21–29, b = –.46, SE = .05, 95% CI: –.57, –.36, p < .001. Among male respondents, levels of identity disturbance were also found to differ across age cohorts. Males aged 21–29 were found to have the highest levels of identity disturbance (M = .31, SD = .66). Compared with the youngest cohort, those aged 30–39 (M = .20, SD = .52), b = –.35, SE = .06, 95% CI: –.46, –.23, p < .001, and 40–49 (M = .19, SD = .52), b = –.41, SE = .06, 95% CI: –.53, –.29, p < .001, reported lower levels of identity disturbance that did not differ significantly from each other. Similar to female respondents in the same age cohort, male respondents aged 50 and above reported the lowest levels of identity disturbance (M = .14, SD = .46) compared with their counterparts aged 21–29, b = –.66, SE = .06, 95% CI: –.77,–.54, p < .001.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Identity Disturbance Symptomology and Substance Use Outcomes Based on Sexual Orientation Facets for Lifetime Female (n = 16,629) and Male (n = 13,553) Alcohol/Drug Users in NESARC

| Sexual orientation | Women |

Men |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 1 Identity disturbance symptoms | LT AD only | LT DD only | LT AD/DD | Age of alcohol initiation | ≥ 1 Identity disturbance symptoms | LT AD only | LT DD only | LT AD/DD | Age of alcohol initiation | |

| Sexual attraction | ||||||||||

| Any same-sex attraction | 18.64 | 16.02 | 1.69 | 5.11 | 21.12 (8.80) | 18.36 | 18.18 | 2.35 | 5.72 | 19.51 (6.43) |

| Only opposite-sex attraction | 12.75 | 9.65 | 1.07 | 1.58 | 21.61 (8.65) | 12.62 | 19.25 | 1.17 | 3.37 | 19.18 (6.68) |

| Sexual behavior | ||||||||||

| Any same-sex behavior | 22.24 | 24.17 | 3.42 | 9.11 | 19.35 (6.74) | 17.27 | 22.60 | 3.07 | 6.42 | 19.40 (6.64) |

| Only opposite-sex behavior | 12.91 | 9.66 | 1.02 | 1.61 | 21.66 (8.73) | 12.67 | 19.18 | 1.11 | 3.38 | 19.18 (6.68) |

| Self-identification | ||||||||||

| Any minority identification | 21.02 | 23.70 | 3.82 | 10.38 | 19.72 (6.74) | 25.58 | 26.46 | 3.39 | 6.68 | 19.07 (4.85) |

| Heterosexual | 13.00 | 9.83 | 1.06 | 1.65 | 21.62 (8.71) | 12.62 | 19.05 | 1.18 | 3.41 | 19.20 (6.70) |

Note. Percentages are reported with the exception of age of alcohol use initiation, which is reported in years, Mean (Standard Deviation). ≥ 1 Identity disturbance symptoms = binary indicator of endorsing at least one identity disturbance item. LT AD = Binary indicator of lifetime alcohol dependence (with or without abuse); LT DD = Binary indicator of lifetime illicit drug dependence (with or without abuse); LT AD/DD = Binary indicator of lifetime alcohol and illicit drug dependence (with or without abuse).

We next examined whether identity disturbance symptoms were elevated among sexual minority individuals. Among female respondents in NESARC, there were direct associations observed between levels of identity disturbance and minority sexual attractions, b = .11, SE = .02, 95% CI: .06, .15, p < .05, minority sexual behaviors, b = .14, SE = .03, 95% CI: .08, .20, p < .05, and a minority self-identification, b = .13, SE = .04, 95% CI: .05, .22, p < .05. Among male respondents in NESARC, there were also direct associations observed between levels of identity disturbance and minority sexual attractions, b = .11, SE = .03, 95% CI: .06, .17, p < .05, minority sexual behaviors, b = .10, SE = .03, 95% CI: .04, .15, p < .05, and a minority self-identification, b = .24, SE = .05, 95% CI: .13, .34, p < .05.

Adjusted direct effects between sexual orientation indicators and substance use outcomes among male and female respondents are contained in the Model 1 results of Table 2. Results confirmed that women who reported any degree of same-sex attractions, previously engaged in sexual behaviors with any same-sex partners, or reported a bisexual or lesbian self-identification were more likely to report a greater risk for lifetime substance dependence disorders and a younger age of alcohol initiation than their sexual majority counterparts. The one exception seemed to be that women who acknowledged any same-sex attractions were not significantly younger when they first began using alcohol than those reporting only opposite-sex attractions.

Table 2.

