Abstract

Background

The ethanol metabolites, ethyl glucuronide (EtG) and ethyl sulfate (EtS) are biomarkers of recent alcohol consumption that provide objective measures of abstinence. Our goals are to better understand the impact of cutoff concentration on test interpretation, the need for measuring both metabolites, and how best to integrate test results with self-reports in clinical trials.

Methods

Subjects (n=18) were administered, one week apart, 3 alcohol doses calibrated to achieve blood concentrations of 20, 80 and 120 mg/dL respectively. Urinary EtG/EtS were measured at timed intervals during a 24 hour hospitalization and twice daily thereafter. In addition, participants from 2 clinical trials provided samples for EtG/EtS and drinking histories. Cutoffs for EtG/EtS of 100/50, 200/100 and 500/250 ng/mL were evaluated.

Results

Twelve hours following each challenge, EtG was always positive at the 100 and 200 cutoffs, but at 24 hours sensitivity was poor at all cutoffs following the low dose, and poor after 48 hours regardless of dose or cutoff. Similarly, in the clinical trials EtG sensitivity was good for detecting any drinking during the last 24 hours at the two lowest cutoffs, but under 40% during the last 24-48 hours. Sensitivity was reduced at the 500 ng/mL cutoff. Discrepancies between EtG and EtS were few. Comparison of self- reports of abstinence and EtG confirmed abstinence indicated under-reporting of drinking.

Conclusions

Any drinking the night before should be detectable the following morning with EtG cutoffs of 100 or 200 ng/mL. Twenty-four hours after drinking, sensitivity is poor for light drinking, but good for heavier consumption. At 48 hours, sensitivity is low following 6 drinks or less. Increasing the cutoff to 500 ng/mL leads to substantially reduced sensitivity. Monitoring both EtG and EtS should usually be unnecessary. We recommend EtG confirmed self-reports of abstinence for evaluation of outcomes in clinical trials.

Keywords: ethylglucuronide, ethyl sulfate, cutoffs, clinical trials, biomarkers, EtG

INTRODUCTION

Ethyl glucuronide (EtG) and ethyl sulfate (EtS) are minor alcohol metabolites detectable in body fluids following alcohol consumption, and less commonly following extraneous exposure Although other effective biomarkers of ethanol consumption have been validated (Anton, 2010, Lakshman et al., 2001, Litten et al., 2010, Wurst et al., 2005) (SAMHSA, 2012), these 2 are distinguished by their ability to detect recent drinking A detection window that exceeds that of blood alcohol by many hours, and depending upon the amount ingested, even days, has been well documented (Helander and Beck, 2005, Helander et al., 2009, Jatlow and O'Malley, 2010, Kissack et al., 2008, Palmer, 2009, Sarkola et al., 2003, Walsham and Sherwood, 2012, Wurst et al., 2002, Wurst et al., 2003, Wurst et al., 2006). Urine concentrations of these polar metabolites exceed those in blood and saliva (Hoiseth et al., 2007).

Although early experience with these metabolites largely focused on forensic applications, more recently, interest in their use to assess outcomes in clinical trials and treatment programs has increased (Dahl et al., 2011a, Dahl et al., 2011b, Junghanns et al., 2009, Lahmek et al., 2012, Skipper et al., 2004, Wurst et al., 2008) including evaluation of liver transplant patients (Allen et al., 2013, Erim et al., 2007, Staufer et al., 2011, Stewart et al., 2013).

Concerns about false positives consequent to extraneous exposure to ethanol containing products may have impeded wider acceptance of this potentially valuable tool for clinical research and care (Bertholf et al., 2011, Costantino et al., 2006, Hoiseth et al., 2010, Musshoff et al., 2010, Reisfield et al., 2011b, Reisfield et al., 2011a, Rosano and Lin, 2008, SAMHSA, 2006).

A further constraint is the absence of clear guidelines for their interpretation, especially with respect to concentration cutoffs, the concentration of EtG or EtS above which the test is considered positive for alcohol use. This should not be confused with the assay's limit of detection which is generally well below the cutoff, and the limit of quantitation of the assay. Guidance regarding selection of assay cutoffs appropriate for use in clinical programs is needed. Typically, cutoffs for EtG have varied from 100 to 500ng/mL, but higher concentrations have been used to preclude false positives from exposures to non-beverage alcohol (Musshoff et al., 2010) and lower ones recommended to assure confirmation of abstinence. (Albermann et al., 2012) . On the other hand, EtG concentrations as high as 62 and 80 ng/mL have been reported in adults and children respectively who had not been exposed to either beverage or extraneous ethanol (Rosano and Lin, 2008). Unsubstantiated claims have touted EtG/EtS as an 80-hour test.

Evidence supported recommendations are also needed regarding the need to routinely measure both EtG and EtS. Interest in concurrent measurement of EtS has resulted from reports of in-vitro EtG decomposition (Baranowski et al., 2008, Helander and Dahl, 2005) and, conversely, formation of EtG, but not EtS. (Helander et al., 2007). Measuring both metabolites with LC/MS/MS incurs little additional expense. However, recent availability of immunoassays for EtG alone, adds relevance to this question (Böttcher et al., 2008, Turfus et al., 2012).

To address these issues, we conducted a within subject, dose ranging study of oral alcohol administration after which EtG/EtS elimination was followed. We also measured EtG/EtS in 2 clinical trials, 1 focused on abstinence and the other on drinking moderation. Assay results from the clinical trials were compared with self-reports of drinking. The impetus for this study derives from differences in the subject population and consequences of test results between forensic and primarily clinical programs. Our intent is to provide evidence that will allow informed decisions about the use of EtG/EtS measurements in programs focused on clinical research outcomes and to facilitate their interpretation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Alcohol Challenge Study

Subjects

Eighteen subjects, consisting of 10 nonsmokers (5 men and 5 women and 8 smokers (6 men and 2 women) participated in 4 alcohol challenge sessions. Eligible participants consumed alcohol at least once in the past 6 months that would result in an estimated blood alcohol (BAL) above 100mg/dL, but did not meet DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence or other substance use disorders.

Alcohol doses was calibrated to achieve target peak BALs of approximately 20mg/dL (“low”), 80 mg/dL(“medium”) or 120 mg/dL (“high”). Alcohol dosing was calculated using published gender specific algorithms based on estimated body water determined from height, weight and age and translated into mL of 80-proof vodka (Curtin and Fairchild, 2003). Regardless of the amount of vodka required, the amount of mixer was adjusted so that the total volume of fluid was constant.

