Abstract

Clay pots were analyzed as devices for sampling the outdoor resting fraction of Anopheles gambiae Giles (Diptera: Culicidae) and other mosquito species in a rural, western Kenya. Clay pots (Anopheles gambiae resting pots, herein AgREPOTs), outdoor pit shelters, indoor pyrethrum spray collections (PSC), and Colombian curtain exit traps were compared in collections done biweekly for nine intervals from April to June 2005 in 20 housing compounds. Of 10,517 mosquitoes sampled, 4,668 An. gambiae s.l. were sampled in total of which 63% were An. gambiae s.s. (46% female) and 37% were An. arabiensis (66% female). The clay pots were useful and practical for sampling both sexes of An. gambiae s.l. Additionally, 617 An. funestus (58% female) and 5,232 Culex spp. (males and females together) were collected. Temporal changes in abundance of An. gambiae s.l. were similarly revealed by all four sampling methods, indicating that the clay pots could be used as devices to quantify variation in mosquito population density. Dispersion patterns of the different species and sexes fit well the negative binomial distribution, indicating that the mosquitoes were aggregated in distribution. Aside from providing a useful sampling tool, the AgREPOT also may be useful as a delivery vehicle for insecticides or pathogens to males and females that enter and rest in them.

Keywords: Anopheles gambiae, sampling, outdoor resting, clay pots

Sampling adult stages of Anopheles vectors of human malaria is an important and necessary process for estimating vector population density, obtaining an adequate sample to measure the sporozoite infection rate, and quantifying the effects of interventions directed against vector populations. Various sampling methods were reviewed in Service (1993). One of the most commonly used sampling methods is the indoor knockdown spray, sometimes called the pyrethrum spray catch or pyrethrum spray collection (PSC) (Service 1993). It requires that the lives of the residents of the houses are temporarily disrupted, because they must leave their house during the very early hours of the morning when the spraying and retrieval of the knocked down mosquitoes (“the catch”) is performed. Cookware and food also must be moved out of the house before the spray is accomplished, and a drop cloth must be spread on the floor and furniture to catch falling mosquitoes. The PSC method is necessarily biased toward endophilic, female mosquitoes in particular physiological states (especially, blood-fed and gravid conditions). Such sampling would underestimate population density when vector populations are more exophagic and exophilic; and it would necessarily avoid the outdoor fraction of the population and does not yield high numbers of males. Additionally, house-based sampling may be confounded when the houses have been treated in some way that might repel mosquitoes or reduce their tendency to remain and rest in them, such as when the inner walls have been sprayed with an insecticide or when insecticide-treated nets are present in the house.

Sampling the outdoor “resting” population of mosquitoes has been accomplished through hand or mechanical aspiration of vegetation and other environments offering harborage and resting sites (Service 1993), and deployment of various resting shelters and devices such as walk-in red boxes (Meyer 1985), diurnal resting shelters (Morris 1981), pit shelters dug into the ground (Service 1993), fiber pots (Komar Ludwig, et al. 1995), and woven baskets (Harbison et al. 2006). Resting Anopheles gambiae s.l. Giles females have been notoriously difficult to sample outside of houses owing to the problem of locating adults in their highly dispersed, natural resting sites. A similar difficulty exists for males of this species, the biology of which is rather poorly known owing in part to sampling difficulties.

Hand aspiration from natural and artificial resting sites, use of motorized aspirators or sweep-nets on vegetation, and aspirations from woven baskets are some methods (Mutero et al. 1984, Githeko et al. 1996, Harbison et al. 2006). Artificial resting devices, such as shelters, offer the advantage of providing concentrated sites for collections and provide representative samples that can be used for quantitative work, if mosquitoes actually use them. It is more difficult to find mosquitoes that rest outdoors in natural sites because outdoor populations are usually widely distributed over large areas and not concentrated in discrete units. In Tanzania, the outdoor population of An. gambiae s.l. was distributed among dense growth of salt bush, Atriplex halimus L., and also in crevices in the ground, whereas Anopheles pharoensis Theobald rested in less dense growths of salt bush (Smith 1961). Clarke et al. (1980) showed that in the Kisumu area of Kenya substantial numbers of the An. gambiae s.l. (subsequently shown to be both An. arabiensis and An. gambiae s.s.) rested in grain stores constructed of maize, Zea mays L., or millet (Poaceae) stalks plastered with mud for walls and roof. Later studies showed that An. arabiensis more commonly rested in granaries and other outdoor structures than did Anopheles gambiae s.s., which were found predominantly indoors (Githeko et al. 1996). In areas lacking such granaries, outdoor resting sites are unknown; adults of An. arabiensis occurred in cracks and crevices of brick pits and cracks in the ground (Service 1993). Harbison et al. (2006) showed that woven baskets in which a black cloth had been placed provided a resting site for An. gambiae when the baskets were placed indoors and therefore served as a useful indoor device for sampling purposes, but they did not deploy them outside of houses for a comparison.

Clearly, there is a need for improved methods for sampling the outdoor, resting fraction of An. gambiae s.l. populations. In this study,weanalyze and verify the utility of clay pots as low-cost, noninsecticide based devices for sampling the outdoor resting fraction of An. gambiae and other mosquito species in a study area in western Kenya. We compare the clay pot sampling method with three standard sampling methods: the indoor PSC method, a house exiting method (Colombian curtains hung at the eaves of houses), and another outdoor method (pit shelters dug into the earth near houses).

