Abstract

Lung cancer patients and their family caregivers face a wide range of potentially distressing symptoms across the four domains of quality of life. A multi-dimensional approach to addressing these complex concerns with early integration of palliative care has proven beneficial. This article highlights opportunities to integrate social work using a comprehensive quality of life model and a composite patient scenario from a large lung cancer educational intervention National Cancer Institute-funded program project grant.

Keywords: Oncology Social Work, Palliative Care, Lung Cancer, Quality-of-Life Model, Suffering, Family Caregiver Support

Overview

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide and is a leading cause of cancer deaths (World Health Organization, 2013). Patients with lung cancer face a high degree of symptom burden and a poor prognosis, with often debilitating treatment regimens resulting in a multitude of concerns including: fatigue, weight loss, dyspnea, cachexia, coughing, difficulty sleeping, changes in sexual functioning, anxiety, guilt and spiritual issues (Akin, Can, Aydiner, Ozdilli, & Durna, 2010; Cleeland, Mendoza, Wang, et al, 2011; Lindau, Surawska, Paice & Baron, 2011; Yount, Beaumont, Rosenbloom, et al, 2012). The impact on patient quality of life is compounded by the fact that lung cancer patients tend to be older, have multiple co-morbidities and may have experienced a prior cancer diagnosis (Ferrell, Koczywas, Grannis & Harrington, 2011).

Family members of lung cancer patients commonly report distress, anxiety and concerns regarding the financial, physical and social toll of caregiving, and have questions about their preparedness for caregiving as the illness progresses (Given, Given & Sherwood, 2012, Murray, Kendall, Boyd, Grant, Highet & Sheikh, 2010). Patients and caregivers also report challenges navigating the healthcare system and accessing needed community resources on a timely basis (Liao, Liao, Shun et al, 2011).

Fujinami and colleagues (2012) focused on the specific quality of life concerns family caregivers (FCGs) face. The multi-faceted stressors associated with lung cancer led the authors to recommend an interdisciplinary focus to meet the needs of both patients and their caregivers, noting that nurses and social workers are especially well-suited to provide this level of education and support. Not uncommonly, patients are concerned about being a burden on their families and FCGs worry that they may not be able to protect the patient from suffering (Grant, Sun, Fujinami, et al, 2013). Yet despite the numerous challenges facing FCGs, there are also numerous positives associated with the experience of caregiving. Individualized and culturally congruent support for FCGs contributes to positive social well-being of FCGs (Otis-Green & Juarez, 2012).

Healthcare professionals have an important role in assessing patient coping and supporting effective self-care strategies to improve quality of life (John, 2010); yet despite these complex multi-dimensional concerns, too often healthcare professionals focus almost exclusively upon the physical symptoms associated with the illness (Huhmann, & Camporeale, 2012). It is perhaps not surprising that early integration of palliative care has been found to provide numerous benefits, both to lung cancer patients and to their FCGs including improved quality and even length of life. (Temel, Greer, Muzikansky et al, 2010). Although palliative care has by its very definition an interdisciplinary approach to care, with physicians, nurses, social workers and chaplains recommended to be an integral part of the collaborative team (National Consensus Project, 2013; Altilio, Otis-Green & Dahlin, 2008; Otis-Green, 2013), many palliative care teams currently exist that are comprised exclusively of physician/nurse dyads.

High-functioning interprofessional teams that include psychosocial professionals are needed to effectively provide the level of nuanced, culturally congruent and “person-centered” care necessary to address the concerns of an aging population (Institute of Medicine, 2013). This article uses a composite patient scenario to highlight the important role of social work as a critical element in the provision of quality palliative care in addressing the complex quality of life concerns of lung cancer patients and FCGs.