Four challenge sessions occurred 1 week apart. During the first 3, the doses (low, medium and high) were administered in random order; during the fourth, the medium dose was repeated to assess intra-individual variability. Although most subjects participated during successive weeks, there were occasional skipped weeks due to scheduling needs. We instructed participants to abstain from drinking or use of alcohol containing mouthwash, hand sanitizers or medications during the 5 days preceding the first challenge and between challenges and monitored abstinence with self-report, breath alcohol (BAC) and daily urinary EtG assays. Although 1 subject had minor lapses in abstinence as measured by EtG, her data was considered acceptable and included in this report.

Upon admission, participants received a light standardized breakfast. Beginning at 8:30 am, participants consumed the alcohol dose over 90 minutes in 6 equal portions. BACs were monitored and samples for BAL also obtained at regular intervals until BAC's were negative. Urine samples for analysis of EtG/EtS were collected, volume measured, aliquoted, and stored at -70°C upon admission and at timed intervals during the 24-hour hospitalization. Following the final collection at 10:00AM the next morning, participants were discharged and returned twice per day (evening and morning) over the subsequent 72 hours (following the high dose) or 48 hours (following the low and medium doses) and then daily until the next session to provide spot urine samples for EtG/EtS.

Participants were paid $10 contingently for self-reported abstinence verified by EtG at each appointment (1-2 times per day) prior to and after laboratory sessions, with bonus payments for the week after laboratory sessions ($30-$40). They received $200 for each overnight laboratory session with a $10 bonus for coming to the laboratory on time.

Clinical Trials

Two Placebo Controlled Studies testing the efficacy of mecamylamine (“Abstinence Study”) and naltrexone (“Moderation Study”) on drinking provided additional data for evaluation of EtG/EtS as biomarkers of recent alcohol consumption.

Abstinence Study

Participants were 18-60 years old; alcohol dependent based on DSM-IV criteria; consumed at least 21/14 drinks (men/women) per week, with at least 2 heavy drinking days (>5/4 standard drinks/day for men/women) during a consecutive 30-day period within the 90 days prior to intake. Participants were randomized to receive either mecamylamine or placebo for 12 weeks; abstinence from alcohol was the goal.

Moderation Study

Subjects were18-25 years old and met criteria for hazardous drinking (>5/4 standard drinks/day for men/women) on ≥ 4 days in the prior 4 weeks. Participants were randomized to receive either naltrexone or placebo for 8 weeks; moderation of alcohol intake was the goal.

In both studies, the TimeLine Follow-Back Interview (Sobell and Sobell, 1995) was used to obtain daily reports of drinking quantity at baseline and during treatment. A urine sample was obtained at baseline for EtG/EtS analysis and monthly thereafter during treatment. This report focuses on baseline and week 4 data, which had more observations than later time-points.

Assays

EtG and EtS were measured using High Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry with deuterated internal standards, as adapted from published procedures (Weinmann et al., 2004). Primary calibration standards and multiple controls, all prepared in urine, were carried through the entire procedure. Deuterated EtG and EtS and unlabeled EtG were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto, Ont. and unlabeled EtS from Athena ES, Baltimore, MD. The following ion transitions were monitored: EtG: Quantifier 221 →75; Qualifier 221 →85; EtG-D5 (internal standard) 226 →75: EtS: Quantifier 125 →97; Qualifier 125 →80; EtS-D5 (internal standard) 130 →98. The CVs in routine use ranged from 1.5% to 8.2%for EtG and 1.8% to 7.4% for EtS over the analytical range of the standard curve. The higher CVs refer to the lower limits of quantitation, which were 100 ng/mL and 50 ng/mL for EtG and EtS respectively. Although the highest standard was10,000 ng/mL, the procedure was linear to a least 200,000 ng/ml.

Plasma alcohols were measured by head-space gas chromatography. Urine creatinine concentrations were measured by a modified Jaffe reaction.

Data Analysis

Total metabolite excretion during each timed collection interval during the 24-hour inpatient phase was determined from the product of the urine volume and concentration, and used to determine the rate of metabolite elimination during each interval. Half-lives were estimated from the terminal slope (beginning 6 or more hours after completion of drinking) of a plot of log elimination rate vs. the midpoint of each timed collection interval. Since concentrations of ethanol were undetectable at the initial time point used for the calculation, it was assumed that the slope reflected metabolite rather than alcohol elimination. The total amounts eliminated during each time interval were summed and used to calculate the fraction of the alcohol dose eliminated as EtG or EtS during the 24-hour inpatient collection period. Based upon reported half-lives of EtG and EtS which were consistent with our own findings, over 99% of the 2 metabolites would have been excreted during the 24 hr hospitalization. However, the high sensitivity of the LC/MS/MS assay allows their measurement for considerably longer.

Repeated measures mixed models were used to compare urinary elimination parameters across low, medium and high ethanol doses for EtG and EtS. The mixed models contained fixed effects for dose, gender and smoking and an unstructured covariance matrix to accommodate the dependence of observations from repeated assessments. Two-way interactions of dose with gender and smoking were evaluated and excluded if p<0.10. Comparisons of percent positive (i.e. sensitivity) using the different cutoffs for positivity (i.e., 100, 200 or 500 for EtG and 50, 100 or 250 mg/dL for EtS) were made by logistic regression with estimation by Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE). These models included fixed effects for cutoff, gender and smoking. Correlation of repeated assessments was accommodated using an exchangeable working correlation. Linear contrasts were used for pairwise comparisons. All comparisons were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (Cary, NC) and evaluated at the 2-sided 0.05 significance level. Reliability of repeat measures of selected EtG parameters at the medium dose was assessed through estimation of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Clinical Trials

Discrepancies between EtG and EtS were compared across all samples (N=120) at their corresponding cut-offs (i.e., EtG/EtS: 100/50, 200/100, 500/250). The sensitivity of EtG for detecting self-reported drinking (>0 drinks) that occurred within 24 hours, 24-48 hours and 48-72 hours prior to the urine collection was estimated for the different EtG cut-offs (100, 200, 500) using data pooled across the 2 studies. We also explored EtG sensitivity for self-reported drinking at these same time points using the 100ng/mL cut-off for the 2 studies separately. In order to evaluate the effect of requiring EtG confirmation of self-reported abstinence, we classified participants according to whether they had abstained from alcohol for the prior 48 hours based on their self-report and based on a negative EtG using the 100mg/dL cut-off. We then estimated the proportion abstinent by self-report alone and the proportion abstinent by self-report confirmed by a negative EtG by study and pooled across studies at baseline and at week 4 of treatment.

