Abstract

ADAMTS9 is the most conserved member of a large family of secreted metalloproteases having diverse functions. Adamts9 null mice die before gastrulation, precluding investigations of its roles later in embryogenesis, in adult mice or disease models. We therefore generated a floxed Adamts9 allele to bypass embryonic lethality. In this mutant, unidirectional loxP sites flank exons 5 through 8, which encode the catalytic domain, including the protease active site. Mice homozygous for the floxed allele were viable, lacked an overt phenotype, and were fertile. Conversely, mice homozygous for a germ-line deletion produced from the floxed allele by Cre-lox recombination did not survive past gastrulation. Hemizygosity of the deleted Adamts9 in combination with mutant Adamts20 led to cleft palate and severe white spotting as previously described. Previously, Adamts9 haploinsufficiency combined with either Adamts20 or Adamts5 nullizygosity suggested a cooperative role in interdigital web regression, but the outcome of deletion of Adamts9 alone remained unknown. Here, Adamts9 was conditionally deleted in limb mesoderm using Prx1-Cre mice. Unlike other ADAMTS single knockouts, limb-specific Adamts9 deletion resulted in soft-tissue syndactyly (STS) with 100% penetrance and concurrent deletion of Adamts5 increased the severity of STS. Thus, Adamts9 has both non-redundant and cooperative roles in ensuring interdigital web regression. This new allele will be useful for investigating other biological functions of ADAMTS9.

Keywords: A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease domain with thrombospondin type 1 motifs 9, soft tissue syndactyly, interdigital web, apoptosis, Prx1-Cre, floxed, cleft palate, melanoblast

INTRODUCTION

Secreted metalloproteases have crucial roles in proteolytic processing of cell-surface, extracellular matrix (ECM) and other secreted molecules. The 19 ADAMTS (A disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase domain with thrombospondin type 1 motif) family members constitute a major class of such proteases, and share a modular structure containing one or more thrombospondin type 1 repeats (TSRs) (Apte, 2009). ADAMTS proteases are synthesized as zymogens having an N-terminal propeptide, which regulates folding and activity of the adjacent catalytic domain. An ancillary domain downstream of the catalytic domain contains the TSRs and is typically required for substrate binding. Phylogenetic analysis has identified ADAMTS gene expansion during vertebrate evolution, implying that vertebrate ADAMTS proteinases have conserved, duplicated, or newly acquired functions (Huxley-Jones et al., 2005). Indeed, inherited human or animal mutations and targeted mouse mutations have identified diverse functions for ADAMTS proteases in a variety of contexts (Apte, 2009).

ADAMTS9 is the largest ADAMTS as well as the most highly conserved family member, based on its high homology to nematode and fruit fly proteases, named Gon-1 and Adamts-A respectively (Blelloch et al., 1999; Clark et al., 2000; Ismat et al., 2013; Somerville et al., 2003). Previous work identified two extracellular matrix proteoglycans, versican and aggrecan, as ADAMTS9 substrates (Somerville et al., 2003). Versican is widely distributed during mouse embryogenesis, whereas aggrecan is a specialized product of cartilage. Neither proteoglycan is encoded by the nematode or fruit fly genomes (Ismat et al., 2013). To determine ADAMTS9 functions during vertebrate embryogenesis, we previously characterized an Adamts9 null allele (Adamts9LacZ) in which intragenic IRES-lacZ was used to disrupt the gene (Kern et al., 2010). Mice hemizygous for this allele developed externally evident ocular defects and subtle cardiac developmental anomalies (Kern et al., 2010; Koo et al., 2010). Adamts9LacZ/LacZ null mice, however, did not survive past 7.5 days of gestation (Kern et al., 2010), for reasons that are not yet fully understood, which has precluded comprehensive analysis of its biological and disease impact. When bred for many generations into the C57Bl/6 strain, Adamts9LacZ/+ mice showed a variable penetrance of cardiac developmental anomalies (Kern et al., 2010) and 80% penetrance of ocular anterior segment dysgenesis (Koo et al., 2010).

The proteoglycan-cleaving activity of ADAMTS9 is shared with other family members, among them ADAMTS20 and ADAMTS5. ADAMTS20 is highly homologous to ADAMTS9 and is evolutionarily related to Gon-1 (Llamazares et al., 2003; Somerville et al., 2003), whereas ADAMTS5 is a much smaller protease and is representative of a different ADAMTS evolutionary clade. A spontaneous Adamts20 mutant named belted (bt) demonstrated white spotting of the torso, but otherwise appeared to be normal (Llamazares et al., 2003; Rao et al., 2003). To investigate the functional relationship of ADAMTS9 with ADAMTS20, combinatorial mutants of Adamts9 and Adamts20 (bt) were generated. Because of lethality of Adamts9 null embryos, double null embryos could not be obtained. Adamts20bt/bt; Adamts9LacZ/+ embryos survived past gastrulation, but died at birth with a fully penetrant, completely cleft secondary palate resulting from delayed migration of palatal shelves to the midline (Enomoto, 2010). These mice had a massive reduction of pigmented hair follicles compared to Adamts20bt/bt mice (Silver, 2008). They developed soft-tissue syndactyly (STS), a phenotype also present in Adamts20bt/bt; Adamts5LacZ/LacZ mice and Adamts9LacZ/+; Adamts5LacZ/LacZ mice (McCulloch et al., 2009). In each of these phenotypes, reduced versican processing was associated with the observed developmental defect, suggesting that ADAMTS proteases were crucial for versican processing in these contexts. Furthermore, crosses of Adamts20bt/bt with Vcanhdf/+ (hdf, heart defect, a Vcan null allele resulting from insertional mutagenesis), i.e., Adamts20bt/bt;Vcanhdf/+ mutants, developed cleft palate and STS with high penetrance, suggesting a requirement for processed versican as a molecular mechanism underlying STS and cleft palate (Enomoto, 2010; McCulloch et al., 2009). Indeed a proteolytically derived versican fragment (including the versican G1 domain and extending from the N-terminus to Glu441, i.e., G1-DPEAAE441) named versikine (Nandadasa et al., 2014) could induce apoptosis in Adamts20bt/bt; Adamts5LacZ/LacZ interdigital webs.

Taken together, these findings from single and combined Adamts9 mutants suggested crucial developmental contributions by ADAMTS9 toward normal gastrulation, craniofacial, cardiovascular and limb development, and melanoblast colonization of skin. Detailed developmental expression analysis identified Adamts9 as a major product of mesenchymal cells in developing epithelial organs (such as lung and kidney), as well as some epithelia, vascular smooth muscle cells and microvascular endothelium (Enomoto, 2010; Jungers et al., 2005; Koo et al., 2010; McCulloch et al., 2009). ADAMTS9 is a tumor suppressor gene in esophageal squamous cell and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and was shown to be anti-angiogenic (Koo et al., 2010; Lo et al., 2010; Lung et al., 2008). Abnormal ADAMTS9 methylation was found in gastric cancer and it was identified as a tumor suppressor in this cancer (Du et al., 2012; Koo et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). Furthermore, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have associated genomic variants near the ADAMTS9 locus with type II diabetes, obesity and age-related macular degeneration, as well as other disorders (Heid et al., 2010; Helisalmi et al., 2014; Zeggini et al., 2008). The widespread expression of Adamts9 and the multiple developmental and disease contexts in which ADAMTS9 has been implicated, coupled with embryonic lethality of the null allele, underscored the need for a floxed allele for conditional inactivation of Adamts9. We describe here the generation, genetic validation, and utility of such an allele. We have used it to define both non-redundant and redundant roles for Adamts9 in interdigital web regression during mouse development.

