Abstract

Refugees resettled in the United States have disproportionately high rates of psychological distress. Research has demonstrated the roles of post-migration stressors, including lack of meaningful social roles, poverty, unemployment, lack of environmental mastery, discrimination, limited English proficiency, and social isolation. We report a multi-method, within-group longitudinal pilot study involving the adaptation for African refugees of a community-based advocacy and learning intervention to address post-migration stressors. We found the intervention to be feasible, acceptable and appropriate for African refugees. Growth trajectory analysis revealed significant decreases in participants’ psychological distress and increases in quality of life, and also provided preliminary evidence of intervention mechanisms of change through the detection of mediating relationships whereby increased quality of life was mediated by increases in enculturation, English proficiency, and social support. Qualitative data helped to support and explain the quantitative data. Results demonstrate the importance of addressing the sociopolitical context of resettlement to promote the mental health of refugees and suggest a culturally-appropriate, and replicable model for doing so.

Keywords: Health disparities, mental health intervention, mixed-methods, refugees, social determinants of health

At the end of 2010, there were more than 15.4 million refugees worldwide. The United States is the largest recipient of refugees who are unable to repatriate to their country of origin or remain in their country of first asylum, resettling 71,400 such refugees in 2010 (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2011). Refugees have generally experienced exposure to traumatic events prior to flight from their homeland, including war and conflict, the death of relatives and friends, separation from family, and the loss of home, work and community. Thus, pre-migration trauma exposure puts refugees at high risk for mental illness. Moreover, researchers increasingly recognize the effects of post-migration stressors on refugee mental health (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010).

Research on the mental health of refugees from the Great Lakes Region of Africa is limited but suggests high rates of distress. Among a random sample of Burundian and Rwandan refugees in camps, 50% met criteria for serious mental health problems (de Jong, Scholte, Koeter, & Hart, 2000). Among a sample of individuals in the Democratic Republic of Congo, approximately 42% met criteria for PTSD and 27% met criteria for depression (Pham, Vinck, Kinkodi, & Weinstein, 2010).

Social Determinants of Mental Health

Researchers increasingly recognize that social inequities in education, housing, employment, health care, safety, resources, money, and power contribute significantly to health disparities. Thus to promote health and well-being for all people, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends improving daily living conditions, measuring and understanding problems of health inequity, assessing the impact of action to address these problems, and ensuring equitable distribution of money, power, and resources (CSDH, 2008).

Refugees frequently experience social inequities and health disparities that are related to limited material resources, lingering physical ailments, and loss of meaningful social roles and support, all of which may be compounded by racism, discrimination, and marginalization of their cultural practices. Although research findings are mixed on whether mental health problems decrease over time or persist for years following war-related trauma , it is clear that post-migration psychosocial factors have a powerful impact on the mental health of refugees (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010).

Recent research with Darfur refugees revealed that psychosocial stressors including lack of basic needs being met and safety concerns were more strongly related to psychological distress than war-related trauma (Rasmussen et al., 2010). A growing number of studies among diverse war-exposed populations have provided further evidence that daily stressors are related to high rates of distress (Fernando, Miller, & Berger, 2010; Miller, Omidian, Rasmussen, Yaqubi, & Daudzai, 2008). These findings are corroborated by several qualitative studies in which refugee respondents indicated that current post-migration stressors influenced their health and well-being more than past trauma (Carlsson, Mortensen, & Kastrup, 2005; Tempany, 2009). Thus, it is not surprising that research has shown that therapy and/or medications alone are not effective without also addressing the social and economic needs of refugees.

Theoretical Justification and Empirical Support for the Intervention

One of the biggest unmet needs among U.S. refugees is mental health services (de Anstiss, Ziaian, Procter, Warland, & Baghurst, 2009). This problem is multi-faceted and attributable to refugees’ higher levels of mental health problems (Porter & Haslam, 2005) and their underutilization of available mental health services because they are not always responsive to refugees’ needs and because of the stigma of seeking psychological help (Weine et al., 2000). Mental health interventions used with refugees have been primarily trauma-focused, including narrative exposure therapy (NET) (Neuner, Schauer, Klaschik, Karunakara, & Elbert, 2004), group therapy (Tucker & Price, 2007), support groups (Ley, 2006), and individual therapy (Neuner et al., 2004). Other interventions include sociotherapy (Richters, Dekker, & Scholte, 2008), psychoeducation (Yeomans, Forman, Herbert, & Yuen, 2010), and community-based interventions (Weine et al., 2004).

Research is mixed on whether these interventions accomplish their goals (Carlsson et al., 2005). NET was tested in a randomized controlled trial with African refugee adults and found to be more effective at reducing PTSD than supportive counseling or psychoeducation (Neuner et al., 2004), but it does not address the numerous post-migration stressors that have a significant impact on refugees’ depression, PTSD, and distress, and it is unlikely to be accessed by the high numbers of refugees with PTSD and depression who have not previously been exposed to Western mental health services and are reluctant to seek help from them without opportunities to build trust and address current, more pressing stressors (Weine et al., 2000). Miller and Rasmussen (2010) suggest a sequenced model of intervention for war-exposed populations that includes: rapid assessment of local daily stressors, targeted interventions to address salient daily stressors before the provision of specialized clinical services, and finally, specialized mental health interventions for those who need them that address multiple forms of distress rather than a narrow focus on PTSD symptoms only.

Some of the most salient daily stressors among refugees resettled in the United States are limited English proficiency and lack of social support. Proficiency in English has been found to be associated with mental health among refugees , including predicting lower levels of depression 10 years after resettlement (Beiser & Hou, 2001). In numerous studies, social support has been found to be a powerful predictor of (Carlsson, Mortensen, & Kastrup, 2006) or strongly related to (Birman & Tran, 2008) mental health and quality of life post-migration. Gorst-Unsworth and Goldenberg (1998) found that depression among refugees was more strongly related to poor social support than to trauma exposure. In addition, receiving social support from others who have had similar experiences has been found to be helpful for improving refugees’ mental health following resettlement (Schweitzer, Melville, Steel, & Lacherez, 2006).

Researchers have also found that the loss of valued social roles impacts the health and well-being of refugees (Goodkind, 2006; Miller, Worthington, Muzurovic, Tipping, & Goldman, 2002). Refugee adults typically experience the loss of multiple social roles. Refugees may have lost their role as parents, spouses or children through separation or death, and when they come to the U.S. and are unemployed or cannot utilize their former job skills, their valued occupational roles are lost or disrupted. For elders, roles as peacemakers, and cultural teachers are often supplanted by U.S. laws and decision-making processes that emphasize nuclear families. Valuing refugees’ cultural knowledge and experience may be important in recreating valued social roles and enabling them to maintain their cultural connections and identity. In sum, community-based interventions that are culturally appropriate, address post-migration daily stressors, build upon refugees’ cultural strengths, occur in non-stigmatizing settings, address social determinants of mental health, and include a focus on English proficiency, social support, and re-establishment of valued social roles are important.

