Abstract

Background

This paper provides an integrative review of existing risk factors and models for bulimia nervosa (BN) in young girls. We offer a new model for BN that describes two pathways of risk that may lead to the initial impulsive act of binge eating and purging in children and adolescents.

Scope

We conducted a selective literature review, focusing on existing and new risk processes for BN in this select population.

Findings

We identify two ways in which girls increase their risk to begin engaging in the impulsive behavior of binge eating and purging. The first is state based: the experience of negative mood, in girls attempting to restrain eating, leads to the depletion of self-control and thus increased risk for loss of control eating. The second is personality-based: elevations on the trait of negative urgency, or the tendency to act rashly when distressed, increase risk, particularly in conjunction with high-risk psychosocial learning. We then briefly discuss how these behaviors are reinforced, putting girls at further risk for developing BN.

Conclusions

We highlight several areas in which further inquiry is necessary, and we discuss the clinical implications of the new risk model we described.

Keywords: Risk factors, bulimia nervosa, young girls, risk models, binge eating, purging behavior

Introduciton

There is an extensive literature on the emergence of eating disordered behaviors in females during childhood and adolescence, including models of risk that have proven quite useful over the years. Research has also supported several risk factors, both recent and longstanding, that have yet to be incorporated into these existing theories. Thus, there is a need to build on those existing models and provide new, integrative models of risk for the emergence of BN in young girls. After briefly reviewing existing models and risk factors, we provide one such integrative model in this paper.

BN is a disorder characterized by recurrent and frequent episodes of binge eating (consuming an unusually large amount of food and feeling out of control) followed by recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior in an effort to prevent weight gain (such as self-induced vomiting) (American Psychiatric Association, or APA, 2013). Symptoms of BN often first occur in pre-adolescence: Consistently, researchers have found that pre-adolescent and adolescent girls engage in bulimic behaviors (e.g., Combs, Pearson, Zapolski, & Smith, 2013; Tanofsky-Kraff, et al., 2011). In fact, one study found the average age of binge eating onset to be as young as 8 years old (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2005). In young girls varying in age from 6 to 18 years old, about 15–24% report recent binge eating episodes (Stice, 2001; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2007). Although the prevalence of purging behavior is lower (about 4%: Stice, 2001), approximately half of those who binge eat by age 14 go on to develop compensatory behaviors by age 17 (Allen, Byrne, & McLean, 2013).

Bulimic pathology, even in adolescence, tends to be chronic. Only about 30–40% of adolescent girls treated for BN achieve full remission from bingeing and purging (le Grange, Crosby, Rathouz, & Leventhal, 2007) and the more severe the symptoms, the lower the recovery rates, even when treated by Family Based Therapy (FBT: le Grange, Crosby, & Lock, 2008), which is currently the most effective treatment available (Couturier, Kimber, & Szatmari, 2013). Given this finding, it is not surprising that the prevalence of BN behaviors tends to increase with age (Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Larson, Eisenberg, & Loth, 2011) and that eating disorder symptoms and risk behaviors in early adolescence are highly predictive of later, diagnosable disorders and ongoing symptomatic behavior (Kotler, Cohen, Davies, Pine, & Walsh, 2001). Anorexia nervosa (AN) and BN symptoms at the beginning of adolescence correlate greater than r = .40 with symptoms during adulthood, and diagnosable BN at the beginning of adolescence is associated with a 9-fold increase in BN and a 20-fold increase in AN during late adolescence (Kotler et al., 2001).

The chronicity of BN is striking in part because engaging in bulimic behaviors increases the risk of experiencing a number of health problems, many of which are quite physically uncomfortable, including enlarged salivary glands, significant and permanent loss of dental enamel, esophageal tears, gastric rupture, cardiac arrhythmias, obesity, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and production of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities (APA, 2013). Furthermore, individuals who suffer from BN also tend to struggle with depression, preoccupation with food, panic disorder, and phobias (APA, 2013). Adolescent girls who engage in compensatory behaviors are also more likely to engage in suicidal and self-harm behaviors (Laasko, Hakko, Rasanen, & Riala, 2013). Thus, the effects of BN on young girls’ lives are severe both physiologically and psychologically.

Given the profound negative consequences and the chronicity of binge eating and purging in young girls, a crucial question for eating disorder researchers is what risk factors make one vulnerable to initially engage in such behaviors? The purpose of this paper is to address this question by introducing one integrative risk model for BN in young girls. It is important to note that because the findings we present in this paper reflect existing eating disorder research, which has been conducted primarily with European American females in Western cultures (Striegel-Moore & Bulik, 2007), the theory we develop cannot be assumed to apply to non-European American girls. To begin, we first briefly describe long-standing BN risk models and the key risk processes of those models followed by both recent advances and well-established factors relevant to BN risk that have yet to be incorporated into those eating disorder models. There are other risk factors beyond those we review here; we focused on risk factors that play important roles in existing risk models. For a more detailed review of existing risk models and risk factors, we refer readers to (a) Jacobi, Hayward, de Zwaan, Kraemer, and Agras, 2004, and (b) Stice, 2002. We then introduce our integrative theory.

Existing Theories of Risk

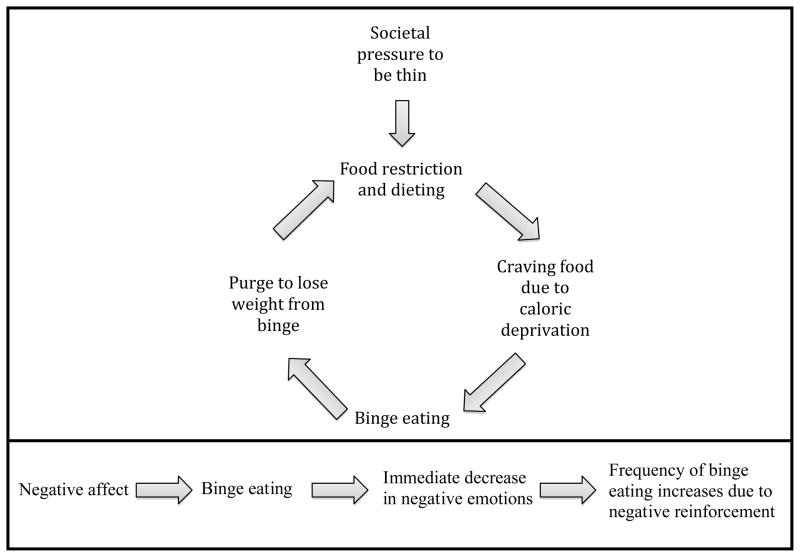

Classic Restraint Model of Risk

The classic restraint model for BN (Polivy & Herman, 1985; Striegel-Moore, Silberstein, & Rodin, 1986) proposes that, due to strong societal pressures for a thin physique, girls are at risk to begin dieting and restricting (see top panel of Figure 1). Once they begin restricting their food intake, their bodies feel deprived; they begin craving food, thus increasing the likelihood that they will binge eat. Of course, a binge eating episode is not in line with their goal of losing weight, so after a binge episode they purge in an effort to lose the weight they risk gaining from the binge eating episode. The girls will then begin restricting again in an effort to “recover” from the binge, thereby restarting the cycle.