Direct Associations Between Sexual Orientation Facets and Primary Study Variables for Lifetime Female (n = 16,629) and Male (n = 13,553) Alcohol/Drug Users in NESARC

| Sexual orientation | LT AD onlya,b O.R. (95% C.I.) | LT DD onlya,b O.R. (95% C.I.) | LT AD/DDa,b O.R. (95% C.I.) | Age of alcohol use initiation b (95% C.I.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | ||||

| Model 1: Same-sex sexual attractionc | 1.95 (1.62, 2.36) | 1.86 (1.09, 3.17) | 3.86 (2.65, 5.63) | –0.53 (–1.17, 0.12) |

| Model 2: Same-sex sexual attraction | 1.88 (1.55, 2.27) | 1.70 (0.98, 2.94) | 3.44 (2.34, 5.06) | –0.49 (–1.13, 0.16) |

| Model 2: Identity disturbance | 1.61 (1.46, 1.78) | 2.24 (1.79, 2.81) | 2.46 (2.06, 2.93) | –0.38 (–0.59, –0.16) |

| Model 1: Same-sex sexual behaviorc | 2.93 (2.27, 3.78) | 3.93 (2.21, 6.97) | 6.58 (4.29, 10.09) | –1.23 (–1.88, –0.58) |

| Model 2: Same-sex sexual behavior | 2.82 (2.18, 3.64) | 3.60 (1.98, 6.56) | 5.94 (3.77, 9.36) | –1.19 (–1.84, –0.54) |

| Model 2: Identity disturbance | 1.62 (1.46, 1.79) | 2.23 (1.78, 2.80) | 2.48 (2.07, 2.96) | –0.37 (–0.58, –0.16) |

| Model 1: Minority self-identificationc | 2.91 (2.10, 4.03) | 4.32 (2.25, 8.28) | 7.56 (4.50, 12.67) | –1.16 (–1.88, –0.43) |

| Model 2: Minority self-identification | 2.83 (2.05, 3.92) | 4.06 (2.08, 7.92) | 6.98 (4.01, 12.14) | –1.09 (–1.82, –0.37) |

| Model 2: Identity disturbance | 1.63 (1.47, 1.80) | 2.25 (1.79, 2.81) | 2.50 (2.09, 2.98) | –0.38 (–0.59, –0.16) |

|

Men | ||||

| Model 1: Same-sex sexual attractionc | 1.08 (0.86, 1.36) | 2.33 (1.24, 4.38) | 2.12 (1.37, 3.28) | 0.08 (–0.48, 0.64) |

| Model 2: Same-sex sexual attraction | 1.04 (0.82, 1.32) | 2.04 (1.07, 3.91) | 1.82 (1.14, 2.90) | 0.11 (–0.44, 0.67) |

| Model 2: Identity disturbance | 1.62 (1.48, 1.76) | 2.29 (1.79, 2.94) | 2.51 (2.14, 2.95) | –0.37 (–0.62, –0.12) |

| Model 1: Same-sex sexual behaviorc | 1.36 (1.08, 1.71) | 3.31 (1.64, 6.66) | 2.30 (1.46, 3.64) | 0.03 (–0.56, 0.61) |

| Model 2: Same-sex sexual behavior | 1.31 (1.04, 1.65) | 2.84 (1.37, 5.87) | 2.10 (1.30, 3.38) | 0.07 (–0.52, 0.66) |

| Model 2: Identity disturbance | 1.61 (1.48, 1.76) | 2.28 (1.78, 2.92) | 2.52 (2.07, 2.96) | –0.37 (–0.62, –0.12) |

| Model 1: Minority self-identificationc | 1.63 (1.21, 2.20) | 3.42 (1.48, 7.90) | 2.39 (1.26, 4.53) | –0.07 (–0.67, 0.54) |

| Model 2: Minority self-identification | 1.49 (1.09, 2.04) | 2.67 (1.11, 6.43) | 1.81 (0.91, 3.60) | 0.02 (–0.59, 0.62) |

| Model 2: Identity disturbance | 1.61 (1.47, 1.75) | 2.27 (1.77, 2.93) | 2.52 (2.15, 2.95) | –0.37 (–0.62, –0.12) |

Note. Bolded values are statistically significant (p ≤ .05). O.R. = Odds ratio; b = unstandardized regression coefficient. Covariates included age at baseline, race (0 = white/European American, 1 = black/African American; American Indian/Native American; Asian/Pacific Islander; other), ethnicity (0 = non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic), and religiosity.

Odds ratio (confidence intervals that include 1 are nonsignificant). LT AD only = Binary indicator of lifetime alcohol dependence (with or without abuse) with no lifetime illicit drug dependence diagnosis. LT DD only = Binary indicator of lifetime illicit drug dependence (with or without abuse) with no lifetime alcohol dependence diagnosis. LT AD/DD = Binary indicator of lifetime alcohol and illicit drug dependence (with or without abuse).

Reference group was individuals with no lifetime alcohol or illicit drug dependence diagnosis.

Reference group is individuals endorsing only opposite-sex/heterosexual facets of sexual orientation.

† Covariates included age at baseline, race (0 = white/European American, 1 = black/African American; American Indian/Native American; Asian/Pacific Islander; other), ethnicity (0 = non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic), and religiosity.

Results were largely similar for male respondents, with a few exceptions. First, men who acknowledged any same-sex sexual attractions were at no greater risk for AD only compared with their opposite-sex attracted counterparts. Second, male respondents who indicated any same-sex attractions, same-sex sexual behaviors, or a minority self-identification were not any younger than their sexual majority counterparts when they initiated their alcohol use.

Does Identity Disturbance Relate to Substance Dependence?