Study Background

The patient scenario presented in this article is a composite derived from a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded Program Project (PO1) conducted at a National Comprehensive Cancer Center-designated urban hospital. The Palliative Care for Quality of Life and Symptom Concerns in Lung Cancer project focuses on palliative care (PC), quality of life (QOL), and symptom management across the trajectory of lung cancer and is described in more detail elsewhere (Koczywas, Cristea, Thomas, et al, 2013). This program project tests usual care versus a palliative care educational intervention delivered by an advanced practice nurse (APN). The intervention curriculum was specifically tailored for both early and late stage lung cancer patients and also included a targeted FCG component. The curriculum included information and resources relevant to each of the four domains (physical, psychological, social and spiritual) of the City of Hope Quality-of-Life Model (City of Hope Pain & Palliative Care Resource Center: http://prc.coh.org/qual_life.asp). Additionally, the FCG modules integrated self-care strategies within each of the four domains.

A key element of the intervention is the weekly interdisciplinary care conferences where the APN presented an overview of the patient and family caregiver situation. In addition to the investigative team, members of the diverse clinical team include surgeons, oncologists, pulmonologists, palliative care physicians, pulmonary rehabilitation physicians, geriatric oncologists, nurses, social workers, chaplains, dietitians and physical therapists all of whom contributed to developing a comprehensive and customized plan of care. Recommendations from the meeting were used to further inform the educational intervention.

Table 1 lists the battery of assessment instruments selected for the project grant to identify potential concerns within each of the four quality of life domains, as well as tools that measure caregiver burden and caregiving skills preparedness. Table 1 also indicates whether the instrument was used for the patient or family caregiver and provides links and references for additional information on the tool. Findings from these instruments guided the development of a customized care plan for each patient that are presented to the investigative team at the weekly interdisciplinary care conferences. Preliminary findings from this study indicated that psychosocial-spiritual concerns were the most troubling to the patients and FCGs. These findings underscore the importance of the early integration of social work for this vulnerable patient population (Koczywas, Cristea, Thomas, et al, 2013). The National Association of Social Workers’ Standards for Social Work Practice in Palliative Care (NASW, 2004) calls for the early inclusion and integration of social work in the delivery of palliative care to address these complex and inter-related concerns of patients and their families and outlines key recommendations to guide social work practice in this field.

Table 1.

Assessment Instruments Used for the Palliative Care for Quality of Life and Symptom Concerns in Lung Cancer P01 Study

| Instrument Name | Link & References | Early Stage | Late Stage | Family Caregiver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical/Functional Well-Being: | ||||

| The Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale(IADLS):[subscale of the Older American Resources and Services (OARS)]: | http://www.abramsoncenter.org/PRI/documents/IADL.pdf | ✓ | ✓ | |

| The Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADLS): | Stewart, A., Ware. J. (1992). Measuring function and well-being: the Medical Outcomes Study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) | http://www.npcrc.org/usr_doc/adhoc/painsymptom/memorial_symptom_assessment_scale.pdf | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Karnofsky Performance Scale: | http://www.hospicepatients.org/karnofsky.html | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Timed “Up and Go”: | http://www.fallpreventiontaskforce.org/pdf/TimedUpandGoTest.pdf | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Psychological Well-Being: | ||||

| The Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test (BOMC): | http://www.gcrweb.com/alzheimersDSS/assess/subpages/alzpdfs/bomc.pdf | ✓ | ✓ | |

| The Psychological Distress Thermometer: | http://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_with_cancer/pdf/nccn_distress_thermometer.pdf | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social Well-Being: | ||||

| The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Activity Limitations Scale): | Stewart, A., Ware. J. (1992). Measuring function and well-being: the Medical Outcomes Study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. | ✓ | ✓ | |

| The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey: | Stewart, A., Ware. J. (1992). Measuring function and well-being: the Medical Outcomes Study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Spiritual Well-Being: | ||||

| Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spirituality Subscale (FACIT-Sp-12): | http://www.facit.org/FACITOrg/Questionnaires | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Overall Quality of Life: | ||||

| The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy –Lung (FACT-L version 4): | http://www.facit.org/FACITOrg/Questionnaires | ✓ | ✓ | |

