Abstract

Background

Although prior studies have shown disparities in maternal health behaviors according to race/ethnicity and acculturation, whether these patterns are evident among new immigrant populations remains unclear.

Purpose

To examine the associations among proxies of acculturation and maternal smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding initiation within each major ethnic group in Massachusetts.

Methods

Data were from the Standard Certificate of Live Births on 1,067,375 babies by mothers from 31 ethnic groups for 1996–2009. Mothers reported whether they smoked during pregnancy and the birth facility recorded whether mothers started breastfeeding. The acculturation proxy combined mothers’ country of birth and language preference: U.S.-born, foreign-born English-speaking, and foreign-born non-English speaking. For each ethnic group, adjusted logistic regression models were conducted to examine associations between the acculturation proxy and whether mothers smoked or initiated breastfeeding. Data were analyzed from 2012 to 2013.

Results

A lower proportion of foreign-born mothers had a high school degree or private insurance than U.S.-born mothers. However, foreign-born mothers who were English (range of AORs=0.07–0.93) or non-English speakers (AORs=0.01–0.36) were less likely to smoke during pregnancy than their U.S.-born counterparts. Foreign-born mothers who were English (AORs=1.22–6.52) or non-English speakers (AORs=1.35–10.12) were also more likely to initiate breastfeeding compared to U.S.-born mothers, except for some mothers with Asian ethnicities.

Conclusions

The consistency of the associations of being foreign-born with less smoking and more breastfeeding suggests that for the majority of ethnic groups studied, acculturation in the U.S. results in poorer maternal health behaviors.

Introduction

Although the benefits of breastfeeding and detrimental health effects of smoking during pregnancy to both mothers and infants are well known,1,2 the proportion of mothers who achieve public health recommendations for these health behaviors varies widely by maternal race/ethnicity.1,3,4 To date, most studies have used the standard Federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Directive No. 15 race/ethnicity categories to identify health disparities. White and Hispanic mothers are more likely to start and continue breastfeeding than black mothers,3,5 and white mothers are more likely to smoke during pregnancy than black and Hispanic mothers.4,6 Mothers from other ethnic groups are usually either combined into an “Other” category or excluded from analyses owing to insufficient sample sizes.5,6 However, the extent of the heterogeneity within the standard OMB race/ethnicity categories and the public health implications remain largely unknown.

Maternal health behaviors also vary by mothers’ country of birth, duration of residence in the U.S., and language preference.7–15 These three factors have been described in the literature as proxies of acculturation, the adoption of cultural elements and health-related norms and behaviors of the new dominant culture.16–18 Research from the U.S. has demonstrated that foreign-born mothers are less likely to smoke during pregnancy and more likely to start breastfeeding than their native-born counterparts or U.S.-born white mothers.7–9,12–15 Duration in the U.S. among foreign-born mothers or preference for English has also been associated with poorer health behaviors.10–12 However, most studies on acculturation have focused on Hispanic mothers10–13,16,18 and less is known as to whether these patterns are also evident across other ethnic groups, particularly those from new immigrant populations.

The demographic shift in the characteristics of mothers giving birth in the U.S. over recent decades19 has also been seen in Massachusetts. Between 1998 and 2009, there was a 70% increase in the proportion of births to Asian mothers and nearly a 40% increase in the proportion of births to black and Hispanic mothers.20,21 Over this same time period, the percentage of births to foreign-born mothers increased from 18% to 27%.20,21 In comparison, based on the 2006–2010 American Community Survey, only 13% of the population in Massachusetts was foreign-born.22 Therefore, better understanding of the sociodemographic characteristics of new mothers may provide insight into the future population and their health needs.

Massachusetts has been collecting information on mothers’ detailed ethnicity on the birth certificate for more than 15 years.23 On the parent worksheet, mothers indicate one category that best describes their ancestry or ethnic heritage among 39 choices. Although national monitoring of maternal smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding initiation as recorded on the birth certificate were introduced in 1989 and 2003, respectively, both health behaviors have been collected in Massachusetts since 1987. Data from the birth certificate present a unique opportunity to investigate maternal health behaviors by country of birth and language preference, particularly among rapidly growing minority populations that are often under-represented in surveys. The study aim was to examine the associations of acculturation proxies with maternal smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding initiation for each major ethnic group in Massachusetts.

Methods

Study Population

Information on all live births in Massachusetts was obtained from the Registry of Vital Records and Statistics for 1996–2009. The 1989 Revision of the Standard Certificate of Live Birth consists of a Parent Worksheet for Birth Certificates, which contains legal and sociodemographic information on the child’s mother and father. The parent(s) are required to complete the legal portion of the Parent Worksheet in order to accurately capture how they want their child’s birth certificate to appear. The birth certificate also contains a Hospital Worksheet for Birth Certificates, which is completed by a designated hospital representative (e.g., doctor, nurse, or hospital birth registrar) who reports on prenatal care, labor and delivery, neonatal conditions and procedures, and discharge.

