Abstract

On a daily basis, the heart is subjected to dramatic fluctuations in energetic demand and neurohumoral influences, many of which occur in a temporally predictable manner. In order to preserve cardiac performance, the heart must therefore maintain metabolic flexibility, even within the confines of a single day. Recent studies have established mechanistic links between time-of-day-dependent oscillations in myocardial metabolism and the cardiomyocyte circadian clock. More specifically, evidence suggests that this cell autonomous molecular mechanism regulates myocardial glucose uptake, flux through both glycolysis and the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, and pyruvate oxidation, as well as glycogen, triglyceride, and protein turnover. These observations have led to the hypothesis that the cardiomyocyte circadian clock confers the selective advantage of anticipation of increased energetic demand during the awake period. Here, we review the accumulative evidence in support of this hypothesis thus far, and discuss the possibility that attenuation of these metabolic rhythms, through disruption of the cardiomyocyte circadian clock, contributes towards the etiology of cardiac dysfunction in various disease states.

Keywords: Chronobiology, Heart, Metabolism, O-GlcNAcylation

Introduction

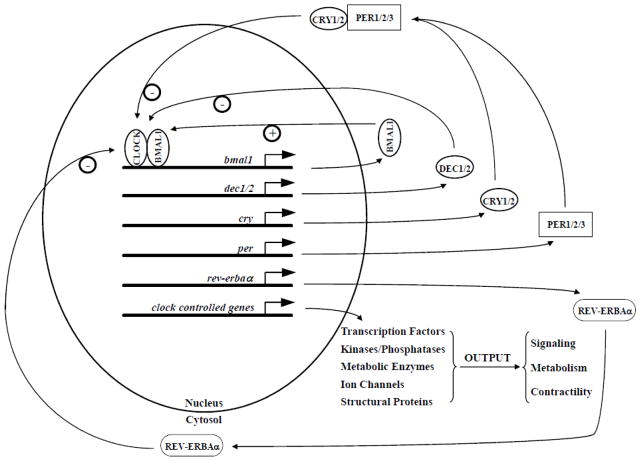

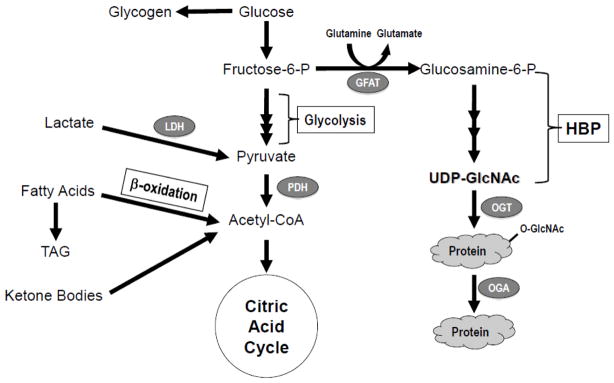

Anticipation is a selective advantage; intuitively, preparing for a specific stimulus or stressor before it occurs will facilitate an optimal response (in terms of both magnitude and timing of the response) [1]. A critical aspect of anticipation involves knowing when a distinct stimulus/stressor will present itself (i.e., prior to its onset) and in mammals this is conferred by circadian clocks [1, 2]. Circadian clocks are cell autonomous molecular mechanisms that reside within essentially all mammalian cells, including cardiomyocytes [2, 3]. These molecular mechanisms are comprised of a distinct set of transcription factors that form a series of positive and negative feedback loops, which oscillate with a periodicity of approximately 24 hours (Figure 1) [1, 2]. It has been estimated that circadian clocks modulate expression of approximately 10–15% of the transcriptome in a time-of-day-dependent manner [4–6]. Clock-regulated genes include critical modulators of transcription, translation, signal transduction, ion homeostasis, and metabolism [4–6]. Recent studies have highlighted a complex interaction between circadian clocks and metabolism, wherein clocks modulate metabolism over the course of the day, and metabolism fine tunes the clock [7, 8]. This interaction has been revealed both at the whole body and organ-specific level. [7, 8] The purpose of this review is to highlight recent advances regarding the influence that the cardiomyocyte circadian clock exerts over myocardial metabolism. We will initially provide a general overview on myocardial metabolism (Figure 2), followed by a summary regarding how the intrinsic cardiomyocyte clock modulates this important aspect of cardiac biology.

Figure 1. The cardiomyocyte circadian clock.

− represents a negative feedback loop. + represents a positive feedback loop. Clock controlled genes (also referred to as output genes) do not directly feedback on the circadian clock mechanism, and instead mediate time-of-day-dependent fluctuations in cardiac function.

Figure 2.

General overview of myocardial metabolic pathways.

Myocardial Metabolism – Energetics and Beyond

The ability of the heart to maintain contractile function and to rapidly adapt to acute changes in demand is predicated not only on the availability of carbon substrates for oxidative energy production but perhaps more importantly the metabolic flexibility needed to be able to utilize a continuously variable substrate milieu. The foundation of our understanding of metabolic regulation was established by the pioneering work of Randle and colleagues, who proposed in 1963 the classical glucose-fatty acid cycle in which increased fatty acid availability suppressed glucose oxidation [9]. This was followed over the next 2 decades or so, by increasingly sophisticated approaches to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the reciprocal relationship between glucose and fatty acid oxidation. The result was an emphasis on critical metabolism regulators, with increased CPT1 activity and fatty acid oxidation leading to decreased PDH activity and glucose oxidation. However, in addition to acute responses to substrate availability, in the setting of sustained metabolic dysfunction (e.g., during diabetes) the heart develops a metabolic inflexibility (characterized by increased fatty acid oxidation and decreased glucose oxidation in the case of diabetes). These observations have led to speculation that metabolic inflexibility in states such as diabetes and hypertrophy significantly contributes towards the etiology of contractile dysfunction [10, 11]. For example, it has become widely accepted that increased dependence on fatty acids for energy production impairs cardiomyocyte function because they are less efficient fuels (i.e., greater oxygen requirement per ATP generated, compared to glucose) and they cause “excess” proton production due to an “uncoupling” between glucose oxidation and glycolysis [12]. Increased cycling of fatty acyl groups through the triglyceride pool will also decrease cardiac efficiency [13]. Recent research efforts have also focused on the mechanisms by which excess fatty acid availability (during states such as diabetes) leads to cardiac dysfunction through imbalances in cellular signaling cascades [14].