| The City of Hope QOL-Patient: | http://prc.coh.org/QOL-CS.pdf | ✓ | ✓ | |

| The City of Hope QOL-Family: | http://prc.coh.org/QOL-Family.pdf | ✓ | ||

| Caregiver Burden Scale: | Archbold, P. G., Greenlick, M.R., Harvath, T. (1990). Mutuality and preparedness of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & health. 13(6): 375–384. | ✓ | ||

| Montgomery, R.V., Stull, D.E, Borgatta, E.F. (1985). Measurement and the analysis of burden. Research on Aging. Mar: 7(1): 137–152. | ✓ | |||

| Skills Preparedness: | Schumacher, K.L., Stewart, B.J., Archbold, P.G. (2007). Mutuality and preparedness moderate the effects of caregiving demand on cancer family caregiver outcomes. Nursing Research. 56(6): 425–433. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000299852.75300.03 | ✓ | ||

Comprehensive Quality-of-Life Model Applied to Lung Cancer

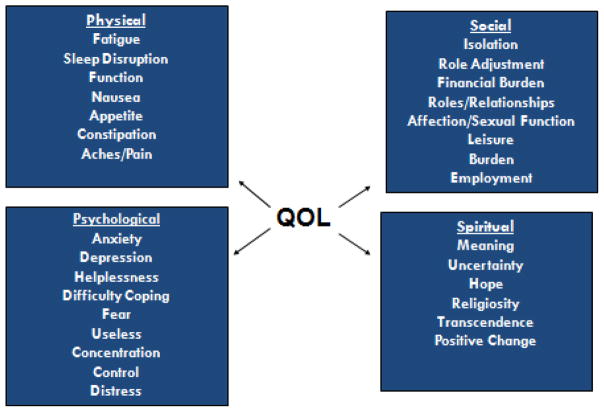

The investigative team applied the City of Hope Quality of Life Model (City of Hope Pain & Palliative Care Resource Center: http://prc.coh.org/qual_life.asp) to lung cancer patients, adapting it to reflect the numerous symptoms and concerns most commonly associated with lung cancer and its treatment (see Figure 1). Social workers in the oncology setting can effectively assess for needs in each of these domains and provide the necessary clinical and practical care or refer the patient to the appropriate services.

Figure 1.

City of Hope Quality of Life (QOL) Model Applied To Lung Cancer

Tables 2–5 provide a range of possible social work interventions and referrals to consider when caring for patients with lung cancer. Careful screening and assessment is necessary to determine which services will be most appropriate for which patients. As patient concerns are likely to evolve over the trajectory of the illness, periodic re-screening, especially at critical times of transition is essential. Key transition points include diagnosis, changes in treatment, recurrence, changes in prognosis and unanticipated or extended intensive care admissions. Novice oncology social workers may not have competencies in each of these skill-sets, nor will each community or hospital environment offer all of the listed referral services. The listings are not exhaustive or exclusive and there are many areas of potential overlap. Resource rich communities may offer additional services and seasoned practitioners may bring additional skills to the table. The oncology social worker needs to be a reflective clinician aware of his or her limitations and what resources are available locally or virtually for the population that they serve.

Patient Scenario

The following composite patient scenario highlights a range of quality of life concerns common for lung cancer patients and underscores the importance of involving social workers early in the care of those facing lung cancer. As key members of the interdisciplinary palliative care team, their “person in the environment” perspective is critical to the provision of person-centered and family-focused care. Social workers can facilitate goals of care conferences to ensure that the medical team, patient and family are in coherence regarding an appropriate plan of care. The social worker can provide anticipatory guidance to help the patient and family prepare for the next steps in their illness journey and provide culturally congruent interventions that are individually tailored to meet the specific needs and priorities of the patient and FCG.