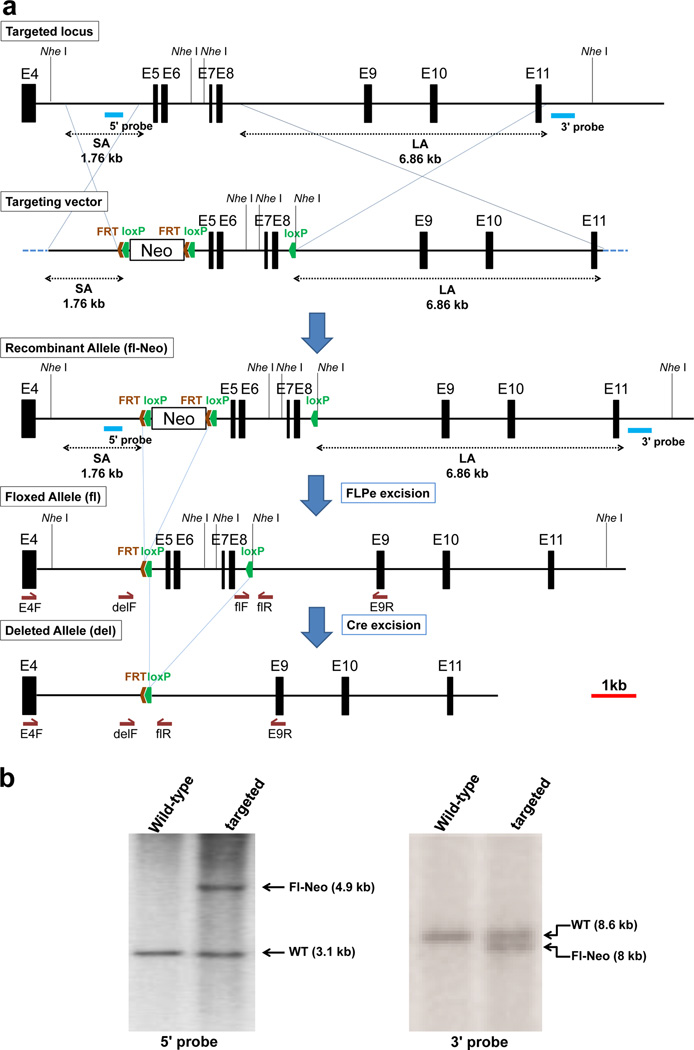

A targeting vector was constructed from C57BL/6 genomic DNA by inserting unidirectional loxP sites in intron 4 and intron 8 and a FRT flanked neomycin resistance selection cassette in intron 4 (Fig. 1a). The exons 5–8, which are targeted for Cre-lox recombination, encode a substantial part of the catalytic domain of ADAMTS9, including the catalytic active site, which is required for proteolysis. The transcript resulting from exon 4-exon 9 splicing after deletion of exons 5–8 would have a frame-shift, and could be subject to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. This transcript cannot generate a functional protein, since, following targeting, the Adamts9 mRNA, if stable, would generate only the N-terminal propeptide, to which no innate activity has been ascribed in any ADAMTS protease. Following electroporation in ITL C57BL/6 ES cells, potential recombination with the construct was sought using G418 selection. One ES cell clone was identified as correctly targeted by homologous recombination from 96 clones screened using Southern blotting with 5´ and 3´ genomic probes (Fig. 1b). Targeted ES cells were injected into BALB/c blastocysts to generate chimeras. Male chimeras were crossed to C57BL/6 females to obtain F1 progeny carrying one floxed ADAMTS9 allele (designated Adamts9fl-Neo/+), which were identified using PCR of genomic DNA (gDNA).

Figure 1. Targeting strategy and confirmation of homologous recombination in ES cells.

a. Schematic of the Adamts9 locus, targeting vector, recombinant allele and subsequent modification by FlpE excision of Neo and Cre excision of the floxed region. Exons are shown as solid bars and numbered consecutively (E4–E11). The vector arms are indicated as SA (short arm) and LA (long arm). The 5' and 3' probes used for screening of ES cell colonies are identified by blue lines. Restriction endonuclease Nhe I recognition sites are shown. FRT and Lox P sites are indicated in red and green respectively. The schematic is drawn to scale, with the scale bar indicated at bottom right (red line). b. Southern analysis of NheI digested genomic DNA from ES cells with or without (wild-type) successful homologous recombination of the targeting vector. The expected wild-type (WT) band and that resulting from homologous recombination (Fl-Neo) are indicated.

The presence of Neo in targeting constructs is known to interfere with gene expression (Lewandoski, 2007). Consistent with this, viable Adamts9fl-Neo/ fl-Neo mice were not obtained from intercrosses of Adamts9fl-Neo/+ mice. Therefore, Adamts9fl-Neo/+ mice were crossed with C57BL/6 mice having an ACTB-FLPe transgene (Rodriguez et al., 2000) for Neo excision by recombination of the FRT sites (Fig. 1a). Neo excision was confirmed in the progeny of this cross by PCR of gDNA, and these mice were subsequently crossed to wild-type C57BL/6 mice for germline transmission of the Neo-deleted floxed allele (designated Adamts9fl/+) and elimination of the ACTB-FLPe transgene. Intercrosses of Adamts9fl/+ mice provided Adamts9fl/fl mice in the expected Mendelian ratio. These mice were viable, fertile and externally normal when followed for up to 1 year of age, suggesting that the inserted loxP sites did not interfere with Adamts9 function. In particular, Adamts9fl/fl mice lacked the highly penetrant, externally evident ocular phenotype reported in Adamts9lacZ/+ mice (Koo et al., 2010). Taken together, these findings suggested unimpaired ADAMTS9 function after genetic engineering to produce Adamts9fl.

To validate Adamts9fl/+ for its utility in gene targeting, we crossed Adamts9fl/+ mice with Prm1-Cre mice for deletion of Adamts9 in the male germline. Male mice carrying both the Prm1-Cre and Adamts9fl transgenes were crossed with female mice to obtain mice with a germline deleted allele (designated Adamts9del) and lacking the Prm1-Cre transgene. Analysis of Adamts9del/+ adult mice revealed similar cardiac valve anomalies as previously described in Adamts9LacZ/+ mice (Kern et al., 2010) and a fully penetrant eye defect (Dubail et al, unpublished data), similar to that previously observed in Adamts9LacZ/+ mice (Koo et al., 2010). This suggested that germline targeting of the floxed allele had led to its inactivation and that Adamts9del was functionally equivalent to the previously described null (Adamts9LacZ) allele. Adamts9del/+ intercrosses failed to give any viable progeny and analysis of the gestational outcome at E7.5 identified several small, Adamts9del/del malformed embryos in a Mendelian ratio (Nandadasa et al, unpublished observation) consistent with embryonic death by E7.5 as previously reported in Adamts9lacZ/+ intercrosses (Kern et al., 2010). The analysis of these embryos is ongoing and will be reported elsewhere. Furthermore, in a complementation test, intercrosses of Adamts9del/+ male and Adamts9LacZ/+ female mice provided no Adamts9del/LacZ mice from 40 genotyped progeny (versus expected Mendelian proportion of 25%. i.e. 10 mice), nor were any Adamts9 del/LacZ embryos identified following Caesarian section at E9.5. Instead, of 25 E9.5 gestational products that were analyzed, 6 were necrotic and undergoing resorption, consistent with death within the prior 48 hours; these represented a Mendelian fraction of 25%.

