Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether experiences with illness and end-of-life care are associated with increased readiness to participate in advance care planning (ACP).

Design

Observational cohort study.

Setting

Community.

Participants

Persons age ≥ 60 recruited from physician offices and a senior center.

Measurements

Participants were asked about personal experience with major illness or surgery and experience with others’ end-of-life care, including whether they had made a medical decision for someone dying, knew someone who had a bad death due to too much/too little medical care, or experienced the death of a loved one who made end-of-life wishes known. Stages of change were assessed for specific ACP behaviors: completion of living will and healthcare proxy, communication with loved ones regarding life-sustaining treatments and quantity versus quality of life, and communication with physicians about these same topics. Stages of change included precontemplation, contemplation, preparation and action/maintenance corresponding to whether the participant was not ready to complete the behavior, was considering participation in the next six months, was planning participation within thirty days, or had already participated.

Results

Of 304 participants, 84% had one or more personal experiences or experience with others. Personal experiences were not associated with increased readiness for most ACP behaviors. In contrast, having one or more experiences with others was associated with increased readiness to complete a living will and healthcare proxy, discuss life-sustaining treatment with loved ones and discuss quantity versus quality of life with loved ones and with physicians.

Conclusion

Older individuals who have experience with end-of-life care for others demonstrate increased readiness to participate in ACP. Discussions with older patients regarding these experiences may be a useful tool in promoting ACP.

Keywords: advance care planning, end-of-life care

INTRODUCTION

Advance care planning (ACP) gives patients the opportunity to ensure that their preferences guide their care when they are unable to make their own decisions. It also serves to alleviate the burden placed on loved ones who might be called upon to act as surrogate decision makers.1,2 While advance directives have been the traditional forms of advance care planning, the importance of behaviors such as discussion and communication of preferences with loved ones and physicians is becoming increasingly recognized.3,4 Despite efforts to increase participation in ACP and completion of advance directives, ACP remains an underused tool in medical care.5

In order to better understand individual readiness for ACP, researchers have recently begun to examine ACP components as health behaviors using the Transtheoretical Model (TTM),6 which includes the concept of readiness to participate and provides a framework to examine ACP as a process of behavior change.3,4,7–9 Within this paradigm, different ACP activities such as completion of advance directives and discussions with family and physicians can be examined according to stages of change. The stages of change include precontemplation (no intention to change behavior in the near future), contemplation (thinking about changing behavior in the near future), preparation (commitment to changing behavior soon), action (a recent change in behavior), and maintenance (ongoing behavior change).6 Within this construct, individuals who are in more advanced stages of change demonstrate increased readiness to participate in ACP compared to those in earlier stages. Thus far, several studies have found that individuals are frequently in different stages of readiness for different ACP behaviors.3,4,10

Researchers have also examined both perceived benefits of and barriers to ACP to understand why individuals may or may not be ready to participate. These studies generally focus on the attitudes and beliefs held by participants. Perceived benefits that have been identified include managing affairs while still able, ensuring that wishes are met, peace of mind, decreasing burden on loved ones, and keeping peace within the family.3,11 Examples of barriers identified include irrelevance, difficulty thinking about dying, lack of knowledge, feeling that planning is unnecessary as family knows what to do, and feeling that loved ones are unable or unwilling to discuss ACP.3,12 In addition to these attitudes and beliefs, another factor that may affect an individual’s readiness to participate in ACP is life experiences. Prior experiences with illness and medical decision-making may be an important determinant in ACP and its perceived relevance to individuals. Several studies have examined the relationship between illness and end-of-life experiences and ACP, but findings have been contradictory.4,13–17

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between previous experience with illness and end-of-life decision-making with the stages of change for different ACP behaviors. Its specific aims were: 1) to determine what proportion of participants have had previous experience with illness and end-of-life decision-making; 2) to examine whether these experiences are associated with increased readiness to participate in ACP activities.

