Abstract

Aim

To evaluate associations between total serum GGT activity, metabolic risk factors and prevalent metabolic disease in MESA.

Patients & methods

Continuous associations between GGT and fasting blood glucose (FBG), fasting insulin, HbA1c and Homeostasis Model Assessment Index of Insulin Resistance (HOMA–IR) were evaluated in the entire MESA cohort and in metabolic disease subgroups using linear regression models incrementally adjusted for age, gender, site, race, lifestyle, traditional risk factors and medications. Cross-sectional odds of prevalent impaired FBG, metabolic syndrome and Type 2 diabetes were calculated for GGT quintiles in the entire cohort and in subgroups defined by age (< or ≥65 years) and ethnicity.

Results

In multivariable models, significant associations were present between GGT activity and FBG, fasting insulin, HbA1c and HOMA–IR, with the interaction between GGT and BMI affecting the association between GGT and HOMA–IR as well as the association between BMI and HOMA–IR (p < 0.0001). Adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs) of prevalent impaired FBG, metabolic syndrome and Type 2 diabetes for quintile 5 versus 1 in the entire cohort were 2.4 (1.7–3.5), 3.3 (2.5–4.5) and 2.8 (1.8–4.4), respectively (p < 0.0001). GGT associations weakened with age. The significance of linear trends for increased prevalent metabolic disease by increasing GGT quintile varied by ethnicity.

Conclusion

GGT is strongly associated with both cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, including prevalent metabolic disease, in the MESA cohort.

Keywords: γ-glutamyltransferase, GGT, glutathione, metabolic syndrome, oxidative stress, Type 2 diabetes

There has been a resurgence of interest in the enzyme GGT owing to the results of several observational studies identifying associations between graded elevations in its activity in serum and increased risk of adverse cardio vascular and metabolic outcomes, including metabolic syndrome (MetS) [1], Type 2 diabetes [2–7], hypertension [6,8], congestive heart failure [9] and vascular events [10,11], plus increased mortality from cardiovascular disease and diabetes [12,13].

A known physiologic function of GGT is to contribute to in vivo antioxidant homeostasis through recycling extracellular glutathione (GSH) and its precursor amino acids for intracellular reconversion to reduced GSH [14]. GGT and its relationship to redox balance in vivo has been thoroughly summarized by Whitfield [15], and several specific research findings provide a convincing rationale that increased GGT activity represents increased oxidative stress, including:

-

▪

GSH depletion appears to be a prerequisite condition to induce GGT [16];

-

▪

NADPH oxidase-produced reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species both induce GGT expression [17,18];

-

▪

Mitochondria of GGT-knockout mice have depleted GSH, increased reactive oxygen species formation, depleted energy stores and impaired oxidative phosphorylation (thus impaired ATP production), which can be attenuated by N-acetylcysteine, a GSH precursor [19];

-

▪

GGT-knockout mice die prematurely with complications associated with increased oxidative stress that can be attenuated with N-acetylcysteine [20].

Translating this hypothesis to research in humans, and further supporting a relationship between GGT and GSH, Sedda et al. demonstrated inverse associations between GGT activity and plasma total GSH concentration in people with established cardiovascular risk and, after multivariate adjustment for individual risk factors, male gender, the total number of risk factors present and plasma total GSH remained the only independent variables associated with GGT activity [21].

Commonly classified as a ‘liver enzyme’ associated with gall bladder disease, alcoholism and frank hepatitis, liver tissue GGT expression does not always correlate with serum GGT activity [22,23]. GGT is expressed in multiple human tissues other than the liver, with total serum GGT activity corresponding to the sum of activity from at least four fractions (i.e., small [s-GGT], medium [m-GGT], big [b-GGT] and free [f-GGT] GGT), patterns of which may identify the tissue sites of origin, as well as the nature of pathological changes [24–28]. However, despite the insights gained from fractionating GGT, the relationship between tissue GGT activity and serum GGT activity remains under active investigation.

As GSH depletion, and subsequent oxidative modification of cellular proteins, lipids and nucleotides, is implicated in the development of insulin resistance, impaired insulin production and the microvascular complications of diabetes [29–31], it is logical to question the relationship between increases in GGT activity and metabolic disease. Supporting a relationship in humans, Bonnet et al. demonstrated strong associations between human insulin resistance measured by euglycemic–hyperinsulinemic clamp and GGT activity [32]. However, additional data are needed from larger human cohorts regarding the relationships between GGT activity and specific risk factors with established prognostic value in metabolic disease, including the magnitude, direction and interdependency of any associations, as well as the generalizability of associations found in different ethnic groups.

Therefore, the objective of the current study was to evaluate cross-sectional associations between fasting serum GGT activity, individual metabolic risk factors (e.g., fasting blood glucose [FBG], fasting insulin [FI], HbA1c and insulin resistance) and prevalent disease (e.g., impaired FBG [IFG], MetS and Type 2 diabetes) in the MESA cohort. The MESA cohort was especially useful for this evaluation because it includes participants within a broad range of ages and metabolic risk statuses, plus unlike many other US cohorts, it allows for evaluations within age and ethnic subgroups because of robust representation from four ethnicities, that is, black, Chinese, Hispanic and white. If GGT activity is a valid, generalizable biomarker of metabolic disease severity, we would anticipate total serum GGT activity to be positively associated with risk factors and disease, proportional to the severity of disease (and thus to the hypothetical burden of oxidative stress), and generalizable across all vulnerable ethnic groups.

Patients & methods

This ancillary study to the parent MESA cohort was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington (WA, USA) as study #34269 prior to performing all study procedures and analyses.

Study population

The design and objectives of the MESA cohort study have been reported elsewhere [33]. Briefly, MESA consists of 6814 participants recruited from the general US population (53% female; 47% male) aged 44–84 years (mean: 62 years) representing four major ethnic groups, Chinese (n = 803), black (n = 1893), Hispanic (n = 1496) and white (n = 2622). All samples and data were collected during the baseline MESA examination (i.e., exam 1 performed July 2000–August 2002), except for HbA1c, which was measured in samples collected during MESA exam 2 (i.e., September 2002–February 2004).

Participant-reported questionnaires

Participant demographics, medical history including current medications and physical activity were collected using standardized forms during exam 1. Smoking status was recorded as current, former or never and pack-years calculated for former and current smokers. Alcohol use was categorized as former, current or never based on self-report and total intake was recorded as the number of standardized drinks (i.e., one beer, one glass of wine or one shot of spirits) per week. Total intentional exercise (MET-min/week) was calculated based on self-report over the previous month.

