Abstract

While much prior research has documented the negative associations between aggression, peer relationships, and social skills, other research has begun to examine whether forms of aggression also may be associated with prosocial skills and increased social status. However, few studies have examined these associations within diverse samples of elementary aged youth. The current study examined the associations between aggression, popularity, social preference, and leadership among 227 urban, ethnic minority (74 % African American, 9 % bi-racial including African American, 12 % other ethnic minorities, and 5 % European American) elementary school youth (average age 9.5 years, 48.5 % female). Results indicated that in an urban, high risk environment, displaying aggressive behaviors was associated with increased perceived popularity, decreased social preference, and, in some cases, increased perceived leadership. The results also suggested gender differences in the association between the forms of aggression (i.e. relational and overt) and popularity. The current study underscores the importance of examining youth leadership along with forms of aggression and social status among urban minority youth. Implications for future research and aggression prevention programming are highlighted.

Keywords: Relational aggression, Popularity, Social preference, Leadership, Social status, Gender

Introduction

The association between aggressive behavior and negative comorbidities has long been established; aggressive youth have poorer social skills, social problem-solving deficits, emotional arousal difficulties, academic difficulties, and higher levels of internalizing and externalizing behaviors than their non-aggressive peers (e.g., Fontaine et al. 2009; Martino et al. 2008). This association is found for both overt (verbal insults, name-calling, hitting or kicking) and more covert forms of aggression, yet the association is more robust for overt aggression. In contrast, relational aggression, often a covert form of aggression and defined as behaviors that are used with the intent to cause harm through non-physical means such as social exclusion, rumor spreading, or damaging of relationships (e.g., Archer and Coyne 2005; Crick 1996), has been associated with certain prosocial skills and increased social standing, such as perceived popularity (e.g., Cillessen and Mayeux 2004; Hoff et al. 2009; Puckett et al. 2008). To date, however, much of the research in this area has focused on Caucasian, middle class, adolescent samples (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011).

The few studies that have focused on minority youth evinced noteworthy results, suggesting that this line of research is especially important within ethnically and socioeconomically diverse samples of youth. For instance, the association between aggression and popularity may be even stronger for minority youth (Rodkin et al. 2000; Xie et al. 2003). These popular and aggressive youth also may have certain prosocial skills, such as peer leadership, that not only affords them high visibility among peers, but also increases their ability to influence their peer groups; yet, there is a dearth of literature examining this phenomenon among urban minority elementary aged youth. As such, there is a clear need to better understand the relationships between aggression, leadership, and social status within this high risk population. The purpose of the current study is to extend prior research on aggression, social status and leadership within an urban, elementary aged (3rd and 4th grade) sample.

Social Status

In order to understand children’s position and social standing in their peer group, sociometric status is used to examine how well a child is liked or disliked by peers (Coie et al. 1982). The current study focused on two aspects of sociometric status, social preference and popularity. Through a peer nomination procedure in which students nominate the classmates they like the most and the classmates they like the least, children are classified as either rejected (low on “liked most,” high on “liked least”), controversial (high on “liked most,” high on “liked least”), neglected (low on “liked most,” low on “liked least”), sociometrically popular (high on “liked most,” low on “liked least”) or average (roughly equal on “liked most” and “liked least” nominations; Coie et al. 1982). Studies with 3rd–8th grade predominantly white youth suggest that sociometrically popular youth exhibit higher levels of prosocial behavior (e.g., leadership skills, social skills) and cognitive abilities, yet these same studies found associations between sociometric popularity and the use of overly assertive and aggressive behaviors (Coie et al. 1983; Newcomb et al. 1993). As such, scholars realized a need to examine the heterogeneity that exists among youth who are identified as popular. Thus, researchers started to look at another dimension of popularity besides the standard sociometric definition, namely perceived popularity.

Assessments of perceived popularity are obtained by asking youth to nominate class- or grade-mates they consider to be popular, rather than who they like or dislike. Therefore, perceived popularity is a measure of one’s reputation for being popular (LaFontana and Cillessen 2002), while sociometric popularity is a measure of one’s likeability. Sociometrically popular youth also have been called socially preferred (Coie et al. 1982; LaFontana and Cillessen 2002; Terry and Coie 1991) and we will refer to this group of children as socially preferred in this manuscript in order to distinguish it from perceived popularity, which we will refer to as popularity. Researchers of predominantly white middle and high school youth have found clear evidence that social preference and popularity are correlated only moderately and each are associated with unique behaviors (e.g., Mayeux et al. 2008; Puckett et al. 2008). More specifically, adolescent youth who are identified as popular are not always identified as socially preferred (Mayeux et al. 2008; Vaillancourt and Hymel 2006), yet popular adolescents are more socially influential among their peers than those who are socially preferred (Ellis and Zarbatany 2007; van de Schoot et al. 2010). Therefore, these popular youth are in a position to influence the vast majority of peers, if these youth are aggressive, this can negatively impact the social climate of the school.

Aggression and Social Status

Research of predominantly white middle and high school youth suggests a link between the use of aggression and the attainment of higher social status (Mayeux et al. 2008; Vaillancourt and Hymel 2006). In fact, recent research indicates that aggressive youth tend to obtain higher social status, and that this relationship is especially strong during late childhood and early adolescence (e.g., Cillessen and Borch 2006; LaFontana and Cillessen 2002; Pellegrini and Long 2002). Studies of middle and high school predominantly white youth suggest that the most popular youth tend to display the highest levels of overt and relational aggression (e.g., Hoff et al. 2009). Across ethnicities and SES (e.g., Cillessen and Mayeux 2004; Farmer and Xie 2007), relational forms of aggression appear to be particularly important for attaining and maintaining a high social status during late childhood and early adolescence.

Another difference in the association between popularity and the use of different types of aggression is related to gender. For example, Mayeux et al. (2008) found that, among a sample of predominantly white middle school youth, being well liked was associated with popularity during high school for boys, but for girls, being popular leads one to be less well liked over time. The authors suggest that this may be due in part to the relationally aggressive behaviors that these girls often utilize. On the other hand, other studies have found different outcomes related to gender, popularity, and relational aggression. Specifically, in a sample of predominantly white adolescent youth, being a relationally aggressive, popular boy was strongly associated with being disliked, which could be due to the reliance upon a gender non-normative expression of aggression (Crick 1997). For girls of varying ages, however, high levels of relational aggression and popularity were not associated with being disliked (Robertson et al. 2010; Vaillancourt and Hymel 2006). It is clear that additional studies are needed to examine possible gender differences as these differences may influence how best to intervene with aggressive behaviors.