Many studies of cardiac metabolism focus primarily on glucose and fatty acid utilization. Although under normal physiological conditions alternative fuels such as pyruvate and ketone bodies circulate at very low concentrations (i.e., <0.2mM), several studies suggest that they contribute significantly to oxidative energy production [15, 16]. Reliance on these alternative fuels likely increases further during physiologic states, such as increased physical activity. For example, during acute exercise bouts, circulating ketone bodies increase markedly [17]. Similarly, lactate, often considered a byproduct of glycolytic metabolism, is readily oxidized by the heart and circulating levels can be appreciable, easily reaching 3–5mM in response to moderate exercise [18]. The relative importance of considering these alternative fuels has been highlighted by us and others: when physiologically relevant mixtures of lactate and pyruvate are present in addition to glucose and fatty acids, increasing availability of exogenous fatty acids has little or no effect on glucose oxidation, but rather decreases lactate and pyruvate oxidation [19]. Similar observations were also seen in the diabetic heart, where decreased total carbohydrate oxidation is due to a reduction in lactate and pyruvate oxidation, with no change in glucose oxidation [19, 20].

While there is little doubt that acute augmentation of glucose uptake is cardioprotective and conversely prolonged exposure to high glucose impairs cardiomyocyte function, various studies (including some discussed above) suggest that these effects may extend beyond changes in oxidative energy metabolism [21, 22]. The hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) has long been recognized as a glucose or nutrient sensing pathway, and activation of this pathway has been implicated in the adverse effects associated with sustained hyperglycemia or diabetes [23, 24]. Glucose entry into the HBP is principally regulated by L-glutamine-D-fructose 6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT), which catalyzes the conversion of fructose-6-phosphate to glucosamine-6 phosphate, ultimately leading to the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc (Figure 2). UDP-GlcNAc is the substrate not only for traditional protein glycosylation but also for O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT: uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine: polypeptide β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase) a unique glycosyl transferase, which catalyzes the attachment of a single O-GlcNAc to specific Ser/Thr residues of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. This reversible post-translational modification of proteins draws parallels to phosphorylation, including modulation of protein activity, stability, and sub-cellular localization. OGT activity is very sensitive to changes in UDP-GlcNAc levels and thus the overall rate of O-GlcNAc synthesis appears to be tightly regulated by HBP flux; consequently, it has become fairly widely accepted that changes in the levels of O-GlcNAcylation represent a primary nutrient sensing mechanism in mammals. However, it should also be noted in addition to being regulated by OGT, protein O-GlcNAcylation is also regulated by O-GlcNAcase (OGA: β-N-acetylglucosaminidase), which catalyzes the removal of O-GlcNAc from proteins [23, 24].

The foundation for much of our understanding of the role of O-GlcNAc in regulating cellular function has been in the context of metabolic disease and nutrient excess [25]. Indeed many studies that have linked the adverse effects of hyperglycemia on various cells and tissue, including cardiomyocytes, to increased flux through the HBP and subsequent increases in O-GlcNAc levels [23]. However, it is now well established that protein O-GlcNAcylation goes well beyond simply mediating the adverse effects of hyperglycemia, and plays a critical role in regulating a diverse array of cellular processes, including cell survival and apoptosis, translation and transcription, signal transduction and proteasome function. Our knowledge of the impact of O-GlcNAcylation in heart has grown rapidly over the past decade or so; in addition to the detrimental effects of diabetes, acute activation of O-GlcNAc synthesis has been shown to be remarkably cardioprotective in the setting of ischemia/reperfusion and it has recently been reported that OGT and O-GlcNAc synthesis may be essential for the early activation of cardiomyocyte hypertrophic transcription pathways [26]. A number of key proteins involved in regulating metabolism are also known targets for O-GlcNAcylation, such as Akt, IRS1/2, GLUT4, glycogen synthase and most recently CD36/FAT (which contributes to transport of long chain fatty acids into the cell) [24, 27]. A number of transcription factors involved in metabolic regulation, including PPARα, FOXO1, CREB, ChREPB and LXRα have also been shown to be targets for O-GlcNAcylation [24, 25]. The potential importance of protein O-GlcNAcylation in acute physiologic regulation of cardiac function was also recently underscored by observations that total levels oscillate in the heart in a time-of-day-dependent manner [28].

Time-of-Day-Dependent Changes in Myocardial Metabolism

As highlighted in the preceding section, in order to maintain adequate cardiac output, the myocardium modifies metabolism in response to a host of environmental influences. Many of these environmental stimuli/stressors, such as workload, neural (e.g., sympathetic tone) and humoral (e.g., insulin) factors, fluctuate in a time-of-day-dependent manner [29–33]. For example, relative to the sleep phase the awake state is associated with an elevation in blood pressure and catecholamines, as well as other signals arising as a consequence of the transition from the fasting to fed state [34, 35]. Consequently, it is not surprising that myocardial metabolism exhibits a marked time-of-day-dependence at multiple levels with rhythms in carbohydrate, lipid, and protein turnover described for the heart both in vivo and ex vivo (as highlighted below).