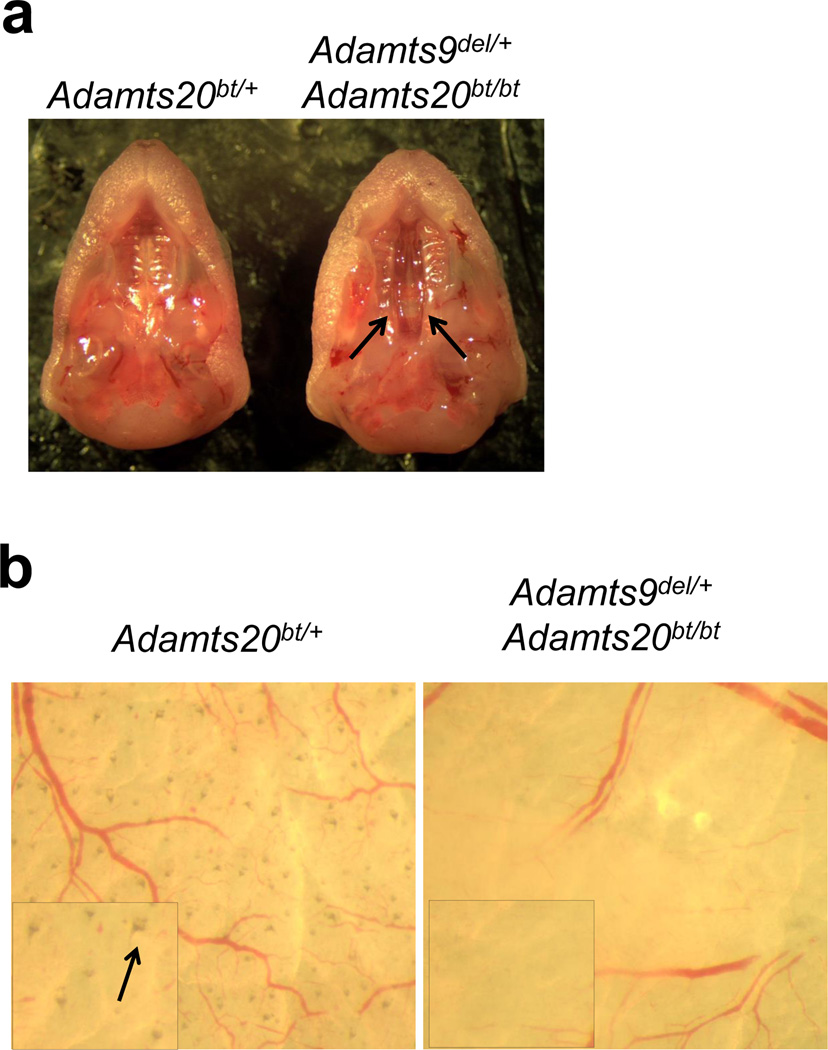

Next, we generated Adamts20bt/bt; Adamts9del/+ mice; these developed cleft palate with 100% penetrance as previously shown in Adamts20bt/bt; Adamts9LacZ/+ mice (Fig. 2a) (Enomoto, 2010), showed greatly reduced melanoblasts in hair follicles as previously reported (Fig. 2B) (Silver, 2008) and developed STS (Fig.S1). Taken together, comparable phenotypes as the previously described Adamts9LacZ allele in the hemizygous as well as null state, failure to complement, and identical phenotypes in combination with Adamts20bt demonstrated correct gene targeting and validated the Adamts9fl allele for subsequent Cre-mediated excision.

Figure 2. Validation of Adamts9 targeting by combinatorial mutagenesis with an Adamts20 allele.

a. Palates of newborn mice of the indicated genotypes viewed from the inferior aspect after removal of the mandible. Note the complete cleft palate of the secondary palate of the Adamts9del /+;Adamts20bt/bt mouse on the right (arrows indicate medial edges of the palate shelves). b. Torso skin from newborn mice was dissected free of subcutaneous fat and viewed from the dermal aspect. Adamts20bt/+ mice have pigmented hair follicles, whereas Adamts9del/+;Adamts20bt/bt follicles are unpigmented or have low pigment levels. The boxed inset images show a higher magnification, with the arrows in Adamts20bt/+ mice pointing to a normal pigmented hair follicle, which are not seen in Adamts9del /+;Adamts20bt/bt skin.

Previous work had shown strong Adamts9 expression in interdigital webs of developing limbs that coincided temporally with the regression of these webs and overlapped with the expression of Vcan, Adamts5 and Adamts20 (McCulloch et al., 2009). In previously published work, we demonstrated that mice lacking Adamts5 or Adamts20 alone had a low penetrance of STS, and that Adamts9 haploinsufficiency alone did not cause STS (McCulloch et al., 2009). When present, STS in Adamts5lacZ/lacZ mice was seen in the hindlimbs, whereas in Adamt20bt/bt mice, it was in the forelimbs (McCulloch et al., 2009). When the null mutant of either gene was made haploinsufficient for Adamts9, the combinatorial mutants had a higher penetrance of syndactyly than mice lacking either Adamts20 or Adamts5 alone, and a greater extent of soft tissue fusion along the length of the digits (McCulloch et al., 2009). Thus, Adamts9 cooperated with Adamts5 and Adamts20 in web regression, but because of early death of Adamts9lacZ /lacZ mice, the non-redundant role of Adamts9 in limb development, as well as its cooperative role with other ADAMTS proteases was not fully elucidated.

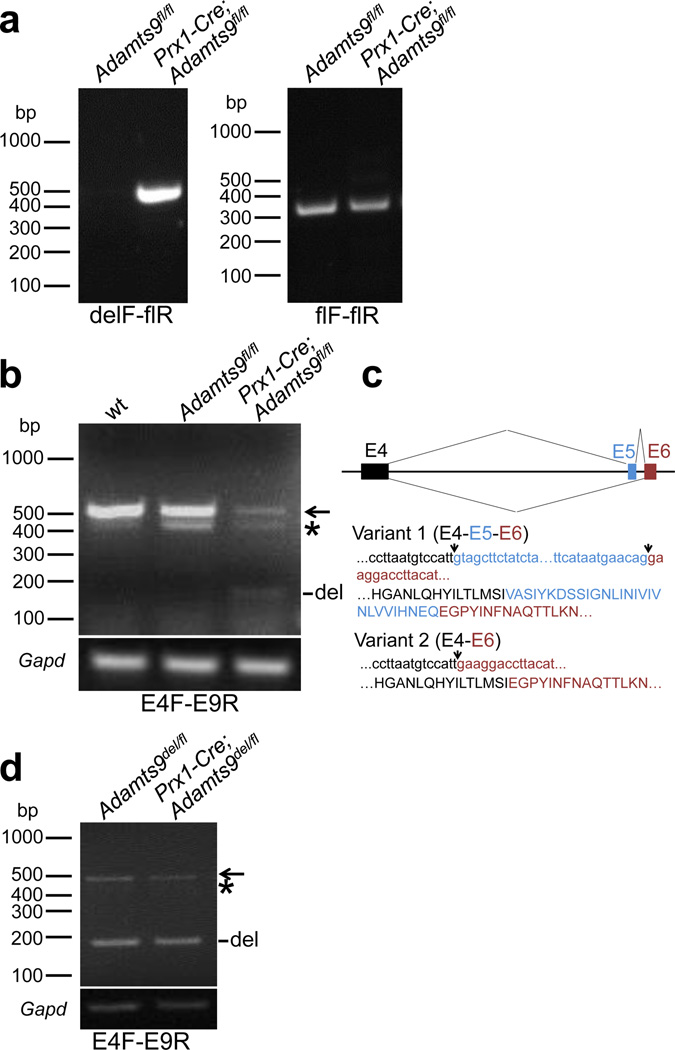

For this reason, we used the Prx1-Cre strain for deletion of Adamts9 in limb mesoderm. The Prx1 promoter region that drives Cre in this mouse strain was previously shown to be active in the mesenchyme, but not the ectoderm of both fore- and hindlimbs from the earliest stages of limb bud development (i.e. from E9.5) and in a subset of craniofacial mesenchyme (Logan et al., 2002). We generated Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl and Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/del mice as well as Prx1-Cre and Adamts9fl/fl littermates as controls. Excision of exons 5–8 in the limb mesoderm of Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl mice was confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Verification of Adamts9 conditional deletion.