Of the 1,090,471 live births in Massachusetts, 1,067,375 births were included in the analyses. Birth certificates were excluded if information was missing on maternal smoking during pregnancy (2,954); breastfeeding initiation (6,491); ethnicity (4,467); education (5,086); age (8); marital status (44); plurality (5); parity (5,222); delivery source of payment (4,191); place of birth (1,153); language preference (2,923); or if the language preference was American Sign Language (378). Mothers were also excluded if they were U.S.-born and non-English speakers (7,001) because sample sizes were insufficient to examine by maternal ethnicity.

Outcome Measures

The two main outcomes of interest were maternal smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding initiation. Mothers reported the number of cigarettes smoked on an average day during this pregnancy. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was dichotomized into yes (≥1 cigarettes/day) or no (none). The discharge portion of the hospital worksheet asks: Is mother breastfeeding? and the certifier of the worksheet responds either yes or no. This response was used as an indicator for mothers initiating breastfeeding.

Proxy Measure of Acculturation

On the parent worksheet, mothers reported their state or country of birth and their language preference for reading or discussing health-related materials from 14 categories. A three-category proxy of acculturation, hereafter “acculturation,” was created: U.S.-born (continental U.S., Alaska, and Hawaii); foreign-born English-speaking; and foreign-born non-English-speaking. Because historic patterns of breastfeeding in Puerto Rico are different from those in the continental U.S.,24 mothers who reported their ethnicity as Puerto Rican were coded as either U.S.-born or foreign born (Puerto Rico or another country). A similar rubric was used for mothers who were born in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Guam. For ethnic groups with fewer than 125 mothers in the foreign-born non-English-speaking category (Table 1), the indicator was dichotomized as U.S.-born or foreign-born.

Table 1.

Maternal ethnicity by an indicator of acculturation, 1996–2009, n (%) unless otherwise noted

| Maternal ethnicity | Total n | U.S.-born (n=790,422) |

Foreign-born English- speaking (n=170,257) |

Foreign-born non-English speaking (n=106,696) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | 43,117 | 40,897 (95) | 2,141 (5) | 79 (0.2) |

