Abstract

Background: The Multiple Sclerosis Self-Management Scale (MSSM) is currently the only measure that was developed specifically to address self-management among individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS). While good internal consistency (α = 0.85) and construct validity have been demonstrated, other psychometric properties have not been established. This study was undertaken to evaluate the criterion validity, test-retest reliability, and face validity of the MSSM.

Methods: Thirty-one individuals with MS who met the inclusion criteria were recruited to complete a series of questionnaires at two time points. At Time 1, participants completed the MSSM and two generic self-management tools—the Partners in Health (PIH-12) and the Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ)—as well as a short questionnaire to capture participants' opinions about the MSSM. At Time 2, approximately 2 weeks after Time 1, participants completed the MSSM again.

Results: The available MSSM factors showed moderate to high correlations with both PIH-12 and heiQ and were deemed to have satisfactory test-retest reliability. Face validity pointed to areas of the MSSM that need to be revised in future work. As indicated by the participants, some dimensions of MS self-management are missing in the MSSM and some items such as medication are redundant.

Conclusions: This study provides evidence for the reliability and validity of the MSSM; however, further changes are required for both researchers and clinicians to use the tool meaningfully in practice.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a degenerative neurologic condition affecting the central nervous system.1 Because there is no cure for MS, affected individuals live with several incapacitating symptoms for a lifetime that affect their participation and quality of life.2 The unpredictable nature and daily presence of the MS symptoms and their complexity make management of this condition difficult3 and exhausting. It is thus essential for individuals with MS to acquire skills to self-manage the condition in their everyday life.

Audulv and colleagues4 describe self-management as a lifetime negotiation process that requires constant evaluation of self-management efforts and their impacts. This negotiation process is often influenced by internal and external factors, such as experiencing stigma, assessing one's own capabilities, and accessing external support and resources. Effective self-management has been found to be an important avenue for enhancing one's perceived control over the illness and increasing quality of life in the presence of a chronic condition.5,6 Barlow et al.7(p178) define self-management as “the individual's ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition. Efficacious self-management encompasses ability to monitor one's condition and to effect the cognitive, behavioral and emotional responses necessary to maintain a satisfactory quality of life.” As described by Corbin and Strauss,8 self-management includes three tasks: medical or behavioral management, emotional management, and role management. Medical or behavioral management involves activities such as taking medication, adhering to a specific diet, visiting health-care providers, and actively seeking information on one's condition.8 Emotional management refers to coping with emotions that are brought forth by a chronic condition, and role management concerns maintaining current roles and developing new life roles.8

Many self-management tasks are undertaken by individuals with MS to maximize their physical, social, and mental functioning. The successful self-management of MS requires learning about the disease, its symptoms, and treatments; monitoring health status; making healthy lifestyle choices (such as eating organic foods, taking dietary supplements, avoiding certain foods, and exercising); establishing short- and long-term self-management goals; managing psychological health; developing supportive networks; finding health-care providers who support self-management; managing fatigue through extensive planning, pacing, prioritizing, and delegating of activities; and cognitive restructuring (such as rephrasing one's self-talk) to deal with anger and frustration resulting from living with MS.3,9,10

In recent years, self-management programs have been designed for individuals with MS, and their effectiveness was shown in several systematic reviews as measured by self-efficacy and quality of life measures.11,12 The majority of the people with MS involved in these studies have expressed a keen desire to participate in self-management programs, not only to learn about their condition but also to interact with others who share similar challenges.4,13,14

Prior to the availability of an MS self-management tool, most clinicians and researchers relied on the assessment of self-management components (eg, self-efficacy, which is associated with improvement in health status).15 Self-efficacy tools were commonly used to evaluate the usefulness of self-management programs. However, self-efficacy fails to capture all dimensions of MS self-management independently, and the need for a multidimensional, disease-specific self-management tool was noted.15,16

Bishop et al.17 developed the Multiple Sclerosis Self-Management Scale (MSSM) through consultation with health-care providers who are MS experts and a review of the literature. The MSSM was then revised to further enhance its factor structure, to remove redundant items, and to add more MS-specific items.18 The reliability of the revised MSSM was supported by high internal consistency, α = 0.85, and the construct validity was established through correlational studies. More specifically, the MSSM showed positive correlations with the Delight-Terrible Scale (r = 0.29) and the MS Self-Efficacy Scale subcategories of Functional (r = 0.26) and Control (r = 0.31). The MSSM also had negative correlations with psychological (r = 0.24) and physical (r = 0.28) components of the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29).