During periods of increased energetic demand, the myocardium increases reliance on carbohydrate (glucose, glycogen and lactate) as a fuel [18, 36, 37]. Similarly, post-prandial elevations in circulating factors such as insulin are anticipated to promote glucose uptake and utilization by the heart, resulting in increased rates of glycolysis and glucose oxidation during the awake period (relative to the sleep phase), which persist in the ex vivo setting [28, 38]. A dichotomy exists for glycogen turnover, wherein increased cardiac work promotes glycogenolysis, while insulin stimulates glycogen synthesis [36, 39, 40]. However, it has been reported that in the heart net glycogen synthesis occurs during the active period (when cardiac work is increased), while net glycogenolysis occurs during the sleep phase [38]. Such observations appear to indicate that rhythms in feeding status exert dominance over glycogen metabolism; however, 24-hour rhythms in glycogen turnover observed in the ad libitum fed rodent persist even during prolonged fasting, suggesting that this is independent of feeding status [41]. With regards to glucose-mediated signaling in the heart, recent studies report that total protein O-GlcNAcylation is elevated in the heart during the active period, consistent with both increased substrate availability for the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, as well as OGT expression, at this time [28].

In contrast to reliance on carbohydrate metabolism, acute alterations in workload have minimal effects on rates of myocardial fatty acid oxidation [36]. Non-oxidative fatty acid metabolism (e.g., triglyceride turnover) is exquisitely sensitive to a host of neurohumoral factors know to oscillate in a time-of-day-dependent manner (e.g., adrenergic and insulin stimulation) [13, 42, 43]. Taken together, it is therefore not surprising that triglyceride turnover, but not fatty acid oxidation, has been shown to exhibit diurnal oscillations in the heart [38, 44]. Analogous to glycogen turnover, net triglyceride synthesis is increased in the heart during the active period, while net lipolysis is elevated during the sleep phase, as evidenced in both in vivo and ex vivo models [44]. Regarding lipid-derived signaling in the heart, net phospholipid (and cholesterol ester) synthesis appears to be highest during the sleep phase [38]. The potential functional consequence of this was recently highlighted when hearts were challenged with an acute elevation in fatty acid availability; greatest fatty acid-induced depression of contractile dysfunction is observed during the sleep phase [38].

Compared to carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, substantially less is known regarding time-of-day-dependent oscillations in protein turnover and amino acid metabolism in the heart. Intuitively, one would predict that during the active period post prandial signals, such as insulin would promote net protein synthesis as well as amino acid uptake, while increased energetic demand at this time might exert an opposing action. However, previously published studies reveal that net protein synthesis is increased in the myocardium during the sleep phase in the in vivo setting, and that they persist during fasting, suggesting that post-prandial signals do not play a dominant role [45]. Indirect evidence also exists that amino acid metabolism exhibits a diurnal variation in the heart, including observations that steady state levels of distinct amino acids are altered in the heart in a time-of-day-dependent manner, and that microarray studies reveal that gene expression of a number of key enzymes involved in amino acid metabolism similarly exhibit diurnal variations in the heart [4–6, 46]. Clearly additional studies are required to address important questions related to various aspects of organelle and protein turnover, as well as the mechanisms underlying rhythms in these fundamental processes in the heart.

Circadian Clock Regulation of Myocardial Metabolism

While it is evident from the discussion above that carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism exhibit time-of-day-dependent rhythms in the heart questions still remain as to how this regulation occurs and what the advantage of such rhythms might be. Insights into these fundamental questions are beginning to emerge, and are highlighted below.

Signals or stressors associated with active/sleep- and/or feeding/fasting-transitions could potentially mediate one or more aspects of diurnal variations in myocardial metabolism. These signals, namely workload, adrenergic stimulation, and/or insulin, fluctuate concomitantly with nutrient availability/intake. However, as alluded to above, a number of observations are inconsistent with this hypothesis, including the persistence of a number of metabolic oscillations both during prolonged fasting and under controlled ex vivo conditions. Furthermore, with regard to protein synthesis, oscillations in rates of this process are antiphase to the circulating levels of its major activator, insulin; in other words, rates of protein synthesis are at their highest when insulin levels are lowest [45, 47, 48]. Collectively, these observations suggest that time-of-day-dependent oscillations in myocardial metabolism cannot be mediated purely by factors extrinsic to the heart. One intrinsic mechanism in the heart, with the capability of modulating myocardial processes in a time-of-day-dependent manner, is the cardiomyocyte circadian clock [3, 29, 49].

Circadian clocks reside within essentially every mammalian cell, and influence cellular functions in a time-of-day-dependent manner [1, 2]. Accordingly, mouse models wherein circadian clock components have been genetically ablated in a ubiquitous manner exhibit varying degrees of circadian disruption at multiple levels, including behavioral, cellular, and molecular [50–52]. Two distinct mouse models have recently been generated in which the circadian clock mechanism has been disrupted in a cardiomyocyte-specific manner. These models each targeted one of two critical circadian clock components: CLOCK (disrupted in cardiomyocyte-specific CLOCK mutant [CCM] mice) and BMAL1 (disrupted in cardiomyocyte-specific BMAL1 knockout [CBK] mice) [6, 53]. In contrast to those animal models where the circadian clock was disrupted in the whole animal, these cardiac specific models exhibit normal behavioral and neurohumoral rhythms, enabling us to specifically explore the role of the cardiomyocyte circadian clock in the regulation of myocardial metabolism.

