Abstract

Objective

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is a new disorder for DSM-5 that is uncommon and frequently co-occurs with other psychiatric disorders. Here, we test whether meeting diagnostic criteria for this disorder in childhood predicts adult diagnostic and functional outcomes.

Methods

In a prospective, population-based study, subjects were assessed with structured interviews up to 6 times in childhood and adolescence (ages 10 to 16; 5336 observations of 1420 subjects) for symptoms of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and 3 times in young adulthood (ages 19, 21, and 24-26; 3215 observations of 1273 subjects) for psychiatric and functional outcomes (health, risky/illegal behavior, financial/educational and social functioning).

Results

Young adults with a history of childhood disruptive mood dysregulation disorders had elevated rates of anxiety and depression and were more likely to meet criteria for more than one adult disorder as compared to controls with no history of childhood psychiatric problems (noncases) or subjects meeting criteria for psychiatric disorders other than disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in childhood/adolescence (psychiatric controls). Participants with a history of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder also were more likely to have adverse health outcomes, be impoverished, have reported police contact, and have low educational attainment as adults compared to either psychiatric or noncase controls.

Conclusions

The long-term prognosis of children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases is one of pervasive impaired functioning that in many cases is worse than that of other childhood psychiatric cases.

Keywords: Childhood, Irritability, Oppositional Defiant disorder, Mood disorders, DSM-5

Introduction

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder was added to DSM-5 to account for nonepisodic irritability (1) and includes many of the criteria first proposed for severe mood dysregulation (hyperarousal criterion was eliminated and age of onset criteria changed to 10 years old) (2). In a prior study of 3,258 participants covering ages 2 to 17, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder was uncommon and frequently comorbid with other common childhood disorders, most commonly oppositional defiant disorder and depressive disorders (3). In fact, it was rare for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder to occur without comorbid disorder (overlap 63-92%). Given their high levels of mood and behavioral dysregulation and also comorbidity, children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder may be at elevated risk for long–term problems. This paper uses the community-based, longitudinal Great Smoky Mountains study to look at adult psychiatric and functional outcomes of children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

Several community and clinical studies have looked at long-term psychiatric outcomes of irritability (4-6). Brotman and colleagues followed up children with severe mood dysregulation in late adolescence in a community, longitudinal study (4). Children with severe mood dysregulation had seven-fold higher odds of having a depressive disorder than those without severe mood dysregulation. A follow-up of chronically irritable children from another community, longitudinal study found increased risk of major depression in early adulthood (6). This same study looked at outcomes predicted after 20 years of follow-up and found that after adjustment for baseline comorbidities, childhood irritability predicted adult major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety and dysthymia (5). Together, these studies suggest that irritability is a key feature in risk for adult mood, and possibly anxiety, disorders. None of these long-term follow-up studies have, however, applied the new DSM-5 criteria for testing adult outcomes of childhood disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

Psychiatric functioning is only one measure of long-term functioning. Individuals may or may not meet full criteria for an adult psychiatric disorder, but may still fail to attain optimal functioning in important life areas. The developmental literature on severe childhood irritability had previously reported that severely dysregulated children “move against” the world as they grow up—into a spiral of downward mobility, erratic work lives, and dysfunctional relationships(7). Here, we test whether meeting criteria for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in childhood predicts adult health functioning, risky/illegal behaviors, educational/financial and social functioning. Taken together, our goal is to provide a broad psychiatric and functional outcomes profile of young adults with a history of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

The present analyses uses the same sample followed by Brotman and colleagues in their late adolescent follow-up of children with severe mood dysregulation (4). We apply the DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder criteria during childhood and adolescence, and look at adult outcomes at ages 19, 21, and 24-26). In contrast to Brotman and colleagues (4), we excluded the first wave of study from this analysis. We hypothesize that children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder are a severe subset of childhood psychiatric cases and they will display worse psychiatric and functional outcomes than noncases and, in some cases, than psychiatric case controls. Prior work on severe mood dysregulation and chronic irritability suggest that adults with a history of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder may have the highest rates of anxiety and depression in particular.

