Abstract

Objective

To use observation to understand how decisions about higher-risk treatments, such as biologics, are made in pediatric chronic conditions.

Methods

Gastroenterology and rheumatology providers who prescribe biologics were recruited. Families were recruited when they had an outpatient appointment in which treatment with biologics was likely to be discussed. Consent/assent was obtained to video the visit. Audio of the visits in which a discussion of biologics took place were transcribed and analyzed. Our coding structure was based on prior research, shared decision-making concepts, and the initial recorded visits. Coded data were analyzed using content analysis and comparison with an existing model of shared decision making.

Results

We recorded 21 visits that included discussions of biologics. In most visits, providers initiated the decision making discussion. Detailed information was typically given about the provider’s preferred option with less information about other options. There was minimal elicitation of preferences, treatment goals or prior knowledge. Few parents or patients spontaneously stated their preferences or concerns. An implicit or explicit treatment recommendation was given in nearly all visits, although rarely requested. In approximately 1/3 of visits the treatment decision was never made explicit, yet steps were taken to implement the provider’s preferred treatment.

Conclusion

We observed limited use of shared decision making, despite previous research indicating that parents wish to collaborate in decision making. To better achieve shared decision making in chronic conditions, providers and families need to strive for bidirectional sharing of information and an explicit family role in decision making.

Keywords: chronic disease, decision making, biologics, family centered care

Pediatric chronic conditions often result in lengthy decision-making processes that challenge parents, patients and providers.(1–4) In adult healthcare settings, collaboration with providers has been shown to reduce patients’ worry, decision regret and decision conflict by addressing preferences and treatment goals during the decision process.(5) Like adult patients, parents of children with chronic conditions have interest in collaborating with providers to make treatment decisions.(1, 6, 7) For example, in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), parents mention interactions with healthcare providers as key aspects of decision making about higher-risk treatments, such as biologic therapies.(8)

Shared decision making (SDM) is a process whereby providers present the evidence and medical context while eliciting parents’ or patients’ values and preferences. They then strive to reach an agreement about the best treatment option.(9) This approach has been encouraged by national and international organizations.(10–14) Nevertheless, retrospective studies focused on SDM(6, 15) and observational studies focused on general clinical interactions(4, 16) show limited use of SDM in pediatrics. However, there has been little prospective, observational research focused specifically on the treatment decision-making experience, especially in pediatric chronic conditions.

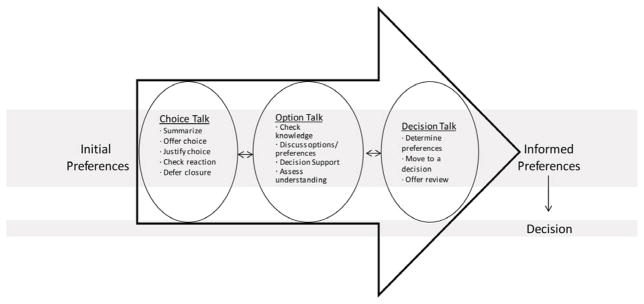

Although varying in specifics, published models of SDM focus on collaborative decision making based on patient/family preferences and an understanding of the options.(17) Given the known benefits of SDM(18–21) we were interested in the extent to which observed clinic visits fit an existing model, “the shared decision making model for clinical practice” (Figure; available at www.jpeds.com).(22) This model was chosen because it is based on the same principles as other models but is more specific than many (9, 17) and is applicable in diverse clinical settings.

Figure.

Shared Decision Making Model for Clinical Practice (adapted with slight modifications from Elwyn et al, 2012)

Our objective was to understand how decisions about biologics, as a model of higher-risk treatments, are made in pediatric chronic conditions by observing the extent to which they fit the chosen model.

