Background: CB2 couples with only Gi protein.

Results: Cross-linking studies using LC-MS/MS and ESI-MS/MS identified three specific CB2-Gαi cross-link sites. MD showed an orientation change from the β2-AR*/Gs geometry makes all cross-links possible.

Conclusion: Second intracellular loop of CB2 interactions are key for Gi complex formation.

Significance: Findings should be relevant for other GPCRs that couple to Gi proteins.

Keywords: Cannabinoid Receptor, G Protein-coupled Receptor (GPCR), Mass Spectrometry (MS), Molecular Dynamics, Signal Transduction

Abstract

In this study, we applied a comprehensive G protein-coupled receptor-Gαi protein chemical cross-linking strategy to map the cannabinoid receptor subtype 2 (CB2)- Gαi interface and then used molecular dynamics simulations to explore the dynamics of complex formation. Three cross-link sites were identified using LC-MS/MS and electrospray ionization-MS/MS as follows: 1) a sulfhydryl cross-link between C3.53(134) in TMH3 and the Gαi C-terminal i-3 residue Cys-351; 2) a lysine cross-link between K6.35(245) in TMH6 and the Gαi C-terminal i-5 residue, Lys-349; and 3) a lysine cross-link between K5.64(215) in TMH5 and the Gαi α4β6 loop residue, Lys-317. To investigate the dynamics and nature of the conformational changes involved in CB2·Gi complex formation, we carried out microsecond-time scale molecular dynamics simulations of the CB2 R*·Gαi1β1γ2 complex embedded in a 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine bilayer, using cross-linking information as validation. Our results show that although molecular dynamics simulations started with the G protein orientation in the β2-AR*·Gαsβ1γ2 complex crystal structure, the Gαi1β1γ2 protein reoriented itself within 300 ns. Two major changes occurred as follows. 1) The Gαi1 α5 helix tilt changed due to the outward movement of TMH5 in CB2 R*. 2) A 25° clockwise rotation of Gαi1β1γ2 underneath CB2 R* occurred, with rotation ceasing when Pro-139 (IC-2 loop) anchors in a hydrophobic pocket on Gαi1 (Val-34, Leu-194, Phe-196, Phe-336, Thr-340, Ile-343, and Ile-344). In this complex, all three experimentally identified cross-links can occur. These findings should be relevant for other class A G protein-coupled receptors that couple to Gi proteins.

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)3 represent excellent drug targets because they are involved in regulating nearly all known physiological functions (1, 2). Class A GPCRs are thought to have a common topology that includes an extracellular N terminus, a transmembrane core formed by a bundle of seven transmembrane α-helices (TMH1–7), three extracellular (EC) and three intracellular (IC) loops that connect these helices, and an intracellular C terminus that begins with a short amphipathic helix lying parallel to the membrane (3–6). Physiologically, GPCRs are activated by ligands (extracellular and membrane-based) that enable the receptors to interact with and activate distinct sets of heterotrimeric G proteins (Gαβγ), as well as β-arrestins (7, 8). Specifically, ligand-activated GPCRs catalyze the exchange of GDP for GTP on the Gα subunit. GTP binding to Gα is predicted to trigger the dissociation of the heterotrimeric G protein into Gα-GTP and free βγ, which are then able to modulate the activity of a multitude of downstream effectors, including adenylate cyclase and ion channels, such as G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium channels (GIRK2 and GIRK4), phospholipase Cβ, and plasma membrane Ca2+ pumps (9–12).

The CB2 receptor belongs to class A of the GPCRs and is mainly expressed in T cells of the immune system (13) and the gastrointestinal system (14, 15). CB2 has also been reported to play an important role in central immune responses during neuropathic pain in mice (16). We have previously performed microseconds long MD simulations of the CB2 endogenous ligand, sn-2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), entering and activating CB2 via the lipid bilayer (17). Activation of CB2 has been shown experimentally to produce coupling to Gαi inhibitory protein (18–20). Although a significant amount of information is available for GPCR-catalyzed activation of G proteins (21), many atomic level details concerning complex formation and signal transduction remain unanswered.

In this work, we studied the formation of a CB2R*·G protein complex both experimentally and computationally. Systematic cross-linking experiments were performed using HgCl2 and a short bi-functional, irreversible chemical cross-linker disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS). These studies yielded three specific contact sites between CB2 and Gαi1 protein, providing new insights into the molecular architecture of the CB2 and Gαi1 interaction. Then, to place these cross-links in a structural perspective and also to explore the dynamic formation of the CB2R*·Gαi1β1γ2 complex, we undertook two independent microsecond-long molecular dynamics simulations of the CB2R*·Gαi1β1γ2 complex in a POPC bilayer. These studies revealed a stepwise formation of the complex that brings all cross-linked pairs into spatial proximity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Transfection and Culture

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere consisting of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Expression plasmids containing the N-terminal FLAG peptide (DYKDDDDK)-tagged human CB2 cannabinoid receptors were stably transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine, according to manufacturer's instructions. Stably transfected cells were selected in culture medium containing 800 μg/ml geneticin. Having established cell lines stably expressing FLAG-CB2 receptors, the cells were maintained in growth medium containing 400 μg/ml geneticin until needed for experiments.

Cross-linking Reactions and Purification of the Cross-linked Protein Complex

The CB2 receptor has been shown to exhibit high constitutive activity (19). For this reason, cross-linking experiments were conducted in the absence of exogenous agonist. For each cross-linker, the cross-linking reactions were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells expressing FLAG-CB2 receptors were collected, and cell membranes were prepared as described previously (22) in 20 mm HEPES buffer containing 150 mm NaCl. After adding cross-linkers at a final concentration of 2 mm, the cell membranes were incubated on ice for 2 h. At the end of incubation, the cross-linking reactions were terminated by adding quench solutions. Subsequently, Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1%, and the membrane suspension was incubated at 4 °C for 2 h by end-to-end gentle rotations. The suspension was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C to remove unsolubilized particles. For anti-FLAG M2 affinity chromatography, the solubilized suspension was incubated with 0.5 ml of anti-FLAG M2-agarose affinity gel at 4 °C for 2 h with gentle rocking. After extensive washing with 20 mm HEPES containing 150 mm NaCl and 1% Triton X-100, the bound CB2 was eluted with 8-column volumes of 0.1 mm glycine HCl, pH 2.5, containing 1% Triton X-100.

In-gel Digestion

The purified CB2 complex was resolved by SDS-PAGE and then subjected to Western blot and Coomassie Blue staining. Both anti-CB2 antibody and anti-G protein antibody were used to identify the band corresponding to the CB2·G protein complex. The CB2·G protein complex band was then excised from Coomassie Blue-stained gel and subjected to enzymatic digestions according to a published protocol (22, 23) with slight modifications. Briefly, the bands were cut into small pieces, destained with 50 mm NH4HCO3/acetonitrile (1:1, v/v), and digested with 10 ng/μl pepsin overnight.

ESI-MS/MS

Peptides from the enzymatic digests were analyzed by ESI-MS/MS as described previously (22). Briefly, peptides from the enzymatic digests were condensed to 1–2 μl with a Speedvac, diluted with 5 μl of 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and analyzed by a Waters CapLC coupled to a Q-TOF API-US mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA). The samples (5 μl) were injected onto a 300-μm × 5-mm PepMap C18 precolumn (LC Packing, Sunnyvale, CA), washed with 5% ACN in 0.1% formic acid at 30 μl/min for 3 min, eluted onto and separated with a 75-μm × 150-mm Atlantis dC18 analytical column (Waters). Separation was started with a 5-min isocratic elution with 95% solvent A (5% ACN with 0.1% formic acid) and 5% solvent B (95% ACN with 0.1% formic acid) and followed by a linear gradient from 5% solvent B to 40% solvent B over 115 min and then from 40% solvent B to 60% solvent B in 30 min. The flow rate on the column was about 200 nl/min. The eluted peptides were directed to a Q-TOF API-US mass spectrometer with a nanoflow source, and MS and MS/MS spectra were acquired by data-dependent scan.

Data analyses were performed with the aid of on-line server MS3D (24, 25). First, the precursor peptide ions from LC-MS/MS were screened by the “Links” program from MS3D. Links calculates the theoretical cross-linking possibilities for the CB2·G protein complex, with information provided about the cross-linkers and protease used and the expected amino acid modifications. The Links program then gives us putative assignments within a defined mass error threshold for a list of input mass (MH+) values. Once the candidates of CB2-G protein cross-linked peptides were obtained, each candidate peptide was further analyzed by the “MS2Links” program from MS3D. MS2Links is a program for assigning tandem MS peak lists generated from the fragmentation of cross-linked, modified, or unmodified peptides. MS2Links calculate the theoretical MS/MS fragment library given information about the identity of the base ion, cross-linkers, desired ion types, and amino acid modifications. MS2Links then returns assignments within a defined mass error threshold for the list of input mass (MH+) values.

Molecular Modeling

CB2 Receptor Model

The CB2 model employed here was taken from our previous microsecond-long simulation of the activation of the CB2 receptor by the endogenous ligand, 2-AG, via the lipid bilayer (17). In this simulation, the ionic lock at the IC ends of TMH3-TMH6 (R3.55–D6.30) was broken within 3 ns of a 2-AG headgroup entry between TMH6 and TMH7 from the lipid bilayer (POPC). To represent the CB2-activated state, we chose coordinates corresponding to time point 184.138 ns from trajectory E in which the salt bridge between TMH3 and TMH6 is broken (17). The α-carbon distance between R3.55(136) and D6.30(240) was 15.2 Å, and the heteroatom distance N (R3.55(136))-O (D6.30(240)) was 12.7 Å (17). In this bundle, the C terminus contains the palmitoylation site at Cys-320 and was truncated after Gly-322.

G Protein Modeling

For this study, the crystal structure of Gαi1β1γ2 (26) was used to dock with CB2 R*. The extreme Gαi1 C terminus is unresolved in this structure, so the undecapeptide NMR structure (27) of this region in Gαt was grafted onto the backbone of residues Lys-345, Asn-346, and Asn-347 (see “Discussion”). The C terminus of Gγ2 is also unresolved in the Gαi1β1γ2 structure. This region was built by homology modeling using the NMR structure of Gγ1 (28) as template and the Maestro module from Schrodinger, LLC, New York.