Clinical measurements

GGT

Using methods by Silber et al., a microplate assay was developed for measuring GGT activity based on changes in the absorption of p-nitroaniline at 405 nm read by an automated plate reader run at 37°C under specified conditions [34]. A total of 6783 frozen samples were available for GGT measurement (99.5% of the cohort). The assay was conducted at 23°C, had a detectable range of 0.274–199.8 U/l and a coefficient of variation (CV) <5%. In order to calibrate the microplate assay to routine clinical methods, 20 test samples were measured using an automated clinical instrument at the Fletcher Allen Health Care (FAHC) laboratory at the University of Vermont (VT, USA) and then repeated using the plate assay. A calibration equation was developed (GGTclinical = [2.034 × GGTplate] + 15.93; R2 = 0.98), and applied to all values measured using the microplate method. To confirm the calibration equation, GGT was remeasured in the original 20 test samples at the Collaborative Studies Clinical Laboratory at Fairview University Medical Center (MN, USA) and found similar to the FAHC data set (Pearson’s correlation = 0.99). Therefore, the original FAHC-calibrated data set was used for subsequent analyses.

Additional laboratory measures

Total cholesterol (TC) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were measured in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma using a cholesterol oxidase method on a COBAS FARA centrifugal analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, IN, USA); CV for TC and HDL cholesterol was 1.6 and 2.9%, respectively. Plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated by the Friedewald formula in specimens with triglycerides <400 mg/dl [35]. Plasma triglycerides were measured using Triglyceride GB reagent (Roche Diagnostics) on the Roche COBAS FARA centrifugal analyzer; CV = 4.0%. FBG was measured by rate reflectance spectrophotometry using a thin film adaptation of the glucose oxidase method on the VITROS® analyzer (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics, Inc., NY, USA); CV = 1.1%. FI was determined by radioimmunoassay using the Linco Human Insulin Specific RIA Kit (Linco Research, Inc., MO, USA); lower limit of sensitivity was 2 U/l and CV = 4.9%. HbA1c was measured on the Tosoh A1c 2.2 Plus Glycohemoglobin Analyzer (Tosoh Medics, Inc., CA, USA) using automated HPLC; CV = 1.4–1.9%. All measurements were performed at the Collaborative Studies Clinical Laboratory at Fairview University Medical Center. Homeostasis Model Assessment Index of Insulin Resistance (HOMA–IR) was calculated using FBG and FI according to Matthews et al., excluding insulin users [36].

Definitions of metabolic disease subgroups

IFG

Nondiabetic articipants were defined as having IFG if their FBG was ≥100 mg/dl but <126 mg/dl at their baseline visit [37].

MetS

Both National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the 2009 joint International Diabetes Federation (IDF)/NHLBI/American Heart Association (AHA)/International Athero sclerosis Society (IAS)/International Association for the Study of Obesity (IASO) (i.e., ‘2009 Joint’) definitions were used for MetS [38]. Participants were defined as having MetS if they met three or more of the standard criteria including: FBG ≥100 mg/dl or antidiabetic treatment, triglyceride ≥150 mg/dl or treatment, HDL <40 mg/dl for males or <50 mg/dl for females, blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg or blood pressure treatment, and/or increased waist circumference. For the NHLBI definition, waist circumference was defined as increased if ≥102 cm for males or ≥88 cm for females; gender- and ethnicity-specific thresholds were applied for the 2009 Joint definition [38]. As MESA is an ethnically diverse sample, we used the 2009 Joint definition in subsequent analyses because it includes ethnicity-specific thresholds for waist circumference. Participants were not classified as having MetS if they met criteria for Type 2 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes

Because HbA1c was not measured until exam 2, we defined Type 2 diabetes based on FBG ≥126 mg/dl [37], or if participants were taking insulin or oral diabetes medications at exam 1.

Statistical analyses

All skewed variables (i.e., GGT, glucose, insulin, triglycerides, HOMA–IR and HbA1c) were log-transformed for linear regression analyses. GGT data were divided into equal quintiles. Crude cross-sectional associations between GGT and individual demographic, lifestyle and risk variables were determined by calculating the mean value for each within GGT quintiles, and then applying an unadjusted linear regression model to determine the significance of linear trends across quintiles. Sequential multivariable linear regression models were developed to evaluate continuous associations between GGT and clinical metabolic risk variables, that is, FBG, FI, HbA1c and HOMA–IR, adjusted for hypothesized confounders. The first model (M1) adjusted for continuous age plus gender, ethnicity and study site as categorical variables. The second model (M2) added lifestyle covariates including categorical alcohol use (current/former/never), continuous drinks per week, continuous intentional exercise (MET-min/week) and categorical smoking (current/ former/never), plus continuous exposure as pack-years. The third model (M3) added traditional cardiovascular risk covariates including continuous measures of LDL, HDL, triglycerides, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and binary variables for diabetes medication, lipid-lowering medication and blood pressure medication, as well as family history of stroke and myocardial infarction. Waist circumference was added to M3 for HOMA–IR (M4HOMA). We also added BMI to the HOMA–IR model post hoc and tested for interaction with GGT based on previous findings of an interaction [3]. Users of exogenous insulin were omitted from all models. We tested for multiplicative interactions between continuous GGT and age and ethnicity; tests for interactions with age were specified a priori based on past findings [13], while tests for interactions with ethnicity were added post hoc as exploratory tests. Wald tests were applied to test for nonzero regression coefficients for each ethnic subgroup, and to test the equivalency of coefficients. All analyses were repeated within metabolically normal, MetS and Type 2 diabetes subgroups, and in subgroups defined by age < or ≥65 years.

The cross-sectional prevalence of metabolic disease was calculated and reported as the number of cases and proportion of the total cohort meeting each definition. The Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio of IFG, MetS and Type 2 diabetes were calculated within each quintile, adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, waist circumference and study site, and additional adjustment for alcohol, smoking and exercise. Statistical significance was determined for linear trends across all quintiles and for point estimates for odds of disease within each quintile. Analyses were repeated in subgroups defined by ethnicity and age < or ≥65 years. We also evaluated multiplicative interaction between GGT and age (specified a priori) and ethnicity (post hoc, exploratory).

Experimental results

Distribution of GGT

GGT activity was significantly different between males and females (p < 0.0001 for comparisons of log-transformed means by unpaired, two-sided t-test). Because neither liver ultrasound nor biopsy data were available in MESA, we included only GGT values <95th percentile for each gender in order to exclude extreme liver disease in our final data set (n = 6446), corresponding to an upper limit of 80.9 and 99.7 U/l for females and males, respectively. Gender-specific medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for the overall distribution of GGT were: 29.1 U/l (23.8–37.3.1 U/l) for females and 35.5 U/l (28.6–46.6 U/l) for males, with the median and IQR of the entire cohort equal to 31.8 U/l (25.8–41.8 U/l).

Prevalence of metabolic disease

We identified a considerable prevalence of metabolic disease within members of the MESA cohort. IFG and glucose-defined diabetes were present in 15.9 (n = 945) and 12.5% (n = 852) of participants, respectively. The prevalence of MetS was highly concordant between definitions (κ = 96%): NHLBI was 29.9% (n = 2038) and 2009 Joint was 28.4% (n = 1935). Individual components of MetS were highly prevalent at baseline, including increased waist circumference (62.9% per NHLBI and 62.2% per 2009 Joint definition), elevated blood pressure ≥135/85 or treatment (51.0%), low HDL cholesterol (34.3%), elevated triglycerides or treatment (28.6%) and glucose (15.9%).

