Abstract

Several types of immunosuppressive mechanisms in cancer patients have been reported to date. Regulatory T cells (Tregs), which express the master control transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3), are considered to play a major role in hampering antitumor immune response. However, the clinical significance of Tregs in patients with lung cancer has not been fully elucidated. The aim of this study was to investigate the clinical significance of Tregs in the peripheral blood and in resected cancer tissue specimens. We analyzed peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected prior to surgery and resected specimens obtained from 67 patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Peripheral Tregs (pTregs) were detected as CD4+ and FoxP3+ cells by flow cytometry. Immunohistochemical staining for CD4, CD8 and FoxP3 expression was also performed quantitatively by analyzing three randomly selected fields from central regions (cCD4, cCD8 and cFoxP3) and interstitial regions of the tumors (iCD4, iCD8 and iFoxP3). The associations between the expression frequencies in selected cells and clinicopathological parameters were statistically analyzed. The frequency of pTregs was found to be significantly higher in patients with pleural invasion (P=0.0049), vessel invasion (P=0.0009), lymphatic vessel invasion (P=0.0053) and recurrent disease (P=0.0112). Patients with T1 exhibited a significantly higher frequency of cCD4 (P=0.0199) and cCD8 (P=0.0058), although cFoxP3 expression was not significant (P=0.0935). Patients with low levels of cFoxP3/iFoxP3 exhibited a significantly higher frequency of pTregs (P=0.0338) and patients with a high frequency of pTregs exhibited significantly poorer recurrence-free survival (P=0.0071). The multivariate analysis identified pTreg frequency as an independent prognostic factor (P=0.0458). Although the pathological analysis remains controversial, the frequency of pTregs in NSCLC patients may be a useful prognostic biomarker.

Keywords: non-small-cell lung cancer, regulatory T cells, forkhead box P3, immunotherapy, immunosuppression

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common type of cancer worldwide, accounting for 13% of all cancers, with an estimated 1.6 million new cases diagnosed annually (1). Despite the recent implementation of multimodality cancer therapy, including surgical techniques and less invasive radiation therapies, such as proton beam therapy and molecular-targeted chemotherapy, the prognosis of lung cancer remains poor and most of these conventional therapies are often harmful. In fact, the 5-year survival rate of lung cancer is only 9–15%, despite these therapies (2). Therefore, to improve lung cancer survival, novel and less toxic therapies are required. Over the last few years, immunotherapy has been applied to lung cancer treatment as an additional modality with fewer adverse events. A previous phase III MAGE-A3 trial used immunotherapy as an adjuvant therapy for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) following complete pulmonary resection (3); in addition, a phase II L-BLP25 trial investigated a vaccine for patients with advanced disease (4). The clinical effectiveness of those treatment modalities appears to be promising. However, the majority of the results of other immunotherapy trials were not promising (5) and the immunocompromised status of the treated patients was considered to be the major cause of this ineffectiveness.

In a number of previous studies, the patients bearing various types of cancers, particualrly advanced cancer, were immunosuppressed (6–8) and the mechanisms underlying this immunosuppression are considered to be one of the major causes of the failure of cancer immunotherapy. The mechanisms involved in immunosuppression, including tumor production of immunosuppressive cytokines [interleukin-10 (IL-10) or transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)], were previously investigated (9). Recently, regulatory T cells (Tregs) have attracted the attention of tumor immunology researchers, as they have the ability to suppress or regulate cell-mediated immunity. Tregs express CD4 and CD25 on their surface and also express a master control molecule, the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3), in their nucleus (10), which is responsible for their immunosuppressive function. Increased Treg numbers have been reported in various cancer patients with poor prognosis. However, to date, the association of clinicopathological characteristics with systemic Tregs in the peripheral blood and local Tregs in the tumors has not been adequately investigated in patients with NSCLC. In the present study, we analyzed Tregs in the peripheral blood and in resected NSCLC cancer tissues to determine the clinical significance of Tregs in NSCLC patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and blood samples

A total of 67 cases of primary NSCLC were investigated in the present study. These samples represented the material obtained from all the patients who had undergone pulmonary resection and regional lymph node dissection at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Fukushima Medical University Hospital, Fukushima, Japan, between 2007 and 2008. The resected primary tumors were macroscopically and microscopically examined to determine tumor location, size and extent of lymphatic and venous invasion, metastasis to lymph nodes and histological subtype, according to the International Staging System for Lung Tumors, 7th edition (11). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained prior to surgery from all the patients participating in this study, as well as from 10 healthy volunteers. The major clinicopathological characteristics of the patients enrolled in this study are summarized in Table I. Lymphatic and venous invasion (ly and v factor, respectively) was determined with Elastica-Masson staining, as well as hematoxylin and eosin staining. The samples were defined as positive or negative for vessel invasion based on the presence or absence, respectively, of cancer cell emboli in the respective vessels after examining all fields of the cancer tissues.

Table I.

