Abstract

Anaphylaxis is traditionally recognized as a rapidly developing combination of symptoms often including hives and hypotension or respiratory symptoms. Furthermore, when a specific cause is identified, exposure to this cause is usually noted to have occurred within minutes to 2 hours before the onset of symptoms. This case is of a 79 year-old female who developed a severe episode of anaphylaxis 3 hours after eating pork. Prior to 2012, she had not experienced any symptoms after ingestion of meat products. Delayed anaphylaxis to mammalian meat has many contrasting features to immediate food-induced anaphylaxis. The relevant IgE antibody is specific for the oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal), a blood group substance of non-primate mammals. Evidence from Australia, Sweden, and the U.S. demonstrates that the primary cause of this IgE antibody response is tick bites. These bites characteristically itch for ten days or more. Diagnosis can be made by the presence of specific IgE to beef, pork, lamb, and milk and lack of IgE to chicken, turkey, and fish. Prick skin tests (but not intradermal tests) are generally negative. Management of these cases, now common across the southeastern U.S., consists of education combined with avoidance of both red meat and further tick bites.

Keywords: Anaphylaxis; delayed reaction to red meat; galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose

Introduction/Background

Anaphylaxis is a well-recognized syndrome that can occur rapidly after exposure to allergens derived from foods, venoms, and medications as well as during allergen immunotherapy. There are several potential features that characterize anaphylaxis, which, in most cases, make both the diagnosis and the cause obvious. Firstly, the combination of hives (or angioedema), hypotension and respiratory symptoms is familiar to medical personnel who work in an emergency setting. Secondly, the onset of symptoms generally occurs within minutes to 2 hours after the exposure, thus limiting the range of events that need to be considered as causal. Thirdly, most of the cases have some prior history of allergic symptoms or local reactions to the causal agent. Finally, onset of sensitivity to foods other than fish, shellfish, and tree nuts is considered to be rare after childhood. The present case has many features which do not fit the traditional model but are representative of a syndrome that is both common in the United States and increasingly recognized in other parts of the world. Prior to the recognition of the specific IgE antibody involved, the etiology of these cases was not only regarded to be unrelated to food allergy, but was also consistently dismissed as being idiopathic or even psychological in nature.

Case

On June 3rd, 2012 at 3:00 PM, Mrs. I.C., age 79, collapsed in the lobby of the University of Virginia hospital shortly after she had developed generalized itching and hives. She was found to have a blood pressure of 60/45 and the hospital emergency team treated her with epinephrine, Benadryl, IV Solumedrol and IV fluids before transfer to the Emergency Department (E.D.) and subsequently to the hospital. She had no respiratory symptoms. She recovered steadily over the next few hours, but developed an unusual flat, erythematous rash on her arms that was present for 12 hours (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Physical Exam of Ms. I.C. 8 hours after ingestion of pork and five hours after anaphylaxis.

History

She had been working in the hospital for over 40 years and had a longstanding history of medical issues including hypertension, for which she was taking low doses of metoprolol and lisinopril. In addition, she reported a history of enduring two episodes of hives earlier that summer after eating beef several hours preceding the episodes and had not been aware of any insect stings on the days of the episodes. After learning of the syndrome of “red meat allergy” from the local papers, she began avoiding ingestion of red meat with the thought that her reactions may be related to this reported allergy. On the day of the reaction, she chose to eat pork for lunch, with the thought that pork was not red meat, but rather “the other white meat”. Upon further questioning during follow-up, she reported having had three tick bites earlier in the summer that had itched for about ten days.

Investigation

Routine lab studies, including metabolic panel and CBC with differential, were unremarkable except for a low eosinophil count. Serum total IgE was 223 IU/ml and IgE to galactose alpha-1, 3-galactose was 82.7 IU/ml (Table 1). Her serum tryptase level 12 hours after the episode was 36.5 ng/mL (normal range < 11.5).

Table 1.