METHODS

Physicians and one nurse practitioner (collectively referred to as providers) who treat patients with either JIA or IBD were recruited from the rheumatology and gastroenterology clinics of a large academic children’s hospital. All but one of the approached providers agreed to participate. Written consent was obtained from all participating providers. Eligible families were those who had a clinic appointment scheduled with a consented provider and the provider anticipated discussing biologic treatment initiation, based on pre-clinic planning or providers’ personal knowledge of the patient. After provider approval to approach the family, consent and assent (for children age 8–17) was obtained from anyone who would be in the room during the visit. We recruited families until we reached informational saturation, the point at which 2 consecutive visits revealed no new approaches to discussing treatment decisions.(23)

Families were compensated $30 for participation. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

In previous studies using audio recording(8) we had difficulty distinguishing voices and determining when people entered and exited the room. Therefore this study’s primary mode of data collection was video recording. A video camera was set-up in the exam room and positioned to avoid viewing the exam table. A back-up audio recording was also made and used for one visit where video recording failed.

Recording continued until, at a minimum, the provider left the room with no plan to return. Parents and providers were informed they could turn off the camera at any time, although none did. Demographic information was collected after the visit.

Data coding and analyses

Each recording was reviewed to see if it included a discussion of treatment with biologics. The audio of any video in which the family discussed biologics with a provider was transcribed. Each transcript was compared with the video, corrected as needed, and non-verbal interactions and contextual details (eg, child left room) were added.

Our codebook was based on review of the first two visits in each clinic, our prior work in the area,(8, 24, 25) and information exchange and decision-making concepts informed by Roter(26) and Elwyn.(27) After watching each video in its entirety, visits were coded from the transcripts with coders referring back to the videos as necessary. Initially, two researchers independently coded all video transcripts, adding codes as needed and resolving differences through discussion. Once they had only minor discrepancies in their coding patterns (after 7 transcripts), coding was completed by one person and reviewed by the second to look for missing codes. To facilitate content analysis,(28) coded data were then organized according to the 3 key provider-patient interaction steps of our chosen model (choice talk, option talk and decision talk) and compared with the ideals set forth for each step.(22) NVivo 8 (QSR International, Victoria, Australia) was used to assist with data coding and organization.

RESULTS

We recorded 21 visits that included discussion of treatment with biologics. The demographics of these 21 families and their providers are shown in Table I. Four visits (2 in each clinic) included 2 providers (fellow and attending physician). Mothers were present in all visits. Fathers were present in 2 gastroenterology and 6 rheumatology visits.

Table 1.

Participants

| Characteristic | Gastroenterology | Rheumatology |

|---|---|---|

| Provider (n) | 4 | 6 |

| Years in Subspecialty | ||

| Median (Range) | 9.5 (3–19) | 16.2 (1–33) |

| Sex (n) | ||

| Male | 3 | 3 |

| Female | 1 | 3 |

| Provider type (n) | ||

| Physician | 4 | 5 |

| Nurse Practitioner | 0 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Patient (n) | 12 | 9 |

| Median Age in Years (Range) | 11.5 (7–16) | 9 (2–18) |

| Decision Made (n) | ||

| Start biologic therapy | 6 | 5 |

| Start Other Treatment | 3 | 0 |

| No Change in Treatment | 0 | 3 |

| Testing | 3 | 0 |

| Defer Decision | 0 | 1 |

| Maternal Education (n) | ||

| < College Degree | 2 | 5 |

| 4-year College Degree | 6 | 1 |

| > College Degree | 4 | 3 |

Our results primarily focus on the interaction between parents and providers because, with few exceptions, the child and adolescent patients had little role in the decision. In fact, 2 families intentionally excluded the patient from discussion by not bringing him to the appointment or by having him leave the room during the treatment discussion. Most patients sat quietly during the visit except to answer social questions or questions about their symptoms. However, there were a few instances where, at the end of the decision-making process, we observed the parent or provider turning to the patient and asking a version of “are you okay with this?” In all observed instances patients quickly agreed to the plan.