Patient clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics | Patient no. (n=67) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years range (mean ± SD) | 45–83 (68.4±9.0) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 44 | 65.7 |

| Female | 23 | 34.3 |

| Tumor size, cm range (mean ± SD) | 0–14 (3.2±2.2) | |

| T factor | ||

| T1 | 36 | 53.7 |

| T2 | 20 | 29.9 |

| T3 | 4 | 6.0 |

| T4 | 7 | 10.4 |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 45 | 67.2 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 16 | 23.8 |

| Small-cell carcinoma | 2 | 3.0 |

| Other | 4 | 6.0 |

| N factor | ||

| Negative | 17 | 25.4 |

| Positive | 50 | 74.6 |

| p-Stage | ||

| IA | 32 | 47.8 |

| IB | 15 | 22.4 |

| IIA | 4 | 6.0 |

| IIB | 3 | 4.5 |

| IIIA | 6 | 8.9 |

| IIIB | 7 | 10.4 |

| Ly factor | ||

| Negative | 42 | 62.7 |

| Positive | 20 | 29.9 |

| Unknown | 5 | 7.4 |

| V factor | ||

| Negative | 43 | 64.2 |

| Positive | 19 | 28.4 |

| Unknown | 5 | 7.4 |

| Pl factor | ||

| Negative | 50 | 74.6 |

| Positive | 17 | 25.4 |

| Recurrence | ||

| Yes | 15 | 22.4 |

| No | 52 | 77.6 |

SD, standard deviation; n, factor, nodal invasion; ly factor, lymphatic invasion; v factor, venous invasion; pl factor, pleural invasion.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fukushima Medical University and informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Collection and processing of PBMCs

Peripheral venous blood (20–30 ml) was drawn and collected into tubes containing EDTA-2Na. The samples were hand-carried to the laboratory and immediately centrifuged on Ficoll-Paque gradients. The PBMCs were then cryopreserved in cell vials dissolved in cell preservation liquid at −80°C. The PBMCs were recovered by flow cytometric analysis, washed in AIM V medium (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan), counted in the presence of a trypan blue dye to evaluate viability and used immediately.

Flow cytometry

Cell surface and intracellular staining procedures were performed as described previously (12). Briefly, the surfaces of 100 μl of cells (1×106) were stained using 10 μl fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD3, anti-CD8 and anti-CD25, peridinin chlorophyll-conjugated anti-CD4, phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies, all purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA, USA). Isotype control, IgG2a, was included in all the experiments. For intracellular staining, the cells were saponized, washed in cold flow cytometry staining buffer and stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human FoxP3 and its isotype control Rat IgG2a (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). Flow cytometry was performed using FACSCalibur equipped with CellQuest software (both from BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The acquisition and analysis gates were restricted to the lymphocyte gate, as determined by their characteristic forward and side scatter properties. Routinely, the analysis gates were restricted to the CD4+CD25+ T-cell subset. The flow data were analyzed using CellQuest analysis software, version 3.1 (BD Biosciences).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analyses were performed according to the methods previously described (13). Briefly, 3-μm microtome sections were cut from paraffin-embedded lung cancer tissue specimens. Immunoperoxidase staining by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method was performed. The sections were dewaxed in xylene and dehydrated through graded alcohol solutions. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by 20-min incubation with 0.3% (v/v) solution of hydrogen peroxidase (Wako, Osaka, Japan) in 100% methanol. Following incubation in 5% dried skimmed milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at room temperature, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary monoclonal antibody to the FoxP3 protein diluted at 1:100 (ab20034; Abcam Inc., Tokyo, Japan), CD4 diluted at 1:50 (NCL-CD4-1F6; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and CD8 diluted at 1:50 (M7103; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). The primary antibody was then detected using biotinylated secondary anti-mouse IgG antibody (BA-2000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), by the avidin-biotin complex method. The sections were washed several times in PBS after each step and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Muto Pure Chemicals, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), dehydrated through graded alcohol solutions and mounted on glass slides.