Figure 1.

Classic restraint model of risk for bulimia nervosa (upper panel); emotion regulation model of binge eating (lower panel).

Many researchers have found cross-sectional and prospective evidence that dieting attempts predict the onset of binge eating and purging behavior among adolescent girls (e.g., Haines, Kleinman, Rifas-Shiman, Field, & Austin, 2010; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). Furthermore, a meta-analysis revealed dieting efforts to have a large effect size (z=3.68, p<.001) on BN symptoms in adolescents (Stice, 2002). Thus, it appears that when girls attempt to restrict their food intake, they are at increased risk for subsequent overeating. We next briefly highlight several factors that appear to be relevant for this model.

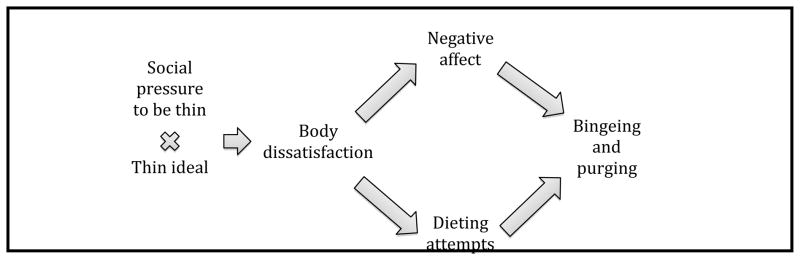

Thin ideal internalization

Through advertisements and many other forms of social communication, girls are consistently exposed to messages that thinness is good and if one is thin, one will be happy and successful (Rubinstein & Caballero, 2000). Many girls describe perceiving pressure to be thin (Stice, 2002). Despite the pervasiveness of this message, there are individual differences in the degree to which girls internalize the idea that thinness is the ideal, sought-after state. Those who do are likely to experience body dissatisfaction, due to the unrealistic nature of the ideal. As a result, they are at risk for excessive dieting, negative affect, and binge eating (Stice, 2001; Wertheim, Koerner & Paxton, 2001). Internalization of the thin ideal also predicts increases in eating pathology over time (Wertheim et al., 2001). Moreover, an intervention that reduces thin-ideal internalization in adolescent girls was shown to result in decreases in body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, and bulimic symptoms (Stice, Mazotti, Weibel, & Agras, 2000). Thus, girls who tend to internalize this thin-ideal body type are at greater risk to feel dissatisfied with their body and then diet, thereby putting them at risk to binge eat and purge.

Body dissatisfaction

If a girl feels dissatisfied with her body, she is much more likely to attempt to diet (Stice, 2001; Wertheim et al., 2001), experience negative affect (Cole, Martin, Peeke, Seroczynski, & Hoffman, 1998), or engage in bulimic behaviors (e.g., Stice & Agras, 1998). Body dissatisfaction predicts bulimic symptom onset (Stice, Marti, & Durant, 2011), increases in bulimic pathology (Stice, 2001), and increases in other forms of eating pathology (Wertheim et al., 2001). Dieting efforts and negative affect were shown to mediate the predictive influence of body dissatisfaction on bulimic behaviors (Stice & Shaw, 2002). It appears to be the case that girls who are dissatisfied with their bodies are at increased risk to feel distress and to diet, and that those behaviors in turn increase risk for bulimic pathology.

Modeling and social reinforcement

Higher family and peer modeling of abnormal eating behaviors prospectively predicts the onset of binge eating and purging (Stice, 1998). Similarly, when girls receive social reinforcement of the thin-ideal from their family and peers, they are at greater risk for binge eating and purging in the future (Stice, 1998). This sociocultural influence, particularly from family and peers, in youth appears to lead to greater internalization of the thin-ideal, leading to body dissatisfaction and dieting attempts, thus setting the stage for BN behavior (Keery, van den Berg, & Thompson, 2004).

It thus seems that attempts to restrict food intake, based at least in part on dissatisfaction with one’s body stemming from internalization of the thin-ideal, leads to binge eating and then purging behavior in girls. However, given the strong societal norms in Western culture that promote very thin female bodies as ideal (Miller & Pumariega, 2001), the “thin ideal” environment appears to be ubiquitous, at least for European American girls (Polivy & Herman, 1985; Striegel-Moore et al., 1986). So, why is it that some girls experience significant body dissatisfaction and strongly internalize the thin ideal and others do not? Thus, one limitation of this model is that it does not incorporate person-centered factors that may be important for understanding which girls are most likely to begin the food restriction–binge/purge cycle. We next briefly describe a second established model of risk that focuses more heavily on characteristics of the person, rather than characteristics of the environment.

Emotion Regulation Model of Risk

The second existing theory places a much stronger emphasis on personal characteristics; it emphasizes emotion regulation (see bottom panel, Figure 1). This theory proposes that girls who frequently experience high levels of negative emotions are at risk to binge eat in an effort to alleviate the negative emotion (e.g., Agras & Telch, 1998). The theory posits that binge eating thus provides negative reinforcement: Negative emotions decrease after the binge is complete (although there is some evidence to suggest this may not be the case in the immediate aftermath of a binge: Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011). Escape theory is a similar model with one potentially important difference. According to escape theory, focus on a binge facilitates escape from self-awareness, and thus escape from awareness of distress. As a result, negative emotions decrease just prior to and perhaps during the binge eating episode as opposed to after the binge eating episode (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). Consistent with this model, altered self-awareness, analogous to dissociation, predicts subsequent binge episodes (Engelberg, Steiger, Gauvin, & Wonderlich, 2007). The two models differ with respect to the timing of the negative reinforcement, but both view binge episodes as providing negative reinforcement and thus increasing in frequency over time. We next highlight important and related factors for this model.

Negative affect

In order for a girl to binge eat, according to the emotion regulation and escape models, she must experience negative affect. Negative affect is associated with a multitude of psychological disorders, including eating disorder onset and maintenance. Not only is negative affect a risk factor for BN, but also for body dissatisfaction and high caloric intake (Stice, 2002). In a young, community sample of girls, negative emotionality predicted disordered eating (Leon, Fulkerson, Perry, Keel, & Klump, 1999) and was associated with eating disorder attitudes and cognitions (Klump, McGue, & Iacono, 2002). A meta-analysis of laboratory studies found a larger relationship between negative affect and binge eating when participants were allowed to eat during the negative mood induction as opposed to after (Stice, 2002). Thus, binge eating was tied very close in time to the experience of negative affect, suggesting the possibility that binge eating serves a function in response to distress. Moreover, in children and adolescents with eating disorders, those girls who were also depressed tend to have more complex and severe eating disorder presentations and symptoms than those without mood disorders (Hughes et al., 2013). This suggests the importance of negative emotionality in BN risk.