Lipidation Sites

Palmitic acid was attached to the N terminus of Gαi1 at Cys-3 (29). Myristic acid was attached to Gly-2 of Gαi1 (30), and a geranylgeranyl group was attached to Cys-68 in the Gγ2 C terminus (31).

CB2·Gi Protein Complex

The relative orientations of CB2 R* and Gαi1β1γ2 were based on the β2-AR·Gαsβ1γ2 complex crystal structure (32). To get a relative receptor position, first the activated CB2 receptor was superimposed onto the α carbon atoms of the residues N1.50, D2.50, R3.50, and W4.50 on the β2-AR receptor from the β2-AR·Gαsβ1γ2 complex. To obtain the relative orientation of Gαi1β1γ2 heterotrimer with the CB2 receptor, Gβ1 of Gαi1β1γ2 was superimposed on the α carbon atoms of residues from 51 to 340 of Gβ1 in the Gαsβ1γ2 protein from the β2-AR·Gαsβ1γ2 complex. To relieve steric clashes between CB2 and Gαi1, the whole Gαi1β1γ2 heterotrimer was translated in the z-direction.

Construction of CB2·αi1β1γ2 Complex in POPC Bilayer

The CB2 R*·G protein complex was aligned such that the transmembrane region of the CB2 receptor was centered at the middle of the POPC lipid bilayer and the amphipathic helix 8 was oriented parallel to the plane of the membrane at approximately the lipid/water interface. The model membrane simulation cell was constructed with the replacement method, using scripts derived from CHARMM-GUI (33). The CHARMM22 protein force field with CMAP corrections (34, 35) and the CHARMM 36 lipid force field (36) were used in this study. Parameters for GDP were obtained by analogy to ADP using the nucleic acid force field (37), and those for sn-2-arachidonoylglycerol were derived from the lipid force field (17, 36). The lipidation sites are covalent modifications of their respective amino acids. The parameters for the palmitoylation sites were taken from our earlier simulations (17). Parameters for the myristoylation of Gαi and prenylation of the Gγ2 covalent linkages were taken by analogy with existing CHARMM force field parameters. Given that the primary role for these lipidation sites in these simulations is to anchor their respective proteins to the lipid matrix, no further optimization was performed. All lipidation parameters and patches used to generate the topologies are available upon request. Charge neutrality was enforced with addition of chloride counter ions, and an overall ionic strength of 0.1 m was obtained by adding NaCl. The final system contained 451 POPC lipid molecules, the protein complex, ions, and solvating water molecules with a simulation cell size of 130.0 × 130.0 × 170.6 Å.

Initial Minimization and Equilibration

To relieve poor initial contacts, 500 steps of steepest descent minimization were performed using CHARMM (38), with all heavy atoms of the protein complex fixed. This was followed by 20,000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization using NAMD (39). The fully minimized system was heated in 10 K increments to 310 K with restraints on the protein (force constant of 10 kcal/mol/Å2/5.0 kcal/mol/Å2 for the backbone/side chains and ligands respectively), on the POPC phosphates (force constant of 5.0 kcal/mol/Å2), and a harmonic dihedral restraint on the POPC cis double bond and the glycerol c2 chiral center (force constant of 500 kcal/mol/rad2). At each increment, 500 steps of minimization were performed followed by 20 ps of dynamics at the higher temperature. Equilibration was continued for 100 ps of molecular dynamics, and then the restraints were released in six steps over 1.5ns.

Details of Molecular Dynamics Simulations

For all production runs, NAMD (39) was used. Long range electrostatics were included using PME (40) with a 10-Å short range cutoff, and van der Waals interactions were treated with a switching function and a 10-Å cutoff. The NPT ensemble, as implemented in NAMD, was used to maintain temperature (T = 310 K, damping coefficient of 2 ps−1) and pressure (p = 1.01325 bar, piston period/decay of 100/50 fs). High frequency bonds to hydrogen were restrained using the shake method implemented in NAMD allowing a 2-fs integration time step. Production dynamics was performed on a Blue Gene supercomputer (41) located at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center and on the BSBC cluster at University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Two separate trajectories were run for this complex. Results from these trajectories each at 1 μs in length are reported here. All analyses were performed using visual molecular dynamics (42) and LOOS (43).

Measuring the Angle of Rotation for Gαi1β1γ2 Relative to the CB2 Bundle

To measure the rotation of the G protein under the CB2 receptor throughout the trajectories, the CB2 receptor TMH bundle for each nanosecond of trajectory 1 and trajectory 2 was superimposed on the transmembrane region of the CB2 receptor starting structure (t = 0 ns). The atoms used for the superposition were K1.32(33) to S1.59(60), P2.38(68) to N2.63(93), A3.23(104) to R3.55(136), R4.39(147) to M4.62(170), D5.38(189) to K5.64(215), L6.33(243) to A6.60(270), and K7.33(279) to R7.56(302). Two centers of mass were calculated as follows: 1) the center of mass of Gα Ras-like domain (GTPase domain) backbone atoms Glu-33 to Gly-60 and Thr-181 to Asp-328 (this excludes the C-terminal α5 helix and the N-terminal helix); and 2) the center of mass of the Gβ subunit, Asp-38 to Asn-340 (this excludes the N-terminal helix). The vector between these two centers of mass was calculated for the starting structure (t = 0 ns) and for each 1-ns frame of each trajectory. The angle between the starting structure vector and that of each trajectory time point was projected into the x-y plane and measured.

RESULTS

Mass Spectrometry Identification of CB2 and Gαi Cross-links

To identify contacts between CB2 and Gαi, the CB2 receptor and Gαi were cross-linked with either DSS (Lys-Lys) or HgCl2 (Cys-Cys). Protein complexes were then purified by an M-2 anti-FLAG affinity column. Following SDS-PAGE separation, bands of the cross-linked CB2·Gi complexes were excised and subjected to enzymatic digestion with pepsin. We used the nonspecific enzyme pepsin to digest the cross-linked CB2·Gi protein complex, because there are very few trypsin digestion sites in the CB2 regions in which we were interested. The peptide mixtures resulting from in-gel digestions were analyzed by LC-MS/MS mass spectrometry. Data analysis was performed with the aid of the on-line server MS3D (24). The MS/MS spectrum of each candidate peptide was then manually checked to see whether it is a validated CB2-G protein cross-linked peptide. Several important guidelines were used for identification of cross-linked peptide. 1) The main MS/MS peaks should match fragment ions. 2) Fragment ions from each of the two peptides that are cross-linked should be found. 3) Fragments that contain both peptides and linker should be found.

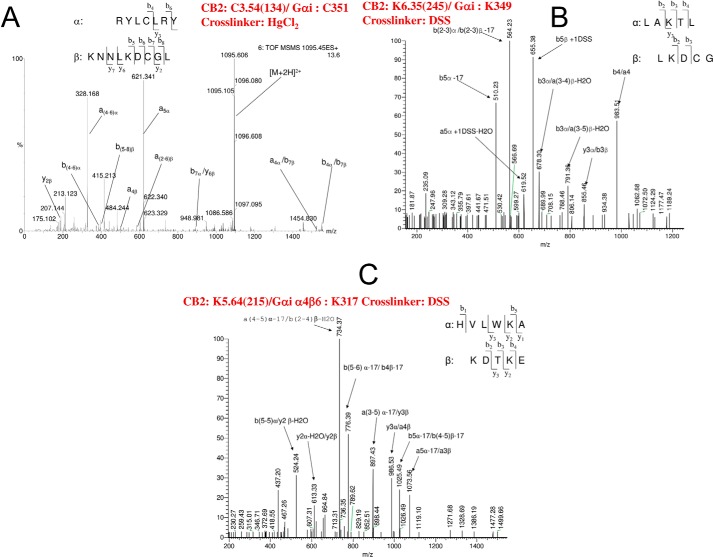

The ESI-MS/MS spectrum of cross-linked peptides between CB2 and Gαi are shown in Fig. 1 (A–C). The fragment ions corresponding to two cross-linked peptides are designated with either the α (peptide from CB2) or β (peptide from Gαi) subscript to indicate the peptide of origin. In Fig. 1A, the spectrum can be assigned to two peptides: peptide α from CB2 with a sequence of RYLCLRY and peptide β from Gαi with a sequence of KNNLKDCGL. The only cysteines in these two sequences that would have been available for cross-linking are Cys-134 in CB2 and Cys-351 in Gαi. Close inspection revealed the presence of three ions that originate from cleavage reactions involving both peptide chains, i.e. b7α/y6β, a4α/b7β, and b4α/b7β.

FIGURE 1.

A, ESI-MS/MS spectrum of a cross-linked peptide between CB2 and Gαi is presented here. The [M + 2H]2+ peak at m/z 1095.105 (M = 2188.21) was selected as the precursor ion with a collision energy of 35 eV. The peptide α from CB2 and the peptide β from Gαi cross-linked between Cys-134 and Cys-351. B, ESI-MS/MS spectrum of a cross-linked peptide between CB2 and Gαi is presented here. The [M + 2H]2+ peak at m/z 609.30 (M = 1216.60) was selected as the precursor ion with a collision energy of 35 eV. The peptide α from CB2 and the peptide β from Gαi cross-linked between Lys-245 and Lys-349. C, ESI-MS/MS spectrum of a cross-linked peptide between CB2 and Gαi is presented here. The [M + 2H]2+ peak at m/z 755.89 (M = 2264.67) was selected as the precursor ion with a collision energy of 35 eV. The peptide α from CB2 and the peptide β from Gαi cross-linked between Lys-215 and Lys-317.

In Fig. 1B, the spectrum can be assigned to two peptides: peptide α from CB2 with a sequence of LAKTL and peptide β from Gαi with a sequence of LKDCG. The only lysines in these two sequences that would have been available for cross-linking were Lys-245 in CB2 and Lys-349 in Gαi. The spectrum was closely examined for the possible presence of fragment ions originating from cleavages involving both peptide chains. There are five ions that originate from cleavage reactions involving both peptide chains. For example, y3α/b3β demonstrates clearly the cross-link between Lys-245 in CB2 and Lys-349 in Gαi.

In Fig. 1C, the spectrum can be assigned to two peptides as follows: peptide α from CB2 with a sequence of HVLWKA and peptide β from Gαi with a sequence of KDTKE. There are eight ions that originate from cleavage reactions involving both peptide chains. Among these, y2α-H2O/y2β demonstrates directly the cross-link between Lys-215 in CB2 and Lys-317 in Gαi.

