SUMMARY

T cell development requires sequential localization of thymocyte subsets to distinct thymic microenvironments. To address mechanisms governing this segregation, we used 2-photon microscopy to visualize the migration of purified thymocyte subsets in defined microenvironments within thymic slices. Double-negative (CD4−8−) and double-positive (CD4+8+; DP) thymocytes were strictly confined to cortex where they moved slowly without directional bias. DP cells accumulated and migrated more rapidly in a specialized inner-cortical microenvironment, but were excluded from the medulla by an inability to migrate on medullary substrates. In contrast, CD4 single-positive (SP) thymocytes migrated directionally towards the medulla, where they accumulated and moved very rapidly. Our results reveal a requisite two-step process governing CD4 SP medullary localization: the chemokine receptor CCR7 mediated chemotaxis of CD4 SP cells towards the medulla, whereas a distinct pertussis-toxin sensitive pathway was required for medullary entry. These findings suggest that developmentally regulated responses to both chemotactic signals and specific migratory substrates guide thymocytes to specific locations in the thymus as they mature.

INTRODUCTION

The thymus is composed of functionally interacting stromal and hematolymphoid cells. Thymocytes derive from bone marrow common lymphoid progenitors that enter the thymus from the vasculature (Karsunky et al., 2008; Kondo et al., 1997; Serwold et al., 2009). Maturing thymocytes migrate through spatially distinct microenvironments where encounters with stromal cells promote their development (Misslitz et al., 2006; Petrie and Zúñiga-Pflücker, 2007). Immunostaining of fixed tissue reveals that the most immature double-negative precursors (DN; CD4−CD8−) reside at the cortico-medullary junction (CMJ), whereas more mature DN cells are found closer to the capsule (Brahim and Osmond, 1970; Lind et al., 2001; Porritt et al., 2003). Following pre-TCR signaling, CD4 and CD8 are upregulated, yielding double-positive thymocytes (DP; CD4+CD8+; Guidos et al., 1989) localized throughout the cortex. DP cells that interact with low avidity for self peptide: MHC on cortical epithelial cells undergo positive selection to become single-positive thymocytes (SP; CD4+CD8− or CD4−CD8+). SP cells localize primarily to the medulla, where they interact with Aire+ epithelia to undergo negative selection against tissue-restricted antigens (Hogquist et al., 2005; Starr et al., 2003).

The migration of thymocytes through these distinct microenvironments is important for proper T cell development, as shown by the developmental arrest that results from preventing DN migration towards the capsule (Misslitz et al., 2004; Plotkin et al., 2003; Uehara et al., 2006), or the autoimmunity that ensues when SP cells are blocked from entering the medulla (Kurobe et al., 2006; Ueno et al., 2004). The mechanisms contributing to thymocyte localization are not well understood. Thymic microenvironments may present specific substrates that regulate adhesion or migration via interactions with developmentally regulated receptors on thymocytes. Indeed, integrin expression changes during thymocyte development (Misslitz et al., 2006), and immature thymocyte subsets bind differentially to integrin ligands (Prockop et al., 2002). If substrate restriction segregates thymocyte subsets, then sharp boundaries for migration could exist between microenvironments. Directly observing thymocyte motility at such a boundary, like the CMJ, would provide evidence to support or refute this mechanism.

Chemotaxis may also contribute to thymocyte localization. According to this model, chemotactic signals drive DN cells to migrate from the CMJ towards the capsule, DP cells to reverse direction and return towards the CMJ, and SP cells to cross into medulla (Petrie, 2003). Indeed, chemokine receptors, a subset of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), direct thymocyte chemotaxis in vitro, and their ligands are expressed in different regions of the thymus (Campbell et al., 1999; Misslitz et al., 2006). However, steady-state distributions of thymocyte subsets in fixed tissue, which help form the basis for this model, do not allow a direct test of whether thymocyte subsets migrate directionally within the thymus.

There is a general consensus that by promoting chemotaxis, the chemokine receptor CCR7 on SP cells provides the predominant signal required for them to enter and accumulate in medulla (Kwan and Killeen, 2004; Kurobe et al., 2006; Ueno et al., 2004). However, chemokine receptors may also contribute to thymocyte motility and localization through chemokinetic effects (Okada and Cyster, 2007; Witt and Robey, 2005), or by activating integrins to enable migration on particular substrates (Thelen and Stein, 2008). It is currently unclear which of these mechanisms enable CCR7 to contribute to SP medullary localization and whether additional signaling pathways are involved. Testing these mechanisms requires real-time visualization of SP migration in the cortex and medulla in the presence or absence of specific receptors such as CCR7.

Live imaging of thymic tissue using 2-photon microscopy offers a powerful approach to test mechanisms of thymocyte localization. Previous 2-photon studies have described patterns of thymocyte motility in the cortex and the role of Ca2+ signals in their regulation (Bhakta et al., 2005; Witt et al., 2005). To address mechanisms that control localization of thymocyte subsets throughout the entire thymus, we applied 2-photon microscopy to a modified thymic slice system (Bhakta et al., 2005) in which EGFP expression in the thymic stroma permitted unambiguous identification of thymic compartments. By introducing purified thymocyte subsets into slices we determined the localization and motility of each developmental subset in all regions of the thymus, and we acutely perturbed signaling pathways to assess their contributions. Thus, we uncovered several mechanisms controlling thymocyte localization during development. First, we found that immature thymocytes lacked the ability to migrate on medullary stroma, resulting in a sharp barrier that enforced strict cortical restriction. In contrast, SP cells were able to migrate on medullary substrates, and their accumulation in medulla required chemotaxis. From the effects of pertussis toxin (PTX), we found that accumulation of CD4SP cells in medulla was the result of two mechanistically distinct GPCR-mediated processes: chemotaxis towards medulla, and entry into medulla conferred by the ability to migrate on medullary substrates. Our results provide direct evidence that CCR7 underlies SP chemotaxis; surprisingly, however, CCR7 was dispensable for medullary access, implicating other GPCRs in this process.

RESULTS

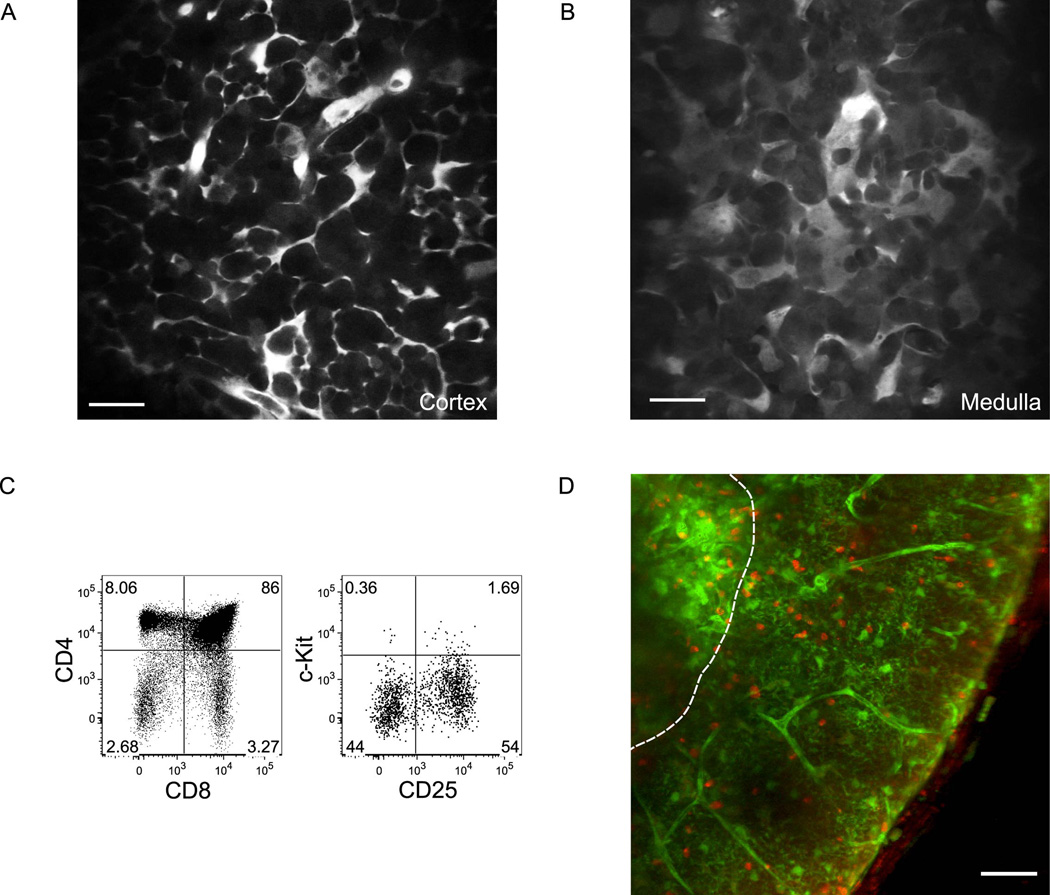

Cortex and medulla are intact and support thymocyte migration in EGFP slices

We adapted our thymic slice preparation (Bhakta et al., 2005) to enable observation of thymocyte migration within both cortex and medulla. Thymi from EGFP transgenic mice (Wright et al., 2001) were vibratome-sliced into 400-µm live tissue sections, for imaging by an upright 2-photon laser scanning microscope. While EGFP is detectable in all cells in this mouse, it is more highly expressed in the stroma, allowing us to visualize stromal structures preferentially over thymocytes. Cortical and medullary structures were clearly distinguishable by cellular morphology; the cortex contained reticular projections typical of cortical epithelial cells, while the medulla was characterized by EGFP-bright, flat sheet-like cells, characteristic of medullary epithelium (Figures 1A and 1B). The identification of thymic medulla by these morphologic criteria was confirmed by staining with the lectin UEA-1 that binds to a subset of medullary epithelial cells (Farr and Anderson, 1985; Figure S1). Unfractionated thymocytes (Figure 1C) labeled with the red dye CellTracker CMTPX were applied to the cut surface of EGFP slices. After allowing the cells to crawl into the slices over several hours, thymocytes were seen migrating in both cortex and medulla (Figure 1D and Movie S1). Thus, EGFP thymic slices provide a system for directly visualizing the migration of thymocytes in identified cortical and medullary regions.