Methods

Participants

The Great Smoky Mountains Study is a longitudinal, representative study of children in 11 counties of North Carolina (see (8)). Three cohorts of children, ages 9, 11, and 13 years, were recruited from a pool of some 12,000 children using a two-stage sampling design, resulting in N = 1,420 participants (49% female; see also (8)). American Indians were oversampled to constitute 25% of the sample; seven percent of the participants were African American. Annual assessments were completed on the 1420 children until age 16 and then again at ages 19, 21, and 25 for a total of 9941 assessments.

Interviews were completed by a parent figure and the subject to age 16, and by the subject only thereafter. Before all interviews, parent and child signed informed consent/assent forms approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. All interviewers had bachelor's level degrees, received one month of training, and had audio recordings of all interviews reviewed by a senior interviewer.

Childhood/Adolescent Psychiatric status

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder was assessed with the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (9, 10) interview completed with a parent figure and the subject between ages 10 and 16. A symptom was counted as present if parent, child or both endorsed it. To minimize recall bias, the timeframe for determining the presence of psychiatric symptoms was the preceding 3 months. However, because onset dates were collected for all items, the duration criterion could still be calculated.

This study began before disruptive mood dysregulation disorder was proposed, but it was possible to diagnose disruptive mood dysregulation post hoc because its criteria overlap entirely with those of oppositional defiant disorder and depression. Supplemental table 1 provides the specific interview section and items used to assess various criteria. Criteria A to C were defined by items assessing temper outbursts and tantrums as part of the Conduct problems section. If these behaviors were reported, the informant was then queried about the onset of the behavior and frequencies of these behaviors at home, school, and elsewhere which informed criteria E, F and H. Frequency of losing temper in different contexts was not assessed for the first wave of the Great Smoky Mountains study, and so, unlike Brotman and colleagues study (4), this wave was not included in the current analyses . Criterion D was assessed through items about being touchy/easily angered, angry and resentful and irritable from the conduct problems section , and depressed from the depression section. Subjects were required to display these moods on more days than not. Onsets for these items were used for criteria E and H. Criterion G requires a first diagnosis to be made between 7 and 18 years old. Criteria I, J, and K are exclusions based upon other psychiatric disorders or conditions. Criterion I excludes subjects based upon a concurrent manic episode. One individual was excluded due to this criterion (and that subject did not complete an adult assessment). Criterion J would affect results as it involves an exclusion for common psychiatric disorders. This criterion was not applied as we have previously shown that it would exclude many cases (11). Criterion K excludes symptoms due to drugs or medical conditions and this did not affect the number of cases identified. The SAS syntax for this diagnosis is available from the first author by request. Childhood Psychiatric Comorbidities. Diagnostic groups included depressive disorders, anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, and specific phobia), conduct disorder, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and substance disorders. Two-week test-retest reliabilities of interview-derived diagnoses were comparable to those of other structured interviews with kappas ranging from .36 to 1.0 (9, 12).

Adult Psychiatric and Functional outcomes

All outcomes except officially recorded criminal offenses were assessed through interviews with the young adults at ages 19, 21, and 24-26 with the Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment (13)).

Psychiatric status

Scoring programs, written in SAS (14), combined information about the date of onset, duration, and intensity of each symptom to create diagnoses according to the DSM-IV(15). Two-week test-retest reliability of the interview is comparable to that of other highly structured interviews (kappas for individual disorders range from .56 to 1.0) (16). Validity is well-established using multiple indices of construct validity (10). Diagnoses made included any DSM-IV anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety, agoraphobia, panic disorder, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder), depressive disorders (major depression, minor depression, and dysthymia), antisocial personality disorder, alcohol abuse/dependence, and marijuana abuse/dependence. Psychosis was not included in analyses as it was very rare in the community.

Health functioning

Participants reported being diagnosed with a serious physical illness or being in a serious accident at any point during young adulthood or having a sexually transmitted disease (report of testing positive for herpes, genital warts, chlamydia, or HIV). Weight and height measurements were used to derive body mass index with obesity defined as a BMI value greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2. Regular smoking was defined as smoking > 1 cigarette per day for 3 months. Self-reported perceived poor health, high illness contagion risk, and slow illness recovery were derived from a physical health problems survey (Form HIS-1A (1998), US Department of Commerce for the U.S. Public Health Service).

Risky/illegal behaviors

Official felony charges were harvested from North Carolina administrative Offices of the Courts records. Self-report was used to assess recent police contact, often lying to others, frequent physical fighting, breaking into another home/business/property, frequent drunkenness (drinking to excess at least once weekly for 3 months), recent use of marijuana or other illegal substances and one-time sexual encounters with strangers (hooking up with strangers).