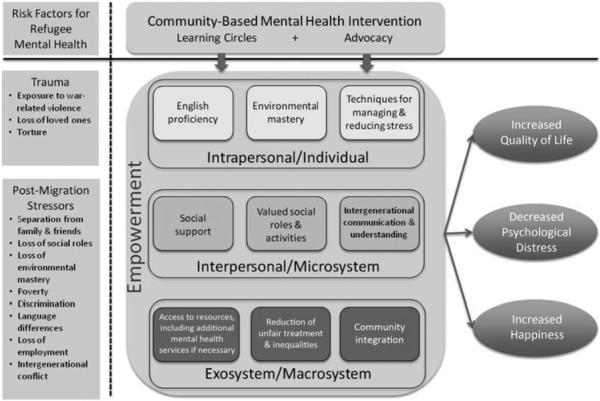

In response to these issues, the first author developed and tested a community-based intervention that sought to promote well-being and alleviate psychological distress among Hmong adult refugees. The intervention emphasized: a) increasing environmental mastery through individual and group learning opportunities; b) improving refugees’ access to resources through advocacy; c) creating meaningful social roles by valuing refugees’ culture, experiences, and knowledge; and d) reducing refugees’ social isolation. Growth curve modeling of four time points of data in that study suggested that the 6-month intervention reduced participants’ psychological distress and increased their quality of life, access to resources, English proficiency, and knowledge for the U.S. citizenship exam. Qualitative data supported these findings and elucidated the importance of the mutual learning process in improving participants’ well-being. Analyses also revealed that increased access to resources mediated increased quality of life. This mediating relationship began to clarify the processes through which the intervention was successful (Goodkind, 2005, 2006; Goodkind, Hang, & Yang, 2004). The primary objectives of the current study were to adapt and test the feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness, and preliminary outcomes of the Refugee Well-Being Project (RWP) model with refugees from several countries in Africa. See Figure 1 for a conceptual model of intervention processes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the intervention.

Method

Intervention

The study was implemented over three years (2006-2008) in a large city in the Southwestern United States. Refugee participants and undergraduates worked together for at least 6 to 8 hours per week for six months on two intervention components.

(1) Learning Circles

Learning Circles (LCs) occurred twice weekly, in two hour meetings between refugee adults and children and undergraduate students. LCs began with cultural exchange, which provided a forum for refugees and undergraduates to learn from each other through discussions aided by interpreters. Cultural exchange was facilitated by one undergraduate and one refugee each evening who worked together to decide upon and develop a topic of interest. Discussion topics included healthcare, safety issues, labor unions and worker rights, roles of men and women in the U.S., treatment of people of African descent in America, and performance arts including music, drumming, and dancing. The second component of the LCs was one-on-one learning, during which undergraduates and refugee participants worked in pairs. Refugees chose areas of learning such as English competency or completing job applications. Each refugee studied with the same student every time, fostering the development of comfort and trust. Undergraduates were also engaged in learning about the culture, experiences, and knowledge of refugees.

(2) Advocacy

The advocacy component was adapted from the Community Advocacy model, which has been successfully implemented with women and children who have experienced domestic violence (Sullivan & Bybee, 1999) and juvenile offenders (Davidson, Redner, Blakely, Mitchell, & Emshoff, 1987). Based on relationships formed in the LCs, each student worked with one or two refugee partners to engage in mutual advocacy. They spent a minimum of two to four hours each week together to mobilize community resources to address unmet needs identified by the refugee partner. Transferring advocacy skills to the refugees was emphasized so that increased access to resources would be sustained after involvement in the program ended. Example areas of advocacy included: accessing health care; finding affordable housing; and working with educators and refugee families to support student progress.

The learning and advocacy were inseparable parts of a holistic program. The RWP was centered around the LCs, which built on an important strength – the collective orientation of African participants – and provided participants opportunities to discuss their advocacy efforts, share ideas and resources, and get assistance from the interpreters. Besides emphasizing what refugees needed to learn to survive in the U.S., the program also focused on mutual learning, whereby refugees both learn from and teach Americans. Through this process, refugees’ culture, experiences, and knowledge were valued and utilized in the promotion of their well-being. For a more detailed description of the intervention, see Goodkind, Githinji, and Isakson (2011).

Implementation

Each year, the intervention was implemented by a team that included one lead facilitator (either a community psychologist or clinical psychologist) who taught and supervised the undergraduate students and co-facilitated LCs, two co-teachers/co-facilitators (former student advocates in the program) who co-taught and supervised the undergraduate students and co-facilitated LCs, and between two and four interpreters/co-facilitators (bilingual, bicultural refugees) who co-facilitated LCs, provided interpretation during LCs, and were available outside of LCs for interpretation. To build capacity among community members, we employed former refugee and undergraduate participants as facilitators and interpreters whenever possible.

Fidelity to the intervention was tracked through Weekly Progress Reports, which assessed the number of hours the advocate worked with or on behalf of their refugee partner, the number of hours of face-to-face contact the advocate had with his/her partner, the number of LCs each undergraduate and refugee attended, the areas of advocacy addressed, the number of contacts made with community resources, and the advocate's level of satisfaction with communication and accomplishments each week. In addition, each advocate kept a logbook which tracked every contact the advocate had with his/her refugee partner and community resource providers, as well as a detailed description of each activity/contact. Advocates also provided verbal descriptions of their activities during weekly supervision meetings, and the supervision meetings also involved supervisors and advocates agreeing upon weekly goals for each advocate (based upon refugee partner priorities), which were reported on during the following week. Finally, a co-facilitator conducted periodic checks with refugee participants to ensure that advocates’ reports of activities were accurate.

Adaptations and Special Considerations

Between 2002 and 2009, 232 African refugees were resettled in New Mexico, and represented a high need, underserved population. Most refugees share similar experiences such as overcoming past traumas and the challenges of adjusting to life in a new place. However, refugees’ experiences also differ widely, based upon their particular cultures, past war exposure and loss, their different social locations (e.g., gender, age, religious affiliation, sexual orientation), and how these social locations have shaped their experiences. In 2005-2006, the first and fifth authors conducted qualitative interviews with 24 adult refugees and 13 service providers, to understand the resettlement experiences of African refugees in New Mexico, assess locally salient daily stressors, and engage in a collaborative process of adapting the RWP. These participants were 19 women and 5 men from four African countries and 10 women and 3 men who worked with refugees.

The main issues identified included: extensive mental health problems; no or very limited culturally appropriate mental health services; intergenerational stressors as children learned English more quickly and strain was placed on existing family roles; lack of opportunities to build social support and bring isolated refugees together to connect with each other and with Americans; limited educational support for refugee children; domestic violence; limited resources related to housing, health insurance, jobs, transportation, and education; no established African community or assistance organizations; language barriers; limited previous education among adults; parenting challenges; and prejudice/discrimination. The strengths identified by respondents included: a sense of collective responsibility and interest in working together to form a pan-African community; high motivation to succeed in the U.S.; the use of music and dance for enjoyment, maintenance of cultural practices, and bringing people together; shared spiritual backgrounds either in Christianity or Islam; a shared common experience of being refugees and newcomers in the U.S. which created a sense of unity among people from different national backgrounds and facilitated cross-cultural interactions; and strong interest in education and acquisition of new knowledge. Typical mental health problems mentioned by African participants involved loneliness as a result of leaving family and friends in their home countries and because of the lifestyle required to survive in the United States, distress that resulted from the stressors of supporting one's family financially in the United States, and sadness because of past losses and current stressors participants faced.