Mr. J is a 63 year old Caucasian male with stage IV, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). He has a history of having smoking one pack per day for twenty-two years. He reports quitting thirteen years ago “cold turkey.” His chief concerns now are shortness of breath (SOB), a dry cough, and moderate fatigue, anxiety, and depression. He has received three lines of chemotherapy with disease progression, but his illness is currently responding to treatment and his disease is listed as “stable.” He understands that his treatment is not expected to cure his cancer. As is common for older adults, he has a variety of co-morbidities including obesity, diabetes, hypertension and coronary artery disease. Mr. J has a high school education and is a retired truck driver. He has been married for forty-two years. His wife is also retired and provides his care. They have two adult children who live locally. They state their religious affiliation as Christian, but are not currently active in their congregation.

At the initial consultation with the medical oncologist, screening questions alerted the team to a wide range of concerns facing the couple. Mrs. J became tearful and expressed worry, fear and uncertainty about the future. She has a history of cardiac disease and arthritis and is concerned about her ability to care for her husband as his disease worsens. Although she anticipates that their adult children would be available to help “if needed,” she has been reluctant to ask, as she does not want to “worry” them as they are very busy with their own families. The medical oncologist discussed the importance of an oncology social worker being a part of their plan of care and she emphasized the many potential benefits provided by the clinical social work department, and how social workers play a key role of the interdisciplinary care team in supporting patients and families. A referral was made to the oncology social worker to complete a comprehensive biopsychosocial-spiritual assessment.

Physical Well Being

Table 2 provides examples of possible interventions to address the physical concerns commonly associated with lung cancer. In many environments, it will be the social worker who is able to provide the most comprehensive assessment of patient concerns and who recognizes additional consultation and referrals useful for the patient situation. The social worker is well positioned to explore the complex interconnections among symptoms and to identify how underlying anxiety and/or depressive symptoms may contribute to physical symptoms (and vice a versa). The comprehensive biopsychosocial-spiritual assessment will evaluate for pre-existing mood disorders and explore previous coping mechanisms.

Table 2.

Social Work Interventions/Referrals Addressing Physical Well-Being

| Interventions to Consider | Recommendations & Referrals to Explore |

|---|---|

|

|

Social workers bring a strengths-based perspective to their interactions and will assist the patient and FCG in reviewing how they have managed past difficulties. The social worker may find that instructing the patient or FCG in guided imagery or other relaxation techniques may help lessen anxiety or better manage the physical side effects of treatment. A chemotherapy class may be available that can help increase the patient and FCG’s sense of control. In addition, recommending a consultation to a dietician, physical therapist, a pain specialist or a palliative care service may be appropriate to optimize their quality of life, improve their physical tolerance and enhance adherence to treatment. If available, a lung cancer support group may be useful to improve coping, emotional regulation and increase problem solving skills. Support groups may be available in person or on-line and provide normalcy and anticipatory guidance. Social workers can provide health education, reiterate key medical messages and address myths or misconceptions related to treatment.

The oncology social worker met with Mr. and Mrs. J to explore their concerns in greater detail. She arranged to meet with them in a quiet and non-threatening environment. She reiterated the importance of taking cough medications as directed to minimize the discomforts of his dry cough. Mr. J stated that he was reluctant to “take more pills” and was concerned about “getting addicted” to medications. The social worker explored these concerns at length with the couple (and later alerted the healthcare team of Mr. J’s fears regarding medications), and she offered to teach Mr. J relaxation exercises to address his shortness of breath, which he found very helpful. The social worker noted the determination Mr. J had used when he quit smoking and encouraged him to see how these skills would be useful now in coping with his illness. She noted the strength of their relationship and obvious care for one another.

The social worker encouraged Mrs. J to follow up with her primary care physician regarding her chronic health issues, as she had not seen her healthcare providers in several years. Following an assessment of the couple’s health literacy level, the social worker provided educational materials that explained lung cancer and its treatment and encouraged them to contact her should they have further questions. She told them about support programs at the hospital, in their community and on-line that they might consider and offered anticipatory guidance regarding issues that they may soon experience – for example, she noted that Mrs. J was quite frail and explored the possibility of obtaining additional support in the home should Mr. J eventually require assistance with transfers.

