Abstract

High mammographic breast density is one of the strongest intermediate markers of breast cancer risk, and decreases in density over time have been associated with decreases in breast cancer risk. Using repeated measures of mammographic density in a cohort of high-risk women, the Women at Risk (WAR) cohort at Columbia University Medical Center (N = 2670), we examined whether changes in prediagnostic mammographic density differed among 85 prospectively-ascertained breast cancer cases and 85 age-matched controls, using a nested case–control design. Median age at first mammogram was 51 years (range, 29–77 years), with a median of 4 years between first and second prediagnostic mammogram (range, 1–15 years). Using linear regression with change in percent density as the outcome, we found that in women who did not go on to be diagnosed with breast cancer, change in percent density decreased as time between first and second mammogram increased (β = −1.62% per year, p = 0.004). However, in women who did go on to be diagnosed with breast cancer, there was no overall change in percent density associated with time between first and second mammogram (β = 0.29% per year, p = 0.61); the change over time was statistically significantly different between cases versus controls (p <0.009). If replicated in larger cohorts, these results suggest that within-individual changes in mammographic density as measured by percent density may be a useful biomarker of breast cancer risk.

Keywords: mammographic density, breast cancer, high-risk cohort, cancer biomarker

Mammographic breast density is a strong and potentially modifiable risk factor for breast cancer.1–6 Even though there is a strong and well-documented association between single measures of breast density and breast cancer risk, and it is well established that breast density declines with increasing age, particularly around menopause,1,6–9 and with tamoxifen use,10 few studies have examined whether declines in density over time are related to reduced breast cancer risk.11–13 One notable study was a large cohort study of women with breast density measures based upon the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data Systems (BI-RADS) classification, which found that decreases in density are associated with reduced breast cancer risk.11 However, only a minority of women changed a full BI-RADS category in this study,11 limiting the ability to draw conclusions about whether more modest changes in breast density may still be clinically useful to identify women at higher risk of breast cancer. A recent study that examined smaller changes in density did not find an association with decreases in breast density over time and reduced rates of breast cancer in an average risk, primarily postmenopausal population.13

To evaluate whether smaller changes over time using continuous measures of density were associated with reductions in breast cancer risk in a population at higher risk of breast cancer, we conducted a nested case–control study within the Women at Risk (WAR) Registry at Columbia University Medical Center.

There is little information on changes in breast density in populations at higher risk for breast cancer,14–18 although the few that exist have found higher breast density in those with family history of breast cancer,16,17 and in women of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.18

Material and Methods

The details of the WAR registry have been published elsewhere (for details, see Refs.19–20). Briefly, from 1991 to July 2011, the WAR registry enrolled participants in the breast clinic at Columbia University Medical Center, who met at least one of the following criteria: one or more first-degree relative with premenopausal breast cancer; two or more first-degree relatives with postmenopausal breast cancer; known BRCA1 or BRCA2 deleterious mutation carrier; a biopsy-proven history of lobular carcinoma in situ; a biopsy-proven history of atypical ductal hyperplasia or atypical lobular hyperplasia. We extracted all patient data from medical chart reviews and a detailed epidemiological questionnaire completed at baseline enrollment, and all incident breast cancer cases were confirmed with the New York-Presbyterian Hospital Tumor Registry.

What's New?

Higher breast density means a higher risk of cancer. This is well known, but only for single measure of breast density. As a woman ages, her breasts become less dense, and how might these changes over time affect cancer risk? These authors tackled that question by analyzing mammographic data on women at high risk of breast cancer. They found that breast density decreased in women who did not develop cancer, but not in those who did, suggesting that monitoring changes in breast density could help identify women at greater risk of disease.