Lab values of Ms. I.C. from June 2012 to December 2013

| Specific IgE (IU/mL) | June 2012 | August 2012 | September 2012 | December 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-gal | 82.3 | 47.5 | 35.7 | 18.9 |

| Beef | - | 4.32 | 4.80 | 2.61 |

| Pork | - | 2.2 | 2.20 | 2.71 |

| Lamb | - | - | - | 1.15 |

| Chicken | - | <0.1 | - | <0.1 |

| Fish | - | <0.1 | - | <0.1 |

| D. pteronyssinus | - | <0.1 | - | <0.1 |

| Cat | - | 0.45 | - | 0.52 |

| Grass pollen | - | 1.10 | - | <0.1 |

| Total IgE (IU/mL) | 180 | 111 | 85.8 | 50.6 |

| Tryptase (ng/mL) | 36.5 | - | 7.53 | - |

Discharge instructions

She was educated in detail about the diagnosis. The management recommended to her at the time of discharge was avoidance of ingestion of mammalian meat and avoidance of environments with a high prevalence of ticks. She was given a prescription for an Epipen.

Differential diagnosis and possible causes

The possible causes of collapse in general are numerous and include common cardiopulmonary, endocrine, and gastrointestinal emergencies. Included in this list is anaphylaxis, which is easily recognized by the combination of generalized pruritus, hives, and hypotension, and which was confirmed in this case with an elevated serum tryptase level (1, 2). Over the last twenty or more years, we have either seen or helped to investigate patients in whom anaphylaxis was caused by a wide range of events which, in most cases, was combined with sensitization (Table 2). These include venoms, foods, medications, monoclonal antibodies, and NSAIDs, as well as less common events such as Trichophyton sensitization, bites from laboratory rodents, and wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis (3–6).

Table 2.

Causes of anaphylaxis in patients seen by or investigated by the authors

| Immediate responses | |

| i) Venom | Honey bee, hornet, yellow jacket and fire ant |

| ii) Foods | Peanut, tree nut, egg, milk, and shellfish Pork (in pork cat syndrome) |

| iii) Medications, Vaccinations | Penicillins, other antibiotics Cetuximab, infliximab Aspirin, NSAIDs* Zostavax** |

| iv) Bites from laboratory animals | Rat |

| Delayed or ill-defined time course | |

| i) Trichophyton infection and sensitization | |

| ii) Thyroid autoantibodies: very high titer* | |

| iii) Food-related exercise-induced anaphylaxis | |

| iv) Delayed reactions to mammalian meat in patients with IgE to alpha-gal | |

Not related to specific IgE

Related to specific IgE to gelatin, not to alpha-gal

Over the last 5 years, we have evaluated hundreds of patients with a history of anaphylaxis, angioedema or generalized urticaria starting 3–5 hours after eating “red meat”. As in the case of Mrs. I.C., these patients have serum IgE antibodies to galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose (alpha-gal) (7). This oligosaccharide, a blood group substance of non-primate mammals, is present on glycolipids and glycoproteins in beef, pork, lamb, and in the meat and organs of a wide range of mammals (8–10). The latter include horse, goat, rabbit, and squirrel as well as mammalian heart, liver, stomach and kidney. Strikingly, many of the patients correctly identify that their reactions occur after the ingestion of beef or pork, but not after ingestion of chicken, turkey, or fish. The cat-pork syndrome can cause confusion because patients with this syndrome, whose primary sensitization is to cat albumin, can become allergic to pork in adulthood due to cross-reactivity between cat albumin and pork albumin (11,12). However, the reactions are more rapid, i.e. within one hour, and generally occur only after ingestion of pork.

History of IgE antibodies to Alpha-Gal and Cetuximab-induced Hypersensitivity Reactions