METHODS

Participants

Participants age 60 years and older were recruited from two primary care practices and one senior center for access to a group of participants diverse in race, socioeconomic status, and health status. In the primary care practices, letters were sent to older persons (58 and 347 persons in the two practices) who were screened by their physician as not having a diagnosis of dementia. Persons who agreed (92% and 88%) then underwent a telephone screen to determine exclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria included: non-English speaker (7% and 2%), hearing loss precluding interview participation (7% and 1%), nursing home resident (0% and 1%), acute illness (8% and 4%), and cognitive impairment defined as <2/3 recall on a test of short-term memory18 (7% and <1%). Among eligible participants, 83% and 80% completed interviews. In the senior center, volunteers were solicited for participation from amongst center attendees, and all 46 persons who volunteered were eligible for participation and completed interviews.

Data Collection

Participants were interviewed in person by trained research assistants. The development of the outcome measure used in this study, readiness to participate in a set of discrete ACP behaviors, has been described in detail previously.10 The behaviors were selected based on current conceptions of ACP as derived from a literature review of expert opinion commentaries on ACP and supplemented by focus groups to understand older adults’ experiences with ACP.3 The behaviors correspond to key objectives of ACP, including clarification of values and goals of care, improving patient-surrogate and patient-clinician communication and completion of advance directives.10 The six ACP behaviors include: a) completion of a living will; b) completion of a healthcare proxy; c) communication with loved ones regarding patients’ views about the use of life-sustaining treatments; d) communication with loved ones regarding patients’ views about quality versus quantity of life; e) communication between patient and physicians regarding patients’ views about the use of life-sustaining treatments; f) communication between patient and physicians about patients’ views about quality versus quantity of life. To determine the stage of change6 for each of these behaviors, patients were asked to choose from a fixed set of responses to indicate if they: a) had participated in the activity (action/maintenance), b) were planning to complete the activity within the next 30 days (preparation); c) were thinking about completing the activity in the next six months (contemplation); d) had not thought about or were not ready to participate in the activity (precontemplation). Representative algorithms for how the stages of change for the behaviors were assessed have been published previously.10

The survey included items to assess experiences with personal illness and end-of-life care. Participants were asked to respond yes or no to whether they had: a) faced a life-threatening illness; b) had a risky or major surgery; c) made a medical decision for someone who was dying; d) known someone who they believe had a bad death due to receiving too much medical care; e) known someone who they believe had a bad death due to receiving too little medical care; e) experienced the death of a loved one who made his or her wishes about end-of-life known.

In addition to the items measuring the stages of change for each ACP behavior and previous life experiences, the interview included measures of sociodemographic status such as age, gender, ethnicity, race, education, marital status, and sufficiency of monthly income.19 Health status was assessed with self-rated health (single-item global rating as poor, fair, good, very good or excellent),20 quality of life (single-item global rating as worst possible, poor, fair, good, or best possible), number of chronic conditions, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL),21 and depression (assessed with two questions addressing depressed mood and anhedonia).22 IADLs for which participants were asked to specify whether they needed no help, some help or could not perform at all included using the telephone, travelling, groceries, meal preparation, housework, medication management and finances. There were no missing responses on the questions of previous experiences or demographic data.

Analysis

Univariate statistics were used to describe the study population and characterize the stages of change for the ACP behaviors. Individual experiences with illness and end-of-life care associated with stages of change for the ACP behaviors were examined in bivariate analysis using the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test. Because of small cell sizes, an exact p-value for the statistic was calculated. Having one or more end-of-life experiences with others and the stages of change for each ACP behavior were also examined using the same method.

RESULTS

Description of Participants and their Previous Experiences

A description of the 304 participants is provided in Table 1. Of the 304 participants, 84% reported having personal experience with serious illness, surgery, and/or experience with end-of-life care for an acquaintance or loved one. Overall, 63% of participants had at least one personal illness or surgery experience, and 63% of participants had at least one end-of-life experience with others. The proportion of participants having each individual life experience is listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Description of Participants (N = 304)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean years ± SD, range, median (IQR) | 74.9 ± 7.1, 61–92, 74 (69, 80) |

| Female, n (%) | 223 (73) |

| Non-white ethnicity, n (%) | 80 (26) |

| Greater than high school education, n (%) | 188 (62) |

| Married, n (%) | 141 (46) |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 131 (43) |

| Chronic diseases, mean number ± SD | 3.8 ± 2.2 |

| ≥ 1 IADL impairment, n (%) | 61 (20) |

| Self-rated health fair or poor, n (%) | 65 (21) |

| Quality of life fair to worst, n (%) | 50 (16) |

SD = standard deviation

IQR = interquartile range

IADL = instrumental activities of daily living

Table 2.

