Abstract

Distribution and activity of mitochondria are key factors in neuronal development, synaptic plasticity and axogenesis. The majority of energy sources, necessary for cellular functions, originate from oxidative phosphorylation located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. The adenosine-5’- triphosphate production is regulated by many control mechanism–firstly by oxygen, substrate level, adenosine-5’-diphosphate level, mitochondrial membrane potential, and rate of coupling and proton leak. Recently, these mechanisms have been implemented by “second control mechanisms,” such as reversible phosphorylation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes and electron transport chain complexes, allosteric inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, thyroid hormones, effects of fatty acids and uncoupling proteins. Impaired function of mitochondria is implicated in many diseases ranging from mitochondrial myopathies to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mitochondrial dysfunctions are usually related to the ability of mitochondria to generate adenosine-5’-triphosphate in response to energy demands. Large amounts of reactive oxygen species are released by defective mitochondria, similarly, decline of antioxidative enzyme activities (e.g. in the elderly) enhances reactive oxygen species production. We reviewed data concerning neuroplasticity, physiology, and control of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and reactive oxygen species production.

Keywords: neural regeneration, reviews, mitochondria, metabolic pathway, membrane potential, oxidative phosphorylation, electron transport chain complex, reactive oxygen species, respiratory state, calcium, uncoupling protein, fatty acid, neuroregeneration

Research Highlights

(1) Regulation of cellular bioenergetics is crucial in processes of neuroplasticity and neurotoxicity.

(2) Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is the most important source of cellular energy in the form of adenosine-5’-triphosphate.

(3) The adenosine-5’-triphosphate production is regulated primarily by oxygen, substrate level, adenosine-5’-diphosphate level, mitochondrial membrane potential, rate of coupling and proton leak.

(4) This review article focuses on the mitochondrial processes related to neuroplasticity, control of oxidative phosphorylation and production of reactive oxygen species.

(5) The regulatory mechanisms of cellular bioenergetics are summarized with aim to better understand the function, physiology as well as pathophysiology of various diseases, including neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondrial distribution and activity are key factors in neuronal morphogenesis-synaptogenesis, developmental and synaptic plasticity and axogenesis. During development, neuronal stem cells proliferate and differentiate into neurons; subsequently axons and dendrites form synapses[1,2]. The role of mitochondria in neuroplasticity consists in changes of adenosine-5’-triphosphate production, production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, initiation of apoptotic processes and participation in calcium homeostasis[3]. Due to adenosine-5’-triphosphate production and importance of mitochondria in synaptic ion homeostasis and phosphorylation reactions, mitochondria would be accumulated at sites where adenosine-5’-triphosphate consumption and Ca2+ concentration are higher. It was reported that mitochondria are more abundant in the regions of growing axons than in non-growing axons. Mitochondrial net movement is anterograde in growing axons and is retrograde in non-growing axons. Shortly before axogenesis, mitochondria congregate at the base of the neurite that is destined to become an axon. Nerve growth factor was found as one of the signals inducing accumulation of mitochondria in the active growing cone[4]. Interestingly, when adenosine-5’-triphosphate production is impaired and cells provide alternative source of energy, axogenesis is abolished although growth of dendrites remains relatively unaffected[1].

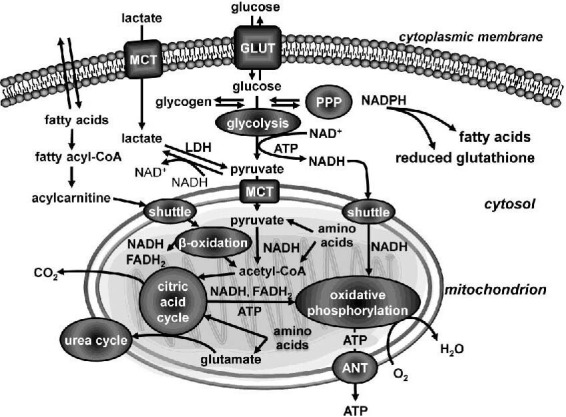

Changes in mitochondrial energy metabolism (Figure 1) can be observed in brain cells during the central nervous system development. During embryonic and early postnatal development, fats are primary fuel, later on, glucose becomes the fuel. This fact supports the role of mitochondria in biochemical requirements of highly proliferative neuronal stem cells and post-mitotic neurons. During neuronal differentiation, the number of mitochondria per cell increases, but the velocity, at which individual mitochondria move, decreases as neurite outgrowth slows and synaptogenesis occurs[3,5].

Figure 1.

Integration of metabolic pathways.

Glucose is transported over a plasma membrane by a glucose transporter (GLUT) and is metabolized to pyruvate by glycolysis. Pyruvate is converted to acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) in the mitochondria, where it is oxidized to CO2 through the citric acid cycle; redox energy is conserved as reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). The mitochondrial respiratory chain couples oxidation of NADH and reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2) to the formation of the electrochemical proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane, which is used to generate adenosine-5’-triphosphate (ATP). ATP produced from oxidative phosphorylation is transported from the mitochondrial matrix to the cytoplasm by the adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT).

Glucose may be stored as glycogen. Fatty acids and amino acids can also be bioenergetics precursors; however, glucose is considered to be the only metabolic substrate in the brain. Glucose can also be metabolized via the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), a process that generates pentoses and that is the most important cytosolic source of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), a cofactor for biosynthetic reactions and the oxidation-reduction involved in protecting against the oxidative stress, e.g. for fatty acid biosynthesis or regeneration of reduced glutathione.

During activation, the brain may transiently turn to aerobic glycolysis occurring in astrocytes, followed by the oxidation of lactate by neurons. Monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) carry lactate or pyruvate across biological membranes; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) catalyzes the interconversion of pyruvate and lactate with concomitant interconversion of NADH to oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+).

It was demonstrated that neuronal activity is influenced by the mitochondrial functions; defective trafficking and dysfunction of mitochondria from axon terminals is implicated in pathogenesis of axonal degeneration[6]. In addition, dendritic mitochondria are essential in morphogenesis and plasticity of spines and synapses[7]. Recent findings suggest roles for mitochondria as mediators of at least some effects of glutamate and brain-derived neurotrophic factor on synaptic plasticity[4]. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes synaptic plasticity partially by enhancing mitochondrial energy production. It increases glucose utilization as well as increases mitochondrial respiratory coupling at complex[8].