Figure 1. EGFP slices are structurally intact and support thymocyte migration in all regions.

(A,B) Individual images from cortex (A) or medulla (B) of EGFP slices illustrate the distinct stromal morphology in each region. Medullary stroma are broader with sheet-like morphology, in contrast to the reticular projections of cortical stroma. Scale bars, 20 µm.

(C) Flow cytometric analysis of input thymocytes from B6-Ka mice. Left, CD4 versus CD8 staining gated on live events. Right, c-Kit versus CD25 staining gated on lin− CD4−CD8− cells.

(D) Thymocytes migrate into both cortex and medulla several hours after incubation atop EGFP slices. CMTPX-labeled thymocytes are shown in red, and EGFP-labeled stroma is green. Dotted line approximates the CMJ. Scale bar, 50 µm. Image is a maximum intensity projection (MIP) of individual z-sections.

Purified thymocyte subsets localize to their proper microenvironments after acute seeding of thymic slices

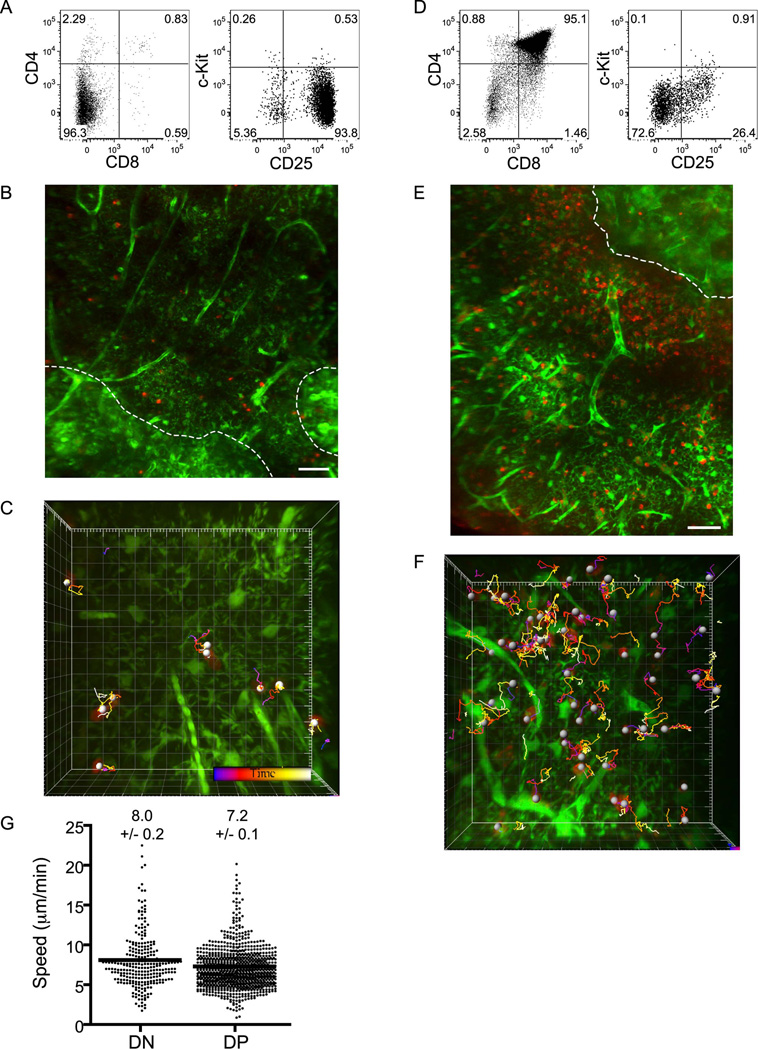

To validate the thymic slice as a model system to study thymocyte localization, we asked whether purified thymocyte subsets added acutely to thymic slices would segregate into the same microenvironments they populate in vivo. DN cells were isolated from Rag2−/− mice (blocked pre β-selection at the CD4−CD8−CD44−c-Kit−CD25+ (DN3) stage; Figure 2A), and DP cells were obtained from LN3βxRag2−/− mice (blocked pre-positive selection because TCRβ is endogenously rearranged, whereas TCRα remains in germline configuration; Serwold et al., 2007; Figure 2D). After allowing the CMTPX-labeled cells to crawl into the slices over several hours, we collected a series of 2-photon images throughout a 40-µm depth every 15 s, starting at least 20 µm below the cut surface. Strikingly, both DN and DP cells were found exclusively in cortex but not in medulla (Figures 2B and 2E), where they migrated tortuously and slowly (7–8 µm/min; Figures 2C, F, and G and S2; Movies S2 and S3). Similar results were obtained with DN cells purified from wild-type thymocytes by depletion (Figure S4). These results indicate that despite continual access to both cortex and medulla via the cut surface of the slices, immature thymocytes respond appropriately to environmental cues that confine them to cortex.

Figure 2. Double-negative (DN) and double-positive (DP) thymocytes localize exclusively to cortex and migrate slowly and tortuously.

(A,D) Flow cytometric analysis of input DN cells from Rag2−/− mice (A) or DP cells from LN3βx Rag2−/− mice (D).

(B,E) CMTPX-labeled DN (B) or DP cells (E) (red) preferentially localize to cortex in EGFP slices (green). Image properties as in Figure 1D. Scale bar, 50 µm. A duplicate image of (B) with white circles placed over DN cells to aid in visualization can be found in Figure S3. The apparent lower density of DN relative to DP cells in these fields likely reflects addition of only 1/10 the number of thymocytes to the DN versus DP slice.

(C,F) Trajectories of individual DN (C) or DP cells (F) at higher magnification in cortex throughout a ~17 min imaging session are displayed as color-coded tracks running from start (blue) to end (white) of the timecourse, as indicated by the timebar in (C). Major tics = 10 µm. (G) Cortical DN and DP speeds. Each point represents the average speed for a single tracked cell. Mean speeds ± s.e.m. for each population are given above each column and represented by a bar. n=261 for DN from 10 imaging fields in 4 slices over 3 experiments; n= 899 for DP from 10 imaging fields in 3 slices over 3 experiments.

To determine whether mature SP cells also localize properly in slices, we enriched CD4SP cells and CD8SP cells by depletion of wild-type thymocytes (Figures 3A and S5A). After seeding, labeled CD4SP cells and CD8SP cells were observed in cortex, but were greatly enriched in medulla (average density in medulla relative to cortex is 6.5 ± 0.7 for CD4SP cells and 5.2 ± 3.0 for CD8SP cells; Figures 3B, S5B and S6B). Interestingly, CD4SP cells migrated rapidly in both cortex and medulla (14.3 ± 0.3, and 16.3 ±0.3 µm/min) along relatively straight paths (Figures 3C–E, S2 and Movies S4 and S4). CD8SP cells were similarly rapid (Figure S5). Movement of both SP subsets was substantially faster and straighter than that of immature DN or DP cells, indicating that accelerated motility is acquired late in thymocyte development. Together, the segregation of immature thymocytes to cortex and mature thymocytes to medulla indicates that thymic slices provide the proper cues and microenvironments for thymocyte localization, and thus validates their use for studies of the underlying mechanisms.

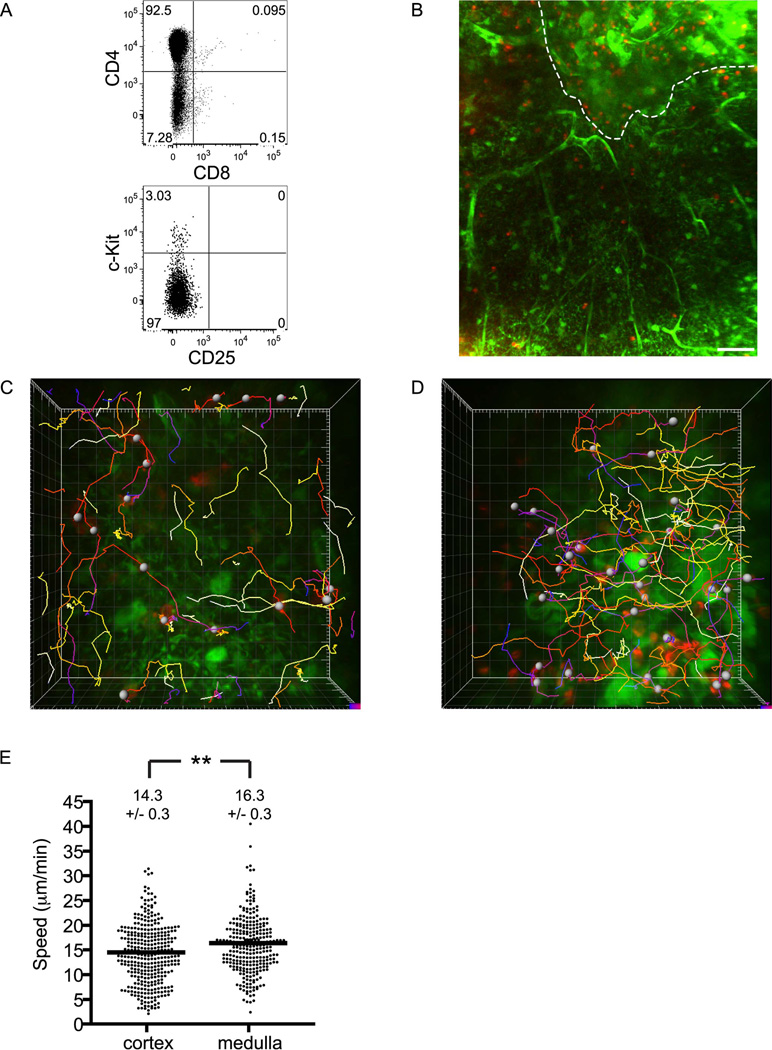

Figure 3. CD4SP cells accumulate in medulla, and migrate rapidly in all regions of thymus.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of CD4SP cells obtained by depletion.