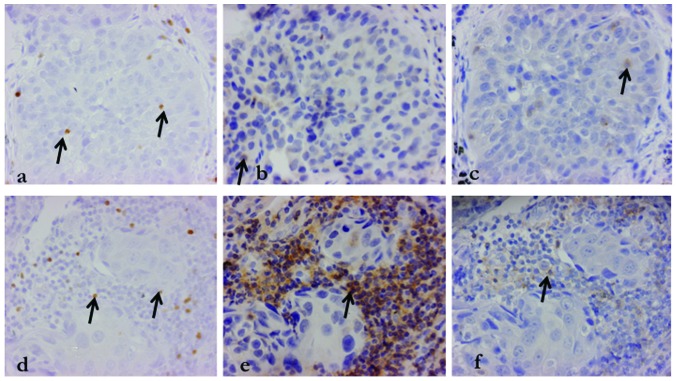

Evaluation of immunohistochemical staining

We selected three random fields from the central and the interstitial regions of the tumor and counted the positively-stained lymphocytes at high-power fields (HPF, 40× objective and 10× eyepiece magnification). We ensured selecting the same field for each stain (CD4, CD8 and FoxP3) and evaluated the central (cFoxP3, cCD4 and cCD8) and interstitial (iFoxP3, iCD4 and iCD8) field of the tumors. To verify the association between the central and interstitial region of the tumors, the cFoxP3/iFoxP3, cCD4/iCD4 and cCD8/iCD8 ratios were calculated. Similarly, the iFoxP3/iCD4, iFoxP3/iCD8cFoxP3/cCD4 and cFoxP3/cCD8 ratios were also calculated. The staining of samples from a representative case of adenocarcinoma is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of an adenocarcinoma specimen. The arrows indicate positive cells for each stain; (a) cFoxP3, (b) cCD4, (c) cCD8, (d) iFoxp3, (e) iCD4 and (f) iCD8. The same field was examined for each stain for accurate validation. FoxP3, forkhead box P3; c, central; i, interstitial.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). The differences between groups were evaluated for statistical significance using the Student’s t-test. Survival curves were drawn according to the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to perform univariate survival analysis, whereas multivariate analysis for survival was performed using the Cox’s proportional hazard model. All the analyses were performed using SPSS statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Peripheral Tregs are significantly correlated with clinicopathological characteristics on flow cytometric analysis

We defined peripheral Tregs (pTregs) as CD4+FoxP3+ lymphocytes, since conventional Tregs display CD4 and CD25 on their cell surface. However, a proportion of Tregs are considered to convert from peripheral naïve T cells to Tregs under Treg-proliferative conditions, thus CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs include all Treg populations.

Patients with NSCLC exhibited a significantly higher frequency of peripheral regulatory T cells compared to healthy volunteers (11.2 vs. 5.6%, respectively; P=0.0093). Table II shows a significant correlation between peripheral regulatory T cells and tumor size (P=0.0217), T factor (T1 vs. T2–4) (P=0.0221), lymphatic vessel invasion (P=0.0053), venous invasion (P=0.0009), pleural invasion (P=0.0049) and recurrence (P=0.0112). There was no significant association between pathological stage and pTregs, although patients at an advanced pathological stage tended to have a high frequency of pTregs (stage I–II, 10.8% vs. stage III–IV, 13.5%; P=0.3533).

Table II.

Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics and frequency of peripheral regulatory T cells.

| Characteristics | CD4+FoxP3+ | (%) P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.0984 | |

| >60 | 10.4 | |

| ≤59 | 13.8 | |

| Gender | 0.5679 | |

| Male | 11.5 | |

| Female | 10.5 | |

| Tumor size, cm | 0.0217 | |

| ≥3.0 | 13.5 | |

| <3.0 | 9.6 | |

| T factor | 0.0221 | |

| T1a-b | 9.4 | |

| T2–4 | 13.3 | |

| Histology | 0.0722 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 10.1 | |

| Other | 13.3 | |

| N factor | 0.1735 | |

| Negative | 10.6 | |

| Positive | 13.3 | |

| p-Stage | 0.3533 | |

| I–II | 10.8 | |

| III–IV | 13.5 | |

| Ly factor | 0.0053 | |

| Negative | 9.7 | |

| Positive | 14.6 | |

| V factor | 0.0009 | |

| Negative | 9.8 | |

| Positive | 15.1 | |

| Pl factor | 0.0049 | |

| Negative | 9.9 | |

| Positive | 15.0 | |

| Recurrence | 0.0112 | |

| Yes | 14.8 | |

| No | 10.2 | |

| Total, range (mean±SD) | 0.98–31.9 (11.1±0.8) |

FoxP3, forkhead box P3; n, factor, nodal invasion; ly factor, lymphatic invasion; v factor, venous invasion; pl factor, pleural invasion SD, standard deviation.

Limited lymphocyte infiltration of larger tumors and restrictive association between number of tumor-infiltrating Tregs and clinicopathological parameters

The correlation between clinicopathological parameters and tumor lymphocyte infiltration is shown in Table III. The data for each parameter were as follows (presented as range, mean ± SD): iFoxP3 (0–48.3, 5.4±1.0), cFoxP3 (0–23.6, 1.6±0.5), iCD4 (3.0–96.0, 35.4±2.9), cCD4 (0–50.4, 9.3±1.4), iCD8 (1.0–66, 19.0±1.8), cCD8 (0–32.6, 7.0±0.98).

Table III.

Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics and tumor lymphocyte infiltration.

| A, Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics and number of interstitially infiltrating lymphocytes in the tumor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Characteristics | iFoxP3 | P-value | iCD4 | P-value | iCD8 | P-value |

| Age, years | 0.9587 | 0.2258 | 0.2316 | |||

| >70 | 5.4 | 31.7 | 16.6 | |||

| ≤69 | 5.3 | 38.8 | 21.1 | |||

| Gender | 0.7112 | 0.0413 | 0.3380 | |||

| Male | 5.1 | 31.1 | 17.8 | |||

| Female | 5.9 | 43.6 | 21.5 | |||

| Tumor size, cm | 0.7903 | 0.7883 | 0.8905 | |||

| ≥3.0 | 5.7 | 34.5 | 19.4 | |||

| <3.0 | 5.1 | 36.0 | 18.8 | |||

| T factor | 0.6609 | 0.4704 | 0.1398 | |||

| T1a-b | 5.7 | 37.3 | 21.5 | |||

| T2–4 | 4.8 | 33.1 | 16.1 | |||

| Histology | 0.3714 | 0.3220 | 0.5105 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 6.0 | 37.5 | 19.9 | |||

| Other | 3.9 | 31.2 | 17.3 | |||

| N factor | 0.7582 | 0.3828 | 0.6965 | |||

| Negative | 5.5 | 34.0 | 118.7 | |||

| Positive | 4.7 | 40.1 | 20.4 | |||

| p-Stage | 0.6614 | 0.9614 | 0.2397 | |||

| I–II | 5.6 | 35.5 | 18.1 | |||

| III | 4.2 | 35.1 | 23.9 | |||

| Ly factor | 0.2930 | 0.6320 | 0.2930 | |||

| Negative | 6.1 | 34.4 | 20.3 | |||

| Positive | 3.6 | 37.6 | 16.2 | |||

| V factor | 0.5860 | 0.7802 | 0.8501 | |||

| Negative | 5.7 | 34.9 | 19.3 | |||

| Positive | 4.4 | 36.7 | 18.4 | |||

| Pl factor | 0.3873 | 0.6061 | 0.1595 | |||

| Negative | 5.9 | 34.5 | 20.5 | |||

| Positive | 3.8 | 38.0 | 14.7 | |||

| Recurrence | 0.9914 | 0.7614 | 0.8922 | |||

| Yes | 5.4 | 37.1 | 19.5 | |||

| No | 5.3 | 34.9 | 18.9 | |||

|

| ||||||

| B, Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics and number of centrally infiltrating lymphocytes in the tumor | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Clinical characteristics | cFoxP3 | P-value | cCD4 | P-value | cCD8 | P-value |

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | 0.4626 | 0.7064 | 0.9857 | |||

| >70 | 2.0 | 8.8 | 7.0 | |||

| ≤ | 69 | 1.2 | 9.8 | |||

| Gender | 0.3777 | 0.3446 | 0.4761 | |||

| Male | 1.9 | 8.4 | 6.5 | |||

| Female | 0.9 | 11.1 | 8.0 | |||

| Tumor size, cm | 0.1659 | 0.0098 | 0.0036 | |||

| ≥3.0 | 0.6 | 5.1 | 3.7 | |||

| <3.0 | 2.2 | 12.2 | 9.3 | |||

| T factor | 0.0935 | 0.0199 | 0.0058 | |||

| T1a-b | 2.4 | 12.2 | 9.5 | |||

| T2–4 | 0.6 | 5.9 | 4.2 | |||

| Histology | 0.6971 | 0.0359 | 0.8868 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.7 | 11.3 | 7.1 | |||

| Other | 1.3 | 5.2 | 6.8 | |||

| N factor | 0.2457 | 0.2664 | 0.4223 | |||

| Negative | 1.9 | 10.1 | 7.5 | |||

| Positive | 0.4 | 6.5 | 5.5 | |||

| p-Stage | 0.4334 | 0.6448 | 0.7209 | |||

| I–II | 1.8 | 9.6 | 7.2 | |||

| III | 0.6 | 7.9 | 6.2 | |||

| Ly factor | 0.1850 | 0.6417 | 0.3064 | |||

| Negative | 2.1 | 10.9 | 7.9 | |||

| Positive | 0.5 | 5.2 | 4.7 | |||

| V factor | 0.1379 | 0.0607 | 0.1446 | |||

| Negative | 2.1 | 10.9 | 7.9 | |||

| Positive | 0.2 | 5.2 | 4.7 | |||

| Pl factor | 0.1024 | 0.0244 | 0.0066 | |||

| Negative | 1.8 | 11.1 | 8.6 | |||

| Positive | 0.1 | 4.2 | 2.7 | |||

| Recurrence | 0.4666 | 0.3956 | 0.1743 | |||

| Yes | 0.8 | 7.0 | 4.5 | |||

| No | 1.8 | 9.9 | 7.7 | |||

|

| ||||||

| C, Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics and the ratio of centrally/interstitially infiltrating lymphocytes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Characteristics | cFoxP3/iFoxP3, % | P-value | cCD4/iCD4, % | P-value | cCD8/iCD8, % | P-value |