Financial/educational functioning

Being impoverished was coded based upon thresholds issued by the Census Bureau based on income and family size (17). High school dropout and completion of any college education were coded based upon the subject’s educational status at the last adult assessment. Job problems were assessed as being dismissed or fired from a job and quitting a job without financial preparations. Finally, other financial problems assessed included: failing to honor debts or financial obligations and being a poor manager of one’s finances.

Social functioning

Marital, parenthood, and divorce status were determined through self-report at the last adult assessment. The quality of the participant’s relationship with their parents, spouse/significant other, and friends was assessed at each assessment including arguments and violence. Variables were included to indicate any violence in a romantic relationship, a poor relationship with one’s parents, no best friend or confidante, and problems making or keeping friends.

Analytic strategy

All analyses compared children that met criteria for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder at some point in childhood and adolescence with two controls groups: those meeting criteria for a psychiatric disorder other than disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in childhood/adolescence (psychiatric controls) and those never meeting criteria for a psychiatric disorder in childhood/adolescence (noncase controls).

All associations with adult outcomes (ages 19 21, and 24-26) were tested using weighted regression models in a generalized estimating equations framework implemented by SAS PROC GENMOD. Robust variance (sandwich type) estimates were used to adjust the standard errors of the parameter estimates for the sampling weights applied to observations.

Results

Descriptive information

Of the total sample of 1420 subjects, 4.1% (unweighted N=80) met criteria for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder at some point in childhood and adolescence between ages 10 and 16. 1273 subjects or 89.7% were followed up in young adulthood. Follow-up rates were similar across diagnostic groups (disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases: 75 of 8 or 93.8%; psychiatric controls: 372 of 419 or 88.8%; non-case controls: 826 of 920 or 89.8%) with no differences between the case group follow-up rate and either other control group (cases vs. psychiatric controls, p = 0.33; cases vs. noncase controls, p = 0.45).

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases did not differ from other groups in the likelihood of being female, white, African American or American Indian (table 1). Participants with a history of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder were more likely to come from impoverished families and singe parent household than noncases, but not psychiatric controls.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and childhood family characteristics

| Noncase controls | Psychiatric controls | DMDD cases | DMDD cases vs. Noncase controls | DMDD cases vs. Psychiatric controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | |

| % female | 51.2 | 40.0 | 50.6 | 1.0 | 0.5-2.2 | 0.95 | 0.7 | 0.3-1.5 | 0.31 |

| % White | 90.2 | 87.2 | 85.4 | 0.6 | 0.2-1.9 | 0.41 | 0.9 | 0.3-2.6 | 0.79 |

| % Black | 6.3 | 8.2 | 11.3 | 1.9 | 0.5-7.3 | 0.36 | 1.4 | 0.4-5.8 | 0.62 |

| % Indian | 3.5 | 4.6 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.5-1.9 | 0.88 | 0.7 | 0.3-1.5 | 0.35 |

| Impoverished families | 28.6 | 50.2 | 63.1 | 4.3 | 2.0-9.3 | <0.001 | 1.7 | 0.8-3.8 | 0.20 |

| Single parent | 31.1 | 47.4 | 56.5 | 2.9 | 1.3-6.3 | 0.01 | 1.4 | 0.6-3.3 | 0.39 |

DMDD= disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Bolded p values are significant at p <0.05.

Childhood disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and Adult Diagnostic Outcomes

Table 2 compares the childhood diagnostic groups on rates of adult psychiatric diagnoses. Each association was tested with weighted logistic regression models and associations are reported as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and associated p values. Cases with childhood disruptive mood dysregulation disorder were significantly more likely to meet criteria for an adult diagnosis than noncase controls. Specifically, they were more likely to have an adult depressive or anxiety disorder. They were also more likely to meet criteria for adult anxiety or depression compared to psychiatric controls. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases were most likely to meet criteria for multiple adult disorders, with 10.3 greater odds compared to those with noncase controls and 5.9 greater odds than psychiatric controls. They were not at elevated risk for adult substance-related disorders.

Table 2.