(B) CMTPX-labeled CD4SP cells (red) are localized to both cortex and medulla in EGFP slices (green), but accumulate preferentially in medulla. A duplicate of this image with white circles placed over CD4SP cells to aid in visualization can be found in Figure S3. Image properties as in Figure 1D. Scale bar, 50 µm.

(C,D) Time-encoded tracks of CD4SP cells from high-magnification cortical (C) or medullary (D) fields imaged for ~17 min. Each major tic represents 10 µm.

(E) Average track speeds (µm/min) ± s.e.m. of cortical and medullary CD4SP cells. Medullary CD4SP cells migrate faster than cortical CD4SP cells (**, P<0.01 using the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). n=340 cells for cortex from 8 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments; n=289 for medulla from 3 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments.

DP cells accumulate near the CMJ but are confined to cortex by their inability to migrate on medullary substrates

To better understand how immature thymocytes are excluded from the medulla, we examined in detail the dynamic behavior of DP cells near the CMJ. Upon close examination, we unexpectedly found that DP cells accumulated preferentially at the cortical side of the CMJ (Figures 4A and B). Cells in this inner-cortical subregion moved significantly faster than those in mid or outer cortex (8.1 ± 0.2 versus 6.3 ± 0.1 and 6.4 ± 0.2 µm/min, respectively; P< .01 for both comparisons; Figure 4C). Cortical gradients of cell densities or velocities were not observed for any other thymocyte subset. Thus, these results suggest that the cortical region immediately adjacent to the CMJ is a distinct microenvironment affecting DP migration and localization.

Figure 4. The CMJ presents a functional barrier for pre-selection DP cells to enter medulla.

(A) Time-encoded tracks of individual DP cells from a high-magnification field at the CMJ imaged for ~17 min. Note that all DP cells are found in cortex (left side of field) and not in medulla (right side), and that tracks do not cross CMJ (representative of 3 slices containing 141 tracked DP cells). Occasional red fluorescence in medulla can be distinguished from live cells by its punctate morphology and lack of movement (Movie S6). Each major tic represents 10 µm. The area within the white box is displayed in (D) at increased magnification.

(B) DP cells accumulate near medulla. The normalized percentage ± s.e.m. of cells found within 50-µm increments from the medulla is displayed. n=876 cells analyzed from 10 series (see Methods) taken from 5 separate slices over 2 experiments.

(C) Average track speeds (µm/min) ± s.e.m. of DP cells found in cortical subregions. Velocity increases significantly from outer or mid to inner cortex (**, P<0.01). CMJ, n=141 cells from 3 imaging fields in 3 slices over 3 experiments; inner cortex, n= 244 cells from 4 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments; mid cortex, n=264 cells from 4 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments; outer cortex, n=250 cells from 4 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments; all cortex, n=899 cells from 10 imaging fields in 3 slices over 3 experiments.

(D) Example of a DP cell (►) that closely approaches but fails to cross into the medulla. Shown are individual z-planes taken at indicated times. Scale bar, 10 µm.

Despite this DP accumulation near the CMJ, we never observed a cell enter the medulla (of 141 cells tracked in close proximity to the CMJ in 4 imaging fields over 3 separate experiments; Figure 4A). Red punctate fluorescence was occasionally found in medulla but did not display the characteristic morphology or motility of intact thymocytes and was most likely cell debris (Movie S6). A typical example of DP behavior at the CMJ is shown in Figure 4D, where a cell advances twice into contact with medullary stroma (time 5:45 and 13:00) but retracts both times (Movie S7). The fact that DP cells accumulate near the CMJ along a sharp boundary argues against both a diffusible repellent from medulla, which is inconsistent with accumulation near the CMJ, and a diffusible attractant in cortex, which would not be expected to create a sharp migration barrier at the CMJ. Instead, it is likely that the DP cells are prevented from entering medulla either by encountering a surface-bound medullary repellent or a medullary substrate on which they cannot crawl, either of which would be consistent with the observed sharp boundary at the CMJ.

We considered the possibility that a specialized subset of cells at the CMJ might block DP entry into medulla. However, we failed to detect any DP cells migrating in medulla despite the fact that the cells loaded on top of the slice had direct and continual access to a complete cross-section of the medulla at the cut surface. Given that these DP cells had the opportunity to migrate on medullary stroma without going through the CMJ, the total and maintained absence of DP cells in medulla strongly implies that cortical restriction is imposed by the cells’ inability to migrate on medullary substrates rather than by a specific barrier imposed by specialized cells at the CMJ.

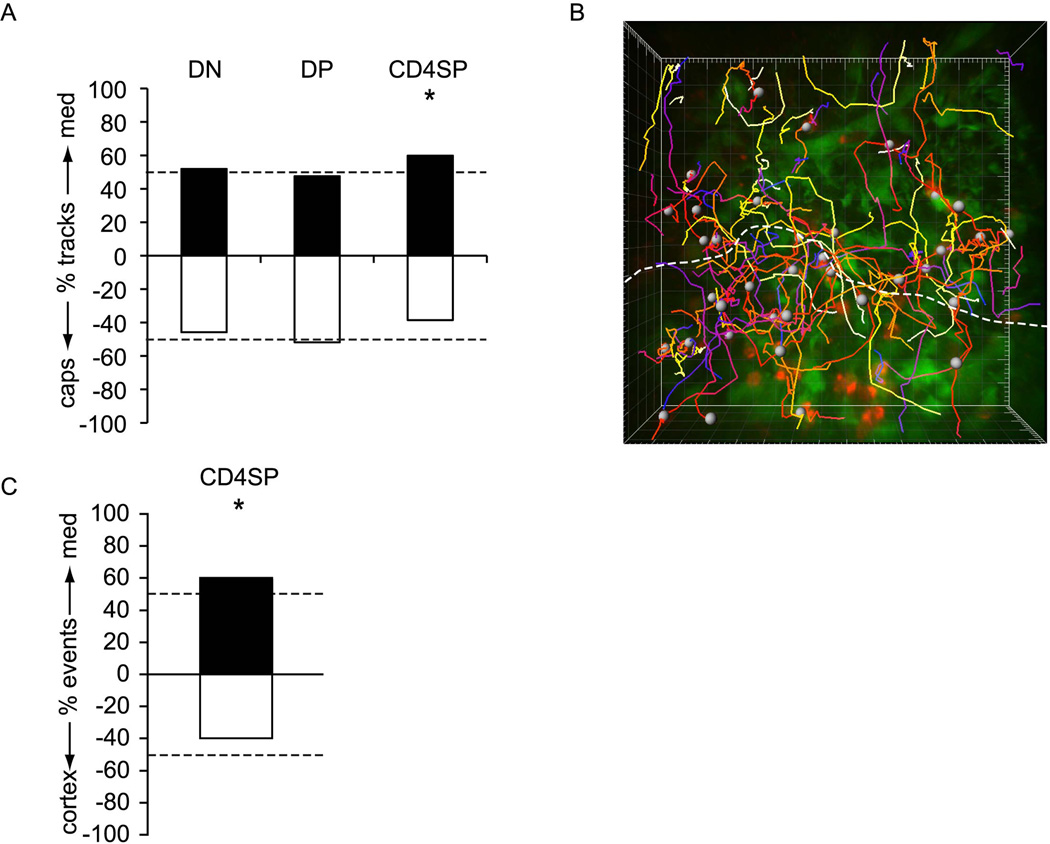

CD4SP cells migrate directionally towards medulla

In stark contrast to DP cells, SP cells were competent to migrate in both cortex and medulla, but preferentially accumulated in medulla (Figure 3). To assess the role of chemotaxis in targeting SP cells to the medulla, we first examined whether SP cells migrated directionally in cortex. Quantification of the net displacement of cortical CD4SP cells showed that that they migrated preferentially towards medulla (Figure 5A). These results are consistent with previous observations of an unidentified fast-moving population of thymocytes migrating along straight trajectories away from the capsule under positively selecting conditions (Witt et al., 2005). A close examination of the CMJ revealed that SP cells cross freely between cortex and medulla, but that the rate of medullary entry exceeds the rate of exit (Figure 5B, C and Movie S8). Given the >6-fold higher density of SP cells in medulla relative to cortex, a random walk model would predict that SP cells would leave medulla at a greater rate than they enter. Therefore, migration across the CMJ is directionally biased in a way that actively promotes the enrichment of SP cells in medulla. In addition, ~40% of all SP translocations across the CMJ were directed into the cortex (Figure 5C), demonstrating that the cells were not trapped irreversibly after entering the medulla. Overall, these data show that the directional migration of SP cells provides a mechanism of concentrating this subset in medulla, and suggests that a chemical gradient, perhaps involving chemokines, may underlie this process.

Figure 5. Cortical CD4SP cells demonstrate directional bias towards medulla and cross the CMJ preferentially from cortex into medulla.