Initial CB2 R*/Gαi1β1γ2 Protein Dock

Orientation of Gαi1β1γ2 Protein

Our initial dock of CB2 R* with Gαi1β1γ2 protein (Fig. 2) was based on the crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor in complex with the Gs protein (32). In this structure, the C-terminal α5 helix of Gαs is inserted between TMH3, TMH5, and TMH6, pointing toward the TMH7/Hx8 “elbow” region. TMH5 is packed closely with the C-terminal α5 helix. This orientation of Gαs places the N terminus of Gαs below TMH3 and TMH4, while the receptor IC2 loop fits in the region between the C and N termini of Gαs.

FIGURE 2.

Initial 2-AG/CB2 R*·Gαi1β1γ2 complex is presented here. This dock was based on the crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor in complex with Gαs protein (32). The CB2 receptor is shown in orange bound to 2-AG (VdW green carbons and red oxygens). The Gαi1 subunit of the Gαi1β1γ2 heterotrimer is in magenta; Gβ1 is in blue, and Gγ2 is in cyan. The palmitic and myristic acids attached to Gαi1 are shown in VdW colored magenta. The geranylgeranyl group attached to Gγ2 is shown in VdW and colored cyan. GDP is bound between the helical and Ras-like domains of Gαi1. Here, GDP is shown in VdW display with carbons, nitrogens, and oxygens colored green, blue, and red, respectively.

Cysteine Cross-link between TMH3 and Gαi1 C-terminal α5 Helix

The Cα-Cα distance range for formation of a cysteine cross-link using HgCl2 is 7–10 Å (44, 45). The cysteine cross-link identified by LC-MS/MS analysis from the HgCl2 (Cys-Cys) cross-linking study was found to be between C3.54(134) and Cys-351 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-3 residue). The Cα-Cα distance between these two residues in the initial CB2·Gαi1β1γ2 complex was found to be 10.6 Å, which is just 0.6 Å outside the range for a cysteine cross-link formation using HgCl2. The Cα positions of the cross-linked residues (colored yellow) at t = 0 ns in the context of the whole complex is shown in Fig. 3A. Fig. 3B presents a close-up view.

FIGURE 3.

A, this figure shows the spatial location of the three cross-links identified between CB2 R* and Gαi1 protein in the starting structure for MD. B, Cα positions of the two residues linked using HgCl2, C3.54(134) on CB2 and Cys-351 on the Gαi1 α-5 helix (i-3 residue) are shown here in yellow. C, Cα positions of two residues cross-linked with DSS, K6.35(245) on CB2 TMH6 and Lys-349 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-5 residue on C-terminal) are shown in cyan. D, Cα positions of another pair of residues cross-linked with DSS, K5.64(215) on CB2 TMH5 and Lys-317 on the Gαi1 α4β6 loop are colored red. The intracellular end of TMH6 that sterically obstructs this cross-link in the initial complex is colored magenta.

Lys-Lys Cross-links

The spacer arm length, N-N distance reported for DSS is 11.4 Å (46). l-Lysine measures 6.4 Å from the α carbon to nitrogen (47). This makes 24.2 Å the maximum Cα-Cα distance for formation of a Lys-Lys cross-link. The first lysine cross-link identified by LC-MS/MS analysis was between K6.35(245) on TMH6 and Lys-349 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-5 residue on C-terminal). In the initial CB2·Gαi1β1γ2 complex, these residues were 17 Å apart (Cα-Cα), which is within the range for formation of the DSS (Lys-Lys) cross-link. In addition, the space between these two residues provided no steric obstruction to cross-link formation. The Cα position of the cross-linked residues (colored cyan) at t = 0 ns in the context of the whole complex is shown in Fig. 3A. Fig. 3C presents a close-up view.

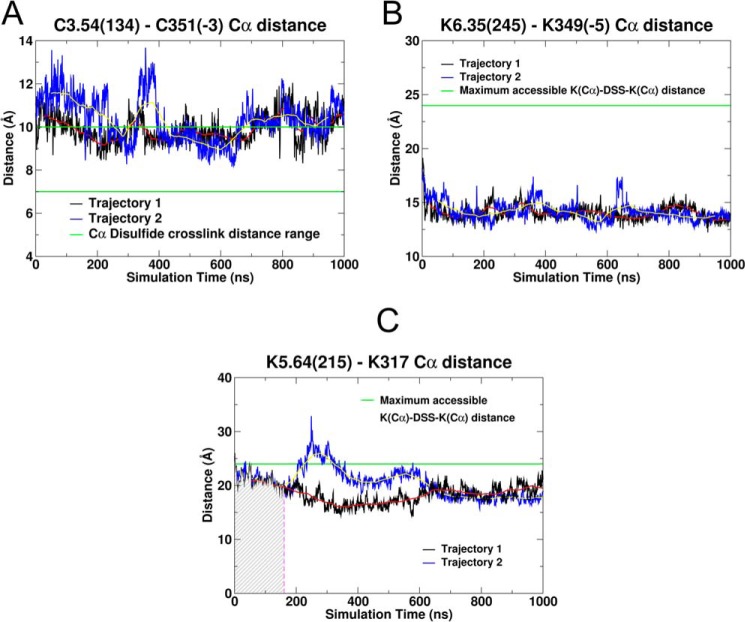

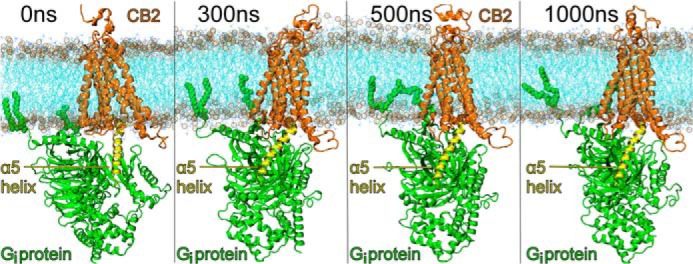

The initial Cα-Cα distance for the second Lys-Lys cross-link between K5.34(215) on TMH5 and Lys-317 in the α4β6 region of Gαi1 was 24.5 Å. This distance is only 0.3 Å outside the range for the formation of these Lys-Lys cross-links. However, it is not sterically possible to form this cross-link even if the distance was lower because the space between these two residues is blocked by the intracellular end of TMH6. This is illustrated in Fig. 3D, where the intracellular extension of the TMH6 (shown in magenta) provides this steric obstruction (t = 0 ns). In Fig. 3D, the Cα positions of K5.64 and Lys-317 are colored red. This suggests that during the dynamic interaction of the two proteins, this region may change conformation allowing these residues to be cross-linked. Our MD simulations of the CB2 R*·Gαi1β1γ2 protein complex embedded in a POPC bilayer test this hypothesis. Fig. 4 illustrates the full system for trajectory 1 simulated over time, including the POPC bilayer (lipid acyl chains, cyan; phosphate atoms in phospholipid headgroup, open gold circles), the CB2 receptor (orange), and Gαi1β1γ2 protein (green) with the Gαi1 α5 helix shown in yellow.

FIGURE 4.

This figure illustrates the full system for trajectory 1 simulated over time here, including the POPC bilayer (fatty acid acyl chains, cyan; phosphate atoms in phospholipid headgroup, open gold circles), the CB2 receptor (orange), and Gαi1β1γ2 protein (green) with the Gαi1 α5 helix shown in yellow.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

MD calculations reported here used the results of cross-linking experiments to validate the receptor·G protein complex that emerged from our simulations. Cross-linking information was not used as a constraint for these simulations. It is also important to note that because of pepsin digestion, it is impossible to know whether all three cross-links occurred in a single CB2·Gαi complex and whether each cross-link was found in a different CB2·Gαi complex or any other permutation between these two extremes. In other words, we do not know in advance if all three distance constraints implied by the cross-linking are ever met simultaneously. In the starting structure for the MD simulations, the Cys-Cys cross-link is just outside the range for cross-link formation. One of the Lys-Lys cross-links is within range to form in the initial CB2·Gi protein complex similar to β2-AR*·Gαsβ1γ2 complex. The second Lys-Lys cross-link, however, is not initially possible due to steric obstruction from the IC extension of TMH6.

Results from our two independent 1-μs long trajectories suggest that conformational changes occur in both CB2 and Gαi1β1γ2 during the first 300–400 ns of the trajectories, as these proteins optimize their interaction with each other; Gαi1β1γ2, re-orients with respect to the receptor and uses a CB2 IC-2 loop interaction to register the two proteins into new orientations, whereas TMH5 and TMH6 on CB2 move outward, reorganizing the associated IC-3 loop. These changes are discussed in detail below.

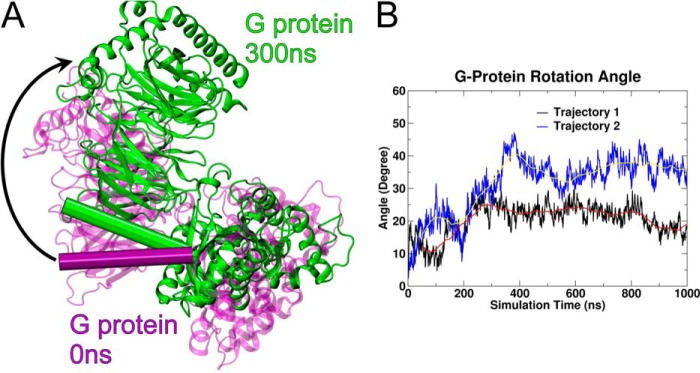

Gαi1β1γ2 Re-orientation relative to CB2

Rotation of Gαi1β1γ2

Fig. 5A illustrates the change about the z axis in Gαi1β1γ2 orientation relative to CB2 that occurs within the first 300 ns in trajectory 1. Here, the perspective is from the receptor interface toward the cytoplasm through the TMH bundle (the CB2 receptor is omitted from the view for clarity). A clockwise rotation of ∼25° can be clearly seen by considering the change in position of the N-terminal helix of Gαi1 (Fig. 5A, shown in cylinder display: purple cylinder (t = 0 ns) versus green cylinder (t = 300 ns)). A similar rotation occurs in trajectory 2 within the first 400 ns (not shown). Fig. 5B shows the evolution of the rotation angle for trajectory 1 (black) and trajectory 2 (blue). The red and yellow lines in Fig. 5B represent the running averages. It is clear here that the distances plateau at about 300 ns for trajectory 1 and 400 ns for trajectory 2. Although the rotation angle for trajectory 1 stabilizes to ∼25°, the rotation for trajectory 2 is ∼35°.