In 1935, Karl Landsteiner identified a blood group “B-like” oligosaccharide on non-primate red blood cells and reported that all humans had antibodies to this antigen (13). Subsequently, it became clear that this antigen, galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose, was a major transplantation barrier between primates and other mammals (9,10). The fact that mice can make oligosaccharides that are foreign to humans is highly relevant to our story. In 2004, the monoclonal antibody, cetuximab, was being studied in clinical trials and it became clear that it was causing hypersensitivity reactions in some southern states. Dr. Tina Hatley in our group carried out preliminary experiments on IgE to this molecule. However, marketing of the mAb was delayed, and it was not until 2006 that the severity of the reactions became obvious (14). At this time, Dr. Hatley, who was working in Bentonville, AK, convinced us to develop a new version of the IgE assay (fluorometric enzyme immunoassay or CAP) using the streptavidin technique, in which streptavidin is coupled to the solid phase of the CAP to provide a matrix for the binding of biotinylated novel or purified allergens (15). We were asked to investigate the reactions to cetuximab, in part because we had already developed the assay for IgE to cetuximab. In collaboration with Dr. Chung from Nashville, Dr. Mirakhur from Bristol Myers Squibb, and Dr. Hicklin from ImClone, we demonstrated that the patients who had reactions to cetuximab also had IgE antibodies specific for this molecule before they started treatment (3). We went on to demonstrate that the IgE antibodies were specific for the oligosaccharide on the Fab portion of the mAb. From the known glycosylation of the molecule, we identified alpha-gal as the relevant epitope (16). Initially, we argued that the glycosylation on the Fc portion of the molecule was not alpha-gal, however, further investigation established that the glycosylation of the Fc is “encased” within the two halves of the molecule (17).

Delayed Anaphylaxis to Red Meat

Following the discovery that IgE antibodies to alpha-gal were common in our area, we asked whether there were other allergic diseases associated with this antibody. Through testing different groups of patients in our clinics for IgE to alpha-gal, we identified a group of patients who had episodes of generalized urticaria, angioedema or recurrent anaphylaxis. These patients had no obvious immediate cause for their episodes, but in several cases the patients had reported that they thought the reactions might relate to consumption of meat 3–5 hours earlier. Prick tests with commercial extracts of beef, pork or lamb, produced small wheals, i.e. 2–4 mm in diameter. Wheals of this size would, in general, be interpreted as negative. Intradermal skin tests with commercial meat extracts or prick skin tests with fresh meat extracts demonstrated clearly positive results (7). Furthermore, blood tests for specific IgE Ab to red meats were consistently positive (3, 7). Over the next two years, we rapidly accumulated cases, in large part because of publicity in the press (e.g. Washington Post, October 20, 2009). In fact, it became clear that many patients and two allergists had reported delayed anaphylaxis to red meat in previous years. The best description had come to us from Mrs. Sandra Latimer in Athens, Georgia. In 1989, she described ten cases of delayed reactions to mammalian meat and made a connection with occurrence of tick bites several weeks or months before the first episode of hives or anaphylaxis. Her allergist, Dr. Antony Deutsch, reported her findings to the Georgia Allergy Society and to the CDC in 1991. However, no further reports or statements were issued by either of these organizations possibly because the story seemed so unlikely or because of the lack of a blood test at that time.

While there are several distinctive features of the syndrome including GI symptoms, the most important feature is that patients do not develop any symptoms for at least 2 hours after eating red meat. In most cases, the symptoms are delayed for 3–5 hours, but nonetheless the symptoms can be severe or even life threatening at that time. Secondly, all these patients report meat consumption for many years prior to the onset of the syndrome-- and indeed many of the patients were over 60 years old. Thirdly, while some cases had a history of allergy, most of the cases had no previous allergic symptoms. Finally, we have carried out extensive investigation of lung function and asthma symptoms in these patients and the presence of IgE Ab to alpha-gal shows no association with asthma (18). Although most of the cases occur in adults, a very similar syndrome also can occur in children as young as 5 years old (19).