Emotional eating

Research on emotional eating has demonstrated a clear link between negative affect and food. Emotional eating can be defined as “eating in response to a range of negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger, and loneliness, to cope with negative affect” (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2007). Girls who engage in emotional eating are more likely to experience a loss of control, or feel as if they cannot stop, when they eat during the experience of negative emotions (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2007). Emotional eating is present in children and adolescent girls (e.g., Shapiro et al., 2007) and is associated with body dissatisfaction and BN symptoms (Braet et al., 2008; Vanucchi et al., 2013).

The emotion regulation and escape models offer something not offered by restraint theory, which is an account of one way in which individual differences in personality influence risk for BN. The possibility that bulimic behaviors serve as a potent affect-based reinforcer is an appealing one, as researchers seek to explain how BN is maintained despite the many harms it brings. Along with the strengths of these two models is one potentially important shortcoming. The emotion regulation and escape theories do not systematically address characteristics of the environment nor do they include specific psychosocial learning mechanisms (other than negative reinforcement) that increase risk. That is, the models say little about why, when experiencing significant negative affect, a girl would choose to binge eat and purge. There are many possible routes to negative reinforcement/reduction of negative affect; some are more adaptive and some less adaptive; Why binge eat and purge?

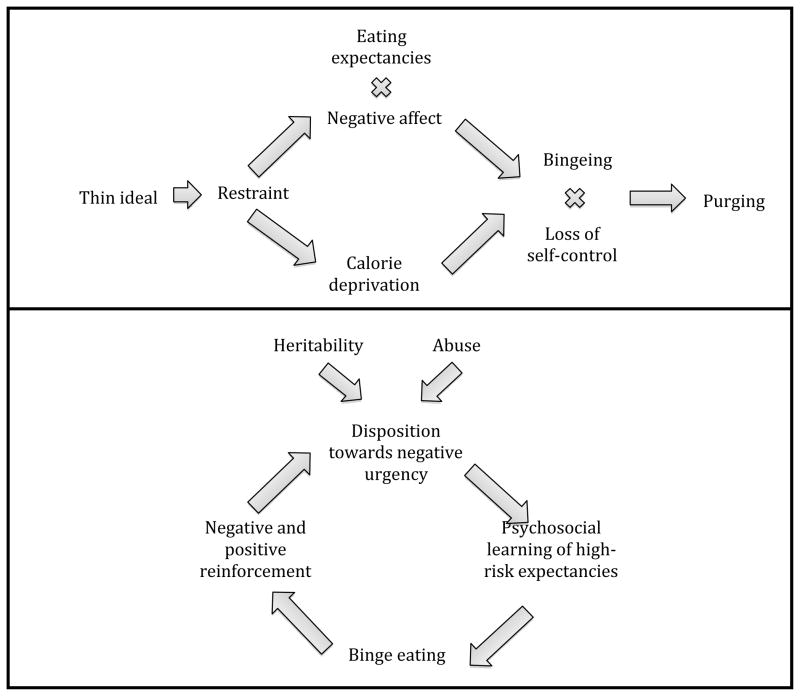

Dual Pathway Model of Risk

The dual-pathway model provides one integration of these risk factors (see Figure 2). In this model, internalization of the thin ideal leads to body dissatisfaction, resulting in more dieting attempts and higher levels of negative affect, which together increase risk for bulimic pathology in girls (Stice, Nemeroff, & Shaw, 1996; Stice, 2001). Thus, negative affect and dieting both mediate the relationship between body dissatisfaction and binge eating and purging, providing two pathways of risk. One pathway suggests that girls experience negative affect because they feel badly about themselves and their bodies, which then leads to binge eating as a way to be comforted or distracted from their negative emotions. The second pathway is, essentially, the restraint model. This model is noteworthy in its integration of risk due to environmental learning events and emotional responsiveness.

Figure 2.

Dual pathway model for bulimia nervosa

There is cross-sectional and longitudinal support for the dual pathway model among adolescents (e.g., Stice, 2001; Stice, Presnall, & Spangler, 2002). However, recent findings suggest the need to modify both the restraint and dual-pathway models of risk. Some researchers have found that dieting does not predict eating disordered behavior among adolescents (e.g., Johnson & Wardle, 2005). In fact, girls in a healthy weight control intervention who were put on a diet showed decreased bulimic pathology over time, along with decreased food intake, and decreased negative affect (Stice, Presnell, Groesz, & Shaw, 2005).

An important consideration in understanding these findings is how dieting is defined. There are girls who are not preoccupied with food; their dieting does not increase their risk for developing BN symptoms (Stice et al., 2005). Other girls tend to overvalue appearance and are preoccupied with food. When they make repeated efforts to restrain their food intake, they are at risk for binge eating and purging (Stice et al., 2005; Stice et al., 2002). There appears to be a distinction between girls at risk to cycle between restriction of food intake and dyscontrol, for whom the dual pathway model works well, and girls who engage in uncomplicated, successful dieting.

There are several reasons to build on these existing models. First, the chronicity of BN in girls and low recovery rates (even after treatments developed in part based on these models: le Grange et al., 2007) indicates the need to pursue more complete understanding of BN onset. Second, there are additional risk factors, some well-established and others recently identified, that have not yet been integrated into BN risk models. Third, there is evidence that adding other factors to BN risk models, including personality characteristics such as dispositions toward impulsive behavior, leads to increased success in predicting bulimic symptomatology (Von Ranson & Schnitzler, 2007).

Toward A New Model of Risk

The theory we propose is, in many ways, a direct extension of these existing models. We rely on research supporting these models together with several advances and well-established findings in the basic psychological literature to present an account that includes person, environmental, and learning factors, as well as transactions among them, to explain the initiation of bulimic behaviors in young girls. Our theory is intended to account for what sets the stage for the first binge eating and purging episode. Although we believe this theory takes the field closer to a comprehensive understanding of the etiology of BN, there are important limits to what we intend to achieve in this paper. We understand the theory we describe as relevant to a large subset of girls with BN, but we do not assume our account explains the risk process for all such individuals.

A useful way to understand the development of BN is that initial bingeing and purging are typically considered impulsive or rash acts. Indeed, initial engagement in many potentially harmful behaviors is often described as impulsive. Early binge eating and purging episodes, consumption of large amounts of alcohol, decisions to have sex with someone one has just met, or betting far more money than intended are all thought to involve acting on an impulse or acting rashly. Engaging in such behaviors appears to be characterized by a focus on meeting one’s immediate need, or acting on an immediate urge, without due consideration of the possible negative consequences of the act with respect to one’s long-term interests, goals, or health. One way to describe impulsive or rash acts is in terms of failures of, or ongoing deficits in, self-control. When a girl engages in her first binge eating and purging episode, she may do so to address her immediate need or urge, even though doing so has potential negative effects and is almost certainly not in line with her long-term interests.

We begin explication of our theory for initial impulsive engagement in BN behavior by first briefly introducing relevant and important risk factors from four broad domains: (a) personality, (b) genetics, (c) self-control theory, and (d) environmental effects. We then integrate several risk factors by presenting two risk pathways that may lead a young girl to engage in the rash, impulsive behavior of binge eating and purging: One is a state-based, or within-persons pathway and the other is a trait-based, or between-persons pathway. Next, we briefly propose how this behavior may become ongoing in the future and conclude by offering considerations for clinical interventions and treatments for BN.