Crude & adjusted cross-sectional associations between GGT, demographic, lifestyle & metabolic risk factors

In unadjusted analyses, positive trends were evident between increasing GGT activity and numerous demographic and lifestyle variables, including riskier profiles in each traditional risk category, except physical activity (Table 1). In adjusted analyses (Table 2), the positive associations remained strong between GGT activity and increased FBG, FI, HbA1c and HOMA–IR for the entire cohort, despite adjustment for demographic, lifestyle and traditional cardiovascular risk covariates. In post hoc tests, there was a strong interaction with BMI in estimating HOMA–IR from GGT (p < 0.0001). In each subgroup defined by metabolic status (normal, MetS and Type 2 diabetes), all associations remain strongly positive between individual risk factors and GGT activity in adjusted models through M3, except in the Type 2 diabetes subgroup in which associations with FBG and HbA1c were attenuated.

Table 1.

Trends between GGT and demographic, lifestyle and clinical risk variables.

| Baseline characteristics (n = 6446) |

GGT–Q1 (n = 1289) |

GGT–Q2 (n = 1286) |

GGT–Q3 (n = 1292) |

GGT–Q4 (n = 1289) |

GGT–Q5 (n = 1290) | p-value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 62.4 (10.9) | 63.5 (10.3) | 62.8 (10.0) | 62.1 (10.0) | 61.0 (9.7) | <0.0001 |

| Age <65 years, n (%) | 699 (54) | 647 (50) | 686 (53) | 726 (56) | 804 (62) | Referent |

| Age ≥65 years, n (%) | 590 (46) | 639 (50) | 606 (47) | 563 (47) | 486 (38) | <0.0001 |

| Male/female, n (%) | 325 (25)/964 (75) | 523 (41)/763 (59) | 635 (49)/657 (51) | 724 (56)/565 (44) | 840 (65)/450 (35) | <0.0001 |

| Ethnicity: | ||||||

| White, n (%) | 665 (52) | 543 (42) | 465 (36) | 435 (36) | 408 (32) | Referent |

| Chinese, n (%) | 194 (15) | 173 (13) | 164 (13) | 123 (13) | 119 (9) | 0.66 |

| Black, n (%) | 226 (18) | 308 (24) | 389 (30) | 430 (33) | 395 (31) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 204 (16) | 262 (20) | 274 (20) | 301 (23) | 368 (29) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking status: | ||||||

| Never, n (%) | 746 (58) | 663 (52) | 695 (54) | 615 (48) | 533 (41) | Referent |

| Past, n (%) | 432 (34) | 483 (38) | 435 (34) | 498 (39) | 525 (41) | <0.0001 |

| Current, n (%) | 105 (8) | 135 (11) | 159 (12) | 172 (13) | 228 (18) | <0.0001 |

| Pack-years (current or past smokers, excludes never), mean (SD) | 21.1 (23.2) | 21.6 (21.6) | 24.8 (27.1) | 23.4 (25.5) | 24.5 (33.7) | 0.02 |

| Current alcohol, mean (SD) | 699 (71) | 669 (68) | 672 (66) | 719 (66) | 782 (71) | 0.34 |

| Drinks/week, mean (SD) | 2.4 (3.7) | 3.5 (5.1) | 3.5 (5.1) | 4.4 (6.8) | 5.9 (8.0) | <0.0001 |

| Total intentional exercise (MET-min/week), mean (SD) | 1499 (2131) | 1529 (2286) | 1548 (2196) | 1558 (2580) | 1609 (2841) | 0.75 |

| Glucose (mg/dl), median (IQR)† | 85.0 (80–91) | 88.0 (82–95) | 91.0 (84–100.5) | 92.0 (85–103) | 93.0 (86–106) | <0.0001 |

| Insulin (µU/l), median (IQR)† | 3.8 (2.7–5.5) | 4.8 (3.3–7.2) | 5.6 (3.8–8.6) | 6.2 (4.1–9.4) | 7.1 (4.4–11.1) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c (%), median (IQR)† | 5.4 (5.1–5.6) | 5.5 (5.2–5.8) | 5.5 (5.2–5.9) | 5.6 (5.3–6.0) | 5.6 (5.3–6.1) | <0.0001 |

| HOMA–IR, median (IQR)† | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 1.6 (1.0–2.7) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 91.9 (14.3) | 96.2 (14.3) | 99.0 (14.0) | 101.1 (13.8) | 101.4 (13.4) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes medications: | ||||||

| None, mean (SD) | 1218 (94) | 1184 (92) | 1159 (89) | 1150 (89) | 1124 (87) | Referent |

| Insulin, mean (SD) | 11 (1) | 19 (2) | 20 (2) | 21 (2) | 33 (3) | 0.001 |

| Oral, mean (SD) | 60 (5) | 83 (6) | 113 (9) | 118 (9) | 133 (10) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 192.0 (32.6) | 192.8 (35.7) | 193.5 (35.3) | 195.3 (34.8) | 196.8 (37.6) | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 114.1 (29.4) | 116.6 (31.1) | 118.3 (31.0) | 119.6 (31.9) | 118.7 (32.5) | <0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 56.7 (15.3) | 52.4 (15.5) | 49.4 (14.1) | 48.4 (13.3) | 48.0 (13.8) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides, median (IQR)† | 94.0 (68–127) | 104.0 (74–146) | 111.0 (78–158) | 119.0 (83–174) | 132.0 (89–191) | <0.0001 |

| Lipid medications, mean (SD) | 171 (13) | 210 (16) | 216 (17) | 234 (18) | 218 (17) | 0.03 |

| SBP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 121.9 (21.6) | 125.7 (22.0) | 127.7 (21.7) | 128.1 (21.0) | 129.2 (20.5) | <0.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 68.3 (10.0) | 70.4 (9.9) | 72.4 (10.1) | 74.4 (10.1) | 73.9 (10.2) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (≥140/90 or treatment), mean (SD) | 466 (36) | 531 (41) | 591 (46) | 642 (50) | 650 (50) | <0.0001 |

Q1: <4.5 U/l; Q2: 24.5–29.3 U/l; Q3: 29.3–35.1 U/l; Q4: 35.1–45.2 U/l; Q5: 45.2–99.7 U/l.

Skewed variable.

DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; HOMA–IR: Homeostasis Model Assessment Index of Insulin Resistance; IQR: Interquartile range; Q: Quintile; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; SD: Standard deviation.

Table 2.