Associations of childhood/adolescent diagnostic groups with young adult diagnostic categories

| Noncase controls | Psychiatric controls | DMDD cases | DMDD cases vs. Noncase controls | DMDD cases vs. Psychiatric controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | |

| Any | 24.6 | 49.2 | 56.6 | 4.0 | (1.8-9.0) | <0.001 | 1.4 | (0.6-3.2) | 0.49 |

| Depressive | 4.3 | 6.7 | 24.9 | 7.4 | (2.3-23.3) | <0.001 | 4.6 | (1.4-14.9) | 0.01 |

| Anxiety | 7.4 | 20.7 | 45.4 | 10.4 | (4.2-26.0) | <0.001 | 3.2 | (1.3-8.1) | 0.02 |

| ASPD | 1.9 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 0.9 | (0.2-4.7) | 0.87 | 0.5 | (0.1-3.0) | 0.46 |

| Alcohol | 14.9 | 25.2 | 19.7 | 1.4 | (0.5-3.7) | 0.50 | 0.7 | (0.3-2.0) | 0.54 |

| THC | 14.1 | 21.1 | 29.5 | 2.6 | (1.0-6.4) | 0.05 | 1.6 | (0.6-4.1) | 0.37 |

| 2+ disorders | 5.2 | 8.8 | 36.1 | 10.3 | (3.8-28.4) | <0.001 | 5.9 | (2.1-16.6) | <0.001 |

DMDD= disruptive mood dysregulation disorder; ASPD = Antisocial Personality Disorder; THC = marijuana-related disorders. Bolded p values are significant at p <0.05.

Childhood disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and adult functional outcomes

Health Functioning and Risky/Illegal behaviors

Table 3 shows rates of adult health outcomes and risky/illegal behaviors in childhood disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases, psychiatric cases, and noncase controls. As compared to noncase controls, those with a history of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder had worse health outcomes in adulthood (elevated on 4 of 8 indicators) with high rates of sexually transmitted diseases, regular smoking, self-reported and illness contagion. Cases were less likely to have been diagnosed with a serious illness than noncase controls. Compared to psychiatric controls, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases had higher rates of adult sexually transmitted diseases and lower rates of serious illnesses.

Table 3.

Associations between disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in childhood and young adult health functioning and risky/illegal behaviors

| Noncase controls | Psychiat ric controls | DMDD cases | DMDD cases vs. Noncase controls | DMDD cases vs. Psychiatric controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | OR | (95%CI) | p value | OR | (95%CI) | p value | |

| Health Outcomes | |||||||||

| Serious Illness | 5.6 | 7.0 | 1.3 | 0.2 | (0.1-0.9) | 0.04 | 0.2 | (0.0-0.8) | 0.03 |

| Serious Accident | 13.8 | 10.8 | 15.2 | 1.1 | (0.4 -3.0) | 0.82 | 1.5 | (0.5-4.3) | 0.46 |

| Sexually transmitted disease | 4.5 | 4.4 | 21.9 | 5.9 | (1.9-18.1) | 0.002 | 6.0 | (1.9-19.7) | 0.003 |

| Obesity | 25.2 | 35.7 | 28.2 | 1.2 | (0.5-2.6) | 0.71 | 0.7 | (0.3-1.7) | 0.43 |

| Any non-substance psychiatric disorder | 15.9 | 33.0 | 54.1 | 6.2 | (2.7-14.2) | <0.001 | 2.4 | (1.0-5.7) | 0.04 |

| Regular smoking (>1day) | 37.1 | 57.7 | 75.0 | 5.1 | (2.2-11.8) | <0.001 | 2.2 | (0.9-5.4) | 0.08 |

| Self-report of poor health | 15.7 | 26.5 | 37.6 | 3.2 | (1.3-8.1) | 0.01 | 1.7 | (0.6-4.4) | 0.30 |

| Self-report of illness contagion | 21.7 | 34.5 | 45.0 | 3.0 | (1.3-6.9) | 0.01 | 1.6 | (0.6-3.8) | 0.34 |

| Risky/Illegal behaviors | |||||||||

| Official felony charge | 6.1 | 11.3 | 20.3 | 4.0 | (1.3-12.1) | 0.02 | 2.0 | (0.7-6.1) | 0.23 |