In 3 visits with adolescents the patient actively participated in treatment discussions; one through a pre-clinic “homework” assignment to read about biologics and the others through in clinic discussion. In these situations the adolescents asked questions about treatment logistics and expressed concerns about infusions and injections, but did not otherwise express treatment goals or preferences. In only one case was the patient’s preference referenced when making the final decision.

The remaining results are structured according to the three key steps of the shared decision making model for clinical practice: Choice Talk, Option Talk and Decision Talk.(22) Quotations related to each step are in Table, as are notations for aspects of the model we never observed. Of note, the treatment decision making portion of observed visits did not differ noticeably between those who made a treatment decision and those decided on further testing prior to finalizing their treatment decision, nor by whether or not a father was in attendance.

Choice Talk

“Choice talk” is characterized by introducing the idea of treatment choice. Before listing specific options, providers are encouraged to summarize the situation, explain there is a choice, and remind families of the importance of their preferences. The provider then assesses individuals’ reactions to the situation and, if necessary, defers closure of the discussion.

In all but 2 visits, it was the provider who initiated “choice talk” and moved the conversation towards treatment decision making. The 2 cases where a parent initiated this step included a second opinion visit and one in which the patient was seeing multiple subspecialists. After initiating the decision-making conversation, providers moved forward by listing treatment choices or by reviewing the patient’s disease course, rather than with a more general statement about the existence of choice (Table II). There were no visits in which the idea of choice was introduced separately from listing options. Similarly, the role of personal preference was never explicitly mentioned. Providers appeared to assess parents’ or patients’ reactions to the options only when someone was overtly distressed, as indicated by their tone, questions, or tears.

Table 2.

Quotations Related to “Choice Talk”

| Concept | Speaker | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Initiate “choice talk” | IBD Provider | “You know one thing for sure is that despite the 6MP medicine and the other medicines, things haven’t completely healed. They just---they kind of wax and wane.” |

| JIA Provider and Mother | ”So the arthritis is still there. So it brings up the question…” “What do we do next?” “Yeah. What do we do next?” |

|

| Summarize the situation | IBD Provider | “For the most part [patient] has had a, what we would call a very stable remission but some of the belly pain that he occasionally gets and the joint pain is from the Crohn’s not being completely healed….” |

| Discuss the existence of choice | Never observed | |

| Importance of family preferences | Never observed | |

| Assess reaction to the situation | Mother and IBD Provider | “… I never wanted to talk about [infliximab].” “How come?” “I’m just afraid of-- ya know-- those scary side effects.” |

| Provide a recommendation; rather than deferring until later | Mother and JIA Provider |

“Well, let me ask this, which one would you recommend?” “Probably, the first one we used, the one we have the most experience in kids is Enbrel.” |

| IBD Provider | “So that’s why I think for him in particular it would be better to go with the Remicade up front.” |

Italics indicate a step that was not observed or is in contradiction to SDM model.

The model encourages providers to help prevent premature decision making by deferring recommendation requests. We found no such instances of deferral. Rather, when a recommendation was requested, the clinician provided one immediately (Table I). Additionally, in many visits the provider offered a recommendation without anyone requesting it.

Option Talk

This step focuses on information exchange and providing detail about the options. It includes assessing pre-existing knowledge and discussing options and individual preferences. This is the step where decision support tools (ie, printed or video aids designed to help define treatment preferences and goals) might be used followed by an assessment of individuals’ understanding of the options.

Although providers and parents often referenced prior conversations about biologics, in only a few instances did the provider investigate pre-existing knowledge, such as by asking about family members’ understanding of the next step or inquiring about what they had read about biologics (Table III). More typically providers said something like, “what we talked about last time was…” or “so to remind you…” and then presented information.

Table 3.