(A) The graph represents the percentage of cortical tracks for each thymocyte subset whose net displacement after 13–17 min is towards medulla (positive values) or towards capsule (negative values). Dashed lines are at the 50%, which would be expected from a population with no directional bias. CD4SP cells display significant bias towards medulla, while DN cells (from Rag2−/−) and DP cells are not biased in either direction (*, P<0.05, chi-squared test;). n=131 Rag2/−, 465 DP, and 122 CD4SP tracks each from 2 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments.

(B) Time-encoded tracks of individual CD4SP cells from a high-magnification field clearly cross the CMJ (dashed line) in both directions over the 17 min imaging period. Major tics = 10 µm.

(C) The graph represents the percentage of CD4SP crossing events at the CMJ over ~17 min timecourses that are towards medulla (positive values) or towards cortex (negative values). Dashed lines are at 50%, which would be expected if there were no retention or preferential attraction in either region. WT CD4SP cells cross preferentially from cortex to medulla, indicating attraction towards and/or retention within the medulla (*, P<0.05, chi-squared test;). n=151 WT CD4SP crossing events from 6 imaging fields over 2 experiments.

Under similar conditions, neither DN nor DP cells displayed statistically significant bias in movement towards either medulla or capsule in any cortical region (P= 0.18 for DN cells and P= 0.35 for DP cells; Figure 5A and data not shown). This apparently random motility is not due to a general failure of the slice to support directional migration, as evidenced by SP directionality. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that directional bias occurs within a minor DN subset or on a timescale much longer than our observation window.

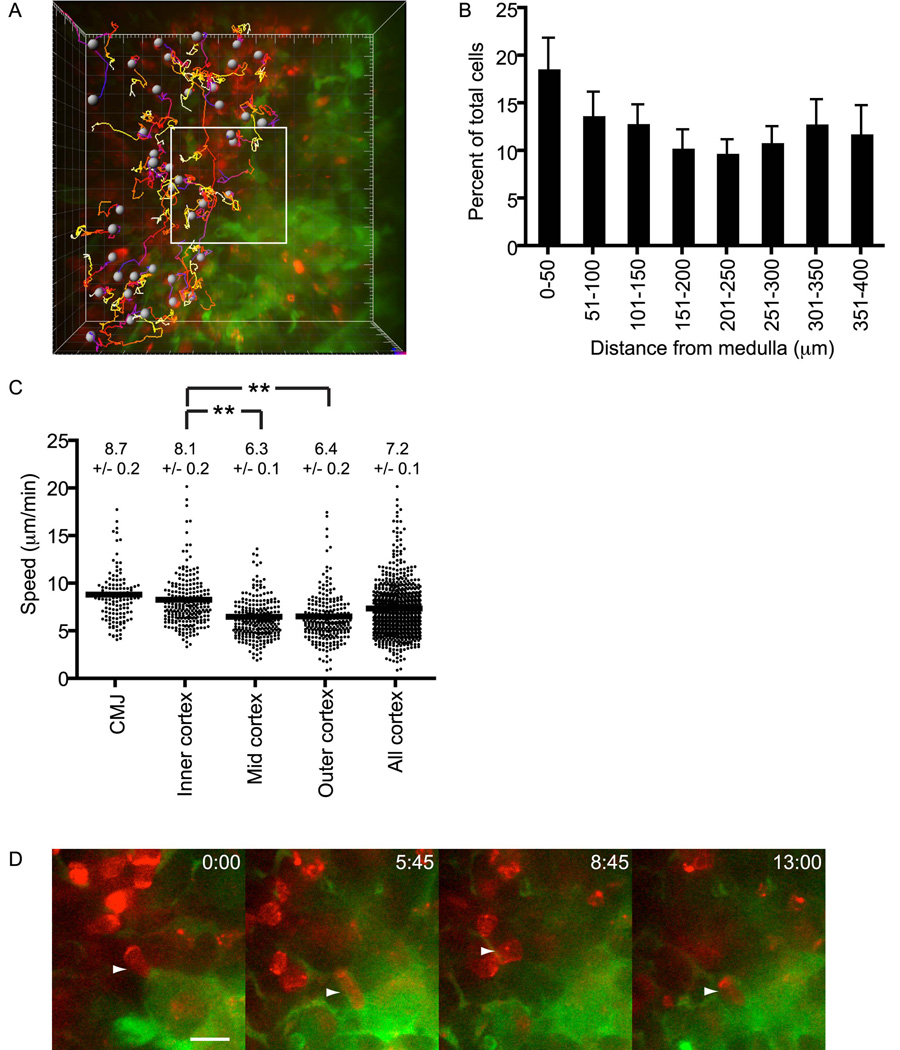

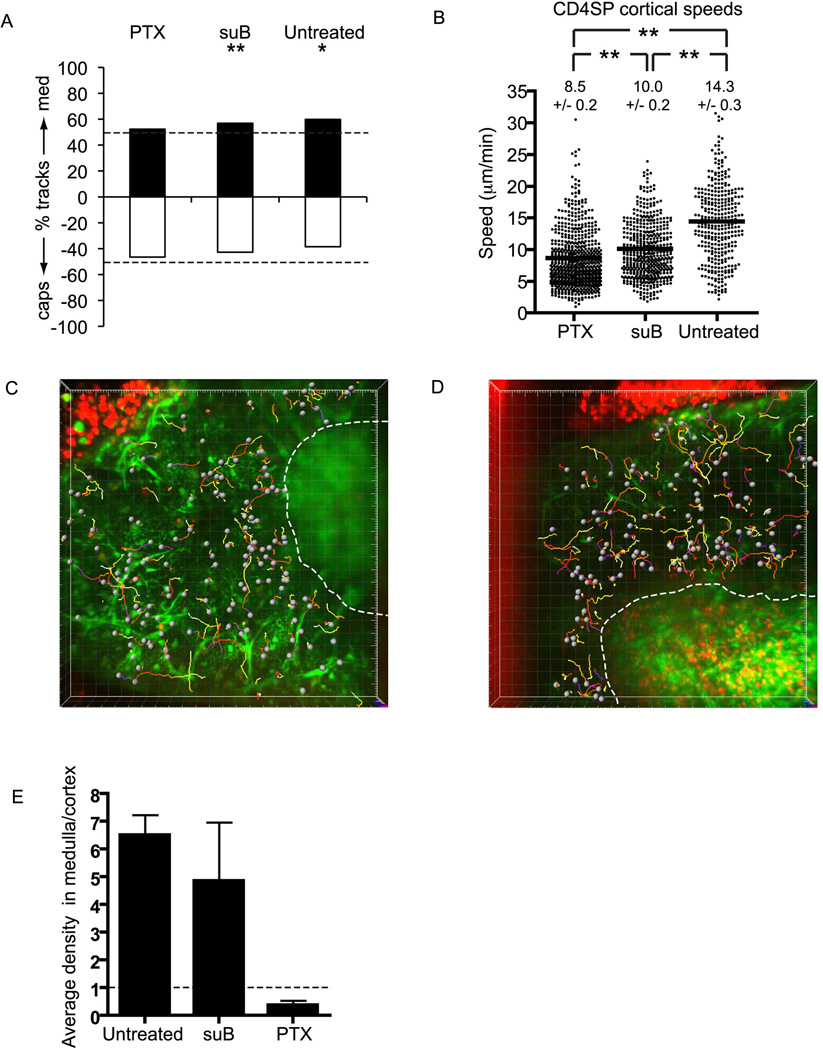

Pertussis toxin reveals two distinct GPCR-mediated processes that control the accumulation of CD4SP cells in medulla

Multiple chemokines are known to stimulate motility (chemokinesis) and directional migration (chemotaxis) of thymocytes (Campbell et al., 1999). Therefore, we initially tested whether treatment with PTX, which inhibits the GTP-binding proteins Gi and Go and thereby blocks signaling from chemokine receptors and other GPCRs, would affect the movement and localization of CD4SP cells. We treated CD4SP cells with 100 ng/ml PTX for 10 min and layered them on EGFP slices for several hours prior to imaging. This short treatment exploits a temporal window in which PTX binds but does not yet inactivate Gi or Go (Asperti-Boursin et al., 2007; Okada and Cyster, 2007), providing thymocytes an opportunity to enter EGFP slices before GPCRs are inactivated.

PTX had three distinct effects on CD4SP localization and movement. First, it eliminated directional bias of cortical CD4SP cells towards medulla. Indeed, motility of PTX-treated CD4SP cells was not biased towards either medulla or capsule, while CD4SP cells treated with the control pertussis toxin B oligomer (suB), which binds like PTX to receptors but does not inactivate Gi or Go, were still biased towards medulla (Figure 6A). These results demonstrate that GPCR signaling is necessary for directional migration of CD4SP cells towards medulla, consistent with a role for chemokines in this process.

Figure 6. PTX treatment of CD4SP cells reveals a separable GPCR-mediated medullary entry step.

(A) PTX treatment eliminates CD4SP medullary bias (**, P<0.01; *, P<0.05). Analysis as in Figure 5A. Time courses ranged from 8–17 min for PTX and 11–16 min for suB. PTX, n=572 tracks from 3 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments; suB, n= 508 tracks from 3 imaging fields in 3 slices over 2 experiments. For comparison, untreated data are duplicated from Figure 5A.

(B) PTX treatment reduces the speed (± s.e.m.) of cortical CD4SP cells relative to untreated and suB-treated CD4SP cells (**, P<0.01, non-parametric one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunn’s post test). PTX, n=691 from 5 imaging fields in 4 slices over 2 experiments; suB, n= 508 from 3 imaging fields in 3 slices over 2 experiments. For comparison, untreated data are duplicated from Figure 3.