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in the adjacent areas of Asembo (Rarieda Division, Bondo District) and Seme (Kombewa Division, Kisumu District), ≈40 km west of the city of Kisumu in western Kenya (34° E, 0°S). Extensive studies of malaria infection in humans and mosquitoes, vector biology, and insecticide-treated bed-nets have been conducted in this area (Gimnig et al. 2003, and references therein). Human inhabitants are mainly of the Luo ethnic group with the population dispersed among rural compounds (homesteads). Compounds consist of one or more houses (usually three to five houses) and surrounding farmland. Most people live in traditional houses constructed with wood, a mud floor, and four mud walls, and a roof of either grass thatch or corrugated iron. Rainfall is seasonally bimodal, with the heaviest rains falling from March through May and the shorter rainy season occurring in November and December. The region is characterized by low-lying areas and temporary streams that flood during the rainy season. The predominant malaria vectors in the areas are Anopheles gambiae s.s., Anopheles arabiensis, and Anopheles funestus, with the primary species of human malaria in the region being Plasmodium falciparum (Beier et al. 1990, Bloland et al. 1999).

Four clusters of compounds were chosen. Each cluster consisted of five compounds. One house in each compound was randomly selected for mosquito sampling, giving a total of 20 houses for this study. In the selection process, houses with similar designs were chosen, with the following criteria: occupied by people, thatch roof, and typical size. Indoor resting mosquitoes were sampled using the PSC method between 0530 and 0630 hours, following the procedure described in Gimnig et al. (2003). Mosquitoes exiting the house were sampled with Colombian curtains as described in Mathenge et al. (2001). Mosquitoes resting outdoors were sampled between 0630 and 0730 hours from constructed pit shelters (1.54 m in length, 1.23 m in width, and 1.85 m in depth), by using hand-held mouth aspirators and intensive visual search. These pits were placed within 20 m of the house chosen for sampling, and were located in the shade of trees. Three clay pots (see below) were placed in shaded sites within 5 m of each sampled house. Sampling was conducted biweekly for nine intervals from April to July 2005; there was no sampling during 12 to 24 June (i.e., interval 7) owing to a medical emergency. PSC was done once per interval from the house. The Colombian curtain sampling was done overnight before the PSC, by using the same house. The curtain was emptied at 3-h intervals beginning at 9:00 p.m., until dawn. Each set of three pots was sampled twice during the same week, on the morning of the PSC and on the subsequent morning. Thus, six pots were sampled for every single house, pit shelter, or exit trap (Colombian curtain) sample, per interval of sampling.

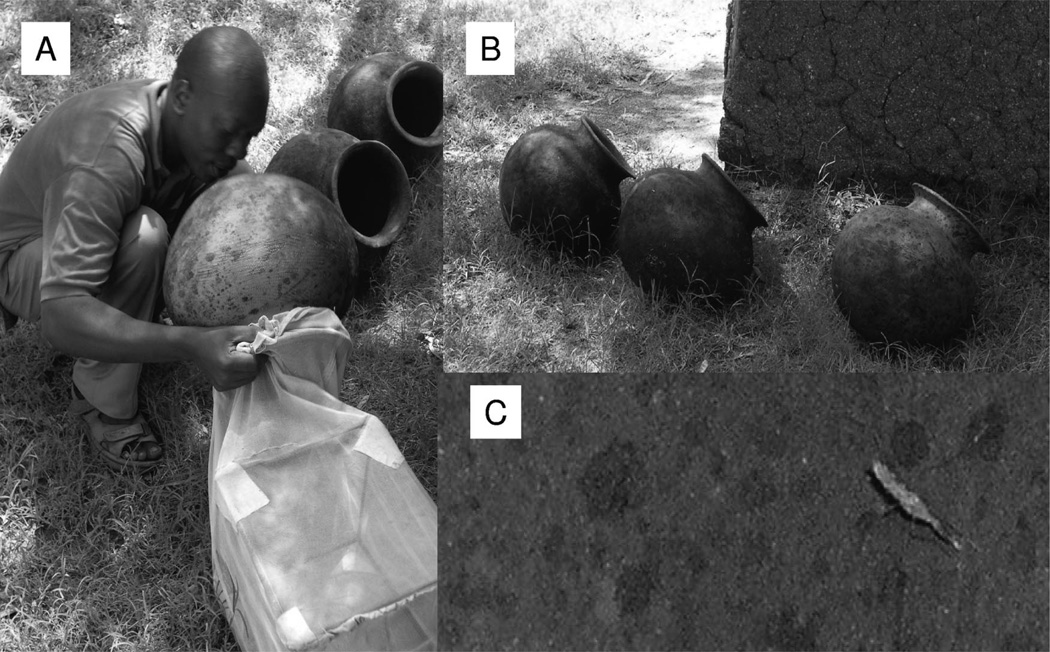

Clay pots are conventionally used for storing drinking water in the homes in the study area, and were of local design and manufacture. Each pot was of ≈20 liters capacity, with an opening of 20 cm width, a round bottom, and a maximum width of 45 cm(Fig. 1). We modified them for mosquito sampling as follows. During manufacture, a 2-cm-diameter hole was placed into the center of the base. The hole made the pot useless to hold water, thereby limiting likelihood of theft. Mosquitoes were sampled from the pots as follows (Fig. 1). Cloth mesh from a standard adult mosquito cage was placed over the pot opening and secured. The sampler then lifted the pot to expose the opening to light and agitate mosquitoes inside, and blew into the small hole at the bottom, causing the mosquitoes inside the pot to take flight and enter the cage. The cloth mesh was then removed, and remaining mosquitoes in the pot were recovered with an aspirator and transferred to the cage, completing the collection. Any spider webs and organisms were brushed out of the pot.

Fig. 1.

(A) Manipulation of an AgREPOT to retrieve mosquitoes resting in it. (B) Three AgREPOTS deployed outside a human dwelling at the study site. (C) An. gambiae s.l. female resting in an AgREPOT.