RESULTS

Alcohol Challenge Study

Patient Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Alcohol Challenge Study Participants.

| Overall Sample (n = 18) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Measure | Overall | Range |

| Age, Mean(SD) | 33.1(12.90) | 21-60 |

| Race | ||

| White, N (%) | 11(61.1) | |

| Black, N (%) | 4(22.2) | |

| Other, N (%) | 3(16.7) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male, N (%) | 11(61.1) | |

| Weight in lbs, Mean(SD) | 178.7(39.72) | 122-239 |

| Baseline alcohol consumption | ||

| Percent days drinking, Mean(SD) | 24.9(17.88) | 3.33-62.22 |

| Standard drinks per drinking day, Mean(SD) | 4.5(2.02) | 1.57-8.33 |

| Peak standard drinks on a day, Mean(SD) | 8.9(4.26) | 4-17 |

| Baseline smoking characteristics (n = 8) | ||

| Cigarettes per day, Mean(SD) | 15.3(5.61) | 7.5-20.88 |

| CO, Mean(SD) | 16.9(4.85) | 10.0-24.0 |

Smokers who met the inclusion criteria for drinking history, especially women, were difficult to recruit. Thus, while the 10 non-smokers show a gender balance, the smokers were predominately men. One subject vomited after the high dose invalidating that challenge. Other subjects tolerated all doses well.

Blood (plasma) alcohol concentrations

The calculated alcohol dosages resulted in concentrations that exceeded their targets by 16% for the medium and high doses and by 42% for the lowest (Table 2).

Table 2.

Alcohol Dose Parameters.

| Variable | Alcohol Dose Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 18) | Medium (n = 18) | High (n = 17)a | |

| Target BAL (mg/100 mL), Mean, SD | 20 | 80 | 120 |

| Alcohol dose (gms), Mean, SD | 26.3(5.91) | 57.8(13.01) | 78.8(17.74) |

| 80% Vodka Dose (mL), Mean, SD | 83.4(18.77) | 183.4(41.32) | 250.1(56.32) |

| Peak BAL (mg/100mL), Mean, SD | 28.3(8.85) | 93.1(20.74) | 138.8(27.62) |

BAL = Blood alcohol level

One participant vomited and was not included in the analysis

EtG/EtS urinary elimination kinetics (Table 3)

Table 3.

EtG and EtS Urinary Elimination Parameters

| Alcohol Dose Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite | Measures | Low (n=18) | Medium (n=18) | High (n=17) | P-valuesa |

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | |||

| EtG | Cmax (ng/mL) | 11221 (8194) | 89784 (94784) | 200483 (103715) | <.0001 |

| C(24hr) (ng/mL) | 167.5 (221.0) | 1310 (1499) | 2567 (3254) | 0.01 | |

| Cmax (hrs) | 4.8 (1.72) | 5.7 (1.82) | 6.7 (1.20) | 0.006 | |

| Last positive 100 ng/mL cutoff (hrs) | 22.2 (5.61) | 32.3 (9.69) | 37.1 (12.03) | <.0001 | |

| Last positive 200 ng/mL cutoff (hrs) | 18.9 (4.30) | 28.2 (8.17) | 30.5 (10.55) | <.0001 | |

| Last positive 500 ng/mL cutoff(hrs) | 12.3 (4.67) | 22.9 (3.30) | 26.5 (6.89) | <.0001 | |

| Half life (minutes) | 152.1 (47.91) | 156.7 (35.44) | 160.2 (31.86) | 0.66 | |

| % alcohol dose as EtG | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.03) | <.0001 | |

| EtS | Cmax (ng/mL) | 3331 (2645) | 23618 (16211) | 52615 (21959) | <.0001 |

| C(24hr) (ng/mL) | 27.8 (48.47) | 396.6 (412.70) | 686.8 (828.87) | 0.06 | |

| Cmax (hrs) | 3.7 (1.42) | 5.0 (1.00) | 6.1 (1.27) | <.0001 | |

| Last positive 100 ng/mL cutoff (hrs) | 17.6 (5.31) | 32.4 (11.53) | 34 (10.04) | <.0001 | |

| Last positive 200 ng/mL cutoff (hrs) | 13.6 (5.93) | 29.0 (10.15) | 32.6 (9.59) | <.0001 | |

| Last positive 500ng/mL cutoff (hrs) | 9.8 (3.82) | 20.8 (4.91) | 26.6(7.39) | <.0001 | |

| Half life (minutes) | 170.4(32.51) | 177.4(30.52) | 173.5(23.43) | 0.73 | |

| % alcohol dose as EtS | 0.01(0.00) | 0.03(0.01) | 0.04(0.01) | <.0001 | |

| Ratio | EtS/EtG at 12 hours | 0.2(0.14) | 0.2(0.15) | 0.2(0.12) | 0.81 |

EtG = Ethyl Glucuronide; EtG = Ethyl Sulfate

Mean dose, grams (sd): low dose = 26.3(5.91), medium dose =57.8(13.01), high dose = 78.8(17.74)

P-values are the test of dose covarying for gender and smoking status

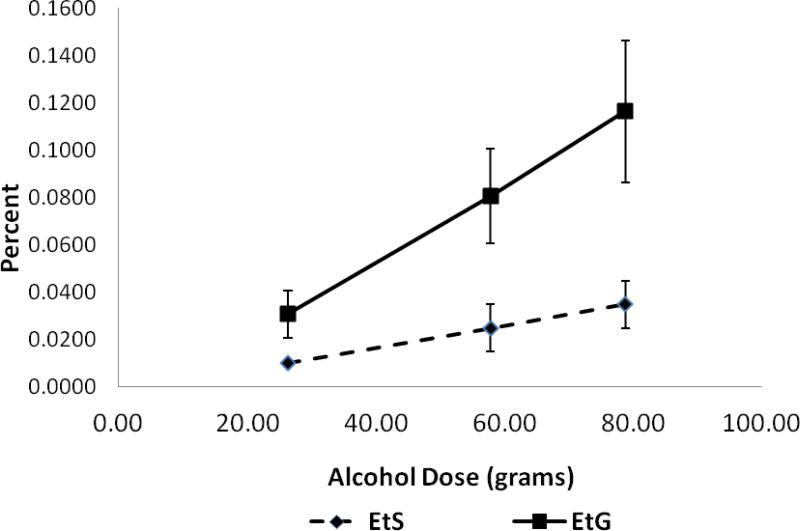

Cmax showed a disproportionate increase with alcohol dose. Mean T1/2s for EtG and EtS were 156 and 174 minutes respectively and did not vary significantly across dose. The percentage of the alcohol dose eliminated as urinary EtG and EtS increased with dose (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Fig.1.