a. Confirmation of limb mesoderm specific deletion by PCR analysis. Left-hand panel: PCR of hindlimb muscle genomic DNA (gDNA) with the indicated primers provides a specific amplicon of the expected size only in the conditional mutant. Right-hand panel: PCR of gDNA with the indicated primer pair shows that there is persistence of some undeleted Adamts9 gene in Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl mice. b. RT-PCR of muscle cDNA shows reduction of intact Adamts9 RNA (500 bp) in Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl mice, with the appearance of a 180 bp deleted band (Del). All three lanes show a novel alternatively spliced variant of Adamts9 (asterisk). c. Novel splice variant of Adamts9 identified by RT-PCR. The cartoon at top shows exons 4–6, with the splicing patterns indicated. The sequences shown below this include the nucleotide sequence of the amplicons identified in b and their translated product (single amino acid code). d. RT-PCR shows that Prx1-Cre; Adamts9del/fl muscle cDNA has less intact mRNA than Adamts9del/fl muscle. The arrow indicates intact RNA, whereas del identifies the 180bp band arising from targeted mRNA. The asterisk indicates a faint band corresponding to the splice variant 2 RT-PCR product, which is at much lower levels here than in panel b, since these mice contain only one intact allele.

RT-PCR of mRNA prepared from Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl and Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/del hindlimb skeletal muscle (quadriceps) confirmed gene deletion by identifying a band of the size expected after deletion (Fig. 3b, lane 3). As an incidental finding, RT-PCR to validate conditional deletion of mRNA (Fig. 3b) identified a novel splice variant of ADAMTS9 (Fig. 3c, variant 2) with skipping of exon 5. Variant 2 affects the propeptide, which has 28 fewer amino acids than variant 1, but maintains the ADAMTS9 open reading frame without altering the number of Cys residues, which are crucial for disulfide bond formation (Fig. 3c). The presence of both variants in RNA from a number of tissues other than limb muscle obtained from wild-type mice and Adamts9fl/fl mice (Fig. S2) suggests that Adamts9 alternative splicing is widespread, and was not a consequence of loxP insertion in intron 4. This is the first reported ADAMTS9 splice variant.

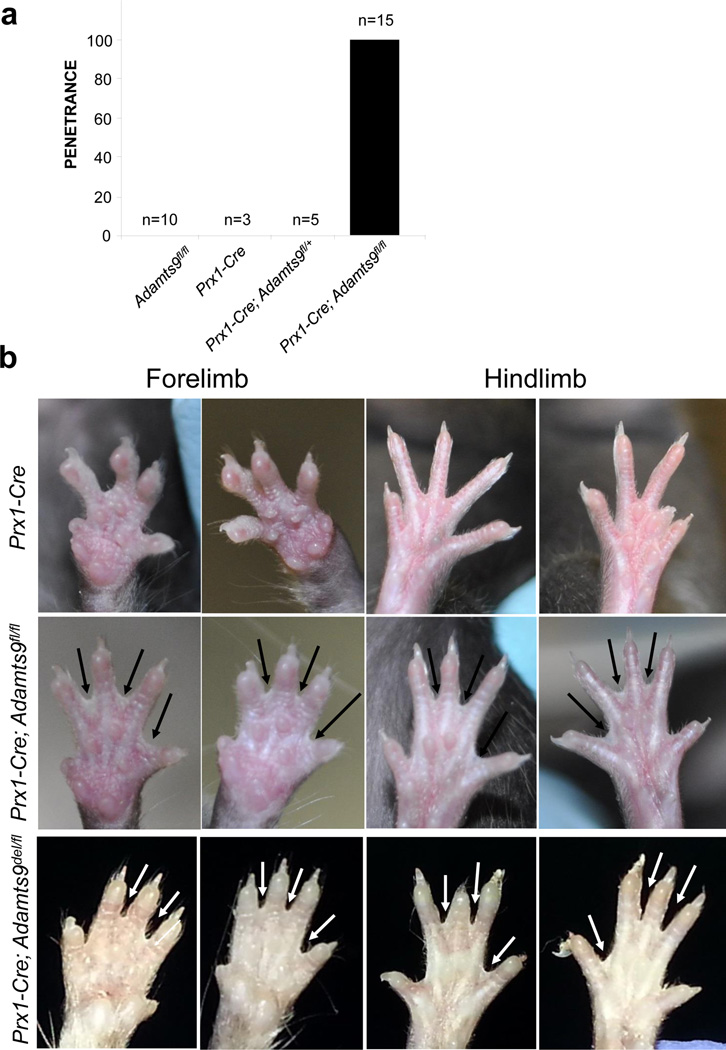

Residual intact Adamts9 mRNA was seen in both Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl and Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/del muscle, despite the latter presenting only a single floxed allele for Cre-mediated excision (Fig. 3b,d). However, it should be clarified, that because of the likely instability of the deleted Adamts9 mRNA, its precise amount is likely to be seriously underestimated, as is indeed suggested by Fig. 3b; thus, a small amount of undeleted mRNA may well be amplified preferentially in the absence of significant amounts of the deleted, shorter mRNA. Indeed, both Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl and Prx1-Cre; Adamts9del/fl mice developed STS (defined as persistent webs in any interdigit) with 100% penetrance, and were indistinguishable from each other in regard to the number of interdigits affected and the extent of fusion along the digits (Fig. 4b). This finding strongly suggests similar efficacy of functional loss in Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl and Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/del mice.

Figure 4. Penetrance and phenotype of soft tissue syndactyly (STS) in Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl mice.

a. Histogram of penetrance of the indicated genotypes. b. Representative STS phenotypes in mice of the indicated genotypes. Limbs from a Prx1-Cre mouse serve as the control. Arrows indicate unregressed interdigital webs. Note the similar phenotype in Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl and Prx1-Cre; Adamts9del/fl mice. The missing toes were removed for genotyping and are not a manifestation of this phenotype.

STS was not seen in Prx1-Cre or Adamts9fl/fl mice, the controls for these experiments (Fig. 4a,b) or in Adamtsdel/+ or Adamts9del/fl mice(Fig. S1). In contrast to STS previously described in Adamts5lacZ/lacZ; Adamts20bt/bt, or Adamts5lacZ/lacZ;Adamts9lacZ/+ mice (McCulloch et al., 2009), which primarily affected the interdigits 2–3 and 3–4, Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl and Prx1-Cre; Adamts9del/fl mice consistently developed STS of all the interdigits, although the webs did not extend to the tips of the digits (Fig. 4b). In contrast to Adamts20bt/bt or Adamts5lacZ/lacZ mouse limbs, in which STS primarily affects the forelimbs or hindlimbs respectively (McCulloch et al., 2009), STS was present in all forelimbs and all hindlimbs of Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl and Prx1-Cre; Adamts9del/fl mice. Screening of limb skeletons by micro-CT, planar radiography, or skeletal preparations with Alizarin-red and Alcian blue staining did not reveal any structural anomalies of bone or patterning anomalies (Fig. S3).