FIGURE 5.

A, this figure illustrates for trajectory 1 that a rotation of the entire Gαi1β1γ2 protein (t = 0 ns, purple; t = 300 ns, green) relative to CB2 occurs along the z axis. Here the view is from the receptor interface toward the cytoplasm. The CB2 TMH bundle has been turned off for clarity. A clockwise rotation of ∼25° can be clearly seen by considering the change in position of the N-terminal helix of Gαi1 (shown in cylinder display: purple cylinder (t = 0 ns) versus green cylinder (t = 300 ns). A similar clockwise rotation occurred in trajectory 2 (not shown). B, rotation angle for Gαi1β1γ2 relative to the CB2 TMH bundle over time in trajectory 1 (black line) and trajectory 2 (blue line) is illustrated here. The red and yellow lines represent the running average over 100 ns for trajectory 1 and 2, respectively.

Change in Gαi1 C-terminal α5 Helix Tilt

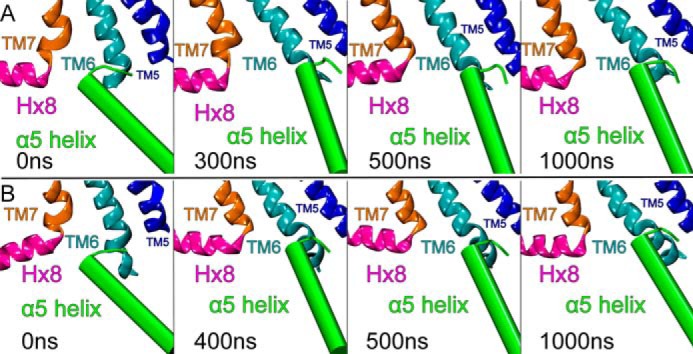

Fig. 6 illustrates that another important change in Gαi1β1γ2 orientation relative to CB2 occurred during the MD runs. Here, the intracellular ends of TMH5-6-7 and Hx8 are shown with TMH-1-2-3-4 omitted for clarity. The C-terminal α5 helix of Gαi1 is shown in cylinder display (Fig. 6, green). In trajectory 1 (Fig. 6A), the C-terminal α5 helix of Gαi1 changed from a tilt toward the TMH7-Hx8 elbow (as seen in the crystal structure of the β2-AR (32)) to a tilt more aligned with the membrane normal, bringing the extreme C terminus near the IC end of TMH6. This change occurred over the first 300 ns of the MD production run and was maintained through the rest of the trajectory (t = 300 ns → t = 1000 ns). Results were similar for trajectory 2 (Fig. 6B) except that the change in orientation happened over the first 400 ns. In both trajectories, the α5 helix changes its orientation by pivoting about a point near the center of the α5 helix in a rigid body motion. The helix also does not roll nor undergo a face shift.

FIGURE 6.

Another important change in Gαi1β1γ2 orientation relative to CB2 occurred during the MD runs. Here, the intracellular ends of TMH5-6-7 and Hx8 are shown with TMH-1-2-3-4 omitted for clarity. The C-terminal α5 helix of Gαi1 is shown in cylinder display (green). A, in trajectory 1, the C-terminal α5 helix of Gαi1 changed from a tilt toward the TMH7-Hx8 elbow (as seen in the crystal structure of the β2-AR (32)) to a tilt more aligned with the membrane normal, bringing the extreme C terminus near the IC end of TMH6. This change occurred over the first 300 ns of the MD production run and was maintained throughout the rest of the trajectory (t = 300 ns → t = 1000 ns). B, results were similar for trajectory 2 except that the change in orientation happened over the first 400 ns.

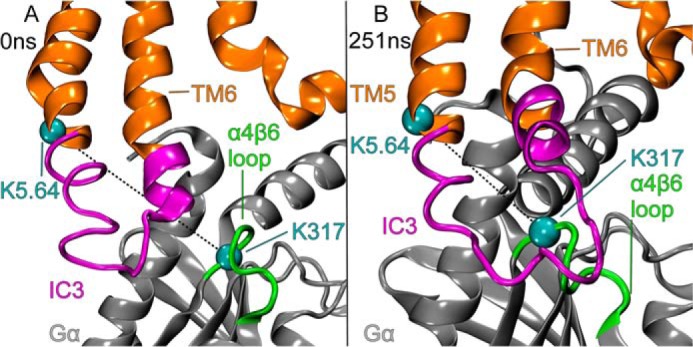

IC-2-Gαi1β1γ2 “Registering” Interaction

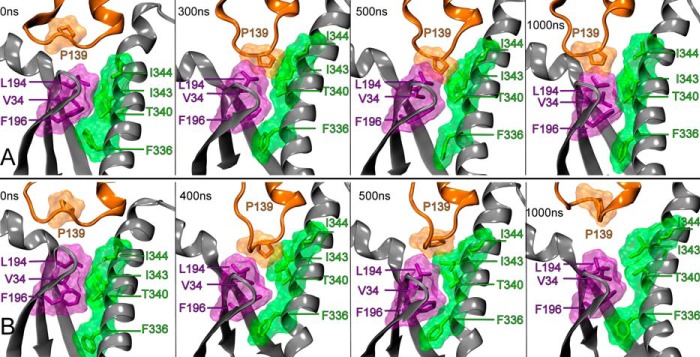

The rotation of Gαi1β1γ2 about the z axis (illustrated in Fig. 5) promotes an interaction between the IC-2 loop of CB2 and a hydrophobic pocket on Gαi1 (see Fig. 7). This hydrophobic pocket is composed of residues immediately after the Gαi1 N terminus (Val-34), residues on the Gαi1 β1 and β2 sheets (Leu-194 and Phe-196), as well as residues on the Gαi1 α5 helix (Ile-344, Ile-343, Thr-340, and Phe-336). In our initial CB2 R*/Gαi1β1γ2 dock (based on the β2-AR/Gαsβ1γ2 crystal structure), the IC-2 loop of CB2 was located between the N-terminal helix and C-terminal helix of Gαi1, on top of the loop connecting the β2 and β3 sheets. Fig. 7 (t = 0 ns) illustrates the hydrophobic pocket and the orientation of the receptor IC-2 loop relative to this pocket at the beginning of each trajectory. As the result of the rotation of Gαi1β1γ2 about the z axis discussed previously (see Fig. 5), an IC-2 loop residue, Pro-139, establishes a hydrophobic interaction with the hydrophobic pocket residues on Gαi1 within the first 300 ns of the trajectory 1 (Fig. 7A) and 400 ns of trajectory 2 (Fig. 7B). Over both 1-μs trajectories, Pro-139 entered and exited the hydrophobic pocket several times, but the rotation of Gαi1β1γ2 about the y axis ceased once this registering interaction was established around 300 ns for trajectory 1 and 400 ns for trajectory 2.

FIGURE 7.

IC-2/Gαi1β1γ2 registering interaction. The interaction between the CB2 IC-2 loop residue (Pro-139, colored orange) and a hydrophobic pocket on Gαi1 is shown here. This hydrophobic pocket is composed of residue(s) immediately after the Gαi1 N terminus (Val-34, colored purple), residue(s) on the Gαi1 β1, and β2 sheets (Leu-194 and Phe-196, colored purple), as well as residues on the Gαi1 α5 helix (Phe-336, Thr-340, Ile-343, and Ile-344, colored green). A, this shows the interaction of Pro-139 with the hydrophobic pocket at selected time points over 1 μs in trajectory 1. The first interaction of Pro-139 with the hydrophobic pocket occurred at t = 300 ns. B, Pro-139 interaction with the hydrophobic pocket at selected time points over 1 μs in trajectory 2 is shown here. The first interaction with the hydrophobic pocket in trajectory 2 occurred at t = 400 ns.

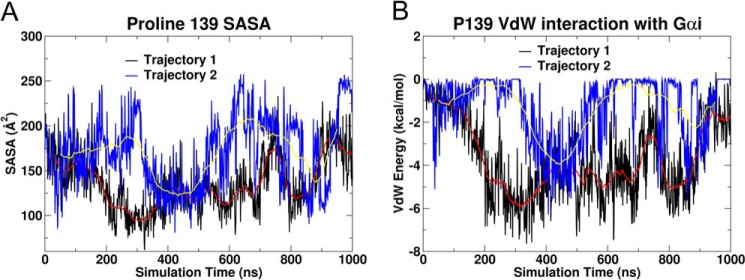

The interaction of Pro-139 with the hydrophobic pocket can also be followed by considering the solvent-accessible surface area of Pro-139 over the course of each trajectory or the interaction energy of Pro-139 with the hydrophobic pocket over the course of the trajectory. At the start of the trajectory 1, the solvent-accessible surface area of Pro-139 was 200 Å2 (t = 0 ns), but it decreased to 80 Å2 during the period between 250 and 300 ns (black line in Fig. 8A) and for trajectory 2, the solvent-accessible surface area of Pro-139 was 200 Å2 (t = 0 ns), but decreased to 100 Å2 during the period between 350 and 400 ns (blue line in Fig. 8A). The interaction energy between Pro-139 and the hydrophobic pocket was close to zero at the start of trajectory 1, but it dropped to −7 kcal/mol between 250 and 300 ns (black line Fig. 8B). For trajectory 2, the interaction energy dropped to −5 kcal/mol between 350 and 400 ns (blue line, Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

These plots (trajectory 1, black; trajectory 2, blue) show the change in the solvent-accessible surface area (A) and van der Waals interaction energy for the Pro-139 (CB2 IC-2 loop) interaction with the Gαi1 hydrophobic pocket (B). The red and yellow lines represent the running average over 100 ns for trajectory 1 and trajectory 2, respectively. Over the 1000-ns trajectory, Pro-139 entered and exited the hydrophobic pocket several times, but the rotation of Gαi1β1γ2 about the z axis ceased once this anchoring interaction was first established at 300 ns for trajectory 1 and 400 ns for trajectory 2 (see Fig. 7 for further detail).