| Native American | 3,582 | 3,386 (95) | 188 (5) | 8 (0.2) |

| Other American | 495,986 | 486,812 (98) | 9,089 (2) | 85 (0.02) |

| Puerto Rican | 58,483 | 29,469 (50) | 18,073 (31) | 10,941 (19) |

| Dominican | 23,544 | 3,586 (15) | 7,459 (32) | 12,499 (53) |

| Mexican | 5,843 | 1,489 (26) | 1,273 (22) | 3,081 (53) |

| Colombian | 4,637 | 436 (9) | 1,479 (32) | 2,722 (59) |

| Salvadoran | 11,617 | 383 (3) | 1,768 (15) | 9,466 (82) |

| Other Central American | 12,719 | 905 (7) | 2,749 (22) | 9,065 (71) |

| Other South American | 6,687 | 697 (10) | 2,879 (43) | 3,111 (47) |

| Other Hispanic/Latina | 2,951 | 1,618 (55) | 561 (19) | 772 (26) |

| Haitian | 14,798 | 926 (6) | 8,499 (57) | 5,373 (36) |

| Jamaican | 4,052 | 434 (11) | 3,597 (89) | 21 (0.5) |

| Other West Indian/Caribbean | 5,116 | 1,428 (28) | 3,530 (69) | 158 (3) |

| Cape Verdean | 11,500 | 4,304 (37) | 3,855 (34) | 3,341 (29) |

| Brazilian | 21,101 | 372 (2) | 5,162 (25) | 15,567 (74) |

| Other Portuguese | 17,925 | 11,215 (63) | 5,649 (32) | 1,061 (6) |

| European | 202,408 | 170,801 (84) | 26,614 (13) | 4,993 (3) |

| Lebanese | 3,881 | 1,246 (32) | 2,058 (53) | 577 (15) |

| Other Middle Eastern | 7,862 | 1,797 (23) | 4,162 (53) | 1,903 (24) |

| Nigerian | 2,454 | 109 (4) | 2,239 (91) | 106 (4) |

| Other African | 12,058 | 368 (3) | 9,576 (79) | 2,114 (18) |

| Asian Indian | 14,481 | 635 (4) | 12,690 (88) | 1,156 (8) |

| Chinese | 18,525 | 2,150 (12) | 9,353 (51) | 7,022 (38) |

| Vietnamese | 10,142 | 368 (4) | 4,954 (49) | 4,820 (48) |

| Cambodian | 7,696 | 1,392 (18) | 3,804 (49) | 2,500 (33) |

| Korean | 4,433 | 527 (12) | 2,904 (66) | 1,002 (23) |

| Filipino | 3,110 | 652 (21) | 2,337 (75) | 121 (4) |

| Japanese | 2,533 | 370 (15) | 1,327 (52) | 836 (33) |

| Other Asian/Pacific Islander | 7,423 | 1,215 (16) | 4,792 (65) | 1,416 (19) |

| Other | 26,711 | 20,435 (77) | 5,496 (21) | 780 (3) |

Note: N=1,067,375.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Information about maternal sociodemographic characteristics and the pregnancy were collected on both worksheets. The parent worksheet instructs, Please mark one category that best describes the mother’s ancestry or ethnic heritage, and 39 options are listed, including several write-in options. This ethnicity question is separate from the maternal place of birth question (state or country). Mothers from the eight categories with 1,800 women or fewer were included in the relevant “Other” category (e.g., Barbadian mothers were re-categorized as Other West Indian/Caribbean). As defined by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, mothers who reported their race as black and ethnicity as American (4,989 mothers) were recoded as African American ethnicity.21 Other American mothers were defined as non-black and non-Hispanic who considered their ethnicity to be American. The parent worksheet also instructs, Please mark one category that best describes the mother’s race, and white, black, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, and Other are listed. The maternal race and ethnicity questions were combined to construct the standard OMB categories.23 Mothers also indicated their age, marital status, and highest level of education at the time of birth. On the hospital worksheet, the certifier reported the plurality of the birth, number of previous live births, date prenatal care started, mode of delivery, and source of payment for the delivery.

Statistical Analysis

Percentages represent the proportion of mothers in that category for all years of data. First, maternal sociodemographic characteristics were compared across the three categories of acculturation. Logistic regression models were then conducted, separately for each ethnic group, examining the association between acculturation and whether mothers smoked during pregnancy. Foreign-born English-speaking mothers and foreign-born non-English-speaking mothers were separately compared with U.S.-born mothers, the reference group. The associations were examined before and after adjusting for the following sociodemographic characteristics: maternal education, age, marital status, plurality, parity, delivery source of payment, timing of prenatal care, and year of birth (indicating year of delivery). Year was included in all models to account for the decreasing nationwide time trend in smoking during pregnancy,4,25 increasing time trend in breastfeeding,26 and changing demographics.20,21 For ethnic groups with cell sizes of <10 for not smoking, models were adjusted only for maternal age, marital status, and year of birth. Adjusted logistic regression models were repeated to examine the association between acculturation and breastfeeding initiation. The models were also adjusted for mode of delivery (vaginal versus cesarean birth). These two sets of analyses were repeated using the standard OMB race/ethnicity categories. Analyses were conducted from 2012 to 2013 using Stata, version 12.1 SE (StataCorp LP, College Station TX). The IRB at Boston College reviewed the study and considered it exempt.

Results

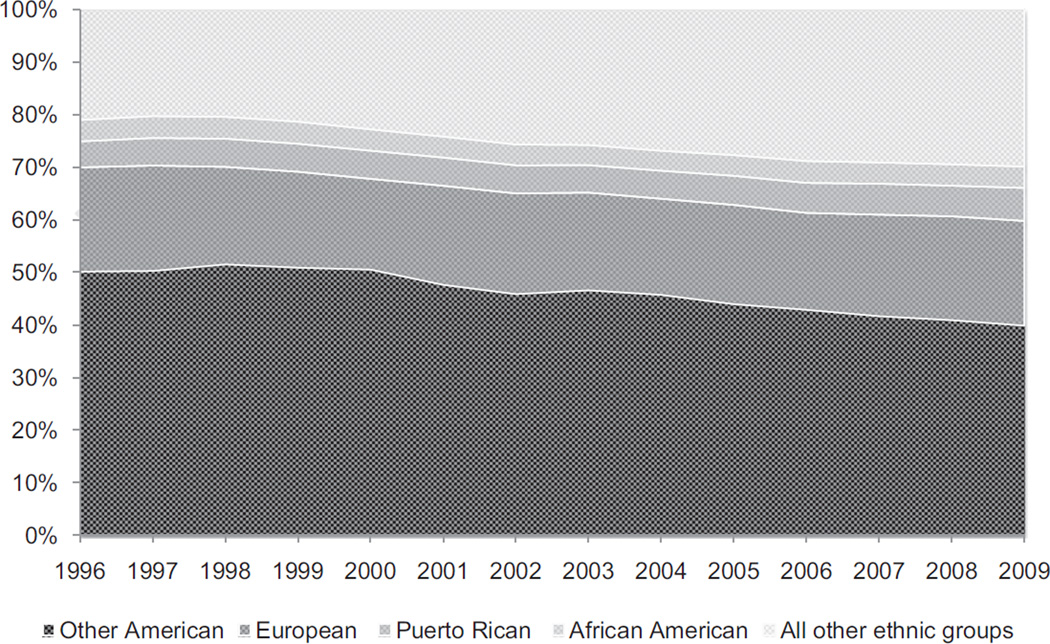

Table 1 illustrates the cultural diversity in Massachusetts and the distribution of mothers’ acculturation across the 31 ethnic groups. The four ethnic groups of African Americans, Other Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Europeans made up approximately 75% of the population. Figure 1 shows that the proportion of births by Other American mothers decreased from 50% to 40% from 1996 through 2009, whereas births by European and African American mothers remained stable at around 20% and 4%, respectively. In contrast, the proportion of births among Puerto Rican mothers increased from 5% to 6%, and that of all other ethnic groups from 21% to 30%.