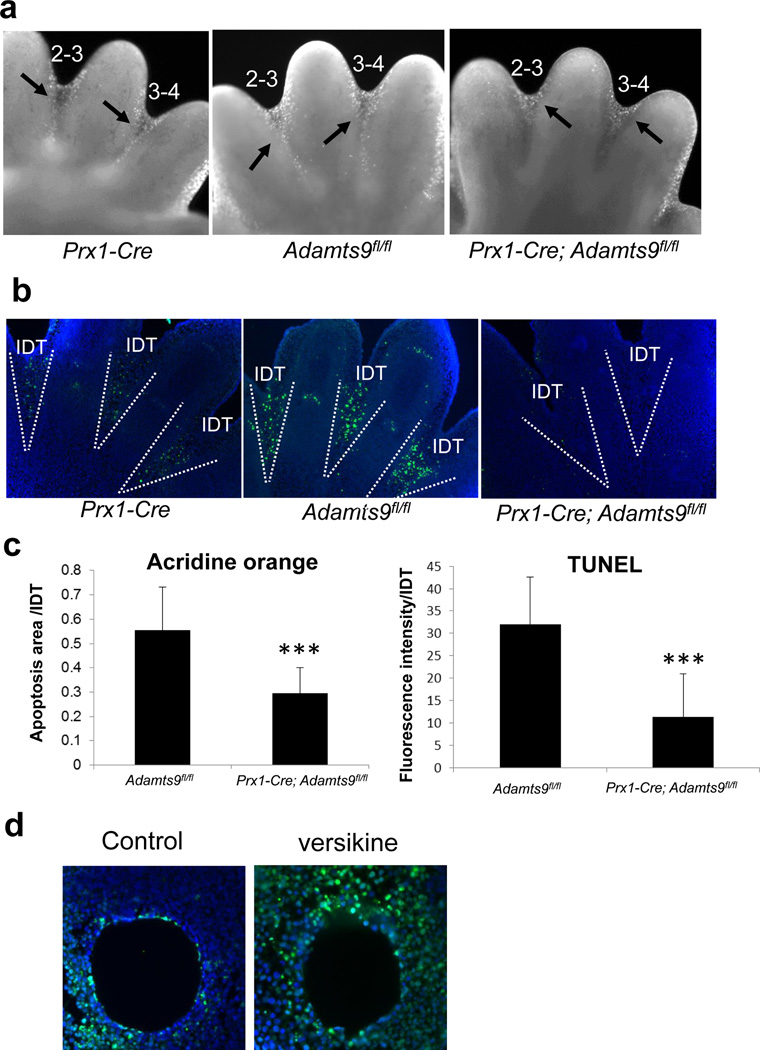

Notably, of the various ADAMTS single gene deletions undertaken to date, only that of Adamts9, which is reported here for the first time, has led to STS with 100% penetrance. Analysis of programmed cell death during regression of the web using either acridine orange staining or TUNEL staining showed fewer labeled cells in Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl webs (Fig. 5a–c). Previously, we showed that STS in Adamts5lacZ/lacZ; Adamts20bt/bt mice was associated with reduced versican proteolysis (McCulloch et al., 2009). Furthermore, we had shown that apoptosis could be induced in Adamts5lacZ/lacZ; Adamts20bt/bt webs by application of G1-versikine Indeed, insertion of a versikine-impregnated bead into the hindlimb (interdigit space 2–3) of Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl mice induced cell death compared to a control bead soaked in culture medium alone (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5. Reduced apoptosis in interdigital webs of Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl mice.

a. Acridine orange staining of E14.5 hindlimb autopods indicates reduced extent of apoptosis in the Prx1-Cre;Adamts9fl/fl webs compared to Prx1-Cre control (labeled cells are seen as white spots in the interdigital web). Note that apoptosis is restricted only to the distal part of the web in the Prx1-Cre;Adamts9fl/fl webs compared to the Prx1-Cre control. b. TUNEL assay on paraffin sections from E14.5 hindlimbs (TUNEL labeled cells are green, nuclei are blue). The dotted white lines indicate the boundaries of the webs. c. Quantification of the area occupied by acridine orange-positive cells in interdigital webs. n=10, *** p<0.001. d. Quantification of TUNEL immunostaining intensity per interdigital webs. n=8, *** p<0.001. e. TUNEL staining of the interdigit 3–4 from Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl hindlimbs after bead implantation. A bead soaked in versikine leads to more apoptosis (apoptotic cells are green, nuclei are blue) compared to a bead soaked in BSA (control).

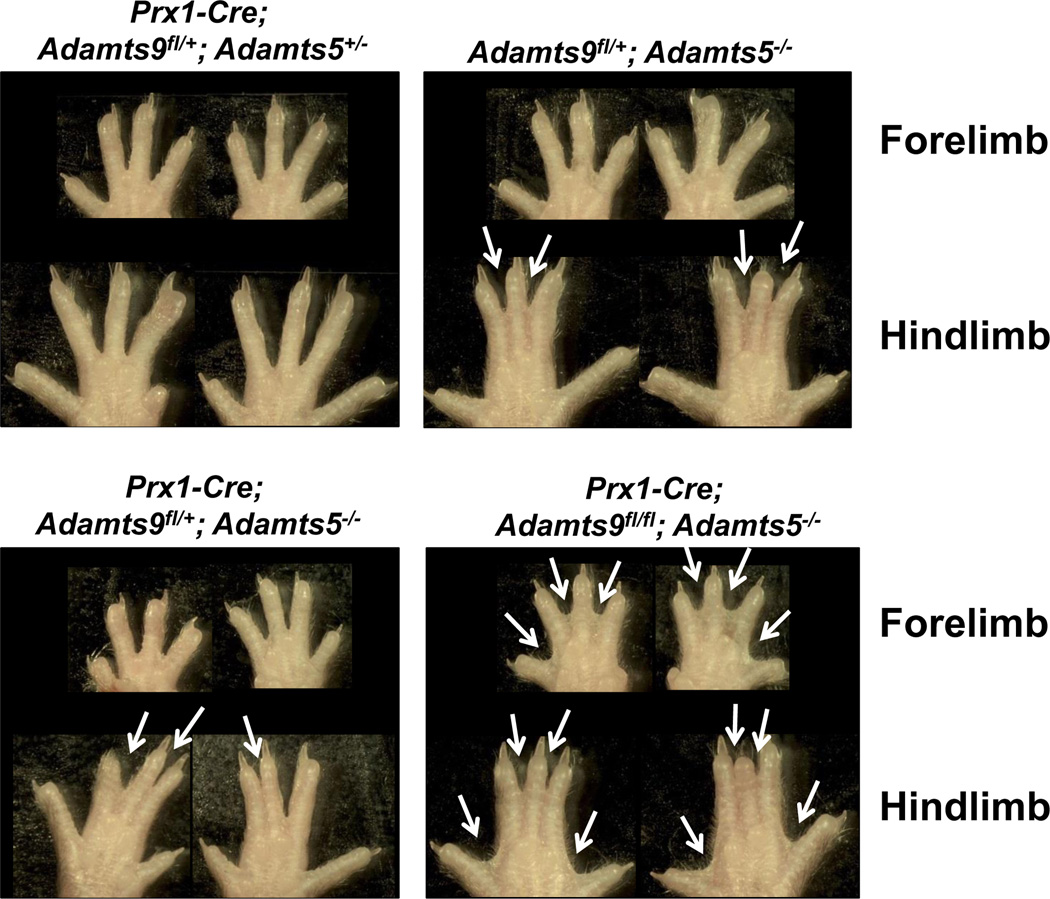

To elucidate the cooperative contribution that ADAMTS9 might make with another ADAMTS proteinase in interdigital web regression, we generated Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl; Adamts5lacZ/lacZ mice. While these mice had a 100% incidence of STS as expected, they also had greater severity than either null allele alone (Fig. 6, compare with Fig. 4). Taken together, these studies demonstrate the non-redundant and cooperative roles (with ADAMTS5) of ADAMTS9 in interdigital web regression. In addition to Adamts9, Adamts5, and Adamts20, whose contribution to web regression has been characterized here and in a previous publication (McCulloch et al., 2009), at least one other versican-degrading protease gene is expressed concurrently in the interdigital webs during their resorption, namely Adamts1 (Thai and Iruela-Arispe, 2002). Thus, there is likely a substantially greater cooperativity in ADAMTS-mediated web regression than presently apparent, which remains to be experimentally elucidated.

