Abstract

Trehalose, a naturally occurring non-reducing disaccharide, is known to act as a major protein stabilizer that can reduce ultraviolet B (UVB)-induced corneal damage when topically applied to the eye. However, due to the low skin permeability of trehalose, which makes the development of topical formulations difficult, its use as a skin photoprotective agent has been limited. Previous findings demonstrated that liposomes may significantly improve the intracellular delivery of trehalose. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess the protective effects of trehalose-loaded liposomes against UVB-induced photodamage using the immortalized human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT. The effects were also compared to those of the common skin photoprotective compounds, including L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol. The levels of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine and protein carbonylation in HaCaT cells were used as biological markers of UVB-induced damage. Compared to other compounds, trehalose-loaded liposomes showed the highest efficacy in reducing the levels of the three markers following UVB irradiation of HaCaT cells (all P<0.001 when compared to each of the four other photoprotective compounds). Therefore, these findings indicate that there may be a clinical application for trehalose-loaded liposomes, and further studies should be performed to assess the potential usefulness in skin photoprotection and the prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer.

Keywords: ultraviolet radiation, keratinocytes, trehalose, cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, protein carbonylation

Introduction

Recent lifestyle changes involving prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiations (including increased outdoor activity or use of tanning beds) and a history of excessive UV exposure that is associated with aging have been advocated to explain the increasing incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) worldwide (1). The biological effects of UV radiation are strictly correlated to their wavelengths (1). Accordingly, the UV spectrum is subdivided into three distinct wavelength regions: UVA (320–400 nm), UVB (290–320 nm) and UVC (200–290 nm) (2,3). Although ~95% of the UVB radiation emitted by the sun is absorbed by the Earth’s ozone layer, animal models have shown that UVB exposition is linked to a higher NMSC risk compared to UVA (4). The latter phenomenon is attributed to the fact that UVB is principally absorbed in the epidermis, whereas UVA can reach the dermis (5). Additionally, the shorter wavelengths of UVB have been found to produce more alterations in the main biological macromolecules (DNA and proteins) compared to the longer wavelengths of UVA (6). Notably, UVB radiation, in contrast to UVA, is known to cause direct DNA damage, mainly in the form of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPD) and 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG), which are the main genetic markers for UVB-induced mutagenesis (7–10).

Although traditional physical and chemical sunscreens remain the mainstay approach to reduce the adverse oncogenic potential of UVB radiations, total protection against the entire spectrum of molecular lesions associated with UVB exposure cannot be ensured (11). Therefore, the identification of novel strategies aimed at reducing UVB-induced damage in human keratinocytes has been previously studied (12–14). Several antioxidants and cytoprotective compounds, including L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol, have been shown to reduce UV-induced injury in experimental and animal models (15–18). In contrast to the DNA alterations that may lead to NMSC-related mutations, growing evidence indicates that UVB radiation can induce protein carbonylation (PC), a major form of oxidative protein damage that has been recently proposed as a critical molecular signature of skin carcinogenesis (19). Notably, altered protein function caused by PC may have a detrimental impact on cellular signaling and activate the target genes that promote survival, progression and metastasis (20).

Trehalose, a naturally occurring non-reducing disaccharide consisting of two glucose units, is found in a large variety of organisms, including bacteria, fungi and invertebrate animals, where it may serve as a stress protectant or resilience factor (21,22). Extremophile bacteria have the ability to achieve a significant UV-radiation resistance via simple non-enzymatic antioxidant mechanisms consisting of trehalose complexed with manganese ions (22). Trehalose is known to act as a major protein stabilizer and its topical application to the eye reduces UVB-induced corneal damage (19). However, the use of trehalose as a skin photoprotective agent is limited due its low skin permeability, which makes the development of topical formulations difficult. A previous study has demonstrated that liposomes can markedly increase the intracellular delivery of trehalose (23). Thus, the aim of the present study was to assess the protective effects of trehalose-loaded liposomes against UVB irradiation-induced injury using the immortalized human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT. The effect of this compound was compared to other commonly used photoprotective agents, including L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol.