The mosquitoes from each sampling effort were identified as An. gambiae s.l., An. funestus, or Culex spp.; sorted into separate paper cups; and counted by sex. The abdominal condition of each female was scored as either blood fed, unfed, or gravid. A large subsample of An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes were identified to sibling species (An. gambiae s.s. or An. arabiensis) by using a modified method based upon the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedure described in Scott et al. (1993).

To compare mosquito counts of different categories (species and sex) by sampling method and among sampling intervals, a longitudinal regression analysis (Diggle et al. 2002) was carried out, using the generalized estimating equations procedure(GENMOD)in SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute 2000-2004). Data were fit to both the Poisson and negative binomial distributions (Ludwig and Reynolds 1988), and the latter was chosen as the appropriate distribution for the regression. The data used as input were aggregated by compound; thus, a single datum for the regression was the total collections by method from one compound, per sampling interval. The regression included a repeated measures element to account for the same compounds being sampled repeatedly during the study period. Contingency tables were used to test for differences among sampling methods in frequency of physiological states (gravid, blood fed, unfed; parous or nulliparous if unfed) of female mosquitoes, and differences among species by sampling method.

Results

In total, 10,517 mosquitoes were collected during the study period (Table 1): 2,815 by PSC; 2,715 in Colombian curtains; 3,977 from clay pots; and 1,010 from pit shelters. The composition of the sample was 44.4% An. gambiae s.l., 5.9% An. funestus, and 49.7% Culex spp. Although the Culex spp. were not identified to species, the majority were Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Clay pots accounted for 37.8% of all the mosquitoes taken in the study. The number of An. funestus in samples was comparatively lower than An. gambiae s.l. or Culex spp., but males and females of this species were present in samples from all four methods (Table 1). Pots yielded the greatest number of males, and also notably a large number of females in the outdoor setting, although comparatively fewer than PSC and Colombian curtains.

Table 1.

Summary of mosquito collections by four sampling methods in Asembo and Seme, rural western Kenya, April–July 2005

|

An. gambiae s.l. |

An. funestus |

Culex spp. Total |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | ||

| PSC | 678 | 832 | 1,510 | 83 | 145 | 228 | 1,077 |

| Pot | 1,293 | 704 | 1,997 | 142 | 87 | 229 | 1,751 |

| Pit | 147 | 194 | 341 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 633 |

| CC | 204 | 616 | 820 | 20 | 104 | 124 | 1,771 |

| Total | 2,322 | 2,346 | 4,668 | 257 | 360 | 617 | 5,232 |

CC, Colombian curtain; Pit, pit shelter; Pot, clay pot; and PSC, pyrethrum spray catch.