Figure 1.

Proportion of births by maternal ethnicity in Massachusetts, 1996–2009

Overall, U.S.-born mothers had more advantaged socioeconomic circumstances than foreign-born English- speaking mothers, who in turn had more advantaged circumstances than foreign-born non-English-speaking mothers (Table 2). The largest differences across groups were in maternal education and the source of payment for the delivery. Approximately 32% of U.S.-born mothers had a high school education or less compared to 37% of foreign-born English speakers and 71% of foreign-born non-English speakers. Likewise, there was a gradient in the source of payment for delivery across the three groups. Approximately 23% of U.S.-born mothers had their delivery paid for by public sources compared to 35% of foreign-born English speakers and 69% of foreign-born non-English speakers. A higher proportion of foreign-born non-English-speaking mothers were younger, not married, had three or more children, and started their prenatal care in the second or third trimester than mothers from the other groups.

Table 2.

Maternal sociodemographic characteristics by an indicator of acculturation, n (%)

| Maternal characteristics |

U.S.-born (n=790,422) |

Foreign-born English-speaking (n=170,257) |

Foreign-born non-English-speaking (n=106,696) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal education | |||

| < High school | 59,834 (8) | 16,727 (10) | 35,566 (33) |

| High school graduate | 191,900 (24) | 46,041 (27) | 40,388 (38) |

| Some college | 194,123 (25) | 37,410 (22) | 14,797 (14) |

| College graduate | 226,371 (29) | 41,540 (24) | 10,332 (10) |

| More than college | 118,194 (15) | 28,539 (17) | 5,613 (5) |

| Age at birth | |||

| M (SE) | 29.8 (0.01) | 29.6 (0.01) | 28.3 (0.02) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 573,027 (73) | 123,858 (73) | 63,096 (59) |

| Not married | 217,395 (28) | 46,399 (27) | 43,600 (41) |

| Delivery source of payment | |||

| Private | 598,392 (76) | 108,339 (64) | 31,061(29) |

| Public | 183,027 (23) | 59,402 (35) | 73,635 (69) |

| Other | 9,003 (1) | 2,516 (2) | 2,000 (2) |

| Parity | |||

| First birth | 350,709 (44) | 77,788 (46) | 44,935 (42) |

| Second birth | 273,333 (35) | 58,309 (34) | 35,195 (33) |

| Third birth or higher | 166,380 (21) | 34,160 (20) | 26,566 (25) |

| Timing of prenatal care | |||

| First trimester | 675,026 (85) | 135,518 (80) | 75,463 (71) |

| Second trimester | 93,878 (12) | 27,090 (16) | 23,557 (22) |

| Third trimester | 15,722 (2) | 6,102 (4) | 6,325 (6) |

| None | 2,636 (0.3) | 519 (0.3) | 461 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 3,160 (0.4) | 1,028 (0.6) | 890 (0.8) |

Although the proportion of mothers who smoked during pregnancy or started breastfeeding varied across the ethnic groups, the pattern of engaging in poorer health behaviors by mothers’ acculturation was consistent for nearly all ethnic groups. Foreign-born mothers who were English (range of AORs=0.07–0.93) or non-English speakers (AORs=0.01–0.36) were less likely to smoke during pregnancy than their U.S.-born counter-parts (Table 3). In general, foreign-born non-English-speaking mothers had the lowest prevalence of smoking during pregnancy, foreign-born English-speaking mothers had intermediate prevalence, and U.S.-born mothers had the highest. This pattern of results suggests a gradient across mothers’ acculturation. The strongest gradients were seen in the Portuguese-speaking ethnic groups of Cape Verdean, Brazilian, and Other Portuguese mothers. For example, compared with U.S.-born Cape Verdean mothers, the ORs for smoking among foreign-born English and non-English speakers were 0.13 (95% CI=0.11, 0.16) and 0.01 (95% CI=0.01, 0.02), respectively.

Table 3.