Proportion of Participants with Illness and End-of-Life Care Experiences (N = 304)

| Experience | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Personal Experience | |

| Life-threatening illness | 117 (38.5) |

| Risky or major surgery | 163 (53.6) |

| Either life-threatening illness or surgery | 190 (62.5) |

| Experience with Others | |

| Medical decision for someone who died | 106 (34.9) |

| Known someone who had a bad death due to receiving too much medical care | 27 (8.9) |

| Known someone who had a bad death due to receiving too little medical care | 56 (18.4) |

| Experienced death of loved one who made wishes about end-of-life care known | 116 (38.2) |

| 1 or more experiences with others | 192 (63.2) |

| 1 or more personal experiences and/or experiences with others | 255 (83.9) |

Association between Life Experiences and Stages of Change for ACP Behaviors

Having a life-threatening illness was associated with increased readiness to communicate with loved ones regarding life-sustaining treatment (p = 0.03). Personal experiences with life-threatening illness or major surgery were otherwise not associated with being in later stages of change for the different ACP behaviors. Having experiences with others with regard to end-of-life care or decision-making was associated with increased readiness to participate in multiple ACP behaviors as shown in Table 3. While knowing someone who had a bad death due to receiving too much medical care was only associated with increased readiness to discuss quality versus quantity of life with physicians, having previously made a medical decision for someone who died was associated with more advanced stages of change for four of the six ACP behaviors measured.

Table 3.

Proportion of Participants at Each Stage of Change for ACP Behaviors According to Experience with Others

| PC | C | PR | A/M | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Decision for Someone Who Died |

n (%) | ||||

| Living Will | |||||

| Yes | 22 (21) | 14 (13) | 7 (7) | 63 (59) | 0.02 |

| No | 57 (29) | 41 (21) | 8 (4) | 92 (46) | |

| Discussed Life-Sustaining Treatment with Loved Ones | |||||

| Yes | 23 (22) | 7 (7) | 4 (4) | 72 (68) | 0.04 |

| No | 60 (30) | 19 (10) | 11 (6) | 108 (55) | |

| Discussed Quantity v Quality Life with Loved Ones* | |||||

| Yes | 30 (29) | 8 (8) | 6 (6) | 61 (58) | 0.001 |

| No | 92 (46) | 22 (11) | 2 (1) | 82 (41) | |

| Discussed Quantity v Quality Life with Physician† | |||||

| Yes | 70 (68) | 18 (17) | 3 (3) | 12 (12) | 0.001 |

| No | 155 (79) | 35 (18) | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | |

| Known Someone with Bad Death Because Too Much Care | |||||

| Discussed Quantity v Quality Life with Physician† | |||||

| Yes | 15 (58) | 6 (23) | 0 (0) | 5 (19) | 0.005 |

| No | 210 (77) | 47 (17) | 5 (2) | 11 (4) | |

| Known Someone with Bad Death Because Too Little Care | |||||

| Living Will | |||||

| Yes | 9 (16) | 6 (11) | 2 (4) | 39 (70) | 0.004 |

| No | 70 (28) | 49 (20) | 13 (5) | 116 (47) | |

| Healthcare Proxy‡ | |||||

| Yes | 12 (21) | 10 (18) | 3 (5) | 31 (55) | 0.001 |

| No | 98 (40) | 52 (21) | 23 (9) | 73 (30) | |

| Discussed Life-Sustaining Treatment with Loved Ones | |||||

| Yes | 7 (13) | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 42 (75) | 0.004 |