Shape of α5 Helix C-terminal Portion

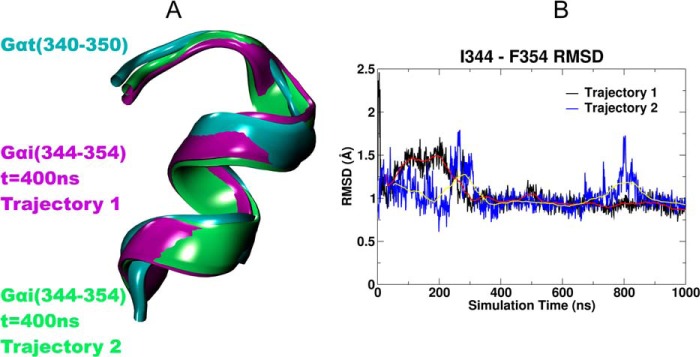

The crystal structure of Gαi1β1γ2 is missing the last 10 residues of the Gαi1 α5 helix. The three-dimensional structure of the transducin (Gt) α subunit C-terminal undecapeptide Gαt 340IKENLKDCGLF350 was determined by Kisselev et al. (27) using transferred nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy, while it was bound to photoexcited rhodopsin (Protein Data Bank 1AQG). Light activation of rhodopsin caused a dramatic shift from a disordered conformation of Gαt (340–350) to a binding motif with a helical turn followed by an open reverse turn centered at Gly-348, with a helix-terminating C capping motif of an αL type. We used this NMR structure to complete the missing C terminus of Gαi1 in our initial model of the CB2 G protein complex. Fig. 9A shows a comparison of the Gαt (340–350) NMR structure (cyan) with the corresponding last 10 residues of Gαi1 at t = 400 ns in each simulation (trajectory 1, purple; trajectory 2, green). It is clear that in both the trajectories, the two segments have very similar shapes. We calculated the r.m.s.d. of the Cα's of the last 10 residues of Gαi1 in our simulations versus the NMR structure. The r.m.s.d. plot in Fig. 9B shows that this region of the C terminus of Gαi1 undergoes changes during the period (t = 0 ns → t = 300 ns) for trajectory 1 and (t = 0 ns → t = 400 ns) for trajectory 2 when the tilt of the Gαi1 α5 helix is changing, but the r.m.s.d. reaches a stable value by 300 ns for trajectory 1 and 400 ns for trajectory 2 and remains low thereafter.

FIGURE 9.

A, this figure shows a comparison of the Gαt (residues 340–350) NMR structure (27) (cyan) with the corresponding last 10 residues of Gαi1 at t = 400 ns in trajectory 1 (purple) and trajectory 2 (green). It is clear that the two segments from both the trajectories have very similar shapes. B, we calculated the r.m.s.d. of the α carbons of the last 10 residues of Gαi1 in our simulation versus the NMR structure. The r.m.s.d. plot versus simulation time shows that this region of the C terminus of Gαi1 undergoes changes during the period t = 0 ns → t = 300 ns for trajectory 1 (black line) and t = 0 ns → t = 40 ns for trajectory 2 (blue line) when the tilt of the Gαi1 α5 helix is changing, but the r.m.s.d. reaches a stable value by 300 ns for trajectory 1 and 400 ns for trajectory 2 and remains low thereafter. The red and yellow lines represent the running average over 100 ns for trajectory 1 and 2, respectively.

Why Does the α5 Helix Change Its Tilt?

There are two differences between the CB2·Gαi1β1γ2 and β2-AR·Gαsβ1γ2 complexes that may contribute to the change in tilt of the α5 helix. These are Gα sequence differences and GPCR sequence differences.

Sequence Differences, α5 Helix

The reorientation of the Gαi1 α5 helix illustrated in Fig. 5 may be attributable in part to sequence differences between Gαs and Gαi. The sequences of the last 10 residues of the various isoforms of Gα (Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαo, Gαt, Gαs, Gαq, etc.) have high homology; however, there is an important difference at the i-4 position. For the Gαi proteins, this position is occupied by a negatively charged residue (Asp in Gαi1 and Gαi2; Glu in Gαi3). For Gαs, however, this position is an uncharged residue (Gln-390(i-4)). Fig. 10 illustrates the difference in the interaction of the extreme C terminus of Gαi1 with the receptor that occurs partly as a consequence of this sequence difference. In the β2-AR (see Fig. 10A), R3.50 has an aromatic stacking interaction with Tyr-391(i-3) on the Gαs α5 helix. Although our initial dock of Gαi with CB2 R* mimicked this (see Fig. 10B), during the initial 300–400 ns of the trajectories, the α5 helix changed its tilt angle to be more aligned with the membrane normal. This tilt change allows CB2 R3.50 to now interact with Asp-350(i-4) on the Gαi α5 helix (see Fig. 10C), whereas CB2 R3.55 interacts with Leu-353(i-1) on the Gαi α5 helix. This latter interaction is a van der Waals interaction.

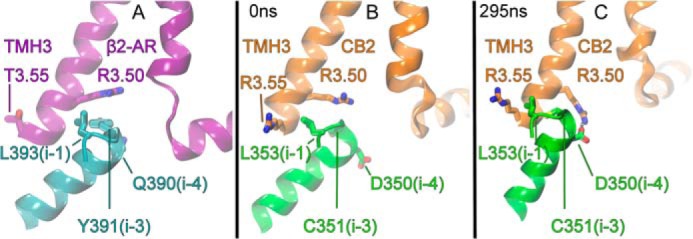

FIGURE 10.

This figure illustrates the interaction between receptor residues at the intracellular end of TMH3 with the three (i-1, i-3 and i-4) residues of the C-terminal α5 helix of Gαi1. A, this figure shows that R3.50 of the β2-AR receptor interacts with Tyr-391(i-3) on Gαs (32). B, this figure shows that in the initial CB2·Gαi1β1γ2 complex, R3.50 interacts with Cys-351(i-3) on Gαi1 and R3.55 interacts with Leu-353(i-1). Here, the tilt of the α5 helix is very similar to that of Gαs in A. C, however, after 295 ns in trajectory 1, the tilt angle of the Gαi1 α5 helix has changed permitting CB2 R3.50 to form a salt bridge with Asp-350(i-4) on Gαi1, whereas the hydrocarbon portion of R3.55 has a VdW interaction with Leu-353(i-1). Note here that to establish these interactions, the α5 helix changes its tilt angle to be more aligned with the membrane normal.

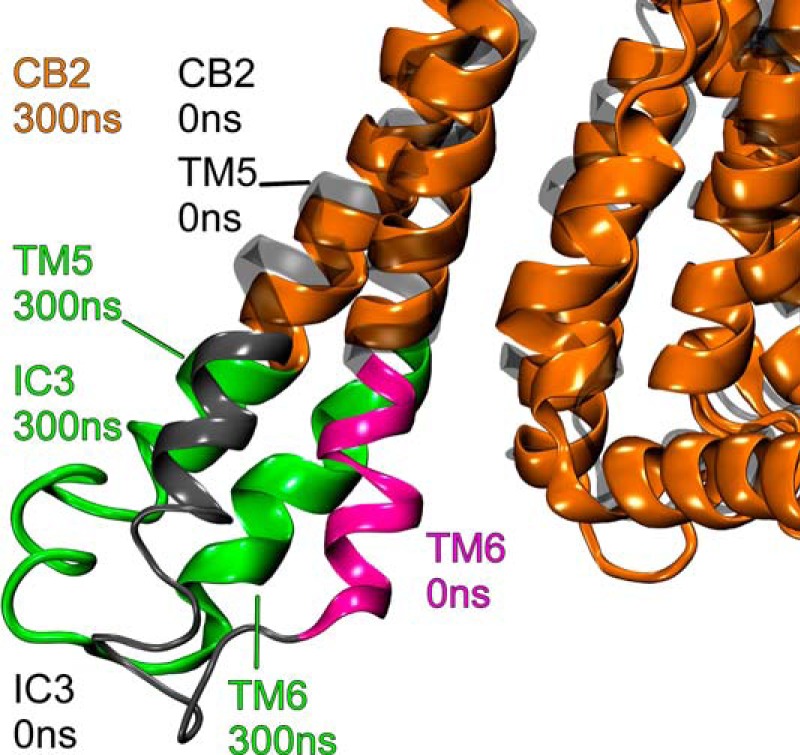

Sequence Differences, TMH5-TMH6 Movement

To accommodate the re-orientation of the Gαi1 α5 helix and the rotation of Gαi1β1γ2, CB2 undergoes an outward movement of TMH5-TMH6, and the associated IC-3 loop moves away from the CB2 TMH bundle. This is illustrated in Fig. 11 for trajectory 1. This is facilitated by the fact that both TMH5 and TMH6 have hinge points that allow these helices to move away from the TMH bundle when CB2 is activated (17). TMH5 hinges at G5.53(204), whereas the hinge point for TMH6 is at G6.38(248). Fig. 12 shows that the position of the CB2 IC-3 loop relative to the Gαi1 α4β6 loop changes before 300 ns in trajectory 1. Here, the G protein has clearly undergone a rotation that places the α4β6 loop of Gαi1 near the IC-3 loop of CB2. This movement also removes the steric obstruction to the formation of the Lys-Lys cross-link between K5.34(215) on TMH5 and Lys-317 in the α4β6 region of Gαi1 that existed at the outset of the simulation (see Fig. 3D). Similar results were obtained with trajectory 2.

FIGURE 11.

To accommodate the re-orientation of the Gαi1 α5 helix and the rotation of Gαi1β1γ2, CB2 undergoes an outward movement of TMH5-TMH6 and the associated IC-3 loop moves away from the CB2 TMH bundle. This is illustrated in Fig. 11 for trajectory 1 from the TMH4-5 perspective. The CB2 structure at t = 0 ns is colored gray here, and the CB2 structure at t = 300 ns is colored orange.

FIGURE 12.

This figure shows that the position of the CB2 IC-3 loop relative to the Gαi1 α4β6 loop changes before 300 ns in trajectory 1. Here, the G protein has clearly undergone a rotation that places the α4β6 loop of Gαi1 near the IC-3 loop of CB2. This movement also removes the steric obstruction to the formation of the Lys-Lys cross-link between K5.34(215) on TMH5 and Lys-317 in the α4β6 region of Gαi1 that existed at the outset of the simulation (see Fig. 3D). Similar results were obtained with trajectory 2.