AORs of maternal smoking during pregnancy by an indicator of acculturation for each maternal ethnic group

| Maternal ethnicity | % smoked during pregnancy | Foreign-born English-speaking AOR (95% CI)a,b |

Foreign-born non- English-speaking AOR OR (95% CI)a,b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.- born |

Foreign-born English-speaking |

Foreign-born non- English-speaking |

|||

| African American | 14 | 2 | 0.17 (0.13, 0.23) | ||

| Native American | 29 | 9 | 0.48 (0.28, 0.84) | ||

| Other American | 13 | 5 | 0.43 (0.39, 0.47) | ||

| Puerto Rican | 15 | 9 | 8 | 0.54 (0.51, 0.58) | 0.36 (0.33, 0.39) |

| Dominican | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0.22 (0.18, 0.28) | 0.09 (0.07, 0.12) |

| Mexican | 7 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.16 (0.09, 0.28) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.06) |

| Colombian | 7 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.19 (0.10, 0.38) | 0.06 (0.03, 0.13) |

| Salvadoran | 5 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.11 (0.05, 0.25) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) |

| Other Central American | 8 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.15 (0.10, 0.23) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) |

| Other South American | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0.36 (0.24, 0.53) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.18) |

| Other Hispanicc | 9 | 4 | 1 | 0.58 (0.36, 0.95) | 0.14 (0.07, 0.28) |

| Haitian | 4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.25 (0.16, 0.39) | 0.12 (0.07, 0.22) |

| Jamaican | 6 | 2 | 0.22 (0.13, 0.37) | ||

| Other West Indian/Caribbeanc | 10 | 2 | 3 | 0.21 (0.15, 0.28) | 0.25 (0.09, 0.68) |

| Cape Verdean | 20 | 4 | 0.7 | 0.13 (0.11, 0.16) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) |

| Brazilian | 19 | 2 | 3 | 0.11 (0.08, 0.15) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.15) |

| Other Portuguese | 16 | 11 | 7 | 0.58 (0.52, 0.65) | 0.19 (0.15, 0.25) |

| European | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0.56 (0.52, 0.60) | 0.16 (0.13, 0.20) |

| Lebanese | 11 | 2 | 3 | 0.12 (0.08, 0.19) | 0.10 (0.05, 0.19) |

| Other Middle Eastern | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 (0.11, 0.26) | 0.16 (0.10, 0.27) |

| Nigerianc | 4 | 0.3 | 0.05 (0.01, 0.26) | ||

| Other African | 13 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.07 (0.04, 0.11) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.13) |

| Asian Indianc | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.52 (0.15, 1.75) | 0.11 (0.01, 1.11) |

| Chinese | 2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.09 (0.05, 0.16) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.06) |

| Vietnamese | 5 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.37 (0.19, 0.72) | 0.18 (0.08, 0.38) |

| Cambodian | 14 | 5 | 2 | 0.65 (0.49, 0.86) | 0.26 (0.17, 0.41) |

| Koreanc | 5 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.93 (0.57, 1.51) | 0.28 (0.12, 0.66) |

| Filipino | 8 | 2 | 0.27 (0.16, 0.45) | ||

| Japanesec | 8 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.16 (0.08, 0.33) | 0.10 (0.04, 0.27) |

| Other Asian/Pacific Islanderc | 11 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.17 (0.12, 0.24) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.15) |

| Otherc | 13 | 4 | 0.6 | 0.35 (0.30, 0.41) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.13) |

Adjusted for maternal education, age, marital status, plurality, parity, delivery source of payment, prenatal care, and year of birth

Ref group: U.S.-born

Adjusted for maternal age, marital status, and year of birth

Similar results were observed for breastfeeding initiation, except for some mothers with Asian ethnicities (Table 4). For the majority of ethnic groups, foreign-born mothers who were English (AORs=1.22–6.52) or non-English speakers (AORs=1.35–10.12) were more likely to initiate breastfeeding compared to U.S.-born mothers, indicating a gradient in breastfeeding similar to that for smoking. Among Chinese and Vietnamese mothers, however, foreign-born non-English speakers were less likely to initiate breastfeeding than their U.S.-born counterparts.

Table 4.

AORs of breastfeeding initiation by an indicator of acculturation for each maternal ethnic group

| Maternal ethnicity | % breastfeeding initiation | Foreign-born English-speaking AOR (95% CI)a,b |

Foreign-born non- English-speaking AOR (95% CI)a,b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.- born |