(C,D) CMTPX-labeled CD4SP cells (red) are rarely found in medulla following PTX treatment (C) but readily enter medulla following suB control treatment (D). Time-encoded tracks of cell trajectories from a low-magnification field of slices containing CD4SP cells pre-treated with 100 ng/ml PTX (C) or suB (D) and imaged for ~8 min (C) or 11 min (D). Major tics = 20 µm.

(E) PTX treatment inhibits CD4SP cells from entering medulla. The density of CD4SP cells in medulla relative to cortex was determined in multiple low magnification fields, and then ratios were averaged for different fields, indicating the average fold enrichment of cells in medulla relative to cortex (± s.e.m.). While untreated CD4SP cells are enriched 6.5-fold in the medulla relative to the cortex, PTX treatment results in a medullary: cortical density ratio of 0.4, indicating that GPCR blockade actively prevents cells from entering medulla. Untreated, n=1593 cells from 9 imaging fields in 6 slices from 4 experiments; suB, n=821 cells from 5 imaging fields in 4 slices in 3 experiments; PTX, n = 685 cells from 10 imaging fields in 5 slices from 3 experiments.

A second effect of PTX was to reduce cortical CD4SP velocities relative to suB-treated or untreated controls (8.5 ± 0.2 versus 10.0 ± 0.2 and 14.3 ± 0.3 µm/min, respectively; Figure 6B). It should be noted that some of the slowing effect of PTX may be independent of Gi or Go inhibition because suB partially slowed migration. Interestingly, suB is known to block chemokine receptors and induce [Ca2+]i elevation in lymphocytes, both of which are possible mechanisms for the slowing of cells by suB (Alfano et al., 1999; Bhakta et al., 2005; Strnad and Carchman, 1987; Wong and Rosoff, 1996). Nevertheless, the significant difference (P< 0.01) in velocities between suB and PTX treatments indicates a role for GPCRs in CD4SP chemokinesis.

Importantly, the third effect of PTX was a pronounced exclusion of CD4SP cells from medulla. Whereas untreated and suB–treated CD4SP cells accumulated in medulla (reaching medullary:cortical density ratios of 6.5 ± 0.7 and 4.9 ± 2.1, respectively), PTX-treated CD4SP cells did not (medullary:cortical density ratio of 0.4 ± 0.2; Figure 6C–E and movies S9 and S10). Indeed, many medullary fields contained no detectable PTX-treated CD4SP cells. If chemotaxis were the sole mechanism driving the accumulation of CD4SP cells in medulla, blocking chemotaxis with PTX would be expected to produce an equal distribution of cells between cortex and medulla. However, we did not observe this result. The extreme paucity of CD4SP cells in the medulla after PTX treatment therefore suggests that a GPCR-mediated mechanism distinct from chemotaxis contributes to the preferential accumulation of untreated CD4SP cells in medulla. The most likely explanation of these results is that in addition to driving chemotaxis, GPCR activity is also required for entry into medulla by enabling SP cells to migrate on medullary substrates.

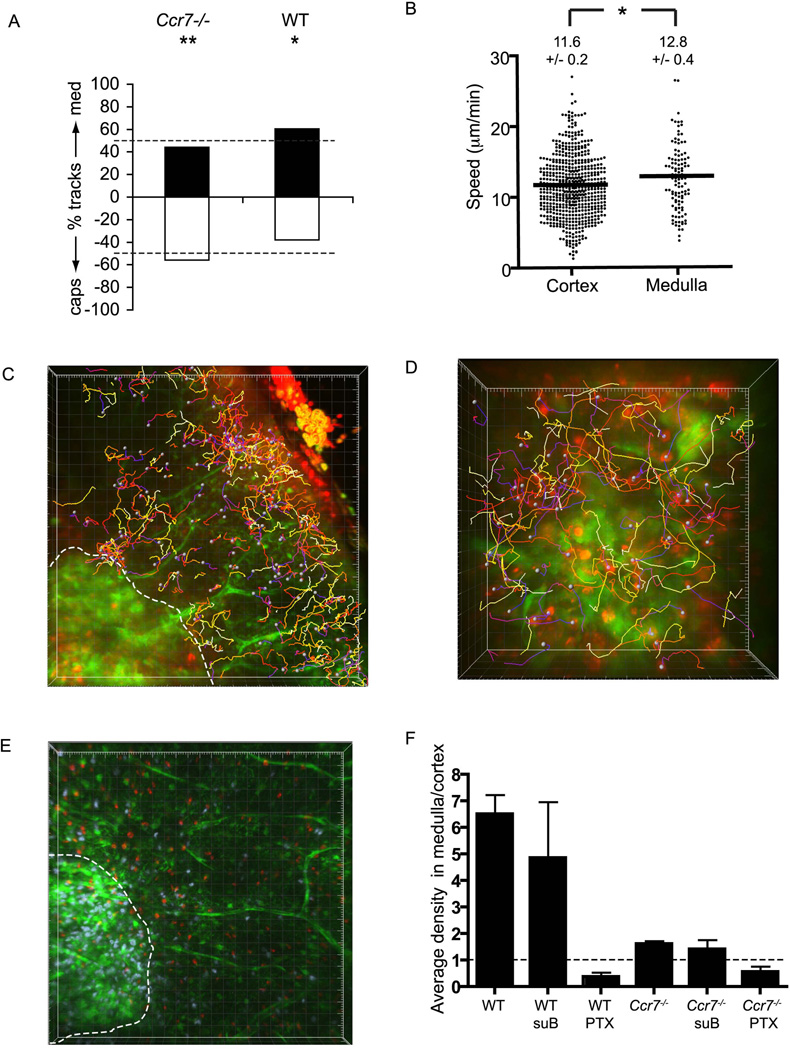

CCR7 is required for CD4SP chemotaxis but not for migration in medulla

Upregulation of CCR7 following positive selection, as well as the effects of CCR7 ectopic expression or deficiency on thymocyte localization have prompted the widely held view that CCR7 is necessary and sufficient to drive SP chemotaxis, entry and accumulation in medulla (Kurobe et al., 2006; Kwan and Killeen, 2004; Ueno et al., 2004). Therefore, we asked whether loss of CCR7 function could explain all three effects of PTX. Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells introduced into wild-type (WT) EGFP slices no longer displayed directional bias towards medulla, but instead were slightly oriented towards the capsule (Figure 7A). This result is a direct demonstration that CCR7 is necessary for chemotaxis towards medulla, and implies that CCR7 inhibition is the mechanism by which PTX blocks SP migration towards medulla.

Figure 7. CCR7 is responsible for CD4SP chemotaxis towards medulla, but is not necessary for medullary entry.

(A) Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells no longer display directional bias towards medulla, but instead migrate towards capsule. Data were analyzed over ~17 min period. Analysis as in Figure 5A (**, P<0.01; *, P<0.05). Ccr7−/−, n=602 cells from 2 fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments. For comparison, WT CD4SP data is duplicated from Figure 5A.

(B) Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells migrate rapidly (± s.e.m.) in both cortex and medulla, though medullary migration is faster (*, P<0.05). Cortex, n=602 cells from 2 imaging fields over 2 experiments; medulla, n=110 cells from 2 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments.

(C) CMTPX-labeled Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells (red) are found in cortex, but are also present in medulla in EGFP slices (green). Data collected over ~17 min. Major tics = 20 µm.

(D) Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells migrate productively in medulla, as shown by time-encoded tracks from high-magnification medullary fields imaged for ~15 min. Major tics = 10 µm.

(E) Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells do not accumulate in medulla to the same extent as WT CD4SP cells. CMTPX-labeled Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells (red) and indo-PE3-labeled WT CD4SP cells (blue) were added to the same EGFP thymic slice. Whereas WT cells clearly accumulate in medulla, Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells are more evenly distributed across the cortex and medulla. Major tics = 20 µm.

(F) Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells fail to accumulate in medulla, but are not blocked from medullary entry. Analysis as in Figure 6E; for comparison, all WT data are duplicated from Figure 6E. In contrast to the 6.5-fold accumulation of WT CD4SP cells in medulla, Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells accumulate only 1.6-fold in medulla relative to cortex. Furthermore, Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells are sensitive to PTX, which reduces the medullary: cortical density ratio to 0.6. For Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells: untreated, n=1361 from 11 imaging fields in 8 slices over 4 experiments; suB, n=476 from 4 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments; PTX, n=185 from 4 imaging fields in 2 slices over 2 experiments. These analyses include data from slices in which two populations were differentially labeled (CMTPX versus Indo-PE3) and added simultaneously to the slice as follows: 3 imaging fields with PTX-treated and suB-treated Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells; 2 imaging fields with PTX-treated and suB-treated WT CD4SP cells; and 6 imaging fields with untreated WT and untreated Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells, as in (D). The relative medullary: cortical enrichments we observed were not significantly different between the slices containing one of the above populations or two differentially labeled populations, so the two data sets were combined.

Though migration of Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells in the cortex was relatively rapid (11.6 ± 0.2 µm/min; Figure 7B and Movie S11), it was significantly slowed relative to wild-type CD4SP cells (compare Figure 7B with Figure 6B, P<0.01). Thus, CCR7 also contributes to SP chemokinesis (Figure 6B), similar to its chemokinetic effect on mature lymphocytes in lymph nodes (Asperti-Boursin et al., 2007; Okada and Cyster, 2007; Worbs et al., 2007).

Given the currently held view that CCR7 is required for medullary entry, we were particularly surprised to find abundant Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells in medulla. These cells were migrating vigorously (12.8 ± 0.4 µm/min; Figures 7B–D and Movie S12), indicating that CCR7 is dispensable for allowing productive movement on medullary substrates. Because medullary entry of Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells was unexpected, we questioned whether they were capable of crossing the CMJ into medulla or whether they only entered this region via the cut surface of the slice. In multiple high magnification CMJ fields, we directly observed Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells crossing from cortex into medulla (Figure S6A). However, in contrast to WT CD4SP cells, which preferentially cross the CMJ from cortex to medulla, Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells cross the CMJ bidirectionally at equal frequencies, consistent with the lack of chemoattraction in the absence of CCR7 (Figure S6B). Evidently, SP cells do not require CCR7 to enter the medulla or to migrate freely on medullary substrates.