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles; their function is modulated by fission, fusion, and movement within the axons and dendrites[9]. Their structure, functions and properties differ in axons and dendrites[7]. Transport and positioning of mitochondria are essential for neuronal homeostasis and mitochondrial movement is a part of regulation by intracellular signals.

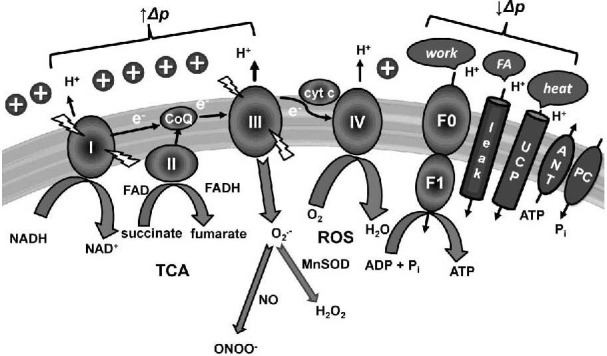

The respiratory chain is localized in cristae, structures formed by the inner mitochondrial membrane and extending the surface[4]. Electron transport chain consists of complexes with supramolecular organization, where mitochondrial proton pumps (complexes I, III and IV) transport protons and generate proton gradient[10] (Figure 2). Complex I (EC 1.6.5.3, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase) is the main entrance into electron transport chain and crucial point of respiration. It catalyzes oxidation of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, thus, regenerates oxidized form of nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide for the tricarboxylic acid cycle and fatty acids oxidation, and reduces coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone) to ubiquinol[11]. Four protons are pumped from the matrix into the intermembrane space while two electrons pass through the complex I. Complex II (EC 1.3.5.1, succinate dehydrogenase (ubiquinone)) is the side entry into electron transport chain, directly involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle. It is a 4 subunit membrane-bound lipoprotein, which couples the oxidation of succinate to the reduction of coenzyme Q10[12]. Succinate dehydrogenase includes covalently attached flavin adenine dinucleotide cofactor. In the tricarboxylic acid cycle, it oxidizes succinate to fumarate along with reduction of flavin adenine dinucleotide to hydroquinone form. In oxidative phosphorylation, electrons from oxidation of reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide are tunneled and transferred to coenzyme Q10. Complex II does not contribute to the proton gradient. The firstly mentioned cofactor, coenzyme Q10, is responsible for transferring electrons from complexes I and II to complex III; the second important cofactor is cytochrome c, which transfers electrons from complex III (EC 1.10.2.2, coenzyme Q10-cytochrome c reductase) to complex IV (EC 1.9.3.1, cytochrome c oxidase) by transiently binding to the membrane proteins[13]. Both of them modulate energy and free radical production[9,14]. Electrons are continuously transported to complex III, which consists of two centers, Qi center–facing to matrix; and Qo center–oriented to intermembrane space[15]. Complex III catalyzes the oxidation of one molecule of ubiquinol and the reduction of two molecules of cytochrome c. Reaction mechanism of complex III occurs in two steps called the Q cycle[16]. In the process of Q cycle, four protons are released into the inter membrane space. Finally, complex IV enables the terminal reduction of O2 to H2O, retains all partially reduced intermediates until full reduction is achieved[17]. The complex IV mediates pumping of 4 protons across the membrane. Complex V (EC 3.6.3.14, adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase) consists of two regions: (1) F1 portion is a soluble domain with three nucleotide binding sites; it is localized above the inner side of the membrane and stably connected with Fo domain; (2) Fo portion is a proton pore embedded in the membrane; it consists of three subunits and spans the membrane from the inner to the outer side[18,19]. This formation enables the conversion of electrochemical potential energy to chemical energy – a portion of the Fo rotates as the protons pass through the membrane and forces F1 as motor to synthesize adenosine-5’-triphosphate[20].

Figure 2.

Representation of processes in the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Electron transport chain consists of I–IV complexes that transfer electrons, pump protons outwardly, and create proton motive force (Δp). Complex I (I) catalyzes oxidation of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). Complex II (II), which is directly involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) oxidizes succinate to fumarate along with reduction of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD+) to hydroquinone form (FADH). Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ) as a cofactor accepts electrons from complexes I and II, and carries them to complex III (III); the second mobile carrier cytochrome c (cyt c) move electrons from complex III to complex IV (IV), where oxygen (O2) is finally reduced to water (H2O).

The proton gradient is primarily consumed by ATP synthase (F0F1) for adenosine-5’-triphosphate (ATP) synthesis from adenosine-5’-diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). Secondary consumers causing decreased Δp are uncoupling proteins (UCPs), they response to heat production; proton leak is mediated e.g. by fatty acids (FA). Transport of ADP and ATP across the membrane is enabled by adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT); mitochondrial phosphate carrier protein (PC) catalyzes movement of Pi into the mitochondrial matrix.

Simultaneously, electron transport is accompanied by reactive oxygen species (ROS), the highest amount of superoxide (O2•−) is formed by complexes I and III. O2•− can be further transformed by manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), or can react with nitric oxide (NO) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO-). O2•− production leads to increased mitochondrial conductance through UCPs.

Recently, a supramolecular organization of adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase with adenine nucleotide transporter and phosphate carrier was observed. Adenosine-5’- triphosphate synthase is organized in dimeric rows in the most curved part of cristae. Such organization suggests the role of the folded membrane and coordination of adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthesis[20,21].

REGULATION OF OXIDATIVE PHOSPHORYLATION

There are five levels of oxidative phosphorylation regulation: (1) direct modulation of electron transport chain kinetic parameters; (2) regulation of intrinsic efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation (by changes in proton conductance, in the measure of oxidative phosphorylation or in the channeling of electron transport chain intermediate substrates); (3) mitochondrial network dynamics (fusion, fission, motility, membrane lipid composition, swelling); (4) mitochondrial biogenesis and degradation; (5) cellular and mitochondrial microenvironment[22].