Psychological Well Being

Table 3 highlights considerations in the management of the patient’s psychological well being. Patients are often referred to social work for ineffective coping, depressive mood or anxiety resulting in interference with their medical care. Social workers take this opportunity to explore both the patient’s and the FCG’s mental health history. The social worker assesses for underlying concerns and patterns of behavior that shed light on the overall distress they are experiencing. Identifying a history of mania, psychosis, panic attacks, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder or post traumatic stress disorder assists the team in creating a more robust plan for care and clarifying appropriate additional referrals.

Table 3.

Social Work Interventions/Referrals Addressing Psychological Well-Being

| Interventions to Consider | Recommendations & Referrals to Explore |

|---|---|

|

|

Patients with lung cancer may express guilt or regret if they had a history of smoking or confusion and anger if they were non-smokers. It is critical that the social worker be alert for signs of self deprecation, anger or depression. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques may prove an effective approach to managing unhelpful, negative recurring thoughts.

The social worker met with both Mr. and Mrs. J individually to explore more deeply the underlining causes of their distress. Mr. J said that his anxiety was related to the concern he had for his loving wife, asking: “what is she going to do without me?” Mrs. J reported that her primary worry was how she would be able physically and financially to provide the “proper care” for her husband. She explained that she has a history of depression and feels vulnerable that it may recur. Each had been reluctant to speak to the other regarding their concerns, resulting in increased anxiety and isolation.

With their permission, the social worker brought them together to assist the couple with clarifying their communication and normalize many of their concerns. She spoke with them about their children and encouraged them to bring their children to their upcoming medical appointment. She explained that it was important for the healthcare team to assist them in more fully understanding the seriousness of their parent’s conditions. Mrs. J was receptive to a referral to a caregiver support group and said that she looked forward to meeting with other FCGs to better learn how to manage her husband’s illness. They both agreed to meet with the social worker periodically to continue to explore their concerns about the future.

Social Well Being

Table 4 provides factors that may influence the social coping of a lung cancer patient. The social worker is skilled in viewing the patient from a “systems perspective” and seeing him or her as a whole person within a wider social network, with a range of strengths, competing obligations, treasured roles and often conflicting responsibilities. This perspective helps to build trust and rapport.

Table 4.

Social Work Interventions/Referrals Addressing Social Well-Being

| Interventions to Consider | Recommendations & Referrals to Explore |

|---|---|

|

|

A common concern of patients and FCGs is the struggle about how to talk with their children or grandchildren about cancer in a non-threatening way. Social workers and child life specialists may be invaluable resources to families regarding how best to communicate with others about their disease in a developmentally appropriate manner. Modeling open and transparent communication and providing information and resources tailored to each child’s learning needs can prove very helpful. The social worker can also assist the patient and FCG in their communications with the medical team. In today’s rushed clinical environment, it is important that patients maximize their time with their healthcare professionals. Socials workers can model and teach strong communication skills to empower patients with skills to improve their appointment experience.

Additionally, it is important to anticipate the practical struggles of a lung cancer diagnosis and help the patient and FCG plan and prepare for how they will cope and manage through treatment. Assisting the patient and FCG navigate through systems like employment, disability benefits and eligibility, transportation, help at home and financial concerns can have important consequences for the patient’s overall adaptive functioning. Discussing realistic expectations and role adjustments at home can help to organize conflicted families to make coordinated and appropriate decisions. The social worker needs to be prepared with tailored resources and referrals. Families may be unaware of how significantly cancer may change their family dynamics; scheduling time to discuss this may help improve their sense of control and reduce stress levels.

The social worker encouraged the Js to consider more openly communicating their concerns with their adult children and being more receptive to the possibility that they may want to become more involved in the patient’s care. Mr. J said that he missed being able to drive to see his son and helping him work on his new house. He was worried that because he was on treatment driving was probably “not a very good idea” and that he did not want to cause any additional worry for his wife. He was conflicted, as he saw that their increasing isolation was related to her more depressed mood. The social worker agreed to follow-up with the medical oncologist to see if in fact the patient had restrictions to his driving. The social worker also obtained their permission to refer the couple to a financial counselor who would assist them in seeing if they might be able to lower their co-pay for medications.