When labeled with different dyes and added simultaneously to the same slice, it was clear that Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells accumulated to a much lesser extent than WT CD4SP cells in medulla (Figure 7E). The medullary: cortical density ratio for Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells was 1.6 ± 0.1 compared to 6.5 ± 0.7 for WT CD4SP cells (Figure 7F). Thus, CCR7 is required for CD4SP cells to accumulate in the medulla, consistent with its chemotactic effect, but it is not required for the cells to enter the medulla and migrate on medullary substrates. Importantly, the nearly even distribution of Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells between the medulla and cortex would be expected if CCR7 deficiency simply prevents CD4SP chemotaxis. The much lower accumulation of medullary cells after PTX treatment (medullary:cortical ratio of 0.4 ±0.2) therefore implies that a GPCR other than CCR7 plays the critical role in enabling medullary entry. PTX treated Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells were inhibited from entering medulla to a similar extent as PTX-treated WT cells (medullary: cortical density ratio 0.6 ± 0.2 for Ccr7−/− after PTX; Figure 7F), demonstrating that the Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells had not undergone compensatory upregulation of some other PTX-sensitive protein to gain access to medulla.

In sum, CCR7 deficiency prevents CD4SP chemotaxis and chemokinesis, replicating two effects of PTX, but surprisingly and unlike PTX, does not block the ability of CD4SP cells to migrate on medullary substrates. These results further reinforce our conclusion that two mechanisms, CCR7-mediated chemotaxis and medullary migration under the control of a distinct GPCR, are required to act in concert to properly target CD4SP cells to medulla.

DISCUSSION

In this study we introduce the thymic slice as a system for examining mechanisms of thymocyte migration and localization during development. The slice offers a number of advantages for these studies: the slice presents the mature three-dimensional structure of cortical and medullary compartments and provides the appropriate cues to restrict DN, DP, and SP subsets to their proper microenvironments. The motility and directionality of DP and SP cells in slices (Bhakta et al., 2005; this study) are similar to those observed in intact thymic lobes (Borgne et al., 2009; Ladi et al., 2008; Witt et al., 2005), and the slice can deliver endogenous chemotactic signals, as demonstrated by CCR7-dependent CD4SP chemotaxis towards medulla. While the preservation of endogenous chemotactic signals supported the directional migration of SP cells in this study, we cannot rule out chemotactic mechanisms influencing the localization of DN and DP cells based solely on their apparent absence of directional bias in the slice. It is possible that weak chemokine gradients may be perturbed when the thymus is sliced, or that directional bias for DN cells (or a minor DN subset) and DP cells that redistribute slowly over days may simply be undetectable during the relatively brief observation windows possible with the slice (< several hours). Despite these potential limitations, the ability to seed slices with purified populations of labeled thymocyte subsets, to delineate stromal compartments with EGFP, and to acutely perturb thymocyte signaling pathways offers a powerful new approach to directly query the mechanisms that localize thymocytes at known developmental stages to distinct microenvironments.

We used the thymic slice to investigate mechanisms that determine the cortical localization of DN and DP cells. By closely observing DP motility near the CMJ, we showed that the boundary blocking DP medullary entry is abrupt but does not appear to arise from a specialized subset of cells preventing access at the CMJ, because DN and DP cells applied directly to medullary stromal cells at the slice surface also failed to enter the medulla. Instead, immature thymocytes appear unable to migrate on medullary stroma, suggesting that substrate restriction is the basis for their confinement to the cortex. Substrate restriction has been well documented in peripheral lymphoid organs, where it is thought to restrict T and B cells to their respective zones in lymph nodes and spleen (Bajenoff et al., 2006; Bajenoff et al., 2008). How substrate restriction is achieved in the thymus is unknown but it could result from either active repulsion from the medulla or a lack of thymocyte receptors for medullary substrates. Because DP cells accumulate directly adjacent to the CMJ, if a repulsive cue exists it must be highly localized, perhaps bound to the surface of medullary stromal cells or ECM. Interestingly, semaphorins, which generate repulsive signals to control boundary formation in the nervous system, are also expressed in thymic medulla, raising the possibility of an analogous role in thymocyte segregation (Choi et al., 2008; Mendes-da-Cruz et al., 2009). In addition, because cortical and medullary epithelial cells are distinct (Derbinski et al., 2005), they may express different adhesion molecules, such as integrin ligands (Misslitz et al., 2006), which could restrict thymocyte subsets to these different regions.

Unexpectedly, a close examination of DP behavior in different cortical regions revealed a unique functional microenvironment in the thymic cortex adjacent to the CMJ. DP cells accumulate in this area and migrate more rapidly than elsewhere in cortex. The existence of a specialized compartment near the CMJ is consistent with a recent study in which pre- and post-positive selection DP cells were reported to accumulate in the inner cortex of a positively selecting thymus. In a negatively selecting background, dying caspase 3+ DP cells were also enriched in this region (McCaughtry et al., 2008). These findings suggest that delivery of positive and negative selection signals may be enhanced in inner cortex, and that the accumulation of DP cells in this region may poise them to be selected near the medulla, where they will subsequently undergo the final stages of development. It is tempting to think that their accumulation and higher speeds are a response to a weak chemoattractant released from the medulla, which they cannot enter. Further work will be needed to test this and other possible models.

In contrast to the slow tortuous migration of DN and DP cells, SP cells moved much more rapidly and followed straighter trajectories. SP cells migrate at the highest known speeds of any lymphoid cell, exceeding even those of mature T cells (16 versus 8–12 µm/min, respectively; Bousso and Robey, 2003; Mempel et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2006); similar speeds were reported in a study of medullary thymocytes in thymic lobes while this paper was under review (Borgne et al., 2009). The high speed of mature T cells is thought to enable efficient scanning of antigen-presenting dendritic cells in lymph nodes (Bousso and Robey, 2003; Miller et al., 2004). In the thymic medulla, deletion of autoreactive SP cells depends on the effective detection of rare tissue-restricted self-antigens (Anderson et al., 2002; Derbinski et al., 2008; Derbinski et al., 2001; Gallegos and Bevan, 2004; Tykocinski et al., 2008). The short residence time of SP cells in medulla (~4 days; McCaughtry et al., 2007) coupled with the small number of thymic epithelial cells that display any given tissue-restricted antigen (~1000) creates a challenge for inducing complete central tolerance (Kyewski and Klein, 2006). Thus, the rapid motility of SP cells may provide a means to optimize scanning of the full repertoire of sparsely displayed tissue-restricted antigens within medulla.

In this study, we primarily focused on the central question of how the characteristic localizations of DN, DP, and SP thymocytes are established; in particular, what restricts DN and DP cells to cortex, and what promotes the accumulation of SP cells in medulla? Previous work suggested a prominent role for CCR7 in these processes. The absence of CCR7 on immature thymocytes was thought to be central to exclusion of these cells from medulla, whereas acquisition of CCR7 following positive selection was believed to drive a chemotactic response that attracts SP cells towards the medulla and allows them to enter and accumulate in this region (Kurobe et al., 2006; Kwan and Killeen, 2004; Ueno et al., 2004). Given that we could acutely disrupt signaling pathways on the introduced thymocytes and subsequently observe their localization and motility, we were able to directly assess the roles of chemokine receptors in general and CCR7 specifically in controlling medullary localization.

A general blockade of signaling through all chemokine receptors and other GPCRs by PTX had three effects on CD4SP localization and migration: it abrogated directional migration towards medulla, it slowed cortical motility, and it largely prevented medullary access. Given the expected contribution of CCR7 to all of these processes, we directly examined whether CCR7 deficiency would recapitulate all three PTX effects. Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells move more slowly than WT CD4SP cells and fail to chemotax towards medulla, providing the first direct confirmation that CCR7 contributes to chemokinesis of SP cells and is necessary for attracting them towards the medulla. If other chemokine receptors also contribute to CD4SP chemotaxis towards medulla, then they are apparently insufficient to support chemotaxis in the absence of CCR7. Importantly, however, careful examination of the behavior of Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells showed that CCR7 was not required for medullary entry. Ccr7−/− cells localize roughly evenly between cortex and medulla, and cross the CMJ bidirectionally at an equal frequency, indicating that they can enter and crawl in medulla but that their inability to chemotax prevents their medullary accumulation. The much reduced density of PTX-treated WT SP cells in medulla relative to Ccr7−/− cells indicates that a GPCR distinct from CCR7 controls access to the medulla. This conclusion is at odds with previous work suggesting that CCR7 is necessary and sufficient for medullary localization. However, in one set of studies (Kurobe et al., 2006; Ueno et al., 2004), Ccr7−/− cells were actually present at a low frequency in medulla, indicating that entry was not inhibited; rather, the cells merely showed a defect in accumulation, consistent with our results with Ccr7−/− cells and attributable to the lack of chemotaxis. Similarly, in the study claiming that ectopic expression caused immature thymocytes to home to the medulla, DP cells expressing CCR7 primarily accumulated at the perimeter of the medulla, as expected from enhanced chemotaxis, but on close examination did not efficiently enter medulla (Kwan and Killeen, 2004).