Materials and methods

Materials

L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and prepared as fresh 100-μM stock solutions in phosphate-buffered saline (adjusted to 7.4 pH), filter-sterilized and stored at 4°C for ≤12 h.

Production of trehalose-loaded liposomes

Trehalose was purchased from Hayashibara Co., Ltd. (Okayama, Japan). Unilamellar negatively-charged trehalose-containing liposomes were synthesized using an extrusion procedure, as previously described (23). Briefly, the liposome-lipid bilayer consisted of 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL, USA), phosphatidylserine (PS; Sigma-Aldrich) and cholesterol (Avanti Polar Lipids) in a 60:10:30 % mol ratio, resulting in a 25-mM final lipid solution. Following lyophilization, the DPPC:PS:cholesterol lipid film was hydrated with trehalose buffer [300 mM α-d-glucopyranosyl-α-d-glucopyranoside, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 307 mOsm; Sigma-Aldrich] to produce negatively-charged liposomes. Liposomal trehalose was suspended in sterile 0.9% NaCl at 65°C to yield a 100-μM stock solution.

HaCaT cell culture, pretreatment and irradiation

HaCaT cells, an immortalized, non-tumorigenic human keratinocyte cell line, were purchased from Cell Lines Service (Eppelheim, Germany) and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotics at standard cell culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator). The cells were cultured until 80% confluent and pretreated with 100 μM of each stock solution [trehalose-containing liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol] for 24 h before UVB irradiation. Exposure to UVB was performed using a Spectrolinker XL-1500 UV crosslinker (Spectronics Corporation, Westbury, NY, USA), which emits the majority of its energy within the UVB range (280–320 nm), peaking at 312 nm. The intensity of UVB radiation was measured using a phototherapy radiometer (International Light Technologies, Newburyport, MA, USA). The cells were exposed to UVB radiation at a dose of 20 mJ/cm2. Following UVB radiation, cells were incubated in fresh medium in the absence of any compounds until analysis. The cells that were exposed to UVB radiation without any pretreatment were used as positive controls, whereas the cells that received no pretreatment and were not exposed to UVB irradiation served as negative controls.

Quantification of CPD, 8OHdG and PC in HaCaT extracts

Approximately 3×106 cells were lysed using 200 μl lysis buffer and were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min. PC in cell lysates was measured by OxiSelect™ Protein Carbonyl ELISA kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the CPD and 8OHdG measurements, the samples were digested for 12 h at 60°C with proteinase K in 100 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/l NaCl and 10 mmol/l EDTA (pH 8.0). Proteinase K was subsequently heat-inactivated at 95°C for 10 min and homogenates were extracted using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). The kit contains two main reagents, which are the cell lysis and protein precipitation solutions. Briefly, DNA was extracted from homogenates using a lysis-buffer solution and treated with RNase A. The kit removes proteins using a precipitation solution, followed by 2-propanol to pellet the DNA. CPD and 8OHdG were measured in duplicate and in a random order by specific ELISA kits [OxiSelect Cellular UV-Induced DNA Damage ELISA kit (CPD), 96 assays (Cell Biolabs, Inc.) and OxiSelect™ Oxidative DNA Damage ELISA kit (8OHdG quantitation, Cell Biolabs, Inc.)] according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results of CPD, 8OHdG and PC measurements are presented as arbitrary units (such as relative amount of absorbance in ELISA relative to the untreated control, which was set as 1 by convention). All the analyses were conducted whilst blinded to the irradiation protocol.

Statistical analysis

All the data were from at least three independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The comparisons of the biomarkers among the various experimental conditions [positive controls (no pretreatment) or pretreatment with trehalose-loaded liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid or DL-α-tocopherol] were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to detect whether a group (pretreatment) effect existed, followed by Tukey’s test for post hoc pairwise comparisons. All the calculations were performed using SPSS, version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism, version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical analysis was two-tailed and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Analysis of the UVB-induced biomarker changes

Following UVB irradiation, the levels of CPD, 8OHdG and PC were significantly increased (by 27.5-, 8.1- and 7.2-fold, respectively; Table I) in positive-control HaCaT cells compared to non-irradiated negative-control cells (all P<0.001). To investigate whether pretreatment with trehalose-loaded liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol could inhibit UVB-induced DNA and protein damage in cultured keratinocytes, CPD, 8OHdG and PC were measured in HaCaT cells pretreated with fresh 100-μM stock solutions for each compound prior to exposure to UVB light.