The challenges and strengths identified through the qualitative interviews were used to adapt the intervention model. The main adaptation of the intervention involved adding an intergenerational component so that refugee children and adolescents would be included. The inclusion of children and adolescents enabled the intervention to address the intergenerational conflict families often experienced, which has an important impact on the well-being of adults and children. Learning Circles also provided a setting for children to hear parents talk about their cultures in a positive setting created by the interest of the students in different cultural perspectives, showing children and adolescents that Americans can have positive views of cultural practices and viewpoints other than their own. In Learning Circles, parents also learned about the challenges their children face in school. Other adaptations included emphasizing African music and dance in the LCs, adding measures of enculturation and social support, and tailoring some of the LCs to address specific unmet needs raised by the refugee families. The LCs also provided a safe space where refugee families could talk about negative racial interactions with Americans. For example, some families complained that their American neighbors threw eggs at their homes, cracked fireworks at their doors (which caused great distress because some refugees initially mistook the fireworks for gunshots), and sent false accusations to landlords that resulted in eviction threats. A final adaptation was the addition of supports that facilitated families’ participation in the LCs, including dinner, childcare for children under five (which particularly enabled mothers, to fully participate), and transportation.

Refugee Participants

Adult participants included in the analyses of the intervention were 36 individuals, comprised of 6, 12 and 18 adults from each of 3 waves. Seventeen were Burundian, one was Rwandan, 13 were from the Democratic Republic of Congo, three were Liberian, and two were Eritrean. There were 19 women and 17 men. They were an average of 34.54 years old (SD = 12.89), with a range of 18 – 71 years. Nineteen (52.8 %) were married; 11 were single, (30.6%), and 3 each were divorced or widowed (8.3%). They had an average of 3.24 children (range 0 to 10). Almost one-third (30.6%; 11 individuals) reported being employed in the two months prior to the intervention. Ninety-one percent of respondents reported being able to read their native language, and 82% reported being able to write in their native language. Twenty-eight participants (77.8%) had less than a high school education, three were high school graduates/GED holders, one held an associate's degree, and one held a bachelor's degree. Of those 28 with less than a high school education, they reported a mean of 5.93 (SD = 4.42) school years completed in Africa. They had been in the U.S. an average of 7.6 months (range 4 to 18 months). Thirty-six children, ages 5-17, also participated. See Goodkind, et al. (under review), for discussion of the impact of participation on the youth.

Undergraduate Participants

Fifty-three undergraduates were trained as paraprofessionals to implement the intervention. Twenty-five of them (17 women and 8 men) worked directly with adult refugees. They were predominately non-Hispanic white (52%) and Latina/o (32%), and ranged in age from 20 to 51; all were juniors and seniors in college except for one sophomore. Students made a two-semester commitment to the project, earned eight course credits, and received 48 hours of training over a period of 12 weeks. The training was based on a manualized curriculum (Goodkind, 2000) adapted from the Advocate Training Manual of the Community Advocacy Project (Sullivan, 1998). Training continued during the first month of the Learning Circles. For the final five months of the intervention, supervision replaced training. Students met weekly with instructors, in small groups (6-8 students), to review the progress of their advocacy and discuss their experiences in the Learning Circles.

Research Design

This pilot study examined intervention processes and outcomes using a mixed methods, within-group longitudinal design with four time points at 3-month intervals (pre-intervention, midpoint, immediately post-intervention, and three months post-intervention). The longitudinal design of the study and analytic plan were chosen in an attempt to partially compensate for the quasi-experimental nature of the study, in which it was not possible to include a control group within a small refugee community in which withholding the intervention from some members would not be culturally acceptable and in which contamination effects were likely. The collection of multiple data points across time allows for an exploration of individual- and group-level trajectories, potential exploration of individual characteristics that predict the form and/or amount of change, and examination of mechanisms or processes of change as delineated by our conceptual model of the intervention. Thus the aims of the study were to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness of the intervention for African refugees and to test five hypotheses, as by guided by our conceptual model (see Figure 1):

Hypothesis 1: Participants’ psychological distress will decrease over time during and following the intervention.

Hypothesis 2: Participants’ happiness will increase over time during and following the intervention.

Hypothesis 3: Participants’ quality of life will increase over time during and following the intervention.

Hypothesis 4: Improved psychological well-being (decreased distress, increased happiness) will be mediated by increases in access to resources, enculturation, English proficiency, and social support.

Hypothesis 5: Improved quality of life will be mediated by increases in access to resources, enculturation, English proficiency, and social support.

We also examined variability in participants’ baseline status and trajectories on all variables to determine whether participants had similar levels of each variable prior to the intervention and whether they followed similar patterns of change over time. When variance was significant, we attempted to find individual-level variables that could account for these differences.

Intervention Interview Procedure

Each participant was interviewed four times, at their home, by trained bilingual interviewers or by English-only speakers with the assistance of a bilingual interpreter. All interviews were conducted in a language in which the participants were fluent, most often their native language. Whenever possible, participants chose the language used in the interview – Amharic (2), English (3), French (5), Kirundi (6), or Kiswahili (20). Due to financial and literacy resource constraints, it was not possible to create written translations of the interview for each language. Instead, interviewers and interpreters participated in a series of meetings with the first author in which the intended meaning of each question was discussed, and the appropriate translation of each question was agreed upon. Interviewers and interpreters also received in-depth training on interviewing and interpretation skills and techniques. The qualitative portions of interviews consisted of an interview guide with open-ended interview questions designed to elicit interviewees’ resettlement experiences, perspectives on the benefits and challenges of living in the United States, the level of comfort and participation in the community, as well as experiences and accomplishments during the program. The interviews lasted an average of 95.59 minutes (SD = 40.37) and adult participants were paid $15 for each interview.

Measures

Pre-existing scales, most of which had been used in studies with refugee populations, were used. However, all measures were carefully adapted for this study through a multi-step process that involved piloting the interview questions with at least one participant from each nationality and/or language group and discussing concerns that emerged regarding particular questions that were either difficult to understand and/or which did not make sense culturally. Based upon this piloting process, we eliminated a measure of self-esteem and re-worded several items from other measures.

Psychological well-being was measured using modified versions of the distress and happiness subscales of Rumbaut's (1985) Psychological Well-Being Scale. Each subscale has six items measured on a 4-point scale. One item from the distress scale was removed based on its low inter-item correlation with the other items. Average Cronbach's α's for both scales were .64.

Quality of life was measured by the Satisfaction with Life Areas scale (Ossorio, 1979), which has been used in many studies with refugees and immigrants (Goodkind, 2005; Rumbaut, 1991). Respondents rated their satisfaction with nine specific areas of everyday life (e.g., work, money, home life, neighborhood, health, leisure) on a 7-point scale ranging from very dissatisfied to very satisfied (average Cronbach's α = .81). A second measure of quality of life (Life Satisfaction Index A, Liang, 1984), which included 11 global questions about participants’ life satisfaction rated on a 6-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, was also administered.

Access to resources was measured by adapted versions of the Satisfaction with Resources scale (Sullivan, Tan, Basta, & Rumptz, 1992) and the Difficulty Obtaining Resources scale (Sullivan & Bybee, 1999). For the first scale, participants were asked to rate, on a 7-point scale, how satisfied they were with the resources they had in 12 specific domains (education, health care, housing, employment, finances, transportation, legal issues, childcare, children's health care, children's school issues, citizenship/green card issues, other material goods and services). The latter scale asked participants to rate, on a 4-point scale, how difficult it had been or would be in the future to obtain resources they needed in the 12 specific life domains. Difficulty accessing resources was computed as the mean difficulty over all the resources respondents reported accessing; if they were not accessing a resource, their response was taken as their rating of how difficult they thought accessing that resource would be in the future. Average Cronbach's α's for these scales were .79 and .68, respectively.