As shown in the Model 2 results of Table 2, taking into account sexual orientation facets and other covariates, women and men with higher levels of identity disturbance reported a greater prevalence of lifetime AD only, DD only, or combined AD/DD. In addition, women and men who endorsed higher levels of identity disturbance initiated their alcohol use at an earlier age than their peers who reported lower lifetime levels of identity disturbance.

Could Identity Disturbance Account for Shared Variance in the Relation Between Sexual Orientation and Substance Use Dependence?

Adjusted indirect effect estimates for female and male respondents are presented in Table 3. Among women who endorsed any degree of same-sex attraction, the heightened odds of a lifetime diagnosis of AD only or AD/DD could be partially explained by elevations in identity disturbance, whereas the heightened odds for a lifetime DD-only diagnosis could be completely accounted for by these elevations. Also, among women who engaged in sexual behaviors with both- and same-sex partners, heightened odds for AD only, DD only, or AD/DD could be partially explained by elevations in identity disturbance. Finally, these findings were also replicated for those women who endorsed a lesbian or bisexual self-identification.

Table 3.

Indirect Associations Between Sexual Orientation and Primary Study Outcomes via Identity Disturbance for Lifetime Female (n = 16,629) and Male (n = 13,553) Alcohol/Drug Users in NESARC

| Sexual orientation | LT AD onlya Est. (95% C.I.) | LT DD onlya Est. (95% C.I.) | LT AD/DDa Est. (95% C.I.) | Age of alcohol initiation Est. (95% C.I.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | ||||

| Same-sex sexual attractionb | .05 (.03, .08) | .09 (.05, .13) | .10 (.06, .14) | — |

| Same-sex sexual behaviorb | .07 (.04, .10) | .11 (.06, .17) | .13 (.07, .19) | –.05 (–.09, –.02) |

| Minority same-sex self-identificationb | .06 (.02, .11) | .11 (.04, .18) | .12 (.05, .20) | –.05 (–.10, –.01) |

| Men | ||||

| Same-sex sexual attractionb | — | .09 (.04, .15) | .10 (.05, .16) | — |

| Same-sex sexual behaviorb | .05 (.02, .08) | .08 (.03, .14) | .09 (.04, .15) | — |

| Minority same-sex self-identificationb | .11 (.06, .16) | .20 (.10, .31) | .22 (.13, .32) | — |

Note. Values are statistically-significant indirect effects (p ≤ .05) with corresponding direct effects between the respective sexual orientation facet and substance use outcome. Est = Point estimate; LT AD only = Binary indicator of lifetime alcohol dependence (with or without abuse) with no lifetime illicit drug dependence diagnosis; LT DD only = Binary indicator of lifetime illicit drug dependence (with or without abuse) with no lifetime alcohol dependence diagnosis; LT AD/DD = Binary indicator of lifetime alcohol and illicit drug dependence (with or without abuse). Covariates include age at baseline, race (0 = white/European American, 1 = black/African American; American Indian/Native American; Asian/Pacific Islander; other), ethnicity (0 = non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic), and religiosity.

Reference group was no lifetime alcohol or illicit drug dependence diagnosis.

Reference group is individuals endorsing only opposite-sex/heterosexual facets of sexual orientation.

The increased likelihood that men who endorsed any degree of same-sex attractions would diagnose with DD only or AD/DD could be partially explained by elevated levels of identity disturbance. Among men who engaged in sexual behaviors with both- or same-sex partners, a heightened risk for diagnosis of AD only, DD only, or AD/DD at some point in their lifetime could be accounted for, in part, by elevated identity disturbance symptoms. The increased likelihood for male respondents who endorsed a bisexual or gay self-identification to be diagnosed with AD only, DD only, or both in their lifetime could be either partially or fully explained by feelings of an unstable sense of self.