| No | 76 (31) | 22 (9) | 12 (5) | 138 (56) | |

| Discussed Quantity v Quality Life with Loved Ones* | |||||

| Yes | 15 (27) | 4 (7) | 2 (4) | 35 (63) | 0.009 |

| No | 107 (43) | 26 (11) | 6 (2) | 108 (44) | |

| Loved One Died with Wishes Known | |||||

| Discussed Life-Sustaining Treatment with Loved Ones | |||||

| Yes | 21 (18) | 10 (9) | 3 (3) | 82 (71) | 0.002 |

| No | 62 (33) | 16 (9) | 12 (6) | 98 (52) | |

| Discussed Quantity v Quality Life with Loved Ones* | |||||

| Yes | 36 (31) | 14 (12) | 4 (3) | 62 (53) | 0.03 |

| No | 86 (46) | 16 (9) | 4 (2) | 81 (43) | |

| Discussed Quantity v Quality Life with Physician† | |||||

| Yes | 79 (70) | 21 (19) | 2 (2) | 11 (10) | 0.01 |

| No | 146 (78) | 32 (17) | 3 (2) | 5 (3) | |

PC=pre-contemplation, C=contemplation, PR=preparation, A=action, M=maintenance

Data missing for one participant.

Data missing for five participants.

Data missing for two participants.