Clarifying that he was able to return to driving proved to be an important intervention, in that Mrs. J later admitted that they had also stopped going to church and she deeply missed the support of her friends there. The social worked stressed the importance of being socially active and explained the importance of staying connected with family, friends, and their church community. She used this opportunity to encourage Mr. and Mrs. J to each develop a self-care plan and explored strategies that each could use to enhance their well-being.

Spiritual Well Being

Table 5 highlights spiritual concerns commonly associated with cancer. It is not unusual for lung cancer patients to question their faith. Patients may struggle with existential concerns and meaning-making, questioning their identity, self image, or purpose in life. Engaging the patient or FCG in culturally congruent integrative therapies such as meditation, yoga or other healing arts may reduce stress. Consultation with or referral to a chaplain may be appropriate. An advance health care directive is a powerful tool in managing uncertainty and helplessness and allows patients to make their values and goals known to both their medical team and their family. Conversations regarding the completion of advance directives allow rich discussions regarding deeply held beliefs and values that can open doors to further communication regarding end-of-life and post-death concerns.

The social worker encouraged Mr. and Mrs. J to discuss what gives them meaning and purpose in life and to describe their spiritual beliefs. They spoke enthusiastically about their connectedness to their faith and their belief in God. The social worker informed them that chaplaincy was part of the interdisciplinary team and agreed to make a referral for chaplaincy support. Mrs. J was able to express how appreciative she was to have this opportunity to care for Mr. J and how meaningful this role has been for her.

In a subsequent meeting Mr. J agreed to explore the creation of an “ethical will” and to complete an advance directive. The social worker encouraged them to discuss Mr. J’s wishes regarding his end-of-life care with their children and supported him in creating a brief recording of his hopes and dreams for each of his grandchildren. As Mr. J’s illness progressed, the social worker and chaplain worked together to increase supportive services in the home, coordinating visits with community clergy, and setting the foundation for a referral to hospice.

Table 5.

Social Work Interventions/Referrals Addressing Spiritual Well-Being

| Interventions to Consider | Recommendations & Referrals to Explore |

|---|---|

|

|

Collaborative Communication

The complex and often interrelated concerns of lung cancer patients make collaborative communication vital, and social workers are well positioned to be system advocates for patient concerns. Team meetings offer an opportunity to explore patient needs and identify appropriate referrals and plan interventions. The social worker may serve as a consultant to the team and as the “voice of the patient” acting in the role of a culture broker between patients and healthcare providers. Palliative care services benefit from an active, engaged and dynamic collaboration of differing disciplines each committed to enhancing the well-being of patients and their families.

Summary and Discussion

The diagnosis of lung cancer is associated with a myriad of adverse symptoms impacting a patient’s and FCG’s quality of life physically, psychologically, socially and spiritually. The quality of life model and patient scenario illustrate the importance of a comprehensive and collaborative approach to care. Oncology social workers are key members of the interdisciplinary care team and their compassionate expertise is essential to address the multidimensional concerns commonly associated with cancer (Herman, 2011; Lockey, Benefiel & Meyer, 2011). The proactive delivery of culturally-congruent care with an early integration of a wide range of palliative services offers lung cancer patients and their caregivers an opportunity to maximize their quality of life and provides a more comprehensive person-centered focus of care (Ryan, Howell, Jones & Hardy, 2008).

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P01 CA136396.

The authors acknowledge the P01 team and wish to especially thank the patients and families who participated in this study in hope that their experiences would lead to improvements in the delivery of care.

Footnotes

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (Principal Investigator: Betty Ferrell, PhD, MA, FAAN, CHPN).

Contributor Information

Shirley Otis-Green, Senior Research Specialist, Division of Nursing Research & Education, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA.

Rupinder K. Sidhu, Oncology Social Worker, Division of Clinical Social Work, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA.