Percent of alcohol dose eliminated as urinary EtG and EtS during 24 hr. period following alcohol administration. Data presented are means (with SD's) for each of three doses (n =18 for the low and medium doses and n = 17 for the high dose). Alcohol doses in grams (mean +/- SD): Low (26.3+/-5.91); Medium (57.8 +/-13.01); and High (78.8+/-17.74). The slopes of the lines would be 0 if percent of alcohol dose converted to EtG/EtS were not dose dependent.

EtG/EtS: Detection Window

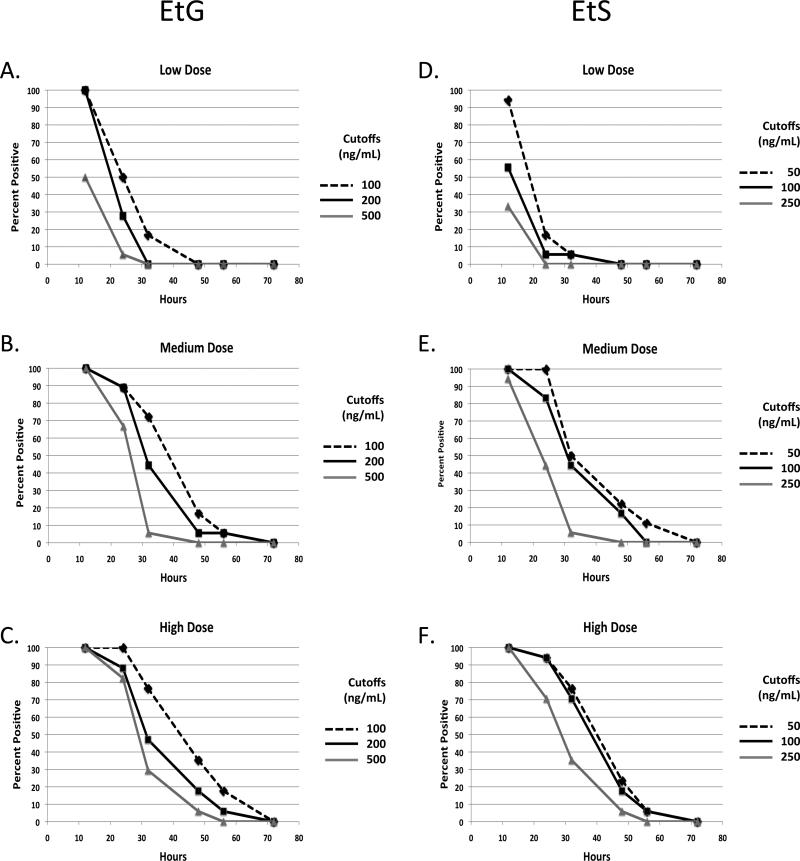

Figure 2 shows the time interval over which urinary EtG (Figure 2a-c) and EtS (Figure 2d-f) remained positive (i.e. sensitivity) at each alcohol dose and cutoff. Sensitivity increased with dose (p<0.001), decreased with increasing cut-off concentration (p<0.001) and time elapsed since completion of drinking (p<0.001). At 12 hours following conclusion of drinking, the urinary EtG cutoffs of 100 ng/mL and 200 ng/mL were exceeded in 100% of participants at all doses. The 500 ng/mL cutoff was exceeded by 100% of participants in the medium (18/18) and high doses (17/17) but in only 50% (9/18) of participants at the low dose. Average concentrations of EtG were 907.2ng/mL (sd = 705.74), 11991.4ng/mL (sd = 16496.19) and 19265.3 (sd = 17074.53) ng/mL at 12 hours following the low, medium and high alcohol doses respectively. Twenty-four hours following the medium and high doses, the EtG detection rate was over 80% for each cutoff with the exception of the medium dose at the 500ng/mL cutoff. On the other hand, the highest cutoff identified light (low dose) drinking at 24 hrs in only a single subject. EtS assay results (Figure 2d-f) generally tracked those of EtG (Figure 2a-c). Forty-eight hours following the low dose, EtG and EtS were each negative at all cut-offs and the detection rate was less than 40% for the medium and high doses.

Fig.2.

Percent of tests positive for EtG or EtS at various times after oral administration of low medium and high oral doses of alcohol using each of three cutoff concentrations (EtG/EtS: 100/50, 200/100, 500/250). a. EtG low dose, b. EtG, moderate dose, c. EtG, high dose, d. EtS, low dose, e. EtS, moderate dose, and f. EtS, high dose. Alcohol doses in grams (mean +/- SD): Low (26.3+/-5.91); Medium (57.8 +/-13.01) High (78.8+/-17.74). n = 18 for the low and moderate doses and 17 for the high dose.

EtG normalization for creatinine concentration

Urine creatinine measurements were performed to determine if urine dilution might have resulted in false negatives in the challenge study. In order to accomplish this objective, we analyzed samples that were initially defined as negative (below our lowest cutoff of 100 ng/mL) but which otherwise met mass spectrometry criteria for identification of EtG. We restricted our evaluation to the first negative sample following the last positive when EtG might still be present but below the cutoff. As urinary creatinine concentrations are, on average, approximately 1 mg/mL, we selected a normalized value of 100 ng EtG/mg Cr as comparable to the lowest cut-off.

Sixty-seven sample pairs were tested. Creatinine concentrations ranged from very dilute (7.8 mg/dL) to moderately concentrated (258 mg/dL). Only a single weakly EtG positive sample fell below 100 ng EtG/mg Cr following normalization. Of the 67 originally negative samples (EtG not detectable or below the cut off), 28% (19) exceeded 100 ng EtG/mg Cr after normalization.

Reliability of Repeat Measurements

EtG concentrations at 24 hours following repeated challenges with the medium dose (N=17) showed poor intra-subject repeatability with an intra-subject variance that actually exceeded the inter-subject variance (ICC 0.28). On the other hand, the percent of the alcohol dose eliminated as EtG showed much better repeatability (ICC 0.60).