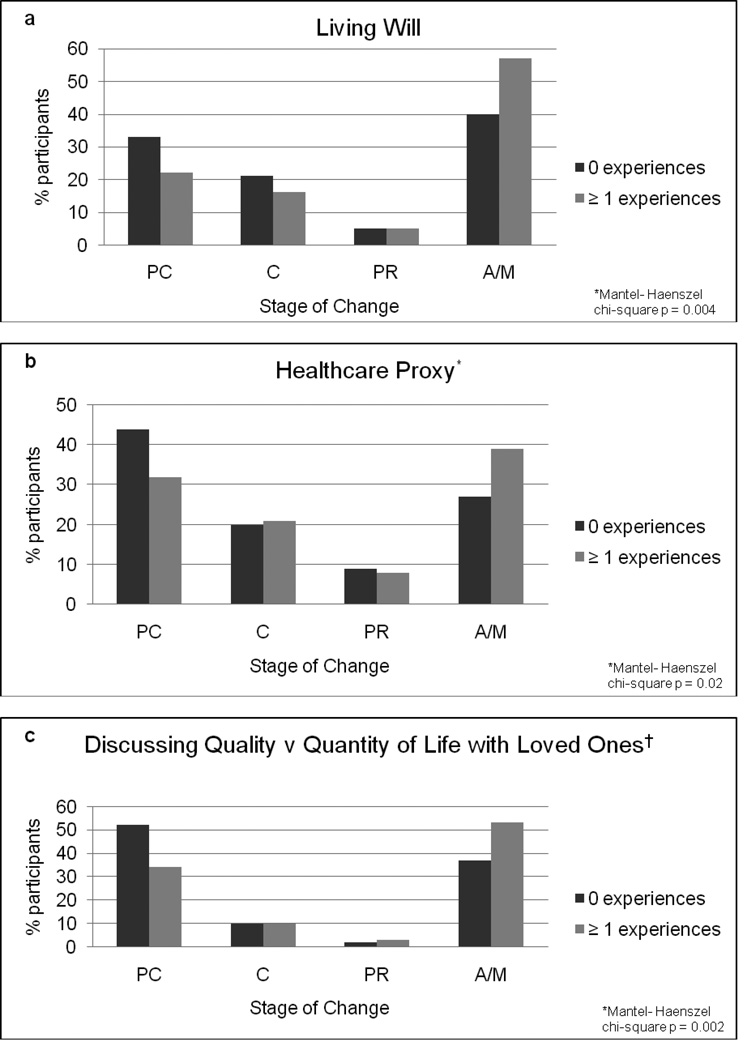

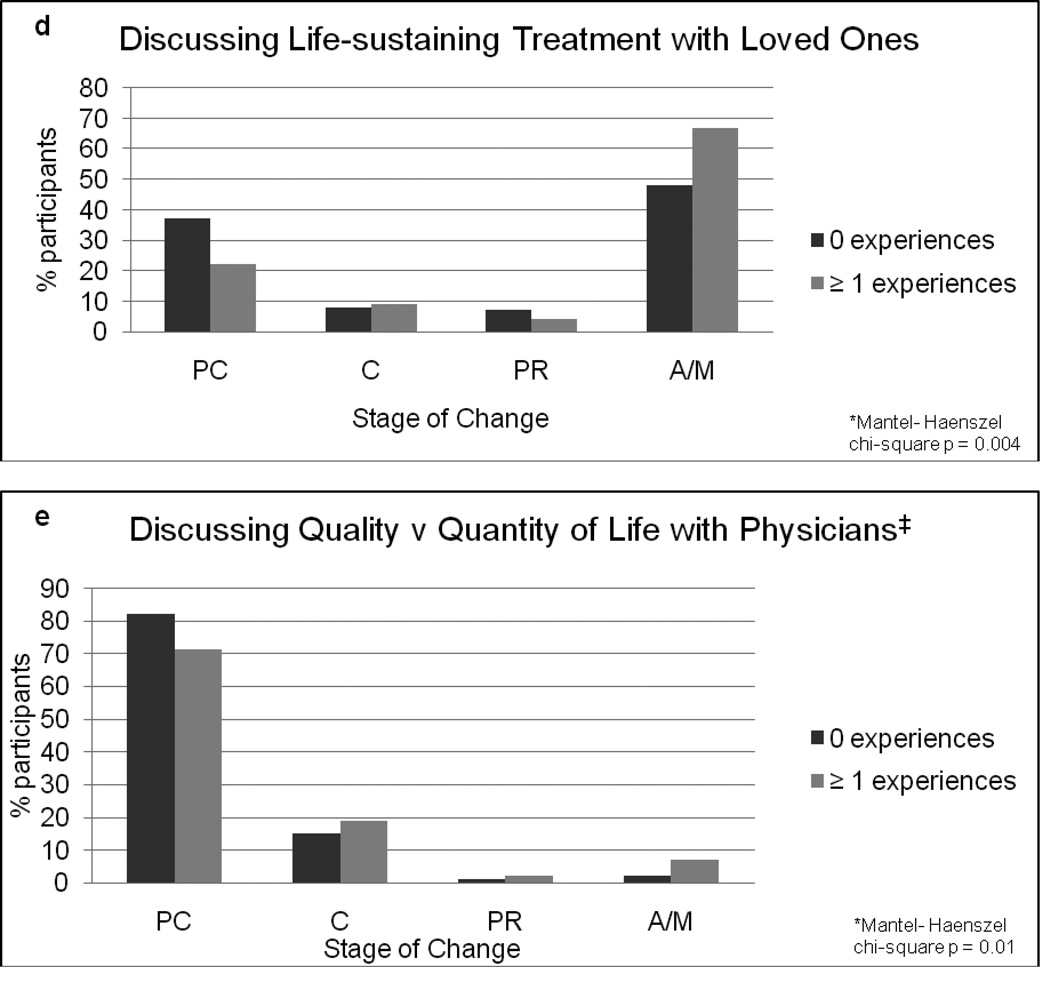

Figure 1 shows the proportion of participants in each stage of change for the different ACP behaviors according to whether they had none versus one or more end-of-life care experiences with others. Having at least one end-of-life care experience was associated with increased readiness to complete a living will and/or healthcare proxy, discuss life-sustaining treatment and quantity versus quality of life with loved ones, and discuss quantity versus quality of life with physicians.

Figure 1.

(a–e): Stages of change for different ACP behaviors according to number of end-of-life care experiences with others. The light gray bars represent the percentage of participants with one or more end-of-life care experiences with others. The dark gray bars represent the percentage of participants with no prior end-of-life care experiences.

PC=pre-contemplation, C=contemplation, PR=preparation, A=action, M=maintenance

*Data missing for two participants.

†Data missing for one participant.

‡Data missing for five participants.