Social dominance theory suggests that there are complex associations between relational aggression and the attainment of higher social status (Hawley 1999; Neal 2010; Walcott et al. 2008), such that those who utilize relational aggression successfully to obtain higher social status and prominence in the peer group do so at a cost of having few high quality friendships. Additionally, for the victims of aggression, when the perpetrator is also perceived as popular, this not only more negatively impacts the victim’s social and emotional adjustment (Garandeau et al. 2010), but also impacts how likely other individuals are to intervene as a witness to the behavior (Waasdorp et al. 2011). Youth who are popular are more socially influential among their peers than those who are not popular and are even more influential than those who are socially preferred (Ellis and Zarbatany 2007; van de Schoot et al. 2010). Therefore, if these popular youth are aggressive they have the greatest potential to strongly influence the social climate of the school. Given the association may be particularity strong during late childhood and early adolescence (e.g., Cillessen and Borch 2006; LaFontana and Cillessen 2002; Pellegrini and Long 2002), studies should examine this phenomenon during the elementary school years before the behavior is at its highest.

Aggression, Social Status, and Leadership

Research suggests that aggressive youth are not only considered popular in many cases, but they also may possess positive qualities such as being perceived as leaders. In fact, studies of predominantly white adolescents indicate that these positive leadership qualities may actually help facilitate their attainment of the higher social status and social influence (Mayeux et al. 2008; Vaillancourt et al. 2007). This finding has implications for identifying and intervening with aggressive youth. First, for these youth, the aggressive behavior is often successful in attaining status; consequently youth may continue this reinforced pattern of behavior over time, even given the simultaneous negative consequences (e.g., fewer close friends). Also, if other youth want to emulate the behaviors of those they perceive as popular leaders, they too may engage in more frequent aggression to manipulate their peer group social standing. In both cases, the use of aggression is perpetuated. Second, the additive impact of having leadership skills in conjunction with aggressive behaviors may mean that youth are even more influential than those without leadership skills. Finally, due to desirable qualities such as leadership skills, teachers may not be as adept at identifying (Leff 2007; Puckett et al. 2008; Vaillancourt et al. 2007) and therefore intervening with relationally aggressive, yet socially prominent, youth. Clearly, there is a need to further examine the associations between aggression, leadership, and popularity, and to translate these findings into applied strategies for identification of and intervention with aggressive youth.

Importance of this Research with Urban African American Youth

Much of the extant research presented thus far has examined the phenomenon of social status and aggression among predominantly white, middle class samples. Because it was thought that relational aggression was more common among white, middle class girls, researchers know less about how boys use relational aggression. However, recent studies also underscore the importance of examining relational aggression among an urban, ethnic minority population, as not only do both boys and girls find this behavior emotionally taxing (Waasdorp et al. 2010), but the behavior is also known to quickly escalate to overt aggression (Farrell et al. 2007; Talbott et al. 2002). Additionally, both overtly and relationally aggressive behaviors are of particular concern in urban schools (Leff el al. 2009, 2010b), as these children are already at an increased risk of experiencing emotional and behavioral problems due to chronic stressors such as high levels of poverty and exposure to community violence (Black and Krishnakumar 1998; Guerra et al. 2003; Morales and Guerra 2006). Thus, research focused on white, middle class youth are not necessarily able to provide information related to the aggression for urban, ethnic minority youth.

The few studies of African American youth indicate a strong association between the use of overt aggression and relational aggression (Garandeau et al. 2010; Parkhurst and Hopmeyer 1998; Xie et al. 2003), as well as a clear association between popularity and aggression among adolescent youth (Farmer et al. 2003; Luthar and McMahon 1996). Studies across ethnic and socioeconomic groups show that youth who are aggressive and popular are also more likely to have negative academic and behavioral outcomes, such as increased school absences and low achievement (e.g., Schwartz et al. 2008; Troop-Gordon et al. 2011; Wilson et al. 2011), and this association may be particularly strong among inner city African American youth, and possibly even stronger for African American girls (Kiefer and Ryan 2008). This suggests that it is important to examine this phenomenon early in the academic careers of inner-city, minority youth. Further, as suggested by the gender non-normative theory of aggression (Crick 1997) there also may be gender differences among African American youth such that there is an association between overt aggression and perceived popularity for boys, but for girls the association may be more likely between relational aggression and perceived popularity (Xie et al. 2003). Additional studies with elementary aged, ethnic minority youth are needed to corroborate these findings related to popularity.

Studies have shown that having leadership skills is an important buffer against negative outcomes for minority youth (e.g., Shelton 2009; Teasley et al. 2007). Although for white middle class youth, leadership ability may contribute to attaining higher social status and social influence (Mayeux et al. 2008; Vaillancourt et al. 2007), research examining popularity and aggression as they relate to leadership among urban youth is scarce (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011). Moreover, studies that examine leadership in conjunction with aggressive behaviors and social status specifically among elementary aged youth are needed as this is an important period for early intervention and prevention given that aggression begins to increase in late childhood and peaks in middle school (e.g., Card et al. 2008) as does the importance of social status. Having leadership skills yet also having high levels of aggression provides an avenue for early aggression intervention and prevention programming that could help these influential youth to display leadership in positive ways (Leff et al. 2010a).

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study was to build upon prior gaps in the literature through examining aggression, popularity, and leadership among inner-city predominantly African American third and fourth grade youth. Specifically, the first aim of this article was to better understand how aggression is associated with social status (e.g., popularity and social preference) among minority youth. We hypothesized that similar to prior research with predominantly white middle-class youth, relational aggression would be associated positively with popularity and negatively associated with social preference. However, given this sample of high risk inner-city youth, we examined both overt aggression and relational aggression in order to better understand how both forms of aggression are associated with social status. In line with the gender non-normative theory of aggression (Crick 1997) and studies of minority youth (Xie et al. 2003), it was expected that the association between the form of aggression and social status would likely vary by gender, such that children who display more aggression atypical for their gender (e.g., boys who display higher levels relational aggression and girls who display higher levels of overt aggression) would be perceived as less popular and less socially preferred than those who display gender-typical forms of aggression.