Table I.

Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPD), 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG) and protein carbonylation (PC) in human HaCaT cells under different experimental conditions.

| Negative control | Positive control | Trehalose-loaded liposomes | L-carnosine | L-(+)-ergothioneine | L-ascorbic acid | DL-α-tocopherol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPD | 1 | 27.5±0.6 | 6.1±0.3 | 12.1±1.3 | 8.4±1.2 | 15.3±1.4 | 12.6±0.5 |

| 8OHdG | 1 | 8.1±0.6 | 3.6±0.1 | 5.2±0.3 | 4.7±0.2 | 6.1±0.2 | 6.0±0.4 |

| PC | 1 | 7.2±0.2 | 2.1±0.1 | 4.7±0.1 | 4.3±0.2 | 5.5±0.3 | 4.9±0.2 |

Data are means ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. The negative control cells were set at 1.

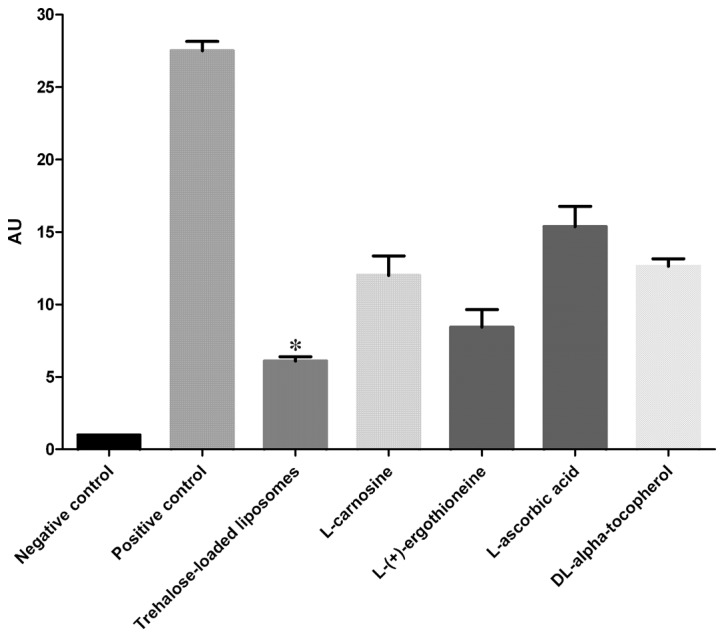

CPD

The protective effects of trehalose-loaded liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol against CPD formation in UVB-irradiated HaCaT cells are shown in Fig. 1. The ANOVA tests showed a significant pretreatment effect (P<0.001). In post hoc analyses, all the tested compounds were able to reduce the formation of CPD in UVB-irradiated cells compared to the positive controls (all P<0.001). Post hoc analyses also revealed that trehalose-loaded liposomes and L-(+)-ergothioneine were significantly more effective in inhibiting CPD formation compared to the other compounds (all P<0.001). Notably, trehalose-loaded liposomes were significantly more effective than L-(+)-ergothioneine (P<0.05; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of trehalose-loaded liposomes on ultraviolet B (UVB)-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer formation in HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were cultured to 80% confluence and then pretreated with 100 μM of each stock solution [trehalose-containing liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol] for 24 h. HaCaT cells were subsequently exposed to 20 mJ/cm2. The positive control cells received UVB radiation without any pretreatment. The cells that received no pretreatment and were not exposed to UVB irradiation served as negative controls. Data represents the mean ± 1 SD from at least three independent experiments. Trehalose-loaded liposomes and L-(+)-ergothioneine were significantly more effective in inhibiting CPD formation compared to the other compounds (all P<0.001). Notably, trehalose-loaded liposomes were significantly more effective than L-(+)-ergothioneine (*P<0.05). AU, arbitrary units.