Oxidative phosphorylation efficiency and respiratory states

Oxidative phosphorylation efficiency is dependent on delivery of reducing equivalents into electron transport chain and on activities of participating enzymes or enzyme complexes. The optimal efficiency and flow ratios are determined by control of complex I (reflects integrated cellular pathway) and complex II (the predominantly tricarboxylic acid cycle pathway)[23]. Depletion of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates plays an important role in the oxidative phosphorylation flux control. In respirometric assays, supplies of complex I as well as complex II are required. Convergent electron input and reconstitution of the tricarboxylic acid are needed to achieve maximal respiration[24]. It is controlled also by the availability of adenosine-5’-diphosphate for the adenine nucleotide transporter in the inner mitochondrial membrane[25].

Complex I is suggested to be responsible for adaptive changes and physiological set up of oxidative phosphorylation efficiency[8]. The stoichiometric efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation is defined by the phosphorylation, or the amount of inorganic phosphate (Pi) incorporated into adenosine-5’-triphosphate per amount of consumed oxygen. Phosphorylation was analyzed in rat brain, liver and heart mitochondria. There were found tissue-specific differences and dependency of the phosphorylation on the respiratory rates with complex I, but without complex II substrates[8]. A metabolic control analysis, which compared electron transport chain activities and oxygen consumption rates, determined the role of complex I in rat brain synaptosomes. Results of the study suggested complex I as rate-limiting for oxygen consumption and responsible for high level of control over mitochondrial bioenergetics[26].

As mentioned above, mitochondria exhibit transmembrane potential across the inner membrane that is necessary for oxidative phosphorylation. Protons are transported outwardly and create proton motive force (Δp), which consists of an electrical part Δψm (mitochondrial membrane potential, negative inside) and a chemical part ΔpH[27,28]. In mitochondria, the Δp is made up of the Δψm mainly. The Δψm controls the ability of the mitochondria to generate adenosine-5’-triphosphate, generate reactive oxygen species and sequester Ca2+ entering the cell. The Δψm and adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthesis express a degree of coupling; optimal adenosine-5’- triphosphate synthesis requires Δψm values between the range −100 mV and −150 mV. These values are reached primarily by Δψm, which maintain at higher values (about −200 mV), and by secondary control mechanisms, which decrease the Δψm to lower levels[20]. Changes of Δψm influence permeability of biological membranes and reactive oxygen species production, Δψm above −150 mV leads to exponentially increased permeability as well as superoxide (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production[10]. Similarly, mitochondrial membranes increase exponentially their permeability for protons[20]. On the other hand, lower mitochondrial Δp and Δψm (e.g. caused by inhibition of respiratory chain) can result in hydrolysis of cytoplasmic adenosine-5’-triphosphate and slightly lower potential than that generated by the respiratory chain[29]. Therefore, Δψm is precisely controlled and can be regulated by various parameters.

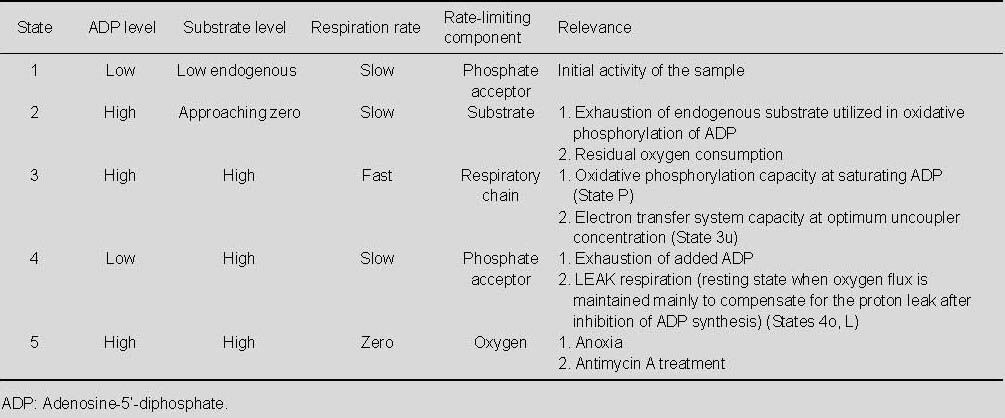

Adenosine-5’-triphosphate production is controlled by different mechanisms, depending on energy demands and thermogenesis[20]. The first mechanism of oxidative phosphorylation control has been called “respiratory control”, and is based on feedback mechanisms controlling the rate of adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthesis, first of all by Δp and Δψm. Higher levels of adenosine-5’-diphosphate in mitochondria lead to stimulation of adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase together with decrease of Δp. Originally, pilot studies of oxidative phosphorylation dynamics used the terminology of respiratory steady states, described by Chance and Williams[30]. Respiration was characterized by respiratory states (Table 1), by active state 3 (adenosine-5’-diphosphate stimulated) and followed by controlled state 4 (decrease after conversion of adenosine-5’-diphosphate to adenosine-5’-triphosphate)[30].

Table 1.

Decreased phosphorylation (caused mostly by increased Δp) leads to energy waste-proton leak (slip in cytochrome c oxidase), the decrease in the coupling, and increased thermogenesis[31]. However, conception of states had limited applicability in intact cells and in isolated mitochondria, did not include for instance cytochrome c oxidase, adenine nucleotide transporter, and extramitochondrial adenosine-5’-triphosphate/adenosine-5’-diphosphate ratio.

Secondary control of oxidative phosphorylation

Recently, primary control has been implemented by secondary control mechanisms that are Δp independent[16,32]. Mitochondrial Ca2+ levels have been included[33]. Ca2+ transport was presumed to be important only in buffering of cytosolic Ca2+ by acting as sink under conditions of Ca2+ overload. When the cytoplasmic Ca2+ level was overloaded, Ca2+ accumulated in mitochondrial matrix and utilized Δψm[30,34,35]. Nowadays it is considered that Ca2+ regulates activities of dehydrogenases via phosphorylation; adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthesis is switched on by 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate dependent phosphorylation and switched-off by calcium induced dephosphorylation[36].

In the tricarboxylic acid cycle, glycerophosphate dehydrogenase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase are influenced by Ca2+ levels and their phosphorylation leads to increased adenosine-5’-triphosphate production, production of glycogen, and glucose oxidation[35]. Reversible phosphorylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex mediated by calcium partly regulates the supply of reducing equivalents (oxidized to reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide ratio). Activation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle enhances the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide production that triggers movement of electrons down complexes I through to complex IV by initially donating of complex I[37].