To date, however, the MSSM has not been shown to be stable over time to allow evaluation of changes in self-management skills of people with MS (test-retest reliability), it has not been related to gold standard measures in self-management (criterion validity), and it has not been assessed to be a valid measure of self-management from the users' perspective (face validity). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the revised version of the MSSM for test-retest reliability, criterion validity, and face validity.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional design was used to undertake this study. To evaluate test-retest reliability of the MSSM, participants completed the MSSM twice, 2 weeks apart. Criterion validity was evaluated by comparing the MSSM to two generic psychometrically tested scales regularly used to assess self-management. To determine the face validity or relevance of this measure for those who use it, participants' perspectives on the MSSM were ascertained. Participants indicated how well the MSSM reflected self-management dimensions of MS on a 5-point Likert-type scale. They were also asked whether any MSSM items should be changed or new items should be added. The study was granted ethical approval from the relevant university and hospital boards.

Participants

Convenience sampling was used to recruit people with MS from an MS clinic by means of recruitment posters. Individuals were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were aged 19 years or older, were able to read and write in English, and had a confirmed diagnosis of MS. To evaluate and capture the self-management components of MS exclusively, participants were excluded if they had comorbidities such as cancer, diabetes, or other neurologic illnesses.

Data-Collection Procedures

Data were collected at two time points. At Time 1, a package containing two copies of the consent form, the MSSM, the relevant study questionnaires, and an addressed, stamped envelope was mailed to the study participants. To clarify the aim and to enhance their understanding of this study, participants were provided with the definition of self-management, as described by Corbin and Strauss,8 and asked to consider their experience with self-management. The relevant study questionnaires were a demographic information sheet, the face validity questionnaire, and two measures for the assessment of criterion validity: the Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ) and the Partners in Health (PIH-12). To address participants' questions or concerns, participants were contacted by telephone or e-mail a few days after the package was mailed. Participants completed the materials and returned them to the research team in the addressed, stamped envelope provided.

At Time 2, the second package containing the MSSM, a gift card in recognition of their study participation, and an addressed, stamped envelope was mailed to the study participants who returned the first package. Again, the participants were contacted by telephone or e-mail a few days after the second package was mailed in order to address any questions or concerns.

Measures

Multiple Sclerosis Self-Management Scale (MSSM)

The MSSM is a multidimensional tool for the measurement of self-management knowledge and behavior among individuals with MS. This scale has 24 items and 5 factors. The factors are Health Care Provider Relationship/Communication, Treatment Adherence/Barriers, Social/Family Support, MS Knowledge & Information, and Health Maintenance Behavior. This measure is formatted in a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 representing “disagree completely” and 5 representing “agree completely.” Higher scores on the measure represent better self-management.

To establish criterion-related validity of the MSSM, two generic self-management tools, the heiQ and the PIH-12, were used.

Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ)

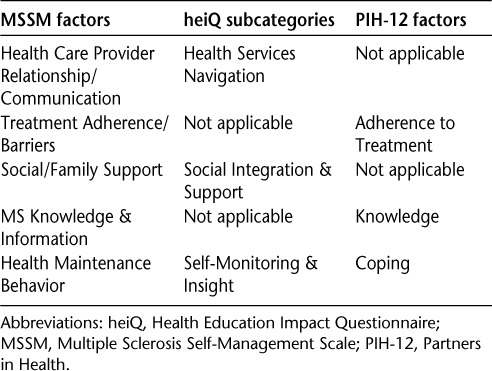

The heiQ is a questionnaire assessing generic self-management programs and has high construct validity, which was established using confirmatory factor analysis.19 The heiQ consists of 42 items and 8 independent subcategories. Three subcategories matching factors on the MSSM that were included in this study were Health Services Navigation, Social Integration & Support, and Self-Monitoring & Insight (Table 1). These subscales have good reliability, with Cronbach α values of 0.82, 0.86, and 0.70, respectively.

Table 1.