Adjusted associations between GGT and metabolic risk factors, overall and in metabolic disease subgroups.

| Metabolic subgroup risk variable |

Entire (n = 6446) | Normal (n = 3783) | MetS (n = 1935) | Diabetes (n = 852) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βAdj. × ln(GGT) (95%CI) |

p-value | βAdj. × ln(GGT) (95%CI) |

p-value | βAdj. × ln(GGT) (95%CI) |

p-value | βAdj.. × ln(GGT) (95%CI) |

p-value | |

| FBG (mg/dl) | ||||||||

| M1 | 0.11 (0.10–0.13) | <0.0001 | 0.03 (0.026–0.04) | <0.0001 | 0.04 (0.03–0.06) | <0.0001 | 0.13 (0.07–0.20) | <0.0001 |

| M2 | 0.11 (0.10–0.13) | <0.0001 | 0.03 (0.02–0.04) | <0.0001 | 0.04 (0.02–0.06) | 0.001 | 0.13 (0.02–0.23) | 0.02 |

| M3 | 0.07 (0.05–0.09) | <0.0001 | 0.03 (0.02–0.04) | <0.0001 | 0.05 (0.02–0.07) | <0.0001 | 0.05 (−0.05–0.15) | 0.34 |

| FI (µU/l) | ||||||||

| M1 | 0.53 (0.49–0.57) | <0.0001 | 0.39 (0.34–0.44) | <0.0001 | 0.38 (0.31–0.45) | <0.0001 | 0.42 (0.28–0.55) | <0.0001 |

| M2 | 0.55 (0.50–0.60) | <0.0001 | 0.40 (0.38–0.47) | <0.0001 | 0.38 (0.28–0.47) | <0.0001 | 0.45 (0.25–0.65) | <0.0001 |

| M3 | 0.39 (0.34–0.44) | <0.0001 | 0.33 (0.27–0.39) | <0.0001 | 0.38 (0.28–0.47) | <0.0001 | 0.47 (0.27–0.67) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c(%) | ||||||||

| M1 | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) | <0.0001 | 0.02 (0.008–0.02) | <0.0001 | 0.04 (0.02–0.05) | <0.0001 | 0.03 (−0.01–0.08) | 0.13 |

| M2 | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | <0.0001 | 0.02 (0.008–0.02) | <0.0001 | 0.02 (0.003–0.04) | 0.02 | 0.04 (−0.02–0.11) | 0.18 |

| M3 | 0.04 (0.03–0.05) | <0.0001 | 0.01 (0.004–0.02) | 0.004 | 0.02 (0.002–0.04) | 0.03 | 0.04 (−0.03–0.11) | 0.26 |

| HOMA–IR | ||||||||

| M1 | 0.64 (0.60–0.69) | <0.0001 | 0.43 (0.37–0.48) | <0.0001 | 0.42 (0.35–0.50) | <0.0001 | 0.55 (0.41–0.69) | <0.0001 |

| M2 | 0.66 (0.60–0.72) | <0.0001 | 0.44 (0.37–0.51) | <0.0001 | 0.42 (0.31–0.52) | <0.0001 | 0.57 (0.36–0.79) | <0.0001 |

| M3 | 0.47 (0.41–0.52) | <0.0001 | 0.36 (0.29–0.43) | <0.0001 | 0.42 (0.32–0.53) | <0.0001 | 0.52 (0.30–0.73) | <0.0001 |

| M4HOMA | 0.37 (0.32–0.42) | <0.0001 | 0.28 (0.22–0.34) | <0.0001 | 0.39 (0.29–0.48) | <0.0001 | 0.43 (0.24–0.62) | <0.0001 |

FBG, FI, HbA1c, HOMA–IR and GGT are log transformed. All models exclude insulin users. Regression coefficient units for FBG, FI, HbA1c and HOMA–IR are 10 mg glucose/unit GGT activity, mU insulin/unit GGT activity, %HbA1c/unit GGT activity and 1/unit GGT activity, respectively. M1 adjusts for age, gender, ethnicity and study site. M2 represents M1 plus alcohol use (current/former/never and drinks/week) plus exercise (MET-min/week) plus smoking (current/former/never and pack-years). M3 represents M2 plus lipids (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides), lipid-lowering medications, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, antihypertensive medications, diabetes medications, and family history of heart attack or stroke. M4HOMA represents M3 plus waist circumference.

βAdj.: Regression coefficient for GGT in adjusted models; FBG: Fasting blood glucose; FI: Fasting insulin; HOMA–IR: Homeostasis Model Assessment Index of Insulin Resistance; MetS: Metabolic syndrome.

There was no evidence of an interaction between ethnicity and continuous GGT in M3 for FBG, FI or HOMA–IR models. However, there was an interaction with race/ethnicity in estimating HbA1c from GGT, in that Hispanics had a different association than the other race/ethnic groups (p < 0.0001; Wald: p = 0.006 and 0.19). A significant interaction was evident between continuous age and continuous GGT in FI and HOMA–IR models (p ≤ 0.004 for both); however, the interaction was attenuated in M4HOMA with adjustment for waist circumference. Continuous interaction with age in ethnic subgroups was apparent only in the white subgroup for FI and HOMA–IR models (p < 0.05 for both), although was similarly attenuated in M4HOMA (p = 0.12). Although there were no significant interactions between continuous age and GGT for adults <65 years, there were significant interactions with age in estimating FI, HbA1c and HOMA–IR models from GGT (p = 0.001–0.006), in that adults <65 years had different association than adults <65 years, which remained significant in M4HOMA (p = 0.008). The negative β-coefficients on this interaction variable indicate the adjusted associations between GGT and metabolic risk factors generally weaken as age increases beyond 65 years.