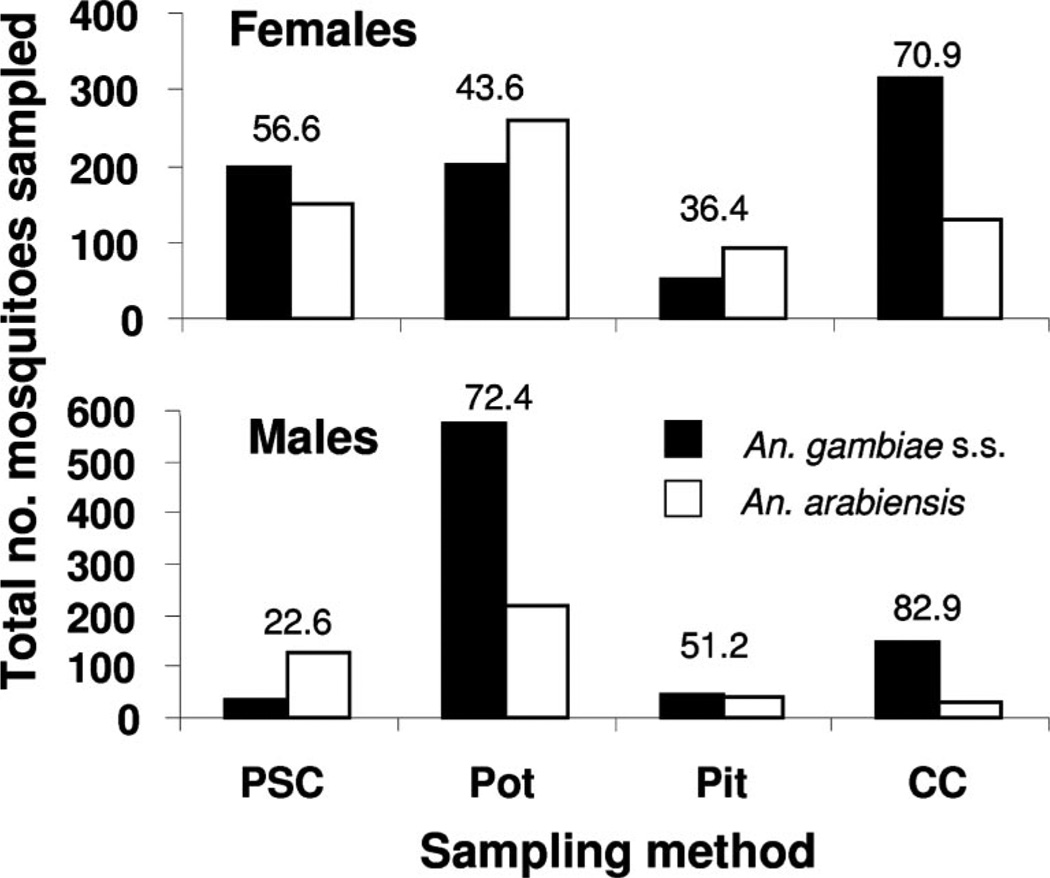

Of 3,012 An. gambiae s.l. analyzed by PCR for determination of species (65.5% of the total An. gambiae s.l. in the sample), there were 2,621 successful amplifications and 391 undetermined specimens (a PCR success rate of 87.02%). Of those successful reactions, there were 1,223 males (of which 65.7% were determined by PCR to be An. gambiae s.s., the remainder being An. arabiensis) and 1,398 females (of which 54.8% were determined to be An. gambiae s.s., the remainder being An. arabiensis) (Fig. 2). Both sibling species were taken by all four methods, but notably An. gambiae s.s. routinely occurred in pots (placed outdoors), and the only other outdoor sampling method used here (pits) yielded comparatively far fewer. Additionally, large numbers of males (particularly An. gambiae s.s. but also An. arabiensis) were collected in pots, compared with the other methods. There was a highly significant difference in number of An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis females recovered from the four sampling methods (2 by 4 contingency table: χ2 = 7.3, P = 0.006). Percentage of deviation from expectation showed that An. gambiae s.s. females were (comparatively) overrepresented in Colombian curtain samples, whereas An. arabiensis females were overrepresented in pot and resting pit samples. There was a highly significant difference in number of An. gambiae s.s. and An arabiensis males recovered from the four sampling methods as well (2 by 4 contingency table: χ2 = 114.1, P <0.0001). Percentage of deviation from expectation showed that An gambiae s.s. males were underrepresented in PSC and pit sampled compared with An. arabiensis, whereas An. gambiae s.s. males were overrepresented in pots and Colombian curtains compared with An. arabiensis males.

Fig. 2.

Total number of An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis males and females taken by four sampling methods in western Kenya. The number over each pair of bars is the percentage that were An. gambiae s.s. Pot, clay pot (AgREPOT); PSC, pyrethrum spray catch; CC, Colombian curtain; and Pit, resting pit.

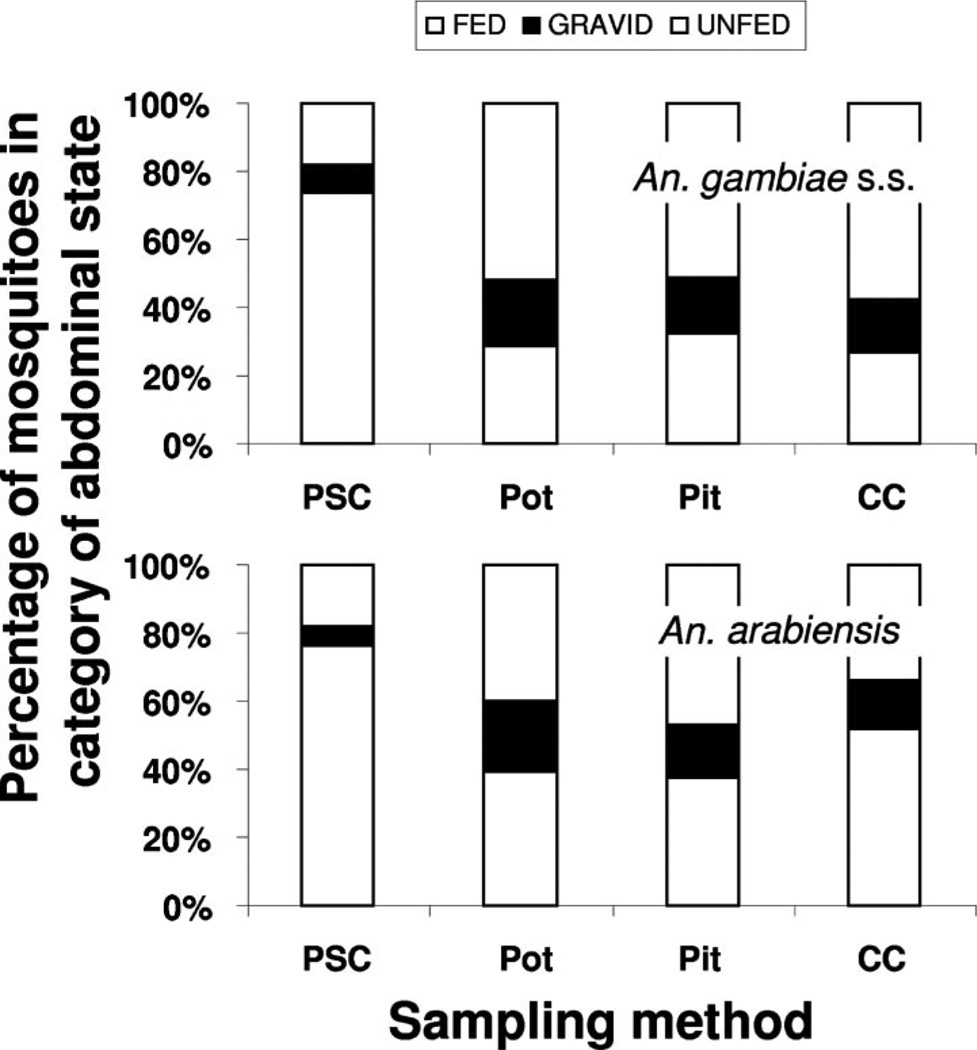

Recovery of females of An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis of different abdominal states (blood fed, gravid, or unfed) varied among sampling methods (Fig. 3). The PSC method yielded a greater proportion of blood-fed mosquitoes, and relatively fewer gravid and unfed individuals, compared with the other three sampling methods where there were more even proportions of blood-fed and unfed individuals but a larger proportion of gravid individuals compared with the PSC method. For An. gambiae s.s., there was a highly significant effect of sampling method on frequency of sampling mosquitoes in the three abdominal states (3 by 4 contingency table:χ2 = 12.3, P = 0.0005). Percentage of deviation from expectation showed that blood-fed individuals were comparatively overrepresented in PSC samples, whereas gravids and unfeds were overrepresented in Colombian curtain samples, and gravids were overrepresented in clay pot samples. For An. arabiensis, there was a highly significant effect of sampling method on frequency of mosquitoes in the three abdominal states (3 by 4 contingency table:χ2 = 13.3, P = 0.0003). Percentage of deviation from expectation showed that blood-fed individuals were comparatively overrepresented in PSC samples, whereas gravids and unfeds were overrepresented in clay pot samples, and gravids were overrepresented in pit shelters.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis females in three physiological categories (blood fed, gravid, or unfed) taken by four sampling methods in western Kenya. Pot, clay pot (AgREPOT); PSC, pyrethrum spray catch; CC, Colombian curtain; and Pit, resting pit.