Measures used to determine criterion validity

Partners in Health (PIH-12)

The PIH-12 scale is a generic scale for measurement of self-management knowledge and behavior among individuals with chronic illness and is valid and internally consistent (Cronbach α = 0.82).20 It consists of four factors: Knowledge, Adherence to Treatment, Coping, and Management of the Condition. The questionnaire has 12 items that are self-rated on a Likert scale of 0 to 8, with 0 indicating poor self-management and 8 indicating high self-management. Three factors (Knowledge, Coping, and Adherence to Treatment) on the PIH-12 matched the MSSM subscales and were used for assessment of criterion validity (Table 1).

Measure Used to Test Face Validity

In order to assess face validity, people with MS were asked to appraise the degree to which they considered the tool to be credible.21 The face validity questionnaire for the MSSM consisted of three questions. First, the participants were asked to rank how well the MSSM reflects self-management dimensions of MS on a 5-point scale, ranging from “not applicable/irrelevant” to “very applicable/relevant.” In addition, in two open-ended questions the participants were asked to specify the self-management components that need to be added to the MSSM as well as make suggestions for the addition or removal of MSSM items.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS, version 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The test-retest reliability was analyzed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC1,1), with 95% confidence interval (CI). A minimum ICC1,1 coefficient of 0.70 between Time 1 and Time 2 suggested that the tool is consistent over time.22

Criterion validity was analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficients. Pearson correlation coefficients ranging from 0 to 0.25 were considered poor; 0.26 to 0.49, low; 0.50 to 0.69, moderate; 0.70 to 0.89, high; and 0.90 to 1.00, very high.23

The mean score of the question pertaining to face validity was calculated. The research team reached a consensus that a score below 2.5 is considered poor; 2.5 to 3.45, moderate; 3.5 to 4.45, high; and above 4.5, very high. The comments on the open-ended questions were collected on a Microsoft Word document. The research team reviewed the comments independently and reached consensus about the emerging issues.

Results

Forty-seven individuals volunteered for this study. Two individuals did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 14 participants failed to return the first package. Thirty-one participants were included in the study, of whom 27 completed both Time 1 and Time 2. The reasons for participants' dropping out included having other priorities in life, packages being lost in the mail and never received by the research team, and researchers' inability to contact potential participants.

As demonstrated in Table 2, the average age of the study participants was 49.4 years, and the mean time since MS diagnosis was 11.8 years. The majority of study participants were female, married or common law, and college-educated, and most had relapsing-remitting MS.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 31)

Test-Retest Reliability

Test-retest reliability was examined for the total MSSM score as well as each factor in the MSSM. The results are shown in Table 3. The overall ICC1,1 between Time 1 and Time 2 was 0.83. The ICC1,1 ranged from 0.64 to 0.88 for the five factors in the MSSM. There was no statistically significant difference between Time 1 and Time 2, suggesting satisfactory test-retest reliability.

Table 3.

Test-retest reliability: ICC analysis with 95% CI

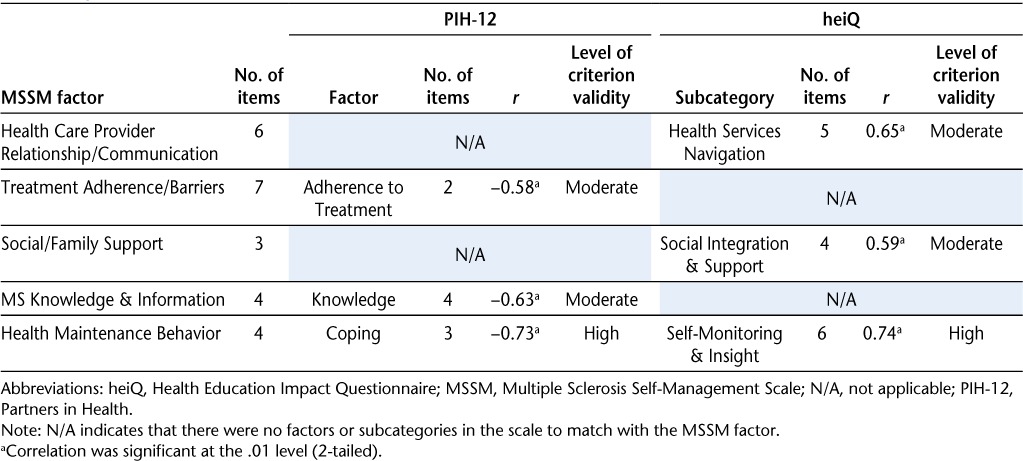

Criterion Validity

As shown in Table 4, all the MSSM factors possessed moderate to high criterion validity with the relevant subscales or factors within the heiQ and PIH-12 measures. These correlations were significant at P = .01.