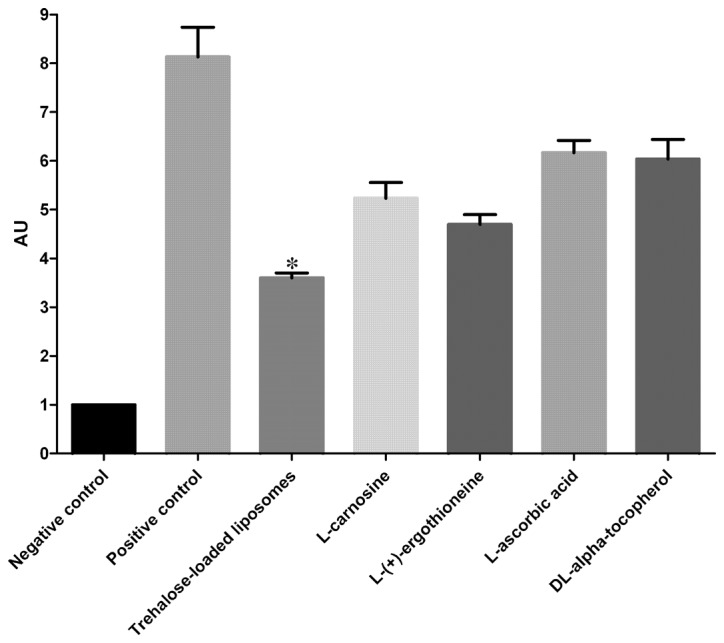

8OHdG

The effects of trehalose-loaded liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol in inhibiting 8OHdG formation in UVB-irradiated HaCaT cells are shown in Fig. 2. The ANOVA tests showed a significant pretreatment effect (P<0.001). In post hoc analyses, all the tested compounds were able to significantly reduce the formation of CPD in UVB-irradiated cells compared to the positive controls (P<0.001). Notably, trehalose-loaded liposomes were significantly more effective in inhibiting 8OHdG formation compared to the other tested compounds (all P<0.001; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of trehalose-loaded liposomes on ultraviolet B (UVB)-induced 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine formation in HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were cultured to 80% confluence and pretreated with 100 μM of each stock solution [trehalose-containing liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol] for 24 h. HaCaT cells were subsequently exposed to 20 mJ/cm2. The positive control cells received UVB radiation without any pretreatment. The cells that did not receive any form of pretreatment or UVB irradiation served as negative controls. Data represents the mean ± 1 SD from at least three independent experiments. Trehalose-loaded liposomes were significantly more effective in inhibiting 8OHdG formation compared to the other tested compounds (all *P<0.001). AU, arbitrary units.