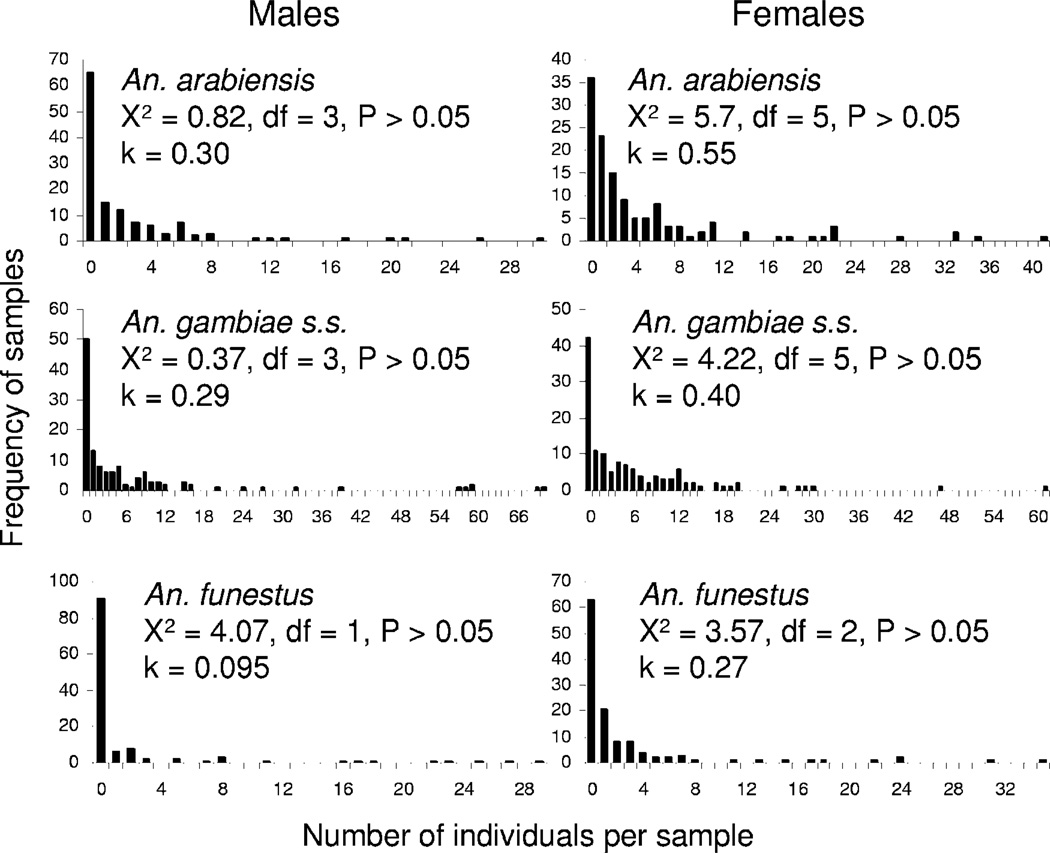

Data of frequency of occurrence of individuals of different sexes and species of Anopheles were fit to the Poisson and negative binomial distributions, for all sampling methods combined (Fig. 4). Results showed close fits to the negative binomial distribution in all six cases, with estimates of the dispersion parameter, k, ranging from 0.29 to 0.55, indicative of highly aggregated distributions (Ludwig and Reynolds 1988). In all instances, fits of the same frequency distributions to the Poisson distribution were very poor by comparison, with the probability that the frequency distributions were described by the Poisson being P <0.001 in all cases (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Frequency histograms of distribution of mosquitoes sampled by different methods in villages of western Kenya. Fits to the negative binomial distribution, and estimations of the dispersion parameter, k, are shown.