Given the paucity of research on relational aggression and leadership among minority elementary aged youth, a second aim was to examine the association between leadership and relational aggression while controlling for the effects of social status. Although no hypotheses were made, given the high correlation between leadership and popularity, we expected that being perceived as a leader may be associated with increased relational aggression. As interventions including a leadership building component have shown promise for reducing relational aggression for inner-city girls (Leff et al. 2009, 2010a), better understanding of the relationship between leadership, social status, and aggression for both genders can help inform aggression intervention development.

Method

Participants

Data utilized for this study were collected as part of a preliminary trial of a school-based universal aggression prevention program called The Preventing Relational Aggression in School Everyday (PRAISE; Leff et al. 2010b) Program in the Philadelphia school district. On average, 84 % of youth in this school district are below the national poverty line. Data for the current study were collected before PRAISE was implemented. All students across ten 3rd and 4th grade classrooms within one large urban elementary school (n = 290) were given the opportunity to participate, resulting in 227 (78 %) youth providing assent and parent permission. The participating sample was comprised of 48.5 % girls (n = 110) and 51.5 % boys (n = 117). On average, youth were aged 113.2 months (SD = 10.5). Seventy-four percent of the sample was African American, 9 % were bi-racial including African American, 5 % were European American, and 12 % included other ethnic minorities (e.g., Asian, Native American, Hispanic/Latino/Latina).

Measures and Procedures

A peer nomination procedure developed by Crick and Grotpeter (1995) was used to assess each child’s level of aggressive behavior, social status, and leadership. This procedure for identifying youth was selected based on several investigations demonstrating strong correlations between peer nomination methods and teacher report indices of behavior for African American youth (e.g., Coie and Dodge 1988; Hudley 1993).

The peer nomination procedure involves participating students nominating others within their grade that they felt met certain behavioral descriptions. Youth were given a roster of names from all students in their grade, and were allowed to nominate as many youth as they desire per item. An unlimited peer nomination procedure was selected, given research indicating that this approach demonstrates slightly stronger psychometric properties than the traditional limited nomination procedure (e.g., Terry 2000).

There were two subscales of aggression, five items for relational aggression (e.g., “tell their friends that they will stop liking them unless their friends do what they say,” “ignore or stop talking to others when they get mad at them,” “try to make other kids not like a certain person by spreading rumors about them or talking behind their backs”) and three items for overt aggression (i.e., who hit or push others, who start fights, who yell and call others mean names) (Crick and Grotpeter 1995; Leff et al. 2009). Each item has been associated with stability, concurrent and predictive validity, and test–retest reliability across diverse samples (e.g., Crick and Grotpeter 1995; Olweus 1991; Kupersmidt et al. 1990). Moreover, several investigations have demonstrated strong correlations between peer nomination methods and teacher report indices of behavior for African American youth (e.g., Coie and Dodge 1988; Hudley 1993). Social preference was assessed by an item asking youth to nominate peers they like the most and another item asking for nominations of peers they like the least. Subsequently, the “like most” item was subtracted from the “like least” item. The perceived popularity item asked youth to nominate peers who are “popular, well-known, and have a lot of friends.” Finally, leadership was assessed by asking youth to nominate those who “lead peer group activities or games.” Raw score nominations on the items corresponding to the relational and overt subscales, as well as the popularity and leadership indices were standardized within each grade (the nominating group), resulting in z-scores for relational aggression, overt aggression, social preference, perceived popularity, and leadership for each child, with higher scores indicating more nominations for that behavior.

Analytic Approach

First, descriptive statistics were evaluated and bivariate associations among and between types of aggression (e.g., relational and overt) and social status variables (e.g., leadership, perceived popularity, and social preference) were estimated using correlations. All relationships were also examined for differences between genders.

Next, to examine the first aim, two hierarchical multiple regressions were performed separately to investigate the relationships between aggression and social status. Each regression predicted one of the social status variables, and the first step of the model included gender and the other social status variable (i.e., controlling for social preference when predicting popularity and controlling for popularity when predicting social preference). Analyses were conducted in this way because the literature indicates a strong connection between popularity and social preference (e.g., Newcomb et al. 1993), suggesting the importance of controlling for one construct while assessing the other. Overt aggression was entered in the second step, and relational aggression was entered in the third step in order to examine the unique association of relational aggression with the outcome over and above overt aggression. The final step included the two gender by aggression interaction terms.

For aim two, similar to the analytic approach presented for aim one, the first step of the regression model included gender, yet in this model both perceived popularity and social preference were included simultaneously. Next, overt aggression was entered in the second step, relational aggression in the third, and the two gender by aggression interaction terms in the fourth step. Standardized regression coefficients are reported for all models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Preliminary analyses were conducted to examine the skew and kurtosis of study variables and indicated that non-normality was not a problem given that the skew was less than three and kurtosis was less than four (Kline 1998). Due to concerns about the high correlation between the forms of aggression, we examined the potential for collinearity; both the variance inflation factor (VIF; all < 10) and tolerance (all > .10) indicated that multicollinearity was not a concern. Moreover, sensitivity analyses (e.g., switching the order of entering the forms of aggression) were conducted and this too indicated no concerns for collinearity.

Bivariate Associations

Peer-nominated relationally aggressive youth were also likely to be rated as overtly aggressive (rs = .82–.88, ps < .001); this finding was particularly true for boys (t(225) = −6.04, p < .001; see Table 1). Within gender differences revealed that girls were more likely to be rated as relationally aggressive as compared to overtly aggressive, t(113) = −3.61, p < .001; while boys were more likely to be rated as overtly aggressive as compared to relationally aggressive, t(109) = −6.27, p < .001. The three variables of interest (social preference, perceived popularity, and leadership) were also moderately to strongly positively related (rs = .43–.88, ps < .001), with the strongest relationships between leadership and popularity (rs = .80–.88, ps < .001). That is, youth who were rated by their peers as leaders were also more likely to be rated as popular and socially preferred. Comparisons between genders revealed that girls were more likely than boys to be nominated as leaders (t(225) = 5.09, p < .001), popular (t(225) = 4.09, p < .001), and socially preferred (t(225) = 5.95, p < .001).