The time-of-day-dependent rhythms in glycolysis, glycogen synthesis, glucose oxidation, protein O-GlcNAcylation, and triglyceride synthesis which are all present in wild-type hearts are all abolished in CCM hearts, demonstrating their regulation by the intrinsic cardiomyocyte circadian clock [28, 44]. Although protein synthesis rates have yet to be determined in either of these models, indirect evidence suggests that the cardiomyocyte circadian clock may also influence this aspect of myocardial metabolism. For example, acute (1 week) isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy was shown to exhibit a time-of-day-dependence, with greatest hypertrophic growth during the sleep phase, which is consistent with greater protein synthesis rates during this time period: these time-of-day-dependent oscillations in hypertrophic growth are absent in CCM hearts [53]. As noted above, studies of cardiac metabolic regulation typically focus on glucose and fatty acid metabolism; however, Stowe et al have shown that the murine heart exhibits a relatively high reliance on ketone body utilization, even in the fed state [16]. More recently, in preliminary studies using both CCM and CBK mice we have found that myocardial ketone body utilization also appears to be under direct clock control (Young et al, unpublished observations).

These mouse models have also provided a valuable platform for identifying putative mediators linking the cardiomyocyte circadian clock with myocardial metabolism. A number of well-established key modulators of cardiac metabolism have been identified as being under the control of the cardiomyocyte circadian clock, including AMPK, GSK3β, Akt, OGT, GLUL, BDH1, DGAT2, and NAMPT [28, 44, 54]. Circadian regulation of NAMPT suggests influence of the cardiomyocyte clock on myocardial NAD metabolism, similar to that recently described studies in the liver [55, 56]. Indeed, NAD levels oscillate in wild-type hearts, and are chronically repressed in CCM hearts [44, 57]. The regulation of NAD levels in a diurnal manner by the cardiomyocyte circadian clock has the potential for impacting a host of NAD-dependent processes, particularly metabolism. It should be noted that myocardial metabolism in turn likely acts in a ‘feedback’ manner, to influence the cardiomyocyte circadian clock. For example, sirtuins (deacetylases) are sensitive to cellular NAD levels, and have been shown to deacetylate two established circadian clock components (BMAL1 and Per2) in a time-of-day-dependent manner [58–60].

As noted above O-GlcNAcylation is a nutrient driven post-translational modification of proteins, which has been linked to the regulation of a diverse array of cellular processes. Many of the proteins that have been shown to regulate cardiac metabolism and well as be modulated by the circadian clock, such as GSK3β, Akt and AMPK have all also been reported to be targets for O-GlcNAc modification [24, 25]. In the case of GSK3β and Akt, increased O-GlcNAcylation attenuates their activity, whereas O-GlcNAcylation of AMPK has been shown to increase its activity. It is also of note that GFAT, which regulates glucose entry into the HBP is phosphorylated by AMPK and this increases its activity thereby increasing glucose entry into the HBP. Given the substantial overlap between the circadian clock and O-GlcNAcylation in their regulatory roles we postulated that there may be an interrelationship between the two. We recently demonstrated not only that overall O-GlcNAc levels but also that OGT which catalyzes O-GlcNAc synthesis are both under circadian control [28]. Moreover we also found that that BMAL1 and Per1 are both O-GlcNAc modified, and furthermore that O-GlcNAcylation influences the timing of the circadian clock [28]. Overall this study demonstrated for the first time a close and intertwined relationship between cardiac metabolism, protein O-GlcNAcylation and the circadian clock. The fact that these observations may be more generally relevant was supported by subsequent studies in drosophila where altered OGT expression was shown to influence circadian rhythms and that dPER, the Drosophila PERIOD protein was an O-GlcNAc target [61].

While there is no doubt that the cardiomyocyte circadian clock and myocardial metabolism are intertwined, the question remains as to what advantage might arise from such a close relationship? The answer likely resides within the general function of circadian clocks: anticipation. What might the heart be anticipating? In general terms, the myocardium has two ‘major’ behavioral oscillations to contend with on a daily basis. These are awake/sleep and feeding/fasting rhythms. In terms of evolutionary selective pressures, it is important to note that not only are awake/sleep cycles more predictable on a daily basis but also that foraging for food, avoidance of predation, and reproduction, which occur during the awake period, are all energetically demanding, on both the organism as a whole, as well as the heart. Energetic demands during the active period remain high, even if the animal in the wild is not successful in its forage for food. As such, organisms that are able to anticipate this scenario (i.e., rhythms of physical activity/energetic demand independent of feeding status) would undoubtedly have an evolutionary selective advantage. We hypothesize that the cardiomyocyte circadian clock confers this selective advantage.