Quotations Related to “Option Talk”

| Concept | Speaker | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Assessing knowledge | IBD Provider | “So what’s your understanding of kind of the next step?” |

| Presenting Options | JIA Provider | “…we’re going to try a daily pill called Arava which helps about half of folks…and then there’s a sulfa drug called Asulfadine and it helps about 40% of people…” |

| JIA Provider | “But that’s an option, the leflunomide and the other option is an anti-TNF agent like Enbrel...” | |

| IBD Provider | “…the next steps from treatment would be either thinking of methotrexate or Humira.” | |

| Discussing treatment harms and benefits | IBD Provider | “Possible side effects, there’s a possibility of an allergic reaction to it--that happens in about 1 out of 100 people, so it’s rare.” |

| JIA Provider | “May be 1% of the patients will get low white cell counts, moderately low, not chemo-type low, just moderately low.” | |

| IBD Provider | “It’s just that overall about 80% of kids do completely better on Remicade and get healing, and with methotrexate that’s more around 40 to 50%. So it’s just that the odds of the Remicade working are higher.” | |

| Explore preferences | Never observed | |

| Provide Decision Support | IBD Nurse | “So look over those [referring to handout]…It’s what you need to know and as you read through them, think about your questions.” |

| Assess Understanding | IBD Provider | “Questions so far? Do you understand the rationale for what I’m talking about, the reasoning?” |

Italics indicate a step that was not observed or is in contradiction to SDM model.

Information was typically delivered in one of two ways. In the first, the provider spoke with limited interruption from the family, aside from intermittent acknowledgement (e.g. “uh-huh” or “Okay”). The second was a back-and-forth discussion, most often prompted by parents’ questions about side effects, efficacy or treatment logistics. In this situation, the provider changed the order of information presentation but the content and degree of detail appeared unchanged, as determined by observing multiple visits with the same providers. In a few situations, parents or patients asked questions and were told, “Hold onto your questions” or “that’s one of things that I was getting to, OK?” but the question was never answered. Some providers peppered their discussion with “okay?” but never waited for a response. Others reached the end of information delivery and then asked if there were questions. When questions were elicited late in the visit, parents asked fewer question, limiting providers’ ability to determine parents’ understanding or concerns.

The model suggests that the provider should “generate dialog and explore preferences,” as well as discuss treatment harms and benefits. We found that providers delivered information about harms and benefits with little focus on creating dialog or eliciting preferences. Often, only the provider’s preferred treatment option was discussed in detail.

Option Talk ends by providing decision support tools and assessing understanding of the options. In some visits providers referenced informational handouts. Formal decision tools were used only once, when a provider was testing a tool under development. Assessment of understanding typically consisted of providers asking a general, “ok?” or “Is this making some sense?” without eliciting any detail.

Decision Talk

This last step of the model focuses on determining preferences, moving to a decision and offering an opportunity to review the decision in the future.

Providers were most likely to elicit preferences when the choice was between 2 very similar treatments, such as the injectable biologics used in JIA. Such elicitation happened much less frequently in IBD but was typically framed as a choice between biologics or a different class of treatment. Information related to preferences was more often expressed spontaneously or as part of acknowledging what the provider had said (Table IV). Examples of such preferences included avoiding side effects, preferring oral over injected medication, or desiring improved growth.

Table 4.

Quotations Related to “Decision Talk”

| Concept | Speaker | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Determine preferences | JIA Provider | “You want to feel better and on the other hand you don’t want a shot, am I hearing correctly?” |

| IBD Mother | “We prefer [injection done at home]. Then he doesn’t have to go somewhere where there’s other people who don’t feel well or whatever.” | |

| IBD Mother | “I’m just afraid of—I just—ya know, those scary side effects. | |

| JIA Patient | “I’d like to go with the highest chance [for improvement].” | |

| Assess readiness to make a decision | Never observed | |

| Move to a decision | IBD Provider | “Should we go and start the Remicade or not?” |

| JIA Provider | “So you should be thinking now about how you want to proceed…basically two injections a week at the most or fewer depending on what you choose. It could be monthly infusion.” | |

| Offer a future review of the decision | Never observed |

Italics indicate a step that was not observed or is in contradiction to SDM model.