Table 1.

Correlations means and standard deviations by gender

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Boys M (SD) | Girls M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relational aggression | – | .82* | .41* | .49* | −.13 | .04 (.96) | −.06 (.92) |

| 2. Overt aggression | .88* | – | .15 | .23* | −.35* | .30 (1.05) | −.39 (.59) |

| 3. Leadership | .48* | .41* | – | .88* | .60* | −.24 (.78) | .41 (1.12) |

| 4. Popularity | .43* | .33* | .80* | – | .54* | −.3 (.68) | .45 (1.19) |

| 5. Social preference | −.12 | −.17 | .43* | .52* | – | −.25 (1.4) | .54 (1.51) |

Correlations for females (n = 110) are above the diagonal, correlations for males (n = 117) are below the diagonal

When comparing relationships between aggression type and social status, several patterns related to gender became clear. First, both boys and girls who were rated by their peers as being more aggressive were also more likely to be rated as being leaders and being popular. For relational aggression, these relationships were moderate for both genders (rs = .41–.49, ps < .001). For overt aggression, these relationships were moderate for boys (rs = .33–.41, ps < .001), but small for girls (rleadership = .15, p = ns; rpopularity = .23, p < .05). Second, regardless of gender, inverse relationships were found between aggression and peer-reported social preference, though these relationships were for the most part statistically non-significant. Differences in the magnitude of the relationships between aggression type and social status by gender suggest that gender may moderate these relationships.

Aim 1: Perceived Popularity and Social Preference

The associations between aggression, perceived popularity, and social preference were examined using hierarchical linear multiple regressions. The model predicting perceived popularity included social preference as a control, while the model predicting social preference included perceived popularity as a control.

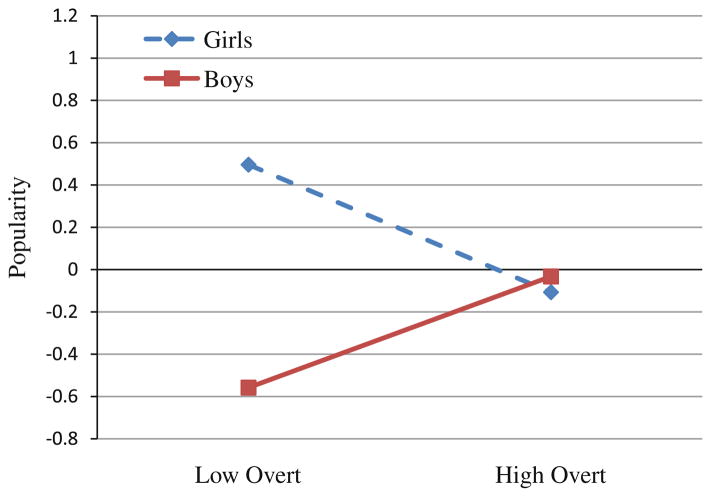

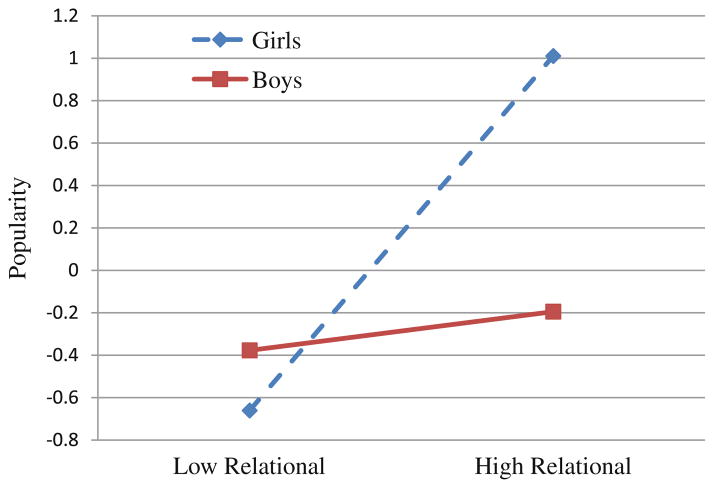

The overall model predicting perceived popularity was significant and explained 63 % of the variance (see Table 2, Model One). Gender was negatively associated with perceived popularity, indicating that, controlling for the other variables in the model, girls were rated as more popular than boys. The addition of overt aggression, F(3, 226) = 79.19, p < .001; ΔR2 = .15, p < .001, and relational aggression, F(4, 226) = 83.35, p < .001; ΔR2 = .08, p < .001, resulted in a significant improvement of fit; in both cases, children perceived by their peers as being most aggressive were also perceived as more popular. Notably, while overt aggression was significant in Step 2, the inclusion of relational aggression resulted in overt aggression no longer being significantly associated with popularity. Finally, gender moderated the relationship between aggression and perceived popularity, and adding the gender by aggression interaction terms to the model significantly improved fit, F(6, 226) = 64.90, p < .001; ΔR2 = .04, p < .001. Specifically, controlling for the other covariates, girls who were rated as being more overtly aggressive were perceived as less popular, while the opposite was true for boys, such that boys who were rated as more overtly aggressive were perceived as more popular (see Fig. 1). In contrast, controlling for other variables, girls who were rated as more relationally aggressive were also perceived as more popular, while relational aggression is not as strongly related to perceived popularity for boys (see Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression predicting popularity and social preference by gender, overt and relational aggression, and gender by aggression interactions

| Variable | Model one: popularity

|

Model two: social preference

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | R2Δ | β | R2Δ | |

| Step 1 | .37* | .32* | ||

| Controla | .50* | .54* | ||

| Gender | −.23* | − .06 | ||

| Step 2 | .15* | .14* | ||

| Control | .59* | .66* | ||

| Gender | −.37* | .14* | ||

| Overt | .43* | − .43* | ||

| Step 3 | .08* | .02* | ||

| Control | .56* | .73* | ||

| Gender | −.23* | .10 | ||

| Overt | −.06 | − .20* | ||

| Relational | .53* | − .27* | ||

| Step 4 | .04* | .04* | ||

| Control | .55* | .74* | ||

| Gender | −.23* | .18* | ||

| Overt | −.29 | − .49* | ||

| Relational | .81* | − .30* | ||

| Gender × OA | .45* | .15 | ||

| Gender × RA | −.53* | .21 | ||

| Total adjusted R2 | .63* | .50* | ||

In the popularity model, social preference was included as a control, in the social preference model, popularity was included as a control

p < .05

Fig. 1.