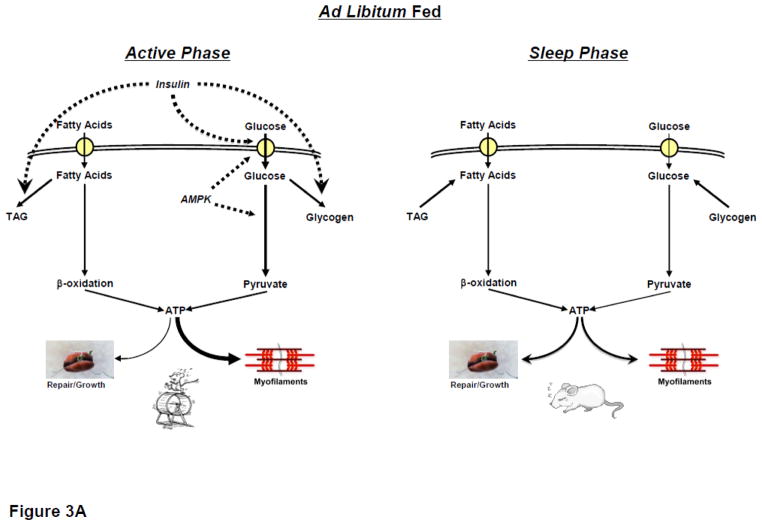

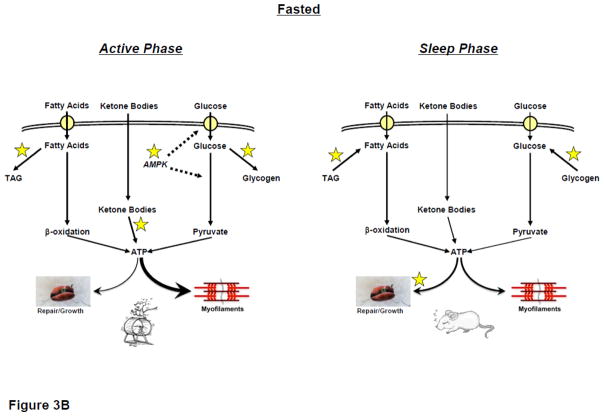

Based on evidence to date, we propose a hypothetic model in which the cardiomyocyte circadian clock allows the heart to anticipate daily rhythms in physical activity (particularly during periods of prolonged fasting), through time-of-day-dependent modulation of myocardial metabolism (Figure 3). During periods of increased energetic demand, the myocardium increases its reliance on carbohydrate as a fuel [36, 37]. Consistent with the latter, the cardiomyocyte circadian clock increases glucose uptake and utilization during the active phase, when myocardial AMPK activity peaks [28, 38, 44]. During fasting, inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase (i.e., Randal cycle) minimizes carbohydrate oxidation capacity [9]. However, circadian clock mediated increased glucose uptake during the active period would provide glycolytic and glycogenesis precursors, increased flux through the HBP, glycolysis, and glycogen storage (for subsequent utilization during the resting period), despite prolonged fasting. Indeed, as an example, in contrast to most tissues, myocardial glycogen stores increase during an overnight fast [62]. Similar to glycogen synthesis, the circadian clock mediates increased triglyceride synthesis during the active period [44]. Increased circulating fatty acids during prolonged fasting, coupled with circadian clock-mediated increased triglyceride synthesis capacity during the active period, promote triglyceride accumulation in the heart (for subsequent utilization during the resting period). Furthermore, circadian clock-dependent increased transcriptional responsiveness of the heart to fatty acids during the active period will reinforce promotion of fatty acid uptake and oxidation during prolonged fasting through changes in maximal capacity [63].

Figure 3. Hypothetical model for cardiomyocyte clock-mediated metabolic anticipation of increased energetic demand during the active period compared to the sleep period.

Thickness of line indicates predicted flux through a pathway. Dashed line represents positive regulatory effect. * represents cardiomyocyte circadian clock control.

During periods of sustained activity (e.g., >1 hour; which potentially occurs during foraging for food), circulating ketone bodies elevate markedly [17]. Cardiomyocyte circadian clock promotion of ketone body utilization during the active period would likely provide a significant fuel source for the contracting myocardium. Similarly, circulating lactate levels also become elevated during exercise [18]; however, whether the cardiomyocyte circadian clock promotes lactate utilization during the active period is currently unknown. During periods of increased physical activity, the likelihood of protein damage (e.g., through oxidative stress) is increased. Protein and organelle turnover is an energetically demanding process, which could potentially compete with contractile processes during the active period. Consistent with this rationale, the cardiomyocyte circadian clock likely increases net myocardial protein synthesis during the sleep/less active phase, as a means to replace damaged proteins/organelles at this time.

Implications for Health and Disease

It is clear from animal-based studies reported to date that cardiomyocyte circadian clock-mediated rhythms in myocardial metabolism exhibit close correlates with physical activity rhythms [28, 38, 64]. This includes increased glucose uptake, glycolytic flux, and oxidation during the active period (even when assessed ex vivo) [28, 38, 64]. As discussed above, increased glucose metabolism during the active period will undoubtedly act as an important source of ATP to meet increased energetic demands at this time. In doing so, the cardiomyocyte circadian clock therefore likely facilitates increased heart rate and cardiac output during the active period. Consistent with this hypothesis, CCM hearts exhibit decreased heart rate and cardiac output diurnal variations, due to an impairment in contractile function during the active period [6].

Maintenance of circadian synchronization (i.e., appropriate alignment of intrinsic rhythms with rhythms in environmental stimuli/stressors) is essential for cardiovascular function. This concept was highlighted by elegant studies by Martino and colleagues [65]. Hamsters carrying one mutant allele for tau (casein kinase 1ε) possess an intrinsic circadian clock with a periodicity of approximately 22 hours (as opposed to 24 hours in wild-type hamsters). When heterozygous tau hamsters are housed within a normal 12h:12h light:dark cycle (i.e., dyssynchronization between endogenous and environmental rhythms), age-dependent cardiovascular disease (both cardiac and renal) develops. However, when these same mutant hamsters are housed in an 11h:11h light:dark cycle (i.e., synchronization between endogenous and environmental rhythms), age-dependent cardiovascular disease development is not observed [65]. Given that circadian clocks directly modulate metabolism in a time-of-day-dependent manner, the possibility arises that a mismatch between myocardial metabolism rhythms (intrinsically driven) and energetic demand (extrinsically driven) might contribute towards contractile dysfunction. Indeed, the heart clock has been shown to be modulated by a host of cardiovascular disease risk factors, including pressure overload, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, coronary artery ligation, simulated shift work, and aging [53, 63, 66–69]. Although a plethora of studies have reported altered myocardial metabolism in response to many of these stresses, we are unaware of studies that have directly assessed whether diurnal variations in myocardial metabolic fluxes are altered. Indirect evidence, including time-of-day-dependent oscillations in metabolic gene expression, suggests that this may be the case [66, 68–71]. Clearly additional studies are required to determine the impact of disrupted diurnal variations in myocardial metabolism on the etiology of cardiac contractile dysfunction.