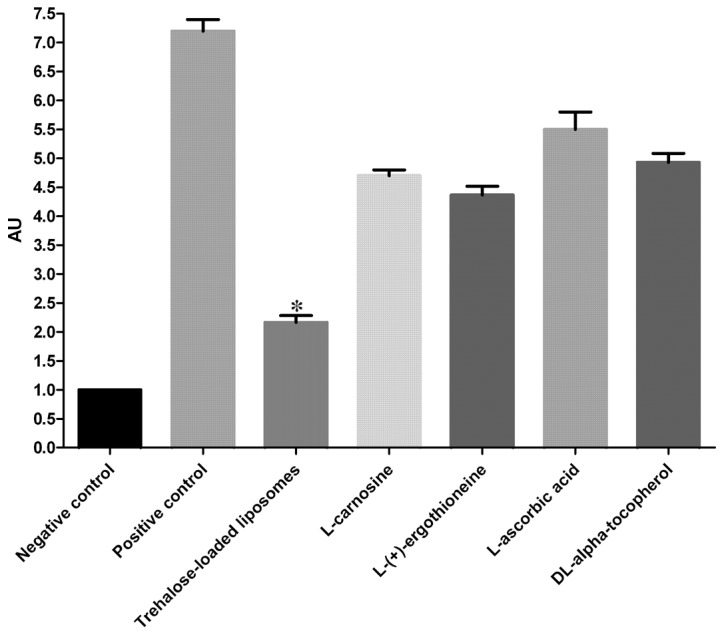

PC

The protective effects of trehalose-loaded liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol against the development of PC in UVB-irradiated HaCaT cells are shown in Fig. 3. The ANOVA tests showed a significant pretreatment effect (P<0.001). In post hoc analyses, all the tested compounds were able to significantly reduce PC in UVB-irradiated cells compared to the positive controls (all P<0.001). In particular, the results revealed that trehalose-loaded liposomes were significantly more effective in inhibiting PC compared to the other tested compounds (all P<0.001; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of trehalose-loaded liposomes on ultraviolet B (UVB)-induced protein carbonylation in HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were cultured to 80% confluence and pretreated with 100 μM of each stock solution [trehalose-containing liposomes, L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol] for 24 h. HaCaT cells were subsequently exposed to 20 mJ/cm2. The positive control cells received UVB radiation without any pretreatment. The cells that did not receive any form of pretreatment or UVB irradiation served as negative controls. Data represents the mean ± 1 SD from at least three independent experiments. Trehalose-loaded liposomes were significantly more effective in inhibiting PC compared to the other tested compounds (all *P<0.001). AU, arbitrary units.

Discussion

There is a high demand for novel and effective strategies aimed at reducing photodamage and the increasing problems associated with human skin cancer. UVB radiation is known to play a major role in the pathogenesis of NMSC (4), owing to its ability to cause direct and indirect DNA damage (mainly in the form of inducing CPD and 8OHdG) (7–10). In addition, growing evidence indicates that UVB may induce widespread protein oxidation, which can ultimately impair a number of intracellular enzymatic activities (including endogenous DNA repair enzymes) (19,24). Although trehalose has been shown to reduce UVB-induced corneal damage when applied topically to the eye (19), its use as a skin photoprotective agent has been limited by its poor permeability (25), which was improved in the present study by loading liposomes. Notably, the main results of the study indicate that, compared to other common photoprotective compounds, trehalose-loaded liposomes showed the highest efficacy in reducing the levels of the three UVB-associated markers following experimental irradiation of HaCaT cells.

Several natural antioxidants have been tested for their ability to prevent UVB-induced damage to biological macromolecules (26). Among them, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol have been extensively studied. Specifically, L-ascorbic acid has been shown to reduce UV-induced photodamage in a porcine skin model (27) and human cells (28). Notably, Lin et al have developed a topical formulation consisting of 15% L-ascorbic acid combined with 1% DL-α-tocopherol (17). When DL-α-tocopherol neutralizes oxidative stress in lipids, its oxidation product can be regenerated by L-ascorbic acid (28–36). L-(+)-ergothioneine is a potent, natural sulfur-containing antioxidant that can protect biological macromolecules against copper-dependent oxidative damage (37) and enhance DNA repair in UV-irradiated cells (38). Similarly, L-carnosine, a naturally occurring histidine-containing dipeptide with antioxidant properties, has been shown to provide protection against UVB radiation, possibly via immunological mechanisms (39).