Overt aggression and popularity by gender (high overt = 1 SD above the mean; low overt = 1 SD below the mean)

Fig. 2.

Relational aggression and popularity by gender (high relational = 1 SD above the mean; low relational = 1 SD below the mean)

The overall model predicting social preference was also significant and explained 50 % of the variance (see Table 2, Model Two). The addition of overt aggression, F(3, 226) = 63.60, p < .001; ΔR2 = .14, p < .001, and relational aggression, F(4, 226) = 51.29, p < .001; ΔR2 = .02, p < .001, resulted in significant improvements of fit. Controlling for other variables, children rated highly in either type of aggression were likely to be less socially preferred by their peers. In the final model, gender was significantly positively associated with social preference, indicating that, controlling for other variables in the model, boys were more likely to be socially preferred than girls. Though the addition of the gender by aggression interactions to the model did significantly improve the fit, F(6, 226) = 39.04, p < .001; ΔR2 = .04, p < .001, gender did not significantly moderate the relationship between aggression and social preference.

Aim 2: Leadership

We examined the relationship between aggression and leadership controlling for both perceived popularity and social preference. The overall model was significant and explained 78 % of the variance (see Table 3, Model Three). Children who were perceived as popular (b = .73) as well as socially preferred children (b = .15) were more likely to be rated as leaders. While the addition of overt aggression, F(4, 226) = 187.20, p < .001; ΔR2 = .01, p < .001, and relational aggression, F(5, 226) = 156.17, p < .001; ΔR2 = .01 p < .001, resulted in significant improvements of fit, once relational aggression (b = .18) was included in the model, overt aggression was no longer significant. Thus, controlling for other variables, children rated highly in relational aggression were more likely to be perceived as leaders by their peers.1

Table 3.

Hierarchical regressions predicting leadership from popularity, social preference, gender, overt and relational aggression, and gender by aggression interactions

| Variable | Model three: leadership

|

|

|---|---|---|

| β | R2Δ | |

| Step 1 | .77* | |

| Popularity | .80* | |

| Social preference | .11* | |

| Gender | .002 | |

| Step 2 | .01* | |

| Popularity | .76* | |

| Social preference | .16* | |

| Gender | −.04 | |

| Overt | .09* | |

| Step 3 | .01* | |

| Popularity | .70* | |

| Social preference | .18* | |

| Gender | −.01 | |

| Overt | −.05 | |

| Relational | .18* | |

| Step 4 | .01 | |

| Popularity | .73* | |

| Social preference | .15* | |

| Gender | −.02 | |

| Overt | −.11 | |

| Relational | .13 | |

| Gender × overt | −.01 | |

| Gender × relational | .12 | |

| Total adjusted R2 | .78* | |

p < .05

Discussion

Although research that examines aggression, popularity, and social preference is steadily increasing, few studies examine this phenomenon among elementary aged urban minority youth. Further, studies suggest that both popularity and aggressive behavior are associated with negative outcomes (e.g., Troop-Gordon et al. 2011); however, being a leader among peers has been shown to be protective against negative outcomes especially for minority youth (e.g., Shelton 2009). The goal of the current study was to better understand how aggression is associated with social status (e.g., popularity and social preference) among elementary aged minority youth and to examine leadership ability as it relates to popularity, social preference, and aggression. As hypothesized in an urban high risk environment, displaying aggressive behaviors in early elementary school was related generally to having a higher social status, and the results also demonstrated that displaying relationally aggressive behaviors was associated with being viewed as a leader as early as third grade among minority youth.

Similar to prior research (e.g., Hoff et al. 2009; Neal 2010; Walcott et al. 2008), our results indicated that in general, more aggressive children were perceived as more popular by their peers. However, the results suggested this association between aggression and popularity varied by the form of aggression such that the association between overt aggression and popularity is no longer significant once levels of relational aggression are taken into account. Our results build upon studies of middle class, white adolescent youth (e.g., Vaillancourt and Hymel 2006) by illustrating that displaying either relational or overt aggression resulted in lower social preference. This finding was robust across gender for this ethnically diverse elementary aged sample. Although aggressive children, especially those who use relational aggression, have some influence over their peers, they are not necessarily well-liked. Further, our results add to prior research indicating that in urban environments, even 3rd and 4th grade boys and girls may use relational aggression to selectively exclude others, which could serve to influence who belongs in the popular crowd and keep out those who threaten their social status. Engaging in other relationally aggressive behaviors such as spreading rumors may provide some anonymity and could harm peers while hiding the appearance of being mean (e.g., Cillessen and Rose 2005).

The results also suggest a gender difference in the association between aggression and popularity. Specifically, high levels of overt aggression were associated with less popularity for girls and increased popularity for boys. In contrast, high levels of relational aggression were associated with increased popularity for girls but were not related strongly to perceived popularity for boys. This finding provides further evidence that among urban minority youth, the association between aggression and popularity varies by gender (e.g., Farmer et al. 2003; Kiefer and Ryan 2008; Xie et al. 2003, 2006) and that this association can be seen as early as 3rd grade. Prior research suggests that socially deviant behavior is associated with being popular for African American boys, and overt aggression is more likely to be associated with a socially influential/dominant position among boys (Farmer et al. 2003; Xie et al. 2006). Moreover, African American males may strive for social dominance through asserting themselves and gaining control in a school setting by instilling fear and compliance (Kiefer and Ryan 2008; Neal 2010); as such, being overtly aggressive may afford them a socially prominent position. Taken with our current findings on leadership, if these boys are perceived as leaders, they can influence the broader peer culture, creating a climate where overtly aggressive behavior is perpetuated and condoned (Xie et al. 2006). In contrast, relational aggression in girls also may be perpetuated and condoned (Xie et al. 2006) due to the high social impact and perceived leadership abilities that the popular relationally aggressive girls utilize.