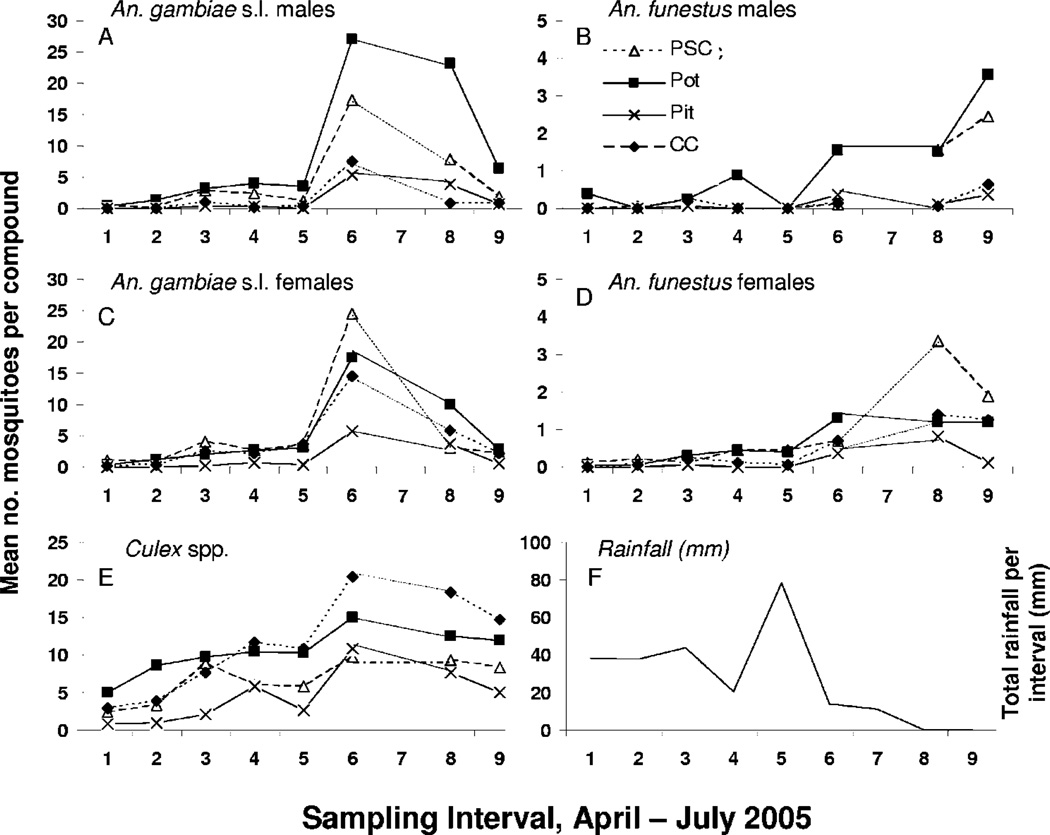

Comparison of sampling methods among the nine sampling intervals showed that populations of adult male and female An. gambiae s.l. were initially low, rose abruptly to a peak by weekly sampling interval 6, and then declined by weekly sampling interval 9 in July (Fig. 5, A and B). By contrast, populations of An. funestus gradually rose throughout the study period (Fig. 5, C and D), as did Culex spp. populations (Fig. 5E). These patterns may reflect cumulative rainfall during the study period (Fig. 5F). Results of longitudinal regression (Table 2) indicated that the clay pot method recovered greater numbers of adult male and female An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis than did pit shelters, which overall as a sampling method performed poorly, and was equivalent to or better in sampling these groups than the pyrethrum spray catch method (see parameter estimates in Table 2). The Colombian curtain method returned slightly more An. gambiae females than did clay pots; otherwise, this method and clay pots were equivalent (An. funestus females) or clay pots performed better (An. gambiae s.s. males; An. arabiensis males and females). For all groups, there was significant variation among weeks of sampling, indicating that all four methods adequately captured temporal variation in abundance of both sexes of these mosquito species. It was not possible to conduct the longitudinal regression analysis for An. funestus males, because there were too few individuals in the sample.

Fig. 5.

Mean number of mosquitoes taken in four different sampling methods per compound, in biweekly sampling intervals from April to July 2005, in rural western Kenya. A-E are species and sexes as indicated, with E as Culex spp. males and females combined. F is total rainfall (millimeters) per day at the study site. Pot, clay pot (AgREPOT); PSC, pyrethrum spray catch; CC, Colombian curtain; and Pit, resting pit.

Table 2.

Results of regression using generalized estimating equations of mosquito collections by four sampling methods among nine biweekly sampling intervals of sampling in Asembo and Seme, rural western Kenya, April–July 2005

| Species and sex | Wald statistica | Parameter estimateb |

Lower confidence limit |

Upper confidence limit |

Z scorec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling method or intervala | |||||

| An. gambiae s.s. males | |||||

| Sampling method | 229.1*** | ||||

| Colombian curtain | −1.62 | −1.98 | −1.26 | −8.89*** | |

| Pit shelter | −2.92 | −3.42 | −2.43 | −11.64*** | |

| Pyrethrum spray collection | −1.14 | −1.48 | −0.8 | −6.57*** | |

| Clay pot | |||||

| Sampling interval | 826.7*** | ||||

| An. gambiae s.s. females | |||||

| Sampling method | 60.8*** | ||||

| Colombian curtain | 0.34 | −0.07 | 0.75 | 1.62ns | |

| Pit shelter | −1.62 | −2.12 | −1.12 | −6.35*** | |

| Pyrethrum spray collection | 0.21 | −0.30 | 0.72 | 0.82ns | |

| Clay pot | |||||

| Sampling interval | 238.7*** | ||||

| An. arabiensis males | |||||

| Sampling method | 158.6*** | ||||

| Colombian curtain | −2.25 | −2.72 | −1.78 | −9.38*** | |

| Pit shelter | −2.05 | −2.66 | −1.43 | −6.54*** | |

| Pyrethrum spray collection | −1.77 | −2.22 | −1.31 | −7.58*** | |

| Clay pot | |||||

| Sampling interval | 74.7*** | ||||

| An. arabiensis females | |||||

| Sampling method | 40.5*** | ||||

| Colombian curtain | −0.83 | −1.29 | −0.38 | −3.61*** | |

| Pit shelter | −1.47 | −2.10 | −0.84 | −4.57*** | |

| Pyrethrum spray collection | −0.26 | −0.84 | 0.32 | −0.87ns | |

| Clay pot | |||||

| Sampling interval | 151.6*** | ||||

| An. funestus females | |||||

| Sampling method | 75.98*** | ||||

| Colombian curtain | −0.5 | −1.01 | 0.01 | −1.62ns | |

| Pit shelter | −1.65 | −2.17 | −1.13 | −6.20*** | |

| Pyrethrum spray collection | 0.22 | −0.38 | 0.82 | 0.72ns | |

| Clay pot | |||||

| Sampling interval | 122.1*** | ||||

| Culex spp. males and females | |||||

| Sampling method | 47.8*** | ||||

| Colombian curtain | −0.08 | −0.52 | 0.37 | −0.34ns | |

| Pit shelter | −1.08 | −1.57 | −0.59 | −4.31*** | |

| Pyrethrum spray collection | −0.51 | −0.86 | −0.17 | −2.93*** | |

| Clay pot | |||||

| Sampling interval | 35.31*** |

Analysis for An. funestus males was not done due to small sample.