Foreign-born English-speaking |

Foreign-born non- English-speaking |

|||

| African American | 65 | 87 | 2.72 (2.38, 3.10) | ||

| Native American | 66 | 86 | 1.70 (1.09, 2.65) | ||

| Other American | 71 | 87 | 2.27 (2.13, 2.42) | ||

| Puerto Rican | 62 | 70 | 70 | 1.51 (1.45, 1.58) | 1.77 (1.68, 1.86) |

| Dominican | 82 | 88 | 89 | 1.63 (1.45, 1.83) | 2.17 (1.93, 2.43) |

| Mexican | 82 | 92 | 92 | 2.23 (1.72, 2.89) | 3.48 (2.76, 4.39) |

| Colombian | 85 | 92 | 93 | 1.80 (1.27, 2.55) | 3.07 (2.15, 4.40) |

| Salvadoran | 89 | 90 | 94 | 1.22 (0.83, 1.79) | 2.06 (1.42, 2.99) |

| Other Central American | 78 | 91 | 91 | 2.65 (2.13, 3.29) | 3.70 (3.02, 4.54) |

| Other South American | 84 | 92 | 92 | 2.21 (1.71, 2.86) | 2.65 (2.03, 3.47) |

| Other Hispanic/ Latina | 72 | 89 | 91 | 3.03 (2.21, 4.17) | 5.15 (3.78, 7.02) |

| Haitian | 82 | 86 | 89 | 1.72 (1.41, 2.10) | 2.57 (2.07, 3.19) |

| Jamaican | 81 | 87 | 1.95 (1.46, 2.59) | ||

| Other West Indian/ Caribbean | 78 | 88 | 93 | 2.09 (1.75, 2.49) | 3.97 (2.09, 7.56) |

| Cape Verdean | 61 | 84 | 89 | 3.57 (3.19, 4.00) | 7.03 (6.06, 8.15) |

| Brazilian | 66 | 93 | 96 | 6.52 (5.06, 8.41) | 10.12 (7.88, 12.99) |

| Other Portuguese | 51 | 51 | 52 | 1.25 (1.16, 1.34) | 2.04 (1.77, 2.36) |

| European | 81 | 90 | 93 | 2.26 (2.16, 2.36) | 4.39 (3.93, 4.92) |

| Lebanese | 75 | 90 | 90 | 3.25 (2.59, 4.08) | 3.66 (2.61, 5.15) |

| Other Middle Eastern | 84 | 94 | 95 | 2.75 (2.25, 3.36) | 4.15 (3.16, 5.46) |

| Nigerian | 83 | 92 | 2.37 (1.27, 4.44) | ||

| Other African | 72 | 92 | 94 | 3.15 (2.42, 4.11) | 4.90 (3.55, 6.77) |

| Asian Indian | 95 | 96 | 93 | 1.39 (0.93, 2.08) | 1.22 (0.76, 1.97) |

| Chinese | 90 | 91 | 73 | 1.01 (0.85, 1.20) | 0.78 (0.65, 0.93) |

| Vietnamese | 73 | 71 | 58 | 0.86 (0.65, 1.12) | 0.73 (0.55, 0.96) |

| Cambodian | 54 | 56 | 44 | 1.25 (1.07, 1.45) | 0.97 (0.81, 1.17) |

| Korean | 89 | 92 | 94 | 1.21 (0.85, 1.71) | 1.61 (1.04, 2.50) |

| Filipino | 85 | 90 | 1.41 (1.06, 1.87) | ||

| Japanese | 91 | 96 | 97 | 1.49 (0.88, 2.50) | 2.00 (1.08, 3.70) |

| Other Asian/Pacific Islander | 74 | 87 | 80 | 1.53 (1.27, 1.85) | 1.35 (1.07, 1.70) |

| Other | 71 | 90 | 91 | 3.02 (2.73, 3.33) | 5.34 (4.13, 6.92) |

Adjusted for maternal education, age, marital status, plurality, parity, delivery source of payment, prenatal care, mode of delivery, and year of birth

Ref group: U.S.-born

Both sets of analyses were repeated using the standard OMB race/ethnicity categories (Supplemental Table). Foreign-born mothers who were English (AORs=0.10–0.44) or non-English speakers (AORs=0.03–0.12) were less likely to smoke during pregnancy than their U.S.- born counterparts. A similar pattern was seen for breastfeeding initiation, except for some Asian/Pacific Islander mothers. For the remaining racial/ethnic groups, foreign-born mothers who were English (AORs=1.16–3.09) or non-English speakers (AORs=3.75–7.76) were more likely to initiate breastfeeding compared to U.S.-born mothers. In contrast, foreign-born non-English-speaking Asian/Pacific Islander mothers were less likely to breastfeed than their U.S.-born counterparts (AOR=0.80; 95% CI=0.73, 0.87).

Discussion

Although foreign-born mothers had more disadvantaged socioeconomic profiles than U.S.-born mothers, as measured by educational attainment and insurance status, they engaged in more positive health behaviors. The proportion of mothers who smoked during pregnancy and started breastfeeding varied widely across 31 ethnic groups, which would be impossible to see using standard OMB race/ethnicity categories. Although maternal health behaviors also varied by mothers’ country of birth and language preference, the associations of mothers’ acculturation with health behaviors were largely consistent for mothers from nearly all ethnic groups. Foreign-born mothers were less likely to smoke during pregnancy and more likely to initiate breastfeeding than their U.S.-born counterparts, except for some mothers with Asian ethnicities. By combining mothers’ country of birth and language preference, there was also evidence of an additional acculturation gradient within foreign-born mothers—those who were non-English speakers had more positive health behaviors than those who were English speakers.