Regulation of complex I and cytochrome c oxidase subunits via specific protein kinases and protein phosphatases was observed. 3’-5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate dependent protein kinases catalyze phosphorylation of complex I subunit and stimulate the electron transport chain[38]. At low Ca2+ levels, protein phosphatase dephosphorylates and inactivates complex I.

It is presumed that cytochrome c oxidase is regulated by allosteric inhibition of adenosine-5’-triphosphate at high adenosine-5’-triphosphate/adenosine-5’-diphosphate ratios[3]. Extramitochondrial adenosine-5’-triphosphate/adenosine-5’-diphosphate ratio regulates cytochrome c oxidase activity by binding to the cytosolic subunit of cytochrome c oxidase, whereas high mitochondrial adenosine-5’-triphosphate/adenosine-5’-diphosphate ratio causes exchange of adenosine-5’-triphosphate by adenosine-5’-diphosphate at cytochrome c oxidase and induce allosteric inhibition[39]. Similarly, increased intracellular Ca2+ levels are suggested to activate mitochondrial phosphatase, which dephosphorylates cytochrome c oxidase and turns off the allosteric inhibition[40]. This respiratory control by phosphorylated enzyme is assumed to keep the Δp low as prevention of increased Δp, which leads to the slip of protons in cytochrome c oxidase and decreased H+/e− stoichiometry[41,42]. However, in isolated mitochondria, high Δψm was measured even with high adenosine-5’-triphosphate/adenosine-5’-diphosphate ratio. The decrease was measured after addition of phosphoenolpyruvate and pyruvate kinase and could be explained as reversal of gluconeogenetic enzymes[24]. Under the physiological conditions, allosteric inhibition is modulated by increased Ca2+ levels, high substrate concentrations, and thyroid hormones. Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation induced by hormones results in loss of respiratory control by the adenosine-5’-triphosphate/adenosine-5’-diphosphate ratio, associated with the increased Δp and respiration[41].

Thyroid hormones, mainly triiodothyronine and diiodothyronine, have important effects on mitochondrial energetics and mitochondrial genome[43]. Mechanism of allosteric inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase has been closely linked to regulation by thyroid hormones. Diiodothyronine mediates short term effects of thyroid hormones and increases immediately basal metabolic rate. Diiodothyronine is formed by intracellular deiodination of triiodothyronine and binds to its specific binding sites, which were identified in the inner mitochondrial membrane[44]. This binding to subunit Va of cytochrome c oxidase abolishes the allosteric inhibition of respiration by adenosine-5’-triphosphate[45] that could result in partial uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation via increased Δψm, and continue to intrinsic uncoupling of cytochrome c oxidase by higher membrane potentials[16]. Therefore, thyroid hormones enhance the proton permeability; hyperthyroidism stimulated mitochondrial proton leak and adenosine-5’-triphosphate turnover in rat hepatocytes, where non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption remained unchanged[46,47]. Oppositely, in rat hypothyroid cells, significant decrease of non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption and proton leak were observed, and adenosine-5’-triphosphate turnover was unaffected[48].

Various physiological factors, such as sex steroid hormones, cytokines or neurotransmitters change the permeability of membranes[10,46]. Testosterone, dihydroxytestosterone, and progesterone increase the Δψm and lower the respiration rate. In study with isolated rat mitochondria, these hormones were added before or after addition of protonophores, and could reverse the protonophore-uncoupling effect[49]. Oppositely, female sex hormones did not show any recoupling effects. Differences in recoupling activity correlated with different hormone activity of steroids. Higher Δψm under the physiological conditions, requiring increased adenosine-5’-triphosphate utilization, can be explained by further decrease by adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase activity. A further decrease Δψm (lower than 120 mV) could not be sufficient for adenosine-5’-triphosphate production by adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase. This is nicely explained as changing of active and resting states of cells, which include resting periods with lower adenosine-5’-triphosphate utilization[10]. Large amount of stress factors (oxidative stress, irradiation, increased of cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels) cause transient increase of Δψm, i.e. they induce membrane hyperpolarization and lead to apoptosis[10].

PROTON PERMEABILITY OF MEMBRANES

Oxidative phosphorylation in cells is not fully efficient. Decrease of the proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane by “proton leak” causes uncoupling of fuel oxidation from adenosine-5’-triphosphate generation, and some energy is lost as heat. The mechanism of the basal proton conductance of mitochondria (insensitive to known activators and inhibitors) is not understood. There is a correlation between mitochondrial proton conductance and composition of inner membrane: phospholipid fatty acyl polyunsaturation correlates positively and monounsaturation correlates negatively with the proton conductance[50].

Uncoupling proteins and adenine nucleotide translocator are two types of mitochondrial carriers, which cause inhibitor-sensitive inducible proton conductance. Uncoupling proteins themselves do not contribute to the basal proton conductance of mitochondria; however, they are important metabolic regulators in permitting fat oxidation and in attenuating free radical production[51]. The amount of adenine nucleotide translocator present in the mitochondrial inner membrane strongly affects the basal proton conductance of the membrane and suggests that adenine nucleotide translocator is a major catalyst of the basal fatty-acid-independent proton leak in mitochondria[52].

Fatty acids

Long-chain fatty acids are weak acids that can cross the membrane in both protonated and deprotonated forms. Effects of fatty acids are interrelated to (1) increase uncoupling, (2) increase reactive oxygen species production, (3) opening mitochondrial permeability transition pores[53]. Further, they can modulate effects of thyroid hormones as well as sex steroid hormones[46].