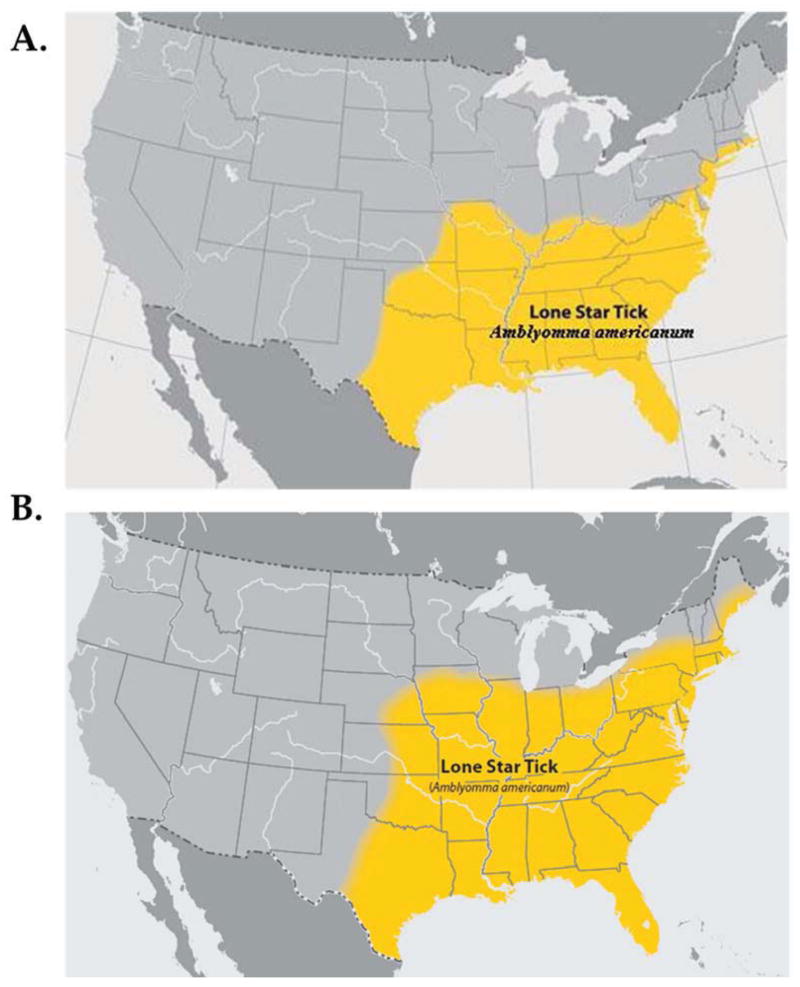

The relevance of tick bites to IgE antibody responses to alpha-gal

In 2008, the specificity of the IgE antibodies that caused reactions to cetuximab became known and it was also clear that reports of delayed reactions to red meat were occurring in the same region as the states in which cetuximab reactions were common. However, it was not clear why these cases were geographically localized. The first clue came from the simple observation that this region was similar to the region of maximum prevalence of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (20). Following this connection, we started to ask questions about tick bites and rapidly became aware that most of the patients with delayed anaphylaxis had experienced bites from adult or larval ticks. The larval ticks, which are approximately 1 mm in diameter, cannot be identified as ticks without a magnifying glass and are commonly referred to as seed ticks or chiggers. The evidence that tick bites caused development of specific IgE to alpha-gal included: consistent histories of bites that itched for two weeks or more; a significant correlation between IgE Ab to alpha-gal and IgE to Lone Star tick; and prospective data on the increase in IgE to alpha-gal following known Lone Star tick bites (20). In addition, there are accurate CDC maps of the distribution of the tick Amblyomma americanum (Figure 2). In other countries, the ticks giving rise to this response are not the same species (Table 3). In Europe, Ixodes ricinus was implicated while in Australia the relevant tick is Ixodes holocyclus (21–24). In contrast, it appears that Ixodes scapularis which is the main vector of Lyme disease in the USA does not induce IgE to alpha-gal. Even more striking is the fact that the bites of I. scapularis that are associated with transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi are not associated with itching (25).

Figure 2. Geographical spread of the Lone Star tick, Amblyomma americanum.

A. 2007. B. 2011. (CDC.gov)

Table 3.