CLINICAL TRIALS

Patient Demographics

Table 4 presents subject characteristics of the Moderation and Abstinence Study participants who provided samples for measurement of EtG/EtS. Moderation Study participants were younger, less likely to be smokers, and drank less than the abstinence sample.

Table 4.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants in the Clinical Studies

| Measure | Moderation Study (n=83) | Abstinence Study (n=47) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean(SD) | 21.6(2.21) | 48.0(10.36) |

| Race | ||

| White, N(%) | 63(75.9) | 24(51.1) |

| Black, N(%) | 8(9.6) | 14(29.8) |

| Hispanic, N(%) | 5(6.0) | 5(10.6) |

| Other/unknown, N(%) | 7(8.4) | 4(8.5) |

| Gender | ||

| Male, N(%) | 63(75.9) | 42(89.4) |

| Baseline alcohol consumption | ||

| Percent days drinking, Mean(SD) | 53.0(18.84) | 79.6(22.20) |

| Standard drinks per drinking day, Mean(SD) | 6.4(2.47) | 12.4(7.79) |

| Standard rinks per day over 30 days, Mean(SD) | 3.2(1.43) | 10.1(7.75) |

| Peak standard drinks on a day, Mean(SD) | 12.7(4.81) | 20.0(11.48) |

| Baseline smoking characteristics | ||

| Smoker, n (%) | 32(38.55) | 29(61.7) |

| Cigarettes per smoking day, Mean(SD) | 4.3(2.94) | 11.6(7.68) |

| Cigarettes per day over 30 days, Mean(SD) | 2.7(3.22) | 11.4(7.84) |

Comparison of EtG and EtS

The average ratios of EtS/EtG were 0.47 (SD=0.32) and 0.52 (SD=0.52) in the moderation and abstinence trials respectively which reflects the ratio in the selected cutoffs. Discrepancies between outcomes by the 2 metabolite measurements in the baseline sample were few. The percentage of samples with a negative EtG (<100 ng/Ml) but positive EtS (> 50ng/mL) was 6% and fell slightly to 3 and 4% respectively at the 2 higher cutoffs.

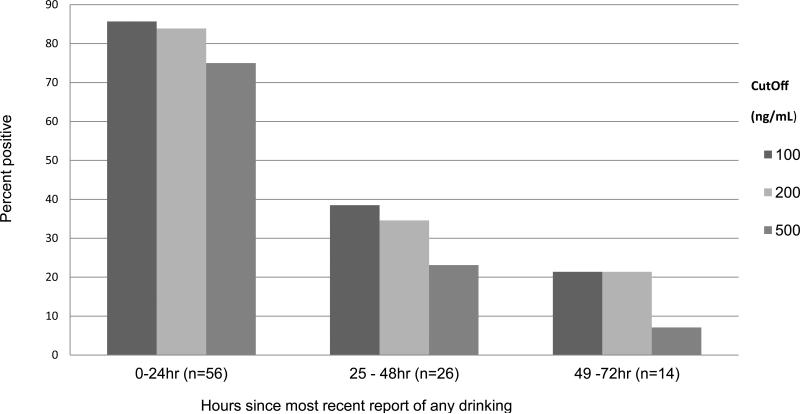

Using the pooled baseline data from both trials, Figure 3 shows the sensitivity of EtG at each of the 3 cutoffs for detecting any drinking following various time intervals. Over 80% of those who reported drinking within the previous 24 hrs were identified using the 100 and 200 ng/mL cutoffs, but only 75% were identified at the highest cutoff. The detection rate fell below 40% for those who reported drinking within the prior 25-48 and to 21% or less at 49-72 hours for all 3 cutoffs.

Fig.3.

Sensitivity of urinary EtG for detection of drinking as a function of cut off and time since drinking: Graph shows percent positive for EtG using each of three cut-offs (100, 200 and 500mg/dL) for those who acknowledged their last drinking episode within <24 hours (n = 56), 25 – 48 hours (n = 26), and 49 to72 hours (n = 14) prior to the baseline EtG sample. The figure represents the pooled baseline data from the 2 clinical trials.

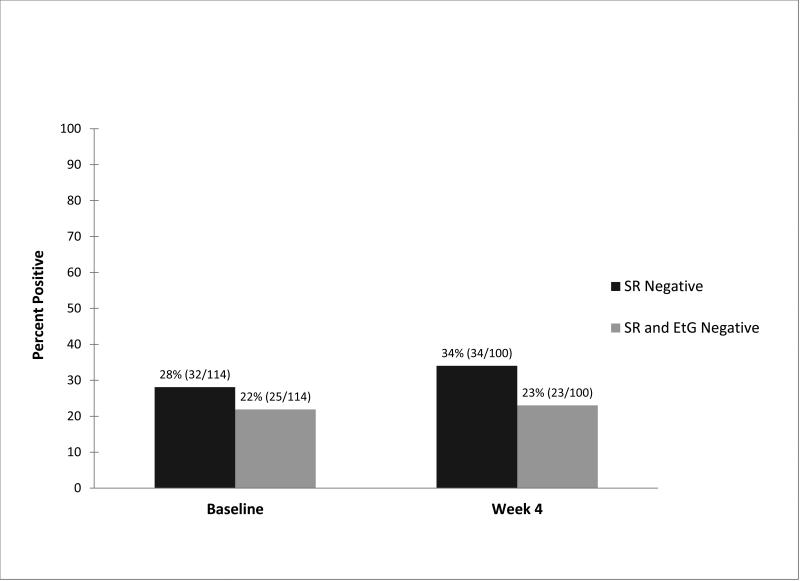

Self-Report Only vs. Assay Plus Self Report on Abstinence Evaluation

Figure 4 shows the percentage of clinical trial participants who self-reported abstinence and the percent with both negative self-reports and EtG assays using a 100 ng/mL cutoff, at baseline and 4 weeks, for the pooled data.. At baseline, 28% (32/114) reported abstinence and 22.3% were abstinent by self-report + EtG. At week 4, the corresponding percentages were 34% for self-report alone (34/100) and 23% (23/100) for self-report + negative EtG.. A similar discrepancy between self-reported and EtG confirmed abstinence was observed in each to the two clinical trials.

Fig.4.

Urinary EtG confirmation of self- reports of abstinence. Graph shows percentage of clinical trial participants who self-reported abstinence during prior 48 hours (SR negative) and who were also confirmed as negative by EtG assay (SR and EtG negative), at baseline (n = 114) and after four weeks of treatment (n = 100). EtG results were based on a 100 ng/mL cutoff.