In sum, our data suggest that during development, two key events lead from the cortical localization of DP cells to the medullary accumulation of SP cells. Following positive selection, chemotaxis towards medulla is enabled through the acquisition of CCR7, and medullary entry and migration is enabled by acquiring the ability to migrate on medullary substrates. This may come about as a result of acquiring a GPCR signaling system that is required for medullary migration, or from the loss of sensitivity to a repulsive medullary signal. Regarding the former possibility, it is interesting that chemokine receptors are known to activate integrins that regulate substrate adhesion during the extravasation of mature T cells from the circulation into inflamed tissue (Campbell et al., 2003; Thelen and Stein, 2008). An analogous mechanism may control the ability to migrate on medullary substrates efficiently in a PTX-sensitive manner. By exposing the multiple steps in medullary accumulation, these results point the way towards a molecular description of this essential event in T cell development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

C57BL/Ka, Rag2−/− Ly5.2, LN3βxRag2/− (Serwold et al., 2007), and mice transgenic for EGFP under control of the β-actin promoter (Wright et al., 2001) were maintained in our laboratory. CCR7-deficient mice on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory or from Jason Cyster (University of California San Francisco). All mice used were MHC matched. Mice were used between 3 and 8 weeks of age. All mice were maintained in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Antibodies

Protein-G purified antibodies against CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53–6.7), CD25 (PC.61), Mac-1 (M1/70), Gr-1 (8C5), B220 (6b2), Ter119 (ter119), and CD11c were purified from hybridomas and used for cell depletions. For flow cytometry, the following directly fluorophore conjugated antibodies were used and were conjugated in-house unless otherwise indicated: goat anti-rat tricolor (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), CD4-Alexa Fluor647, CD8-Alexa Fluor 488, CD3-biotin (KT31.1), gamma-delta-PE (GL3, BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), CD11c-Cy5.5PE (N418, eBioscience, San Diego, CA), NK1.1-Cy7PE (PK136, eBioscience), CD19-Alexa Fluor700 (eBio1D3, eBioscience), c-Kit-Alexa Fluor750 (2B8,eBioscience), Mac-1-Pacific Blue, CD25-Pacific Orange. Streptavidin conjugated to Q605 or Q655 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for biotin detection. For conjugations, the following were used: biotin (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL), Pacific Blue, Pacific Orange, Alexa Fluor488 or 647 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For slice staining, biotin-conjugated UEA-1 (Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with the slice, followed by detection with Texas Red-conjugated streptavidin (BD Pharmingen). Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and analysis was carried out using FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Media

Full RPMI media: RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/ml of penicillin, 50 µg/ml of streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). DRPMI media: powdered RPMI 1640 medium deficient in phenol red (Cellgro) plus 0.2 g/L of NaHCO3 and 20 mM HEPES. Slice perfusion media: powdered RPMI 1640 medium deficient in phenol red supplemented with 2 g/L of NaHCO3, 5 mM HEPES, and 0.85 mM CaCl2 (total [Ca2+] = 1.25 mM).

Slice preparation and imaging

Vibratome-cut thymic slices were prepared as described (Bhakta et al., 2005), with some modifications. Slices were cut from EGFP thymi. For labeling, thymocytes were isolated in DRPMI medium + 10% FBS; 1–10 × 106 thymocytes were labeled with 5 µM CellTracker CMTPX (Invitrogen) in 1.5 ml DRPMI medium without serum for 30 min at 37°C/6% CO2, followed by destaining in 1.5 ml full RPMI for 30 min at 37°C/6% CO2. Labeled thymocytes were washed twice with full RPMI and layered on slices inside a ring of silicone grease; cells migrated into slices for at least 3 hrs at 37°C/6% CO2 before imaging. In indicated experiments, thymocytes were labeled with Indo-PE3 (Teflabs) for 1.5 hours in full RPMI, washed once and added to EGFP slices along with CMTPX-labeled cells. In some experiments, CMTPX-labeled or Indo-PE3-labeled thymocytes were treated with 100 ng/ml pertussis toxin (PTX) or its B oligomer (suB) for 10 min at 37°C/6% CO2 in 1 ml full RPMI, washed twice with full RPMI and then layered on slices

2-photon imaging was conducted on a custom-built upright microscope (Sutter Instruments), using a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser tuned to 850 nm (Mira 900, Coherent) and either a 20x/0.95NA (XLUMPlanFl, Olympus) or a 63x/0.9NA (Achroplan, Zeiss) objective. Emitted light was passed through 535/50 and 610/50 bandpass filters (Chroma) to separate photomultipliers for detection of EGFP and CMTPX fluorescence, respectively. Acquisition was controlled using MPScope software (Nguyen et al., 2006); typically, z-stacks of 483 x 483 x 40 µm (20x objective) or 152 × 152 x 40 µm (63x objective) were acquired every 15 seconds, with z-steps spaced 5 µm apart. Imaging was done roughly 20 µm beneath the cut surface of the slice to ensure intact tissue structure. A Pockels cell (Conoptics) was used to step laser power while moving deeper into tissue during acquisition. In cases where both CMTPX and Indo-PE3 labeled cells were imaged in the same slice, images were first acquired simultaneously for the CMTPX-labeled cells and EGFP fluorescence as described above The laser was then retuned to 710 nm and additional z-stacks through 40 µm of the same region were acquired at 15 second intervals using a 480/120m-2p filter to collect emitted Indo-PE3 fluorescence.

During imaging, slices were immobilized with a slice anchor within a chamber (RC-26GLP, Warner Instruments). Slices were continuously perfused with oxygenated slice buffer (95% O2/5% CO2) at a rate of ~1 ml/min; a heated chamber platform (Warner) and inline perfusion heater maintained the chamber temperature at 36°C. Slices were imaged from 3 to 9 hours post thymocyte seeding with no appreciable change in results.

Purification of thymocyte subsets

When indicated, prior to CMTPX labeling, C57BL/Ka thymocytes were depleted by immunomagnetic separation using mAbs against non-T lineages: B220, Mac-1, Gr-1, Ter119, and CD11c. mAbs against CD4 and CD8 were used for DN enrichments; CD8 + CD25, or CD4 + CD25 were used to obtain CD4SP cells, or CD8SP cells, respectively. Thymocytes were incubated with the depleting antibodies for 30 min on ice in PBS+10% FBS, and were then incubated with anti-rat magnetic beads (Dynal) at a ratio of 2 cells: 1 bead, followed by magnetic depletion of bound cells. A second round of depletion was carried out with half the number of beads to improve enrichments. Flow cytometry was conducted post-purification, and typical purities were >95% (DN), >90% (CD4SP), and ~78% (CD8SP), with <1% of cells which had escaped depletion.

Image analysis

Imaris 6.0 (Bitplane AG) was used to track cell positions over time. Track speeds = path length divided by time observed. In some analyses of low-magnification fields, cortex was divided into equal thirds, and speeds were determined within these subregions. Track straightness = displacement (end minus start position) divided by path length, with a value of 1.0 representing a perfectly straight trajectory. Red fluorescence outside of thymic capsule represents cells not in tissue and was ignored (Figures 6 and 7).

To quantify directional bias, tracks from low-magnification fields were analyzed for their net displacement in the axis orthogonal to the CMJ and the capsule. Fields used for this analysis exhibited optimal slice orientation where the CMJ and capsule were both visible and roughly parallel to each other. For some fields, the coordinates were rotated using trigonometric functions to facilitate analysis. The percentages of tracks whose net displacement was towards or away from medulla were quantified. By convention, positive values indicate net movement towards medulla.

Relative enrichment of cells in medulla versus cortex was determined from low-magnification fields: the number of cells in medulla or cortex at a single timepoint was normalized to the total volume of those regions to obtain cortical or medullary cellular densities. The ratio of medullary density to cortical density was determined for each imaging field, and these ratios were averaged to yield the average fold enrichment in medulla relative to cortex.

To quantify DP density as a function of distance from medulla, a series of adjacent z-stacks (either 21 × 2 µm or 15 × 5 µm) was collected at high magnification (63x), starting in medulla and moving laterally towards capsule along either the x or y axis with each successive z-stack. The lateral distance of each cell from the start of medulla was binned in 50 µm increments, for 10 series. Distance varied from medulla to capsule in each series, so only the first 400 µm of cortex away from medulla, where the majority of series contributed to the analysis, were considered. The percentage of cells within each bin was calculated for each series individually to normalize for the total number of cells within that series. The percentage of cells in each bin were then averaged across the 10 series, and plotted.

To calculate the number of events that crossed the CMJ in either direction, multiple high magnification CMJ imaging fields containing either WT or Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells were analyzed. Each time a cell crossed the CMJ, one crossing event was counted either in the direction of the cortex or medulla. The percentage of events crossing in either direction was then determined and graphed for both populations.

For all analyses, we report in the figure legends the number of cells analyzed in a given number of imaging fields, recorded in a given number of slices over a number of separate experiments, which were performed on different days. The slices imaged on a given day were sometimes mixed from two mice, so the number of experiments provides a minimum number of mice used in a given analysis.

Statistics

Prism 5.0 (GraphPad) and Microsoft Excel were used for all statistical analyses. As the populations tested were not normally distributed, as determined by the KS test, non-parametric analyses were performed, with the exception of the chi-squared test. For comparison of average track speeds, the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was utilized. Where more than two-way comparisons are considered, we ran a non-parametric one-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis) test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post test. For analyses of directional bias and CMJ crossing a chi-squared test was used to assess whether the number of tracks or events displacing or crossing towards and away from medulla was significantly different from a random distribution.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank S. Hestrin for use of his microscope, R. Tsien for use of his vibratome, T. Serwold for providing LN3βxRag2−/− mice, and J. Cyster for sharing Ccr7−/− mice. This work was supported by a Special Fellow Career Development award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LIRE), a Medical Scientist Training Program grant from NIGMS (DYO), and the Mathers Charitable Foundation and general funds of the Institute of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine (ILW), and an R01 grant from NIGMS (RSL).