Figure 6. Combinatorial inactivation of Adamts9 and Adamts5 has an additive effect in STS.

The panels show distal forelimbs and hindlimbs from the indicated genotypes. Syndactylous webs are indicated by the white arrows. n=3. Compare with STS resulting from deficiency of Adamts9 alone shown in Figure 4.

The present work provides a new mouse model for further dissection of web regression and other developmental roles of Adamts9 using lineage-specific deletion singly or in combination with other ADAMTS genes as shown here. In addition to limb development, such studies are ongoing in our laboratory in the context of potential developmental roles in the eye, cardiovascular system and craniofacial tissues. Perhaps more importantly, it will allow rigorous analysis of human disorders in which ADAMTS9 is increasingly implicated by microarray analysis and GWAS. In addition to cancer, diabetes, obesity, and age-related macular degeneration, which were mentioned previously, new evidence potentially implicates ADAMTS9 in oocyte competence (Huang et al., 2013), myometrial function during labor (Chaemsaithong et al., 2013), lung response to second-hand smoke (Xiao et al., 2012), and age at menopause(Pyun et al., 2013), as well as several other interesting associations. Conditional deletion using the new floxed allele overcomes the hurdle imposed by lethality of the null allele, and allows dissection of the underlying mechanisms by which ADAMTS9 participates in development and disease pathways.

Materials and Methods

Construction of the targeting vector

The Adamts9 allele was engineered using a 10.68 kb region subcloned from a C57BL/6 BAC clone (RP23:379C7) by flanking exons 5–8 with unidirectional loxP sites. A loxP site is also located adjacent to the FRT flanked cassette for neomycin resistance (Neo) (from pGK-gb2 LoxP/FRT Neo) inserted 299 bp upstream of exon 5 (Fig. 1a). The short 5´ homology arm extended 1.76 kb upstream of the selection cassette, whereas the longer 3´ homology arm extended 6.86 kb downstream of exon 8. The region targeted for deletion by Cre-recombinase (exons 5–8) is 2.06 kb. The targeting vector underwent restriction mapping and nucleotide sequencing after each modification step, i.e., to read into the 5´ and 3´ ends of the construct, to verify the 5´ and 3´ ends of the LoxP/FRT Neo cassette and to sequence the homology arms, respectively. The engineered BAC was cloned into a ~2.4kb backbone vector (pSP72, Promega Corp, Madison, WI) containing an ampicillin selection cassette for amplification of the construct prior to electroporation. The total size of the targeting construct (including vector backbone) was 14.78 kb.

Generation of mice carrying the floxed Adamts9 allele

The targeting construct was linearized using restriction endonuclease Not I prior to electroporation into ITL IC1 embryonic stem (ES) cells of C57BL/6 origin (Ingenious Targeting Laboratories, Inc, Stony Brook, NY). ES cell clones surviving G418 selection were analyzed by Southern blot analysis of Nhe I digested genomic DNA using a probe external to the 3´ arm of the construct and a 5´ probe within the short 5´ arm of the construct (Fig. 1a, b). Correctly targeted ES cells were microinjected into Balb/c blastocysts. Resulting chimeras with a high percentage black coat color were mated to wild-type C57BL/6 mice to generate F1 hemizygous progeny. Tail DNA from pups with black coat color was used for genotyping by PCR as described below. The Neo cassette was deleted by crossing Adamts9fl-Neo/+mice to hACTB-FLPe mice (B6.Cg-Tg(ACTFLPe)9205Dym/J; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Progeny with Neo deletion were bred to wild-type C57BL/6 mice to ensure germline transmission and eliminate the hACTB-FLPe transgene. The floxed allele was subsequently maintained in this form (designated as Adamts9fl/+). These animal experiments were conducted in compliance with all relevant institutional and national animal welfare laws and with the approval of the Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The new alleles Adamts9fl/+ and Adamts9del/+ that are described here are available to the research community upon request.

Germline deletion, conditional deletion of Adamts9 in limb mesoderm and combinatorial deletion with Adamts5

For deletion in the male germline, Prm1-Cre mice (B6Ei.129S4-Tg(Prm1-cre)58Og/EiJ; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were crossed to Adamts9fl-neo/+ mice. Male mice carrying both transgenes were selected by PCR genotyping (see below). These were bred to wild-type C57BL/6 mice to select mice bearing the deleted allele (Adamts9del/+) but not Prm1-Cre. Successful excision of the neo cassette was also verified by sequencing PCR products. Adamts9del/+ mice were subsequently intercrossed and the vaginal plug was used to determine potential fertilization (The morning the plug was observed was designated as E0.5). Pregnant dams were sacrificed at E7.5, E8.5, or E9.5. These embryos and live born progeny were genotyped to ascertain survival of Adamts9del/del progeny. For limb-specific conditional deletion, Prx1-Cre mice (B6.Cg-Tg(Prrx1-cre)1Cjt/J, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were crossed to Adamts9fl/+ mice. For conditional deletion, male Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/+ or Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl mice were bred to Adamts9fl/fl or Adamts9del/+ mice respectively to obtain mice with conditional deletion (Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl or Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/del) in limb mesoderm.

Planar radiography and micro-computerized tomography

Planar radiographs were obtained at post-mortem using an In-vivo DXS Pro instrument equipped with Kodak DXS software (Bruker Biospin Corp., Billerica, MA). High-resolution micro-CT images of limbs were acquired using the Xradia MicroXCT-200 system (Pleasanton, CA, USA.) The following parameters were used for acquisition: 1600 views in a 360° rotation with an exposure time of 10 sec per radiograph. A macro lens was used without a filter and the system was set at a 50 kV/8 W source setting. Images were generated using 3D viewing software (3D viewer) provided with the Xradia scanner.

Tissue analysis

E14.5 hindlimb autopods were stained with acridine orange and photographed as previously described (McCulloch et al., 2009). Fixation with 4% PFA was followed by paraffin embedding. 5 µm thick sections were analyzed using the TUNEL assay as previously described (McCulloch et al., 2009). Labeling was quantified using ImageJ® software. Experimental manipulation of Prx1-Cre; Adamts9fl/fl hindlimb autopods for insertion of beads soaked in culture medium containing versikine or in control medium lacking versikine was as previously described (McCulloch et al., 2009). MicroCT, X-ray, Alizarin-red and Alcian blue staining of skeletal preparations was done as previously described (Kaufman, 1992; McCulloch et al., 2009)

Genotyping

Successful deletion of exons 5–8 was detected by PCR of gDNA using primers in intron 4 (delF: 5' GTAAGCACCAGCTAACACAG3') and intron 8 (flR: 5' ATGTTGAGCCAAGAAAGTTC3') which provided a 450 bp product (Fig. 1a, 3a). The presence of the undeleted floxed Adamts9 band was determined by PCR using the primers flF (5'TTCAGAGTAGATTTGGCAGGA3') and flR (5' ATGTTGAGCCAAGAAAGTTC 3') (Fig. 1a). For RT-PCR, RNA was isolated from quadriceps muscle using Trizol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Adamts9 cDNA primers used were E4F (5'CCCACGGTTTGTAGAGGTGA3') and E9R (5'TGTTGGTGCCTAGACATGCT3'). Gapd PCR was used as an indicator of cDNA quantity (Forward: 5'GCACAGTCAAGGCCGAGAAT3'; Reverse: 5' GCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAA3') Primer sequences used for detection of Cre and hACTB-FLPe transgenes were those recommended by Jackson Laboratories (www.jax.org).