DISCUSSION

Cutoffs

Statements that EtG will detect drinking for a defined period are of limited validity unless considered in the context of the cutoff concentration above which a test is defined as positive. With this report, we have attempted to define the effect of cutoff selection on test outcome in conjunction with alcohol dosage and interval following drinking. In the challenge study, EtG was invariably and EtS usually positive 12 hours following a drinking challenge using cutoffs off of 100/50 and 200/100ng/mL. This was true even following the low dose, which corresponded to about 2 standard (30 mL drinks) consumed over 90 minutes. Sensitivity fell to 50% for the low dose with the 500 ng/mL EtG cut-off. Thus, using the 2 lower cut-offs, drinking of almost any amount beyond a single drink the night before would be detected in a sample obtained the following morning.

On the other hand, 24 hours following the low dose, sensitivity was poor falling to 50% or less at the 2 lower cutoffs and to near 0 (5.6%) with the 500 ng/mL cutoff. After a 48 hour interval, consumption of the low dose was undetectable at all cut-offs. After a 24 hr interval, the 2 lower cut-offs identified over 80 percent of samples following the medium and high doses, but less than 40% at 48 hours regardless of cut-off. EtG testing results in the clinical trials mirrored that of the challenge studies. Raising the EtG cutoff from 100 to 200ng/mL had only a small effect on sensitivity in the clinical trials. Greater than 80% of those who self-reported drinking during the last 24 hours were detected with the two lower cut offs, but sensitivity was much lower following a longer interval. Overall, sensitivity appeared to be greater than observed in the challenge study probably because alcohol consumption by individuals with alcohol use disorders is often considerably greater than was feasible in the challenge study.

At the cost of a small decrement in sensitivity, a small increase in cut-off from 100 to 200 ng/mL may have the advantage of reducing assay variability for concentrations at or around the cut-off (Helander et al., 2010) and perhaps reducing risk of interference from extraneous exposures. Increasing the EtG cut-off to 500 ng/mL reduces sensitivity for detection of drinking more substantially. Based on concerns about incidental exposures to ethanol, a 500 ng/mL cut-off.has been recommended as a practical cut-off for a commercially available immunoassay (Böttcher et al., 2008). In the context of the ability to obtain preliminary results in real time during clinic visits, the reduction in sensitivity may be an acceptable tradeoff for clinical treatment programs, but could lead to an overestimation of efficacy in a treatment trial. This issue may be different for forensic applications for which the reliability of self-reports and the consequences of positive test results may be different. Further experience with the immunoassay may document a lower limit of quantitation

Since our data indicate that drinking history was under-reported by many participants, even in the absence of consequences, there was no valid way to estimate drinking prevalence, true or false negatives and thus to calculate negative predictive values or to evaluate ROC's.

Accurate Evaluation of Treatment Outcome of Abstinence

Reliance on self-reports alone resulted in over-estimation of abstinence compared to self-reports confirmed by negative EtG assay. A higher cut-off might reduce the discrepancy between self-reports and assay results, but the over estimation of true abstinence would be greater. Regardless, reliance on self-reports alone risks an over estimation of treatment efficacy. Alternatively, reliance on EtG assays alone should also result in overestimation of abstinence since the assays of self-reported drinkers shows a percentage of false negatives depending on the time and amount of the last drinking episode. Thus, requiring a negative self-report paired with a negative EtG assay should provide a better, although not perfect, estimate of drinking abstinence.

Is EtS necessary?

Comparisons of the performance of EtS and EtG are constrained by their dependence on relative assay sensitivity including lower limits of quantitation, selected cutoffs and the considerable inter-individual variation in EtS/EtG ratios. The average ratio of EtS/EtG in the assay positive samples in the 2 clinical studies was consistent with the relative mean concentrations of EtG and EtS selected for the 3 levels of cutoff, and discrepancies between the 2 were uncommon. Thus, there is limited evidence to recommend measuring both metabolites, and the need for a policy for addressing the occasional discrepancy between the two. Moreover, the currently available immunoassay only measures EtG (Böttcher et al., 2008). Potential errors resulting from in vitro loss or production of EtG have been reported (Baranowski et al., 2008, Helander and Dahl, 2005), but, as far as we know, have not been documented as a problem in routine use. Theoretically, genetic polymorphisms in UGT 1A1 might alter the formation of EtG.

Impact of Extraneous Alcohol Exposures

The interpretation of most clinical laboratory tests requires knowledge of possible exogenous or endogenous interferences. EtG/EtS testing is no exception. In our study, the concentrations of EtG and EtS observed at 12 hrs post consumption were, with the exception of some anecdotal reports much higher than those reported with even strong extraneous exposure (e.g., hand sanitizers), wherein concentrations rarely exceed usual cut-offs (Bertholf et al., 2011, Costantino et al., 2006, Hoiseth et al., 2010, Musshoff et al., 2010, Reisfield et al., 2011b, Reisfield et al., 2011a). Some healthcare workers, who are exposed to alcohol containing hand washes repeatedly throughout the day, might be positive if tested shortly thereafter, which could be addressed by allowing a 12 hr or greater interval before testing. Otherwise, it might be prudent to ask individuals to restrict such exposures (e.g. ask participants to wash with soap and water and/or not use hand sanitizers for 12 hours). This option, available to clinical programs, is analogous to requesting individuals to fast prior to blood glucose testing. Using a cut-off of 200ng/mL for EtG might further reduce the small risk of such “false positives”, while raising it to 500ng/mL, would entail reduced sensitivity especially for detection of light to moderate drinking.

Pharmacokinetics

The explanation for the increase in the fraction of the alcohol dose eliminated as the 2 metabolites with an increase in alcohol dose is likely due to saturation of the major pathway for elimination of alcohol resulting in an increasing proportion of parent drug available to conjugation pathways. The persistence of EtG and EtS in body fluids has sometimes been attributed to long half lives of the metabolites. Actually the half-lives estimated here, which are consistent with other reports, (Droenner et al., 2002, Hoiseth et al., 2007, Schmitt et al., 2010) are short. The relatively long detection times following alcohol consumption reflects the high sensitivity of available assays. In this study, neither metabolite was detectable much beyond 48 hours after drinking regardless of dose. Exceptions might be patients undergoing detoxification (Helander et al., 2009, Hoiseth et al., 2009) or following very heavy drinking in excess of the 6-7 drinks equivalent maximum employed in our challenge study, especially with greater proportionate diversion of the alcohol into conjugation pathways, Nevertheless, definition of the EtG assay as an “80 hour test” for alcohol consumption was not substantiated by this study.