Odds of prevalent metabolic disease by GGT quintile

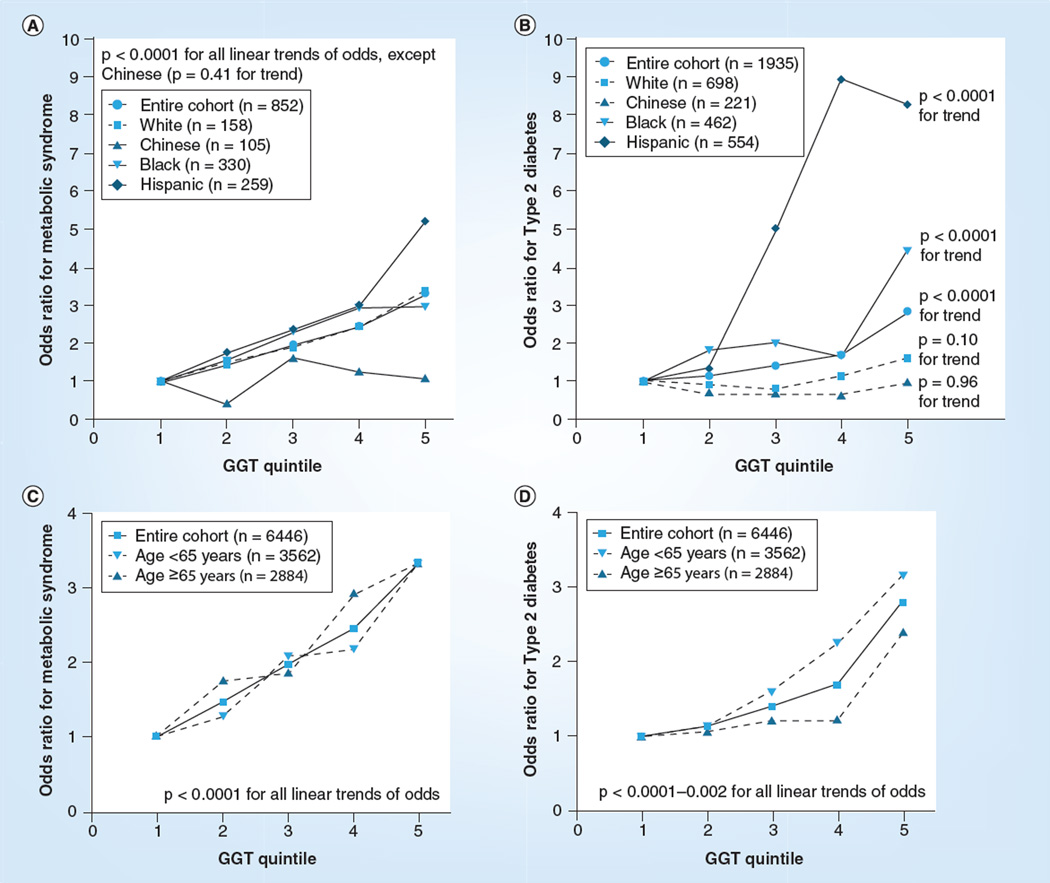

Prevalent metabolic disease increased significantly across GGT quintiles in the entire cohort (Table 3). Strong associations were observed for the entire cohort and in ethnic subgroups for minimally adjusted models including age, gender and study site (p < 0.0001–0.01 for linear trends; data not shown). However, several associations were attenuated in models adding adjustment for lifestyle variables (i.e., alcohol use, smoking and exercise). Figure 1A & 1B provides graphical representations of the odds of MetS and Type 2 diabetes by GGT quintile in ethnic subgroups. In general, linear trends for increased disease by quintile remained significant, except in the Chinese subgroup in which trends were attenuated for all outcomes. The trend also became borderline for IFG in the black subgroup (p = 0.05) and for Type 2 diabetes in the white subgroup (p = 0.10).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios of metabolic disease by GGT quintile in the entire MESA cohort and stratified by ethnic groups.

| Metabolic subgroup |

GGT–Q1, prevalence |

GGT–Q2, OR† (95% CI); p-value‡; prevalence |

GGT–Q3, OR† (95% CI); p-value‡; prevalence |

GGT–Q4, OR† (95% CI); p-value‡; prevalence |

GGT–Q5, OR† (95% CI); p-value‡; prevalence |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend |

Interaction with ethnicity |

||||||

| Impaired fasting blood glucose | |||||||

| All ethnicities (n = 872) | n = 90 | 1.05 (0.71–1.58); 0.79; n = 131 | 1.62 (1.11–2.37); 0.01; n = 192 | 2.09 (1.44–3.04); <0.0001; n = 229 | 2.40 (1.65–3.48); <0.0001; n = 230 | <0.0001 | – |

| White (n = 272) | n = 34 | 1.26 (0.71–2.24); 0.43; n = 39 | 1.83 (1.04–3.21); 0.04; n = 60 | 2.76 (1.61–4.74); <0.0001; n = 70 | 2.68 (1.54–4.66); 0.001; n = 69 | <0.0001 | Referent |

| Chinese (n = 130) | n = 22 | 0.65 (0.20–2.16); 0.48; n = 22 | 1.31 (0.48–3.86); 0.62; n = 32 | 1.16 (0.38–3.55); 0.79; n = 24 | 1.18 (0.39–3.61); 0.77; n = 30 | 0.52 | 0.84 |

| Black (n = 248) | n = 17 | 1.58 (0.66–3.78); 0.31; n = 41 | 1.45 (0.62–3.40); 0.39; n = 56 | 2.15 (0.96–4.84); 0.06; n = 79 | 1.76 (0.75–4.16); 0.20; n = 55 | 0.15 | 0.72 |

| Hispanic (n = 222) | n = 17 | 0.55 (0.20–1.52); 0.25; n = 29 | 1.65 (0.71–3.85); 0.25; n = 44 | 1.60 (0.68–3.78); 0.28; n = 56 | 3.27 (1.43–7.43); 0.005; n = 76 | <0.0001 | 0.45 |

| Metabolic syndrome | |||||||

| All ethnicities (n = 1151) | n = 154 | 1.47 (1.09–1.99); 0.01; n = 210 | 1.97 (1.47–2.65); <0.0001; n = 246 | 2.46 (1.83–3.30); <0.0001; n = 256 | 3.31 (2.46–4.46); <0.0001; n = 285 | <0.0001 | – |

| White (n = 466) | n = 76 | 1.53 (1.03–2.29); 0.04; n = 97 | 1.92 (1.27–2.91); 0.002; n = 97 | 2.45 (1.63–3.70); <0.0001; n = 90 | 3.39 (2.24–5.14); <0.0001; n = 106 | <0.0001 | Referent |

| Chinese (n = 127) | n = 22 | 0.44 (0.12–1.56); 0.21; n = 25 | 1.64 (0.52–5.17); 0.40; n = 32 | 1.27 (0.39–4.19); 0.69; n = 26 | 1.08 (0.30–3.87); 0.90; n = 22 | 0.41 | 0.34 |

| Black (n = 229) | n = 24 | 1.57 (0.76–3.26); 0.22; n = 29 | 2.30 (1.16–4.56); 0.017; n = 56 | 2.92 (1.50–5.69); 0.002; n = 70 | 2.97 (1.46–6.03); 0.003; n = 50 | <0.0001 | 0.83 |

| Hispanic (n = 329) | n = 32 | 1.75 (0.88–3.49); 0.11; n = 59 | 2.38 (1.23–4.63); 0.01; n = 61 | 2.99 (1.53–5.85); 0.001; n = 70 | 5.19 (2.68–10.03); <0.0001; n = 107 | <0.0001 | 0.30 |

| Type 2 diabetes | |||||||

| All ethnicities (n = 781) | n = 73 | 1.14 (0.70–1.86); 0.61; n = 120 | 1.42 (0.86–1.86); 0.15; n = 168 | 1.71 (1.09–2.70); 0.02; n = 182 | 2.81 1.80–4.39); <0.0001; n = 238 | <0.0001 | – |

| White (n = 158) | n = 22 | 0.93 (0.46–1.92); 0.84; n = 26 | 0.81 (0.37–1.77); 0.60; n = 28 | 1.16 (0.57–2.38); 0.68; n = 35 | 1.62 (0.80–3.25); 0.18; n = 38 | 0.10 | Referent |

| Chinese (n = 105) | n = 17 | 0.69 (0.17–2.78); 0.60; n = 23 | 0.69 (0.18–2.61); 0.59; n = 17 | 0.67 (0.18–2.49); 0.55; n = 17 | 0.97 (0.28–3.34); 0.96; n = 22 | 0.96 | 0.46 |

| Black (n = 330) | n = 15 | 1.83 (0.75–4.44); 0.18; n = 45 | 2.01 (0.85–4.71); 0.11; n = 74 | 1.67 (0.72–3.91); 0.23; n = 65 | 4.44 (1.93–10.21); <0.0001; n = 104 | <0.0001 | 0.21 |

| Hispanic (n = 259) | n = 19 | 1.38 (0.24–7.90); 0.72; n = 26 | 4.96 (1.09–22.6); 0.04; n = 49 | 8.93 (2.02–39.38); 0.004; n = 65 | 8.28 (1.87–36.54); 0.005; n = 74 | <0.0001 | 0.09 |

Q1: <24.5 U/l (referent group); Q2: 24.5–29.3 U/l; Q3: 29.3–35.1 U/l; Q4: 35.1–45.2 U/l; Q5: 45.2–99.7 U/l.