Catherine Del Ferraro, Senior Research Specialist, Division of Nursing Research and Education, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA.

Betty Ferrell, Professor & Director, Division of Nursing Research & Education, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA.

References

- Akin S, Can G, Aydiner A, Ozdilli K, Durna Z. Quality of life, symptom experience and distress of lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010;14(5):400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altilio T, Otis-Green S, Dahlin C. Applying the National Quality Forum Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care: A social work perspective. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life and Palliative Care. 2008;4(1):3–16. doi: 10.1080/15524250802071999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- City of Hope Pain & Palliative Care Resource Center. Quality of Life Models. Retrieved on 8/26/13: http://prc.coh.org/qual_life.asp.

- Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Woodruff JF, Palos GR, Richman SP, Lu C. Levels of symptom burden during chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer: Differences between public hospitals and a tertiary cancer center. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(21):2859–2865. doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.33.4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Koczywas M, Grannis F, Harrington A. Palliative care in lung cancer. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review] The Surgical Clinics of North America. 2011;91(2):403–417. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinami R, Otis-Green S, Klein L, Sidhu R, Ferrell B. Quality of life of family caregivers and challenges faced in caring for patients with lung cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2012;16(6):E210–220. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.E210-E220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Given BA, Given CW, Sherwood PR. Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2012;10(2):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, Sun V, Fujinami R, Sidhu R, Otis-Green S, Juarez G, Ferrell B. Family caregiver burden, skills preparedness, and quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013;40(4):337–346. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.337-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman C. Practice Perspectives. 1. Vol. 5. Washington, DC: NASW Press; 2011. Support for family caregivers: The national landscape and the social work role. [Google Scholar]

- Huhmann M, Camporeale J. Supportive care in lung cancer: clinical update. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2012;28(2):e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Delivering high quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John LD. Self-care strategies used by patients with lung cancer to promote quality of life. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010;37(3):339–347. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.339-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczywas M, Cristea M, Thomas J, McCarty C, Borneman T, Del Ferraro C, Ferrell B. Interdisciplinary palliative care intervention in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2013;14(6):736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao YC, Liao WY, Shun SC, Yu CJ, Yang PC, Lai YH. Symptoms, psychological distress, and supportive care needs in lung cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011;19(11):1743–1751. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Surawska H, Paice J, Baron SR. Communication about sexuality and intimacy in couples affected by lung cancer and their clinical-care providers. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):179–185. doi: 10.1002/pon.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockey AM, Benefiel D, Meyer M. The collaboration of palliative care and oncology social work. In: Altilio T, Otis-Green S, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Social Work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Grant L, Highet G, Sheikh A. Archetypal trajectories of social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing and distress in family care givers of patients with lung cancer: secondary analysis of serial qualitative interviews. British Medical Journal. 2010:340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. NASW Standards for Social Work Practice in Palliative and End of Life Care. 2004 Retrieved on 9/6/2013: http://www.socialworkers.org/practice/bereavement/standards/default.asp.

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 3. Pittsburgh, PA: 2013. Retrieved 8/22/13: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org. [Google Scholar]

- Otis-Green S. Palliative Care. In: Mullen EJ, editor. Oxford Bibliographies in Social Work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. Retrieved 8/22/13: http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195389678/obo-9780195389678-0158.xml?rskey=HhOvx8&result=81&q. [Google Scholar]

- Otis-Green S, Juarez G. Enhancing the social well-being of family caregivers. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2012;28(4):246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P, Howell V, Jones J, Hardy E. Lung cancer, caring for the caregivers. A qualitative study of providing pro-active social support targeted to the carers of patients with lung cancer. Palliative Medicine. 2008;22(3):233–238. doi: 10.1177/0269216307087145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch T. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Cancer Fact Sheet. Retrieved on 8/22/13: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html.

- Yount S, Beaumont J, Rosenbloom S, Cella D, Patel J, Hensing T, Abernethy AP. A brief symptom index for advanced lung cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2012;13(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]