The concept of “moving to a decision” focuses on determining whether the family is ready to make a decision and, if not, what information is still needed. Although no provider asked about readiness to make a decision, 2 visits started with the provider eliciting where in the decision-making process the family was. Most visits did not include an assessment of the parents’ or patient’s readiness to make a decision nor of their preferred treatment option. In fact, in about 1/3 of visits there was no explicit statement of decision making. Yet steps were taken towards implementation of the provider’s preferred plan.

Although some parents and patients asked if the treatment was “for the rest of his life,” no provider indicated that there would be future opportunities to review the decision made. It was implied that stopping medication was a future decision, separate from the decision to start treatment.

DISCUSSION

Despite national and international efforts to expand the use of SDM,(10–14) (29) in observed clinical encounters we found no step in the process where there was consistent use of SDM techniques. Comparing clinical encounters, from 2 different settings, to a SDM model specifically designed for clinical practice, allows us to consider the experience of chronic disease decision making in a way that previous studies have not. We found providers consistently give verbal information, answer questions and offer recommendations. However, the information exchange was primarily unidirectional, from provider to parent. Providers did not often elicit information from parents; nor did many parents volunteer information about their goals and preferences. Consistent with other observations of pediatric clinical encounters,(4, 16, 30, 31) very little effort was made to include patients, of any age, in decision making.

Our results, combined with observational studies in attention deficit disorder (ADHD), (15) asthma, (16) and at the time of IBD diagnosis,(4) suggest that challenges in implementing SDM occur across diverse pediatric chronic conditions. Engagement in SDM requires bidirectional information exchange,(9) preferably between prepared providers and activated families.(32) To achieve this, providers need to elicit family preferences, concerns and readiness to make a decision. Additionally, families need to be taught the importance of their goals and preferences and empowered to participate in decision making, so that their participation does not depend upon the physician eliciting their goals and preferences. Encouraging such participation may help eliminate parents’ on-going worries(1, 8) through improved understanding and decisions that are consistent with their goals and preferences.

One way to empower families is through the use of decision support tools. Most such tools are designed for use outside of the clinical encounter, directing patients to consider their preferences and values prior to the visit.(21) Others have developed tools that facilitate conversations between patient and provider.(33, 34) Given the significant changes that are needed before pediatric SDM is realized, a combination of approaches may be warranted and has been shown to be successful in ADHD decisions.(34) Moreover, although changing provider practice is challenging,(35, 36) communication training, particularly related to communicating choice, may further facilitate SDM while simultaneously addressing other communication deficits. Such training could also foster the inclusion of pediatric patients in developmentally appropriate aspects of decision making.

The inclusion of JIA and IBD broadened the range of decisions we observed due to slightly different treatment options in each disease. This difference highlighted areas in which SDM may be easier, such as with the similar, injectable biologics in JIA. However, in most situations, providers in each disease were more prescriptive. This is true despite the fact that the options have different risk/benefit profiles that may influence which choice best fits a family’s treatment goals and preferences. Previous research has shown that parents view SDM as a collaborative partnership between equals and clinicians view it as a way persuade families to agree to treatment recommendations.(6) Thus, it is possible that providers believe they are sharing decisions. Alternatively, it is possible that providers did not think that SDM was an appropriate approach for this decision or for specific families. These possibilities further highlight the need for interventions that facilitate decision-making conversations and engage patients and parents in decision making.

Our study is limited by focusing on the clinical encounter. We have no knowledge of other decision-making steps unless they were discussed during the encounter. There is also some risk of a Hawthorne effect, although the presence of a video camera in the exam room has been shown to have minimal effect on patient and provider behaviors.(37) Moreover, any effect would likely have been to increase, rather than decrease SDM interactions, as most providers were aware of the investigators’ interest in shared decision making. As a qualitative study, this work is not intended to be generalizable but rather to enhance the current, limited understanding of SDM in pediatrics. Like most SDM models, the one we chose focuses largely on the role of the provider. We intentionally chose a model with very specific steps to be able to assess the process in detail, but most observed visits would also not have met simpler definitions of SDM.(9) Finally, such a rich dataset lends itself to numerous analyses. We have started with a content analysis but see opportunity for future detailed communication study and analysis of non-verbal behaviors. Additionally, research is needed that quantifies the decision-making experience and the variation seen between different clinical encounters.