Challenges and Future Directions

Figure 2 outlines an evidence-based hypothetical selective advantage for regulation of myocardial metabolism by the cardiomyocyte circadian clock (i.e., anticipation of daily activity rhythms, independent of feeding status). Future studies are required to provide further support for, or to refute against, the validity of this model. If true, one would predict that CCM and/or CBK mice would exhibit poor cardiac function and/or exercise performance during periods of prolonged fasting. Additional studies are also required in order to firmly establish mechanistic links between the cardiomyocyte circadian clock and myocardial metabolism. Examples of unanswered questions include “does cardiomyocyte circadian clock regulation of AMPK mediate time-of-day-dependent oscillations in myocardial glucose uptake and utilization?”, “does the cardiomyocyte circadian clock anticipate utilization of alternative fuels (e.g., ketone bodies, lactate) during the active period?”, and “what role does cardiomyocyte circadian clock regulation of protein O-GlcNAcylation play in cardiac biology?”. A third area of interest revolves around the concept that disruption of normal circadian clock function, and subsequent disruption of diurnal rhythms in myocardial metabolism, contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease development. This is particularly prudent in light of the fact of circadian clocks are exquisitely sensitive to environmental cues, many of which are common cardiovascular disease risk factors. This includes nutrient intake: alterations in the quantity, quality, and timing of food intake modulate circadian clocks in tissue-specific manners [72, 73]. As such, ‘inappropriate’ timing of food intake can cause internal circadian dyssynchrony (e.g., sleep-phase restricted feeding causes a 8-hour phase shift in the liver clock, but only a 4-hour phase shift in the heart clock, resulting in liver-heart dyssychrony; Young, unpublished observations). Future studies are required to elucidate fully the pathologic consequences of environment-induced circadian dyssynchrony on cardiac function. As we move closer to a 24-hour society, with continuous access to light and food, disruption of circadian biology is becoming common place.

Summary

Both myocardial metabolism and contractile function oscillate as a function of time-of-day. During the active/awake period, increased energetic demand is associated with greater rates of myocardial carbohydrate utilization, in addition to storage of glucose and fatty acids as glycogen and triglyceride (respectively). The cardiomyocyte circadian clock appears to play a pivotal role in mediating daily rhythms in myocardial metabolism. This has given rise to the hypothesis that the cardiomyocyte circadian clock allows the heart to anticipate periods of increased energetic demand, independent of feeding status. Whether disruption of the cardiomyocyte circadian clock in response to environmental cues contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiac dysfunction through modulation of myocardial metabolism is an attractive hypothesis that requires further interrogation.

Highlights.

The cardiomyocyte circadian clock directly regulates myocardial metabolism in a time-of-day-dependent manner

The cardiomyocyte circadian clock allows the heart to anticipate environmental stresses/stimuli

Circadian dyssynchrony likely contributes towards the etiology of cardiovascular disease