Worldwide Cases of IgE to Galactose-α-1,3-Galactose and Delayed Anaphylaxis to Mammalian Meat

| Country | Ticks | Food | Cases | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sydney, Australia | I. holocyclus | “Roo”, etc. | 400 | Van Noonen et al., Aust J. Med Mullins et al., JACI |

| Nancy, France | [I. ricinus] | Pork kidney and meat from many species | 40+ | Morisset M et al., Allergy, 2012 |

| Stockholm, Sweden | I. ricinus | Red meat | 60+ | Hamsten C et al., JACI, 2013 |

| Japan | ------- | Beef | 30+ | Takahashi H et al., Allergy, 2013 |

| Germany | [I. ricinus] | Pork kidney, etc. | 50+ 40+ |

Biedermann T, JACI in Practice Jappe U, Hautarzt 2012* |

| Virginia, USA | A. americanum | Red meat | 1,800 | Commins SP et al., JACI 2009 Commins SP et al., JACI 2011 |

U Jappe, Alpha-Gal: Neues Epitop, neue Entität

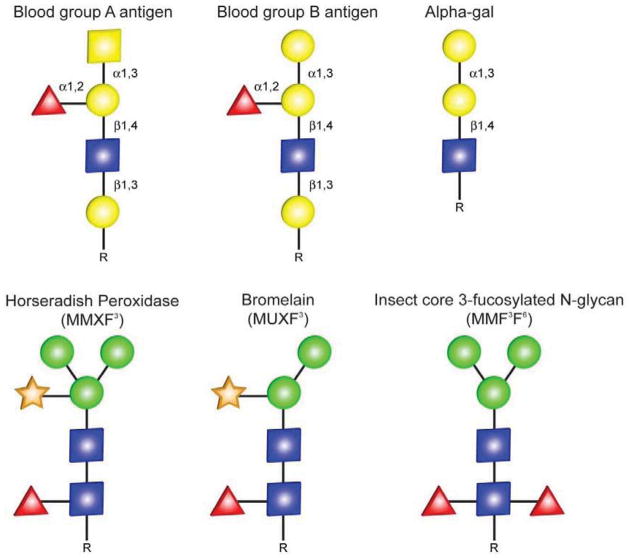

Mechanisms of Anaphylaxis

Our current understanding of the mechanism of sensitization to the oligosaccharide alpha-gal, a blood group substance of non-primate mammals, is that it occurs through bites from several different species of ticks. Thus, the patients have IgE antibodies to this hapten which is present on all mammalian food products. In some ways this is comparable to sensitization to plant oligosaccharides such as MUXF3-- a hapten on the glycoproteins of many plant species (29–31). However, IgE antibodies to such plant-derived cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) are not thought to give rise to symptoms (Figure 3) (29, 32).

Figure 3. Comparison of Mammalian Blood Group-related Oligosaccharides (top) and Plant-derived cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCDs) (bottom).

IgE antibodies to the plant-derived CCDs are not thought to give rise to symptoms. The oligosaccharide structures are shown in the symbolic depiction suggested by the Consortium of Functional Glycomics, and are represented as such: N-acetylglucosamine (blue squares), mannose (green circles), galactose (yellow circles), N-acetylgalactosamine (yellow squares), xylose (orange stars), and fucose (red triangles). (Commins SP and Platts-Mills TAE, Current Perspectives, JACI 2009)

The patients with IgE to alpha-gal consistently report that symptoms start 3–5 hours after eating meat. Furthermore, in challenge studies done with pork, hives and other symptoms do not develop until at least two hours after ingestion (26). By contrast, reactions to cetuximab develop rapidly and symptoms often peak within 20 minutes (3, 14). Similarly, in vitro responses of basophils to glycoproteins such as beef thyroglobulin or cetuximab itself can be detected in 25 minutes. Skin test responses to cetuximab, beef extract, or beef thyroglobulin are all rapid. Thus, there is no reason to think that the delay in response after eating meat reflects a delayed response of basophils or mast cells. The only coherent explanation is that the oligosaccharide is absorbed in some form that enters the circulation slowly. Given that alpha-gal is present on both glycoproteins and glycolipids (including chylomicrons), we think the most likely explanation for the delay in symptoms to be a delay in mediator release triggered by LDL and VLDL-- the metabolic products of chylomicrons which characteristically enter the circulation slowly. Interestingly, during a challenge, circulating basophils, assessed ex vivo, upregulate the expression of CD63 at the same time as the patients develop symptoms (26). On the other hand, a proportion of non-allergic controls also show delayed in-time upregulation of CD63 although they do not experience any symptoms. At present, we think that the likely explanation for this enigmatic finding is that, although VLDL or LDL can cause basophils to upregulate, the quantity of histamine released is not sufficient to cause symptoms. The implication is that LDL particles with alpha-gal on the surface can cause mast cell mediator release, but this only occurs in individuals with IgE Ab to alpha-gal. In keeping with this model, three of the challenge patients, but none of the controls, had tryptase in their circulation after the challenge (26).