English proficiency was measured by two scales. The first was the Basic English Skills Test (BEST), a standardized measure of English as a Second Language ability, designed to assess English communication, fluency, and listening comprehension for adults at the survival and pre-employment skills level. It has an established internal consistency of .91 and has been used widely with refugees (Kenyon & Stansfield, 1989). In this study, Cronbach's α ranged from .80 to .83. Perceived English proficiency was measured by Rumbaut's (1989) four item scale, which asks participants to rate separately how well they can speak, understand, read, and write English on a scale from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“Like a native”). Cronbach's α ranged from .60 to .99.

Enculturation, which indicates the degree to which someone identifies with their traditional culture and engages in traditional cultural practices was measured with a modified version of the cultural identity component of the Whitbeck Enculturation Scale (Whitbeck, Chen, Hoyt, & Adams, 2004). The 3-item scale assesses the degree to which participants and their immediate family live by and participate in their traditional culture (e.g., Burundi or Liberian). Cronbach's α's ranged from .66 to .82. Research on acculturation has generally found that immigrants who maintain strong connections with their own culture while also establishing connections with the culture of the society in which they resettle tend to have better mental health outcomes (Berry, 1986). In addition, one of the goals of the RWP was to reinforce refugee participants’ cultural identities and strengths, which could also contribute to creating new valued social roles. Thus, we thought it was important to measure participants’ connections with their own culture. Social support was measured using the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988), which included questions about family and friends’ support in multiple domains. Cronbach's α's ranged from .82 to .94.

Quantitative Analyses

To test our hypotheses, growth curve modeling was implemented using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Byrk, 2002). Analysis proceeded sequentially beginning with a baseline ‘intercept-only’ model, then testing a fully parameterized model, and then testing further iterations as warranted (see Goodkind, LaNoue, Lee, Freeland, & Freund, 2012 for detailed description of analytic method).When this iterative process identified that the best fitting model included significant random effects corresponding to the significant fixed effects, i.e. that there was significant variability in intercepts or slopes, or both, we attempted to model it using level-2 predictors. The rationale for the choice of the level-2 predictors sex, age, and intervention hours as potential moderators was two-fold: 1) identifying relevant individual difference variables (age and sex) that predict response to the intervention would be valuable for future study planning, and 2) finding that intervention dosage predicts differential change strengthens the inference of treatment effects. These predictors were tested one at a time at level-2 (rather than testing interactive effects) owing to our relatively limited statistical power in this sample. All models were estimated with maximum likelihood (ML) estimation and were centered at baseline to allow for interpretation of intercept coefficients as initial values. Calculating effect sizes for multilevel models is complex; because our focus was the effect of the intervention over time, we chose to report the percentage of variance explained (PVE) by the addition of time to each model, sometimes referred to as pseudo-R2 (Singer & Willett, 2003). This is calculated by comparing the PVE of the best fit Level 1 model to the Level 1 intercept-only model.

All variables were screened for distributional assumptions; the BEST was subjected to a square root transformation as a result of this screening. Tests of model assumptions proceeded simultaneously with model fitting; in the case that a fixed-effects only model (either linear or linear and quadratic) was the best fit, this model's assumptions were evaluated by inspection of a Q-Q plot of the residuals. When model-fitting indicated significant random effects, an additional test of homogeneity of level-1 variance across level-2 units was run in HLM.

Finally, a series of analyses were conducted to evaluate mediational hypotheses relative to the three significant outcomes of global and specific quality of life and psychological distress. In particular, potential mediation of the relationships between intervention participation and these outcomes by the putative process variables of 1) enculturation, 2) English proficiency, and 3) social support was evaluated. The mediational analyses were conducted using a ‘product of coefficients’ approach (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002), applied to multi-level growth curve models. This method was used instead of a ‘causal steps’ (e.g., Baron & Kenny, 1986) approach for reasons of increased statistical power. However, conventional notation from Baron and Kenny is used here to indicate effects estimated. This approach calculates two direct effects: a (the effect of the time predictor on the mediator) and c (the effect of the time predictor on the outcome). Two indirect effects are also calculated: b (the effect of the mediator on the outcome, when it is included in a model that controls for the effect of the time predictor variable on the mediator), and ab (the product of a and b). We used a bootstrap method of calculating confidence intervals (CIs) for the ab coefficient, rather than relying on a distributional assumption about the standard errors of this effect. This method is described in Preacher and Hayes (2008) and was calculated using an R macro on their website (http://quantpsy.org). Based on our directional hypotheses, we examined 95% and 90% CIs; when the CI's were found to include zero, statistical evidence of mediation was rejected.

Qualitative Analyses

Qualitative interviews were transcribed, checked for accuracy, and imported into NVivo 8. There were 158 interviews or qualitative portions of interviews analyzed as part of this study, including preliminary interviews, open-ended questions asked at the beginning and end of the intervention interviews, and paired student-partner interviews. The first level of analysis involved: 1) coding the content of each interview according to question so that each answer could be examined across the data, and 2) text-based coding, where team members read the text and marked recurrent themes or statements. Thus, intervention specific research questions were included for analysis (for example, themes such as “Well-being and Health”), as well as themes that emerged from the data (for instance, we asked no direct questions about gender roles, but created a thematic category “Gender Roles” to capture participants’ discussion of different or changing gender roles as a result of resettlement in the U.S.). As the themes emerged, the coders on the research team met to standardize and define them, to agree on a structural framework to elucidate the relationship of themes to each other, and to determine how they should be applied to the data. All of the interviews were then coded using the same framework. This process constituted the second level of analysis in which text was categorized into thematic categories. The third level involved querying the data to isolate text coded at both dominant themes as well as the qualitative nodes that matched the areas we measured quantitatively and then analyzing the content for patterns and meaning according to various categories (Corbin & Strauss, 1990; Richards, 2005). The integration of the qualitative and quantitative data was achieved through: 1) ensuring that quantitative research questions were included in the qualitative coding structure, and 2) during the third phase, we examined each of our hypothesized outcomes and the ways in which qualitative data for each converged, contradicted, or provided illuminating detail with respect to individual, familial or community experiences, meanings or perspectives. Memos were created to analyze the predominant subthemes, patterns and meanings for each node or theme. All authors, excluding the 3rd and 5th, participated in the coding process.

Results

The Intervention Process

In order to explore feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness of the intervention, we tracked recruitment, retention, and attendance of participants and included interview questions at the last three time points that assessed participants’ experiences, engagement, and degree of satisfaction with the intervention. We also tracked feasibility of the interview process and intervention fidelity. Participant recruitment and retention rates across the 9 months were very high. We invited all African refugee adults who had been resettled in the past two years to participate in the study. Of the 41 eligible adults, all agreed to complete pre-interviews and 36 completed the intervention (88%). Five adults decided not to participate in the program because of time constraints or scheduling conflicts. No adult participants dropped out of the intervention once it began. Of the 144 potential interviews (4 interviews for each of 36 participants), 136 were completed (94%). During the post-interviews, participants were also asked to rate, on a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from very dissatisfied (0) to very satisfied (6), how satisfied they were overall with the project, with the LCs, and with their advocates. Participants’ satisfaction was high, with a mean satisfaction with the overall project of 4.8, mean LC satisfaction of 4.9, and mean satisfaction with their advocate of 5.4.