Of the 2670 women in the WAR cohort, 104 women were prospectively diagnosed with breast cancer by May, 2010 (an average of 5 years after enrollment, range 1–15 years). Of these 104 women, 85 had information from at least one prediagnostic film mammogram and 67 had information on at least two prediagnostic film mammograms (we used only film mammograms for the analysis, repeated measures were all film). We individually matched these 85 cases on year of birth with cohort members free from cancer at the time of the case's diagnosis (the controls) in a 1:1 ratio. In addition to individual matching on year of birth and time in study, we also frequency-matched cases and controls on age at the first pre-diagnostic mammogram, and time (in years) between first and second mammograms. We used incidence density sampling so controls were selected from the remaining cohort of women still being followed by the high risk registry. Two readers independently assessed densities for the left breast blinded to cases–control status, first or second mammogram, and blinded to any prior medical history including history of benign breast disease (BBD) or exposure information, using a semiautomated computer-assisted technique with Cumulus software,21 and their scores were averaged. We read breast density in batches, with the repeated mammograms for an individual randomized within the same batch and random quality repeats per batch to determine reliability. We reread any mammograms when the findings between readers differed by more than 15%. The within-batch reliability was 95%, and the between-batch reliability was 86%. We defined changes in percent density as the difference between percent density at first mammogram and percent density at second mammogram, for participants with two mammograms.

Because breast density measures are known to decline around the menopause, we examined whether our pairs were concordant on menopausal status at both their first and second mammograms (i.e., both member of pair premenopausal for both mammograms, postmenopausal for both mammograms, or changed their menopausal status between first and second mammograms). We found that for 75 of 85 pairs (88%) the pairs were concordant on menopausal status. For 10 of 85 pairs (12%) the pairs were discordant. We ran sensitivity analyses excluding these 10 pairs and also additionally adjusted for menopausal status in the analysis to account for the discordance of these 10 pairs on menopausal status.

We examined established breast cancer risk factors as potential confounders in our analyses (including age at first mammogram, parity, family history, body mass index (BMI), oral contraceptive use, alcohol use and menopausal status). We examined frequency statistics and univariable logistic regression to determine which risk factors were associated with case and control status and associated with breast density, to identify potential confounders. Because women were individually matched by year of birth, we did not additionally adjust for age. We then conducted a multivariable conditional logistic regression to examine the relation between breast density, change in breast density, and case/control status, adjusted for age at first mammogram (Model 1) as well as for other identified confounders (Model 2) and additionally adjusted for baseline density, (Model 3). We conducted tests of linear trend for these analyses.

Additionally, we conducted multivariable linear regression using continuous change in percent density as the dependent variable, and time between first and second mammogram (continuous) as the independent variable, adjusted for age at first mammogram and other identified confounders. We used SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC) for all analyses.

Results

Table 1 describes the demographic and initial density information for cases and controls. The median age at breast cancer diagnosis was 54.5 years, and cancer diagnosis occurred a median of 1.5 years after the second mammogram (range, 6 months to 9.4 years). Cases and controls did not differ significantly on baseline factors, including median age at first mammogram used for our study (cases: 52.7-years-old, controls 51.5-years-old), median time between first and second mammogram (cases 4.7 years, controls 4.6 years), or baseline percent density (cases' baseline percent density 29.0%, controls 29.2%). Percent density decreased from Time 1 to Time 2 in both cases and controls, consistent with increasing age over time in the cohort (mean percent density at time 2: cases 25.5%, controls 23.7%). The study population was predominantly White (90%), had an average body mass index (BMI) of 25, and about 50% of both cases and controls were postmenopausal at the time of first mammogram used for analysis. Greater than 60% of both cases and controls had a personal history of BBD, and greater than 60% had a family history of breast cancer.