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (MEY: HL-074259 and HL-106199; JCC HL101192 and HL079364).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Edery I. Circadian rhythms in a nutshell. Physiol Genomics. 2000;3:59–74. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.3.2.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, McDearmon EL. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008 Oct;9(10):764–75. doi: 10.1038/nrg2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durgan DJ, Young ME. The cardiomyocyte circadian clock: emerging roles in health and disease. Circ Res. 2010 Mar 5;106(4):647–58. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storch KF, Lipan O, Leykin I, Viswanathan N, Davis FC, Wong WH, et al. Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature. 2002 May 2;417(6884):78–83. doi: 10.1038/nature744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martino T, Arab S, Straume M, Belsham DD, Tata N, Cai F, et al. Day/night rhythms in gene expression of the normal murine heart. J Mol Med. 2004 Apr;82(4):256–64. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray M, Shaw C, Moore M, Garcia R, Zanquetta M, Durgan D, et al. Disruption of the circadian clock within the cardiomyocyte influences myocardial contractile function; metabolism; and gene expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1036–H47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01291.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bass J, Takahashi JS. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science. 2010 Dec 3;330(6009):1349–54. doi: 10.1126/science.1195027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray MS, Young ME. Regulation of fatty acid metabolism by cell autonomous circadian clocks: time to fatten up on information? J Biol Chem. 2011 Apr 8;286(14):11883–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.214643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randle PJ, Garland PB, Hales CN, Newsholme EA. The glucose fatty-acid cycle. Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1963 Apr 13;1(7285):785–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)91500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taegtmeyer H, McNulty P, Young ME. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in diabetes: Part I: general concepts. Circulation. 2002 Apr 9;105(14):1727–33. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012466.50373.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taegtmeyer H. Metabolism--the lost child of cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1386–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00870-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopaschuk GD, Wambolt RB, Barr RL. An imbalance between glycolysis and glucose oxidation is a possible explanation for the detrimental effects of high levels of fatty acids during aerobic reperfusion of ischemic hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993 Jan;264(1):135–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swanton EM, Saggerson ED. Effects of adrenaline on triacylglycerol synthesis and turnover in ventricular myocytes from adult rats. Biochem J. 1997 Dec 15;328(Pt 3):913–22. doi: 10.1042/bj3280913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CD, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC. Myocardial Fatty Acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010 Jan;90(1):207–58. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd S, Brocks C, Chatham JC. Differential modulation of glucose, lactate, and pyruvate oxidation by insulin and dichloroacetate in the rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003 Jul;285(1):H163–72. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01117.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stowe KA, Burgess SC, Merritt M, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Storage and oxidation of long-chain fatty acids in the C57/BL6 mouse heart as measured by NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 2006 Jul 24;580(17):4282–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Askew EW, Dohm GL, Huston RL. Fatty acid and ketone body metabolism in the rat: response to diet and exercise. J Nutr. 1975 Nov;105(11):1422–32. doi: 10.1093/jn/105.11.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kemppainen J, Fujimoto T, Kalliokoski KK, Viljanen T, Nuutila P, Knuuti J. Myocardial and skeletal muscle glucose uptake during exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2002 Jul 15;542(Pt 2):403–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatham J, Gao Z, Forder J. Impact of 1 wk of diabetes on the regulation of myocardial carbohydrate and fatty acid oxidation. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E342–E51. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.2.E342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatham JC, Gao ZP, Bonen A, Forder JR. Preferential inhibition of lactate oxidation relative to glucose oxidation in the rat heart following diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 1999 Jul;43(1):96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatham JC, Marchase RB. The role of protein O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine in mediating cardiac stress responses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Feb;1800(2):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngoh GA, Jones SP. New insights into metabolic signaling and cell survival: the role of beta-O-linkage of N-acetylglucosamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008 Dec;327(3):602–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laczy B, Hill BG, Wang K, Paterson AJ, White CR, Xing D, et al. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: a new signaling paradigm for the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009 Jan;296(1):H13–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01056.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darley-Usmar VM, Ball LE, Chatham JC. Protein O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine: a novel effector of cardiomyocyte metabolism and function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012 Mar;52(3):538–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hart GW, Slawson C, Ramirez-Correa G, Lagerlof O. Cross Talk Between O-GlcNAcylation and Phosphorylation: Roles in Signaling, Transcription, and Chronic Disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011 Jun 7;80:825–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Facundo HT, Brainard RE, Watson LJ, Ngoh GA, Hamid T, Prabhu SD, et al. O-GlcNAc Signaling is Essential for NFAT-Mediated Transcriptional Reprogramming During Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012 Mar 9; doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00775.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laczy B, Fulop N, Onay-Besikci A, Des Rosiers C, Chatham JC. Acute regulation of cardiac metabolism by the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway and protein O-GlcNAcylation. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durgan DJ, Pat BM, Laczy B, Bradley JA, Tsai JY, Grenett MH, et al. O-GlcNAcylation, novel post-translational modification linking myocardial metabolism and cardiomyocyte circadian clock. J Biol Chem. 2011 Dec 30;286(52):44606–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young M. The circadian clock within the heart: potential influence on myocardial gene expression; metabolism; and function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1–H16. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00582.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linsell CR, Lightman SL, Mullen PE, Brown MJ, Causon RC. Circadian rhythms of epinephrine and norepinephrine in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985 Jun;60(6):1210–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-6-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon RD, Wolfe LK, Island DP, Liddle GW. A diurnal rhythm in plasma renin activity in man. J Clin Invest. 1966 Oct;45(10):1587–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI105464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz FH, Romfh P, Smith JA. Diurnal variation of plasma aldosterone, cortisol and renin activity in supine man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1975 Jan;40(1):125–34. doi: 10.1210/jcem-40-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Portaluppi F, Montanari L, Bagni B, degli Uberti E, Trasforini G, Margutti A. Circadian rhythms of atrial natriuretic peptide, blood pressure and heart rate in normal subjects. Cardiology. 1989;76(6):428–32. doi: 10.1159/000174529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richards AM, Nicholls MG, Espiner EA, Ikram H, Cullens M, Hinton D. Diurnal patterns of blood pressure, heart rate and vasoactive hormones in normal man. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1986;8(2):153–66. doi: 10.3109/10641968609074769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuck ML, Stern N, Sowers JR. Enhanced 24-hour norepinephrine and renin secretion in young patients with essential hypertension: relation with the circadian pattern of arterial blood pressure. Am J Cardiol. 1985 Jan 1;55(1):112–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodwin G, Taylor C, Taegtmeyer H. Regulation of energy metabolism of the heart during acute increase in heart work. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29530–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allard M, Schonekess B, Henning S, English D, Lopaschuk G. Contribution of oxidative metabolism and glycolysis to ATP production in hypertrophied hearts. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H742–H50. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.2.H742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durgan D, Moore M, Ha N, Egbejimi O, Fields A, Mbawuike U, et al. Circadian rhythms in myocardial metabolism and contractile function: influence of workload and oleate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2385–H93. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01361.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adolfsson S, Isaksson O, Hjalmarson A. Effect of insulin on glycogen synthesis and synthetase enzyme activity in the perfused rat heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972 Aug 18;279(1):146–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(72)90249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Das I. Effects of heart work and insulin on glycogen metabolism in the perfused rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1973 Jan;224(1):7–12. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.224.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishikawa K, Shimazu T. Daily rhythms of glycogen synthetase and phosphorylase activities in rat liver: influence of food and light. Life Sci. 1976 Dec 15;19(12):1873–8. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sultan AM, Khan ZA. The impact of physiological insulin concentration and depletion on the metabolism of glucose, endogenous glycogen, and triglycerides in the isolated perfused heart. Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;75(3):183–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Donnell JM, Zampino M, Alpert NM, Fasano MJ, Geenen DL, Lewandowski ED. Accelerated triacylglycerol turnover kinetics in hearts of diabetic rats include evidence for compartmented lipid storage. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Mar;290(3):E448–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00139.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai JY, Kienesberger PC, Pulinilkunnil T, Sailors MH, Durgan DJ, Villegas-Montoya C, et al. Direct regulation of myocardial triglyceride metabolism by the cardiomyocyte circadian clock. J Biol Chem. 2010 Jan 29;285(5):2918–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rau E, Meyer DK. A diurnal rhythm of incorporation of L-[3H] leucine in myocardium of the rat. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab. 1975;7:105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai J, Young M. Diurnal variations in myocardial metabolism. Heart and Metabolism. 2009;44:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benavides A, Siches M, Llobera M. Circadian rhythms of lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase activities in intermediate metabolism of adult rat. Am J Physiol. 1998 Sep;275(3 Pt 2):R811–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.3.R811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jefferson LS. Lilly Lecture 1979: role of insulin in the regulation of protein synthesis. Diabetes. 1980 Jun;29(6):487–96. doi: 10.2337/diab.29.6.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young ME. Anticipating anticipation: pursuing identification of cardiomyocyte circadian clock function. J Appl Physiol. 2009 Oct;107(4):1339–47. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00473.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vitaterna M, King D, Chang A, Kornhauser J, Lowrey P, McDonald J, et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene; Clock; essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264:719–25. doi: 10.1126/science.8171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turek F, Joshu C, Kohsaka A, Lin E, Ivanova G, McDearmon E, et al. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in Clock mutant mice. Science. 2005;308:1043–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1108750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kondratov RV, Kondratova AA, Gorbacheva VY, Vykhovanets OV, Antoch MP. Early aging and age-related pathologies in mice deficient in BMAL1, the core componentof the circadian clock. Genes Dev. 2006 Jul 15;20(14):1868–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.1432206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Durgan DJ, Tsai JY, Grenett MH, Pat BM, Ratcliffe WF, Villegas-Montoya C, et al. Evidence suggesting that the cardiomyocyte circadian clock modulates responsiveness of the heart to hypertrophic stimuli in mice. Chronobiol Int. 2011 Apr;28(3):187–203. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.550406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Durgan D, Pulinilkunnil T, Villegas-Montoya C, Garvey M, Frangogiannis N, Michael L, et al. Short communication: ischemia/reperfusion tolerance is time-of-day-dependent: mediation by the cardiomyocyte circadian clock. Circ Res. 2010;106:546–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramsey KM, Yoshino J, Brace CS, Abrassart D, Kobayashi Y, Marcheva B, et al. Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis. Science. 2009 May 1;324(5927):651–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1171641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakahata Y, Sahar S, Astarita G, Kaluzova M, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian control of the NAD+ salvage pathway by CLOCK-SIRT1. Science. 2009 May 1;324(5927):654–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1170803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powanda MC, Wannemacher RW., Jr Evidence for a linear correlation between the level of dietary tryptophan and hepatic NAD concentration and for a systematic variation in tissue NAD concentration in the mouse and the rat. J Nutr. 1970 Dec;100(12):1471–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/100.12.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bellet MM, Orozco-Solis R, Sahar S, Eckel-Mahan K, Sassone-Corsi P. The Time of Metabolism: NAD+, SIRT1, and the Circadian Clock. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011 Dec 16; doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asher G, Gatfield D, Stratmann M, Reinke H, Dibner C, Kreppel F, et al. SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell. 2008 Jul 25;134(2):317–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doi M, Hirayama J, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian regulator CLOCK is a histone acetyltransferase. Cell. 2006 May 5;125(3):497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim EY, Jeong EH, Park S, Jeong HJ, Edery I, Cho JW. A role for O-GlcNAcylation in setting circadian clock speed. Genes Dev. 2012 Mar 1;26(5):490–502. doi: 10.1101/gad.182378.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans G. The glycogen content of the rat heart. J Physiol. 1934 Nov 12;82(4):468–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1934.sp003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Durgan D, Trexler N, Egbejimi O, McElfresh T, Suk H, Petterson L, et al. The circadian clock within the cardiomyocyte is essential for responsiveness of the heart to fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24254–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young M, Razeghi P, Cedars A, Guthrie P, Taegtmeyer H. Intrinsic diurnal variations in cardiac metabolism and contractile function. Circ Res. 2001;89:1199–208. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martino TA, Oudit GY, Herzenberg AM, Tata N, Koletar MM, Kabir GM, et al. Circadian rhythm disorganization produces profound cardiovascular and renal disease in hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008 May;294(5):R1675–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00829.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Young M, Razeghi P, Taegtmeyer H. Clock genes in the heart: characterization and attenuation with hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2001;88:1142–50. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mohri T, Emoto N, Nonaka H, Fukuya H, Yagita K, Okamura H, et al. Alterations of circadian expressions of clock genes in dahl salt-sensitive rats fed a high-salt diet. Hypertension. 2003;42:189–94. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000082766.63952.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Young M, Wilson C, Razeghi P, Guthrie P, Taegtmeyer H. Alterations of the Circadian Clock in the Heart by Streptozotocin-induced Diabetes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:223–31. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kung T, Egbejimi O, Cui J, Ha N, Durgan D, Essop M, et al. Rapid attenuation of circadian clock gene oscillations in the rat heart following ischemia-reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:744–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Durgan D, Smith J, Hotze M, Egbejimi O, Cuthbert K, Zaha V, et al. Distinct transcriptional regulation of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms and cytosolic thioesterase 1 in the rodent heart by fatty acids and insulin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2480–H97. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01344.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stavinoha M, RaySpellicy J, Essop M, Graveleau C, Abel E, Hart-Sailors M, et al. Evidence for mitochondrial thioesterase 1 as a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-regulated gene in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:E888–E95. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00190.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kohsaka A, Laposky AD, Ramsey KM, Estrada C, Joshu C, Kobayashi Y, et al. High-fat diet disrupts behavioral and molecular circadian rhythms in mice. Cell Metab. 2007 Nov;6(5):414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Damiola F, Le MN, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2950–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.183500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]