Farmer and Xie (2007) suggest that there are two social worlds for aggressors, one in which aggressive youth are socially marginalized, and the other in which aggressive youth are influential and central members of the social network who systematically utilize both aggressive and prosocial strategies to maintain their social prominence. Aggression alone may not be sufficient for obtaining popularity (Vaillancourt and Hymel 2006), as there may be certain skills such as leadership skills, that afford the aggressive youth high social status or prominence. As demonstrated in the current study, among urban youth as early as the third grade, aggressive popular youth are often perceived as leaders, therefore, placing them in a particularly influential position where they can impact both the peer culture and classroom environment (Farmer and Xie 2007).

Our results indicate that perceived popularity and social preference are strongly and positively associated with leadership. In addition, including relational aggression in the model suggested that children who specifically display this type of behavior (as opposed to overt aggression) were more likely to be perceived as leaders by their peers. While popular youth were more likely to be seen as leaders, the results indicate that popular youth who display relational aggression are even more likely to be perceived as leaders. Therefore, findings from the current study further support the importance of understanding the association between popularity and aggression, and underscore the salience of examining youth leadership among elementary aged minority youth, especially given that the school social environment is often impacted by those who are highly influential and social leaders (Waasdorp et al. 2011). These aggressive popular youth may be viewed in social positions that others may want to emulate, especially during early adolescence when social status is increasingly salient (Ladd 2005). Further, in line with social learning theory (Bandura 1973), if these high status youth are aggressive, lower status youth may associate aggressive behaviors with obtaining higher social status and mirror this behavior. The current study suggests that this phenomenon is seen as early as third grade and may be extremely pertinent in an urban environment.

Several implications for aggression prevention and intervention programming are suggested by these findings. First, it would be an oversight to intervene with youth based solely on the deficits associated with their aggressive behaviors (e.g., difficulties with social information processing, empathy) Clearly, aggression was coupled with prosocial behaviors and social skills such as popularity and leadership in the current study, and this combination of skills and aggression is unfortunately not often accounted for in typical aggression prevention programs (Farmer and Xie 2007; Neal 2010). This oversight could foster treatment resistance or overlook the need for a tailored approach to treatment because it underestimates the fact that aggressive, influential youth can be quite socially skilled individuals and that they may not see a need to reduce their aggression given the positive outcome of prominent social status (Farmer and Xie 2007; Neal 2010). Second, although it makes intervention more complicated, it may be important to recognize that, at times, aggression also may buffer against being victimized by one’s peers (Putallaz et al. 2007). It would therefore be very important for the success of any programming that aims to reduce aggressive behaviors to identify and carefully intervene with these popular, aggressive, leaders as they may be the most influential on the social climate of the school. It would be essential that programming emphasize giving these youth strategies for utilizing their leadership abilities in a more positive way.

Focusing on the positive leadership skills and social influence espoused by aggressive youth may be quite beneficial, especially in urban environments. Some researchers have paved the way for this, designing interventions for relationally aggressive urban minority girls (e.g., Friend to Friend, Leff et al. 2007, 2009), whereby participants not only receive a small-group intervention, but then serve as co-facilitators and leaders by helping to provide a brief classroom version of the program to their classmates. This approach highlights and capitalizes on their status and influence in a positive way. As suggested by our findings, the promising results of Friend to Friend (see Leff et al. 2009) could be due to providing aggressive youth with positive reinforcement for their prosocial leadership and to acknowledging the association between aggression, popularity, and leadership so that aggressive youth can be seen as part of the solution instead of the problem.

Limitations and Areas for Future Research

There are some important limitations to note when reviewing these findings. Because the data utilized in the current study were cross-sectional, causal relationships could not be determined. The use of longitudinal data could allow for this, and also expand these findings beyond this sample of early elementary aged youth and include adolescents as well. A second limitation is our reliance on only one data source for the identification of aggressive behaviors, popularity and leadership. Peer nominations were used given that it is the most widely utilized method for understanding peer relationship and that it has demonstrated strong psychometric properties across many studies (Leff et al. 2011). Some have argued that peer nominations should serve as the gold standard for methods of understanding youths’ social status because this information is more comprehensive than that which is collected via adult informants, self-report, and direct observations, since peers have more frequent contact with classmates across all school settings (Leff et al. 2011), and because all youth in the classroom provide ratings that factor into each child’s eventual nomination score. Further, asking youth to nominate the peers they think are popular is one of the only ways in which to validly understand perceived popularity, reputation and impact from the child’s own perspective (e.g., LaFontana and Cillessen 2002; Parkhurst and Hopmeyer 1998). So, although the use of peer nominations is clearly justified, we note that results would likely have varied if we used another informant method and thus, it may be beneficial to elicit data through additional methods or informants in the future.

Given the high correlation between leadership and popularity, the inclusion of multiple informants and methodologies also would provide additional information regarding these constructs. For example, in the current study, leadership was defined as a child who is often a leader of group activities and games. For a child, this description also may factor into what they think being popular means since it implies the child is highly visible and outgoing. This may cause overlap in the two constructs and also cause leadership to not necessarily be an indicator of positive social skills. In addition, teachers may view the construct of leadership differently than youth. As such, it would be extremely informative to utilize mixed methods to further examine the construct of leadership among inner-city youth and to replicate the findings related to leadership through additional studies.

Conclusion

Aggression in urban high risk environments may be, in part, normative and adaptive in order to achieve personal goals and gain high social status (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011; Garandeau et al. 2010; Luthar and McMahon 1996). This study provides preliminary support for this claim that as early as 3rd grade those who were aggressive were often leaders of their peer groups and had high prestige. This complex association will likely impact the effectiveness of interventions to reduce aggressive behavior unless the interventions take this into account. With increasing focus on reducing aggression in schools, it is important to understand that aggression may afford some children with positive reinforcement by being perceived as popular and as a leader. This reinforcing pattern may begin before adolescence, when the use of aggression and the salience of social status peek. Therefore, when designing beneficial early interventions, it is important not only to help children to decrease levels of aggression, but also to focus on utilizing these highly influential youth as more positive role models and to funnel these children’s potential leadership capabilities in a more prosocial manner (Leff et al. 2010a).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by two NIMH grants to the anchor author, R34MH072982 and R01MH075787, and by cooperative agreement number 5 U49 CE001093 from The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was made possible, in part, by the School District of Philadelphia. Opinions contained in this report reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the School District of Philadelphia.