Personality: Impulsivity and Negative Urgency

Engagement in binge eating and purging behavior has often been described as impulsive, and personality measures related to impulsive behavior do predict those behaviors longitudinally (Stice, 2002). For current purposes, we define the term “impulsivity” with respect to behavior: Impulsivity refers to rash behavior that is characterized by a focus on meeting one’s immediate need, or acting on an immediate urge, without due consideration of the possible negative consequences of the act with respect to one’s long-term interests, goals, or health. Numerous researchers have recognized that the personality underpinnings to rash or impulsive action are multi-faceted (e.g., Depue & Collins, 1999; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Indeed, models involving identification of a single or overall impulsivity personality trait have failed to conform to empirical data (Smith et al., 2007a). Instead, researchers consistently find a set of separate personality traits, each of which disposes individuals to impulsive or rash actions; these different traits are only moderately related to each other (Cyders & Smith, 2007; Smith et al., 2007a; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001).

One approach to the partitioning of traits related to impulsive behaviors has consistently identified a trait reflecting a disposition toward rash, impulsive action when distressed, which has been labeled by researchers as negative urgency (Cyders & Smith, 2007, 2008a; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). This impulsivity-trait correlates very modestly with other impulsivity-related traits, such as lack of deliberation, lack of perseverance, sensation seeking, positive urgency, and the behavioral activation scales of reward responsiveness, drive, and fun seeking (Cyders & Smith, 2007; Cyders et al., 2007; Carver & White, 1994) and is the only trait that consistently predicts binge eating (Fischer & Smith, 2008) and purging (Combs, Pearson, & Smith, 2011; Pearson, Combs, & Smith, 2010). Negative urgency also distinguishes individuals with BN from controls (Cyders et al., 2007). Whereas general measures of impulsive personality have very modest effects on bulimic symptoms (Stice, 2002), negative urgency had a weighted effect size for concurrent prediction of bulimic symptoms of r = .38 in a meta-analysis (effect sizes for other impulsivity-related traits ranged from .08 to .16: Fischer, Smith, & Cyders, 2008). Perhaps most important is that negative urgency prospectively predicts binge eating in college women (Anestis, Selby, & Joiner, 2007; Fischer, Peterson, & McCarthy, 2013) and in girls making the transition from elementary to middle school (Pearson, Combs, Zapolski, & Smith, 2012).

As is true with respect to negative affect, negative urgency is not specific to eating disorders. Rather, it confers transdiagnostic risk, even in young girls, predicting subsequent increases in heavy drinking, smoking, risky sex, drug use, gambling, binge eating, and other behaviors (e.g., Anestis et al., 2007; Cyders & Smith, 2008b; Doran et al., 2012; Fischer et al., 2013; Zapolski, Cyders, & Smith, 2009). It can be thought of as a disposition favoring the pursuit of immediate rewards, even when such pursuit compromises access to delayed rewards pertaining to health and well-being. Below, we describe one mechanism by which negative urgency can result in bulimic behaviors.

The Heritable Nature of Bulimic Behaviors

The heritability of bulimic behaviors is an important topic that has not been integrated into the existing models of BN. It appears to be the case that heritability is negligible prior to pubertal onset in girls and then rises dramatically with puberty. For example, Klump, McGue, and Iacono (2003) found that heritability of eating disorder symptoms was 0% in pre-pubertal 11 year old twins, 54% in pubertal 17 year old twins, and pubertal 11 year old twins had similar heritability as the 17 year old twins. This finding has been replicated (eg., Culbert, Burt, McGue, Iacono, & Klump, 2009). Once girls go through puberty, twins who share 100% of their genes are much more similar to each other in eating disorder symptomatology than are twins who on average share only 50% of their genes. Prior to pubertal onset, monozygotic twins are no more similar to each other than are dizygotic twins. Of course, if there were no variability in eating disorder symptoms among 11 year olds, restriction of range would preclude covariation as a statistical matter. However, Klump et al. (2003) found meaningful variability in eating disorder symptoms among all three groups: Prepubertal 11 year old girls, postpubertal 11 year old girls, and 17 year old girls.

The possible roles of negative affect and negative urgency in eating disorder heritability

Racine and colleagues (2013) found that a sizable portion of the relationships between both negative affect and binge eating, and negative urgency and binge eating, was explained by genetic factors, with a small portion explained by non-shared environmental factors. Thus, one expression of the heritability of BN may be through the risk factors of negative affect and negative urgency, particularly post-puberty. A large portion of the genetic covariation was shared among negative affect, negative urgency, and disordered eating, but the two traits each had independent genetic and non-shared environmental effects as well.

Failures of Self-Control

One characteristic of brain development in adolescence is that development of motivational and emotional subcortical connections occurs faster than development of connections that support prefrontal cortex (PFC) activity (Casey & Caudle, 2013). This imbalance in rate of development is important, because certain aspects of PFC activity modulate emotional reactivity (Maxwell & Davidson, 2007). One result is that adolescents, compared to children and adults, rely more on motivational/emotional subcortical brain activity to guide behavior. A consequence is that when teens are experiencing intense emotion, they are more likely that children or adults to act in rash or impulsive ways (Casey & Caudle, 2013); that is, they are more prone to failures of self-control than are children or adults. A closely related literature concerns momentary failures in self-control, following depletion of self-control resources (Inzlicht & Gutsell, 2007; Muraven & Baumeiester, 2000). Little research has been done on this effect in children, although Bucciol, Houser, and Piovesan (2011) found a comparable effect in grade school children.

The self-control literature is relevant to risk for BN because of two key events that tax self-control resources. First, attempts to restrain food consumption, particularly while hungry, require the exercise of self-control. Indeed, currently dieting women perform worse on a variety of cognitive tasks than others (Jones & Rogers, 2003). Second, the experience of negative mood requires self-control resources to monitor the distressing state and choose behavioral responses to it. The combination of negative mood and dieting can thus lead to loss of control and engagement in bulimic behaviors in adults (Yeomans & Coughlan, 2009). Whether this is true in children and adolescents is an important empirical question; certainly adolescents appear to be at great risk for such loss of control.

Environmental Factors

Expectancies for reinforcement from eating and from thinness

The concept of learned expectancies that certain behaviors or states provide reinforcement derives from basic learning theory. From this perspective, expectancies represent summaries of individuals’ learning histories; they are formed based on a multitude of direct and vicarious learning experiences that individuals undergo (e.g., Bolles, 1972; Tolman, 1932). The expectancies one forms then influence one’s future behavioral choices. One tends to engage in behaviors from which one expects rewards and avoid behaviors for which one expects punishment. Eating disorder expectancy theory holds that girls form different expectancies for the consequences of eating and thinness because they are exposed to different learning experiences (Hohlstein, Smith, & Atlas 1998). To the extent that one comes to associate eating with more powerful reinforcers than do others, one will then hold unusually strong expectancies for reinforcement from eating. One therefore will pursue food with greater vigor. To the extent that one forms stronger expectations that thinness brings a range of reinforcers, one will pursue thinness more vigorously. Eating disorder symptoms can be understood as extreme eating and dieting behavior, which is thought to stem from extreme or unusual learning histories (Combs & Smith, 2009; Hohlstein et al., 1998).