In addition, all 36 participants received a meaningful intervention as measured by total intervention hours and Learning Circle (LC) attendance. The average number of hours each undergraduate student worked with and on behalf of their adult refugee partner, including LC and advocacy time, was 158 hours (SD = 28.94, range 125 to 237). Undergraduates had an average of 105 hours of face-to-face contact with their adult partner(s) (SD = 27.91, range 40 to 176). Advocacy efforts included the following areas (% who worked on this area): education (100%), employment (94%), health care (89%), obtaining material goods and services (81%), transportation (72%), legal issues (70%), financial issues (69%), housing (67%), social support (67%), participants’ children (excluding childcare) (50%), U.S. immigration or citizenship issues (44%), and childcare (28%). LC attendance was quite high. Of the 39 LCs that occurred each year, 86% of African adult participants attended more than half and 61% attended more than three-fourths.. The average number attended was 29 (range 11-39). Absences were mostly due to conflicts with work schedules, ESL classes, pregnancy, or other health concerns.

Outcomes

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics for all outcome variables are shown in Table 1. Means and standard deviations reported are for all of the participants present at each time point for each measure. Summary of the quantitative results (significant patterns of change and mediating and moderating effects detected) are described in Table 2, and parameters of growth curve models for all significant outcomes are provided in Table 3. [Tables 1, 2, and 3 About Here]

Table 1.

Means (Standard Deviations) for All Outcome Measures at Each Time Point

| Scale | Pre Intervention | Mid Intervention | Post Intervention | 3-month Follow-Up | Possible Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Well-Being - Distress | 6.52 (2.82) | 5.60 (2.30) | 5.40 (2.75) | 5.41 (2.84) | 0-12 |

| Psychological Well-Being - Happiness | 14.78 (4.28) | 14.80 (2.72) | 13.55 (4.13) | 14.30 (3.48) | 0-21 |

| Quality of Life (Global) | 42.11 (5.38) | 42.68 (6.16) | 44.69 (6.90) | 45.22 (6.50) | 11-66 |

| Quality of Life | 33.31 (11.11) | 35.55 (10.70) | 35.90 (9.83) | 38.20 (8.45) | 0-54 |

| Satisfaction with Resources | 3.22 (1.08) | 3.31 (1.40) | 3.49 (1.35) | 3.56 (1.00) | 0-6 |

| Difficulty Accessing Resources | 3.38 (2.56) | 3.90 (2.78) | 3.86 (2.53) | 3.80 (2.53) | 1-4 |

| Total Resources Accessed | 7.44 (3.70) | 9.72 (3.58) | 9.69 (2.47) | 9.55 (3.34) | 1-12 |

| Enculturation | 4.72 (2.89) | 6.74 (2.08) | 6.71 (2.20) | 6.21 (2.29) | 0-9 |

| English Proficiency | 27.69 (27.94) | 36.68 (28.33) | 45.59 (29.37) | 51.89 (25.75) | 0-83 |

| Perceived English Proficiency | 2.96 (2.46) | 4.14 (2.65) | 4.48 (1.87) | 4.30 (1.74) | 0-12 |

| Social Support | 46.31 (13.98) | 51.87 (13.98) | 54.46 (16.62) | 51.95 (12.42) | 0-72 |

Note. Tabled values are descriptive for all participants present at each time point.

Table 2.

Summary of Results

| Hypothesis | Was hypothesis supported? | Did participants have similar baseline scores? | Did participants follow similar pattern of change? | Percent Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. Decreased Psychological Distress | Yes, significant linear decrease (t(35) = 15.29, p < .001) | No, women had higher distress than men at baseline(t(34) = 2.07, p < .05; β01 = 1.10, 95% CI=.001, 2.20) | Yes | 2.4% |

| H2. Increased Happiness | No significant effects | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| H3. Increased Quality of Life | Yes, significant linear increase in global quality of life (t(120) = 2.30, p < .05) and marginally significant linear increase in satisfaction with specific life domains (t(128) = 1.90, p = .06) | No, but variance in baselines could not be explained by age or sex | Yes | Global 4.5% Specific 18.5% |

| H4 & H5. Mediation of psychological well-being & quality of life | Partially, 5 of 9 potential effects (based on significant effects described below): | |||

| • increased social support mediated increased specific and global QOL (90% CI of ab = .11, 2.27 and .001, .910, respectively) | ||||

| • increased English proficiency mediated increased specific and global QOL (90% CI of ab = .13, 1.53 and .04, 1.16, respectively) | ||||

| • increased enculturation mediated increased specific QOL (90% CI of ab = .25, 7.12) | ||||

| Satisfaction with Resources | No significant effects | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Difficulty Accessing Resources | No significant effects | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total Resources Accessed | Yes, significant linear increase in number of resource domains accessed (t(35) = 3.83, p < .01) with significant leveling off (quadratic fixed effect t(141) = 3.11, p < .01) after intervention ended | No, but variance in baselines could not be explained by age or sex | Yes | N/A |

| Enculturation | Yes, significant linear increase (t(30) = 3.80, p < .01) that leveled off (quadratic fixed effect t(30) = 3.47, p < .01) after intervention ended | No, but variance in baseline could not be explained by age or sex | Yes | 8.9% |

| English Proficiency | Yes, significant linear increase (t(29) = 5.8, p < .001) | No, women had lower baseline English proficiency than men (t(28) = 2.43, p < .05; β01 = 1.98, 95% CI=0.30, 3.66) | No, but variance could not be explained | 4.6% |

| Perceived English Proficiency | Yes, significant linear increase (t(35) = 3.14, p < .01) that attenuated (quadratic effect t(35) = 2.45, p < .05) after intervention ended | No, women had lower baseline perceived English proficiency than men (t(34) = 3.89, p < .01; β01 = 1.92, 95% CI=.91, 2.92) | No, but variance could not be explained | 8.6% |

| Social Support | Yes, significant linear increase (t(35) = 2.85, p < .01) that attenuated (quadratic effect t(130) = 2.19, p < .05) after intervention ended | No, but variance in baseline could not be explained by age or sex | No, but variance could not be explained | 19.1% |

Table 3.

Parameters of Growth Curve Models for All Significant Outcome Variables (N = 36 individuals, 136 observations across 4 time points)

| Parameter | Psychological Distress | Quality of Life Global | Quality of Life Specific | Enculturation | English Proficiency | Perceived English Proficiency | Social Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (fixed) effects | |||||||

| Intercept – initial level (β00) | 6.21 *** (5.39,7.04) | 42.01 *** (40.0, 44.0) | 34.14 *** (30.9, 37.4) | 4.73 *** (3.68, 5.78) | 4.55 *** (3.51, 5.59) | 2.85 *** (1.98, 3.69) | 45.96 *** (40.7, 51.3) |

| Linear change (β10) | −.11 * (−.02, .19) | .36 * (.05, .68) | .41 ~ (−.02, .83) | .82 ** (.38, 1.27) | .25 *** (.16, .34) | .50 ** (.20, .80) | 2.28 ** (.65, 3.91) |

| Quadratic change (β20) | NE | NE | NE | −.08 ** (−.03, −.12) | −.04 * (−.01, −.06) | −.18 * (−.02, −.34) | |

| Random variance estimates | |||||||

| Intercept variance (τ00) | 1.51 *** | 5.91 ** | 38.32 *** | 4.14 *** | 7.55 *** | 4.05 *** | 163.2 *** |

| Linear change variance (τ10) | NE | NE | NE | .36 NS | .05 *** | .46 *** | 1.32 ** |

| Quadratic change var. (τ20) | NE | NE | NE | .003 NS | NE | .004 *** | NE |

Note.