Cross-link Correlations

Cysteine Cross-link between TMH3 and C-terminal Gαi1 α5 Helix

To test whether experimentally obtained cross-links were possible in trajectories 1 and 2, we considered Cα-Cα distances for each pair of linked residues. We compared these distances to the range of Cα-Cα distances over which the cross-linking has been shown to form. In some trajectories, this distance was below the cutoff distance for the entire trajectory. In others, there were only regions of the trajectory that were below the cutoff. We begin here by discussing each of the cross-links individually. At the end of this section, we assess in what percentage of the trajectories is the Cα-Cα distance below the cutoff at the same time. Fig. 13A shows a plot of the Cα-Cα distance between C3.54(134) on CB2 and Cys-351 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-3 residue on C-terminal) for both trajectories. This plot has the distance range for cysteine cross-link formation indicated by the green lines in Fig. 13. This distance was 10.6 Å in the starting structure, which was just 0.6 Å outside the cross-link range. The distance does decrease into the range of 7–10 Å, for multiple times in both trajectories. As a result, we conclude that our MD simulations suggest that the formation of a Cys-Cys cross-link is possible.

FIGURE 13.

Plot of Cα-Cα distance as a function of simulation time is shown here for the three cross-links reported here. Trajectory 1 is shown in black, and trajectory 2 is in blue. The red and yellow lines represent the running average over 100 ns for trajectory 1 and trajectory 2 respectively. A, Cα-Cα distance between C3.54(134) and Cys-351 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-3 residue on C-terminal) is shown here. The green lines at 7 and 10 Å correspond to the distance range for cross-link formation between two cysteines using HgCl2. B, Cα-Cα distance between K6.35(245) and Lys-349 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-5 residue on C-terminal) is shown here. The green lines at 24.2 Å are the maximum Cα distance to form a cross-link formation between two lysines using DSS. C, Cα-Cα distance between K5.64(215) and Lys-317 on the Gαi1 α4β6 loop is shown here. The green lines at 24.2 Å are the maximum Cα distance to form a cross-link formation between two lysines using DSS. The hatched area before 200 ns represents that part of trajectory during for which the intracellular end of TMH6 sterically obstructs this cross-link. This corresponds to the section of TMH6 colored magenta in Fig. 3D.

Cross-link between TMH6 and C-terminal α5 Helix of Gαi1

Fig. 13B shows a plot of the Cα-Cα distance for the Lys-Lys cross-link between K6.35(245) on CB2 and Lys-349 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-5 residue on C-terminal) for both the trajectories. The green line in Fig. 13B at 24.2 Å indicates the distance below which a cross-link would be possible. The plot shows that this distance remained around 15 Å during the entire 1-μs MD simulation for both the trajectories. In addition, there were no steric obstructions of this interaction present at any time in either trajectory. Therefore, we conclude that our MD simulations suggest that the formation of this Lys-Lys cross-link is possible.

Cross-link between TMH5 and the Gαi1 α4β6 Loop

We have indicated above that one consequence of the Gαi1β1γ2 rotation relative to CB2 is that TMH5-IC3-TMH6 moves away from the TMH bundle at the IC side in the first 300 ns for trajectory 1 and 400 ns for trajectory 2. Prior to this movement, it is structurally impossible to cross-link K5.34(215) on TMH5 and Lys-317 in the α4β6 region of Gαi1 even though the Cα-Cα distance between these residues is below the 24.2Å cutoff for cross-link formation. Fig. 13C shows a plot of the Cα-Cα distance for this Lys-Lys cross-link for both trajectories. That section of the simulation for which the cross-link is structurally not possible is indicated by the hashed region in Fig. 13C. For trajectory 1 (Fig. 13C, black line), once the structural interference is removed as TMH5-IC3-TMH6 moves away from the bundle, the cross-link is possible at all other time points. Trajectory 2 (Fig. 13C, blue line) does have one region that goes above the allowed distance after the steric obstruction is cleared (200–375 ns). After this region, the Cα-Cα distance for trajectory 2 remains below the cutoff. Therefore, our MD simulations suggest that the formation of this Lys-Lys cross-link is also possible.

Finally, we assessed at 1-ns intervals for both trajectories, those times for which all three sets of Cα-Cα distances were below the cutoff (and therefore possible) at the same time. We found that in trajectory 1, this percentage was 60.8%, although for trajectory 2, this percentage was 33.4%.

DISCUSSION

High resolution x-ray structures have been obtained for multiple class A (“rhodopsin-like”) GPCRs (3–6, 48–56), various G protein heterotrimers (Gαβγ) (26, 57, 58), and isolated Gα subunits in different functional states (59–61). Combined with biochemical and biophysical data, these structures reveal a surface on Gα that is predicted to face the intracellular side of GPCRs. Information about the nature of this interface has been obtained via x-ray crystallography and chemical cross-linking studies. At present, there is only one crystal structure of a GPCR·protein complex available (32), which shows the interaction of β2-AR with the Gs protein after GDP has dissociated from the Gα subunit. This structure represents an empty state that exists between the GDP-bound and GTP-bound G protein, artificially stabilized by a nanobody, insertion of which was necessary for crystallization (32).

Chemical cross-linking studies of protein-protein interactions can identify pairs of residues that come close enough to each other to form a respective cross-link. The identification of multiple cross-link sites can provide information about the relative orientation of the two interacting proteins.

In this paper, a comprehensive GPCR-Gαi protein chemical cross-linking strategy was applied with the goal of ascertaining the orientation of the CB2 receptor relative to Gαi1. These experiments revealed three cross-links as follows: 1) a cysteine cross-link between TMH3 residue C3.54(134) and Cys-351 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-3 residue); 2) a lysine cross-link between TMH6 residue K6.35(245) and Lys-349 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-5 residue); and 3) a lysine cross-link between TMH5 residue K5.64(215) and Lys-317 on the Gαi1 α4β6 loop. An examination of the initial complex we constructed to a mimic the β2-AR*·Gαsβ1γ2 x-ray crystal structure (32) revealed that one of these cross-links (K6.35(245) to Lys-349) is possible in the initial complex. A second cross-link (C3.54(134) to Cys-351) is only 0.6 Å above the Cα-Cα distance limit for cross-linking in the initial complex. But the third cross-link was sterically impossible in the initial complex. This suggested that either the orientation of the G protein with respect to a GPCR varies depending on the receptor and G protein to be complexed or that the orientation of Gαsβ1γ2 with respect to the β2-AR* in the crystal structure changes after GDP leaves the Gαs subunit, as has occurred in the β2-AR*·Gαsβ1γ2 crystal structure.

To understand the origins of the experimental cross-links between CB2 and Gαi identified in this paper, we undertook microsecond time scale molecular dynamic simulations of the CB2 R*·Gαi1β1γ2 complex in a POPC bilayer. We show here that when two MD runs of the CB2 R*·Gαi1β1γ2 complex in lipid are initiated using the same G protein orientation (including the angle of the Gαi1 α5 helix) as seen in the β2-AR*/Gαsβ1γ2 crystal structure, rearrangements ensue fairly quickly in each. There is a gross clockwise rotation of the entire G protein underneath CB2 R* during the first 300 ns (trajectory 1) or 400 ns (trajectory 2) of the production runs. This rotation ceases once an interaction is established between the IC-2 loop residue, Pro-139 and a hydrophobic pocket on Gαi1 formed by residues Val-34, Leu-194, Phe-196, Phe-336, Thr-340, Ile-343, and Ile-344.

A change in the tilt of the Gαi1 α5 helix also occurs early in the trajectories facilitated by the outward movement of TMH6 and TMH5 at their IC ends. The change in tilt allows R3.50 on CB2 to form a salt bridge with Asp-350(i-4) on the Gαi1 α5 helix.

Importance of the Gαi1α5 Helix and the Change in Its Tilt Angle

In this cross-linking study, a cysteine cross-link was formed between TMH3 residue C3.54(134) and Cys-351 on the Gαi1 α5 helix (i-3 residue). The extreme C terminus was one of the first regions within Gα identified as being critical to receptor-promoted activation. Hamm et al. (62) first demonstrated that synthetic peptides corresponding to the C terminus of Gαt could block rhodopsin-promoted activation, suggesting that the C terminus of Gα is a critical receptor-binding site. Alanine-scanning experiments confirmed that the C terminus/α5 helix was essential for the rhodopsin-promoted activation of Gαt (63). In many early G protein crystal structures, the extreme C terminus of Gα was unresolved. The first three-dimensional structure of the transducin (Gt) α subunit C-terminal undecapeptide Gαt 340IKENLKDCGLF350 bound to photoexcited rhodopsin registered in the Protein Data Bank was determined by using transferred nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (27). Light activation of rhodopsin caused a dramatic shift from a disordered conformation of Gαt (340–350) to a binding motif with a helical turn followed by an open reverse turn centered at Gly-348, with a helix-terminating C capping motif of an α L type. Docking of the NMR structure to the GDP-bound x-ray structure of Gt reveals that photoexcited rhodopsin promotes the formation of a continuous helix over residues 325–346 terminated by the C-terminal helical cap with a unique cluster of crucial hydrophobic side chains. Subsequently, this C-terminal region has been resolved in three GPCR crystal structures as follows: 1) the bovine opsin*·Gα·C-terminal peptide complex (64); 2) meta II rhodopsin in complex with an 11-amino acid C-terminal fragment derived from Gα (two residues mutated) (65); and 3) the β2-AR*·Gαsβ1γ2 complex (32). In each of these structures, the shape of the extreme C terminus is quite similar to the original NMR structure. In this work, this NMR structure was used to complete the Gαi1 structure that was docked in CB2 R*. The r.m.s.d. plot in Fig. 9B shows that the shape of the last 10 residues in the C-terminal region has a low r.m.s.d. after the first 300 ns of production simulation for trajectory 1 and 400 ns for trajectory 2 when compared with the NMR structure.

We also report here that the insertion angle of the Gαi1 α5 helix changed from its starting angle (which mimicked the β2-AR*·Gαsβ1γ2 complex (32)). Two reasons for this change are the position of the IC end of TMH5 in CB2 R* and a key sequence difference between Gαi and Gαs at the i-3 position on the Gαi α5 helix. One striking difference between the β2-AR and CB2 sequences is that the β2-AR has the highly conserved P5.50, whereas CB2 lacks this proline in TMH5 (L5.50 in CB2). In the β2-AR*·Gαsβ1γ2 complex (32), TMH6 has moved away from the TMH bundle and broken the ionic lock (R3.50/E6.30), thus exemplifying an activated GPCR. The proline kink region of TMH5 flexes but moves TMH5 toward the TMH bundle interior. When the α5 helix of Gαs inserts in this activated structure, it must insert in an opening formed by TMH6's outward movement. This region extends over to the elbow region of TMH7-Hx8. In the case of CB2, the C-terminal α5 helix of Gαi1 can insert into a wider opening, one formed by the TMH5 and TMH6 outward movement. This in turn allows the angle of insertion to change in CB2.