Adjusted for age, gender, waist circumference, study site, alcohol, smoking and exercise, plus ethnicity in the entire cohort.

p-value corresponds to the point estimate for odds of disease within each quintile.

OR: Odds ratio; Q: Quintile.

Figure 1. Odd ratios of metabolic disease by GGT quintile in subgroups defined by ethnicity and age.

(A) Demonstrates odds of metabolic syndrome by GGT activity quintile, in ethnic subgroups and in the entire cohort; (B) demonstrates odds of Type 2 diabetes by GGT activity quintile, in ethnic subgroups and in the entire cohort; (C) demonstrates odds of metabolic syndrome by GGT activity quintile, in subgroups defined by age <65 or ≥65 year and in the entire cohort; (D) demonstrates odds of Type 2 diabetes by GGT activity quintile, in subgroups defined by age <65 or ≥65 years and in the entire cohort.

The significance of the point estimates for increased odds of IFG, MetS and Type 2 diabetes was also greatly attenuated with adjustment for lifestyle variables, especially in the Chinese subgroup, which demonstrated no significant increases in prevalent disease by quintile. For prevalent IFG, the odds of disease were also attenuated in the white, black and Hispanic subgroups in all but the fifth quintile for the white and Hispanic subgroups. In all ethnic subgroups except the Chinese, the odds of MetS increased with GGT quintile, generally reached statistical significance in the third quintile. In general, point estimates for increased odds of Type 2 diabetes increased with GGT quintile, becoming statistically significant only in the fifth quintile, except for Hispanic cases, who reached significance in the third quintile. No interaction between GGT and ethnicity was evident for metabolic disease outcomes in models adjusted for age, gender, study site and lifestyle variables. Odds of diabetes, but not MetS, were consistently greater in for those aged <65 years compared with those aged ≥65 for each quintile, although linear trends remained strong in both subgroups for both outcomes (Figure 1C & 1D).

Discussion

GGT activity is strongly associated with individual and composite cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in the MESA cohort. The observed increases in prevalent metabolic diseases across GGT quintiles are highly consistent with our unadjusted analyses demonstrating positive associations between GGT and ‘riskier’ profiles for nearly every individual risk variable. The results of our multivariable analysis suggest the associations between GGT and individual metabolic risk factors, especially FI and HOMA–IR, are very stable and remain independent of standard clinical measures and lifestyle variables. Similar to previous reports, we measured a significant interaction between GGT, BMI and HOMA–IR, and weaker associations in adults >65 years of age [3,13]. As these associations are so consistent, strongly significant and relatively independent of ethnic group, we suggest total serum GGT activity as a continuous generalizable biomarker of composite metabolic risk in those adults without clinically evident vascular disease, with particular utility in people under the age of 65 years, even after considering differences in established demographic, behavioral and clinical risk factors.

Although several previous investigators have demonstrated strong associations between GGT activity and both cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, our report is novel in several important ways. This is the first evaluation of GGT activity in MESA, a very well-executed cohort study with excellent data quality. Additionally, we have carefully evaluated both individual and composite risk factors, in one study, systematically controlling first for demographics in our models, followed by lifestyle variables, and then including traditional risk factors to determine the independence of any observed relationships. We also evaluated associations in four ethnic subgroups simultaneously in a cohort with sufficient power to do so. Finally, replication research is valuable, and in this case, we clearly confirm previously reported relationships between GGT and individual cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, while also reporting strong, independent, residual association with composite risk.

This investigation is also strengthened by the fact that the MESA cohort includes an ethnically diverse sample of adults in the USA, and contains rich data on potential confounders. This combination allowed us to differentiate the prevalence of metabolic disease between ethnic subgroups, and detect potential meaningful ethnic differences. To our knowledge, our research provides evidence of GGT activity-associated metabolic risk in the largest known sample of Hispanics that has been reported. MESA also allowed for well-powered tests for interaction between GGT and ethnicity, which we did not detect upon adjustment for lifestyle covariates. The apparent differences in associations between GGT and odds of metabolic disease within ethnic subgroups deserve future investigation, although residual confounding due to lifestyle differences remains likely.

Notably, the values of GGT activity reported here are higher than have been reported in other cohorts. Although this difference may be due to methodological variability, that is, using a research assay compared with a clinical assay, and differences in assay temperature, our plate assay was validated by two separate clinical laboratories. Rather than assay methodology, we suggest that the primary differences in the GGT range measured for this cohort are attributable to the greater than average non-white representation in the MESA cohort, combined with the high prevalence of metabolic risk. Table 1 demonstrates the association between black and Hispanic ethnicity and GGT activity, which account for 28 and 22% of the cohort respectively, that is, 50% of the total cohort. Regarding the prevalence of metabolic risk factors, increased waist circumference was highly prevalent in participants (i.e., 62.9% per NHLBI and 62.2% per 2009 Joint definition), as was elevated blood pressure ≥135/85 or treatment (51.0%), low HDL cholesterol (34.3%), elevated triglycerides or treatment (28.6%), and elevated glucose (15.9%). Combined, we suggest these differences resulted in a higher than expected mean GGT activity than would be expected in a ‘healthy’ cohort.

Methods for measuring subfractions of total GGT activity (i.e., s-GGT, m-GGT, b-GGT and f-GGT) have been reported by Franzini et al. [24], and disease-specific patterns of GGT subfractions and ratios of subtypes are emerging, for example, increased b-GGT has recently been associated with cardiovascular risk [27], whereas s-GGT was increased in alcoholics [39]. Our research is limited by not having this GGT subfraction data, which should be applied in future studies to better differentiate subgroups within larger cohorts by disease status, including those with isolated hepatic disease and those with multiorgan disease, that is, concomitant nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic disease and cardiovascular disease. This innovative method of GGT subfractionation will also be critical in future determinations of the organ-specific mechanisms responsible for observed increases in serum GGT activity. Despite the potential to improve upon our methods by subfractionating GGT, the associations demonstrated here with total serum GGT activity remain valid. Other studies have demonstrated that participants with increased total serum GGT activity have increased GGT subfractions more associated with disease (i.e., non-f-GGT fractions), total serum GGT activity increased with increases in each subfraction (i.e., except f-GGT) and total serum GGT activity remains the most accessible biomarker to clinicians [26,27,39].