Fatty acids can act as like classic oxidative phosphorylation uncouplers with protonophoric action on the inner mitochondrial membrane and/or interactions of fatty acids with adenosine-5’-diphosphate carrier, cytochrome c oxidase and adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase are presumed[54]. A recent study suggests that fatty acids are not only inducers of uncoupling, but they have also a regulatory function in this process. It supposes that transport of fatty acid anions participates in both adenosine-5’-diphosphate/adenosine-5’- triphosphate antiport and aspartate/glutamate antiport, at the same time[55]. On the other hand, studies using lipid membranes suppose that fatty acids are capable of spontaneous flip-flop[56]. Since fatty acids move across the membrane spontaneously and rapidly, no protein transporters are necessary. A study using pH gradient across the membranes showed rapid flip-flop of unionized fatty acids, whereas ionized fatty acids cross the membrane slowly[57]. In a study with proteoliposomes containing cytochrome c oxidase, a value of Δψm =−125 mV was obtained as a threshold, which induces fatty acids permeability[58]. Fatty acids were also suggested to exert coupling/uncoupling effects depending on their concentrations; submicromolar concentrations prefer coupling effects on respiratory chain complexes, whereas micromolar concentrations cause uncoupling[59].

Additionally, some fatty acid derivatives were found as unable to flip-flop and have been called inactive fatty acids. The inactivity was explained by their specific shapes that cause the inability to flip-flop[60].

Uncoupling proteins

Uncoupling diverts a significant proportion of energy to thermogenesis. Uncoupling proteins are mitochondrial carriers catalyzing a regulated proton leak across the inner membrane[61,62]. There are five types of uncoupling protein in mammals. Uncoupling protein1 (thermogenin) is presented exclusively in the inner mitochondrial membrane of brown adipose tissue, and its main function is to catalyze adaptive thermogenesis[63]. It can be stimulated by fatty acid and has synergic action of norepinephrine and thyroid hormones[16,64]. Concentrations of uncoupling protein 2 and uncoupling protein 3 in tissues are much lower than of uncoupling protein 1, and their functions are not exactly known. They probably contribute minimally to basal metabolic rate. uncoupling protein 2 is expressed ubiquitously in all human tissues, plays a regulative role in insulin release, immunity and neuroprotection; uncoupling protein 3 is expressed in skeletal muscles[65,66]. Other roles of uncoupling protein 2 and uncoupling protein 3 are control of adaptive thermogenesis, preventive action against oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species control, control of cellular energy balance, regulation of fatty acid oxidation and adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthesis[67,68]. They might be related to regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis, as regulators of Ca2+ uniporter[69]. Despite this prerequisite, in more recent study uncoupling protein 3 silencing did not alter Ca2+ uptake in permeabilized cells; in intact cells uncoupling protein 3 depletion reduced cytosolic Ca2+ levels and increased adenosine-5’-triphosphate production. This study suggested that uncoupling protein 3 does not affect mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, but modulates adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase of endoplasmic reticulum[70].

Uncoupling protein 2, uncoupling protein 4 and uncoupling protein 5 are present in the central nervous system; they have been suggested to have effects protecting neurons from the Ca2+ overload and/or oxidative stress[71,72]. Uncoupling protein 4 modulates neuronal energy metabolism, increases glucose uptake and glycolytic pathway of adenosine-5’-triphosphate formation. Further, it regulates Ca2+ homeostasis and influences influx of Ca2+ into endoplasmic reticulum[73]. Uncoupling protein 4 overexpression in SH-SY5Y cells increased adenosine-5’-triphosphate levels associated with increased respiratory rate[74]. Interestingly, cloned uncoupling protein 4 cDNA was widely expressed in areas with high-energy demands. Neurons expressing uncoupling protein 4 had lower Δψm, decreased accumulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ and lower reactive oxygen species production[71]. Uncoupling protein 5 has similar properties to uncoupling protein 4, but differs in enhancing mitochondrial properties. Overexpression of uncoupling protein 5 preserved adenosine-5’-triphosphate levels, maintained oxidative phosphorylation and attenuated reactive oxygen species production[72].

Homologues of uncoupling proteins have been identified with wide distribution[61]. Uncoupling protein 1 homologues might play a role in regulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, uncoupling protein 2 and uncoupling protein 3 homologues seem to be responsible for mitochondrial control depending on presence of oxidants[61,66].

Uncoupling protein activities can be positively or negatively regulated by different factors. Uncoupling proteins are stimulated by fatty acid and by reactive oxygen species, generated by as a side reaction between coenzyme Q10 and oxygen[65]. Uncoupling protein mediate the fatty acid dependent proton influx that leads to uncoupled adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthesis and heat production[75]. It is supposed that uncoupling protein and fatty acid decrease Δψm if it is sufficiently high. In planar membrane model, reconstituted with uncoupling protein and fatty acid, Δψm (similar to state 4) activated protonophoric function of uncoupling protein in presence of unsaturated fatty acid[76]. Two different models of the mechanism of uncoupling protein-mediated proton and anion uniport were proposed: (1) uncoupling proteins are direct proton uniporters and fatty acids only facilitate the proton uniport[77], (2) uncoupling proteins are pure anion uniporters and uncoupling is mediated by fatty acid cycling[78].

Inhibition of uncoupling protein was observed by purine nucleotides, very effective inhibition exhibit triphosphates, less effective monophosphates[79]. It is presumed that coenzyme Q10 redox state also influences the uncoupling protein inhibition; oxidized coenzyme Q10 does not affect uncoupling protein inhibition mediated by nucleotides[79]. Similarly, other studies with mitochondria confirmed that redox state of coenzyme Q10 could affect sensitivity of uncoupling protein to purine nucleotides[80]. Addition of reduced coenzyme Q10 increased proton conductance, whereas oxidized coenzyme Q10 decreased proton conductance. In spite of this, the redox state of endogenous coenzyme Q10 probably did not affect proton conductance in study with kidney mitochondria[81].

REACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES PRODUCTION

Reduction of O2 to water by aerobic respiration is accompanied by reactive intermediate formation. Generally, complex I and complex III are considered as the major O2•− sources[82]. Complex I releases O2•− to matrix, complex III can release O2•− to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane[83]. Additionally, other reactive oxygen species sources, e.g. monoamine oxidase, present in the outer mitochondrial membrane, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, the tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme complex, are able to generate H2O2. Monoamine oxidase catalyzes the oxidative deamination of biogenic and xenobiotic monoamines and increases the amount of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria. Hydrogen peroxide production by α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase is dependent on the ratio of oxidized to reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. Higher reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide leads to higher hydrogen peroxide production, therefore, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase could significantly contribute to oxidative stress in mitochondria[84].