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | 0.5000 | 0.9758 | 0.6371 | |||

| >70 | 39.4 | 37.2 | 66.4 | |||

| ≤69 | 29.2 | 36.9 | 55.6 | |||

| Gender | 0.8283 | 0.7747 | 0.9926 | |||

| Male | 35.3 | 35.9 | 60.8 | |||

| Female | 40.0 | 39.1 | 60.6 | |||

| Tumor size, cm | 0.0301 | 0.0096 | 0.2192 | |||

| ≥3.0 | 13.0 | 21.1 | 44.0 | |||

| <3.0 | 46.2 | 48.1 | 72.4 | |||

| T factor | 0.1274 | 0.0292 | 0.4011 | |||

| T1a-b | 43.5 | 47.4 | 69.6 | |||

| T2–4 | 20.2 | 24.8 | 50.4 | |||

| Histology | 0.6591 | 0.0501 | 0.4304 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 36.0 | 44.1 | 67.0 | |||

| Other | 28.5 | 22.4 | 47.9 | |||

| N factor | 0.3311 | 0.0604 | 0.1412 | |||

| Negative | 38.4 | 42.3 | 69.9 | |||

| Positive | 21.8 | 19.1 | 30.3 | |||

| p-Stage | 0.8674 | 0.4532 | 0.3573 | |||

| I–II | 34.6 | 38.8 | 65.4 | |||

| III | 31.3 | 28.1 | 37.1 | |||

| Ly factor | 0.5473 | 0.8568 | 0.6802 | |||

| Negative | 37.2 | 36.3 | 57.6 | |||

| Positive | 27.5 | 38.4 | 67.8 | |||

| V factor | 0.0630 | 0.1287 | 0.8245 | |||

| Negative | 41.9 | 50.0 | 62.3 | |||

| Positive | 9.7 | 24.2 | 57.0 | |||

| Pl factor | 0.0156 | 0.0849 | 0.6691 | |||

| Negative | 43.6 | 42.3 | 63.7 | |||

| Positive | 1.0 | 22.0 | 52.6 | |||

| Recurrence | 0.2634 | 0.1563 | 0.1760 | |||

| Yes | 17.4 | 22.8 | 31.3 | |||

| No | 38.3 | 40.9 | 68.7 | |||

FoxP3, forkhead box P3; n, factor, nodal invasion; ly factor, lymphatic invasion; v factor, venous invasion; pl factor, pleural invasion; c, central; i, interstitial.

The presence of tumor-infiltrating Tregs was not found to be correlated with clinicopathological parameters. However, from the aspect of cFoxP3/iFoxP3 ratio, larger tumors had lower cFoxP3/iFoxP3 ratios (≥3 cm, 13.0 vs. <3.0, 46.2; P=0.0301) and patients with pleural invasion also exhibited lower ratios (P=0.0156) (Table IIIC).

cCD4 expression was significantly lower in larger tumors (P=0.0098), T2–4 tumors (P=0.0199), non-adenocarcinoma (P=0.0359) and patients with pleural invasion (P=0.0244). Similar associations were reported for cCD8: larger tumors, T2–4 tumors and patients with pleural invasion had lower levels of cCD8 lymphocytes (P=0.0036, P=0.0058 and P=0.0066, respectively). The number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes was very low, particularly in non-adenocarcinomas. In addition, patients who relapsed had lower cCD4 and cCD8 lymphocytes, although the difference was not statistically significant (Table IIIB).

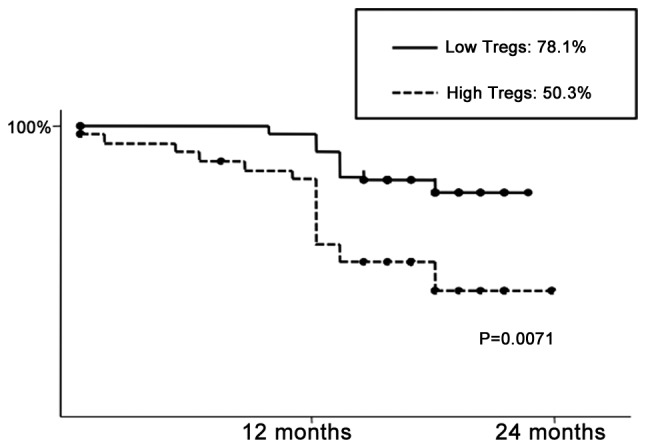

pTreg frequency in NSCLC patients correlates with recurrence-free survival

The median follow-up was 21.3 months and relapse occurred in 15 patients, while 11 patients succumbed to the disease during follow-up. Patients with a high frequency of pTregs exhibited a significantly poorer recurrence-free survival (P=0.0071) (Fig. 2). The univariate analysis revealed that tumor size [≥3 cm; hazard ratio (HR)=3.773; P=0.017], blood vessel invasion (HR=2.589; P=0.0205), pleural invasion (HR=3.910; P=0.0011) and CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs (HR=2.419; P=0.0418) were significant prognostic factors (Table IVA). The multivariate analysis identified CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs (P=0.0458), lymphatic vessel invasion (P=0.0360), blood vessel invasion (P=0.0105) and pleural invasion (P=0.0360) as independent prognostic factors (Table IVB).

Figure 2.

Two-year recurrence-free survival following pulmonary resection. Patients who had a higher frequency of peripheral regulatory T cells (pTregs) exhibited a significantly poorer recurrence-free survival (P=0.0071).