| Police contact | 9.5 | 18.4 | 30.5 | 5.9 | (2.1-16.5) | 0.001 | 3.7 | (1.4-10.3) | 0.01 |

| Lying | 3.6 | 6.4 | 1.7 | 0.5 | (0.1-2.2) | 0.32 | 0.3 | (0.1-1.2) | 0.09 |

| Physical fighting | 5.9 | 8.9 | 26.8 | 4.2 | (1.5-11.5) | 0.005 | 2.0 | (0.7-5.6) | 0.21 |

| Breaking in | 1.7 | 11.2 | 18.9 | 13.7 | (3.6-52.2) | <0.001 | 1.8 | (0.5-6.9) | 0.37 |

| Driving when impaired | 6.8 | 14.2 | 13.2 | 2.1 | (0.6-7.6) | 0.27 | 0.9 | (0.2-3.5) | 0.90 |

| Marijuana use | 28.8 | 44.6 | 39.0 | 1.6 | (0.7-3.7) | 0.29 | 0.8 | (0.3-1.9) | 0.61 |

| Other illicit drug use | 8.1 | 15.9 | 9.0 | 1.1 | (0.5-2.6) | 0.76 | 0.5 | (0.2-1.2) | 0.14 |

| Hooking up with stranger | 12.9 | 18.3 | 16.3 | 1.3 | (0.5-3.9) | 0.61 | 0.9 | (0.3-2.7) | 0.81 |

DMDD= disruptive mood dysregulation disorder; OR = odds ratio; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval. Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05.

Children with a history of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder were also at elevated risk for risky/illegal behaviors (4 of 9 indicators) as compared to non-cases. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder had higher rates of having an official felony charges, self-reported police contact, physical fighting and breaking into buildings illegally compared to noncase controls. Similar to the findings for substance-related diagnostic outcomes, cases did not have elevated rates of illicit drug use. , There was little evidence of difference with psychiatric controls for risky/illegal behaviors (elevated on 1 of 9 indicators) Add Table 4 about here

Table 4.

Associations between disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in childhood and young adult financial and social functioning

| Noncase controls | Psychiatric controls | DMDD cases | DMDD cases vs. Noncase controls | DMDD cases vs. controls Psychiatric | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial/ educational functioning | % | % | % | OR | (95%CI) | p value | OR | (95%CI) | p value |

| Impoverished | 56.9 | 68.0 | 86.3 | 4.8 | (2.4-9.5) | <0.00 | 3.0 | (1.4-6.3) | 0.005 |

| No high school diploma | 18.5 | 22.9 | 40.9 | 3.0 | (1.3-6.9) | 0.008 | 2.3 | (1.0-5.5) | 0.05 |

| No college | 42.4 | 62.4 | 82.3 | 6.3 | (2.5-16.2) | <0.00 | 2.8 | (1.1-7.5) | 0.04 |

| Dismissed from a job | 21.1 | 39.3 | 37.7 | 2.3 | (1.0-4.9) | 0.04 | 0.9 | (0.4-2.1) | 0.87 |

| Quit multiple jobs | 10.7 | 25.0 | 27.8 | 3.2 | (1.4-7.5) | 0.007 | 1.2 | (0.5-2.8) | 0.74 |

| Failing to honor financial obligations | 10.3 | 22.7 | 8.5 | 0.8 | (0.4-1.8) | 0.62 | 0.3 | (0.1-0.8) | 0.009 |

| Poor financial management | 7.7 | 17.0 | 10.2 | 1.4 | (0.6-3.0) | 0.46 | 0.56 | (0.2-1.3) | 0.18 |

| Social functioning | |||||||||

| Violent relationships | 3.2 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 5.4 | (1.6-18.8) | 0.007 | 1.6 | (0.5-5.5) | 0.45 |

| Poor relationship with parents | 16.1 | 30.2 | 37.2 | 3.1 | (1.1-8.5) | 0.03 | 1.4 | (0.5-3.9) | 0.55 |

| No best friend/confidante | 21.7 | 36.6 | 41.1 | 2.5 | (1.1-5.8) | 0.03 | 1.2 | (0.5-2.9) | 0.68 |

| Problems making/keeping friends | 3.8 | 9.8 | 7.6 | 2.1 | (0.8-5.4) | 0.13 | 0.8 | (0.3-2.1) | 0.59 |

DMDD= disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. OR = odds ratio; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval. Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05.