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

p =.06

NE = not estimated in ‘best fit’ model; NS = estimated but non-significant in ‘best fit’ model. Outcome variable of English proficiency was subjected to a square root transformation prior to analyses to address a significant positive skew.

Qualitative

Integrating the qualitative and quantitative components of the interviews provided important opportunities to understand participants’ experiences in the intervention. For example, participants described many outcomes of the intervention that we did not assess quantitatively, including: acquisition of new skills and knowledge; increased environmental mastery, self-sufficiency, and self-confidence; setting future goals; positive impacts on their children; valuing of their experience, knowledge, and dignity by others; and decreased feelings of discrimination from and fear of White people. Finally, analysis of the qualitative data served a complementary function to the quantitative data as it provided important detail, or thick description (Geertz, 1973), which allowed a deeper understanding of the emic experience and meaning of resettlement, well-being, and how participation in the intervention impacted the everyday life of participants.

The qualitative data supported the importance of English-language learning in the intervention and the precise ways increased fluency impacted refugees’ lives. All refugee participants discussed the importance of the intervention in helping them learn or improve their English. A 21 year-old male from DRC described this in an interview:

I am very grateful for all the advice that you have given me, the help with the language, and . . . also skills or language that I needed to use at work. Sometimes I wouldn't have a translator... but then I'd remember something that you'd told me in conversation concerning work and then they'd ask me a question and I'd remember how to answer it. And that was really helpful for me. Even the people at work are really amazed at how quickly I've been able to catch up with English.

Refugees articulated how improved fluency helped them communicate more with English-speakers, thus reducing feelings of difference and of being outsiders to the community. Refugees recognized that English skills went hand-in-hand with increases in self-efficacy. Students also emphasized the primacy of learning English in terms of the expectations of the refugees and its importance for refugee integration, community participation and well-being. Moreover, students directly linked increased English proficiency with increased self-confidence and self-efficacy.

Even though our quantitative findings did not support the hypothesized increase in access to resources, the qualitative data provided numerous examples of increased resource access that occurred throughout the program: housing, education, transportation, identity cards, learning how to drive, computer skills, health care, employment, and accessing food and food stamps. The focus on students transferring skills to their partners could be clearly seen in the qualitative data as multiple interviewees described their understanding of this idea and the challenge of putting it into practice. A 43-year-old man from Burundi told his student partner in an interview:

You took me and you helped me find an ID. I would have had no idea how to do it on my own. Now I have an ID, and I know that it's very important. It's one other example of something that I would have had no clue how to do if it weren't for you. Even the kids, they didn't have IDs, and now that I know how to do it, I was able to take the kids, and now they have IDs also. Everything that I've done in America, it's because you showed me first.

This quote demonstrates how the advocacy process worked for this participant. He described how his understanding of the importance of proper identification in the U.S., coupled with his newfound knowledge of the process, worked to spur him to obtain the same resources, on his own, for his children. Another idea that emerged was the importance of human interaction and the development of an emotional bond in terms of motivating action on behalf of others.

In the qualitative data on social support, we identified three ways that refugee participants and students articulated the impact of developing relationships with one another and the resulting increases in social support. The first was the emotional support refugees received from students. The second aspect of social support was the process of working toward self-efficacy and independence of the refugees. Third, both refugees and students spoke of the strong relationships they developed and would like to continue after the program. Qualitative data also revealed that the RWP increased refugees’ social support and social networks with other refugees and Americans outside of the intervention. For example, a Burundian woman explained her increased ability to obtain social support from other Americans:

This project has helped me to understand that once you get to know people, talk to them, understand them, and work with them, that they are very willing to understand your situation. It's not a matter of pride. [In fact,] they are more than willing to help you, and this project has made me be open-minded to interact with people, not to fear them just because we don't speak the same language, just because we don't look alike. There's that human aspect to it that despite our differences and culture, our differences in language, our differences in appearance, that we kind of share the same thing.

Examination of the qualitative data in relation participants’ enculturation allowed us to elaborate on the meaning of expressing and maintaining African culture in the U.S. The pedagogical underpinnings of the program emphasize mutual learning and cultural exchange, rather than privileging a one-way indoctrination into U.S. cultural and societal norms. The RWP built on these theoretical perspectives to provide a framework in which both African and American cultures were valued. Learning Circles were a place where students and refugees participated in learning aspects of African culture, as well as learning aspects of U.S. culture and society imperative to social and economic participation and improved health and well-being. Thus, African refugees, as well as students, received the message that diverse African cultural perspectives and practices were a strength that could facilitate integration into U.S. society. This also contributed to creating new valued social roles as experts and teachers for African participants. As a 41-year old woman from Burundi told her student partner in an interview:

The most important thing I've taught you I think is Swahili language. I'm proud when you're able to say a few words...We were learning from you English, and we were teaching you Swahili. That was my view that I teach you a little Swahili and I'm proud.

The qualitative data that revealed how quality of life and psychological well-being were impacted by participation in the program were found in a number of interrelated themes, including well-being, advocacy and social support. For example, a 42-year old man from Burundi explained:

For a long time in my life, I lived like a refugee. This project is really good in terms of helping me with mental health. If I was just by myself, with just the family, I would be thinking about the terrible things that happened in the past. But when I come from work and get to meet with him [student advocate] and the other people, I am really engaged in the present, and I don't dwell on the horrible things that happened in the past.

Many factors impact health and well-being. Participants attributed living well to many things: eating well, sleeping well, having clothes and shoes, and safety. In addition, having student partners for companionship and to help advocate for them also positively affected their well-being. If a need was met, it often had a domino effect on many different aspects of the refugee's life. For example, one participant needed glasses (physical health), her partner helped obtain the glasses (student-partner relationship/advocacy), in response the participant felt happy (mental health), and as a result was able to read (empowerment). Another important component of mental health, particularly for people who have been traumatized, is reestablishment of their value and dignity (Danieli, 1998). This aspect of psychological well-being was described by many participants. For example, a 47-year old woman from Burundi said:

When we were in Tanzania, we were refugees there; we were treated like we were second class citizens, that we wouldn't share the same utensils as our supervisors or the people who were running the camp so we were treated as if we were not equal to the Tanzanian citizens. But we came here and we realized we were treated like human beings. For example...the students would come to the house and sit together and eat together and treat us like equals and so we see with time we are going to feel really at home here. ...and so I feel that humanity and dignity is really being noticed and upheld in America and people see us as people, yeah, and it's really wonderful.

In sum, African participants’ descriptions of their experiences in and effects of the intervention supported and elaborated upon the quantitative findings.

Discussion

This study replicated findings from the original Refugee Well-being Project (RWP) model, first implemented with Hmong refugee adults (Goodkind, 2005). Specifically, participants in both studies experienced significant increases in English proficiency and quality of life and significant decreases in psychological distress. Although quantitative findings related to increased access to resources were not replicated in the current study, understanding how improved well-being might be facilitated by the intervention was extended by our findings that increases in enculturation, English proficiency, and social support mediated increased quality of life over time. Overall, the growth trajectory models and qualitative data suggest that the intervention had positive impacts on African participants’ mental health and well-being. Thus, the current study provides additional preliminary evidence that addressing psychosocial stressors through the creation of space for mutual learning, development of reciprocal relationships, and valuing of refugees’ strengths, concurrent with the mobilization of needed resources may be important in improving quality of life and psychological well-being. Furthermore, our positive findings regarding the feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness of the intervention suggest that the RWP model can be adapted for ethnically and linguistically diverse refugees who resettle in different parts of the United States.