Table IV.

Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics, peripheral regulatory T cells and survival by univariate and multivariate analysis.

| A, Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics, peripheral regulatory T cells and survival by univariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Characteristics | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidential interval | P-value |

| Age, years | 0.677 | 0.30–1.51 | 0.3395 |

| >70 vs. ≤69 | |||

| Gender | 0.910 | 0.39–2.13 | 0.8282 |

| Male vs. female | |||

| Tumor size, cm | 3.773 | 1.646–8.647 | 0.017 |

| ≥3.0 vs. <3.0 | |||

| T factor | 0.323 | 0.141–0.740 | 0.0076 |

| T1 vs. T2–4 | |||

| Histology | 0.418 | 0.186–0.936 | 0.0340 |

| Adenocarcinoma vs. other | |||

| p-Stage | 0.468 | 0.174–1.261 | 0.1333 |

| IA vs. other | |||

| Ly factor | 1.034 | 0.442–2.422 | 0.9382 |

| Negative vs. positive | |||

| V factor | 2.589 | 1.157–5.791 | 0.0205 |

| Negative vs. positive | |||

| Pl factor | 3.910 | 1.726–8.857 | 0.0011 |

| Negative vs. positive | |||

| CD4+/FoxP3+/CD4+ | 2.419 | 1.033–5.661 | 0.0418 |

| High vs. low | |||

| cFoxP3/iFoxP3 | 0.744 | 0.287–1.931 | 0.5439 |

| High vs. low | |||

| iFoxP3 | 0.908 | 0.408–2.023 | 0.8139 |

| High vs. low | |||

| iCD4 | 1.080 | 0.484–2.413 | 0.8502 |

| High vs. low | |||

| cCD4 | 0.696 | 0.310–1.561 | 0.3792 |

| High vs. low | |||

| cCD4/iCD4 | 0.607 | 0.265–1.391 | 0.2380 |

| High vs. low | |||

| iCD8 | 0.646 | 0.289–1.447 | 0.2884 |

| High vs. low | |||

| cCD8 | 0.519 | 0.230–1.169 | 0.1135 |

| High vs. low | |||

| cCD8/cCD8 | 0.803 | 0.360–1.794 | 0.5932 |

| High vs. low | |||

| iFoxP3/iCD4 | 1.067 | 0.478–2.384 | 0.8737 |

| High vs. low | |||

| iFoxP3/iCD8 | 1.005 | 0.994–1.016 | 0.1887 |

| High vs. low | |||

| cFoxP3/cCD4 | 0.520 | 0.224–1.205 | 0.1271 |

| High vs. low | |||

| cFoxP3/cCD8 | 0.535 | 0.228–1.255 | 0.1503 |

| High vs. low | |||

|

| |||

| B, Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics, peripheral regulatory T cells and survival by multivariate analysis. | |||

|

| |||

| Factor | Coefficient | Standard error | P-value |

|

| |||

| Age (≥60 years) | 0.250 | 0.624 | 0.6883 |

| Gender | −0.374 | 0.581 | 0.5197 |

| T1/T2 or T3/T4 | −0.701 | 0.678 | 0.3008 |

| N factor | 0.445 | 0.766 | 0.5610 |

| p-Stage IA or other | −0.079 | 0.753 | 0.9165 |

| Ly factor | −2.584 | 0.805 | 0.0360 |

| V factor | 1.797 | 0.702 | 0.0105 |

| Pl factor | 1.688 | 0.805 | 0.0360 |

| cFoxP3/cCD4 >2.4% | 0.802 | 0.676 | 0.2360 |

| CD4+FoxP3+Treg | 1.087 | 0.544 | 0.0458 |

FoxP3, forkhead box P3; n, factor, nodal invasion; ly factor, lymphatic invasion; v factor, venous invasion; pl factor, pleural invasion; c, central; i, interstitial.

Discussion

Immunosuppression is commonly associated with patients with advanced-stage cancer. The mechanism underlying this immunosuppressive effect has been gradually elucidated and the presence of Tregs is considered to be a key component in cancer patients. In this study, we focused on the immunocompromised status of patients with lung cancer and observed that increased numbers of pTregs were significantly correlated with worse clinicopathological conditions and disease recurrence. Our data clearly support previous cancer studies, including lung cancer, applying flow cytometric analysis (14–16). Apart from flow cytometric analysis, we used immunohistochemical analysis to demonstrate that patients with a lower cFoxP3/iFoxP3 ratio tend to have larger tumors, pleural invasion and suffer from disease relapse. In addition to FoxP3 staining, we investigated the distribution of cCD4 and cCD8 in the tumors and observed that these effector cells were significantly decreased in larger tumors.