Current Management of Delayed Anaphylaxis to Red Meat

At present, the primary management of this syndrome is to avoid red meat, to avoid tick bites, and to educate the patient fully about the management of episodes.

Avoidance of “Red Meat”

This includes avoidance of ingestion of not only beef, pork, and lamb but also horse, goat, rabbit, and squirrel, among others. It is equally important to note that this list also includes organs from mammals such as liver, intestine, heart and kidney; ingestion of pork kidney, a delicacy in Alsace Lorraine and Germany, has been reported to cause more severe and faster (i.e. within 1–2 hours) reactions than ingestion of pork meat (27, 28). Venison may be included in this list if it has been handled by a butcher: in this case it may additionally contain pork fat (however, if this meat is dressed by a hunter it maybe low in fat and tolerated without reaction).

In addition to meat, other mammalian products include lard, suet, gelatin, pork rinds, and dairy products. Most patients with IgE to alpha-gal will have positive IgE assays for milk, but will nonetheless tolerate milk and dairy products. Our current policy is to discuss the relevance of dairy, but only to recommend avoidance in cases who continue to have hives or other unexplained symptoms while avoiding ingestion of red meat. Gelatin has been reported to cause severe reactions either in the form of jelly candy and marshmallows or as the intravenous preparations, Haemaccel and Gelofusine (22, 27).

Avoiding tick bites

Most of us who get repeatedly bitten by ticks “ask for it”. In the case of one of the authors of this manuscript, major episodes have followed long walks in grassy areas during the summer. Equally, many hikers, hunters, gardeners and riding enthusiasts spend time in thick vegetation. While it is possible to put on protective clothing and use products such as DEET, most of the locations in which these bites are occurring are very hot during the summer months. In our area of central Virginia, the larval form of Lone Star ticks are most aggressive and are particularly prevalent in August and early September. Individuals who live in urban settings where ticks are usually less prevalent and those who only hike on well-used trails or fire trails may be able to avoid ticks completely. We have certainly noted a decrease in the level of IgE to alpha-gal in such individuals which may, in turn, make them much less prone to symptomatic attacks.

Management of Episodes

The management of anaphylaxis includes anti-histamines, epinephrine, steroids and IV fluids at all ages. However, there are significant differences in older adults, particularly those who have cardiac risk factors or a history of cardiac disease. Many of the patients with this syndrome are already over 60 years old when they first present with symptoms. In these cases, we tend to recommend less aggressive use of epinephrine. Thus, older patients should be instructed to be careful about exposure; to take Benadryl orally or even intramuscularly; to make sure that someone who is able to administer epinephrine is aware of the symptoms suggestive of a reaction; and to only use epinephrine if the attack progresses beyond hives. One of our colleagues in Lynchburg reported two adult patients who were referred to him by a cardiologist because they had experienced a heart attack shortly after being given epinephrine. The question of when to give epinephrine is primarily one to be decided upon by the patient and first responders, rather than E.D. providers. Most cases arriving in the E.D. do not receive epinephrine because their condition is already improving by the time they arrive in this setting.

Discussion

The syndrome of delayed anaphylaxis to red meat was initially recognized by patients, but for many reasons was not taken seriously by physicians, including allergist-immunologists. The lack of enthusiasm for this syndrome could be easily understood because its features run counter to many established teachings about food allergy and anaphylaxis. These established teachings include: new onset of allergic reactions to meat is rare in adults; intradermal skin tests are not useful in evaluating food allergy; severe, immediate-hypersensitivity reactions to food start within minutes to 2 hours after exposure; and sensitization to food occurs through oral exposure.