REFERENCES

- Alfano M, Schmidtmayerova H, Amella CA, Pushkarsky T, Bukrinsky M. The B-oligomer of pertussis toxin deactivates CC chemokine receptor 5 and blocks entry of M-tropic HIV-1 strains. J Exp Med. 1999;190:597–605. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Klein L, Chen Z, Berzins SP, Turley SJ, von Boehmer H, Bronson R, Dierich A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science. 2002;298:1395–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1075958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asperti-Boursin F, Real E, Bismuth G, Trautmann A, Donnadieu E. CCR7 ligands control basal T cell motility within lymph node slices in a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-independent manner. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1167–1179. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajenoff M, Egen JG, Koo LY, Laugier JP, Brau F, Glaichenhaus N, Germain RN. Stromal cell networks regulate lymphocyte entry, migration, and territoriality in lymph nodes. Immunity. 2006;25:989–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajenoff M, Glaichenhaus N, Germain RN. Fibroblastic reticular cells guide T lymphocyte entry into and migration within the splenic T cell zone. J Immunol. 2008;181:3947–3954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakta NR, Oh DY, Lewis RS. Calcium oscillations regulate thymocyte motility during positive selection in the three-dimensional thymic environment. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:143–151. doi: 10.1038/ni1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgne M, Ladi E, Dzhagaov I, Herzmark P, Liao Y, Chakraborty AK, Robey E. The impact of negative selection on thymocyte migration in the medulla. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:823–830. doi: 10.1038/ni.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousso P, Robey E. Dynamics of CD8+ T cell priming by dendritic cells in intact lymph nodes. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:579–585. doi: 10.1038/ni928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahim F, Osmond DG. Migration of bone marrow lymphocytes demonstrated by selective bone marrow labeling with thymidine-H3. Anat Rec. 1970;168:139–159. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091680202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DJ, Kim CH, Butcher EC. Chemokines in the systemic organization of immunity. Immunol Rev. 2003;195:58–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JJ, Pan J, Butcher EC. Cutting edge: developmental switches in chemokine responses during T cell maturation. J Immunol. 1999;163:2353–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YI, Duke-Cohan JS, Ahmed WB, Handley MA, Mann F, Epstein JA, Clayton LK, Reinherz EL. PlexinD1 Glycoprotein Controls Migration of Positively Selected Thymocytes into the Medulla. Immunity. 2008;29:888–898. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbinski J, Gäbler J, Brors B, Tierling S, Jonnakuty S, Hergenhahn M, Peltonen L, Walter J, Kyewski B. Promiscuous gene expression in thymic epithelial cells is regulated at multiple levels. J Exp Med. 2005;202:33–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbinski J, Pinto S, Rösch S, Hexel K, Kyewski B. Promiscuous gene expression patterns in single medullary thymic epithelial cells argue for a stochastic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:657–662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707486105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbinski J, Schulte A, Kyewski B, Klein L. Promiscuous gene expression in medullary thymic epithelial cells mirrors the peripheral self. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1032–1039. doi: 10.1038/ni723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr AG, Anderson SK. Epithelial heterogeneity in the murine thymus: fucose-specific lectins bind medullary epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1985;134:2971–2977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos AM, Bevan MJ. Central tolerance to tissue-specific antigens mediated by direct and indirect antigen presentation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1039–1049. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidos CJ, Weissman IL, Adkins B. Intrathymic maturation of murine T lymphocytes from CD8+ precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7542–7546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogquist KA, Baldwin TA, Jameson SC. Central tolerance: learning self-control in the thymus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:772–782. doi: 10.1038/nri1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsunky H, Inlay MA, Serwold T, Bhattacharya D, Weissman IL. Flk2+ common lymphoid progenitors possess equivalent differentiation potential for the B and T lineages. Blood. 2008;111:5562–5570. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell. 1997;91:661–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurobe H, Liu C, Ueno T, Saito F, Ohigashi I, Seach N, Arakaki R, Hayashi Y, Kitagawa T, Lipp M, et al. CCR7-dependent cortex-to-medulla migration of positively selected thymocytes is essential for establishing central tolerance. Immunity. 2006;24:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan J, Killeen N. CCR7 directs the migration of thymocytes into the thymic medulla. J Immunol. 2004;172:3999–4007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyewski B, Klein L. A central role for central tolerance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:571–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladi E, Schwickert TA, Chtanova T, Chen Y, Herzmark P, Yin X, Aaron H, Chan SW, Lipp M, Roysam B, Robey EA. Thymocyte-dendritic cell interactions near sources of CCR7 ligands in the thymic cortex. J Immunol. 2008;181:7014–7023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind EF, Prockop SE, Porritt HE, Petrie HT. Mapping precursor movement through the postnatal thymus reveals specific microenvironments supporting defined stages of early lymphoid development. J Exp Med. 2001;194:127–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaughtry TM, Baldwin TA, Wilken MS, Hogquist KA. Clonal deletion of thymocytes can occur in the cortex with no involvement of the medulla. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2575–2584. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaughtry TM, Wilken MS, Hogquist KA. Thymic emigration revisited. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2513–2520. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154–159. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-da-Cruz DA, Lepelletier Y, Brignier AC, Smaniotto S, Renand A, Milpied P, Dardenne M, Hermine O, Savino W. Neuropilins, semaphorins, and their role in thymocyte development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:20–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ, Hejazi AS, Wei SH, Cahalan MD, Parker I. T cell repertoire scanning is promoted by dynamic dendritic cell behavior and random T cell motility in the lymph node. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:998–1003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306407101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ, Wei SH, Cahalan MD, Parker I. Autonomous T cell trafficking examined in vivo with intravital two-photon microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2604–2609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2628040100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ, Wei SH, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Two-photon imaging of lymphocyte motility and antigen response in intact lymph node. Science. 2002;296:1869–1873. doi: 10.1126/science.1070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misslitz A, Bernhardt G, Förster R. Trafficking on serpentines: molecular insight on how maturating T cells find their winding paths in the thymus. Immunol Rev. 2006;209:115–128. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misslitz A, Pabst O, Hintzen G, Ohl L, Kremmer E, Petrie HT, Förster R. Thymic T cell development and progenitor localization depend on CCR7. J Exp Med. 2004;200:481–491. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q-T, Tsai PS, Kleinfeld D. MPScope: a versatile software suite for multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;156:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Cyster JG. CC chemokine receptor 7 contributes to Gi-dependent T cell motility in the lymph node. J Immunol. 2007;178:2973–2978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie HT. Cell migration and the control of post-natal T-cell lymphopoiesis in the thymus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:859–866. doi: 10.1038/nri1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie HT, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. Zoned out: functional mapping of stromal signaling microenvironments in the thymus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:649–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin J, Prockop SE, Lepique A, Petrie HT. Critical role for CXCR4 signaling in progenitor localization and T cell differentiation in the postnatal thymus. J Immunol. 2003;171:4521–4527. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porritt HE, Gordon K, Petrie HT. Kinetics of steady-state differentiation and mapping of intrathymic-signaling environments by stem cell transplantation in nonirradiated mice. J Exp Med. 2003;198:957–962. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop SE, Palencia S, Ryan CM, Gordon K, Gray D, Petrie HT. Stromal cells provide the matrix for migration of early lymphoid progenitors through the thymic cortex. J Immunol. 2002;169:4354–4361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwold T, Ehrlich LI, Weissman IL. Reductive isolation from bone marrow and blood implicates common lymphoid progenitors as the major source of thymopoiesis. Blood. 2009;113:807–815. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwold T, Hochedlinger K, Inlay MA, Jaenisch R, Weissman IL. Early TCR expression and aberrant T cell development in mice with endogenous prerearranged T cell receptor genes. J Immunol. 2007;179:928–938. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr TK, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:139–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strnad CF, Carchman RA. Human T lymphocyte mitogenesis in response to the B oligomer of pertussis toxin is associated with an early elevation in cytosolic calcium concentrations. FEBS Lett. 1987;225:16–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q, Adams JY, Tooley AJ, Bi M, Fife BT, Serra P, Santamaria P, Locksley RM, Krummel MK, Bluestone JA. Visualizing regulatory T cell control of autoimmune responses in nonobese diabetic mice. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:83–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen M, Stein JV. How chemokines invite leukocytes to dance. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:953–959. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tykocinski LO, Sinemus A, Kyewski B. The thymus medulla slowly yields its secrets. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:105–122. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara S, Hayes SM, Li L, El-Khoury D, Canelles M, Fowlkes BJ, Love PE. Premature expression of chemokine receptor CCR9 impairs T cell development. J Immunol. 2006;176:75–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno T, Saito F, Gray DH, Kuse S, Hieshima K, Nakano H, Kakiuchi T, Lipp M, Boyd RL, Takahama Y. CCR7 signals are essential for cortex-medulla migration of developing thymocytes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:493–505. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt CM, Raychaudhuri S, Schaefer B, Chakraborty AK, Robey EA. Directed migration of positively selected thymocytes visualized in real time. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt CM, Robey EA. Thymopoiesis in 4 dimensions. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WS, Rosoff PM. Pharmacology of pertussis toxin B-oligomer. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:559–564. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-74-5-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worbs T, Mempel TR, Bolter J, von Andrian UH, Forster R. CCR7 ligands stimulate the intranodal motility of T lymphocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204:489–495. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DE, Cheshier SH, Wagers AJ, Randall TD, Christensen JL, Weissman IL. Cyclophosphamide/granulocyte colony-stimulating factor causes selective mobilization of bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells into the blood after M phase of the cell cycle. Blood. 2001;97:2278–2285. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.