DISCUSSION

In our study of older community-dwelling persons, 84% of participants reported having at least one personal experience, either with serious illness or surgery, or an experience with end-of-life care for a loved one. Personal experiences were common, with 63% of participants having faced serious illness or surgery. While the proportion of participants who reported having experiences with end-of-life care for others was variable across each individual experience, the majority of participants also had at least one of these experiences. Those who have had experience with end-of-life care and decision-making for others demonstrated increased readiness to participate in multiple aspects of ACP, including completion of a living will and/or healthcare proxy, discussion of life-sustaining treatment and quantity versus quality of life with loved ones, and discussion of quantity versus quality of life with physicians. Having personal experience with major illness, with the exception of discussing life-sustaining treatment with loved ones, was not associated with being in later stages of change for the different ACP behaviors. Thus, end-of-life experiences with others rather than personal experience with illness or surgery appears to be more strongly associated with increased readiness to participate in ACP activities.

Prior studies have conflicting results regarding the association of personal illness with ACP. Several studies have demonstrated that recent hospitalization and personal health problems influence ACP.13,15 However, similar to the findings of this study, other studies have found a lack of association between health status and/or number of comorbidities and advance directive completion.23,24 The finding that end-of-life care experiences and decision-making for others are associated with more advanced stages of change for most ACP behaviors is in concordance with previous studies which have demonstrated that exposure to end-of-life care issues either through the media14 or through the death of a loved one is associated with increased participation in ACP.13,15 One study found that individuals who had experienced the painful death of a significant other in the past decade were more likely to engage in end-of-life planning.13 The case of Terri Schiavo, with its widespread publicity, gave many individuals “experience” with end-of-life decision-making. The nationally publicized case led to 61% of one study’s participants clarifying their own goals of care and 66% of participants talking to family and friends about ACP.14 The consistent associations across studies between experiences with loved ones or others and readiness to engage in ACP suggests that there is something particularly important about witnessing actual end-of-life care. However, there is a notable difference between the nature of the experiences examined in prior studies as compared to the current study. In prior studies, these experiences were characterized as either witnessing the painful death of a loved one13 or, in the Schiavo case, as witnessing the use of life-sustaining treatment and the prolonged legal battle to have the treatment stopped.14 These studies suggest that individuals are motivated to participate in ACP as a means of limiting medical treatment in order to avoid unwanted interventions at the end of life. In contrast, among our participants, knowing someone who had a bad death due to too little medical care was associated with increased readiness for a greater number of ACP behaviors than knowing someone who received too much medical care. Understanding the reason for this finding requires additional study. It would be important to know whether they were responding to the perception that their loved one died with poorly controlled symptoms such as shortness of breath, anxiety or pain. Alternatively, individuals may have been motivated to outline life-prolonging treatments they would accept for a variety of personal reasons, beliefs or attitudes rather than to use ACP to place limitations on their care.

The findings of this study can help clinicians initiate and advance discussions about ACP and patient preferences. The majority of participants in this study had end-of-life care experiences with others so a strategy that emphasizes these experiences can be employed with many patients; with others, discussing nationally publicized cases or someone they have read about or seen on television could serve as a surrogate experience.1,14 Focusing on end-of-life care experiences to which the patient has had exposure and exploring the patient’s thoughts and feelings on that experience may be more effective than focusing on the patient’s own health status or comorbidities. Given that knowing someone who had a bad death due to too little medical care was associated with increased readiness to complete advance directives and communicate with family, in addition to simply finding out whether a patient has had end-of-life care experiences, it may be equally important to discuss the details of that experience and the patient’s feelings and attitudes toward the care their loved one received. During these discussions, based on previous studies that have explored the stages of change for ACP behaviors, clinicians can assess each patient’s readiness to participate in ACP and recognize that patients may be in varying stages of change for different behaviors.4,10 Another important finding, in congruence with previous studies,25 is the low proportion of participants communicating with physicians despite end-of-life care experiences. Because patients may not be ready to discuss end-of-life preferences with physicians or perhaps may not recognize the importance of communicating their preferences to healthcare providers, physicians may need to take the initiative and time to conduct these essential discussions.