Table 4.

Criterion validity: correlation of MSSM factors with PIH-12 factors and heiQ subcategories

Face Validity

Twenty-five (80.65%) of the 31 participants who finished Time 1 rated how well the MSSM reflected self-management components of MS on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The mean score was 3.31, suggesting moderate face validity of the MSSM from the perspective of people with MS.

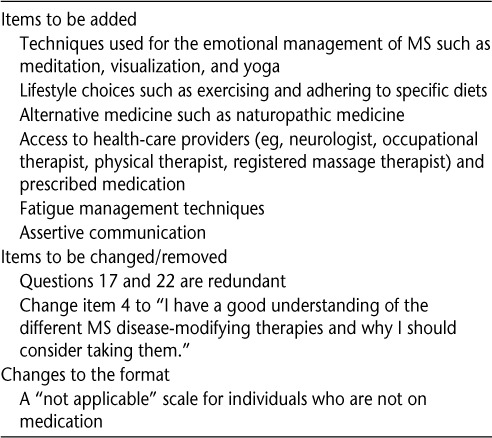

The analysis of participants' comments suggested a need to add items to the MSSM, to remove redundant items, and to make changes to its format. Participants indicated that additional items concerning access to the health-care system, lifestyle choices, and symptom management techniques were required. Participants also provided recommendations on changes to two items in the MSSM and to its format. Participants' comments are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Face validity: examples of item and format changes suggested by participants

Some participants noted a need for items regarding access to the health-care system such as satisfaction with the frequency of seeing health-care providers and lack of insurance coverage for some medications. Also suggested was a greater emphasis on lifestyle choices such as adhering to a specific diet, taking supplements, and exercising, as well as items relating to emotional management of MS. Techniques identified for such emotional management included visualization, yoga, and meditation. In addition, fatigue management techniques were regarded as essential to self-management, as suggested by two participants with the following comments: “. . . to schedule my day so that I do not become overtired” and “Sometimes people forget that I cannot do everything I used to do.”

Format changes were also recommended, particularly to questions about medication. Frustration was expressed about the emphasis on medication adherence, particularly by those not taking medication. These individuals indicated that the MSSM does not reflect their management of MS and recommended a “not applicable” response option. Participants also suggested wording changes for some items and identified redundancy across items. A participant suggested that the item “I have a good understanding of why I take my medications and what they are supposed to do” should be changed to “I have a good understanding of different MS disease-modifying therapies and why I should consider them” to make the item more applicable to all individuals with MS. Also, a few participants found the items “Taking my medication is a routine part of my regular activities (like brushing my teeth) and “I don't even think about it; taking my medication is just a habit now” redundant.

Discussion

The MSSM, the only available tool to assess self-management among individuals with MS, was found to possess satisfactory to good test-retest reliability over a 2-week interval, moderate to high criterion validity for the factor structure, and moderate face validity.

The overall test-retest reliability of the MSSM was good for the measure as a whole and for four of the five factors. The MS Knowledge & Information factor failed to achieve satisfactory test-retest reliability, perhaps because of the volatile nature of the MS disease course and changing health status, which challenge one's confidence in knowledge of the condition. This result may also be due to the items included in this factor. For example, item 4 evaluates two constructs: understanding medications and appreciating their impacts on one's health status. While knowledge about medications might be stable over 2 weeks, study participants may become unsure of the medication's efficacy when experiencing a relapse or may be frustrated with medication side effects. Thus, the evaluation of one construct per item may enhance the test-retest reliability of this factor.

In addition, the 95% CIs for two factors, MS Knowledge & Information and Health Care Provider Relationship/Communication, are wide. The wide CI could be due to the small study sample size. In addition, comments from our participants revealed that many were unsure which health-care provider was being referred to in the Health Care Provider Relationship/Communication items, as most individuals with MS receive care from more than one health-care provider (eg, family physician, neurologist, physical therapist, occupational therapist). Specific questions may lessen confusion among people with MS and might narrow the CI of this factor.