Eating expectancies

Girls differ in their expectancies about eating. Due to their personalities and learning histories, some girls form unusually strong expectancies that eating helps manage one’s negative affect (e.g., Hohlstein et al., 1998; MacBrayer, Smith, McCarthy, Demos, & Simmons, 2001; Simmons, Smith, & Hill, 2002; Smith, Simmons, Flory, Annus, & Hill, 2007b). These eating expectancies have been shown to correlate cross-sectionally with symptom level in child (Combs et al., 2011; Pearson et al., 2010), adolescent (MacBrayer et al., 2001; Simmons et al., 2002) and adult samples (Hohlstein et al., 1998). Women with BN endorse eating expectancies more strongly than women with AN, normal controls, and psychiatric controls (Bruce, Mansour, & Steiger, 2009). Longitudinally, these expectancies predict binge eating, including binge eating onset, in longitudinal samples of adolescent girls (Pearson et al., 2012a; Smith et al., 2007b) and college women (Fischer et al., 2013). In a sample of early adolescent girls, endorsement of the expectancy that eating helps alleviate negative affect predicted membership in trajectory groups characterized by a large increase in binge eating during early adolescence (Smith et al., 2007b). In contrast, women who do not expect eating to alleviate their distress tend to eat less when distressed (Tice, Bratslavsky, & Baumeister, 2001).

Among the factors that appear to contribute to the formation of this eating expectancy are family of origin experiences. Maternal modeling of the use of food to alleviate distress correlates with young adult disordered eating (MacBrayer et al., 2001); young adult women who recall their mother eating when distressed, or feeding them in response to their distress, report greater bulimic symptomatology than other women. An additional factor is being teased by one’s family about one’s weight. Young adult women who report having been teased about their weight as children also report greater bulimic symptomatology in adulthood. The predictive influence of both environmental events appears to be mediated by the expectancy that eating helps manage negative affect (MacBrayer et al., 2001).

Thinness expectancies

Girls also differ in their expectancies for thinness. Strong endorsement of the expectancy that thinness leads to overgeneralized life improvement also correlates cross-sectionally with child (Combs et al., 2011), adolescent (MacBrayer et al., 2001; Simmons et al., 2002), and adult symptom levels (Hohlstein et al., 1998). Endorsement of expectancies for reinforcement from thinness differentiate women with BN and women with AN from both normal and psychiatric controls (Hohlstein et al., 1998), but not the two eating disorder groups from each other. Longitudinally, thinness expectancy endorsement also predicted membership in trajectory groups characterized by increases in binge eating and purging behavior among middle school girls (Smith et al., 2007b). In an experimental study, reduction of thinness expectancies produced a reduction in eating disorder symptoms (Annus, Smith, & Masters, 2008).

Thus, girls with BN simultaneously hold unusually strong expectancies that eating helps alleviate their negative affect and that thinness leads to overgeneralized life improvement (Hohlstein et al., 1998). Concurrent investment in these two opposite pursuits maps onto the bulimic behaviors of binge eating and purging.

Childhood Sexual and Physical Abuse

Childhood abuse is a transdiagnostic risk factor that is related to the subsequent emergence of numerous maladaptive behaviors. There is clear evidence for its importance in risk for BN, as well as some evidence that the process by which it may increase risk relates to existing, identified risk processes. In terms of BN, childhood sexual abuse is associated with heightened binge eating, purging, weight dissatisfaction, and the pursuit of thinness (Sanci et al., 2008; Thompson, Wonderlich, Crosby, & Mitchell, 2001; Wonderlich et al., 2000). The emergence of eating disorder symptoms is particularly pronounced for adolescents who have experienced both sexual and physical abuse (Neumark-Sztainer, Story, Hannan, Beuhring, & Resnick, 2000), although sexual abuse alone is associated with symptoms in adolescent girls (Thompson et al., 2001). Longitudinal studies suggest that sexual abuse and physical neglect during childhood put women at elevated risk for developing an eating disorder during adolescence or early adulthood (Jacobi et al., 2004).

Childhood abuse has been found to be associated with brain changes that are linked to increased negative affect, emotional reactivity, and impulsive behavior (Davidson, 2003), all of which are also associated with symptoms of BN. For example, basic theory ties elevations in negative urgency to a functional brain system relating the amygdala and parts of the PFC (Cyders & Smith, 2008), such that reduced PFC modulation of amygdala activity leads to rash action when distressed (see Lock, Garrett, Beenhakker, & Reiss, 2011; and Marsh et al., 2011, for two related fMRI investigations of adolescents with BN). Interestingly, chronic exposure to childhood abuse appears to alter brain functioning in part by increasing amygdala activity and reducing PFC control over amygdalar responses (Teicher et al., 2003). Whether an abuse history influences negative urgency levels is an open empirical question. Thus, one possible mechanism by which the environmental event of childhood abuse may increase risk is by increasing the likelihood of experiencing personality-based risk factors such as negative affect and negative urgency.

Two Pathways Toward Impulsive Action: An Integrated Risk Model for BN

We propose an integration of existing models of BN with the advances summarized above that delineates two pathways to BN in young girls. Early engagement in binge eating and purging behaviors can be understood as impulsive, or as a failure of self-control, in that the behaviors may meet an immediate need, or be a response to an urge, but they are inconsistent with one’s ongoing interests and goals. The existing evidence points to both a “state” and a “trait” pathway to BN.

State Based Pathway: Self-Control Depletion -Based Risk

The first process is highly similar to the classic restraint and dual pathway models of risk (Polivy & Herman, 1985; Stice et al., 1996) with the addition of eating disorder expectancy theory and self-control depletion theory (see top panel of Figure 3). Some girls may be at increased risk for binge eating and purging as a result of momentary behaviors and emotional experiences. Due to features of their psychosocial learning histories, some girls form unusually strong expectancies that thinness will provide overall life improvement and also that eating helps alleviate negative affect. These girls thus embrace the thin ideal. Because that ideal is typically unattainable, they experience body dissatisfaction and, sometimes, distress. They attempt to restrain their food intake, but doing so (a) works against a basic biological drive and (b) is made even more difficult due to their learned expectancies for the benefits of eating. Thus, restraining food intake involves exertion of considerable self-control. Some of these girls are likely to experience negative affect, no doubt for many reasons, including body dissatisfaction and perhaps personality changes due to past exposure to sexual or physical abuse. The distress requires further self-control to inhibit immediate, non-adaptive responses to distress. As a result, they risk loss of control over their basic biological drive to eat, and thus are more likely to binge eat. The combination of intense negative mood, endorsement of the thin ideal and resulting body dissatisfaction, accompanying efforts at self-control of food intake, and expectancies that eating will help alleviate distress together place too heavy a burden on self-control mechanisms, increasing risk for momentary loss of control and impulsive engagement in bulimic behaviors. Put differently, the failure of self-control reflects pursuit of an immediate reward, food consumption, at the expense of the delayed (and likely unrealistic) reward of attainment of the thin ideal.