There are still many aspects of the syndrome that are not well understood. i) It is not clear why the tick bites induce such high levels of IgE antibody and why the response is specific for this oligosaccharide. It is clear that the tick carries alpha-gal, both from inhibition studies with the extract (20) and from staining sections of the tick (23). However, this is not the only oligosaccharide present on this tick. Currently, we are considering the possibility that the IgE antibody response to alpha-gal involves direct switch outside a germinal center and that the response involves very little somatic hypermutation (33, 34). ii) The basis for the delay in symptoms is not clear. Our hypothesis is that the timing of the reactions reflects the time at which alpha-gal appears in the circulation displayed as repeating epitopes on a particle such as LDL. We are also well aware that some subjects who have IgE to alpha-gal do not experience symptoms. Whether this reflects a difference in carbohydrate absorption or a relative resistance to mast cell mediator release is not clear. iii) The evidence that the prevalence of this syndrome has increased comes from the experience of multiple physicians working in the relevant geographical area.

The present management of this syndrome consists primarily of education combined with specific advice about avoiding ticks and avoiding ingestion of mammalian-derived products. Currently, there are no interventional studies designed to control sensitization or control the reactions. While most allergists in the southeastern U.S. believe that the prevalence of this syndrome has increased, it is difficult to prove that a newly described syndrome was less common previously. In theory, the increase could be due to a change in the tick population such as: the presence of a different species of Rickettsia, the spread of a species of tick that was previously not present, or a simple increase in the population of the Lone Star tick. However, the evidence favors a combination of the increasing geographical range of this tick and the massive increase in number of ticks secondary to the increase in the deer population over the last 60 years (prior to 1950, deer were few in number due to virtual “extirpation” in the piedmont region of Virginia and in the Carolinas). It seems unlikely that we will be able to control the tick population, and, in turn, tick bites, unless the deer population is also controlled. At present, the geographical range of this tick seems to be steadily expanding, and it is likely that the number of cases will continue to increase.