Reliability of Repeat Measurements

Following re-challenge with the medium alcohol dose, EtG concentrations did not show sufficient intra-subject repeatability to suggest that concentrations following recurrent testing of the same individual might be a reliable indicator of time and amount of alcohol consumed. This probably, at least in part, reflects variation in urine dilution between samples.

Normalization for Creatinine Concentration

False negatives consequent to urine dilution is a recognized concern with drug abuse testing. Others have noted that correction of EtG concentrations for urine dilution through normalization for creatinine content may provide a more valid estimate of EtG excretion. (Bergstrom et al., 2003, Dahl et al., 2002, Goll et al., 2002). However, the LLOQ constrains the use of creatinine corrections, and largely limits them to identification of unusually dilute samples. In the challenge study, normalization for urine creatinine concentration of the first EtG negative sample following a positive would have elevated 28% of results originally below the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) into a “positive” range, an approximation only because of the greater assay variability below the LLOQ. Although routine correction for urine dilution would undoubtedly identify some false negatives, the yield would likely be very much lower in clinical practice than was observed in the challenge study, because all subjects had consumed alcohol, and we evaluated the first negative sample following the last positive at which time EtG might still be present but below the cutoff.

Conclusions

In summary, cutoffs are important. While the detection window varies with the amount of alcohol consumed, increasing cut-off concentrations for EtG from 100 to 500 ng/mL results in a significant loss of sensitivity. EtG cannot justifiably be defined as an “80 hour” test. Detection of even light drinking is excellent after an interval of 12 hours, but beyond that, sensitivity depends upon the amount consumed. Negative EtG associated with positive EtS results are sufficiently uncommon that assay of EtG alone should be acceptable for clinical treatment and clinical research programs. Reliance on either self-reports or assay results alone may result in significant overestimation of abstinence in clinical trials. In summary, we recommend confirming self-reports of abstinence from alcohol with EtG assay data for evaluating outcomes in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Support for this study was provided by the following grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism RO1AA018665, R01AA016621, RO1AA016834, KO5AA014715, and P50-AA-12870; CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024139, and from the State of Connecticut, Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