Physiologically generated hydrogen peroxide and superoxide from electron transport chain are dependent on magnitude of Δp and respiratory state of mitochondria[85]. State 4 is characterized with high rate of reactive oxygen species production, contrary to state 3 with high rate of oxygen uptake and slow reactive oxygen species production. State 5, described as anoxic, with limited oxygen supply and lack of respiration produces minimum reactive oxygen species[86,87]. In isolated rat liver mitochondria, reactive oxygen species production and Δψm were studied in state 3 and state 4. These states attenuate Δψm and reactive oxygen species, correlation between reactive oxygen species and Δψm was observed[88]. However, this correlation with respiratory states was not observed in the study using isolated mitochondria, reactive oxygen species production correlated directly with Δψm[89].

Complex I is considered to be the primary source of reactive oxygen species in brain under physiological conditions as well as in pathological processes (e.g. neurodegenerative disorders). Reactive oxygen species seem to be the key factors in brain aging processes and mitochondrial respiration with reactive oxygen species production significantly contributes to functional changes in brain during aging. Study in isolated rat mitochondria found significantly increased hydrogen peroxide production and 30 % reduction of complex I activity in aged rats[90]. Defective mitochondria release large amounts of reactive oxygen species, similarly, decline of antioxidative enzyme activities (e.g. in elderly) enhances reactive oxygen species production[91]. Negative results of reactive oxygen species can affect respiratory chain: complexes I, III and IV seem to be the most affected, whereas function of complex II appears to be unchanged[92].

Integrity of inner mitochondrial membrane is necessary for function of electron transport chain and adenosine-5’-triphosphate production and is provided by a mitochondrial specific protein cardiolipin. Cardiolipin plays also an active role in mitochondrial mediated apoptosis, can be oxidized and interacts with cytochrome c and Bcl-2 proteins[93]. Nowadays, attention is paid to the reactive oxygen species-induced damage of electron transport chain complexes mediated by a peroxidation and oxidative damage of cardiolipin[94]. Diminished activities of complexes I and IV of electron transport chain lead to decreased rate of electron transfer and impaired mitochondrial function[95]. Both disturbed production and detoxification of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species participate on physiological effects of mitochondrial dysfunctions[96]. Reduction of oxygen to water by aerobic respiration is accompanied by reactive intermediate formation.

CONCLUSION

Regulation of cellular bioenergetics is crucial in processes of neuroplasticity. Oxidative phosphorylation is the most important source of adenosine-5’-triphosphate; its efficacy is determined by different mechanisms. Primary, the supply of substrates and Δψm were implemented by Ca2+ levels, reversible phosphorylation, allosteric inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation subunits, fatty acids and uncoupling protein, and influences of hormones. The system of oxidative phosphorylation does not respond to thermodynamic equilibrium, but embodies a rate of uncoupling. Lower Δψm can result in hydrolysis of cytoplasmic adenosine-5’-triphosphate; high Δψm leads to proton leak and increased uncoupling. Measurement of both respiration and membrane potential during action of appropriate endogenous and exogenous substances enables the identification of the primary sites of effectors and the distribution of control, allowing deeper quantitative analyses[97]. Better insight into molecular mechanisms of cellular respiration, control of oxidative phosphorylation and its roles in neuroplasticity likely better understand function, physiology as well as pathophysiology of various diseases.

Footnotes

Jana Hroudová, Ph.D.

Funding: This research was supported by grant No MSM0021620849 given by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, by project PRVOUK-P26/LF1/4 given by Charles University in Prague, by grant No. SVV-2012- 264514 from Charles University in Prague, and by grant No. 41310 given by the Grant Agency of Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic.

(Edited by Liu WJ/Song LP)