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic and density characteristics among cases and age-matched controls with mammographic data in the Women At Risk registry, Columbia University Medical Center

| Cases, N = 85, N (%) | Controls, N = 85, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis1 | 54.5 years (range 37–84) | 54.0 years (range 36–85) |

| Median age at first mammogram2 | 52.7 years (range 32–77) | 51.5 years (range 29–76) |

| Median time between mammograms (years) | 4.0 (range 1–15) | 4.0 (range 1–14) |

| Median time between 2nd mammogram and cancer Dx (years) | 1.5 (range 0.5–9.4) | NA |

| Density characteristics | ||

| Mean percent density, time 1 (%) | 29.0 (range 3–96) | 29.2 (range 1–84) |

| Mean percent density, time 2 (%) | 25.5 (range 5–59) | 23.7 (range 2–77) |

| Mean change in % density | −2.67 (range −34–16) | −5.35 (range −48–49) |

| Demographic and risk factor characteristics | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 70 (88) | 71 (91) |

| African American | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Hispanic | 4 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Other | 4 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Family history of breast cancer | ||

| Yes | 52 (63) | 60 (75) |

| No | 30 (37) | 20 (25) |

| History of benign breast disease | ||

| Yes | 53 (66) | 63 (75) |

| No | 27 (34) | 21 (25) |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Yes | 39 (62) | 38 (59) |

| No | 24 (38) | 26 (41) |

| BMI | ||

| Average | 24.8±5.2 | 24.8±4.0 |

| Oral contraceptive use | ||

| Never | 43 (61) | 45 (62) |

| Ever | 28 (39) | 27 (38) |

| Menopausal status3 | ||

| Premenopausal | 44 (53) | 42 (50) |

| Postmenopausal | 39 (47) | 42 (50) |

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 23 (27) | 18 (22) |

| 1 or 2 live births | 47 (55) | 47 (56) |

| ≥3 live births | 15 (18) | 18 (22) |

| Among parous women only: | ||

| Age at first birth (mean) | ||

| Average | 27.2 | 27.5 |

| Time since last birth4 | ||

| Average (years) | 27.4 | 30.0 |

| Breastfeeding | ||

| Never | 27 (47) | 34 (51) |

| Ever | 31 (53) | 32 (49) |

The age at diagnosis for the controls refers to the age of the controls when their matched case was diagnosed with cancer.

Age at first mammo is age at the first mammogram used for density readings in this analysis, NOT the age of the woman at her first ever mammogram.

Indicates menopausal status at first mammogram used for density readings.

For cases, time since last birth is time between last birth and cancer diagnosis. For controls, time since last birth is time between last birth and the cancer diagnosis of their matched case.

Table 2 describes the findings of the logistic regression for percent density and change in percent density, using a conditional logistic regression to create three models: a model adjusted for age at first mammogram, a model additionally adjusted for age at first mammogram, parity, family history and menopausal status, and a model adjusted for those factors and additionally adjusted for baseline density reading. A >5% decrease in percent density was inversely associated with breast cancer (OR = 0.56, 95%CI 0.15–2.17), while a >5% increase in percent density was positively associated with breast cancer (OR = 2.55, 95%CI 0.63–10.26); however, these associations were not statistically significant, and a test for trend did not demonstrate significance.

Table 2.

Association between mammographic breast density and change in breast density and breast cancer risk, Women At Risk registry, Columbia University Medical Center

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Cases (N = 85) | Controls (N = 85) | Age-Adjusted Model1 OR (95% CI) | Additionally Adjusted for Parity, Family History, Menopausal Status OR (95% CI) | Adjusted for Parity, Family History, Menopausal Status, and Baseline Density2OR (95% CI) |

| Percent density, Time 1 (categorical)3 | |||||

| Less than 16% | 25 | 31 | Reference | Reference | |

| ≥16%, less than 34% | 33 | 26 | 1.66 (0.71–3.87) | 1.59 (0.58–4.33) | |

| 34% or greater | 27 | 28 | 1.93 (0.79–4.70) | 2.57 (0.81–8.10) | |

| pTrend = 0.15 | pTrend = 0.11 | ||||

| Percent density, time 2 (categorical) | |||||

| Less than 16% | 28 | 26 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 16%, less than 34% | 24 | 23 | 1.41 (0.56–3.55) | 1.40 (0.47–4.19) | 1.36 (0.43–4.28) |

| 34% or greater | 15 | 18 | 2.34 (0.69–7.92) | 1.55 (0.38–6.55) | 1.43 (0.33–6.22) |