REFERENCES

- Albermann ME, Musshoff F, Doberentz E, Heese P, Banger M, Madea B. Preliminary investigations on ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate cutoffs for detecting alcohol consumption on the basis of an ingestion experiment and on data from withdrawal treatment. Int J Legal Med. 2012;126:757–764. doi: 10.1007/s00414-012-0725-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Wurst FM, Thon N, Litten RZ. Assessing the drinking status of liver transplant patients with alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:369–376. doi: 10.1002/lt.23596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF. Editorial commentary: alcohol biomarker papers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:939–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski S, Serr A, Thierauf A, Weinmann W, Perdekamp MG, Wurst FM, Halter CC. In vitro study of bacterial degradation of ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulphate. Int J Legal Med. 2008;122:389–393. doi: 10.1007/s00414-008-0229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom J, Helander A, Jones AW. Ethyl glucuronide concentrations in two successive urinary voids from drinking drivers: relationship to creatinine content and blood and urine ethanol concentrations. Forensic Sci Int. 2003;133:86–94. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(03)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholf RL, Bertholf AL, Reisfield GM, Goldberger BA. Respiratory Exposure to Ethanol Vapor During Use of Hand Sanitizers: Is It Significant? J Anal Toxicol. 2011;35:319–320. doi: 10.1093/anatox/35.5.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher M, Beck O, Helander A. Evaluation of a new immunoassay for urinary ethyl glucuronide testing. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2008;43:46–48. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino A, DiGregorio EJ, Korn W, Spayd S, Rieders F. The effect of the use of mouthwash on ethylglucuronide concentrations in urine. J Anal Toxicol. 2006;30:659–662. doi: 10.1093/jat/30.9.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JJ, Fairchild BA. Alcohol and cognitive control: Implications for regulation of behavior during response conflict. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:424–436. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl H, Hammarberg A, Franck J, Helander A. Urinary ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate testing for recent drinking in alcohol-dependent outpatients treated with acamprosate or placebo. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011a;46:553–557. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl H, Stephanson N, Beck O, Helander A. Comparison of urinary excretion characteristics of ethanol and ethyl glucuronide. J Anal Toxicol. 2002;26:201–204. doi: 10.1093/jat/26.4.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl H, Voltaire Carlsson A, Hillgren K, Helander A. Urinary ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate testing for detection of recent drinking in an outpatient treatment program for alcohol and drug dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011b;46:278–282. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droenner P, Schmitt G, Aderjan R, Zimmer H. A kinetic model describing the pharmacokinetics of ethyl glucuronide in humans. Forensic Sci Int. 2002;126:24–29. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(02)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erim Y, Bottcher M, Dahmen U, Beck O, Broelsch CE, Helander A. Urinary ethyl glucuronide testing detects alcohol consumption in alcoholic liver disease patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:757–761. doi: 10.1002/lt.21163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll M, Schmitt G, Ganssmann B, Aderjan RE. Excretion profiles of ethyl glucuronide in human urine after internal dilution. J Anal Toxicol. 2002;26:262–266. doi: 10.1093/jat/26.5.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander A, Beck O. Ethyl sulfate: A metabolite of ethanol in humans and a potential biomarker of acute alcohol intake. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29:270–274. doi: 10.1093/jat/29.5.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander A, Bottcher M, Fehr C, Dahmen N, Beck O. Detection times for urinary ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate in heavy drinkers during alcohol detoxification. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2009;44:55–61. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander A, Dahl H. Urinary tract infection: A risk factor for false-negative urinary ethyl glucuronide but not ethyl sulfate in the detection of recent alcohol consumption. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1728–1730. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander A, Kenan N, Beck O. Comparison of analytical approaches for liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry determination of the alcohol biomarker ethyl glucuronide in urine. Rapid Commun Mass Sp. 2010;24:1737–1743. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander A, Olsson I, Dahl H. Postcollection synthesis of ethyl glucuronide by bacteria in urine may cause false identification of alcohol consumption. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1855–1857. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.089482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiseth G, Bernard JP, Karinen R, Johnsen L, Helander A, Christophersen AS, Morland J. A pharmacokinetic study of ethyl glucuronide in blood and urine: Applications to forensic toxicology. Forensic Sci Int. 2007;172:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiseth G, Morini L, Polettini A, Christophersen A, Morland J. Blood kinetics of ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulphate in heavy drinkers during alcohol detoxification. Forensic Sci Int. 2009;188:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiseth G, Yttredal B, Karinen R, Gjerde H, Christophersen A. Levels of Ethyl Glucuronide and Ethyl Sulfate in Oral Fluid, Blood, and Urine After Use of Mouthwash and Ingestion of Nonalcoholic Wine. J Anal Toxicol. 2010;34:84–88. doi: 10.1093/jat/34.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatlow P, O'Malley SS. Clinical (nonforensic) application of ethyl glucuronide measurement: are we ready? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:968–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junghanns K, Graf I, Pfluger J, Wetterling G, Ziems C, Ehrenthal D, Zollner M, Dibbelt L, Backhaus J, Weinmann W, Wurst FM. Urinary ethyl glucuronide (EtG) and ethyl sulphate (EtS) assessment: valuable tools to improve verification of abstention in alcohol-dependent patients during in-patient treatment and at follow-ups. Addiction. 2009;104:921–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissack JC, Bishop J, Roper AL. Ethylglucuronide as a biomarker for ethanol detection. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:769–781. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahmek P, Michel L, Divine C, Meunier N, Pham B, Cassereau C, Aussel C, Aubin HJ. Ethyl glucuronide for detecting alcohol lapses in patients with an alcohol use disorder. J Addict Med. 2012;6:35–38. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182249b93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshman R, Tsutsumi M, Ghosh P, Takase S, Anni H, Nikolaeva O, Israel Y, Anton RF, Lesch OM, Helender A, Eriksson G, Jeppson JO, Marmillot P, Rao MN. Alcohol biomarkers: Clinical significance and biochemical basis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:67S–70S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Bradley AM, Moss HB. Alcohol biomarkers in applied settings: recent advances and future research opportunities. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:955–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musshoff F, Albermann E, Madea B. Ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate in urine after consumption of various beverages and foods-misleading results? Int J Legal Med. 2010;124:623–630. doi: 10.1007/s00414-010-0511-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RB. A review of the use of ethyl glucuronide as a marker for ethanol consumption in forensic and clinical medicine. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2009;26:18–27. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisfield GM, Goldberger BA, Crews BO, Pesce AJ, Wilson GR, Teitelbaum SA, Bertholf RL. Ethyl glucuronide, ethyl sulfate, and ethanol in urine after sustained exposure to an ethanol-based hand sanitizer. J Anal Toxicol. 2011a;35:85–91. doi: 10.1093/anatox/35.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisfield GM, Goldberger BA, Pesce AJ, Crews BO, Wilson GR, Teitelbaum SA, Bertholf RL. Ethyl glucuronide, ethyl sulfate, and ethanol in urine after intensive exposure to high ethanol content mouthwash. J Anal Toxicol. 2011b;35:264–268. doi: 10.1093/anatox/35.5.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosano TG, Lin L. Ethyl glucuronide excretion in humans following oral administration of and dermal exposure to ethanol. J Anal Toxicol. 2008;32:594–600. doi: 10.1093/jat/32.8.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA The role of biomarkers in the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Subst Abuse Treatment Advisory. 2006;5:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA The role of biomarkers in the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Subst Abuse Treatment Advisory. 20122012 Revision 11:1-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkola T, Dahl H, Eriksson CJ, Helander A. Urinary ethyl glucuronide and 5-hydroxytryptophol levels during repeated ethanol ingestion in healthy human subjects. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:347–351. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt G, Halter CC, Aderjan R, Auwaerter V, Weinmann W. Computer assisted modeling of ethyl sulfate pharmacokinetics. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;194:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper GE, Weinmann W, Thierauf A, Schaefer P, Wiesbeck G, Allen JP, Miller M, Wurst FM. Ethyl glucuronide: A biomarker to identify alcohol use by health professionals recovering from substance use disorders. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2004;39:445–449. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol consumption measures, in Assessing alcohol problems: A guide for clinicians and researchers. In: JAV WILSON, editor. Assessing alcohol problems: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Second Edition. Second Edition Vol. 4. NIAAA; Bethesda, MD: 1995. pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Staufer K, Andresen H, Vettorazzi E, Tobias N, Nashan B, Sterneck M. Urinary ethyl glucuronide as a novel screening tool in patients pre- and post-liver transplantation improves detection of alcohol consumption. Hepatol. 2011;54:1640–1649. doi: 10.1002/hep.24596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Koch DG, Burgess DM, Willner IR, Reuben A. Sensitivity and specificity of urinary ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate in liver disease patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01855.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turfus SC, Vo T, Niehaus N, Gerostamoulos D, Beyer J. An evaluation of the DRI-ETG EIA method for the determination of ethyl glucuronide concentrations in clinical and post-mortem urine. Drug testing and analysis. 2012 doi: 10.1002/dta.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsham NE, Sherwood RA. Ethyl glucuronide. Annals of clinical biochemistry. 2012;49:110–117. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinmann W, Schaefer P, Thierauf A, Schreiber A, Wurst FM. Confirmatory analysis of ethylglucuronide in urine by liquid-chromatography/electrospray ionization/tandem mass spectrometry according to forensic guidelines. Journal of the Amer Soc Mass Spectrometry. 2004;15:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurst FM, Alling C, Araclottir S, Pragst F, Allen JP, Weinmann W, Marmillot P, Ghosh P, Lakshman R, Skipper GE, Neumann T, Spies C, Javors M, Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Akhtar F, Roache JD, Litten R. Emerging biomarkers: New directions and clinical applications. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:465–473. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156082.08248.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurst FM, Dresen S, Allen JP, Wiesbeck G, Graf M, Weinmann W. Ethyl sulphate: a direct ethanol metabolite reflecting recent alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2006;101:204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurst FM, Dursteler-MacFarland KM, Auwaerter V, Ergovic S, Thon N, Yegles M, Halter C, Weinmann W, Wiesbeck GA. Assessment of alcohol use among methadone maintenance patients by direct ethanol metabolites and self-reports. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1552–1557. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurst FM, Metzger J, Marker WISST. The ethanol conjugate ethyl glucuronide is a useful marker of recent alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1114–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurst FM, Skipper GE, Weinmann W. Ethyl glucuronide - the direct ethanol metabolite on the threshold from science to routine use. Addiction. 2003;98:51–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]