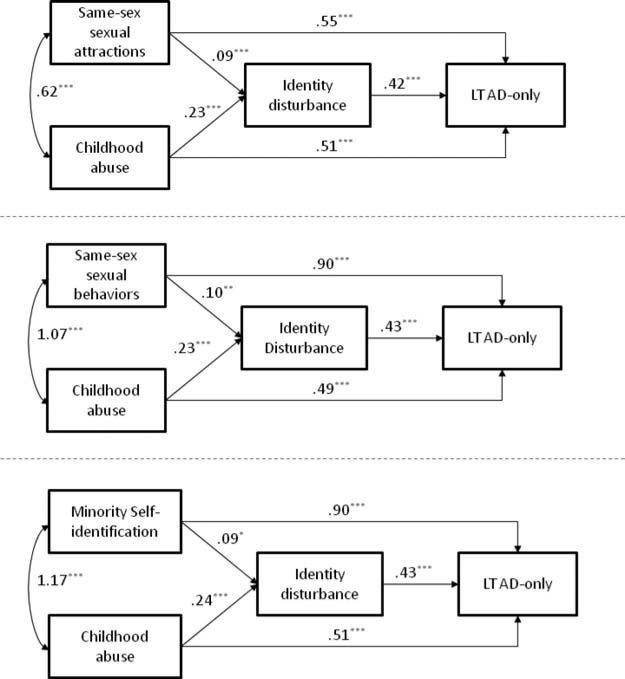

The Contribution of Childhood Abuse

Additional mediation models were constructed to examine the influence of experiences with childhood physical or sexual abuse on associations under investigation. Because of space limitations, Figures 1 and 2 present the outcomes of these models for AD-only outcomes among female and male respondents, respectively. As shown in Figure 1, female respondents who reported any degree of same-sex attractions, previously engaged in sexual behaviors with any same-sex partners, or endorsed a bisexual or lesbian self-identification also reported an increased likelihood of childhood physical or sexual abuse. These facets of sexual orientation and a history of childhood abuse were independently related to greater levels of identity disturbance among female respondents. Similar to the primary analyses, identity disturbance was predictive of an increased risk for lifetime AD. Finally, respective direct paths between facets of sexual orientation and AD only as well as between childhood abuse and AD only were positive and significant, suggesting that identity disturbance could not completely account for the associations between facets of sexual orientation and heightened risk for AD only. This pattern of findings was replicated among female respondents when examining additional outcomes, such as DD only, AD/DD, and age of alcohol use initiation (not shown). Further, in some models (two of 11), the direct path between an indicator of sexual orientation and the outcome fell to nonsignificance after taking into account reports of identity disturbance and experiences with childhood abuse.

Figure 1.

Tested path models for female respondents. Unstandardized coefficients are provided. LT AD-only = Binary indicator of lifetime alcohol dependence (with or without abuse) with no lifetime illicit drug dependence diagnosis. Covariates not shown included age at baseline, race (0 = White/European American, 1 = Black/African American; American Indian/Native American; Asian/Pacific Islander; other), ethnicity (0 = non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic), and religiosity.* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

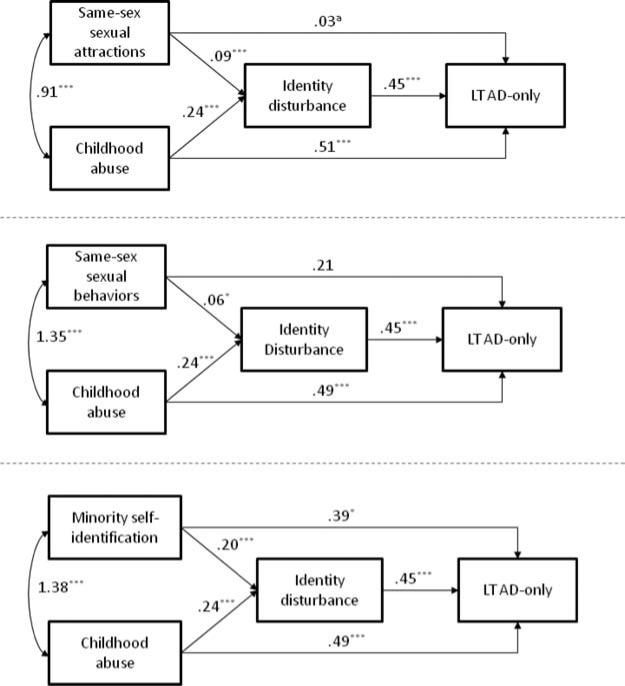

Figure 2.

Tested path models for male respondents. Unstandardized coefficients are provided. LT AD-only = Binary indicator of lifetime alcohol dependence (with or without abuse) with no lifetime illicit drug dependence diagnosis. Covariates not shown included age at baseline, race (0 = White/European American, 1 = Black/ African American; American Indian/Native American; Asian/Pacific Islander; other), ethnicity (0 = non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic), and religiosity. a Indicates bivariate; direct association is nonsignificant. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

As shown in Figure 2, male respondents who reported any degree of same-sex attractions, previously engaged in sexual behaviors with any same-sex partners, or endorsed a bisexual or gay self-identification also reported an increased likelihood of childhood physical or sexual abuse. These facets of sexual orientation and a history of childhood abuse were also associated with higher levels of identity disturbance. As expected, identity disturbance was related to heightened risk for lifetime AD. Finally, the direct path from childhood abuse to AD only was positive and significant, whereas the direct path between same-sex behaviors to AD only was positive and nonsignificant. This suggests that the shared association between same-sex sexual behaviors and AD only could be completely accounted for by variables in the model, but that the association between childhood abuse and AD only was unlikely to be fully explained by these same variables. Among male respondents, this pattern of findings was generally replicated for DD only and AD/DD outcomes. In some models (four of nine), however, the direct path between a facet of sexual orientation and the outcome would remain significant even after taking into account reports of identity disturbance and experiences with childhood abuse. Finally, based on previously reviewed findings for male respondents, it is unlikely that identity disturbance levels and experiences with abuse could account for relations between any facet of sexual orientation and younger age of alcohol use initiation, because there was no direct relation to explain (see Table 2). Consequently, no shared variance between these reports could be accounted for by explanatory variables in the model.