Financial/educational and Social Outcomes

Associations were also tested with adult financial/educational and social outcomes (table 4). Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases had elevated rates on 5 of 7 financial/educational indicators as compared to noncase controls. Those with a history of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder were more likely to be impoverished and have troubles keeping a job and less likely to have graduated from high school or completed any college than noncase controls. Disruptive behavior mood disorder cases were also more likely to be impoverished and have lower educational attainment as compared to psychiatric controls. Adult social functioning was disrupted as compared to noncases (violent relationships, poor parental relations, and no best friend) but not as compared to psychiatric controls.

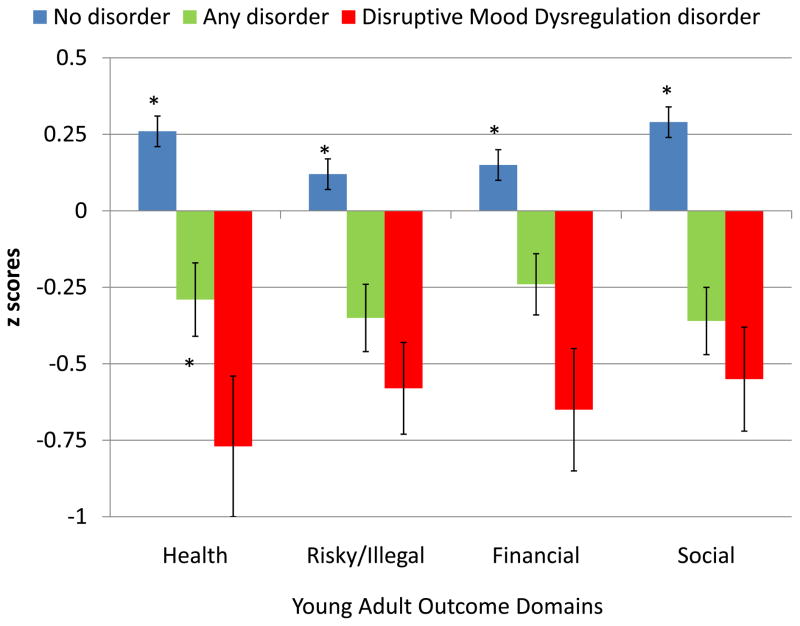

Comparisons across summary Functional Outcome scales

Indicators of adult outcomes were summed within each functional domain (health, risky/illegal behaviors, wealth: financial/educational, and social functioning) and these scales were standardized (Mean: 0; SD: 1; i.e. the mean of 0 indicates the mean problems for each domain in the total sample). Figure 1 displays z scores for each of the four outcome domains for all groups. Across all domains, positive scores indicate fewer problems and negative scores indicate more problems. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases were elevated across all domains as compared to noncases and had worse health functioning than the other psychiatric cases groups. In all cases, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases had the lowest standardized scores indicating more indicators of poor functioning.

Figure 1.

Means values and standard errors for adult standardized outcome scales by childhood diagnostic status (negative scores indicate more problems than the mean for the total sample). Asterisks indicate whether the control group was statistically different from disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases (p<.05). Children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder had worse health outcomes than noncases (MR=2.8; 95% CI=1.8-2.1, p<0.001), but also psychiatric controls (MR=1.6; 95% CI=1.0-2.5, p=0.04). Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases had higher levels of all other outcomes compared to noncase controls (risky/illegal MR=2.0; 95% CI=1.1-3.6, p=0.02; financial/educational MR=2.3; 95% CI=1.6-3.3, p<0.001; and social MR=2.2; 95% CI=1.5-3.3, p<0.001). As compared to psychiatric controls, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases did not have worse risky/illegal behavior outcomes (MR=1.2; 95% CI=0.7-2.3, p=0.45) or financial/educational outcomes (MR=1.2; 95% CI=0.8-1.8, p=0.34), but had marginally worse social outcomes (MR=1.5; 95% CI=1.0-2.3, p=0.06).

A follow-up analysis comparing disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases to psychiatric controls that had met criteria for more than one diagnosis in childhood (comorbidity controls) and found no significant differences on any functional scale, although disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases always had the lowest means scores (i.e., more problems).