Biographies

Tracy Evian Waasdorp, Ph.D., M.S.Ed. is a Clinical Research Associate at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and an Associate Research Scientist at Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health. She holds a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania, a doctorate from the University of Delaware, and completed a postdoctoral fellowship in prevention science at Johns Hopkins University. Her research interests include aggression and bullying, relational aggression, peer relationships, and school-based bullying prevention and intervention.

Courtney N. Baker, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor at Tulane University. She received her doctorate in clinical psychology from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and completed her postdoctoral fellowship at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Her research interests include better understanding and facilitating the translation of evidence-based mental health treatments into community settings.

Brooke S. Paskewich, Psy.D. is a Research Program Manager at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She received her doctorate in clinical psychology from Chestnut Hill College in Philadelphia, PA. Dr. Paskewich has managed close to ten grants related to youth violence prevention and school- and community-based aggression prevention programming for urban ethnic minority youth. Her research interests include peer aggression and bullying, relational aggression, and intervention development, implementation, and evaluation.

Stephen S. Leff, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology in Pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and a Psychologist at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He received his doctorate in clinical psychology from The University of North Carolina. Dr. Leff has been the principal investigator on five NIH grants, published a number of articles on school- and community-based aggression prevention for urban ethnic minority youth, and has designed and implemented two relational aggression programs for high risk African American urban youth. Research interests include community-based participatory research, peer aggression and bullying, measurement development, and fidelity monitoring.

Footnotes

An a priori model was run in order to examine the interactive effects of aggression by popularity and aggression by social preference. These interaction terms were significantly associated with leadership, with the exception of the interaction between relational aggression and popularity. Results indicated that youth who are relationally aggressive were more likely to be rated as popular and as leaders as compared to low relationally aggressive youth. For low relationally aggressive youth, being popular was associated with increasing nominations of leadership F(7, 226) = 136.08, p < .05; ΔR2 = .01, p <.05.

Contributor Information

Tracy Evian Waasdorp, Email: waasdorpt@email.chop.edu, Department of Pediatric Psychology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 3535 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Courtney N. Baker, Email: cnbaker@tulane.edu, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA

Brooke S. Paskewich, Email: paskewich@email.chop.edu, Department of Pediatric Psychology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 3535 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

Stephen S. Leff, Email: Leff@email.chop.edu, Department of Pediatric Psychology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 3535 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA. University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA. The Philadelphia Collaborative Violence Prevention Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA

References

- Archer J, Coyne SM. An integrated review of indirect, relational, and social aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9(3):212–230. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Aggression: A social learning analysis. Engle-wood Clifts, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Krishnakumar A. Children in low-income, urban settings: Interventions to promote mental health and well-being. American Psychologist. 1998;53(6):635–646. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.53.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ. Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Blackwell Publishing Limited) 2011;21(1):166–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Stucky BD, Sawalani GM, Little TD. Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development. 2008;79(5):1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Borch C. Developmental trajectories of adolescent popularity: A growth curve modelling analysis. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29(6):935–959. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Mayeux L. From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development. 2004;75(1):147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Rose AJ. Understanding popularity in the peer system. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14(2):102–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00343.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Multiple sources of data on social behavior and social status in the school: A cross-age comparison. Child Development. 1988;59(3):815–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18(4):557–570. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and Types of social status: a cross-age perspective: Correction. Developmental Psychology. 1983;19(2) doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.19.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67(5):2317–2327. doi: 10.2307/1131625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. Engagement in gender normative versus nonnormative forms of aggression: Links to social-psychological adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(4):610–617. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66(3):710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WE, Zarbatany L. Peer group status as a moderator of group influence on children’s deviant, aggressive, and prosocial behavior. Child Development. 2007;78(4):1240–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TW, Estell DB, Bishop JL, O’Neal KK, Cairns BD. Rejected bullies or popular leaders? The social relations of aggressive subtypes of rural African American early adolescents [Article] Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(6):992–1004. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TW, Xie H. Aggression and school social dynamics: The good, the bad, and the ordinary. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45(5):461–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Erwin EH, Allison KW, Meyer A, Sullivan T, Camou S, et al. Problematic situations in the lives of urban African American middle school students: A qualitative study. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17(2):413–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00528.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine N, Carbonneau R, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Tremblay RE. Research review: A critical review of studies on the developmental trajectories of antisocial behavior in females. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):363–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garandeau CF, Wilson T, Rodkin PC. The popularity of elementary school bullies in gender and racial context. In: Jimerson SR, Swearer SM, Espelage DL, editors. Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective. New York, NY, USA: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2010. pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Rowell Huesmann L, Spindler A. Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children [Article] Child Development. 2003;74(5):1561–1576. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH. The ontogenesis of social dominance: A strategy-based evolutionary perspective. Developmental Review. 1999;19(1):97–132. doi: 10.1006/drev.1998.0470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff KE, Reese-Weber M, Schneider WJ, Stagg JW. The association between high status positions and aggressive behavior in early adolescence. Journal of School Psychology. 2009;47(6):395–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudley CA. Comparing teacher and peer perceptions of aggression: An ecological approach. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85(2):377–384. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.85.2.377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer SM, Ryan AM. Striving for social dominance over peers: The implications for academic adjustment during early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100(2):417–428. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD, Dodge KA. The role of poor peer relationships in the development of disorder. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 274–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Children’s peer relations and social competence: A century of progress. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- LaFontana KM, Cillessen AHN. Children’s perceptions of popular and unpopular peers: A multimethod assessment. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(5):635–647. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS. Bullying and peer victimization at school: Considerations and future directions. School Psychology Review. 2007;36(3):406–412. [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Angelucci J, Goldstein AB, Cardaciotto L, Paskewich B, Grossman MB. Using a participatory action research model to create a school-based intervention program for relationally aggressive girls—The Friend to Friend Program. In: Zins JE, Elias MJ, Maher CA, editors. Bullying, victimization, and peer harassment: A handbook of prevention and intervention. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 2007. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Freedman MA, MacEvoy JP, Power TJ. Considerations when measuring outcomes to assess for the effectiveness of bullying- and aggression-prevention programs in the schools. In: Espelage DL, Swearer SS, editors. Bullying in North American Schools. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 2011. pp. 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Gullan RL, Paskewich BS, Abdul-Kabir S, Jawad AF, Grossman M, et al. An initial evaluation of a culturally adapted social problem-solving and relational aggression prevention program for urban African-American relationally aggressive girls. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2009;37(4):260–274. doi: 10.1080/10852350903196274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Waasdorp TE, Crick NR. A review of existing relational aggression programs: Strengths, limitations, and future directions. School Psychology Review. 2010a;39(4):508–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Waasdorp TE, Paskewich B, Gullan RL, Jawad AF, MacEvoy JP, et al. The preventing relational aggression in schools everyday program: A preliminary evaluation of acceptability and impact. School Psychology Review. 2010b;39(4):569–587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, McMahon TJ. Peer reputation among inner-city adolescents: structure and correlates [Article] Journal of Research on Adolescence (Lawrence Erlbaum) 1996;6(4):581–603. [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ, McCaffrey D, Edelen MO. Multiple trajectories of physical aggression among adolescent boys and girls. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34(1):61–75. doi: 10.1002/ab.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux L, Sandstrom MJ, Cillessen AHN. Is being popular a risky proposition? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18(1):49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Morales JR, Guerra NG. Effects of multiple context and cumulative stress on urban children’s adjustment in elementary school. Child Development. 2006;77(4):907–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal JW. Social aggression and social position in middle childhood and early adolescence: Burning bridges or building them? The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30(1):122–137. doi: 10.1177/0272431609350924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bukowski WM, Pattee L. Children’s peer relations: A meta-analytic review of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial, and average sociometric status. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(1):99–128. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bully/victim problems among school children: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. In: Rubin KH, Pepler D, editors. Development and treatment of childhood aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 411–448. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst JT, Hopmeyer A. Sociometric popularity and peer-perceived popularity: Two. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1998;18(2):125. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Long JD. A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20(2):259–280. doi: 10.1348/026151002166442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett MB, Aikins JW, Cillessen AHN. Moderators of the association between relational aggression and perceived popularity [Article] Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34(6):563–576. doi: 10.1002/ab.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putallaz M, Grimes CL, Foster KJ, Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD, Dearing K. Overt and relational aggression and victimization: Multiple perspectives within the school setting. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45(5):523–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DL, Farmer TW, Fraser MW, Day SH, Duncan T, Crowther A, et al. Interpersonal competence configurations and peer relations in early elementary classrooms: Perceived popular and unpopular aggressive subtypes. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34(1):73–87. doi: 10.1177/0165025409345074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodkin PC, Farmer TW, Pearl R, Van Acker R. Heterogeneity of popular boys: Antisocial and prosocial configurations. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(1):14–24. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Gorman AH, Duong MT, Nakamoto J. Peer relationships and academic achievement as interacting predictors of depressive symptoms during middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):289–299. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.117.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton D. Leadership, education, achievement, and development: A nursing intervention for prevention of youthful offending behavior. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2009;14(6):429–441. doi: 10.1177/1078390308327049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott E, Celinska D, Simpson J, Coe MG. ‘Somebody else making somebody else fight’: Aggression and the social context among urban adolescent girls. Exceptionality. 2002;10(3):203–220. doi: 10.1207/s15327035ex1003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teasley ML, Tyson E, House L. Understanding leadership development in African American youth. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2007;15(2/3):79–98. doi: 10.1300/J137v15n02_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. Recent advances in measurement theory and the use of sociometric techniques. In: Cillessen AHN, Bukowski WM, editors. Recent advances in the measurement of acceptance and rejection in the peer system. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2000. pp. 27–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry R, Coie JD. A comparison of methods for defining sociometric status among children. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(5):867–880. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon W, Visconti KJ, Kuntz KJ. Perceived popularity during early adolescence: Links to declining school adjustment among aggressive youth. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2011;31(1):125–151. doi: 10.1177/0272431610384488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T, Hymel S. Aggression and social status: The moderating roles of sex and peer-valued characteristics. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32(4):396–408. doi: 10.1002/ab.20138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T, Hymel S, McDougall P. Bullying is power: Implications for school-based intervention strategies. In: Zins JE, Elias MJ, Maher CA, editors. Bullying, victimization, and peer harassment: A handbook of prevention and intervention. New York, NY, USA: Haworth Press; 2007. pp. 317–337. [Google Scholar]

- van de Schoot R, van der Velden F, Boom J, Brugman D. Can at-risk young adolescents be popular and antisocial? Sociometric status groups, anti-social behaviour, gender and ethnic background. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33(5):583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waasdorp TE, Bagdi A, Bradshaw CP. Peer victimization among urban, predominantly African American youth: Coping with relational aggression between friends. Journal of School Violence. 2010;9(1):98–116. doi: 10.1080/15388220903341372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waasdorp TE, Pas ET, O’Brennan LM, Bradshaw CP. A multilevel perspective on the climate of bullying: Discrepancies among students, school staff, and parents. Journal of School Violence. 2011;10(2):115–132. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2010.539164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcott CM, Upton A, Bolen LM, Brown MB. Associations between peer-perceived status and aggression in young adolescents. Psychology in the Schools. 2008;45(6):550–561. doi: 10.1002/pits.20323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, Karimpour R, Rodkin PC. African American and European American students’ peer groups during Early adolescence: Structure, status, and academic achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2011;31(1):74–98. doi: 10.1177/0272431610387143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Farmer TW, Cairns BD. Different forms of aggression among inner-city African-American children: Gender, configurations and school social networks. Journal of School Psychology. 2003;41(5):355–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4405(03)00086-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Yan L, Boucher SM, Hutchins BC, Cairns BD. What makes a girl (or a boy) popular (or unpopular)? African American children’s perceptions and developmental differences. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(4):599–612. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]