Discussion

These findings provide important insights into greater risk of alcohol and illicit drug dependence among individuals with a history of substance use who endorse sexual minority attractions, behaviors, or identities. Specifically, they show that the greater prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug dependence diagnoses among some subgroups of sexual minority individuals may be partially explained by elevated feelings of an unstable sense of self. These findings provide researchers with an important avenue for better understanding patterns of sexual minority substance use. Interestingly, the findings were largely similar for female and male respondents, suggesting that risk for substance use disparities may be partially explained by feelings of an unstable sense of self, regardless of respondent sex.4 Notably, effect sizes for substance use outcomes among female sexual minority respondents were somewhat larger than those evidenced by male sexual minority respon- dents. An examination of these discrepancies indicates that sexual minority women tend to report substance use and dependence at levels similar to male respondents, as opposed to their female sexual majority peers (see also Talley, Sher, & Littlefield, 2010).

The current findings also provide support that, among individuals with a history of substance use, those who report elevations in identity disturbance are also more likely to endorse problematic substance use (e.g., Rose, Rodgers, & Small, 2006; Schwartz et al., 2008; 2009). These findings are also consistent with Jorgenson’s (2006) and Cassel’s (1990) sentiments that substance use is one way that individuals with identity disturbance assuage feelings of conflict and isolation. After encounters with identity-related stressors, individuals with an unstable sense of self may use substances as a means for emotion regulation. The larger literature has revealed associations between stressors that incite negative affect and increases in alcohol-related problems (e.g., Baker et al., 2004; Dawson, Grant, & Ruan, 2005; Hasin, Keyes, Hatzenbuehler, Aharonovich, & Alderson, 2007; Sher, 1987; Sher & Grekin, 2007). These stressors may be external or arise from internal self- appraisals that increase negative affect (Baker et al., 2004). Notably, these types of stressors are believed to be relevant to individuals with concerns about sexual identity (e.g., Meyer, 2003). Baker and colleagues (2004) argue that although the relation between stress-induced negative affect and drug-seeking behaviors in the larger literature is equivocal, the strength of this association may be amplified, depending on factors such as the timing of drug use and availability, match between types of affect and drug effects, as well as the environmental and cognitive contexts of drug use.

Recent empirical evidence (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008) has provided some support for our assertions by showing that, among sexual minority individuals, positive associations between stigma-related experiences and alcohol-related problems are explained, in part, by elevated levels of coping motives. Coping motives, defined as the “strategic use of alcohol to escape, avoid, or otherwise regulate negative emotions” (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995, p. 991), have been found to be positively related with problematic alcohol use in the larger literature as well. Thus, emerging evidence is consistent with the idea that individuals at risk for heightened identity disturbance, such as sexual minority individuals, may be more likely to use substances as a means for negative emotion regulation.

Sexual minorities may report higher levels of identity disturbance for a number of reasons. As mentioned previously, based on reasoning from Erikson's work (1968), identity disturbance may develop when sexual minority individuals encounter difficulties developing and consolidating their sexual identity. Thus, it may be that the increased risk for problematic substance use by certain subgroups of sexual minorities arises as a result of identity conflict encountered as individuals attempt to reconcile and integrate aspects of their sexual identity (e.g., Cass, 1984; Rose, Rodgers, & Small, 2006; Russell, 2006). In addition, increased levels of identity disturbance may arise because of sexual minorities’ experiences with childhood victimization (e.g., Hughes et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2007), which are believed to contribute to heightened risk for experiencing identity disturbance (Peppard, 2008). Given that a subset of analyses took into account respondents’ history of childhood abuse and this did not completely attenuate the relation between sexual orientation and acknowledgement of identity disturbance, there is reason to believe that sexual minority status per se provides an inherent risk for elevations in identity disturbance, independent of those conferred by experiences with abuse.

Similarities in the rates of alcohol and illicit drug dependence and the age at which alcohol use is initiated among some subgroups of heterosexual and nonheterosexual individuals with a history of substance use preempt attempts to explain health disparities where none exist. For example, (1) the odds of being diagnosed with lifetime alcohol dependence were not greater for men who reported same-sex attractions (or age of alcohol use initiation for women with same-sex attractions), compared with their counterparts who reported only opposite-sex attractions, and (2) the age of initiating alcohol use was not different among men, regardless of sexual attractions, sexual behaviors, or sexual orientation self-identification. This latter finding suggests that although sexual minority men may initiate alcohol use at ages similar to their sexual majority peers, sexual minority men's subsequent alcohol use may ultimately reach levels that are more problematic.

Limitations

Despite these intriguing implications, our findings are limited in a number of important ways. First, subgroups of sexual minority individuals (e.g., bisexual, gay/lesbian) were combined within facets of sexual orientation (i.e., sexual behavior, sexual attraction, self-identification). Thus, the current conclusions regarding the contribution of identity disturbance to heightened risk for problematic substance use outcomes are applicable to individuals who acknowledge any degree of same-sex sexual behavior, same-sex sexual attractions, or sexual minority self-identifications. Although we recognize this may not be ideal given research (e.g., Corliss et al., 2008; Hughes, Szalacha, & McNair, in press; Marshal et al., 2008) that has shown disparities among certain subgroups of sexual minorities (e.g., self-identified bisexual versus gay/lesbian individuals) with regard to prevalence of problematic substance use outcomes, we did so to focus our analyses and to avoid issues with sparseness. Specifically, despite that a large epidemiological dataset was used to test our hypotheses, low base rates of lifetime substance use disorders were found, especially when examining their prevalence within sexual minority subgroups of male and female respondents. In addition to aforementioned statistical considerations, subgroup analyses would have added considerable length to the current paper without the benefit of additional clarity to the overall conclusions. Supplementary analyses (not shown) did suggest, however, that individuals who endorsed sexual behaviors with or attractions to both males and females or who self-identified as bisexual were generally more likely to endorse higher levels of identity disturbance, compared with other majority and minority sexual orientation subgroups. Regardless, further supplemental analyses that examined associations between identity disturbance and problematic substance use outcomes indicated these relations were largely similar across sexual minority subgroups. Future research may help clarify instances in which the current pattern of findings is not replicated.