REFERENCES

- [1].Mattson MP, Partin J. Evidence for mitochondrial control of neuronal polarity. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56(1):8–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1<8::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Erecinska M, Cherian S, Silver IA. Energy metabolism in mammalian brain during development. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;73(6):397–445. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hroudová J, Fišar Z. Connectivity between mitochondrial functions and psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(2):130–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chada SR, Hollenberck PJ. Nerve growth factor signaling regulates motility and docking of axonal mitochondria. Curr Biol. 2004;14(14):1272–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chang DT, Reynolds IJ. Differences in mitochondrial movement and morphology in young and mature primary cortical neurons in culture. Neuroscience. 2006;141(2):727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cai Q, Sheng ZH. Mitochondrial transport and docking in axons. Exp Neurol. 2009;218(2):257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Overly CC, Rieff HI, Hollenberck PJ. Organelle motility and metabolism in axons vs dendrites of cultured hippocampal neurons. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 5):971–980. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cocco T, Pacelli C, Sgobbo P, et al. Control of oxidative phosphorylation efficiency by complex I in brain mitochondria. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(4):622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mattson MP, Gleichmann M, Cheng A. Mitochondria in neuroplasticity and neurological disorders. Neuron. 2008;60(5):748–766. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kadenbach B, Ramzan R, Wen L, et al. New extension of the Mitchell Theory for oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria of living organisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800(3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hirst J. Towards the molecular mechanism of respiratory complex I. Biochem J. 2009;425(2):327–339. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tomitsuka E, Kita K, Esumi H. Regulation of succinate-ubiquinone reductase and fumarate reductase activities in human complex II by phosphorylation of its flavoprotein subunit. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2009;85(7):258–265. doi: 10.2183/pjab.85.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Solmaz SR, Hunte C. Structure of complex III with bound cytochrome c in reduced state and definition of a minimal core interface for electron transfer. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(25):17542–17549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rodríguez-Hernández A, Cordero MD, Salviati L, et al. Coenzyme Q deficiency triggers mitochondria degradation by mitophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5(1):19–32. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.1.7174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, et al. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria. Central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(38):36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Trumpower BL. The protonmotive Q cycle. Energy transduction by coupling of proton translocation to electron transfer by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(20):11409–11412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 2003;552(Pt 2):335–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Noji H, Yoshida M. The rotary machine in the cell, adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(3):1665–1668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zanotti F, Gnoni A, Mangiullo R, et al. Effect of the ATPase inhibitor protein IF1 on H+ translocation in the mitochondrial adenosine-5’-triphosphate synthase complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kadenbach B. Intrinsic and extrinsic uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1604(2):77–94. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(03)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Papa S, Scacco S, Sardanelli AM, et al. Complex I and the cAMP cascade in human physiopathology. Biosci Rep. 2002;22(1):3–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1016004921277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Benard G, Bellance N, Jose C, et al. Multi-site control and regulation of mitochondrial energy production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(6-7):698–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cairns CB, Walther J, Harken AH, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation thermodynamic efficiencies reflect physiological organ roles. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(5 Pt 2):R1376–1383. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.5.R1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gnaiger E. Capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle: new perspectives of mitochondrial physiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(10):1837–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ramzan R, Staniek K, Kadenbach B, et al. Mitochondrial respiration and membrane potential are regulated by the allosteric adenosine-5’-triphosphate-inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(9):1672–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Telford JE, Kilbride SM, Davey GP. Complex I is rate-limiting for oxygen consumption in the nerve terminal. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(14):9109–9114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809101200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mitchell P. Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature. 1961;191:144–148. doi: 10.1038/191144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mitchell P. Chemiosmotic coupling in oxidative and photosynthetic phosphorylation. Biol Rev. 1966;41:445–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1966.tb01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nicholls DG, Vesce S, Kirk L, et al. Interactions between mitochondrial bioenergetics and cytoplasmic calcium in cultured cerebellar granule cells. Cell Calcium. 2003;34(4-5):407–424. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chance B, Williams GR. Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. III. The steady state. J Biol Chem. 1955;217(1):409–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mourier A, Devin A, Rigoulet M. Active proton leak in mitochondria: a new way to regulate substrate oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(2):255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Walsh C, Barrow S, Voronina S, et al. Modulation of calcium signalling by mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787(11):1374–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kadenbach B, Hüttemann M, Arnold S, et al. Mitochondrial energy metabolism is regulated via nuclear-coded subunits of cytochrome c oxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29(3-4):211–221. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].McCormack JG, Halestrap AP, Denton RM. Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiol Rev. 1990;70(2):391–425. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rizzuto R, Bernardi P, Pozzan T. Mitochondria as all-round players of the calcium game. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 1):37–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lee I, Bender E, Arnold S, et al. New control of mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species formation--a hypothesis. Biol Chem. 2001;382(12):1629–1636. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Viola HM, Hool LC. Qo site of mitochondrial complex III is the source of increased superoxide after transient exposure to hydrogen peroxide. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49(5):875–885. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Papa S, Scacco S, Sardanelli AM, et al. Complex I and the cAMP cascade in human physiopathology. Biosci Rep. 2002;22(1):3–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1016004921277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Napiwotzki J, Kadenbach B. Extramitochondrial adenosine- 5’-triphosphate/adenosine diphosphate-ratios regulate cytochrome c oxidase activity via binding to the cytosolic domain of subunit IV. Biol Chem. 1998;379(3):335–339. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee I, Bender E, Kadenbach B. Control of mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species formation by reversible phosphorylation of cytochrome c oxidase. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;234-235(1-2):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bender E, Kadenbach B. The allosteric adenosine-5’- triphosphate-inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase activity is reversibly switched on by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2000;466(1):130–134. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01773-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Arnold S, Kadenbach B. Cell respiration is controlled by adenosine-5’-triphosphate, an allosteric inhibitor of cytochrome-c oxidase. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249(1):350–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(2):139–170. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Goglia F, Moreno M, Lanni A. Action of thyroid hormones at the cellular level: the mitochondrial target. FEBS Lett. 1999;452(3):115–120. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Arnold S, Goglia F, Kadenbach B. 3,5-Diiodothyronine binds to subunit Va of cytochrome-c oxidase and abolishes the allosteric inhibition of respiration by adenosine-5’- triphosphate. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252(2):325–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Starkov AA. “Mild” uncoupling of mitochondria. Biosci Rep. 1997;17(3):273–279. doi: 10.1023/a:1027380527769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Harper ME, Brand MD. Hyperthyroidism stimulates mitochondrial proton leak and adenosine-5’-triphosphate turnover in rat hepatocytes but does not change the overall kinetics of substrate oxidation reactions. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1994;72(8):899–908. doi: 10.1139/y94-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Harper ME, Brand MD. The quantitative contributions of mitochondrial proton leak and adenosine-5’-triphosphate turnover reactions to the changed respiration rates of hepatocytes from rats of different thyroid status. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(20):14850–14860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Starkov AA, Simonyan RA, Dedukhova VI, et al. Regulation of the energy coupling in mitochondria by some steroid and thyroid hormones. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1318(1-2):173–183. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(96)00135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Brand MD, Turner N, Ocloo A, et al. Proton conductance and fatty acyl composition of liver mitochondria correlates with body mass in birds. Biochem J. 2003;376(Pt 3):741–748. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Azzu V, Jastroch M, Divakaruni AS, et al. The regulation and turnover of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(6-7):785–791. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Brand MD, Pakay JL, Ocloo A, et al. The basal proton conductance of mitochondria depends on adenine nucleotide translocase content. Biochem J. 2005;392(Pt 2):353–362. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Rial E, Rodríguez-Sánchez L, Gallardo-Vara E, et al. Lipotoxicity, fatty acid uncoupling and mitochondrial carrier function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(6-7):800–806. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wojtczak L, Schönfeld P. Effect of fatty acids on energy coupling processes in mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1183(1):41–57. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Samartsev VN, Marchik EI, Shamagulova LV. Free fatty acids as inducers and regulators of uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation in liver mitochondria with participation of adenosine diphosphate/adenosine- 5’-triphosphate- and aspartate/glutamate- antiporter. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2011;76(2):217–224. doi: 10.1134/s0006297911020088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kleinfeld AM, Chu P, Romero C. Transport of long-chain native fatty acids across lipid bilayer membranes indicates that transbilayer flip-flop is rate limiting. Biochemistry. 1997;36(46):14146–14158. doi: 10.1021/bi971440e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kamp F, Hamilton JA. pH gradients across phospholipid membranes caused by fast flip-flop of un-ionized fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89(23):11367–11370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Köhnke D, Ludwig B, Kadenbach B. A threshold membrane potential accounts for controversial effects of fatty acids on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 1993;336(1):90–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81616-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Di Paola M, Lorusso M. Interaction of free fatty acids with mitochondria: coupling, uncoupling and permeability transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757(9-10):1330–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Ježek P, Modrianský M, Garlid KD. Inactive fatty acids are unable to flip-flop across the lipid bilayer. FEBS Lett. 1997;408(2):161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hagen T, Vidal-Puig A. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins in human physiology and disease. Minerva Med. 2002;93(1):41–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Echtay KS, Roussel D, St-Pierre J, et al. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature. 2002;415(6867):96–99. doi: 10.1038/415096a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Brand MD, Affourtit C, Esteves TC, et al. Mitochondrial superoxide: production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37(6):755–767. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zaninovich AA. Role of uncoupling proteins uncoupling protein1, uncoupling protein2 and uncoupling protein3 in energy balance, type 2 diabetes and obesity. Synergism with the thyroid. Medicina (B Aires) 2005;65(2):163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Wolkow CA, Iser WB. Uncoupling protein homologs may provide a link between mitochondria, metabolism and lifespan. Ageing Res Rev. 2006;5(2):196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Pecqueur C, Couplan E, Bouillaud F, et al. Genetic and physiological analysis of the role of uncoupling proteins in human energy homeostasis. J Mol Med. 2001;79(1):48–56. doi: 10.1007/s001090000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Douette P, Sluse FE. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins: new insights from functional and proteomic studies. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40(7):1097–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Boss O, Hagen T, Lowell BB. Uncoupling proteins 2 and 3: potential regulators of mitochondrial energy metabolism. Diabetes. 2000;49(2):143–156. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Trenker M, Malli R, Fertschai I, et al. Uncoupling proteins 2 and 3 are fundamental for mitochondrial Ca2+ uniport. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(4):445–452. doi: 10.1038/ncb1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].De Marchi U, Castelbou C, Demaurex N. Uncoupling protein 3 modulates the activity of Sarco/ endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-adenosine-5’-triphosphatease (SERCA) by decreasing mitochondrial adenosine-5’-triphosphate production. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(37):32533–32541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Liu D, Chan SL, de Souza-Pinto NC, et al. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein4 mediates an adaptive shift in energy metabolism and increases the resistance of neurons to metabolic and oxidative stress. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8(3):389–414. doi: 10.1385/NMM:8:3:389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kwok KH, Ho PW, Chu AC, et al. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein5 is neuroprotective by preserving mitochondrial membrane potential, adenosine-5’-triphosphate levels, and reducing oxidative stress in MPP+ and dopamine toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(6):1023–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Beck V, Jabůrek M, Demina T, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids activate human uncoupling proteins 1 and 2 in planar lipid bilayers. FASEB J. 2007;21(4):1137–1144. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7489com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chan SL, Liu D, Kyriazis GA, et al. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein-4 regulates calcium homeostasis and sensitivity to store depletion-induced apoptosis in neural cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(49):37391–37403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Chu AC, Ho PW, Kwok KH, et al. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein4 attenuates MPP+ - and dopamine-induced oxidative stress, mitochondrial depolarization, and adenosine-5’-triphosphate deficiency in neurons and is interlinked with uncoupling protein2 expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(6):810–820. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Rupprecht A, Sokolenko EA, Beck V, et al. Role of the transmembrane potential in the membrane proton leak. Biophys J. 2010;98(8):1503–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Klingenberg M, Echtay KS. Uncoupling proteins: the issues from a biochemist point of view. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1504(1):128–143. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Ježek P, Jabùrek M, Garlid KD. Channel character of uncoupling protein-mediated transport. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(10):2135–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Woyda-Ploszczyca A, Jarmuszkiewicz W. Ubiquinol (QH2) functions as a negative regulator of purine nucleotide inhibition of Acanthamoeba castellanii mitochondrial uncoupling protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Swida A, Woyda-Ploszczyca A, Jarmuszkiewicz W. Redox state of quinone affects sensitivity of Acanthamoeba castellanii mitochondrial uncoupling protein to purine nucleotides. Biochem J. 2008;413(2):359–367. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Echtay KS, Brand MD. Coenzyme Q induces GDP-sensitive proton conductance in kidney mitochondria. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29(Pt 6):763–768. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Ježek P, Hlavatá L. Mitochondria in homeostasis of reactive oxygen species in cell, tissues, and organism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37(12):2478–2503. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Muller FL, Liu Y, Van Remmen H. Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):49064–49073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Generation of reactive oxygen species in the reaction catalyzed by á-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. J Neurosci. 2004;24(36):7771–7778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1842-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417(1):1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Brand MD, Affourtit C, Esteves TC, et al. Mitochondrial superoxide: production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37(6):755–767. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Cadenas E, Davies KL. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29(3-4):222–230. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Tirosh O, Aronis A, Melendez JA. Mitochondrial state 3 to 4 respiration transition during Fas-mediated apoptosis controls cellular redox balance and rate of cell death. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(8):1331–1334. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00481-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Aronis A, Melendez JA, Golan O, et al. Potentiation of Fas-mediated apoptosis by attenuated production of mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10(3):335–344. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Petrosillo G, Matera M, Casanova G, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in rat brain with aging Involvement of complex I, reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. Neurochem Int. 2008;53(5):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Schönfeld P, Wojtczak L. Fatty acids as modulators of the cellular production of reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(3):231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Boffoli D, Scacco SC, Vergari R, et al. Decline with age of the respiratory chain activity in human skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1226(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Yin H, Zhu M. Free radical oxidation of cardiolipin: chemical mechanisms, detection and implication in apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction and human diseases. Free Radic Res. 2012;46(8):959–974. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.676642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Musatov A, Robinson NC. Susceptibility of mitochondrial electron-transport complexes to oxidative damage. Focus on cytochrome c oxidase. Free Radic Res. 2012;46(11):1313–1326. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.717273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Navarro A, Boveris A. The mitochondrial energy transduction system and the aging process. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(2):C670–686. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00213.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Maes M, Fišar Z, Medina M, et al. New drug targets in depression: inflammatory, cell-mediated immune, oxidative and nitrosative stress, mitochondrial, antioxidant, and neuroprogressive pathways. And new drug candidates-Nrf2 activators and GSK-3 inhibitors. Inflammopharmacology. 2012;20(3):127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10787-011-0111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 2011;435(2):297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]