Supplementary Material

a. The panels show distal forelimbs and hindlimbs of E15.0 embryos from the indicated genotypes. Syndactylous webs are indicated by the white arrows. b. The panels show distal forelimbs and hindlimbs from the indicated genotypes. The missing toes were removed for genotyping and are not a manifestation of the phenotype. c. Acridine orange staining of E13.5 forelimb autopods of Adamts9del/+ mice shows normal extent of apoptosis (labeled cells are white).

RT-PCR of mRNA isolated from various organs show variable expression of variant RNA 1 (arrow) and variant 2 (asterisk). Gapd RT-PCR was used as a measure of RNA.

a. micro-CT of 10-day old femurs of the indicated genotypes shows no anomalies. b. Planar X-ray of 10-day old tibias of the indicated genotype shows no anomalies. c. Alizarin-red and Alcian blue staining of 10-day old limbs of the indicated genotypes shows normal patterning.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Programs of Excellence in Glycosciences Initiative of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH P01 HL107147 to S.A.) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) at NIH (NIH RO1 HD069747 to S.A.). J.D. was supported by a Pediatric Opthalmology Career-Starter Research Grant from the Knights Templar Eye Foundation, Inc. H.L.B. was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from National Institutes of Health T32HL007914-08 (Training Program in Vascular Biology and Pathology, Principal Investigator: Edward Plow). We thank Kristen Llorens, Lisa Aronov and Anne Schirmer of ITL Inc., for their role in generation of the targeted allele.

Abbreviations

- ADAMTS9

A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease domain with thrombospondin type 1 motifs 9