Next, although direct and indirect effects in the current report were relatively “small” to “moderate” in magnitude [direct effect sizes (d) were attenuated by 3–24% when taking into account identity disturbance; Chinn, 2000), we would not necessarily expect to see strong associations both because only a subset of sexual minorities are expected to endorse feelings of an unstable sense of self and only three binary items were used in the calculation of identity disturbance (limiting assessment of this construct and yielding a coefficient alpha of .57).

Also, these data are cross-sectional (i.e., the predictor and outcome variables are measured at the same time), and as such we are unable to make casual statements regarding the associations between these variables. For example, despite path models that implied a causal link between identity disturbance and substance dependence diagnoses, it is reasonable to argue that substance dependence diagnoses may have just as easily led to fluctuations in identity disturbance or that unmeasured third variables representing the true causal mechanism were not considered, and thus the associations here are spurious. Importantly, a number of alternative models may have fit the data equally well (Tomarken & Waller, 2003). Future studies are needed to clarify the causal relationships that may exist between sexual orientation, identity disturbance, and problematic substance use involvement.

Additionally, age was included as a covariate in all analyses. Notably, the associations tested in the current analyses may be developmental in nature and thus be moderated by respondent age. Despite this possibility, the use of lifetime measures of sexual orientation facets, identity disturbance symptoms, and substance dependence diagnoses limited our ability to adequately address this potential age moderation. However, in supplemental analyses conducted separately by age cohort (not shown), the pattern of findings was generally replicated (i.e., 91% of associations were consistent with discussed findings). Future studies using past-year reports of these constructs may better speak to whether age is a significant moderator of these effects.

Finally, a sexual minority identity is presumed to be a stigma-tized identity (e.g., Meyer, 2003). Although additional stigmatized identities were assessed in the NESARC survey, and our hypotheses may apply to individuals who endorse these identities, an examination of whether our predictions extended to other groups was beyond the scope of the current work. Additional analyses would allow for an improved understanding of whether fluctuations in identity disturbance among individuals with other stigmatized identities would also relate to problematic substance use outcomes.

Conclusions

Although the majority of sexual minority individuals who report that they have used substances do not have an alcohol or illicit drug use disorder, they are more vulnerable to problematic substance use compared with their sexual majority peers. We examined one likely explanation: that sexual minorities are susceptible to a known predictor of substance use, namely identity disturbance (Erikson, 1968; Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Given that identity disturbance only accounted for a small-to-moderate proportion of these established disparities, other contributors are likely to be relevant. For example, heightened substance use dependence may be an artifact of gaining entrances into the sexual minority community in which bars and social clubs are the primary venues where group affiliation occurs (e.g., Drabble, Midanik, & Trocki, 2005; Orenstein, 2001).

Although the current work views alcohol and illicit drug consumption as a means to alleviate identity-related stress, the focus is on motivations to assuage negative affect that may arise, in part, because of feelings of an unstable sense of self. Based on our suppositions, one approach for lowering health disparities between sexual minority and sexual majority individuals with regard to substance use involvement is to encourage positive exploration and integration of aspects of sexual identity and sexuality (e.g., Savin-Williams, 2001b). Another approach would be to encourage sexual minority individuals to adopt alternative, healthier coping strategies to deal with negative affect that may arise in the face of identity conflicts. Practitioners may accomplish this by providing a supportive environment that facilitates a healthy, positive examination of same-sex attractions and behaviors as well as the acquisition of adaptive coping strategies to deal with the stressors associated with the integration and subsistence of a minority sexual identity.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants T32 AA13526, R01 AA016392, R37 AA07231, and KO5 AA017242 (to Kenneth J. Sher).

Footnotes

Two waves of NESARC data collection have been conducted. Although there was a Wave 1 NESARC study, this survey did not include measures of sexual orientation or identity disturbance symptoms.

Increasingly, theoretical (e.g., Sell, 1997) and empirical (Marshal et al., 2008; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007) distinctions between sexual minority sexual attractions, sexual behaviors, and self-identifications (i.e., sexual orientation indicators) are being examined within the literature to uncover whether distinct associations exist between these conceptually and empirically distinct facets of sexuality and substance use outcomes.