Continued exploration of specific, challenging decisions, such as that to start biologics treatment, will provide a strong foundation for establishing and disseminating SDM in pediatric chronic conditions. By starting with a specific decision, there may be opportunities to modify existing tools(38–40) and communication skills(41, 42). Moreover, by focusing on a decision that occurs in more than one disease, tools can be developed and tested in multiple settings, increasing the likelihood of successful adaptation to other chronic conditions. Such steps will help the pediatric community achieve goals of family-centered care,(12) improved health communication and better outcomes through shared decision making.(10, 11)

Acknowledgments

Funded by a Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Place Outcomes Award and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (K23HD073149 to E.L.).

Abbreviations

- ADHD

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- JIA

juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- SDM

shared decision making

Footnotes

Portions of the study were presented as a poster at the International Shared Decision Making meeting.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brinkman WB, Sherman SN, Zmitrovich AR, Visscher MO, Crosby LE, Phelan KJ, et al. Parental angst making and revisiting decisions about treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2009 Aug;124:580–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruccio D, Steinkrauss L. Challenges of decision making for families of children with single or multiple chronic conditions. Nurse Pract Forum. 2000 Mar;11:15–9. Epub 2001/02/28. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie LK, Plemmons D, Monn AR, Palinkas LA. Investigating ADHD treatment trajectories: listening to families’ stories about medication use. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007 Jun;28:179–88. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3180324d9a. Epub 2007/06/15. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karnieli-Miller O, Eisikovits Z. Physician as partner or salesman? Shared decision-making in real-time encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Jul;69:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.030. Epub 2009/05/26. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kremer H, Ironson G, Schneiderman N, Hautzinger M. “It’s my body”: does patient involvement in decision making reduce decisional conflict? Med Decis Making. 2007 Sep-Oct;27:522–32. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07306782. Epub 2007/09/18. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiks AG, Hughes CC, Gafen A, Guevara JP, Barg FK. Contrasting parents’ and pediatricians’ perspectives on shared decision-making in ADHD. Pediatrics. 2011 Jan;127:e188–96. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1510. Epub 2010/12/22. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pyke-Grimm KA, Stewart JL, Kelly KP, Degner LF. Parents of children with cancer: factors influencing their treatment decision making roles. J Pediatr Nurs. 2006 Oct;21:350–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.02.005. Epub 2006/09/19. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipstein EA, Lovell DJ, Denson LA, Moser DW, Saeed SA, Dodds CM, et al. Parents’ information needs in tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor treatment decisions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Mar;56:244–50. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31827496c3. Epub 2012/10/13. Eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997 Mar;44:681–92. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. Epub 1997/03/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, D.C: 2010. [cited 2011 September 8]. Available from: http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine. Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington D.C: National Academy of Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pediatrics AAo. Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2003 Sep;112:691–7. Epub 2003/09/02. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coulter A, Parsons S, Askham J. Where are the patients in decision-making about their own care? World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Care NR. Shared Decision Making 2013. 2013 Sep 24; Available from: http://www.rightcare.nhs.uk/index.php/shared-decision-making/