Figure 3.

State-based pathway: restraint theory-based risk (upper panel); trait-based pathway: negative urgency-based risk (lower panel)

Trait-Based Pathway: Negative Urgency-Based Risk

The second pathway toward engagement in the impulsive acts of binge eating and purging we understand to reflect ongoing, stable deficits in self-control that can be measured as negative urgency (see bottom panel of Figure 3). That is, in addition to increased risk for impulsive binge eating and purging due to self-control failures following dieting and negative affect, girls also vary on a trait level in their tendency to act in rash, impulsive ways when distressed (Cyders & Smith, 2008). That is, they vary in their tendency to act in pursuit of immediate rewards, such as reduction of distress, when such action compromises their pursuit of delayed but more adaptive rewards, often pertaining to health and well-being. Individual differences in negative urgency, in girls at least as young as 5th grade, are reliable, stable, consistent across source of assessment, and distinct from other impulsivity-related measures (Zapolski, Stairs, Settles, Combs, & Smith, 2010). The trait does predict the onset of bulimic behaviors and increases in those behaviors across the developmental transition from elementary school to middle school (Pearson et al., 2012). Because negative urgency is a broad trait, researchers have investigated mechanisms by which the trait confers risk for bulimic behaviors in young girls.

The Formation of Eating Expectancies: The Acquired Preparedness model of risk

Developed from person-environment transaction theory (Caspi, 1993; Caspi & Roberts, 2001), research has supported a model in which eating expectancies are formed during transactions between girls’ personalities and environmental events to which they have been exposed. Basic research has shown that individuals with different traits can learn different things, and thus form different expectancies, from what is objectively the same learning experience (Smith, Williams, Cyders, & Kelley, 2006). Thus, traits help shape the learning process; girls with different traits are disposed (or prepared) to learn different things. Because one’s learning influences one’s behavior, it seems that the influence of disposition on behavior is mediated by psychosocial learning.

This risk process has been termed acquired preparedness (AP), to denote the theory that girls are differentially prepared to acquire high risk expectancies as a function of high-risk personality traits (Smith et al., 2006). Applied to eating disorders, the AP model of risk is as follows (Combs & Smith, 2009). Girls high in negative urgency are disposed to act to alleviate distress; often, their actions are rash or impulsive (Settles et al., 2012). When girls high in this trait are exposed to learning experiences (whether direct or modeled) that involve eating when distressed, they are biased to form expectancies associating the behavior of food consumption with the negative reinforcement of distress relief (Fischer et al., 2008). This expectancy, in turn, is understood as the proximal risk factor that increases the likelihood of binge eating behavior (Smith et al., 2007b). Thus, over time, negative urgency predicts stronger endorsement of the expectancy that eating will help alleviate distress, and the expectancy endorsement, in turn, predicts subsequent binge eating behavior. This process has been shown in cross-sectional (Combs et al., 2011; Pearson et al., 2010) and longitudinal (Pearson et al., 2012) eating disorder research with young girls.

State-by-Trait Interaction

To understand how bulimic behaviors occur for a given person in a given moment, it is necessary to develop models integrating state-based and trait-based risk processes. The model we have described leads directly to hypotheses integrating individual difference and momentary risk processes. No specific tests of this kind of state by trait interaction have yet been conducted, but literature suggests the possibility of an interaction between trait-based measures and momentary state-based assessments (e.g., Engel et al., 2007; Wonderlich et al., 2007). One possibility is this: Girls who are high in negative urgency are at elevated risk for binge eating and purging, particularly so when they experience momentary depletions in self-control. That is, girls with the disposition to act rashly when distressed who have taxed their self-control resources, perhaps through efforts to diet and/or manage a negative mood state, are at the greatest risk to engage in some form of rash, impulsive behavior. If they also expect eating to alleviate negative mood states, the impulsive behavior that ensues is more likely to be binge eating. If they expect thinness to lead to overgeneralized life improvement, they are more likely to purge following the binge. We believe that an important direction for risk research is to investigate this possibility along with other possible transactions between situations and stable personal characteristics.

Toward Ongoing, Repeated Bulimic Behavior

Of course, in order for these girls to go on to meet diagnostic criteria for BN, they must repeatedly engage in the act of bingeing and purging. We next offer one possible explanation for the continued engagement in bulimic behaviors, based on the existing literature. The initial binge eating act is likely reinforced both positively, due to the pleasure of consuming favored but avoided foods (Small, Jones-Gotman, & Dagher, 2003), and negatively, through a decrease in distress, likely due to distraction from the distress as one focuses on the binge (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Smyth et al., 2007). Both the positive and negative reinforcement from the binge occur very quickly: Both the pleasure and the distraction characterize the initial stages of a binge episode. Following the binge, a girl’s self-awareness returns and either (a) she recognizes how much food she has eaten, how uncomfortably full she feels, and she feels distress or shame due to her failure of control; or (b) if she also purged, she feels physical discomfort, disappointment at having engaged in purging behavior, concern about her capacity to maintain the pursuit of thinness, and, again, distress or shame due to her failure of control.

Because of the prompt positive and negative reinforcement from the bulimic episode, the process is reinforced, as is her expectancy that eating will alleviate negative mood. Since she believes that eating alleviates her negative affect, this expectancy is reinforced and strengthened, making it more likely that she will engage in the behavior again in the future when she is distressed. Furthermore, following the act, her increase in distress increases (a) the likelihood for subsequent loss of control or (b) negative urgency-based action. Bulimic events become more likely. The risk cycle begins to perpetuate itself.

Clinical Implications and Conclusion

Many aspects of the theory we have described follow directly from existing literature; at the same time, articulation of the theory highlights the need for further empirical investigation of many aspects of the risk process. For example, is it true that girls high in trait-based risk, i.e., negative urgency, are more likely to respond to momentary depletions of self-control with bulimic episodes? How does that process work? Do girls high in negative urgency experience depletion sooner than others? Or, are they simply more likely to engage in bulimic behaviors at the same level of self-control depletion as others? Although eating and thinness expectancies appear to be influenced by negative urgency, to what degree do elevations on the expectancies confer risk at low or moderate levels of negative urgency? There is evidence that expectancies mediate the influence of negative urgency on bulimic behaviors: Is there also a moderation effect, in which the combination of elevations in both negative urgency and expectancies uniquely heighten risk? Why do some girls only experiment with bulimic behaviors, while others go on to develop BN? Do the former girls experience the state-based risk of self-control failure but lack the trait-based risk that might make such experiences more frequent? Or, do they share the same risk factors but at milder levels? These any many other questions are currently unanswered and merit investigation.

To the extent that our theory holds true, it will be important to develop interventions for BN that incorporate the risk factors presented in our model. Given the importance of family and environment on girls, family therapy for BN may be enriched through greater provision of negative urgency-based and self regulation-based interventions including an emphasis on: (a) emotional awareness and emotion regulation, (b) distress tolerance in the moment, and (c) identification of and pursuit of long-term goals. Interventions may also benefit from including cognitive restructuring of the learned expectancies about eating and thinness (Annus et al., 2008).