Discussion

Irritability is a symptom or associated feature of many psychiatric disorders, but it is a core feature of DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. As such, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is a distinctive disorder in terms of its high rates of associated comorbidity (11). Our study suggests that this pattern of comorbidity extends to adulthood where subjects displayed rates of comorbidity 5 to 7 times higher than those observed for noncase controls and psychiatric controls and were at increased risk for both anxiety and depressive disorders. The poor prognosis for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases also extended to health, legal, financial/educational, and social functioning. Indeed, the composite profile of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases in adulthood is one of pervasive, impaired functioning.

Children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder were worse off in adulthood than children with other psychiatric problems in a number of domains (depression, anxiety, psychiatric comorbidity, poverty, and low educational attainment). One possible explanation of this finding is that the severity of psychiatric symptoms is higher in children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder compared to children with other common psychiatric disorders. It is also possible that this increased risk might be attributable to its high levels of comorbidity. These two interpretations are not exclusive. Indeed, in our sample, there were so few cases of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder without a comorbid disorder that we could not test whether severity and comorbidity differentially contributed to adult outcomes. When we compared cases to psychiatric controls with multiple childhood disorders, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder cases had lower scores in all functional domains (i.e., worse functioning), but these differences were not statistically significant. We conclude that disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is a severe, highly comorbid childhood disorder that marks children at risk for long-term impaired functioning.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder has proven to be controversial. Concerns include the potential for increased psychotropic medication use in children, pathologizing of “normal” tantrum behavior, and the lack of any empirical basis (18-21). This analysis and previous work (11) suggests that the concern about pathologizing normal behavior is likely overstated: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is relatively rare, almost always comorbid, and commonly associated with long-term impairment. These children should be a clinical priority. The risk of increased medication use (or psychotherapy) depends upon what clinical trials suggest about the optimal treatment strategy and long-term outcomes of treatment for such children. Finally, the concerns about the lack of empirical basis are being addressed rapidly with basic epidemiological studies available prior to the publication of DSM-5 and also with extensive prior study of severe mood dysregulation and chronic irritability (4-6, 11, 22, 23).

One critique of this new disorder that has empirical support is that disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is merely a new category for children with comorbid depression and oppositional defiant disorder (11). The reason that disruptive mood dysregulation disorder can be studied in existing samples is that the criteria can be almost entirely derived from the symptomatic criteria for those two disorders (i.e., persistent irritable/angry affect punctuated by temper outbursts). Is it, therefore, necessary to propose a new category or is it sufficient to note this comorbidity group as one of interest? This may be a reasonable taxonomic issue, but another validity criterion is how the diagnosis entity informs prognosis and treatment planning. Our findings suggest that this disorder identifies children which in some cases may have a worse prognosis than children with other common psychiatric disorders.

It is important to note several potential limitations. The GSMS is not nationally representative; compared to the US population, GSMS over-represents American Indians and under-represents Blacks. Rates of poverty in children that have participated in GSMS are slightly higher than is found in the US in similar age cohorts. Despite these caveats, prevalence rates for common disorders and comorbidity patterns derived from these studies are similar to those from other community epidemiologic studies (24-26). To date, there is no nationally-representative longitudinal study of childhood mental health that has used gold standard psychiatric interviews. Thus, geographically limited epidemiologic, longitudinal studies like this one have been an important source of information on the etiology, phenomenology, and developmental course of childhood psychopathology.

The study attempted to minimize recall biases and forgetting by focusing interviews on the three months immediately preceding the interview. At the same time, individuals may have met criteria for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder outside of our assessment window. To the extent that cases were not identified, our results underestimate the long-term effect of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Finally, the diagnostic criteria were applied post hoc using symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder and depressive disorders as the diagnosis had not been proposed at the time of the interviews. As such, additional information about this particular constellation of symptoms, apart from oppositional defiant disorder and depressive disorders (e.g., impairments, service use) was not collected.