R3.50 has been shown to be crucial for CB2 signal transduction. Feng and Song (66) reported no stimulation of agonist-induced [35S]GTPγS binding for the R3.50A mutant in CB2. We show here that the change in the tilt angle of the α5 helix also permits formation of a salt bridge between R3.50 on CB2 and Asp-350(i-4) on the Gαi α5 helix. Asp-350(i-4) occupies a position in the C terminus of Gαi that has an important divergence from Gαs. For the Gαi, this position is occupied by a negatively charged residue (Asp in Gαi1 and Gαi2; Glu in Gαi3). For Gαs, however, this position is an uncharged residue (Gln-390(i-4)). Fig. 10 illustrates the difference in the interaction of the extreme C terminus of Gαi1 with the receptor that occurs partly as a consequence of this sequence difference. In the β2-AR (see Fig. 10A), R3.50 has an aromatic stacking interaction with Tyr-391(i-3) on the Gαs α5 helix. Although our initial dock of Gαi with CB2 R* mimicked this (see Fig. 10B), after 295 ns in trajectory 1, the tilt of the α5 helix has changed such that Gαi1 moves toward TMH5-TMH6, allowing R3.50 to now interact with Asp-350(i-4) (see Fig. 10C), although the hydrophobic part of R3.55 interacts with Leu-353(i-1). A similar change occurred in trajectory 2.

Second Intracellular Loop Interaction with Gα Protein

Interactions between GPCR IC-2 loops and G protein have been shown to be critical in GPCR/G protein coupling for numerous receptors. The IC-2 loop of the muscarinic M3 receptor has been shown to interact with the N-terminal region of Gαq protein (67). IC-2 interactions also have been shown to be critical for coupling in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSH) with Gαs (68). In the β2-AR*/Gαsβ1γ2 crystal structure, IC-2 loop residue, Phe-139, inserts into an aromatic/hydrophobic pocket on Gαs composed of His-41, Val-217, Phe-129, Phe-376, Arg-380, and Ile-383 on the Gαs C-terminal region and Gαs, β2, and β3 sheets (see Fig. 4c in Ref. 32). The importance of this interaction is underscored by mutagenesis studies that demonstrate that a β2-AR F139A mutation significantly impairs β2-AR coupling to Gαs (69). We show here that Gαi1β1γ2 rotation about the z axis ceased once the IC-2 loop residue, Pro-139, establishes a hydrophobic interaction with the hydrophobic pocket residues on Gαi1 (Figs. 6 and 7). The two proteins appear to be in register once this interaction occurs. Consistent with this idea, no further Gαi1β1γ2 rotation occurs in either trajectory. In support of the importance of this interaction, Zheng et al. (70) have reported that a P139A mutation in CB2 results in the loss of coupling with Gαi.

Third Intracellular Loop Interaction with the α4β6 Region of Gα

Our chemical cross-linking strategy led to a DSS (Lys-Lys) cross-link between the TMH5 residue K5.64(215) and Lys-317 on the Gαi1 α4β6 loop. In the MD simulations reported here, this cross-link becomes possible only after Gαi1β1γ2 rotation under CB2 (see Figs. 4, 5, 11, and 12). The importance of α4/β6 loop residues to the GPCR·G protein complex formation has been shown for multiple GPCRs. Slessareva et al. (71) have shown that the Gαi1 α4 helix-α4/β6 loop are involved in 5-HT1a, 5-HT1b, and muscarinic M2 receptor interactions. For the rhodopsin·transducin (Gαt) complex, residues in the Gαt α4β6 loop (Arg-310 to Lys-313) were shown to cross-link with residues in the IC-3 loop of rhodopsin using a photoactivatable reagent, N-[(2-pyridyldithio)ethyl],4-azidosalicylamide (72). For the rat M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (M3R)·Gαq complex system, a cross-link has been reported between a D321C mutation on α4β6 loop of Gαq and a K7.58(548)C mutation on M3R. Here the cross-linking agent was a short bi-functional, irreversible chemical cross-linker bis-maleimisoethane (67).

Conclusions

The result of this study is a CB2 R*·Gαi1β1γ2 complex in which the proteins are in the correct register as indicated by chemical cross-linking studies. The next stage of this project will be the study of the changes that complex formation with CB2 R* induces in Gαi1β1γ2. Our ultimate goal will be the activated state of Gαi1β1γ2 in which GDP has been released.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the many helpful discussions with Dr. Klaus Gawrisch on this project.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DA011551 (to Z. H. S.), GM095496 (to A. M. G.), and DA003934 and DA021358 (to P. H. R.).