Although we accounted for many confounders, including smoking and alcohol intake, previous research has also identified associations between GGT and exposures unaccounted for in this study, including environmental pollutants [40] and dietary factors [41]. Our findings are also limited due to their cross-sectional design. Future research to evaluate associations between GGT activity, dietary factors and incident disease is planned in the MESA cohort. Our study is also limited by not having ALT data available to evaluate whether similar trends exist between ALT and the metabolic risk factors evaluated in our research, and to potentially adjust for other causes of liver disease. However, previous reports do not support the hypothesis that ALT is associated with cardiovascular outcomes in the same manner as GGT activity, as demonstrated in a recent meta-analysis by Fraser et al. [11]. Fraser et al. have also demonstrated GGT as a better predictor of incident diabetes, compared with ALT [7]. Similarly, analyses by Lim et al. do not demonstrate associations between ALT and dietary antioxidant intake, as have been demonstrated with GGT activity [42]. These findings suggest differential causes of ALT and GGT activity elevation; however, we are unable to confirm this hypothesis in the present study.

Given the importance of redox balance to cellular metabolism in all tissues, it is conceivable that total GGT activity is a biomarker of multiorgan GSH depletion, whereas increases in tissue-specific GGT activity subfractions suggesting chronic tissue-specific GSH depletion. Extending this research may even result in the ability to differentiate isolated liver, kidney and vascular disease, as well as chronic diseases with multiple affected organs (i.e., Type 2 diabetes). If this differentiation is confirmed by additional experimental research, it would fill an important research gap in population-based cohort studies [43].

Conclusion

The data presented in this study, combined with the accumulation of past evidence, support total serum GGT activity as a significant biomarker of cardiovascular and metabolic risk, including strong associations with established individual risk factors of vascular disease, plus composite risk conditions including MetS and Type 2 diabetes. The established role of GGT in GSH homeostasis supports the need for translational investigations of the behavioral and environmental causes of increased GGT activity in humans, including triggers, regulators and more precise understanding of its relationship to GSH status in single- and multi-organ pathology.

Future perspective

Despite decades of basic science research supporting an oxidative stress-based theory of vascular disease and aging, experimental research on ‘antioxidant’ therapies has been disappointing. A contributor to these disappointing findings is a lack of valid biomarkers to determine an individual’s current burden of oxidative stress, and thus to identify individuals who may respond to targeted antioxidant therapies and/or behavioral approaches to reduce exposure to increased oxidative stress; for example, dietary change. In the future, GGT may be validated as a biomarker of oxidative stress relevant in cardiovascular and metabolic disease. GGT is a prime candidate biomarker for this role due to its parallel functions in recycling GSH to meet intracellular antioxidant needs, as well as for hepatic conjugation reactions of xenobiotics, including lipid peroxides and persistent organic pollutants. Relative increases of GGT activity, within a range now considered clinically normal, might be used to identify people who are at risk for metabolic disease and who are candidates for antioxidant therapy, dietary changes and/or priority individuals for reducing medications and environmental pollutants that require GSH for conjugation. Further fractionation of GGT will help identify tissue sites of injury, and will improve clinicians’ ability to differentiate multiorgan pathology from site-organ pathology. Our current research results clearly demonstrate the validity of total serum GGT activity as a biomarker for increased metabolic risk, even within values now considered clinically normal. Future research will identify the specific contributors to total and tissue-specific increases GGT activity, including the relative contributions of exogenous oxidants versus endogenous redox dysregulation. Additional research is needed to determine priority interventions for GGT lowering. In the future, GGT lowering will be considered a clinical goal, similar to LDL lowering, and subsequent lowering of GGT will reduce the risk for incident cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Executive summary.

GGT activity & its association with riskier cardiovascular risk profiles

-

▪

Cross-sectional associations demonstrate strong, positive relationships between GGT activity and male gender, higher risk ethnic subgroups, age, smoking history, waist circumference, low-density lipoprotein, triglyceride level, blood pressure and use of medications for diabetes, hypertension and cholesterol. Negative associations were evident for high-density lipoprotein level.

GGT activity & its associations with metabolic risk factors after adjustment for demographics, lifestyle factors & traditional risk factors

-

▪

Multivariable linear regression models demonstrated positive and significant cross-sectional associations between GGT activity and fasting blood glucose (FBG), fasting insulin, HbA1c and the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA–IR).

-

▪

Linear regression models adjusting for age, gender, study site, ethnicity, alcohol intake, smoking, physical activity, medications and traditional cardiovascular risk factors remained significant for FBG, insulin, HbA1c and HOMA–IR.

-

▪

Associations with FBG, insulin, HbA1c and HOMA–IR were significant in participants without metabolic disease, as well as in those with prediabetes and metabolic syndrome.

-

▪

Associations with insulin and HOMA–IR remained significant in those participants with Type 2 diabetes.

GGT activity & odds of prevalent metabolic syndrome & Type 2 diabetes

-

▪

Odds of prevalent metabolic syndrome and Type 2 diabetes increased significantly with increasing quintiles of GGT activity.

GGT activity & its relationship to ethnicity & age

-

▪

Significant trends for increased prevalent metabolic disease were evident in all ethnic groups (i.e., white, black and Hispanic), except the Chinese.

-

▪

An age greater than 65 years reduced the strength of the associations between GGT activity and disease risk.

Conclusion

-

▪

Total serum GGT activity is strongly and positively associated with increased composite metabolic risk in this large cohort of mixed ethnicity adults without symptomatic cardiovascular disease.

-

▪

Future observational and clinical translational research is necessary to determine the exact relationship between total serum GGT activity and the availability of reduced glutathione and other antioxidants to further validate GGT as a biomarker of oxidative stress.

-

▪

Future clinical translational research is necessary to determine the exact culprits for increasing GGT activity in vivo, as well as environmental, behavioral and medical approaches to reduce oxidative stress.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to especially thank R Tracy from the Fletcher Allen Health Care (FAHC) laboratory at the University of Vermont (VT, USA) and M Steffes from the Collaborative Studies Clinical Laboratory at Fairview University Medical Center (MN, USA) for their assistance with the measurement and calibration of GGT.