Conclusion

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is a new disorder to our DSM, and there is no question that research on irritability has increased dramatically over the last decade, but children with this constellation of symptoms have always been with us (27). Caspi and colleagues described children with high levels of temper tantrums as ‘moving against the world’ and documented their downward social mobility and turbulent social lives (7). Our analysis suggests that this bleak prognosis includes increased health problems, continued emotional distress, financial strain, and social isolation. For most, development provides a constant series of opportunities for recovery and rehabilitation (28), but for children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, the accumulation of early failures may perpetuate a lifetime of limited opportunity and compromised well-being. As such, children with persistent irritable mood punctuated by frequent outburst - regardless of what we call this cluster of symptoms – should be a priority for clinical care and for treatment development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work presented here was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH080230, MH63970, MH63671, MH48085, MH075766), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA/MH11301, DA011301, DA016977, DA011301), NARSAD (Early Career Award to WEC), and the William T Grant Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

None of the authors has biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Lilly Shanahan, Email: lilly_shanahan@unc.edu.

Helen Egger, Email: helen.egger@dm.duke.edu.

Adrian Angold, Email: aangold@psych.duhs.duke.edu.

E. Jane Costello, Email: elizabeth.costello@duke.edu.

References

- 1.DSM-5 Childhood and Adolescent Disorders Work Group. Justification for Temper Dysregulation Disorder with Dysphoria. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leibenluft E, Charney DS, Towbin KE, Bhangoo RK, Pine DS. Defining clinical phenotypes of juvenile mania. The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160(3):430–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Copeland W, Angold A, Costello E, Egger H. Prevalence, Comorbidity and Correlates of DSM-5 Proposed Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder. American Joural of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brotman MA, Schmajuk M, Rich BA, Dickstein DP, Guyer AE, Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Prevalence, Clinical Correlates, and Longitudinal Course of Severe Mood Dysregulation in Children. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(9):991–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Adult Outcomes of Youth Irritability: A 20-Year Prospective Community-Based Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1048–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leibenluft E, Cohen P, Gorrindo T, Brook JS, Pine DS. Chronic Versus Episodic Irritability in Youth: ACommunity-Based, Longitudinal Study of Clinical and Diagnostic Associations. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2006;16(4):456–66. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caspi A, Elder G, Jr, Bern D. Moving against the world: Life-course patterns of explosive children. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:308–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angold A, Prendergast M, Cox A, Harrington R, Simonoff E, Rutter M. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:739–53. doi: 10.1017/s003329170003498x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angold A, Costello E. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ, Egger H. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):173–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter B, Angold A. The test-retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(5):538–49. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angold A, Erkanli A, Copeland W, Goodman R, Fisher PW, Costello EJ. Psychiatric Diagnostic Interviews for Children and Adolescents: A Comparative Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(5):506–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® Software: Version 9. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angold A, Costello EJ. A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA-C) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:755–62. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalaker J, Naifah M. Poverty in the United States: 1997. US Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports: Consumer Income. 1993:60–201. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parens E, Johnston J, Carlson GA. Pediatric Mental Health Care Dysfunction Disorder? New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(20):1853–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1003175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Axelson D, Birmahe B, Findling R, Fristad M, Kowatch R, Youngstrom E, Arnold E, Goldstein B, Goldstein T, Chang K, Delbello M, Ryan N, Diler R. Concerns regarding the inclusion of temper dysregulation disorder with dysphoria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1257–62. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10com06220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stringaris A. Irritability in children and adolescents: a challenge for DSM-5. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;20(2):61–6. doi: 10.1007/s00787-010-0150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor E. Child Psychology and Psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011. Diagnostic Classification: Current Dilemmas and Possible Solutions; pp. 223–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stringaris A, Zavos H, Leibenluft E, Maughan B, Ele T. Adolescent irritability: phenotypic associations and genetic links with depressed mood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):47–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. American Joural of Psychiatry. 2010;168(2):129–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffee S, Harrington H, Cohen P, Moffitt TE. Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorder in youth. Journal of the American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(5):406–7. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000155317.38265.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Slever LJ, Shinaato L. The prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorder in a community-based survey of adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1237–43. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen P, Cohen J, Kasen S, Velez CN, Hartmark C, Johnson J, Rojas M, Brook J, Streuning EL. An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence: 1. Age- and gender-specific prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1993;34:851–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutter M, Lebovici S, Eisenberg L, Sneznevskij AV, Sadoun R, Brooke E, Lin TY. A triaxial classification of mental disorders in childhood: An international study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1969;10:41–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1969.tb02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Copeland W, Shanahan L, Miller S, Costello EJ, Angold A, Maughan B. Outcomes of Early Pubertal Timing in Young Women: A Prospective Population-Based Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(10):1218–25. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.