The pattern of quantitative findings suggests that the intervention conceptual model may accurately reflect some of the mechanisms through which refugee well-being can be facilitated and promoted. Increased English proficiency, enculturation, and social support contributed to increases in quality of life over time. Although not explained by the hypothesized mediating variables, participants’ psychological distress significantly decreased over time as well. It is possible that with a larger sample size, additional mediating effects could have been observed. Although it might be expected that some of these positive outcomes would naturally increase over time as refugees adjust to living in the United States, many studies have found that refugees’ psychological distress and low quality of life persist over long periods of time (at least several years and sometimes longer) after resettlement (Hauff & Vaglum, 1995). The refugees in this study had all been in the United States fewer than 18 months. In addition, the leveling off of the increases in social support and enculturation after the end of the intervention provides further evidence that these changes (and the subsequent increases in quality of life) were related to the intervention itself. In terms of English proficiency, most African adults in the study had less than a high school education and had experienced numerous traumas, both of which have been shown to contribute to difficulties in learning a new language (Isserlis, 2009). The one-on-one learning structure of the RWP, in which a trusting relationship is developed, may be an effective mechanism for overcoming these challenges. Given the relationship between English proficiency and psychological well-being among refugees in the United States (Chung, Bemak, & Kagawa-Singer, 1998), these findings are important.

There were two quantitative outcomes on which the intervention did not have a significant effect: access to resources and happiness. In contrast to our qualitative findings, which did suggest that participants’ experienced increased access to resources, it may be that our quantitative assessment of satisfaction with and difficulty accessing resources was impacted by the fact that our measures of these constructs depended on the number of resource domains on which the participant worked in the past three months. As noted in Table 2, we found that the number of resource domains focused on by participants significantly increased throughout the intervention and then leveled off, which suggests that implementation of resource advocacy during the intervention was occurring. However, since participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with and difficulty accessing resources on each domain of resources on which they worked, their pre-, mid-, post-, and follow-up assessments were likely shaped by the challenges they faced as they engaged in increasingly intense efforts to mobilize needed resources. The lack of change observed in participants’ happiness was consistent with our findings from the original RWP study with Hmong refugees. It may be that the RWP does not impact participants’ happiness, that refugees’ happiness grows only after a much longer time period in the United States, or that there are limitations with the happiness scale we used.

Our mixed-methods approach was also particularly valuable in delineating mechanisms through which the intervention seemed to be effective. For instance, qualitative data highlighted the role of the intervention in helping refugee participants feel safe and welcome in the U.S., building trust, reducing perceived racism, and thus enabling refugees to begin to heal and focus on their new lives. Qualitative data also revealed that the intervention contributed to positive goals for the future among refugee participants, which has been found to help refugees overcome psychological challenges (Khawaja, White, Schweitzer, & Greenslade, 2008). Also contributing to the success of the intervention was providing needed access to resources that refugees are often lacking within the intervention itself, including transportation to and from Learning Circles, dinner for participants, and child care. Addressing these needs likely contributed to the high levels of participation and completion in the study.

It is also important to note the limitations of our study. One of the primary limitations involved issues of measurement. Based on our concerns regarding the cultural appropriateness of existing measures of PTSD and depression, we chose to use a measure of psychological well-being (distress and happiness) that had been widely used with immigrants and refugees. However, we remain concerned that our conceptualization and measurement of psychological distress may not have been culturally appropriate. Specifying and measuring culturally specific idioms of distress will broaden our understanding of the impact of violence and trauma, not only on individuals but also on social interactions and patterns among families and communities. These interdependent effects have a significant impact on individuals’ well-being and should be a focus of interventions for refugees, such as the RWP (Miller, Kulkarni, & Kushner, 2006). Thus, to accurately assess the intervention's ability to reduce the burden of mental illness on refugee participants, it is necessary to measure psychological distress in multiple ways. A second limitation was our small sample size, which may have limited our power to detect significant change. Effect size estimates for study planning and sample size were based upon the sample size calculation done in the first RWP study (Goodkind, 2005), which suggested adequate power to detect direct effects with our sample size. However, it is possible that the effect sizes were overestimated and that therefore this study was underpowered. In addition, our power to detect moderating and mediating relationships was likely low. Finally, our study is limited by its quasi-experimental design. Without a control group, we cannot definitively conclude that the changes we observed were due to the intervention. It is possible that some of these effects would be observed over time among newly arrived refugees. However, research with nonclinical populations of refugees suggests that psychological distress persists at least several years after resettlement (Hauff & Vaglum, 1995). Furthermore, the leveling off of several observed effects (increased enculturation and social support) strengthens our ability to conclude that these changes and the increased quality of life they mediated were related to the intervention. Finally, participants’ rich descriptions of the ways in which their participation in the intervention improved their well-being also provide important evidence.

Implications for Psychological Service Delivery

The RWP brought together recently arrived refugees and undergraduates to engage in mutual learning, cultural exchange and the mobilization of community resources to promote the integration and well-being of newcomers. Through working together, refugee and undergraduate partners sought to transform their communities to be more responsive, supportive, and accepting of refugees. RWP was developed to respond to the mental health needs of refugees in a culturally appropriate, non-stigmatizing setting. However, our findings have important implications for psychological service delivery in both specialty and non-specialty settings. First, the results of this study suggest that mental health services for refugees will be most successful if they include some focus on the social determinants of health/mental health. This is consistent with the growing recognition among primary care providers that their clinics/practices should attend to these social determinants (Garg, Jack, & Zuckerman, 2013). Towards this end, the RWP has been implemented by a torture treatment center in Chicago. This effort involved the torture treatment center partnering with a nearby university, through which students were recruited and involved. Although the RWP model might appear to lend itself to implementation with community volunteers, our experience suggests that one of the key elements for the success of the program is the level of engagement and commitment by the students, which is maintained through the course structure and requirements. Thus, clinic-university partnerships may be optimal for implementing this type of program.

Given many of the new provisions of the Affordable Care Act, it is likely that clinics could be reimbursed for providing the RWP or similar programs. This funding could support the time required by one or two staff to teach and supervise the students and the LCs. All frontline staff and providers at a clinic could be trained to identify refugees who they thought would be appropriate for the group. A detailed handbook is available to clinics who are interested in implementing the RWP. Although certain aspects of the program may appear to be resource-intensive, the RWP actually provides in-depth intervention at a low cost. Participants receive more than 100 hours of intervention each. Intervention time costs include ongoing training and weekly supervision for undergraduate providers. However, one of the innovative aspects of the RWP model is that it is supported by university resources and it connects universities, clinics, and communities in a sustainable way. For example, student advocates are not paid for their time because they receive course credit. In addition, training and weekly supervision are structured as part of a course so any university with a faculty member willing to offer this course and a department willing to allow the faculty member to teach it as part of their teaching load, can provide no cost intervention, training, and supervision.

The RWP model is designed to ensure that refugees’ most immediate needs are met— English-language learning, job acquisition—while at the same time fostering support within the refugee community, as well as between refugee newcomers and other Americans. This focus on increased social support and community connectedness is particularly important given that refugee adults who participated in the formative stage of this study most frequently mentioned their lack of friends and time spent with others as causes of their distress. Through the promotion and development of relationships between newcomers and students, RWP increased refugees’ social support and trust of Americans and also served to decrease stereotypes and promote understanding of diverse cultures and histories, thus providing the basis for increased integration of refugees into U.S. society.