Though the alpha reliability for the measure of identity disturbance was not ideal, this was not surprising given that only three binary items were used in its calculation. The average inter-item correlation was approximately .30. Calculating the reliability of a new measure using the Spearman-Brown prediction formula (Allen & Yen, 1979) showed that given an identity disturbance scale with an additional three equivalent items, the alpha reliability would exceed .70. Measures of identity disturbance often include items about subjective feelings of a lack of sense of self (Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1994; Widiger, Mangine, Corbitt, Ellis, & Thomas, 1995; Morey, 1991; Loranger, Susman, Oldham, & Russakoff, 1987). Self-concept clarity (Campbell et al., 1996) was inversely correlated (r = –.50) with a measure of identity disturbance intended for clinical populations (Pollock, Broadbent, Clarke, Dorrian, & Ryle, 2001). These items currently used to assess for identity disturbance are similar to those used in the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997), the International Personality Disorder Examination (Loranger, 1999), and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (Zanarini et al., 1996). It was not required that participants report that any of these indicators of identity disturbance were related to social or occupational impairment.

A series of multi-group SEM models were conducted to examine whether the primary mediation process under investigation was similar for female and male respondents. Scaled chi-square difference tests (Muthen & Muthen, 2005) were calculated (a) for 12 models constraining the path between sexual orientation facets to identity disturbance reports as well as the path between identity disturbance reports to problematic substance use outcomes (i.e., the indirect paths) to be equivalent for female and male respondents and (b) for 12 models freeing these indirect paths. In all comparisons, constraining indirect paths to be equivalent for female and male respondents did not result in a significant decrease in fit. These findings suggest that the proposed intervening process may be similar for male and female sexual minority individuals.

References

- Allen M, Yen W. Introduction to measurement theory. Brooks/Cole; Monterey, CA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., rev. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, Molnar BE. Sexual violence victimization history and sexual risk indicators in a community-based urban cohort of “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1015–1020. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DF, McGlashan TH, Grilo CM. Exploratory factor analysis of borderline personality disorder criteria in hospitalized adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2006;47:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Trapnell PD, Heine SJ, Katz IM, Lavallee LF, Lehman DR. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(1):141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cappell H, Greeley J. Alcohol and tension reduction: An update on research and theory. In: Blane HT, Leonard KE, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcohol. Guilford Press; New York: 1987. pp. 15–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cappell H, Herman CP. Alcohol and tension reduction: A review. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1972;33(1-A):33–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC. Homosexual identity: A concept in need of definition. Journal of Homosexuality. 1984;9:105–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel RN. The quest for identity, drug abuse, and identity crises. Journal of Instructional Psychology. 1990;17:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2000;19:3127–3131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin JF, Lenzenweger MF, Yeomans F, Levy KN, Kernberg OF. An object relations model of borderline pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:474–499. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.5.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Ackerman D, Mays VM, Ross MW. Prevalence of non-medical drug use and dependence among homosexually active men and women in the US population. Addiction. 2004;99:989–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00759.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin B. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corte C, Zucker RA. Self-concept disturbances: Cognitive vulnerability for early drinking and early drunkenness in adolescents at high risk for alcohol problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(10):1282–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TN, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Sneed JR, Brook JS. The course and psychosocial correlates of personality disorders in adolescence: Erikson's developmental theory revisited. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:373–387. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Ruan WJ. The association between stress and drinking: Modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2005;40:453–460. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Midanik LT, Trocki K. Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual respondents: Results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR. Lesbian and bisexual female youths aged 14 to 21: Developmental challenges and victimization experiences. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7:9–29. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulit RA, Fyer MR, Haas GL, Sullivan T, Frances AJ. Substance use in borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:1002–1007. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.8.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg M, Wechsler H. Substance use behaviors among college students with same-sex and opposite-sex experience: Results from a national study. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:899–913. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity, youth and crisis. Norton; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Sexual orientation and mental health in birth cohort of young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:971–981. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DDM-IV Personality Disorders. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grant B, Kaplan K. Source and accuracy statement for the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Cho P, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Ruan WJ. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Introduction to the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Research & Health. 2006;29:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities interview schedule DSM-IV version. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Kaplan K, Shepard J, Moore T. Source and accuracy statement for Wave 1 of the 2001–2002 National Epidemio-logic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Aharonovich EA, Alderson D. Alcohol consumption and posttraumatic stress after exposure to terrorism: Effects of proximity, loss, and psychiatric history. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:2268–2275. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Trajectories and determinants of alcohol use among LGB young adults and their heterosexual peers: Results from a prospective study. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:81–90. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzitaskos P, Soldatos CR, Kokkevi A, Stefanis CN. Substance abuse patterns and their association with psychopathology and type of hostility in male patients with borderline and antisocial personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40:278–282. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:280–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Wilsnack SC, Szalacha LA. Childhood risk factors for alcohol abuse and psychological distress among adult lesbians. Childhood Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:769–789. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010;105:2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Szalacha LA, McNair R. Substance abuse and mental health disparities: Comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;71:824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson CR. Disturbed sense of identity in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20:618–644. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg OF. Severe personality disorders: Psychotherapeutic strategies. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW. International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE): DSM-IV and ICD-10 modules. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW, Susman VL, Oldham JM, Russakoff LM. The personality disorder examination: A preliminary report. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1987;1:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Ego identity and object relations. In: Masling JM, Bornstein RF, editors. Empirical perspectives on object relations theory. Vol. 5. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, Morse JQ. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, Thompson AL. Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction. 2009;104(6):974–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick W, Boyd CJ. Assessment of difference in dimensions of sexual orientation: Implications for substance use research in a college-aged population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:620–629. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and stubstance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Drabble L, Trocki K, Sell RL. Sexual orientation and alcohol use: Identity versus behavior measures. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2007;3:25–35. doi: 10.1300/j463v03n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Personality Assessment Inventory: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L, Muthen B. Chi-square difference testing using the S-B scaled chi-square. 2005 Note on Mplus website, www.statmodel.com.

- Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Gallaher PE, Kroll ME. Relationship of borderline symptoms to histories of abuse and neglect: A pilot study. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1996;67:287–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02326372. doi:10.1007/BF02326372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein A. Substance use among gay and lesbian adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41:1–15. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppard L. Evidence-based management of identity disturbance following childhood trauma. Clinical Scholars Review. 2008;1:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured interview for DSM-IV personality disorders. University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics; Iowa City: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock PH, Broadbent M, Clarke ES, Dorrian A, Ryle A. The Personality Structure Questionnaire (PSQ): A measure of the multiple self-states model of identity disturbance in cognitive analytic therapy. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2001;8:59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rose HA, Rodgers KB, Small SA. Sexual identity confusion and problem behaviors in adolescents: A risk and resilience approach. Marriage & Family Review. 2006;40:131–150. doi:10.1300/J002v40n02_07. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR, Ball S, Tennen H, Poling J, Tiffleman E. Personality disorders and substance abusers: Relation to substance use. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1998;186:87–95. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199802000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of New psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1–3):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Substance use and abuse and mental health among sexual-minority youths: Evidence from Add Health. In: Omoto AM, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual Orientation and Mental Health. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2006. pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc E, Skay C, Richens K, Reis E, Poon C, Murphy A. Sexual orientation, sexual abuse, and HIV-risk behaviors among adolescents in the Pacific Northwest. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. A critique of research on sexual-minority youths. Journal of Adolescence. 2001a;24(1):5–13. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. How families negotiate coming out. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2001b. Mom, dad. I'm gay. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36:385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;S14:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Mason CA, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Effects of family functioning and identity confusion on substance use and sexual behaviors in Hispanic immigrant early adolescents. Identity. 2008;8:107–124. doi: 10.1080/15283480801938440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Weisskirch RS, Rodriquez L. The relationships of personal and ethnic identity exploration to indices of adaptive and maladaptive psychosocial functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sell RL. Defining and measuring sexual orientation: A review. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1997;26:643–658. doi: 10.1023/a:1024528427013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Stress response dampening. In: Blane HT, Leonard K, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. Guilford; New York: 1987. pp. 227–271. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER. Alcohol and affect regulation. In: Gross J, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Guilford; New York: 2007. pp. 560–580. [Google Scholar]

- Skinstad AH, Swain A. Comorbidity in a clinical sample of substance abusers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:45–65. doi: 10.1081/ada-100103118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Wethington E, Zhan G. Self-concept clarity and preferred coping styles. Journal of Personality. 1996;64:407–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Trull TJ, Sher KJ. Borderline personality features predict alcohol use problems. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:711–722. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard JP, Dibble SL, Fineman N. Sexual and physical abuse: A comparison between lesbians and their heterosexual sisters. Journal of Homosexuality. 2009;56:407–420. doi: 10.1080/00918360902821395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Sher KJ, Littlefield AK. Sexual minority status and substance use outcomes in emerging adulthood. Addiction. 2010;105:1235–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG. Potential problems with “well-fitting” models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:578–598. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiden RR. The formation of homosexual identities. Journal of Homosexuality. 1989;17:43–73. doi: 10.1300/J082v17n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian LR. When the body defines the self: Self-concept clarity, internalization, and body image. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2009;28:94–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wheelin A. The Quest for Identity. W. W. Norton & Company; New York: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Mangine S, Corbitt EM, Ellis CG, Thomas GV. Personality Disorder Interview-IV. A semistructured interview for the assessment of personality disorders. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson-Ryan T, Westen D. Identity disturbance in borderline personality disorder: An empirical investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:528–541. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Bostwick WB, Szalacha LA, Benson P, Kinnison KE. Drinking and drinking-related problems among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2008;69:129–139. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. Does physical abuse, sexual abuse or neglect in childhood increase the likelihood of same-sex sexual relationships and cohabitation? A prospective 30-year follow-up. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:63–74. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarhouse MA, Tan ESN. Sexual identity synthesis: Attributions, meaning-making, and the search for congruence. University Press of America; Lanham, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, et al. The Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. McLean Hospital, Laboratory for the Study of Adult Development; Belmont, MA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ziyadeh NJ, Prokop LA, Fisher LB, Rosario M, Field AE, Camargo CA, Austin SB. Sexual orientation, gender, and alcohol use in a cohort study of U.S. adolescent girls and boys. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]