Sakaguchi et al (17) previously reported that regulatory T cells, previously referred to as suppressor T cells, express CD4 and IL-2 receptor α-chain (CD25) on their cell surface and display suppressor functions. Naturally occurring thymus-derived CD4+CD25+ Tregs are a T-cell population with immunosuppressive properties that constitute 5–10% of the total peripheral CD4+ T cells. The master control gene FoxP3 was later identified and it was revealed that FoxP3 was specific to regulatory T cells and absolutely necessary for their suppressive function (10,18,19). FoxP3 further induces peripheral naïve T cells to become regulatory T cells and these induced Tregs also exert a suppressive effect. The precise mechanism of immunosuppression remains unclear. All Tregs require T cell receptor (TCR) triggering for their suppressive activity. The major pathway of immunosuppression by Tregs may be through direct cell-to-cell suppression of effector T cells, producing soluble factors, such as immunosuppressive IL-10 and TGF-β (20). The association between pTregs and various types of cancer has been extensively investigated (14–16,21) and the majority of those studies concluded that the frequency of pTregs in patients with cancer is elevated and is correlated with a poor prognosis, which was consistent with our results. From these collective data, it is most likely that pTregs are involved in cancer progression. However, among those previous studies, data on NSCLC are relatively rare; therefore, our NSCLC data may be valuable.

In contrast to the results referring to pTregs, the immunohistochemical assessment of Tregs in specific tumor locations appears to be controversial. Heimberger et al (22) and Grabenbauer et al (23) investigated local tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes using tissue microarrays. Their conclusions, however, were conflicting, despite their studies being performed under almost identical conditions and using identical protocols. Hiraoka et al (24) investigated patients with pancreatic cancer, premalignant pancreatic lesions, hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic liver tumor at HPF (40× objective and 10× eyepiece magnification) in at least three fields and concluded that an increasing prevalence of Tregs appeared to be an unfavorable prognostic factor (25). Siddiqui et al (26) reported that the number of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells was not associated with cancer death, whereas CD4+CD25+FoxP3− T cells were significantly associated with outcome in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Badoual et al (27) applied immunofluorescence staining to Treg studies and their results indicated that infiltration by regulatory CD4+FoxP3+ T cells was positively associated with better locoregional control in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. As regards lung cancer, Petersen et al (28) reported that the increase in local Tregs correlated with poor prognosis; however, Ishibashi et al (29) reported opposite findings; thus, the histological analysis of regulatory T cells in patients with lung cancer yields controversial results. Those previous studies revealed that the clinical significance of local tumor lymphocyte evaluation is contentious. One of the reasons for these variable results of immunohistochemical staining may be the difficulty in evaluation.

Despite these difficulties, our immunohistochemical examination yielded significant findings, one of which was the tendency of non-adenocarcinomas and large-sized tumors to have lower CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocyte numbers. Schneider et al (30) reported FoxP3+ Treg accumulation and a decrease in the natural killer cells in the center of adenocarcinomas, whereas squamous cell carcinomas displayed less profound accumulation of Tregs. We demonstrated that the number of cCD4+ lymphocytes in adenocarcinomas was significantly higher compared to that in other histological types. According to these results, lymphocytes hardly infiltrate the tumor center in larger-sized tumors and squamous cell carcinomas, which usually grow expansively. An additional significant finding was that patients with high numbers of CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocytes exhibited relatively better outcomes, although this was not found to be statistically significant. Hiraoka et al (31) reported that concurrent infiltration by CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells is a favorable prognostic factor; Zhang et al (32) reported that the number of intratumoral T cells correlates with improved clinical outcome in advanced ovarian carcinoma; our results in this study were similar to other previous studies, as mentioned above (33,34).

Furthermore, we discovered that large tumors may prevent Treg infiltrates entering the tumor site and decreased cFoxP3 expression at the tumor site was significantly correlated with high frequency of pTregs. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon remains unclear, but we hypothesize based on our results that local trapping of Tregs in the tumor caused by unknown factors may affect the peripheral expansion of Tregs and subsequently affect patient outcome. One reason for the regulation of Treg distribution may be local CD4+ cells.