List of Abbreviations

- Alpha-gal

Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose

- E.D

Emergency Department

- CBC

Complete Blood Count

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- Fab

Fragment antigen binding

- Fc

Fragment crystallizable

- Ab

antibody

- DEET

N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wood RA, Camargo CA, Jr, Lieberman P, Sampson HA, Schwartz LB, Zitt M, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: The prevalence and characteristics of anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.016. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman P. Treatment of patients who present after an episode of anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E, Le QT, Berlin J, Morse M, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1109–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Platts-Mills TA, Fiocco GP, Hayden ML, Guerrant JL, Pollart SM, Wilkins SR. Serum IgE antibodies to Trichophyton in patients with urticaria, angioedema, asthma, and rhinitis: development of a radioallergosorbent test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;79:40–5. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(87)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudders SA, Clark S, Wei W, Camargo CA., Jr Longitudinal study of 954 patients with stinging insect anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111:199–204. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hesford JD, Platts-Mills TA, Edlich RF. Anaphylaxis after laboratory rat bite: an occupational hazard. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:765–8. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(95)02016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Commins SP, Satinover SM, Hosen J, Mozena J, Borish L, Lewis BD, et al. Delayed anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria after consumption of red meat in patients with IgE antibodies specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:426–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milland J, Sandrin MS. ABO blood group and related antigens, natural antibodies and transplantation. Tissue Antigens. 2006;68:459–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macher BA, Galili U. The Galalpha1,3Galbeta1,4GlcNAc-R (alpha-Gal) epitope: a carbohydrate of unique evolutionary and clinical relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koike C, Uddin M, Wildman DE, Gray EA, Trucco M, Starzl TE, et al. Functionally important glycosyltransferase gain and loss during catarrhine primate emergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:559–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610012104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilger C, Kohnen M, Grigioni F, Lehners C, Hentges F. Allergic cross-reactions between cat and pig serum albumin. Study at the protein and DNA levels. Allergy. 1997;52:179–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posthumus J, James HR, Lane CJ, Matos LA, Platts-Mills TAE, Commins SP. Initial description of pork-cat syndrome in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:923–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landsteiner K. The specificity of serological reactions. Dover Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Neil BH, Allen R, Spigel DR, Stinchcombe TE, Moore DT, Berlin JD, et al. High incidence of cetuximab-related infusion reactions in Tennessee and North Carolina and the association with atopic history. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3644–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erwin EA, Custis NJ, Satinover SM, Perzanowski MS, Woodfolk JA, Crane J, et al. Quantitative measurement of IgE antibodies to purified allergens using streptavidin linked to a high-capacity solid phase. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1029–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian J, Liu T, Yang L, Daus A, Crowley R, Zhou Q. Structural characterization of N-linked oligosaccharides on monoclonal antibody cetuximab by the combination of orthogonal matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization hybrid quadrupole-quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry and sequential enzymatic digestion. Anal Biochem. 2007;364:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Rispens T, Verploegen S, van der Palen-Merkus T, Stapel S, Workman LJ, et al. Anti-galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose IgE from allergic patients does not bind alpha-galactosylated glycans on intact therapeutic antibody Fc domains. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:574–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Commins SP, Kelly LA, Ronmark E, James HR, Pochan SL, Peters EJ, et al. Galactose-alpha-1,3-Galactose-Specific IgE Is Associated with Anaphylaxis but Not Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:723–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2017OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy JL, Stallings AP, Platts-Mills TA, Oliveira WM, Workman L, James HR, et al. Galactose-a-1,3-galactose and delayed anaphylaxis, angioedema, and urticaria in children. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1545–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Commins S, James H, Kelly E, Pochan S, Workman L, Perzanowski M, et al. The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Nunen SA, O’Connor KS, Clarke LR, Boyle RX, Fernando SL. An association between tick bite reactions and red meat allergy in humans. Med J Aust. 2009;190:510–1. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullins RJ, James H, Platts-Mills TA, Commins S. Relationship between red meat allergy and sensitization to gelatin and galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1334–42. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamsten C, Starkhammar M, Tran TA, Johansson M, Bengtsson U, Ahlen G, et al. Identification of galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose in the gastrointestinal tract of the tick Ixodes ricinus; possible relationship with red meat allergy. Allergy. 2013;68:549–52. doi: 10.1111/all.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamsten C, Tran TAT, Starkhammar M, Brauner A, Commins SP, Platts-Mills TAE, et al. Red meat allergy in Sweden: Association with tick sensitization and B-negative blood groups. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2013;132:1431–4. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burke G, Wikel SK, Spielman A, Telford SR, McKay K, Krause PJ, et al. Hypersensitivity to ticks and Lyme disease risk. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:36–41. doi: 10.3201/eid1101.040303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Commins SP, James HR, Stevens W, Pochan SL, Land MH, King C, Mozzicato S, Platts-Mills TAE. Delayed clinical and ex vivo response to mammalian meat in patients with IgE to alpha-gal. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.024. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caponetto P, Fischer J, Biedermann T. Gelatin-containing sweets can elicit anaphylaxis in a patient with sensitization to galactose-a-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:302–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morisset M, Richard C, Astier C, Jacquenet S, Croizier A, Beaudouin E, et al. Anaphylaxis to pork kidney is related to IgE antibodies specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. Allergy. 2012;67:699–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aalberse RC, van Ree R. Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants. Monogr Allergy. 1996;32:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Ree R, Cabanes-Macheteau M, Akkerdaas J, Milazzo JP, Loutelier-Bourhis C, Rayon C, et al. Beta(1,2)-xylose and alpha(1,3)-fucose residues have a strong contribution in IgE binding to plant glycoallergens. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11451–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mittermann I, Zidarn M, Silar M, Markovic-Housley Z, Aberer W, Korosec P, et al. Recombinant allergen-based IgE testing to distinguish bee and wasp allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1300–7. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mari A. IgE to Cross-Reactive Carbohydrate Determinants: Analysis of the Distribution Appraisal of the in vivo and in vitro Reactivity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;129:286–95. doi: 10.1159/000067591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aalberse RC, Platts-Mills TA. How do we avoid developing allergy: modifications of the TH2 response from a B-cell perspective. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:983–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies JM, Platts-Mills TA, Aalberse RC. The enigma of IgE+ B-cell memory in human subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:972–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]