The results of the present study clearly confirm that L-carnosine, L-(+)-ergothioneine, L-ascorbic acid and DL-α-tocopherol can significantly prevent experimentally-induced photodamage. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, the findings demonstrate for the first time that trehalose-loaded liposomes had a significantly improved performance when compared to the other common cytoprotective compounds in reducing UVB-induced molecular damage in a human keratinocytes cell line. The noteworthy capacity of trehalose-loaded liposomes in preventing the formation of UVB-associated molecular signatures at the DNA (CPD, 8OHdG) and protein levels (PC) may be due to the ability of liposomes to effectively cross the keratinocyte membrane and increase intracellular trehalose concentrations. In turn, intracellular trehalose may decrease PC by stabilizing proteins and acting as a molecular chaperone (21). In this regard, it is noteworthy that extremophilic bacteria, which are characterized by the ability to resist large amounts of UV radiation, have high intracellular levels of trehalose combined with manganese ions (19,22). The in vitro results of the present study also showed that trehalose may reduce UVB-induced DNA damage to a greater extent than other cytoprotective molecules. These findings indicate the possibility that trehalose can exert a strong influence on DNA repair by collectively preserving the function of endogenous DNA repair enzymes and other molecular chaperones. Thus, the results suggest that at least part of the trehalose-mediated effect on DNA markers is mediated by a ‘proteome effect’, in which trehalose protects a number of protein functions simulaneously (including those of DNA repair enzymes) rather than by a direct genoprotective effect (40). Further biochemical studies are required to extensively test this hypothesis.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that trehalose-loaded liposomes have a marked ability in reducing the levels of UVB-associated molecular signatures following experimental irradiation of human HaCaT cells. Therefore, topical formulations containing trehalose-loaded liposomes may significantly reduce UVB-induced molecular damage to DNA and proteins, providing an effect beyond that achieved with other common antioxidants. Notably, these findings indicate the importance of careful selection of the ingredients when formulating novel topical products aimed at reducing the problems associated with photodamage and NMSC.