We have briefly reviewed literature on BN in young girls that have made it possible to update classic BN theories of risk. In doing so, we have offered one such update in our state-based and trait-based model of BN. From this perspective, the early engagement in binge eating and purging behavior can be understood as an impulsive act, in that it represents a response to an immediate urge or need, without due consideration of the impact of the act on one’s ongoing interests and goals. There is considerable evidence that, based on psychosocial learning histories, some girls attempt to diet. If those girls also expect eating to help alleviate negative affect, the dieting attempts, in combination with distress, overly tax their self-control resources, with the result that they lose control and impulsively binge eat and purge. There is also evidence that some girls are dispositionally inclined to act rashly when distressed, and that disposition can, given a learning history emphasizing the benefits of eating and of thinness, increase risk for the rash or impulsive engagement in bulimic behaviors.

Key Points.

Onset of bulimia nervosa (BN) often occurs in children and adolescents and is often described as impulsive in nature.

Restraint, body dissatisfaction, thin-ideal internalization, and negative emotionality are predictors of BN that have been integrated in existing BN risk models.

Recent advances and other well-established findings highlight the roles of personality, heritability, self-control, childhood abuse, and learning in the development of bulimic behaviors.

Two new risk pathways integrate existing and current literature: One is state-based and focuses on self-control failure and restraint; the other is trait-based and focuses on negative urgency.

Initial engagement in bulimic behaviors, whether due to self-control failures or high negative urgency, provide prompt positive and negative reinforcement, thus increasing the likelihood of the emergence of BN.

Acknowledgments

Development of this paper was supported, in part by NIAAA R01 AA 016166 to G.T.S.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest statement: No conflicts declared

All authors have declared that there are no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Agras WS, Telch CF. Effects of caloric deprivation and negative affect on binge eating in obese binge eating disordered women. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Allen KL, Byrne SM, Oddy WH, Crosby RD. Early Onset Binge Eating and Purging Eating Disorders: Course and Outcome in a Population-Based Study of Adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:1083–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9747-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The role of urgency in maladaptive behaviors. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:3018–3029. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annus AM, Smith GT, Masters K. Manipulation of thinness and restricting expectancies: Further evidence for a causal role of thinness and restricting expectancies in the etiology of eating disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:278–287. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolles RC. Reinforcement, expectancy and learning. Psychological Review. 1972;79:394–409. [Google Scholar]