This research was made possible by contracts N01-HC-95159–95166 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and 1KL2RR025015 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Author contributions

R Bradley and DR Jacobs Jr researched the data, performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. D-H Lee and AL Fitzpatrick assisted with the analysis plan, and reviewed/edited the manuscript. NS Jenny developed the GGT measurement assay and reviewed the manuscript.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Liu CF, Zhou WN, Fang NY. γ-glutamyltransferase levels and risk of metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012;66(7):692–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre P, Balkau B, Born C, et al. Three-year increase of γ-glutamyltransferase level and development of Type 2 diabetes in middle-aged men and women: the D.E.S.I.R. cohort. Diabetologia. 2006;49(11):2599–2603. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0418-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim JS, Lee DH, Park JY, et al. A strong interaction between serum γ-glutamyltransferase and obesity on the risk of prevalent Type 2 diabetes: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Clin. Chem. 2007;53(6):1092–1098. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.079814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meisinger C, Löwel H, Heier M, et al. Serum γ-glutamyltransferase and risk of Type 2 diabetes mellitus in men and women from the general population. J. Intern. Med. 2005;258(6):527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen QM, Srinivasan SR, Xu JH, et al. Elevated liver function enzymes are related to the development of prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes in younger adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(12):2603–2607. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onat A, Can G, Örnek E, et al. Serum γ-glutamyltransferase: independent predictor of risk of diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and coronary disease. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(4):842–848. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser A, Harris R, Sattar N, et al. Alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyltransferase, and incident diabetes: the British women's heart and health study and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(4):741–750. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu CF, Gu YT, Wang HY, et al. γ-glutamyltransferase level and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e48878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH, Shaper AG, Lennon L, Sattar N. γ-glutamyltransferase, hepatic enzymes, and risk of incident heart failure in older men. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32(3):830–835. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.240457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meisinger C, Döring A, Schneider A, et al. Serum γ-glutamyltransferase is a predictor of incident coronary events in apparently healthy men from the general population. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189(2):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser A, Harris R, Sattar N, et al. γ-glutamyltransferase is associated with incident vascular events independently of alcohol intake: analysis of the British women’s heart and health study and meta-analysis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27(12):2729–2735. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.152298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase and γ-glutamyltransferase and mortality in the United States population. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(2):477.e11–485.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DH, Buijsse B, Steffen L, et al. Association between serum γ-glutamyltransferase and cardiovascular mortality varies by age: the Minnesota heart survey. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2009;16(1):16–20. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32830aba5c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dickinson DA, Forman HJ. Glutathione in defense and signaling: lessons from a small thiol. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2002;973:488–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04690.x. ▪ Provides extensive background on the importance of glutathione in maintaining normal redox balance, and thus normal physiology.

- 15. Whitfield JB. Gamma glutamyl transferase. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2001;38(4):263–355. doi: 10.1080/20014091084227. ▪▪ Provides extensive basic science data regarding the function of GGT and its role as a biomarker of disease.

- 16.Braide SA. A requirement for low concentration of hepatic glutathione for induction of gammaglutamyltransferase by phenobarbitone. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 1989;9(5–6):429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huseby NE, Asare N, Wetting S, et al. Nitric oxide exposure of CC531 rat colon carcinoma cells induces γ-glutamyltransferase which may counteract glutathione depletion and cell death. Free Radic. Res. 2003;37(1):99–107. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000036434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravuri C, Svineng G, Pankiv S, et al. Endogenous production of reactive oxygen species by the NADPH oxidase complexes is a determinant of γ-glutamyltransferase expression. Free Radic. Res. 2011;45(5):600–610. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.564164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Will Y, Fischer KA, Horton RA, et al. Gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase-deficient knockout mice as a model to study the relationship between glutathione status, mitochondrial function, and cellular function. Hepatology. 2000;32(4 Pt 1):740–749. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chevez-Barrios P, Wiseman AL, Rojas E, et al. Cataract development in γ-glutamyl transpeptidase-deficient mice. Exp. Eye Res. 2000;71(6):575–582. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sedda V, De Chiara B, Parolini M, et al. Plasma glutathione levels are independently associated with γ-glutamyltransferase activity in subjects with cardiovascular risk factors. Free. Radic. Res. 2008;42(2):135–141. doi: 10.1080/10715760701836821. ▪▪ Provides support for the understanding that serum GGT activity is inversely, and independently, related to reduced glutathione status.

- 22.Satoh T, Takenaga M, Kitagawa H, et al. Microassay of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase in needle biopsies of human liver. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1980;30(1):151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selinger MJ, Matloff DS, Kaplan MM. γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity in liver disease: serum elevation is independent of hepatic GGTP activity. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1982;125(3):283–290. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(82)90258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Franzini M, Bramanti E, Ottaviano V, et al. A high performance gel filtration chromatography method for γ-glutamyltransferase fraction analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2008;374(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.10.025. ▪ Reports methods for GGT fractionation, which will likely be the future direction of research on GGT and its activity.

- 25.Franzini M, Corti A, Fornaciari I, et al. Cultured human cells release soluble γ-glutamyltransferase complexes corresponding to the plasma b-GGT. Biomarkers. 2009;14(7):486–492. doi: 10.3109/13547500903093757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franzini M, Fornaciari I, Fierabracci V, et al. Accuracy of b-GGT fraction for the diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2012;32(4):629–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Franzini M, Fornaciari I, Rong J, et al. Correlates and reference limits of plasma γ-glutamyltransferase fractions from the Framingham Heart Study. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2013;417:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.12.002. ▪▪ Provides evidence that the tissue site of oxidative stress may be discernable by GGT fractionation and identifying disease-specific patterns of GGT fraction, in this case cardiovascular disease.

- 28.Paolicchi A, Emdin M, Passino C, et al. β-lipoprotein- and LDL-associated serum γ-glutamyltransferase in patients with coronary atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186(1):80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54(6):1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, et al. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: a unifying hypothesis of Type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2002;23(5):599–622. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertson R, Zhou H, Zhang T, et al. Chronic oxidative stress as a mechanism for glucose toxicity of the beta cell in Type 2 diabetes. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2007;48(2–3):139–146. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonnet F, Ducluzeau PH, Gastaldelli A, et al. Liver enzymes are associated with hepatic insulin resistance, insulin secretion, and glucagon concentration in healthy men and women. Diabetes. 2011;60(6):1660–1667. doi: 10.2337/db10-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002;156(9):871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silber PM, Gandolfi AJ, Brendel K. Adaptation of a γ-glutamyl transpeptidase assay to microtiter plates. Anal. Biochem. 1986;158(1):68–71. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90590-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(Suppl. 1):S11–S63. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; Hational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Association for the Study of Obesity. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franzini M, Fornaciari I, Vico T, et al. High-sensitivity β-glutamyltransferase fraction pattern in alcohol addicts and abstainers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127(1–3):239–242. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee DH, Jacobs DR. Is serum β-glutamyltransferase a marker of exposure to various environmental pollutants? Free Radic. Res. 2009;43(6):533–537. doi: 10.1080/10715760902893324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee DH, Steffen LM, Jacobs DR. Association between serum β-glutamyltransferase and dietary factors: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;79(4):600–605. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim JS, Yang JH, Chun BY, et al. Is serum β-glutamyltransferase inversely associated with serum antioxidants as a marker of oxidative stress? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;37(7):1018–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mayne ST. Antioxidant nutrients and chronic disease: use of biomarkers of exposure and oxidative stress status in epidemiologic research. J. Nutr. 2003;133(Suppl. 3):S933–S940. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.933S. ▪▪ Provides excellent background on the strengths and limitations of ‘oxidative stress’ biomarkers recently applied to population cohort studies.