| pTrend = 0.17 | pTrend = 0.54 | pTrend = 0.63 | |||

| Change in percent density (categorical) | |||||

| Greater than 5% decrease | 28 | 32 | 0.96 (0.41–2.25) | 0.78 (0.26–2.36) | 0.56 (0.15–2.17) |

| −5% to 5% change | 22 | 25 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Greater than 5% increase | 17 | 10 | 1.89 (0.71–5.06) | 2.42 (0.62–9.42) | 2.55 (0.63–10.26) |

| pTrend = 0.19 | pTrend = 0.10 | pTrend = 0.07 | |||

All models estimated using conditional logistic regression models, adjusted for age at first mammogram

Baseline density measures include dense area in cm2 at time 1, and percent density time 1.

Percent density at time 1 and time 2 cut-points were defined by tertiles of percent density for controls at first mammogram, rounded to nearest whole %.

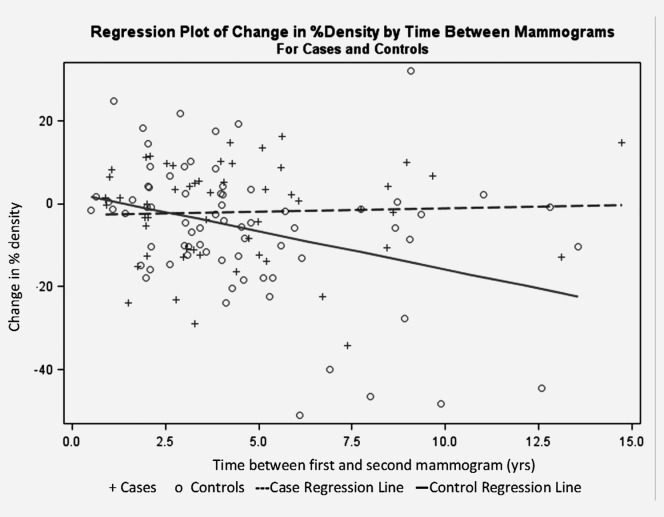

Figure 1 illustrates the association between time between first and second mammograms and change in percent density, adjusted for age at first mammogram, parity, family history and baseline density. For the controls, as time between first and second mammograms increased, breast density decreased significantly (β = −1.62% per year in percent density p = 0.004). For the cases, as time between first and second mammograms increased, breast density did not decrease (β = 0.29% per year in percent density, p = 0.63); in an ANCOVA comparing the slopes of the regression lines, the slopes were significantly different for cases as compared with controls (p = 0.009).

Figure 1.

Regression plot of change in % density by time between mammograms for cases and controls, Women At Risk registry.

Discussion

We found that, as calendar time between mammograms increased, mammographic density decreased, on average, for women that did not go on to be diagnosed with breast cancer (controls), but not for high-risk women who developed breast cancer. Few studies have prospectively examined changes in continuous measures of density.11–13,22 Although larger decreases (20–25%) in percent density reduced breast cancer risk in several studies11,22; another study found no association between change in percent density with breast cancer risk when examining changes in percent density by quartiles12; the range of percent density changes was relatively small in the study (−10% to +6.5%). In a more recent study, where changes in density were examined prospectively, a decrease in density was not associated with a change in breast cancer risk.13 We prospectively assessed breast cancer risk in relation to density on mammograms that occurred between 6 months and 9.5 years before diagnosis, in a population at higher risk of breast cancer, and found that there was, overall, an association with change in breast density in cases versus controls.

Although we observed an approximate two-fold association between higher breast density and breast cancer risk, our cohort is limited by the overall sample size, which decreased the statistical power to evaluate this association. We were also limited by incomplete data on exogenous hormone use from the medical record. Tamoxifen, a chemopreventive agent, has been shown to decrease breast density,10,23 and a previous study indicated that a 10% or greater decrease in density was associated with a 63% reduction in breast cancer risk.23 However, the use of tamoxifen as a preventive agent was likely more limited given that the cohort was established in the mid-1990s. If controls, however, were more likely to use tamoxifen as compared to the cases this might explain the decrease in breast density over time relative to the cases. Given that all women were part of a high risk registry, at a single institution follow-up care and prevention recommendations were likely more homogenous.