- 15.Brinkman WB, Hartl J, Rawe LM, Sucharew H, Britto MT, Epstein JN. Physicians’ shared decision-making behaviors in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Nov;165:1013–9. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sleath BL, Carpenter DM, Sayner R, Ayala GX, Williams D, Davis S, et al. Child and caregiver involvement and shared decision-making during asthma pediatric visits. The Journal of asthma : official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2011 Dec;48:1022–31. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.626482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Mar;60:301–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. Epub 2005/07/30. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit MPT, Frosch D, Legare F, Montori VM, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. British medical journal. 2012 Jan;27:344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bieber C, Muller KG, Blumenstiel K, Schneider A, Richter A, Wilke S, et al. Long-term effects of a shared decision-making intervention on physician-patient interaction and outcome in fibromyalgia. A qualitative and quantitative 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Nov;63:357–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.05.003. Epub 2006/07/29. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bieber C, Muller KG, Blumenstiel K, Hochlehnert A, Wilke S, Hartmann M, et al. A shared decision-making communication training program for physicians treating fibromyalgia patients: effects of a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2008 Jan;64:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.009. Epub 2007/12/26. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, Barry M, Col NF, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2. Epub 2009/07/10. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Oct;27:1361–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1990. p. 532. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipstein EA, Muething KA, Dodds CM, Britto MT. “I’m the One Taking It”: Adolescent Participation in Chronic Disease Treatment Decisions. J Adolesc Health. 2013 Aug;53:253–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.004. Epub 2013/04/09. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipstein EA, Brinkman WB, Britto MT. What Is Known about Parents’ Treatment Decisions? A Narrative Review of Pediatric Decision Making. Med Decis Making. 2011 Oct 3; doi: 10.1177/0272989X11421528. Epub 2011/10/05. Eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roter D, Larson S. The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2002 Apr;46:243–51. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elwyn G, Hutchings H, Edwards A, Rapport F, Wensing M, Cheung WY, et al. The OPTION scale: measuring the extent that clinicians involve patients in decision-making tasks. Health Expect. 2005 Mar;8:34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00311.x. Epub 2005/02/17. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pope C, Mays N, editors. Qualitative Research in Health Care. 3. Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 3;368:6–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1209500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tates K, Meeuwesen L. ‘Let mum have her say’: turntaking in doctor-parent-child communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2000 May;40:151–62. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00075-0. Epub 2000/04/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wassmer E, Minnaar G, Abdel Aal N, Atkinson M, Gupta E, Yuen S, et al. How do paediatricians communicate with children and parents? Acta Paediatr. 2004 Nov;93:1501–6. doi: 10.1080/08035250410015079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Managed care quarterly. 1996 Spring;4:12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullan RJ, Montori VM, Shah ND, Christianson TJ, Bryant SC, Guyatt GH, et al. The diabetes mellitus medication choice decision aid: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Sep 28;169:1560–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brinkman WB, Hartl Majcher J, Poling LM, Shi G, Zender M, Sucharew H, et al. Shared decision-making to improve attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder care. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 Oct;93:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauchner H, Simpson L, Chessare J. Changing physician behaviour. Arch Dis Child. 2001 Jun;84:459–62. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.6.459. Epub 2001/05/23. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999 Oct 20;282:1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. Epub 1999/10/27. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penner LA, Orom H, Albrecht TL, Franks MM, Foster TS, Ruckdeschel JC. Camera-related behaviors during video recorded medical interactions. J Nonverbal Behav. 2007 Jun;31:99–117. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Group CM. Decision Aids 2012. 2013 Jun 6; Available from: http://musculoskeletal.cochrane.org/decision-aids.

- 39.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Welch HG. Using a drug facts box to communicate drug benefits and harms: two randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Apr 21;150:516–27. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00106. Epub 2009/02/18. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dulai PS, Siegel CA, Dubinsky MC. Balancing and communicating the risks and benefits of biologics in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013 Dec;19:2927–36. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31829aad16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zikmund-Fisher BJ. The Right Tool Is What They Need, Not What We Have: A Taxonomy of Appropriate Levels of Precision in Patient Risk Communication. Medical Care Research and Review. 2013 Feb 1;70:37S–49S. doi: 10.1177/1077558712458541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards A, Elwyn G. Understanding risk and lessons for clinical risk communication about treatment preferences. Qual Health Care. 2001 Sep;10( Suppl 1):i9–13. doi: 10.1136/qhc.0100009... Epub 2001/09/05. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]