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- CB2

- cannabinoid receptor Sub-type 2

- R*

- activated receptor

- POPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine

- β2-AR

- β2-adrenergic receptor

- MD

- molec ular dynamics

- IC

- intracellular

- TMH

- transmembrane helix

- DSS

- disuccinimidyl suberate

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- VdW

- van der Waals

- Hx8

- helix 8

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pierce K. L., Premont R. T., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Regard J. B., Sato I. T., Coughlin S. R. (2008) Anatomical profiling of G protein-coupled receptor expression. Cell 135, 561–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hanson M. A., Roth C. B., Jo E., Griffith M. T., Scott F. L., Reinhart G., Desale H., Clemons B., Cahalan S. M., Schuerer S. C., Sanna M. G., Han G. W., Kuhn P., Rosen H., Stevens R. C. (2012) Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science 335, 851–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu H., Wacker D., Mileni M., Katritch V., Han G. W., Vardy E., Liu W., Thompson A. A., Huang X. P., Carroll F. I., Mascarella S. W., Westkaemper R. B., Mosier P. D., Roth B. L., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. (2012) Structure of the human κ-opioid receptor in complex with JDTic. Nature 485, 327–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manglik A., Kruse A. C., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Mathiesen J. M., Sunahara R. K., Pardo L., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K., Granier S. (2012) Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature 485, 321–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang C., Jiang Y., Ma J., Wu H., Wacker D., Katritch V., Han G. W., Liu W., Huang X. P., Vardy E., McCorvy J. D., Gao X., Zhou X. E., Melcher K., Zhang C., Bai F., Yang H., Yang L., Jiang H., Roth B. L., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C., Xu H. E. (2013) Structural basis for molecular recognition at serotonin receptors. Science 340, 610–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2005) Transduction of receptor signals by β-arrestins. Science 308, 512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K. (2008) Structural insights into G-protein-coupled receptor activation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 734–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clapham D. E., Neer E. J. (1997) G protein βγ subunits. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 37, 167–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smrcka A. V. (2008) G protein βγ subunits: central mediators of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2191–2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin Y., Smrcka A. V. (2011) Understanding molecular recognition by G protein βγ subunits on the path to pharmacological targeting. Mol. Pharmacol. 80, 551–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hamm H. E. (1998) The many faces of G protein signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 669–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Galiègue S., Mary S., Marchand J., Dussossoy D., Carrière D., Carayon P., Bouaboula M., Shire D., Le Fur G., Casellas P. (1995) Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur. J. Biochem. 232, 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Storr M., Gaffal E., Saur D., Schusdziarra V., Allescher H. D. (2002) Effect of cannabinoids on neural transmission in rat gastric fundus. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 80, 67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wright K. L., Duncan M., Sharkey K. A. (2008) Cannabinoid CB2 receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: a regulatory system in states of inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153, 263–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Racz I., Nadal X., Alferink J., Baños J. E., Rehnelt J., Martín M., Pintado B., Gutierrez-Adan A., Sanguino E., Manzanares J., Zimmer A., Maldonado R. (2008) Crucial role of CB(2) cannabinoid receptor in the regulation of central immune responses during neuropathic pain. J. Neurosci. 28, 12125–12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hurst D. P., Grossfield A., Lynch D. L., Feller S., Romo T. D., Gawrisch K., Pitman M. C., Reggio P. H. (2010) A lipid pathway for ligand binding is necessary for a cannabinoid G protein-coupled receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17954–17964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Demuth D. G., Molleman A. (2006) Cannabinoid signalling. Life Sci. 78, 549–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bouaboula M., Desnoyer N., Carayon P., Combes T., Casellas P. (1999) Gi protein modulation induced by a selective inverse agonist for the peripheral cannabinoid receptor CB2: implication for intracellular signalization cross-regulation. Mol. Pharmacol. 55, 473–480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bouaboula M., Poinot-Chazel C., Marchand J., Canat X., Bourrié B., Rinaldi-Carmona M., Calandra B., Le Fur G., Casellas P. (1996) Signaling pathway associated with stimulation of CB2 peripheral cannabinoid receptor. Involvement of both mitogen-activated protein kinase and induction of Krox-24 expression. Eur. J. Biochem. 237, 704–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Preininger A. M., Meiler J., Hamm H. E. (2013) Conformational flexibility and structural dynamics in GPCR-mediated G protein activation: a perspective. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 2288–2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang R., Kim T. K., Qiao Z. H., Cai J., Pierce W. M., Jr., Song Z. H. (2007) Biochemical and mass spectrometric characterization of the human CB2 cannabinoid receptor expressed in Pichia pastoris–importance of correct processing of the N terminus. Protein Expr. Purif. 55, 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jensen O. N., Wilm M., Shevchenko A., Mann M. (1999) Sample preparation methods for mass spectrometric peptide mapping directly from 2-DE gels. Methods Mol. Biol. 112, 513–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu E. T., Hawkins A., Kuntz I. D., Rahn L. A., Rothfuss A., Sale K., Young M. M., Yang C. L., Pancerella C. M., Fabris D. (2008) The collaboratory for MS3D: a new cyberinfrastructure for the structural elucidation of biological macromolecules and their assemblies using mass spectrometry-based approaches. J. Proteome Res. 7, 4848–4857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schilling B., Row R. H., Gibson B. W., Guo X., Young M. M. (2003) MS2Assign, automated assignment and nomenclature of tandem mass spectra of chemically cross-linked peptides. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 14, 834–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wall M. A., Coleman D. E., Lee E., Iñiguez-Lluhi J. A., Posner B. A., Gilman A. G., Sprang S. R. (1995) The structure of the G protein heterotrimer Giα1β1γ2. Cell 83, 1047–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kisselev O. G., Kao J., Ponder J. W., Fann Y. C., Gautam N., Marshall G. R. (1998) Light-activated rhodopsin induces structural binding motif in G protein α subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 4270–4275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kisselev O. G., Downs M. A. (2003) Rhodopsin controls a conformational switch on the transducin γ subunit. Structure 11, 367–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parenti M., Viganó M. A., Newman C. M., Milligan G., Magee A. I. (1993) A novel N-terminal motif for palmitoylation of G-protein α subunits. Biochem. J. 291, 349–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Preininger A. M., Van Eps N., Yu N. J., Medkova M., Hubbell W. L., Hamm H. E. (2003) The myristoylated amino terminus of Gα(i)(1) plays a critical role in the structure and function of Gα(i)(1) subunits in solution. Biochemistry 42, 7931–7941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sanford J., Codina J., Birnbaumer L. (1991) γ-Subunits of G proteins, but not their α- or β-subunits, are polyisoprenylated. Studies on post-translational modifications using in vitro translation with rabbit reticulocyte lysates. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 9570–9579 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rasmussen S. G., DeVree B. T., Zou Y., Kruse A. C., Chung K. Y., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Chae P. S., Pardon E., Calinski D., Mathiesen J. M., Shah S. T., Lyons J. A., Caffrey M., Gellman S. H., Steyaert J., Skiniotis G., Weis W. I., Sunahara R. K., Kobilka B. K. (2011) Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature 477, 549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jo S., Kim T., Iyer V. G., Im W. (2008) CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 1859–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. MacKerell A. D., Jr., Bashford D., Bellott M., Dunbrack R. L., Jr., Evanseck J. D., Field M. J., Fischer S., Gao J., Guo H., Ha S., Joseph-McCarthy D., Kuchnir L., Kuczera K., Lau F. T. K., Mattos C., Michnick S., Ngo T., Nguyen D. T., Prodhom B., Reiher W. E., 3rd, Roux B., Schlenkrich M., Smith J. C., Stote R., Straub J., Watanabe M., Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J., Yin D., Karplus M. (1998) All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586–3616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mackerell A. D., Jr., Feig M., Brooks C. L., 3rd (2004) Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1400–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klauda J. B., Venable R. M., Freites J. A., O'Connor J. W., Tobias D. J., Mondragon-Ramirez C., Vorobyov I., MacKerell A. D., Jr., Pastor R. W. (2010) Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 7830–7843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Foloppe N., MacKerell A. D., Jr. (2000) All-atom empirical force field for nucleic acids: I. Parameter optimization based on small molecule and condensed phase macromolecular target data. J. Comput. Chem. 21, 86–104 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brooks B. R., Brooks C. L., 3rd, Mackerell A. D., Jr., Nilsson L., Petrella R. J., Roux B., Won Y., Archontis G., Bartels C., Boresch S., Caflisch A., Caves L., Cui Q., Dinner A. R., Feig M., Fischer S., Gao J., Hodoscek M., Im W., Kuczera K., Lazaridis T., Ma J., Ovchinnikov V., Paci E., Pastor R. W., Post C. B., Pu J. Z., Schaefer M., Tidor B., Venable R. M., Woodcock H. L., Wu X., Yang W., York D. M., Karplus M. (2009) CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 1545–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M. L., Darden T. A., Lee J., Pedersen L. G. (1995) A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gara A., Blumrich M. A., Chen D., Chiu G. L., Coteus P., Giampapa M. E., Haring R. A., Heidelberger P., Hoenicke D., Kopcsay G. V., Liebsch T. A., Ohmacht M., Steinmacher-Burow B. D., Takken T., Vranas P. (2005) Overview of the blue gene/L system architecture. IBM J. Res. Dev. 49, 195–212 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Romo T. D., Grossfield A. (2009) LOOS: An Extensible Platform for Structural Analysis of Simulations. in 31st Annual International Conference of the IEEE EMBS, Minneapolis, September 2–6, 2009, pp. 2332–2335, Springer-Verlag, Minneapolis, MN: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Soskine M., Steiner-Mordoch S., Schuldiner S. (2002) Cross-linking of membrane-embedded cysteines reveals contact points in the EmrE oligomer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12043–12048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fass D. (2012) Disulfide bonding in protein biophysics. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 63–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Green N. S., Reisler E., Houk K. N. (2001) Quantitative evaluation of the lengths of homobifunctional protein cross-linking reagents used as molecular rulers. Protein Sci. 10, 1293–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Banks J. L., Beard H. S., Cao Y., Cho A. E., Damm W., Farid R., Felts A. K., Halgren T. A., Mainz D. T., Maple J. R., Murphy R., Philipp D. M., Repasky M. P., Zhang L. Y., Berne B. J., Friesner R. A., Gallicchio E., Levy R. M. (2005) Integrated modeling program, applied chemical theory (IMPACT). J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1752–1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Palczewski K., Kumasaka T., Hori T., Behnke C. A., Motoshima H., Fox B. A., Le Trong I., Teller D. C., Okada T., Stenkamp R. E., Yamamoto M., Miyano M. (2000) Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289, 739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rasmussen S. G., Choi H. J., Rosenbaum D. M., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Edwards P. C., Burghammer M., Ratnala V. R., Sanishvili R., Fischetti R. F., Schertler G. F., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K. (2007) Crystal structure of the human β2 adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 450, 383–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jaakola V. P., Griffith M. T., Hanson M. A., Cherezov V., Chien E. Y., Lane J. R., Ijzerman A. P., Stevens R. C. (2008) The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science 322, 1211–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Warne T., Serrano-Vega M. J., Baker J. G., Moukhametzianov R., Edwards P. C., Henderson R., Leslie A. G., Tate C. G., Schertler G. F. (2008) Structure of a β1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 454, 486–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wu B., Chien E. Y., Mol C. D., Fenalti G., Liu W., Katritch V., Abagyan R., Brooun A., Wells P., Bi F. C., Hamel D. J., Kuhn P., Handel T. M., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. (2010) Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science 330, 1066–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Haga K., Kruse A. C., Asada H., Yurugi-Kobayashi T., Shiroishi M., Zhang C., Weis W. I., Okada T., Kobilka B. K., Haga T., Kobayashi T. (2012) Structure of the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor bound to an antagonist. Nature 482, 547–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Granier S., Manglik A., Kruse A. C., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K. (2012) Structure of the δ-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature 485, 400–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kruse A. C., Hu J., Pan A. C., Arlow D. H., Rosenbaum D. M., Rosemond E., Green H. F., Liu T., Chae P. S., Dror R. O., Shaw D. E., Weis W. I., Wess J., Kobilka B. K. (2012) Structure and dynamics of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature 482, 552–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. White J. F., Noinaj N., Shibata Y., Love J., Kloss B., Xu F., Gvozdenovic-Jeremic J., Shah P., Shiloach J., Tate C. G., Grisshammer R. (2012) Structure of the agonist-bound neurotensin receptor. Nature 490, 508–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lambright D. G., Sondek J., Bohm A., Skiba N. P., Hamm H. E., Sigler P. B. (1996) The 2.0 A crystal structure of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature 379, 311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nishimura A., Kitano K., Takasaki J., Taniguchi M., Mizuno N., Tago K., Hakoshima T., Itoh H. (2010) Structural basis for the specific inhibition of heterotrimeric Gq protein by a small molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13666–13671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Coleman D. E., Sprang S. R. (1998) Crystal structures of the G protein Giα1 complexed with GDP and Mg2+: a crystallographic titration experiment. Biochemistry 37, 14376–14385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tesmer J. J., Sunahara R. K., Gilman A. G., Sprang S. R. (1997) Crystal structure of the catalytic domains of adenylyl cyclase in a complex with Gsα.GTPγS. Science 278, 1907–1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lambright D. G., Noel J. P., Hamm H. E., Sigler P. B. (1994) Structural determinants for activation of the α-subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature 369, 621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hamm H. E., Deretic D., Arendt A., Hargrave P. A., Koenig B., Hofmann K. P. (1988) Site of G protein binding to rhodopsin mapped with synthetic peptides from the α subunit. Science 241, 832–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Onrust R., Herzmark P., Chi P., Garcia P. D., Lichtarge O., Kingsley C., Bourne H. R. (1997) Receptor and βγ binding sites in the α subunit of the retinal G protein transducin. Science 275, 381–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Scheerer P., Park J. H., Hildebrand P. W., Kim Y. J., Krauss N., Choe H. W., Hofmann K. P., Ernst O. P. (2008) Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature 455, 497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Choe H. W., Kim Y. J., Park J. H., Morizumi T., Pai E. F., Krauss N., Hofmann K. P., Scheerer P., Ernst O. P. (2011) Crystal structure of metarhodopsin II. Nature 471, 651–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Feng W., Song Z. H. (2003) Effects of D3.49A, R3.50A, and A6.34E mutations on ligand binding and activation of the cannabinoid-2 (CB2) receptor. Biochem. Pharmacol. 65, 1077–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hu J., Wang Y., Zhang X., Lloyd J. R., Li J. H., Karpiak J., Costanzi S., Wess J. (2010) Structural basis of G protein-coupled receptor-G protein interactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 541–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ulloa-Aguirre A., Uribe A., Zariñán T., Bustos-Jaimes I., Pérez-Solis M. A., Dias J. A. (2007) Role of the intracellular domains of the human FSH receptor in G(αS) protein coupling and receptor expression. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 260, 153–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Moro O., Lameh J., Högger P., Sadée W. (1993) Hydrophobic amino acid in the i2 loop plays a key role in receptor-G protein coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 22273–22276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zheng C., Chen L., Chen X., He X., Yang J., Shi Y., Zhou N. (2013) The second intracellular loop of the human cannabinoid CB2 receptor governs G protein coupling in coordination with the carboxyl-terminal domain. PloS one 8, e63262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Slessareva J. E., Ma H., Depree K. M., Flood L. A., Bae H., Cabrera-Vera T. M., Hamm H. E., Graber S. G. (2003) Closely related G-protein-coupled receptors use multiple and distinct domains on G-protein α-subunits for selective coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50530–50536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Cai K., Itoh Y., Khorana H. G. (2001) Mapping of contact sites in complex formation between transducin and light-activated rhodopsin by covalent cross-linking: use of a photoactivatable reagent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4877–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]