If replicated in larger studies, our findings suggest that high-risk women who go on to develop breast cancer may have slower declines in breast density over time as compared to women who are not diagnosed with breast cancer. Tracking of changes in mammographic density within individuals may be clinically possible, as automated calculations of mammographic density now exist for digital mammography.24 However, it is important to note that the declines observed in the women who did not go on to be diagnosed with cancer were modest, and therefore larger studies that replicate our findings are needed before clinical guidelines on breast density changes are used for risk monitoring. The promise, however, could mean that following women over time to observe within-individual changes in density may help target women at higher future risk, and allow them to engage in preventive measures, including chemoprevention, if they do not experience decreases in breast density over time.

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Boyd NF, Byng JW, Jong RA, et al. Quantitative classification of mammographic densities and breast cancer risk: results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:670–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.9.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd NF, Lockwood GA, Byng JW, et al. Mammographic densities and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1133–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne C, Schairer C, Wolfe J, et al. Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: effects with time, age, and menopause status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1622–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.21.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciatto S, Zappa M. A prospective study of the value of mammographic patterns as indicators of breast cancer risk in a screening experience. Eur J Radiol. 1993;17:122–5. doi: 10.1016/0720-048x(93)90048-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato I, Beinart C, Bleich A, et al. A nested case-control study of mammographic patterns, breast volume, and breast cancer (New York City, NY, United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:431–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00052183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oza AM, Boyd NF. Mammographic parenchymal patterns: a marker of breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:196–208. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartow SA, Pathak DR, Mettler FA, et al. Breast mammographic pattern: a concatenation of confounding and breast cancer risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:813–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maskarinec G, Pagano I, Lurie G, et al. A longitudinal investigation of mammographic density: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:732–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd N, Martin L, Stone J, et al. A longitudinal study of the effects of menopause on mammographic features. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1048–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney E, et al. Tamoxifen and breast density in women at increased risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:621–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerlikowske K, Ichikawa L, Miglioretti DL, et al. Longitudinal measurement of clinical mammographic breast density to improve estimation of breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:386–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vachon CM, Pankratz VS, Scott CG, et al. Longitudinal trends in mammographic percent density and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:921–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lokate M, Stellato RK, Veldhuis WB, et al. Age-related changes in mammographic density and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:101–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin LJ, Melnichouk O, Guo H, et al. Family history, mammographic density, and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:456–63. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warwick J, Pinney E, Warren RM, et al. Breast density and breast cancer risk factors in a high-risk population. Breast. 2003;12:10–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9776(02)00212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziv E, Shepherd J, Smith-Bindman R, et al. Mammographic breast density and family history of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:556–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.7.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crest AB, Aiello EJ, Anderson ML, et al. Varying levels of family history of breast cancer in relation to mammographic breast density (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:843–50. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caswell JL, Kerlikowske K, Shepherd JA, et al. High mammographic density in women of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R40. doi: 10.1186/bcr3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chun J, Joseph KA, El-Tamer M, et al. Cohort study of women at risk for breast cancer and gross cystic disease. Am J Surg. 2005;190:583–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chun J, El-Tamer M, Joseph KA, et al. Predictors of breast cancer development in a high-risk population. Am J Surg. 2006;192:474–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heine JJ, Carston MJ, Scott CG, et al. An automated approach for estimation of breast density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3090–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Gils CH, Hendriks JH, Holland R, et al. Changes in mammographic breast density and concomitant changes in breast cancer risk. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999;8:509–15. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199912000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney E, et al. Tamoxifen-induced reduction in mammographic density and breast cancer risk reduction: a nested case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:744–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vachon CM, Fowler EE, Tiffenberg G, et al. Comparison of percent density from raw and processed full-field digital mammography data. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R1. doi: 10.1186/bcr3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]