The Wald statistic tests for the significance of the main effects; here sampling method (df = 3) and sampling interval (df = 7).

If the Wald statistic was significant for sampling method, then comparisons of individual sampling methods was done such that the clay pot method was the reference against which the three other methods were tested. Accordingly, there were no statistical outputs including parameter estimates for clay pots. Interpretation of parameter estimates is as follows: if the parameters are negative and carry a statistically significant Z score, then the sampling method yielded fewer mosquitoes than did clay pot. Conversely, if the parameter is not significant, then there is no difference in yield of mosquitoes between that sampling method and clay pot. If the parameter value is positive and significant, then the sampling method yielded more mosquitoes than did the clay pot method. Odds ratio parameters are not shown for sampling intervals.

ns, not significant;

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001; and

P < 0.0001.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the usefulness of clay pots (AgREPOTs) in sampling outdoor resting An. gambiae, An. arabiensis, An. funestus, and Culex spp. of both sexes in rural western Kenya. The clay pots performed better than pit shelters, the only well-known sampling method specifically aimed to recover outdoor, resting An. gambiae mosquitoes; and they were generally equivalent to Colombian curtain exit traps and indoor pyrethrum spray samples in return of numbers of mosquitoes. Of the 60 clay pots used, only one was broken during the sampling period (it was immediately replaced), and there were no pots lost to theft, indicating that this method could be used reliably in communities without interference. Besides durability, clay pots are a low-cost, noninsecticidal, portable device for sampling the outdoor fraction of An. gambiae s.l. We found that twice weekly sampling of three pots in a compound (i.e., six pots per week) was roughly equivalent to one indoor, pyrethrum spray catch per week in numbers of mosquitoes, with some variations in recovery of these two methods depending upon the sex and species of mosquito (Tables 1 and 2). The PSC method is laborious and requires hauling insecticide, spray equipment, and drop cloths from house to house over a short period of time in the morning, before mosquitoes exit the house; these logistical matters along with disruption of the lives of the people living in houses are real limitations in application of this method. Similarly, the Colombian curtain method requires installation of a large, cumbersome curtain onto a house, also a logistical burden. The other outdoor sampling method, the pit shelter, requires digging a deep pit which can gather water and provide a hazard for children and livestock wandering in the area. Clay pots have none of these problems. Our data suggest that clay pots, if properly distributed and in adequate number, can be used as surrogates for the pyrethrum spray catch as a standard sampling tool for nonhost-seeking An. gambiae s.s., An. arabiensis, An. funestus, and Culex spp.

One disadvantage of clay pots is that besides mosquitoes, they also provided resting places for other animals such as lizards, spiders, and scorpions, some of which are potential mosquito predators. There were no snakes found in the pots. Conversely, these predators are also found in houses and in pit shelters, so one would not necessarily expect predation pressure to be any higher in an AgREPOT than in a pit or inside a house. We found that brushing the inside of the pots after regular sampling tended to reduce the numbers of spiders and their webs, but its effect was not quantified.

Of significance was that both male and female Anopheles gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis were found in the AgREPOTS as were all three major physiological stages (unfed, blood fed, and gravid) of females. However, the four sampling methods used here reveal that the oft-used description of An. gambiae s.s. as an endophilic species and An. arabiensis as an exophilic one seems not to hold well with our results; there was no strong trend in this regard, with males of An gambiae s.s. being the most numerous in pots and An. arabiensis males more numerous in indoor PSC collections (Fig. 2). Females of both species were found indoors and outdoors, and in house exit traps as well, with only minor (but statistically significant) differences in the proportions of species represented in these samples. The endophily/exophily dichotomy for these two closely related species could very well be a consequence of the lack of good sampling methods for outdoor resting mosquitoes, which adequately sampling as shown here reveals indoor and outdoor subpopulations of sexes of both species, and mobile populations as shown by the Colombian curtain samples. Thus, clay pots placed outdoors offer a relatively bias free sampling method, compared with house-associated methods where the exophily/endophily phenotype becomes an issue of interpretation. Petrarca et al. (1991) suggested that populations of western Kenyan An. gambiae s.s. showed post-bloodmeal exophily, whereas An. arabiensis exhibited post-bloodmeal endophily, phenomena that could explain the distribution of females of these two species in our findings, in part. However, Githeko et al. (1993) inferred from bloodmeal identification data that An. arabiensis females living in this same area did not show exophilic behavior after blood feeding indoors, even in the absence of indoor residual spraying of insecticides, suggesting that females will partition into indoor and outdoor populations solely on the basis of where blood hosts are encountered and not by any genetically determined factor. By contrast, Mnzava et al. (1994) observed that populations of An. arabiensis in the Baringo district of Kenya were polymorphic with regard to indoor and outdoor resting behavior, with only about one-third of individuals that fed outdoors then seeking an indoor resting site. Githeko et al. (1996) reported a higher proportion of An. arabiensis resting in outdoor structures in Kisumu, compared with An. gambiae s.s., a trend that is only mildly supported by our data, given that some 44% of the female An. gambiae s.l. found in the pots outdoors were An. gambiae s.s. (Fig. 2), whereas the preponderance of males in pots were An. gambiae s.s.