References

- 1.D’Orazio J, Jarrett S, Amaro-Ortiz A, Scott T. UV radiation and the skin. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:12222–12248. doi: 10.3390/ijms140612222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mabruk MJ, Toh LK, Murphy M, Leader M, Kay E, Murphy GM. Investigation of the effect of UV irradiation on DNA damage: comparison between skin cancer patients and normal volunteers. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:760–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen AC, Halliday GM, Damian DL. Non-melanoma skin cancer: carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Pathology. 2013;45:331–341. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e32835f515c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks R. Photoprotection and prevention of melanoma. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:406–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krutmann J, Schroeder P. Role of mitochondria in photoaging of human skin: the defective powerhouse model. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2009;14:44–49. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2009.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Besaratinia A, Yoon JI, Schroeder C, Bradforth SE, Cockburn M, Pfeifer GP. Wavelength dependence of ultraviolet radiation-induced DNA damage as determined by laser irradiation suggests that cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are the principal DNA lesions produced by terrestrial sunlight. FASEB J. 2011;25:3079–3091. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-187336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ichihashi M, Ueda M, Budiyanto A, et al. UV-induced skin damage. Toxicology. 2003;189:21–39. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svobodova A, Walterova D, Vostalova J. Ultraviolet light induced alteration to the skin. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2006;150:25–38. doi: 10.5507/bp.2006.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A, Pant MC, Singh HS, Khandelwal S. Assessment of the redox profile and oxidative DNA damage (8-OHdG) in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:254–259. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.98980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki YJ, Carini M, Butterfield DA. Protein carbonylation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:323–325. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernerd F, Vioux C, Lejeune F, Asselineau D. The sun protection factor (SPF) inadequately defines broad spectrum photoprotection: demonstration using skin reconstructed in vitro exposed to UVA, UVB or UV-solar simulated radiation. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:242–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baliga MS, Katiyar SK. Chemoprevention of photocarcinogenesis by selected dietary botanicals. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2006;5:243–253. doi: 10.1039/b505311k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaar M, Gilchrest BA. Photoageing: mechanism, prevention and therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:874–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Botanical antioxidants in the prevention of photocarcinogenesis and photoaging. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:678–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jurkiewicz BA, Bissett DL, Buettner GR. Effect of topically applied tocopherol on ultraviolet radiation-mediated free radical damage in skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:484–488. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12605921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheah IK, Halliwell B. Ergothioneine; antioxidant potential, physiological function and role in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 18222012:784–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin JY, Selim MA, Shea CR, et al. UV photoprotection by combination topical antioxidants vitamin C and vitamin E. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:866–874. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul BD, Snyder SH. The unusual amino acid L-ergothioneine is a physiologic cytoprotectant. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emanuele E, Spencer JM, Braun M. From DNA repair to proteome protection: new molecular insights for preventing non-melanoma skin cancers and skin aging. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:274–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wondrak GT. Redox-directed cancer therapeutics: molecular mechanisms and opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:3013–3069. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain NK, Roy I. Effect of trehalose on protein structure. Protein Sci. 2009;18:24–36. doi: 10.1002/pro.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webb KM, DiRuggiero J. Role of Mn2+and compatible solutes in the radiation resistance of thermophilic bacteria and archaea. Archaea. 2012;2012:845756. doi: 10.1155/2012/845756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulrich AS. Biophysical aspects of using liposomes as delivery vehicles. Biosci Rep. 2002;22:129–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1020178304031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maalouf S, El-Sabban M, Darwiche N, Gali-Muhtasib H. Protective effect of vitamin E on ultraviolet B light-induced damage in keratinocytes. Mol Carcinog. 2002;34:121–130. doi: 10.1002/mc.10055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kayasuga-Kariya Y, Iwanaga S, Fujisawa A, et al. Dermal cell damage induced by topical application of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is suppressed by trehalose co-lyophilization in ex vivo analysis. J Vet Med Sci. 2013;75:1619–1622. doi: 10.1292/jvms.12-0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei H, Ca Q, Rahn R, Zhang X, Wang Y, Lebwohl M. DNA structural integrity and base composition affect ultraviolet light-induced oxidative DNA damage. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6485–6490. doi: 10.1021/bi972702f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darr D, Combs S, Dunston S, Manning T, Pinnell S. Topical vitamin C protects porcine skin from ultraviolet radiation-induced damage. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Placzek M, Gaube S, Kerkmann U, et al. Ultraviolet B-induced DNA damage in human epidermis is modified by the antioxidants ascorbic acid and D-alpha-tocopherol. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:304–307. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Njus D, Kelley PM. Vitamins C and E donate single hydrogen atoms in vivo. FEBS Lett. 1991;284:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80672-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shindo Y, Witt E, Han D, et al. Recovery of antioxidants and reduction in lipid hydroperoxides in murine epidermis and dermis after acute ultraviolet radiation exposure. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1994;10:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steenvoorden DP, van Henegouwen GM. The use of endogenous antioxidants to improve photoprotection. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1997;41:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(97)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin FH, Lin JY, Gupta RD, et al. Ferulic acid stabilizes a solution of vitamins C and E and doubles its photoprotection of skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:826–832. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray JC, Burch JA, Streilein RD, Iannacchione MA, Hall RP, Pinnell SR. A topical antioxidant solution containing vitamins C and E stabilized by ferulic acid provides protection for human skin against damage caused by ultraviolet irradiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Césarini JP, Michel L, Maurette JM, Adhoute H, Béjot M. Immediate effects of UV radiation on the skin: modification by an antioxidant complex containing carotenoids. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:182–189. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichihashi M, Funasaka Y, Ohashi A, et al. The inhibitory effect of DL-alpha-tocopheryl ferulate in lecithin on melanogenesis. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:3769–3774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McVean M, Liebler DC. Prevention of DNA photodamage by vitamin E compounds and sunscreens: roles of ultraviolet absorbance and cellular uptake. Mol Carcinog. 1999;24:169–176. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199903)24:3<169::aid-mc3>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu BZ, Mao L, Fan RM, et al. Ergothioneine prevents copper-induced oxidative damage to DNA and protein by forming a redox-inactive ergothioneine-copper complex. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:30–34. doi: 10.1021/tx100214t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markova NG, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Dong KK, Damaghi N, Smiles KA, Yarosh DB. Skin cells and tissue are capable of using L-ergothioneine as an integral component of their antioxidant defense system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1168–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reeve VE, Bosnic M, Rozinova E. Carnosine (beta-alanylhistidine) protects from the suppression of contact hypersensitivity by ultraviolet B (280–320 nm) radiation or by cis urocanic acid. Immunology. 1993;78:99–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emanuele E. Challenging the central dogma of skin photobiology: are proteins more important than DNA? J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2052–2053. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]