Thus, the findings from our study support the importance of recognizing and addressing the sociopolitical context of resettlement. However, these experiences are not unique to refugees; they are also relevant to the lives of many other marginalized and traumatized populations, including other immigrants, veterans, American Indians/Alaska Natives, African Americans, Latino/as, and persons with serious mental illnesses. Thus, interventions that promote social justice by addressing social inequities in a holistic, strengths-based way have the potential to reduce the burden of mental illness experienced by numerous populations, in particular those who face the largest mental health disparities.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the University of New Mexico School of Medicine Research Allocation Committee, University of New Mexico Department of Pediatrics Research Committee, University of New Mexico Signature Program in Child Health Research, St. Joseph Community Health Services, New Mexico Department of Health Office of School & Adolescent Health, and Con Alma Foundation, and involved partnership with the University of New Mexico Departments of Psychology, Anthropology, Africana Studies, and Research Service Learning Program. We wish to thank all of the refugee family and undergraduate student participants; as well as acknowledgement the invaluable contributions of Chao Sio, Brandon Baca, Michaela Brown, Julissa de la Torre, Tricia Gunther, Elisa Gutierrez, Madelyn Ikeda, Saher Lalani, Rosalinda Olivas, Rose Afandi, Corinna Hansen, Amelia Hays, Adeline Kisanga, Christy Mello, Jessica Meyer, Cyntia Mfurakazi, Eric Ndaheba, Martin Ndayisenga, Patrik Nkouaga, Liana Serna, Angela Speakman, Doris Benjamin, Aimee Bustos, Carmen Gonzalez, Katrice Grant, Dee Ivy, Irene Mwamikazi, Ngerina Nyankundwakazi, Janet Sairs, Babylove Tieh, Juliana Vadnais, Kim Vadnais, and Layla Wall.

Contributor Information

Jessica R. Goodkind, Department of Sociology, University of New Mexico

Julia M. Hess, Department of Pediatrics, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center

Brian Isakson, Department of Psychiatry, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center.

Marianna LaNoue, Department of Family & Community Medicine, Jefferson Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University.

Ann Githinji, Department of Anthropology, University of Virginia.

Natalie Roche, Department of Pediatrics, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center.

Kathryn Vadnais, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University.

Danielle P. Parker, Department of Pediatrics, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center.

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator and mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiser M, Hou F. Language acquisition, unemployment and depressive disorder among Southeast Asian refugees: A 10-year study. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53(10):1321–1334. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00412-3. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. The acculturation process and refugee behavior. In: Williams CL, Westermeyer J, editors. Refugee mental health in resettlement countries. Hemisphere Publishing Corp; Washington, DC US: 1986. pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Tran N. Psychological distress and adjustment of Vietnamese refugees in the United States: Association with pre- and postmigration factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(1):109–120. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson JM, Mortensen EL, Kastrup M. A Follow-Up Study of Mental Health and Health-Related Quality of Life in Tortured Refugees in Multidisciplinary Treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193(10):651–657. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000180739.79884.10. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000180739.79884.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson JM, Mortensen EL, Kastrup M. Predictors of mental health and quality of life in male tortured refugees. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;60(1):51–57. doi: 10.1080/08039480500504982. doi: 10.1080/08039480500504982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung R, Bemak F, Kagawa-Singer M. Gender Differences in Psychological Distress among Southeast Asian Refugees. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1998;186(2):112–119. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199802000-00007. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199802000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology. 1990;13:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Smith KC. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. National Institutes of Health; 2011. Retrieved from http://obssr.od.nih.gov/mixed_methods_research. [Google Scholar]

- CSDH . Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. In: W. H. Organization, editor. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Danieli Y. International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, Redner R, Blakely CH, Mitchell CM, Emshoff JG. Diversion of juvenile offenders: An experimental comparison. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55(1):68–75. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.68. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Anstiss H, Ziaian T, Procter N, Warland J, Baghurst P. Help-seeking for mental health problems in young refugees: A review of the literature with implications for policy, practice, and research. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2009;46(4):584–607. doi: 10.1177/1363461509351363. doi: 10.1177/1363461509351363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong J, Scholte WF, Koeter MWJ, Hart AAM. The prevalence of mental health problems in Rwandan and Burundese refugee camps. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102(3):171–177. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102003171.x. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102003171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando GA, Miller KE, Berger DE. Growing pains: The impact of disaster-related and daily stressors on the psychological and psychosocial functioning of youth in Sri Lanka. Child Development. 2010;81(4):1192–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. The interpretation of cultures. BasicBooks; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J. MSU refugee well-being project training manual. Michigan State University; East Lansing, MI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J. Effectiveness of a Community-Based Advocacy and Learning Program for Hmong Refugees. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36(3-4):387–408. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8633-z. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8633-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J. Promoting Hmong Refugees' Well-Being Through Mutual Learning: Valuing Knowledge, Culture, and Experience. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;37(1-2):77–93. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9003-6. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J, Githinji A, Isakson B. Reducing health disparities experienced by refugees resettled in urban areas: A community-based transdisciplinary intervention model. In: Kirst M, Schaefer-McDaniel N, Hwang S, O'Campo P, editors. Converging disciplines: A transdisciplinary research approach to urban health problems. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J, Hang P, Yang M. Hmong refugees in the United States: A community-based advocacy and learning intervention. In: Rasco KEMLM, editor. The mental health of refugees: Ecological approaches to healing and adaptation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J, Isakson B, Hess JM, LaNoue M, Githinji A. A community-based advocacy and learning intervention for African refugee children and their families. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J, LaNoue M, Lee C, Freeland L, Freund R. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial findings from a community-based, cultural mental health intervention for American Indian youth and their families. Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;40(4):381–405. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20517. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorst-Unsworth C, Goldenberg E. Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq: Trauma-related factors compared with social factors in exile. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172:90–94. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauff E, Vaglum P. Organised violence and the stress of exile: Predictors of mental health in a community cohort of Vietnamese refugees three years after resettlement. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166(3):360–367. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.3.360. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isserlis J. Trauma and learning - what do we know, what can we learn? Paper presented at the Fifth Annual Low Educated Second Language and Literacy Acquisition Conference. Banff Alberta; Canada: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon D, Stansfield CW. Basic English Skills Test manual. Center for Applied Linguistics; Washington, D.C.: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja NG, White KM, Schweitzer R, Greenslade J. Difficulties and coping strategies of Sudanese refugees: A qualitative approach. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2008;45(3):489–512. doi: 10.1177/1363461508094678. doi: 10.1177/1363461508094678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K. Bread and roses: Supporting refugee women in a multicultural group. Intervention: International Journal of Mental Health, Psychosocial Work & Counselling in Areas of Armed Conflict. 2006;4(1):47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liang J. Dimensions of the Life Satisfaction Index A: A structural formulation. Journal of Gerontology. 1984;39(5):613–622. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.5.613. doi: No DOI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Kulkarni M, Kushner H. Beyond trauma-focused psychiatric epidemiology: Bridging research and practice with war-affected populations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(4):409–422. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.409. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Omidian P, Rasmussen A, Yaqubi A, Daudzai H. Daily stressors, war experiences, and mental health in Afghanistan. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2008;45(4):611–638. doi: 10.1177/1363461508100785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]