This study has several limitations. First, while the study examined ACP as a group of multiple behaviors, exactly which behaviors should be included in ACP is subject to debate and additional behaviors were not included. Second, experiences with end-of-life care were assessed in a simplified manner. A lack of more in-depth or open-ended questions regarding end-of-life care experiences limits our ability to conclude why certain experiences are associated with increased readiness to participate in ACP. Third, in examining the association between life experiences and stages of change for ACP behaviors, our analysis did not adjust for potential confounding variables. Such an analysis would be challenging, given that we were examining tests for trend. Moreover, if there were variables associated with both past experiences and with readiness to participate in ACP, such as, for example, age, it would be difficult to determine conceptually whether these variables or the past experience were responsible for an individual’s readiness. Additional limitations stem from the population not included in the study. While we achieved good participation rates among the patients in the two primary care practices, there is the potential for non-response bias in our results as we do not have information on patients who did not agree to participate and, in addition, we solicited volunteers at the senior center. Furthermore, while participants were included regardless of their health status, the cohort recruited from primary care practices and senior center may not represent the population at highest risk of decisional incapacity or significant health decline.

The current underutilization of ACP is multifactorial, and identifying factors associated with participation in ACP may help promote these important health behaviors in addition to addressing barriers. Having a serious illness or undergoing major surgery is not associated with advanced stages of change for most ACP behaviors. However, older individuals who have had experience with end-of-life care and decision-making for others demonstrate increased readiness to participate in ACP. Discussions with older patients regarding their previous experiences with loved ones may be a useful tool for clinicians in promoting participation in a variety of ACP behaviors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding: Supported by grants R01 AG19769 and K24 AG28443 from the National Institute on Aging and the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (#P30AG21342 NIH/NIA).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions:

Study concept and design: HA, TRF

Acquisition of subjects and data: TRF

Analysis and interpretation of data: VT, HA, TRF

Preparation of manuscript: HA

Editing of manuscript: TRF

Sponsors’ role: The sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, or analysis and preparation of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann of Intern Med. 2010;153:256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, et al. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1547–1555. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudore RL, Schickedanz AD, Landefeld CS, et al. Engagement in multiple steps of the advance care planning process: a descriptive study of diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1006–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillick MR. Advance care planning. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:7–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath KV, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 170–222. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearlman RA, Cole WG, Patrick DL, et al. Advance care planning: Eliciting patient preferences for life-sustaining treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;26:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00739-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzo VM, Engelhardt J, Tobin D, et al. Use of the stages of change transtheoretical model in end-of-life planning conversations. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:267–271. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reap: Readiness to engage in advance care planning (online) [Accessed October 19, 2013]; Available at: http://www.promotingexcellence.org/mentalillness/3309.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried TR, Redding CA, Robbins ML, et al. Stages of change for the component behaviors of advance care planning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2329–2336. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levi BH, Dellasega C, Whitehead M, et al. What influences individuals to engage in advance care planning? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:306–312. doi: 10.1177/1049909109355280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: Start with patients' self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carr D, Khodyakov D. End-of-life health care planning among young-old adults: An assessment of psychosocial influences. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:S135–S141. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Pantilat SZ, et al. Reach and impact of a mass media event among vulnerable patients: The Terri Schiavo story. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1854–1857. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0733-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr D. "I don't want to die like that …": the impact of significant others' death quality on advance care planning. Gerontologist. 2012;52:770–781. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alano GJ, Pekmezaris R, Tai JY, et al. Factors influencing older adults to complete advance directives. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:267–275. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruff H, Jacobs RJ, Fernandez MI, et al. Factors associated with favorable attitudes toward end-of-life planning. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28:176–182. doi: 10.1177/1049909110382770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Small BJ, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, et al. The course of cognitive impairment in preclinical alzheimer disease: Three- and 6-year follow-up of a population-based sample. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:839–844. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, et al. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon NP, Shade SB. Advance directives are more likely among seniors asked about end-of-life care preferences. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:701–704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freer JP, Eubanks M, Parker B, et al. Advance directives: Ambulatory patients' knowledge and perspectives. Am J Med. 2006;119:1088.e1089. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]