- ECM

extracellular matrix

References

- Apte SS. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin-type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif (ADAMTS) superfamily: functions and mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31493–31497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.052340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blelloch R, Anna-Arriola SS, Gao D, Li Y, Hodgkin J, Kimble J. The gon-1 gene is required for gonadal morphogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1999;216:382–393. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaemsaithong P, Madan I, Romero R, Than NG, Tarca AL, Draghici S, Bhatti G, Yeo L, Mazor M, Kim CJ, Hassan SS, Chaiworapongsa T. Characterization of the myometrial transcriptome in women with an arrest of dilatation during labor. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:665–681. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2013-0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ME, Kelner GS, Turbeville LA, Boyer A, Arden KC, Maki RA. ADAMTS9, a novel member of the ADAM-TS/ metallospondin gene family. Genomics. 2000;67:343–350. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Wang S, Zhou Q, Li X, Chu J, Chang Z, Tao Q, Ng EK, Fang J, Sung JJ, Yu J. ADAMTS9 is a functional tumor suppressor through inhibiting AKT/mTOR pathway and associated with poor survival in gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto H, Nelson C, Somerville RPT, Mielke K, Dixon L, Powell K, Apte SS. Cooperation of two ADAMTS metalloproteases in closure of the mouse palate identifies a requirement for versican proteolysis in regulating palatal mesenchyme proliferation. Development. 2010;137:4029–4038. doi: 10.1242/dev.050591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heid IM, Jackson AU, Randall JC, Winkler TW, Qi L, Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Zillikens MC, Speliotes EK, Magi R, Workalemahu T, White CC, Bouatia-Naji N, Harris TB, Berndt SI, Ingelsson E, Willer CJ, Weedon MN, Luan J, Vedantam S, Esko T, Kilpelainen TO, Kutalik Z, Li S, Monda KL, Dixon AL, Holmes CC, Kaplan LM, Liang L, Min JL, Moffatt MF, Molony C, Nicholson G, Schadt EE, Zondervan KT, Feitosa MF, Ferreira T, Allen HL, Weyant RJ, Wheeler E, Wood AR, Estrada K, Goddard ME, Lettre G, Mangino M, Nyholt DR, Purcell S, Smith AV, Visscher PM, Yang J, McCarroll SA, Nemesh J, Voight BF, Absher D, Amin N, Aspelund T, Coin L, Glazer NL, Hayward C, Heard-Costa NL, Hottenga JJ, Johansson A, Johnson T, Kaakinen M, Kapur K, Ketkar S, Knowles JW, Kraft P, Kraja AT, Lamina C, Leitzmann MF, McKnight B, Morris AP, Ong KK, Perry JR, Peters MJ, Polasek O, Prokopenko I, Rayner NW, Ripatti S, Rivadeneira F, Robertson NR, Sanna S, Sovio U, Surakka I, Teumer A, van Wingerden S, Vitart V, Zhao JH, Cavalcanti-Proenca C, Chines PS, Fisher E, Kulzer JR, Lecoeur C, Narisu N, Sandholt C, Scott LJ, Silander K, Stark K, Tammesoo ML, Teslovich TM, Timpson NJ, Watanabe RM, Welch R, Chasman DI, Cooper MN, Jansson JO, Kettunen J, Lawrence RW, Pellikka N, Perola M, Vandenput L, Alavere H, Almgren P, Atwood LD, Bennett AJ, Biffar R, Bonnycastle LL, Bornstein SR, Buchanan TA, Campbell H, Day IN, Dei M, Dorr M, Elliott P, Erdos MR, Eriksson JG, Freimer NB, Fu M, Gaget S, Geus EJ, Gjesing AP, Grallert H, Grassler J, Groves CJ, Guiducci C, Hartikainen AL, Hassanali N, Havulinna AS, Herzig KH, Hicks AA, Hui J, Igl W, Jousilahti P, Jula A, Kajantie E, Kinnunen L, Kolcic I, Koskinen S, Kovacs P, Kroemer HK, Krzelj V, Kuusisto J, Kvaloy K, Laitinen J, Lantieri O, Lathrop GM, Lokki ML, Luben RN, Ludwig B, McArdle WL, McCarthy A, Morken MA, Nelis M, Neville MJ, Pare G, Parker AN, Peden JF, Pichler I, Pietilainen KH, Platou CG, Pouta A, Ridderstrale M, Samani NJ, Saramies J, Sinisalo J, Smit JH, Strawbridge RJ, Stringham HM, Swift AJ, Teder-Laving M, Thomson B, Usala G, van Meurs JB, van Ommen GJ, Vatin V, Volpato CB, Wallaschofski H, Walters GB, Widen E, Wild SH, Willemsen G, Witte DR, Zgaga L, Zitting P, Beilby JP, James AL, Kahonen M, Lehtimaki T, Nieminen MS, Ohlsson C, Palmer LJ, Raitakari O, Ridker PM, Stumvoll M, Tonjes A, Viikari J, Balkau B, Ben-Shlomo Y, Bergman RN, Boeing H, Smith GD, Ebrahim S, Froguel P, Hansen T, Hengstenberg C, Hveem K, Isomaa B, Jorgensen T, Karpe F, Khaw KT, Laakso M, Lawlor DA, Marre M, Meitinger T, Metspalu A, Midthjell K, Pedersen O, Salomaa V, Schwarz PE, Tuomi T, Tuomilehto J, Valle TT, Wareham NJ, Arnold AM, Beckmann JS, Bergmann S, Boerwinkle E, Boomsma DI, Caulfield MJ, Collins FS, Eiriksdottir G, Gudnason V, Gyllensten U, Hamsten A, Hattersley AT, Hofman A, Hu FB, Illig T, Iribarren C, Jarvelin MR, Kao WH, Kaprio J, Launer LJ, Munroe PB, Oostra B, Penninx BW, Pramstaller PP, Psaty BM, Quertermous T, Rissanen A, Rudan I, Shuldiner AR, Soranzo N, Spector TD, Syvanen AC, Uda M, Uitterlinden A, Volzke H, Vollenweider P, Wilson JF, Witteman JC, Wright AF, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M, Borecki IB, Deloukas P, Frayling TM, Groop LC, Haritunians T, Hunter DJ, Kaplan RC, North KE, O'Connell JR, Peltonen L, Schlessinger D, Strachan DP, Hirschhorn JN, Assimes TL, Wichmann HE, Thorsteinsdottir U, van Duijn CM, Stefansson K, Cupples LA, Loos RJ, Barroso I, McCarthy MI, Fox CS, Mohlke KL, Lindgren CM. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist-hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ng.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helisalmi S, Immonen I, Losonczy G, Resch MD, Benedek S, Balogh I, Papp A, Berta A, Uusitupa M, Hiltunen M, Kaarniranta K. ADAMTS9 locus associates with increased risk of wet AMD. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/aos.12341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Hao C, Shen X, Zhang Y, Liu X. RUNX2, GPX3 and PTX3 gene expression profiling in cumulus cells are reflective oocyte/embryo competence and potentially reliable predictors of embryo developmental competence in PCOS patients. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:109. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley-Jones J, Apte SS, Robertson DL, Boot-Handford RP. The characterisation of six ADAMTS proteases in the basal chordate Ciona intestinalis provides new insights into the vertebrate ADAMTS family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1838–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismat A, Cheshire AM, Andrew DJ. The secreted AdamTS-A metalloprotease is required for collective cell migration. Development. 2013;140:1981–1993. doi: 10.1242/dev.087908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungers KA, Le Goff C, Somerville RP, Apte SS. Adamts9 is widely expressed during mouse embryo development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MH. The Atlas Of Mouse Development. 1st ed. London: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kern CB, Wessels A, McGarity J, Dixon LJ, Alston E, Argraves WS, Geeting D, Nelson CM, Menick DR, Apte SS. Reduced versican cleavage due to Adamts9 haploinsufficiency is associated with cardiac and aortic anomalies. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo BH, Coe DM, Dixon LJ, Somerville RP, Nelson CM, Wang LW, Young ME, Lindner DJ, Apte SS. ADAMTS9 Is a Cell-Autonomously Acting, Anti-Angiogenic Metalloprotease Expressed by Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Am J Pathol. 2010 doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandoski M. Analysis of mouse development with conditional mutagenesis. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007:235–262. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-35109-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamazares M, Cal S, Quesada V, Lopez-Otin C. Identification and characterization of ADAMTS-20 defines a novel subfamily of metalloproteinases-disintegrins with multiple thrombospondin-1 repeats and a unique GON domain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13382–13389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo PH, Lung HL, Cheung AK, Apte SS, Chan KW, Kwong FM, Ko JM, Cheng Y, Law S, Srivastava G, Zabarovsky ER, Tsao SW, Tang JC, Stanbridge EJ, Lung ML. Extracellular Protease ADAMTS9 Suppresses Esophageal and Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Tumor Formation by Inhibiting Angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan M, Martin JF, Nagy A, Lobe C, Olson EN, Tabin CJ. Expression of Cre Recombinase in the developing mouse limb bud driven by a Prxl enhancer. Genesis. 2002;33:77–80. doi: 10.1002/gene.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung HL, Lo PH, Xie D, Apte SS, Cheung AK, Cheng Y, Law EW, Chua D, Zeng YX, Tsao SW, Stanbridge EJ, Lung ML. Characterization of a novel epigenetically-silenced, growth-suppressive gene, ADAMTS9, and its association with lymph node metastases in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:401–408. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch DR, Nelson CM, Dixon LJ, Silver DL, Wylie JD, Lindner V, Sasaki T, Cooley MA, Argraves WS, Apte SS. ADAMTS metalloproteases generate active versican fragments that regulate interdigital web regression. Dev Cell. 2009;17:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandadasa S, Foulcer S, Apte SS. The multiple, complex roles of versican and its proteolytic turnover by ADAMTS proteases during embryogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyun JA, Kim S, Cho NH, Koh I, Lee JY, Shin C, Kwack K. Genome-wide association studies and epistasis analyses of candidate genes related to age at menarche and age at natural menopause in a Korean population. Menopause. 2013 doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a433f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C, Foernzler D, Loftus SK, Liu S, McPherson JD, Jungers KA, Apte SS, Pavan WJ, Beier DR. A defect in a novel ADAMTS family member is the cause of the belted white-spotting mutation. Development. 2003;130:4665–4672. doi: 10.1242/dev.00668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CI, Buchholz F, Galloway J, Sequerra R, Kasper J, Ayala R, Stewart AF, Dymecki SM. High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat Genet. 2000;25:139–140. doi: 10.1038/75973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver DL, Hou L, Somerville R, Young ME, Apte SS, Pavan WJ. The secreted metalloprotease ADAMTS20 is required for melanoblast survival. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville RP, Longpre JM, Jungers KA, Engle JM, Ross M, Evanko S, Wight TN, Leduc R, Apte SS. Characterization of ADAMTS-9 and ADAMTS-20 as a distinct ADAMTS subfamily related to Caenorhabditis elegans GON-1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9503–9513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai SN, Iruela-Arispe ML. Expression of ADAMTS1 during murine development. Mech Dev. 2002;115:181–185. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R, Perveen Z, Paulsen D, Rouse R, Ambalavanan N, Kearney M, Penn AL. In utero exposure to second-hand smoke aggravates adult responses to irritants: adult second-hand smoke. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47:843–851. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0241OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, Voight BF, Marchini JL, Hu T, de Bakker PI, Abecasis GR, Almgren P, Andersen G, Ardlie K, Bostrom KB, Bergman RN, Bonnycastle LL, Borch-Johnsen K, Burtt NP, Chen H, Chines PS, Daly MJ, Deodhar P, Ding CJ, Doney AS, Duren WL, Elliott KS, Erdos MR, Frayling TM, Freathy RM, Gianniny L, Grallert H, Grarup N, Groves CJ, Guiducci C, Hansen T, Herder C, Hitman GA, Hughes TE, Isomaa B, Jackson AU, Jorgensen T, Kong A, Kubalanza K, Kuruvilla FG, Kuusisto J, Langenberg C, Lango H, Lauritzen T, Li Y, Lindgren CM, Lyssenko V, Marvelle AF, Meisinger C, Midthjell K, Mohlke KL, Morken MA, Morris AD, Narisu N, Nilsson P, Owen KR, Palmer CN, Payne F, Perry JR, Pettersen E, Platou C, Prokopenko I, Qi L, Qin L, Rayner NW, Rees M, Roix JJ, Sandbaek A, Shields B, Sjogren M, Steinthorsdottir V, Stringham HM, Swift AJ, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Timpson NJ, Tuomi T, Tuomilehto J, Walker M, Watanabe RM, Weedon MN, Willer CJ, Illig T, Hveem K, Hu FB, Laakso M, Stefansson K, Pedersen O, Wareham NJ, Barroso I, Hattersley AT, Collins FS, Groop L, McCarthy MI, Boehnke M, Altshuler D. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Shao Y, Zhang W, Wu Q, Yang H, Zhong Q, Zhang J, Guan M, Yu B, Wan J. High-resolution melting analysis of ADAMTS9 methylation levels in gastric, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;196:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

a. The panels show distal forelimbs and hindlimbs of E15.0 embryos from the indicated genotypes. Syndactylous webs are indicated by the white arrows. b. The panels show distal forelimbs and hindlimbs from the indicated genotypes. The missing toes were removed for genotyping and are not a manifestation of the phenotype. c. Acridine orange staining of E13.5 forelimb autopods of Adamts9del/+ mice shows normal extent of apoptosis (labeled cells are white).

RT-PCR of mRNA isolated from various organs show variable expression of variant RNA 1 (arrow) and variant 2 (asterisk). Gapd RT-PCR was used as a measure of RNA.

a. micro-CT of 10-day old femurs of the indicated genotypes shows no anomalies. b. Planar X-ray of 10-day old tibias of the indicated genotype shows no anomalies. c. Alizarin-red and Alcian blue staining of 10-day old limbs of the indicated genotypes shows normal patterning.