- Braet C, Claus L, Goossens L, Moens E, Van Vlierberghe L, Soetens B. Differences in eating style between overweight and normal-weight youngsters. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13:733–743. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce K, Mansour S, Steiger H. Expectancies related to thinness, dietary restriction, eating, and alcohol consumption in women with bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:253–258. doi: 10.1002/eat.20594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciol A, Houser D, Piovesan M. Temptation and productivity: A field experiment with children. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 2011;78:126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Caudle K. The teenage brain: self control. Psychological Science. 2013;22:82–87. doi: 10.1177/0963721413480170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A. Studying lives through time: Personality and development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1993. Why maladaptive behaviors persist: Sources of continuity and change across the life course; pp. 343–376. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW. Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry. 2001;12:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Fornieles J, Bigorra A, Martinez-Mallen E, Conzalez L, Moreno E, Font E, Toro J. Motivation to change in adolescents with bulimia nervosa mediates clinical change after treatment. European Eating Disorders Review. 2011;19:46–54. doi: 10.1002/erv.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Peeke LG, Seroczynski AD, Hoffman K. Are cognitive errors of underestimation predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:481–496. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Pearson CM, Smith GT. A risk model for pre-adolescent disordered eating. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:596–604. doi: 10.1002/eat.20851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Smith GT. Personality factors and acquired expectancies: Effects on and prediction for binge eating. In: Chambers N, editor. Binge eating: Psychological factors, symptoms, and treatment. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Pearson CM, Zapolski TC, Smith GT. Preadolescent disordered eating predicts subsequent eating dysfunction. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2013;38:41–49. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier J, Kimber M, Szatmari P. Efficacy of family-based treatment for adolescents with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;46:3–11. doi: 10.1002/eat.22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KM, Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Klump KL. Puberty and the genetic diathesis of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:788–796. doi: 10.1037/a0017207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008a;6:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Clarifying the role of personality dispositions in risk for increased gambling behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008b;45:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the urgency traits over the first year of college. Journal of Personality. 2010;92:63–69. doi: 10.1080/00223890903381825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Darwin and the neural basis of emotion and affective style. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2003;1000:316–336. doi: 10.1196/annals.1280.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: DA, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22:491–569. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran N, Khoddam R, Sanders PE, Schweizer CA, Trim RS, Myers MG. A prospective study of the acquired preparedness model: The effects of impulsivity and expectancies on smoking initiation in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0028988. published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SG, Boseck JJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, Smyth J, Miltenberger R, Steiger H. The relationship of momentary anger and impulsivity to bulimic behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg MJ, Steiger H, Gauvin L, Wonderlich SA. Binge antecedents in bulimic syndromes: an examination of dissociation and negative affect. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:531–536. doi: 10.1002/eat.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Peterson CM, McCarthy D. A prospective test of the influence of negative urgency and expectancies on binge eating and purging. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:294–300. doi: 10.1037/a0029323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT. Binge eating, problem drinking, and pathological gambling: Linking behavior to shared traits and social learning. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:789–800. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT, Cyders MA. Another look at impulsivity: A meta-analytic review comparing specific dispositions to rash action in their relationship to bulimic symptoms. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1413–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychological Bullet. 2011;137:660–681. doi: 10.1037/a0023660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines J, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, Austin SB. Examination of Shared Risk and Protective Factors for Overweight and Disordered Eating Among Adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:336–343. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self- awareness. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Wagner DD. Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohlstein LA, Smith GT, Atlas JG. An application of expectancy theory to eating disorder: Development and validation of measures of eating and dieting expectancies. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes EK, Goldschmidt AB, Labuschagne Z, Loeb KL, Sawyer SM, Le Grange D. Eating Disorders with and without Comorbid Depression and Anxiety: Similarities and Differences in a Clinical Sample of Children and Adolescents. European Eating Disorders Review. 2013 doi: 10.1002/erv.2234. Published Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, Gutsell JN. Running on empty: Neural signals for self-control failure. Psychological Science. 2007;18:933–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson F, Wardle J. Dietary Restraint, Body Dissatisfaction, and Psychological Distress: A Prospective Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:119–125. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N, Rogers PJ. Preoccupation, food, and failure: An investigation of cognitive performance deficits in dieters. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33:185–192. doi: 10.1002/eat.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keery H, van den Berg, Thompson JK. A test of the Tripartite Influence Model of Body Image and Eating Disturbance in adolescent girls. Body Image: An International Journal of Research. 2004;1:237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Genetic relationships between personality and eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:380–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Differential heritability of eating attitudes and behaviors in pre- versus post-pubertal twins. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33:287–292. doi: 10.1002/eat.10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotler LA, Cohen P, Davies M, Pine DS, Walsh BT. Longitudinal relationships between childhood, adolescent, and adult eating disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1434–1440. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200112000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laasko E, Hakko H, Räsänen P, Riala K The Study-70 Workgroup. Suicidality and unhealthy weight control behaviors among female underaged psychiatric inpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013;54:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Grange D, Crosby R, Locke J. Predictors and moderators of outcome in family-based treatment for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:464–470. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Crosby RD, Rathouz PJ, Leventhal BL. A randomized controlled comparison of family-based treatment and supportive psychotherapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1049–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon GR, Fulkerson JA, Perry CL, Keel PK, Klump KL. Three to four year prospective evaluation of personality and behavioral risk factors for later disordered eating in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28:181. [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Garrett A, Beenhakker J, Reiss AL. Aberrant brain activation during a response inhibition task in adolescent eating disorder subtypes. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:55–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBrayer EK, Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Demos S, Simmons J. The role of family of origin food-related experiences in bulimic symptomatology. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30:149–160. doi: 10.1002/eat.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh R, Horga G, Wang Z, Wang P, Klahr KW, Berner LA, Walsh BT, Peterson BS. An fMRI study of self-regulatory control and conflict resolution in adolescents with bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:1210–1220. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JS, Davidson RJ. Emotion as motion: asymmetries in approach and avoidant actions. Psychological Science. 2007;18:1113–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MN, Pumariega AJ. Culture and eating disorders: a historical and cross-cultural review. Psychiatry. 2001;64:93–110. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.2.93.18621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven MR, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:247–259. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Beuhring T, Resnick MD. Disordered eating among adolescents: Associations with sexual/physical abuse and other familial/psychosocial factors. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28:249–58. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<249::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Guo J, Story M, Haines J, Eisenberg M. Obesity, Disordered Eating, and Eating Disorders in a Longitudinal Study of Adolescents: How Do Dieters Fare 5 Years Later? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall MM, Larson NI, Eisenberg ME, Loth K. Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011;11:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CM, Combs JL, Smith GT. A risk model for pre-adolescent disordered eating in boys. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:696–704. doi: 10.1037/a0020358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CM, Combs JL, Zapolski TCB, Smith GT. A longitudinal transactional risk model for early eating disorder onset. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:707–718. doi: 10.1037/a0027567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Herman CP. Dieting and bingeing: A causal analysis. American Psychologist. 1985;40:193–201. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.40.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine SE, Keel PK, Burt SA, Sisk CL, Neale M, Boker S, Klump KL. Exploring the relationship between negative urgency and dysregulate eating: etiologic associations and the role of negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0031250. published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP. Dietary restraint and negative affect as mediators of body dissatisfaction and bulimic behavior in adolescent girls and boys. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:1317–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein S, Caballero B. Is Miss American an undernourished role model? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanci L, Coffey C, Olsson C, Reid S, Carlin J, Patton G. Childhood sexual abuse and eating disorders in females. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:261–267. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Combs JL, Gunn RL, Smith GT. Negative Urgency: A Personality Predictor of Externalizing Behavior Characterized by Neuroticism, Low Conscientiousness, and Disagreeableness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:160–172. doi: 10.1037/a0024948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JR, Woolson SL, Hamer RM, Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Bulik CM. Evaluating binge eating disorder in children: development of children’s binge eating disorder scale (C-BEDS) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:82–90. doi: 10.1002/eat.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JR, Smith GT, Hill KK. Validation of eating and dieting expectancy measures in two adolescent samples. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;31:461–473. doi: 10.1002/eat.10034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Jones-Gotman M, Dagher A. Feeding-induced dopamine release in dorsal striatum correlates with meal pleasantness ratings in healthy human volunteers. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007a;14:155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Simmons JR, Flory K, Annus AM, Hill KK. Thinness and eating expectancies predict subsequent binge eating and purging behavior among adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007b;116:188–197. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Williams SF, Cyders M, Kelley S. Reactive personality-environment transactions and the transition to adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:877–887. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Modeling of eating pathology and social reinforcement of the thin-ideal predict onset of bulimic symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:931–944. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. A prospective test of the dual pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:124–135. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Agras WW. Predicting the onset and remission of bulimic behaviors in adolescence: A longitudinal grouping analysis. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Mazotti L, Weibel D, Agras WS. Dissonance prevention program decreases thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, and bulimic symptoms: A preliminary experiment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000a;27:206–217. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<206::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Nemeroff C, Shaw HE. Test of the dual pathway model of bulimia nervosa: Evidence for dietary restraint and affect regulation mechanisms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1996;15:340–363. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Presnall K, Groesz L, Shaw H. Effects of a weight maintenance diet on bulimic symptoms in adolescent girls: An experimental test of the dietary restraint theory. Health Psychology. 2005;24:402–412. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D. Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: a 2 year prospective investigation. Health Psychology. 2002;21:131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw HE. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:985–993. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streigel-Moore RH, Bulik CM. Risk factors for eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62:181–198. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Silbertstein LR, Rodin J. Toward an understanding of risk factors for bulimia. American Psychologist. 1986;41:246–263. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, Rozan CA, Wolkoff LE, Columbo KM, Raciti G, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:108–118. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Theim KR, Yanovski SZ, Bassett AM, Burns NP, Ranzenhofer LM, Glasofer DR, et al. Validation of the emotional eating scale adapted for use in children and adolescents (EES-C) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:232–240. doi: 10.1002/eat.20362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:112–122. doi: 10.1002/eat.20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Andersen SL, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Navalta CP, Kim DM. The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson KM, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE. Sexual victimization and adolescent weight regulation practices: A test across three community based samples. Child Abuse Neglect. 2001;25:291–305. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice DM, Bratslavsky E, Baumeister RF. Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulsive control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:53–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman EG. Purposive behavior in animals and men. New York: Century Company; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci A, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Crosby RD, Ranzenhofer LM, Shomaker LB, Field SE, Mooreville M, Reina SA, Kozlosky M, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Latent Profile Analysis to Determine the Typology of Disinhibited Eating Behaviors in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:494–507. doi: 10.1037/a0031209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Ranson K, Schnitzler C. Adding impulsivity and thin-ideal internalization to the cognitive-behavioral model of bulimic symptoms. Presented at the Eating Disorder Research Society Annual Meeting; Pittsburgh, PA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim EH, Koerner J, Paxton S. Longitudinal predictors of restrictive eating and bulimic tendencies in three different age groups of adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Smyth J, Miltenberger M. Personality-based clusters in bulimia nervosa: differences in clinical variables and ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:340–357. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Roberts JA, Haseltine B, DeMuth G, et al. Relationship of childhood sexual abuse and eating disturbance in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1277–1283. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans MR, Coughlan E. Mood-induced eating. Interactive effects of restraint and tendency to overeat. Appetite. 2009;52:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Positive urgency predicts illegal drug use and risky sexual behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:348–354. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, Smith GT. The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment. 2010;17:116–125. doi: 10.1177/1073191109351372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]