The evaluation of the MSSM factors with appropriate PIH-12 factors and heiQ subscales suggests moderate to high criterion validity. However, not all heiQ and PIH-12 factors are present in the MSSM. For example, the Constructive Attitude & Approaches, Positive & Active Engagement in Life, and Health Directed Behavior subcategories on the heiQ cannot be matched to any factors in the MSSM. Similarly, there is no suitable counterpart for the PIH-12 Recognition & Management of Symptoms factor on the MSSM. This lack of parallel factor structure across the measures suggests that there may be numerous dimensions that are not accounted for in the MSSM to fully capture this multidimensional construct. The moderate mean face validity score along with the participants' comments regarding the MSSM further validates the need to include these self-management components.

The principles of self-management can serve as a guideline to identify the missing components of the MSSM. Some self-management principles such as “monitoring and managing signs and symptoms of MS,” “managing the impact of the condition on physical, emotional, and social life,” “adopting a lifestyle that promotes health,” and “having confidence, access and the ability to use support services” that are highlighted by the Flinders model24 are underrepresented in the MSSM.

In addition, some strategies employed by individuals with MS to manage the symptoms and to reduce the disease's impact on their lives are overlooked in the MSSM. For instance, there is only one item related to fatigue, which has been shown to reduce the quality of life of individuals with MS.25 Many fatigue management strategies such as energy conservation and activity modifications are not included in the MSSM.25 Another example is related to emotional distress such as anxiety and depression. While social support is important for mental well-being, many other effective strategies26 are not identified on the MSSM. More importantly, a number of incapacitating MS symptoms such as bowel and bladder incontinence and pain impede employment and social participation.27 Thus, items are required to more fully assess the many complex dimensions of MS self-management.

Many individuals with MS adopt a healthy lifestyle to minimize the intrusion of MS symptoms on their lives. The strategies reported include adhering to low-fat diets, taking dietary supplements, and following physical exercise programs.27,28 These items are included in the Positive & Active Engagement in Life subcategory in the heiQ scale but are not addressed on the MSSM.

Access and the ability to use support services are not addressed in the MSSM. Successful self-managers report benefits from consulting a variety of health-care providers to hone their coping and problem-solving skills, particularly related to accessing and fully using health insurance programs, special programs that fund assistive devices, and home support.27 Items related to this area are recommended for an MS self-management assessment.

The high correlation between selected MSSM factors and the PIH-12 and heiQ subcategories was unanticipated. Specifically, the Health Maintenance Behavior of the MSSM showed a significant high correlation with both the Coping factor on the PIH-12 and the Self-Monitoring & Insight subcategory on the heiQ. While most items on both the Coping factor of the PIH-12 and the Self-Monitoring & Insight subcategory of the heiQ pertain to symptom management of chronic conditions, only two items (5 and 19) on the Health Maintenance Behavior factor of the MSSM address symptom management in MS. The other two items (7 and 8) concerning practicing health-promoting behaviors demonstrated a high correlation that could be due to a ceiling effect.

A ceiling effect was observed in all questionnaires in our study. The majority of study participants were married or common law and college-educated, with a high household income. These characteristics could be associated with greater access to information, resources, and support, leading to better self-management skills and behaviors. Also, study participants had been living with MS for an average of 11.8 years. It is very likely that these individuals have developed, over time, good self-management skills through trial and error, life experience, and interaction with health-care providers. The observed ceiling effect restricts the external validity of our results.

This study has limitations. Participants were recruited from one MS clinic with a limited geographic catchment area, limiting the generalizability and external validity of these findings. It is also not clear whether the study subjects had participated in self-management programs prior to this study. Lastly, participants' cognitive abilities, which might have affected the results, were not evaluated.

Conclusion

The results of this cross-sectional study suggest that the MSSM possesses satisfactory to good test-retest reliability, moderate to high criterion validity, and moderate face validity. The MSSM, however, is lacking relevant self-management items related to accessing diverse services in health-care and social systems, accessing medication, following treatment plans, possessing skills to reduce the impact of MS symptoms in daily life, and practicing healthful behaviors. These components are required to enhance both criterion and face validity of a self-management measure for MS.