These results are consistent with other studies that found inverse associations between acculturation and maternal health behaviors, as more acculturated mothers were more likely to smoke during pregnancy13–15 or not start breastfeeding.7–12 Most studies have either focused on broad ethnic groups, such as Hispanic mothers,10–13,16,18 or compared foreign-born and U.S.-born mothers by broad race/ethnicity categories.7–9,15 Consequently, little is known about acculturation among rapidly growing immigrant populations, such as Asian mothers, or the extent of the heterogeneity of maternal health behaviors across more specific ethnic groups. For example, the number of mothers from Portuguese-speaking communities in Massachusetts has increased over the last 15 years.20,21 In this study, U.S.-born mothers from these populations had some of the highest rates of maternal smoking during pregnancy and lowest rates of breast-feeding initiation, which would not have been identified using standard OMB race/ethnicity categories.

Despite a greater proportion of foreign-born mothers having lower educational attainment and their delivery paid for by public sources, these mothers had the most positive health behaviors. Other studies have demonstrated similar findings.8,10,11,13 Although potential mechanisms could not be explored using the birth certificate data, selective migration suggests that immigrants may be the individuals from their communities that are healthier and engage in healthful behaviors.17,27 Rates of smoking and breastfeeding among women are often much lower and higher, respectively, than rates in the U.S.28,29 Although the birth certificate does not collect information on when foreign-born mothers immigrated to the U.S., language preference may be a proxy for time spent in the U.S. Recent immigrants may be more likely to prefer their native language, whereas mothers who arrived at a young age may prefer English as their primary language. Foreign-born mothers who have been in the U.S. longer have had greater exposure to the health-related norms and behaviors of the dominant culture in the U.S. Foreign-born mothers who report English as their language preference were found to engage in health behaviors at rates that were in between U.S.-born mothers and foreign-born non-English-speaking mothers.

In contrast to other ethnic groups, this study found that some foreign-born mothers with Asian ethnicities were less likely to initiate breastfeeding than their U.S.-born counterparts. Among Korean, Filipino, and Japanese mothers, foreign-born mothers were more likely to initiate breastfeeding than their U.S.-born counterparts. As illustrated in Table 4, foreign-born non-English-speaking Chinese and Vietnamese mothers were less likely to initiate breastfeeding than their U.S.-born counterparts. The UN Children’s Fund recently highlighted the low breastfeeding rates in many East Asian countries,30 which may be reflected in rates among immigrants from these countries. Further research is needed to investigate this finding. Similarly, most studies have either included all Hispanic mothers together7–11,15 or focused on Mexican mothers,12,13 but in these data from Massachusetts, Puerto Rican mothers were more likely to smoke during pregnancy and less likely to start breastfeeding than mothers from other ethnic groups often combined into a broad Hispanic category. These findings provide further support for the notion that detailed ethnicity may better reflect cultural practices.31

There are some limitations to the birth certificate data. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is based on self-report, which has been shown to be under-reported on the birth certificate compared to information collected from a confidential survey a few months postpartum.6 There is some evidence that under-reporting is higher among more advantaged mothers, but there are no differences by maternal race/ethnicity.6,32 Breastfeeding on the birth certificate is recorded by the birth facility and should be considered an indicator for breastfeeding initiation. However, a study in Massachusetts found a high level of agreement in breastfeeding initiation between data collected on the birth certificate with hospital infant feeding records and no racial/ethnic or socioeconomic differences.33 We have no reason to believe there would be a reporting bias by nativity. Although some mothers were included in the data set more than once because of multiple pregnancies during this time period, identifying information to explore repeat births was not available. Analyses were repeated for mothers who gave birth for the first time or had single births, and the pattern of results was similar (data not shown). Although the authors recognize the importance of accurately measuring acculturation, proxy measures are often used because of challenges in measurement at the population level. Lara and colleagues16 have suggested that the benefits of collecting some information on acculturation for public health purposes outweigh the limitation that these measures may be imperfect. Although these results may be applicable only to mothers in Massachusetts, the sociodemographic characteristics of new mothers in the U.S. as a whole are similar, particularly for births by foreign-born mothers.19 In 2009, 30% of new mothers in Massachusetts21 and 24% of new mothers in the U.S.19 were born outside the 50 states and District of Columbia.