Our finding of a higher proportion of unfed and gravid individuals compared with blood-fed individuals in pots suggests that physiological state of females affects resting site choice both indoors and outdoors, introducing another source of sampling bias. Possibly, clay pots could be deployed indoors (as were resting baskets described by Harbison et al. 2006) and simultaneously outdoors to provide even coverage of the same sampling device in indoor and outdoor environments for purposes of comparisons without bias due to sampling method.

The temporal changes in abundance of An. gambiae s.l. and An. funestus revealed patterns common to sampling method, indicating that the clay pots sampled the populations with sensitivity similar to or better than that of the other methods. This observation verifies the clay pot method, the novel sampling method studied here, with the other three more standard methods. Also, this trend indicates that pots would be useful as sampling devices when changes in density of An. gambiae, An. arabiensis, and An. funestus must be measured reliably to assess effects of an intervention, such as indoor residual spraying or deployment of insecticide-treated bed-nets, where standardization is important (WHO 1975), or when data for modeling vector populations in simulations of malaria transmission are required.

The close fit of the sampling series of all mosquito species and sexes to the negative binomial indicates that individuals in the populations under study were aggregated and not randomly dispersed in the study area. This finding is consistent with adult mosquito populations in general (Service 1993) and the value k, the dispersion parameter in the negative binomial distribution, is useful in making estimates of sample sizes required for purposes of precision and statistical estimation (Ludwig and Reynolds 1988, Service 1993).

Acknowledgments

We thank Laban Adero for assisting with fieldwork and George Olang’ for logistical support. We are grateful to Maurice Ombok for mapping the study area; Samson Otieno for sorting field samples; and Joseph Nduati, Erick Ochomo, Ben Oloo, Blair Bullard, and Alisha Thibault for PCR identification of An. gambiae s.l.Wethank the residents of Asembo and Seme, in particular the people of Akado market center, for cooperation throughout the study. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI50703 and U01 AI058542. This paper is published with the permission of the director of the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

References Cited

- Beier JC, Perkins PV, Onyango FK, Gargan TP, Oster CN, Whitmire RE, Koech DK, Roberts CR. Characterization of malaria transmission by Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae) in western Kenya in preparation for malaria vaccine trials. J. Med. Entomol. 1990;27:570–577. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/27.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloland PB, Boriga DA, Ruebush TK, McCormick JB, Roberts JM, Oloo AJ, Hawley W, Lal A, Nahlen B, Campbell CC. Longitudinal cohort study of the epidemiology of malaria infections and disease transmission. II. Descriptive epidemiology of malaria infection and disease among children. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999;60:641–648. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JL, Pradhan GD, Joshi GP, Fontaine RE. Assessment of the grain store as an unbaited outdoor shelter for mosquitoes of the Anopheles gambiae complex and Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) at Kisumu, Kenya. J. Med. Entomol. 1980;17:100–102. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gimnig JE, Vulule JM, Lo TQ, Kamau L, Kolczak MS, Phillips-Howard PA, Mathenge EM, ter Kuile FO, Nahlen BL, Hightower AW, et al. Impact of permethrin-treated bed nets on entomologic indices in an area of intense year-round malaria transmission. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003;68(Suppl):16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Githeko AK, Service MW, Mbogo CM, Atieli FK, Juma FO. Origin of blood meals in indoor and outdoor resting malaria vectors in western Kenya. Acta Trop. 1993;58:307–316. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Githeko AK, Service MW, Mbogo CM, Atieli FK. Resting behaviour, ecology and genetics of malaria vectors in large scale agricultural areas of western Kenya. Parassitologia. 1996;38:481–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison JE, Methenge EM, Misiani GO, Mukabana WR, Day JF. A simple method for sampling indoor resting mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Africa. J. Med. Entomol. 2006;43:473–479. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[473:asmfsi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komar N, Pollack RJ, Spielman A. A nestable fiber pot for sampling resting mosquitoes. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1995;11:463–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig JA, Reynolds JF. Statistical ecology: a primer on methods and computing. New York: Wiley; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mathenge EM, Gimnig JE, Kolczak M, Ombok M, Irungu LW, Hawley WA. Effect of permethrin-impregnated nets on exiting behavior, blood feeding success, and time of feeding of malaria mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in western Kenya. J. Med. Entomol. 2001;38:531–536. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RP. The “walk-in” type red box for sampling adult mosquitoes. Proc. N.J. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1985;72:104–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mnzava AEP, Mutinga MJ, Staak C. Host blood meals and chromosomal inversion polymorphism in Anopheles arabiensis in the Baringo District of Kenya. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1994;10:507–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CD. A structural and operational analysis of diurnal resting shelters for mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) J. Med. Entomol. 1981;18:419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Mutero CM, Mosha FW, Subra R. Biting activity and resting behavior of Anopheles merus Donitz (Diptera: Culicidae) on the Kenya Coast. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1984;78:43–47. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1984.11811771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrarca V, Beier JC, Onyango F, Koros J, Asiago C, Koech DK, Roberts CR. Species composition of the Anopheles gambiae complex (Diptera: Culicidae) at two sites in Western Kenya. J. Med. Entomol. 1991;28:307–313. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/28.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS 9.1.3. Help and documentation. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2000–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scott JA, Brogdon WA, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993;49:520–529. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Service MW. Mosquito ecology: field sampling methods. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Observations on the man-biting habits of some mosquitoes in the South Pare area of Tanganyika. East Afr. Med. J. 1961;38:246–255. [Google Scholar]

- [WHO] World Health Organization. Vector bionomics and related aspects. No. 13. Geneva, Switzerland: 1975. Manual on practical Entomology in Malaria. Part I. [Google Scholar]