In this study, we demonstrated the clinical impact of local as well as systemic Tregs. Tregs are clearly correlated with worse clinical conditions; therefore if we manipulate Treg function we may overcome the present shortcomings of clinical immunotherapy. To date, various attempts have been made to reverse this immunosuppressive status using anti-CD25 antibody (35–37), inhibition of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathway (38), or anti-glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis receptor (GITR) family-related protein (39). Yamaguchi et al (40) reported that folate receptor 4 expression is also specific to Tregs and may be a candidate for selective Treg elimination. Furthermore, vaccination against FoxP3 was also previously attempted in vivo (41); thus, this FoxP3-targeted therapy may be used to treat patients with increased Treg numbers. We may be able to select patients who are suitable for these Treg-targeted therapies using our protocol. Further research and continuous treatment trials may improve lung cancer survival using this immunosuppression-targeted therapy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Takuya Tsunoda (Oncotherapy Science, Tokyo, Japan) for his assistance with the manuscript. This study was solely supported by the research expense program of our Institute, with no additional grant support.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang T, Nelson RA, Bogardus A, Grannis FW., Jr Five-year lung cancer survival: which advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer patients attain long-term survival? Cancer. 2010;116:1518–1525. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyagi P, Mirakhur B. MAGRIT: the largest-ever phase III lung cancer trial aims to establish a novel tumor-specific approach to therapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10:371–374. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butts C, Maksymiuk A, Goss G, et al. Updated survival analysis in patients with stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung cancer receiving BLP25 liposome vaccine (L-BLP25): phase IIB randomized, multicenter, open-label trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1337–1342. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombo MP, Piconese S. Regulatory-T-cell inhibition versus depletion: the right choice in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:880–887. doi: 10.1038/nrc2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabinovich GA, Gabrilovich D, Sotomayor EM. Immunosuppressive strategies that are mediated by tumor cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:267–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27:5904–5912. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiteside TL. Inhibiting the inhibitors: evaluating agents targeting cancer immunosuppression. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:1019–1035. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2010.482207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer International Staging Committee; Participating Institutions: The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roncador G, Brown PJ, Maestre L, et al. Analysis of FOXP3 protein expression in human CD4+CD25+regulatory T cells at the single-cell level. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1681–1691. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf D, Wolf AM, Rumpold H, et al. The expression of the regulatory T cell-specific forkhead box transcription factor FoxP3 is associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8326–8331. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichihara F, Kono K, Takahashi A, Kawaida H, Sugai H, Fujii H. Increased populations of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with gastric and esophageal cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4404–4408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liyanage UK, Moore TT, Joo HG, et al. Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2002;169:2756–2761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf AM, Wolf D, Steurer M, Gastl G, Gunsilius E, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Increase of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:606–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakaguchi S. The origin of FOXP3-expressing CD4+regulatory T cells: thymus or periphery. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1310–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI20274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cools N, Ponsaerts P, Van Tendeloo VF, Berneman ZN. Regulatory T cells and human disease. Clin Dev Immunol. 2007;2007:89195. doi: 10.1155/2007/89195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokokawa J, Cereda V, Remondo C, et al. Enhanced functionality of CD4+CD25(high)Foxp3+regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood of patients with prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1032–1040. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heimberger AB, Abou-Ghazal M, Reina-Ortiz C, et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of Foxp3+regulatory T cells in human gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5166–5172. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grabenbauer GG, Lahmer G, Distel L, Niedobitek G. Tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic T cells but not regulatory T cells predict outcome in anal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3355–3360. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiraoka N, Onozato K, Kosuge T, Hirohashi S. Prevalence of Foxp3+regulatory T cells increases during the progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its premalignant lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5423–5434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi N, Hiraoka N, Yamagami W, et al. Foxp3+regulatory T cells affect the development and progression of hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:902–911. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siddiqui SA, Frigola X, Bonne-Annee S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating Foxp3-CD4+CD25+T cells predict poor survival in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2075–2081. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badoual C, Hans S, Rodriguez J, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating CD4+T-cell subpopulations in head and neck cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:465–472. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen RP, Campa MJ, Sperlazza J, et al. Tumor infiltrating Foxp3+regulatory T-cells are associated with recurrence in pathologic stage I NSCLC patients. Cancer. 2006;107:2866–2872. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishibashi Y, Tanaka S, Tajima K, Yoshida T, Kuwano H. Expression of Foxp3 in non-small cell lung cancer patients is significantly higher in tumor tissues than in normal tissues, especially in tumors smaller than 30 mm. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:1315–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider T, Kimpfler S, Warth A, et al. Foxp3+regulatory T cells and natural killer cells distinctly infiltrate primary tumors and draining lymph nodes in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:432–438. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820b80ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiraoka K, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, et al. Concurrent infiltration by CD8+T cells and CD4+T cells is a favourable prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:275–280. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho Y, Miyamoto M, Kato K, et al. CD4+and CD8+T cells cooperate to improve prognosis of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1555–1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukunaga A, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, et al. CD8+tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes together with CD4+tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and dendritic cells improve the prognosis of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2004;28:e26–e31. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200401000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallimore A, Sakaguchi S. Regulation of tumour immunity by CD25+T cells. Immunology. 2002;107:5–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morse MA, Hobeika AC, Osada T, et al. Depletion of human regulatory T cells specifically enhances antigen-specific immune responses to cancer vaccines. Blood. 2008;112:610–618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-135319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onizuka S, Tawara I, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi S, Fujita T, Nakayama E. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor alpha) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutmuller RP, van Duivenvoorde LM, van Elsas A, et al. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25+regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2001;194:823–832. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ko K, Yamazaki S, Nakamura K, et al. Treatment of advanced tumors with agonistic anti-GITR mAb and its effects on tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+CD25+CD4+regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:885–891. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaguchi T, Hirota K, Nagahama K, et al. Control of immune responses by antigen-specific regulatory T cells expressing the folate receptor. Immunity. 2007;27:145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nair S, Boczkowski D, Fassnacht M, Pisetsky D, Gilboa E. Vaccination against the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3 enhances tumor immunity. Cancer research. 2007;67:371–380. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]