Conclusions

There were consistent associations between being foreign-born and less smoking across nearly 31 ethnic groups and more breastfeeding initiation among most ethnic groups, except for some mothers with Asian ethnicities. These findings suggest that for the majority of the studied ethnic groups, acculturation in the U.S. results in poorer maternal health behaviors. Public health measures need to both support the preservation of these positive health-related norms and behaviors from mothers’ original cultures and simultaneously improve the norms in the U.S. related to smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Prevention efforts will likely require an interdisciplinary approach through clinical, policy, and population-based efforts aimed at maintaining and promoting positive maternal health behaviors during pregnancy and postpartum.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R00HD068506) to Dr. Hawkins. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Appendix

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.02.015.

References

- 1.USDHHS. The Surgeon General’s call to action to support breastfeeding. Washington DC: USDHHS, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USDHHS. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta GA: USDHHS, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state—National Immunization Survey, U.S., 2004–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(11):32734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong VT, Jones JR, Dietz PM, D’Angelo D, Bombard JM. CDC. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), U.S., 31 sites, 2000–2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(4):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belanoff CM, McManus BM, Carle AC, McCormick MC, Subramanian SV. Racial/ethnic variation in breastfeeding across the U.S.: a multilevel analysis from the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2007. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(1S):S14–S26. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0991-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen AM, Dietz PM, Tong VT, England L, Prince CB. Prenatal smoking prevalence ascertained from two population-based data sources: birth certificates and PRAMS questionnaires, 2004. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(5):586–592. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merewood A, Brooks D, Bauchner H, MacAuley L, Mehta SD. Maternal birthplace and breastfeeding initiation among term and preterm infants: a statewide assessment for Massachusetts. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1048–e1054. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celi AC, Rich-Edwards JW, Richardson MK, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW. Immigration, race/ethnicity, and social and economic factors as predictors of breastfeeding initiation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(3):255–260. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh GK, Kogan MD, Dee DL. Nativity/immigrant status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic determinants of breastfeeding initiation and duration in the U.S., 2003. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1S):S38–S46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson MV, Diaz VA, Mainous AG, 3rd, Geesey ME. Prevalence of breastfeeding and acculturation in Hispanics: results from NHANES 1999–2000 study. Birth. 2005;32(2):93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahluwalia IB, D’Angelo D, Morrow B, McDonald JA. Association between acculturation and breastfeeding among Hispanic women: data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(2):167–173. doi: 10.1177/0890334412438403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson-Davis CM, Brooks-Gunn J. Couples’ immigration status and ethnicity as determinants of breastfeeding. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):641–646. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madan A, Palaniappan L, Urizar G, Wang Y, Fortmann SP, Gould JB. Sociocultural factors that affect pregnancy outcomes in two dissimilar immigrant groups in the U.S. J Pediatr. 2006;148(3):341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elo IT, Culhane JF. Variations in health and health behaviors by nativity among pregnant black women in Philadelphia. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2185–2192. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perreira KM, Cortes KE. Race/ethnicity and nativity differences in alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1629–1636. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the U.S.: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acevedo-Garcia D, Bates LM, Osypuk TL, McArdle N. The effect of immigrant generation and duration on self-rated health among U.S. adults 2003–2007. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(6):1161–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: final data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol. 60 no. 1. Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Advance data: Massachusetts births 1998. Boston MA: Division of Research and Epidemiology, Bureau of Health Information, Statistics, Research, and Evaluation. MDPH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Massachusetts births 2009. Boston MA: Division of Research and Epidemiology, Bureau of Health Information, Statistics, Research, and Evaluation, MDPH; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Census Bureau. Selected social characteristics in the U.S., 2006–2010 American Community Survey 5-year estimates: Massachusetts. factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_10_5YR_DP02.

- 23.Friedman DJ, Cohen BB, Averbach AR, Norton JM. Race/ethnicity and OMB Directive 15: implications for state public health practice. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1714–1719. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leavitt G, Martinez S, Ortiz N, García L. Knowledge about breastfeeding among a group of primary care physicians and residents in Puerto Rico. J Community Health. 2009;34(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.USDHHS. Public Health Service. Women and smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Washington DC: Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grummer-Strawn LM, Shealy KR. Progress in protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding: 1984–2009. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4(1S):S31–S39. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543–1548. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO. Tobacco control country profiles. who.int/tobacco/surveillance/policy/country_profile/en/index.html.

- 29.WHO. Infant and young child feeding data by country. who.int/nutrition/databases/infantfeeding/countries/en/index.html.

- 30.UNICEF. UNICEF rings alarm bells as breastfeeding rates plummet in East Asia. unicef.org/media/media_62337.html.

- 31.Lin SS, Kelsey JL. Use of race and ethnicity in epidemiologic research: concepts, methodological issues, and suggestions for research. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22(2):187–202. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Land TG, Landau AS, Manning SE, et al. Who underreports smoking on birth records: a Monte Carlo predictive model with validation. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navidi T, Chaudhuri J, Merewood A. Accuracy of breastfeeding data on the Massachusetts birth certificate. J Hum Lact. 2009;25(2):151–156. doi: 10.1177/0890334408330615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.