PracticePoints.

The Multiple Sclerosis Self-Management Scale possesses satisfactory to good test-retest reliability, moderate to high criterion validity for the available factors, and moderate face validity.

According to self-management principles, additional items are necessary concerning following the treatment plan, having access to the health-care system and medication, possessing skills to manage the symptoms of MS, and practicing healthy lifestyle choices.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by a National Multiple Sclerosis Society Post-doctoral Scholarship, a grant from the University of British Columbia Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy James B. Russell Research Fund, and a Trainee Travel Award from the Western Pacific endMS Regional Research and Training Centre.

References

- 1.Litchfield J, Thomas S. Promoting self-management of multiple sclerosis in primary care. Prim Health Care. 2010;20:32–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Managing MS symptoms. Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada. Updated October 2011. http://mssociety.ca/en/information/symptoms.htm.

- 3.Malcomson K, Lowe-Strong A, Dunwoody L. What can we learn from the personal insights of individuals living and coping with multiple sclerosis? Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:662–674. doi: 10.1080/09638280701400730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Audulv Å, Norbergh K, Asplund K, Hörnsten Å. An ongoing process of inner negotiation—a grounded theory study of self-management among people living with chronic illness. J Nurs Healthcare Chronic Illness. 2009;1:283–293. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop M, Frain MP, Tschopp MK. Self-management, perceived control, and subjective quality of life in multiple sclerosis: an exploratory study. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2008;52:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorig K, Ritter PL, Plant K. A disease-specific self-help program compared with a generalized chronic disease self-help program for arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2005;53:950–957. doi: 10.1002/art.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbin JM, Strauss A. Unending Work and Care: Managing Chronic Illness at Home. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorne S, Paterson B, Russell C. The structure of everyday self-care decision making in chronic illness. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:1337–1352. doi: 10.1177/1049732303258039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courts NF, Buchanan EM, Werstlein PO. Focus groups: the lived experience of participants with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones F, Riazi A. Self-efficacy and self-management after stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:797–810. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.511415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plow MA, Finlayson M. A scoping review of self-management interventions for adults with multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;3:251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlow J, Edwards R, Turner A. The experience of attending a lay-led, chronic disease self-management programme from the perspective of participants with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health. 2009;24:1167–1180. doi: 10.1080/08870440802040277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barlow J, Turner A, Edwards R, Gilchrist M. A randomised controlled trial of lay-led self-management for people with multiple sclerosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du S, Yuan C. Evaluation of patient self-management outcomes in health care: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;57:159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig P, Dieppe P, MacIntyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guide. Medical Research Council. www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance. Published September 29, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Bishop M, Frain M. Development and initial analysis of multiple sclerosis self-management scale. Int J MS Care. 2007;9:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishop M, Frain MP. The multiple sclerosis self-management scale: revision and psychometric analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56:150–159. doi: 10.1037/a0023679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Whitfield K. The Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ): an outcomes and evaluation measure for patient education and self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petkov J, Harvey P, Battersby M. The internal consistency and construct validity of the Partners in Health scale: validation of a patient rated chronic condition self-management measure. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1079–1085. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9661-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundation of Clinical Research: Application to Practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munro BH. Statistical Methods for Healthcare Research. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Flinders ProgramTM. Flinders University School of Medicine. http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/fhbhru/self-management.cfm. Published 2013. Updated March 23, 2013.

- 25.Boissy AR, Cohen JA. Multiple sclerosis symptom management. Exp Rev Neurotherapeutics. 2007;7:1213–1222. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.9.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Artemiadis AK, Vervainioti AA, Alexopoulos EC, Rombos A, Anagnostouli MC, Darviri C. Stress management and multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;27:406–416. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acs039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ploughman M, Austin MW, Murdoch M, Kearney A, Godwin M, Stefanelli M. The path to self-management: a qualitative study involving older people with multiple sclerosis. Physiother Canada. 2012;64:6–17. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2010-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doring A, Pfueller CF, Paul F, Dorr J. Exercise in multiple sclerosis: an integral component of disease management. EPMA J. 2012;3:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s13167-011-0136-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]